Abstract

Secondary electron transfer in photosystem II (PSII), which occurs when water oxidation is inhibited, involves redox-active carotenoids (Car), as well as chlorophylls (Chl), and cytochrome b 559 (Cyt b 559), and is believed to play a role in photoprotection. CarD2 may be the initial point of secondary electron transfer because it is the closest cofactor to both P680, the initial oxidant, and to Cyt b 559, the terminal secondary electron donor within PSII. In order to characterize the role of CarD2 and to determine the effects of perturbing CarD2 on both the electron-transfer events and on the identity of the redox-active cofactors, it is necessary to vary the properties of CarD2 selectively without affecting the ten other Car per PSII. To this end, site-directed mutations around the binding pocket of CarD2 (D2-G47W, D2-G47F, and D2-T50F) have been generated in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Characterization by near-IR and EPR spectroscopy provides the first experimental evidence that CarD2 is one of the redox-active carotenoids in PSII. There is a specific perturbation of the Car∙+ near-IR spectrum in all three mutated PSII samples, allowing the assignment of the spectral signature of Car∙+D2; Car∙+D2 exhibits a near-IR peak at 980 nm and is the predominant secondary donor oxidized in a charge separation at low temperature in ferricyanide-treated wild-type PSII. The yield of secondary donor radicals is substantially decreased in PSII complexes isolated from each mutant. In addition, the kinetics of radical formation are altered in the mutated PSII samples. These results are consistent with oxidation of CarD2 being the initial step in secondary electron transfer. Furthermore, normal light levels during mutant cell growth perturb the shape of the Chl∙+ near-IR absorption peak and generate a dark-stable radical observable in the EPR spectra, indicating a higher susceptibility to photodamage further linking the secondary electron-transfer pathway to photoprotection.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11120-013-9793-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: β-Carotene radical, Chlorophyll radical, Cytochrome b559, EPR spectroscopy, Near-IR spectroscopy, Photosystem II, Site-directed mutagenesis

Introduction

Photosystem II (PSII) is the enzyme responsible for photosyntheic oxidation of water to O2, generating the reducing equivalents that ultimately are used for CO2 fixation. Water oxidation occurs when excitons are transferred to a special group of chlorophylls, known as P680, where a charge separation occurs, as seen in Fig. 1. The electron is transferred to PheoA on a timescale of tens of picoseconds (Holzwarth et al. 2006), and then to QA with a timescale of 200–500 picoseconds (ps) (Rappaport and Diner 2008). The electron–hole pair on P680 + and Q−A is stable for close to 1 ms in cyanobacteria (Reinman et al. 1981; Gerken et al. 1989; Metz et al. 1989), during which time, under catalytic conditions, the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) donates an electron to P680 + via a redox-active tyrosine, YZ. Once the OEC, which consists of a Mn4CaO5 cluster (Umena et al. 2011), has been oxidized four times via sequential charge separations to reach a high-valent state, probably Mn(IV)Mn(IV)Mn(IV)Mn(IV)-O∙ (Siegbahn 2006; Sproviero et al. 2008), it is capable of oxidizing water to dioxygen. Meanwhile, the electron on QA is transferred to QB, which dissociates away from PSII after two reductions and subsequent protonations, carrying reducing equivalents to the next step in photosynthesis and ultimately resulting in the storage of energy in the chemical bonds of sugars.

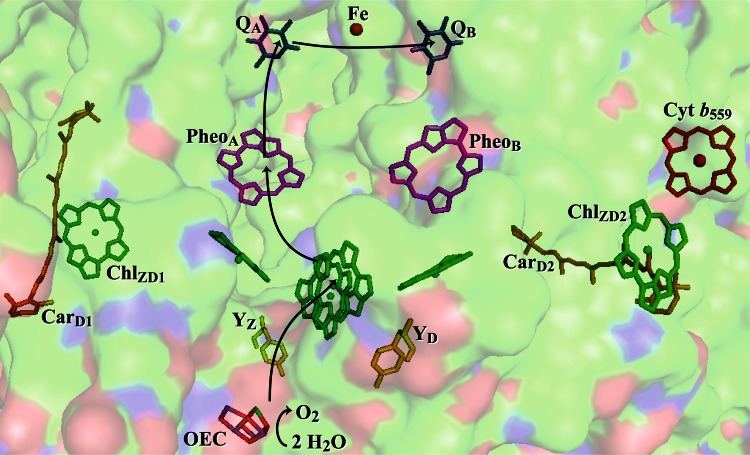

Fig. 1.

The arrangement of cofactors in the D1/D2/Cyt b 559 sub-complex of cyanobacterial PSII, viewed along the membrane plane (PDB ID: 3ARC). Black arrows represent electron transfer. The oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) is shown with manganese ions in purple, oxygen in red, and calcium in green; tyrosine Z (YZ) and tyrosine D (YD) are shown in yellow; chlorophylls (Chl) are shown in green; β-carotenes (Car) are shown in orange; pheophytins (PheoA and PheoB) are shown in magenta; quinones (QA and QB) are shown in blue; and cytochrome b 559 (Cyt b 559) and the nonheme iron are shown in red. The surface of the protein is shown in the background and colored according to atom identity with C in green, N in blue, and O in red

However, the intermediates associated with water splitting are very oxidizing, and cause damage to the protein over time. The D1 subunit of PSII, which contains most of the cofactors involved in water oxidation, turns over every 30 min, in a process that involves disassembly of the PSII complex, membrane diffusion, and protein synthesis (Nixon et al. 2010). In order to minimize damage, PSII has evolved multiple mechanisms of photoprotection to prolong the lifetime of its subunits and minimize energy expenditure for protein synthesis. One mechanism involves adjusting the size of the light-harvesting antenna; other mechanisms involve dissipating excess solar energy as heat, as in the xanthophyll cycle in plants (Niyogi 1999) or via the orange carotenoid protein in cyanobacteria (Kirilovsky and Kerfeld 2012). In addition, when water-oxidation catalysis is impaired, oxidation of secondary donors, including carotenoids (Car), chlorophylls (Chl), and cytochrome b 559 (Cyt b 559), may serve to remove excess oxidizing equivalents from PSII (Thompson and Brudvig 1988; Buser et al. 1992) or to quench chlorophyll excited states (Schweitzer and Brudvig 1997).

Of the secondary electron donors, Cyt b 559 has the lowest reduction potential, which is interestingly variable from 390 mV to as low as −150 mV (Thompson et al. 1989; Stewart and Brudvig 1998). Cyt b 559 is, therefore, the terminal secondary electron donor within PSII. It may additionally be rereduced by the plastoquinone pool, leading to a cyclic process for the removal of excess, damaging oxidizing equivalents from PSII when the system is unable to drive water oxidation (Shinopoulos and Brudvig 2012).

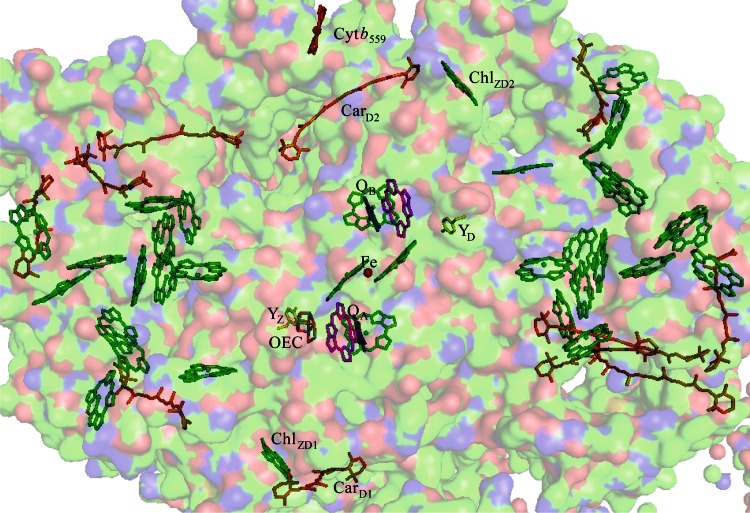

Although the final location of the oxidizing equivalent passed along the secondary electron-transfer pathway has been determined to be Cyt b 559 (Vermeglio and Mathis 1974; de Paula et al. 1985), the pathway of electron transfer from Cyt b 559 to P680 + has not been fully characterized. The distance of about 40 Å between the two cofactors indicates that they do not participate in direct electron transfer, and it has indeed been observed that Chl and Car are intermediates (de Paula et al. 1985; Hanley et al. 1999; Vrettos et al. 1999; Tracewell et al. 2001; Faller et al. 2001). It has also been shown that there are at least two redox-active carotenoids (Car∙+) in PSII based on the shift of the Car∙+ near-IR peak over a range of illumination temperatures and the wavelength-dependant decay rate of the Car∙+ absorbance (Tracewell and Brudvig 2003; Telfer et al. 2003). There are as many as 5 redox-active Chl (Chl∙+) (Tracewell and Brudvig 2008; Telfer et al. 1990), with one ligated to D1-His 118 (Stewart et al. 1998). However, there are 11 Car and 35 Chl per PSII, as seen in Fig. 2, and most of the redox-active cofactors have not been specifically identified. Some Chl∙+ may be in CP43 and CP47, peripheral subunits that bind many Chl molecules (Tracewell and Brudvig 2008). In regard to the two Car∙+, it has been observed that the average distance from the nonheme iron to the two Car∙+ is 38 Å, and it has been hypothesized that one Car∙+ is Car∙+D2 (Lakshmi et al. 2003; Tracewell and Brudvig 2003). This seems likely, because CarD2 is the closest cofactor to both P680 and Cyt b 559, with edge-to-edge distances of 11 and 12 Å, respectively. The oxidation of YD results in a shift of the Car∙+ near-IR peak, indicating proximity of at least one Car∙+ to YD (Tracewell and Brudvig 2003), although electrochromic effects can propagate significant distances though PSII (Stewart et al. 2000). A relatively higher yield of Car∙+ than Chl∙+ is observed at lower temperatures, with increased Chl∙+ at higher temperatures, also indicating that Car∙+ is closer than Chl∙+ to P680 (Hanley et al. 1999).

Fig. 2.

The arrangement of cofactors in PSII, viewed from the membrane surface (PDB ID: 3ARC). The oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) is shown with manganese atoms in purple, oxygen in red, and calcium in green; tyrosine Z (YZ) and tyrosine D (YD) are shown in yellow; chlorophylls (Chl) are shown in green; β-carotenes (Car) are shown in orange; pheophytins (PheoA and PheoB) are shown in magenta; quinones (QA and QB) are shown in blue; and cytochrome b 559 (Cyt b 559) and the nonheme iron are shown in red. The surface of the protein is shown in the background and colored according to atom identity with C in green, N in blue, and O in red

In order to evaluate the role of CarD2 in secondary electron transfer relative to the roles of other Car in PSII, we have characterized the effects of site-directed mutations around the binding pocket of CarD2 (see Fig. 3). In this study, the effects of the mutations D2-G47W, D2-T50F, and D2-G47F on the secondary electron-transfer pathway are examined by low temperature near-IR optical and EPR spectroscopy.

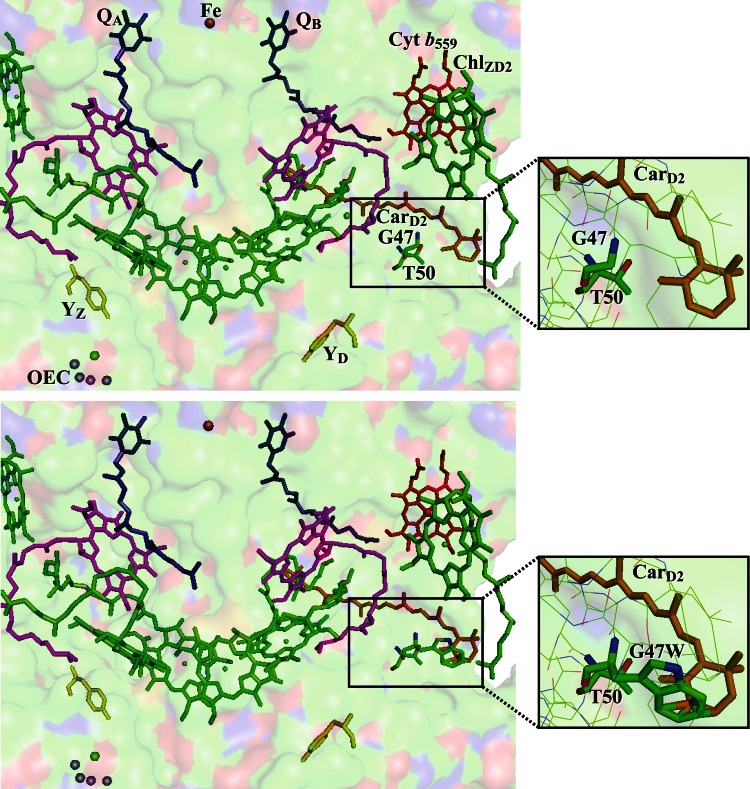

Fig. 3.

Electron-transfer cofactors in photosystem II, viewed along the membrane plane (PDB ID: 2AXT). The oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) is shown with manganese atoms in purple and calcium in green; tyrosine Z (YZ) and tyrosine D (YD) are shown in yellow; chlorophylls (Chl) are shown in green; β-carotene (Car) is shown in orange; pheophytins (PheoA and PheoB) are shown in magenta; quinones (QA and QB) are shown in blue; and cytochrome b 559 (Cyt b 559) and the nonheme iron are shown in red. The surface of the protein is shown in the background and colored according to atom identity with C in green, N in blue, and O in red. Top A model of WT PSII structure, containing D2-G47 and D2-T50 modeled in stick form. Inset an enlarged picture of G47, T50, and the β-ionylidene ring of CarD2 with the surrounding residues shown as lines, colored according to atom identity. Bottom A model of D2-G47W, with G47W and T50 modeled in stick form. Inset an enlarged picture of G47W, T50, and the β-ionylidene ring of CarD2 with the surrounding residues shown as lines, colored according to atom identity

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid (MES) was purchased from USB Corporation. β–Dodecyl maltoside (β-DM) was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences International Inc. A stock solution (80 mM) of potassium ferricyanide (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared in buffer and frozen until use.

Mutagenesis

D2 mutants were constructed according to (Tang et al. 1993) except that the recipient strain Tol145/CP47-His, obtained by transforming strain Tol145 (Tang et al. 1993) with genomic DNA from strain PSII-His (Boehm et al. 2011), also encoded a C-terminal His-tagged derivative of CP47. Plasmid pDC074 was used as the parental vector for site-directed mutagenesis (Tang et al. 1993). Mutations were introduced into the plasmid by overlap-extension PCR so that the codon specifying D2-G47 was replaced by either TGG (to make mutated D2-G47W) or TTC (D2-G47F) and the codon specifying D2-T50 was replaced by TTC (D2-T50F). In all three cases, the codon for Leu45 (CTG) was mutated to incorporate a silent mutation (CTA), in order to create a unique restriction site, AvrII, to help screen for mutations. The genotypes of the cyanobacterial mutants were confirmed by PCR analysis and DNA sequencing.

Cell growth and protein purification

Cells were grown initially on plates containing 5 mM glucose, 10 μM DCMU, 25 mg/L kanamycin, and 10 mg/L erythromycin. In liquid culture, the cells were grown without antibiotics in the presence of 5 mM glucose under 10 or 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination, as noted. His-tagged PSII core particles were isolated from Synechocystis PCC 6803 cells as previously described (Lakshmi et al. 2002).

Sample treatments

For low-temperature measurements, PSII samples were transferred to a buffer containing 15 mM CaCl2, 63 % (v/v) glycerol, and 50 mM MES at pH 6.0. Prior to freezing, PSII samples were treated with 5 mM ferricyanide to oxidize Cyt b 559.

Near-IR optical spectroscopy

A Perkin-Elmer Lambda 20 spectrometer was used to make optical spectroscopic measurements in the visible and near-IR. Low-temperature optical measurements were made with an Oxford Instruments Optistat liquid helium cryostat. Polyethylene cuvettes with a 1.0 cm path length and 0.4 cm width (Fisher Scientific) were used for low-temperature optical measurements. A 150 W quartz-halogen lamp filtered by a 6 in water filter and a heat-absorbing filter (Schott KG-5) was used to illuminate samples. A Schott-Fostec randomized fiber optic bundle was used to direct the light into the cryostat. The PSII samples were prepared as previously described (Tracewell and Brudvig 2008). Illumination for 15 min was performed on samples that were equilibrated at the specified temperature for at least 60 min in the cryostat. All spectra collected after illumination are referenced to the dark spectrum measured at the same temperature to avoid contributions from spectral changes in the background due to temperature effects.

Spectral simulations

The program Igor Pro 6.2 was used to simulate the near-IR absorption data, to analyze the decay kinetics, and to plot all spectra.

EPR spectroscopy

X-band EPR measurements were conducted on a Bruker ELEXSYS E500 EPR spectrometer equipped with an Oxford ESR 900 He-flow cryostat and a Super High Q cavity. Samples were illuminated by a xenon halogen lamp filtered by a 6 in water filter and a heat-absorbing filter, with a fiber optic cable directing light into the cryostat. Radical yields per PSII were determined by integration of the derivative EPR signals and calibrated to photooxidized tyrosine D (Y•D). Y•D was generated by illuminating the PSII samples for 30 s at 0 °C, incubating on ice for 2 min, and freezing in total darkness.

Results

Selection of mutations

The mutations D2-G47F, D2-G47W, and D2-T50F were selected by using Coot, a modeling program that includes the ability to mutate a selected residue from a known crystal structure (Emsley and Cowtan 2004). The mutated residue is placed in the conformation in which it is typically found, and other conformations are also observable. Using the 3.0-Å resolution crystal structure of PSII (Loll et al. 2005), which was focused on accurate cofactor positioning and found similar locations to the recent 1.9-Å resolution structure (Umena et al. 2011), residues that would sterically interfere with CarD2 binding were identified, as shown in Fig. 3. Aromatic residues have been observed around the β-ionylidene ring binding site (Tracewell and Brudvig 2003), which has been found to be important for function (Bautista et al. 2005), and because the Car chain exists in a variety of conformations in PSII samples, the area near the rings was targeted for mutation. In this way, several mutations were identified that may cause a disruption to the hydrophobic binding pocket of the β-ionylidene ring of CarD2.

Near-IR Optical Spectroscopy

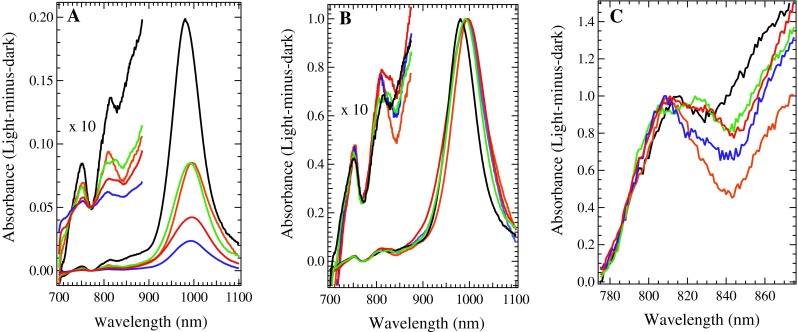

WT, D2-T50F, D2-G47W, and D2-G47F His-tagged PSII complexes were illuminated in a cryostat at 20 K for 15 min, maximally generating one stable charge separation per PSII center; at this temperature in ferricyanide-treated samples, the stable charge separation results in an electron on Q−A and a hole that is located on either a Car neutral radical (Car∙ absorbing at 750 nm), a Chl cation radical (Chl∙+ absorbing at 800–840 nm) or a Car cation radical (Car∙+ absorbing near 1,000 nm), as seen in Fig. 4. For each mutated PSII sample, the total yield of stable charge separated states was lower than in WT PSII samples when normalized to the same concentration of Chl, indicated by the lower yield of all secondary donors (Car∙, Chl∙+, and Car∙+), seen in Fig. 4A. When the magnitudes of the Car∙+ peaks are normalized to 1, as in Fig. 4B, it can be seen that the Car∙+ peak is slightly red shifted and has a larger FWHM in mutated PSII samples compared to WT PSII samples. The yield of the Car∙ peak at 750 nm tracks with the magnitude of the Car∙+ peak, reinforcing that it is generated from Car (Gao et al. 2009). In the mutated PSII samples, there is slightly more Chl∙+ generated relative to Car∙+ than in WT, especially in the G47F and G47W PSII samples, with an absorbance centered at 825 nm. Although the yield of Chl∙+ appears to be very low, it has an extinction coefficient of about 7,000 M−1 cm−1 (Borg et al. 1970), while Car∙+ has an extinction coefficient of about 160,000 M−1 cm−1 (Tan et al. 1997). The width and shape of the Chl∙+ peak varies among the samples, as seen in Fig. 4C. The T50F PSII sample isolated from cells grown at 10 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination has the narrowest peak, followed closely by G47F PSII samples. PSII samples isolated from G47W, T50F grown under 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination, and WT cells display wider Chl∙+ signatures that appear to contain two peaks.

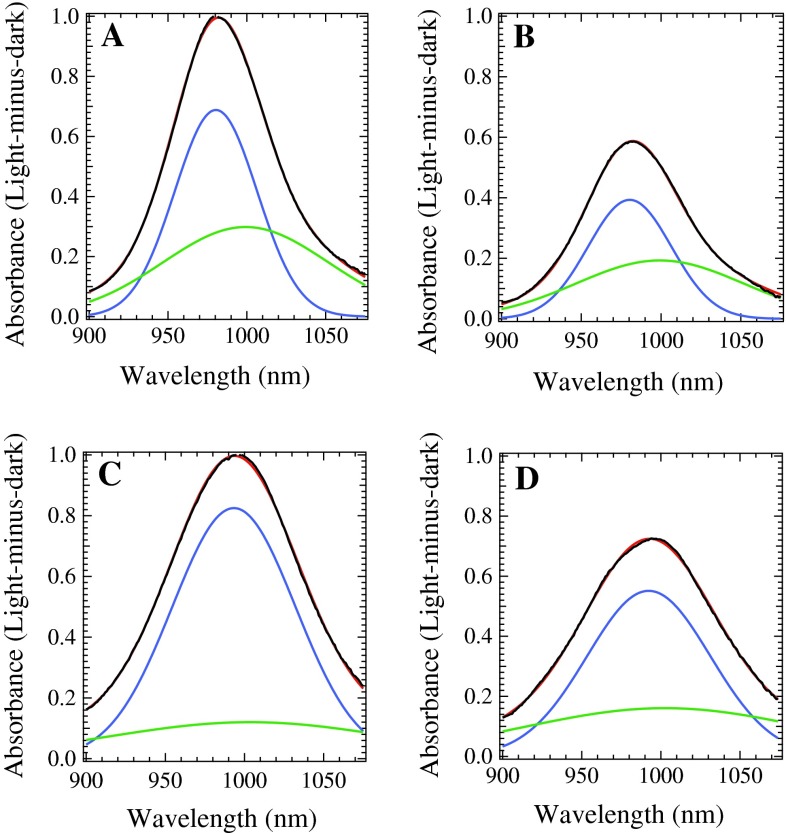

Fig. 4.

Light-minus-dark near-IR spectra of Synechocystis PSII samples from WT cells grown under 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination (black), T50F cells grown under 10 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination (green), T50F cells grown under 40 μEinsteins/m2/s (orange), G47W cells grown under 10 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination (red), and G47F cells grown under 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination (blue), recorded at 20 K. A Normalized to equal chlorophyll concentration. B Each Car∙+ peak normalized to 1. C Each Chl∙+ peak normalized to 1

Using global analysis in Igor Pro 6.2, the Car∙+ peak in all PSII samples was deconvoluted into two Gaussian contributions. One contribution had a maximum at 999–1,003 nm, while the other varied from 980 nm in WT PSII to 993 nm in G47W PSII, as seen in Table 1. The FWHM of the Gaussian components were, in general, larger in the mutated PSII samples, with the widest peaks appearing in the G47 W PSII spectrum.

Table 1.

The peak parameters of the two Gaussian components of the Car∙+ peak present in WT, T50F, G47F, and G47W PSII samples

| λ1 (nm) | Initial % | FWHM1 (nm) | λ2 (nm) | Initial % | FWHM2 (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 980.4 | 69 | 37.9 | 999.2 | 31 | 74.1 |

| T50F | 989.3 | 68 | 43.2 | 999.8 | 32 | 92.8 |

| G47F | 988.3 | 48 | 40.8 | 1001 | 52 | 68.0 |

| G47W | 993.3 | 82 | 55.0 | 1003 | 17 | 127 |

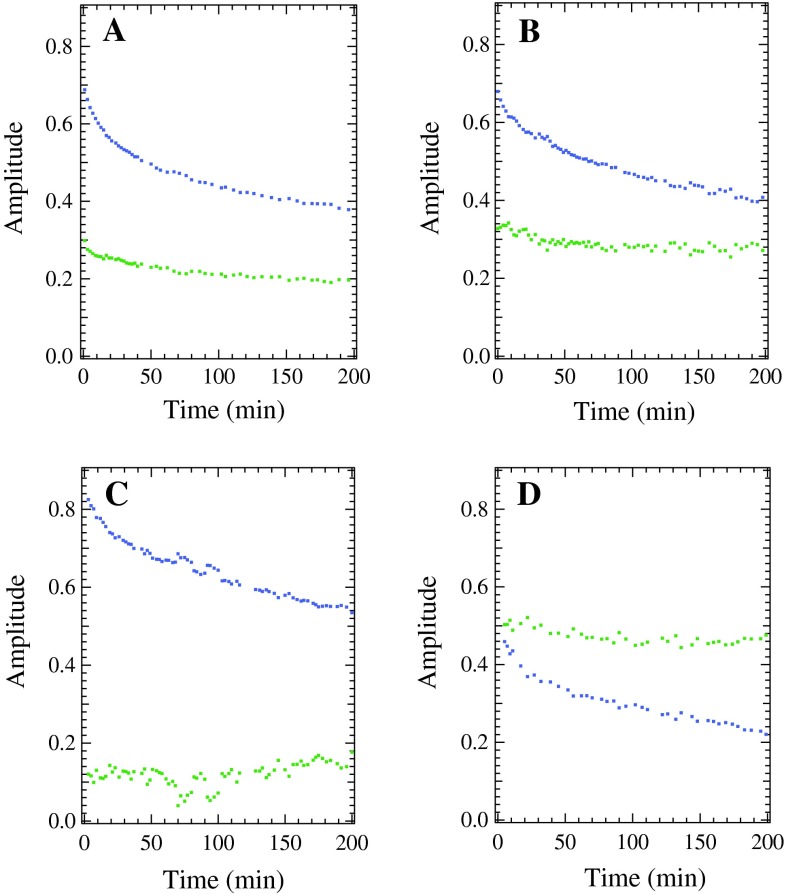

The relative amounts of the longer-wavelength component and shorter-wavelength component varied among the WT and mutated PSII samples, with the G47F PSII spectrum containing the most longer-wavelength component, the G47W spectrum containing the least longer-wavelength component, and the WT and T50F spectra containing a similar ratio to each other, as seen in Table 1; Figs. 5 and 6. In addition, in each PSII sample, the shorter-wavelength component of the Car∙+ peak decayed more quickly and to a larger extent. Therefore, there was a larger proportion of the longer-wavelength component present at longer times.

Fig. 5.

Gaussian deconvolutions of the Car∙+ peak formed by illumination for 15 min at 20 K. A The WT PSII difference spectrum after 0 min of dark incubation. B The WT PSII difference spectrum after 3 h of dark incubation. C The G47W PSII difference spectrum after 0 min of dark incubation. D The G47W PSII difference spectrum after 3 h of dark incubation. The two Gaussian components from Table 1 are shown in blue (shorter-wavelength component) and green (longer-wavelength component), their sum is shown in red, and the raw data are shown in black

Fig. 6.

The decay in absorbance, as a function of dark incubation time, of the shorter-wavelength component (blue) and the longer-wavelength component (green). A WT PSII samples. B T50F PSII samples. C G47W PSII samples. D G47F PSII samples

EPR Spectroscopy

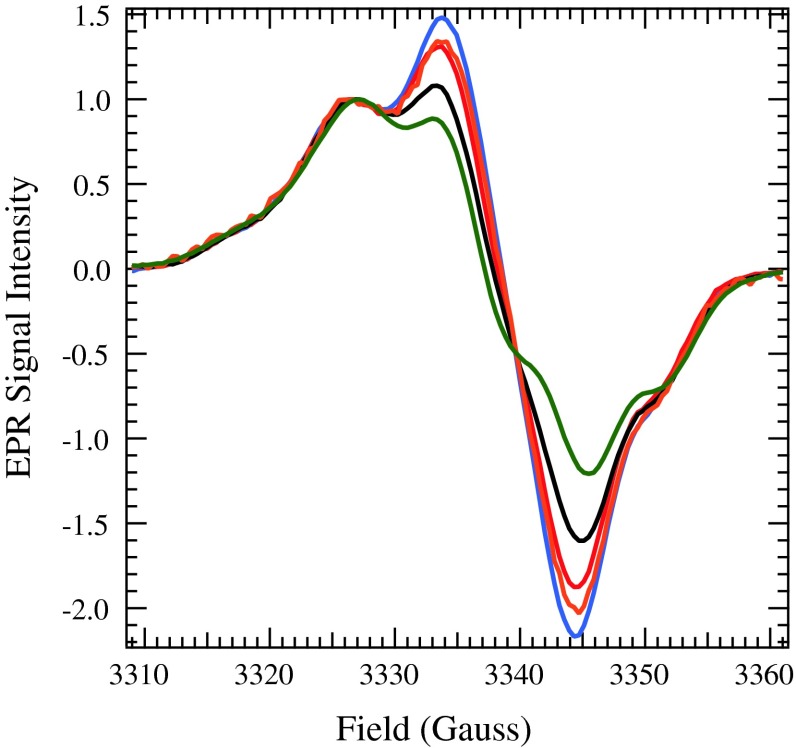

Following the generation of Y∙D, EPR spectra of WT, D2-T50F, D2-G47W, and D2-G47F PSII samples were collected in total darkness at 30 K, as seen in Fig. 7. The lineshapes vary slightly among the spectra. The spectra of T50F PSII grown at 10 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination exhibit the most characteristic Y∙D pattern. The WT spectrum also matches the lineshape reported in the literature for Y∙D (Un et al. 1996; Tang et al. 1993; Noren et al. 1991). However, the spectra of PSII isolated from G47 W, T50F grown at 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination, and G47F cells deviate increasingly from a normal Y∙D spectrum. The shift could be due to a change in the orientation of the methylene protons with respect to the ring in the tyrosyl radicals of the mutated PSII samples, resulting in altered hyperfine coupling (Barry and Babcock 1998). However, due to the shift in g value of the baseline crossing point toward the free-electron g value and the consistency of the most upfield and downfield hyperfine peaks, it appears that the change in lineshape is due to an organic radical signal overlapping with Y∙D. Although this is consistent with the presence of Chl∙+ and Car∙+, which may be generated by illumination, these species have a very short lifetime at 0 °C, and would have typically decayed during dark incubation. In addition, there is a larger amount of the organic radical signature present in the spectrum from T50F grown at 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination than is present in the spectrum from T50F grown at 10 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination, indicating that the presence of an overlapping radical EPR signal is due to an effect of high light during growth of the cells rather than an effect of the mutation on the structure of Y∙D.

Fig. 7.

EPR spectra in the Y∙D region of PSII isolated from WT cells grown under 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination (black), T50F cells grown under 10 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination (green), T50F cells grown under 40 μEinsteins/m2/s (orange), G47W cells grown under 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination (red), and G47F cells grown under 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination (blue). Instrument settings: temperature, 30 K; microwave power, 105 μW; and field modulation amplitude, 4 G

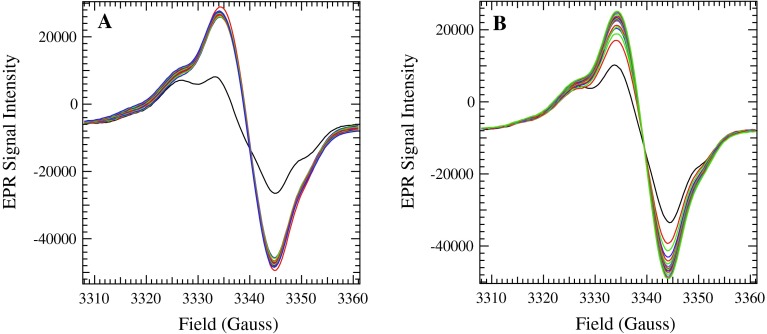

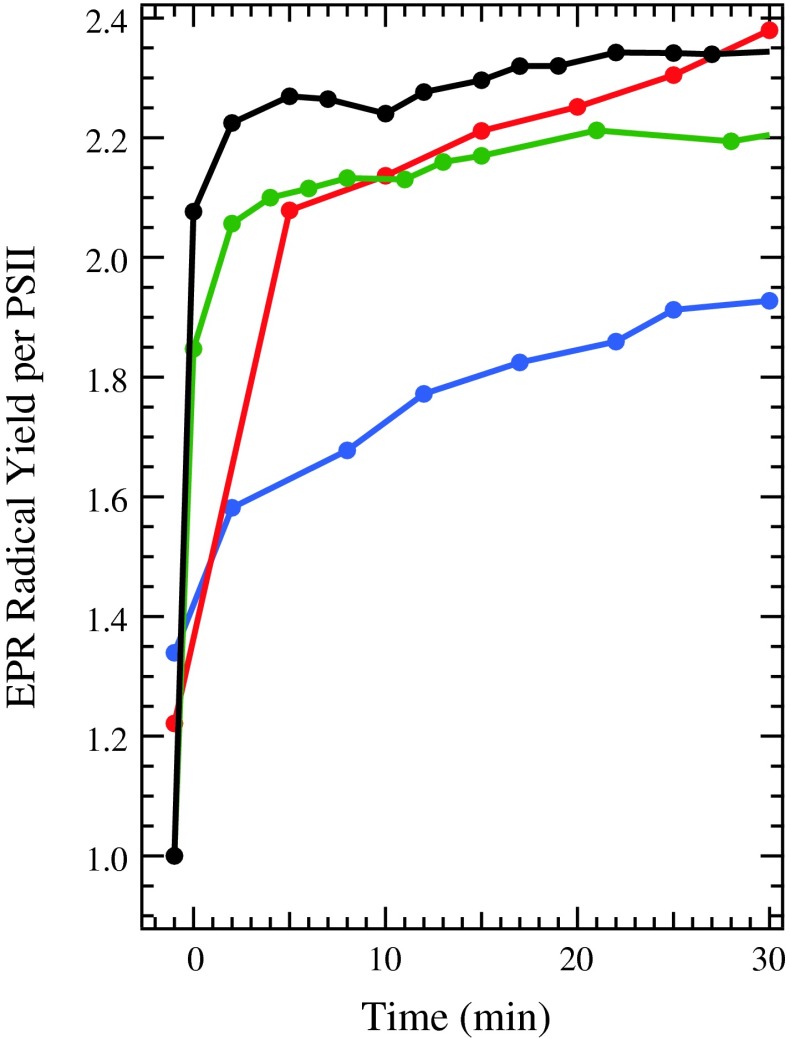

The samples containing Y∙D were subsequently illuminated in the cryostat at 30 K for 60 min and spectra were recorded during the illumination, as seen in Figs. 8 and 9. During the illumination, Chl∙+ and Car∙+ (Figs. 8 and 9), which have indistinguishable g values at X band (Hanley et al. 1999), and some oxidized Cyt b 559 (data not shown) were formed. For the WT PSII sample (Fig. 8A), the total yield of oxidized secondary donors was generated within 5 min of illumination. In contrast, in the G47F PSII sample (Fig. 8B), the maximum yield of oxidized secondary donors was not reached until after 30 min of illumination.

Fig. 8.

The EPR spectra collected as samples were illuminated in the cryostat with a xenon lamp for 1 h. A WT spectra collected in the dark (black) and after 0 (red), 5 (green), 10 (blue), 15 (red), 20 (green), 25 (blue), 30 (blue), 35 (red), 40 (green), 45 (blue), 50 (red), 55 (green), and 60 (blue) minutes of illumination. B G47F spectra collected in the dark (black) and after 2 (red), 8 (green), 12 (blue), 17 (red), 22 (green), 25 (blue), 30 (red), 34 (green), 38 (blue), 42 (red), 47 (green), 51 (blue), 55 (red), and 60 (green) minutes of illumination. Instrument settings as in Fig. 7

Fig. 9.

The radical yield per PSII as a function of illumination time, obtained by double integration of the EPR spectra of WT (black), T50F (green), G47W (red), and G47F (blue) PSII samples, recorded at 30 K. Instrument settings as in Fig. 7

The procedure for generating Y∙D results in one dark-stable Y∙D per PSII, formed on ice before the sample is frozen for measurement of the EPR spectrum. Double integration of the Y∙D EPR spectra gives the area corresponding to one radical per PSII center, once it has been corrected for any other overlapping organic radical signals. Under illumination at cryogenic temperatures, PSII is limited to one charge separation, and a second EPR signal is generated from the electron donor in each PSII center. Therefore, there should be a total of two oxidized species on the electron donor side of PSII for each PSII center: one Y∙D and either Chl∙+, Car∙, Car∙+, or oxidized Cyt b 559. However, the kinetics of formation of the second radical varied among the WT and mutated PSII samples, as seen in Fig. 9. WT and T50F samples generated the full radical yield within a few minutes of illumination. G47W samples took slightly longer to reach the total yield, while G47F samples reached two radicals per PSII only after a full 60 min of illumination (data from 30 to 60 min not shown).

Discussion

CarD2 occupies a position between P680, the initial oxidant, and Cyt b 559, the terminal electron donor, in the path of secondary electron transfer. Removing or disrupting this cofactor would be expected to alter the electron-transfer properties of PSII, if CarD2 is involved as an early donor in the secondary electron-transfer pathway. Indeed, the yields and kinetics of Car and Chl radical formation are altered in PSII samples that have been mutated to alter D2-G47 and D2-T50, two amino acids near CarD2. We have studied the properties of these mutated PSII complexes in which CarD2 is perturbed in order to gain more information on the secondary electron-transfer cofactors and their connectivity.

At cryogenic temperatures, illumination generates one stable charge separation per PSII, resulting in the formation of Q−A and either Car∙, Chl∙+, Car∙+, or oxidized Cyt b 559. Cyt b 559, which has the lowest reduction potential, is the preferred and terminal secondary electron donor within PSII. When Cyt b 559 is preoxidized, one Car∙, Chl∙+, or Car∙+ intermediate is observed per PSII center upon illumination. The relative amounts of these radicals generated in a PSII sample are affected by temperature (Tracewell and Brudvig 2003) and by sample conditions (Hanley et al. 1999). If there were one accessible cofactor with the lowest reduction potential in each PSII center, a single radical would be generated, rather than a distribution. Therefore, the cofactors must be closely spaced in redox potential and have good connectivity to result in different radicals being trapped in different PSII centers. The D2-G47W, D2-G47F, and D2-T50F mutations are located near the headgroup of CarD2 and are expected to perturb CarD2 sterically, while the F and W residues may also participate in π stacking. These changes may affect the stability of Car∙+D2 relative to the other redox-active Car and Chl cofactors, because their redox potentials are so closely spaced.

It is known that there are at least two redox-active Car (Tracewell and Brudvig 2003; Telfer et al. 2003), and five redox-active Chl (Tracewell and Brudvig 2008) in the secondary electron-transfer pathways of PSII. However, the sequence of electron-transfer events and the specific identity of Car and Chl cofactors in the pathway are unknown (Faller et al. 2001). The effect of perturbing CarD2 on the rates and yields Chl∙+ and Car∙+ formation will depend on the connectivity of CarD2 with the other redox cofactors in the secondary electron-transfer pathway. For example, if another redox cofactor were capable of donating an electron to P∙+680 on an appropriate timescale, then the effect of perturbing CarD2 could be negligible. However, in each of the mutated PSII samples (D2-G47W, D2-G47F, and D2-T50F), a substantial decrease in yield of the secondary donors is observed by near-IR spectroscopy (Fig. 4A). Therefore, CarD2 seems to act as a bottleneck, resulting in decreased yield of the Car∙ peak at 750 nm, the Chl∙+ peak from 800 to 840 nm, and the Car∙+ peak near 1,000 nm in all mutated PSII samples. Thus, there is no efficient alternative pathway for transferring electrons to P∙+680. Similarly, as observed by EPR spectroscopy around the g = 2 region, the kinetics of formation for the secondary donor radicals are much slower in the G47F and G47W-mutated PSII samples than in the WT sample, although they are comparable to WT in the T50F-mutated PSII sample, which was modeled as having the smallest perturbation to CarD2 (Fig. 9). The G47F and G47W-mutated PSII samples are less efficient at forming a charge separation between Q−A and the secondary donors, indicating that CarD2 is involved in this process. The decreased yield and impaired kinetics of the mutated PSII samples indicate that CarD2 is an early intermediate in secondary electron transfer, consistent with CarD2 being the initial electron donor to P680 and the initial step in an extended “branched” secondary electron-transfer pathway.

In addition to the decreased overall radical yield, there is a specific perturbation of the near-IR spectrum in each mutated PSII sample: the maximum of the Car∙+ peak is shifted to slightly longer wavelengths (Fig. 4B), while the maxima of the Chl∙+ and Car∙ peaks remain unchanged. This indicates that the Car∙ is not generated from CarD2, but most likely from a Car with a nearby proton accepting amino acid residue, as previously proposed (Gao et al. 2009). Furthermore, when the Car∙+ peak is deconvoluted into two Gaussian components, each corresponding to a redox-active Car∙+ (Tracewell and Brudvig 2003), the shorter-wavelength component shifts significantly more than the longer-wavelength component (more than three times, see Table 1). In WT PSII, the shorter-wavelength component has a maximum at 980 nm and a FWHM of 37.9 nm, and is the dominant contribution to the Car∙+ peak at 20 K. It decays much more quickly than the longer-wavelength component, although it remains the dominant contribution to the peak over 8 h of dark decay, indicating that it is closer to Q−A than is the other Car∙+. We assign this faster-decaying, shorter-wavelength component with a maximum at 980 nm to Car∙+D2. Although CarD2 has been proposed to be the initial electron donor in the pathway of secondary electron transfer (Lakshmi et al. 2003; Tracewell and Brudvig 2003), the specific spectral perturbations of site-directed mutations near CarD2 on the 980 nm Car∙+ species provide the first direct evidence that CarD2 is one of the redox-active Car in PSII.

Previous studies have shown that the maximum of the Car∙+ near-IR peak shifts to a slightly shorter wavelength when YD is oxidized to Y∙D in all PSII centers (Tracewell and Brudvig 2003). It was hypothesized that this was either due to an electrochromic shift caused by YD or due to biasing electron transfer so that the redox-active Car closest to Y∙D would remain reduced to avoid electrostatic repulsion. However, it has been observed that electrochromic shifts propagate substantial distances through PSII. For example, generating Q−A affects the visible spectrum of BA, the accessory Chl near PA of P680, from 21 Å away, and also possibly affects the spectrum of BB, 29 Å away (Stewart et al. 2000). Although Y∙D would most likely have a smaller electrochromic effect than Q–A, its effects do propagate at least as far as P680 (Diner and Rappaport 2002). CarD2 is approximately 25 Å from YD. Alternatively, there are several Car cofactors in CP47 that are at a comparable or even shorter distance from YD; one Car in CP47 is 21 Å from YD, another is 27 Å away, and two others are about 30 Å from YD. Due to closely spaced distances, an electrochromic shift would not be a definitive indicator of which Car is oxidized, even if it were observable at those distances. It is also possible that oxidation of YD may bias the path of secondary electron transfer. To pull an electron from one of the Car in CP47, two intermediate Chl∙+ would be involved that are each 20 Å from Y∙D, to ultimately generate a terminal Car∙+ that may be as close as 21 Å to Y∙D. Under these conditions, the 980 nm Car∙+D2 may be a more stable radical than the 999 nm Car∙+, resulting in a net shift of the Car∙+ peak to a shorter wavelengths.

The near-IR spectra of D2-G47W, D2-G47F, and D2-T50F PSII samples contain a relatively larger amount of the Chl∙+ peak as compared to the Car∙+ peak than WT PSII samples (Fig. 4B). One possibility is that the mutations around the headgroup of CarD2 caused a shift of the reduction potential of Car∙+D2 to a higher value, making it more difficult to oxidize CarD2 relative to other Chl and Car cofactors. This would destabilize Car∙+D2, which is the predominant donor in the charge separation (980 nm Car∙+, see Fig. 5; Table 1), thus favoring Chl∙+ in a greater portion of PSII centers. This model can explain the observations for the G47F PSII sample, which has both a lower yield of Car∙+D2 relative to the other Car∙+ and also a higher yield of Chl∙+. Alternatively, the mutations around the headgroup of CarD2 and its change in conformation may have affected the distances to other cofactors, biasing the electron-transfer pathway in a different direction, such as towards CP47, which is adjacent to the mutations and contains an extended cluster of Chl relatively close to CarD2 (Fig. 2). This model can explain the observations for the G47W PSII sample, which has the largest relative amount of Chl∙+ and also has the most Car∙+D2 compared to the other Car∙+. It is likely that a combination of these factors occurs. Regardless, the relative Chl∙+ radical yield is higher in each of the mutated PSII samples.

The mutated PSII samples isolated from cells grown at higher light exhibit a dark-stable radical observed by EPR spectroscopy (Fig. 7). The dark-stable radical has the appearance of an organic radical, and could be either a Chl∙+ or Car∙+, although it is unusual in that it persists on ice for more than 2 min in the dark. However, a similar observation has been made for PSII samples subjected to photoinhibitory illumination (Blubaugh et al. 1991). The G47F PSII sample has the largest amount of the dark-stable radical, and it also has the slowest kinetics of charge separation. Therefore, it is possible that the dark-stable radical is associated with a quenching state, such that there is a decrease in the stability and efficiency of charge separation (Schweitzer and Brudvig 1997).

In addition, the shape of the Chl∙+ peak appears to depend on the light exposure during growth. The PSII samples isolated from G47W cells grown at 10 μEinsteins/m2/s, and from T50F cells grown at 10 μEinsteins/m2/s show a double Chl∙+ peak with maxima at 812 and 826 nm. Conversely, PSII isolated from G47F cells grown at 40 μEinsteins/m2/s and from T50F cells grown at 40 μEinsteins/m2/s only display one Chl∙+ peak. Moreover, the G47F and T50F PSII samples from cells grown under 40 μEinsteins/m2/s of illumination contain the largest amounts of the dark-stable radical. This suggests that the dark-stable radical may reflect a bias in the pathways of secondary electron transfer such that fewer Chl cofactors are oxidized in PSII samples isolated from cells grown under high light than those grown under lower light conditions. The Chl∙+ peak in WT PSII also appears to have only one peak, but it is broader than the single peak in T50F and G47F PSII samples. It seems that the double Chl∙+ peak is observed for cells grown under lower light. A double Chl∙+ peak has been previously observed for spinach PSII, but not for Synechocystis PCC 6803 PSII (Tracewell et al. 2001). Perhaps the double versus single Chl∙+ peak correlates in some way with photodamage and/or photoprotection, rather than an intrinsic species difference.

The Car∙+ near-IR absorption peak is wider in the mutated PSII samples relative to WT PSII samples, an indication that the Car∙+ population may have become less homogeneous as a result of the mutations. The G47W and T50F PSII samples have the widest Car∙+ peaks (Fig. 4). These wider peaks may be an indication that more than one longer-wavelength Car∙+ contributes to the peak; because the longer-wavelength Car∙+ arise from a charge separation that is more stable than that involving Car∙+D2, they would include components that are located further from Q–A than CarD2. Using high-frequency saturation-recovery EPR experiments, it has been found that the average distance from the nonheme iron to Car∙+ is 38 ± 1 Å (Lakshmi et al. 2003). Because Car∙+D2 is 36 Å from the nonheme iron, we can hypothesize that other candidate Car∙+ would be located about 40 Å from the nonheme iron. There are three Car molecules that are 40 Å from the nonheme iron: CarD1, a Car located at the interface of CP43 and PsbZ, and a Car located at the interface of CP47 and PsbM. There is previous evidence that ChlZD1, which is adjacent to CarD1, can be oxidized (Stewart et al. 1998). CarD1 oxidation is also observed in isolated PSII reaction centers, containing the subunits D1, D2, Cyt b 559, and PsbI (Telfer et al. 1991). However, the two Car located at interfaces 40 Å from the nonheme iron are further from Q–A, and would, therefore, recombine more slowly than Car∙+D2, and are also located near lipids that may have an affect on their redox potential (Tracewell and Brudvig 2008). More evidence is required to identify the precise location of the longer-wavelength absorbing Car∙+. However, the shorter-wavelength Car∙+ component, with a maximum at 980 nm in WT, is Car∙+D2, as indicated by the significant shift of its wavelength maximum following a mutation around the headgroup of CarD2.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Chemical Sciences, DE-FG02-05ER15646 (G.W.B.), by a National Institutes of Health predoctoral traineeship, GM08283 (K.E.S.), and by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC, EP/F00270X/1) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC, BB/C507037) (P.J.N.).

Abbreviations

- β-DM

β-Dodecylmaltoside

- Car

β-Carotene

- Car∙+

Oxidized Car

- Chl

Chlorophyll

- Chl∙+

Oxidized Chl

- CP47

47 kDa Chlorophyll-binding protein of photosystem II

- Cyt b559

Cytochrome b 559

- D1/D2

Homologous PSII reaction center core proteins

- DCMU

3-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea

- EPR

Electron paramagnetic resonance

- FWHM

Full width at half maximum

- His-tagged PSII

Synechocystis PCC 6803 PSII containing hexa-histidine-tagged CP47

- MES

2-[N-morpholino] ethanesulfonic acid

- OEC

Oxygen-evolving complex

- P680

Primary chlorophyll electron donor in PSII

- Pheo

Pheophytin

- PSII

Photosystem II

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- QA

Non-exchanging plastoquinone electron acceptor in PSII

- QB

Exchangeable plastoquinone electron acceptor in PSII

- WT

Wild type

- YZ/YD

Redox-active tyrosines in the D1/D2 polypeptides

Footnotes

Guest Editor: Melvin Okamura

References

- Barry BA, Babcock GT. Characterization of the tyrosine radical involved in photosynthetic oxygen evolution. Chem Scr. 1998;28A:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista JA, Tracewell CA, Schlodder E, Cunningham FX, Brudvig GW, Diner BA. Construction and characterization of genetically modified Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 photosystem II core complexes containing carotenoids with shorter π-conjugation than β-carotene. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38839–38850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504953200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blubaugh DJ, Atamian M, Babcock GT, Golbeck JH, Cheniae GM. Photoinhibition of hydroxylamine-extracted photosystem II membranes: identification of the sites of photodamage. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7586–7597. doi: 10.1021/bi00244a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm M, Romero E, Reisinger V, Yu J, Komenda J, Eichacker LA, Dekker JP, Nixon PJ. Investigating the early stages of photosystem II assembly in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:14812–14819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.207944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg DC, Fajer J, Felton RH, Dolphin D. The π-cation radical of chlorophyll a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;67:813–820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.2.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buser CA, Diner BA, Brudvig GW. Photooxidation of cytochrome b559 in oxygen-evolving photosystem II. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11449–11459. doi: 10.1021/bi00161a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paula JC, Innes JB, Brudvig GW. Electron transfer in photosystem II at cryogenic temperatures. Biochemistry. 1985;24:8114–8120. doi: 10.1021/bi00348a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diner BA, Rappaport F. Structure, dynamics, and energetics of the primary photochemistry of photosystem II of oxygenic photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:551–580. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller P, Pascal A, Rutherford AW. β-Carotene redox reactions in photosystem II: electron transfer pathway. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6431–6440. doi: 10.1021/bi0026021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Shinopoulos KE, Tracewell CA, Focsan AL, Brudvig GW, Kispert LD. Formation of carotenoid neutral radicals in photosystem II. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:9901–9908. doi: 10.1021/jp8075832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken S, Dekker JP, Schlodder E, Witt HT. Studies on the multiphasic charge recombination between chlorophyll aII+ (P-680+) and plastoquinone QA− in photosystem II complexes. Ultraviolet difference spectrum of Chl-aII+/Chl-aII. Biochim Biophys Acta: Bioenergetics. 1989;977:52–61. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(89)80008-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley J, Deligiannakis Y, Pascal A, Faller P, Rutherford AW. Carotenoid oxidation in photosystem II. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8189–8195. doi: 10.1021/bi990633u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzwarth AR, Müller MG, Reus M, Nowaczyk M, Sander J, Rögner M. Kinetics and mechanism of electron transfer in intact photosystem II and in the isolated reaction center: pheophytin is the primary electron acceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6895–6900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505371103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilovsky D, Kerfeld CA. The orange carotenoid protein in photoprotection of photosystem II in cyanobacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta: Bioenergetics. 2012;1817:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi KV, Reifler MJ, Chisholm DA, Wang JY, Diner BA, Brudvig GW. Correlation of the cytochrome c550 content of cyanobacterial photosystem II with the EPR properties of the oxygen-evolving complex. Photosynth Res. 2002;72:175–189. doi: 10.1023/A:1016140902662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi KV, Poluektov OG, Reifler MJ, Wagner AM, Thurnauer MC, Brudvig GW. Pulsed high-frequency EPR study on the location of carotenoid and chlorophyll cation radicals in photosystem II. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5005–5014. doi: 10.1021/ja0295671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loll B, Kern J, Saenger W, Zouni A, Biesiadka J. Towards complete cofactor arrangement in the 3.0 Å resolution structure of photosystem II. Nature. 2005;438:1040–1044. doi: 10.1038/nature04224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz JG, Nixon PJ, Rogner M, Brudvig GW, Diner BA. Directed alteration of the D1 polypeptide of photosystem II: evidence that tyrosine-161 is the redox component, Z, connecting the oxygen-evolving complex to the primary electron donor, P680. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6960–6969. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon PJ, Boehm M, Michoux F, Yu J, Komenda J (2010) Recent advances in understanding the assembly and repair of Photosystem II. Ann Bot 106:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Niyogi KK. Photoprotection revisited: genetic and molecular approaches. Annu Rev Plant Phys. 1999;50:333–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noren GH, Boerner RJ, Barry BA. EPR characterization of an oxygen-evolving photosystem II preparation from the transformable cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3943–3950. doi: 10.1021/bi00230a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport F, Diner BA. Primary photochemistry and energetics leading to the oxidation of the (Mn)4Ca cluster and to the evolution of molecular oxygen in photosystem II. Coordin Chem Rev. 2008;252:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinman S, Mathis P, Conjeaud H, Stewart A. Kinetics of reduction of the primary donor of photosystem II. Influence of pH in various preparations. Biochim Biophys Acta: Bioenergetics. 1981;635:429–433. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(81)90040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer RH, Brudvig GW. Fluorescence quenching by chlorophyll cations in photosystem II. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11351–11359. doi: 10.1021/bi9709203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinopoulos KE, Brudvig GW. Cytochrome b559 and cyclic electron transfer within photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta: Bioenergetics. 2012;1817:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn PEM. O-O bond formation in the S4 state of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:9217–9227. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sproviero EM, Gascón JA, McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW, Batista VS. Computational studies of the O2-evolving complex of photosystem II and biomimetic oxomanganese complexes. Coordin Chem Rev. 2008;252:395–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DH, Brudvig GW. Cytochrome b559 of photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta: Bioenergetics. 1998;1367:63–87. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(98)00139-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DH, Cua A, Chisholm DA, Diner BA, Bocian DF, Brudvig GW. Identification of histidine 118 in the D1 polypeptide of photosystem II as the axial ligand to chlorophyll Z. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10040–10046. doi: 10.1021/bi980668e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DH, Nixon PJ, Diner BA, Brudvig GW. Assignment of the Qy absorbance bands of photosystem II chromophores by low-temperature optical spectroscopy of wild-type and mutant reaction centers. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14583–14594. doi: 10.1021/bi001246j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Q, Kuciauskas D, Lin S, Stone S, Moore AL, Moore TA, Gust D. Dynamics of photoinduced electron transfer in a carotenoid–porphyrin–dinitronaphthalenedicarboximide molecular triad. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:5214–5223. doi: 10.1021/jp970682l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang XS, Chisholm DA, Dismukes GC, Brudvig GW, Diner BA. Spectroscopic evidence from site-directed mutants of Synechocystis PCC6803 in favor of a close interaction between histidine 189 and redox-active tyrosine 160, both of polypeptide D2 of the photosystem II reaction center. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13742–13748. doi: 10.1021/bi00212a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer A, He W-Z, Barber J. Spectral resolution of more than one chlorophyll electron donor in the isolated photosystem II reaction centre complex. Biochim Biophys Acta: Bioenergetics. 1990;1017:143–151. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90145-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer A, De Las Rivas J, Barber J. β-Carotene within the isolated photosystem II reaction centre: photooxidation and irreversible bleaching of this chromophore by oxidised P680. Biochim Biophys Acta: Bioenergetics. 1991;1060:106–114. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(05)80125-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer A, Frolov D, Barber J, Robert B, Pascal A. Oxidation of the two β-carotene molecules in the photosystem II reaction center. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1008–1015. doi: 10.1021/bi026206p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LK, Brudvig GW. Cytochrome b559 may function to protect photosystem II from photoinhibition. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6653–6658. doi: 10.1021/bi00418a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LK, Miller AF, Buser CA, de Paula JC, Brudvig GW. Characterization of the multiple forms of cytochrome b559 in photosystem II. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8048–8056. doi: 10.1021/bi00446a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracewell CA, Brudvig GW. Two redox-active β-carotene molecules in photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9127–9136. doi: 10.1021/bi0345844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracewell CA, Brudvig GW. Multiple redox-active chlorophylls in the secondary electron-transfer pathways of oxygen-evolving photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11559–11572. doi: 10.1021/bi801461d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracewell CA, Cua A, Stewart DH, Bocian DF, Brudvig GW. Characterization of carotenoid and chlorophyll photooxidation in photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2001;40:193–203. doi: 10.1021/bi001992o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen JR, Kamiya N. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature. 2011;473:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature09913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Un S, Tang XS, Diner BA. 245 GHz high-field EPR study of tyrosine-D° and tyrosine-Z° in mutants of photosystem II. Biochemistry. 1996;35:679–684. doi: 10.1021/bi9523769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeglio A, Mathis P. Light-induced absorbance changes at −170 °C with spinach chloroplasts: charge separation and field effect. Biochim Biophys Acta: Bioenergetics. 1974;368:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(74)90091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrettos JS, Stewart DH, de Paula JC, Brudvig GW. Low-temperature optical and resonance Raman spectra of a carotenoid cation radical in photosystem II. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:6403–6406. doi: 10.1021/jp991464q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.