Abstract

Accomplishing autoregulation of renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate is an essential function of the renal microcirculation. While the existence of this phenomenon has been known for many years, the exact mechanisms that underlie this unique regulatory capability remain poorly understood. The work of many investigators has provided insights into many aspects of the autoregulatory mechanism, but many critical components remain elusive. This review is intended to update the reader on the role of P2 purinoceptors as a postulated mechanism responsible for renal autoregulatory resistance adjustments. It will summarize recent advances in normal function and it will touch on more recent ideas regarding autoregulatory insufficiency in hypertension and inflammation. Current thoughts on the nature of the mechanosensor responsible for myogenic behavior will be discussed as well as current thoughts on the mechanisms involved in ATP release to the extracellular fluid space.

Keywords: ATP, adenosine, afferent arterioles, P2 receptors, connexins, myogenic behavior, tubuloglomerular feedback

Introduction

Autoregulatory control is an intrinsic property of blood vessels in most vascular beds and particularly in the brain, heart and kidney [1–3]. Renal autoregulatory control is largely manifested by the preglomerular arteries and arterioles and is largely responsible for maintaining a constant glomerular capillary pressure [1, 2]. Impaired autoregulatory behavior is linked to end organ injury in many pathological settings including hypertension, diabetes, renal failure, and heart failure [2, 4–10]. Protection of glomerular capillary pressure against increases in arterial pressure is accomplished by regulation of preglomerular vascular resistance (Figure 1). In healthy kidneys, automatic adjustments in afferent arteriolar resistance occur within seconds of changes in arterial perfusion pressure. The kidney accomplishes autoregulatory behavior through the combined influences of two distinct mechanisms. The preglomerular vasculature exhibits inherent myogenic control that is intrinsic to vascular smooth muscle. In addition, renal autoregulation includes a second component with input from the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism [11]. Myogenic reactivity is clearly manifested by preglomerular arteries but is most prominent in the afferent arterioles, which are the major renal vascular resistance vessels primarily responsible for autoregulatory efficiency [2]. Tubuloglomerular feedback is a mechanism by which the macula densa senses changes in NaCl delivery in the distal tubule and releases paracrine signals that modulate afferent arteriole resistance, thus conferring an additional level of fine control over glomerular hemodynamics. The combined influences of the myogenic and tubuloglomerular feedback mechanisms, working through extracellular ATP and/or adenosine, enable the kidney to maintain a stable renal blood flow, glomerular capillary pressure and glomerular filtration rate essential to the kidney’s ability to maintain fluid and electrolyte homeostasis [11–14]. Impairment of autoregulatory capability can inappropriately elevate glomerular capillary pressure, and contribute to glomerular injury [3, 4]. This review will focus on current questions to be answered regarding the P2 receptor hypothesis and how it integrates with the tubuloglomerular feedback system.

Figure 1.

A postulated pressure-induced signaling scheme for renal autoregulatory control of afferent arteriolar resistance. Ect-5’-NT: ecto-5’-nucleotidases; TGF: tubuloglomerular feedback; RBF: renal blood flow; GFR: glomerular filtration rate, CTGF: connecting tubule glomerular feedback; (+) indicates stimulation; (−) indicates inhibition.

Purinoceptor Signaling Mechanisms and Renal Autoregulation

P2 receptors are a large family of receptors that can be divided into two structurally distinct families [15, 16]. The P2Y receptor family is represented by eight distinct receptor subtypes (P2Y1 P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11–14). More recent evaluation suggests the existence of two subfamilies with the first involving P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, and P2Y11 receptors. These receptors are coupled to Gq and stimulation leads to the activation of phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ). A second subfamily has been proposed for the P2Y12–14 receptors which appear to be coupled to Gi resulting in inhibition of adenylyl cyclase [15]. The second P2 receptor family is termed P2X receptors which were first identified in 1994. The P2X receptor family is made up of seven distinct receptor subtypes (P2X1–7) which function as ligand gated channels [16]. P2X receptors are known to play key roles in neural signaling of pain, regulation of renal blood flow and renal tubular function, vascular endothelial function and some inflammatory responses [16–18].

Autoregulatory resistance adjustments rely on calcium influx through the voltage-gated L-type calcium channels [1, 19, 20]. P2 receptor activation causes vasoconstriction by increasing the intracellular calcium concentration in vascular smooth muscle cells [21–23]. P2 purinoceptors signal specifically through activation by adenine and uridine nucleotides. Calcium responses evoked by activation of G-protein coupled P2Y receptors primarily rely on inositol trisphosphate-dependent calcium release from intracellular stores [15]. In contrast, P2X receptors are ligand-gated channels that directly influence intracellular calcium concentration through ligand-mediated sodium and calcium influx with subsequent opening of voltage-dependent calcium channels [21–23].

Adenosine signals through the modulation of intracellular cAMP levels [24]. A1 receptor activation leads to cAMP suppression and vasoconstriction, while A2 receptor activation stimulates cAMP accumulation and generally evokes vasorelaxation. A1 and A2 receptors are not generally attributed to initiating calcium signaling responses, but the more recently identified A3 receptor may be linked to calcium signaling events [24]. The clear association of voltage-dependent calcium signaling with typical autoregulatory resistance adjustments suggests that adenosine receptor activation is not a major contributor to the major resistance changes elicited by preglomerular vascular smooth muscle cells in response to increases in renal perfusion pressure. Importantly however, adenosine is reported to modulate calcium sensitivity in mouse afferent arteriolar smooth muscle cells, so adenosine-dependent modulation of calcium could be involved in regulating calcium sensitivity in mouse vascular smooth muscle and thus could influence mouse afferent arteriolar autoregulatory behavior [25].

Activation of P2X1 receptors is an essential mechanism for pressure-mediated afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction (Figure 1) [21, 22, 26]. Pharmacological blockade of P2X1 receptors or deletion of P2X1 receptors in knockout mice leads to blunted pressure-mediated afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction [26]. Furthermore, pressure-mediated afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction is lost during blockade of voltage-dependent L-type calcium channels [21]. 20-HETE has also been strongly implicated in the myogenic reactivity of many vascular beds and may be important in myogenic regulation of the afferent arteriolar autoregulatory response [27–29]. Blockade of 20-HETE with 20-HEDE, blocks P2X1 receptor mediated afferent arteriole vasoconstriction and 20-HEDE suppresses P2X1 receptor-mediated calcium signaling responses [30]. This suggests that endogenous 20-HETE is playing an important role in the calcium signaling events initiated by P2X1 receptor activation. It is also reported that 20-HETE plays an integral role in the autoregulatory response of cerebral arteries to autoregulate cerebral blood flow [31]. These more recent data suggest that 20-HETE also plays an important role in the calcium-dependent signaling events involved in renal microvascular autoregulatory responses [30].

Rho-kinase is postulated to enhance calcium sensitivity in vascular smooth muscle cells [32, 33]. Inhibition of Rho-kinase with Y-27632 significantly blunts myogenic behavior in hydronephrotic kidneys and autoregulatory reactivity in normal kidneys [34, 35]. Inhibition of Rho-kinase blunts vascular reactivity to potent vasoconstrictors such as endothelin, angiotensin II (Ang II) and the P2X1 agonist, α β-methylene ATP [32, 33, 35]. Reactive oxygen species are also known to be important modulators of vascular and microvascular reactivity [36, 37]. Rat afferent arterioles acutely exposed to TGF-β exhibited impaired pressure-mediated vasoconstriction, and the impairment was prevented during exposure of afferent arterioles to the antioxidants, apocynin or tempol [36]. In contrast, increasing lumenal pressure of isolated perfused mouse afferent arterioles enhanced superoxide production and myogenic vasoconstriction [37]. Reduction of superoxide levels can reduce renal vascular resistance, whereas increasing renal superoxide levels can lead to increased renal vascular resistance. Thus, the redox status plays an integral role in regulating renal vascular function and could be an important signaling mechanism influencing renal microvascular autoregulatory behavior.

Mechanisms of Autoregulatory Behavior

The concept that increases in transmural pressure cause vasoconstriction of preglomerular arterioles to maintain a constant renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate is based on seminal experiments investigating the hemodynamic principles required to maintain stable glomerular capillary pressure and kidney function [38, 39]. The kidney utilizes at least two, and possibly as many as four, separate mechanisms to affect renal resistance changes in response to changes in perfusion pressure, and tubular fluid flow with the two best defined mechanisms being the myogenic response and tubuloglomerular feedback (Figure 1) [13, 14, 40–42]. Evidence suggests that there is a fast acting (~5sec.) component of the autoregulatory response, ascribed to the myogenic mechanism, and then a slower (~25–60 sec.) response attributed to the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism, with the possible involvement of other mechanisms including a slower tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism (~2 min.) and a connecting tubule glomerular feedback mechanism which are postulated but not clearly resolved [13, 14, 40–42]. Furthermore, the respective contributions of these different mechanisms to the overall autoregulatory response may depend on a combination of physiological and pathophysiological mediators.

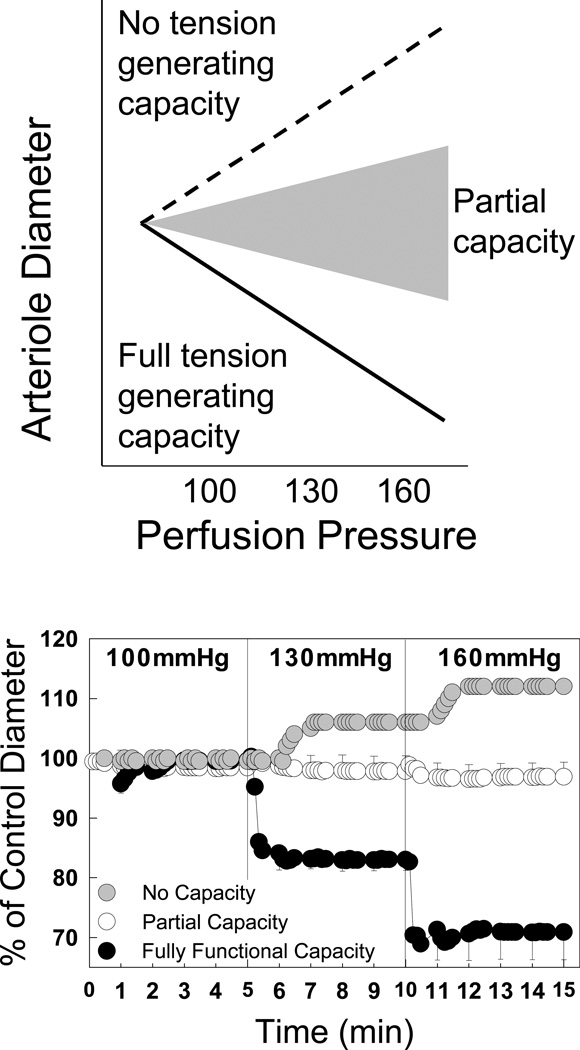

The top panel of Figure 2 illustrates a conceptual depiction of the autoregulatory response under normal conditions with two mechanisms contributing to the overall response and with all systems intact and operational. An increase in perfusion pressure should evoke an autoregulatory vasoconstriction and reduce vessel diameter to a caliber below the starting diameter (solid line). If both systems are inhibited, then an increase in perfusion pressure should yield a passive pressure-diameter relationship as illustrated by the dashed line in Figure 2. If two autoregulatory systems are contributing to increased wall tension through separate signaling mechanisms, then loss of one system should result in an intermediate pressure-diameter response depicted by the gray shaded area reflecting the contribution of a single mechanism, which provides some adjustment but the adjustment is incomplete.

Figure 2.

Conceptual view for assessment of autoregulatory responses. The upper panel depicts expected outcomes for a simple autoregulatory mechanism involving two contributing elements. The solid plot represents the expected response with both systems operating normally. The dashed plot represents the expected response with both systems inoperative. The gray shaded area represents predicted responses if just one system is inoperative. The lower panel combines actual data (black and white symbols) with hypothetical data presented by the gray symbols. Actual data are modified from previously published work [26].

Experimental data plotted in the lower panel of Figure 2 contrasts the pressure-mediated afferent arteriole autoregulatory vasoconstriction obtained in normal kidneys (black symbols), with the response obtained during P2X1 receptor blockade with NF-279 (white symbols) [26]. P2X1 receptor blockade consistently yields a flat pressure-diameter relationship, rather than the hypothetical passive relationship (gray symbols) suggesting that partial tension-generating capacity remains even though the complete autoregulatory response is not manifested. A similar flat pressure-diameter relationship has been observed in other experimental settings such as the during non-selective P2 receptor blockade, Ang II infused hypertension model, the two-kidney, one clip Goldblatt model of hypertension and during acute exposure to transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) [36, 43–46].

Additionally, Figure 3 shows that P2X1 receptor deletion in global knockout mice yields the same flat pressure-diameter profile that is observed during pharmacological P2 receptor or P2X1 receptor blockade [21, 26]. This is in marked contrast to the normal pressure-induced decline in afferent arteriole diameter observed in wild type littermate mice. Conversely, removal of the papilla, which severs the loops of Henle and thus interrupts the tubular fluid component of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism, or treatment with furosemide which inhibits the Na-K-2Cl co-transporter and thus inhibits the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism, changed the normal autoregulatory response in wild type mice to a flatter pressure-diameter relationship but had no detectable effect on the responses obtained from kidneys of P2X1 knockout mice [47]. These data suggest that P2X1 receptor blockade or deletion has only intervened in one of the two recognized mechanisms that participate in the overall autoregulatory response and supports the hypothesis that P2X receptors play an important role in the overall autoregulatory response.

Figure 3.

Effect of renal perfusion pressure changes on afferent arteriolar diameter in wild type mice (left panel) and P2X1 receptor knockout mice (right panel) before (dark symbols) and after removal of tubuloglomerular feedback by papillectomy (pap; gray symbols). Data are modified from previously published work [26].

Adenosine is another signaling molecule proposed to play a role in autoregulation of glomerular blood flow and filtration rate through tubuloglomerular feedback by activating A1 receptors [42, 48, 49]. Adenosine A1 receptor deficient mice have blunted renal blood flow autoregulation and attenuated tubuloglomerular feedback responses [49–51]. Studies have also shown that gene deletions or mutation to the ectonucleotidases that catalyze the production of adenosine from ATP accentuate tubuloglomerular feedback [52]. However, other studies have shown modest or no blunting of autoregulatory function in response to pharmacological A1 receptor blockade so the role of adenosine in overall renal autoregulation remains unclear [53, 54].

As suggested by the data above, other influences also contribute to setting afferent arteriole resistance to achieve autoregulatory control. The myogenic component of the autoregulatory response accounts for the fast response to alterations in renal perfusion pressure and is a major contributor to the overall autoregulatory response. Myogenic reactivity is an intrinsic property of vascular smooth muscle whereby increases in transmural pressure induce a reactive increase in active tension. This increase in active tension is calcium-dependent and results in a decrease in lumen diameter to provide the increase in resistance needed to offset the increase in transmural pressure and maintain a relatively constant blood flow [1]. The nature of the mechanosensor(s) that transduce(s) vascular wall stretch into vasoconstriction remain unknown.

Jernigan and Drummond have pioneered the hypothesis that epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) may serve as mechanosensors for myogenic vasoconstriction of upstream renal arteries [55]. Using siRNA targeted to the β, or γ subunits of ENaC, Jernigan et.al. showed that reducing expression of functional ENaC channels reduced the myogenic vasoconstriction induced by pressure increases in isolated renal interlobular arteries [55]. While compelling, this idea still has not been universally accepted [56]. Data reported by Wang et. al. failed to show ENaC expression in isolated afferent arterioles, calling into question the role of ENaC in regulating myogenic control of the preglomerular vasculature [56]. Furthermore, the ENaC inhibitors, amiloride and benzamil had no detectable effect on the pressure-mediated myogenic response of afferent arterioles in hydronephrotic kidneys [56]. More recent work is consistent with ENaC participating in the myogenic response. Guan et al demonstrated that the autoregulatory response of afferent arterioles was markedly blunted in kidneys where the tubuloglomerular feedback response was eliminated by papillectomy, implying that ENaC blockade indeed inhibited myogenic signals which are retained in papillectomized kidneys [57]. Additionally there is more recent work from the Drummond laboratory in mouse models that have genetic reductions in fully functional β-ENaC expression in lung, kidney and vascular smooth muscle cells. Using these animals, Ge et.al. and Grifoni et. al. showed that whole kidney autoregulatory responses were smaller in magnitude and slower to develop than in wild type litter-mates with intact β-ENaC [58, 59]. These controversies and other open questions show that more work is needed to elucidate the specifics of this purported component of the autoregulatory mechanism.

A number of other systems may contribute significantly to autoregulatory control in ways that may be dependent, or independent, of the myogenic and tubuloglomerular feedback mechanisms. Modulation of cytoskeletal elements such as integrins, gap junctions, connexins, or interactions among many of these systems could be involved [60, 61]. For example, pannexin-1 is a connexin-like protein which forms mechano-sensitive channels in the plasma membrane that facilitate the release of ATP into the extracellular fluid space where it participates in autocrine or paracrine signaling or where it can simply be broken down [62, 63]. There is also evidence that the Rho-kinase pathway contributes to renal microvascular responses to autoregulatory and vasoconstrictor signals, purportedly by increasing calcium sensitivity of the contractile proteins [64–67]. Inhibition of Rho-kinase with Y-27632 yields a concentration-dependent decline in autoregulatory behavior as well as inhibition of Ang II-dependent vasoconstriction [35]. These studies also reveal that Rho-kinase inhibition blocks P2X1 but not P2Y2 receptor–mediated vasoconstriction. Accordingly, the loss of autoregulatory control coincides with the loss of P2X1 receptor-dependent vasoconstriction providing indirect support for the postulate that P2X1 receptors are essential elements in the autoregulatory resistance cascade. The data also strongly implicate the Rho-kinase system in modulating P2X1 receptor signaling and thus may play a role in regulating the sensitivity of autoregulatory mechanisms [34, 68].

While the phenomenon of autoregulation has been accepted for many decades, work continues on understanding the mechanisms involved. Those continued efforts have led to identification of a novel new mechanism called connecting tubule glomerular feedback, or CTGF which is thought to modulate autoregulation [41, 69, 70]. CTGF is postulated to influence autoregulatory behavior by modulating tubuloglomerular feedback responses by dilating the afferent arteriole in response to increased connecting tubule NaCl delivery. The dilatory influence is thought to involve local release of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and prostaglandins but the true nature of the signal(s) has (have) not been determined [69, 70]. Consequently, CTGF could function by resetting tubuloglomerular feedback signaling to reduce tubuloglomerular feedback-dependent vasoconstriction under conditions of increased NaCl delivery to the connecting tubule.

Mechanisms of ATP Release

Many of the aforementioned mechanisms rely on signaling via the second messenger ATP in the extracellular space. Identifying a source and mechanism for extracellular ATP release is required to establish ATP, or ATP hydrolysis products as critical extracellular messenger molecules mediating pressure-dependent autoregulatory resistance adjustments. ATP is commonly released from many different cell types in response to stretch, osmotic stimuli, oxygen/nutrient status or membrane perturbation or deformation [71–75]. For the P2 receptor hypothesis in particular, the sources and mechanism(s) for increased extracellular ATP, via local autocrine or paracrine release remain to be clearly established.

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed to account for cellular release of ATP. These include vesicular ATP release and release through anion channels such as maxi-anion channels [76]. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) has been postulated to play a role in ATP transport but experiments have failed to support this hypothesis [77]. Maxi-anion channels can be activated by stretch and reportedly allow passage of ATP to the extracellular fluid space [76, 78]. The prevailing hypothesis is that transmission of autoregulatory signals utilizing ATP as a second messenger are being facilitated by both intercellular and extracellular movement of ATP via gap junctions and hemichannels formed by connexins and pannexins [60, 75, 79].

For the ATP hypothesis to be validated, it is important to demonstrate that appropriate changes in extracellular ATP occur in response to autoregulatory stimuli. Nishiyama et. al. approached this issue by determining whether or not ATP could be detected in renal cortical interstitial fluid and whether or not ATP levels fluctuate in a manner consistent with pressure-mediated autoregulatory responses [80]. Using a small surgically implanted microdialysis catheter they were able to demonstrate that ATP was present in the interstitial fluid of the renal cortex and that interstitial ATP concentrations decreased in direct proportion to decreases in renal arterial pressure, though the levels they detected in these studies were 30- to 40-fold lower than shown effective for ATP-mediated vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles [81]. This discrepancy could reflect the technical limitations of the dialysis technique, ATP stability in the dialysis fluid or in the effective ATP concentration reaching the receptor in in vitro superfusion experiments [82]. Nishiyama’s findings do support the involvement of interstitial ATP as the signaling molecule effecting autoregulation and importantly that ATP concentrations tracked appropriately with changes in arterial pressure. Of additional note, measured interstitial adenosine concentrations remain unchanged as a function of renal arterial pressure in these same studies [81].

With similar implications, Bell and colleagues show ATP release was detected adjacent to rabbit macula densa cells in response to stimuli imposed to elicit a tubuloglomerular feedback response [83]. Biosensor cells expressing P2X receptors were placed in close proximity to the basolateral surface of macula densa cells. These biosensor cells responded to tubular autoregulatory stimuli in a manner consistent with P2X receptor activation. Activation of the biosensor cell was dependent on proximity to the basolateral surface of the macula densa and was ATP dependent. Bell et. al. postulated that changes in tubular Na+ and Cl− delivery to the macula densa cells activates a depolarizing current, which is believed to activate a signaling cascade involving voltage-dependent calcium influx through nifedipine-sensitive calcium channels in the basolateral membrane which culminates in ATP release through maxi-anion channels [84, 85]. The ATP that is released stimulates P2 receptors expressed by mesangial cells and preglomerular smooth muscle cells, as well as perhaps in an autocrine fashion on the basolateral surface of macula densa cells themselves [84].

Similar work by Peti-Peterdi also examined the role of ATP signaling by the juxtaglomerular apparatus by assessing afferent arteriolar calcium wave propagation induced by tubuloglomerular feedback signals [60]. They noted that in glomeruli with attached afferent arterioles isolated from rabbits, tubuloglomerular feedback stimuli increased intracellular calcium concentration in afferent arterioles, and this response was propagated retrograde along the length of the arteriole. The response could be blocked with furosemide applied to the apical membrane of macula densa cells, which inhibits tubuloglomerular feedback. The response was also inhibited by the P2 receptor blocker, suramin, but they were unaffected by DPCPX, a selective adenosine A1 receptor antagonist. These data suggest that ATP is playing a direct role in stimulating afferent arteriole smooth muscle contraction in response to tubuloglomerular feedback signals, however they do not reveal the mechanisms by which macula densa cells may be releasing ATP.

The gap junction hypothesis posits that transmission of the ATP autoregulatory signal between the juxtaglomerular apparatus and afferent arterioles occurs via gap junctions and/or hemichannels formed from connexins. ATP has been shown to mediate calcium waves between adjacent cells by release from gap junctions and hemichannels and subsequent purinergic receptor activation [86]. Connexin 40 is highly expressed in preglomerular endothelial cells, glomerular mesangial cells and renin-containing cells of rats and mice [87]. To specifically examine the involvement of gap junctions in this signaling cascade, Peti-Peterdi utilized agents that uncouple, or block, gap junctions and examined tubuloglomerular feedback responses in afferent arterioles [60]. The gap junction blocker, heptanol, inhibited calcium wave propagation along the arteriole length. The nonspecific gap junction inhibitor, 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid, markedly blunted both the propagation of a calcium wave along the vessel length but also the initial calcium response at the afferent arteriole. 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid is also known to inhibit the function of hemi-channels and the difference between these observations implies that hemi-channels may also be a functional mechanism at the juxtaglomerular apparatus.

Hemi-channels, which are uncoupled subunits that can form gap junctions, reportedly serve as membrane pathways for ATP release into the interstitial fluid when activated by a variety of stimuli in different cell types [88]. Toma et al examined connexin expression by glomerular endothelial cells and the involvement of specific connexins, functioning as hemi-channels, in transmitting mechanical signals [61]. They reported that connexin 40 was highly expressed by cells in the juxtaglomerular region which is consistent with the findings of Wagner and coworkers, who implicate connexin 40 in the pressure-dependent control of renin secretion by juxtaglomerular cells [89]. Focusing on connexin 40, Toma et al reported that propagation of mechanical signals could be markedly inhibited when glomerular endothelial cells were pretreated with small-interfering RNA directed against connexin 40 [61]. Similar degrees of inhibition were obtained in those studies by gap junction uncoupling agents, ATP scavengers, and P2 receptor blockers.

In vitro experiments reveal that homomeric connexin 40 hemi-channels can be induced to make a calcium-dependent conformational change from an open state in low calcium media to a closed state in high calcium media [90]. This mechanism could be akin to a negative feedback loop that would induce ATP release only at a rate commensurate with maintaining a basal cell tension dependent on P2X1 receptor density and/or hemi-channel expression. In a similar mechanism, evidence shows connexin 30 forms hemi-channels in murine renal tubules which facilitates ATP release in response to changes in tubular fluid flow rate [91].

The previously mentioned pannexin-1 could also play a key role in mediating ATP release as a mechanism for autoregulation. As a connexin-like protein which forms mechano-sensitive hemi-channel like structures in the plasma membrane, this could constitute a role for ATP release by smooth muscle cells as an autocrine vascular smooth muscle component of the myogenic response [63, 65, 75].

These data are supportive of the hypothesis that hemi-channels could play an important role in transmitting myogenic and/or tubuloglomerular feedback responses to effect autoregulatory resistance adjustments. It is exciting to postulate that mechanical stimuli could induce ATP release for paracrine/autocrine signaling of vasoconstriction as an initial response to perturbations of the endothelial cell membranes caused by pressure changes along the afferent arteriole. Given that hemi-channels are present in the plasma membrane, that they are capable of forming substrate-passing pores, and the constituent protein expression has been demonstrated in these cell types, hemichannels are hypothesized to act as an autocrine/paracrine signaling component of the myogenic mechanism.

An additional mechanism that could participate in autoregulatory ATP signaling could be modulation of the rate of conversion of released ATP into adenosine by ecto-5′-nucleotidases. Either through reductions of extracellular ATP or increases in adenosine acting as a signaling molecule itself, expression of enzymes capable of catabolizing extracellular ATP could constitute another control mechanism for fine tuning overall autoregulation [92, 93]. For example, released ATP could also be hydrolyzed to adenosine, which could act on A1 receptors expressed by preglomerular smooth muscle cells. As previously mentioned, adenosine has been hypothesized to affect autoregulation through modulation of tubuloglomerular feedback. Some studies have shown that gene deletions or mutation to the ectonucleotidases that catalyze the production of adenosine result in stimulation of tubuloglomerular feedback [52, 94, 95]. These effects could be due to either a decrease in adenosine or an increase in ATP.

Renal Autoregulation in Hypertension

As we discussed in the aforementioned sections of this review, the role of renal autoregulatory capacity is to protect kidneys from transmission of high systolic blood pressure to glomeruli and therefore, prevent development of intra-glomerular hypertension and subsequent glomerular injury. Hypertension with renal injury is recognized as a major risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease. The fundamental mechanisms leading to renal injury in hypertensive subjects are complex and certainly involve numerous pathophysiological processes that are occurring simultaneously. Studies from both animal and human subjects indicate that reduction or loss of autoregulatory efficiency may initiate glomerular hyperfiltration, lead to the development of intra-glomerular hypertension, and ultimately lead to progression of renal injury in hypertension [4, 5, 7–10, 96]. For example, African Americans afflicted with essential hypertension have a higher incidence of end-stage renal disease compared to Caucasians while they also exhibit impaired autoregulation of glomerular filtration rate [5, 8]. Hypertension with impaired autoregulatory capability may put these patients at a higher risk for development of renal injury [5]. Studies in animal models also provide compelling evidence that impaired renal autoregulation in hypertension is correlated with a high incidence of compromised renal vascular and tubular function [9, 44, 45, 96–101]. Reduced, or lack of, autoregulatory efficiency are observed in several hypertensive animal models including chronic Ang II-infusion, L-NAME-induced, Dahl salt-sensitive, the Fawn Hooded rat model and two-kidney, one-clip Goldblatt hypertensive rats [9, 44–46, 96–101], but does not seem to be as clear in the spontaneously hypertensive rat model [102, 103]. Interestingly, although spontaneously hypertensive rats exhibit comparable hypertension, renal injury is less severe [104].

Accumulating evidence indicates that ATP-P2 receptor signaling not only plays a critical role in many physiological processes, it is also involved in many pathophysiological processes including inflammation, vascular remodeling, and cell proliferation and necrosis [105]. Given the ubiquitous expression of P2 receptors in kidneys, and the diverse roles of extracellular ATP signaling in regulating renal hemodynamics, microvascular function, renal autoregulation, tubular function, and sodium excretion, it is reasonable to speculate that alteration of ATP-P2 receptor signaling pathways are associated with development of hypertension and hypertensive kidney injury [18, 54, 84, 106, 106–113]. For example, P2X1, P2Y2, and P2X4 receptor deficient mice display hypertension or a significant increase in systolic blood pressure [114–116]. Besides the genetic evidence, studies in hypertensive animal models also show significant impairment of ATP-P2 receptor signaling in kidneys [100, 101, 117–122]. Chronic Ang II-infusion for 2 weeks leads to increased interstitial ATP concentrations in the renal cortex coincident with hypertension [117]. Antagonism of P2Y12 receptor activation with clopidogrel provides a renoprotective effect in Ang II-infused hypertensive rats without changing systolic blood pressure [117]. Inhibition of P2X7 receptor activation prevents hypertension and renal injury in Dahl salt-sensitive rats [119]. Genetic variation in P2X7 and P2Y2 genes has also been linked to hypertension in human subjects [123, 124]. Although the fundamental mechanisms by which ATP-P2 receptor signaling contribute to the pathophysiology of hypertension are not well understood, there may be significant differences from one hypertensive setting to another. Nevertheless, the existing data clearly suggest that there is a close link between ATP-P2 receptor signaling and hypertension.

We have focused on investigating mechanisms and signaling pathways involved in renal microvascular function and autoregulation, and the mechanisms that contribute to impaired renal autoregulatory behavior in hypertensive rat models. As shown in Figure 4, chronic Ang II-infusion for 2 weeks exhibited little to no pressure-mediated vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles compared to normotensive control Sprague-Dawley rats. These observations indicate that the ability of afferent arterioles to make appropriate adjustments in resistance in response to acute changes in renal perfusion pressure is significantly impaired. However, the attenuated autoregulatory responsiveness observed in Ang II hypertensive rats was preserved when the hypertensive response to chronic Ang II was blocked by “triple therapy” treatment (Figure 4A). The rats receiving triple therapy were normotensive despite chronic Ang II infusion and the autoregulatory response was essentially identical to control rats, suggesting that hypertension per se triggers the decline in renal autoregulatory capability [46]. Consistent with the autoregulatory impairment observed in Ang II0-infused hypertension, Zhou et al. reported that chronic Ang II infusion also markedly attenuated the afferent arteriolar response to ATP and to a selective P2X1 receptor agonist, β γ-methylene ATP [121]. In contrast, Ang II hypertensive rats maintained normal afferent arteriolar vasoconstrictor responses to the P2Y receptor agonist, UTP and adenosine [121]. The coincidence of the reduced vasoconstriction to P2X1 receptor activation and impaired pressure-mediated autoregulatory behavior in this hypertensive model highlights the possibility that impairment of autoregulatory behavior caused by Ang II infusion arises from impaired afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction to P2X1 receptor activation. The mechanisms that contribute to impaired renal autoregulatory behavior and P2X1 receptor activation however, are largely unknown. Since growing evidence shows that inflammation plays a critical role in the development of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases characteristic of patients with chronic kidney diseases, we treated Ang II hypertensive rats simultaneously with a broad spectrum, anti-inflammatory agent, pentosan polysulfate (PPS) or a specific inhibitor of lymphocyte proliferation, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) [100, 101]. We found that the decline in autoregulatory control in Ang II-infused hypertensive rats was preserved by PPS or MMF treatment (Figure 4B). Furthermore, PPS and MMF treatment preserved afferent arteriolar vasoconstrictor responses to ATP and β, γ-methylene ATP in addition to reduction of plasma TGF-β1 levels [100, 101]. MMF treatment also significantly reduced albuminuria and proteinuria. These studies provide important mechanistic information linking inflammation, specially the activation of lymphocytes in the hypertensive kidneys, and impairment of renal microvascular function with progression to hypertensive renal injury. Overall, these studies imply that intact renal autoregulation is a critical determinant of progression of renal injury in hypertension.

Figure 4.

Autoregulatory behavior of afferent arterioles in kidneys from normotensive and hypertensive rats. Chronic Ang II-infusion (60 ng/min) for 10–14 days blunted pressure-mediated vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles (white symbols). Triple therapy treatment (A) or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; B) preserved normal autoregulatory behavior of afferent arterioles in Ang II-infused hypertensive rats (gray symbols) in a pressure-dependent manner, which was indistinguishable from normal control rats (black symbols). Data are expressed as percent of control diameter at 100 mmHg during equilibration period. Values are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 indicates a significant difference from control diameter;†P<0.05 indicates a significant difference between Ang II and Ang II treated with triple therapy or MMF. Data are adapted from previously published work [46, 101].

Perspectives

The kidney constitutes less than 1% of body weight but it plays a crucial role in maintaining normal homeostasis of the body fluid and systemic blood pressure via its high filtration and reabsorption functions. One of the most remarkable features of kidney is the renal autoregulatory capacity which allows renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate to be tightly regulated within a limited range. Although the phenomenon of renal autoregulation has been recognized for many decades and the mechanisms underlying renal autoregulatory control have been extensively investigated, there are still many questions to be answered. It is uncertain exactly how renal autoregulation is altered to allow greater flexibility in managing the variability in our normal daily fluid and electrolyte intake. It is also unclear whether reduced autoregulatory efficiency occurring before renal structural changes in hypertension is a mechanism employed by the kidney to facilitate excretion of excess salt and fluid to maintain normal homeostatic balance. This reduction in autoregulatory efficiency may come at the cost of glomerular hypertension which can lead to glomerular decline. In the current review, we try to provide an update of the existing evidence and recent advances in renal autoregulation and ATP-P2 receptor signaling in hypertension. Certainly, more work needs to be conducted to advance our understanding of the potential mechanisms contributing reduced autoregulatory efficiency and the impaired P2X1 receptor-mediated renal microvascular function in hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding:

The work performed in our laboratory was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, (DK-44628, HL-074167, HL-098135) and the American Heart Association (9950513N).

References

- 1.Navar LG, Inscho EW, Majid DSA, Imig JD, Harrison-Bernard LM, Mitchell KD. Paracrine regulation of the renal microcirculation. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:425–536. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmines PK, Inscho EW, Gensure RC. Arterial pressure effects on preglomerular microvasculature of juxtamedullary nephrons. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:F94–F102. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.1.F94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis MJ, Hill MA. Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:387–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bidani AK, Griffin KA. Pathophysiology of hypertensive renal damage: Implications for therapy. Typertension. 2004;44:595–601. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000145180.38707.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer BF. Disturbances in renal autoregulation and the susceptibility to hypertension-induced chronic kidney disease. Am J Med Sci. 2004;328:330–348. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9629(15)33943-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savoia C, Schiffrin EL. Vascular inflammation in hypertension and diabetes: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Clin Sci. 2007;112:375–384. doi: 10.1042/CS20060247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parmer RJ, Stone RA, Cervenka JH. Renal hemodynamics in essential hypertension. Racial differences in response to changes in dietary sodium. Hypertension. 1994;24:752–757. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.24.6.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotchen TA, Piering AW, Cowley AW, Grim CE, Gaudet D, Hamet P, et al. Glomerular hyperfiltration in hypertensive African Americans. Hypertension. 2000;35:822–826. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffin KA, Bidani A. Hypertensive renal damage: Insights from animal models and clinical relevance. Curr Hypertension Rep. 2004;6:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s11906-004-0091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill GS. Hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertension. 2008;17:266–270. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282f88a1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldberg R, Colding-Jorgensen M, Holstein-Rathlou N-H. Analysis of interaction between TGF and the myogenic response in renal blood flow autoregulation. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:F581–F593. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.4.F581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navar LG, Inscho EW, Imig JD, Mitchell KD. Heterogeneous activation mechanisms in the renal microvasculature. Kidney Int. 1998;54:S17–S21. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Just A. Mechanisms of renal blood flow autoregulation: dynamics and contributions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1–R17. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00332.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnermann J, Briggs JP. Tubuloglomerular feedback: Mechanistic insights from gene-manipulated mice. Kidney Int. 2008;74:418–426. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Kügelgen I, Harden TK. Molecular pharmacology, physiology, and structure of the P2Y receptors. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;61:373–415. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surprenant A, North RA. Signaling at purinergic P2X receptors. Ann Rev Physiol. 2009;71:333–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyata N, Roman RJ. Role of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) in vascular system. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2005;41:175–193. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.41.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unwin RJ, Bailey MA, Burnstock G. Purinergic signaling along the renal tubule: The current state of play. News Physiol Sci. 2003;18:237–241. doi: 10.1152/nips.01436.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casellas D, Carmines PK. Control of the renal microcirculation: Cellular and integrative perspectives. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertension. 1996;5:57–63. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi K, Epstein M, Loutzenhiser R. Pressure-induced vasoconstriction of renal microvessels in normotensive and hypertensive rats: Studies in the isolated perfused hydronephrotic kidney. Circ Res. 1989;65:1475–1484. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.6.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inscho EW. P2 receptors in the regulation of renal microvascular function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F927–F944. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.6.F927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan Z, Osmond DA, Inscho EW. P2X receptors as regulators of the renal microvasculature. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:646–652. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White SM, Imig JD, Inscho EW. Calcium signaling pathways utilized by P2X receptors in preglomerular vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F1054–F1061. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.6.F1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasko G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: Therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2008;7:759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinka P, Lai EY, Fahling M, Jankowski V, Jankowski J, Schubert R, et al. Adenosine increases calcium sensitivity via receptor-independent activation of the p38/MK2 pathway in mesenteric arteries. Acta Physiol. 2008;193:37–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inscho EW, Cook AK, Imig JD, Vial C, Evans RJ. Physiological role for P2X1 receptors in renal microvascular autoregulatory behavior. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1895–1905. doi: 10.1172/JCI18499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Randriamboavonjy V, Busse R, Fleming I. 20-HETE-induced contraction of small coronary arteries depends on the activation of rho-kinase. Hypertension. 2003;41:801–806. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000047240.33861.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaley G. Regulation of vascular tone - Role of 20-HETE in the modulation of myogenic reactivity. Circ Res. 2000;87:4–5. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imig JD, Falck JR, Gebremedhin D, Harder DR, Roman RJ. Elevated renovascular tone in young spontaneously hypertensive rats: Role of cytochrome P-450. Hypertension. 1993;22:357–364. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X, Falck JR, Gopal VR, Inscho EW, Imig JD. P2X receptor-stimulated calcium responses in preglomerular vascular smooth muscle cells involves 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:1211–1217. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.070797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gebremedhin D, Lange AR, Lowry TF, Taheri MR, Birks EK, Hudetz AG, et al. Production of 20-HETE and its role in autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Circ Res. 2000;87:60–65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schubert R, Kalentchuk VU, Krien U. Rho kinase inhibition partly weakens myogenic reactivity in rat small arteries by changing calcium sensitivity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2288–H2295. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00549.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ito S, Kume H, Honjo H, Katoh H, Kodama I, Yamaki K, et al. Possible involvement of Rho kinase in Ca2+ sensitization and mobilization by MCh in tracheal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L1218–L1224. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura A, Hayashi K, Ozawa Y, Fujiwara K, Okubo K, Kanda T, et al. Vessel- and vasoconstrictor-dependent role of rho/rho-kinase in renal microvascular tone. J Vasc Res. 2003;40:244–251. doi: 10.1159/000071888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inscho EW, Cook AK, Webb RC, Jin LM. Rho-kinase inhibition reduces pressure-mediated autoregulatory adjustments in afferent arteriolar diameter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F590–F597. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90703.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma K, Cook A, Smith M, Valancius C, Inscho EW. TGF-β impairs renal autoregulation via generation of ROS. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 2005;288:F1069–F1077. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00345.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai EY, Wellstein A, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Superoxide modulates myogenic contractions of mouse afferent arterioles. Hypertensio. 2011;58:650–656. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.170472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verney EB, Starling EH. On secretion by the isolated kidney. J Physiol (Lond) 1922;56:353–358. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1922.sp002017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shipley RE, Study RS. Changes in renal blood flow, extraction of inulin, glomerular filtration rate, tissue pressure and urine flow with acute alterations of renal artery blood pressure. Am J Physiol. 1951;167:676–688. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1951.167.3.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navar LG, Inscho EW, Ibarrola AM, Carmines PK. Communication between the macula densa cells and the afferent arteriole. Kidney Int. 1991;39(Suppl. 32):S78–S82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren Y, Garvin J, Liu R, Carretero O. Cross-talk between arterioles and tubules in the kidney. Ped Nephrol. 2009;24:31. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0852-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Just A, Arendshorst WJ. A novel mechanism of renal blood flow autoregulation and the autoregulatory role of A1 adenosine receptors in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1489–F1500. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00256.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inscho EW, Cook AK, Navar LG. Pressure-mediated vasoconstriction of juxtamedullary afferent arterioles involves P2-purinoceptor activation. Am J Physiol Renal,Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1996;271:F1077–F1085. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.5.F1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inscho EW, Carmines PK, Cook AK, Navar LG. Afferent arteriolar responsiveness to altered perfusion pressure in renal hypertension. Hypertension. 1990;15:748–752. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.6.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inscho EW, Imig JD, Deichmann PC, Cook AK. Candesartan-cilexetil protects against loss of autoregulatory efficiency in angiotensin II infused rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:S178–S183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inscho EW, Cook AK, Murzynowski J, Imig JD. Elevated arterial pressure impairs autoregulation independently of AT1 receptors. J.Hypertens. 2004;22:811–818. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200404000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inscho EW, Cook AK, Imig JD, Vial C, Evans RJ. Renal autoregulation in P2X1 knockout mice. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;181:445–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnermann J, Levine DZ. Paracrine factors in tubuloglomerular feedback: Adenosine, ATP and nitric oxide. Ann Rev Physiol. 2003;65:501–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.050102.085738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hashimoto S, Huang Y, Briggs J, Schnermann J. Reduced autoregulatory effectiveness in adenosine 1 receptor-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F888–F891. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00381.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun D, Samuelson LC, Yang T, Huang Y, Paliege A, Saunders T, et al. Mediation of tubuloglomerular feedback by adenosine: Evidence from mice lacking adenosine A1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9983–9988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171317998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Traynor T, Yang TX, Huang YG, Arend L, Oliverio MI, Coffman T, et al. Inhibition of adenosine-1 receptor-mediated preglomerular vasoconstriction in AT1A receptor-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1998;275:F922–F927. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.6.F922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castrop H, Huang Y, Hashimoto S, Mizel D, Hansen P, Theilig F, et al. Impairment of tubuloglomerular feedback regulation of GFR in ecto mice-5'-nucleotidase/CD73–deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:634–642. doi: 10.1172/JCI21851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ibarrola AM, Inscho EW, Vari RC, Navar LG. Influence of adenosine receptor blockade on renal function and autoregulation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1991;2:991–999. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V25991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osmond DA, Inscho EW. P2X1 receptor blockade inhibits whole kidney autoregulation of renal blood flow in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F1360–F1368. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00016.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jernigan NL, Drummond HA. Myogenic vasoconstriction in mouse renal interlobar arteries: role of endogenous beta and {gamma}ENaC. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F1184–F1191. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00177.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X, Takeya K, Aaronson PI, Loutzenhiser K, Loutzenhiser R. Effects of amiloride, benzamil, and alterations in extracellular Na+ on the rat afferent arteriole and its myogenic response. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F272–F282. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00200.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guan Z, Pollock JS, Cook AK, Hobbs J, Inscho EW. Effect of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) blockade on the myogenic response of rat juxtamedullary afferent arterioles. Hypertension. 2009;54:1062–1069. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ge Y, Gannon K, Gousset M, Liu R, Murphey B, Drummond HA. Impaired myogenic constriction of the renal afferent arteriole in a mouse model of reduced βENaC expression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F1486–F1493. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00638.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grifoni SC, Chiposi R, McKey SE, Ryan MJ, Drummond HA. Altered whole kidney blood flow autoregulation in a mouse model of reduced β–ENaC. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F285–F292. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00496.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peti-Peterdi J. Calcium wave of tubuloglomerular feedback. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F473–F480. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00425.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toma I, Bansal E, Meer EJ, Kang JJ, Vargas SL, Peti-Peterdi J. Connexin 40 and ATP-dependent intercellular calcium wave in renal glomerular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1769–R1776. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00489.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hanner F, Lam L, Nguyen MTX, Yu A, Peti-Peterdi J. Intrarenal localization of the plasma membrane ATP channel pannexin1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F1454–F1459. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00206.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bao L, Locovei S, Dahl G. Pannexin membrane channels are mechanosensitive conduits for ATP. FEBS Letters. 2004;572:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams J, Bogwu J, Oyekan A. The role of the RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling pathway in renal vascular reactivity in endothelial nitric oxide synthase null mice. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1429–1436. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000234125.01638.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ishikawa Y, Nishikimi T, Akimoto K, Ishimura K, Ono H, Matsuoka H. Long-term administration of rho-kinase inhibitor ameliorates renal damage in malignant hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2006;47:1075–1083. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000221605.94532.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Versteilen AMG, Korstjens IJM, Musters RJP, Groeneveld ABJ, Sipkema P. Rho kinase regulates renal blood flow by modulating eNOS activity in ischemia-reperfusion of the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F606–F611. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00434.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grisk O, Schülter T, Reimer N, Zimmerman U, Katsari E, Plettenburg O, et al. The Rho kinase inhibitor SAR407899 potently inhibits endothelin-1-induced constriction of renal resistance arteries. J Hypertens. 2012;30:980–980. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328351d459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roos MH, Rodijnen WF, Lambalgen AA, Wee PM, Tangelder GJ. Renal microvascular constriction to membrane depolarization and other stimuli: Pivotal role for rho-kinase. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2006;452:471–477. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ren Y, D'Ambrosio MA, Garvin JL, Wang H, Carretero OA. Possible mediators of connecting tubule glomerular feedback. Hypertension. 2009;53:319–323. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.124545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang H, D'Ambrosio MA, Garvin JL, Ren Y, Carretero OA. Connecting tubule glomerular feedback mediates acute tubuloglomerular feedback resetting. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F1300–F1304. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00673.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Riteau N, Baron L, Villeret B, Guillou N, Savigny F, Ryffel B, et al. ATP release and purinergic signaling: A common pathway for particle-mediated inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e403. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Manohar M, Hirsh MI, Chen Y, Woehrle T, Karande AA, Junger WG. ATP release and autocrine signaling through P2X4 receptors regulate γδ T cell activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:787–794. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0312121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lazarowski ER. Vesicular and conductive mechanisms of nucleotide release. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:359–373. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suadicani SO, Iglesias R, Wang J, Dahl G, Spray DC, Scemes E. ATP signaling is deficient in cultured pannexin1-null mouse astrocytes. Glia. 2012;60:1106–1116. doi: 10.1002/glia.22338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xia J, Lim JC, Lu W, Beckel JM, Macarak EJ, Laties AM, et al. Neurons respond directly to mechanical deformation with pannexin-mediated ATP release and autostimulation of P2X7 receptors. J Physiol (Lond) 2012;590:2285–2304. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.227983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sabirov RZ, Okada Y. ATP release via anion channels. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:311–328. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-1557-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Bear CE. Purified cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) does not function as an ATP channel. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11623–11626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sabirov RZ, Okada Y. The maxi-anion channel: a classical channel playing novel roles through an unidentified molecular entity. J Physiol Sci. 2009;59:3–21. doi: 10.1007/s12576-008-0008-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wagner C. Function of connexins in the renal circulation. Kidney Int. 2008;73:547–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nishiyama A, Majid DSA, Walker M, III, Miyatake A, Navar LG. Renal interstitial ATP responses to changes in arterial pressure during alterations in tubuloglomerular feedback activity. Hypertension. 2001;37:753–759. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nishiyama A, Majid DSA, Taher KA, Miyatake A, Navar LG. Relation between renal interstitial ATP concentrations and autoregulation-mediated changes in renal vascular resistance. Circ Res. 2000;86:656–662. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.6.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Inscho EW, Ohishi K, Navar LG. Effects of ATP on pre- and postglomerular juxtamedullary microvasculature. Am J Physiol Renal,Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1992;263:F886–F893. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.5.F886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bell PD, Lapointe J-Y, Sabirov R, Hayashi S, Peti-Peterdi J, Manabe K, et al. Macula densa cell signaling involves ATP release through a maxi anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4322–4327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0736323100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bell PD, Lapointe JY, Peti-Peterdi J. Macula densa cell signaling. Ann Rev Physiol. 2003;65:481–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.050102.085730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu R, Bell PD, Peti-Peterdi J, Kovacs G, Johansson A, Persson AEG. Purinergic receptor signaling at the basolateral membrane of macula densa cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1145–1151. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000014827.71910.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cotrina ML, Lin JHC, Alves-Rodrigues A, Liu S, Li J, Azmi-Ghadimi H, et al. Connexins regulate calcium signaling by controlling ATP release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15735–15740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hanner F, Sorensen CM, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Peti-Peterdi J. Connexins and the kidney. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1143–R1155. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00808.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Faigle M, Seessle J, Zug S, El-Kasmi KC, Eltzschig HK. ATP release from vascular endothelia occurs across CX43 hemichannels and is attenuated during hypoxia. PLoS One. 2013;3:e2801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wagner C, De Wit C, Kurtz L, Grunberger C, Kurtz A, Schweda F. Connexin40 is essential for the pressure control of renin synthesis and secretion. Circ Res. 2007;100:556–563. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258856.19922.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Allen MJ, Gemel J, Beyer EC, Lal R. Atomic force microscopy of connexin40 gap junction hemichannels reveals calcium-dependent three-dimensional molecular topography and open-closed conformations of both the extracellular and cytoplasmic faces. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22139–22146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.240002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sipos A, Vargas SL, Toma I, Hanner F, Willecke K, Peti-Peterdi J. Connexin 30 deficiency impairs renal tubular ATP release and pressure natriuresis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1724–1732. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008101099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li L, Mizel D, Huang YG, Eisner C, Hoerl M, Thiel M, et al. Tubuloglomerular feedback and renal function in mice with targeted deletion of the type 1 equilibrative nucleoside transporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00581.2012. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Thompson LF. Physiological roles for ecto-5'-nucleotidase (CD73) Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Satriano J, Wead L, Cardus A, Deng A, Boss GR, Thomson SC, et al. Regulation of ecto-5'-nucleotidase by NaCl and nitric oxide: Potential roles in tubuloglomerular feedback and adaptation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F1078–F1082. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang DY, Vallon V, Zimmermann H, Koszalka P, Schrader J, Osswald H. Ecto-5'-nucleotidase (CD73)-dependent and -independent generation of adenosine participates in the mediation of tubuloglomerular feedback in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F282–F288. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00113.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Van Dokkum RP, Alonso-Galicia M, Provoost AP, Jacob HJ, Roman RJ. Impaired autoregulation of renal blood flow in the fawn-hooded rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;276:R189. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.1.R189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fitzgerald SM, Evans RG, Bergström G, Anderson WP. Renal hemodynamic responses to intrarenal infusion of ligands for the putative angiotensin IV receptor in anesthetized rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34:206–211. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Persson PB. Renal blood flow autoregulation in blood pressure control. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertension. 2002;11:67–72. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Burke M, Pabbidi MR, Fan F, Ge Y, Liu R, Williams JM, et al. Genetic basis of the impaired renal myogenic response in FHH rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00404.2012. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guan Z, Fuller BS, Yamamoto T, Cook AK, Pollock JS, Inscho EW. Pentosan polysulfate treatment preserves renal autoregulation in Ang II-infused hypertensive rats via normalization of P2X1 receptor activation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F1276–F1284. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00743.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Guan Z, Giddens MI, Osmond DA, Cook AK, Hobbs JL, Zhang S, et al. Immunosuppression preserves renal autoregulatory function and microvascular P2X1 receptor reactivity in Ang II hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00286.2012. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Arendshorst WJ, Beierwaltes WH. Renal and nephron hemodynamics in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal,Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1979;236:F246–F251. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1979.236.3.F246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arendshorst WJ. Autoregulation of renal blood flow in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res. 1979;44:344–349. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bidani AK, Polichnowski AJ, Loutzenhiser R, Griffin KA. Renal microvascular dysfunction, hypertension and CKD progression. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertension. 2013;22 doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835b36c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Burnstock G. Purinergic regulation of vascular tone and remodelling. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 2009;29:63–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.2009.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Booth JW, Tam FW, Unwin RJ. P2 purinoceptors: Renal pathophysiology and therapeutic potential. Clin Nephrol. 2012;78:154–163. doi: 10.5414/cn107325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wildman SSP, Marks J, Turner CM, Yew-Booth L, Peppiatt-Wildman CM, King BF, et al. Sodium-dependent regulation of renal amiloride-aensitive currents by apical P2 receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:731–742. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wildman SSP, Boone M, Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Contreras-Sanz A, King BF, Shirley DG, et al. Nucleotides downregulate aquaporin 2 via activation of apical P2 receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1480–1490. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vekaria RM, Unwin RJ, Shirley DG. Intraluminal ATP concentrations in rat renal tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1841–1847. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005111171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Turner CM, Vonend O, Chan C, Burnstock G, Unwin RJ. The pattern of distribution of selected ATP-sensitive P2 receptor subtypes in normal rat kidney: an immunohistological study. Cells Tissues Organs. 2003;175:105–117. doi: 10.1159/000073754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schwiebert EM, Zsembery A. Extracellular ATP as a signaling molecule for epithelial cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) -Biomembranes. 2003;1615:7–32. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bailey MA, Turner CM, Hus-Citharel A, Marchetti J, Imbert-Teboul M, Milner P, et al. P2Y receptors present in the native and isolated rat glomerulus. Nephron Physiol. 2004;96:79–90. doi: 10.1159/000076753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Guan Z, Inscho EW. Role of adenosine 5'-triphosphate in regulating renal microvascular function and in hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58:333–340. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.155952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rieg T, Bundey RA, Chen Y, Deschenes G, Junger W, Insel PA, et al. Mice lacking P2Y2 receptors have salt-resistant hypertension and facilitated renal Na+ and water reabsorption. The FASEB Journal. 2007;21:3717–3726. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8807com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mulryan K, Gitterman DP, Lewis CJ, Vial C, Leckle BJ, Cobb AL, et al. Reduced vas deferens contraction and male infertility in mice lacking P2X1 receptors. Nature. 2000;403:86–89. doi: 10.1038/47495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yamamoto K, Sokabe T, Matsumoto T, Yoshimura K, Shibata M, Ohura N, et al. Impaired flow-dependent control of vascular tone and remodeling in P2X4-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:133–137. doi: 10.1038/nm1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Graciano ML, Nishiyama A, Jackson K, Seth DM, Ortiz RM, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, et al. Purinergic receptors contribute to early mesangial cell transformation and renal vessel hypertrophy during angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F161–F169. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00281.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fürstenau CR, Ramos DB, Vuaden FC, Casali EA, Monteiro PS, Trentin DS, et al. l-NAME-treatment alters ectonucleotidase activities in kidney membranes of rats. Life Sci. 2010;87:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ji X, Hirokawa G, Weng H, Hirua Y, Takahashi R, Iwai N. P2X7 receptor antagonism attenuates the hypertension and renal injury in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:173–179. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Vonend O, Turner CM, Chan CM, Loesch A, Dell'Anna GC, Srai KS, et al. Glomerular expression of the ATP-sensitive P2X receptor in diabetic and hypertensive rat models. Kidney Int. 2004;66:157–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhao X, Cook AK, Field M, Edwards B, Zhang S, Zhang Z, et al. Impaired Ca2+ signaling attenuates P2X receptor-mediated vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles in angiotensin II hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:562–568. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000179584.39937.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Inscho EW, Cook AK, Clarke A, Zhang S, Guan Z. P2X1 receptor-mediated vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles in angiotensin II infused hypertensive rats fed a high-salt diet. Hypertension. 2011;57:780–787. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Palomino-Doza J, Rahman TJ, Avery PJ, Mayosi BM, Farrall M, Watkins H, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure is associated with polymorphic variation in P2X receptor genes. Hypertension. 2008;52:980–985. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang Z, Nakayama T, Sato N, Izumi Y, Kasamaki Y, Ohta M, et al. The purinergic receptor P2Y, G-protein coupled, 2 (P2RY2) gene associated with essential hypertension in Japanese men. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:327–335. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2009.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]