Abstract

Multifunctional nanostructures combining diagnosis and therapy modalities into one entity have drawn much attention in the biomedical applications. Herein, we report a simple and cost-effective method to synthesize a novel cubic Au nano-aggregates structure with edge-length of 80 nm (Au-80 CNAs), which display strong near-infrared (NIR) absorption, excellent water-solubility, good photothermal stability, and high biocompatibility. Under 808 nm laser irradiation for 5 min, the temperature of the solution containing Au-80 CNAs (100 μg/mL) increased by ~38 °C. The in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that Au-80 CNAs could act as both photothermal therapeutic (PTT) agents and photoacoustic imaging (PAI) contrast agents, indicating that the only one nano-entity of Au-80 CNAs shows great potentials for theranostic applications. Moreover, this facile and cost-effective synthetic method provides a new strategy to prepare stable Au nanomaterials with excellent optical properties for biomedical applications.

Keywords: Au cubic nano-aggregates, near-infrared absorption, theranostics, photothermal therapy, photoacoustic imaging.

Introduction

Metallic nanostructures (e.g., Au, Cu, and Pd) have attracted explosive attentions in the fields of catalysis 1, 2, photonics 3, and especially biomedical applications over the past decades, which trigger numerous research interests in evaluating their biological sensing 4, drug delivery 5, 6, cancer therapy 7, 8, and molecular imaging abilities 9, 10. For example, photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is a recently developed technique based on the excellent optical properties of metallic nanomaterials, which combines the advantages of high selectivity of optical imaging and high spatial resolution of ultrasonic imaging 11, 12. Moreover, the strong near-infrared (NIR) light absorption characteristics of metallic nanomaterials also promise an great potential application in photothermal therapy (PTT) with high selectivity, excellent efficacy, and minimal invasiveness compared to traditional clinical therapeutic methods (e.g., chemotherapy and radiotherapy) 13, 14. Therefore, the possibility to combine diagnosis modalities and therapy applications into metallic nanomaterials of one entity, also named as theranostics, may offer great advantages in disease management and prognosis 15-19.

Among the various kinds of available metallic nanostructures, Au nanomaterials are one of the most extensively studied platforms owing to their excellent tunable optical properties by well-controlled morphologies 20-22. Au nanomaterials with various shapes (e.g., shell, rod, star, and cage) have been exploited as exogenous PTT agents 23-27 or PAI contrast agents 28-31, which are alternatively promising strategies to efficiently diagnose and treat cancers on account of their low photobleaching, tunable surface plasmon resonance (SPR) properties, strong absorption in NIR region, and high photothermal energy conversion efficiency 32-34. Especially, gold nanoshells, (also called Auroshell, which is 155 nm in diameter with a surface coating of polyethylene glycol 5000) have been employed in the early clinic studies for the photothermal treatment of head, neck and prostate cancers 35. However, the existing shortcomings on the fabrication process and the intrinsic properties largely limit the broad applications of Au-based nanomaterials. In the case of gold nanoshells, there is a potential concern for the reason that the large shells are difficult to excrete from the body for extended periods of time 35. The use of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) in the synthesis of Au nanorods results in additional time and labor-consuming in the further purification and modification 36. In addition, the Au nanorods have weak stability under NIR irradiation since they are prone to melt and lose their efficiency 37, 38. It is an uneconomical method for the synthesis of gold nanocages when using noble metal silver as consumables 39. It is thus highly desirable to develop a facile and cost-effective strategy to fabricate photo-stable Au nanostructures with strong absorption in NIR region for PAI and PTT applications.

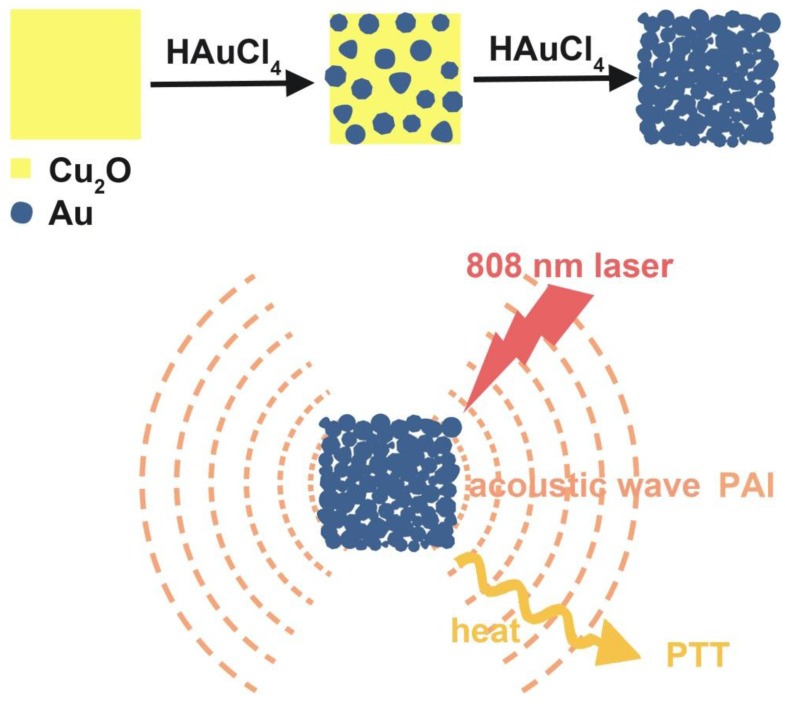

Herein, we showed a simple and cost-effective method to synthesize different sized Au cubic nano-aggregates (Au CNAs) with hollow inner space using Cu2O nanocubes as templates. The Au CNAs with average sizes of 80 nm (Au-80 CNAs) exhibited excellent water solubility without further modification because of the surface coating of amine-terminated monomethoxy polyethylene glycol (mPEG-NH2) during the formation. More importantly, the as-prepared Au-80 CNAs showed tunable absorption properties in the NIR region and excellent photothermal performance. The in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that Au-80 CNAs can act as both PTT agents for cancer therapy and PAI contrast agents for tumor imaging (Scheme 1/Figure A). These results may provide an excellent candidate of Au-based nanomaterials for efficient theranostic applications and further clinical translations.

Figure A.

(Scheme 1) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of Au-80 CNAs using Cu2O nanocubes as templates and the potential applications of Au-80 CNAs in photoacoustic imaging (PAI) and photothermal therapy (PTT).

Experimental Sections

Chemicals and materials

Hydrogen tetrachloroaurate (III) trihydrate (99.99%) (HAuCl4.3H2O) was purchased from Alfa Aesar. Amino-methoxyl polyethyleneglycol (mPEG-NH2, MW~750) was purchased from Biomatrik Inc. Ascorbic acid (AA), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4.5H2O) and other reagents were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. All chemicals were used as received without further purification. Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ∙cm) was used for all solution preparations.

Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images and elemental analysis were obtained using a HITACHI S-4800 scanning electron microscope equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and selected area electronic diffraction (SAED) images were acquired on JEM-2100 microscope at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected using a Rigaku Ultima IV X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation. The Absorption spectra were recorded by using a Varian Cary 5000 UV-vis-NIR spectrophotometer with a 1.0 cm optical path length quartz cuvette. The element analysis of Au and Cu was also carried out by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES). Photothermal assay was induced by 808 nm laser from Hi-Tech Optoelectronics Co., Ltd. Fluorescence microscope images were obtained using Axio Observer. The tumor thermographs and temperature were recorded by an infrared camera (HM-300, Guangzhou SAT Infrared Technology Co., Ltd., China). The in vivo photoacoustic imaging experiment was carried on the Endra Nexus 128 Small Animal Photoacoustic Imaging System.

Synthesis of Cu2O nanoparticles with controllable sizes

The Cu2O nanoparticles were synthesized by modifying the protocol previously reported 40. In a typical procedure, CuSO4 aqueous solution (0.02 M, 2 mL) and mPEG-NH2 (MW=750, 0.05 M) were mixed in a round bottom flask with ultrapure water under vigorous stirring at room temperature. Subsequently, NaOH (0.5 M, 3 mL) and AA (0.1 M, 1 mL) were mixed in a separate vessel with ultrapure water. The NaOH and AA mixture solution was quickly added to the round bottom flask. The reaction was allowed to perform at room temperature for 5 min under vigorous stirring. By varying the amount of mPEG-NH2, the reaction solution turned from colorless to yellow or orange and Cu2O of different sizes could be acquired (Supplementary Material: Table S1). Then the reaction was quenched by adding 40 mL of ethanol and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 7 min. After the top solution was decanted, the precipitate was washed with the mixture of H2O and ethanol (1:3) for four times to remove the unreacted chemicals and excess mPEG-NH2. The nanoparticles were redispersed in 5 mL of ultrapure water. We synthesized 70 nm Cu2O nanocubes by fixing the molar ratio of CuSO4 to mPEG-NH2 at 16:1.

Synthesis of Au cubic nano-aggregates (Au CNAs)

The freshly synthesized Cu2O nanocubes were immediately used for the preparation of Au CNAs. Briefly, 1 mL of the as-prepared Cu2O suspension was added to 10 mL of water and sonicated for 5 min. Then we added the mixture of HAuCl4 (0.4 mM) and HCl (0.8 mM) drop by drop under sonication and ice-water bath. The solution gradually changed from yellow or orange to greenish yellow, then to green and finally produced a blue colloid. The Au CNAs were separated by centrifugation, washed with distilled water and ethanol, and redispersed in water for further use. Au CNAs with different sizes could be obtained by using different sized Cu2O nanocubes as templates. By changing the molar ratio of HAuCl4/Cu2O nanocubes from 0:12 to 8:12, we could easily tune the absorption peaks from visible region to near infrared region. Au-80 CNAs (Au CNAs with edge-length of 80 nm) with the maximum absorption at ~805 nm were chosen for the following experiments.

Photothermal performance in solution

The Au-80 CNAs suspension was diluted to multiple concentrations (25, 50, or 100 μg/mL). The suspension (2 mL) of different concentrations placed in quartz cuvette was irradiated with an 808 nm laser at different power densities (2 W/cm2, 1 W/cm2 and 0.5 W/cm2) for 10 min. A thermocouple was immersed in the suspension and the temperature was measured every 30 s. To assess the photothermal stability, Au-80 CNAs (100 μg/mL) were irradiated for twice with about 1 h interval, and then we got the temperature elevation curves. The absorption spectra and the TEM images were also acquired for comparison.

Cell culture

Hep G2 cell lines were purchased from Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Hep G2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM medium with high glucose, 4.0 mM L-glutamine and 110 mg/L Sodium Pyruvate) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, from Hyclone) and antibiotics (100 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin and 0.25 μg/mL amphoterincin B, from Hyclone) at 37 °C in the humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of the Au-80 CNAs nanoparticles was tested by 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-y1)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method. Hep G2 cells were seeded onto a 96-well plate with a density of 5×103 cells per well in DMEM, and incubated in the atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were then incubated with Au-80 CNAs nanoparticles in DMEM culture medium at various concentrations for another 24 h. Subsequently, the culture medium was removed, each well was added with 100 μL new culture medium containing MTT (0.5 mg/mL) and the cells were incubated for another 4 h at 37 °C. Then the medium was removed and each well was added 200 μL DMSO. The OD492 values (Abs.) of each wells were measured by a MultiSkan FC microplate reader immediately. Cell viability was calculated from OD492 value of experimental group by subtracting that of blank group.

In vitro photothermal performance

To assess the photothermal effect on cells, Hep G2 cells were seeded onto a 96-well plate at a density of 1×104 cells per well and were allowed to incubated for 24 h. Then, the wells were divided into four groups. The three control groups included the blank, the Au-80 CNAs only and the laser irradiation only. The cells of the experiment group were incubated with 100 μL fresh medium containing 100 μg/mL Au-80 CNAs for 1h, and then irradiated on each well with an 808 nm laser at a power density of 2 W/cm2 for 5 min. The well was fully covered with laser spot. Then the cells of all groups were co-stained with both acridine orange (AO) and propidium iodide (PI). After rinsing with PBS three times, live and dead cells were imaged using Axio Observer. The cells could also be seeded in the 3.5 cm culture dish, incubated with Au-80 CNAs and partly covered with laser spot. After co-stained, a boundary between green and red could be obtained.

In vivo photothermal performance

Female Kunming mice were obtained from Laboratory Animal Center of Xiamen University and operated in compliance with the guideline for the care and use of Laboratory Animal Center of Xiamen University, China. To induce a solid tumor, S180 cells (5×106 in 100 μL PBS) were injected subcutaneously into the right rear flank areas of the mice. The mice were used when the tumor grew to ~5 mm in diameter. The S180 tumor-bearing mice were separated into four groups (five mice per group). For the experiment group (Au-80 CNAs + laser), S180 tumor-bearing mice were intratumorally injected with 120 μL of 200 μg/mL Au-80 CNAs and irradiated with the 808 nm laser at 1 W/cm2 for 5 min. The other three groups of mice were used as controls: no treatment (blank); irradiated with 808 nm laser at 1 W/cm2 for 5 min but without injection of Au-80 CNAs (laser only); intratumorally injected with 120 μL of 200 μg/mL Au-80 CNAs but without laser irradiation (Au-80 CNAs only). The laser spot was adjusted to cover the entire region of the tumor. Then the sizes of tumors were measured by a caliper every other day and the tumor volume was calculated according to equation: Tumor volume = (tumor length) × (tumor width)2 /2. Relative tumor volumes were calculated as V/V0 (V was the tumor volume calculated after treatment, while V0 was the initiated tumor volume before treatment). The photographs were also taken by the camera to record the change of the tumors.

In vivo photoacoustic imaging

The Imaging System was equipped with a tunable Nd:YAG laser pumped OPO of a pulse width of 7 ns, a repetition rate of 20 Hz. The maximum energy density of the laser was about 20 mJ per pulse, which is below the ANSI limitation for laser skin exposure. The imaging information was acquired using 128-element unfocused ultrasound transducers of 5 MHz center frequency and 3 mm diameter. The S180 tumor-bearing mice were anesthetized using chloral hydrate. Photoacoustic information of tumor areas before and after intratumoral injection of Au-80 CNAs (25 µg/mL, 50 µL) in mice was acquired under 808 nm excitation.

Result and Discussion

Synthesis of Au CNAs with controllable sizes and tunable optical properties

We prepared Au CNAs via a facile in situ reaction using Cu2O nanocubes as sacrificial templates. Firstly, we synthesized monodisperse Cu2O nanocubes by reducing copper (II) sulfate with ascorbic acid in the presence of mPEG-NH2 at room temperature 40. Then we employed the as-prepared Cu2O nanocubes as sacrificial templates to synthesize Au CNAs according to the following redox reaction 41:

| 3Cu2O + 2AuCl4- + 6H+ = 6Cu2+ + 2Au + 3H2O + 8Cl- | (1) |

After addition, the AuCl4- can be immediately reduced by Cu2O at room temperature since the standard reduction potential of AuCl4-/Au (0.99 V vs SHE) is much higher than that of Cu2+/Cu2O (0.203 V vs SHE). Based on this stoichiometric relationship, Cu2O nanocubes can completely be converted into soluble Cu2+ ions, thus leaving behind the pure Au CNAs products.

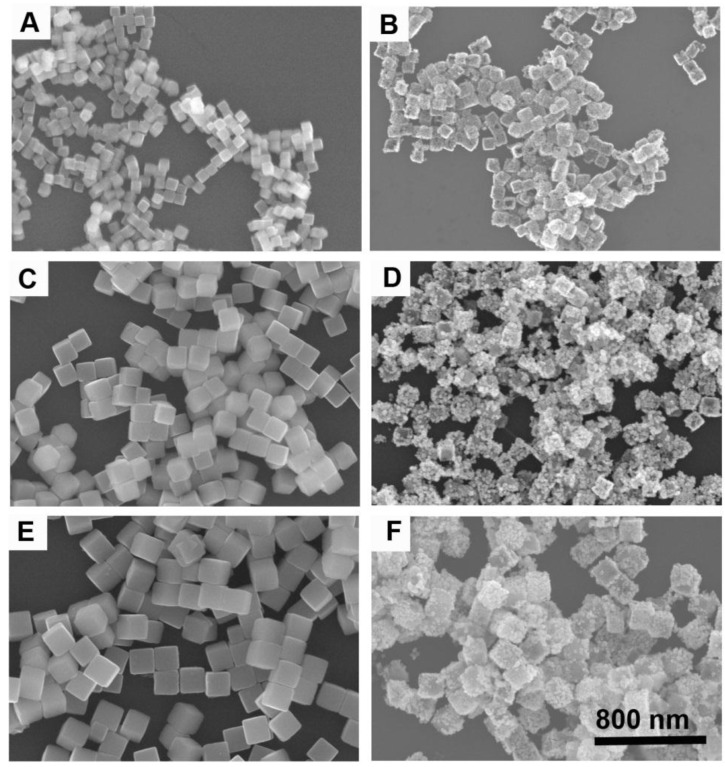

By varying the amounts of mPEG-NH2, we can synthesize Cu2O nanocubes with different sizes in a wide range from 70 to 700 nm such as the edge-length of ~70, ~120, and ~170 nm (denoted as Cu2O-70, Cu2O-120, and Cu2O-170, respectively). Using Cu2O nanocubes with different sizes as templates, we can produce Au CNAs with the size ranging from 80 to 750 nm (Figure 1 and Supplementary Material: Figure S1). For example, using Cu2O-70 as a template, we made Au CNAs with edge-length of 80 nm. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images showed that the as-prepared 70 nm Cu2O nanocubes had smooth surface. With increasing the amount of HAuCl4, the smooth Cu2O nanocubes gradually turned into the rough Au CNAs (Supplementary Material: Figure S2). Moreover, we can tune the optical properties of Au CNAs by adding different amount of HAuCl4 precursor. The pure Cu2O nanocubes solution exhibited no surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peaks in the range of 500-1200 nm, while a new absorption peak appeared at around 600 nm and gradually shifted to ~805 nm with increasing amount of HAuCl4 (Figure 2). Gold nanocrystals normally show a very intense color owing to SPR scattering, which is highly dependent on the particle size and shape 32, 42. As the number of Au nanograins in Au CNAs increases with the addition of HAuCl4 precursor, the interparticle distance between Au nanograins decreases, which results in the red shift of absorption peak 43.

Figure 1.

SEM images of Cu2O-70 (A), Cu2O-120 (C), and Cu2O-170 (E) as templates and the corresponding Au-80 CNAs (B), Au-135 CNAs (D), and Au-195 CNAs (F). All images share the same scar bar.

Figure 2.

Absorption spectra of Cu2O-70 nanocubes (A) and Au-80 CNAs with the tunable absorption peaks ~560 nm (B), ~625 nm (C), ~695 nm (D), ~750 nm (E), and ~805 nm (F), respectively, by varying the amount of HAuCl4 precursor.

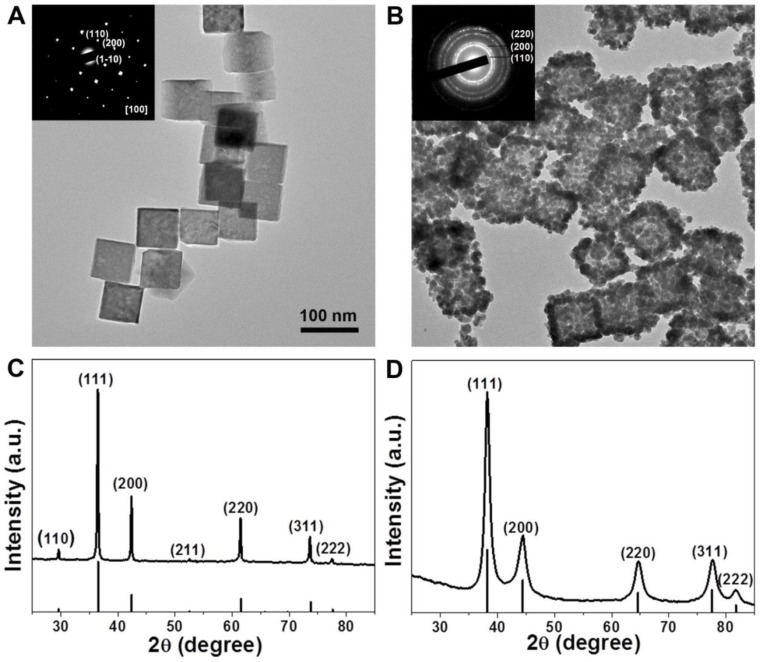

Characterization of Cu2O-70 nanocubes and Au-80 CNAs

Because the nanoparticles with sizes range from 30 to 200 nm have long circulation time by reducing the uptake of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) 44, 45, we choose 80 nm Au CNAs with the absorption peak at ~805 nm for further exploration. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Figure 3A) revealed that the as-prepared Cu2O nanocubes exhibited a well-defined cubic shape with the average edge-lengths of about 70 nm and narrow size distribution (Supplementary Material: Figure S3A). The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) and the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns indicated that the Cu2O nanocubes were single crystal with cubic structure (JCPDS card no. 01-077-0199) (Figure 3C). After the thoroughly template-sacrificing process, we made the as-synthesized Au CNAs composed of small Au nanograins with an average length of ~80 nm (denoted as Au-80 CNAs). It is worthy note of that the contrast of the center (grey) of Au-80 CNAs is lighter than its edges (dark), indicating the hollow interiors structure of Au CNAs and implying that it may exhibit the similar optical properties to Au nanocages (Figure 3B). The corresponding SAED pattern of Au CNAs displayed an interplanar spacing originating from the face centered cubic (fcc) phase of Au, indicating the polycrystalline feature of as-prepared Au-80 CNAs. The XRD pattern of Au-80 CNAs indicated a pure cubic phase of Au (JCPDS card no. 00-004-0784) without observable diffraction peaks of copper impurities (Figure 3D), which was further confirmed by the inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) and energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) measurements (Supplementary Material: Figure S4) of the Au-80 CNAs samples. These results suggested that the Cu2O nanocubes were completely converted into soluble Cu2+ species and easily removed by a simple precipitation process, which is significantly important to the biomedical applications of Au-80 CNAs. The dynamics light scatter (DLS) analysis showed that the hydrodynamic diameter (HD) of Au-80 CNAs was ~155 nm (Supplementary Material: Figure S5). The Au-80 CNAs with different concentrations exhibited broad and strong resonance absorption in the near-infrared (NIR) region. To evaluate the NIR photoabsorption capability, we calculated the molar extinction coefficient of Au-80 CNAs to be about 2.19×1010M-1∙cm-1 at 808 nm (see Supporting Information for details). The molar extinction coefficient value is higher than those of reported Au nanorods in NIR region 46, 47, indicating the potential of Au-80 CNAs to efficiently convert NIR light into heat. The absorbance intensity at 808 nm revealed a linear relationship as a function of concentration in accordance with Beer-Lambert's absorption law, which further indicated favorable dispersibility of Au-80 CNAs in aqueous solution (Supplementary Material: Figure S6).

Figure 3.

Representative TEM images of Cu2O-70 nanocubes (A) and Au-80 CNAs (B). The insets in (A) and (B) are the selected-area electronic diffraction (SAED) patterns of Cu2O-70 nanocubes and Au-80 CNAs, respectively. The X-ray diffraction patterns of Cu2O-70 nanocubes (C) and Au-80 CNAs, respectively (D).

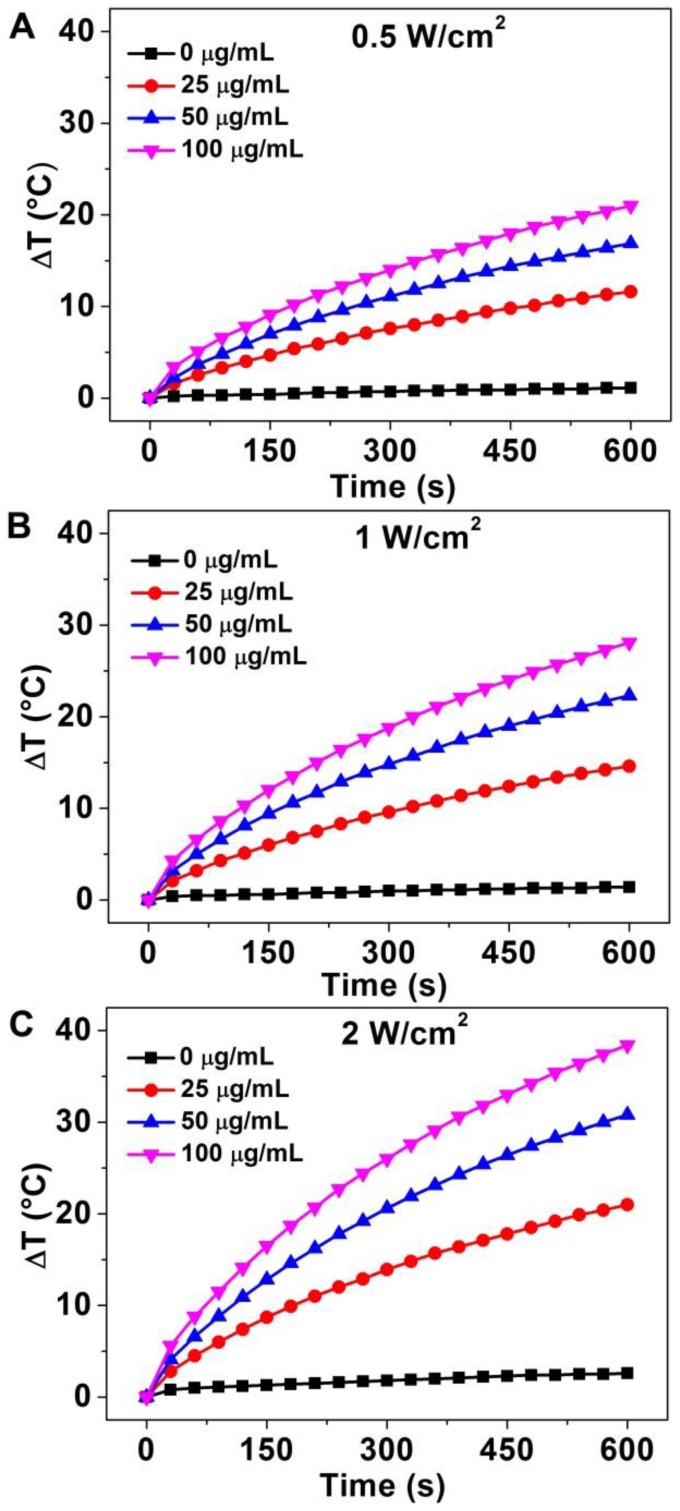

Photothermal conversion and stability of Au-80 CNAs in vitro

The strong absorption in the NIR region and excellent water-solubility make it possible to use Au-80 CNAs as photothermal conversion agents. To verify the potential of using Au-80 CNAs as a PTT agent, Au-80 CNAs solutions with different concentrations were exposed to an 808 nm NIR laser at different power densities. The heating effect of Au-80 CNAs aqueous solution increased with the enhanced concentrations and laser power density, indicating that the temperature elevation was highly dependent on the concentration and laser power density (Figure 4). For example, we observed that the irradiation of Au-80 CNAs aqueous solution even at the concentration of 25 μg/ mL and the laser power density of 0.5 W/cm2 for 10 min caused the temperature elevation of the solution as high as ~10 °C. The temperature of Au-80 CNAs aqueous solution (100 μg/ mL) increased by ~38 °C after irradiation of 808 nm laser at 2 W/cm2 for 10 min, which is much higher than that of pure water. These results confirmed that Au-80 CNAs could rapidly convert the 808 nm laser energy into environmental heat. It is well known that the temperature maintaining at 42 ~ 45 °C for 30 ~ 60 min could cause irreversible cellular damage. When the temperature rises to 50 °C, protein denaturation occurs and the irreversible cellular damage happens promptly 48. Therefore, the ability of Au-80 CNAs to induce temperature increase at low laser density suggests that Au-80 CNAs may be useful as photothermal mediators and cause irreversible damage to cancer cells and/or tissues.

Figure 4.

The temperature elevation curves of aqueous solution of Au-80 CNAs with different concentration (0, 25, 50, 100 μg/mL) as a function of irradiation time by 808 nm laser at different laser power density: (A) 0.5 W/cm2, (B) 1 W/cm2, and (C) 2 W/cm2.

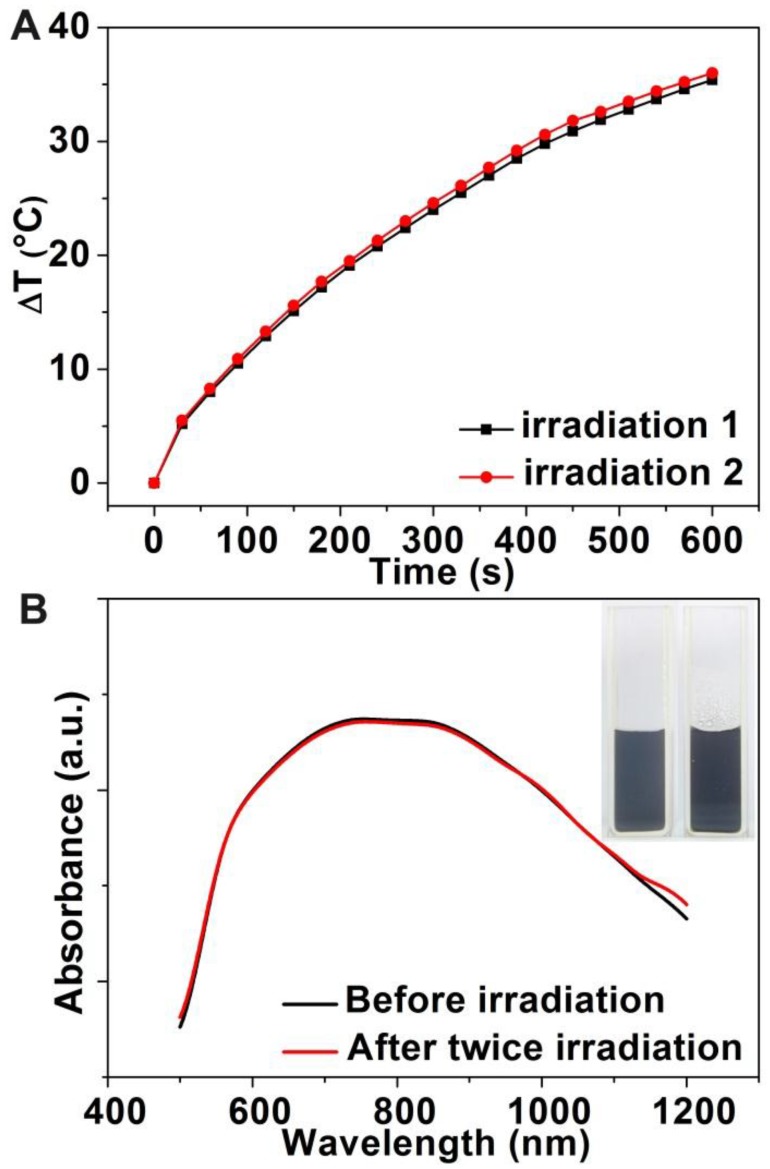

To investigate the photothermal stability of Au-80 CNAs, we tested the photothermal conversion effect of the solution and examined the morphology change of Au CNAs after the irradiation. Interestingly, there was no significant discrepancy for the temperature elevation of the same Au-80 CNAs solution between twice irradiation (Figure 5A), suggesting good photothermal stability of Au-80 CNAs. The absorption spectra (Figure 5B) indicated that the Au-80 CNAs in an aqueous solution before irradiation and after twice irradiation maintained nearly the same absorbance in NIR region. The photographs showed that Au-80 CNAs aqueous solution was transparent and well-dispersed after twice irradiation. The TEM images also displayed that the morphology of Au-80 CNAs kept intact even after twice irradiation (Supplementary Material: Figure S7). By contrary, Au nanorods were prone to melt under the irradiation of an 808 nm laser according to the previous report 37. These results imply that Au-80 CNAs with good stability and high photothermal effect can be used as promising exogenous photothermal agents for in vitro and in vivo applications.

Figure 5.

(A) The temperature elevation curves of the aqueous solution of Au-80 CNAs (100 μg/mL) for twice irradiation. (B) The absorption spectra of the Au-80 CNAs aqueous solution before irradiation and after twice irradiation (The inset is the photograph of Au-80 CNAs aqueous solution in quartz cuvette before and after twice irradiation).

In vitro cell assay

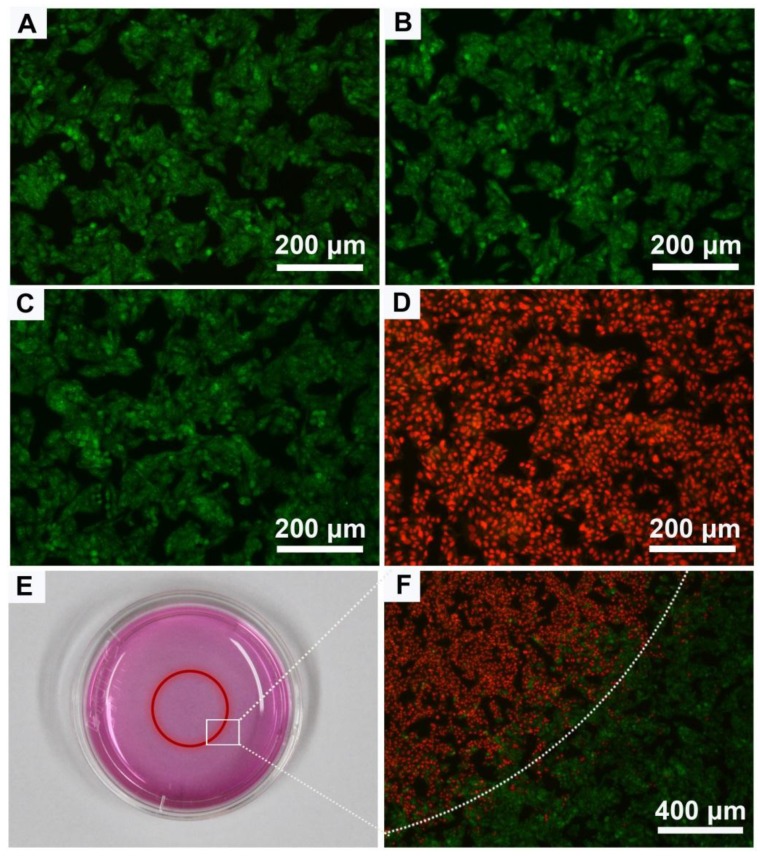

We next assessed the suitability of Au-80 CNAs as photothermal therapy agents at cellular level using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. After 24 h incubation of Hep G2 cells with the Au-80 CNAs, no apparent cytotoxicity was found even at the concentration of Au-80 CNAs as high as 200 μg/mL, demonstrating the acceptable biocompatibility of Au-80 CNAs (Supplementary Material: Figure S8). The biocompatibility is closely related with the biological inertness of Au and the mPEG-NH2 coating 49, 50. To further investigate in vitro photothermal therapy effect of Au-80 CNAs, Hep G2 cells were incubated with the Au-80 CNAs (100 μg/mL) and then exposed to an 808 nm NIR laser at 2 W/cm2 for 5 min. Three other groups including untreated, laser irradiation only treated, and Au-80 CNAs only treated cells were used as controls. After treatments, the cells were co-stained with acridine orange (AO) and propidium iodide (PI) to evaluate cell viability. AO can enter the live cells and bind to the DNA, emitting green fluorescence, while PI can only penetrate through the dead cells membrane and stain the DNA when the cell membrane is irreversibly damaged, emitting red fluorescence under excitation. The merged fluorescence images of three control groups all exhibited green fluorescence (Figure 6A-C), indicating the negligible cell destruction. The merged fluorescence images of laser and Au-80 CNAs co-treated group exhibited red fluorescence, indicating almost all of the cells were dead (Figure 6D). It could be concluded that the death of Hep G2 cells was ascribed to the photothermal effects of Au-80 CNAs instead of the cytotoxicity of the Au-80 CNAs or the single irradiation of 808 nm NIR laser. The cells partly covered with laser spot showed a boundary between green and red fluorescence in accordance with the laser spot, further confirming that Au-80 CNAs could effectively kill the cancer cells only exposure to both NIR irradiation and Au-80 CNAs (Figure 6E, F).

Figure 6.

The merged fluorescence microscope images of Hep G2 cells after different treatments: (A) blank control, (B) 100 μg/mL Au-80 CNAs only, (C) laser irradiation only, (D) combination of 100 μg/mL Au-80 CNAs and laser irradiation. (E) The photograph of cell culture dish of Hep G2 cells. The red circle shows the laser spot area. (F) The merged fluorescence image of Hep G2 cells after treatment with 100 μg/mL Au CNAs and laser irradiation in 3.5 cm dish. The cells are all co-stained by acridine orange (live: green) and propidium iodide (dead: red). Laser, 808 nm, 2 W/cm2 for 5 min.

In vivo photothermal therapy using Au-80 CNAs

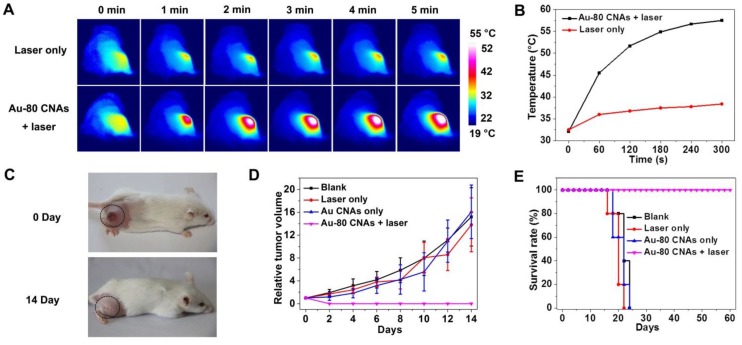

We further investigated the in vivo therapeutic effect of Au-80 CNAs. We used the Kunming mice with xenografted S180 tumors as models, and randomly divided mice into four groups (n = 5 for each group) as follows: mice untreated (blank), mice irradiated with the laser for 5 min (laser only), mice intratumorally injected with Au-80 CNAs but without laser irradiation (Au-80 CNAs only), and mice intratumorally injected with Au-80 CNAs and with laser irradiation for 5 min (Au-80 CNAs + laser). To verify the in vivo photothermal conversion effect generated by Au-80 CNAs, we used an infrared (IR) thermal mapping apparatus to record the temperature change in the tumor area. IR thermographic images of mice showed that the temperature in tumor site could rapidly reach to 57.5 °C in the presence of Au-80 CNAs upon the NIR laser illumination within 5 min. In comparison, the maximum temperature of the tumor surface in the laser only group was only about 38.5 °C under the same irradiation condition, demonstrating that Au-80 CNAs played a key role in the generation of heat (Figure 7A, B). The temperature exceeding 50 °C would cause an irreversible damage to the cells and tissues. The subsequent hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of tumor tissues indicated that there was no obvious destruction in the tumors after single treatment of either the laser or Au-80 CNAs; however, tumors exhibited the cells karyolysis and cytoplasmic acidophilia after both Au-80 CNAs and laser treatments (Supplementary Material: Figure S9). This result confirmed that only Au-80 CNAs under irradiation could generate enough heat and damage the cancer cells and tissues irreversibly 51. To verify the photothermal theraputic efficacy of Au-80 CNAs, we monitored mice tumor growth rates and the mice survival rates. The tumor tissues after single treatment of injected with Au-80 CNAs or irradiated with NIR laser all continuously grew and showed no significant difference of tumor growth compared to the untreated control group mice. The rapid growth led to the necrosis within tumors, and finally caused the death of mice. However, the mice after treatment of both Au-80 CNAs and 808 nm laser irradiation showed seriously empyrosis in tumor areas and resulted in a significant suppression of tumor growth. The black burning scab detached from the skin after 14 days, and the mice completely recovered (Figure 7C, D and Supplementary Material: Figure S10). The inhibition of tumor growth in mice treated with the combination of Au-80 CNAs and NIR laser lead to a significantly survival superiority. The recovered mice survived without tumor recurrence over 60 days. However, the tumors in other 3 groups grew rapidly and lead to the death of mice in no more than 25 days (Figure 7E). These results confirm that Au-80 CNAs would be efficient PTT agents which cause cancer cells death and tumor tissues injury through the conversion of the strongly absorbed NIR light to sufficient thermal energy.

Figure 7.

(A) IR thermographs at the time points of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 min of the mice tumor sites without (upper row) and with (lower row) intratumoral injection of Au-80 CNAs with irradiation by 808 nm laser at 1 W/cm2. (B) Temperature change of the mice tumor sites as the function of irradiation time. (C) The digital photographs of S180 tumor-bearing mice taken at 0 day before treatments and 14 days after treatments of Au-80 CNAs + laser (intratumorally injected 120 μL of 200 μg/mL Au-80 CNAs and then immediately exposed to 808 nm laser at 1 W/cm2 for 5 min). (D) Relative tumor volume change of the S180 tumor-bearing mice of different groups after treatments. (E) The survival rate curves of S180 tumor-bearing mice of different groups after treatments.

In vivo photoacoustic imaging by Au-80 CNAs

PAI can reveal a wide variety of endogenous absorbers in biological systems, such as DNA/RNA, hemoglobin, melanin. To visualize and distinguish the tumor tissues from normal tissues by PAI, an exogenous contrast agent will be required 28-30. Apart from the excellent in vitro photothermal performance and favorable in vivo therapeutic effect, Au-80 CNAs with strong NIR absorption also serve as an excellent candidate for PAI contrast enhancement. We tested the contrast ability in mice tumors after intratumoral injection of 50 µL of Au-80 CNAs (25 µg/mL). The photoacoustic signal in the region of interest (ROI) increased about 4-fold compared with that of the same region before injection, suggesting the feasibility of Au-80 CNAs for PAI contrast enhancement and diagnostic applications (Figure 8A, B). Au-80 CNAs, one nano-entity with the excellent photothermal theraputic effect and the enhanced photoacoustic contrast ability, can provide an important and promising platform for cancer theranostics 52-54.

Figure 8.

Representative in vivo photoacoustic images of tumor areas before (A) and after (B) injection of Au-80 CNAs (25 μg/mL, 50 μL) in mice tumors. Laser: 808 nm.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated that a novel Au cubic nano-aggregate structure could serve as a potential theranostic agent. The as-synthesized Au-80 CNAs with intense NIR absorption exhibit good photo-stability, excellent photothermal effect, and high biocompatibility, which allow Au-80 CNAs (only one entity) to act as an in vivo exogenous agent for both PAI and PTT applications. The synthesis of size-controllable Au CNAs is facile, cost-effective, highly reproducible, and amenable to scale up. We thus believe that the powerful and stable dual-functional metallic Au CNAs hold a great promise for biomedical applications, particularly cancer imaging and therapy.

Supplementary Material

Table S1, Fig.S1 - Fig.S10.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (2013CB933901 and 2014CB744502), National Natural Science Foundation of China (21222106, 81370042, 81000662, and 81201805), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian (2013J06005 and 2013D014), Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-10-0709), and Projects of Xiamen Science and Technology Program (3502Z20130030).

References

- 1.Li Y, Somorjai GA. Nanoscale advances in catalysis and energy applications. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2289–95. doi: 10.1021/nl101807g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou X, Xu W, Liu G. et al. Size-dependent catalytic activity and dynamics of gold nanoparticles at the single-molecule level. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:138–46. doi: 10.1021/ja904307n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudiksen MS, Lauhon LJ, Wang J. et al. Growth of nanowire superlattice structures for nanoscale photonics and electronics. Nature. 2002;415:617–20. doi: 10.1038/415617a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li CZ, Liu Y, Luong JH. Impedance sensing of DNA binding drugs using gold substrates modified with gold nanoparticles. Anal Chem. 2005;77:478–85. doi: 10.1021/ac048672l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng Y, A CS, Meyers JD. et al. Highly efficient drug delivery with gold nanoparticle vectors for in vivo photodynamic therapy of cancer. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10643–7. doi: 10.1021/ja801631c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh P, Han G, De M. et al. Gold nanoparticles in delivery applications. ADV DRUG DELIVER REV. 2008;60:1307–15. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickerson EB, Dreaden EC, Huang X. et al. Gold nanorod assisted near-infrared plasmonic photothermal therapy (PPTT) of squamous cell carcinoma in mice. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang S, Huang P, Nie L. et al. Single continuous wave laser induced photodynamic/plasmonic photothermal therapy using photosensitizer-functionalized gold nanostars. Adv Mater. 2013;25:3055–61. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheong S, Ferguson P, Feindel KW. et al. Simple synthesis and functionalization of iron nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:4206–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H, Zhang X, Dai S. et al. Multifunctional gold nanostar conjugates for tumor imaging and combined photothermal and chemo-therapy. Theranostics. 2013;3:633–49. doi: 10.7150/thno.6630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang LV, Hu S. Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science. 2012;335:1458–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1216210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Pang Y, Ku G. et al. Noninvasive laser-induced photoacoustic tomography for structural and functional in vivo imaging of the brain. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:803–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lal S, Clare SE, Halas NJ. Nanoshell-enabled photothermal cancer therapy: impending clinical impact. Accounts Chem Res. 2008;41:1842–51. doi: 10.1021/ar800150g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zha Z, Yue X, Ren Q. et al. Uniform polypyrrole nanoparticles with high photothermal conversion efficiency for photothermal ablation of cancer cells. Adv Mater. 2013;25:777–82. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao J, Gu H, Xu B. Multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles: design, synthesis, and biomedical applications. Accounts Chem Res. 2009;42:1097–107. doi: 10.1021/ar9000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreaden EC, El-Sayed MA. Detecting and destroying cancer cells in more than one way with noble metals and different confinement properties on the nanoscale. Accounts Chem Res. 2012;45:1854–65. doi: 10.1021/ar2003122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardhan R, Lal S, Joshi A. et al. Theranostic nanoshells: from probe design to imaging and treatment of cancer. Accounts Chem Res. 2011;44:936–46. doi: 10.1021/ar200023x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao Q, Zheng X, Bu W. et al. A core/satellite multifunctional nanotheranostic for in vivo imaging and tumor eradication by radiation/photothermal synergistic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:13041–8. doi: 10.1021/ja404985w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menon JU, Jadeja P, Tambe P. et al. Nanomaterials for photo-based diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Theranostics. 2013;3:152–66. doi: 10.7150/thno.5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain PK, Huang X, El-Sayed IH. et al. Noble metals on the nanoscale: optical and photothermal properties and some applications in imaging, sensing, biology, and medicine. Accounts Chem Res. 2008;41:1578–86. doi: 10.1021/ar7002804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreaden EC, Alkilany AM, Huang X. et al. The golden age: gold nanoparticles for biomedicine. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2740–79. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15237h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Wang C, Cheng L. et al. Noble metal coated single-walled carbon nanotubes for applications in surface enhanced Raman scattering imaging and photothermal therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7414–22. doi: 10.1021/ja300140c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirsch LR, Stafford RJ, Bankson JA. et al. Nanoshell-mediated near-infrared thermal therapy of tumors under magnetic resonance guidance. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:13549–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Qian W. et al. Cancer cell imaging and photothermal therapy in the near-infrared region by using gold nanorods. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2115–20. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Glaus C, Laforest R. et al. Gold nanocages as photothermal transducers for cancer treatment. Small. 2010;6:811–7. doi: 10.1002/smll.200902216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye E, Win KY, Tan HR. et al. Plasmonic gold nanocrosses with multidirectional excitation and strong photothermal effect. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8506–9. doi: 10.1021/ja202832r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong W, Li Y, Niu D. et al. Facile synthesis of monodisperse superparamagnetic Fe3O4 Core@hybrid@Au shell nanocomposite for bimodal imaging and photothermal therapy. Adv Mater. 2011;23:5392–7. doi: 10.1002/adma.201103521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim C, Cho EC, Chen J. et al. In vivo molecular photoacoustic tomography of melanomas targeted by bioconjugated gold nanocages. Acs Nano. 2010;4:4559–64. doi: 10.1021/nn100736c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Xie X, Wang X. et al. Photoacoustic Tomography of a Nanoshell Contrast Agent in the in Vivo Rat Brain. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1689–92. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jokerst JV, Thangaraj M, Kempen PJ. et al. Photoacoustic imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in living mice via silica-coated gold nanorods. Acs Nano. 2012;6:5920–30. doi: 10.1021/nn302042y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang YS, Wang Y, Wang L. et al. Labeling human mesenchymal stem cells with gold nanocages for in vitro and in vivo tracking by two-photon microscopy and photoacoustic microscopy. Theranostics. 2013;3:532–43. doi: 10.7150/thno.5369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu M, Chen J, Li ZY. et al. Gold nanostructures: engineering their plasmonic properties for biomedical applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:1084–94. doi: 10.1039/b517615h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia Y, Li W, Cobley CM. et al. Gold nanocages: from synthesis to theranostic applications. Accounts Chem Res. 2011;44:914–24. doi: 10.1021/ar200061q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin Y. Multifunctional Compact Hybrid Au Nanoshells: A New Generation of Nanoplasmonic Probes for Biosensing, Imaging, and Controlled Release. Accounts Chem Res. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ar400086e. doi: 10.1021/ar400086e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gad SC, Sharp KL, Montgomery C. et al. Evaluation of the toxicity of intravenous delivery of auroshell particles (gold-silica nanoshells) Int J Toxicol. 2012;31:584–94. doi: 10.1177/1091581812465969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Black KC, Luehmann H. et al. Comparison study of gold nanohexapods, nanorods, and nanocages for photothermal cancer treatment. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2068–77. doi: 10.1021/nn304332s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Link S, Burda C, Mohamed MB. et al. Laser Photothermal Melting and Fragmentation of Gold Nanorods: Energy and Laser Pulse-Width Dependence. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 1999;103:1165–70. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Ai K, Liu J. et al. Dopamine-Melanin Colloidal Nanospheres: An Efficient Near-Infrared Photothermal Therapeutic Agent for In Vivo Cancer Therapy. Adv Mater. 2013;25:1353–9. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skrabalak SE, Au L, Li X. et al. Facile synthesis of Ag nanocubes and Au nanocages. NAT PROTOC. 2007;2:2182–90. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gou L, Murphy CJ. Controlling the size of Cu2O nanocubes from 200 to 25 nm. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:735. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu XW. Selective growth of Au nanoparticles on (111) facets of Cu2O microcrystals with an enhanced electrocatalytic property. Langmuir. 2011;27:9100–4. doi: 10.1021/la2020447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy CJ, Gole AM, Stone JW. et al. Gold Nanoparticles in Biology Beyond Toxicity to Cellular Imaging. Accounts Chem Res. 2008;41:1721–30. doi: 10.1021/ar800035u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elghanian R, Storhoff JJ, Mucic RC. et al. Selective colorimetric detection of polynucleotides based on the distance-dependent optical properties of gold nanoparticles. Science. 1997;277:1078–81. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petros RA, DeSimone JM. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. NAT REV DRUG DISCOV. 2010;9:615–27. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albanese A, Tang PS, Chan WC. The effect of nanoparticle size, shape, and surface chemistry on biological systems. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2012;14:1–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071811-150124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orendorff CJ, Murphy CJ. Quantitation of metal content in the silver-assisted growth of gold nanorods. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:3990–4. doi: 10.1021/jp0570972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liao H, Hafner JH. Gold Nanorod Bioconjugates. Chem Mater. 2005;17:4636–41. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Habash RW, Bansal R, Krewski D. et al. Thermal therapy, part 1: an introduction to thermal therapy. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;34:459–89. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v34.i6.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sperling RA, Rivera Gil P, Zhang F. et al. Biological applications of gold nanoparticles. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1896–908. doi: 10.1039/b712170a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu WW, Chang E, Falkner JC. et al. Forming biocompatible and nonaggregated nanocrystals in water using amphiphilic polymers. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2871–9. doi: 10.1021/ja067184n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou M, Zhang R, Huang M. et al. A Chelator-Free Multifunctional [64Cu]CuS Nanoparticle Platform for Simultaneous Micro-PET CT Imaging and Photothermal Ablation Therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15351–8. doi: 10.1021/ja106855m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santra S, Kaittanis C, Santiesteban OJ. et al. Cell-specific, activatable, and theranostic prodrug for dual-targeted cancer imaging and therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16680–8. doi: 10.1021/ja207463b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ke H, Wang J, Dai Z. et al. Gold-nanoshelled microcapsules: a theranostic agent for ultrasound contrast imaging and photothermal therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:3017–21. doi: 10.1002/anie.201008286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Z, Wang J, Chen C. Gold nanorods based platforms for light-mediated theranostics. Theranostics. 2013;3:223–38. doi: 10.7150/thno.5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1, Fig.S1 - Fig.S10.