Abstract

Arsenic-containing lipids (arsenolipids) are natural products present in fish and algae. Because these compounds occur in foods, there is considerable interest in their human toxicology. We report the synthesis and characterization of seven arsenic-containing lipids, including six natural products. The compounds comprise dimethylarsinyl groups attached to saturated long-chain hydrocarbons (three compounds), saturated long-chain fatty acids (two compounds), and monounsaturated long chain fatty acids (two compounds). The arsenic group was introduced through sodium dimethylarsenide or bis(dimethylarsenic) oxide. The latter route provided higher and more reproducible yields, and consequently, this pathway was followed to synthesize six of the seven compounds. Mass spectral properties are described to assist in the identification of these compounds in natural samples. The pure synthesized arsenolipids will be used for in vitro experiments with human cells to test their uptake, biotransformation, and possible toxic effects.

Introduction

The presence of arsenic in lipid extracts of fish and algae was first reported in the late 1960s,1 but their structures remained unknown. Subsequent biochemical studies in 1978 showed that arsenic-containing lipids (arsenolipids) in unicellular algae comprised three main lipid types,2 and the same compounds were then reported in clam tissues as a consequence of an algal–clam symbiosis.3 Enzymatic studies with phospholipases demonstrated that two of the three lipid types were arsenic-containing phospholipids,2 but a tentative structure proposed for the polar arsenic-containing head group was later shown to be incorrect.4,5 Although it was clear that the third lipid type was not a phospholipid, no additional information could be gleaned from the biochemical experiments.

In 1988, the major arsenolipid in the brown macroalga Undaria pinnatifida was purified and its structure established as a phospholipid with an arsenosugar head group.6 This structure seemed to fit the properties of two of the three lipid types described in the biochemical studies,2 and was consistent with the earlier observation that arsenosugars were the major water-soluble arsenical constituents of algae.7 In 2008, arsenolipids that were not based on phospholipids were first reported in fish oils;8,9 these compounds, which contained arsenic bound directly to either a long chain fatty acid or a hydrocarbon, matched the properties of those compounds in the third lipid type, which were not changed by treatment with phospholipases. Subsequent work by several independent groups has extended the number of arsenolipids to more than 40 compounds.10−20 The structures of the arsenolipids have been proposed primarily on the basis of mass spectrometric data, and brief synthetic details were reported for one of the compounds.8 These compounds appear to be unrelated to the unique (lipid-soluble) polycyclic arsenic compound identified in a sponge21 and recently synthesized.22

Because arsenolipids can occur at high levels in edible fish,10−13 and they had been shown to be bioavailable to humans and to be extensively degraded to small arsenic species,23,24 interest has turned to the possible toxic properties of these lipids. To address the ensuing human health concerns, we have undertaken a project employing human cells to investigate the bioavailability, toxicity, and biotransformation of arsenolipids. To perform these experiments, sufficient material of a range of arsenolipids was required to study their biological activity. We report the synthetic approaches to seven arsenolipids, including six naturally occurring compounds that will undergo toxicological testing. Moreover, we present a mass spectrometric analysis of the compounds to facilitate their detection in natural samples.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Arsenolipids

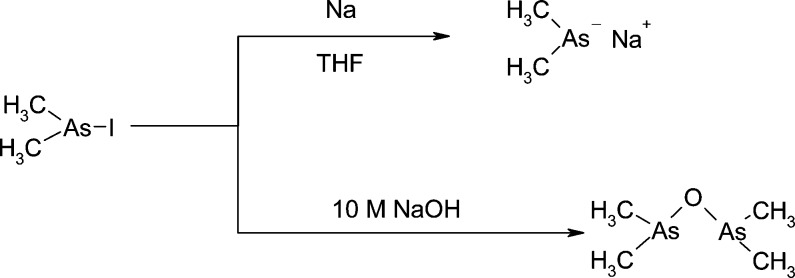

Synthetic schemes for several water-soluble arsenic-containing natural products have been reported.25,26 Trimethylated quaternary arsonium compounds have usually been prepared by nucleophilic substitution, whereby trimethylarsine is heated with a brominated substrate. The dimethylated arsinyl compounds (Me2As(O)−), however, are commonly prepared using the reactive sodium dimethylarsenide on the basis of the method of Feltham et al.27 Although this procedure has been successfully applied to the synthesis of dimethylarsinylribosides,28 the reaction is difficult to monitor and often suffers from low and variable yields.26 Nevertheless, we tried this approach for the synthesis of compound 5 (Figure 1; As-HC 332), whereby reaction of the tosylate of pentadecanol with sodium dimethylarsenide produced the arsine, which was oxidized without purification to the desired compound obtained in 15% overall yield. The final cleanup step involved the novel use of Dowex 50 (a cation-exchange polymer)/MeOH and elution with an ammonia/MeOH mixture, which takes advantage of the cationic properties of the easily protonated Me2AsO– group. Although this approach with dimethylarsenide (Scheme 1) was successful for As-HC 332 (14 methylenes), attempts to perform the nucleophilic substitution by Me2AsNa on increasingly longer carbon-chain analogues produced progressively lower yields. Hence, an alternative approach was investigated.

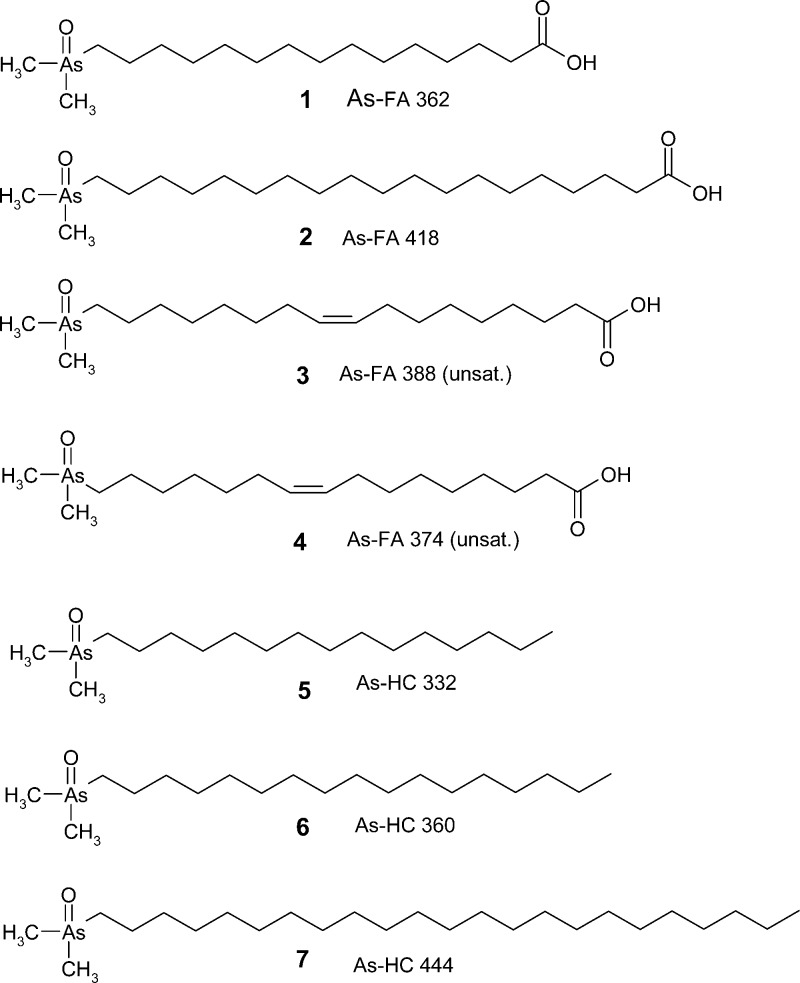

Figure 1.

The seven arsenolipids synthesized in this study. To assist their recognition in the text, the compounds are referred to by the coding As-FA (arsenic fatty acid) and As-HC (arsenic hydrocarbon) followed by their molecular mass.

Scheme 1. Two Approaches for Forming the Intermediate Used To Introduce the Dimethylarsenic Group.

The second synthetic approach (Scheme 1) involved the simple reaction of iododimethylarsine in concentrated NaOH to form bis(dimethylarsenic) oxide ((Me2As)2O) and then addition of the brominated compound. This procedure gave consistent yields of the desired arsenic product. The mixture was stirred and heated overnight and then cooled and washed with ether. The aqueous layer was neutralized (As-hydrocarbons) or acidified (As- fatty acids), and the arsenolipids were extracted into chloroform and crystallized from ethyl acetate. In this way, the saturated arsenic-containing hydrocarbons 6 and 7 (As-HC 360 and As-HC 444) and the saturated arsenic-containing fatty acids 1 and 2 (As-FA 362 and As-FA 418) were prepared in yields ranging from 37 to 88%.

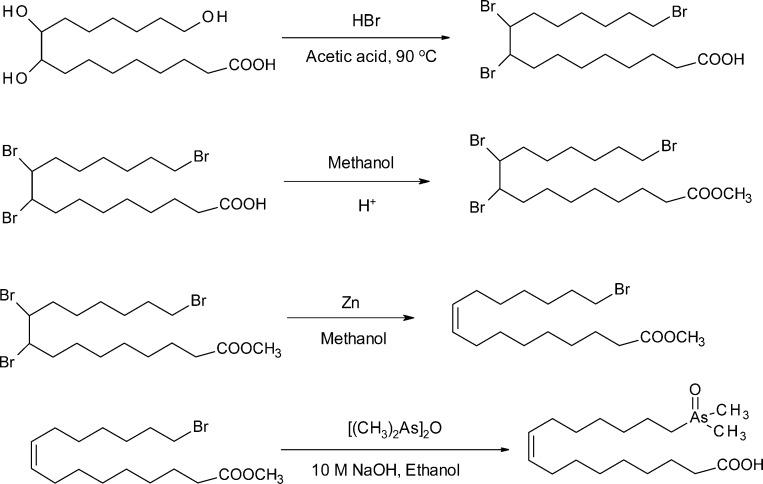

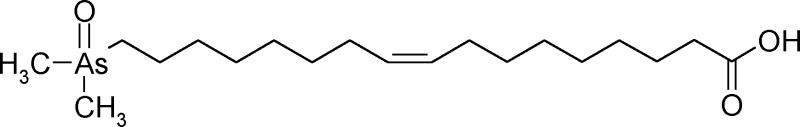

The syntheses of the unsaturated arsenic fatty acids were more complex. Our initial aim was to prepare compound 4 (As-HC 374) as a model compound because it presented an easier synthetic target than the natural product 3 (As-HC 388). Furthermore, because As-HC 374 is not a natural product but differs by only one methylene group from a significant natural product, it could serve as a useful internal standard for performing checks on the various analytical steps needed to determine arsenolipids in natural samples. Thus, treatment of aleuritic acid (9,10,16-trihydroxypalmitic acid) with HBr in acetic acid gave the tribrominated carboxylic acid, which was esterified and selectively debrominated (Zn/methanol) to give the monounsaturated ester. Treatment with (Me2As)2O in the usual way gave the desired arsenic-containing carboxylic acid (4, As-FA 374) in 32% overall yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 16-Dimethylarsinyl-9-hexadecenoic Acid (4, As-FA 374).

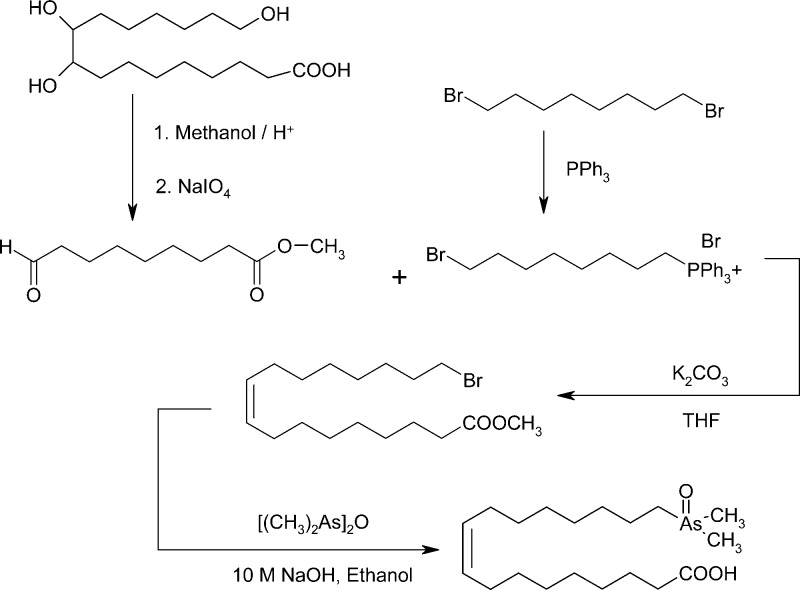

The procedure employed for As-FA 374, however, was not feasible for As-FA 388 (compound 3) because there was no equivalent readily available starting material. Instead, esterification of the trihydroxy carboxylic acid (Scheme 3) followed by treatment with sodium periodate gave the aldehyde. Treatment of 1,8-dibromooctane with PPh3 gave the phosphonium salt, which was reacted with the aldehyde to give 17-bromo-9-heptadecenoic acid methyl ester. Introduction of the Me2As(O) group in the usual way yielded the desired monounsaturated arsenic-containing fatty acid 3 (As-FA 388) in 11% overall yield.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 17-Dimethylarsinyl-9-heptadecenoic Acid (3, As-FA 388).

HPLC/ICPMS and Molecular Mass Spectral Characterization of Arsenolipids

The recent advance in our knowledge of arsenolipids has been provided primarily by HPLC/mass spectrometry measurements. The general approach is first to obtain an “arsenic profile” of the sample by using HPLC coupled to an elemental mass spectrometer such as an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICPMS) and a molecular mass profile of the intact molecules by using HPLC/electrospray mass spectrometry. Often, both HPLC profiles are obtained simultaneously from the same chromatographic run by splitting the effluent flow from the HPLC column between the two mass spectrometers. High-resolution mass spectrometry can also be used to provide molecular formulas with high precision, opening the possibility of assigning a structure which can then be confirmed by synthesis. The mass deficiency of arsenic is an advantage because when one arsenic atom is included in possible formulas, the range of likely candidates is restricted, and often there is only one plausible formula. In this way, arsenolipids have been identified in fish oil,8,9,18,20 fish liver,10,19 sashimi tuna fillets,11 other fish,13 and algae.14,16 To assist with future determinations of arsenolipids, we report here results from some HPLC/ICPMS and tandem mass spectrometry measurements performed with a high-resolution mass analyzer.

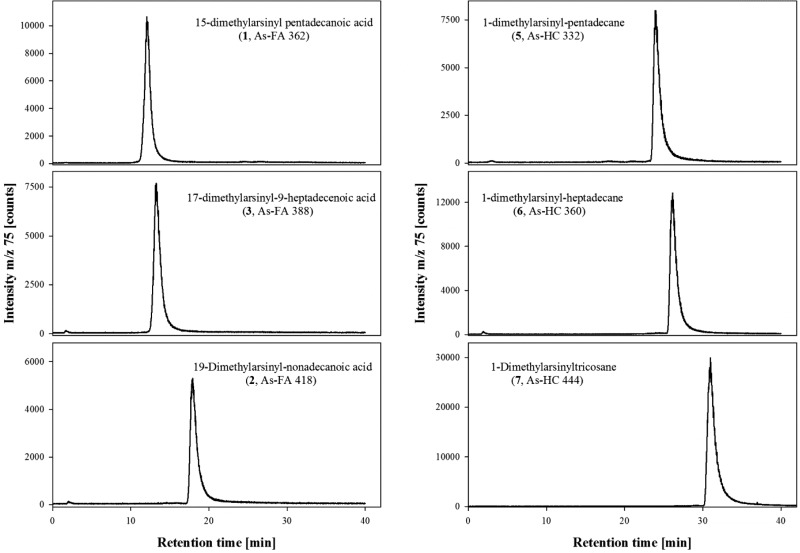

The general order of elution on reversed-phase HPLC of the three groups of arsenolipids is arsenic-containing fatty acids, arsenic-containing hydrocarbons, and arsenosugar phospholipids.14 Within each of these three groups, the compounds show increasing retention time with increasing C chain length and decreasing retention time with increasing number of double bonds (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reversed-phase HPLC/ICPMS chromatogram of six arsenolipids. The retention times have been determined by the carbon chain length and the absence/presence of a COOH group and a double bond. HPLC conditions: Zorbax SB C8 (1.0 × 50 mm; 3.5 μm) with a mobile phase of 10 mM NH4OAc pH 6.0 and ethanol with gradient elution (0–25 min, 35–95% ethanol); flow rate 0.2 mL min–1. A small arsenic impurity eluting at the column void volume (retention time ca. 2 min) is dimethylarsinate (Me2As(O)O–), a degradation product of the arsenolipids.

High-resolution mass spectra of the synthesized compounds were recorded with external mass calibration of the mass spectrometer. The collision-induced fragmentation of the MH+ ions was recorded. Owing to the accuracy of the mass spectrometer, the compositions of fragments are easily determined; Table 1 summarizes fragmentation features, and spectra (MS and MSMS) are provided as Supporting Information.

Table 1. Summary of MSMS Resultsa.

| compd code (no.) | MH+ | fragment ion MH+ – H2O | fragment ion C2H8OAs+ 123 | C2H6As+ 105 | C2H4As+ 103 | C4H9+ 57 | C5H7/C5H9/C5H11 67/69/71 | C6H7/C6H9/C6H11/C6H13 79/81/83/85 | C7H7/C7H9/C7H11/C7H13 91/93/95/97 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-FA 362 (1) | 363.1870 | 54 | 100 | 46 | 2 | 13 | 18/62/12 | 7/29/54/6 | 3/15/25/35 |

| As-FA 418 (2) | 419.2496 | 52 | 65 | 100 | 8 | 23 | 13/57/20 | 9/21/49/11 | 1/10/25/34 |

| As-FA 388 (3) | 389.2023 | 63 | 57 | 100 | 9 | 3 | 46/78/6 | 14/84/48/6 | 9/18/68/19 |

| As-FA 374 (4) | 375.1872 | 60 | 62 | 100 | 9 | 3 | 52/95/7 | 19/94/44/7 | 11/21/82/20 |

| C5H11+ 71 | C6H13+ 85 | C7H13+ 97 | |||||||

| As-HC 332 (5) | 333.2128 | <1 | 58 | 100 | 7 | 44 | 33 | 16 | 1 |

| As-HC 360 (6) | 361.2440 | <1 | 59 | 100 | 7 | 41 | 34 | 16 | 1 |

| As-HC 444 (7) | 445.3384 | <1 | 100 | 99 | 7 | 44 | 41 | 22 | 5 |

The intensities of MH+ – H2O ions are given in percentages of MH+. Intensities of other fragments are percentages of the base peak.

The fragmentation patterns were similar for all compounds, although the carboxylic acids showed additional peaks because they readily lose water and the resulting acylium ion gives rise to a richer family of carbocation fragments. Additionally, a small difference between the saturated and monounsaturated acid compounds can be seen as a general shift to a higher degree of unsaturation for carbocation fragment ions.

Concluding Comments

The synthesis of seven arsenolipids reported here provides material for an evaluation of the bioavailability and toxicity of a novel group of arsenic-containing natural products that accumulate in fatty fish and algae.

Experimental Section

The 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or MeOH-d4 with a Bruker (360 MHz) instrument. ICPMS (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry) measurements were recorded on an Agilent 7500 ce instrument, and chromatographic separations were performed with an Agilent HPLC 1100 system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn). Mass spectra were recorded on a Q-Exactive hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Acetonitrile solutions, approximately 10 μM in arsenolipid, were used for direct infusion at a flow rate of 10 μL/min. Spectra were recorded in the positive mode using the instrument’s HESI-2 source, a spray potential of 3.2 kV, a capillary temperature of 250 °C, and a sheath gas setting of 3 instrument units. The resolution was set to 140000, and full scans were obtained from m/z 50 to 400/500/750. MS/MS spectra were recorded with a parent ion isolation width of 0.4 Da. The collision energy (HCD) was adjusted to achieve the parent ion and largest fragment ion of similar intensity. For the reported MSMS results the HCD was 40 instrument units.

1-(Dimethylarsinyl)pentadecane (5, As-HC 332)

1-Pentadecyl tosylate was synthesized by the method described by Kazemi et al.29 Thus, KOH (2.7 g, 48 mmol), K2CO3 (5.0 g, 36 mmol), and 1-pentadecanol (2.28 g, 10.0 mmol) were combined and mixed in a mortar. Tosyl chloride (2.69 g, 14.1 mmol) was then added, and the mixture was mixed thoroughly with the pestle for 10 min. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature before excess tosyl chloride was destroyed by addition of tert-butyl alcohol (2 mL). The product was extracted from the resulting white powder with diethyl ether (3 × 25 mL); the ether layer was filtered and concentrated in vacuo, giving the product as a white crystalline solid. Yield: 3.24 g (8.47 mmol, 85%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.88 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.15–1.37 (m, 24 H, 12-CH2), 1.63 (quin, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.45 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.02 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 7.34 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, m-H), 7.79 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, o-H). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.1, 21.6, 22.7, 25.3, 28.8, 28.9, 29.4, 29.4, 29.5, 29.6, 29.7 (2C), 29.7, 29.7, 31.9, 70.7, 127.9 (2C), 129.8 (2C), 133.3, 144.6.

With a syringe, a solution of sodium dimethylarsenide (4.9 g, 21 mmol), prepared from iododimethylarsine according to the method of Feltham et al.,27 was transferred under argon to a two-necked round-bottom flask cooled to 0 °C and fitted with a reflux condenser and a dropping funnel. 1-Pentadecyl tosylate (1.6 g, 4.2 mmol) was dissolved in dry THF (20 mL) in the dropping funnel under argon, and this solution was added to the dimethylarsenide solution over 30 min. The solution was stirred overnight at room temperature and then refluxed for 6 h and cooled to room temperature. The reaction mixture was poured, under argon, into a separating funnel containing a mixture of water (25 mL) and ethyl acetate (25 mL), previously degassed with argon. The aqueous phase was removed and discarded, and the organic layer was washed with degassed water (2 × 25 mL). Hydrogen peroxide (30% H2O2, 4 × 2 mL) was added over 1 h and the mixture stirred for a further 2 h to convert the arsine to the oxide. The product was extracted from the reaction mixture with 0.1 M HCl (5 × 20 mL). The acidic aqueous phase was then adjusted to pH ∼9 with 1 M NaOH, and dimethylarsinyl pentadecane was extracted back into ethyl acetate (5 × 20 mL). Removal of ethyl acetate in vacuo yielded the crude product as a waxy solid. The crude product was dissolved in methanol (5 mL) and loaded onto a column (2.5 × 15 cm) of cation-exchange polymer (DOWEX 50W-X8-200, Sigma Aldrich, in the H+ form). Impurities were eluted with methanol (150 mL) before the product was eluted with saturated NH3(aq)/methanol (1/9 by volume). The eluent was concentrated in vacuo and the product recrystallized twice from acetone, giving needles of 1-(dimethylarsinyl)pentadecane (5, As-HC 332), which were dried in small portions on a piece of filter paper under a stream of argon. Yield: 212 mg (0.638 mmol, 15%). Melting point: 91–92 °C. 1H NMR (MeOH-d4, 300 MHz): δ 0.9 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, −CH3), 1.2–1.5 (m, 24H, 12-CH2), 1.6 (m, 2H, −CH2), 1.7 (s, 6H, −As(CH3)2), 2.1 (m, 2H, −AsCH2). 13C{1H} NMR (MeOH-d4, 75 MHz): δ 12.2, 13.0, 21.7, 22.3, 28.7, 29.1, 29.3, 29.4, 31.6. ESI-HRMS: m/z [M + H]+ calculated for M = C17H37AsO 333.2139, found 333.2126 (Δm = −3.9 ppm).

The arsenolipids 1–4, 6, and 7 (Figure 1) were prepared by the following general procedure using bis(dimethylarsenic) oxide. Thus, iododimethylarsine (3.0 mmol) was added dropwise to a stirred and cooled (2 °C) solution of sodium hydroxide (0.3 mL of 10 M, 3.0 mmol) under argon. After the mixture was stirred for 10 min, the bis(dimethylarsenic) oxide (top layer) was separated from the aqueous layer and covered with 10 M NaOH (0.3 mL, 3.0 mmol). A suspension of a bromo compound (0.5 mmol) in ethanol (0.5 mL) was then added, and the heterogeneous mixture was stirred and heated (80 °C) overnight. The solution was cooled, diluted with water, and washed with ether. The aqueous layer was then neutralized (for arsenic-containing hydrocarbons) or acidified to pH 3.5 (for arsenic-containing fatty acids) with 6 M HCl. The product was then extracted from the aqueous layer with chloroform, and the organic layer was washed with water and evaporated in vacuo. The residue was crystallized from ethyl acetate to give the arsenolipids as white solids.

1-(Dimethylarsinyl)heptadecane (6, As-HC 360)

The compound was prepared by reacting 1-bromoheptadecane with bis(dimethylarsine) oxide in the usual way to yield the product as a white solid (120 mg, 0.33 mmol, 63% yield). Melting point: 109–112 °C. Anal. Calcd for C19H41AsO: C, 63.31; H, 11.46, Found: C, 62.90; H, 11.26. 1H NMR (MeOH-d4, 300 MHz): δ 0.91 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, −CH3), 1.2–1.5 (m, 28H, 14-CH2), 1.6 (m, 2H, −CH2), 1.7 (s, 6H, −As(CH3)2), 2.1 (m, 2H, −AsCH2). 13C{1H} NMR (MeOH-d4, 75 MHz): δ 12.2, 13.0, 21.7, 22.3, 28.7, 29.0, 29.1, 29.3, 30.3, 30.5, 31.6. ESI-HRMS: m/z [M + H]+ calculated for M = C19H41AsO 361.2452, found 361.2440 (Δm = −3.3 ppm).

1-(Dimethylarsinyl)tricosane (7, As-HC 444)

Triphenylphosphine (190 mg, 0.72 mmol) was added to a suspension of tricosanol (190 mg, 0.56 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (10 mL) followed by N-bromosuccinamide (140 mg, 0.79 mmol) at 0 °C. The resulting solution was stirred under argon at room temperature until TLC analysis showed no remaining starting material. The reaction mixture was quenched with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layer was washed with Na2S2O3 (10% v/v) and then saturated brine, dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and evaporated. The resulting brown solid was suspended in n-pentane and filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated to give 1-bromotricosane (180 mg, 80%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 0.89 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, −CH3), 1.2–1.5 (m, 40H, 20-CH2), 1.87 (m, 2H, −CH2–CH2Br), 3.42 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, CH2Br). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 14.1, 22.7, 28.1, 28.7, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5, 29.6, 29.7, 31.9, 32.8, 34.0.

The bromotricosane was reacted with bis(dimethylarsine) oxide in the usual way to give 1- dimethylarsinyltricosane (7, As-HC 444) in 37% yield (29 mg, 0.065 mmol). 1H NMR (MeOH-d4, 300 MHz): 0.89 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, −CH3), 1.2–1.6 (m, 40H, 20-CH2), 1.6 (m, 2H, −CH2), 1.7 (s, 6H, -As(CH3)2), 2.1 (m, 2H, -As-CH2). ESI-HRMS: m/z [M + H]+ calculated for C25H53AsO: 445.3391, found 445.3383 (Δm −1.8).

15-(Dimethylarsinyl)pentadecanoic Acid (1, As-FA 362)

Bromopentanoic acid was reacted with bis(dimethylarsine) oxide in the usual way to give 15- (dimethylarsinyl)pentadecanoic acid in 88% yield (167 mg, 0.46 mmol). Melting point: 138–140 °C. 1H NMR (MeOH-d4, 300 MHz): 1.2–1.5 (m, 20H, 10-CH2), 1.6 (m, 4H, 2-CH2), 1.7 (s, 6H, _–As(CH3)2), 2.1 (m, 2H, −AsCH2), 2.3 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOH). 13C{1H} NMR (MeOH-d4, 75 MHz): δ 12.1, 21.6, 24.7, 28.7, 29.0, 29.1, 29.2, 30.2, 30.3, 176.6. ESI-HRMS: m/z [M + H] + calculated for M = C17H35AsO3 363.1880, found 363.1870 (Δm = −2.8 ppm).

19-(Dimethylarsinyl)nonadecanoic Acid (2, As-FA 418)

Bromononadecanoic acid was reacted with bis(dimethylarsine) oxide in the usual way to give 19-(dimethylarsinyl)nonadecanoic acid in 51% yield (62 mg, 0.15 mmol). Melting point: 125–127 °C. 1H NMR (MeOH-d4, 300 MHz): δ 1.3–1.5 (m, 28H, 14-CH2), 1.6 (m, 2H, −CH2), 1.7 (m, 2H, −CH2), 1.75 (s, 6H, −As(CH3)2), 2.20 (m, 2H, −AsCH2), 2.28 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOH). 13C{1H} NMR (MeOH-d4, 75 MHz): δ 12.0, 21.6, 24.7, 28.7, 28.8, 29.0, 29.1, 29.2, 30.2, 30.4, 33.6, 176.4. ESI-HRMS: m/z [M + H] + calculated for M = C21H43AsO3 419.2506, found 419.2498 (Δm = −1.9).

16-(Dimethylarsinyl)-9-hexadecenoic Acid (4, As-FA 374; Non-natural Product) (Scheme 2)

After the method of Hunsdiecker,30 9,10,16-trihydroxypalmitic acid (3 g, 9.9 mmol) was stirred and heated (90 °C) for 6 h with HBr (45 g of 14.5% hydrogen bromide solution in acetic acid). The acetic acid was distilled off, and the dark residue was taken up in ether and decolorized with activated carbon. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give a crude yellow solid of 9,10,16-tribromohexadecanoic acid (3.7g, 76%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 1.24–1.51 (m, 12H, 6-CH2), 1.63–1.65 (m, 4H, 2-CH2), 1.74–1.90 (m, 4H, 2-CH2), 2.07–2.12 (m, 2H, −CH2), 2.37 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOH), 3.43 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2Br), 4.03–4.19 (m, 2H, −BrCHCHBr−). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 24.6, 26.7, 26.8, 28.0, 28.5, 28.6, 28.9, 29.0, 32.6, 33.8, 36.7, 36.9, 59.7, 179.5. A solution of crude 9,10,16-tribromohexadecanoic acid in MeOH (55 mL) containing concentrated sulfuric acid (0.2 g) was refluxed for 7 h. The solution was concentrated in vacuo, the residue was taken up in ether, and the ether layer was washed with water and brine and then dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated to give the methyl ester. Yield: 3.3 g (87%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 1.24–1.48 (m, 12H, 6-CH2), 1.50–1.65 (m, 4H, 2-CH2), 1.77–1.97 (m, 4H, 2-CH2), 2.07–2.12 (m, 2H, −CH2), 2.31 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOCH3), 3.40 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2–Br), 3.67 (s, 3H, −COOCH3), 4.00–4.19 (m, 2H, −BrCHCHBr−). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 24.8, 26.7, 26.8, 27.5, 28.0, 28.5, 28.6, 28.9, 29.0, 32.6, 33.8, 34.0, 36.7, 36.9, 51.5, 59.7, 174.2. Following published methods,31,32 a suspension of zinc dust (1.7 g) in methanol (30 mL) and 0.1 mL of 14.5% hydrogen bromide solution in acetic acid was stirred under reflux for 25 min and then cooled to ca. 50 °C. A solution of crude 9,10,16-tribromohexadecanoic acid methyl ester (2.5 g, 4.9 mmol) in methanol (15 mL) was added dropwise over 30 min, and the mixture was refluxed for 1 h. The hot solution was filtered to remove zinc dust, and the solvent was evaporated from the filtrate in vacuo. The residue, in ether, was washed with water until the water wash was neutral; the ether was then evaporated in vacuo and the residue was purified with column chromatography (silica gel, 5% ethyl acetate in hexane) to give 16-bromo-9-hexadecenoic acid methyl ester as a colorless oil. Yield: 1.5 g (86%); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 1.26–1.45 (m, 14H, 7-CH2), 1.59–1.64 (m, 2H, −CH2), 1.80–1.88 (m, 2H, −CH2), 1.97 (m, 4H, −CH2CH=CHCH2−), 2.30 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOCH3), 3.40 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2Br), 3.67 (s, 3H, −COOCH3), 5.37 (m, 2H, −CH=CH−). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 24.9, 27.3, 27.8, 28.2, 28.6, 28.8, 29.0, 29.1, 29.6, 32.4, 34.0, 34.1, 51.4, 130.3, 174.3. 16-Bromo-9-hexadecenoic acid methyl ester was reacted with bis(dimethylarsine) oxide in the usual way to give 16-(dimethylarsinyl)-9-hexadecenoic acid (4, As-FA 374) in 57% yield (171 mg, 0.46 mmol). Melting point: 104–105 °C. 1H NMR (MeOH-d4, 300 MHz): 1.30–1.50 (m, 14H, 7-CH2), 1.6 (m, 4H, 2-CH2), 1.7 (s, 6H, −As(CH3)2), 2.0 (m, 4H, −CH2CH=CHCH2−), 2.1 (m, 2H, −AsCH2), 2.3 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOH), 5.41 (m, 2H, −CH=CH−). 13C{1H} NMR (MeOH-d4, 75 MHz): δ 12.1, 21.6, 24.7, 28.1, 28.5, 28.8, 29.0, 29.2, 30.3, 32.1, 33.8, 129.9, 130.2, 176.6. ESI-HRMS: m/z [M +H]+ calculated for M = C18H35AsO3 375.1880, found 375.1872 (Δm = −2.1 ppm).

17-(Dimethylarsinyl)-9-heptadecenoic Acid (3, As-FA 388) (Scheme 3)

After the method of Malkara and Kumara,33 a solution of (±)-threo-9,10,16-trihydroxyhexadecanoic acid (aleuritic acid; 15 g, 49 mmol) in MeOH (120 mL) containing concentrated sulfuric acid (0.3 g) was refluxed for 10 h. The solution was concentrated in vacuo, the residue was taken up in ether, and the ether layer washed with water and brine and then dried and concentrated to give the methyl ester. Yield: 13 g (83%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 1.3–1.6 (m, 22H, −CH2), 2.3 (t, J= 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOCH3), 3.4 (bs, 2H, −CH(OH)CH(OH)−), 3.6 (t, 2H, −CH2OH), 3.7 (s, 3H, −COOCH3), 9.7 (s, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 24.8, 25.5, 25.6, 29.1, 29.3, 29.4, 32.4, 33.4, 34.0, 51.5, 62.8, 74.4, 174.4. After the method of Ames,34 to a cooled (0 °C) and stirred solution of the methyl ester (10 g, 31 mmol) in a mixture of CH3CN and H2O (3/2, 130 mL) was added NaIO4 (8.5 g, 40 mmol) in portions. The mixture was stirred for 35 min and then filtered to remove NaIO3. The filtrate was then extracted with CHCl3, and the extract was washed with water and brine and then dried. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified with column chromatography (silica gel, 15% ethyl acetate in hexane) to give 9-oxononanoic acid methyl ester as a colorless oil. Yield: 4.9 g (84%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 1.3 (m, 6H, 3-CH2), 1.6 (m, 4H, 2-CH2), 2.3 (t, J= 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOCH3), 2.4 (dt, J = 7.3, 1.9 Hz, 2H, CH2CHO), 3.6 (s, 3H, −COOCH3), 9.7 (s, 1H, −CHO). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 22.1, 24.7, 28.9, 29.0, 33.4, 43.9, 51.5, 174.3, 202.9.

Following the method of Hill,35 a mixture of 1,8-dibromooctane (15 g, 55 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (2.9 g, 11 mmol) was heated in an oil bath at 90 °C for 6 h. The flask was then cooled, and the excess 1,8-dibromooctane was decanted off, leaving the monophosphonium salt as a sticky solid, which was washed with dry toluene (2 × 40 mL). The residue was dissolved in chloroform (15 mL) and the mixture added to dry diethyl ether (100 mL) to precipitate the product, which was washed with more diethyl ether and dried in vacuo to give 8-(bromooctyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide as a white solid (5.3 g, 90%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 1.2–1.8 (m, 12H, 6-CH2), 3.3 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, −CH2Br), 3.7 (m, 2H, −CH2P+Ph3Br–), 7.6–7.9 (m, 15H, 3-C6H5). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 22.4, 22,5, 23.0, 27.9, 28.9, 30.1, 32.6, 34.1, 117.7, 118.8, 130.4, 130.6, 133.5, 113.7, 135.0. After the method of Shi,36 a mixture of phosphonium bromide (2 g, 3.7 mmol), 9-oxononanoic acid methyl ester (0.6 g, 3.2 mmol), anhydrous potasium carbonate (1.7 g, 12.3 mmol), and tetrahydrofuran (20 mL) was stirred at reflux under argon for 24 h and then filtered. The filtrate was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, 5% ethyl acetate in hexane) to give 17-bromo-9-heptadecenoic acid methyl ester as a colorless oil. Yield: 0.38 g (33%); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 1.3–1.46 (m, 16H, 8-CH2), 1.61–1.65 (m, 2H, −CH2), 1.80–1.90 (m, 2H, −CH2), 2.0 (m, 4H, −CH2CH=CHCH2−), 2.3 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOH), 3.42 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2Br), 3.67 (s, 3H, −COOCH3), 5.35 (m, 2H, −CH=CH−). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 24.9, 27.1, 28.1, 28.6, 29.0, 29.1, 29.2, 29.6, 32.8, 34.0, 34.1, 51.4, 129.7, 174.3. Reaction of the methyl ester with bis(dimethylarsine) oxide in the usual way gave 17-(dimethylarsinyl)-9-heptadecenoic acid (3, As-FA 388) as a white solid: 92 mg (0.24 mmol, 46%). Melting point: 89–91 °C. 1H NMR (MeOH-d4, 300 MHz): 1.3–1.5 (m, 16H, 8-CH2), 1.6 (m, 4H, 2-CH2), 1.7 (s, 6H, −As(CH3)2), 2.0 (m, 4H, −CH2CH=CHCH2−), 2.1 (m, 2H, −AsCH2), 2.3 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, −CH2COOH), 5.4 (m, 2H, −CH=CH−). 13C{1H} NMR (MeOH-d4, 75 MHz): δ 12.1, 21.7, 24.7, 26.6, 28.1, 28.5, 28.6, 28.7, 28.8, 29.2, 29.3, 30.2, 32.1, 33.8, 129.4, 130.1, 176.6. ESI-HRMS: m/z [M + H]+ calculated for M = C19H37AsO3 389.2037, found 389.2027 (Δm = −2.57 ppm).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), project number I550-N17, the DFG grant number SCHW903/4-1, and the Carlsbergfoundation. We thank NAWI Graz and the Styrian Government for supporting the Graz Central Lab-Metabolomics.

Supporting Information Available

Figures giving NMR and high-resolution mass spectra for the seven arsenolipids. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lunde G. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1968, 45, 331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney R. V.; Mumma R. O.; Benson A. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1978, 75, 4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson A. A.; Summons R. E. Science 1981, 211, 482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summons R. E.; Woolias M.; Wild S. B. Phosphorus Sulfur Relat. Elem. 1982, 13, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds J. S.; Francesconi K. A. Experientia 1987, 43, 553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M.; Shibata Y. Chemosphere 1988, 17, 1147. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds J. S.; Francesconi K. A. Nature 1981, 289, 602. [Google Scholar]

- Rumpler A.; Edmonds J. S.; Katsu M.; Jensen K. B.; Goessler W.; Raber G.; Gunnlaugsdottir H.; Francesconi K. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taleshi M. S.; Jensen K. B.; Raber G.; Edmonds J. S.; Gunnlaugsdottir H.; Francesconi K. A. Chem. Commun. 2008, 39, 4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Abad U.; Mattusch J.; Mothes S.; Moeder M.; Wennrich R.; Elizalde- Gonzalez M. P.; Matysik F. M. Talanta 2010, 82, 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taleshi M. S.; Edmonds J. S.; Goessler W.; Ruiz-Chancho M. J.; Raber G.; Jenson K. B.; Francesconi K. A. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amayo K. O.; Petursdottir A.; Newcombe C.; Gunnlaugsdottir H.; Raab A.; Krupp E. M.; Feldmann J. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sele V.; Sloth J. J.; Lundebye A. K.; Larsen E. H.; Berntssen M. H. G.; Amlund H. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 618. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Salgado S.; Raber G.; Raml R.; Magnes C.; Francesconi K. A. Environ. Chem. 2012, 9, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Lischka S.; Arroyo-Abad U.; Mattusch J.; Kuehn A.; Piechotta C. Talanta 2013, 110, 144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab A.; Newcombe C.; Pitton D.; Ebel R.; Feldmann J. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Abad U.; Lischka S.; Piechotta Ch.; Mattusch J.; Reemtsma T. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amayo K. O.; Raab A.; Krupp E. M.; Gunnlaugsdottir H.; Feldmann J. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 9321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Abad U.; Lischka S.; Piechotta C.; Mattusch J.; Reemtsma T. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amayo K. O.; Raab A.; Krupp E. M.; Feldmann J. Talanta 2014, 118, 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini I.; Guella G.; Frostin M.; Hnawia E.; Laurent D.; Debitus C.; Pietra F. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 8989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D.; Coote M.; Ho J.; Kilah N.; Lin C.-H.; Salem G.; Weir M. L.; Willis A. C.; Wild S. B. Organometallics 2012, 31, 1808. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeisser E.; Rumpler A.; Kollroser M.; Rechberger G.; Goessler W.; Francesconi K. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeisser E.; Goessler W.; Francesconi K. A. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 385, 367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds J. S.; Francesconi K. A.; Stick R. V. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1993, 10, 421. [Google Scholar]

- Traar P.; Rumpler A.; Madl T.; Saischek G.; Francesconi K. A. Aust. J. Chem. 2009, 62, 538. [Google Scholar]

- Feltham R. D.; Kasenally A. S.; Nyholm R. S. J. Organomet. Chem. 1967, 7, 285. [Google Scholar]

- McAdam D. P.; Perera A. M. A.; Stick R. V. Aust. J. Chem. 1987, 40, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi F.; Massah A. R.; Javaherian M. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 5083. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsdiecker H. Ber. Bunsen-Ges. Phys. Chem. 1943, 76B, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Blomquist A. T.; Holley R. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur H. H.; Bhattacharyya S. C. J. Chem. Soc. 1963, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Malkara N. B.; Kumara V. G. Synth. Commun. 1998, 28, 977. [Google Scholar]

- Ames D. E.; Goodburn T. G.; Jevans A. W.; McGhee J. F. J. Chem. Soc. 1968, 268. [Google Scholar]

- Hill W. E.; Islam M. Q.; Webb T. R. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1988, 146, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Shi D. Q.; Chen R. Y. Chin. Chem. Lett. 1999, 10, 911. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.