Abstract

Emerging and legacy environmental pollutants such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organochlorine pesticides (DDE) are found in human placenta, indicating prenatal exposure, but data from the United States are sparse. We sought to determine concentrations of these compounds in human placentae as part of a formative research project conducted by the National Children’s Study Placenta Consortium. A total of 169 tissue specimens were collected at different time points post delivery from 42 human placentae at three U.S. locations, and analyzed by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry following extraction using matrix solid phase dispersion. PBDEs, PCBs, and DDE were detected in all specimens. The concentrations of 10 PBDEs (∑10PBDEs), 32 PCBs (∑32PCBs) and p,p’-DDE were 43–1,723, 76–856 and 10–1,968 pg/g wet weight, respectively, in specimens collected shortly after delivery. Significant geographic differences in PBDEs were observed, with higher concentrations in placentae collected in Davis, CA than in those from Rochester, NY or Milwaukee, WI. We combined these with other published data and noted first-order declining trends for placental PCB and DDE concentrations over the past decades, with half-lives of about 5 and 8 years, respectively. The effect of time to tissue collection from refrigerated placentae on measured concentrations of these three classes of persistent organic pollutants was additionally examined, with no significant effect observed up to 120 hours. The results of this work indicate that widespread prenatal exposure to persistent organic pollutants in the United States continues.

Keywords: Persistent organic pollutants, human placenta, polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), National Children’s Study (NCS)

1. Introduction

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dichlorodiphenyl-dichloroethylene (DDE) are chemicals that are persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic. They have been widely used commercially – PBDEs as flame retardants, and PCBs mainly as dielectric or coolant fluids in electrical components. DDE is a breakdown product of the agricultural pesticide DDT. While their manufacture or use has been banned or restricted in the United States, these chemicals are detected in gravid human blood, newborn umbilical cord blood, and breast milk, indicating that prenatal and neonatal exposures to these chemicals are occurring (Al-Saleh et al., 2012; Frederiksen et al., 2009b; Shen et al., 2007; Hites, 2004; Schecter et al., 2003; Curley 1969; Rappolt and Hale 1968). Human and animal studies suggest that exposure to these chemicals in utero may have fetal developmental effects with potential life-long consequences (Jusko et al., 2012; Herbstman et al., 2010; Howdeshell, 2002; ATSDR, 2002; Darnerud et al., 2001; Aoki, 2001).

The placenta serves as a lifeline for the embryo and fetus, facilitating nutrient and gas exchange between mother and the fetus, and waste removal from the fetal environment. For bioaccumulative and toxic chemicals, the placenta may act as a diffusive barrier (Iyengar and Rapp, 2001) or a repository (Miller et al., 2007; Slikker and Miller, 1994). That placental transfer of PCBs occurs has been known for some time (Wang et al., 2006). Other toxic chemicals found in placentae include pesticides, drugs, and metals (Iyengar and Rapp, 2001; Myren et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2007; Eisenman and Miller, 1996; Zadorozhnaja et al., 2000). More recent studies have provided evidence for placental passage of PBDEs (Frederiksen et al., 2010; Gómara et al., 2007).

The National Children’s Study (NCS) is a planned longitudinal study of 100,000 children in the United States, currently piloted in a number of U.S. locations. NCS will follow children from before birth to 21 years, to examine the influence of the environment on child health and development, in order to enhance understanding of the influence of environmental and other factors, both risk and protective, on health and development (Congress, 2000). Formative research is conducted as part of the NCS to address questions intended to inform the main study. We conducted a formative research project (LOI2-BIO-18) designed to establish for the NCS protocols for collection, management, utilization, examination, and storage of placental specimens for stem cell studies, morphologic/pathologic examination, genetic assessments, and analysis of environmental pollutants.

As part of the LOI2-BIO-18 project, we analyzed the concentrations of 43 organic compounds, including 10 PBDEs, 32 PCBs, and p,p’-DDE, in 169 placental tissue samples from 42 placentae collected in three geographic regions of the United States. Results were compared among the three sampling locations and with those reported from other countries, examined for congener distribution patterns, and combined with other published data to investigate temporal trends in contamination by these chemicals over the past decades. This work was also designed to determine how time elapsed from delivery to tissue collection influences chemical analysis. For this purpose, multiple placental parenchymal tissue samples were collected from each placenta at different time intervals after placental delivery, and the data were analyzed to investigate variation in analyte concentration with time in refrigerated storage of the placenta prior to tissue collection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

Placenta samples were collected from hospitals in upstate New York, the Milwaukee area of Wisconsin, and Sacramento County in California, by NCS study centers and subcontractors located at the University of Rochester (UR), Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW), and University of California-Davis (UCD), respectively. Written informed consent was obtained as required by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of record for the collecting institution. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by an Office of Human Research Protections registered IRB.

Placentae were sought from pregnant women with no history of maternal or fetal abnormalities and no labor complications. All specimens were collected from grossly normal areas of the villous parenchyma, with exclusion of the decidua basalis and chorionic plate. Each collection was restricted to a placental region. Collections were made into acid-washed 50-mL tubes using plastic (non-metallic) disposable forceps.

Repeated collection of specimens from each placenta occurred as per the sampling plan given in Table S1 of the Supplemental Material. Initial tissue specimen collection from placentae occurred within 15-30 minutes after birth (referred to as “t = 0” hereafter). All placentae were sampled at t = 0. The frequency of subsequent sampling at designated time points varied among sites (Table S1). A total of 169 specimens were collected from 42 placentae. During the repeated sampling procedure, placentae were kept at 4°C. Collected specimens were coded, frozen at −20°C, and transferred on dry ice to the NCS Placenta Processing Center in Rochester NY, where they were re-coded and express-delivered on dry ice to the Environmental Organic Chemistry Laboratory at the School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). The analysis laboratory was blinded to information associated with the coded specimens. The wet weights of individual samples ranged from 2.4 g to 42 g. Upon receipt, specimens were held at −20°C until processing.

2.2. Chemical Analysis

Detailed procedures including the extraction, cleanup, and instrumental analyses are described in the Supplemental Material. Briefly, freeze-dried tissues were extracted using matrix solid phase dispersion (MSPD), which was previously optimized for analyzing PBDEs in human placental tissue (Dassanayake et al., 2009). Cleanup of the extract was performed using multilayer silica gel column chromatography.

Individual compounds analyzed included BDEs 28, 47, 66, 85, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183, and 209, PCBs 8, 28, 37, 44, 49, 52, 60, 66, 70, 74, 77, 82, 87, 99, 101, 105, 114, 118, 126, 128, 138, 153, 156, 158, 166, 169, 170, 179, 180, 183, 187, and 189, and DDE. PCBs and DDE were analyzed with a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890 GC) using a 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.1 μm thickness column (Restek Rxi-XLB), coupled with a tandem mass spectrometer (Agilent 7000 MS/MS) equipped with an electron impact ionization source. PBDEs were analyzed with a gas chromatograph coupled with a single quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent 6890 GC / 5973 MS). A 15 m capillary column with a 0.25 mm ID and 0.10 μm thickness (Restek Rtx-1614) was used for the separation. The MS was operated in the electron capture negative ionization (ENCI) mode with methane as the reagent gas.

A quality control protocol was implemented. No target chemicals were found in the tissue collection tubes using deionized water as matrix. One procedural blank was analyzed with each batch of 10-15 samples. 13C-labeled PCB52 (as PCB surrogate) and two fluorinated PBDEs (FBDEs 47 and 208, as surrogates for PBDEs) were spiked into each sample before extraction. Their recoveries were 67±18% (N=125), 105±21% (N=170), and 96±24% (N=124), respectively. Limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ) are listed in Table S2, calculated as the concentrations 3 and 10 times, respectively, of the instrument signal-to-noise ratio. Additional detailed quality control results are described in the Supplemental Material.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Mixed effect models were used to test the hypothesis that, at the population level, the logarithms of the ∑10PBDEs, ∑32PCBs and DDE concentrations did not change with time to tissue collection. Logarithm transformed concentrations were used to improve normality in the residuals. Mixed effects models were used rather than ANOVA because not all placentae were sampled at all time points. Mixed effects models were used rather than standard linear regression to account for repeated measures from each placenta. Specifically, placenta was treated as a random intercept effect to account for repeated measures from each placenta. The placenta random intercept was also nested within the study site variable to address the hierarchical study design. Models were implemented using the lme function with the maximum likelihood method in the R Project for Statistical Computing. The location hierarchical random effects were retained for location interclass correlation ≥ 1%. Models with random slope effects were compared to the random intercept models using the log-likelihood (logL) test, and were preferred when p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

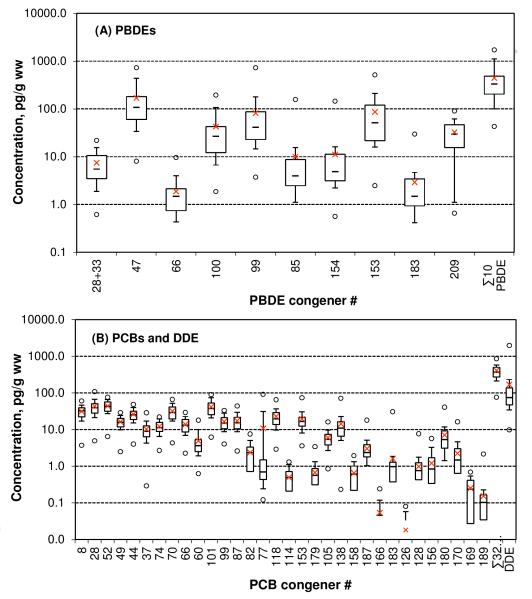

The measured concentrations of ∑10PBDEs, ∑32PCBs and p,p’-DDE are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1. Descriptive statistics for individual analytes are summarized in Table S3. All concentrations are reported on a wet weight (ww) basis. Due to the nature of the MSPD extraction method, simultaneous lipid content determination was impossible, and the small quantity of tissue available did not allow for a separate lipid measurement. The concentrations of all analytes showed near log-normal distributions.

Table 1.

Median and range of concentrations (pg/g ww) by sampling site.

| Analyte | Rochester NY | Davis CA | Waukesha WI | All Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specimens collected at time = 0 h | ||||

| n* | 17 | 13 | 12 | 42 |

| ∑10PBDEs | 266 (43–848) | 343 (172–1723) | 317 (76–1493) | 330 ( 43–1723) |

| ∑32PCBs | 395 (174–856) | 412 (76–848) | 344 (185–577) | 371 (76–856) |

| DDE | 56 (10–397) | 120 (51–1968) | 63 (33–1039) | 74 (10–1968) |

| All specimens collected | ||||

| N** | 76 | 52 | 41 | 169 |

| ∑10PBDEs | 266 (43–6083) | 431 (155–1779) | 191(31–1554) | 313 (31–6083) |

| ∑32PCBs | 409 (164–876) | 406 (76–1572) | 360 (134–902) | 395 (76–1572) |

| DDE | 69 (10–637) | 122 (12–3223) | 77 (14–1951) | 81 (10–3223) |

n = the number of placentae collected.

N = the number of specimens received by the analytical laboratory.

Figure 1.

Box and whisker plot of concentrations of (A) PBDEs and (B) PCBs and DDE in placentae collected at t = 0 (N = 42). Shown are average (cross), median (lines inside the box), 25th to 75th percentiles (box), 10th and 90th percentiles (whiskers), and the minimum and maximum (circles). Missing data points indicates the presence of non-detect results.

3.1. PBDEs

The median of ∑10PBDEs in 42 placental tissue samples from initial collection time (t = 0) is 330 pg/g ww, with a range of 43–1,723 pg/g ww. Compared to those in European countries and Japan, PBDE levels in human placentae in the United States are significantly higher (see Table S4-a). The median (291 pg/g ww) of tri- to hepta- BDEs (∑3-7BDEs) is about seven times that reported from a highly polluted e-waste recycling region in China (41 pg/g ww) (Zhao et al., 2013). Our finding aligns with reports that PBDE concentrations in various human samples from North America are generally one to two orders of magnitude higher than those in Europe and Asia (Hites, 2004; Sjödin et al., 2003).

The only previously published study in the United States of PBDEs in human placentae focused on analytical method development and involved only five placenta specimens collected in Chicago, IL during 2007 to 2008 (Dassanayake et al., 2009). While small sample numbers in that study make a direct comparison inconclusive, the range of the total concentration of the same ten congeners (367–2,317 pg/g wet wt) reported there (Dassanayake et al., 2009) nonetheless overlaps with the range observed from the present study. Compared to Dassanayake et al., (2009), the median of the total tri- to hepta-BDEs in this study is significantly lower, while the concentration of BDE209 is 56% higher. These differences may reflect the impact of phasing-out commercial penta mixture in 2004, and continued use of commercial deca product.

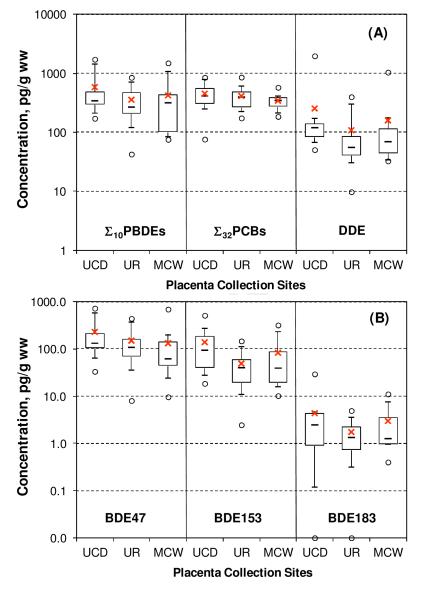

For ∑10PBDEs and almost all PBDE congeners, the median concentration values are higher in samples collected by UCD than those collected by UR or MCW (Table 1 and Figure 2-A). The median and mean concentrations of BDEs 47, 153 and 183 in UCD samples were approximately double those at the other two collection sites (Figure 2-B). Unpaired t-test using the natural log concentrations demonstrates that the differences between UCD and MCW are statistically significant for BDE47 (p = 0.039) and likewise between UCD and UR for BDE153 (p = 0.0069). For ∑10PBDEs, p-values for t-tests comparing UCD with UR and MCW were 0.062 and 0.094, respectively, while p = 0.46 for the difference between UR and MCW. The higher levels of PBDEs in human placentae from UCD are consistent with elevated PBDE concentrations in house dust and serum observed in northern and central California, and may reflect unique furniture flammability standards in California (Zota et al., 2011, 2008). Interestingly, the range between the 25th and the 75th percentiles of ∑10PBDEs at UCD is narrower than those at the other two locations (Figure 2-A), suggesting a lower variability in exposure to PBDEs among individuals living in northern California than in the areas of upstate New York or Milwaukee, Wisconsin. To our knowledge, this is the first report of geographic differences in placental PBDEs in the United States.

Figure 2.

Comparison of concentrations at time = 0 among placenta collection sites (N = 13 for UCD, N = 17 for UR, and N = 12 for MCW). Shown are average (cross), median (lines inside the box), 25th to 75th percentiles (box), 10th and 90th percentiles (whiskers), and the minimum and maximum (circles). In (B) two major components in the commercial product “penta” BDEs 47 and 153 and a representative congener of product “octa” BDE183 are selected.

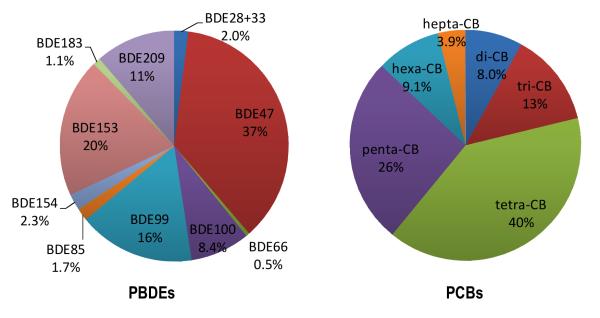

BDE47 is the most abundant PBDE congener, accounting for 37(±13)% of ∑10PBDEs (Figure 3-A). It is followed by BDEs 153, 99, 100, and 209 (Figure 3-A). The relative abundance of congeners varies around the world. In Europe, Japan and China, BDE209 is found to be the most abundant congener, accounting for more than 50% of the total concentrations in human placentae (Zhao et al., 2013; Frederiksen et al., 2009a; Gómara et al., 2007; Takasuga et al., 2006). In the United States, however, BDE47 is the most prevalent in human and other biota. The concentration of BDE47 in placentae is about one order of magnitude higher in the United States than in Europe, consistent with relatively high concentrations of BDE47 found in dust in the U.S. (Frederiksen et al., 2009b). Differences in congener distribution between the continents are not surprising, given the fact that Americans consumed 98% of pentaBDEs but only 44% of decaBDE on the global market (Hites, 2004). In addition, the lower BDE congeners, namely BDEs 28+33, 47, 66, 85, 99, 100, 153, and 154, all of which are components of commercial penta mixture (La Guardia et al., 2006), are significantly positively correlated (Table S5).

Figure 3.

PBDE congener and PCB homolog distributions (as % of Total) based on the averages of specimens collected at t = 0 (N = 42).

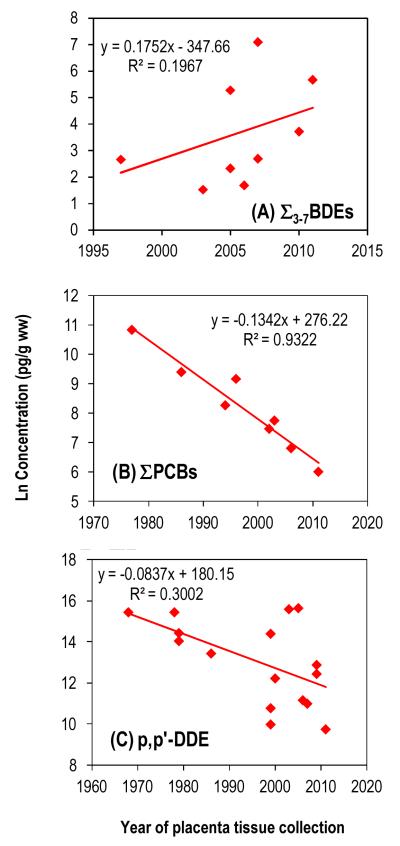

The limited number of observations over past decades makes time trend analysis difficult. Overall, the trend is one of increasing concentrations over time (Figure 4-A). In the year 2000, BDE47 levels in human serum of the U.S. population exceeded that of PCB153 (Sjödin et al., 2004). Among all the analytes we examined, BDE47 had the highest level. The median concentration ratios of BDE47 to PCB52, PCB153, and DDE were 2.2, 6.5 and 1.3, respectively.

Figure 4.

Temporal trends of concentrations in human placenta tissue. Data are from Table S4. The median concentrations were used for PBDEs and PCBs; while for DDE the mean was used due to the limited number of reported medians. For PCBs, studies from Asia and/or using only “dioxin-like” congeners are excluded. Regression statistics are given in Table S6.

3.2. PCBs

The median of ∑32PCBs in the 42 placenta tissue samples initially collected (t = 0) was 371 pg/g ww, ranging from 76 to 856 pg/g ww (Table 1). The set of PCBs analyzed in this study included 7 “indicator” congeners (PCBs 28, 52, 101, 118, 138, 153 and 180), which are often the most abundant congeners found in the environment and in humans. The set of targeted PCBs also contains 8 of the 12 “dioxin-like” congeners (PCBs 77, 105, 114, 118, 126, 156, 169 and 189).

Using an ANOVA single factor test on the means of log-transformed concentrations from the initial collection time, no significant differences between collection sites were found for the seven indicator PCBs and∑32PCBs, although both the mean and median for UCD are higher than those at the other sites (Figure 2-A). Additionally, no significant correlation was found between ∑32PCBs and ∑10PBDEs (p = 0.43). This was not unexpected based on the differences between PCBs and PBDEs with regard to their sources of human exposure and time scales of production and use.

The homolog distribution pattern of PCBs is shown in Figure 3. Among the 32 PCBs analyzed, PCB52 was found to have the highest median concentration, followed by two other indicator congeners, PCBs 28 and 101. PCB126 was detected least frequently and was present in only 48% of the samples. Gómara et al., (2012) also found PCB52 concentrations higher than others. A number of studies found PCB153 to be the most abundant congener in placenta (Bergonzi et al., 2009; Reichrtová et al., 1999). In the serum of pregnant and non-pregnant women in the U.S. in 2003-2004, PCB153 was higher than PCB52 (Woodruff et al., 2011). Most of the major congeners are strongly correlated with each other, except PCB180 (Table S5). These variations in PCB congener patterns in human samples warrant further study.

Table S4-b summarizes the PCB concentrations reported in the literature. Caution is needed in comparing the data, due to the different congeners included as well as possible variations in detection limits and data quality. Generally, PCB concentrations in human placenta appear to be higher in North America and Europe than in Asia. This spatial distribution pattern for PCBs in placental tissue may reflect the fact that about 80% of global PCB production occurred in the U.S. and European countries (Breivik et al., 2002).

Since its ban in the 1970s, the PCB burden in humans has been declining. Using the wet weight based concentration data in Table S4-b with exclusion of studies from Asia and/or using only dioxin-like PCBs, we modeled time trends based on first-order kinetics, i.e., ln C vs. year of placental collection (Figures 4-B). Despite the differences in the number of PCB congeners used and the geographical regions among individual studies, the regression statistics are remarkably strong (R2 = 0.93 and p = 0.0001; Table S6). The apparent half-life of the decline, estimated from the slope, is 5.2±0.6 years. Long-term declining trends in PCB concentrations have been reported in numerous studies, with apparent half-lives of, for example, about 7 years in air (Sun et al., 2006) and 3-6 years before 1990 then 15-30 years in fish (Carlson et al., 2010) of the Great Lakes. In humans, reported congener-specific apparent half-lives of PCBs range from 0.1 to >40 years (Ritter et al., 2011).

3.3. DDE

p,p’-DDE was detected in 100% of placenta samples, with mean concentration of 168 pg/g ww and median concentration of 74 pg/g ww for samples collected at t=0 (Table S3). The corresponding mean and median for samples from all collection time points were 205 pg/g ww and 81 pg/g ww, respectively, ranging from 10 ww to 3,223 pg/g ww (Table 1). Although large scale production of the pesticide DDT commenced and ended earlier than it did for PCBs and PBDEs, the DDT metabolite DDE is still more prevalent and abundant in human placenta than any individual PCB or PBDE congener except BDE47, based on the medians found in this work (Table S3).

DDE concentrations reported in the literature range from 58 pg/g lipid to 5×106 pg/g lipid (Table S4-c). The averages in Table S4-c indicate a declining trend over time (Figure 4-C) despite high variability in recent years. The overall DDE half-life, calculated from the slope of the regression based on first order kinetics using the mean concentrations summarized in Table S4-c, is about 8.3±3.4 years. If only data from the U.S. are used, the half-life is 5.5±0.5 years. The widespread use of DDT from the 1940s to the 1970s around the world, and the fact that DDE is highly persistent, make DDE a global pollutant. Despite differences in the scale of DDT application among countries, the overall declining trend on a global scale is clear and strong. Similar trends in air, soil, wildlife, and human DDE concentrations have been widely reported in many regions of the world, including the Arctic.

In this work, the highest DDE concentrations (>1,000 pg/g ww at t = 0) were found in two placentas collected by UCD and MCW, respectively. The two next highest (>300 pg/g ww at t = 0) were both from UR. The 90th percentile of all the samples was 270 pg/g ww. In contrast to PBDEs and PCBs, access to DDT stored in the individual home environment could dominate overall personal exposure in these cases. Nonetheless, placental tissues collected by UCD had comparatively higher DDE concentration than those from UR (p = 0.03), based on a one-tail t-test for t = 0 data, implying the existence of regional differences. The Spearman rank correlation of DDE with ∑32PCBs was strong (p = 0.003) but not with ∑10PBDEs (p = 0.46). The correlation between DDE and PCBs could be the result of similar time periods (1940s to 1970s) for human exposure. DDE does not share any sources or time scale with PBDEs.

3.4. Variation of measured concentrations with placenta storage time

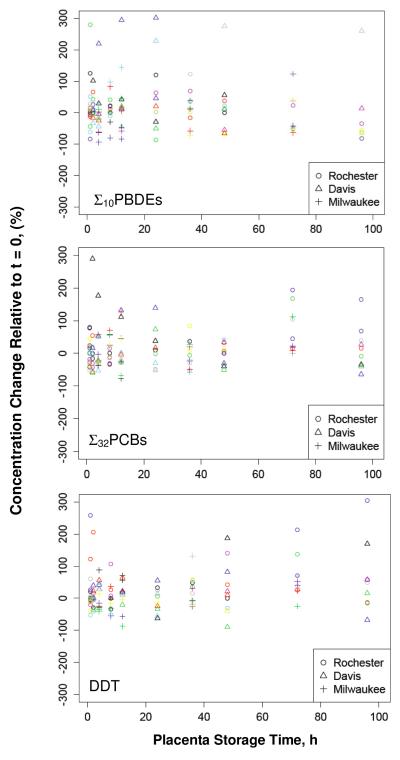

Variations of the concentrations of ∑10PBDEs, ∑32PCBs and DDE over increasing delays in placental tissue sampling were analyzed. The results demonstrated that, in general, the variation was within ±50% up to 48 h, and did not show significant difference among collection sites. Greater variations in concentration were observed in samples stored 72 h or longer (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Relative change of concentrations with placental storage time. Symbol shape indicates study location, and color indicates each unique placenta.

Final mixed effects models are presented in Table 2. The hierarchical random intercept effect was included for ln(∑10PBDE) only, indicating that the mean concentrations differed among the study locations. Of the unexplained variance in ln(∑10PBDE) concentrations, 4.6% was explained at the level of study site and 43% at the level of individual placentae, which means that the variability between study sites was smaller than the variability among placentae. Of the unexplained variance in ln(∑32PCBs) and ln(DDE) concentrations, 30% and 85% was explained at the level of individual placentae, respectively. This means that, for all three chemical classes studied, pollutant concentrations vary widely among placentae.

Table 2.

Mixed effects models of pollutant concentrations as a function of sample collection time with a random intercept effect of placenta or placenta nested within study location.

| ln(∑10PBDEs) | ln(∑32PCBs) | ln(DDE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE |

| intercept βo | 5.75 | 0.160 | 5.92 | 0.0557 | 4.46 | 0.150 |

| time slope β1 | 1.7×10−3 | 2.0×10−3 | 5.9×10−3 | 1.1×10−3 | 2.0×10−3 | 1.2×10−3 |

| location intercept variance σγ2 | 0.0372 | - | - | |||

| placenta intercept variance σ02 | 0.347 | 0.0623 | 0.860 | |||

| error variance σ2 | 0.426 | 0.148 | 0.152 | |||

| −2logL | 390.16 | 190.12 | 285.18 | |||

Our specific objective with these models was to test if the concentrations changed with increasing time to sample collection (0–120 h). The event of no change with sample collection time was indicated by a regression coefficient equal to zero, β1 = 0, and tested against a two-sided alternative hypothesis, β1 ≠ 0. The addition of a random slope effect was considered, but this model did not converge (e.g., ∑32PCBs and DDE), or provided no improvement relative to random intercept models (e.g., ∑10PBDE, log-likelihood test p-value = 0.09). For all pollutants, the change with time, β1, is slightly positive, but not statistically significantly different from zero (Table 2). This indicates that at the population level and for these data, the concentrations of ln(∑10PBDE), ln(∑32PCBs), ln(DDE) do not change significantly with delays of up to 120 h in tissue sample collection from refrigerated placentae.

This analysis suggests that, when placentae are refrigerated at 4°C under clean conditions, delays of <120 h in tissue collection may not significantly alter results of measurements of PBDEs, PCBs, and DDE in placental tissue. However, variation of pollutant concentrations with prolonged storage without proper preservation may occur due to contamination from air or collection containers, loss of blood, and other unknown factors. The observed variation of concentration over time may also be explained by tissue heterogeneity of the placenta. This effect would be eliminated by homogenization of the placenta prior to specimen collection. In this study, homogenizing the placenta was in conflict with the study design to simulate undisturbed placental tissue prior to tissue collection. To minimize potential changes in pollutant concentrations, tissue collection within 72 h of delivery is strongly recommended for analysis of trace level persistent organic chemicals.

In conclusion, the results of this work indicate that widespread and geographically varied prenatal exposure to persistent organic pollutants in the United States continues. Future study of the sources, influencing factors, and health consequences of such exposure is warranted. Investigation of temporal trends in concentrations of these chemicals in placental tissue suggests continued decline for PCBs and DDE but an increasing overall trend for PBDEs. Our findings indicate additionally that procedures developed for NCS collection, transport, processing, shipment, and storage of placental tissue preserve relative stability for measurement of PBDEs, PCBs, and DDE for at least 72 hours.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We measured 10 PBDEs, 32 PCBs, and DDE in 169 placenta specimens from 42 placentae.

Significant geographic differences in placental PBDEs in the U.S. were found.

Worldwide first-order declining trends for PCBs and DDE were identified.

The concentrations did not vary much for specimens collected <72 h after delivery.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank our fellow researchers of the LOI2-BIO-18 team as well as all the women who donated their placentae. We acknowledge the administrative support from the NCS Greater Chicago Study Center at the Northwestern University. The Consortium acknowledges the contributions of Amber Rinkerknecht, Linda Salamone, and Philip Weidenborner on behalf of this research and offers special acknowledgements to Tai Kwong and Alan Friedman for their review of the data and editorial comments.

Funding Source This work is part of the National Children’s Study Placenta Consortium (NCS formative research project LOI2-BIO-18). This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and funded, through its appropriation, by the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health, with NICHD Contracts HHSN267200700027C, HHSN267200800027C, HHSN275200800016C, HHSN275201100002C, HHSN275200503396C, and HHSN275201100014C. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Al-Saleh I, Al-Doush I, Alsabbaheen A, Mohamed GED, Rabbah A. Levels of DDT and its metabolites in placenta, maternal and cord blood and their potential influence on neonatal anthropometric measures. Sci Total Environ. 2012;416:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki Y. Polychlorinated biphenyls, polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, and polychlorinated dibenzofurans as endocrine disrupters--what we have learned from Yusho disease. Environ Res. 2001;86(1):2–11. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR . Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Atlanta, GA: [accessed April 20, 2013]. 2002. Public Health Statement for DDT, DDE, and DDD. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/phs/phs.asp?id=79&tid=20. [Google Scholar]

- Barr DB, Wang RY, Needham LL. Biologic monitoring of exposure to environmental chemicals throughout the life stages:requirements and issues for consideration for the National Children’s Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1083–1091. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergonzi R, Specchia C, Dinolfo M, Tomasi C, De Palma G, Frusca T, Apostoli P. Distribution of persistent organochlorine pollutants in maternal and foetal tissues:Data from an Italian polluted urban area. Chemosphere. 2009;76:747–754. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivik K, Sweetman A, Pacyna JM, Jones KC. Towards a global historical emission inventory for selected PCB congeners — a mass balance approach:1. Global production and consumption. Sci Total Environ. 2002;290:181–198. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(01)01075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks K, Hasan H, Samineni S, Gangur V, Karmaus W. Placental p,p’–dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene and cord blood immune markers. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2007;18:621–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DL, De Vault DS, Swackhamer DL. On the rate of decline of persistent organic contaminants in lake trout (salvelinus namaycush) from the Great Lakes, 1970–2003. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:2004–2010. doi: 10.1021/es903191u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congress Children’s Health Act of 2000, Public Law 106-310. 2000 Oct 17; 2000, 114 Stat. 1101, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-106publ310/pdf/PLAW-106publ310.pdf.

- Curley A, Copeland MF, Kimbrough RD. Chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides in organs of stillborn and blood of newborn babies. Arch Environ Health. 1969;19:628–32. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1969.10666901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnerud PO, Eriksen GS, Jóhannesson T, Larsen PB, Viluksela M. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers: occurrence, dietary exposure, and toxicology. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(Suppl 1):49–68. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassanayake RMAPS, Wei H, Chen RC, Li A. Optimization of the matrix solid phase dispersion extraction procedure for the analysis of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in human placenta. Anal Chem. 2009;81:9795–9801. doi: 10.1021/ac901805d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKoning EP, Karmaus W. PCB exposure in utero and via breast milk. A review. J Exposure Analy Environ Epidemiology. 2000;10(3):285. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann CJ, Miller RK. Placental Transport, Metabolism and Toxicity of Metals. In: Chang LW, editor. Toxicology of Metals. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Fla: 1996. pp. 1003–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen M, Thomsen M, Vorkamp K, Knudsen LE. Patterns and concentration levels of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in placental tissue of women in Denmark. Chemosphere. 2009a;76(11):1464–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen M, Vorkamp K, Thomsen M, Knudsen LE. Human internal and external exposure to PBDEs – a review of levels and sources. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2009b;212:109–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen M, Vorkamp K, Mathiesen L, Mose T, Knudsen LE. Placental transfer of the polybrominated diphenyl ethers BDE-47, BDE-99 and BDE-209 in a human placenta perfusion system: an experimental study. Environ. Health. 2010;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómara B, Athanasiadou M, Quintanilla–López JE, González MJ, Bergman Å . Polychlorinated biphenyls and their hydroxylated metabolites in placenta from Madrid mothers. Environ Sci Pollu Res. 2012;19(1):139–147. doi: 10.1007/s11356-011-0545-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómara B, Herrero L, Ramos JJ, Mateo JR, Fernandez MA, Garcia JF, Gonzalez MJ. Distribution of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in human umbilical cord serum, paternal serum, maternal serum, placentas, and breast milk from Madrid population, Spain. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41(20):6961–6968. doi: 10.1021/es0714484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbstman JB, Sjödin A, Kurzon M, Lederman SA, Jones RS, Rauh V, Needham LL, Tang D, Niedzwiecki M, Wang RY, Perera F. Prenatal exposure to PBDEs and neurodevelopment. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(5):712–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901340. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hites RA. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in the environment and in people: a meta-analysis of concentrations. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:945–956. doi: 10.1021/es035082g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howdeshell KL. A model of the development of the brain as a construct of the thyroid system. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 3):337–348. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar GV, Rapp A. Human placenta as a ‘dual’ biomarker for monitoring fetal and maternal environment with special reference to potentially toxic trace elements: Part 1: Physiology, function and sampling of placenta for elemental characterization. SciTotal Environ. 2001;280(1):195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(01)00825-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusko TA, Sonneborn D, Palkovicova L, Kocan A, Drobna B, Trnovec T, Hertz-Picciotto I. Pre- and postnatal polychlorinated biphenyl concentrations and longitudinal measures of thymus Volume in infants. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:595–600. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGuardia MJ, Hale RC. Detailed polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) congener composition of the widely used penta-, octa-, and deca-pbde technical flame-retardant mixtures. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:6247–6254. doi: 10.1021/es060630m. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RK, Peters P, McHatten P. Occupational, industrial and environmental exposures during pregnancy. In: Schaefer Ch., Peters P, Miller RK., editors. Drugs during Pregnancy and Lactation. Academic Press; 2007. pp. 561–608. [Google Scholar]

- Myllynen P, Pasanen M, Pelkonen O. Human placenta: a human organ for developmental toxicology research and biomonitoring. Placenta. 2005;26(5):361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myren M, Mose T, Mathiesen L, Knudsen LE. The human placenta – an alternative for studying foetal exposure. Toxicol in Vitro. 2007;21(7):1332–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DO, Carr JA, editors. Endocrine disruption: biological bases for health effects in wildlife and humans. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rappolt RT, Hale WE. p,p–DDE and p,p–DDT Residues in human placentas, cords, and adipose tissue. Clini Toxicol. 1968;1:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Reichrtová E, Ciznar P, Prachar V, Palkovicova L, Veningerova M. Cord serum immunoglobulin e related to the environmental contamination of human placentas with organochlorine compounds. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(11):895–899. doi: 10.1289/ehp.107-1566702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter A, Papke O, Tung KC, Joseph J, Harris TR, Dahlgren J. Polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants in the U.S. population: current levels, temporal trends, and comparison with dioxins, dibenzofurans, and polychlorinated biphenyls. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:199–211. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000158704.27536.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter A, Pavuk M, Papke O, Ryan JJ, Birnbaum L, Rosen R. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in U.S. mothers’ milk. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1723–1729. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Main KM, Virtanen HE, Damgaard IN, Haavisto AM, Kaleva M, et al. From mother to child: Investigation of prenatal and postnatal exposure to persistent bioaccumulative toxicants using breast milk and placenta biomonitoring. Chemosphere. 2007;67(1):S256–S262. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.05.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjödin A, Jones RS, Focant JF, Lapeza C, Wang RY, McGahee EE, III, et al. Retrospective time-trend study of polybrominated diphenyl ether and polybrominated and polychlorinated biphenyl levels in human serum from the United States. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(6):654–658. doi: 10.1289/ehp.112-1241957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjödin A, Patterson DG, Jr, Bergman Å . A review on human exposure to brominated flame retardants – particularly polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Environ Int. 2003;29:829–839. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(03)00108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slikker W, Miller RK. Placental metabolism and transfer - role in developmental toxicology. In: Kimmel C, Buelke-Sam J, editors. Developmental Toxicology. 2nd edition Raven Press; New York: 1994. pp. 245–283. [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Basu I, Hites RA. Temporal trends of polychlorinated biphenyls in precipitation and air at Chicago. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:1178–1183. doi: 10.1021/es051725b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasuga T, Senthilkumar K, Watanabe K, Takemori H, Shimomura H, Nagayama J. Accumulation profiles of organochlorine pesticides and PBDEs in mother’s blood, breast milk, placenta and umbilical cord: possible transfer to infants. Organohalogen Comp. 2006;68:2186–2189. [Google Scholar]

- Wang SL, Chang YC, Chao HR, Li CM, Li LA, Lin LY, Päpke O. Body burdens of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, dibenzofurans, and biphenyls and their relations to estrogen metabolism in pregnant women. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(5):740–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadorozhnaja TD, Little RE, Miller RK, Mendel NA, Taylor RJ, Presley BJ, Gladen BC. Concentrations of arsenic, cadmium, copper, lead, mercury, and zinc in human placentas from two cities in Ukraine. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2000;61:255–63. doi: 10.1080/00984100050136571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Ruan X, Li Y, Yan M, Qin Z. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in aborted human fetuses and placental transfer during the first trimester of pregnancy. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(11):5939–5946. doi: 10.1021/es305349x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zota AR, Park J-S, Wang Y, Petreas M, Zoeller RT, Woodruff TJ. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers, hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and measures of thyroid function in second trimester pregnant women in California. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(18):7896–7905. doi: 10.1021/es200422b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zota AR, Rudel RA, Morello-Frosch RA, Brody JG. Elevated house dust and serum concentrations of PBDEs in California: unintended consequences of furniture flammability standards? Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42(21):8158–8164. doi: 10.1021/es801792z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.