Abstract

Aedes aegypti is the principal vector of dengue virus (DENV) throughout the tropical world. This anthropophilic mosquito species needs to be persistently infected with DENV before it can transmit the virus through its saliva to a new vertebrate host. In the mosquito, DENV is confronted with several innate immune pathways, among which RNA interference is considered the most important. The Ae. aegypti genome project opened the doors for advanced molecular studies on pathogen-vector interactions including genetic manipulation of the vector for basic research and vector control purposes. Thus, Ae. aegypti has become the primary model for studying vector competence for arboviruses at the molecular level. Here, we present recent findings regarding DENV-mosquito interactions, emphasizing how innate immune responses modulate DENV infections in Ae. aegypti. We also describe the latest advancements in genetic manipulation of Ae. aegypti and discuss how this technology can be used to investigate vector transmission of DENV at the molecular level and to control transmission of the virus in the field.

Keywords: dengue virus, mosquito, Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, virus transmission, innate immunity, RNA interference, Toll, JAK-STAT, apoptosis, transgenesis, transposon, site-specific recombination, promoter, gene-knockout, gene expression, homing endonuclease, TALEN, zinc finger nuclease, Wolbachia, RIDL, population replacement, effector gene, viral tropical medicine

Introduction

The global epidemiology of dengue virus (Flaviviridae; Flavivirus; dengue virus 1–4; [DENV1–4]) depends on the presence of two mosquito vectors, Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti (L.) and Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse). Ae. aegypti is the principal DENV vector in urban environments of tropical countries [1]. This mosquito species is of African origin and breeds in tropical regions of Africa, Asia, Australia, South-Pacific, the Middle East, and the Americas [2]. Ae. aegypti exemplifies a peridomestic, anthropophilic day biter. In contrast, Ae. albopictus is a zoophilic, catholic biter, which easily adapts to peridomestic environments in temperate regions [3,4]. During the last few decades, Ae. albopictus has undergone a dramatic expansion in its geographic distribution [5]. However, due to lower viral infection and transmission rates, Ae. albopictus is considered to be a less important vector for DENV than Ae. aegypti. The DENV disease cycle between the mosquito vector and the human host requires persistent infection of the mosquito [6]. DENV typically causes disease symptoms in the human host but there is no apparent pathology associated with the infection of the mosquito [7]. DENV is acquired by female mosquitoes while orally ingesting a viremic bloodmeal from a human host. A correlation exists between disease severity of the host, high DENV titer in the blood and the level of infection of the mosquito vector [8]. The ingested bloodmeal enters the midgut lumen to be digested, and virions enter midgut epithelial cells and replicate [9]. Virus then spreads cell-to-cell to form infection foci in the midgut epithelium [10]. At 4–7 days post-infection, DENV starts disseminating from the midgut to secondary tissues such as muscle, nerve, fat body, ovary, hemocytes, and eventually salivary glands, which typically become infected between 10–14 days post-infectious bloodmeal. Once the salivary glands are infected, DENV is transmitted to a new human host through release of virion-containing mosquito saliva during feeding. The extrinsic incubation period (EIP) is defined as the time period between initial infection of the vector and appearance of virus in the saliva [11]. The EIP can vary according to virus strain, mosquito strain, and virus titer in the mosquito. The midgut and salivary glands constitute physical barriers, which DENV needs to overcome before it can be transmitted [12]. A midgut infection barrier (MIB) can prevent the virus from infecting the mosquito midgut, while a midgut escape barrier (MEB) allows DENV to productively infect midgut epithelial cells but prevents the virus from disseminating from the midgut. The presence of MIB and MEB depend on specific virus strain-mosquito strain combinations [13,14]. Although higher midgut infection rates have been observed for DENV in Ae. albopictus, dissemination rates were significantly lower in this mosquito species compared to Ae. aegypti [5].

Vertical transmission of DENV by Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus through a transovarial route has been demonstrated in several studies [15,16]. Transovarial transmission rates (percentage of infected females transmitting virus to their progeny) of up to 13 % for Ae. aegypti and 11–41 % for Ae. albopictus have been reported [17,18]. Vertical transmission of DENV strongly affects its etiology because it allows the virus to be maintained among mosquitoes during inter-epidemic periods, i.e. during dry seasons or winter seasons, when there is only little active horizontal DENV transmission.

Molecular interactions between DENV and innate immune pathways of Ae. aegypti

During infection of a mosquito, DENV is confronted with several innate immune pathways such as RNA interference (RNAi), Toll, and JAK-STAT, which modulate DENV infection. As with MIB and MEB, the effectiveness of these pathways in inhibiting DENV replication likely varies depending on the virus and mosquito strains in question.

RNAi

RNAi has been considered the most important antiviral innate immune pathway in Ae. aegypti [7]. The RNAi pathway in mosquitoes follows the same principle as described in great detail for Drosophila [19–21]. The genome of Ae. aegypti encodes key gene homologs of the three small RNA (miRNA, siRNA, and piRNA) regulatory pathways [22,23]. Initial studies showed that the siRNA pathway in Ae. aegypti could be triggered to silence DENV replication. Mosquitoes infected with recombinant Sindbis virus (Togaviridae; Alphavirus; [SINV]) expressing ~300 nt anti-sense cDNAs complementary to the genomes of DENV1, 2, 3, or 4 silenced DENV replication in serotype-specific manner [24]. Dicer2 of the siRNAi pathway senses long double-stranded (ds)RNA formed during replication of RNA viruses and cleaves it into 21 base-pair (bp) duplexes, the hall-mark of active RNAi [25,26]. In DENV-infected mosquito tissue, DENV-derived siRNAs are readily detectable, indicating RNAi-mediated degradation of viral genomes. Nevertheless, DENV is still able to persistently infect the mosquito, indicating that the virus is counteracting the mosquito’s RNAi response. A recent study suggests that a flavivirus-specific small RNA (subgenomic flavivirus RNA) originating from the 3’UTR of the virus has the ability to inhibit cleavage of dsRNA by Dicer [27].

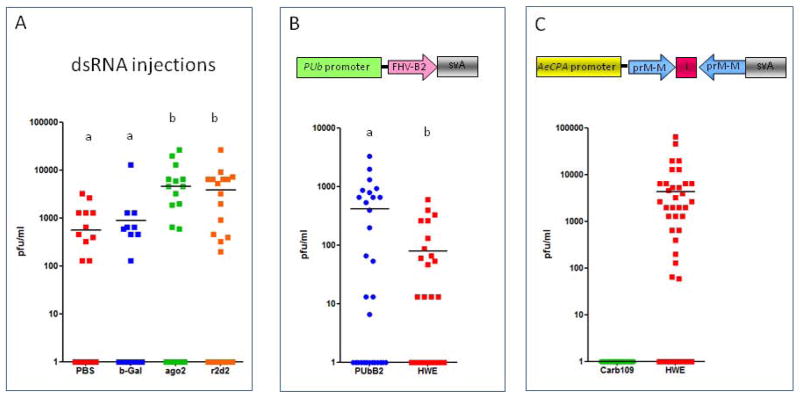

Impairment of the RNAi pathway in Ae. aegypti by transiently silencing key genes, dcr2, r2d2, or ago2 significantly increased DENV2 replication in the mosquito up to 10-fold and shortened the EIP by three days (Fig. 1a); [26]. Likewise, transgenic over-expression of an RNAi suppressor, B2 of Flockhouse virus (Nodaviridae; Alphanodavirus) blocked dsRNA processing by dicer2 and caused a significant increase in DENV2 titers in midgut tissue of Ae. aegypti (Fig. 1b); [28]. These observations indicate that the RNAi pathway acts as a gate-keeper in Ae. aegypti, modulating DENV2 replication to protect the mosquito from virus-induced pathogenic effects when exceeding a tolerable concentration in the infected cell.

Fig. 1.

DENV2 is targeted by the innate RNAi pathway in Aedes aegypti and responds to RNAi pathway manipulation in mosquitoes. (a) Intrathoracic injection of dsRNAs derived from sequences of the RNAi pathway genes ago2 and r2d2 into mosquitoes of the Higgs White Eye (HWE) strain triggers RNAi and leads to transient silencing of these genes. In presence of the impaired RNAi pathway, DENV2 titers are significantly increased at 7 days post-infectious bloodmeal (pbm). Controls: (HWE) mosquitoes injected with PBS or dsRNA derived from the β-Gal gene (non-target control). Each data point represents the virus titer of an individual female. (b) Transgene-mediated, constitutive overexpression of a potent RNAi suppressor (FHV-B2) in midgut tissue of PUbB2 mosquitoes impairs the RNAi pathway by inhibiting dsRNA processing. This leads to a significant increase of DENV2 titers in midguts at 7 days pbm in comparison to the HWE control. Each data point represents the virus titer of an individual female midgut. (c) Transgene-mediated expression of an IR effector complementary to the prM-M gene of DENV2 triggers RNAi against the virus in midguts of bloodfed females. Transgenic mosquitoes of line Carb109 are completely refractory to the virus. In contrast, HWE control mosquitoes are highly susceptible to DENV2 at 7 days pbm. DENV2 bloodmeal titers: 106–107 plaque forming units (pfu)/ml. Each data point represents the virus titer of an individual female. Virus titers were assessed by plaque assays in LLC-MK2 monkey kidney cells. Letters a, b next to numbers represent statistically significant groupings (p-value:<0.05; Tukey-Kramer Test).

Toll

In invertebrates, the Toll pathway is activated by gram-positive bacteria, fungi and viruses through pattern recognition receptors [29]. DENV infection leads to Toll pathway activation in midgut tissue of Ae. aegypti [30,31]. As a consequence, the negative regulator of the pathway, Cactus, is degraded resulting in the nuclear translocation of various transcription factors such as Relish (Rel1), and release of antimicrobial peptides. Transient silencing of Cactus spontaneously activates the Toll pathway. In DENV2-infected Ae. aegypti, silencing of Cactus resulted in a ~4-fold reduction of DENV2 infection levels in midgut tissue [30]. Impairment of the Toll pathway by transient silencing of the adapter protein-encoding MYD88 gene resulted in a 2.7-fold viral load increase of DENV2. In contrast to Toll, the Immune Deficiency (Imd) pathway, typically responsive to gram-negative bacteria in invertebrates, has not been shown to be activated in DENV2-infected Ae. aegypti.

JAK-STAT

The Janus kinase and signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway is a cytokine signaling pathway in mammals. In Drosophila, extracellular binding of the ligand Unpaired (Upd) to the receptor Domeless (Dome) initiates the JAK-STAT pathway [32]. As a result, Dome undergoes a conformational change, leading to self-phosphorylation of the associated Janus kinase, Hop, which then phosphorylates Dome. This results in the formation of docking sites for the cytoplasmic STATs. The recruitment of STATs by the Dome/Hop complex induces phosphorylation of STATs, leading to their translocation into the nucleus and transcription activation of specific target genes. Two negative regulators, PIAS (protein inhibitor of activated STAT) and SOCS (suppressor of cytokine signaling) can suppress the JAK-STAT pathway. In Ae. aegypti the JAK-STAT pathway is activated upon DENV2 infection of the midgut [33]. Impairment of the JAK-STAT pathway by transient silencing of Hop and Dome significantly increased DENV2 infection levels by up to 3-fold. Silencing of PIAS, however, reduced DENV2 infection by up to 5-fold.

In summary, RNAi is the major antiviral pathway specifically targeting actively replicating DENV in the cytoplasm of Ae. aegypti cells [7]. Toll and JAK-STAT pathways both contribute to the control of DENV infection. However, it is not clear to what extent either pathway specifically responds to the presence of DENV in Ae. aegypti. So far, viral determinants that would trigger Toll and JAK-STAT pathway activation have not been elucidated.

Apoptosis

There have been recent efforts to elucidate the role of apoptosis in arbovirus infection of Ae. aegypti. The Ae. aegypti genome encodes numerous genes with homology to apoptosis-related genes identified in Drosophila, including eleven caspases, three inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins, two IAP antagonists, and orthologs of Ark, Dnr1, and Fadd [34]. Several of the Ae. aegypti apoptosis-related genes have been shown to function in apoptosis including the initiator caspase AeDronc, the effector caspases CASPS7 and CASPS8, the caspase inhibitors AeIAP1 and AeDnr1, and the IAP antagonists IMP and AeMx [34–37].

So far, effects of apoptosis on arbovirus infection of Ae. aegypti have been investigated in two experiments using SINV as a model virus. The first experiment showed that transient silencing of IAP1 in Ae. aegypti induced spontaneous apoptosis in midgut tissue of females, leading to a 60–70% increase in mortality [36]. Surprisingly, this also led to increased SINV replication and dissemination rates, while silencing of AeDronc reduced SINV replication and dissemination. It was speculated that inducing widespread apoptosis by silencing of AeIAP1 may have weakened other innate defenses of the mosquitoes, resulting in higher levels of virus replication. In the second approach, expression of the apoptosis-inducing Drosophila reaper gene from a recombinant SINV also induced apoptosis in the mosquito midgut but resulted in reduced SINV titers at early stages of infection [38]. Furthermore, examining SINV progeny from these mosquitoes revealed a strong selective advantage for viruses that had lost their reaper insert, indicating that induction of apoptosis by SINV was deleterious for the virus. Thus, although apoptosis is usually not observed in naturally occurring virus-vector combinations, it may occur in non-compatible combinations, involving specific arbovirus and/or mosquito strains. A current research effort aims at elucidating the role of apoptosis in DENV infection of Ae. aegypti.

Genetic manipulation of Ae. aegypti to investigate and control DENV transmission

Genetic manipulation of Ae. aegypti has become a well-established procedure, which has greatly advanced our ability to investigate mosquito gene – pathogen gene interactions. Transgenic Ae. aegypti have been generated for three major purposes: i) vector and/or pathogen control, ii) study of gene function, iii) tool development to improve genetic manipulation. Further development and refinement of molecular-genetic tools has laid the foundation for innovative approaches to investigate the molecular basis of vector competence for DENV in Ae. aegypti and to develop novel strategies for mosquito/DENV control in the field.

Tools for the genetic manipulation of Ae. aegypti

Transposable elements

Since the initial report of successful germline transformation of Ae. aegypti [39], considerable progress regarding the genetic manipulation of this mosquito species has been made. As insertion vectors for germline transformation, DNA-based Class II transposable elements (TE) such as (Tc1) mariner Mos1 (originating from D. mauritiana), piggyBac (originating from Trichoplusia ni), or Hermes of the hAT superfamily (origin: Musca domestica) have been used [40]. These TE have poor mobility in the mosquito germline. In numerous germline transformation experiments of Ae. aegypti, mariner Mos1 has shown predictable integration patterns, thus making it an ideal choice among TE insertion vectors [41]. Research groups also use piggyBac routinely for the transformation of this mosquito species as well as for the genetic manipulation of Ae. albopictus [42,43].

Site-specific integration

A major disadvantage associated with the use of Class II TE is their quasi-random integration pattern, depending only on short recognition motifs such as TA for mariner Mos1 or TTAA for piggyBac [40].

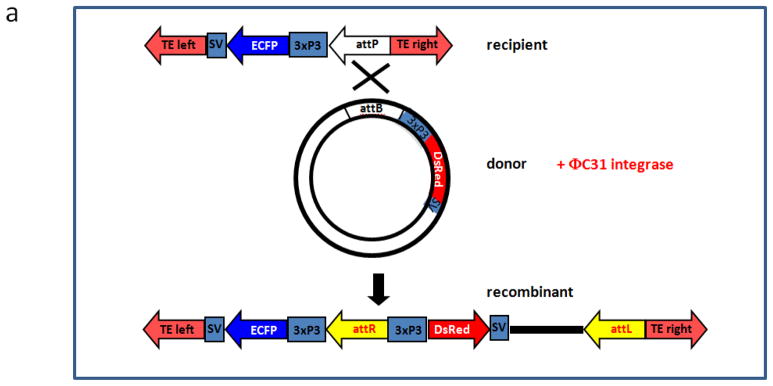

Since the TE integration site is random, transgene expression is often affected by position effect variegation [44]. To ensure predictable and stable transgene expression, alternative transformation systems such as the ΦC31 site-directed integration system have been successfully used in Ae. aegypti (Fig. 2a); [28,42,45,46]. The underlying principle is a recombination event mediated by the ΦC31 integrase between a short recognition (=docking) sequence (attP), which has been inserted into the genome of the target organism and a corresponding recognition sequence (attB), which is linked to the donor encoding the gene-of-interest. Since the attP site containing docking strain needs to be generated using a TE as insertion vector, a challenge of the ΦC31 system is to obtain docking strains, which contain the attP site in an optimal genome locus supporting strong gene-of-interest expression levels [46].

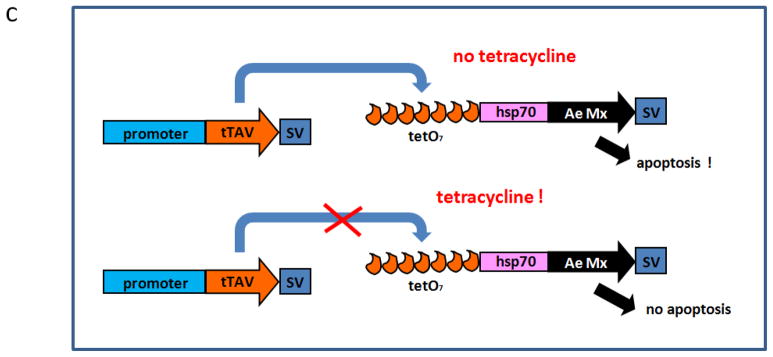

Fig. 2.

Tools for the genetic manipulation and control of Aedes aegypti. (a) Principle of the ΦC31 site-directed recombination system. With the help of a transposable element (TE) the phage attachment site attp is anchored in the genome of the docking strain. The docking strain is then ‘super-transformed’ with the attB site containing donor plasmid, which also contains the gene-of-interest. Co-injecting the donor and in vitro transcribed ΦC31 integrase into embryos of the docking strain leads to a recombination event between attP and attB. As a consequence, the entire donor plasmid is integrated at the attP site; attP and attB are converted into attL and attR. Using the ΦC31 site-directed recombination system position effects can be avoided because the transgene is integrated at a defined locus. (b) Principle of the Gal4-UAS binary expression system. A transgenic driver line is generated to express the yeast Gal4 activator from a promoter-of-choice. The responder line contains the Gal4 binding site (UAS) and the gene-of-interest (i.e, the EGFP reporter) to be expressed under control of a minimal promoter such as hsp70. Crossing the two transgenic mosquito lines will result in progeny in which the Gal4 protein is binding to the UAS sequences. As a result, the EGFP reporter is expressed from the promoter-of-choice. The advantage of this system is that tissue-specific promoters can be tested with genes-of-interest in various combinations by setting up simple crossings between different driver and responder lines. (c) Principle of the RIDL system for population reduction of Ae. aegypti. The tetracycline repressible system shown here consists of two components. One component encodes the tetracycline-repressible transcriptional activator, tTAV, which is under control of a promoter-of-choice, i.e., a female-specific promoter (to achieve female-specific killing). The other component contains the tTAV binding site tetO7 linked to a pro-apoptotic gene such as michelob x (AeMx), which is under control of a minimal promoter (hsp70). In absence of tetracycline, tTAV will bind to tetO7, resulting in expression of AeMx. Addition of tetracycline as a food supplement will result in binding of tTAV to tetracycline. Tetracycline-bound tTAV shows an altered structure, which is no longer complementary to tetO7 and consequently, AeMx is not expressed.

Abbreviations: TE left and right: lest, right terminal inverted-repeats of the transposable element; 3xP3: eye tissue-specific promoter; EGFP, ECFP, DsRed: fluorescent reporters; SV: transcription termination signal of Simian virus 40; Vg: promoter of the Ae. aegypti vitellogenin 1 gene; hsp70: heat-shock promoter 70 of Drosophila; AeMx: michelob x gene of Ae. aegypti.

UAS-Gal4 binary expression system

Another important tool for improved gene-of-interest expression in Ae. aegypti was the development of the binary UAS-Gal4 expression system [47]. The system is based on the production of two independent transgenic lines: (1) the driver line containing the yeast Gal4 activator gene under control of a promoter-of-choice and (2) the responder line containing the binding sites (UAS=upstream activating sequences) for the Gal4 protein upstream of the gene-of-interest expression cassette (Fig. 2b). To use in Ae. aegypti, the essential DNA-binding and activation domains of Gal4 were fused directly, resulting in the chimeric Gal4Δ activator [48]. In a proof-of-principle experiment, Gal4Δ of the transgenic driver line was placed under control of the bloodmeal-inducible fat body-specific Vg promoter. The responder line contained of the EGFP reporter fused to UAS. Crossing the two transgenic lines resulted in hybrids strongly expressing EGFP in fatbody of bloodfed females, confirming the functionality of the system. An important advantage of the system is that no expression of the gene of interest takes place when the trans-activator is absent. This allows transgenic overexpression of genes, which have potentially harmful effects for the organism.

Promoters

A range of promoters has been isolated from Ae. aegypti, allowing predictable gene-of-interest expression in various tissues. AeCPA and Vg are female-specific, bloodmeal-inducible promoters that drive gene expression in midgut epithelial cells and fat body, respectively [49–51]. Both promoters activate gene expression for relatively short periods of time, 4–32 h post-bloodmeal (pbm) (AeCPA) and 2–24 h pbm (Vg). The Ae. aegypti 30K promoter is a strong constitutive promoter for gene expression in the distal-lateral lobes of salivary glands [52]. Recently, promoters of two Ae. aegypti ubiquitin genes, Ub(L40) and PUb, have been characterized and tested in transgenic mosquitoes [53]. The Ub(L40) promoter drives gene expression predominantly in larvae and ovaries, whereas the PUb promoter drives gene expression in embryos, larvae, pupae, males, and constitutively in the female midgut. Two heat-shock protein 70 (hsp70)-like promoters of Ae. aegypti, AaHsp70Aa, and AaHsp70Bb were recently described, which significantly activated transcription following a 1 h exposure at 39ºC in various mosquito tissues, such as salivary glands, midguts, and ovaries [54]. For female germline expression and for male-only expression the nanos and testes-specific b2 tubulin promoters, respectively, have been isolated and characterized [55,56].

Investigating gene function in Ae. aegypti by genome editing

Genome editing is an innovative approach to investigate gene function in Ae. aegypti in relation to DENV infection. Several research efforts have been aimed at developing tools to edit the genome of Ae. aegypti via targeted gene-knockout. So far, three different approaches have been successfully applied for targeted gene disruption in Ae. aegypti: homing endonucleases (HEG) [57], zinc finger nucleases (ZFN) [58–60], and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN) [61–64].

HEG are selfish elements catalyzing specific dsRNA breaks in the genome of their target organism [57].

Proof-of-concept experiments showed that HEG such as I-PpoI, I-SceI, I-CreI, and Y2-I-AniI are active in the soma and germline of Ae. aegypti [65,66]. HEG expression in a transgenic mosquito line resulted in target site-specific dsDNA breaks followed by DNA gap repair via single-strand annealing and non-homologous end-joining. As a consequence, a reporter gene was excised, which was flanked by HEG-specific recognition sequences in the engineered Ae. aegypti line. Despite these successful demonstrations, a major task remains to re-engineer HEG for targeted gene-of-interest knockout in Ae. aegypti. Nevertheless, HEG appear to be promising candidates for a gene drive system, due to their ability to invade populations through dsDNA break induction.

Gene-of-interest-specific genome editing in Ae. aegypti has been recently accomplished when using TALEN and ZFN. TALEN have been engineered to disrupt via the germline the Ae. aegypti kmo gene encoding a protein essential for eye pigmentation [67]. Up to 40% of surviving mosquito individuals had disrupted kmo alleles in which 1–7 bp of the CDS were deleted, resulting in a lack of eye pigmentation. This observation indicates that TALEN are highly active in the Ae. aegypti germline.

Using ZFN the coding sequence of orco, encoding the co-receptor of odorant receptors, was disrupted in the germline of Ae. aegypti, which caused 1 to >20 nucleotide deletions in the target sequence among the different mutant lines [68]. Resulting orco gene-knockout mosquitoes produced a phenotype, which did not respond to human scent in the absence of CO2. Together with genome editing, whole-transcriptome analysis using NextGen sequencing technology can be used to reveal how loss-of-gene function affects other pathways in the mosquito. Combining these two powerful techniques may lead to the discovery of novel gene candidates that antagonize DENV in the mosquito vector.

Transgene-mediated manipulation of gene expression levels in Ae. aegypti

Stable, inheritable disruption of an endogenous gene could be limited by the fact that the resulting loss-of-function genotype would be non-viable. Furthermore, engineering of a nuclease to specifically target a gene-of-interest in the genome is still technically challenging and/or costly. Thus, transgene-mediated, inducible and tissue-specific knockdown of endogenous genes is an alternative technique to investigate endogenous gene-function in Ae. aegypti. The approach is based on temporal and/or spatial expression of a long inverted-repeat (IR) RNA from a transgene as a trigger for gene-of-interest-specific RNAi. This can result in strong phenotypes and is technically simple to achieve [69,70]. As an example, midgut-specific, bloodmeal-inducible expression of an IR effector targeting the RNAi pathway gene dcr2 resulted in about 50% silencing efficiency for ~28 h pbm [70]. This level of RNAi impairment was sufficient to significantly increase SINV replication in those mosquitoes.

Genetic pest management strategies to control Ae. aegypti and DENV transmission in the field

The on-going spread of multi-level insecticide resistance among Ae. aegypti populations in DENV endemic regions of the world demands the development of alternative Ae. aegypti/DENV control strategies, which are largely based on genetic pest management [71]. Three major novel control strategies that avoid the use of insecticides are currently being developed.

Wolbachia

Moreira and colleagues [72] discovered that strains of Wolbachia (Rickettsiales), a maternally inherited Gram-negative endosymbiotic bacterium, are capable of blocking DENV replication in Ae. aegypti. Wolbachia occurs naturally in ~65% of all insect species [73]. In nature, numerous mosquito species including Ae. albopictus and Culex pipiens but not Ae. aegypti are Wolbachia-infected [74]. The bacterium can cause cytoplasmic incompatibility in the male sperm leading to embryo lethality when infected males mate with uninfected females. However, mating between infected males and infected females leads to the production of offspring, thereby favoring infected females over non-infected ones. Thus, Wolbachia has the ability to drive itself into populations [75]. Two Wolbachia strains (wMel and wMelPop-CLA) naturally occurring in Drosophila have been successfully trans-infected into Ae. aegypti [76,77]. Both Wolbachia strains limited DENV2 infection in the mosquito by blocking the virus’ ability to disseminate from the midgut into mosquito saliva and affected mosquito fitness [75,77]. The mechanism behind the Wolbachia-induced resistance to DENV2 in Ae. aegypti is not fully understood so far [77–82]. A major open field trial was conducted in which ~300,000 Wolbachia wMel-infected Ae. aegypti raised under laboratory conditions were deliberately released in 2011 at two locations near Cairns, Australia [83]. The frequency of Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti initially increased to more than 15% in both locations at 2-weeks post-release. After additional releases, frequencies increased to >60% and reached near fixation levels five weeks after releases were terminated. These observations suggest that Wolbachia could potentially become a powerful bio-control agent to suppress DENV transmission by Ae. aegypti in endemic areas.

RIDL

RIDL (Release of Insects carrying Dominant Lethals), is a novel genetic female-killing (FK) control strategy aimed at mosquito population reduction [84]. The technique involves the generation of transgenic mosquitoes in which lethal genes are sex-specifically and conditionally over-expressed [85]. An example would be to place a pro-apoptotic gene under control of a female-specific promoter. Using the TET on/off transcriptional activation system, expression of the pro-apoptotic gene is repressed in the presence of tetracycline, which is added as a food supplement during mosquito rearing (Fig. 2c). This allows both sexes to be viable for breeding purposes. When releasing RIDL mosquitoes into the environment, tetracycline is absent resulting in female-specific lethal gene expression. Inheritance of the dominant gene construct by wild-type mosquitoes causes only male offspring to survive, which will lead to collapse of the mosquito population over time. Several variants of the RIDL system have been developed for Ae. aegypti over the years, including single or two-component systems, bisex lethals, flightless females and non-sex specific late-acting lethal systems [43,86].

In limited cage experiments, RIDL mosquito populations were unable to reproduce in the absence of tetracycline. Repeated introductions of homozygous RIDL males into cage populations of wild-type mosquitoes at initial ratios of 8.5–10 : 1 (RIDL : wild-type) eliminated the target populations by 10–20 weeks after initial release [86]. This indicates that the RIDL-based population control strategy can be highly successful in the field.

Transgenic expression of anti-DENV effectors

Gene drive system

Another novel concept of DENV control in the field is based on population replacement. Here, DENV-susceptible mosquito populations are replaced by genetically-modified refractory strains [87]. The underlying principle of this genetic pest management strategy involves the design of strong anti-DENV effector genes and a highly species-specific genetic drive system to which the anti-DENV effector needs to be tightly linked [88]. A genetic drive system circumvents Mendelian inheritance patterns and thereby allows the anti-DENV effector, which potentially carries a fitness load, to be driven through a wild-type mosquito population at an accelerated rate until fixation.

Until now, there is no gene drive system readily available for Ae. aegypti. Current attempts to develop gene drivers for Ae. aegypti include the design of HEG and a killer-rescue system based on a synthetic Medea (maternal effect dominant embryonic arrest) variant [89–92]. Medea is a selfish gene element when present in females; all offspring will die if they do not inherit a maternal or paternal copy of the element. This feature enables Medea to drive itself through populations.

Anti-DENV2 effectors

As described above, priming the innate RNAi pathway against DENV is a highly effective approach to target and silence the virus in Ae. aegypti. As a further proof-of-principle for this approach, transgenic mosquitoes have been generated expressing an (578 bp) IR RNA derived from the prM-M encoding sequence of DENV2 under control of the AeCPA promoter [93]. Female mosquitoes of line Carb77 expressed the IR effector between 4–48 h pbm in midgut tissue. The 578 bp dsRNA of the effector was recognized by the endogenous RNAi machinery of the mosquitoes and processed into siRNAs. Carb77 mosquitoes were highly resistant to different strains of orally acquired DENV2 but not to other DENV serotypes or other arboviruses. However, after 17 generations in laboratory culture Carb77 mosquitoes lost their anti-DENV2 resistance phenotype, even though the transgene appeared to be intact [94]. It was speculated that expression of the anti-DENV2 effector was silenced in these mosquitoes. Meanwhile, another transgenic line, Carb109, has been established harboring the same transgene as line Carb77. Current studies show that Carb109 are completely refractory to DENV2 after more than 33 generations in laboratory culture (Fig. 1c); [A.W.E. Franz, I. Sanchez-Vargas, R.R. Raban, W.C. Black, A.A. James, K.E. Olson, unpublished data]. Mathur and colleagues [52] generated transgenic Ae. aegypti in which a similar anti-DENV2 IR effector was placed under control of the constitutive salivary gland-specific 30K promoter. DENV2 titers and infection rates were significantly reduced in salivary glands of the transgenic mosquitoes and the virus was absent in their saliva. However, to further develop the concept of RNAi-mediated transgenic resistance to DENV, an effector molecule needs to be generated that causes resistance to all four DENV serotypes in Ae. aegypti.

Recent mathematical models revealed that “Replace” and “Reduce” (R&R) could be a powerful alternative to sole population replacement [95]. R&R is a combination of population replacement and population reduction (i.e., FK), which could be achieved by inserting an anti-DENV effector transgene into RIDL mosquito strains. The R&R approach promises to be more effective that FK alone, even if the anti-DENV effector would be associated with substantial fitness costs.

Conclusions

The availability of genomic sequences of Ae. aegypti has facilitated detailed studies on the molecular basis of vector competence for DENV. One important outcome of these studies was the discovery of RNAi as the major anti-viral immune pathway modulating DENV replication in the vector. Several studies showed that the RNAi machinery in Ae. aegypti is able to completely silence DENV replication.

Over the past decade, significant advances have been made regarding the genetic manipulation of Ae. aegypti. Novel, tissue-specific promoters have been described and tested, and site-specific integration and binary gene expression systems have been developed to manipulate endogenous gene expression with greater efficiency. Importantly, gene editing tools such as HEG, TALEN, and ZFN have been successfully applied to knockout reporters or endogenous genes in Ae. aegypti.

Several innovative genetic pest management-based control strategies are under development to control Ae. aegypti populations and/or DENV transmission in the field. One of these involves trans-infection with Wolbachia, which can spread through a wild-type population and causes Ae. aegypti to become refractory to DENV. RIDL, as a transgenic alternative to classical sterile insect technology has the potential to eliminate Ae. aegypti populations in the field. Another concept is based on population replacement in which DENV-competent mosquito populations are replaced in the field by mosquitoes, which have been genetically-modified to be refractory to the virus. As a proof-of-concept, inheritable RNAi-based resistance to DENV2 has been successfully engineered in genetically modified Ae. aegypti.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by R01 grant AI091972-01 (PIs: ALP, RJC, AWEF) from the National Institutes of Health. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Alexander W.E. Franz and Rollie J. Clemdeclare that they have no conflict of interest. Lorena Passarelli has received grant funding from NIH/NIAID.

Contributor Information

Dr. Alexander W.E. Franz, Email: franza@missouri.edu.

Dr. Rollie J. Clem, Email: rclem@ksu.edu.

Dr. A. Lorena Passarelli, Email: lpassar@ksu.edu.

References

- 1.Vasilakis N, Weaver SC. The history and evolution of human dengue emergence. Adv Virus Res. 2008;72:1–76. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)00401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higa Y. Dengue Vectors and their Spatial Distribution. Trop Med Health. 2011;39(4):17–27. doi: 10.2149/tmh.2011-S04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieng H, Saifur RGM, Hassan AA, et al. Indoor-Breeding of Aedes albopictus in Northern Peninsular Malaysia and Its Potential Epidemiological Implications. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rezza G. Aedes albopictus and the reemergence of Dengue. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5•.Lambrechts L, Scott TW, Gubler DJ. Consequences of the expanding global distribution of Aedes albopictus for dengue virus transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(5):e646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000646. This article analyzes the role of Ae. albopictus in DENV epidemics in comparison to Ae. aegypti. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blair CD, Adelman ZN, Olson KE. Molecular strategies for interrupting arthropod-borne virus transmission by mosquitoes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:651–661. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.651-661.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Blair CD. Mosquito RNAi is the major innate immune pathway controlling arbovirus infection and transmission. Future Microbiol. 2011;6(3):265–277. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.11. This review article discusses the role of RNAi as the major antiviral immune pathway in Ae. aegypti. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaughn DW, Green S, Kalayanarooj S, Innis BL, Nimmannitya S, et al. Dengue viremia titer, antibody response pattern, and virus serotype correlate with disease severity. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:2–9. doi: 10.1086/315215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato N, Mueller CR, Fuchs JF, et al. Evaluation of the Function of a Type I Peritrophic Matrix as a Physical Barrier for Midgut Epithelium Invasion by Mosquito-Borne Pathogens in Aedes aegypti. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8(5):701–712. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salazar MI, Richardson JH, Sanchez-Vargas I, Olson KE, Beaty BJ. Dengue virus type 2: replication and tropisms in orally infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer JH, Hudson NP. The incubation period of yellow fever in the mosquito. J Exp Med. 1928;48(1):147–153. doi: 10.1084/jem.48.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosio CF, Fulton RE, Salasek ML, Beaty BJ, Black WC., 4th Quantitative trait loci that control vector competence for dengue-2 virus in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Genetics. 2000;156(2):687–698. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.2.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett KE, Olson KE, Muñoz Mde L, et al. Variation in vector competence for dengue 2 virus among 24 collections of Aedes aegypti from Mexico and the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67(1):85–92. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoo CC, Doty JB, Held NL, Olson KE, Franz AW. Isolation of midgut escape mutants of two American genotype dengue 2 viruses from Aedes aegypti. Virol J. 2013;10(1):257. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thongrungkiat S, Wasinpiyamongkol L, Maneekan P, Prummongkol S, Samung Y. Natural transovarial dengue virus infection rate in both sexes of dark and pale forms of Aedes aegypti from an urban area of Bangkok, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2012;43(5):1146–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tu WC, Chen CC, Hou RF. Ultrastructural studies on the reproductive system of male Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) infected with dengue 2 virus. J Med Entomol. 1998;35(1):71–76. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosio CF, Thomas RE, Grimstad PR, Rai KS. Variation in the efficiency of vertical transmission of dengue-1 virus by strains of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 1992;29(6):985–989. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/29.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angel B, Joshi V. Distribution and seasonality of vertically transmitted dengue viruses in Aedes mosquitoes in arid and semi-arid areas of Rajasthan, India. J Vector Borne Dis. 2008;45(1):56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galiana-Arnoux D, Dostert C, Schneemann A, Hoffmann JA, Imler JL. Essential function in vivo for Dicer-2 in host defense against RNA viruses in drosophila. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(6):590–597. doi: 10.1038/ni1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu X, Jiang F, Kalidas S, Smith D, Liu Q. Dicer-2 and R2D2 coordinately bind siRNA to promote assembly of the siRISC complexes. RNA. 2006;12(8):1514–1520. doi: 10.1261/rna.101606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Rij RP, Saleh MC, Berry B, Foo C, Houk A, Antoniewski C, Andino R. The RNA silencing endonuclease Argonaute 2 mediates specific antiviral immunity in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 2006;20(21):2985–2995. doi: 10.1101/gad.1482006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell CL, Black WC, 4th, Hess AM, Foy BD. Comparative genomics of small RNA regulatory pathway components in vector mosquitoes. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:425. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(2):94–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adelman ZN, Blair CD, Carlson JO, Beaty BJ, Olson KE. Sindbis virus-induced silencing of dengue viruses in mosquitoes. Insect Mol Biol. 2001;10(3):265–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2001.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25•.Scott JC, Brackney DE, Campbell CL, et al. Comparison of dengue virus type 2-specific small RNAs from RNA interference-competent and -incompetent mosquito cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(10):e848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000848. This paper examines the biogenesis of siRNAs in highly DENV competent C6/36 (Ae. albopictus) cells and in less competent Aag2 (Ae. aegypti) cells. The study reveals that C6/36 cells have a defective RNAi pathway. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Vargas I, Scott JC, Poole BK, et al. Dengue virus type 2 infections of Aedes aegypti are modulated by the mosquito’s RNA interference pathway. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5:e1000299. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27•.Schnettler E, Sterken MG, Leung JY, et al. Noncoding flavivirus RNA displays RNA interference suppressor activity in insect and Mammalian cells. J Virol. 2012;86(24):13486–13500. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01104-12. This paper describes the presence of a 3’UTR-derived subgenomic RNA in the genome of flaviviruses, which efficiently suppresses RNAi in mammalian and insect cells by blocking dicer activity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoo CCH, Doty JB, Heersink MS, Olson KE, Franz AWE. Transgene-mediated suppression of the RNA interference pathway in Aedes aegypti interferes with gene silencing and enhances Sindbis virus and dengue virus type 2 replication. Insect Molecular Biology. 2013;22(1):104–114. doi: 10.1111/imb.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valanne S, Wang JH, Rämet M. The Drosophila Toll signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2011;186(2):649–656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xi Z, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Aedes aegypti toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(7):e1000098. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31•.Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Toll immune signaling pathway control conserved anti-dengue defenses across diverse Ae. aegypti strains and against multiple dengue virus serotypes. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34(6):625–629. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.01.006. This study shows that the Toll pathway is active in various Ae. aegypti strains against different DENV serotypes at early stages of infection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arbouzova NI, Zeidler MP. JAK/STAT signalling in Drosophila: insights into conserved regulatory and cellular functions. Development. 2006;133(14):2605–2616. doi: 10.1242/dev.02411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Souza-Neto JA, Sim S, Dimopoulos G. An evolutionary conserved function of the JAK-STAT pathway in anti-dengue defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(42):17841–17846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905006106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bryant B, Blair CD, Olson KE, Clem RJ. Annotation and expression profiling of apoptosis-related genes in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38(3):331–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devore C. DNR1 Regulates apoptosis: new insights into mosquito apoptosis. MS thesis. 2009 http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/11972.

- 36•.Liu Q, Clem RJ. Defining the core apoptosis pathway in the mosquito disease vector Aedes aegypti: the roles of iap1, ark, dronc, and effector caspases. Apoptosis. 2011;16(2):105–113. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0558-9. This study represents the first functional examination of the core apoptosis pathway in Ae. aegypti cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Clem RJ. The role of IAP antagonist proteins in the core apoptosis pathway of the mosquito disease vector Aedes aegypti. Apoptosis. 2011;16(3):235–248. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0575-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Neill K. The role of apoptotic factors in Sindbis virus infection and replication in the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti. PhD dissertation. 2013 http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/15378.

- 39.Jasinskiene N, Coates CJ, Benedict MQ, et al. Stable transformation of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, with the Hermes element from the housefly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(7):3743–3747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Brochta DA, Sethuraman N, Wilson R, et al. Gene vector and transposable element behavior in mosquitoes. J Exp Biol. 2003;206(Pt 21):3823–3834. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson R, Orsetti J, Klocko AD, et al. Post-integration behavior of a Mos1 mariner gene vector in Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33(9):853–863. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42•.Labbé GM, Nimmo DD, Alphey L. Piggybac- and PhiC31-mediated genetic transformation of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus (Skuse) PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(8):e788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000788. This is the first report describing the successful germline transformation of Ae. albopictus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43•.Fu G, Lees RS, Nimmo D, et al. Female-specific flightless phenotype for mosquito control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(10):4550–4554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000251107. This paper describes conditional, repressible expression of a female-specific deleterious gene in Ae. aegypti, which results in phenotypes that are unable to fly (and therefore to mate). Flightlessness is induced when tetracycline is removed from the diet. These mosquitoes are promising candidates for the RIDL-based population reduction strategy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carballar-Lejarazú R, Jasinskiene N, James AA. Exogenous gypsy insulator sequences modulate transgene expression in the malaria vector mosquito, Anopheles stephensi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(18):7176–7181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304722110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nimmo DD, Alphey L, Meredith JM, Eggleston P. High efficiency site-specific genetic engineering of the mosquito genome. Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15(2):129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00615.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46•.Franz AWE, Jasinskiene N, Sanchez-Vargas I, et al. Comparison of transgene expression in Aedes aegypti generated by mariner Mos1 transposition and ΦC31 site-directed recombination. Insect Mol Biol. 2011;20(5):587–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2011.01089.x. This paper shows applicability and efficiency of the ΦC31 site-specific integration system for gene-of-interest expression in Ae. aegypti. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47•.Kokoza VA, Raikhel AS. Targeted gene expression in the transgenic Aedes aegypti using the binary Gal4-UAS system. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;41(8):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.04.004. This is the first report of using the UAS-Gal4 binary expression system in Ae. aegypti. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kulkarni MM, Arnosti DN. Information display by transcriptional enhancers. Development. 2003;130(26):6569–6575. doi: 10.1242/dev.00890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreira LA, Edwards MJ, Adhami F, et al. Robust gut-specific gene expression in transgenic Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(20):10895–10898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edwards MJ, Moskalyk LA, Donelly-Doman M, et al. Characterization of a carboxypeptidase A gene from the mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9(1):33–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kokoza VA, Martin D, Mienaltowski MJ, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the mosquito vitellogenin gene via a blood meal-triggered cascade. Gene. 2001;274(1–2):47–65. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52•.Mathur G, Sanchez-Vargas I, Alvarez D, et al. Transgene-mediated suppression of dengue viruses in the salivary glands of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol Biol. 2010;19(6):753–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01032.x. This is the first report of salivary gland-specific anti-pathogen effector gene expression in transgenic Ae. aegypti. 30K is a novel promoter driving gene expression in the distal lateral lobes of the salivary glands. Expression of an inverted-repeat effector targeting dengue virus significantly reduced virus titers in this tissue and eliminated the virus from mosquito saliva. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53•.Anderson MA, Gross TL, Myles KM, Adelman ZN. Validation of novel promoter sequences derived from two endogenous ubiquitin genes in transgenic Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol Biol. 2010;19(4):441–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01005.x. In this paper two novel constitutive promoters from Ae. aegypti are described. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54•.Carpenetti TL, Aryan A, Myles KM, Adelman ZN. Robust heat-inducible gene expression by two endogenous hsp70-derived promoters in transgenic Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol Biol. 2012;21(1):97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2011.01116.x. This paper describes the analysis of heat-shock inducible Ae. aegypti promoters for gene-of-interest expression in transgenic mosquitoes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adelman ZN, Jasinskiene N, Onal S, et al. Nanos gene control DNA mediates developmentally regulated transposition in the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(24):9970–9975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701515104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith RC, Walter MF, Hice RH, O’Brochta DA, Atkinson PW. Testis-specific expression of the beta2 tubulin promoter of Aedes aegypti and its application as a genetic sex-separation marker. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16(1):61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jasin M. Genetic manipulation of genomes with rarecutting. endonucleases Trends Genet. 1996;12:224–228. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bibikova M, Golic M, Golic KG, Carroll D. Targeted chromosomal cleavage and mutagenesis in Drosophila using zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics. 2002;161(3):1169–1175. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lloyd A, Plaisier CL, Carroll D, Drews GN. Targeted mutagenesis using zinc-finger nucleases in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(6):2232–2237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409339102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doyon Y, McCammon JM, Miller JC, et al. Heritable targeted gene disruption in zebrafish using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(6):702–708. doi: 10.1038/nbt1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(12):e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li T, Liu B, Spalding MH, Weeks DP, Yang B. High-efficiency TALEN-based gene editing produces disease-resistant rice. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(5):390–392. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu J, Li C, Yu Z, et al. Efficient and specific modifications of the Drosophila genome by means of an easy TALEN strategy. J Genet Genomics. 2012;39(5):209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moore FE, Reyon D, Sander JD, et al. Improved somatic mutagenesis in zebrafish using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Traver BE, Anderson MA, Adelman ZN. Homing endonucleases catalyze double-stranded DNA breaks and somatic transgene excision in Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol Biol. 2009;18(5):623–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66•.Aryan A, Anderson MA, Myles KM, Adelman ZN. Germline excision of transgenes in Aedes aegypti by homing endonucleases. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1603. doi: 10.1038/srep01603. This is the first report showing that HEG are functional in the germline of Ae. aegypti, leading to excision of a reporter gene from the mosquito genome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67•.Aryan A, Anderson MA, Myles KM, Adelman ZN. TALEN-based gene disruption in the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e60082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060082. This is the first report showing the use of TALEN to disrupt an endogenous gene in Ae. aegypti. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68•.DeGennaro M, McBride CS, Seeholzer L, et al. orco mutant mosquitoes lose strong preference for humans and are not repelled by volatile DEET. Nature. 2013;498(7455):487–491. doi: 10.1038/nature12206. This is the first report showing the use of zinc finger nucleases to disrupt an endogenous gene in Ae. aegypti. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bian G, Shin SW, Cheon HM, Kokoza V, Raikhel AS. Transgenic alteration of Toll immune pathway in the female mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(38):13568–13573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502815102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70•.Khoo CC, Piper J, Sanchez-Vargas I, Olson KE, Franz AW. The RNA interference pathway affects midgut infection- and escape barriers for Sindbis virus in Aedes aegypti. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-130. This paper describes transgene-mediated temporal and tissue-specific knockdown of dcr2 in Ae. aegypti. SINV titers and infection rates were significantly increased in the RNAi-impaired mosquitoes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gould F. Broadening the application of evolutionarily based genetic pest management. Evolution. 2008;62(2):500–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009;139(7):1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bian G, Zhou G, Lu P, Xi Z. Replacing a native Wolbachia with a novel strain results in an increase in endosymbiont load and resistance to dengue virus in a mosquito vector. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(6):e2250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hertig M, Wolbach SB. Studies on Rickettsia-Like Micro-Organisms in Insects. J Med Res. 1924;44(3):329–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Turley AP, Zalucki MP, O’Neill SL, McGraw EA. Transinfected Wolbachia have minimal effects on male reproductive success in Aedes aegypti. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McMeniman CJ, Lane RV, Cass BN, et al. Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science. 2009;323(5910):141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.1165326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77•.Walker T, Johnson PH, Moreira LA, et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature. 2011;476(7361):450–453. doi: 10.1038/nature10355. This paper describes the successful trans-infection of Ae. aegypti with the avirulent wMel Wolbachia strain, which then was able to further invade Ae. aegypti populations and to block dengue virus transmission. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pan X, Zhou G, Wu J, et al. Wolbachia induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent activation of the Toll pathway to control dengue virus in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(1):23–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116932108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rancès E, Ye YH, Woolfit M, McGraw EA, O’Neill SL. The relative importance of innate immune priming in Wolbachia-mediated dengue interference. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(2):e1002548. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kokoza V, Ahmed A, Woon Shin S, et al. Blocking of Plasmodium transmission by cooperative action of Cecropin A and Defensin A in transgenic Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(18):8111–8116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003056107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rancès E, Johnson TK, Popovici J, et al. The Toll and Imd pathways are not required for Wolbachia mediated dengue virus interference. J Virol. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01522-13. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Osborne SE, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Brownlie JC, O’Neill SL, Johnson KN. Antiviral protection and the importance of Wolbachia density and tissue tropism in Drosophila simulans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(19):6922–6929. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01727-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83•.Hoffmann AA, Montgomery BL, Popovici J, et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 2011;476(7361):454–457. doi: 10.1038/nature10356. This article describes the first field trial release of Ae. aegypti, which had been trans-infected with Wolbachia. The work shows that Wolbachia is capable of driving itself into naïve Ae. agypti populations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84•.Black WC, 4th, Alphey L, James AA. Why RIDL is not SIT. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27(8):362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.04.004. This review article explains the concept of RIDL as a female-killing control strategy and highlights the differences between RIDL and classical SIT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thomas DD, Donnelly CA, Wood RJ, Alphey LS. Insect population control using a dominant, repressible, lethal genetic system. Science. 2000;287(5462):2474–2476. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86•.Wise de Valdez MR, Nimmo D, Betz J, et al. Genetic elimination of dengue vector mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(12):4772–4775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019295108. This paper shows the efficacy of RIDL to eliminate Ae. aegypti populations in large cage trials. Introduction of transgenic RIDL bearing mosquitoes into populations of genetically diverse laboratory strain mosquitoes caused the collapse of the cage populations within 10–20 weeks. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Curtis CF, Graves PM. Methods for replacement of malaria vector populations. J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;91(2):43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.James AA. Gene drive systems in mosquitoes: rules of the road. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21(2):64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Beeman RW, Friesen KS, Denell RE. Maternal-effect selfish genes in flour beetles. Science. 1992;256(5053):89–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1566060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wade MJ, Beeman RW. The population dynamics of maternal-effect selfish genes. Genetics. 1994;138(4):1309–1314. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.4.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen CH, Huang H, Ward CM, et al. A synthetic maternal-effect selfish genetic element drives population replacement in Drosophila. Science. 2007;316(5824):597–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1138595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92•.Hay BA, Chen CH, Ward CM, et al. Engineering the genomes of wild insect populations: challenges, and opportunities provided by synthetic Medea selfish genetic elements. J Insect Physiol. 2010;56(10):1402–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.05.022. This review article describes the design and efficiency of Medea-based selfish genetic elements, which represent potent gene drivers for population replacement strategies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Franz AWE, Sanchez-Vargas I, Adelman ZN, et al. Engineering RNAi-based transgenic resistance against dengue virus type 2 in Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(11):4198–4203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600479103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Franz AWE, Sanchez-Vargas I, Piper J, et al. Stability and loss of a virus resistance phenotype over time in transgenic mosquitoes harboring an antiviral effector gene. Insect Mol Biol. 2009;18(5):661–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95•.Robert MA, Okamoto K, Lloyd AL, Gould F. A reduce and replace strategy for suppressing vector-borne diseases: insights from a deterministic model. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073233. This article presents mathematical models, which support the conclusion that combining population replacement with population reduction, i.e., linking an anti-DENV effector construct to the RIDL transgene, would result in much greater reduction of DENV competent vectors than RIDL alone. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]