Abstract

Decay accelerating factor (DAF/CD55) is targeted by many pathogens for cell entry. It has been implicated as a co-receptor for hantaviruses. To examine the binding of hantaviruses to DAF, we describe the use of Protein G beads for binding human IgG Fc domain-functionalized DAF ((DAF)2-Fc). When mixed with Protein G beads the resulting DAF beads can be used as a generalizable platform for measuring kinetic and equilibrium binding constants of DAF binding targets. The hantavirus interaction has high affinity (24–30 nM; kon ~ 105 M−1s−1, koff ~ 0.0045 s−1). The bivalent (DAF)2-Fc/SNV data agree with hantavirus binding to DAF expressed on Tanoue B cells (Kd = 14.0 nM). Monovalent affinity interaction between SNV and recombinant DAF of 58.0 nM is determined from competition binding. This study serves a dual purpose of presenting a convenient and quantitative approach of measuring binding affinities between DAF and the many cognate viral and bacterial ligands and providing new data on the binding constant of DAF and Sin Nombre hantavirus. Knowledge of the equilibrium binding constant allows for the determination of the relative fractions of bound and free virus particles in cell entry assays. This is important for drug discovery assays for cell entry inhibitors.

Keywords: DAF/CD55, hantavirus, co-receptor, kinetics, equilibrium binding, flow cytometry

1. Introduction

Virus entry and productive infection generally require the expression of specific cell-surface receptor molecules on target cells. Receptors can efficiently target viruses for endocytosis or may be used to activate specific signaling pathways that facilitate entry. Decay-accelerating factor (DAF/CD55) has been implicated in many cases of multi-receptor tropism amongst the enteroviruses [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], and other microbial proteins [14]. Thus, extensive structural and biochemical studies of DAF interactions with various serotypes of Enteroviruses (EV) and Group B Coxsackieviruses (CVB) have presented mechanistic insights into how DAF functions as a co-receptor for enteroviruses [8,9,10,11,12].

More recently, DAF has been identified as co-receptor of pathogenic hantaviruses: Hantaan virus (HTNV), Puumala virus (PUUV) [15,16] and Sin Nombre virus (SNV) [17]. αVβ3 integrin is generally known as the primary endocytic receptor for pathogenic hantaviruses which include: HTNV, Seoul virus (SEOV), PUUV, SNV, and New York-1 virus (NYV) [18]. Pathogenic hantaviruses cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS), with case fatality rates for HCPS generally ranging from 30%–50%. This study is primarily focused on SNV, which was first isolated in the Southwestern region of the U.S. and carried by the deer mouse Peromyscus maniculatus. It is the primary causative agent of HCPS in North America [19,20,21,22].

To the best of our knowledge the interactions of hantaviruses and DAF have been limited to few functional (infection) assays in the literature [15,16,17,23]. In this study we measure equilibrium and kinetic binding constants of killed SNV to purified IgG Fc domain-functionalized DAF ((DAF)2-Fc) proteins immobilized on protein G beads. This paper serves a dual purpose of presenting a convenient and quantitative approach of measuring binding affinities between DAF and the many cognate viral and bacterial ligands, and providing new data on the binding constant of DAF and Sin Nombre hantavirus (Figure 1). Knowledge of the equilibrium binding constant allows for the determination of the relative fractions of bound and free virus particles in cell entry assays [24]. This is important for drug discovery assays for cell entry inhibitors. In vivo, ligand-receptor interactions are mostly governed by non-equilibrium conditions [25] unless the characteristic time to equilibrium is fast, <1 s [26,27]. In this way kinetic measurements can be used to gain mechanistic insights into how viruses interact with cognate receptors, and make it possible to make useful comparisons with other receptor-ligand interactions. The equilibrium and kinetic measurements of killed SNV with DAF on beads are shown to provide a reasonable model for understanding and inhibiting productive infection.

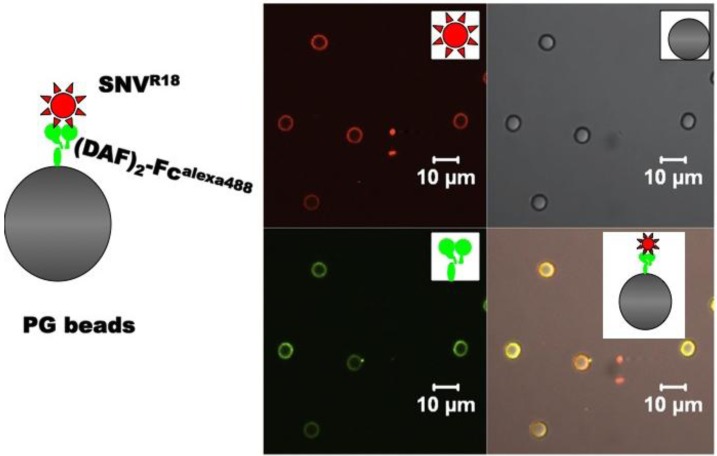

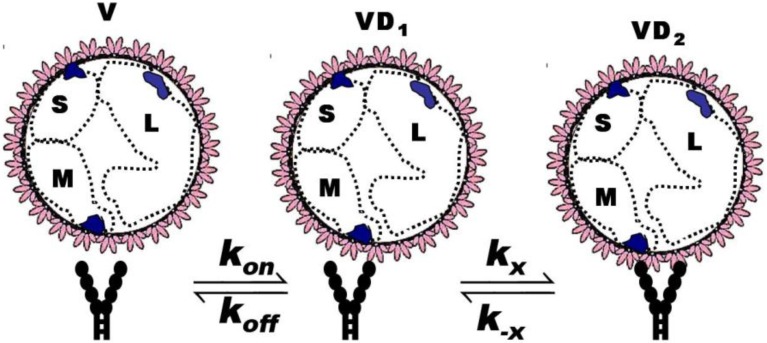

Figure 1.

Schematic of the molecular assembly of Alexa 488 labeled, IgG Fc domain-functionalized DAF (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 and octadecyl rhodamine B (R18)-labeled SNV (SNVR18) on Protein G beads and confocal microscopy images of the components. (DAF)2-Fc is immobilized on protein G (Kd = 12 nM) and then used to capture and display fluorescently labeled UV killed SNV.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Assembly of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 on Beads: Equilibrium and Kinetic Parameters

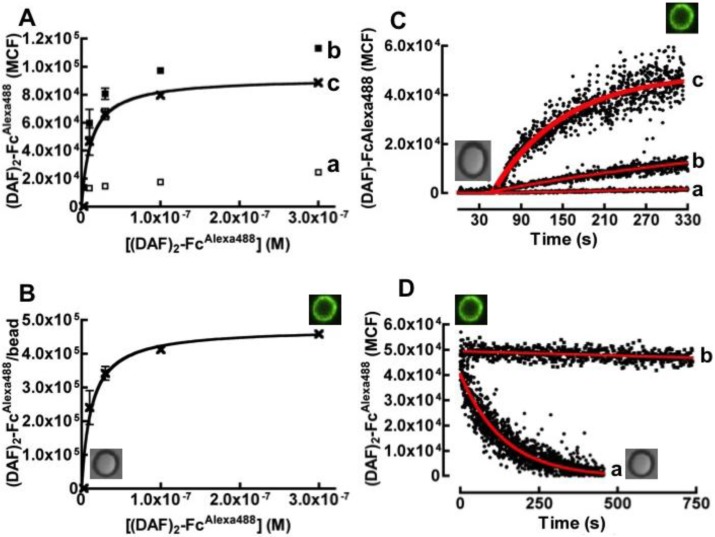

Binding of fluorescently labeled (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 to protein G beads was measured by incubating a variety of concentrations of the fluorescent probe with fixed aliquots of beads and analyzing the samples on a flow cytometer. Figure 2A shows hyperbolic plots of median channel fluorescence (MCF) of bead bead-borne (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 versus initial concentration of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488. The three curves represent non-specific binding to streptavidin-coated beads (a in Figure 2A), and total binding to Protein G beads (b in Figure 2A) and specific binding to Protein G beads (c in Figure 2A). Specific binding was calculated as the difference between total and non-specific binding curves. The data show that non‑specific binding to naked streptavidin-coated protein G beads was minimal over the concentration range of our experiments. Figure 2B shows a hyperbolic plot of various (DAF)2-FcAlexa488/bead site occupancies versus their initial concentration of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488. Analysis of the binding curve yielded an affinity constant of 12.0 nM. The maximum effective site occupancy of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 was determined to be ~225,000 sites/bead.

Figure 2.

Equilibrium binding analysis of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 to protein G beads. (A) Plot of bound (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 versus concentration of soluble (DAF)2-FcAlexa488. (a) Non-specific binding of various titers of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 were mixed with 10,000 streptavidin coated beads in 20 µL, (b) Total binding and (c) Specific binding of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 to 10,000 protein G beads. (B) Hyperbolic plot of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 molecules/protein G bead versus concentration of soluble (DAF)2-FcAlexa488. The site occupancies were determined using Mean Equivalent of Soluble Fluorophores (MESF) standard calibration beads as described in the Experimental Section. The data were fit to simple Langmuirian binding curve to yield a Kd of 12 nM. (C) Kinetic analysis of binding of: (a) 2.43 × 10−1° M, (b) 2.43 × 10−9 M, and (c) 2.43 × 10−8 M of fluorescently labeled (DAF)2-Fc to 40,000 beads in 400 µL by flow cytometry. The increase in bead-associated fluorescence over time was analyzed by the kinetic method of initial rates [30] to yield the following rate constants: (a) 6.90 × 105 M−1s−1 (b) 5.16 × 105 M−1s−1 (c) 6.71 × 105 M−1s−1. (D) Dissociations of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 from beads. (a) Dissociation kinetics induced by competition with a large excess of soluble Protein G added to molecular assembly. The data were fit to a single exponential decay curve to yield koff = 0.007 s−1. (b) The molecular assembly is relatively stable in the absence of a competitor. The square inserts are photographs of non-fluorescent and fluorescent beads or cells under different experimental conditions.

Figure 2C shows an overlay of bead binding time course of different concentrations of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 to 40,000 beads in 400 µL samples. We used the site-occupancy data to establish a simple bimolecular kinetic model, describing the interaction between protein G sites and the Fc domain of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 to fit the data and solve for the binding rate constant (kon). The analysis yielded an average binding rate constant of kon = (6.2 ± 0.8) × 105 M−1 s−1, where the error is the standard deviation of three separate measurements. Figure 2D shows single exponential fit to a dissociation curve generated by a large excess (1000 × Kd) of soluble Protein G added to the molecular assembly; koff = (7.0 ± 0.3) × 10−3 s−1. In the absence of a competitor (curve b in Figure 2D), this molecular assembly was robust due to facile rebinding of the ligand [28] and remained wholly stable for days, allowing for the long-term storage of Protein G/DAF bead stocks. This affinity constant derived from kinetic data (Kd = koff/kon = 11.3 nM) was compatible with the equilibrium binding result. Collectively, these binding parameters are comparable to kinetic and equilibrium constants of Protein G interactions with antibody Fc domains [29].

In summary, we have developed a generalizable molecular assembly platform for studying interactions between DAF and its ligands (cf. Figure 1). Because DAF is a molecular target of many viral and bacterial pathogens, the approach described herein, has the potential to be applicable to a wide range of systems. The bead platform involves non-covalent immobilization of (DAF)2-Fc on beads in a relatively simple process governed by mass action, e.g., simple mixing of Protein G beads with (DAF)2-Fc reaches equilibrium within minutes (Equation (1)) [27]:

| (teq = 3.5/(kon[(DAF)2-Fc] + koff)) | (1) |

As an illustrative example, the equilibration times (calculated from Equation (1)) for incubating (DAF)2-Fc with Protein G beads using the same concentration of soluble (DAF)2-Fc, as that used in Figure 2C are: (a) ~8 min; (b) ~7 min; (c) ~3 min.

2.2. Binding between DAF and SNV on Beads and Tanoue B Cells Is Governed by Comparable Equilibrium Dissociation Constants

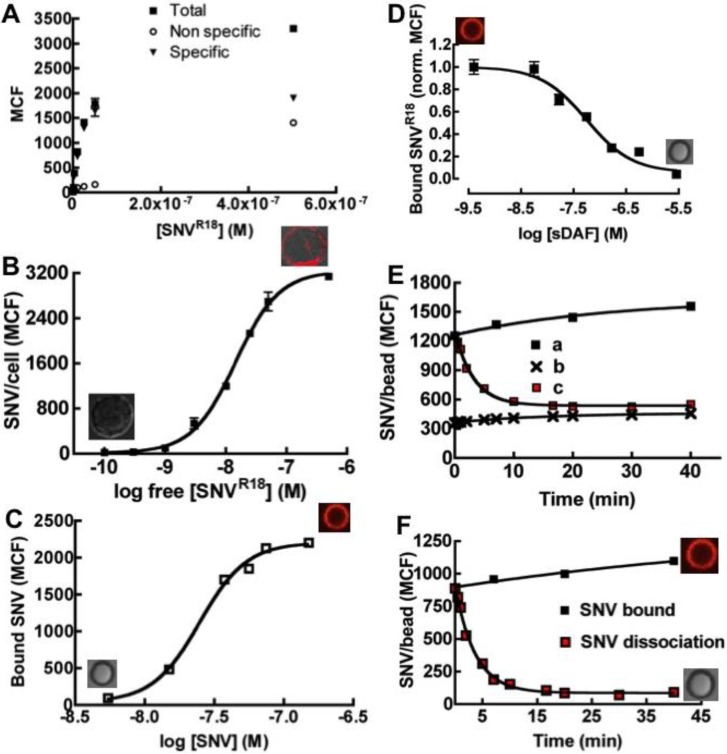

Tanoue B-suspension cells express DAF but not the entry receptor integrin αvβ3 (Table 1). These cells are suitable substrates for studying sole DAF/SNV interactions separately from αvβ3. We therefore examined the equilibrium binding characteristics of SNVR18 to DAF-bearing beads in comparison to DAF-expressing Tanoue B cells. While we have previously analyzed the binding of SNVR18 to Tanoue B cells, we recapitulate those measurements herein because the earlier study reported an anomalously low dissociation constant, Kd of 26 pM [17] for this interaction, because that study failed to accurately assess the valency of free virus particles (562 Gn-Gc heterodimers on SNV, see Methods). The binding of SNVR18 titers was plotted as a hyperbolic graph in Figure 3A. The data were corrected for non-specific binding and were then replotted as log-transformed sigmoidal dose response-curves of median channel fluorescence intensity of bound SNVR18 versus the concentration of SNVR18 particles in solution (Figure 3B). The result of a fit, Kd = 14.6 nM, was closely correlated to the (DAF)2-Fc on beads which yielded an effective affinity constant of 24.7 nM (Figure 3C). This suggested that the mode of SNVR18 binding to cell-expressed DAF and (DAF)2-Fc beads was comparable. The monovalent affinity of sDAF to SNVR18 was determined from competitive binding experiments between soluble recombinant DAF (sDAF) and (DAF)2-Fc. The inhibitor constant, Ki, was determined from the competition binding curve (Figure 3D) using the equation of Cheng and Prusoff [31] embedded in Graphpad Prism software [32]. The analysis yielded a Ki value of 58.0 nM. We next measured the dissociation rate of SNV from DAF on beads by using unlabeled SNV as a competitor. Fluorescently tagged SNVR18 immobilized on (DAF)2-Fc beads was competed off the beads with a ten-fold excess of unlabeled SNV which was added to the sample. Intensity readings were taken at various time intervals for over 40 minutes. The loss of intensity (c in Figure 3E) was plotted together with the total binding (a in Figure 3E) and non-specific binding (b in Figure 3E) over the time course. The dissociation curve was fit to a single exponential decay, which yielded a dissociation rate constant of 0.27 min−1 or 0.0045 s−1.

Table 1.

Total Receptor surface distribution of DAF and αvβ3 at Vero-E6, and Tanoue B cells surfaces.

| Cell | DAF a | Total αvβ3 b |

|---|---|---|

| Vero E6 | 5.85 ± 1.37 × 103 i | 1.61 ± 0.38 × 106 |

| 2.54 ± 0.84 × 105 ii | ||

| 2.26 ± 0.28 × 105 iii | ||

| Tanoue B | 9.29 ± 2.18 × 104 i | None detected |

Median channel fluorescence (MCF) from flow cytometry histograms was used to determine the receptor expression using MESF calibration beads (see Experimental methods). The same secondary antibody was used for all measurements. IgG1 and IgG 2a K isotype controls were used as appropriate isotype controls. (a) Several primary antibodies were used because of concerns about poor cross-species reactivity between the commercially available anti anti-human DAF clone BRIC 216 and DAF expressed on green monkey (Vero E6) cells. The results from the different clones are listed: (i) clone BRIC 216 (Millipore) (ii) IA10 (iii) 2H6 ascites. (b) Anti-Integrin αvβ3 antibody, clone 23C6, was used as primary antibody. Secondary antibody was an Alexa488 tagged goat anti anti-mouse. Adherent cells (Vero E6) were detached with Accutase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), blocked with 10% human serum for 1 h, and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C on a rotator for 2 h. Secondary antibodies were incubated at 4 °C on a rotator for 1 h. The cells were washed once and then analyzed with an Accuri C6 flow cytometer. Non-specific binding by secondary antibodies was determined by staining cells in the absence of primary antibodies.

Figure 3.

Binding of SNVR18 to Tanoue B cells and DAF beads. (A) Equilibrium binding of SNVR18 to 10,000 Tanoue B cells in 10 µL. A plot of median channel fluorescence (MCF) of cells incubated with SNVR18 (Non-specific, Total and Specific) versus the concentrations of SNVR18 added. (B) The specific data from (A) recast with log free [SNVR18] on the x-axis. This gives a sigmoid curve, with Kd = 14.0 nM. (C) Equilibrium specific binding of SNVR18 to DAF beads yielding a Kd ~ 24 nM. (D) Competition binding curve using a fixed quantity of SNVR18 and various concentrations of soluble DAF (sDAF), giving a Ki = 58.0 nM. (E) Dissociation of bound SNVR18 from DAF beads, induced by 10-fold excess of unlabeled SNV. (a) Total binding of SNVR18 to (DAF)2-Fc beads, no additions. (b) Non-specific binding to Protein G beads. (c) Addition of 10-fold excess of SNV to SNVR18-bearing DAF beads induces dissociation of SNVR18. (F) Baseline corrected dissociation of SNVR18 from DAF beads. The data was fit to a single exponential decay, yielding koff = 0.0045 s−1.

Kinetic Binding Analysis

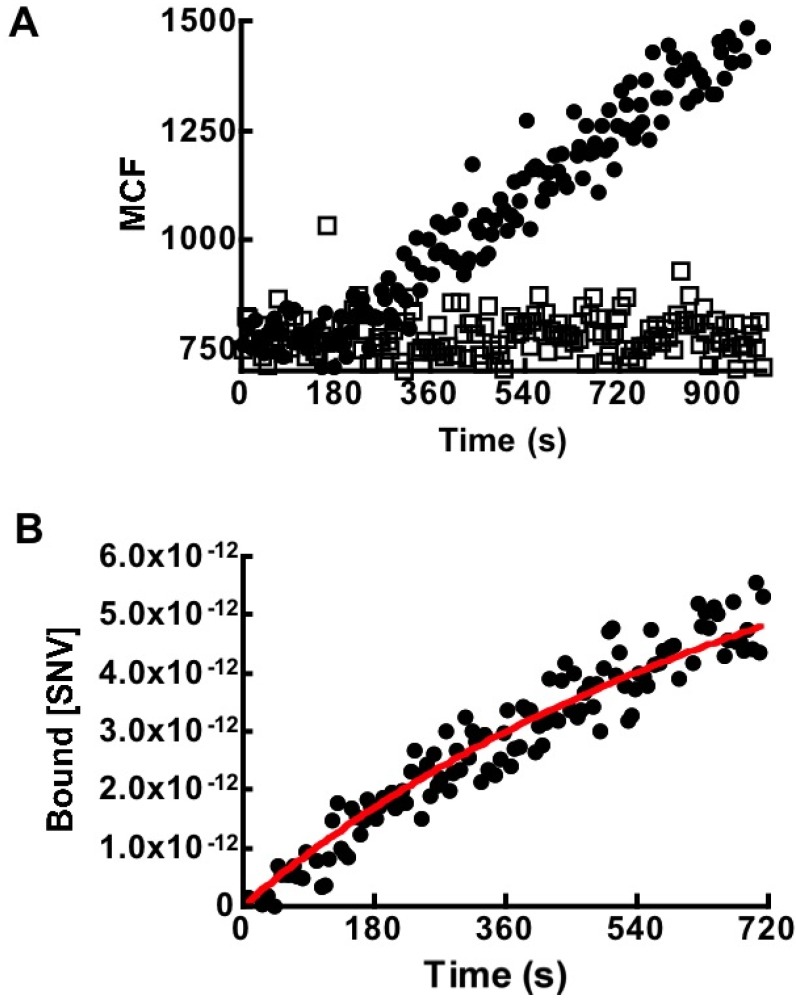

Real time binding time courses of 10, 20, and 30 µL aliquots of 108/µL SNVR18 particles to 40,000 (DAF)2-Fc beads in 400 µL HHB buffer were analyzed on a flow cytometer. Figure 4A shows an overlay of 30 × 108 SNVR18 particles binding to (DAF)2-Fc beads (a in Figure 4A) and Protein G beads (b in Figure 4A). The non-specific binding of SNVR18 to Protein G beads was subtracted from the total binding to (DAF)2-Fc beads.

Figure 4.

(A) Kinetic analysis of binding of 4 pM virus to 40,000 Protein G beads ± (DAF)2-Fc in 400 µL by flow cytometry. Association with naked protein G beads shows negligible non-specific binding between viral particles and beads. (B) Kinetic modeling (Equation (5)) of SNVR18 binding data. The average results and standard deviation for three different experimental curves were kon = (6.05 ± 0.45) × 104 M−1s−1 when koff’ was fixed at 0.0045 s−1, as derived from Figure 5F.

The typical data were averaged over 10-second time bins to reduce the noise and then fit to the model given in Equations (4) and (5). The median channel fluorescence (MCF) associated with SNVR18 was then converted to surface occupancy of SNVR18/bead using lipobead calibration standards as described in the Experimental section. The data were then converted to concentration units as previously described [27]. The dissociation rate constant for SNVR18/DAF, which we determined from experiment (koff = 0.0045 s−1; Figure 3F) was used as a fixed parameter in the kinetic model; Equation (5). This allowed the simplification of the kinetic analysis of the kinetic data to a single parameter (kon) fit employing least-squares minimization between Equation (5) and experimental data. The result yielded an average binding rate constant of kon = (1.5 ± 0.5) × 105 M−1s−1, where the errors are the standard deviations for three experimental runs using different [SNVR18]0. Thus, the Kd = 30.0 nM derived from the ratio of koff/kon—(i.e., microscopic reversibility) [30] closely agrees with the 24.7 nM value which we derived from equilibrium binding measurements (Figure 3C). The results from this study suggest that SNV binds to DAF with higher affinity compared to micromolar range affinities that have been determined for some DAF binding enteroviruses [6,33,34].

2.3. Binding Parameters Derived from Bead Platform Provide a Reasonable Model for Infection Inhibition

Equilibrium binding constants of SNV to DAF allow quantitative estimates of inhibitor concentrations to be made according to Equation (2) [35]:

| θ = ([DAF]free/Kd)/(1+([DAF]free/Kd)) | (2) |

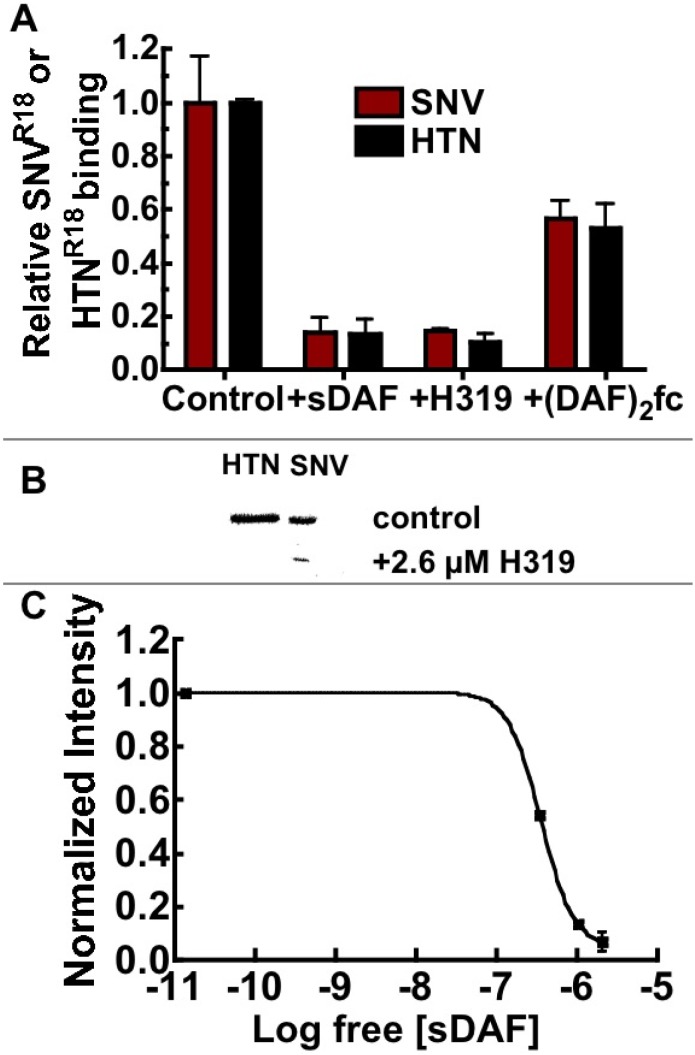

In this way, we assessed the ability of sDAF and (DAF)2-Fc to block the binding of hantavirus to Tanoue B cells expressing 100,000 DAF/cell, and lacking αvβ3 expression (Table 1). As noted in the introduction, the first description of molecular recognition of DAF by hantaviruses was associated with Hantaan (HTN) and Puumala [15]. UV killed fluorescently labeled HTN and SNV were tested in parallel in binding inhibition experiments using large excesses of sDAF (~1 µM), (DAF)2-Fc (18 µM), and 26 µM H19 anti DAF polyclonal antibody. Paired samples of 3.0 × 107 fluorescently labeled virusparticles were used in each case. The concentration of Gn-Gc heterodimers on the virus particles [36,37] was estimated to be 1.4 nM in 20 µL (see methods; Figure 7). The pre-blocked SNVR18 samples were then incubated with 10,000 Tanoue B cells in 20 µL for 30 minutes before the cells were analyzed with a flow cytometer. The results showed that sDAF, used in excess, inhibited SNVR18 binding by >90% compared to ~50% for (DAF)2-Fc (Figure 5A). The results show that excess sDAF efficiently blocks binding of virus particles when in competition with the lower concentrations of DAF expressed on Tanoue B cells (1.67 × 10−15 moles (83.5 pM)). However, the failure of two-footed (DAF)2-Fc to efficiently block binding to cells might be attributable to orientation constraints [34] relative to the tetrameric presentation of Gn and Gc structures on virus surfaces [36,37]. This idea is supported by the sDAF-comparable capacity to inhibit cell binding as monomers that were derived from papain-digestion of (DAF)2-Fc. We then compared the ability of H319 to block infection of Vero E6 by HTN and SNV. As shown for HTN and other Old World hantaviruses, elsewhere [15,16], H319 blocked infection of cells by HTN and SNV (Figure 5B).

Figure 7.

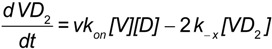

Model binding of multivalent virus (V) to bivalent (DAF)2-Fc on beads occurs in two steps (S, M, L refer to small, medium, and large RNA segments of the viral genome) [47]. First, virus particles in solution at concentration [V], each present an estimated 562 Gn-Gc spikes that, with equal probability, can bind to free bead-borne (DAF)2-Fc sites with constants, kon and koff. Second, once singly bound, the virus-DAF complex [VD1] can form [VD2] by binding to the second DAF with rate constants kx and k−x.

Figure 5.

(A) Soluble DAF (sDAF) is significantly better than (DAF)2-Fc at blocking cell binding and entry of SNV. Flow cytometry analysis of Tanoue B cell-binding inhibition of SNVR18 or HTNR18 using 1.0 µM sDAF, 26 µM H319 polyclonal antibody against DAF and 18.0 µM (DAF)2-Fc. sDAF and H319 inhibited cellular binding of SNV and HTN by >90% compared to <50% associated with (DAF)2-Fc. (B) Western blotting of Vero E6 cells infected with HTN and SNV (control) and cells pretreated with 2.6 µM H319 anti-DAF antibody. (C) Analysis of inhibition of infection of Vero E6 cells by SNV with sDAF, measuring viral N-protein by western blot, which is presented as of a plot of normalized intensity versus concentration of sDAF. Quantitative analysis of the gel was performed using a Biorad Molecular Imager, ChemiDoc XRS+ equipped with Image Lab Software 4.1 [38].

Finally, we used increasing titers of up to 3.35 µM soluble DAF (sDAF) to inhibit infection of Vero E6. It is worth noting that the ratio of total particles to infectious virions in our preparations is 14,000:1 [17]. As infectious and non-infectious particles are equally capable of receptor occupancy, a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 0.1 applied to 150,000 cells is equivalent to 2.1 × 108 particles or 19.6 × 10−9 M Gn-Gc receptors in 100 µL. Thus, 3.35 µM sDAF is theoretically high enough to inhibit SNV from binding to cellular DAF and αvβ3 (Table 1) with which it is in competition for binding to SNV glycoproteins. In this way the sDAF inhibited infection by ≥80% at the highest concentration (Figure 5C). The infection results are comparable to the blocking of infection by old world hantaviruses with sDAF and H319 anti DAF antibodies [15,16]. In conclusion this study has established a robust platform that has the potential of measuring binding interactions of DAF and many of its ligands as noted in the introduction.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

Octadecyl rhodamine B chloride (R18), and 5-octadecanoylaminofluorescein (F18) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA) and used without further purification. 6.8 µm Protein G coated polystyrene beads were purchased from Spherotech (Libertyville, IL, USA). Recombinant DAF was purchased from R&D systems. Rabbit polyclonal H319 anti DAF antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Primary antibodies for immunostaining: CD55/DAF (1:40, Millipore Cd55 MsxHu, # CBL 511) mouse monoclonal anti‑human DAF, clones IA10, 2H6 ascites, 8A7 ascites [12], mouse monoclonal anti-integrin αvβ3 (1:40, Millipore MsxHu, # MAB 1976), Secondary antibodies: (anti-mouse IgG Alexa488, anti-mouse IgG Alexa647, anti-mouse IgG Cy5, anti-rabbit Alexa647; all from Life Science Technologies, (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Amine-reactive Alexa Fluor 488 carboxylic acid, succinimidyl ester probe was purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was purchased from Mediatech, Inc, (Herndon, VA, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and Sephadex G-50 were purchased from Sigma. TRIS (10 mM or 25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) and HHB (30 mM HEPES, 110 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl26H2O and 10 mM glucose, pH 7.4) buffer, and Hanks Balanced Saline Solution (HBSS) (0.35 g NaH2CO3, 0.049 g MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2 or 1 mM MnCl2) were prepared under sterile conditions and stored in 50 mL tubes at −20 °C.

3.2. Production of Sin Nombre Virus

SNV was propagated and titered in Vero E6 cells under strict standard operating procedures using biosafety level 3 (BSL3) facilities and practices (CDC registration number C20041018-0267) as previously described [39]. For preparation of UV-inactivated SNV, we placed 100 µL of virus stock (isolate SN77734, typically 1.5–2 × 106 focus forming units/mL) in each well of a 96-well plate and subjected the virus to UV irradiation at 254 nm for various time intervals (~5 mW/cm2) as described elsewhere [17]. We verified efficiency of virus inactivation by focus assay before removing from the BSL-3 facility.

3.3. Fluorescent Labeling of SNV

The envelope membrane of hantavirus particles was stained with the lipophilic lipid probe octadecylrhodamine (R18) and purified as previously described [17]. The typical yield of viral preparation was 1 ± 0.5 × 108 particles/µL in 300 µL tagged with ~10,000 R18 probes/particle or 2.7 mole% R18 probes in the envelope membrane of each particle of 192 nm diameter average size [17]. Samples were aliquoted and stored in 0.1% HSA HHB buffer, and used within two days of preparation and storage at 4 °C. For long-term storage, small aliquots suitable for single use were stored at −80 °C.

3.4. Cloning, Expression and Purification of (DAF)2-Fc (v2) from Nicotiana benthamiana.

The sequence encoding the short consensus repeats 1–4 of human DAF (residues 35–286; GenBank accession number P08174) was cloned upstream and in-frame of the human IgG1 hinge/Fc sequence. Both DAF and Fc sequences were codon-optimized for expression in tobacco. The Fc encoded the mutation N297➔Q (numbering according to Kabat et al. [40]), to produce a non‑glycosylated Fc protein. The DAF-Fc sequence was cloned into the pTRAkc plant expression vector [41], and then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 (pMP90RK) by electroporation. The final construct included sequences encoding a 5' signal peptide and a 3' SEKDEL peptide to facilitate accumulation in the plant’s endoplasmic reticulum.

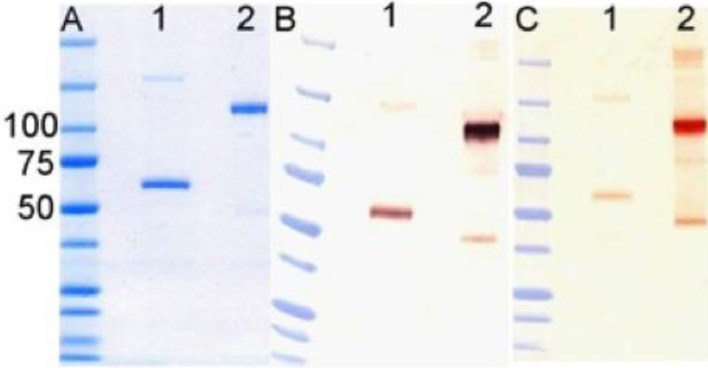

Transient expression of the fusion protein was accomplished by whole-plant vacuum infiltration [42] of Nicotiana benthamiana using the transformed A. tumefaciens strain carrying DAF-Fc, with co‑infiltration of an A. tumefaciens strain carrying the p19 silencing suppressor gene of tomato bushy stunt virus [43] to prolong and amplify expression. After infiltration, the plants were maintained in the greenhouse under standard conditions for 7 days prior to protein purification. N. benthamiana leaves were harvested, washed in ice water and blotted dry, then homogenized in a blender with extraction buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM sodium phosphate, 10 mM sodium thiosulphate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl flouride, pH 7.4). The homogenate was filtered and the filtrate centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The clarified juice was recovered and pumped over a column of Protein A-Sepharose 4B (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The column was washed with PBS and eluted with 10 mM glycine, pH 3.0. Purified protein was analyzed using standard methods. Samples were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (under reducing and non-reducing conditions) and visualized by Coomassie G250 staining, or by western blot analysis using antibodies against human IgG1 and DAF (Figure 6). Purified of (DAF)2-Fc was visualized by Coomassie G250 staining, or by western blot analysis using antibodies against human IgG1 and DAF (Figure 6). 10–20 µM samples of (DAF)2-Fc −v2 were stored in 20 µL aliquots.

Figure 6.

Analysis of purified DAF-Fc. (A) 2 µg/lane of (DAF)2-Fc (v2) was electrophoresed through SDS-polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie G250. Additional gels with 400 ng (lane 1) or 100 ng (lane 2) were blotted onto nitrocellulose ad probed with (B) anti-human IgG or (C) anti-DAF antibodies. Lane 1, is protein reduced with DTT; lane 2, non reduced protein. Molecular mass standards are indicated in kDa.

3.5. Fluorescent Labeling of (DAF)2-Fc

1.8 µM (DAF)2-Fc in 200 µL sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.3) was mixed with 20 µL of 1 mg/mL amine-reactive Alexa Fluor 488 carboxylic acid succinimidyl ester in DMSO for 30 min at room temperature. The fluorescently tagged (DAF)2-Fc was purified and concentrated by ultra filtration in phosphate buffered saline using a 30,000 NMWCO Centricon membrane. The fluorophore to protein (f/p) ratio was determined following standard procedures supplied by the manufacturer. The f/p ratio was 2.8:1. The quantum yield (ϕ) of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 was measured relative to fluorescein with absorbance matched samples using a Hitachi model U-3270 spectrophotometer (San Jose, CA, USA) and a Photon Technology International QuantaMaster model QM-4/2005 spectrofluorometer (Lawrenceville, NJ, USA).

3.6. Cell Culture

Tanoue B, and Vero E6 were maintained in minimum essential media (MEM) (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA). All media contain 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 20 mg/mL ciprofloxacin, 2 mM L-glutamine, at 37 °C in a water jacketed 5% CO2 incubator.

3.7. Confocal Microscopy Imaging

Confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed with Zeiss META or LSM 510 systems using 63 × 1.4 oil immersion objectives as previously described [44].

3.8. Cytometry Experiments

Equilibrium and kinetic binding interactions were analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously [17,45] using BD FACScan and Accuri C6 flow cytometers. Here we provide the essential elements of cytometric analyses of the binding of fluorescent ligands (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 and SNVR18 to beads and cell surface receptors. A flow cytometer was used to determine the concentration (beads/µL) of Protein G and streptavidin-coated beads in their respective stock suspensions before application. For analyses of equilibrium ligand binding, fluorescence histograms of 500–3000 beads were recorded as a function of ligand concentration at steady state. The flow cytometer’s capacity to discriminate between free and bound ligand without a wash step enables real time addition of ligands to bead suspensions where binding is manifested by exponential increase in mean/median channel fluorescence. The increase in the mean fluorescence channel number of the histogram is related to the fractional receptor occupancy of the specifically bound ligand minus the mean fluorescence channel number of beads exposed to fluorescent ligand under identical conditions but in the presence of excess non-fluorescent ligand (at a concentration of at least 1000 × Kd). To conserve scarce reagents, the use of blocking reagents at 1000 × Kd can be obviated by using beads that lack the cognate receptor, such as our use of streptavidin beads as controls for protein G beads herein.

The number of receptors per bead or cell was calibrated using a variety of calibration beads depending on spectroscopic region of interest. Commercial standards from Bangs Laboratories (Fishers, IN, USA), Quantum fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) MESF (molecules of equivalent soluble fluorescein) beads were used with the appropriate correction factor, to account for the spectroscopic differences between calibration standards and probes detected in the 515–545 nm band pass filter-delimited spectral region [36]. Thus, the correction factor (cf) appropriate for Alexa488 was calculated using Equation (3),

| cf = (εexϕ%T)Alexa488/(εexϕ%T)fluorescein = (54,750 × 0.99 × 28)/(75,680 × 1 × 28) = 0.71 | (3) |

where εex is the absorption coefficient of the fluorophore at the excitation wavelength, ϕ is the quantum yield of the target fluorophore, and %T is the percentage fraction of fluorescence light transmitted by the 530-nm, 30-nm-wide bandpass filter. Using the 488 nm laser excitation, the off-resonance excitation of the Alexa488 was at 75% of its maximum compared to fluorescein, which was excited at 88% of its absorption maximum. The quantum yield of target fluorophores were measured relative to standard solutions such as fluorescein or rhodamine as described for (DAF)2-FcAlexa above. For probes detected in spectral regions other than the 515–545 nm window covered by MESF beads, we used quantum dot calibration beads or lipobeads [27]. As reported elsewhere, the emission quantum yield of quantum dots varies among batches and manufactures, thus the cf is batch specific. Lipobeads were custom made, as described below, for calibrating virus binding to beads or cells. In our application lipobeads use the same R18 fluorophore in the same envelope-mimetic lipid environment as the virus particle [17]. Thus the cf value is 1.

3.9. Supported Bilayer Membranes on Glass Beads

Lipid coated glass beads (lipobeads) were prepared as previously described [17,27]. For the present study, lipobeads comprising either a single-component DOPC lipid bilayer membrane or a 1:1:1 ternary mixture of DOPC/sphingomyelin/cholesterol (DSC) lipid membranes doped with a variable mole fraction [27] of (e.g., 2.7 mole %) R18 were prepared for use as flow cytometry calibration standards for quantifying virus particles bound to protein G/(DAF)2-Fc beads.

3.10. Equilibrium Binding of Molecular Assembly Components (DAF)2-Fc, and SNVR18 on Protein G Beads

(DAF)2-Fc. To evaluate the equilibrium binding of (DAF)2-Fc to protein G, 10,000 beads were added into several 20 µL volume samples, and then mixed with increasing concentrations of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 ranging from ~1 nM–1 µM for an hour at room temperature. Streptavidin-coated beads were used as controls for measuring non-specific binding. After incubation, the samples were diluted to 50 µL and read on the flow cytometer. The site occupancy of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 was determined from analyzing cytometry histograms of samples measured against standard calibration beads as described above.

SNVR18. The determination of the saturable binding site density of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 on protein G beads facilitated the next step of producing the molecular assembly platform for displaying SNVR18 from incubating 760,000 Protein G beads with a 100-fold stoichiometric excess of (DAF)2-Fc for 30 min at room temperature. The molecular assembly beads were then washed once and resuspended in HHB buffer at 1000 beads/µL. Subsequently, 10 µL aliquots from this stock were incubated with increasing titers of virus particles until a plateau signifying binding saturation was reached. Competitive binding experiments were performed with a single concentration of bead-borne SNVR18 and a variety of concentrations of soluble recombinant DAF in order to generate a competitive binding curve, from which to determine the monovalent affinity of soluble DAF. The dissociation constants for the binding of the competitor were determined by examination of the fractional occupancy of SNVR18, assuming a single class of binding sites.

3.11. Cell Surface Distribution of DAF and αvβ3 Integrins

Adherent cells (Vero) were detached with accutase (Sigma), blocked with 10% human serum for 1 h, and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C on a rotator for 2 h. Secondary antibodies were incubated at 4 °C on a rotator for 1 h. The cells were washed once and then analyzed with an Accuri C6 flow cytometer. Non-specific binding by secondary antibodies was determined by staining cells with isotype controls in the absence of primary antibodies (see Table 1 notes).

3.12. Virus Binding to DAF Expressed on Tanoue B Cells

Binding assays were performed by incubating varying concentrations of SNVR18 with 10,000 Tanoue B cells in microfuge tubes gently nutating for 30 min. Specific binding to DAF expressed on Tanoue B cells was blocked with 40 µg/mL of rabbit H319 anti-DAF antibodies [17]. SNVR18 particles were also pre-incubated with sDAF and (DAF)2-Fc to evaluate their comparative capacities to inhibit binding to cellular DAF. Paired samples of fluorescently labeled SNVR18 particles were incubated with titers of sDAF and (DAF)2-Fc for one hour and then mixed with 10,000 Tanoue B cells in 50 µL for 30 minutes and then read on a flow cytometer.

3.13. Infectivity Assays

For BSL3 live virus infection assays, Vero E6 cells were infected with SNV strain SN77734 inocula (moi = 0.1) that had been preblocked with 0–3.35 µM soluble DAF (sDAF) in a final volume of 100 µL for 1hour. Unbound virus particles were removed by a triple washing, and cells were then transferred to a CO2 incubator for 24 h. The infection was monitored by a standard Western blot analysis of N-protein expression where cell lysates were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate buffer and separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. SNV N protein was detected with αSNV/N, (hyperimmune rabbit anti-SN virus N protein) [46] used at a 1:1000 dilution, with overnight incubation, washed and then probed for an hour incubation with a secondary antibody (Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti Rabbit IgG; cat# 111-035-003, lot# 104668, used at 1:1000 dilution) from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA) The nitrocellulose membrane was then treated with an HRP substrate from Pierce: SuperSignal ® West Pico (Product # 0034077) for 5 min before imaging. Quantitative analysis of the gel was performed using A Biorad Molecular Imager, ChemiDoc XRS+ equipped with Image Lab Software 4.1 [38].

3.14. Ligand Binding Kinetic Measurements

The time course of association was measured by acquiring a 60–180 s baseline of ligand-free beads before an aliquot of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488 was added with a Hamilton syringe, while data collection continued for up to 600 s. This process was repeated for different concentrations of (DAF)2-FcAlexa488. Raw data were converted to ASCII format, using software developed by Dr Bruce Edwards at UNM [17]. The dissociation rate constant was measured by adding a large excess of soluble protein G to (DAF)2-FcAlexa488-bearing Protein G beads, during a data collection time course. The same process was repeated to measure the binding kinetics of SNVR18 to (DAF)2-Fc bearing beads.

3.15. Kinetic Modeling of Virus Binding

Hantaviruses encode two glycoproteins, Gn and Gc, which are required for receptor binding. We used the structural parameters from recent studies of Tula [36] and Hantaan viruses [37] to estimate site occupancies of Gn-Gc heterodimers on 192 nm—diameter SNV virus particles used in our study [17]. Assuming a suggested upper limit of 70% surface coverage of the particle by Gn-Gc spikes [36] we estimated an average surface expression of 562 Gn-Gc heterodimers on SNV. For the purposes of our present study, this number of unique Gn-Gc sites constitutes the valency (v) of each single virus particle. Upon binding to the surface of a bead, only 2 out of the ~562 Gn-Gc heterodimers can simultaneously engage the bivalent (DAF)2-Fc receptor on the same bead, thus the effective valency of the bound SNV is limited to 2.

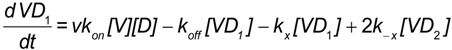

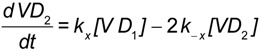

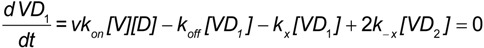

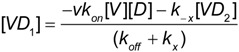

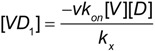

It is also possible to consider the ligation of more than one (DAF)2-Fc receptor on the bead. This might increase the valency to 2 + n (where n is the nominal value of additional DAF binding sites). Based on topographical constraints and goodness of fit of a simple model, the multi (DAF)2-Fc ligation model was not considered. The present scheme is illustrated in Figure 7 Considering a simple binding model as shown in Equation (4) [48,49,50], the following mass action rate equations were used to determine the kinetic changes to the free and bound concentration of virus particles, [V], and [VDi] i = 1,2. Here, kon and koff are the bimolecular binding and dissociation rate constants of one footed binding, whereas kx and k−x are the forward and reverse rate constants describing the cross-linking binding of the second Gn-Gc heterodimer to the free binding site of (DAF)2-Fc.

|

(4a) |

|

(4b) |

|

(4c) |

Assuming that kon << kx, the concentration of VD1 is expected to approach steady state values (see Appendix A), which allows the model to be simplified under quasi-steady state regime considerations [30]. In this way the two-footed binding of SNV to (DAF)2-Fc was reduced to a two parameter fit, where koff’ is the dissociation rate constant of SNV from (DAF)2-Fc.

|

(5) |

The experimental rate equations for the variable parameters in Equation (5) were solved numerically using the Runge-Kutta method [51] for values of reaction rate constants kon and koff’ using Berkeley Madonna Software [52].

4. Conclusions

This study has described a generalizable cell-free platform to characterize specific binding interactions between DAF and SNV. The derived equilibrium and kinetic binding constants from this study provide useful insights into future studies on the mechanism of DAF’s co-receptor role in mediating cell entry.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grants R03AI092130, R21NS066429, 1P50GM085273, UNM School of Medicine RAC award and The New Mexico State Cigarette Tax to the UNM Cancer Center. Images in this article were generated in the University of New Mexico Cancer Center Fluorescence Microscopy Facility P30CA118100-08S2 Sub-Project ID: 6322.

Appendix A

Application of the steady state approximation to the association of SNV with (DAF)2-fc beads.

From Equation (4b):

|

(A1) |

|

(A2) |

kx >> koff and kx >> k-x Equation (A2) simplifies to:

|

(A3) |

and substituting (A3) into Equation (2c) yields

|

(A4) |

Author Contributions

Buranda T, Hjelle B. Belle A. and Wycoff K. designed research; Schaefer L., Maclean J., Mo Z. and Belle A., cloned, expressed and purified and analyzed (DAF)2-Fc from Nicotiana benthamiana and wrote the method; Hjelle, B. provided SNV virology expertise; Swanson S., Bondu V. and Buranda, T. performed the binding and infection assays; Buranda, T. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- 1.Coyne C.B., Shen L., Turner J.R., Bergelson J.M. Coxsackievirus entry across epithelial tight junctions requires occludin and the small gtpases rab34 and rab5. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rezaikin A.B., Novoselov A.B., Fadeev F.A., Sergeev A.G., Lebedev S.B. Mapping of point mutations leading to loss of virus ech011 affinity for receptor daf (cd55) Vopr. Virusol. 2009;54:41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rezaikin A.V., Novoselov A.V., Sergeev A.G., Fadeyev F.A., Lebedev S.V. Two clusters of mutations map distinct receptor-binding sites of echovirus 11 for the decay-accelerating factor (cd55) and for canyon-binding receptors. Virus Res. 2009;145:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sobo K., Rubbia-Brandt L., Brown T.D., Stuart A.D., McKee T.A. Decay-accelerating factor binding determines the entry route of echovirus 11 in polarized epithelial cells. J. Virol. 2010;85:12376–12386. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00016-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selinka H.C., Wolde A., Sauter M., Kandolf R., Klingel K. Virus-receptor interactions of coxsackie b viruses and their putative influence on cardiotropism. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2004;193:127–131. doi: 10.1007/s00430-003-0193-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettigrew D.M., Williams D.T., Kerrigan D., Evans D.J., Lea S.M., Bhella D. Structural and functional insights into the interaction of echoviruses and decay-accelerating factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:5169–5177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milstone A.M., Petrella J., Sanchez M.D., Mahmud M., Whitbeck J.C., Bergelson J.M. Interaction with coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor, but not with decay-accelerating factor (daf), induces a-particle formation in a daf-binding coxsackievirus b3 isolate. J. Virol. 2005;79:655–660. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.655-660.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uhrinova S., Lin F., Ball G., Bromek K., Uhrin D., Medof M.E., Barlow P.N. Solution structure of a functionally active fragment of decay-accelerating factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:4718–4723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730844100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson K.L., Billington J., Pettigrew D., Cota E., Simpson P., Roversi P., Chen H.A., Urvil P., du Merle L., Barlow P.N., et al. An atomic resolution model for assembly, architecture, and function of the dr adhesins. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:647–657. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien D.P., Israel D.A., Krishna U., Romero-Gallo J., Nedrud J., Medof M.E., Lin F., Redline R., Lublin D.M., Nowicki B.J., et al. The role of decay-accelerating factor as a receptor for helicobacter pylori and a mediator of gastric inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13317–13323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafenstein S., Bowman V.D., Chipman P.R., Bator Kelly C.M., Lin F., Medof M.E., Rossmann M.G. Interaction of decay-accelerating factor with coxsackievirus b3. J. Virol. 2007;81:12927–12935. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00931-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuttner-Kondo L., Hourcade D.E., Anderson V.E., Muqim N., Mitchell L., Soares D.C., Barlow P.N., Medof M.E. Structure-based mapping of daf active site residues that accelerate the decay of c3 convertases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:18552–18562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coyne C.B., Bergelson J.M. Virus-induced abl and fyn kinase signals permit coxsackievirus entry through epithelial tight junctions. Cell. 2006;124:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rougeaux C., Berger C.N., Servin A.L. Hceacam1–4l downregulates hdaf-associated signalling after being recognized by the dr adhesin of diffusely adhering escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 2008;10:632–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krautkramer E., Zeier M. Hantavirus causing hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome enters from the apical surface and requires decay-accelerating factor (daf/cd55) J. Virol. 2008;82:4257–4264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02210-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popugaeva E., Witkowski P.T., Schlegel M., Ulrich R.G., Auste B., Rang A., Kruger D.H., Klempa B. Dobrava-belgrade hantavirus from germany shows receptor usage and innate immunity induction consistent with the pathogenicity of the virus in humans. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buranda T., Wu Y., Perez D., Jett S.D., Bondu-Hawkins V., Ye C., Lopez G.P., Edwards B., Hall P., Larson R.S., Sklar L.A., Hjelle B. Recognition of daf and avb3 by inactivated hantaviruses, towards the development of hts flow cytometry assays. Anal. Biochem. 2010;402:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackow E.R., Gavrilovskaya I.N. Hantavirus regulation of endothelial cell functions. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2009;102:1030–1041. doi: 10.1160/TH09-09-0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hjelle B., Anderson B., Torrez-Martinez N., Song W., Gannon W.L., Yates T.L. Prevalence and geographic genetic variation of hantaviruses of new world harvest mice (reithrodontomys): Identification of a divergent genotype from a costa rican reithrodontomys mexicanus. Virology. 1995;207:452–459. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hjelle B., Chavez-Giles F., Torrez-Martinez N., Yates T., Sarisky J., Webb J., Ascher M. Genetic identification of a novel hantavirus of the harvest mouse reithrodontomys megalotis. J. Virol. 1994;68:6751–6754. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6751-6754.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hjelle B., Jenison S.A., Goade D.E., Green W.B., Feddersen R.M., Scott A.A. Hantaviruses: Clinical, microbiologic, and epidemiologic aspects. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1995;32:469–508. doi: 10.3109/10408369509082592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonsson C.B., Schmaljohn C.S. Replication of hantaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2001;256:15–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56753-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buranda T., Basuray S., Swanson S., Bondu-Hawkins V., Agola J., Wandinger-Ness A. Rapid parallel flow cytometry assays of active gtpases using effector beads. Anal. Biochem. 2013;144:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casasnovas J.M., Springer T.A. Kinetics and thermodynamics of virus binding to receptor—Studies with rhinovirus, intercellular-adhesion molecule-1 (icam-1), and surface-plasmon resonance. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:13216–13224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X., Vilenski O., Kwan J., Apparsundaram S., Weikert R. Unbound brain concentration determines receptor occupancy: A correlation of drug concentration and brain serotonin and dopamine reuptake transporter occupancy for eighteen compounds in rats. Drug Metabol. Dispos. 2009;37:1548–1556. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.026674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motulsky H.J., Mahan L.C. The kinetics of competitive radioligand binding predicted by the law of mass action. Mol. Pharmacol. 1984;25:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buranda T., Wu Y., Perez D., Chigaev A., Sklar L.A. Real-time partitioning of octadecyl rhodamine b into bead-supported lipid bilayer membranes revealing quantitative differences in saturable binding sites in dopc and 1:1:1 dopc/sm/cholesterol membranes. J. Phys. Chem. 2010;114:1336–1349. doi: 10.1021/jp906648q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buranda T., Waller A., Wu Y., Simons P.C., Biggs S., Prossnitz E.R., Sklar L.A. Some mechanistic insights into gpcr activation from detergent-solubilized ternary complexes on beads. Adv. Protein Chem. 2007;74:95–135. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(07)74003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saha K., Bender F., Gizeli E. Comparative study of igg binding to proteins g and a: Nonequilibrium kinetic and binding constant determination with the acoustic waveguide device. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:835–842. doi: 10.1021/ac0204911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benson S.W. Foundations of Chemical Kinetics. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY, USA: 1960. p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng Y., Prusoff W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graphpad Prism. GraphPadSoftware; La Jolla, CA, USA: 2011. version 5.04. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lea S.M., Powell R.M., McKee T., Evans D.J., Brown D., Stuart D.I., van der Merwe P.A. Determination of the affinity and kinetic constants for the interaction between the human virus echovirus 11 and its cellular receptor, cd55. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30443–30447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodfellow I.G., Evans D.J., Blom A.M., Kerrigan D., Miners J.S., Morgan B.P., Spiller O.B. Inhibition of coxsackie b virus infection by soluble forms of its receptors: Binding affinities, altered particle formation, and competition with cellular receptors. J. Virol. 2005;79:12016–12024. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.12016-12024.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klasse P.J., Moore J.P. Quantitative model of antibody- and soluble cd4-mediated neutralization of primary isolates and t-cell line-adapted strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 1996;70:3668–3677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3668-3677.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huiskonen J.T., Hepojoki J., Laurinmaki P., Vaheri A., Lankinen H., Butcher S.J., Grunewald K. Electron cryotomography of tula hantavirus suggests a unique assembly paradigm for enveloped viruses. J. Virol. 2010;84:4889–4897. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00057-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Battisti A.J., Chu Y.K., Chipman P.R., Kaufmann B., Jonsson C.B., Rossmann M.G. Structural studies of hantaan virus. J. Virol. 2011;85:835–841. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01847-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Image Lab Software. Biorad; Hercules, CA, USA: 2009. version 4.1. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bharadwaj M., Lyons C.R., Wortman I.A., Hjelle B. Intramuscular inoculation of sin nombre hantavirus cdnas induces cellular and humoral immune responses in balb/c mice. Vaccine. 1999;17:2836–2843. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kabat E.A., Te Wu T., Gottesman K.S., Foeller C. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interes. Diane Books Publishing Co.; Darby, PA, USA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maclean J., Koekemoer M., Olivier A.J., Stewart D., Hitzeroth I.I., Rademacher T., Fischer R., Williamson A.L., Rybicki E.P. Optimization of human papillomavirus type 16 (hpv-16) l1 expression in plants: Comparison of the suitability of different hpv-16 l1 gene variants and different cell-compartment localization. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88:1460–1469. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82718-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kapila J., DeRycke R., VanMontagu M., Angenon G. An agrobacterium-mediated transient gene expression system for intact leaves. Plant Sci. 1997;122:101–108. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(96)04541-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voinnet O., Rivas S., Mestre P., Baulcombe D. An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J. 2003;33:949–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chigaev A., Buranda T., Dwyer D.C., Prossnitz E.R., Sklar L.A. Fret detection of cellular alpha 4-integrin conformational activation. Biophys. J. 2003;85:3951–3962. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu Y., Campos S.K., Lopez G.P., Ozbun M.A., Sklar L.A., Buranda T. The development of quantum dot calibration beads and quantitative multicolor bioassays in flow cytometry and microscopy. Anal. Biochem. 2007;364:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elgh F., Lundkvist A., Alexeyev O.A., Stenlund H., Avsic-Zupanc T., Hjelle B., Lee H.W., Smith K.J., Vainionpaa R., Wiger D., Wadell G., Juto P. Serological diagnosis of hantavirus infections by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay based on detection of immunoglobulin g and m responses to recombinant nucleocapsid proteins of five viral serotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997;35:1122–1130. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1122-1130.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaheri A., Strandin T., Hepojoki J., Sironen T., Henttonen H., Makela S., Mustonen J. Uncovering the mysteries of hantavirus infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11:539–550. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeLisi C. The biophysics of ligand-receptor interactions. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1980;13:201–230. doi: 10.1017/S0033583500001657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeLisi C., Chabay R. The influence of cell surface receptor clustering on the thermodynamics of ligand binding and the kinetics of its dissociation. Cell Biophys. 1979;1:117–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perelson A. Some mathematical models of receptor clustering by multivalent ligands. In: Perelson A., DeLisi C., Wiegel F.W., editors. Cell Surface Dynamics Concepts and Models. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1984. pp. 223–276. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Press W.H., Flannery B.P., Teakolsky S.A., Vetterling W.T. Numerical Recipes. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mace R., Oster G. Berkeley Madonna. University of California, Berkeley; Berkeley, CA, USA,: 2005. version 8.0.1. [Google Scholar]