Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence and trends of these pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women from 2005–2010.

Methods

We utilized the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2005–2006, 2007–2008, and 2009–2010. A total of 7,924 non-pregnant women (aged 20 years or older) were categorized as having: urinary incontinence – moderate to severe (3 or higher on a validated urinary incontinence (UI) severity index, range 0–12); fecal incontinence – at least monthly (solid, liquid, or mucus stool); and pelvic organ prolapse – seeing or feeling a bulge. Potential risk factors included age, race and ethnicity, parity, education, poverty income ratio, body mass index (BMI) (<25, 25–29, ≥30 kg/m2), co-morbidity count, and reproductive factors. Using appropriate sampling weights, weighted chi square analysis and multivariable logistic regression models with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported.

Results

The weighted prevalence rate of one or more pelvic floor disorder was 25.0% (95% CI 23.6, 26.3), including 17.1% (95% CI 15.8, 18.4) of women with moderate-to-severe urinary incontinence, 9.4% (95% CI 8.6, 10.2) with fecal incontinence, and 2.9% (95% CI 2.5, 3.4) with prolapse. From 2005 to 2010, no significant differences were found in the prevalence rates of any individual disorder or for all disorders combined (p>0.05). After adjusting for potential confounders, higher BMI, greater parity, and hysterectomy were associated with higher odds of one or more pelvic floor disorder.

Conclusion

Although rates of pelvic floor disorders did not change from 2005–2010, these condition remain common with one quarter of adult U.S. women reporting at least one disorder.

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic floor disorders, which include urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse, are highly prevalent conditions in women, affecting almost 25% of women in the United States.(1) The landmark study by Nygaard et al. provided the first, national, population-based estimates of the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and highlighted the significant public health burden of these conditions. Because only one year of data was available, the authors were unable to assess prevalence rate trends over time.

There are several factors that may have impacted trends in the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders. One important issue is the aging of the U.S population, as these disorders become more common with increasing age.(1) It is possible that these changing demographics have resulted in an increase in the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders. In addition, obesity is associated with these conditions,(1–3) and the obesity epidemic in the U.S. may have influenced the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders.(4) Furthermore, several studies have shown that the rates of surgical procedures for urinary incontinence (5–7) and prolapse (8–10) have increased over time. Given these factors, it is possible that the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders has changed. Lastly, an evaluation of factors associated with these disorders in a nationally representative sample will highlight potentially modifiable risk factors, which we may be able to target for prevention efforts. Thus, our objective was to estimate the overall prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women from 2005–2010 and to assess factors associated with these disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey program consists of cross-sectional, national health surveys conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm). This survey provides estimates of the health status of the U.S. population by selecting a representative sample of the non-institutionalized population using a complex, stratified, multi-stage, probability cluster design. The National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey 2005–2006 oversampled persons aged 60 years or older, and other racial/ethnic groups (Non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, and low-income Non-Hispanic White) to provide more reliable estimates for these groups. In the 2007–2008 and 2009–2010 surveys, all Hispanic groups were oversampled, not just Mexican Americans. The National Centers for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board approved the protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.(11)

Participants were interviewed in their homes and then underwent standardized physical examination, including measured height and weight, and further questioning in a mobile examination center. Trained interviewers asked questions about UI and FI among women aged 20 years and older in a private mobile examination center interview. Questions on POP were assessed with questions on the reproductive health questionnaire.

To define each pelvic floor disorder, we used similar methodology to a previous publication using National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey data from 2005–2006.(1) (Information regarding the specific questionnaires can be found at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm.) Definitions were utilized to represent more bothersome, or symptomatic pelvic floor disorders. We defined urinary incontinence using the validated 2-item incontinence severity index, which correlates well with incontinence volume based on 24-hour pad weights and incontinence frequency on bladder diaries.(1) The incontinence severity index is based on a question about frequency of episodes (<once per month, a few times a month, a few times a week, or every day and/or night) and a question about the amount of leakage (drops, splashes, or more). The responses on the two questions are multiplied to obtain a total severity score that ranges from 1 to 12 (mild or slight symptoms score 1–2, moderate symptoms 3–6, severe symptoms 7–9, and 10–12 very severe).16 For this analysis, the categories of severe and very severe symptoms were combined to define “severe incontinence.” Moderate to severe incontinence corresponds to at least weekly leakage or monthly leakage of volumes more than just drops.(1) To evaluate for the occurrence of fecal incontinence, we used the Fecal Incontinence Severity Index, which asked about the frequency of leakage of gas, mucus, liquid, and/or solid stool leakage with the following categories: “never,” “two of more times per day,” “once per day,” “two or more times per week,” “once a week,” to “one to three times per month.”(12) We defined fecal incontinence as leakage of mucus, liquid, and/or solid stool occurring at least monthly. Women were asked about prolapse using the previously validated question, “Do you see or feel a bulge in the vaginal area.”(13) We dichotomized the responses and defined prolapse as a positive response. From the responses for individual pelvic floor disorders, we created a combined disorders variable which we refer to as “≥ 1 pelvic floor disorder” that included the presence of at least one positive response for moderate-to-severe urinary incontinence, monthly fecal incontinence, or prolapse.

Women self-reported their race and ethnicity, which was then categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic (including Mexican American) and other or mixed race ethnicity. Age was categorized in 10-year increments from 20 years of age to age 79, with women aged 80 years and older in the same category. Education was categorized as at least some level of high school education (including General Education Development or equivalent) or more than high school. The poverty income ratio, an indicator of socioeconomic status that uses the ratio of income to the family’s poverty threshold set by the U.S. Census Bureau, was categorized as less than 1 (below the poverty threshold), 1 to 2 (1–2× the poverty threshold), and 2 and more (2× the poverty threshold). From body measurement data, BMI was calculated as kg/m2 and categorized as less than 25.0 (underweight/normal weight), 25.0 to 29.9 (overweight), and 30.0 or more (obese).

Data on disease types were ascertained through the question “Has a doctor or other health professional told you that you had [disease]?” In addition to hypertension, disease types also were examined and categorized as positive by self-report: arthritis, cerebrovascular accident, chronic lower respiratory tract disease, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, liver disease, thyroid disease, cancer (other than skin), and diabetes mellitus.(14) Chronic lower respiratory tract disease included self-reported emphysema, chronic bronchitis, or asthma; coronary heart disease included coronary artery disease, angina, or a myocardial infarction. Diabetes included participants who also were taking insulin and/or diabetic pills. The cumulative number of positive responses to these four disease types was divided into four categories: 0, 1, 2, and 3 or more.

The reproductive health questionnaire reported on parity, type of delivery, and hysterectomy status. Women responded to the following question on parity: “How many times have you been pregnant?” with an open response that varied from 0 to 18, with categories created for 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more. Women were asked about the types of deliveries with two separate questions: “How many vaginal/cesarean deliveries have you had?” Response options were open-ended and varied from 0–15 for vaginal deliveries and 0–6 for cesarean deliveries. The variables for type of delivery were then dichotomized as none and at least one or more. A new mode of delivery variable included women who had never been pregnant, women who had only vaginal deliveries, women who had only cesarean deliveries, and women who had both. The question, “Have you had a hysterectomy, including a partial hysterectomy, that is, surgery to remove your uterus or womb?” defined hysterectomy status and response options were “yes/no.”

The 2005–06, 2007–08, and 2009–2010 survey data for women aged 20 years and older were combined in order to provide robust sample sizes. Prevalence estimates and 95% CIs were calculated using STATA 12.0 (STATA Corp. College Station, Texas), which incorporates the design effect, appropriate sample weights, and the stratification and clustering of the complex NHANES sample design. The sample weights adjust for unequal probabilities of selection and nonresponse. The Pearson’s χ 2 test was used to assess the association between different pelvic floor disorders and demographic and medical characteristics. Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% were identified as statistically unreliable. Separate multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to assess factors associated with reporting one or more pelvic floor disorder using variables from the bivariate analysis that demonstrated statistically significant associations with each type of pelvic floor disorder. Race and ethnicity was dichotomized as Non-Hispanic White verses all other racial and ethnic groups in the multivariable analysis. Given collinearity when the mode of delivery variable (never pregnant, vaginal only, cesarean only, or both) was included in the multivariable model, mode of delivery was included in additional models with only exclusive categories (never pregnant and vaginal only or cesarean only or both). Prevalence ORs and 95% CIs were reported from the multivariable model, using the appropriate sampling weights, with the level of statistical significance set at p<0.05. In order to determine if the relationship between hysterectomy and one or more pelvic floor disorder differed by age, an interaction term was introduced.

RESULTS

From the 14,424 male and female participants (20 years and older), we evaluated data from 8,368 non-pregnant women. Of these women, 7,142 had urinary incontinence data, 7,046 had fecal incontinence data, and 7,071 had prolapse data, with overlap among 7,924 women with data on the presence of one or more pelvic floor disorder. Women with data on pelvic floor disorders were not statistically different than the women without pelvic floor disorder data for age, race and ethnicity, or education level (p>0.05).

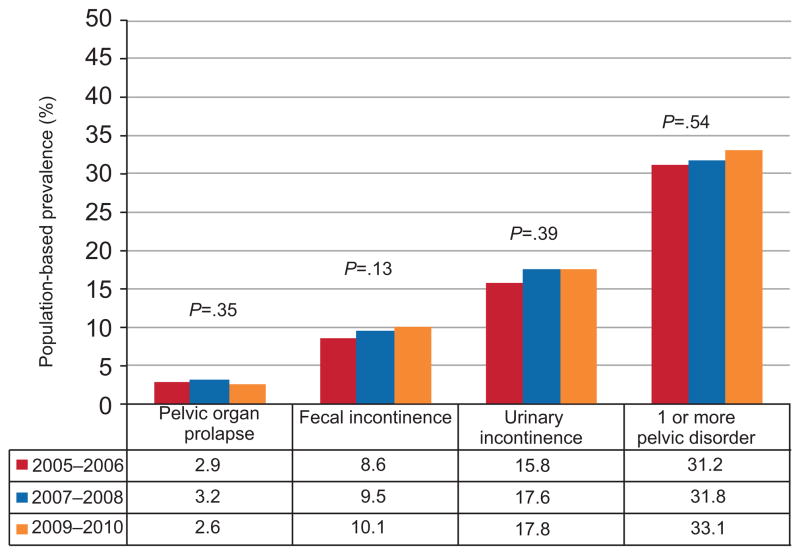

Overall, 25.0% (95% CI 23.6, 26.3) of U.S. women reported one or more pelvic floor disorder. Urinary incontinence was the most common disorder reported, with a combined prevalence of 17.1% (95% CI 15.8, 18.4). The combined population-based prevalence was 9.4% (95% CI 8.6, 10.2) for fecal incontinence and 2.9% (95% CI 2.5, 3.4) for prolapse. The population-based prevalence rates for each pelvic floor disorder were not statistically significant from 2005 – 2010 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Population-based prevalence trends in pelvic floor disorders among non-pregnant women in the United States.

In bivariate analysis (Table 1), increased age by decade was associated with higher prevalence rates for all pelvic floor disorders. The proportion of women with one or more pelvic floor disorder dramatically increased from 6.3% (95% CI 5.0, 7.8) in women aged 20–29 to 31.6% (95% CI 28.3, 35.1) for women 50–59 years to 52.7% (95% CI 48.1, 57.2) for women 80 and older. More non-Hispanic White women had urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence and one or more pelvic floor disorder than did other racial and ethnic groups. Mexican-American women reported higher rates of prolapse than other racial/ethnic groups. Lower educational status (less than a high school education) was associated with higher prevalence rates for each disorder and one or more pelvic floor disorder. However, a lower poverty status was not associated with fecal incontinence, but was associated with an increased prevalence of urinary incontinence, prolapse, and one or more pelvic floor disorder.

Table 1.

Weighted Prevalence Rates of Pelvic Floor Disorders by Demographic Categories in Nonpregnant U.S. Women (N = 7924)

| Weighted Prevalence, % (95% Confidence Interval) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Variable | No. of Women | Pelvic Organ Prolapse (n = 7071) | Fecal Incontinence (n = 7046) | Urinary Incontinence (n= 7142) | One or More Pelvic Floor Disorder (n = 7924)* |

|

| |||||

| Overall | 2.9 (2.5, 3.4) | 9.4 (8.6, 10.2) | 17.1 (15.8, 18.4) | 25.0 (23.6, 26.3) | |

|

| |||||

| Age, years | |||||

| 20–29 | 1128 | 0.5 (0.3, 1.1) | 2.6 (1.7, 3.9) | 3.5 (2.6, 4.9) | 6.3 (5.0, 7.8) |

|

| |||||

| 30–39 | 1117 | 2.1 (1.4, 3.2) | 4.3 (3.3, 5.6) | 9.2 (7.5, 11.2) | 13.6 (11.7, 15.7) |

|

| |||||

| 40–49 | 1318 | 2.3 (1.5, 3.5) | 8.8 (7.0, 10.9) | 15.0 (12.7, 17.6) | 23.4 (20.5, 26.6) |

|

| |||||

| 50–59 | 1085 | 4.0 (2.8, 5.7) | 11.0 (9.3, 12.9) | 22.4 (19.1, 26.1) | 31.6 (28.3, 35.1) |

|

| |||||

| 60–69 | 1193 | 5.1 (3.4, 7.6) | 16.5 (13.7, 19.6) | 24.7 (21.0, 28.8) | 38.5 (33.8, 43.3) |

|

| |||||

| 70–79 | 805 | 4.3 (2.8, 6.6) | 14.3 (11.5, 17.6) | 29.7 (26.0, 33.6) | 39.6 (35.6, 43.8) |

|

| |||||

| ≥80 | 496 | 4.0 (2.5, 6.5) | 21.0 (16.9, 25.8) | 38.2 (33.7, 43.0) | 52.7 (48.1, 57.2) |

|

| |||||

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic, Mexican American | 1267 | 5.3 (4.1, 6.8) | 6.3 (4.8, 8.1) | 17.2 (14.9, 19.6) | 24.0 (21.3, 26.8) |

|

| |||||

| Hispanic, Other | 662 | 4.5 (2.9, 7.1) | 6.8 (5.3, 8.8) | 13.1 (10.8, 15.9) | 20.0 (17.4, 22.9) |

|

| |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3475 | 2.7 (2.2, 3.4) | 10.2 (9.1, 11.30 | 18.2 (16.7, 20.0) | 26.4 (24.6, 28.2) |

|

| |||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1445 | 2.2 (1.5, 3.2) | 7.9 (6.5, 9.6) | 12.8 (11.3, 14.4) | 20.0 (17.8, 22.5) |

|

| |||||

| Other, including multi-racial | 293 | 2.1 (0.8, 5.5) | 8.7 (5.1, 14.5) | 13.9 (10.0, 19.1) | 22.6 (17.1, 29.2) |

|

| |||||

| P value | 0.01 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.002 | |

|

| |||||

| Education | |||||

| <High school | 1960 | 4.8 (3.8, 6.1) | 12.0 (10.2, 14.0) | 23.8 (21.7, 26.1) | 32.6 (30.3, 35.1) |

|

| |||||

| High school | 1675 | 3.1 (2.1, 4.5) | 9.3 (7.8, 10.9) | 18.4 (16.3, 20.7) | 27.0 (25.0, 23.7) |

|

| |||||

| >High school | 3496 | 2.2 (1.7, 2.8) | 8.6 (7.4, 10.0) | 14.5 (13.0, 16.1) | 21.8 (20.0, 23.70 |

|

| |||||

| P value | <0.001 | 0.03 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Poverty income ratio | |||||

| <1 | 1369 | 4.3 (3.3, 5.4) | 9.3 (7.5, 11.5) | 19.6 (17.2, 22.3) | 27.3 (24.6, 30.3) |

|

| |||||

| 1–2 | 1832 | 3.7 (2.7, 5.1) | 11.4 (10.0, 13.1) | 19.2 (17.0, 21.6) | 27.9 (25.7, 30.2) |

|

| |||||

| >2 | 3941 | 2.4 (1.9, 3.0) | 8.8 (7.8, 9.9) | 16.0 (14.6, 17.4) | 23.6 (22.2, 25.2) |

|

| |||||

| p value | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| BMI | |||||

| <25.0 | 2181 | 2.0 (1.4, 2.7) | 7.5 (6.4, 8.8) | 10.3 (8.9, 11.9) | 17.8 (15.7, 19.5) |

|

| |||||

| 25.0 – 29.9 | 2059 | 3.5 (2.5, 4.7) | 9.3 (7.8, 11.1) | 18.1 (16.1, 20.2) | 26.5 (24.3, 28.8) |

|

| |||||

| ≥30.0 | 2902 | 3.4 (2.7, 4.2) | 11.2 (9.5, 13.2) | 22.9 (20.6, 25.5) | 31.1 (28.5, 33.7) |

|

| |||||

| P value | 0.02 | 0.007 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Self-reported conditions/comorbid diseases (cumulative count) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 0 | 3445 | 1.9 (1.5, 2.8) | 5.6 (4.6, 6.9) | 9.7 (8.7, 10.8) | 15.6 (14.4, 16.8) |

|

| |||||

| 1 | 1938 | 3.7 (2.7, 5.1) | 9.4 (8.2, 10.9) | 20.3 (17.9, 22.9) | 28.5 (26.0, 31.1) |

|

| |||||

| 2 | 1017 | 4.2 (3.1, 5.8) | 15.8 (13.4, 18.5) | 27.3 (23.7, 31.2) | 39.9 (36.5, 43.5) |

|

| |||||

| ≥3 | 708 | 4.5 (3.2, 6.5) | 23.0 (18.5, 28.2) | 37.2 (33.3, 42.2) | 50.1 (45.6, 54.6) |

|

| |||||

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Hysterectomy | |||||

|

| |||||

| No | 4621 | 2.3 (1.9, 2.7) | 8.0 (7.2, 8.9) | 14.7 (13.5, 16.0) | 21.8 (20.5, 23.1) |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 1717 | 5.4 (4.0, 7.3) | 16.6 (14.6, 18.8) | 29.5 (26.8, 32.3) | 42.2 (39.1, 45.4) |

|

| |||||

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Parity | |||||

| 0 | 1018 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.6) | 4.6 (3.4, 6.3) | 7.9 (6.4, 9.8) | 11.5 (9.6, 13.8) |

|

| |||||

| 1 | 784 | 1.4 (0.7, 2.9) | 10.3 (7.6, 13.7) | 11.8 (9.4, 14.9) | 21.1 (17.8, 24.9) |

|

| |||||

| 2 | 1450 | 3.2 (2.3, 4.5) | 8.3 (6.7, 10.1) | 15.6 (13.4, 18.2) | 23.8 (21.0, 26.8) |

|

| |||||

| 3 | 1416 | 3.2 (2.2, 4.5) | 11.1 (9.1, 13.4) | 20.5 (18.0, 23.3) | 28.7 (25.9, 31.6) |

|

| |||||

| ≥4 | 2462 | 4.5 (3.7, 5.6) | 11.8 (10.2, 13.5) | 23.9 (21.7, 26.3) | 33.6 (30.9, 36.5) |

|

| |||||

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Mode of delivery | |||||

|

| |||||

| Never pregnant | 1018 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.3) | 4.6 (3.4, 6.3) | 7.9 (6.4, 9.8) | 11.5 (9.6, 13.8) |

|

| |||||

| Vaginal delivery | 4527 | 4.0 (3.3, 4.8) | 11.5 (10.5, 12.6) | 20.6 (18.9, 22.4) | 30.4 (28.6, 32.3) |

|

| |||||

| Cesarean delivery | 723 | 1.9 (1.1, 3.3) | 6.4 (4.6, 8.8) | 12.7 (10.4, 15.4) | 18.4 (15.7, 21.5) |

|

| |||||

| Vaginal and cesarean deliveries | 571 | 2.3 (1.2, 4.1) | 7.2 (4.3, 11.7) | 19.5 (15.5, 24.1) | 25.3 (19.9, 31.5) |

|

| |||||

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Sample size higher for more than one pelvic floor disorder than for pelvic organ prolapse (POP), fecal incontinence (FI), or urinary incontinence (UI) alone due to overlap for POP, FI, UI or a combination of these.

All P values calculated using chi-square analysis with the appropriate sampling weights.

Higher BMI, a greater number of cumulative self-reported conditions and diseases, and hysterectomy were significantly associated with an increased prevalence of each type of disorder as well as having one or more pelvic floor disorder (Table 1). Increasing parity was associated with increased prevalence rates of urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, prolapse and one or more pelvic floor disorder. Vaginal delivery was associated with higher rates of POP, FI, UI and having one or more pelvic floor disorder, as compared to cesarean delivery, never being pregnant, and having both a vaginal delivery and a cesarean. A lower prevalence of each disorder and having one or more pelvic floor disorder was found for women who had never been pregnant as compared to the other parity statuses.

After adjusting for age in decades, race, education, poverty status and other reproductive factors (parity, type of delivery), the odds of having one or more pelvic floor disorder increased with being overweight (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1, 1.6) or obese (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.3, 2.0) when compared to normal weight women in all models (Table 2). In addition, a prior hysterectomy, greater parity and having co-morbid diseases were associated with having one or more pelvic floor disorder (Table 2). An interaction term for age and hysterectomy was not significant. Mode of delivery (cesarean delivery or vaginal delivery) was not associated with having one or more pelvic floor disorder. Given collinearity, adjustment for reporting both vaginal and cesarean deliveries was assessed in a separate multivariable model and was not significantly associated with having at least 1 pelvic floor disorder (data not shown).

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis of Demographic Categories and the Odds of Having one or more Pelvic Floor Disorder in Nonpregnant U.S. Women from the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| n=6115 | ||

|

| ||

| Age (decade) | 1.2 (1.2, 1.3) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Non-Hispanic White vs all other racial/ethnic groups | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) | 0.009 |

|

| ||

| >High School Education | 0.9 (0.9, 1.0) | 0.04 |

|

| ||

| Higher Poverty Income Ratio | 0.9 (0.9, 1.0) | 0.02 |

|

| ||

| BMI | ||

| <25.0 | 1.0 | |

|

| ||

| 25.0 – 29.9 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) | 0.004 |

|

| ||

| ≥30.0 | 1.6 (1.3, 2.0) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Co-morbid diseases | ||

| 0 | 1.0 | |

|

| ||

| 1 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) | 0.001 |

|

| ||

| 2 | 1.6 (1.4, 2.0) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| ≥3 | 2.1 (1.6, 2.6) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Hysterectomy | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 1.0 | |

|

| ||

| 1 | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1) | 0.004 |

|

| ||

| 2 | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) | 0.009 |

|

| ||

| 3 | 1.8 (1.3, 2.5) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| ≥4 | 2.0 (1.5, 2.6) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Mode of deliveryNever pregnant | 1.0 | |

|

| ||

| Vaginal delivery only | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 0.7 |

|

| ||

| Cesarean delivery only | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.3 |

CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

These results suggest the prevalence rates of pelvic floor disorders (urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse) have remained stable over the past cycles of data from the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey. These conditions represent a major public health burden, as one quarter of all adult women suffer from at least one pelvic floor disorder. Although we did not detect a statistically significant difference in prevalence rates from 2005–2010, it is likely the aging of the population and the obesity epidemic will lead to increases in the number of women affected by these conditions.

Our study confirms prior findings that the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders significantly increases with age. Using aggregated survey data from 2005–2010, our estimates were similar to prior data from 2005–2006 (1) and highlight that 40% of women aged 60–79 and 53% of women 80+ suffer from at least one symptomatic disorder. Although we did not see an increase in the prevalence rates from 2005–2010, it is likely the prevalence of these disorders will increase, given the fact that the U.S. population 65 years and older is expected to double from 40.2 million in 2010 to 88.5 million in 2050.(15) These estimates also underscore the importance of training providers to care for the multitude of women who are currently suffering from pelvic floor disorders or who will develop symptoms.

Increasing BMI was associated with a higher prevalence of each pelvic floor disorder. It is important to evaluate the impact of being overweight and obese on pelvic floor disorders, given that this is a modifiable risk factor within a population in which the prevalence of obesity is 35%.(4) Obesity has previously been reported as a risk factor for urinary incontinence.(16–18) Furthermore, several studies have documented improvements in urinary incontinence after weight loss and bariatric surgery.(19–23) Higher BMI has also been associated with prolapse (2, 3); however, weight loss may not improve bothersome prolapse symptoms.(24) Obesity has also been associated with fecal incontinence, which affects 16–68% of obese individuals.(25) The prevalence of fecal incontinence has also been shown to decrease after weight loss after bariatric surgery (19), further emphasizing the importance of obesity as a modifiable risk factor. The association of obesity with pelvic floor disorders highlights the importance of addressing weight loss in obese women and of screening for these disorders in overweight and obese women.

Hysterectomy and increasing parity were also associated with pelvic floor disorder symptoms of women in our study. While prior studies have reported an association between hysterectomy and an increased risk of prolapse (26, 27), the relationship between hysterectomy and urinary incontinence is less definitive. An older systematic review reported that a hysterectomy increases the risk of UI (28) while a more recent evidence review found no association.(29) Our findings regarding parity and the association with prolapse (2, 27) and urinary incontinence is consistent with those of several prior studies. (18, 31, 32) Conflicting evidence exists regarding the role of parity and hysterectomy on the prevalence rate of fecal incontinence among epidemiologic studies and more confirmatory data are needed. (33–35) However, studies have shown that a third or fourth degree anal sphincter tear and an instrumented delivery consistently increased the odds of having post-partum fecal incontinence.(36–38)

The limitations of our study include that causality cannot be ascertained, as the cross-sectional data were analyzed. Health status and reproductive variables were self-reported; however, questions from validated instruments were used to assess the presence of pelvic floor disorders. This national survey assesses only non-institutionalized adults, which may limit the generalizability of these results to other groups. Additionally, no data were available regarding whether an operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum) was performed, degree of obstetrical injuries, history of episiotomy, indication for hysterectomy, or prior surgery for pelvic floor disorders, all of which are factors that may influence the risk of these conditions. Finally, the odds ratios of variables associated with pelvic floor disorder symptoms reflect a modest effect.(39)

Information regarding the national prevalence of urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse is critical to understanding the public health burden of these conditions. Furthermore, understanding the prevalence of these disorders provides useful information regarding the need to address these symptoms proactively with patients as well as to train healthcare providers to manage these disorders. Our findings underscore the association between higher BMI and pelvic floor disorders. Thus, more clinical studies are warranted regarding weight reduction as a potential first-line intervention for the treatment of pelvic floor disorders among overweight and obese women.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part from Veterans Health Administration Career Development Awards (CDA-2) to Drs. Markland (B6126W) and Vaughan (1 IK2 RX000747-01). Dr. Wu is supported by K23HD068404, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure:

Dr. Wu has been a consultant for Proctor and Gamble. Dr. Vaughan has received research grants support from Astellas. Dr. Richter has received research grants from Pelvalon, Astellas, and Univ. of California/Pfizer. She has been a consultant for the Astellas Advisory Board, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Uromedica, IDEO, and Xanodyne. She has also received an education grant from Warner Chilcott. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1311–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;186(6):1160–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swift S, Woodman P, O’Boyle A, Kahn M, Valley M, Bland D, et al. Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): the distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Mar;192(3):795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012 Jan;(82):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erekson EA, Lopes VV, Raker CA, Sung VW. Ambulatory procedures for female pelvic floor disorders in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;203(5):497 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jonsson Funk M, Levin PJ, Wu JM. Trends in the surgical management of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Apr;119(4):845–51. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824b2e3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliphant SS, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Trends in stress urinary incontinence inpatient procedures in the United States, 1979–2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;200(5):521 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erekson EA, Lopes VV, Raker CA, Sung VW. Ambulatory procedures for female pelvic floor disorders in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Aug 24; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones KA, Shepherd JP, Oliphant SS, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Trends in inpatient prolapse procedures in the United States, 1979–2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 May;202(5):501 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonsson Funk M, Edenfield AL, Pate V, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Wu JM. Trends in use of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jan;208(1):79 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) NCHS Research Ethics Board (ERB) Approval. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- 12.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, Kane RL, Mavrantonis C, Thorson AG, et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence: the fecal incontinence severity index. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 1999 Dec;42(12):1525–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02236199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the women’s health initiative: Gravity and gravidity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;186(6):1160–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss CO, Boyd CM, Yu Q, Wolff JL, Leff B. Patterns of prevalent major chronic disease among older adults in the United States. Jama. 2007 Sep 12;298(10):1160–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1160-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. THE NEXT FOUR DECADES, The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melville JL, Katon W, Delaney K, Newton K. Urinary incontinence in US women: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Mar 14;165(5):537–42. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waetjen LE, Liao S, Johnson WO, Sampselle CM, Sternfield B, Harlow SD, et al. Factors associated with prevalent and incident urinary incontinence in a cohort of midlife women: a longitudinal analysis of data: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2007 Feb 1;165(3):309–18. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danforth KN, Townsend MK, Lifford K, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. Risk factors for urinary incontinence among middle-aged women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Feb;194(2):339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgio KL, Richter HE, Clements RH, Redden DT, Goode PS. Changes in urinary and fecal incontinence symptoms with weight loss surgery in morbidly obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Nov;110(5):1034–40. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000285483.22898.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subak LL, Whitcomb E, Shen H, Saxton J, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS. Weight loss: a novel and effective treatment for urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2005 Jul;174(1):190–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000162056.30326.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subak LL, Johnson C, Whitcomb E, Boban D, Saxton J, Brown JS. Does weight loss improve incontinence in moderately obese women? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002;13(1):40–3. doi: 10.1007/s001920200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greer WJ, Richter HE, Bartolucci AA, Burgio KL. Obesity and pelvic floor disorders: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;112(2 Pt 1):341–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817cfdde. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subak LL, Wing R, West DS, Franklin F, Vittinghoff E, Creasman JM, et al. Weight loss to treat urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 29;360(5):481–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers DL, Sung VW, Richter HE, Creasman J, Subak LL. Prolapse symptoms in overweight and obese women before and after weight loss. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012 Jan-Feb;18(1):55–9. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e31824171f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poylin V, Serrot FJ, Madoff RD, Ikramuddin S, Mellgren A, Lowry AC, et al. Obesity and bariatric surgery: a systematic review of associations with defecatory dysfunction. Colorectal Dis. 2011 Jun;13(6):e92–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mant J, Painter R, Vessey M. Epidemiology of genital prolapse: observations from the Oxford Family Planning Association Study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997 May;104(5):579–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rortveit G, Brown JS, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK, Creasman JM, Subak LL. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: prevalence and risk factors in a population-based, racially diverse cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jun;109(6):1396–403. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000263469.68106.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown JS, Sawaya G, Thom DH, Grady D. Hysterectomy and urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Lancet. 2000 Aug 12;356(9229):535–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robert M, Soraisham A, Sauve R. Postoperative urinary incontinence after total abdominal hysterectomy or supracervical hysterectomy: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Mar;198(3):264 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown JS, Nyberg LM, Kusek JW, Burgio KL, Diokno AC, Foldspang A, et al. Proceedings of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases International Symposium on Epidemiologic Issues in Urinary Incontinence in Women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(6):S77–88. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rortveit G, Hannestad YS, Daltveit AK, Hunskaar S. Age- and type-dependent effects of parity on urinary incontinence: the Norwegian EPINCONT study. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Dec;98(6):1004–10. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Halli AD, Jones RW, Richter HE, Redden DT, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Apr;53(4):629–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varma MG, Brown JS, Creasman JM, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK, Beattie MS, et al. Fecal incontinence in females older than aged 40 years: who is at risk? Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2006 Jun;49(6):841–51. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0535-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Townsend MK, Matthews CA, Whitehead WE, Grodstein F. Risk factors for fecal incontinence in older women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Jan;108(1):113–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bols EM, Hendriks EJ, Berghmans BC, Baeten CG, Nijhuis JG, de Bie RA. A systematic review of etiological factors for postpartum fecal incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010 Mar;89(3):302–14. doi: 10.3109/00016340903576004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG, Melton LJ, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR. Obstetric trauma, pelvic floor injury and fecal incontinence: a population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jun;107(6):902–11. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacArthur C, Wilson D, Herbison P, Lancashire RJ, Hagen S, Toozs-Hobson P, et al. Faecal incontinence persisting after childbirth: a 12 year longitudinal study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2013;120(2):169–79. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grimes DA, Schulz KF. False alarms and pseudo-epidemics: the limitations of observational epidemiology. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;120(4):920–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31826af61a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]