Abstract

The cbb3 cytochrome c oxidases are distant members of the superfamily of heme copper oxidases. These terminal oxidases couple O2 reduction with proton transport across the plasma membrane and, as a part of the respiratory chain, contribute to the generation of an electrochemical proton gradient. Compared with other structurally characterized members of the heme copper oxidases, the recently determined cbb3 oxidase structure at 3.2 Å resolution revealed significant differences in the electron supply system, the proton conducting pathways and the coupling of O2 reduction to proton translocation. In this paper, we present a detailed report on the key steps for structure determination. Improvement of the protein quality was achieved by optimization of the number of lipids attached to the protein as well as the separation of two cbb3 oxidase isoenzymes. The exchange of n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside for a precisely defined mixture of two α-maltosides and decanoylsucrose as well as the choice of the crystallization method had a most profound impact on crystal quality. This report highlights problems frequently encountered in membrane protein crystallization and offers meaningful approaches to improve crystal quality.

Keywords: cbb3 oxidase, membrane protein, crystallization, lipid content, controlled delipidation, detergent

Introduction

Although the crystallization of membrane proteins has undergone enormous developments and the number of available X-ray structures has significantly increased within the recent years, in most cases the production of well diffracting crystals of integral membrane proteins (IMPs) remains a tedious and time consuming work, requiring substantial amounts of resource.1 Despite the massive difficulties, IMPs represent a major subject of current structural research founded in their fundamental contribution to energy conversion, transmembrane transport of substances, and signal transduction. The pivotal role of IMPs in cellular processes assigns an immense biological and pharmaceutical relevance to these targets. This situation is contrasted by the limited number of IMP structures known.

Besides the frequently limited availability of protein, another major reason for lower success rates concerning the determination of IMP X-ray structures is rooted in the necessity of a non-physiological detergent layer, which covers hydrophobic protein surface areas after extraction from the cellular membrane and thereby renders the IMP soluble in aqueous solvents.

Several methods for the crystallization of IMPs have been developed within the past three decades. The classical crystallization method for IMPs, nowadays often referred to as in surfo, was employed within this project and is based on the three-dimensional arrangement of the solubilized protein–detergent complexes within a crystal lattice. For the implementation of this method, finding a suitable detergent, which individually retains protein stability in the same way as it allows the formation of stable crystal contacts between neighboring molecules, is one of the most difficult problems. The establishment of a purification procedure balancing between the removal of excess lipid hindering the formation of intermolecular crystal contacts and the preservation of structurally and crystallographically important lipids bound to the protein is of the same significance.

To counteract the potentially negative influence of the artificial environment provided by the in surfo approach, a different strategy in membrane protein crystallography has led to the introduction of lipid based methods rather recently. These methods are predicated on the re-integration of the detergent purified IMPs into lipidic systems, simulating their endogenous environment for crystallogenesis. Alongside the so-called in meso crystallization techniques employing lipidic cubic phases (LCP)2 and lipidic sponge phases,3 bicelles4 forming a lipid bilayer-like structure proved to be a successful matrix for membrane protein crystal growth. Among others, the practical challenges involved in these methods are related to the temperature dependence of the lipidic phase, the potential incompatibility of the respective membrane protein with the lipids appropriate to form cubic phases or bicelles and balancing the influence of various additives and precipitants on the property and stability of the cubic phase.

The membrane protein crystallized in this study is the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase (cbb3-CcO) from Pseudomonas stutzeri ZoBell. Discovered in 1993 in Bradyrhizobium japonicum by Preisig et al.,5 cbb3-CcOs are members of the heme-copper oxidase superfamily (HCO). Exclusively present in bacteria, cbb3-CcOs like other HCOs couple the reduction of O2 to H2O with vectorial proton transport across the plasma membrane. Characterized by a very high affinity for oxygen,6 cbb3-CcO is preferably observed under oxygen limitation. Besides the importance of the enzyme complex in symbiotic nitrogen fixation5 and colonization of human tissues by several pathogenic bacteria,7 it has been implicated in signal transduction in purple bacteria.8 For a number of bacterial strains, two isoenzymes of cbb3-CcO were identified within the genome,9 and in Pseudomonas aeruginosa it could be shown that its two cbb3-CcO isoforms are differentially regulated and possess different respiratory functions.10

Derived from comparative genomic studies11–13 and the recent X-ray structure,14 cbb3-CcOs exhibit substantial structural differences to the well investigated mitochondrial type cytochrome c oxidase concerning the electron supply system, the proton conducting pathway including two cavities and the coupling region involving the heme b and b3 propionates as well as two loops linked via a Ca2+ ion.14 However, they show a close relationship to the nitric oxide reductases (NORs),15 another distant member of the HCO superfamily,16 and, interestingly, also display NOR activity in vitro.17

Like other members of the HCO superfamily, cbb3-CcOs comprise a central catalytic subunit (CcoN) consisting of 12 transmembrane helices.16 Besides CcoN (52.8 kDa), the cbb3-CcO from P. stutzeri ZoBell, previously characterized in molecular, spectroscopic, and structural aspects by Pitcher et al.,18,19 contains the transmembrane subunits CcoO (22.9 kDa) and CcoP (34 kDa) that harbor one and two heme c molecules, respectively.

Crystallization of the cbb3-CcO protein complex required long-term research efforts that succeeded after an iterative development and optimization of purification and crystallization strategies. This report describes the steps crucial to obtain crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography and also highlights interdependent factors between purification, lipid content, detergent choice, and crystallization conditions.

Results

Protein purification, lipid content, isoenzyme separation, and their impact on crystallization

The cbb3-CcO was initially isolated and purified according to a protocol previously published,20 which consisted of an ion exchange chromatography (IEC) step on DEAE Toyopearl 650C followed by a Cu2+-loaded immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) step and a final IEC step on DEAE Toyopearl 650C. The protein obtained could be crystallized under various conditions using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method but always in the same hexagonal crystal form with a c axis of approximately 700 Å. The best crystals diffracted to about 7.0 Å, showed a high mosaicity as well as multiple lattices and were thus not suitable for X-ray crystallographic structure determination.20

A remarkably high lipid content was the first factor, which was identified to contribute to the poor diffraction quality of the crystals. Typically, cbb3-CcO eluted from the terminal DEAE Toyopearl 650C column in a very broad peak during gradient application and contained approximately 80 lipids per cbb3-CcO [Fig. 1(a)]. The substitution of the matrix of the terminal column for a Q Sepharose High Performance (HP) material resolved the formerly broad elution peak into four cbb3-CcO containing peaks with different lipid content varying between 3 and 50 lipids per cbb3-CcO [Fig. 1(e1–e4)]. Subsequently, a variety of IEC materials was tested for their potential to reduce the lipid content. For comparability, an experimental setup was employed, which kept the previous separation strategy, gradients, and buffers essentially unchanged.20 The most promising column combination replaced both DEAE Toyopearl 650C columns by Q Sepharose HP columns, yet the resulting protein preparation still contained up to approximately 54 lipids per cbb3-CcO [Fig. 1(f)].

Figure 1.

Phospholipid content of cbb3 oxidase preparations in lipids per cbb3-CcO. Pure cbb3 oxidase was analyzed for lipid content with a phosphorous assay21 (a–h) or HPLC analysis24 (i). Samples were obtained from purifications using different column materials and combinations thereof. For sample e, four different peaks eluting from the terminal column were analyzed separately. (a) DEAE Toyopearl 650C–IMAC Cu2+–DEAE Toyopearl 650C; (b) DEAE Toyopearl 650C–DEAE Toyopearl 650C; (c) DEAE Toyopearl 650C–IMAC Cu2+–DEAE Sepharose FF; (d) 0.08% deoxycholate wash of membranes–DEAE Sepharose FF–IMAC Cu2+–DEAE Toyopearl 650C; (e) DEAE Toyopearl 650C–IMAC Cu2+–Q Sepharose HP; (f) Q Sepharose HP–IMAC Cu2+–Q Sepharose HP; (g) Q Sepharose HP–Chromatofocusing–Q Sepharose HP; (h) Q Sepharose HP–Chromatofocusing–IMAC Cu2+–Q Sepharose HP; (i) Q Sepharose HP–Chromatofocusing–IMAC Cu2+–Q Sepharose HP–IEF.

Continuous efforts to reduce the lipid content further led to the introduction of a chromatofocusing column (PBE94) to the purification protocol. This measure proved to be one of the most crucial innovations during crystal optimization. As chromatofocusing is a rather strongly delipidating chromatographic technique,22 its application is rather limited in membrane protein purification. In our case, the enzyme eluting at pH ∼5.5 within the applied gradient remained stable and contained ∼12 lipids per cbb3-CcO [Fig. 1(h)]. A final gel-based isoelectric focusing step (IEF)23 prior to crystallization resulted in an even more reduced lipid content of ∼6–9 lipids per cbb3-CcO [Fig. 1(i); TableI]. This step was initially introduced to improve the protein homogeneity, yet as a side effect it further reduced the lipid content of the protein complex. At a later stage, the reduced lipid content was found to have a detrimental effect on crystallization, and the IEF step was subsequently removed again from the purification protocol (see below).

Table I.

Number and Type of Lipid Molecules Attached per Protein Complex in Repeated cbb3-CcO Preparations

| Lipid/protein | Preparation I | Preparation II | Preparation III | Preparation IV | Preparation VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiolipin peak 1 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Cardiolipin peak 2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | 5.1 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 4.1 |

| Total | 6.3 | 9.1 | 8.0 | 7.2 | 6.3 |

The protein was prepared according to the purification scheme given in Figure 1(i) employing Q Sepharose HP–Chromatofocusing–IMAC Cu2+–Q Sepharose HP and IEF. Lipids were detected by HPLC analysis according to the method published for the acyl carrier proteins from Yarrowia lipolytica.24 The phospholipids were identified by comparison with phospholipid standards. The two peaks eluting in the region of the cardiolipin standard can either contain cardiolipin with large variations in fatty acid composition or phosphatidylglycerol.

After integration of the controlled delipidation process into the purification protocol (at this stage consisting of a Q Sepharose HP column followed by a chromatofocusing column, a Cu2+ loaded IMAC column and a final Q Sepharose HP column [Fig. 1(h)]), the hexagonal crystals could not be reproduced anymore. This observation suggests that their formation was induced by the enormous lipid-detergent belt possibly sterically favoring the hexagonal arrangement. By contrast, very small differently shaped crystals grew under new crystallization conditions (precipitants polyethylene glycol [PEG] 550 or 750 MME and sodium malonate or molybdate as salt) and were dramatically improved in size and diffraction quality after conversion of the crystallization method from vapor diffusion to microbatch under oil25,26 (Fig. 5). The crystals belonged to the monoclinic space groups P2(1) or C2 with significantly shorter unit cell axes and diffracted to a maximum resolution of 3.8 Å after introduction of decanoylsucrose (DS) and cytochrome c from Saccharomyces cerevisiae into the crystallization protocol (see below). Data processing was only possible to 5.2 Å resolution as the diffraction pattern persistently suffered from high anisotropy and a high sensitivity to radiation damage.

Figure 5.

Summary of the iterative improvement of cbb3-CcO crystals toward structure determination. The development of the purification and crystallization protocol is shown in linear nearly chronologic manner. In the case of mentioned anisotropic diffraction of crystals, the maximum resolution is stated; differences of 1 Å or even more between different crystal orientations were regularly observed in these cases.

A second serious obstacle for successful crystallization was formed by the simultaneous presence of two different isoforms of cbb3-CcO within the bacterial cell. The recently reported genome of a different P. stutzeri strain, A1501,27 revealed the existence of two cbb3-CcO operons in a similar arrangement like in P. aeruginosa,10 which had not been discovered in an initial genetic analysis of the P. stutzeri strain ZoBell.18 Nevertheless, peptide mass fingerprinting analysis performed on crystals of cbb3-CcO from strain ZoBell revealed discrepancies between the deposited sequence18 and the sequence obtained from crystallized protein.14 Subsequently, the existence of a second cbb3-CcO operon could be confirmed on the DNA level (EMBL-Bank HM130676.1)14 and for this reason, special attention had to be paid to sample homogeneity.

Separation of the different isoenzymes was achieved by optimizing the buffer conditions on the IMAC column. It was recognized that complete omission of NaCl from the gradient forming buffers resulted in three separated peaks containing cbb3-CcO, whereas the initial chromatogram with 200 mM NaCl in the buffers showed a single peak with a slight shoulder.20 Peptide mass fingerprinting analysis (data not shown) revealed that all three separated peaks contained polypeptide fragments corresponding to sequences of the first cbb3-CcO isoenzyme. The second elution peak of the IMAC column, however, additionally contained polypeptide fragments originating from the second isoenzyme. Using only the third peak eluting from the IMAC column for further purification and crystallization, the obtained crystals only contained the first isoenzyme as was expected.14

It has to be noted that even though the first IMAC elution peak solely contained the pure first isoenzyme, no crystals could be obtained from this fraction. As no significant differences concerning purity and enzymatic activity were observed between peak 1 and 3, the different lipid content might be responsible for the difference in crystallizability. At this stage of purification, the third peak contains approximately 14 lipids per cbb3-CcO, whereas the first peak contains approximately 22 lipids per cbb3-CcO.

Crystallization attempts using the optimized purification protocol described (including IEF; [Fig.1 (i)]) in conjunction with new crystallization conditions employing pentaerythritol ethoxylate (PEE) 15/04 as precipitant28 in combination with ammonium formate yielded monoclinic crystals (Fig. 5). They showed isotropic diffraction to 3.7–3.8 Å but no reflections at higher resolution. As the crystals were very sensitive to radiation damage, complete native data could only be collected to 4.2 Å resolution which, nevertheless, represented an improvement of approximately 1 Å.

The search for optimal detergent conditions

At the stage of conversion from vapor diffusion to microbatch under paraffin oil (Fig. 5), a range of detergents was tested as additive to improve the preliminary crystallization conditions. Screening was set up by supplementation of the protein solution in approximately 0.02% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DDM) with various other detergents prior to crystallization. Crystals grew after addition of either 1× the critical micelle concentration (CMC) CYMAL 5, CYMAL 6, dodecanoylsucrose, n-tetradecyl-β-d-maltoside, n-decyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DM) or DS with several PEGs as precipitant and sodium molybdate as salt in microbatch under oil. Nevertheless, only the addition of DS at a final concentration of 0.125% was found to be beneficial for crystal growth and positively influenced the isotropy of the diffraction pattern.

Cbb3-CcO was initially prepared in β-DDM purchased from Anatrace (Maumee) with an α-isomer content <0.2% and yielded the poor quality hexagonal crystals as well as both monoclinic crystal forms described diffracting to approximately 3.8 Å resolution using either PEG or PEE as precipitant. Anticipating improved diffraction properties by application of purer detergent, ultrapure β-DDM from Glycon Biochemicals GmbH (Luckenwalde, Germany) with an α-isomer content of <0.01% was used. Surprisingly, the resulting crystals showed a severe problem of multiple lattices. The unfavorable effect of the lacking α-isomer was limited to protein crystallization, since purification in the purer detergent did not negatively influence crystal quality if the sample was treated with α-isomer containing β-DDM prior to crystallization. This result provided a first hint concerning the importance of the α-isomer within the crystallization process of the cbb3-CcO.

As the replacement of β-DDM by the α-isomer had been already shown to have a profound effect on the crystallization of other membrane proteins like the Na+/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli,29 we further explored the influence of n-dodecyl-α-d-maltoside (α-DDM) on the crystals of cbb3-CcO.

When β-DDM was exchanged for 0.04% α-DDM within the final purification step and supplemented with 0.125% DS and 0.018% β-DDM prior to crystallization (Fig. 5), crystals grown from a mixture of PEE 15/04, ammonium formate and ammonium tartrate in microbatch under oil diffracted to 3.5 Å and in rare cases even to 3.3 Å resolution. The space group switched to P21212.

The crystals still exhibited a very anisotropic diffraction behavior with fluctuations of the diffraction limit between 3.5 and 4.7 Å within the same crystal. Moreover, the reproduction of protein preparations yielding well diffracting crystals was difficult. The latter problem was found to be linked to fluctuating maltoside concentrations arising during the final purification and protein concentration steps. It was solved by the introduction of a chromatographic detergent exchange step14 followed by concentration using a 100 kDa cut off membrane centrifugal device prior to crystallization. This procedure ensured a precisely defined ratio of maltoside to DS in the buffers and reproducible properties of the protein detergent complex.

In continuative tests for the optimization of the detergent conditions, higher quality crystals were neither obtained with DS as single detergent nor with different concentrations of DS supplemented to α-DDM. Based on this result, protein samples in different α-maltosides, supplemented with 0.125% of DS, were prepared for experiments set up with the crystallization conditions discovered for cbb3-CcO in 0.04% α-DDM/0.125% DS/0.018% β-DDM (see above). For this purpose, protein in a “main” α-maltoside with 0.125% DS was prepared using the column exchange method. An “additive” α-maltoside was added at a fixed concentration of 0.018% just prior to crystallization. Simple increase of the “main” detergent by 0.018% was tested as well (TableII).

Table II.

α-Maltosides Tested in Microbatch Crystallization Conditions in Combination with 0.125% DS

| Detergents and concentrations | Diffraction limit (Å) | Crystal properties |

|---|---|---|

| 0.076% α-UDM | 3.0–3.8 | Anisotropic, sharp spots |

| 0.192% α-DM | 3.9–4.6 | Weak spots, multiple lattices |

| 0.058% α-DDM | 3.4–4.3 | Anisotropic, smeared at higher resolution |

| 0.058% α-UDM + 0.018% α-DM | 3.3–4.1 | Multiple lattices, less anisotropic |

| 0.058% α-UDM + 0.018% α-DDM | 3.2–4.2 | Less anisotropic compared with the other conditions, sharp spots, sometimes slightly smeared at higher resolution |

| 0.174% α-DM + 0.018% α-UDM | No crystals | |

| 0.174% α-DM + 0.018% α-DDM | 3.7–4.2 | Multiple lattices |

| 0.04% α-DDM + 0.018% α-UDM | 3.2–3.6 | Anisotropic |

| 0.04% α-DDM + 0.018% α-DM | 3.4–3.8 | Anisotropic |

It was discovered, that crystals grown with α-DM as single/“main” detergent tended to show diffraction patterns with multiple lattices, weak reflections, and smeared spots at higher resolution. If α-DM was used just as “additive” detergent to n-undecyl-α-d-maltoside (α-UDM), crystals diffracted with relatively low anisotropy but had multiple lattices. The crystals grown in α-DDM had a tendency to show anisotropic patterns and smeared spots at higher resolution. Crystals obtained with α-UDM also exhibited an anisotropic pattern yet showed extremely well defined spots.

The combination of 0.058% α-UDM, 0.125% DS, and 0.018% α-DDM revealed the most promising diffraction pattern with a slightly decreased anisotropy and well defined spots [Fig. 2(A)]. The best crystals diffracted to 3.3 Å resolution.

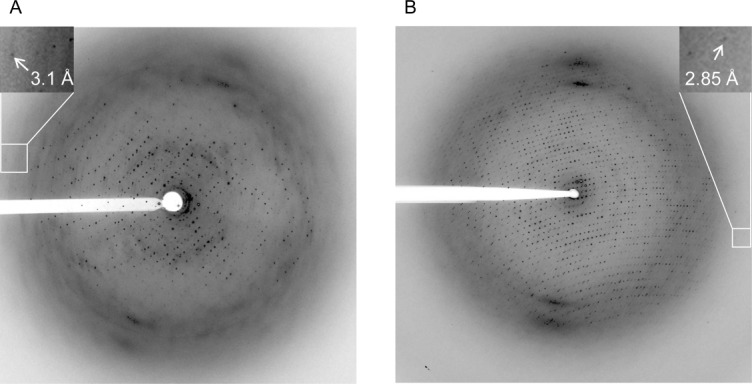

Figure 2.

Diffraction pattern of orthorhombic crystals grown from cbb3-CcO in 0.058% α-UDM, 0.125% DS and 0.018% α-DDM with PEE 15/04, ammonium formate, and ammonium tartrate. (A) Under microbatch conditions. (B) Under vapor diffusion conditions.

Subsequent removal of the IEF from the purification protocol at this stage (see above) yielded a more readily crystallizing protein preparation and resulted in protein detergent complex properties suitable for well-ordered crystal packing (Fig. 5).

Effect of the crystallization method on crystal quality

An unexpected observation during crystallization was the impact of the crystallization method. While the change from vapor diffusion to microbatch under oil had increased the size of the monoclinic plate shaped crystals from 0.03 mm × 0.05 mm to 0.2 mm × 0.3 mm during early stages of the process and yielded several interesting intermediate crystallization conditions (Fig. 5), the final breakthrough toward crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography was achieved by the conversion from microbatch back to the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at the final stage.

Although the overall crystallization conditions remained unchanged after conversion (except for the PEE concentration which dropped by about 10%; see section Materials and Methods) and the crystals obtained applying the vapor diffusion method still exhibited the same space group of P21212 with unit cell parameters of a = 137.3 Å, b = 281.6 Å, and c = 177.0 Å, they adopted a rhombohedral shape with a maximal size of 0.02 mm × 0.1 mm × 0.2 mm [Fig. 3(B)] instead of a plate shape [Fig. 3(A)]. Most importantly, the crystals grown in a detergent mixture of 0.058% α-UDM, 0.125% DS, and 0.018% α-DDM revealed nearly isotropic diffraction up to 3.1 Å resolution characterized by small well-shaped spots [Fig. 2(B)]. These crystals finally allowed X-ray structure determination.

Figure 3.

Crystal shapes of orthorhombic crystals grown from cbb3-CcO in 0.058% α-UDM, 0.125% DS and 0.018% α-DDM with PEE 15/04, ammonium formate, and ammonium tartrate. (A) Under microbatch conditions. (B) Under vapor diffusion conditions.

The improvement of the diffraction quality owing to the application of the vapor diffusion method, however, was almost exclusively limited to the most optimal detergent mixture found under microbatch conditions. Crystals grown with vapor diffusion in different detergent conditions (see TableII) adopted the same space group, yet only crystals grown in 0.076% α-UDM/ 0.125% DS showed comparable but not better quality than those used for structure determination. Notably, crystals grown with α-DM as additive diffracted to a slightly higher resolution compared with microbatch conditions but still showed high anisotropy and the presence of multiple lattices.

Other factors important for crystallization

The temperature had to be fixed at 21°C and alterations significantly influenced crystallization, especially the nucleation process. A decrease of the temperature by one or more degrees resulted in showers of small crystals. Moreover, a temperature increase to 25°C yielded crystals with poor diffraction properties.

Apart from the initial crystallization conditions,20 buffering the system resulted in a decrease of the resolution limit of the crystals. The crystallization solutions were therefore only composed of PEG or PEE as precipitant and salt without pH adjustments. Mixed with protein solution, the pH in the drops that yielded the crystals used for structure determination was approximately 7.5.

An interesting observation was the disproportionally high involvement of salts of organic acids in the numerous crystallization conditions found during crystallization protocol development. Recognized as effective precipitants already for a long time,30 tartrate, acetate, malonate and, in particular, formate had a beneficial effect on cbb3-CcO crystallization. Using the initial purification protocol,20 crystals already grew from protein in β-DDM with 200 mM ammonium formate and a wide range of PEGs but were not suitable for structure determination. With the revised purification protocol including chromatofocusing, IMAC with a salt-free gradient and IEF, monoclinic crystals arose in β-DDM/DS from PEE 15/04 and 200 mM ammonium formate. After exchanging the detergent from β-DDM/DS to a mixture of α-DDM/DS/β-DDM and subsequently to α-UDM/DS/α-DDM, orthorhombic crystals emerged with PEE 15/04, 200 mM ammonium formate, and 100 mM ammonium tartrate in microbatch under oil [Figs. 2(A) and 3(A)] and sitting drop vapor diffusion [Figs. 2(B) and 3(B)].

Two other compounds appeared to be crucial for crystallization. Cytochrome c from S. cerevisiae was originally added to the protein solution to increase the hydrophilic surface area of the protein by the formation of a binary complex. Although not found in the electron density, its presence turned out to be necessary for the growth of crystals with favorable morphology and reduced mosaicity. Interestingly, c-type cytochromes from horse heart, P. aeruginosa or Pichia pastoris could not replace the S. cerevisiae protein which suggests a transient but specific contact.

K3Fe(CN)6 or K4Fe(CN)6 were initially applied to crystallize cbb3-CcO either in a fully oxidized or reduced state. Surprisingly, the iron compounds in general favored the formation of the orthorhombic crystals used for structure determination. While the addition of 16 mM K3Fe(CN)6 or K4Fe(CN)6 reproducibly induced crystal growth, this process was impaired at 8 mM and abolished in their absence. This finding can be correlated with the binding of [Fe(CN)6]3− inside a positively charged cavity formed by the periplasmic CcoP domains of the four cbb3-CcO complexes in the asymmetric unit [Fig. 4(B)]. The iron compound may serve to stabilize the “crystallographic tetramer” [Fig. 4(A)] or perhaps even triggers its formation. In addition, K3Fe(CN)6 and K4Fe(CN)6 influenced the diffraction pattern in a different manner. While in the oxidized state the reflections were well defined and intense, in the reduced state they still exhibited a well-defined profile but were rather weak and showed an increased sensitivity to X-ray radiation, especially at high resolution.

Figure 4.

Special features of the crystal lattice in crystals of cbb3-CcO from P. stutzeri. (A) Four ccb3 oxidase complexes assemble to a non-physiological tetramer structure in the asymmetric unit of the orthorhombic type II crystals. For the central tetramer, subunits CcoN and CcoO are drawn in green, the CcoP subunits are shown in red. Subunits CcoN and CcoO in the peripheral tetramers are drawn in gray and subunits CcoP in yellow, respectively. The different tetramers are predominantly linked by two hydrophilic parts of the CcoP subunits. (B) [Fe(CN)6]3− is important for crystal formation. The negatively charged [Fe(CN)6]3− binds to a region of positively charged residues in between two CcoP subunits. (C) The difference electron density map after simulated annealing without [Fe(CN)6]3− shows difference densities at a contour level of 12 σ (green) and 3.1 σ (mint) and supports correct modeling.

Crystallization set-up, cryoprotection, and screening

The usage of freshly prepared protein was of particular importance for successful crystallization. All preparation steps had to be carried out as fast as possible after cell harvest. Long storage times of bacterial membranes and purified protein at −80°C prior to crystallization led to a reduction of the crystal quality proportional to the storage length. Crystallization experiments were therefore immediately performed after protein preparation. Likewise, crystals were frozen 1–2 days after their emergence because a prolonged incubation in the drops induced the formation of multiple lattices.

For cryo-crystallography, the oil PFO-X 125/03 proved to be extremely useful. In a number of experiments, crystal penetrating cryoprotectants like glycerol or sugars had heavily disturbed the crystal packing. An increase of the concentration of PEG or PEE precipitants used for crystallization partly worked when the crystals were just dipped into the cryo-solution, yet the reproducibility was poor. Longer incubation times caused split diffraction patterns, and serial soaks or equilibration of the crystals via vapor diffusion completely destroyed diffraction. Only a washing step with PFO-X 125/03 allowed reproducible freezing of the crystals without disturbance of the crystal lattice.

The reproducibility of crystals suitable for structure determination was low. About 6 mg pure protein—the yield of one protein purification starting from approximately 20 g P. stutzeri cells (wet weight)—provided around 60 suitable crystals on the basis of visual inspection of their size and morphology. After prescreening for diffraction quality, two to three high-quality candidates were usually subjected to data collection which was only feasible with synchrotron radiation.

Discussion

Protein purification, choice of detergent, and crystallization method as a system in motion

Although the very first preparation of cbb3-CcO already yielded beautifully looking crystals that caused high expectations, the search for conditions allowing structure determination developed into a stony journey over nearly 10 years (summarized in a linear nearly chronologic manner in Fig. 5). The crystallization of cbb3-CcO exemplarily highlights major obstacles in IMP crystallography, their interdependence and possible methods for problem solving.

Membrane protein purification and crystallization are highly interdependent. The purification strategy, the column matrices applied, and the detergent used for protein preparation are of fundamental importance for the crystallization success and require a careful attunement of all operations involved in the process. For cbb3-CcO, the elaborated purification procedure not only ensured the removal of other proteins present in the cell membrane but also facilitated the separation of the isoenzymes and the adjustment of a favorable lipid content.

The complete separation of the isoenzymes (which share an overall sequence identity of 79%) could be neither achieved by IMAC with 200 mM NaCl included in the buffers nor by IEC or chromatofocusing. The omission of NaCl from the gradient buffers on the IMAC column represented the only problem-solving approach and was a major achievement concerning homogeneity of the protein preparation. However, we cannot explain which separation principle led to the partitioning of the isoenzymes. Potentially, the decrease of the ionic strength attained during the IMAC column run caused a decrease of hydrophobic interactions between cbb3-CcO complexes and, therefore, altered the elution behavior on this column.

As shown for other IMPs, besides preservation of structural and functional integrity,31 the lipids present in IMP preparations may play an important role in the formation of the crystal lattice. In some cases, the lipid content was shown to correlate with crystallizability and even formation of particular crystal forms by influencing crystal packing and, consequently, also the resulting diffraction resolution limit.32,33 Furthermore, it was found that the presence of lipids can restrict great conformational freedom, a factor potentially preventing crystallization.34 Although cbb3-CcO crystallized even with an extremely high content of approximately 80 lipids per protein complex, controlled delipidation was essential to obtain high quality crystals. Like for GlpT and LacY of E. coli,32,33 a specific optimal lipid content (here ∼12 lipids per cbb3-CcO) promoted the growth of crystals suitable for structure determination. Further lipid removal did not negatively influence the diffraction resolution limit, however, notably decreased the number of crystals obtained, suggesting a partially lipid dependent promotion of crystal formation.

For the purification and crystallization of membrane proteins, the choice of the detergent was already shown to be of highest importance.29,32,33,35 Apart from concentration dependent detergent phase phenomena influencing nucleation, each IMP seems to have a selected detergent concentration range favoring crystallization.1 Therefore, the careful choice of suitable detergents at appropriate concentrations is indispensable. During the crystallization of cbb3-CcO, the essential impact of the stereochemistry of the detergent (α-DDM vs. β-DDM) and of detergent mixtures which have to be in a precisely defined ratio became particularly evident.

A closer look at crystal packing [Fig. 4(A)] illustrates that the radius of the detergent belt could have significant impact on the formation of crystal contacts between the loops of individual CcoP subunits within the rather dense arrangement of cbb3-CcO complexes. The constitution of a tetrameric assembly connecting the four cbb3-CcO complexes in the asymmetric unit is established by linking the periplasmic parts of CcoP and is critically influenced by K3Fe(CN)6 [Fig. 4(B)]. This tetrameric core is surrounded by further tetramers which are essentially connected by two cytoplasmic loops and periplasmic parts of CcoP. Obviously, the described interface of the crystal contacts could be influenced by the micelle radius spacing the protein complexes.

The determined micelle size for DS of 7–10.5 kDa36 represents a relatively small value that, presumably, significantly contributes to the nature of the mixed micelle formed by the three different detergents in use for cbb3-CcO crystallization. Moreover, between α-and β-DDM significant differences in micellar shape (spherical vs. oblate ellipsoid), micellar radius (24 vs. 34.4 Å), and aggregation number (75 vs. 132) were reported.37 These features could explain the differences in crystal diffraction properties depending on the isomeric form of the maltoside used as well as the necessity of a defined ratio of maltoside to DS. The careful fine tuning of these properties may have tailored the resulting micelle in a way that it allowed specific and stable crystal contacts.

The exchange of β-maltoside for the α-isomer caused crystallization in a different crystal form. At later stages of fine tuning, variations in the composition of mixtures involving the three detergents α-DDM, α-UDM, and α-DM did not alter the crystal form yet spot profile, mosaicity, anisotropy, and resolution limit varied substantially. This observation emphasizes the importance of shape and size of the micelle. Surprisingly, even the addition of a detergent far below its CMC could drastically disturb the crystal packing. In the case presented here, α-DM at a concentration of 0.018% frequently caused the formation of multiple lattices.

Apart from that, in contrast to n-octyl-β-d-glucoside (OG), which forms small micelles of 25 kDa and is often used in membrane protein crystallization to potentially allow a higher number of contacts between protein molecules, DS seems to be of a milder nature for cbb3-CcO. While detergent exchange to OG caused dissociation of cbb3-CcO subunits (data not shown), preparation of cbb3-CcO in DS did not lead to destabilization. The stabilizing effect of sucrose itself on protein structures might represent the basis of these favorable properties of the sucrose monoester detergent.36

Protein homogeneity, micelle composition, and the precipitant are accepted as crucial factors for protein crystallization. For cbb3-CcO, also the crystallization method turned out to be very critical. After focusing on microbatch under oil for several years, the final breakthrough came with the shift back to vapor diffusion. Only then, crystals grew suitable for structure determination while crystals with the same unit cell parameters grown in comparable conditions in microbatch always showed highly anisotropic diffraction patterns.

Crystallization success was also influenced by individual factors rather found by chance. The addition of cytochrome c, which was not present in the crystalline cbb3-CcO, and of K3Fe(CN)6 are worth to be mentioned here.

Although the crystallization process revealed a number of factors beneficial throughout all stages of crystallization development (after leaving the initial set up20 behind), repeated crystallization screening was necessary after introduction of changes into the preparation protocol. While variations concerning lipid content and detergent type caused the previously best combinations of salt and precipitant to produce only moderate results, other crystallization condition proved successful. In turn, changed crystallization conditions also required the re-evaluation of protein preparation steps as in the case of the IEF, which was eventually omitted but had been useful for several years before establishing the final crystallization conditions.

One of the crucial lessons taken from this work is to remain open and flexible concerning every aspect of the preparation and crystallization set up. Regular revisits of already tried and possibly discarded options during advancing stages of method development may increase the amount of work yet also the chance of success. Attentive monitoring of the effects, which any change in conditions may cause on all other preparation levels, is an essential prerequisite to draw correct conclusions for further method development.

Materials and Methods

Membrane preparation

Cultivation of P. stutzeri ZoBell was carried out under microaerobic conditions largely as previously published.20 The trace element content of the medium was increased to FeCl3 · 6H2O 32 mg/L, NH4NO3 1.6 mg/L, KBr 22 mg/L, MnCl2 · 2H2O 20 mg/L, and ZnCl2 25 mg/L.

Membranes from P. stutzeri ZoBell were prepared as was previously described.20 An additional washing step in 20 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM EDTA was introduced and was followed by centrifugation at 1,45,000g at 4°C for 2.5 hr. The resulting pellet fraction was re-suspended in the same buffer supplemented with 13% (w/v) glycerol, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Solubilization and protein purification

Membranes were diluted to a final protein concentration of 3 mg/mL with 20 mM Tris/HCl pH7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 12% (w/v) glycerol, 0.1 mg/mL melatonin, approximately 1 mM Pefabloc, and solubilized for 5 minutes on ice with 2.5 mg β-DDM per mg of membrane protein. After centrifugation for 1 hr at 1,45,000g at 4°C, the resulting supernatant was applied to a Q Sepharose HP (GE Healthcare) column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10% (w/v) glycerol, 0.1 mg/mL melatonin, and 0.02% β-DDM. A linear gradient from 50 to 400 mM NaCl in equilibration buffer over 12 column volumes (CV) was applied and the buffer of cbb3-CcO containing fractions was exchanged against Polybuffer™ 74 (GE Healthcare) before application of the protein to a Polybuffer™ Exchanger 94 chromatofocusing column (GE Healthcare). A gradient from pH 7 to 4 was generated using Polybuffer™ 74 at pH 4 (supplemented with 0.02% β-DDM and 0.1 mg/mL melatonin) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cbb3-CcO containing eluate was supplemented with 50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5 and directly applied to a 30 mL Cu2+-loaded IMAC column (Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow; GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 0.02% β-DDM. After washing with 3 CV equilibration buffer, a linear gradient from 0 to 2.5 mM imidazole in 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.02% β-DDM over 2.9 CV was applied. Within this gradient, a first peak of cbb3-CcO eluted that was discarded and the imidazole concentration was ramped to 9.8 mM thereafter. Two cbb3-CcO peaks eluted shortly after one another and only the second peak was collected for further purification. The protein was supplemented with 50 mM NaCl and 0.5 mM EDTA and further purified over the final 15 mL Q Sepharose HP column, which was step eluted with 150 mM NaCl in 20 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, and 0.02% β-DDM. For detergent exchange, the protein was concentrated, desalted over a NAP™ 5 column (GE Healthcare) and subjected to a DEAE Sepharose FF (GE Healthcare) column run as described.14 The protein was finally concentrated in Centrisart1 devices (Sartorius) with a membrane cut off of 100 kDa. The NaCl concentration in the eluted sample was lowered to 100 mM by dilution with column equilibration buffer.

Isoelectric focusing

The protein resulting from one preparation was desalted over a NAP™ 5 column, concentrated to approximately 1 mL and applied to a preparative IEF gel with 50 mL bed volume. The gel matrix was prepared from 2 g Sephadex G-75 (GE Healthcare), 1 mL SERVALYT 3–7 (40% w/v; SERVA), and 49 mL water with, for example, 0.02% β-DDM or any other maltoside of choice at appropriate concentration before evaporation of 40% water at 60°C. On average, the gel run took 15 hours at 4 W and 4°C. The cbb3-CcO containing gel area of interest was cut, the protein eluted with 500 mM NaCl in 20 mM Tris pH 7.5 and the detergent of choice before concentration and buffer exchange over a NAP™ 5 column.

Crystallization and X-ray diffraction

For microbatch under oil, the protein drops of 0.35 µL were set in 96 well Imp@ct plates (Hampton Research), mixed with the same volume of crystallization solution and covered with a layer of 20 µL paraffin oil (BDH Laboratory Supplies; density 0.818–0.875 g/mL at 20°C) per well.

Vapor diffusion was carried out in 96 well sitting drop trays with conical flat bottom wells (Corning) by mixing 0.5 µL protein with an equal amount of reservoir solution.14

For the final crystallization conditions in PEE 15/04, ammonium formate and ammonium tartrate,14 both techniques required a protein concentration of approximately 16 mg/mL and the trays were incubated at 21°C. In microbatch set up, 38%–40.5% (w/v) PEE 15/04 as precipitant were needed to crystallize the protein, whereas about 10% less were necessary in vapor diffusion.

The crystals were fished, washed in PFO-X125/03, mounted in cryo-loops and flash frozen using liquid nitrogen.

Crystals were frequently measured at the beamlines ID14-1, ID14-4, ID23, ID29, and BM14U at ESRF, Grenoble/France as well as at PXII at the SLS, Villingen/Switzerland. Data analysis was done as previously published.14

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff at the beamlines at ESRF/Grenoble and SLS/Villigen for excellent support during X-ray diffraction experiments, Drs. Igor D'Angelo, Christian Biertümpfel, Marc Böhm, José Marquez, Arthur Oubrie, Chitra Rajendran, Sabrina Schulze, Vasundra Srinivasan, Anke Terwisscha von Scheltinga, and Prof. Jari Ylänne for synchrotron trips. We gratefully acknowledge Hao Xie for all experiments concerning sequence information, Dr. Eberhard Warkentin for the preparation of figures and Dr. Julian D. Langer for the peptide mass fingerprinting experiments and subsequent analyses. Prof. Carola Hunte, Drs. Peter-Thomas Naumann and Christoph Reinhart supported this work with fruitful discussions. We thank Dr. Chunli Zhang and Sebastian Gemeinhardt for critically reading the manuscript at hand and Dr. Robert S. Pitcher for his constant openness to discussion on issues involved in this project. Furthermore, we thank the Cluster of Excellence “Macromolecular Complexes” in Frankfurt and the Max Planck Society for financial support.

The authors are especially grateful to late Prof. Matti Saraste who initiated this project. As a great scientist and a very empathic person, he mentored, supported and encouraged the first author during her very first steps in membrane protein crystallography.

References

- 1.Wiener MC. A pedestrian guide to membrane protein crystallization. Methods. 2004;34:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landau EM, Rosenbusch JP. Lipidic cubic phases: a novel concept for the crystallization of membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14532–14535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadsten P, Wöhri AB, Snijders A, Katona G, Gardiner AT, Cogdell RJ, Neutze R, Engström S. Lipidic sponge phase crystallization of membrane proteins. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faham S, Bowie JU. Bicelle crystallization: a new method for crystallizing membrane proteins yields a monomeric bacteriorhodopsin structure. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:1–6. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preisig O, Anthamatten D, Hennecke H. Genes for a microaerobically induced oxidase complex in Bradyrhizobium japonicum are essential for nitrogen-fixing endosymbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3309–3313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preisig O, Zufferey R, Thöny-Meyer L, Appleby A, Hennecke H. A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bact. 1996;178:1532–1538. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1532-1538.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myllykallio H, Liebl U. Dual role for cytochrome cbb3 oxidase in clinically relevant proteobacteria? Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:542–543. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)91831-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh JI, Kaplan S. Redox signalling: globalization of gene expression. EMBO J. 2000;19:4237–4247. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosseau C, Batut J. Genomics of the ccoNOQP-encoded cbb3 oxidase complex in bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 2004;181:89–96. doi: 10.1007/s00203-003-0641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comolli JC, Donohue TJ. Differences in two Pseudomonas aeruginosa cbb3 cytochrome oxidases. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1193–1203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma V, Puustinen A, Wikström M, Laakkonen L. Sequence analysis of the cbb3 oxidase and an atomic model of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides enzyme. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5754–5765. doi: 10.1021/bi060169a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemp J, Han H, Roh JH, Kaplan S, Martinez TJ, Gennis RB. Comparative genomics and site-directed mutagenesis support the existence of only one input channel for protons in the C-family (cbb3 oxidase) of heme-copper oxygen reductases. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9963–9972. doi: 10.1021/bi700659y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rauhamäki V, Baumann M, Soliymani R, Puustinen A, Wikström M. Identification of a histidine-tyrosine cross-link in the active site of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16135–16140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606254103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buschmann S, Warkentin E, Xie H, Langer J, Ermler U, Michel H. The structure of cbb3 cytochrome oxidase provides insights into proton pumping. Science. 2010;329:327–330. doi: 10.1126/science.1187303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hino T, Matsumoto Y, Nagano S, Sugimoto H, Fukumori Y, Murata T, Iwata S, Shiro Y. Structural basis of biological N2O generation by bacterial nitric oxide reductase. Science. 2010;330:1666–1670. doi: 10.1126/science.1195591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oost van der J, DeBoer APN, Gier de JWL, Zumpft WG, Stouthamer AH, Spanning van RVM. The heme copper oxidase family consists of three distinct types of terminal oxidases and is related to nitric oxide reductase. FEMS. 1994;121:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forte E, Urbani A, Saraste M, Sarti P, Brunori M, Giuffre A. The cytochrome cbb3 from Pseudomonas stutzeri displays nitric oxide reductase activity. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:6486–6490. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitcher RS, Cheesman MR, Watmough NJ. Molecular and spectroscopic analysis of the cytochrome cbb3 oxidase from Pseudomonas stutzeri. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31474–31483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitcher RS, Brittain T, Watmough NJ. Complex interactions of carbon monoxide with reduced cytochrome cbb3 oxidase from Pseudomonas stutzeri. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11263–11271. doi: 10.1021/bi0343469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urbani A, Gemeinhardt S, Warne A, Saraste M. Properties of the detergent solubilised cytochrome c oxidase (cytochrome cbb3) purified from Pseudomonas stutzeri. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rouser G, Fleischer S, Yamamoto A. Two dimensional thin layer chromatographic separation of polar lipids and determination of phospholipids by phosphorus analysis of spots. Lipids. 1970;5:494–496. doi: 10.1007/BF02531316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagow Von G, Schägger H. A practical guide to membrane protein purification. San Diego: Academic Press/Elsevier Science; 1994. Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunte C, Jagow Von G, Schägger H. A practical guide to membrane protein purification. 2nd. San Diego: Academic Press/Elsevier Science; 2003. Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobrynin K, Abdrakhmanova A, Richers S, Hunte C, Kerscher S, Brandt U. Characterization of two different acyl carrier proteins in complex I of Yarrowia lipolytica. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chayen NE, Stewart PDS, Maeder DL, Blow DM. An automated-system for microbatch protein crystallization and screening. J Appl Cryst. 1990;23:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chayen NE. Crystallization with oils: a new dimension in macromolecular crystal growth. J Cryst Growth. 1999;196:434–441. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan Y, Yang J, Dou Y, Chen M, Ping S, Peng J, Lu W, Zhang W, Yao Z, Li H, Liu W, He S, Geng L, Zhang X, Yang F, Yu H, Zhan Y, Li D, Lin Z, Wang Y, Elmerich C, Lin M, Jin O. Nitrogen fixation island and rhizosphere competence traits in the genome of root-associated Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7564–7569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801093105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gulick A, Horswill AR, Thoden JB, Escalante-Semerena J, Rayment I. Pentaerythritol propoxylate: a new crystallization agent and cryoprotectant induces crystal growth of 2-methylcitrate dehydratase. Acta Cryst D. 2002;58:306–309. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901018832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Screpanti E, Padan E, Rimon A, Michel H, Hunte C. Crucial steps in the structure determination of the Na+/H+ antiporter NhaA in its native conformation. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McPherson A. A comparison of salts for the crystallization of macromolecules. Protein Sci. 2001;10:418–422. doi: 10.1110/ps.32001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palsdottir H, Hunte C. Lipids in membrane protein structures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666:2–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemieux MJ, Song J, Kim MJ, Huang Y, Villa A, Auer M, Li XD, Wang DN. Three-dimensional crystallization of the Escherichia coli glycerol-3-phosphate transporter: a member of the major facilitator superfamily. Protein Sci. 2006;12:2748–2756. doi: 10.1110/ps.03276603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guan L, Smirnova IN, Verner G, Nagamori S, Kaback R. Manipulating phospholids for crystallization of a membrane transport protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1723–1726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510922103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H, Genji K, Smith JL, Kramer WA. A defined protein-detergent-lipid complex for crystallization of integral membrane proteins: The cytochrome b6f complex of oxygenic photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5160–5163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931431100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostermeier C, Harrenga A, Ermler U, Michel H. Structure at 2.7 Å resolution of the Paracoccus denitrificans two-subunit cytochrome c oxidase complexed with an antibody Fv fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10547–10553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makino S, Ogimoto S, Koga S. Sucrose monoesters of fatty acids: their properties and interaction with protein. Agric Biol Chem. 1982;47:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagliano C, Barera S, Chimirri F, Sacarro G, Barber J. Comparison of the α and β isomeric forms of the detergent n-dodecyl-D-maltoside for solubilizing photosynthetic complexes from pea thylakoid membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:1506–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]