A 93-year-old man was referred to a geriatric day hospital for assessment of falls, mobility, mood and function. A month earlier, he had presented to a local hospital following a fall that resulted in lacerations to his right arm. At that time, he reported worsening balance and frequent falls over several months, as well as low mood. Comorbidities included coronary artery disease with previous myocardial infarction and angioplasty 15 years earlier, carotid endarterectomy, hypertension, vertebral fractures, bullous pemphigoid and osteoporosis. Most instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., laundry, food preparation) were managed by staff at his retirement home. The patient maintained responsibility for taking his medications from pharmacy-prepared blister packs; his daughter described his compliance as good (see Box 1 for the list of medications).

Box 1: Initial list of medications.

| Medication, dosage | Reason for use, if known |

|---|---|

| Telmisartan 80 mg/d | CAD/MI (15 yr earlier) |

| Metoprolol 50 mg/d | CAD/MI (15 yr earlier) |

| Escitalopram 10 mg/d | Depression |

| Lorazepam 1 mg at bedtime as needed | Insomnia |

| Tamsulosin CR 0.4 mg at bedtime | Nocturia |

| Pantoprazole 40 mg twice daily | Gastrointestinal bleed (7 mo earlier) |

| Prednisone 5 mg twice daily | Bullous pemphigoid |

| Loperamide 1 mg as needed | Diarrhea |

Note: CAD = coronary artery disease, CR = controlled release, MI = myocardial infarction.

At presentation, additional problems of low blood pressure, dizziness, daytime sedation, low energy, diarrhea, vitamin deficiencies and hyponatremia were highlighted. The patient accepted a 12-week admission to the geriatric day hospital, and twice-weekly transportation was organized.

At his first few visits, orthostatic hypotension was noted (on 2 occasions, his blood pressure dropped from 115/55 mm Hg supine to 83/42 mm Hg standing, and from 127/70 mm Hg supine to 97/64 mm Hg standing) and was associated with dizziness when the patient stood up quickly or bent forward. He described sleep as good, although he reported taking 1.5–2 hours to fall asleep and a need to go to the bathroom twice nightly. He had little energy and napped up to 6 hours daily. Low energy and anhedonia meant he had given up several activities, and he had lost weight because of a poor appetite. Despite this, he felt he was not depressed. He reported bouts of diarrhea every 4–5 days starting in the last 2–3 months and 4–5 episodes of fecal incontinence over this period. Blood work showed vitamin B12 deficiency (189 pmol/L; sufficient > 220 pmol/L), vitamin D deficiency (49 nmol/L; sufficient > 76 nmol/L), hyponatremia (sodium 132 mmol/L; normal 135–145 mmol/L) and a slightly low calcium level of 2.15 mmol/L (normal 2.20–2.65 mmol/L). Creatinine clearance was calculated as 30 mL/min (Cockroft–Gault equation with adjusted body weight).

An interprofessional care plan was developed to address these issues. The pharmacist at the geriatric day hospital conducted a medication assessment, which included a 45-minute comprehensive interview with the patient and chart review. Each medication was assessed for indication, effectiveness, safety, compliance and patient understanding.1 Results of the initial medication assessment are outlined in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.130523/-/DC1). Signs and symptoms were assessed to determine potential drug-related causes.2 The complete medication assessment and care plan are outlined in Box 2. Throughout the admission, several changes were made to the patient’s medications (Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.130523/-/DC1).

Box 2: Complete assessment of medications for potential drug-related problems and resulting medication care plan.

| Potential drug-related problem | Action plan | Monitoring (by team) |

|---|---|---|

Diarrhea and hyponatremia

|

|

|

Orthostatic hypotension and dizziness

|

|

|

Frequent falls and daytime fatigue and sleeping

|

Decrease lorazepam to 0.5 mg at bedtime for 2 wk, then to 0.25 mg at bedtime for 2 wk, then stop |

|

| Vitamin D deficiency (49 nmol/L) and increased risk of falls | Start vitamin D 1000 IU/d | |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency (189 pmol/L) | Start vitamin B12 1000 μg/d | |

| Risk of adverse effects with prednisone | Consider slowly tapering prednisone dose (e.g., from 5 mg twice daily to 7.5 mg once daily for 1 mo, then to 5 mg once daily for 1 mo, and so on) |

Note: MI = myocardial infarction, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

The patient participated in balance, strength and mobility exercises with the hospital’s physiotherapist, focusing particularly on gait training with and without aids. His Berg Balance score improved from 42 to 54 out of 56 (a 12-point improvement is associated with a clinically significant reduction in risk of falls and improvement in function).3,4 His 6-minute walk test improved from 240 m to 390 m (a 50-m improvement is estimated to be clinically significant for most patients).5 His confidence in climbing stairs improved substantially. The patient received fall-prevention education from the occupational therapist one on one and in group classes. No further falls were reported during the 12-week admission period.

The patient’s mood improved following supportive counselling from the social worker and increased social interaction. His appetite and energy levels increased, and he resumed old activities. His diarrhea resolved. His blood pressure improved, and he no longer had dizziness; the nurse provided strategies to manage symptoms of orthostatic hypotension should they occur again. A final medication list is presented in Box 3.

Box 3: Medication schedule at discharge.

In the morning

Telmisartan 20 mg

Prednisone 5 mg

Vitamin D 1000 IU

Vitamin B12 1000 μg

Psyllium 15 mL

At supper

Prednisone 5 mg

At bedtime

Tamsulosin CR 0.4 mg

CR = controlled release.

Discussion

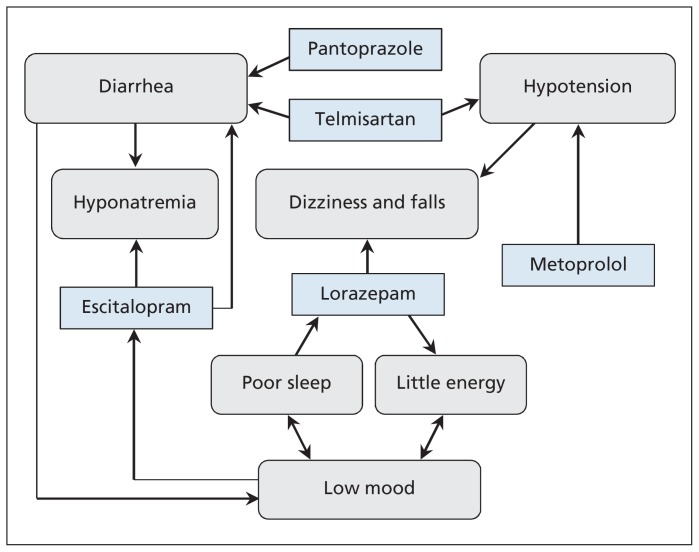

As people reach their 80s and 90s, regular reviews of their medications are important to assess ongoing indications and potential adverse effects and to minimize pill burden. A new symptom or problem may be an adverse effect of one or more medications.6 Recognizing and addressing the contribution of a drug to a symptom may prevent prescribing cascades, whereby new drugs are given to treat an adverse effect instead of stopping the drug causing the effect. Reviewing the indications and evidence for continuing long-standing drugs, and weighing the benefits against the risk of adverse events, can reduce the number of medications a patient is taking. Figure 1 illustrates the interplay among the patient’s medications and the possible effects on his diarrhea, dizziness and risk of falls.

Figure 1:

Interplay among the medications of a 93-year-old man referred to a geriatric day hospital and their possible effects on his diarrhea, dizziness and risk of falls.

Diarrhea and hyponatremia

Diarrhea is a common problem for older people and can have a strong negative impact on their quality of life and function.7 Antibiotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), proton pump inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers have all been shown to increase the risk of diarrhea in older patients.7 Hyponatremia has also been associated with several SSRIs, a problem that occurs predominantly in older people.8

The onset of our patient’s diarrhea was consistent with the initiation of escitalopram for the treatment of depression about 2–3 months before his admission to the geriatric day hospital. Hyponatremia may have been caused or worsened by the escitalopram use, or exacerbated by the diarrhea. In light of these safety concerns, the drug was tapered and eventually stopped, during which the patient was monitored for mood changes and signs of adverse withdrawal events, in this case SSRI discontinuation syndrome (e.g., anxiety, insomnia, irritability, headache, dizziness and fatigue).

High-dose pantoprazole treatment was being taken following a gastrointestinal bleed secondary to naproxen use 7 months before presentation. Treatment with a proton pump inhibitor for this indication usually does not exceed 8 weeks and need not be lifelong if the offending nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is stopped.9 Naproxen had been stopped following the gastrointestinal bleed, and the patient had no ongoing reflux or symptoms of a peptic ulcer. Evidence shows that corticosteroids do not increase the risk of peptic ulceration unless NSAIDs are being taken concomitantly.10 Thus, pantoprazole was considered to be no longer necessary and was switched to low-dose rabeprazole (the only low-dose proton pump inhibitor covered by the provincial formulary without a special code), which was then tapered and eventually stopped. Two minor instances of expected rebound heartburn11 were managed with calcium carbonate.

Telmisartan may have also been contributing to the patient’s diarrhea. Given the hypotension that was observed (discussed in the next section), the dose was reduced.

Following these medication changes, the patient’s bowel symptoms improved to the point where he no longer reported diarrhea or episodes of fecal incontinence and loperamide was no longer needed. Psyllium was started to provide bulk for occasional loose stools. The patient reported normal bowel movements by the time of discharge. His mood was stable during the tapering of the escitalopram and improved during his visits to the geriatric day hospital, even after stopping the escitalopram.

Hypotension, dizziness and falls

Both metoprolol and telmisartan may have been contributing to the patient’s hypotension, dizziness and falls. The hypotension may have been a major factor contributing to his falls, but it also was of concern because low systolic pressure is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality among patients over 85.12 A target range of 120/60 mm Hg to 150/90 mm Hg was established to guide treatment.

Because the patient’s myocardial infarction had occurred 15 years earlier, without subsequent angina or other compelling indications for β-blocker therapy, such as heart failure or atrial fibrillation, the benefit of continuing the metoprolol treatment was questioned. The optimal duration of β-blocker therapy following myocardial infarction is not well established, because there is limited evidence to guide recommendations beyond 2 years of treatment. A large meta-analysis investigating β-blocker use for an average of 1.4 years after myocardial infarction reported a significant reduction in mortality over this time (number needed to treat for 2 yr to prevent 1 death was 42).13 A more recent observational study followed a cohort of patients for an average of 44 months after myocardial infarction. Beyond 2 years of follow-up, no significant difference in cardiovascular-related death, nonfatal myocardial infarction or nonfatal stroke was seen among patients taking a β-blocker compared with those not taking one.14

Because of safety concerns regarding hypotension (with attendant cardiovascular risks), dizziness and falls, we decided to taper and stop the metoprolol. Following its discontinuation, we monitored the patient’s blood pressure and heart rate and watched for any rebound angina and common adverse withdrawal events associated with β-blockers (e.g., tachycardia).15 The patient did not experience rebound angina or tachycardia; however, his blood pressure was still below target, so we gradually decreased the dose of telmisartan from 80 to 20 mg/d, also taking into account the drug’s possible contribution to diarrhea. The patient’s blood pressure subsequently rose to within target range (e.g., 132/70 mm Hg) by discharge.

Because of the increased risk of injurious falls with benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling people over 80 years old,16 we identified lorazepam as a possible contributor to the patient’s falls and dizziness as well as his daytime sedation. He had started taking lorazepam 1 mg at bedtime several months before coming to the geriatric day hospital and noted worsening balance and more falls over this time. We slowly tapered17 and stopped the lorazepam over 7 weeks, with no worsening of his sleep, no rebound insomnia or adverse withdrawal events reported.

Vitamin D supplementation was started, given the patient’s deficiency and the potential for vitamin D to reduce the risk of falls.18

With our interprofessional approach to falls prevention and these medication changes, the patient’s dizziness resolved and no further falls were reported.

Osteoporosis

Long-term adverse effects of corticosteroids are well-documented and include osteoporosis and diabetes.19 It was not clear whether the patient still needed daily prednisone treatment to manage his bullous pemphigoid. However, following a trial decrease in the dose from 5 mg twice daily to 7.5 mg once daily, the patient reported a worsening of his symptoms and marked itchiness of his back; the original dosage was reinstated. Treatment with a bisphosphonate was considered owing to the long-term corticosteroid use; however, it was not started because of the patient’s low renal function and advanced age; this decision was deferred for discussion with his family physician. Although vitamin D supplementation was started, calcium supplementation was not required because his dietary calcium intake was about 1000 mg/d.

Conclusion

This patient’s case underscores the importance of assessing drug-related causes of symptoms in older patients and whether the causative agent is still required. Few drug trials include participants in their 80s or 90s, and given pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes in older people, little is known about the safety and effectiveness of medications in this patient group. Slow tapering with careful monitoring can help to identify medications that are causing adverse effects as well as medications that are still needed for symptom relief.

A pharmacist and physician, working together with support and interventions from other members of an interprofessional team, can make an important difference in the quality of life of older patients by reassessing their medications to ensure they are safe and effective. In the case of our patient, his low energy, diarrhea, dizziness and falls were severely affecting his quality of life. Three months later, he had more energy, improved appetite, normal bowel function, improved balance and mobility, no dizziness and no further falls.

Resources for clinicians.

Tisdale JE, Miller DA, editors. Drug-induced diseases: prevention, detection and management. 2nd ed. Bethesda (MD): American Society of Health System Pharmacists; 2010.

Alexander GC, Sayla MA, Holmes HM, et al. Prioritizing and stopping prescription medications. CMAJ 2006;174:1083–4.

A practical guide to stopping medicines in older people. Best Pract J 2010;27:10–23.

Hajjar ER, Gray SL, Guay DR, et al. Geriatrics. In: Talbert RL, DiPiro JT, Matzke GR, editors. Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach. 8th ed. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill; 2011. Available: http://accesspharmacy.com/content.aspx?aid=7967419

Kwan D, Farrell B. Polypharmacy — optimizing medication use in elderly patients. Pharmacy Practice 2012;29:20–5.

An expanded version of this article is available as a tool to teach about interprofessional approaches to the management of polypharmacy (see Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.130523/-/DC1).

Key Points

All older people should have their medications reviewed regularly to assess ongoing indications and potential adverse effects and to minimize pill burden.

A new symptom or problem may be an adverse effect of one or more medications.

Age-appropriate evidence-based targets can help to determine the need for ongoing treatment.

Tapering of doses and discontinuation of medications can be considered to determine whether a drug is still required.

Supplementary Material

See also the practice article by Farrell and colleagues at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.122012 (Oct. 1 issue) and the commentary by Frank at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.131568 (page 407, this issue)

Footnotes

Competing interests: Barbara Farrell received an honorarium from the journal Pharmacy Practice for an article on polypharmacy; she also received an honorarium from RxFiles for preparing and presenting workshops on the management of polypharmacy. No competing interests were declared by Anne Monahan or Wade Thompson.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Barbara Farrell and Anne Monahan were the clinicians involved in the care of the patient. Wade Thompson prepared the initial draft of the manuscript and conducted relevant literature searches. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication.

This article is one of several prepared as part of a collaboration between the Geriatric Day Hospital of Bruyère Continuing Care, CMAJ, Canadian Family Physician and the Canadian Pharmacists Journal to assist clinicians in the prevention and management of polypharmacy when caring for older patients in their practices.

References

- 1.Cipolle RD, Strand LM, Morley PC, editors. Pharmaceutical care practice: the clinician’s guide. 2nd ed New York (NY): McGraw-Hill; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winslade N, Bajcar J. Therapeutic thought process algorithm. Ottawa (ON): National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities; 1995. Available: www.napra.org/Content_Files/Files/algorithm.pdf (accessed 2012 Dec. 3). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shumway-Cook A, Baldwin M, Polissar N, et al. Predicting the probability of falls in community-dwelling older adults. Phys Ther 1997;77:812–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conradsson M, Lundin-Olsson L, Lindelof N, et al. Berg balance scale: intra-rater test–retest reliability among older people dependent in activities of daily living and living in residential care facilities. Phys Ther 2007;87:1155–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perera S, Mody S, Woodman R, et al. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:743–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salazar JA, Poon I, Nair M. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly: expect the unexpected, think the unthinkable. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2007;6:695–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Vitale D, et al. The prevalence of diarrhea and its association with drug use in elderly outpatients: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2816–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacob S, Spinler SA. Hyponatremia associated with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in older adults. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1618–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramakrishnan K, Salinas RC. Peptic ulcer disease. Am Fam Physician 2007;76:1005–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conn HO, Poynard T. Corticosteroids and peptic ulcer: meta-analysis of adverse events during steroid therapy. J Intern Med 1994;236:619–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reimer C, Søndergaard B, Hilsted L, et al. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology 2009;137:80–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molander L, Lovheim H, Norman T, et al. Lower systolic blood pressure is associated with greater mortality in people aged 85 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1853–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freemantle N, Cleland J, Young P, et al. Beta blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. BMJ 1999;318:1730–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bangalore S, Steg G, Deedwania P, et al. Beta blocker use and clinical outcomes in stable outpatients with and without coronary artery disease. JAMA 2012;308:1340–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graves T, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, et al. Adverse events after discontinuing medications in elderly outpatients. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:2205–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pariente A, Dartigues JF, Benichou J, et al. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging 2008; 25:61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen C, Farrell B, Ward N, et al. Stopping benzodiazepines: an interdisciplinary approach at a geriatric day hospital. Can Pharm J 2010;143:286–95 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Staehelin HB, et al. Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2009; 339:b3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanbury RM, Graham EM. Systemic corticosteroid therapy — side effects and their management. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82:704–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.