Abstract

In vitro differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) promotes the understanding of the mechanism of spermatogenesis. The purpose of this study was to isolate spermatogonial stem cell-like cells from murine testicular tissue, which then were induced into haploid germ cells by retinoic acid (RA). The spermatogonial stem cell-like cells were purified and enriched by a two-step plating method based on different adherence velocities of SSCs and somatic cells. Cell colonies were present after culture in M1-medium for 3 days. Through alkaline phosphatase, RT-PCR and indirect immunofluorescence cell analysis, cell colonies were shown to be SSCs. Subsequently, cell colonies of SSCs were cultured in M2-medium containing RA for 2 days. Then the cell colonies of SSCs were again cultured in M1-medium for 6–8 days, RT-PCR and indirect immunofluorescence cell analysis were chosen to detect haploid male germ cells. It could be demonstrated that 10−7 mol l−1 of RA effectively induced the SSCs into haploid male germ cells in vitro.

Keywords: Differentiation, Spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), Murine, Retinoic acid

Introduction

In male mammals, the production of sperm is a continuous process supported by spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) (Aponte et al. 2005) originating from gonocytes. The maturation of SSCs starts when the gonocytes migrate to the genital ridges and are enclosed by Sertoli cells (de Rooij 2001). Recently, many researches have promoted the understanding spermatogonial cultivation, self-renewal and differentiation (Araki et al. 2010; Kanatsu-Shinohara et al. 2007; Kubota et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2003; Nagano et al. 1998; Nolte et al. 2010; Oatley et al. 2007).

Extensive work has been done on how SSCs commence differentiation. In recent years, some reports indicated that the differentiation of SSCs can be induced by the presence of certain nutrients such as retinoic acid (RA) or calcium alginate or by the co-culture with Sertoli cells. With respect to RA, recent data have suggested that RA signaling initiates meiosis in fetal mouse ovary and acts on germ cells to promote expression of Stra8 (Bowles et al. 2006; Koubova et al. 2006), which is a gene required for pre-meiotic DNA replication (Anderson et al. 2008). RA is a retinoids which can alter gene expression in testis (Clagett-Dame and DeLuca 2002), heart (Das et al. 2007), central nervous system (Kastner et al. 1995) craniofacial structures, limbs, brain, and eyes (Clagett-Dame and DeLuca 2002; Das et al. 2007; Kastner et al. 1995; Ross et al. 2000; Wolgemuth and Chung 2004; Zile 1998). Chung et al. (2005) reported that the lack of retinoic acid receptor α could lead to male sterility in mice as well as specific abnormalities in spermiogenesis (Chung et al. 2005). It has been proven that foetal cattle mGCs (male germ cells) were induced by RA to generate some elongated sperm-like cells (Dong et al. 2010). In addition, it was demonstrated that inhibiting the metabolism of vitamin A to generate RA is a new approach of male contraception (Hogarth et al. 2011).

Spermatogonial stem cells can support continuous spermatogenesis by their ability of self-renewal. As described previously, RA can induce differentiation of SSCs. However, the appropriate protocol to induce differentiation of mouse SSCs into haploid cells in vitro was not set up yet. In this study, the isolation and purification of SSCs from mice were studied. An appropriate protocol to induce the differentiation of SSCs into haploid cells in vitro was set up, which may provide a novel approach to study the mechanism of spermatogenesis and have a potential value to conserve threatened and endangered large animals.

Materials and methods

All chemical reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). The culture media, l-glutamine, nonessential amino acids and sera were obtained from Gibco/Invitrogen (Beijing, China), Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) or Hyclone (Logan, UT, USA) unless stated otherwise. EGF was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). All solutions were prepared using ultra-purified water supplied by a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Experimental animals

Mice aged 6 days were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of the Medical College of the Xi’an Jiaotong University for this study.

Isolation and purification of murine SSCs

The single cell suspensions from murine testis tissues were prepared by a two-step enzymatic digestion. The dispersed cells were filtrated with a 400-eyes mesh and washed twice with DMEM using 500×g centrifugation. The pellet was suspended in M1-medium (containing DMEM, 20 ng ml−1 EGF, 4 mol l−1l-glutamine, 1 % nonessential amino acids and 10 % FBS). The cells were cultured using a two-step differential plating process to separate the SSCs and Sertoli cells. Briefly, 106 cells per millilitre were cultured in 60-mm dishes for 12 h at 37 °C and 5 % CO2, and then the non-adhering cells (the majority of them were SSCs) and adhering cells (the majority of Sertoli cells) were transferred into a new plate to culture for further 4 h in the same condition, respectively. The suspended cells were collected and divided into two parts after cultivation for 3 days. One part of the cells was cultured in vitro as the control group. The other group was treated with 10−7 mol l−1 of RA (Dong et al. 2010). 5 × 104 SSCs per well were cultured in parallel in 48-well plates in M2-medium (containing DMEM, 4 mol l−1l-glutamine, 5 ng ml−1 EGF, 1 % BSA and 4 × 10−2 mg l−1 gentamicin, 10−7 mol l−1 RA) for 2 days. After that the cell colonies of SSCs were again cultured in M1-medium for further 6–8 days. The adhering cells (the majority of Sertoli cells) were cultured in M1-medium for 6 days. In all culture systems, half of the medium was changed every day. The cell suspension was placed into cell culture flasks and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified, 5 % CO2 and 95 % air atmosphere. The medium was changed every 2–3 days.

Alkaline phosphatase (AKP) assay

The mouse SSCs were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for detection of alkaline phosphatase (AKP) activity and then stained with NBT/BCIP AKP substrate. The staining reaction was stopped after incubation of 10–15 min in light by washing with PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline). The stained cells were observed and photographed under inverted phase contrast microscope (Nikon Imaging Sales Co Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Indirect immunofluorescence cell analysis

The above cells were identified via the CD9-marker—a marker for the spermatogonial stem cells (Abu Elhija et al. 2012). Protamine 1 (a marker for post-meiotic cells) was detected by indirect immunofluorescence staining (Abu Elhija et al. 2012). Briefly, the cells were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 15 min, and were rinsed triply in PBS with 0.1 % Tween-20. Then the cells were re-suspended in phosphate-buffered saline with bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA) over an hour at 37 °C. The rabbit anti-CD9 antibody (1:1000 in PBS, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was added to the solution for 12 h at 37 °C and then triply washed in PBS. The Cy3 AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (1:1000, Invitrogen, USA) was added and incubated for an hour at 37 °C. Finally, the cell suspension was incubated with Hoechst 33258 (1:800, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA USA) for 8 min to stain the nuclei of SSCs and Sertoli cells, then washed thrice with PBS and the cells were re-suspended in 0.5 ml PBS-BSA. The anti-protamine 1 antibody (1:1000 in PBS, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was added to the suspension of the RA treated group, for 12 h at 37 °C and then triply washed in PBS. DyLight 488 AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (1:1000 in PBS, Abcam) was added and incubated for an hour at 37 °C. Finally, the suspension was incubated with Hoechst 33258 (1:800) for 8 min to stain the nuclei of haploid male germ cells, washed thrice with PBS. Then the cells were re-suspended in 0.5 ml PBS-BSA. The fluorescence was monitored using a 580- and a 644-nm double band-pass filter by fluorescence microscope (Nikon Imaging Sales Co Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

RT-PCR

Total RNA of cells was extracted by the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). To generate the cDNA, the reverse transcription was carried out by using 1 μg total RNA and 0.2 μg oligo dT (20), adding DEPC treated water to 10 μl at 70 °C for 5 min, followed by 42 °C for 1 h. PCR was then utilized to analyze the expression of following genes: Ngn3 (GenBank No. NM_009719.6): Forward Primer: 5′-TTG GCA CTC AGC AAA CAG C-3′; Reverse Primer: 5′-TCC CTT TCC ACT AGC ACC C-3′ 467 bp; Oct4 (GenBank No. NM_013633.2): Forward Primer: 5′-CCC CAA TGC CGT GAA GTT-3′; Reverse Primer: 5′-GAA A GG TGT CCC TGT AGC C-3′ 556 bp; β-actin (GenBank No.NM_007393.3): Forward Primer: 5′-GCC TTC CTT CTT GGG TAT-3′; Reverse Primer: 5′- CCT TCA CCG TTC CAG TTT-3′ 549 bp; Integrin alpha 6 (GenBank No.NM_008397.3): Forward Primer: 5′-ATG ATG AAA GTC TCG TGC-3′; Reverse Primer: 5′-CAT AGC CAA ACG AGG AAG-3′, 222 bp; Integrin beta 1 (GenBank No. NM_010578.2): Forward Primer: 5′ TTG ATG AAT GAA ATG AGG AG 3′, Reverse Primer: 5′-TCC AGA TAT GCG TTG CTG-3′, 225 bp; Sycp3 (GenBank No. NM_011517.2): Forward Primer: 5′-TCA GAG CCA GAG AAT GAA AG-3′; Reverse Primer: 5′-CTG CTG AGT TTC CAT CAT AAC-3′, 163 bp; TH2B (GenBank No.NM_175663.1): Forward Primer: 5′- CGG TAA AGG GTG CTA CTA T-3′; Reverse Primer: 5′-CACTTGTTTCAGCACCTTA-3′, 137 bp. The DNA marker was DNA marker I (TianGen Co. Ltd., Beijing, China).

The PCR reaction system was constituted of 2.5 μl 10× reaction buffer (including Mg++) (pH 8.3), 2 μl dNTP (10 mM), 1 μl of each primer (1 μM) and 0.5 IU Taq DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), 1 μl template DNA and 17 μl DEPC water. The PCR products were separated by 1.2 % agarose gel electrophoresis. Negative controls included mock reverse transcription without RNA or PCR with DEPC-treated water. RNA from adult testis was used as positive control.

Results

Because of lack of unique markers of SSCs, a variety of methodologies was opted to demonstrate that the cell colonies we cultured were SSCs colonies. SSCs are round and can be stained by the alkaline phosphatase assay into bluish violet. The four characteristic genes (Oct4, Integrin alpha 6, Integrin beta 1, Ngn3) of germ cells were selected to identify the spermatogonial stem cells. It is commonly considered that As (a single) and Apr (a paired) spermatogonia have stem-cell properties. CD9 is considered as surface maker of spermatogonial stem cells. Haploid male germ cells are a type of post-meiotic cells, which express, both, Sycp3 and TH2B genes. Protamine 1 is the specific marker of post-meiotic cells.

Alkaline phosphatase (AKP) assay

Purified Sertoli cells were considered as the control group. The difference between the Sertoli cells and SSCs was the morphology. Purified SSC cells are round, they began to divide and proliferate for 2 days and cell colonies appeared on day 6 (Fig. 1). Stem cells can be stained into bluish violet by AKP staining. From both images in Fig. 2a, b, SSCs and Sertoli cells, were clearly different. SSCs were round and stained bluish violet, while Sertoli cells had an irregular form and were barely stained. The AKP assay together with the images of the cell colonies demonstrated that the colonies of the round cells could be considered as SSCs colonies.

Fig. 1.

The SSCs colonies at day 6 (×400)

Fig. 2.

Cell staining for alkaline phosphatase. SSCs are stained bluish violet, while Sertoli cells are barely stained: a Cells stained for alkaline phosphatase (×200). The arrows point to SSCs. b Sertoli cells stained for alkaline phosphatase (×200). The arrows point to the Sertoli cells

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

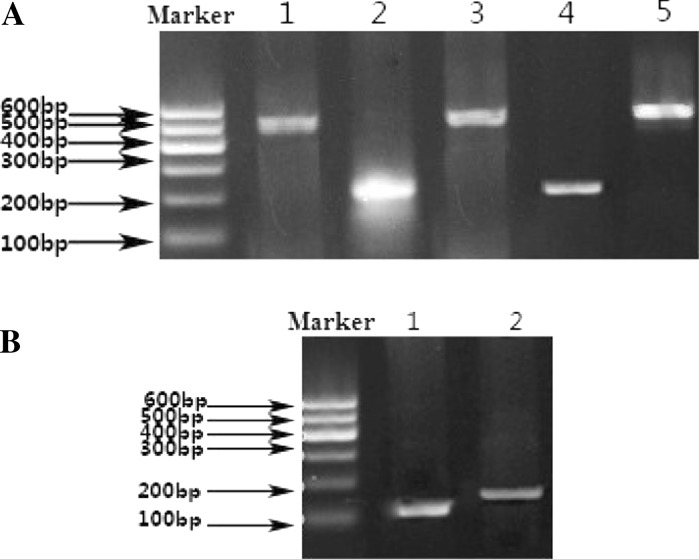

Some characteristic genes of germ cells are selected to identify the spermatogonial stem cells and haploid male germ cells. The Ngn3 gene is a typical gene of SSCs (Yoshida et al. 2004) and the Oct4 gene maintains pluripotency and self-renewal (Loh et al. 2006). The β-actin gene is a house-keeping gene of SSCs and Sertoli cells (Thellin et al. 1999). The Integrin alpha 6 and Integrin beta 1 genes are considered as surface markers of SSCs (Shinohara et al. 1999). The expression of Sycp3 and TH2B is related to differentiation of the spermatogonial stem cells into haploid male germ cells. From Fig. 3a, we can see that the SSCs expressed the four genes (Oct4, Integrin alpha 6, Integrin beta 1, Ngn3), and the house keeping gene, while Sertoli cells only expressed the house-keeping gene (β-actin). The RT-PCR analysis indicated different gene expression by SSCs and Sertoli cells. Thus, it was demonstrated that the cell colonies we cultured were SSCs.

Fig. 3.

RT-PCR analysis of SSCs (a) and of haploid male germ cells (b). a Four characteristic marker genes of SSCs are analyzed: lane 1: OCT4, lane 2: Integrin alpha 6, lane 3: β-actin, lane 4: Integrin beta 1, lane 5: Ngn 3. Sertoli cells served as control group for SSCs. They only expressed the β-actin gene (not shown). b Two characteristic genes of haploid male germ cells: lane 1: TH2B, lane 2: Scyp3. SSCs served as control group for haploid male germ cells. They did not express both genes (not shown)

The SSCs began to become meiotic and further differentiated into haploid male germ cells after induction with RA leading to the expression of Sycp3 and TH2B as shown in Fig. 3b. The control group for haploid male germ cells was SSCs which did not express both genes (not shown). Thus, it was obviously demonstrated that SSCs were induced to haploid male germ cells by RA.

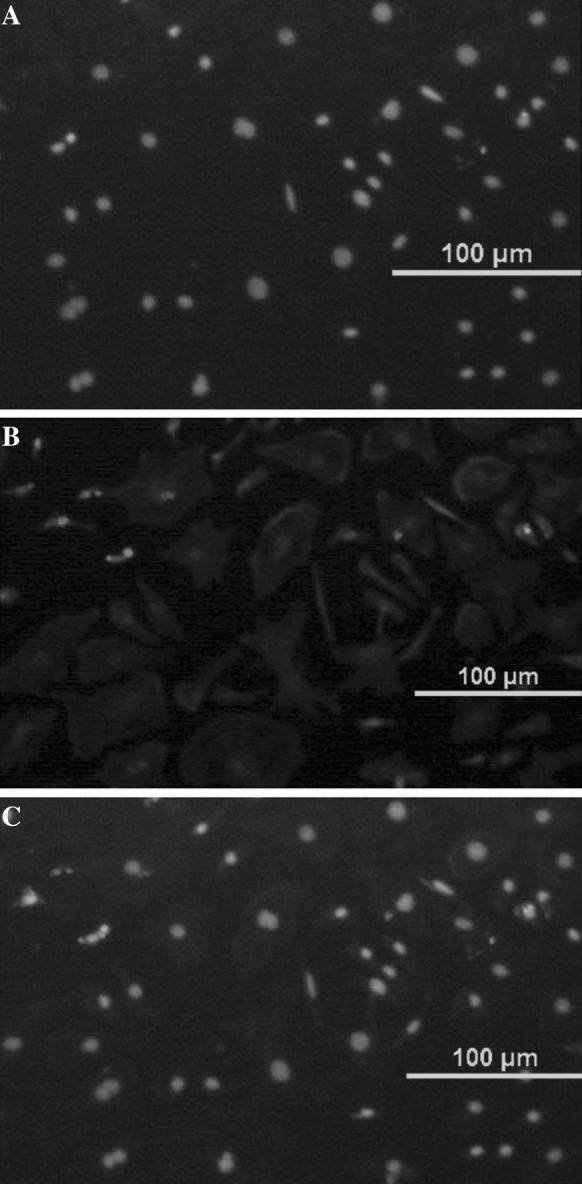

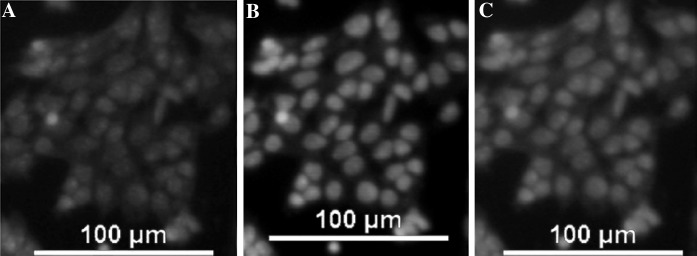

Cell analysis by indirect immunofluorescence

It is commonly considered that As (a single) and Apr (a paired) spermatogonia have stem-cell properties. CD9 and protamine 1 were selected as markers because they are surface makers of spermatogonial stem cells and of post-meiotic cells, respectively. The results of indirect immunofluorescence cell analysis of the Sertoli cells and the SSCs are shown in Fig. 4, and that of the haploid male germ cells and the SSCs are displayed in Fig. 5. It is clear that the SSCs colonies expressed CD9 on their cell surface after culture of 3–5 days (Fig. 4). Although Sertoli cells also expressed CD9, they showed a small spherical nucleus with a thick rim of cytoplasm (Fig. 5). In contrast, SSCs showed a large spherical nucleus with a thin rim of cytoplasm (Fig. 4a, c), whose morphology was comparable to mouse SSCs. Thus, it was demonstrated again that the cell colonies we cultured were SSCs.

Fig. 4.

Identification of SSCs via CD9 expression. a staining with Hoechst 33258 (×200). b Staining for CD9 by indirect immunofluorescence (×200). c Merger of images in a and b

Fig. 5.

Identification of Sertoli cells. a Staining with Hoechst 33258 (×200). b Staining for CD9 by indirect immunofluorescence (×200). c Merger of images in a and b

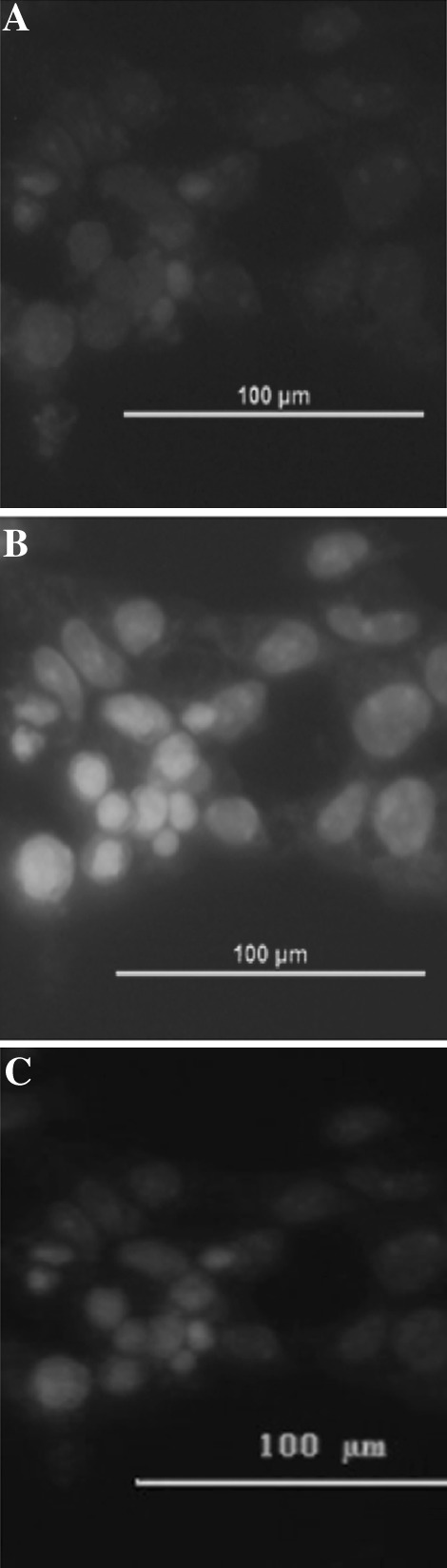

The SSC colonies were treated with RA for 2 days and then cultured in M1-medium for 8 days. After that, the expression of protamine 1 was investigated in comparison to the control (SSCs). Haploid male germ cells largely expressed protamine 1 (Fig. 6). In contrast, SSCs barely expressed protamine 1 (Fig. 7), demonstrating that SSCs had been differentiated into post-meiotic cells.

Fig. 6.

Identification of haploid male germ cells via protamine 1 expression. a Staining for proteamine 1 expression by indirect immunofluorescence (×200). b Staining with Hoechst 33258 (×200). c Merger of images in a and b

Fig. 7.

Identification of SSCs. a Staining for protamine 1 by indirect immunofluorescence (×400). b Staining with Hoechst 33258 (×400). c Merger of images in a and b

Discussion

Investigating the differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells leads to a better understanding of the mechanism of spermatogenesis. AKP assay, RT-PCR analysis and indirect analysis by immunofluorescence cell were performed to identify SSCs. AKP is a pluripotency cell marker (Neri et al. 2007; Park et al. 2008). Stem cells can be stained blue violet or brown by the AKP staining (in Fig. 2), as reported in previous studies (Goel et al. 2007; Guan et al. 2006). In male mice, the Oct4 gene is expressed before spermatogenesis and is confined to type A spermatogonia (Feng et al. 2002). The Ngn3 gene is predominantly expressed in the As, Apr and Aal stages of c-Kit negative spermatogonia in adults and the c-Kit negative fraction of the prepubertal prespermatogonia (Yoshida et al. 2004). The four characteristic genes (Oct4, Integrin alpha 6, Integrin beta 1, Ngn3) of germ cells were selected to identify the spermatogonial stem cells and Sertoli cells (Shinohara et al. 1999). Since the colonies expressed all 4 genes (Fig. 3a) they could be identified as SSC colonies, while the Sertoli cells only expressed the house-keeping gene (β-actin). The cell colonies expressed the CD9 marker on the cell surface after culture 3–5 days (in Fig. 4), thus confirming the identification as spermatogonial stem cells. Although Sertoli cells expressed also CD9, they could be distinguished by morphological differences. They showed a small spherical nucleus with a thick rim of cytoplasm (Fig. 5), SSCs are characterized by a large spherical nucleus with a thin rim of cytoplasm (Fig. 4a, c), a morphology comparable to the morphology of mouse SSCs. Thus, it was demonstrated that the cell colonies we cultured were SSCs.

As a type of nutrient, RA induces genes expression in tissues. Dong et al. (2010) proved that 10−7 mol l−1 of RA were optimal to induce foetal cattle mGCs (male germ cells) into haploid sperm cells. That is why this concentration of RA was applied in this study to treat murine SSCs. Although mGSCs have been differentiated into spermatogenic cells when they were co-cultured in vitro with feeder layer cells, treated with RA or transplantated in vivo (Feng et al. 2002; Kanatsu-Shinohara et al. 2003), few reports have shown that murine SSCs are induced in vitro to form haploid male germ cells using RA. Sycp3 and TH2B, specific markers of haploid male germ cells (Lim et al. 2010; Li et al. 2011), are expressed by haploid male germ cells, as seen in our result. In addition, the result from cell analysis by indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated that haploid male germ cells largely expressed protamine 1 (Fig. 6), which is in contrast to SSCs which only barely expressed this marker (Fig. 7).

We could demonstrate that under the present culture conditions SSCs could generate cell colonies and that RA could induce the differentiation of SSCs to haploid male germ cells thus providing a model to further studies of SSCs differentiation in vitro.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Youth Extra Fund of Northwest A&F University (Z111020905), the Basic Scientific Research Expense of Sci-Tech Innovation Major Project of Northwest A&F University (QN2011061) and the Special Research Subsidy Project of Northwest A&F University (07ZR002).

References

- Abu Elhija M, Lunenfeld E, Schlatt S, Huleihel M. Differentiation of murine male germ cells to spermatozoa in a soft agar culture system. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:285–293. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EL, Baltus AE, Roepers-Gajadien HL, Hassold TJ, de Rooij DG, van Pelt AM, Page DC. Stra8 and its inducer, retinoic acid, regulate meiotic initiation in both spermatogenesis and oogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14976–14980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807297105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte PM, van Bragt MP, de Rooij DG, van Pelt AM. Spermatogonial stem cells: characteristics and experimental possibilities. APMIS. 2005;113:727–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki Y, Sato T, Katagiri K, Kubota Y, Araki Y, Ogawa T. Proliferation of mouse spermatogonial stem cells in microdrop culture. Biol Reprod. 2010;83:951–957. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.082800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J, Knight D, Smith C, Wilhelm D, Richman J, Mamiya S, Yashiro K, Chawengsaksophak K, Wilson MJ, Rossant J, Hamada H, Koopman P. Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science. 2006;312:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1125691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SSW, Wang XY, Wolgemuth DJ (2005) Male sterility in mice lacking retinoic acid receptor alpha involves specific abnormalities in spermiogenesis. Differentiation 73:188–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Clagett-Dame M, DeLuca HF. The role of vitamin A in mammalian reproduction and embryonic development. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:347–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.010402.102745E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Doyle TJ, Liu DL, Kochar J, Kim KH, Rogers MB. Retinoic acid regulation of eye and testis-specific transcripts within a complex locus. Mech Develop. 2007;124:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij DG. Proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells. Reproduction. 2001;121:347–354. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong WZ, Hua JL, Shen WZ, Dou ZY. In vitro production of haploid sperm cells from male germ cells of foetal cattle. Anim Reprod Sci. 2010;118:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng LX, Chen YL, Dettin L, Pera RAR, Herr JC, Goldberg E, Dym M. Generation and in vitro differentiation of a spermatogonial cell line. Science. 2002;297:392–395. doi: 10.1126/science.1073162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel S, Sugimoto M, Minami N, Yamada M, Kume S, Imai H. Identification, isolation, and in vitro culture of porcine gonocytes. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:127–137. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.056879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan K, Nayernia K, Maier LS, Wagner S, Dressel R, Lee JH, Nolte J, Wolf F, Li M, Engel W. Pluripotency of spermatogonial stem cells from adult mouse testis. Nature. 2006;440:1199–1203. doi: 10.1038/nature04697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth CA, Amory JK, Griswold MD. Inhibiting vitamin A metabolism as an approach to male contraception. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Ogura A, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. Restoration of fertility in infertile mice by transplantation of cryopreserved male germline stem cells. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2660–2667. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Miki H, Yoshida S, Toyokuni S, Lee JY, Ogura A, Shinohara T. Leukemia inhibitory factor enhances formation of germ cell colonies in neonatal mouse testis culture. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:55–62. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.055863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P. Nonsteroid nuclear receptors—what are genetic-studies telling us about their role in real-life. Cell. 1995;83:859–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koubova J, Menke DB, Zhou Q, Capel B, Griswold MD, Page DC. Retinoic acid regulates sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2474–2479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510813103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Culture conditions and single growth factors affect fate determination of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:722–731. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.029207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DR, Parks JE, Lim JJ, Yoon H, Ko JJ, Kim KS. Regulation of the proliferation and differentiation of mouse spermatogonial stem cells by LIF/bFGF and FSH during in vitro culture. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:S279. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)01711-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li XC, Bolcun-Filas E, Schimenti JC. Genetic evidence that synaptonemal complex axial elements govern recombination pathway choice in mice. Genetics. 2011;189:71–82. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JJ, Sung SY, Kim HJ, Song SH, Hong JY, Yoon TK, Kim JK, Kim KS, Lee DR. Long-term proliferation and characterization of human spermatogonial stem cells obtained from obstructive and non-obstructive azoospermia under exogenous feeder-free culture conditions. Cell Prolif. 2010;43:405–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh YH, Wu Q, Chew JL, Vega VB, Zhang WW, Chen X, Bourque G, George J, Leong B, Liu J, Wong KY, Sung KW, Lee CWH, Zhao XD, Chiu KP, Lipovich L, Kuznetsov VA, Robson P, Stanton LW, Wei CL, Ruan YJ, Lim B, Ng HH. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2006;38:431–440. doi: 10.1038/ng1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano M, Avarbock MR, Leonida EB, Brinster CJ, Brinster RL. Culture of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Tissue Cell. 1998;30:389–397. doi: 10.1016/S0040-8166(98)80053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri T, Monti M, Rebuzzini P, Merico V, Garagna S, Redi CA, Zuccotti M. Mouse fibroblasts are reprogrammed to Oct-4 and Rex-1 gene expression and alkaline phosphatase activity by embryonic stem cell extracts. Cloning Stem Cells. 2007;9:394–406. doi: 10.1089/clo.2006.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte J, Michelmann HW, Wolf M, Wulf G, Nayernia K, Meinhardt A, Zechner U, Engel W. PSCDGs of mouse multipotent adult germline stem cells can enter and progress through meiosis to form haploid male germ cells in vitro. Differentiation. 2010;80:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oatley JM, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor regulation of genes essential for self-renewal of mouse spermatogonial stem cells is dependent on src family kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25842–25851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703474200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo HG, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SA, McCaffery PJ, Drager UC, De Luca LM. Retinoids in embryonal development. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1021–1054. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. beta(1)- and alpha(6)-integrin are surface markers on mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5504–5509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thellin O, Zorzi W, Lakaye B, De Borman B, Coumans B, Hennen G, Grisar T, Igout A, Heinen E. Housekeeping genes as internal standards: use and limits. J Biotechnol. 1999;75:291–295. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(99)00163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolgemuth DJ, Chung SSW. Role of retinoid signaling in the regulation of spermatogenesis. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;105:189–202. doi: 10.1159/000078189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Takakura A, Ohbo K, Abe K, Wakabayashi J, Yamamoto M, Suda T, Nabeshima Y. Neurogenin3 delineates the earliest stages of spermatogenesis in the mouse testis. Dev Biol. 2004;269:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zile MH. Vitamin A and embryonic development: an overview. J Nutr. 1998;128:455s–458s. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.2.455S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]