Abstract

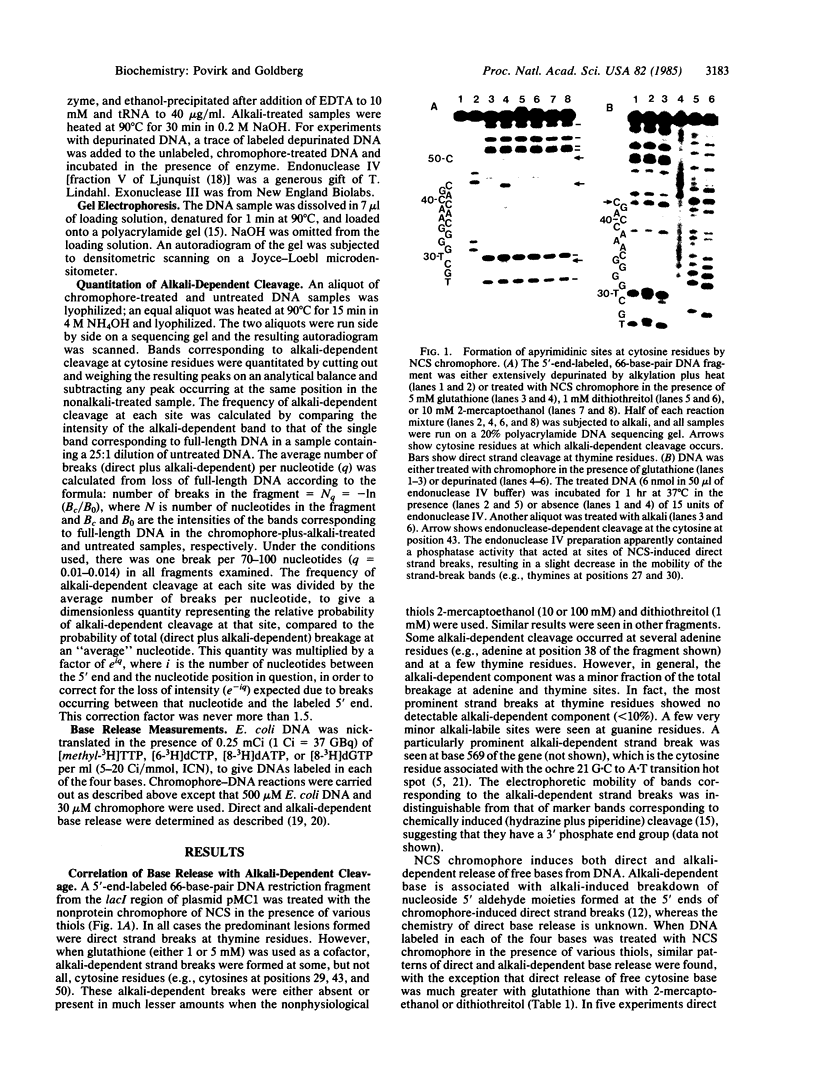

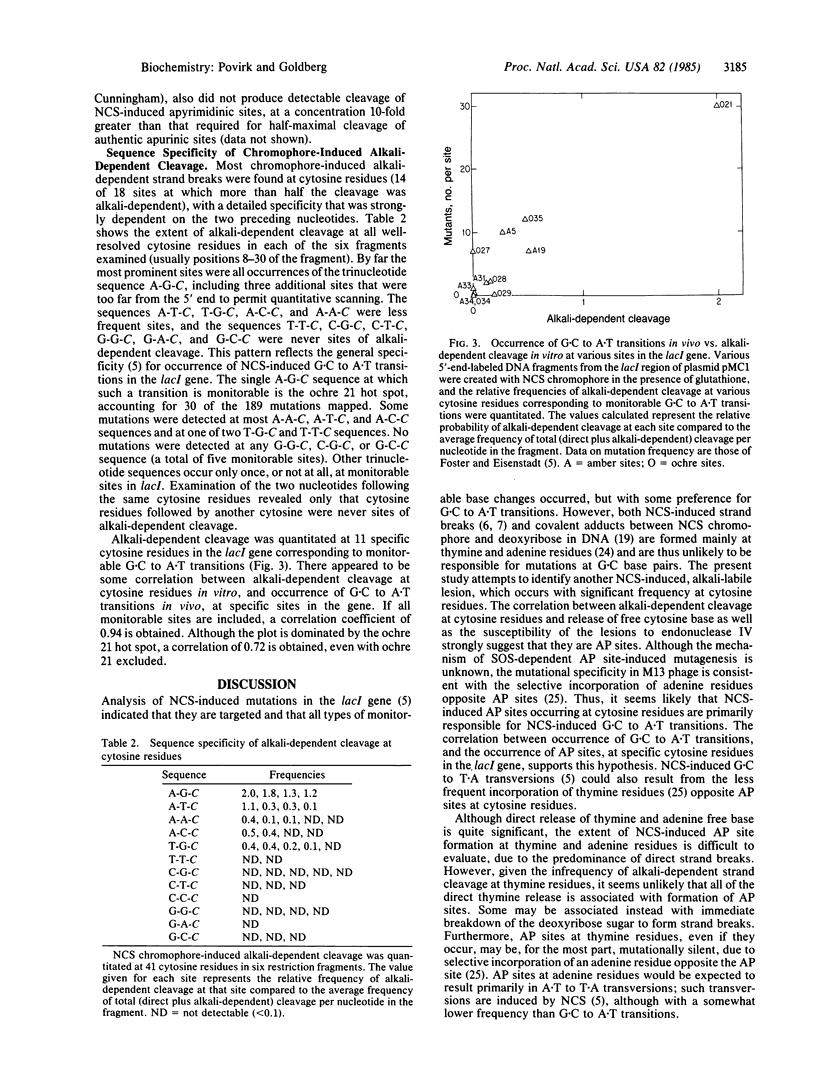

When defined-sequence DNA from the lacl region of plasmid pMC1 was treated with the nonprotein chromophore of neocarzinostatin in the presence of various thiols, the predominant lesions were direct strand breaks, occurring primarily at thymine and adenine residues. In the presence of glutathione, however, alkali-dependent strand breaks, occurring at certain cytosine residues, were also detected but were virtually absent when other thiols were used. Chromophore-induced release of free cytosine base from [3H]cytosine-labeled DNA was 2- to 3-fold greater with glutathione than with the other thiols. These results suggest that the alkali-dependent strand break is some form of apyrimidinic site. These sites were substrates for endonuclease IV of Escherichia coli, although a 5-fold greater concentration of enzyme was required for their cleavage than was required for cleavage of apurinic sites in depurinated DNA. These sites were also less sensitive to E. coli endonuclease VI (exonuclease III) by a factor of at least 5 and less sensitive to E. coli endonuclease III by a factor of at least 10. These and other results suggest that these sites are chemically different from normal apurinic/apyrimidine sites. When chromophore-induced apyrimidinic sites were quantitated as alkali-dependent breaks at 11 specific sites in the lacl gene, a correlation was found between occurrences of these lesions and the reported frequencies of G-C to A X T transitions at the same sites. All occurrences of the trinucleotide sequence A-G-C, including the ochre 21 mutational hot spot, were particularly prominent sites. The selective formation of endonuclease-resistant apyrimidinic sites at specific cytosine residues may explain the high frequency of G X C to A X T transitions in the mutational spectrum of neocarzinostatin.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bose K. K., Tatsumi K., Strauss B. S. Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease sensitive sites as intermediates in the in vitro degradation of deoxyribonucleic acid by neocarzinostatin. Biochemistry. 1980 Oct 14;19(21):4761–4766. doi: 10.1021/bi00562a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calos M. P., Johnsrud L., Miller J. H. DNA sequence at the integration sites of the insertion element IS1. Cell. 1978 Mar;13(3):411–418. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulondre C., Miller J. H. Genetic studies of the lac repressor. III. Additional correlation of mutational sites with specific amino acid residues. J Mol Biol. 1977 Dec 15;117(3):525–567. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulondre C., Miller J. H. Genetic studies of the lac repressor. IV. Mutagenic specificity in the lacI gene of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1977 Dec 15;117(3):577–606. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea A. D., Haseltine W. A. Sequence specific cleavage of DNA by the antitumor antibiotics neocarzinostatin and bleomycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Aug;75(8):3608–3612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt E., Wolf M., Goldberg I. H. Mutagenesis by neocarzinostatin in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: requirement for umuC+ or plasmid pKM101. J Bacteriol. 1980 Nov;144(2):656–660. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.2.656-660.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farabaugh P. J. Sequence of the lacI gene. Nature. 1978 Aug 24;274(5673):765–769. doi: 10.1038/274765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster P. L., Eisenstadt E., Cairns J. Random components in mutagenesis. Nature. 1982 Sep 23;299(5881):365–367. doi: 10.1038/299365a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster P. L., Eisenstadt E. Distribution and specificity of mutations induced by neocarzinostatin in the lacI gene of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983 Jan;153(1):379–383. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.379-383.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatayama T., Goldberg I. H., Takeshita M., Grollman A. P. Nucleotide specificity in DNA scission by neocarzinostatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Aug;75(8):3603–3607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida R., Takahashi T. In vitro release of thymine from DNA by neocarzinostatin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976 Jan 12;68(1):256–261. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isildar M., Schuchmann M. N., Schulte-Frohlinde D., von Sonntag C. gamma-Radiolysis of DNA in oxygenated aqueous solutions: alterations at the sugar moiety. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1981 Oct;40(4):347–354. doi: 10.1080/09553008114551301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappen L. S., Goldberg I. H. Deoxyribonucleic acid damage by neocarzinostatin chromophore: strand breaks generated by selective oxidation of C-5' of deoxyribose. Biochemistry. 1983 Oct 11;22(21):4872–4878. doi: 10.1021/bi00290a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T. A. Mutational specificity of depurination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Mar;81(5):1494–1498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl T. DNA repair enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1982;51:61–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.51.070182.000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungquist S. A new endonuclease from Escherichia coli acting at apurinic sites in DNA. J Biol Chem. 1977 May 10;252(9):2808–2814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd R. S., Haidle C. W., Hewitt R. R. Bleomycin-induced alkaline-labile damage and direct strand breakage of PM2 DNA. Cancer Res. 1978 Oct;38(10):3191–3196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxam A. M., Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. H. Carcinogens induce targeted mutations in Escherichia coli. Cell. 1982 Nov;31(1):5–7. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa O., Moses R. E. Synthesis by DNA polymerase I on bleomycin-treated deoxyribonucleic acid: a requirement for exonuclease III. Biochemistry. 1981 Jan 20;20(2):238–244. doi: 10.1021/bi00505a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon R., Beerman T. A., Goldberg I. H. Characterization of DNA strand breakage in vitro by the antitumor protein neocarzinostatin. Biochemistry. 1977 Feb 8;16(3):486–493. doi: 10.1021/bi00622a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povirk L. F., Dattagupta N., Warf B. C., Goldberg I. H. Neocarzinostatin chromophore binds to deoxyribonucleic acid by intercalation. Biochemistry. 1981 Jul 7;20(14):4007–4014. doi: 10.1021/bi00517a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povirk L. F., Goldberg I. H. Competition between anaerobic covalent linkage of neocarzinostatin chromophore to deoxyribose in DNA and oxygen-dependent strand breakage and base release. Biochemistry. 1984 Dec 18;23(26):6304–6311. doi: 10.1021/bi00321a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povirk L. F., Köhnlein W., Hutchinson F. Specificity of DNA base release by bleomycin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978 Nov 21;521(1):126–133. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(78)90255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S. G., Weiss B. Exonuclease III of Escherichia coli K-12, an AP endonuclease. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):201–211. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaper R. M., Glickman B. W., Loeb L. A. Mutagenesis resulting from depurination is an SOS process. Mutat Res. 1982 Nov;106(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(82)90186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita M., Kappen L. S., Grollman A. P., Eisenberg M., Goldberg I. H. Strand scission of deoxyribonucleic acid by neocarzinostatin, auromomycin, and bleomycin: studies on base release and nucleotide sequence specificity. Biochemistry. 1981 Dec 22;20(26):7599–7606. doi: 10.1021/bi00529a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace S. S. Detection and repair of DNA base damages produced by ionizing radiation. Environ Mutagen. 1983;5(5):769–788. doi: 10.1002/em.2860050514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. C., Kozarich J. W., Stubbe J. The mechanism of free base formation from DNA by bleomycin. A proposal based on site specific tritium release from Poly(dA.dU). J Biol Chem. 1983 Apr 25;258(8):4694–4697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]