Abstract

Alpha-1-adrenergic receptors are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) activated by catecholamines. The alpha-1A and alpha-1B subtypes are expressed in mouse and human myocardium, whereas the alpha-1D protein is found only in coronary arteries. There are far fewer alpha-1-ARs than beta-ARs in the non-failing heart, but their abundance is maintained or increased in the setting of heart failure, which is characterized by pronounced chronic elevation of catecholamines and b□eta-AR dysfunction. Decades of evidence from gain- and loss-of-function studies in isolated cardiac myocytes and numerous animal models demonstrate important adaptive functions for cardiac alpha-1-ARs, to include physiological hypertrophy, positive inotropy, ischemic preconditioning, and protection from cell death. Clinical trial data indicate that blocking alpha-1-ARs is associated with incident heart failure in patients with hypertension. Collectively, these findings suggest that alpha-1-AR activation might mitigate the well-recognized toxic effects of beta-ARs in the hyperadrenergic setting of chronic heart failure. Thus, exogenous cardioselective activation of alpha-1-ARs might represent a novel and viable approach to the treatment of heart failure.

I. Introduction

Marked chronic elevation in the endogenous catecholamines, epinephrine and norepinephrine (NE) is one of the central neurohormonal abnormalities of heart failure. Catecholamines activate two classes of adrenergic receptors (ARs) in the myocardium: beta-ARs (β-ARs) and alpha1-ARs (α1-ARs). β-ARs are the predominant cardiac AR, and the toxic effects of chronic activation of β1-ARs on cardiac myocytes and β2-ARs on cardiac fibroblasts are central to the pathobiology of heart failure.1,2

α1-ARs are coupled to the Gq/11 (Gαq) family of G-proteins and activate phospholipase Cβ1 (PLCβ1), leading to intracellular calcium release though an increase in inositol trisphosphate (IP3). Conventional wisdom views activation of myocardial Gq-coupled receptors as inherently pathological. However, this view is based in large part on a transgenic mouse model with Gq overexpression that markedly exceeds the two-fold increase found in human heart failure,3-5 and thus cannot be considered to simulate human pathophysiology. In human heart failure, the maximal increase in Gq abundance is two-fold,5 and transgenic mice with two-fold cardiomyocyte-specific Gq overexpression have no discernible cardiac phenotype.3,4 α1-ARs also differ from other Gq-coupled receptors with respect to both cellular distribution in the heart, and intracellular localization within myocytes, as described later.

Signaling cascades downstream of α1-ARs are diverse and well-characterized, with over 70 known signaling partners.6 The three subtypes of α1-ARs, α1A, α1B, and α1D, have differential expression in many tissues. The heart contains all three subtypes and substantial evidence demonstrates that myocardial α1-AR activation confers benefits through multiple pathways and processes.6

In the rodent and human heart, α1A and α1B-ARs are expressed predominantly in cardiac myocytes,7,8 whereas the α1D is found in coronary smooth muscle cells.9 Myocardial α1-ARs are essential for normal post-natal growth of the heart, and exert adaptive and protective effects in the setting of chronic stress, such as heart failure. Indeed, α1-AR abundance and function are maintained or increased in the setting of heart failure, in contrast to β-ARs, which are down-regulated and dysfunctional.7,10

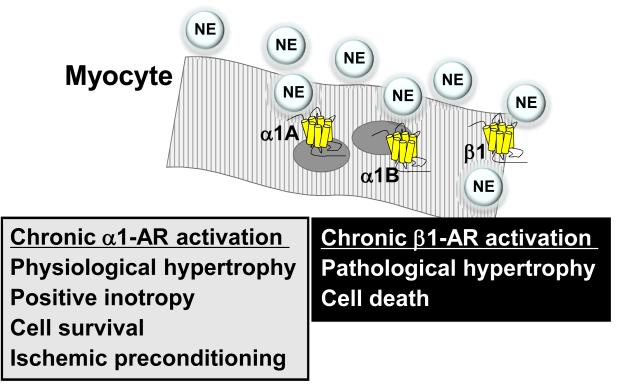

In vitro and animal studies have established that α1-ARs mediate cardioprotection through numerous adaptive processes, including inhibition of cardiac myocyte death, enhanced protein synthesis, increased glucose metabolism, and positive inotropy. Human clinical trials suggest that the use of medications that antagonize the effects of α1-ARs is associated with an increased incidence of heart failure. Here we review briefly the data from cell, animal, and human studies that collectively indicate benefit from activation of α1-ARs in the heart, with a particular focus on the adaptive role of myocardial α1-ARs in the setting of heart failure, as contrasted to the maladaptive effects of β1-ARs (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Adrenergic receptors in the failing cardiac myocyte.

Radioligand binding levels of cardiac myocyte ARs are in the order β1 > β2 > α1B > α1A > β3. Some ventricular myocytes do not express all subtypes.21 New data localize the α1-ARs to the myocyte nucleus.35,36 The (patho)physiological roles of chronic activation are indicated.

II. There are 3 α1-AR subtypes, A, B, and D, with distinct patterns of expression in the heart

IIa. Myocardial α1-ARs: animal models

Cardiac α1-ARs were identified initially in the rat by Williams and Lefkowitz11 and confirmed shortly thereafter in guinea pig by Karliner and colleagues.12 α1-ARs were studied subsequently in the hearts of mice, rabbits, pigs, dogs, and cows. There is species-to-species variation in cardiac α1-AR abundance,13,14 though the basal level of expression is uniformly lower than β-ARs. α1-AR levels are 5- to 8--fold higher in rats than in other species.14

The rodent heart contains mRNAs for all three α1-AR subtypes, though only the α1A and α1B are expressed as proteins (Figure 1).8,14-17 The α1A is the most abundant transcript in the rodent heart, but competition radioligand binding identifies higher levels of α1B.8,18 Importantly, α1-AR proteins can only be detected reliably using radioligand binding, as there are no commercially available antibodies with α1-AR specificity.19

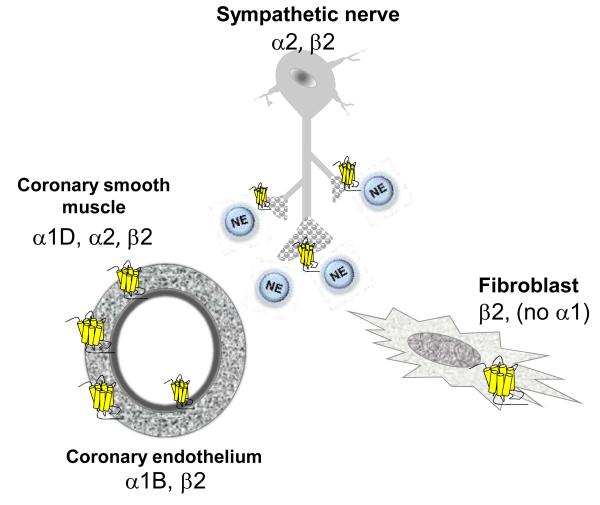

Analysis of the major constituent myocardial cell types in rodents reveals that both neonatal and adult cardiac myocytes contain α1A and α1B-ARs, and cardiac fibroblasts contain no α1-ARs whatsoever (Figure 2).17,20 Interestingly, recent data demonstrate also that the α1A subtype is expressed in only a subpopulation of myocytes.21

Figure 2. Adrenergic receptors in cardiac non-myocytes.

Cardiac ARs are also broadly expressed on cells other than cardiac myocytes. α1D-ARs constrict coronary vascular smooth myocytes. α2-ARs constrict coronary vascular smooth muscle cells and inhibit NE release from sympathetic nerves. β2-ARs stimulate NE release from sympathetic nerves, activate fibroblasts, and relax coronary smooth muscle cells. The roles of ARs in coronary endothelium are less defined.

Thus, signaling events within cardiac myocytes primarily drive the cardiac effects of α1-AR activation, and α1-ARs cannot participate directly in the fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis that characterizes heart failure. Experimental chronic infusion of an α1-AR agonist causes physiological cardiac hypertrophy without fibrosis,22 whereas β2-AR stimulation drives proliferation of both rodent and human cardiac fibroblasts.1,23-26

It is axiomatic that receptor localization must determine function, and α1-, α2, and β-ARs all have distinct distributions among cardiac cells (Figures 1 and 2). These locations need to be kept in mind, when considering the roles of cardiac ARs.

Cellular distribution also distinguishes α1-ARs from the other major myocardial Gq-coupled receptors. The majority of cardiac angiotensin II receptors are found in fibroblasts, with minimal expression in cardiomyocytes,27,28 which may account for pathological effects when angiotensin II Gq-coupled receptors are activated. ET(B) receptors are found on cardiac fibroblasts, with minimal expression on cardiomyocytes,29 and participate in pathological fibrosis in heart failure. The effects of ET(A) stimulation are complex and not uniformly pathological,30 with evidence to support cardioprotective effects such as positive inotropy,31 antiapoptosis,32 and ischemic preconditioning.33 Thus, many of the detrimental effects of Gq-coupled receptor activation can be attributable to effects in cardiac fibroblasts, not cardiomyocytes. As a corollary, cardiac-specific, α-MHC-driven transgenic models of some other Gq-coupled receptors should be viewed with caution, given the extremely low abundance of the wild type receptors in cardiomyocytes relative to non-myocytes; transgenic over-expression in cardiac myocytes might have minimal relevance to actual pathophysiology.

α1-ARs, as most GPCRs, historically were thought to localize to the plasma membrane. However, early studies suggested that α1-ARs were present on the nucleus of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs),34 and recent compelling evidence confirms nuclear localization of a substantial proportion of α1-ARs in adult mouse cardiac myocytes. Radioligand binding of fractionated adult mouse cardiac myocytes detects 80% of α1-ARs in the nuclear fraction, and this finding is substantiated using BODIPY-prazosin, a fluorescently labeled α1-AR antagonist.35 Subsequent studies extended this finding, demonstrating that nuclear localization was required for normal α1-AR signaling and function in adult cardiac myocytes.36 These discoveries, coupled with the identification in adult cardiac myocyte nuclei of angiotensin receptors37 and β1-ARs38, challenge the longstanding paradigm of ‘outside-in’ GPCR signaling in the heart. Endothelin-1 receptors also have been identified at the nucleus,39 although endothelin receptors can function at the plasma membrane.40 Thus nuclear compartmentalization of functional α1-ARs may also distinguish them from other Gq-coupled receptors in the heart.

IIb. Myocardial α1A- and α1B-ARs: human studies

Human and mouse cardiac α1-AR abundance and subtype distribution appear to be very similar. All three α1-AR subtype mRNAs are found in both ventricles of explanted human hearts; the α1A is the most abundant, followed by the α1B and α1D. As in the mouse, only the α1A and α1B proteins are detectable by radioligand binding, and the α1B is more abundant.7 Collectively, these findings suggest that the mouse likely represents an accurate model for human cardiac α1-AR biology.

IIc. Coronary vascular α1D-ARs in rodents and humans

α1-ARs are well known for their effects in vascular tissue, where they typically mediate vasoconstriction. The stimulation of vascular α1-ARs by catecholamines produces little change in the diameter of normal human coronaries.41,42 However, in coronary arteries with disrupted endothelium, α1-AR stimulation produces pronounced vasoconstriction and can lead to myocardial ischemia.43-45 The α1D is the predominant α1-AR subtype in human epicardial coronary arteries and is pharmacologically active in primary human coronary smooth muscle cells and ex vivo coronary rings.9 Functional α1B-ARs are expressed in primary cultures of human epicardial coronary endothelial cells.46 α1A mRNA represents 4% of total α1-AR mRNA in human epicardial coronary arteries and has no discernible function in either smooth muscle or endothelial cells. Of interest, the α1D also is functional in mouse coronary arteries,47,48 further reinforcing the similarities between mouse and human cardiac α1-ARs.

III. The abundance of myocardial α1A- and α1B-ARs is maintained in heart failure

Heart failure is characterized by persistent marked elevations in catecholamines and the response of ARs to chronic stimulation is central to the pathobiology of the failing myocardium. β1-ARs are down-regulated and dysfunctional in heart failure,10,49 and copious evidence demonstrates that excessive stimulation of cardiac β-ARs in the setting of heart failure mediates harmful processes to include cell death, fibrosis, and adverse remodeling. Many large clinical trials indicate that drugs that antagonize β-ARs (i.e. β–blockers) decrease mortality due to heart failure50 and these medications are an essential component of contemporary heart failure therapy.51

In contrast, the abundance and beneficial functions of cardiac α1-ARs are maintained or augmented in the failing heart. Multiple studies indicate that α1-ARs constitute 2-23% (mean = 11%) of all AR binding in non-failing human heart tissue. However, in myocardium from failing human hearts, α1-ARs are 9-38% (mean = 25%) of all ARs.7,52-55

Importantly, α1-ARs also appear to maintain their function in the setting of chronic agonist exposure and heart failure. Chronic treatment of NRVMs with norepinephrine leads to upregulation of α1A-ARs without densensitization of IP3 synthesis or cardiomyocyte growth.56 In non-failing human myocardium, β-AR stimulation induces significantly greater inotropy than α1-AR stimulation; however in failing human heart muscle α1- and β-AR stimulation can produce equal degrees of positive inotropy.57,58

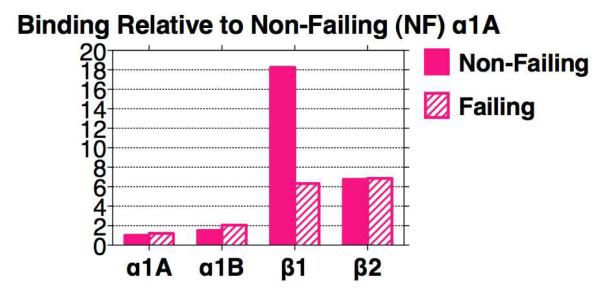

Analysis of α1-AR subtype profiles in failing and non-failing hearts reveals that the abundance of α1A mRNA is increased by 40% in the setting of heart failure,7 and that α1A mRNA abundance positively correlates with left ventricular contractile function.59 α1A and α1B binding levels are both maintained at nearly identical levels in failing human hearts, as are levels of the β2-AR, whereas the β1-AR is markedly down-regulated (Figure 3).7 Consequently, the relative importance of α1-ARs and β2-ARs is magnified in the failing human heart.

Figure 3. Adrenergic receptors in non-failing and failing human myocardium.

The β1-AR is dominant in the non-failing heart, but is markedly down-regulated in the failing heart, whereas the α1A, α1B, and β2 are not. Data are taken from Jensen et al.7 In that study, receptors in human left ventricular free wall were quantified by radioligand binding, using 3H-prazosin for α1-ARs and 125I-cyanopindolol for β-ARs. Specific binding at the 3H-prazosin Kd was 40%. The proportion of the α1A subtype was defined by competition with 5-methyl-urapidil; the proportion of β1, with CGP 20712A; and the proportion of β2, with ICI-118,551. Non-failing hearts were unused donors, and failing were from transplant. Mean data from 4-6 patients for non-failing and failing are normalized to the value of the α1A in non-failing set at 1 (1.44 fmol/mg protein). The preparation used for binding was a complete myocardial lysate, not a “membrane” preparation, so that fmol values relative to protein are low, but no receptors are “tossed out”. The rationale for this approach is that about 60% of total myocardial α1-ARs are in a typical 1000g pellet, and only 15% of total remain in a 40,000g “membrane” pellet used typically for binding.83 Use of “membrane” preparations can cause artifacts, as documented with myocardial β-ARs.181,182

These findings recapitulate earlier and ongoing studies in rodent hearts. Total cardiac α1-AR abundance and function are unaffected by hypertrophy or heart failure in rat models.56,60 α1A mRNA abundance is increased in rats subjected to pressure-loading, as well as in NRVMs exposed to hypertrophic agonists,56 similar to humans with HF.7,59 Recent studies suggest also that α1A expression is maintained or increased in failing mouse hearts (Myagmar et al, unpublished data). Thus it appears that both the non-failing and failing mouse heart accurately model human α1-AR subtype abundance.

The mechanisms underlying the preservation of α1-AR levels and function in heart failure are partly known. β1-AR desensitization occurs through GRK2, the abundance and function of which is upregulated in human and rat heart failure, similar to upregulation of GRK5.61,62 GRK2 and GRK5 have little if any effect on α1-ARs,63-65 and both GRK2 and GRK5 are expressed in many myocardial cell types.62 In contrast, GRK3 is expressed exclusively in myocytes and selectively regulates α1-ARs.62,63 GRK3 abundance is unchanged in heart failure,61,62 which might partly explain the fact that heart failure does not change α1-AR levels and function. Interestingly, transgenic mice with cardiac-specific expression of a GRK3 peptide inhibitor (GRK3ct, analogous to the well-studied GRK2ct) have increased contractility without fibrosis and enhanced α1-AR signaling at baseline. After transverse aortic constriction, GRK3ct transgenic mice are protected from systolic dysfunction, despite equal induction of ventricular hypertrophy and β-myosin heavy chain induction.66,67 These findings imply that increased α1-AR signaling can be beneficial, and collectively mirror the beneficial phenotype of mice with modest α1A-AR overexpression.68

IV. Blocking α1-ARs is associated with heart failure in clinical trials

α1-AR antagonists, or “α-blockers”, are used widely for the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) and occasionally in the treatment of hypertension. ALLHAT, the largest clinical trial of anti-hypertensive medications, included an arm in which roughly 24,000 men and women with high blood pressure received the non-selective α1-blocker, doxazosin. The incidence of heart failure in this group was twice as high as in the other arms of the trial and the Data Safety Monitoring Board discontinued the doxazosin arm prematurely due to safety concerns.69 Of note, in 2002 13.2 million prescriptions for α-blockers were dispensed nationally, and the release of ALLHAT had little near-term effect on the use of these medications.70,71

Smaller studies also corroborate the association between α1-AR blockade and worsening heart failure. In the V-HeFT trial, use of the α1-blocker prazosin was associated with a trend toward increased mortality, in contrast to the beneficial effects of the other vasodilator medications tested.72 A recent analysis also indicated an increased risk for heart failure hospitalizations in patients taking α-blockers without concomitant β-blockade.□73

Further loss-of-function evidence suggesting the benefit of α1-AR activation comes from multiple trials of sympatholysis for the treatment of heart failure. The Moxonidine Safety and Efficacy trial (MOXSE)74 and the Moxonidine Congestive Heart Failure trial (MOXCON)75 studied the efficacy of the sympatholytic agent moxonidine in the treatment of heart failure. Both trials found that moxonidine was very effective in decreasing plasma NE levels, yet both also observed an excess of mortality in the sympatholysis group. The mortality signal was strong enough to prompt premature discontinuation of enrollment in MOXCON.

The BEST trial examined the effects of bucindolol, a β-blocker with sympatholytic properties, on heart failure patients. In contrast to trials using other β-blockers for the treatment of heart failure, the bucindolol group experienced higher mortality.76 It is controversial whether pharmacaogenetic factors play a role in this result with bucindolol.77-82 With reference to the evidence presented in this review, we suggest that one possible explanation for sympatholytic-associated harm in heart failure is the withdrawal of adaptive pathways mediated by α1-AR activation.

The findings from these studies collectively challenge the prevailing paradigm that sympathetic activation is inherently and categorically harmful in heart failure.

V. Knockout (KO) mouse models demonstrate cardioprotective effects of α1A- and α1B-ARs

α1-Antagonists with the aforementioned adverse effects in clinical trials might have had "off-target" effects. However, α1-AR KO mice provide convincing evidence that α1-signaling is required for cardiac protection.

Va. Characterization of α1-AR KO mice

The findings from loss-of-function human trials are corroborated by studies in mice lacking cardiac α1-ARs, with evidence indicating distinct beneficial roles for both the α1A and α1B. Broadly speaking, the α1A appears to regulate α1-mediated cardioprotection, the α1B might mediate catecholamine-induced physiological hypertrophy, and the α1D contributes to regulation of blood pressure, as reviewed in detail.83

Mice lacking the α1A (on a mixed FVB/N-129 background) have low blood pressure and normal heart size.18 α1B-AR knockout mice (α1B-KOs) on a mixed N-129/B6 background have normal heart size,15,84 but a reduced cardiac hypertrophic response to subpressor infusion of an α1-agonist.84 Furthermore, α1B-KOs on a congenic C57BL/6 background have small hearts.85 Regardless of genetic background, α1B-KO mice have normal blood pressure, but a blunted pressor response to infusion of adrenergic agonist.15,84-87 α1D-KO mice have normal hearts, but reduced blood pressure and decreased coronary vasoconstriction in response to phenylephrine.47,87,88

Systemic knockout of both the α1A and α1B (α1AB-KO) eliminates all myocardial α1-AR binding.8 Surprisingly, the α1AB-KO mice (congenic B6 background) are normotensive, indicating that one or more of the other mechanisms controlling blood pressure can compensate for absence of α1-ARs.8 However, cardiac growth cannot be compensated, in that adult α1ABKO male mice have small heart, indicating impaired physiological cardiac hypertrophy after weaning. This “small heart” phenotype is not seen in female mice, which have smaller hearts than do males. Overall contractility measured by echocardiography is normal in the smaller α1AB-KO hearts, but stroke volume, heart rate, and cardiac output are reduced, and the α1AB-KO mice have decreased exercise tolerance.8

Vb. KO models show that myocardial α1-ARs are cardioprotective

α1AB-KO mice also are more susceptible to injury, as evidenced by increased mortality and dilated cardiomyopathy leading to severe heart failure, in the setting of pressure-loading due to transverse aortic constriction.8,89,90 Pressure-loaded α1-ABKO hearts have worse fibrosis than their wild type littermates, and increased cardiac cell death due in part to enhanced apoptosis. Cultured α1-ABKO cardiac myocytes exhibit increased necrosis and apoptosis when treated with NE, isoproterenol, doxorubicin or H2O2.90-92 The enhanced susceptibility to cell death is rescued by adenoviral reintroduction of the α1A, but not the α1B, and requires activation of ERK 1/2.92 Collectively, these in vivo and in vitro findings demonstrate an essential cardioprotective role for the α1A in cardiac myocytes, mediated through ERK signaling.

VI. Gain-of-function experiments demonstrate beneficial effects of cardiac α1-AR activation

Gain-of-function experiments, largely using well-characterized agonists, demonstrate broadly cardioprotective effects of activating myocardial α1-ARs. These adaptive processes include physiological hypertrophy, i.e. hypertrophy with preserved or increased contractile function, positive inotropy, protection from cell death, and ischemic preconditioning. In many cases, it remains unclear which α1-AR subtype regulates these cardioprotective effects, though the α1A has been implicated in a number of studies.

VIa. Pharmacologic α1-AR activation induces physiological cardiac hypertrophy

The experimental use of adrenergic agonists has been central to advancing our understanding of the function of α1-ARs in the heart. NE, epinephrine, and phenylephrine (PE) have been used in cell, animal, and human models for decades. The first report of functional α1-ARs in cardiac myocytes described hypertrophy and an increase in beating frequency of NRVMs upon incubation with NE and the β-blocker, propranolol.93,94 Treatment of NRVMs with α1-AR agonists remains a widely utilized model for experimental cardiac myocyte hypertrophy, and the hypertrophic response has been confirmed in adult cardiac myocytes and myocytes of multiple species.95-100 α1-AR activation induces hypertrophy characterized by upregulation of the “fetal gene” program, to include atrial natriuretic peptide,101,102 α-skeletal actin,103,104 and β-myosin heavy chain.105-107 In vitro agonist experiments have elucidated the complex signaling pathways that mediate α1-induced cellular hypertrophy, identifying over 70 downstream signaling partners to include PKC isoforms,106,108,109 PKD,110,111 ERK 1/2,8, p90RSK,112,113 and HDACs.114,115

Though fetal gene induction generally is considered inherently detrimental, it is unclear whether upregulation of this gene program is causative or merely a marker of pathology. In fact, numerous beneficial roles have been identified for the natriuretic peptides,116 and any pathogenicity of α-skeletal actin and β-myosin heavy chain can be questioned.117-119 Evidence even suggests that β-myosin heavy chain induction is not a marker for myocyte hypertrophy per se.118

In vivo agonist studies substantiate the biologic significance of α1-AR induction of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. Infusion of a sub-pressor dose of NE causes cardiac hypertrophy with preserved or increased contractile function in mouse, cat, and dog models.22,84,120-123 Importantly, the increase in cardiac mass is not accompanied by fibrosis or cell death. Collectively these findings define the in vivo response to α1-AR agonist infusion as physiological, rather than pathological, cardiac hypertrophy.

VIb. Myocardial α1-ARs cause positive inotropy, particularly in the failing heart

Though induction of hypertrophy is the most broadly studied of α1-AR effects, the first physiological response to α1-AR stimulation detected in humans was increased inotropy. In early reports, α1-AR agonists induced an inotropic response ex vivo in preparations from human atria124 and ventricles,125,126 as well as in vivo.127,128 The contractile response to α1-AR activation is preserved or enhanced in failing human myocardium,52,58,129 in contrast to the β-AR response, which is markedly diminished.10

Animal models generally confirm the positive inotropic response to α1-AR stimulation,130-132 and experiments in mice reveal critical details. Ex vivo perfused hearts have a positive inotropic response to α1-AR stimulation,48 and chronic α1-AR activation is required for normal contractile performance in perfused mouse hearts.89 Interestingly, myocytes and ventricular trabeculae from the mouse right ventricle have a negative inotropic response to α1-AR activation, as contrasted with mostly positive responses in left ventricular myocytes and myocardium.133-135 The overall net positive response in the intact heart is likely explained by the greater contribution of the left ventricle. A surprising finding is that heart failure switches the α1-AR inotropic response in mouse right ventricular trabeculae from negative to positive,136 a potential adaptive response to the pulmonary hypertension of heart failure. Given the central role of impaired contractile function in the pathophysiology of heart failure, the augmentation of inotropy through α1-AR activation clearly constitutes an adaptive response.

The inotropic response to α1-AR stimulation likely arises from multiple mechanisms. Myofilament calcium sensitivity is increased,137 as is calcium entry.138-140 α1-AR activation also leads to phosphorylation of myosin light chain and troponin I by myosin light chain kinase and PKC.136,141

Vic.□ α1-AR activation promotes cardiac myocyte survival

The pathobiology of heart failure is characterized by increased cell death through both necrosis and apoptosis, mediated in part by chronic catecholamine surge.142 Abundant evidence identifies β1-ARs as the mediators of enhanced cell death, whereas α1-ARs do not appear to participate in either necrotic or apoptotic cell death. In fact, in vitro studies offer convincing evidence that α1-ARs even counteract toxic β1-AR pathways to preserve cell viability.

In NRVMs, α1-AR agonists block apoptosis due to the β-AR specific agonist isoproterenol,143,144 and in adult rat cardiac myocytes, NE-induced apoptosis is inhibited by a β-blocker (propranolol) but not an α-blocker (prazosin).143 Pharmacologic α1-AR activation also protects against cell death due to numerous other experimental insults to include hypoxia,145 serum starvation,145 and doxorubicin.146

α1-AR anti-apoptotic signaling involves multiple pathways. Studies using NRVMs indicate phosphorylation of Bcl-2145 and Bad after α1-AR activation,147 potentially leading to stabilization of the mitochondrial membrane. ERK 1/2 is a frequent downstream partner of α1-ARs, and also regulates cytoprotective effects in the setting of agonist treatment.92,143,144,148 Phenylephrine (PE)-mediated cytoprotection requires α1-AR regulation of the GATA-4 and NFAT transcription factors.146,149

In vivo models using α1-AR agonists reinforce the in vitro findings. Chronic infusion of α1-AR agonists causes physiological hypertrophy without evidence of cell death in multiple animal models.22,84,120-123 These early studies used agonists that bind all 3 α1-AR subtypes, thus it has been unclear whether the salutary effects resulted from activation of the α1A, the α1B, or some combination thereof. However, recent evidence points toward the α1A as the primary cardioprotective AR subtype. Continuous infusion of a subpressor dose of the α1A-selective agonist A61603 prevents death and heart failure in mice injected with the chemotherapeutic agent, doxorubicin.150,151 These results echo the findings from experiments using cardiac myocytes from α1-ABKO mice in which adenoviral reconstitution of the α1A, but not the α1B, abrogates enhanced myocyte death due to doxorubicin, β-AR stimulation, and H2O2.92

VId. α1-ARs mediate ischemic preconditioning in the heart

Abundant evidence also supports a role for α1-ARs in ischemic preconditioning. Agonist studies in multiple species including rat,152,153 mouse,154 dog,155-157 pig,158 and rabbit159 indicate that myocardial α1-AR activation protects against ischemic injury. In particular, the α1A is implicated in the preconditioning response in a number of different models. Transgenic mice overexpressing a constitutively active α1A show complete protection from ischemic injury, whereas α1B transgenics develop injury comparable to wild type mice.160 A novel transgenic rat model also indicates that overexpression of the α1A in the rat heart reduces infarct size after coronary ligation by mediating the second window of ischemic preconditioning.161

Activation of PKC is central to α1-AR mediated preconditioning,153,162-164 and further downstream effectors include superoxide dismutase,165,166 inducible nitric oxide synthase,154 5’ nucleotidase,155 and heat shock proteins.162

VIe. α1-AR transgenic mouse models have variable phenotypes

Studies of mice with transgenic overexpression of α1-AR subtypes yield somewhat conflicted results, possibly resulting from disparate constructs (different promoters, different receptor cDNAs), the varying extents to which the receptors are overexpressed, whether the transgenic mouse is systemic or cardiac-specific, the specific receptor active state conferred by the mutations in constitutively active mutants, and varied sites of transgene integration into the genome. Sex and strain of the transgenic mice studied likely contribute as well, but are not uniformly given in the various papers. Many of the details on each transgenic mouse are tabulated elsewhere.6

The disparate findings may also result in part from challenges inherent in the overexpression of GPCRs. In particular, transgenesis does not guarantee that the overexpressed receptor will assume the same conformation as an endogenous receptor in the setting of agonist stimulation. As such, it is conceivable that physiological responses in transgenic GPCR models are governed by aberrant signaling downstream from an overexpressed receptor in an alternate active state, rather than merely an exaggerated representation of endogenous signaling. This concept was demonstrated nicely in mouse cardiomyocytes overexpressing a constitutively active human β2-AR.167 With reference to α1-AR transgenics, this issue is complicated further by the fact that different α1 agonists themselves induce biased signaling at wild type receptors, presumably based on receptor conformation.168

Two-fold systemic overexpression of a constitutively active mutant α1A enhances ischemic preconditioning.160 In a separate transgenic model, exaggerated cardiac myocyte-specific overexpression of the wild type α1A improves contractility without hypertrophy (148-170 fold overexpression).169 Sixty-six-fold overexpression of the wild type α1A protects against heart failure due to pressure loading and myocardial infarction, but is associated with enhanced fibrosis, apoptosis and death in aged mice.68,170,171 The latter results are particularly surprising in light of the wealth of evidence from other gain-of-function studies indicating cardioprotection and a lack of fibrosis, and could be confounded by the grossly supraphysiological levels of α1A overexpression.

Characterization of multiple α1B transgenic mice has been even more confusing. Two-fold systemic overexpression of a constitutively active mutant α1B causes cardiac hypertrophy in the setting of normal blood pressure,172 as does cardiac myocyte-specific 3-fold overexpression of a constitutive active mutant α1B,173 or 70-fold overexpression of a wild type α1B.174 However, another mouse line with 2-fold overexpression of a constitutively active α1B has normal heart size with decreased contractile function,175 and 43-fold myocyte-specific overexpression of the α1B produces dilated cardiomyopathy and early death.176-178

The only clear commonality between the various α1B transgenics is the lack of a blood pressure phenotype. These apparently incompatible findings likely arise from the sources of variability mentioned above, and ultimately offer limited insight regarding the physiological role of the myocardial α1B-AR. As there is no available pharmacological compound with α1B selectivity, the best available evidence regarding the function of the α1B in the heart comes from knockout mouse models that suggest it is involved in normal post-weaning physiological developmental hypertrophy,8,84,85 and hypertrophy induced by sub-pressor infusion of an α1-agonist.84

VII. Summary

Decades of studies in cells, animals, and humans describe adaptive and protective roles for α1-ARs in the heart. These functions are particularly important in the context of chronic adrenergic activation, such as heart failure, wherein β-ARs are downregulated and dysfunctional. Evidence from loss- and gain-of-function studies indicates that myocardial α1-ARs not only protect against the development of heart failure, but also maintain their beneficial functions in established heart failure. As detailed in this review, these functions include physiological hypertrophy, enhanced positive inotropy, protection against apoptotic and necrotic cell death, and ischemic preconditioning. α1-ARs are estimated to be 90% unoccupied in chronic heart failure, suggesting that these beneficial pathways could be augmented further by activation with an exogenous agonist.179 Indeed, this concept was affirmed in a recent small clinical trial in which advanced heart failure patients derived significant clinical benefit from the use of midodrine, a non-selective α1-AR agonist.180

In mice and humans, the α1A and α1B are the predominant α1-AR subtypes in the myocardium, whereas the α1D is expressed in coronary arteries. The α1A likely regulates cell survival pathways and ischemic preconditioning, and contributes to contractile function. The function of the α1B is less certain, though it appears to regulate post-natal heart size. Activation of the α1D leads to coronary vasoconstriction, particularly in the absence of a functioning endothelium. Ongoing translational work will expand upon the recent finding that selective α1A activation protects against heart failure in a mouse model,150,151 and test the hypothesis that cardioselective α1-AR activation is a viable therapy for heart failure.

Acknowledgments

Support:

BCJ

NIH K08HL096836

TDO

NIH P20 RR-017662, AHA Greater Midwest Affiliate

PCS

NIH HL31113, VA IO1BX001970, AHA Western States Affiliate

References

- 1.Porter KE, Turner NA. Cardiac fibroblasts: at the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123(2):255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(19):1747–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakata Y, Hoit BD, Liggett SB, Walsh RA, Dorn GW., 2nd Decompensation of pressure-overload hypertrophy in G alpha q-overexpressing mice. Circulation. 1998;97(15):1488–1495. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.15.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams JW, Sakata Y, Davis MG, et al. Enhanced Galphaq signaling: a common pathway mediates cardiac hypertrophy and apoptotic heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(17):10140–10145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponicke K, Vogelsang M, Heinroth M, et al. Endothelin receptors in the failing and nonfailing human heart. Circulation. 1998;97(8):744–751. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.8.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen BC, O'Connell TD, Simpson PC. Alpha-1-adrenergic receptors: targets for agonist drugs to treat heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51(4):518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen BC, Swigart PM, De Marco T, Hoopes C, Simpson PC. {alpha}1-Adrenergic receptor subtypes in nonfailing and failing human myocardium. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(6):654–663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.846212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Connell TD, Ishizaka S, Nakamura A, et al. The alpha1A/C- and alpha1B-adrenergic receptors are required for physiological cardiac hypertrophy in the double-knockout mouse. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(11):1783–1791. doi: 10.1172/JCI16100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen BC, Swigart PM, Laden ME, DeMarco T, Hoopes C, Simpson PC. The alpha-1D Is the predominant alpha-1-adrenergic receptor subtype in human epicardial coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(13):1137–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bristow MR, Ginsburg R, Minobe W, et al. Decreased catecholamine sensitivity and beta-adrenergic-receptor density in failing human hearts. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(4):205–211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RS, Lefkowitz RJ. Alpha-adrenergic receptors in rat myocardium. Identification by binding of [3H]dihydroergocryptine. Circ Res. 1978;43(5):721–727. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.5.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karliner JS, Barnes P, Hamilton CA, Dollery CT. alpha 1-Adrenergic receptors in guinea pig myocardium: identification by binding of a new radioligand, (3H)-prazosin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;90(1):142–149. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)91601-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukherjee A, Haghani Z, Brady J, et al. Differences in myocardial alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor numbers in different species. Am J Physiol. 1983;245(6):H957–961. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.6.H957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinfath M, Chen YY, Lavicky J, et al. Cardiac alpha 1-adrenoceptor densities in different mammalian species. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;107(1):185–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavalli A, Lattion AL, Hummler E, et al. Decreased blood pressure response in mice deficient of the alpha1b-adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(21):11589–11594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rokosh DG, Bailey BA, Stewart AF, Karns LR, Long CS, Simpson PC. Distribution of alpha 1C-adrenergic receptor mRNA in adult rat tissues by RNase protection assay and comparison with alpha 1B and alpha 1D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200(3):1177–1184. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart AF, Rokosh DG, Bailey BA, et al. Cloning of the rat alpha 1C-adrenergic receptor from cardiac myocytes. alpha 1C, alpha 1B, and alpha 1D mRNAs are present in cardiac myocytes but not in cardiac fibroblasts. Circ Res. 1994;75(4):796–802. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.4.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rokosh DG, Simpson PC. Knockout of the alpha 1A/C-adrenergic receptor subtype: the alpha 1A/C is expressed in resistance arteries and is required to maintain arterial blood pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(14):9474–9479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132552699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen BC, Swigart PM, Simpson PC. Ten commercial antibodies for alpha-1-adrenergic receptor subtypes are nonspecific. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379(4):409–412. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Connell TD, Rokosh DG, Simpson PC. Cloning and characterization of the mouse α1C/A-adrenergic receptor gene and analysis of an α1C promoter in cardiac myocytes: role of an MCAT element that binds transcriptional enhancer factor-1 (TEF-1) Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59(5):1225–1234. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myagmar B-E, Rodrigo MC, Swigart PM, Simpson PC. The alpha-1A adrenergic receptor subtype Is expressed in only a sub-population of ventricular myocytes (Abstract) Circulation. 2007;116(II):184. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marino TA, Cassidy M, Marino DR, Carson NL, Houser S. Norepinephrine-induced cardiac hypertrophy of the cat heart. Anat Rec. 1991;229(4):505–510. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092290411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long CS, Hartogensis WE, Simpson PC. Beta-adrenergic stimulation of cardiac non-myocytes augments the growth-promoting activity of non-myocyte conditioned medium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1993;25(8):915–925. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long CS, Henrich CJ, Simpson PC. A growth factor for cardiac myocytes is produced by cardiac nonmyocytes. Cell Regul. 1991;2(12):1081–1095. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.12.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner NA, Porter KE, Smith WH, White HL, Ball SG, Balmforth AJ. Chronic beta2-adrenergic receptor stimulation increases proliferation of human cardiac fibroblasts via an autocrine mechanism. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57(3):784–792. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00729-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vlahos CJ. Signaling pathways mediated by the beta(2)-adrenergic receptor in the fibroblast: a novel role for PI 3-kinase. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33(6):1049–1051. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray MO, Long CS, Kalinyak JE, Li HT, Karliner JS. Angiotensin II stimulates cardiac myocyte hypertrophy via paracrine release of TGF-beta 1 and endothelin-1 from fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;40(2):352–363. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim NN, Villarreal FJ, Printz MP, Lee AA, Dillmann WH. Trophic effects of angiotensin II on neonatal rat cardiac myocytes are mediated by cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(3 Pt 1):E426–437. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.269.3.E426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modesti PA, Vanni S, Paniccia R, et al. Characterization of endothelin-1 receptor subtypes in isolated human cardiomyocytes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34(3):333–339. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199909000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vignon-Zellweger N, Heiden S, Miyauchi T, Emoto N. Endothelin and endothelin receptors in the renal and cardiovascular systems. Life sciences. 2012;91(13-14):490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacCarthy PA, Grocott-Mason R, Prendergast BD, Shah AM. Contrasting inotropic effects of endogenous endothelin in the normal and failing human heart: studies with an intracoronary ET(A) receptor antagonist. Circulation. 2000;101(2):142–147. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao XS, Pan W, Bekeredjian R, Shohet RV. Endogenous endothelin-1 is required for cardiomyocyte survival in vivo. Circulation. 2006;114(8):830–837. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.577288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gourine AV, Molosh AI, Poputnikov D, Bulhak A, Sjoquist PO, Pernow J. Endothelin-1 exerts a preconditioning-like cardioprotective effect against ischaemia/reperfusion injury via the ET(A) receptor and the mitochondrial K(ATP) channel in the rat in vivo. British journal of pharmacology. 2005;144(3):331–337. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buu NT, Hui R, Falardeau P. Norepinephrine in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes: association with the cell nucleus and binding to nuclear alpha 1- and beta-adrenergic receptors. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1993;25(9):1037–1046. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright CD, Chen Q, Baye NL, et al. Nuclear alpha1-adrenergic receptors signal activated ERK localization to caveolae in adult cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2008;103(9):992–1000. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright CD, Wu SC, Dahl EF, Sazama AJ, O'Connell TD. Nuclear localization drives alpha1-adrenergic receptor oligomerization and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Cell Signal. 2012;24(3):794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tadevosyan A, Maguy A, Villeneuve LR, et al. Nuclear-delimited angiotensin receptor-mediated signaling regulates cardiomyocyte gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(29):22338–22349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaniotis G, Del Duca D, Trieu P, Rohlicek CV, Hebert TE, Allen BG. Nuclear beta-adrenergic receptors modulate gene expression in adult rat heart. Cell Signal. 2011;23(1):89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boivin B, Chevalier D, Villeneuve LR, Rousseau E, Allen BG. Functional endothelin receptors are present on nuclei in cardiac ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(31):29153–29163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bossuyt J, Chang CW, Helmstadter K, et al. Spatiotemporally distinct protein kinase D activation in adult cardiomyocytes in response to phenylephrine and endothelin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(38):33390–33400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.246447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodgson JM, Cohen MD, Szentpetery S, Thames MD. Effects of regional alpha- and beta-blockade on resting and hyperemic coronary blood flow in conscious, unstressed humans. Circulation. 1989;79(4):797–809. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lorenzoni R, Rosen SD, Camici PG. Effect of alpha 1-adrenoceptor blockade on resting and hyperemic myocardial blood flow in normal humans. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(4 Pt 2):H1302–1306. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.4.H1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baumgart D, Haude M, Gorge G, et al. Augmented alpha-adrenergic constriction of atherosclerotic human coronary arteries. Circulation. 1999;99(16):2090–2097. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kern MJ, Horowitz JD, Ganz P, et al. Attenuation of coronary vascular resistance by selective alpha 1-adrenergic blockade in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5(4):840–846. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vita JA, Treasure CB, Yeung AC, et al. Patients with evidence of coronary endothelial dysfunction as assessed by acetylcholine infusion demonstrate marked increase in sensitivity to constrictor effects of catecholamines. Circulation. 1992;85(4):1390–1397. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen BC, Swigart PM, Montgomery MD, Simpson PC. Functional alpha-1B adrenergic receptors on human epicardial coronary artery endothelial cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;382:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s00210-010-0558-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chalothorn D, McCune DF, Edelmann SE, et al. Differential cardiovascular regulatory activities of the alpha 1B- and alpha 1D-adrenoceptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305(3):1045–1053. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.048553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turnbull L, McCloskey DT, O'Connell TD, Simpson PC, Baker AJ. Alpha 1-adrenergic receptor responses in alpha 1AB-AR knockout mouse hearts suggest the presence of alpha 1D-AR. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284(4):H1104–1109. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00441.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bristow MR, Minobe WA, Raynolds MV, et al. Reduced beta 1 receptor messenger RNA abundance in the failing human heart. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(6):2737–2745. doi: 10.1172/JCI116891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teerlink JR, Massie BM. Beta-adrenergic blocker mortality trials in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(9A):94R–102R. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00709-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonow RO, Ganiats TG, Beam CT, et al. ACCF/AHA/AMA-PCPI 2011 performance measures for adults with heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the American Medical Association-Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. Circulation. 2012;125(19):2382–2401. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182507bec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bohm M, Diet F, Feiler G, Kemkes B, Erdmann E. Alpha-adrenoceptors and alpha-adrenoceptor-mediated positive inotropic effects in failing human myocardium. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1988;12(3):357–364. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198809000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bristow MR, Minobe W, Rasmussen R, Hershberger RE, Hoffman BB. Alpha-1 adrenergic receptors in the nonfailing and failing human heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;247(3):1039–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steinfath M, Danielsen W, von der Leyen H, et al. Reduced alpha 1- and beta 2-adrenoceptor-mediated positive inotropic effects in human end-stage heart failure. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105(2):463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vago T, Bevilacqua M, Norbiato G, et al. Identification of alpha 1-adrenergic receptors on sarcolemma from normal subjects and patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: characteristics and linkage to GTP-binding protein. Circ Res. 1989;64(3):474–481. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rokosh DG, Stewart AF, Chang KC, et al. Alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtype mRNAs are differentially regulated by alpha1-adrenergic and other hypertrophic stimuli in cardiac myocytes in culture and in vivo. Repression of alpha1B and alpha1D but induction of alpha1C. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(10):5839–5843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scholz H, Eschenhagen T, Neumann J, Stein B. Receptor-mediated regulation of cardiac contractility: inotropic effects of alpha-adrenoceptor stimulation with phenylephrine and noradrenaline in failing human hearts. In: Endoh M, Morad M, Scholz H, Iijima T, editors. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiovascular regulation. Springer-Verlag; Tokyo: 1996. pp. 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skomedal T, Borthne K, Aass H, Geiran O, Osnes JB. Comparison between alpha-1 adrenoceptor-mediated and beta adrenoceptor- mediated inotropic components elicited by norepinephrine in failing human ventricular muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280(2):721–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monto F, Oliver E, Vicente D, et al. Different expression of adrenoceptors and GRKs in the human myocardium depends on heart failure etiology and correlates to clinical variables. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303(3):H3681–376. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01061.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sjaastad I, Schiander I, Sjetnan A, et al. Increased contribution of alpha 1- vs. beta-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic response in rats with congestive heart failure. Acta physiologica Scandinavica. 2003;177(4):449–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aguero J, Almenar L, Monto F, et al. Myocardial G protein receptor-coupled kinase expression correlates with functional parameters and clinical severity in advanced heart failure. Journal of cardiac failure. 2012;18(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vinge LE, Oie E, Andersson Y, Grogaard HK, Andersen G, Attramadal H. Myocardial distribution and regulation of GRK and beta-arrestin isoforms in congestive heart failure in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281(6):H2490–2499. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vinge LE, Andressen KW, Attramadal T, et al. Substrate specificities of g protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 and -3 at cardiac myocyte receptors provide basis for distinct roles in regulation of myocardial function. Molecular pharmacology. 2007;72(3):582–591. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rockman HA, Choi DJ, Rahman NU, Akhter SA, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ. Receptor-specific in vivo desensitization by the G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(18):9954–9959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eckhart AD, Duncan SJ, Penn RB, Benovic JL, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ. Hybrid transgenic mice reveal in vivo specificity of G protein-coupled receptor kinases in the heart. Circ Res. 2000;86(1):43–50. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vinge LE, von Lueder TG, Aasum E, et al. Cardiac-restricted expression of the carboxyl-terminal fragment of GRK3 Uncovers Distinct Functions of GRK3 in regulation of cardiac contractility and growth: GRK3 controls cardiac alpha1-adrenergic receptor responsiveness. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(16):10601–10610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.von Lueder TG, Gravning J, How OJ, et al. Cardiomyocyte-restricted inhibition of G protein-coupled receptor kinase-3 attenuates cardiac dysfunction after chronic pressure overload. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303(1):H66–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00724.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Du XJ, Fang L, Gao XM, et al. Genetic enhancement of ventricular contractility protects against pressure-overload-induced cardiac dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:979–987. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.ALLHAT CRG. Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(15):1967–1975. [see comments] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stafford RS, Furberg CD, Finkelstein SN, Cockburn IM, Alehegn T, Ma J. Impact of clinical trial results on national trends in alpha-blocker prescribing, 1996-2002. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(1):54–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Player MS, Gill JM, Fagan HB, Mainous AG., 3rd Antihypertensive prescribing practices: impact of the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial. Journal of clinical hypertension. 2006;8(12):860–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2006.05781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cohn JN. The Vasodilator-Heart Failure Trials (V-HeFT) Mechanistic data from the VA Cooperative Studies. Introduction. Circulation. 1993;87(6 Suppl):VI1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dhaliwal AS, Habib G, Deswal A, et al. Impact of alpha 1-adrenergic antagonist use for benign prostatic hypertrophy on outcomes in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(2):270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Swedberg K, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al. Effects of sustained-release moxonidine, an imidazoline agonist, on plasma norepinephrine in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2002;105(15):1797–1803. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014212.04920.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohn JN, Pfeffer MA, Rouleau JL, et al. Adverse mortality effect of central sympathetic inhibition with sustained-release moxonidine in patients with heart failure (MOXCON) Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5(5):659–667. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bristow MR, Krause-Steinrauf H, Nuzzo R, et al. Effect of baseline or changes in adrenergic activity on clinical outcomes in the beta-blocker evaluation of survival trial. Circulation. 2004;110(11):1437–1442. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000141297.50027.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liggett SB, Mialet-Perez J, Thaneemit-Chen S, et al. A polymorphism within a conserved beta(1)-adrenergic receptor motif alters cardiac function and beta-blocker response in human heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(30):11288–11293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509937103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bristow MR, Murphy GA, Krause-Steinrauf H, et al. An alpha2C-adrenergic receptor polymorphism alters the norepinephrine-lowering effects and therapeutic response of the beta-blocker bucindolol in chronic heart failure. Circulation. Heart failure. 2010;3(1):21–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.885962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.O'Connor CM, Fiuzat M, Carson PE, et al. Combinatorial pharmacogenetic interactions of bucindolol and beta1, alpha2C adrenergic receptor polymorphisms. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e44324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cresci S, Kelly RJ, Cappola TP, et al. Clinical and genetic modifiers of long-term survival in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(5):432–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.White HL, de Boer RA, Maqbool A, et al. An evaluation of the beta-1 adrenergic receptor Arg389Gly polymorphism in individuals with heart failure: a MERIT-HF sub-study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5(4):463–468. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sehnert AJ, Daniels SE, Elashoff M, et al. Lack of association between adrenergic receptor genotypes and survival in heart failure patients treated with carvedilol or metoprolol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(8):644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Simpson P. Lessons from knockouts: the alpha1-ARs. In: Perez DM, editor. The Adrenergic Receptors in the 21st Century. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 2006. pp. 207–240. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vecchione C, Fratta L, Rizzoni D, et al. Cardiovascular influences of alpha1b-adrenergic receptor defect in mice. Circulation. 2002;105(14):1700–1707. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012750.08480.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rodrigo MC, Joho S, Swigart PM, et al. The alpha-1-B adrenergic receptor subtype is required for physiological cardiac hypertrophy in normal development (abstract) Circulation. 2005;112(II):123. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Daly CJ, Deighan C, McGee A, et al. A knockout approach indicates a minor vasoconstrictor role for vascular alpha1B-adrenoceptors in mouse. Physiol Genomics. 2002;9(2):85–91. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00065.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hosoda C, Koshimizu TA, Tanoue A, et al. Two alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtypes regulating the vasopressor response have differential roles in blood pressure regulation. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67(3):912–922. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.007500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tanoue A, Nasa Y, Koshimizu T, et al. The alpha1D-adrenergic receptor directly regulates arterial blood pressure via vasoconstriction. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(6):765–775. doi: 10.1172/JCI14001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McCloskey DT, Turnbull L, Swigart P, O'Connell TD, Simpson PC, Baker AJ. Abnormal myocardial contraction in alpha(1A)- and alpha(1B)-adrenoceptor double-knockout mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35(10):1207–1216. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.O'Connell TD, Swigart PM, Rodrigo MC, et al. Alpha1-adrenergic receptors prevent a maladaptive cardiac response to pressure overload. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(4):1005–1015. doi: 10.1172/JCI22811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huang Y, Wright CD, Kobayashi S, et al. GATA4 is a survival factor in adult cardiac myocytes but is not required for alpha1A-adrenergic receptor survival signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(2):H699–707. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01204.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huang Y, Wright CD, Merkwan CL, et al. An alpha1A-adrenergic-extracellular signal-regulated kinase survival signaling pathway in cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2007;115(6):763–772. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Simpson P. Norepinephrine-stimulated hypertrophy of cultured rat myocardial cells is an alpha 1 adrenergic response. J Clin Invest. 1983;72(2):732–738. doi: 10.1172/JCI111023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Simpson P. Stimulation of hypertrophy of cultured neonatal rat heart cells through an alpha 1-adrenergic receptor and induction of beating through an alpha 1- and beta 1-adrenergic receptor interaction. Evidence for independent regulation of growth and beating. Circ Res. 1985;56(6):884–894. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Clark WA, Rudnick SJ, Andersen LC, LaPres JJ. Myosin heavy chain synthesis is independently regulated in hypertrophy and atrophy of isolated adult cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(41):25562–25569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clark WA, Rudnick SJ, LaPres JJ, Andersen LC, LaPointe MC. Regulation of hypertrophy and atrophy in cultured adult heart cells. Circ Res. 1993;73(6):1163–1176. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fuller SJ, Gaitanaki CJ, Sugden PH. Effects of catecholamines on protein synthesis in cardiac myocytes and perfused hearts isolated from adult rats. Stimulation of translation is mediated through the alpha 1-adrenoceptor. Biochem J. 1990;266(3):727–736. doi: 10.1042/bj2660727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ikeda U, Tsuruya Y, Yaginuma T. Alpha 1-adrenergic stimulation is coupled to cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. Am J Physiol. 1991;260(3 Pt 2):H953–956. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.3.H953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Simpson PC. Comments on "Load regulation of the properties of adult feline cardiocytes: The role of substrate adhesion" which appeared in Circ Res 58:692-705, 1986 (letter) Circ. Res. 1988;62:864–866. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.4.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Volz A, Piper HM, Siegmund B, Schwartz P. Longevity of adult ventricular rat heart muscle cells in serum-free primary culture. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991;23(2):161–173. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90103-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Knowlton KU, Baracchini E, Ross RS, et al. Co-regulation of the atrial natriuretic factor and cardiac myosin light chain-2 genes during alpha-adrenergic stimulation of neonatal rat ventricular cells. Identification of cis sequences within an embryonic and a constitutive contractile protein gene which mediate inducible expression. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(12):7759–7768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee HR, Henderson SA, Reynolds R, Dunnmon P, Yuan D, Chien KR. Alpha 1-adrenergic stimulation of cardiac gene transcription in neonatal rat myocardial cells. Effects on myosin light chain-2 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(15):7352–7358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bishopric NH, Simpson PC, Ordahl CP. Induction of the skeletal alpha-actin gene in alpha 1-adrenoceptor-mediated hypertrophy of rat cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1987;80(4):1194–1199. doi: 10.1172/JCI113179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Long CS, Ordahl CP, Simpson PC. Alpha 1-adrenergic receptor stimulation of sarcomeric actin isogene transcription in hypertrophy of cultured rat heart muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1989;83(3):1078–1082. doi: 10.1172/JCI113951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kariya K, Farrance IK, Simpson PC. Transcriptional enhancer factor-1 in cardiac myocytes interacts with an alpha 1-adrenergic- and beta-protein kinase C-inducible element in the rat beta-myosin heavy chain promoter. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(35):26658–26662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kariya K, Karns LR, Simpson PC. An enhancer core element mediates stimulation of the rat beta-myosin heavy chain promoter by an alpha 1-adrenergic agonist and activated beta-protein kinase C in hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(5):3775–3782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Waspe LE, Ordahl CP, Simpson PC. The cardiac beta-myosin heavy chain isogene is induced selectively in alpha 1-adrenergic receptor-stimulated hypertrophy of cultured rat heart myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1990;85(4):1206–1214. doi: 10.1172/JCI114554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Braz JC, Gregory K, Pathak A, et al. PKC-alpha regulates cardiac contractility and propensity toward heart failure. Nature Med. 2004;10(3):248–254. doi: 10.1038/nm1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rohde S, Sabri A, Kamasamudran R, Steinberg SF. The alpha(1)-adrenoceptor subtype- and protein kinase C isoform-dependence of norepinephrine's actions in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32(7):1193–1209. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Avkiran M, Rowland AJ, Cuello F, Haworth RS. Protein kinase d in the cardiovascular system: emerging roles in health and disease. Circ Res. 2008;102(2):157–163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.168211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Harrison BC, Kim MS, van Rooij E, et al. Regulation of cardiac stress signaling by protein kinase d1. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(10):3875–3888. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3875-3888.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li J, Kritzer MD, Michel JJ, et al. Anchored p90 ribosomal S6 kinase 3 is required for cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2013;112(1):128–139. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.276162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang Z, Liu R, Townsend PA, Proud CG. p90(RSK)s mediate the activation of ribosomal RNA synthesis by the hypertrophic agonist phenylephrine in adult cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;59:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Backs J, Song K, Bezprozvannaya S, Chang S, Olson EN. CaM kinase II selectively signals to histone deacetylase 4 during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1853–1864. doi: 10.1172/JCI27438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vega RB, Harrison BC, Meadows E, et al. Protein kinases C and D mediate agonist-dependent cardiac hypertrophy through nuclear export of histone deacetylase 5. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(19):8374–8385. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8374-8385.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Woods RL. Cardioprotective functions of atrial natriuretic peptide and B-type natriuretic peptide: a brief review. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31(11):791–794. doi: 10.1111/j.0305-1870.2004.04073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hewett TE, Grupp IL, Grupp G, Robbins J. Alpha-skeletal actin is associated with increased contractility in the mouse heart. Circ Res. 1994;74(4):740–746. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lopez JE, Myagmar BE, Swigart PM, et al. beta-myosin heavy chain is induced by pressure overload in a minor subpopulation of smaller mouse cardiac myocytes. Circulation Research. 2011;109(6):629–638. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hoyer K, Krenz M, Robbins J, Ingwall JS. Shifts in the myosin heavy chain isozymes in the mouse heart result in increased energy efficiency. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42(1):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.King BD, Sack D, Kichuk MR, Hintze TH. Absence of hypertension despite chronic marked elevations in plasma norepinephrine in conscious dogs. Hypertension. 1987;9(6):582–590. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Laks MM, Morady F, Swan HJ. Myocardial hypertrophy produced by chronic infusion of subhypertensive doses of norepinephrine in the dog. Chest. 1973;64(1):75–78. doi: 10.1378/chest.64.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Patel MB, Stewart JM, Loud AV, et al. Altered function and structure of the heart in dogs with chronic elevation in plasma norepinephrine. Circulation. 1991;84(5):2091–2100. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Stewart JM, Patel MB, Wang J, et al. Chronic elevation of norepinephrine in conscious dogs produces hypertrophy with no loss of LV reserve. Am J Physiol. 1992;262(2 Pt 2):H331–339. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Skomedal T, Aass H, Osnes JB, et al. Demonstration of an alpha adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic effect of norepinephrine in human atria. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;233(2):441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Aass H, Skomedal T, Osnes JB, et al. Noradrenaline evokes an alpha-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic effect in human ventricular myocardium. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1986;58(1):88–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1986.tb00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bruckner R, Meyer W, Mugge A, Schmitz W, Scholz H. Alpha-adrenoceptor-mediated positive inotropic effect of phenylephrine in isolated human ventricular myocardium. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984;99(4):345–347. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Curiel R, Perez-Gonzalez J, Brito N, et al. Positive inotropic effects mediated by alpha 1 adrenoceptors in intact human subjects. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1989;14(4):603–615. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198910000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Landzberg JS, Parker JD, Gauthier DF, Colucci WS. Effects of myocardial alpha 1-adrenergic receptor stimulation and blockade on contractility in humans. Circulation. 1991;84(4):1608–1614. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.4.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Skomedal T, Aass H, Geiran O, Osnes JB. Differential effects of cocaine on the positive inotropic effect of noradrenaline mediated by alpha1- and beta-adrenoceptors in failing human myocardium. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;419(2-3):223–230. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00980-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Endoh M, Shimizu T, Yanagisawa T. Characterization of adrenoceptors mediating positive inotropic responses in the ventricular myocardium of the dog. Br J Pharmacol. 1978;64(1):53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1978.tb08640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Puceat M, Terzic A, Clement O, Scamps F, Vogel SM, Vassort G. Cardiac alpha 1-adrenoceptors mediate positive inotropy via myofibrillar sensitization. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13(7):263–265. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90080-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Terzic A, Puceat M, Clement O, Scamps F, Vassort G. Alpha 1-adrenergic effects on intracellular pH and calcium and on myofilaments in single rat cardiac cells. J Physiol. 1992;447:275–292. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chu C, Thai KV, Park KW, et al. Intraventricular and interventricular cellular heterogeneity of inotropic responses to alpha1-adrenergic stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00822.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hirano S, Kusakari Y, J OU, et al. Intracellular mechanism of the negative inotropic effect induced by alpha1-adrenoceptor stimulation in mouse myocardium. J Physiol Sci. 2006;56(4):297–304. doi: 10.2170/physiolsci.RP007306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.McCloskey DT, Rokosh DG, O'Connell TD, Keung EC, Simpson PC, Baker AJ. Alpha(1)-adrenoceptor subtypes mediate negative inotropy in myocardium from alpha(1A/C)-knockout and wild type mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(8):1007–1017. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wang GY, Yeh CC, Jensen BC, Mann MJ, Simpson PC, Baker AJ. Heart failure switches the RV alpha1-adrenergic inotropic response from negative to positive. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(3):H913–920. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00259.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Endoh M, Blinks JR. Actions of sympathomimetic amines on the Ca2+ transients and contractions of rabbit myocardium: reciprocal changes in myofibrillar responsiveness to Ca2+ mediated through alpha- and beta-adrenoceptors. Circ Res. 1988;62(2):247–265. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mohl MC, Iismaa SE, Xiao XH, et al. Regulation of murine cardiac contractility by activation of alpha(1A)-adrenergic receptor-operated Ca(2+) entry. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91(2):310–319. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.O-Uchi J, Komukai K, Kusakari Y, et al. alpha1-adrenoceptor stimulation potentiates L-type Ca2+ current through Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent PK II (CaMKII) activation in rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(26):9400–9405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503569102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.O-Uchi J, Sasaki H, Morimoto S, et al. Interaction of alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes with different G proteins induces opposite effects on cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel. Circ Res. 2008;102(11):1378–1388. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Venema RC, Kuo JF. Protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of troponin I and C-protein in isolated myocardial cells is associated with inhibition of myofibrillar actomyosin MgATPase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(4):2705–2711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Foo RS, Mani K, Kitsis RN. Death begets failure in the heart. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(3):565–571. doi: 10.1172/JCI24569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Communal C, Singh K, Pimentel DR, Colucci WS. Norepinephrine stimulates apoptosis in adult rat ventricular myocytes by activation of the beta-adrenergic pathway. Circulation. 1998;98(13):1329–1334. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.13.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Iwai-Kanai E, Hasegawa K, Araki M, Kakita T, Morimoto T, Sasayama S. alpha- and beta-adrenergic pathways differentially regulate cell type-specific apoptosis in rat cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 1999;100(3):305–311. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zhu H, McElwee-Witmer S, Perrone M, Clark KL, Zilberstein A. Phenylephrine protects neonatal rat cardiomyocytes from hypoxia and serum deprivation-induced apoptosis. Cell death and differentiation. 2000;7(9):773–784. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Aries A, Paradis P, Lefebvre C, Schwartz RJ, Nemer M. Essential role of GATA-4 in cell survival and drug-induced cardiotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(18):6975–6980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401833101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Valks DM, Cook SA, Pham FH, Morrison PR, Clerk A, Sugden PH. Phenylephrine promotes phosphorylation of Bad in cardiac myocytes through the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 and protein kinase A. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(7):749–763. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Liang Q, Wiese RJ, Bueno OF, Dai YS, Markham BE, Molkentin JD. The transcription factor GATA4 is activated by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1- and 2-mediated phosphorylation of serine 105 in cardiomyocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(21):7460–7469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7460-7469.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Pu WT, Ma Q, Izumo S. NFAT transcription factors are critical survival factors that inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis during phenylephrine stimulation in vitro. Circ Res. 2003;92(7):725–731. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069211.82346.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Chan T, Dash R, Simpson P. An alpha-1A-adrenergic receptor subtype agonist prevents cardiomyopathy without increasing blood pressure (abstract) Circulation. 2008;118:S533 [Google Scholar]

- 151.Dash R, Chung J, Chan T, et al. A molecular MRI probe to detect treatment of cardiac apoptosis in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(4):1152–1162. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Banerjee A, Locke-Winter C, Rogers KB, et al. Preconditioning against myocardial dysfunction after ischemia and reperfusion by an alpha 1-adrenergic mechanism. Circ Res. 1993;73(4):656–670. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.4.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Mitchell MB, Meng X, Ao L, Brown JM, Harken AH, Banerjee A. Preconditioning of isolated rat heart is mediated by protein kinase C. Circ Res. 1995;76(1):73–81. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Tejero-Taldo MI, Gursoy E, Zhao TC, Kukreja RC. Alpha-adrenergic receptor stimulation produces late preconditioning through inducible nitric oxide synthase in mouse heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(2):185–195. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kitakaze M, Hori M, Morioka T, et al. Alpha 1-adrenoceptor activation mediates the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning through augmentation of 5'-nucleotidase activity. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(5):2197–2205. doi: 10.1172/JCI117216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Kitakaze M, Hori M, Sato H, et al. Beneficial effects of alpha 1-adrenoceptor activity on myocardial stunning in dogs. Circ Res. 1991;68(5):1322–1339. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.5.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kitakaze M, Hori M, Tamai J, et al. Alpha 1-adrenoceptor activity regulates release of adenosine from the ischemic myocardium in dogs. Circ Res. 1987;60(5):631–639. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]