A nucleolus-tethering system (NoTS) based on nucleolin2 is developed by artificially tethering a protein of interest to the nucleolus for analyzing protein–protein interactions and the initiation of nuclear bodies. The NoTS is used to demonstrate a self-organization model for the biogenesis of photobodies.

Abstract

Protein–protein interactions play essential roles in regulating many biological processes. At the cellular level, many proteins form nuclear foci known as nuclear bodies in which many components interact with each other. Photobodies are nuclear bodies containing proteins for light-signaling pathways in plants. What initiates the formation of photobodies is poorly understood. Here we develop a nucleolar marker protein nucleolin2 (Nuc2)–based method called the nucleolus-tethering system (NoTS) by artificially tethering a protein of interest to the nucleolus to analyze the initiation of photobodies. A candidate initiator is evaluated by visualizing whether a protein fused with Nuc2 forms body-like structures at the periphery of the nucleolus, and other components are recruited to the de novo–formed bodies. The interaction between two proteins can also be revealed through relocation and recruitment of interacting proteins to the nucleolus. Using the NoTS, we test the interactions among components in photobodies. In addition, we demonstrate that components of photobodies such as CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1, photoreceptors, and transcription factors tethered to the nucleolus have the capacity to form body-like structures at the periphery of the nucleolus, which contain other components of photobodies, suggesting a self-organization model for the biogenesis of photobodies.

INTRODUCTION

Many cellular processes are maintained by different interacting proteins assembling dynamically, and so characterizing and visualizing protein–protein interactions is important for understanding biological processes (Galperin et al., 2004; Ciruela, 2008). At the cellular level, many nuclear interacting proteins are usually sequestered in compartments known as nuclear bodies, which form special subnuclear foci containing protein–protein or protein–RNA complexes without membranes that allow free exchanges of components between the bodies and the surrounding nucleoplasm to regulate biological processes (Shaw and Brown, 2004; Dundr and Misteli, 2010; Dundr, 2012). Understanding the assembly processes of nuclear bodies will help to reveal their functions. Three models have been proposed for the assembly of nuclear bodies based on interactions among components in the bodies (Matera et al., 2009; Dundr and Misteli, 2010; Mao et al., 2011b). The first is a stochastic assembly model. Individual components interact stochastically to set up the nuclear bodies in a random manner. In terms of the assembly order, each is equal (Kaiser et al., 2008). The second is an ordered assembly model proposing that individual components take part in the formation of nuclear bodies in a sequential way. The third one is a seeding assembly model in which a component or subset may act as a seed initiating the biogenesis of nuclear bodies (Lallemand-Breitenbach and de The, 2010; Mao et al., 2011a; Shevtsov and Dundr, 2011). In addition, a hybrid model for nuclear body assembly was put forward in which formation of a nuclear body is initiated by a seeding component. This seeding event is not random but is triggered by a cellular process like transcription; other components are then recruited to assemble nuclear bodies randomly or in a self-organized way (Dundr, 2011).

In plants, many nuclear bodies have also been found (Boudonck et al., 1999; Shaw and Brown, 2004; Chen, 2008; Liu et al., 2012; Van Buskirk et al., 2012). Photobodies are plant-specific nuclear bodies containing proteins involved in light-signaling pathways, including photoreceptors, ubiquitylation-related proteins, and transcription factors (Shaw and Brown, 2004; Chen, 2008; Van Buskirk et al., 2012). After photoactivation, the red and far-red photoreceptors (phytochromes, phyA–E) translocate from cytoplasm to nucleus to form discrete foci called photobodies (Yamaguchi et al., 1999; Kircher et al., 2002; Chen, 2008; Yang et al., 2009). The ultraviolet (UV)-A/blue light receptors cryptochromes (cry) 1 and 2 and UV-B receptor UV RESISTANCE LOCUS 8 (UVR8) are also triggered to localize in these subnuclear domains after activation by light (Kleiner et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2008; Favory et al., 2009; Gu et al., 2012). In addition, photobodies contain many other components in light-signaling transduction, and the size and number of photobodies are regulated by different light conditions (Ang et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2003; Jang et al., 2005; Al-Sady et al., 2006; Datta et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2009; Zuo et al., 2011; Van Buskirk et al., 2012). Different models have been proposed for the functions of photobodies. One is the storage model, in which photoactivated phytochromes are sequestrated in photobodies to balance their levels in the nucleoplasm so as to regulate the expression of light-response genes (Matsushita et al., 2003; Palagyi et al., 2010; Rausenberger et al., 2010). Another is the degradation model, suggesting that photobodies act as sites for protein ubiquitylation and degradation, since many components localize in photobodies before their degradation and usually colocalize with the E3 ligase CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1 (COP1; Jang et al., 2005, 2010; Yang et al., 2005; Yi and Deng, 2005; Al-Sady et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2010). The third is the transcription model. As transcriptional regulators localize in photobodies, they may bring their target genes to photobodies for regulation (Yang et al., 2009). Besides, photobodies may also be sites for phytochrome signaling transduction, as the size is affected by light intensity (Chen et al., 2003; Su and Lagarias, 2007). To know how photobodies are assembled is important for understanding their functions in the light-signaling pathways, but methods to study the assembly mechanisms and precise functions of nuclear bodies in plants are quite limited. In mammalian cells, a bacterial Lac operator/repressor (LacO/LacI) tethering system has been successfully applied to study the assembly of nuclear bodies (Kaiser et al., 2008; Mao et al., 2011a; Shevtsov and Dundr, 2011; Dundr, 2013). However, this system is not easily used in plants, especially in transient assays.

Here we develop a nucleolus-tethering system (NoTS) in which a nucleolin2 (Nuc2)-tagged protein is artificially tethered to the nucleolus, and the initiation of nuclear bodies can be monitored by visualizing whether components tethered to the nucleolus form de novo bodies at the periphery of nucleolus and recruit other components into these newly formed bodies in living cells or the protein–protein interactions are monitored by visualizing relocations of interacting proteins to the nucleolus. Using the NoTS, we test the interactions between COP1 and components in photobodies. Of importance, our results demonstrate that components of photobodies, including COP1, photoreceptors, and transcription factors, tethered to nucleolus have the capacity to form body-like structures at the periphery of the nucleolus, which contain other components of photobodies, suggesting a self-organization model for the biogenesis of photobodies.

RESULTS

Strategy of NoTS assay for protein–protein interactions and nuclear body initiation

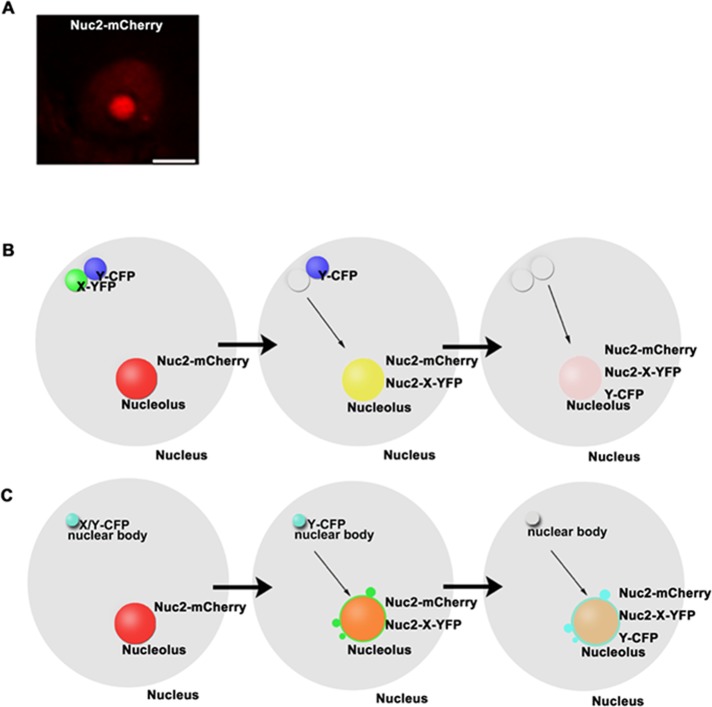

Nuc2 is a marker protein of the nucleolus (Figure 1A), which localizes in the dense fibrillar component and granular component of the nucleolus (Biggiogera et al., 1990; Minguez and Moreno Diaz de la Espina, 1996; Ma et al., 2007). To study protein–protein interactions and assembly of nuclear bodies in vivo, we fused a nuclear protein of interest (X) with Nuc2 and artificially tethered it to the nucleolus. If a target protein (Y) is relocated to the nucleolus, the interaction between X and Y is then revealed (Figure 1B). For the nuclear body initiation assay, if a protein (X) fused with Nuc2 forms body-like structures at the periphery of the nucleolus and other components in a nuclear body follow this fusion protein to these de novo–formed bodies, we predict that X has the ability to initiate the biogenesis of a nuclear body and can be considered as a potential seed in the process of assembly (Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1:

The strategy of NoTS assay for protein–protein interactions and initiation of nuclear bodies. (A) Localization of nucleolin2-mCherry (Nuc2-mCherry) to nucleolus. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Schematic of the NoTS for protein–protein interaction. A protein of interest (X) is fused to Nuc2 and YFP to make Nuc2-X-YFP, which is tethered to the nucleolus. The interacting protein (Y) of X is fused to CFP. The protein–protein interaction between X and Y is indicated by relocation and colocalization of Nuc2-X-YFP and Y-CFP in the nucleolus, which is labeled by Nuc2-mCherry. (C) Schematic of the NoTS for nuclear body initiation. A component (X) is fused to Nuc2 and YFP to make Nuc2-X-YFP. Other components (Y) of the nuclear bodies are fused to CFP. In addition to diffuse signals in the nucleolus, Nuc2-X-YFP– and Y-CFP–containing nuclear bodies are formed de novo at the periphery of the nucleolus, which is labeled by Nuc2-mCherry.

Because the NoTS system is based on exogenously overexpressed Nuc2 fusion proteins and nucleolin plays an essential role in the ribosome biogenesis, such as RNA polymerase I (Pol I)–mediated transcription (Mongelard and Bouvet, 2007; Pontvianne et al., 2007; Rickards et al., 2007; Tajrishi et al., 2011; Layat et al., 2012), we tested whether the exogenous expression of Nuc2 fusion proteins affects Pol I–mediated transcription. We compared the expression levels of 18S and 25S rRNAs in 7-d-old seedlings between the wild type (Col-0) and a transgenic line overexpressing Nuc2-COP1–yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fusion in a cop1-6 mutant background (Nuc2-COP1-YFP ox/cop1-6; Supplemental Figure S1B). The result showed that expression of 18S and 25S rRNAs in the transgenic line has a similar level to that of wild type.

To evaluate the tethering efficiency of Nuc2 to the nucleolus in protein–protein interactions, we tested the interaction between the plant microRNA (miRNA) processing enzyme DICER-LIKE 1 (DCL1) and its partner HYPONASTIC LEAVES1 (HYL1), a double-strand RNA–binding protein. DCL1 interacts with HYL1 in nuclear dicing bodies (D-bodies) during miRNA processing (Schauer et al., 2002; Carrington and Ambros, 2003; Kurihara and Watanabe, 2004; Hiraguri et al., 2005; Kurihara et al., 2006; Fang and Spector, 2007; Song et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2012). At the cellular level, HYL1 concentrates in D-bodies, not colocalizing with Nuc2 (Supplemental Figure S2A). When fused with Nuc2, HYL1 was tethered to the nucleolus. Colocalization analysis showed that DCL1 was successfully recruited to the periphery of the nucleolus because of the interaction between DCL1 and HYL1 (Supplemental Figure S2B). The relocation of DCL1, a large protein that contains 1910 amino acids and has a molecular weight of ∼214 kDa (Schauer et al., 2002), indicated the tethering effectiveness of Nuc2 to the nucleolus and successful recruitment of the interacting protein through the tethered component.

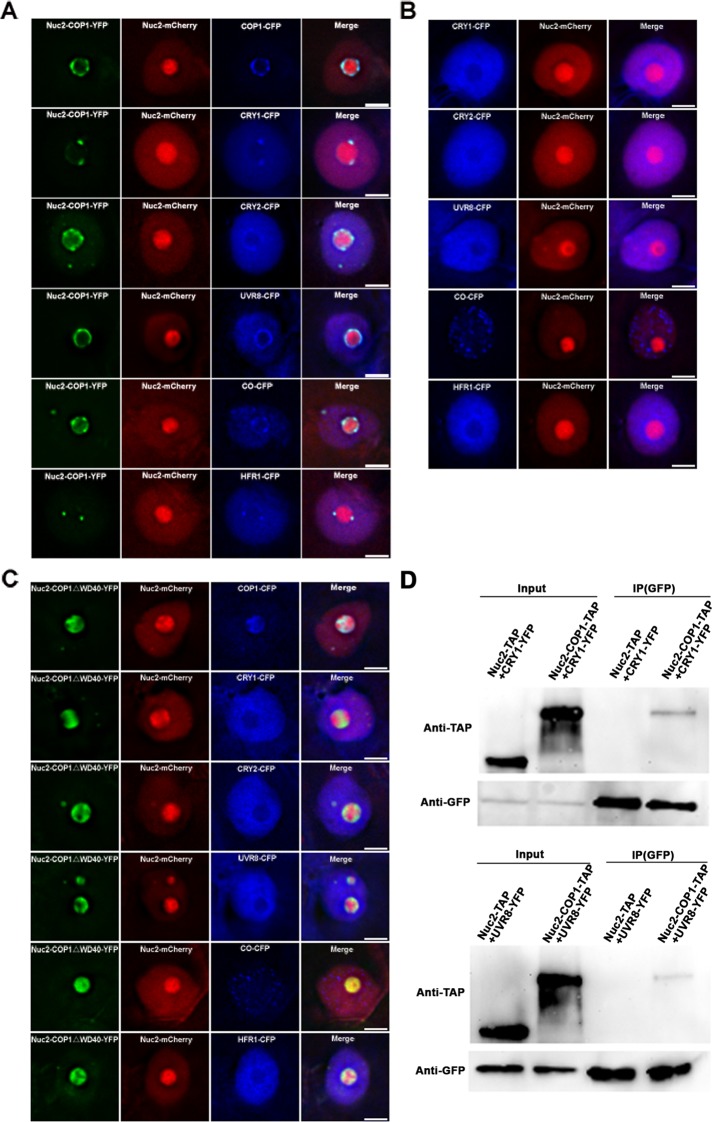

COP1 interacts with components of photobodies in vivo

COP1 acts as a central switch in controlling development of Arabidopsis seedlings through interactions with upstream photoreceptors or downstream transcriptional regulators for ubiquitylation and degradation (Yi and Deng, 2005; Lau and Deng, 2012). To investigate the protein interaction networks of COP1 in vivo, we fused Nuc2 with COP1, which was tethered to the periphery of the nucleolus (Supplemental Figure S3A). To exclude the possibility that the relocation of COP1 to the nucleolus is due to the interaction of Nuc2 and COP1 instead of the tethering ability of Nuc2, we coinfiltrated COP1-YFP with Nuc2-mCherry into tobacco leaf epidermal cells. The result showed that COP1 formed discrete nuclear bodies in the nucleoplasm without obvious signals in the nucleolus (Supplemental Figure S3B). We then tested the interactions between COP1 and cry1, cry2, UVR8, CONSTANS (CO), and LONG HYPOCOTYL IN FAR-RED 1 (HFR1; Wang et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2001; Jang et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2008; Favory et al., 2009; Zuo et al., 2011; Figure 2). The colocalization showed that COP1 fused to Nuc2 successfully recruited these proteins from nucleoplasm to the nucleolus, indicating interactions between COP1 and these proteins (Figure 2A) not resulting from their possible interactions with Nuc2 (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2:

NoTS assay revealed that COP1 interacts with components of photobodies in vivo through its WD40-repeat domain. (A) COP1 successfully recruited itself and its interacting proteins cry1, cry2, UVR8, CO, and HFR1 to the nucleolus, where Nuc2-COP1 localized due to direct interactions between COP1 and these proteins. The nucleolus is labeled by Nuc2-mCherry. (B) The interacting proteins of COP1 did not colocalize with Nuc2 in the nucleolus. (C) The deletion mutant of COP1 lacking the WD40-repeat domain (COP1∆WD40) failed to recruit its interacting proteins cry1, cry2, UVR8, CO, and HFR1 to the nucleolus, which is labeled by Nuc2-mCherry. Bars, 5 μm. (D) Coimmunoprecipitation of Nuc2-COP1-TAP and CRY1-YFP or UVR8-YFP coexpressed in tobacco epidermal cells. Nuc2-TAP was used as a control. Nuc2-COP1-TAP but not Nuc2-TAP was detected in the immunoprecipitated samples. IP, immunoprecipitation.

COP1 interacts with many proteins through its WD40-repeat domain (Holm et al., 2001). To further exclude the possibility that the recruitment of these proteins is the result of Nuc2-interacting proteins and confirm the interactions between COP1 and these proteins, we deleted the WD40-repeat domain in COP1 and fused it with Nuc2 (Nuc2-COP1∆WD40; Figure 2C). The NoTS assay showed that these proteins failed to be recruited by Nuc2-COP1∆WD40 to the nucleolus, indicating that no interactions exist between Nuc2-COP1∆WD40 and these proteins. In contrast, COP1 itself was successfully recruited to the nucleolus even when the WD40-repeat domain was deleted, as COP1 dimerizes through its coiled-coil domain (Bianchi et al., 2003; Yi and Deng, 2005; Figure 2C). However, the photoreceptors phytochrome A (phyA) and phytochrome B (phyB) did not follow Nuc2-COP1 to the nucleolus (Supplemental Figure S4, A and B), indicating that the interactions between COP1 and phyA or phyB were indirect or weak, consistent with previous studies showing that accessory factors are needed to enhance the interactions between COP1 and phyA or phyB (Zhou et al., 2005; Leivar et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2009; Jang et al., 2010). In addition, we used coimmunoprecipitation to demonstrate the interactions between Nuc2-COP1 and its interacting proteins in vivo (Figure 2D). Nuc2-COP1–tandem affinity purification (TAP) fusion proteins were detected in the coimmunoprecipitated samples when coinfiltrated with CRY1-YFP or UVR8-YFP in tobacco leaves, whereas Nuc2-TAP fusion was not detected, indicating that Nuc2-COP1 interacts with cry1 and UVR8 physically and these interactions are mediated by COP1, not Nuc2 or Nuc2-interacting proteins.

The initiation of photobodies follows a self-organization model

Photobodies contain proteins with different functions, including photoreceptors, degradation proteins, and transcription regulators (Chen, 2008; Van Buskirk et al., 2012). To evaluate the ability of components for the formation of a photobody de novo, we tethered different components to the nucleolus by Nuc2. The components include photoreceptors phyB, cry1, cry2, degradation-related protein COP1, and transcription factors ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5) and phytochrome-interacting factor 7 (PIF7). COP1, phyB, cry1, cry2, and PIF7 fused to Nuc2 formed foci at the periphery of the nucleolus in addition to diffuse signals in the nucleolus (Figure 3A). In contrast, HY5 was tethered into the nucleolus, and no bodies appeared at the periphery of the nucleolus (Figure 3A), consistent with previous reports that HY5 shows a diffuse signal in nuclei when expressed alone and requires the HY5-interacting factor COP1 for deposition into nuclear bodies (Ang et al., 1998; Datta et al., 2006). To test whether the de novo–formed foci at the periphery of the nucleolus are photobodies, we investigated whether these bodies contain other components of photobodies (Figure 3B). As shown in Figure 2A, COP1, cry1, cry2, UVR8, and CO colocalized with Nuc2-COP1 in the de novo–formed bodies at the periphery of the nucleolus. In turn, COP1 concentrated in the newly formed bodies containing Nuc2-cry1 or Nuc2-cry2 (Figure 3B). In addition, PIF7 and phyB colocalized in the Nuc2-phyB–containing bodies, and phyB localized in Nuc2-PIF7–containing bodies (Figure 3B). Moreover, when marker proteins of D-bodies (DCL1) and nuclear speckles (SCL33) were coexpressed with Nuc2-COP1 (Figure 3C), the newly formed body had no merge with D-bodies or nuclear speckles marked by cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)–DCL1 or SCL33-CFP, respectively. To compare the kinetics of de novo–formed bodies at the periphery of the nucleolus and the normally distributed photobodies, we performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) in tobacco epidermal cells expressing Nuc2-COP1-YFP or COP1-YFP (Supplemental Figure S5, A–D).The result showed that the kinetics of these newly formed bodies is similar to that of COP1 photobodies, both having a slow recovery rate compared with that of SR33-YFP in plant nuclear speckles (Fang et al., 2004). To investigate whether these periphery-localized bodies are functional photobodies, we generated transgenic plants overexpressing Nuc2-COP1-YFP fusion protein in cop1-6 mutant background (Nuc2-COP1-YFP ox/cop1-6) and found that these plants with relocated bodies can complement the phenotype of the cop1-6 mutant, which is greatly reduced in size and seed set for the mature plants under light conditions (Supplemental Figure S5E), suggesting that the de novo–formed bodies contain functional components of the light-signaling pathway to regulate light-signaling transduction. Taking the results together, this demonstrates that the newly formed bodies at the periphery of the nucleolus are truly functional photobodies. Because many components have the ability to form photobodies, to evaluate their nucleation efficiency, we tethered them to the nucleolus by Nuc2 and calculated the percentage of cells containing newly formed photobodies. As shown in Figure 3D, COP1 has the highest efficiency of photobody initiation (up to 87%). PhyB is lower than cryptochromes, possibly because other factors are required for the formation of phyB nuclear bodies, such as HEMERA, which accumulates when interacting with photoactivated phyB and is involved in the assembly of photobodies and the turnover of PIFs to establish plant photomorphogenesis (Chen et al., 2010; Galvao et al., 2012). These results indicate that many components of photobodies, such as degradation-related proteins, transcription factors, and photoreceptors, have capacity for assembly of photobodies, suggesting a self-organization model for the nucleation of photobodies.

FIGURE 3:

NoTS assay revealed that the initiation of photobodies follows a self-organization model. (A) COP1, PIF7, phyB, cry1, and cry2 were able to form nuclear bodies de novo at the periphery of the nucleolus when fused with Nuc2. (B) The nuclear bodies formed de novo at the periphery of the nucleolus contained components of photobodies. The nucleolus is labeled by Nuc2-mCherry. (C) Nucleated body by Nuc2-COP1-YFP at the periphery of the nucleolus did not colocalize with D-bodies or nuclear speckles marked by CFP-DCL1 or SCL33-CFP, respectively. (D) Quantitative analysis of efficiency of de novo photobody formation via tethering of different components to the nucleolus by Nuc2. Values represent averages (n = 110–200 cells) from three independent experiments. Bars, 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

The NoTS reveals protein–protein interactions in living cells through the relocation of interacting proteins to the nucleolus by the Nuc2 fusion protein. It is a result of direct protein–protein interactions and avoids local high concentrations of these interacting proteins at the interacting sites, which can easily yield a false-positive result, a major issue for other fluorescence-based methods, such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer and bimolecular fluorescence complementation, in protein–protein interaction assays (Piston and Kremers, 2007; Kerppola, 2008a, b; Padilla-Parra and Tramier, 2012). The NoTS was used only for detecting the interactions among nucleoplasmic proteins, and it would be of interest to apply the NoTS for the protein–protein interaction assay of cytoplasmic proteins fused with nuclear localization signals.

Given the proposed assembly models for nuclear bodies, we immobilized different components of photobodies through Nuc2’s tethering ability to the nucleolus. Several fusion proteins were tethered to the nucleolus and concentrated as discrete foci at the periphery, which have similar size and morphology to endogenous photobodies (Figure 3A). Colocalization, kinetics, and phenotype complementation analysis suggested that these de novo–formed bodies contain the components of photobodies (Figures 2A and 3B and Supplemental Figure S5), demonstrating that the newly formed bodies are truly functional photobodies and many components have the capacity to initiate the biogenesis of photobodies, suggesting a self-organization model for the formation of photobodies.

COP1 acts as a central switch in photomorphogenesis (Yi and Deng, 2005; Lau and Deng, 2012); it interacts with many components in photobodies in vivo (Figure 2A), and it has the highest initiation efficiency (Figure 3D), implying that photobodies might be the degradation sites in the light-signaling pathway, as COP1 is an E3 ligase (Yi and Deng, 2005; Lau and Deng, 2012). Previously photobodies were proposed as degradation sites because some components, such as FAR-RED ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL1 (FHY1) and PIFs, localize to photobodies before their degradation (Al-Sady et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2009; Van Buskirk et al., 2012). In addition, members of the Suppressor of the phytochrome A-105 family, which form a substrate recognition complex with COP1, colocalize with COP1 in photobodies. Genetic analysis of an Hmr (HEMERA) mutant with a defect in the formation of photobodies also indicated that photobodies play a role in protein turnover (Chen et al., 2010; Galvao et al., 2012). As for cry2 nuclear bodies, it was suggested that the degradation of cry2 is involved (Yu et al., 2009). In animals, subnuclear foci named clastosomes contain components involved in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Lafarga et al., 2002). It would be of interest to investigate the functional relationships between photobodies and clastosomes.

In summary, we developed the NoTS and used it successfully to study protein–protein interactions. In addition, the NoTS provides a useful way to probe the biogenesis of nuclear bodies based on recruitment of components and de novo formation of nuclear bodies. Because nucleolin is a conserved protein in plants and vertebrates, the NoTS might have broad applications in different cell lines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials

The Arabidopsis wild-type (Col-0), cop1-6 mutant, and transgenic plants overexpressing COP1-YFP or Nuc2-COP1-YFP under the control of 35S promoter in cop1-6 background and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) were all grown in a greenhouse at 22°C under 16-h light/8-h dark conditions.

Constructs

The coding region of AtNucleolin2 (At3g18610) was amplified by PCR from cDNA of Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 and subcloned into EcoRI/SalI-treated vector pC131-35S-N1-mCherry to generate pC131-35S-nucleolin2-mCherry. Primers 5′-NNNGAATTCATGGGCAAGTCTAGTAAGAAATCC-3′ and 5′-NNNGTCGACAGCTCCACCTCCACCTCCGACCGGTCGCTCTTCATCATTAAAGACCGTCTTC-3′ were used to amplify the nucleolin2-linker fragment, which was then subcloned into EcoRI/SalI-treated vector pC131-35S-N1-YFP (Fang and Spector, 2007) to generate pC131-35S-nucleolin2-linker-YFP. The sequence of the flexible linker is CGACCGGTCGGAGGTGGAGGTGGAGCT. The coding sequences of COP1 (At2g32950), phyA (At1g09570), phyB (At2g18790), cry1 (At4g08920), cry2 (At1g04400), UVR8 (At5g63860), CO (At5g15840), HFR1 (At1g02340), HEMERA (At2g34640), HY5 (At5g11260), and PIF7 (At5g61270) were amplified by PCR from cDNAs and subcloned into pC131-35S-N1-CFP. These fragments were then subcloned into pC131-35S-nucleolin2-linker-YFP to generate different fusions. For COP1∆WD40 fragment, the PCR primers used were 5′-NNNGTCGACATGGAAGAGATTTCGACGGATCC-3′ and 5′-NNNACTAGTATAATTGCCTACAAAATTTCCTCCTC-3′, and then it was subcloned into SalI/SpeI-treated vector pC131-35S-nucleolin2-linker-YFP. The coding region of HYL1(At1g09700) was amplified by PCR from cDNA and subcloned into SalI/SpeI-treated vector pC131-35S-nucleolin2-linker-YFP. Plasmids pC131-35S-CFP-DCL1 and pHYL1-HYL1-YFP fusions were described previously (Fang and Spector, 2007). All sequences amplified were confirmed by sequencing. The primers used for the constructs in this study are summarized in Supplemental Table S1.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from 7-d-old seedlings using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany). RNAs (∼1 μg) were used as templates for reverse transcription using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover Kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) following the manufacturer's instructions. Then the cDNAs were used as the template for quantitative PCR (qPCR) using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time system. All PCRs were performed by preincubation for 5 min at 95°C, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 20 s, annealing at 56°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. Each reaction was repeated three times. The expression level of actin2 was used for data normalization. Primers used for qPCR are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Microscopy analysis

The constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation. Transient expressions or coexpressions in tobacco (N. tabacum) leaves were performed as described (Fang and Spector, 2010). Forty-eight hours after infiltration, leaf disks in infiltrated areas were subjected to microscopy analysis using a DeltaVision Personal DV system (Applied Precision) equipped with an UPLANAPO water immersion objective lens (60×/1.20 numerical aperture; Olympus, Japan). Image collection and processing were described previously (Fang and Spector, 2007, 2010; Shi et al., 2011). For each experiment, at least 30 nuclei were visualized.

For initiation efficiency analysis, Nuc2-X-YFP (X is the component of photobodies) was introduced into tobacco leave cells by infiltration, and the percentage of cells with de novo–formed photobodies was calculated in 10 stochastic areas. Each sample was repeated three times.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay

After infiltration for 48 h, tobacco leaves coexpressing Nuc2-COP1-TAP and CRY1-YFP or UVR8-YFP, Nuc2-TAP, and CRY1-YFP or UVR8-YFP were ground in liquid nitrogen, and total proteins were extracted as described (Lee et al., 2007) using extraction buffer (0.4 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1× protease inhibitor [Roche, Basel, Switzerland]). They were filtered through four-layer Miracloth (Millipore) twice, and 2-ml samples were taken to incubate with 60 μl of anti-GFP magnetic beads (MBL, Japan) at 4°C for 2 h to capture proteins associated with CRY1-YFP or UVR8-YFP. The beads were washed five times with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.01% Triton X-100, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1× protease inhibitor [Roche]). The bound proteins were eluted by heating at 95°C for 10 min and analyzed by Western blot using anti-GFP (Sigma-Aldrich) and anti-TAP (Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies, respectively.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

GV3101 strains harboring Nuc2-COP1-YFP or COP1-YFP were injected into tobacco leaves. After 48 h, the infiltrated areas were subjected to FRAP analysis using a Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) SP8 confocal microscope equipped with an HC PL APO CS2 40×/1.30 objective lens. YFP was excited by a 514-nm argon laser, and the emission was at 580 nm. For photobleaching, the 514-nm laser was set to 100% laser power; for image taking, the laser power was at 5% of an argon laser with 0.79% output power. Three prebleach images were acquired with an interval of 1 s. After bleaching, images were captured with an interval of 10 s. The FRAP recovery curves were obtained by calculating the relative fluorescence intensity as described previously (Phair and Misteli, 2000; Fang et al., 2004). Each experiment was repeated at least three times independently.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hongtao Liu for the cop1-6 mutant; S. Nagawa for help in setting up the FRAP experiment; the Arabidopsis Information Resource for providing cDNAs of nucleolin2, COP1, phyA, phyB, cry1, cry2, UVR8, CO, HFR1, HEMERA, HY5, PIF7, and HYL1; and Kaiyao Huang and members of the Fang lab for insightful discussions. This work was supported by grants to Y.F. from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31171168 and 91319304) and the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, 2012CB910503).

Abbreviation used:

- NoTS

nucleolus-tethering system

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E13-09-0527) on February 19, 2014.

REFERENCES

- Al-Sady B, Ni W, Kircher S, Schafer E, Quail PH. Photoactivated phytochrome induces rapid PIF3 phosphorylation prior to proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol Cell. 2006;23:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang LH, Chattopadhyay S, Wei N, Oyama T, Okada K, Batschauer A, Deng XW. Molecular interaction between COP1 and HY5 defines a regulatory switch for light control of Arabidopsis development. Mol Cell. 1998;1:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi E, Denti S, Catena R, Rossetti G, Polo S, Gasparian S, Putignano S, Rogge L, Pardi R. Characterization of human constitutive photomorphogenesis protein 1, a RING finger ubiquitin ligase that interacts with Jun transcription factors and modulates their transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19682–19690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggiogera M, Burki K, Kaufmann SH, Shaper JH, Gas N, Amalric F, Fakan S. Nucleolar distribution of proteins B23 and nucleolin in mouse preimplantation embryos as visualized by immunoelectron microscopy. Development. 1990;110:1263–1270. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudonck K, Dolan L, Shaw PJ. The movement of coiled bodies visualized in living plant cells by the green fluorescent protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2297–2307. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.7.2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington JC, Ambros V. Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science. 2003;301:336–338. doi: 10.1126/science.1085242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. Phytochrome nuclear body: an emerging model to study interphase nuclear dynamics and signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Galvao RM, Li M, Burger B, Bugea J, Bolado J, Chory J. Arabidopsis HEMERA/pTAC12 initiates photomorphogenesis by phytochromes. Cell. 2010;141:1230–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Schwab R, Chory J. Characterization of the requirements for localization of phytochrome B to nuclear bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14493–14498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1935989100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruela F. Fluorescence-based methods in the study of protein-protein interactions in living cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Hettiarachchi GH, Deng XW, Holm M. Arabidopsis CONSTANS-LIKE3 is a positive regulator of red light signaling and root growth. Plant Cell. 2006;18:70–84. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Han MH, Fedoroff N. The RNA-binding proteins HYL1 and SE promote accurate in vitro processing of pri-miRNA by DCL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9970–9975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803356105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundr M. Seed and grow: a two-step model for nuclear body biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:605–606. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundr M. Nuclear bodies: multifunctional companions of the genome. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundr M. Nucleation of nuclear bodies. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1042:351–364. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-526-2_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundr M, Misteli T. Biogenesis of nuclear bodies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000711. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Hearn S, Spector DL. Tissue-specific expression and dynamic organization of SR splicing factors in Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2664–2673. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Spector DL. Identification of nuclear dicing bodies containing proteins for microRNA biogenesis in living Arabidopsis plants. Curr Biol. 2007;17:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Spector DL. Live cell imaging of plants. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010;2010:pdb top68. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favory JJ, et al. Interaction of COP1 and UVR8 regulates UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2009;28:591–601. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin E, Verkhusha VV, Sorkin A. Three-chromophore FRET microscopy to analyze multiprotein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2004;1:209–217. doi: 10.1038/nmeth720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvao RM, Li M, Kothadia SM, Haskel JD, Decker PV, Van Buskirk EK, Chen M. Photoactivated phytochromes interact with HEMERA and promote its accumulation to establish photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1851–1863. doi: 10.1101/gad.193219.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu NN, Zhang YC, Yang HQ. Substitution of a conserved glycine in the PHR domain of Arabidopsis cryptochrome 1 confers a constitutive light response. Mol Plant. 2012;5:85–97. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraguri A, Itoh R, Kondo N, Nomura Y, Aizawa D, Murai Y, Koiwa H, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Fukuhara T. Specific interactions between Dicer-like proteins and HYL1/DRB-family dsRNA-binding proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;57:173–188. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-6853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm M, Hardtke CS, Gaudet R, Deng XW. Identification of a structural motif that confers specific interaction with the WD40 repeat domain of Arabidopsis COP1. EMBO J. 2001;20:118–127. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IC, Henriques R, Seo HS, Nagatani A, Chua NH. Arabidopsis PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR proteins promote phytochrome B polyubiquitination by COP1 E3 ligase in the nucleus. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2370–2383. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IC, Yang JY, Seo HS, Chua NH. HFR1 is targeted by COP1 E3 ligase for post-translational proteolysis during phytochrome A signaling. Genes Dev. 2005;19:593–602. doi: 10.1101/gad.1247205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser TE, Intine RV, Dundr M. De novo formation of a subnuclear body. Science. 2008;322:1713–1717. doi: 10.1126/science.1165216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerppola TK. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis as a probe of protein interactions in living cells. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008a;37:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerppola TK. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation: visualization of molecular interactions in living cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2008b;85:431–470. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)85019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher S, Gil P, Kozma-Bognar L, Fejes E, Speth V, Husselstein-Muller T, Bauer D, Adam E, Schafer E, Nagy F. Nucleocytoplasmic partitioning of the plant photoreceptors phytochrome A, B, C, D, and E is regulated differentially by light and exhibits a diurnal rhythm. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1541–1555. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner O, Kircher S, Harter K, Batschauer A. Nuclear localization of the Arabidopsis blue light receptor cryptochrome 2. Plant J. 1999;19:289–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y, Takashi Y, Watanabe Y. The interaction between DCL1 and HYL1 is important for efficient and precise processing of pri-miRNA in plant microRNA biogenesis. RNA. 2006;12:206–212. doi: 10.1261/rna.2146906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y, Watanabe Y. Arabidopsis micro-RNA biogenesis through Dicer-like 1 protein functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12753–12758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403115101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafarga M, Berciano MT, Pena E, Mayo I, Castano JG, Bohmann D, Rodrigues JP, Tavanez JP, Carmo-Fonseca M. Clastosome: a subtype of nuclear body enriched in 19S and 20S proteasomes, ubiquitin, and protein substrates of proteasome. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2771–2782. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand-Breitenbach V, de The H. PML nuclear bodies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000661. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau OS, Deng XW. The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layat E, Saez-Vasquez J, Tourmente S. Regulation of Pol I-transcribed 45S rDNA and Pol III-transcribed 5S rDNA in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:267–276. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, He K, Stolc V, Lee H, Figueroa P, Gao Y, Tongprasit W, Zhao H, Lee I, Deng XW. Analysis of transcription factor HY5 genomic binding sites revealed its hierarchical role in light regulation of development. Plant Cell. 2007;19:731–749. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Monte E, Al-Sady B, Carle C, Storer A, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Quail PH. The Arabidopsis phytochrome-interacting factor PIF7, together with PIF3 and PIF4, regulates responses to prolonged red light by modulating phyB levels. Plant Cell. 2008;20:337–352. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LJ, Zhang YC, Li QH, Sang Y, Mao J, Lian HL, Wang L, Yang HQ. COP1-mediated ubiquitination of CONSTANS is implicated in cryptochrome regulation of flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:292–306. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Shi L, Fang Y. Dicing bodies. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:61–66. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N, Matsunaga S, Takata H, Ono-Maniwa R, Uchiyama S, Fukui K. Nucleolin functions in nucleolus formation and chromosome congression. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2091–2105. doi: 10.1242/jcs.008771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao YS, Sunwoo H, Zhang B, Spector DL. Direct visualization of the co-transcriptional assembly of a nuclear body by noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2011a;13:95–101. doi: 10.1038/ncb2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao YS, Zhang B, Spector DL. Biogenesis and function of nuclear bodies. Trends Genet. 2011b;27:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matera AG, Izaguire-Sierra M, Praveen K, Rajendra TK. Nuclear bodies: random aggregates of sticky proteins or crucibles of macromolecular assembly. Dev Cell. 2009;17:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T, Mochizuki N, Nagatani A. Dimers of the N-terminal domain of phytochrome B are functional in the nucleus. Nature. 2003;424:571–574. doi: 10.1038/nature01837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minguez A, Moreno Diaz de la Espina S. In situ localization of nucleolin in the plant nucleolar matrix. Exp Cell Res. 1996;222:171–178. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongelard F, Bouvet P. Nucleolin: a multiFACeTed protein. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Parra S, Tramier M. FRET microscopy in the living cell: different approaches, strengths and weaknesses. Bioessays. 2012;34:369–376. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palagyi A, Terecskei K, Adam E, Kevei E, Kircher S, Merai Z, Schafer E, Nagy F, Kozma-Bognar L. Functional analysis of amino-terminal domains of the photoreceptor phytochrome B. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1834–1845. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.153031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phair RD, Misteli T. High mobility of proteins in the mammalian cell nucleus. Nature. 2000;404:604–609. doi: 10.1038/35007077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piston DW, Kremers GJ. Fluorescent protein FRET: the good, the bad and the ugly. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontvianne F, Matia I, Douet J, Tourmente S, Medina FJ, Echeverria M, Saez-Vasquez J. Characterization of AtNUC-L1 reveals a central role of nucleolin in nucleolus organization and silencing of AtNUC-L2 gene in Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:369–379. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausenberger J, Hussong A, Kircher S, Kirchenbauer D, Timmer J, Nagy F, Schafer E, Fleck C. An integrative model for phytochrome B mediated photomorphogenesis: from protein dynamics to physiology. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickards B, Flint SJ, Cole MD, LeRoy G. Nucleolin is required for RNA polymerase I transcription in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:937–948. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01584-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer SE, Jacobsen SE, Meinke DW, Ray A. DICER-LIKE1: blind men and elephants in Arabidopsis development. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:487–491. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ, Brown JW. Plant nuclear bodies. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevtsov SP, Dundr M. Nucleation of nuclear bodies by RNA. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:167–173. doi: 10.1038/ncb2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Wang J, Hong F, Spector DL, Fang Y. Four amino acids guide the assembly or disassembly of Arabidopsis histone H3.3-containing nucleosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10574–10578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017882108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Han MH, Lesicka J, Fedoroff N. Arabidopsis primary microRNA processing proteins HYL1 and DCL1 define a nuclear body distinct from the Cajal body. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5437–5442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YS, Lagarias JC. Light-independent phytochrome signaling mediated by dominant GAF domain tyrosine mutants of Arabidopsis phytochromes in transgenic plants. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2124–2139. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.051516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajrishi MM, Tuteja R, Tuteja N. Nucleolin: the most abundant multifunctional phosphoprotein of nucleolus. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4:267–275. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.3.14884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buskirk EK, Decker PV, Chen M. Photobodies in light signaling. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:52–60. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Ma LG, Li JM, Zhao HY, Deng XW. Direct interaction of Arabidopsis cryptochromes with COP1 in light control development. Science. 2001;294:154–158. doi: 10.1126/science.1063630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi R, Nakamura M, Mochizuki N, Kay SA, Nagatani A. Light-dependent translocation of a phytochrome B-GFP fusion protein to the nucleus in transgenic Arabidopsis. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:437–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HQ, Tang RH, Cashmore AR. The signaling mechanism of Arabidopsis CRY1 involves direct interaction with COP1. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2573–2587. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Lin R, Sullivan J, Hoecker U, Liu B, Xu L, Deng XW, Wang H. Light regulates COP1-mediated degradation of HFR1, a transcription factor essential for light signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:804–821. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.030205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SW, Jang IC, Henriques R, Chua NH. FAR-RED ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL1 and FHY1-LIKE associate with the Arabidopsis transcription factors LAF1 and HFR1 to transmit phytochrome A signals for inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1341–1359. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi C, Deng XW. COP1—from plant photomorphogenesis to mammalian tumorigenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu XH, Sayegh R, Maymon M, Warpeha K, Klejnot J, Yang HY, Huang J, Lee J, Kaufman L, Lin CT. Formation of nuclear bodies of Arabidopsis CRY2 in response to blue light is associated with its blue light-dependent degradation. Plant Cell. 2009;21:118–130. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou QQ, Hare PD, Yang SW, Zeidler M, Huang LF, Chua NH. FHL is required for full phytochrome A signaling and shares overlapping functions with FHY1. Plant J. 2005;43:356–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Z, Liu H, Liu B, Liu X, Lin C. Blue light-dependent interaction of CRY2 with SPA1 regulates COP1 activity and floral initiation in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2011;21:841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.