Abstract

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) has been suggested as an essential mechanism for the in vivo activity of cetuximab, an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeting therapeutic antibody. Thus, enhancing the affinity of human IgG1 antibodies to natural killer (NK) cell-expressed FcγRIIIa by glyco- or protein-engineering of their Fc portion has been demonstrated to improve NK cell-mediated ADCC and to represent a promising strategy to improve antibody therapy. However, human polymorphonuclear (PMN) effector cells express the highly homologous FcγRIIIb isoform, which is described to be ineffective in triggering ADCC. Here, non-fucosylated or protein-engineered anti-EGFR antibodies with optimized FcγRIIIa affinities demonstrated the expected benefit in NK cell-mediated ADCC, but did not mediate ADCC by PMN, which could be restored by FcγRIIIb blockade. Furthermore, eosinophils and PMN from paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria patients that expressed no or low levels of FcγRIIIb mediated effective ADCC with FcγRIII-optimized anti-EGFR antibody. Additional experiments with double FcγRIIa/FcγRIII-optimized constructs demonstrated enhanced PMN-mediated ADCC compared with single FcγRIII-optimized antibody. In conclusion, our data demonstrate that FcγRIIIb engagement impairs PMN-mediated ADCC activity of FcγRIII-optimized anti-EGFR antibodies, while further optimization of FcγRIIa binding significantly restores PMN recruitment.

Keywords: ADCC, EGFR, Fc-engineering, FcγRIII, FcγRIIIb, FcγRIIa, PMN, cetuximab

Introduction

Tumor therapy with monoclonal antibodies is gaining increasing importance for many cancers, although the therapeutic benefit for individual patients is often limited1 and the economic burden for health care providers continues to rise.2 An improved understanding of the clinically-relevant mechanisms of action for therapeutic antibodies may provide rational approaches to increase their clinical efficacy.3 This understanding, however, is still incomplete for many widely applied antibodies, although progress has been achieved over the years. For example, the monoclonal antibodies rituximab and trastuzumab significantly lost therapeutic activity in mice with genetically disrupted Fcγ receptor expression.4 More recent studies demonstrated that intact Fcγ receptor signaling, and not merely Fcγ receptor-mediated antigen crosslinking, is required for therapeutic antibody efficacy in xenogeneic models.5 Furthermore, syngeneic B cell depletion was critically affected by antibody isotypes and specific Fcγ receptor isoforms.6 Further analyses revealed that affinity ratios for activating vs. inhibitory Fcγ receptors determined the therapeutic efficacy of certain tumor-directed antibodies in mice.7 In humans, the strongest evidence for Fcγ receptor-mediated mechanisms of action was derived from clinical studies that demonstrated associations between clinical responses and expression of certain alloforms of activating Fcγ receptors.8 For example, expression of the FcγRIIa-131H or FcγRIIIa-158V alloforms was correlated with increased clinical benefit from trastuzumab or rituximab therapy.9,10 Notably, Fcγ receptor polymorphisms were not associated with response to rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients, suggesting that different mechanisms of action may contribute depending on disease entity.11 Effector mechanisms for antibodies against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) appear less well defined than for trastuzumab or rituximab, since blockade of ligand binding, inhibition of growth factor signaling and receptor down-modulation appear to contribute.12 Nevertheless, at least two studies reported associations between distinct FcγRIIa (H131R) and FcγRIIIa (V158F) allotypes and clinical responses to therapeutic antibodies targeting EGFR.13,14 Together, there is considerable evidence to suggest that antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) is among the relevant effector mechanisms of many tumor-directed antibodies, including anti-EGFR antibodies. Thus, several approaches to increase the ADCC activity of therapeutic antibodies are being actively investigated.15-17

Protein- and glyco-engineering of antibodies’ Fc portion are among the most well-established technologies to increase the binding affinity of therapeutic antibodies to activating Fcγ receptors.18,19 The glycosylation profile, especially the presence or absence of fucose in the oligosaccharide attached to the N-glycosylation site at Asn297, and specific protein mutations in the Fc part of antibodies have been demonstrated to affect Fc receptor binding and Fc-mediated effector mechanisms.17,20,21 In contrast to natural killer (NK) cell-mediated ADCC, polymorphonuclear cell (PMN)-mediated ADCC by antibody preparations with 25% reduced fucose content was impaired.22 These observations suggested that Fc glyco-engineering by removal of fucose did not universally enhance ADCC activity, but optimized the ADCC activity for a selected effector population, e.g., NK cells at the expense of another potentially important effector population such as PMN.23

The relative contribution of individual effector cell types for the therapeutic activity of monoclonal antibodies in vivo is difficult to assess.24 Studies in mice demonstrated the involvement of distinct effector cell populations to antibodies’ anti-tumoral activities such as NK cells, monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils, which may also depend on many variables such as the antigen, the antibody isotype or format, as well as the utilized mouse model.6,25-30 Involvement of PMN has been suggested, for example, from studies in mouse models in which human colorectal carcinoma cell lines have been transduced to express granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) potentiated tumor infiltration with neutrophils and tumor destruction.31 PMN kill tumor cells by different mechanisms, including phagocytosis and ADCC.23 While phagocytosis of tumor cells has been demonstrated for small CLL cells,32 ADCC may predominate for larger epithelial tumor cells. In patients, the predictive value of different FcγR alleles with FcγRIIIa expressed on NK cells/macrophages and FcγRIIa on monocytes/macrophages and PMN suggest the recruitment of different effector populations for efficient antibody therapy.13 Therefore, it appears important to assess functional consequences of Fc engineering strategies for the cytotoxic potential of different effector cell populations.

In contrast to mice, humans express two isoforms of FcγRIII (CD16), FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIIb, which are highly homologous in their extracellular domains. While both FcγRIII isoforms share low affinities for IgG1, with FcγRIIIb displaying > 8-fold lower affinity for IgG1 compared with FcγRIIIa (Table 1), FcγRIIIa contains a transmembrane region that associates with the FcRγ chain for signaling, while FcγRIIIb is a GPI-linked molecule.33 Expression of FcγRIIIb is restricted to human PMN, and is completely absent in mice. Human FcγRIIIa and its murine homolog FcγRIV are expressed, for example, by human NK cells and murine myeloid cells, respectively. On human PMN, FcγRIIIb is the most abundantly expressed FcR, which is thought to act as the pivotal receptor in binding and clearing circulating immune complexes.34,35

Table 1. FcγR binding of analyzed antibodies.

| FcγRI § | FcγRIIa H131 | FcγRIIa R131 | FcγRIIb | FcγRIIIa V158 | FcγRIIIa F158 | FcγRIIIb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA | Fold | KA | Fold | KA | Fold | KA | Fold | KA | Fold | KA | Fold | KA | Fold | |

| IgG1 wt | 8,333.33 | 1.0 | 1.22 | 1.0 | 1.25 | 1.0 | 0.42 | 1.0 | 4.00 | 1.0 | 0.77 | 1.0 | 0.09 | 1.0 |

| S239D/I332E | 50,000.00 | 6.0 | 5.00 | 4.1 | 10.99 | 8.8 | 7.14 | 17 | 76.92 | 18 | 24.39 | 32 | 1.76 | 18.7 |

| S239D/I332E/G236A | 22,727.27 | 2.7 | 27.78 | 23 | 66.67 | 54 | 6.67 | 16 | 45.45 | 11 | 21.74 | 29 | 1.42 | 15.0 |

| wt-fucose -/ -§ | 8,333.33 | 1.0 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 2.50 | 2.0 | 0.42 | 1.0 | 55.56 | 13.9 | 10.20 | 13.3 | n.d. | - |

KA’s were obtained from global Langmuir fits of Biacore data and are presented in µM−1. Fold = KA(IgG1 wt) / (KA(variant). § KA’s for FcγRI as well as data for wt-fucose −/− were taken from ref. 47.

Previous studies demonstrated enhanced PMN-mediated tumor cell phagocytosis by FcγRIIIa-enhanced antibodies.36,37 Here, we analyzed the effect of enhancing Fc binding to FcγRIII on PMN-mediated ADCC against solid tumor cells. In the case of PMN, improvement of IgG1 affinities for FcγRIII led to impaired ADCC. This impairment was evoked by FcγRIIIb engagement, which did not trigger ADCC. Further studies demonstrate that PMN-mediated ADCC can be restored by enhancing the affinity for the activatory FcγRIIa receptor, suggesting that the FcγRIIa/FcγRIIIb binding ratio of therapeutic antibodies should be considered in the development of next-generation antibodies.

Results

Enhanced FcγRIIIa binding elevates mononuclear cell-mediated but impairs PMN-mediated cytotoxicity

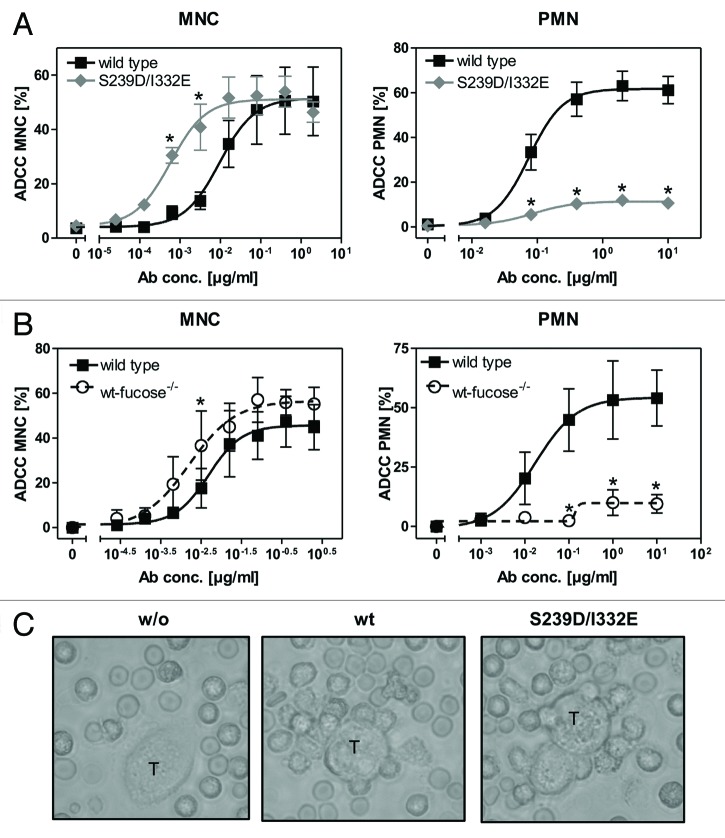

To analyze whether increased FcγRIII affinities of Fc-engineered anti-EGFR antibodies were accompanied by altered cytotoxic activity, 51chromium release assays were performed with A431 target cells and mononuclear cells (MNC) or PMN as effector cells. In comparison to their wild type counterpart, both protein-engineered (S239D/I332E) (Fig. 1A) and non-fucosylated (Fig. 1B) antibodies displayed enhanced ADCC activity with MNC effector cells as indicated by reduced EC50 values (mean EC50wt = 0.008 µg/ml; EC50S239D/I332E = 0.0006 µg/ml; EC50wt-fucose−/− = 0.0016 µg/ml) (left panels). In clear contrast, PMN-mediated ADCC by both Fc-engineered antibodies was almost completely abolished (mean maximum lysis at 10 µg/ml S239D/I332E = 10.6%; mean maximum lysis at 10 µg/ml wt-fucose−/− = 9.6%, while it was triggered by the wild type counterpart (mean maximum lysis at 10 µg/ml = 57.7%) (right panels).

Figure 1. Glyco- or protein-engineered Fc variants optimized for FcγRIII binding mediated enhanced ADCC by MNC, but did not trigger PMN-mediated cytotoxicity. (A, B) ADCC against EGFR-expressing A431 cells was investigated in 3h 51chromium release assays in the presence of increasing concentrations of (A) protein-engineered or (B) glyco-engineered antibodies. ADCC by MNC was enhanced by protein- or glyco-engineered variants compared with wild type antibody (left panel). PMN triggered significant ADCC with wild type antibody, but were completely ineffective with both types of variants (right panel). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments with different donors. * P ≤ 0.05 for wild type vs. engineered antibodies. (C) FcγRIII-engineered antibody mediated tumor cell adhesion by PMN. A431 cell were co-incubated with GM-CSF stimulated PMN from healthy donors at an E:T ratio of 80:1 in the presence or absence of EGFR-targeted antibodies. After 3 h, microscopy was performed at 40x magnification (t = tumor target cells).

Notably, while no accumulation of PMN on the surface of A431 cells was detected in the absence of tumor cell sensitizing antibodies, wild type antibody and the S239D/I332E variant mediated similar PMN attachment to A431 cells (Fig. 1C).

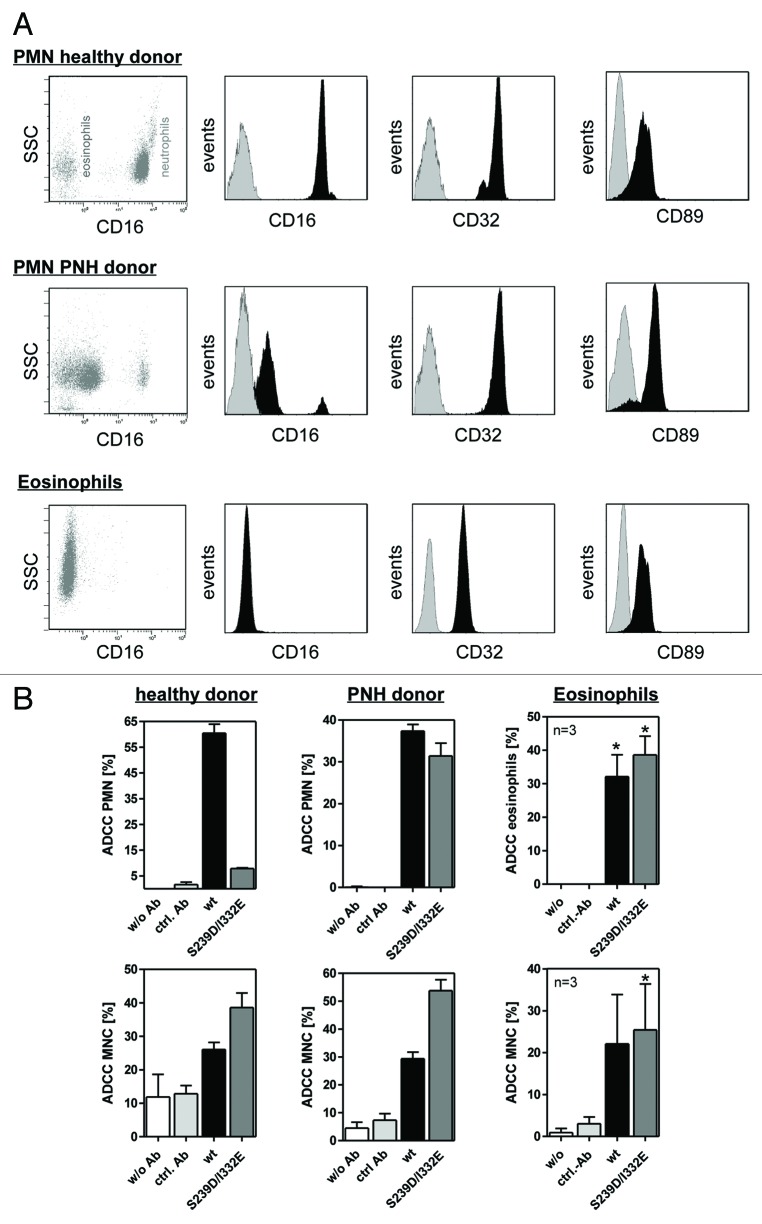

Fc-engineered antibodies effectively recruit FcγRIII-negative granulocytes for ADCC induction

Unstimulated or GM-CSF stimulated human PMN, in contrast to NK cells, express two IgG1 binding FcγRs, FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb, that may have contributed to the observed inhibitory effects. Since both glyco-engineered and protein-engineered antibodies showed dramatically reduced PMN-mediated ADCC and glyco-engineering has been demonstrated to exclusively affect FcγRIII binding (Table 1 and ref. 20), the contribution of FcγRIIIb expression to PMN-mediated ADCC was assessed. Thus, PMN from healthy donors or from PNH donors, as well as eosinophils, were assayed by flow cytometry analyses with regard to their FcγR expression patterns (Fig. 2A). While all three effector sources displayed similar FcγRII and FcαR expression levels, FcγRIII expression significantly differed between these cell populations. High levels of FcγRIIIb were detected on PMN from healthy donors (Fig. 2A, upper panel), but FcγRIIIb was almost absent on PMN from PNH donors (Fig. 2A, middle panel). Furthermore, isolated eosinophils were demonstrated to characteristically be negative for FcγRIII expression (Fig. 2A, lower panel). These three distinct types of granulocytes were further utilized as effector cells in 51chromium release experiments against A431 cells. As presented in Figure 2B, wild type, but not FcγRIII-optimized anti-EGFR antibody S239D/I332E, triggered effective ADCC with PMN from healthy donors, while both antibodies were able to initiate ADCC mediated by PMN from PNH donors and by eosinophils (Fig. 2B, upper panels). In control experiments, both wild type and S239D/I332E antibodies recruited MNC from all three donor groups for induction of ADCC, with the S239D/I332E variant displaying higher cytolysis compared with its wild type counterpart (Fig. 2B, lower panels). No cytotoxicity was detected when target and effector cells were incubated in the absence of antibodies, or with irrelevant control antibodies. Together, these data suggest that high affinity antibody binding to FcγRIIIb impairs PMN-mediated ADCC.

Figure 2. Impaired ADCC activity triggered by Fc-engineered antibody is restored using FcγRIII negative granulocytes. (A) Fc receptor expression was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence. Unfractionated PMN from healthy donors (upper panel), patients with PNH (middle panel) or eosinophils (lower panel) were collected from freshly drawn peripheral blood. PMN from patients with PNH expressed low levels of the GPI-linked FcγRIII (CD16), while FcγRII (CD32) expression was similar to PMN from healthy donors. Unfractionated PMN from healthy donors could be divided into FcγRIII negative eosinophils and FcγRIII positive neutrophils (upper panel). FcγRIII negative eosinophils were isolated from the PMN fraction from healthy donors with eosinophilia and analyzed for FcR expression (lower panel). Eosinophils did express FcγRII (CD32) and FcαRI (CD89). (B) In ADCC experiments against A431 cells, PMN from healthy donors were effective with wild type but not with S239/I332E mutated anti-EGFR antibodies (left panel; all 10 µg/ml). PMN from PNH patients (middle panel) and eosinophils from healthy donors with eosinophilia (right panel) mediated similar ADCC with the S239D/I332E antibody variant and wild type antibody. For the three blood donor types, MNC-mediated killing was enhanced with Fc-engineered antibody (lower panel). In ADCC experiments against A431 cells, MNC-mediated killing was enhanced with Fc-engineered S239D/I332E antibody compared with wild type antibody (left panel). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. * P ≤ 0.05 EGFR-targeted antibody vs. control antibody.

Blockade of FcγRIII on neutrophils restores PMN-mediated ADCC evoked by FcγRIII-optimized anti-EGFR antibody

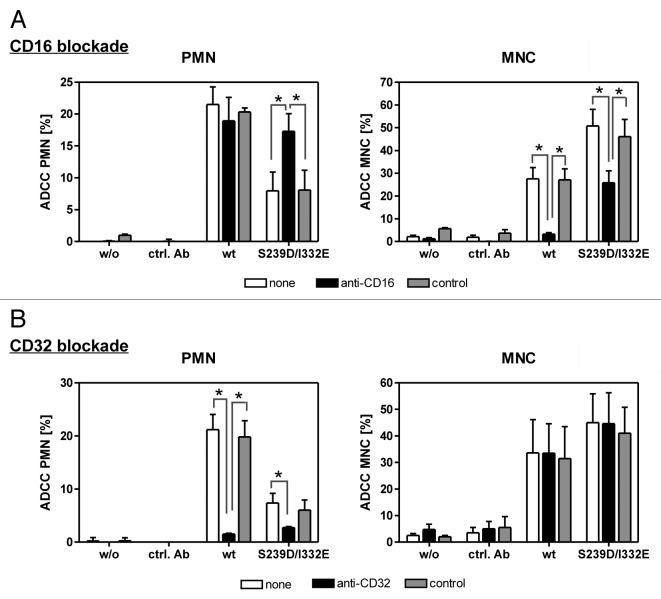

To further elucidate whether enhanced binding to FcγRIIIb on PMN by the S239D/I332E variant caused abrogation of ADCC, 51chromium release experiments against A431 cells were performed in the presence or absence of FcγRIII- or FcγRII-blocking molecules (Fig. 3A and B). Blockade of FcγRIII on PMN significantly enhanced cytotoxic activity elicited by the S239D/I332E variant, but did not affect cytolysis induced by wild type anti-EGFR antibody (Fig. 3A, left panel). As expected, MNC-mediated ADCC triggered by the S239D/I332E variant or by its wild type counterpart was significantly inhibited in the presence of the FcγRIII antagonist (Fig. 3A, right panel). However, FcγRII blockade significantly inhibited PMN-mediated ADCC, but did not affect MNC-mediated ADCC irrespective of the presence of wild type or S239D/I332E-mutated anti-EGFR antibody (Fig. 3B). No cytotoxic activity against A431 cells was observed without sensitizing or with irrelevant control antibodies.

Figure 3. PMN-mediated ADCC is restored by blockade of FcγRIII. In ADCC experiments against A431 cells, PMN from healthy donors were effective with wild type, but not with S239D/I332E mutated anti-EGFR antibody (left panels), while MNC-mediated killing was enhanced with Fc-engineered compared with wild type antibodies (right panels). (A) FcγRIII blockade by anti-CD16 but not by the control antibody restored PMN-mediated ADCC activity (left panel) but impaired MNC-mediated ADCC activity (right panel) triggered by both antibody variants. (B) FcγRII blockade by anti-CD32 almost completely abolished PMN-mediated ADCC activity (left panel) for both antibody variants but did not affect MNC-mediated ADCC activity (right panel). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments with different blood donors. * P ≤ 0.05

Enhanced FcγRIIa binding restores PMN-mediated cytotoxicity triggered by an FcγRIII-optimized anti-EGFR antibody

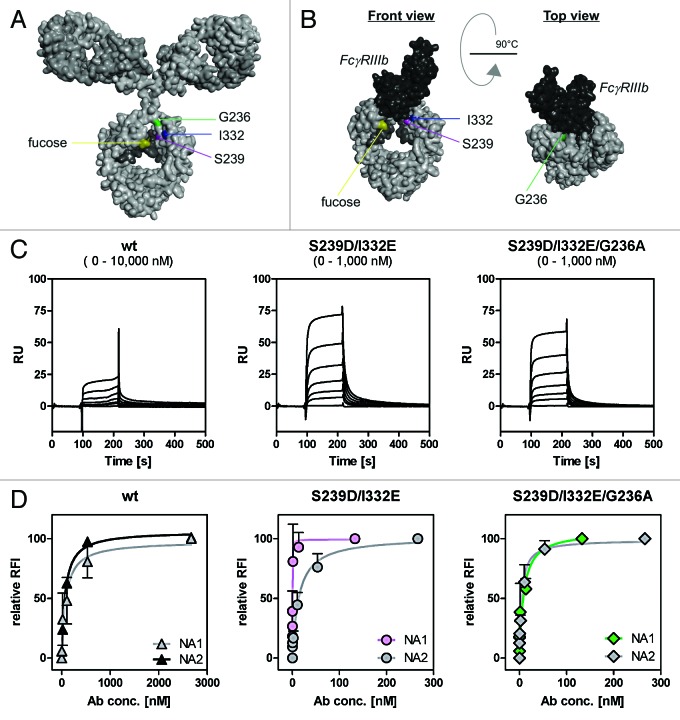

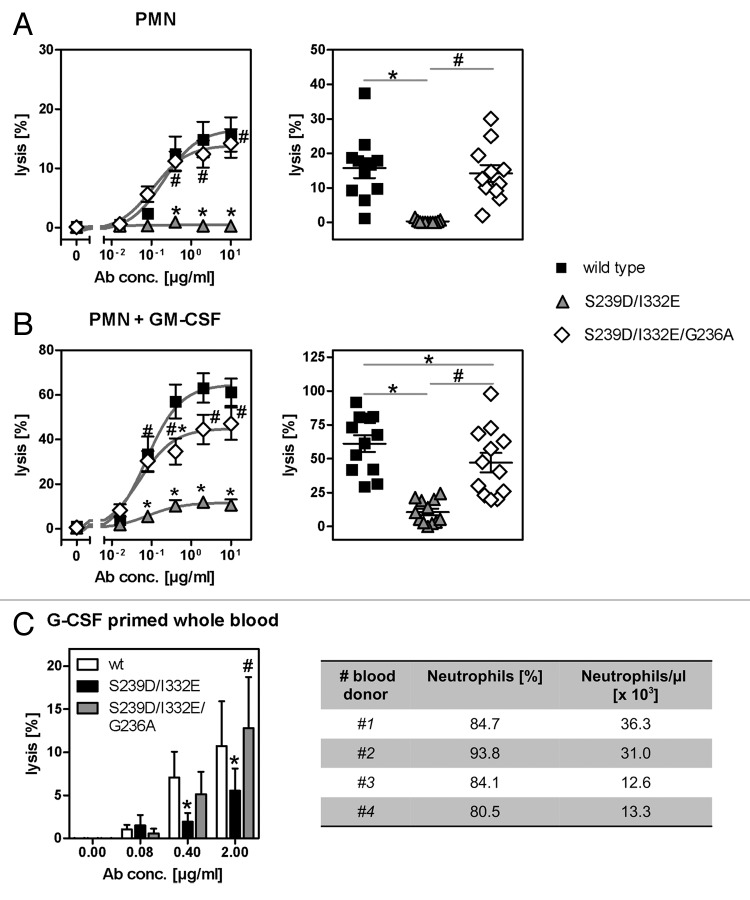

Since enhanced binding to FcγRIII impaired, while binding to FcγRIIa triggered PMN-mediated ADCC, FcγRIIa affinity of the FcγRIII-optimized variant was additionally enhanced (Table 1; Fig. 4A, B, C, and D) while retaining similar EGFR binding (Fig. S1). These anti-EGFR antibody variants were then analyzed regarding their affinities for FcγRIIIb and their capacity to trigger ADCC mediated by PMN (Fig. 4 and 5). As determined by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analyses utilizing recombinant human FcγRIIIb (Fig. 4C) and flow cytometry analyses with CHO-K1 cells stably transfected with FcγRIIIb-NA1 or FcγRIIIb-NA2 (Fig. 4D), the FcγRIIIa-optimized anti-EGFR antibody was revealed to also display enhanced FcγRIIIb binding affinities in comparison to wild type antibody (on average 25-fold enhanced FcγRIIIa binding, 19-fold enhanced FcγRIIIb binding, 7-fold enhanced FcγRIIa binding). Notably, the S239D/I332E variant displayed a higher affinity to FcγRIIIb-NA1 (KA = 8.53 nM−1) than to FcγRIIIb-NA2 (KA = 0.07nM−1), while no differences between both polymorphisms (KA-NA1 = 0.01 nM−1; KA-NA2 = 0.01 nM−1) were detected for the wild type antibody (Fig. 4D). As expected, the S239D/I332E variant almost completely lacked ADCC activity mediated by unstimulated (Fig. 5A) or GM-CSF stimulated PMN (Fig. 5B). However, insertion of the G236A mutation into the EGFR-Ab-S239D/I332E resulted in enhanced FcγRIIa binding (EGFR-Ab-S239D/I332E/G236A; compared with double mutant S239D/I332E 6-fold FcγRIIa binding, but no alterations in FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIIb binding, Table 1; KA-NA1 = 0.12nM−1; KA-NA2 = 0.22nM−1, Fig. 4D) and restored PMN-mediated ADCC to the level of the wild type anti-EGFR antibody in the case of unstimulated PMN (Fig. 5A) and to a slightly lower degree of the wild type anti-EGFR antibody in the case of GM-CSF stimulated PMN (Fig. 5B). Notably, results from SPR analyses should be considered in view of the fact that the antibodies’ affinities to FcγRs may be affected by the glycosylation patterns of the FcγRs.

Figure 4. Determination of binding capacities of distinct antibody variants to FcγRIIIb. (A) Structural model of human IgG1 (pdb file from Clark, MR, Chem Immunol 1997; 65:88–110). The presented model illustrates the position of analyzed amino acid substitutions, which are located in the CH2 domain, as well as the fucose residues in IgG1. (B) Crystal structure of FcγRIIIb in complex with an Fc fragment of IgG1 (pdb file IT89). Pictures in A and B were generated using Discovery Studio 3.5 Client software (Accelrys). (C) SPR analyses were performed to determine binding capacities of distinct analyzed antibody variants to FcγRIIIb. One out of three independent experiments is presented per antibody variant. (D) Dose-response curves were prepared for analyzed antibody variants at indicated concentrations using CHO cell lines, either stably transfected with plasmids encoding for FcγRIIIb-NA1 or FcγRIIIb-NA2. Means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments are presented.

Figure 5. Impairment of PMN-mediated ADCC activity by an FcγRIII-optimized anti-EGFR antibody variant is restored by additional improvement of its FcγRIIa affinity. (A, B) PMN from healthy blood donors were left untreated (A) or were stimulated with GM-CSF (B) and subsequently used as effector cells in ADCC experiments utilizing indicated antibodies at increasing concentrations and A431 cells (left panels). Results from different blood donors at highest antibody concentrations were separately depicted (right panels). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments with different blood donors. * P ≤ 0.05 for wild type antibody vs. antibody variants; # P ≤ 0.05 for S239D/I332E/G236A vs. S239D/I332E. (C) Neutrophil-enriched whole blood samples from G-CSF primed donors were used as effector source in ADCC experiments against A431 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments with different blood donors. * P ≤ 0.05 for wild type antibody vs. antibody variants; # P ≤ 0.05 for S239D/I332E/G236A vs. S239D/I332E.

Next, we aimed to assess the effect of FcγRIII- or FcγRIIa-optimization on ADCC activity in human whole blood that has been enriched for the myeloid compartment, especially with neutrophils, by G-CSF treatment of blood donors. As depicted in Figure 5C, G-CSF primed whole blood contained on average 23.3 x 103 neutrophils per µl. Thus, cytolysis of A431 cells in whole blood samples from G-CSF primed donors was analyzed in the presence or absence of wild type, S239D/I332E or S239D/I332E/G236A anti-EGFR antibody variants (Fig. 5C). While a significant decrease in cytotoxicity was observed for the S239D/I332E variant (5.5 ± 2.6%) compared with the wild type counterpart (10.7 ± 5.2%), the S239D/I332E/G236A (12.8 ± 6.0%) restored ADCC activity to the level of the wild type antibody. No cytotoxic activity was obtained by utilizing irrelevant control antibodies (data not shown). Together, these results demonstrate that the FcγRIII-optimized S239D/I332E anti-EGFR antibody variant lacked ADCC activity mediated by G-CSF primed neutrophils. Insertion of the G236A mutation into this antibody variant significantly restored cytotoxic activity albeit the FcγRI affinity of this S239D/I332E/G236 variant is half of that detected for the S239D/I332E variant (Table 1), leading to the conclusion that tumor cell destruction in whole blood was mostly promoted through FcγRIIa engagement.

Restoring of PMN-mediated ADCC by improved FcγRIIa binding is independent from FcγRIIIb and FcγRIIa polymorphisms

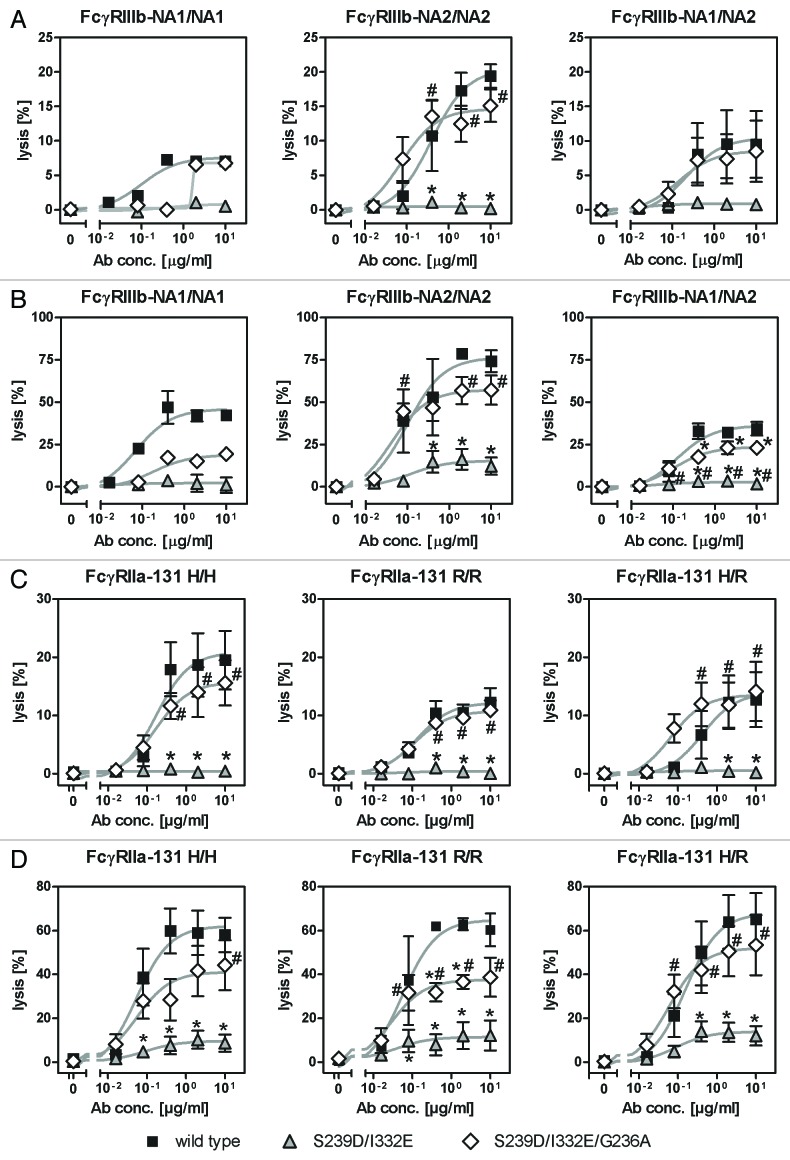

In the next set of experiments, we tested whether results received from PMN-mediated ADCC experiments utilizing anti-EGFR antibody variants S239D/I332E or S239D/I332E/G236A differed between blood donors harboring distinct FcγRIIIb (Fig. 6A and B) or FcγRIIa (Fig. 6C and D) polymorphisms. In the case of unstimulated PMN, the lowest PMN-ADCC activity by wild type antibody was detected for a homozygous FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA1 blood donor (7.0 ± 0.7%), followed by heterozygous FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2 blood donors (9.5 ± 4.9%), while highest ADCC was reached with homozygous FcγRIIIb-NA2/NA2 blood donors (19.4 ± 1.7%; Fig. 6A). However, PMN-ADCC activity was completely abrogated for all three blood donor groups using the S239D/I332E antibody variant and restored to the level of the wild type antibody by the S239D/I332E/G236A variant (FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA1 6.8 ± 0.6%, FcγRIIIb-NA2/NA2 15.1 ± 2.4%, FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2 8.5 ± 4.5%). Similar results were received from experiments with GM-CSF stimulated PMN, although higher levels of PMN-mediated ADCC were detected for wild type (FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA1 42.3 ± 1.5%, FcγRIIIb-NA2/NA2 74.2 ± 6.4%, FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2 34.4 ± 4.0%) and S239D/I332E/G236A (FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA1 19.3 ± 1.9%, FcγRIIIb-NA2/NA2 57.1 ± 8.6%, FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2 23.0 ± 1.7%) anti-EGFR antibody variants compared with unstimulated PMN (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Enhancement of PMN-mediated ADCC by increased FcγRIIa binding is not limited to specific FcγRIIIb or FcγRIIa polymorphisms. (A-D) The effect of distinct FcγRIIIb (FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2; A, B) and FcγRIIa (FcγRIIa-131H/R; C, D) polymorphisms on the extent of PMN-mediated ADCC against A431 cells by Fc-engineered anti-EGFR antibody variants was analyzed by 51chromium release experiments utilizing either untreated PMN (A, C) or GM-CSF stimulated PMN (B, C) from healthy blood donors. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments with different blood donors, except for FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA1 (n = 1). * P ≤ 0.05 for wild type antibody vs. antibody variants; # P ≤ 0.05 for S239D/I332E/G236A vs. S239D/I332E.

Impairment of PMN-mediated ADCC against A431 cells by FcγRIII-optimized anti-EGFR antibody variant S239D/I332E was shown to be independent of the FcγRIIa-131H/R polymorphisms as demonstrated for FcγRIIa-131H/H, FcγRIIa-131H/R and FcγRIIa-131R/R blood donors (Fig. 6C+D). However, while the additional insertion of the G236A mutation into the S239D/I332E variant (FcγRIIa-131H/H 15.6 ± 3.9%, FcγRIIa-131R/R 10.9 ± 1.7%, FcγRIIa-131H/R 14.1 ± 5.1%) completely restored ADCC mediated by unstimulated PMN to the level of the wild type variant (FcγRIIa-131H/H 19.5 ± 5.0%, FcγRIIa-131R/R 12.3 ± 2.5%, FcγRIIa-131H/R 12.8 ± 4.7%; Fig. 6C), it in fact significantly promoted ADCC mediated by GM-CSF stimulated PMN, but to a lower extent (FcγRIIa-131H/H 44.2 ± 11.4%, FcγRIIa-131R/R 38.7 ± 8.9%, FcγRIIa-131H/R 53.3 ± 13.7%) compared with the wild type antibody (FcγRIIa-131H/H 58.0 ± 7.9%, FcγRIIa-131R/R 60.3 ± 7.5%, FcγRIIa-131H/R 65.2 ± 11.9%).

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that enhancing the affinity for FcγRIII by glyco- or protein-engineering abolished the contribution of neutrophils as effector cells in ADCC. Thus, removal of fucose or protein-engineering with the intention to optimize NK cell-mediated ADCC by high affinity FcγRIIIa binding resulted in a complete loss of PMN-mediated ADCC activity. This dramatic effect was mediated by FcγRIIIb on PMN, which acts as a decoy receptor in ADCC by FcγRIII-optimized antibodies. Notably, previous studies demonstrated enhanced PMN-mediated phagocytosis triggered by FcγRIII-optimized CD20-directed antibody variants.36,37 Hence, it might be hypothesized that impaired PMN-mediated ADCC might be balanced by improved PMN-mediated phagocytosis in the case of FcγRIII-optimized CD20 antibodies. However, in the case of FcγRIII-optimized anti-EGFR antibody variants, phagocytosis may be limited by the size of EGFR-expressing tumor cells (e.g., A431 cells are 15.5 µm in diameter) in relation to neutrophils’ cell size (9–12 µm in diameter). Our results furthermore demonstrate that PMN recruitment for ADCC can be restored by enhancing the affinity to the activatory FcγRIIa receptor, suggesting that the FcγRIIa/FcγRIII binding ratio of therapeutic antibodies should be considered in the development of next-generation antibodies.

Furthermore, we analyzed the effect of distinct FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2 and FcγRIIa-131 R/H polymorphisms on PMN-mediated ADCC triggered by FcγRIII- as well as FcγRIII and FcγRIIa-optimized anti-EGFR antibody variants. Notably, in all cases the FcγRIII-optimized antibody lacked while additional FcγRIIa-optimization restored PMN-ADCC, suggesting, independently from FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2 and FcγRIIa-131 R/H polymorphisms, an improved cytotoxic potential of Fc-engineered antibodies by further enhancement of their affinity to FcγRIIa. However, one cannot exclude a pivotal role of the interplay between gene copy number variations of FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2 and neutrophil-mediated cytotoxicity triggered by Fc-optimized antibody.38,39

FcγRIIIb on human PMN has been described to trigger degranulation,40 actin polymerization and priming of phagocytosis via FcγRIIa,41 as well as binding and phagocytosis of soluble immune complexes.42,43 However, conflicting results have been reported in the literature with regard to ADCC induction by FcγRIIIb. Some of these inconclusive data are explained by the use of whole FcγRIII-targeted antibodies instead of F(ab)2 fragments to block Fcγ receptor functions. These whole antibodies bind to FcγRIII via their Fab regions and can block FcγRIIa via their Fc portion.44 Our studies with a non-FcR binding variant of an FcγRIII-directed antibody (Fig. 3A), which selectively blocks FcγRIII by interfering with its Ig binding region, support these conclusions. Thus, our present results are in agreement with previous data that human PMN mediate efficient ADCC against tumor cells via FcγRIIa, but not via the most abundantly expressed FcγRIIIb.45 These observations are extended by our findings that the FcγRIIa/FcγRIIIb affinity ratio of IgG1 molecules correlates with PMN-mediated ADCC, with high ratios triggering effective tumor cell killing, while lower ratios mediate low levels of cytotoxicity.

PMN-expressed FcγRIIa (CD32a) is an ITAM-containing transmembrane molecule, which, like FcγRIIIb, does not have a murine homolog. These differences between mouse and man hamper studies to assess the functional roles of individual FcγR on PMN in vivo. To address this issue, human FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb transgenic mice were generated in an FcRγ-chain deficient background. PMN of these mice exclusively expressed the human FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb receptors and were investigated in antibody-mediated inflammatory diseases. FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb were demonstrated to be involved in PMN recruitment to inflammatory sites, while antibody-mediated tissue destruction was solely dependent on FcγRIIa.46 These in vivo studies may point to a prominent role of FcγRIIa, but not of FcγRIIIb, in antibody-mediated cytotoxicity in the course of inflammation, although, to our knowledge, these gene-modified mice have not been investigated in tumor models.

Based on these findings, it might be hypothesized that FcγRIII-optimized antibodies are also able to activate immune effector functions of PMN with the exception of ADCC. In macrophages, which express FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIa but no FcγRIIIb, FcγRIII-optimized protein-engineered antibodies have been linked to enhanced ADCC against tumor cells, while FcγRIIa-optimized molecules displayed strongest phagocytic activities.47 In contrast, a non-fucosylated CD20-directed antibody with higher FcγRIII binding affinity has been suggested to increase neutrophil mediated phagocytosis of B cell lymphomas,36,37 while no differences could be observed regarding macrophage mediated phagocytosis.48

On the basis of promising preclinical data,49 Fc-engineered antibodies were moved into clinical studies for oncological indications.50 By the end of 2012, 16 Fc-engineered antibodies were evaluated clinically,51 with glyco-engineered antibodies being more advanced than protein-engineered derivatives. A glyco-engineered EGFR-targeting antibody (GA201) was recently tested in patients with advanced solid tumors, including colorectal cancer, in a Phase 1 clinical study,52 but further clinical evaluation of GA201 was stopped in July 2013. Furthermore, the first glyco-engineered antibody against CCR4 (mogamulizumab) was approved in Japan in 2012 for the treatment of adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma,53 while a hypo-fucosylated antibody against CD20 (obinutuzumab) received breakthrough therapy designation and was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in November 2013 for the treatment of CLL patients.54 However, results from meaningful comparisons between modified and unmodified control antibodies are not currently available, and are not expected to be generated in the near future.55 Thus, the clinical potential of Fc-engineered antibodies is difficult to assess.

To conclude, the present study represents novel findings concerning recruitment of PMN for tumor cell destruction by Fc-engineered antibodies. While PMN-mediated ADCC was completely abolished by FcγRIII-optimized antibodies through FcγRIIIb binding, it was potently enhanced by optimization of FcγRIIa binding affinity. Importantly, functional analyses unraveled the ratio between FcγRIIa and FcγRIII binding affinities to determine PMN-mediated ADCC activity, and has therefore revealed new possibilities for the engineering of therapeutic antibodies.

Material and Methods

Study population

Experiments reported here were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Christian-Albrechts-University and the University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel, Germany, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood donors were randomly selected from healthy volunteers, who gave written informed consent before analyses. For comparison, PMN from healthy hematopoietic stem cell donors after mobilization with G-CSF, from paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and from eosinophilia donors were analyzed. FcγRIIa-131R/H, FcγRIIIa-158F/V or FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2 genotypes were analyzed by Taqman SNP genotyping assays (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturers’ instructions.

Cell lines and transfectants

EGFR-overexpressing epidermoid carcinoma cell line A431 (ATCC) was kept in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (both PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria). CHO-K1 cells (Lonza), stably transfected with expression constructs coding either for the human FcγRIIIb-NA1 or FcγRIIIb-NA2 cDNAs, were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 500 μg/ml geneticin (Invitrogen) to ensure stable surface expression of FcγRIIIb-NA1/NA2.

Antibodies

A humanized variant of the approved EGFR-targeting antibody cetuximab (chimeric IgG1; Erbitux®, Merck), lacking the glycosylation motif in the VH domain originally detected in cetuximab, was generated (patent US 2005/0142133), and produced in HEK293E cells (wild type).56 Protein- or glyco-engineered antibody variants of this wild type antibody were constructed, expressed and purified as described,17,47 except that expression was performed in HEK293E cells (wild type, S239D/I332E and S239D/I332E/G236A variants) or CHO-Lec13 cells (afucosylated variant) using the pTT5 vector system (NRC-BRI).17 A human irrelevant IgG1 antibody served as control antibody.

In ADCC experiments, a mouse/human chimeric anti-CD16 IgG1 antibody (1 μg/ml) whose Fc part has been knocked-out for Fc receptor binding (CD16-IgG1-Ko)57 and an anti-CD32-(Fab’)2 fragment (1 µg/ml; AT10, kindly provided by Martin Glennie, Tenovus Research Laboratory) were used to elucidate the role of FcγRIII or FcγRII binding in MNC- and PMN-mediated ADCC against tumor cells. An irrelevant ctrl.-IgG1-Ko (1 μg/ml) and an irrelevant ctrl.-(Fab’)2 fragment were used as control molecules.

Surface plasmon resonance analysis

The antibodies’ affinities to FcγRs (FcγRI and FcγRIIb, produced in NS0 cells; R&D Systems Inc; FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIa, constructed as C-terminal 6xHis-GST fusions, expressed in HEK293T cells17) were measured by SPR analyses as previously described by Richards et al.47

For FcγRIIIb binding analyses, SPR measurements were performed on a BIAcore 1000 SPR biosensor (GE Healthcare) using a CM5 sensor chip. Recombinant FcγRIIIb-NA2 protein (#1597-FC-050/CF; R&D Systems Inc) was immobilized on the CM5 sensor chip at 1,000 response units (RU). 2-fold serial dilutions were prepared for all antibody variants and injected onto the sensor chip (contact time 120 s; dissociation time 900 s) at a flow rate of 30 µl/min. Due to distinct antibodies’ binding capacities to FcγRIIIb, concentration ranges for analyzed antibody variants were as follows: wt (0–10,000 nM); S239D/I332E and S239D/I332E/G236A (0–1,000 nM). After each cycle, the surface of the sensor chip was regenerated with glycine buffer (contact time 60 s; flow rate 10µl/min). Binding capacities were recorded as response units (RU). KD values were calculated from the kinetic constants (kon and koff) from three independent experiments and KA values were calculated as reciprocal values of KD.

Isolation of human effector cells

MNC or PMN were isolated from freshly drawn peripheral blood as described previously.22 Eosinophils were isolated from the PMN fraction using the human Eosinophil Isolation Kit from Miltenyi Biotec Inc according to the manufacturers’ instructions (Miltenyi Biotec Inc).

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity assays

ADCC assays were performed as described previously22 at an effector to target (E:T) ratio of 80:1. PMN and eosinophils were utilized as effector cells in the presence of 50 U/ml human GM-CSF. Whole blood assays were performed in the presence of 12.5 µg/ml lepirudin (Refludan®, Pharmion). Percentage of cellular cytotoxicity was calculated using the formula “% specific lysis = (exp. cpm - basal cpm) / (maximal cpm - basal cpm) × 100.”

Immunofluorescence analyses

For indirect immunofluorescence, cells were incubated with EGFR-targeted antibodies at various concentrations in PBS supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% sodium-azide (PBS buffer) for 30 min on ice. After washing, cells were stained with FITC-conjugated F(ab)2 fragments rabbit anti-human IgG (Dako Denmark), respectively.

FcR expression on effector cells was determined by direct immunofluorescence. Cells were incubated with fluorochrome-labeled FcR-directed antibodies (CD16-PC5, CD32-PE, CD89-PE; all from Beckman Coulter) or respective control antibodies at saturating concentrations in the presence of human IgG (Intratect, Biotest) to prevent Fc-mediated binding to Fc receptors.

Immunofluorescence was analyzed on a flow cytometer (Epics Profile; Beckman Coulter).

Data processing and statistical analyses

Data are displayed graphically and were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. Curves were fitted using a nonlinear regression model with a sigmoidal dose response. Statistical significance was determined by the one-way or two-way Anova repeated measures tests, respectively, with Bonferroni’s post-test. The respective results were displayed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). P values were calculated and null hypotheses were rejected when P ≤ 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Muchhal U and Desjarlais JR are employed by Xencor Inc. Derer S, Glorius P, Schlaeth M, Lohse S, Klausz K, Humpe A, Valerius T, and Peipp M all declare no potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistance from Christyn Wildgrube and Yasmin Brodtman, as well as funding from the German Research Foundation (DE 1874/1–1; VA 124/7–2; LO 1853/1–1).

Authorship Contributions

Peipp M, Valerius T, and Derer S designed the study. Humpe A and Lohse S were involved in the recruitment and collection of samples. Derer S, Glorius P, Schlaeth M, and Muchhal U performed all laboratory work. Derer S and Muchhal U performed data analyses. Interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript were done by Derer S, Valerius T, and Peipp M. Desjarlais JR, Humpe A, Klausz K, and Lohse S proofread the manuscript prior to submission.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/mabs/article/27457

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/mabs/article/27457

References

- 1.Weiner LM, Dhodapkar MV, Ferrone S. Monoclonal antibodies for cancer immunotherapy. Lancet. 2009;373:1033–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. The world health report - Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Scott AM, Wolchok JD, Old LJ. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:278–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000;6:443–6. doi: 10.1038/74704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Haij S, Jansen JH, Boross P, Beurskens FJ, Bakema JE, Bos DL, Martens A, Verbeek JS, Parren PW, van de Winkel JG, et al. In vivo cytotoxicity of type I CD20 antibodies critically depends on Fc receptor ITAM signaling. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3209–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uchida J, Hamaguchi Y, Oliver JA, Ravetch JV, Poe JC, Haas KM, Tedder TF. The innate mononuclear phagocyte network depletes B lymphocytes through Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms during anti-CD20 antibody immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1659–69. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent immunoglobulin g subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science. 2005;310:1510–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1118948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valerius T. Fcgamma receptor polymorphisms as biomarkers for epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e393–, author reply e394-6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.7342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cartron G, Dacheux L, Salles G, Solal-Celigny P, Bardos P, Colombat P, Watier H. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcgammaRIIIa gene. Blood. 2002;99:754–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musolino A, Naldi N, Bortesi B, Pezzuolo D, Capelletti M, Missale G, Laccabue D, Zerbini A, Camisa R, Bisagni G, et al. Immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with HER-2/neu-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1789–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farag SS, Flinn IW, Modali R, Lehman TA, Young D, Byrd JC. Fc gamma RIIIa and Fc gamma RIIa polymorphisms do not predict response to rituximab in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:1472–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peipp M, Dechant M, Valerius T. Effector mechanisms of therapeutic antibodies against ErbB receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:436–43. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Gordon M, Schultheis AM, Yang DY, Nagashima F, Azuma M, Chang HM, Borucka E, Lurje G, Sherrod AE, et al. FCGR2A and FCGR3A polymorphisms associated with clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor expressing metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with single-agent cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3712–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bibeau F, Lopez-Crapez E, Di Fiore F, Thezenas S, Ychou M, Blanchard F, Lamy A, Penault-Llorca F, Frébourg T, Michel P, et al. Impact of FcγRIIa-FcγRIIIa polymorphisms and KRAS mutations on the clinical outcome of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab plus irinotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1122–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter PJ. Potent antibody therapeutics by design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:343–57. doi: 10.1038/nri1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idusogie EE, Wong PY, Presta LG, Gazzano-Santoro H, Totpal K, Ultsch M, Mulkerrin MG. Engineered antibodies with increased activity to recruit complement. J Immunol. 2001;166:2571–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazar GA, Dang W, Karki S, Vafa O, Peng JS, Hyun L, Chan C, Chung HS, Eivazi A, Yoder SC, et al. Engineered antibody Fc variants with enhanced effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4005–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508123103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrara C, Grau S, Jäger C, Sondermann P, Brünker P, Waldhauer I, Hennig M, Ruf A, Rufer AC, Stihle M, et al. Unique carbohydrate-carbohydrate interactions are required for high affinity binding between FcgammaRIII and antibodies lacking core fucose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108455108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K, Meng YG, Rae J, Briggs J, Xie D, Lai J, Stadlen A, Li B, et al. High resolution mapping of the binding site on human IgG1 for Fc gamma RI, Fc gamma RII, Fc gamma RIII, and FcRn and design of IgG1 variants with improved binding to the Fc gamma R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6591–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shields RL, Lai J, Keck R, O’Connell LY, Hong K, Meng YG, Weikert SH, Presta LG. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26733–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jefferis R, Lund J, Goodall M. Recognition sites on human IgG for Fc gamma receptors: the role of glycosylation. Immunol Lett. 1995;44:111–7. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peipp M, Lammerts van Bueren JJ, Schneider-Merck T, Bleeker WW, Dechant M, Beyer T, Repp R, van Berkel PH, Vink T, van de Winkel JG, et al. Antibody fucosylation differentially impacts cytotoxicity mediated by NK and PMN effector cells. Blood. 2008;112:2390–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Egmond M, Bakema JE. Neutrophils as effector cells for antibody-based immunotherapy of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23:190–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desjarlais JR, Lazar GA, Zhukovsky EA, Chu SY. Optimizing engagement of the immune system by anti-tumor antibodies: an engineer’s perspective. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:898–910. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heijnen IA, Rijks LJ, Schiel A, Stockmeyer B, van Ojik HH, Dechant M, Valerius T, Keler T, Tutt AL, Glennie MJ, et al. Generation of HER-2/neu-specific cytotoxic neutrophils in vivo: efficient arming of neutrophils by combined administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and Fcgamma receptor I bispecific antibodies. J Immunol. 1997;159:5629–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider-Merck T, Lammerts van Bueren JJ, Berger S, Rossen K, van Berkel PH, Derer S, Beyer T, Lohse S, Bleeker WK, Peipp M, et al. Human IgG2 antibodies against epidermal growth factor receptor effectively trigger antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity but, in contrast to IgG1, only by cells of myeloid lineage. J Immunol. 2010;184:512–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biburger M, Aschermann S, Schwab I, Lux A, Albert H, Danzer H, Woigk M, Dudziak D, Nimmerjahn F. Monocyte subsets responsible for immunoglobulin G-dependent effector functions in vivo. Immunity. 2011;35:932–44. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito A, Ishida T, Utsunomiya A, Sato F, Mori F, Yano H, Inagaki A, Suzuki S, Takino H, Ri M, et al. Defucosylated anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody exerts potent ADCC against primary ATLL cells mediated by autologous human immune cells in NOD/Shi-scid, IL-2R gamma(null) mice in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;183:4782–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siders WM, Shields J, Garron C, Hu Y, Boutin P, Shankara S, Weber W, Roberts B, Kaplan JM. Involvement of neutrophils and natural killer cells in the anti-tumor activity of alemtuzumab in xenograft tumor models. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1293–304. doi: 10.3109/10428191003777963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albanesi M, Mancardi DA, Jönsson F, Iannascoli B, Fiette L, Di Santo JP, Lowell CA, Bruhns P. Neutrophils mediate antibody-induced antitumor effects in mice. Blood. 2013;122:3160–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-497446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colombo MP, Ferrari G, Stoppacciaro A, Parenza M, Rodolfo M, Mavilio F, Parmiani G. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor gene transfer suppresses tumorigenicity of a murine adenocarcinoma in vivo. J Exp Med. 1991;173:889–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bologna L, Gotti E, Da Roit F, Intermesoli T, Rambaldi A, Introna M, Golay J. Ofatumumab is more efficient than rituximab in lysing B chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells in whole blood and in combination with chemotherapy. J Immunol. 2013;190:231–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Unkeless JC, Scigliano E, Freedman VH. Structure and function of human and murine receptors for IgG. Annu Rev Immunol. 1988;6:251–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.06.040188.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruhns P. Properties of mouse and human IgG receptors and their contribution to disease models. Blood. 2012;119:5640–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-380121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibata-Koyama M, Iida S, Misaka H, Mori K, Yano K, Shitara K, Satoh M. Nonfucosylated rituximab potentiates human neutrophil phagocytosis through its high binding for FcgammaRIIIb and MHC class II expression on the phagocytotic neutrophils. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:309–21. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golay J, Da Roit F, Bologna L, Ferrara C, Leusen JH, Rambaldi A, Klein C, Introna M. Glycoengineered CD20 antibody obinutuzumab activates neutrophils and mediates phagocytosis through CD16B more efficiently than rituximab. Blood. 2013;122:3482–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-504043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breunis WB, van Mirre E, Geissler J, Laddach N, Wolbink G, van der Schoot E, de Haas M, de Boer M, Roos D, Kuijpers TW. Copy number variation at the FCGR locus includes FCGR3A, FCGR2C and FCGR3B but not FCGR2A and FCGR2B. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E640–50. doi: 10.1002/humu.20997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willcocks LC, Lyons PA, Clatworthy MR, Robinson JI, Yang W, Newland SA, Plagnol V, McGovern NN, Condliffe AM, Chilvers ER, et al. Copy number of FCGR3B, which is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, correlates with protein expression and immune complex uptake. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1573–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huizinga TW, Dolman KM, van der Linden NJ, Kleijer M, Nuijens JH, von dem Borne AE, Roos D. Phosphatidylinositol-linked FcRIII mediates exocytosis of neutrophil granule proteins, but does not mediate initiation of the respiratory burst. J Immunol. 1990;144:1432–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salmon JE, Brogle NL, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP. Fc gamma receptor III induces actin polymerization in human neutrophils and primes phagocytosis mediated by Fc gamma receptor II. J Immunol. 1991;146:997–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen K, Nishi H, Travers R, Tsuboi N, Martinod K, Wagner DD, Stan R, Croce K, Mayadas TN. Endocytosis of soluble immune complexes leads to their clearance by FcγRIIIB but induces neutrophil extracellular traps via FcγRIIA in vivo. Blood. 2012;120:4421–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-401133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lux A, Yu X, Scanlan CN, Nimmerjahn F. Impact of immune complex size and glycosylation on IgG binding to human FcγRs. J Immunol. 2013;190:4315–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurlander RJ. Blockade of Fc receptor-mediated binding to U-937 cells by murine monoclonal antibodies directed against a variety of surface antigens. J Immunol. 1983;131:140–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fanger MW, Shen L, Graziano RF, Guyre PM. Cytotoxicity mediated by human Fc receptors for IgG. Immunol Today. 1989;10:92–9. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(89)90234-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuboi N, Asano K, Lauterbach M, Mayadas TN. Human neutrophil Fcgamma receptors initiate and play specialized nonredundant roles in antibody-mediated inflammatory diseases. Immunity. 2008;28:833–46. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richards JO, Karki S, Lazar GA, Chen H, Dang W, Desjarlais JR. Optimization of antibody binding to FcgammaRIIa enhances macrophage phagocytosis of tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2517–27. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bologna L, Gotti E, Manganini M, Rambaldi A, Intermesoli T, Introna M, Golay J. Mechanism of action of type II, glycoengineered, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody GA101 in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia whole blood assays in comparison with rituximab and alemtuzumab. J Immunol. 2011;186:3762–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peipp M, van de Winkel JG, Valerius T. Molecular engineering to improve antibodies’ anti-lymphoma activity. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2011;24:217–29. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reichert JM, Dhimolea E. The future of antibodies as cancer drugs. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17:954–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beck A, Reichert JM. Marketing approval of mogamulizumab: a triumph for glyco-engineering. MAbs. 2012;4:419–25. doi: 10.4161/mabs.20996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paz-Ares LG, Gomez-Roca C, Delord JP, Cervantes A, Markman B, Corral J, Soria JC, Bergé Y, Roda D, Russell-Yarde F, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic dose-escalation study of RG7160 (GA201), the first glycoengineered monoclonal antibody against the epidermal growth factor receptor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3783–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beck A, Reichert JM. Marketing approval of mogamulizumab: a triumph for glyco-engineering. MAbs. 2012;4:419–25. doi: 10.4161/mabs.20996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salles G, Morschhauser F, Lamy T, Milpied N, Thieblemont C, Tilly H, Bieska G, Asikanius E, Carlile D, Birkett J, et al. Phase 1 study results of the type II glycoengineered humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody obinutuzumab (GA101) in B-cell lymphoma patients. Blood. 2012;119:5126–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-404368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Oers MHJ. CD20 antibodies: type II to tango? Blood. 2012;119:5061–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-420711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lazar GA, Desjarlais JR, Jacinto J, Karki S, Hammond PW. A molecular immunology approach to antibody humanization and functional optimization. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:1986–98. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Repp R, Kellner C, Muskulus A, Staudinger M, Nodehi SM, Glorius P, Akramiene D, Dechant M, Fey GH, van Berkel PH, et al. Combined Fc-protein- and Fc-glyco-engineering of scFv-Fc fusion proteins synergistically enhances CD16a binding but does not further enhance NK-cell mediated ADCC. J Immunol Methods. 2011;373:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.