Abstract

In July 2005, New Mexico initiated a major reform of publicly-funded behavioral healthcare to reduce cost and bureaucracy. We used a mixed-method approach to examine how this reform impacted the workplaces and employees of service agencies that care for low-income adults in rural and urban areas. Information technology problems and cumbersome processes to enroll patients, procure authorizations, and submit claims led to payment delays that affected the financial status of the agencies, their ability to deliver care, and employee morale. Rural employees experienced lower levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment and higher levels of turnover intentions under the reform when compared to their urban counterparts.

Keywords: Health policy, Mental illness, Organizational climate, Rural, System transformation

Introduction

In 2003, the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health published a wide-ranging study of behavioral health-care in the U.S. (2003). This same year, Governor Bill Richardson announced a major overhaul of publicly-funded behavioral healthcare within the rural state of New Mexico (NM). Inspired by the Commission’s ambitious vision for a “transformed system” (Hyde 2004) and influential documents issued by the U.S. Surgeon General (2001a, b) and the American College of Mental Health Administration (2003), state officials sought to consolidate service funds from 15 state agencies in order to manage and leverage them in innovative ways within a single service delivery system. Such consolidation would ideally contribute to unified administrative practices and reduced paperwork for service providers (Hyde 2004). To facilitate the integration of behavioral health services, the state pursued a public–private partnership with a for-profit managed care company. After a competitive bidding process ending in March 2005, Value Options New Mexico (VONM), was selected to create the infrastructure for a “seamless” system of care to maximize the state’s limited funding for public services (Hyde 2004). The official transition to the new system of administering and delivering behavioral healthcare occurred simultaneously in rural and urban areas of NM in July 2005 (New Mexico Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative 2005).

In this mixed-method investigation, we examine how this unprecedented system-change effort in NM affected safety-net institutions (SNIs) and personnel involved in caring for low-income populations, including those on Medicaid, the uninsured, and/or people at serious risk for behavioral health problems (Lewin and Altman 2000; Waitzkin et al. 2002, 2008). These SNIs generally provide services at no cost or might charge according to a sliding scale based on income; such institutions rely heavily on public funding to care for the poor. Although most SNIs, such as community mental health centers, accept patients with private insurance, such persons usually compose a minority of the clientele (Cunningham et al. 2006; Ormond et al. 2000).

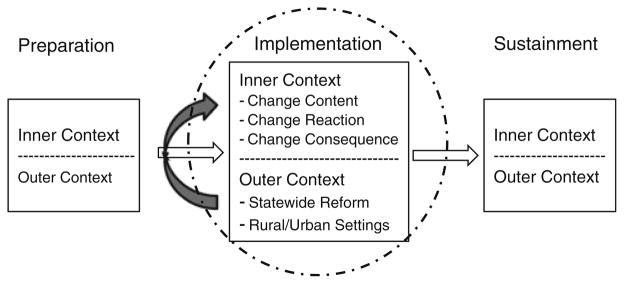

We adapted the comprehensive Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) conceptual model to study the NM reform, and to frame our research questions concerning organizational and personnel outcomes related to this initiative (Fig. 1). The EPIS model explicitly delineates four different phases (EPIS) of successful change and highlights how outer contexts and inner contexts influence and are influenced by such change efforts (Aarons et al. 2011a). The outer context includes state and federal sociopolitical, funding, and regulatory mechanisms, as well as variations in service delivery environments relevant to the change effort. The inner context encompasses organizations and individuals that affect and are affected by this effort. From the perspective of SNI personnel, the state-mandated reform represented an outer context shift that would likely require substantial internal adjustments. Additionally, the change initiative only allowed a limited preparation phase without an exploration phase for SNIs to identify and seek optimal solutions to the potential problems that might arise during the change effort. Our study focuses on the inner context of the active implementation phase (as indicated by the dashed line in Fig. 1) to illuminate the issues SNI administrators, providers, and support staff encountered as they responded to the outer contextual influences of the NM reform.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of organizational change phases

While all SNIs had to respond to changes under the statewide managed care reform, one important outer contextual concern that differed among SNIs was the rural versus urban nature of their service delivery environment. Previous studies demonstrate a disproportionate impact of managed care reforms on SNIs in rural communities (Felt-Lisk et al. 1999; Lambert et al. 2003). In such settings, access to specialty behavioral healthcare is scarce (Smalley and Warren 2012; Deleon et al. 2012) and there is greater reliance on paraprofessionals and mid-level providers whom managed care companies may not credential and/or reimburse for services (Bird et al. 2001; Waitzkin et al. 2002; Hauenstein et al. 2007). The small number of provider agencies also creates a delicate service delivery infrastructure that is sensitive to outer contextual influences, most especially changes in financing and administration. For example, employees of understaffed SNIs may find that they must comply with largely uncompensated administrative requirements from the corporate partner to determine eligibility, enroll clients into programs, authorize and monitor service delivery, and bill for reimbursement (Smith and Lipsky 1993). They may also need to adapt to the new information technologies (IT) that are likely to be introduced during the redesign of a behavioral healthcare delivery system (Institute of Medicine 2005). Cost containment strategies favored under managed care combined with increased administrative workload and insufficient infrastructure creates unique pressures for SNIs in rural areas (Cunningham et al. 2006; Gale et al. 2010; Lambert et al. 2003).

This study assesses two overall research questions: (1) how has implementation of the NM reform impacted SNI workplaces and personnel; and (2) have rural SNIs and their personnel experienced the reform differently from urban SNI personnel? We utilized a model of staff reactions to organizational change (Oreg et al. 2011) to guide our assessment. This model derives from an extensive review of the organizational change literature and indicates that a range of change antecedents (e.g., change content and change recipient characteristics) influence the explicit reactions of staff to the change (e.g., affective, cognitive, and/or behavioral reactions), which then contribute to work-related and personal change consequences (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions). We incorporated this model into our assessment by focusing on the following inner context aspects of the active implementation phase: (1) the key changes associated with the NM reform (change content) identified by SNI employees; (2) the explicit reactions of employees to these changes; and (3) the consequences of these changes for both the employees and the SNIs (see Fig. 1).

We draw on qualitative and quantitative data collected from SNIs over a 4-year period to answer our two primary research questions. To our knowledge, this is the first long-term study of behavioral health reform that combines both types of data to assess the inner context of a state-mandated, large-scale, system-change initiative.

Earlier Reform in New Mexico

The rationale for assessing how system change originating within the outer context influences the attitudes and experiences of actors within the inner context derives from previous ethnographic studies of governmental reform in the health and mental health arenas (Shaw 2012), including anthropologically-informed research centered specifically on system-change interventions involving managed care (Donald 2001; Lamphere 2005; Mulligan 2010; Rylko-Bauer and Farmer 2002). Such studies underscore the need to examine the dynamics of how such reforms impinge on the work environments of staff and providers—persons at the frontlines of service provision—and shape how these individuals think about and perform their jobs.

An examination of NM’s first foray into managed care for behavioral health services adds to this rationale. In 1997, the state instituted a mandatory Medicaid managed care (MMC) program. For this first reform, the state contracted with multiple managed care organizations to contain costs and oversee services for low-income individuals with behavioral health needs who were eligible for Medicaid. As documented through extensive ethnographic research (Waitzkin et al. 2002; Lamphere 2005; Willging et al. 2005), the transition to the new MMC system led to problems for SNIs specializing in mental healthcare. Employees of SNIs commonly characterized the transition as chaotic and stressful, and SNIs experienced difficulties in maintaining programs and services. Medicaid managed care recipients also received lower levels of care than their mental health conditions warranted (Legislative Finance Committee 2000a) and financial resources were diverted to administration, as only 55 % of MMC funds earmarked for mental health services in 1999 were distributed to providers (Legislative Finance Committee 2000b). The pervasiveness and severity of the problems prompted federal government intervention in 2000 (Willging et al. 2003).

The move to MMC in 1997 compromised an under-funded mental health system in NM (Waitzkin et al. 2002; Willging et al. 2005). The reform of 2005 extended managed care to all behavioral health services paid for with state monies. In contrast to the preceding reform, a single managed care contractor was entrusted to administer these monies in an effort to decrease service fragmentation and administrative burden for both the state government and providers. No new funding was added to finance behavioral healthcare under this “cost-neutral” reform (Hyde 2004). In spite of the negative experience with MMC, SNI personnel were guardedly optimistic that the state’s interest in reducing and streamlining administrative procedures under the latest reform might lead to better working conditions and long-term improvements in a beleaguered system (Willging et al. 2009).

Methods

As part of a larger mixed-method study of the latest behavioral health reform in NM (Aarons et al. 2011b; Semansky et al. 2009, 2012; Willging et al. 2009), we employed a qualitative research design supplemented with quantitative measures and analyses to identify and contextualize factors bearing on the work environments of SNIs serving low-income adults with serious mental illness, i.e., schizophrenia, major depression, and bi-polar disorder. We took advantage of the strengths of qualitative and quantitative research, with the goal of determining the extent to which results of the two methodological approaches converged. This assessment adhered to the mixed-method analytical conventions of Palinkas et al. (2011). Its basic structure can be characterized as “concurrent QUAL + quant” in that qualitative and quantitative data were collected and analyzed simultaneously, with the qualitative approach providing the dominant frame for the analysis. As such, our purpose was to provide a holistic and descriptive account of how the NM reform unfolded naturally within SNIs and affected personnel, rather than to advance specific hypotheses to deductively examine reform impacts. The Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation Institutional Review Board approved the research protocols and informed consent procedures utilized in this study.

Setting

New Mexico is a poor and sparsely populated state. Of its 33 counties, 32 are classified as federally designated Health Professional Shortage Areas or Medically Underserved Areas (U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration 2011). The state is ethnically diverse: American Indians and Hispanics comprise almost 56 % of a population of 2,059,179 (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Alcohol- and drug-induced death rates per capita rank first and second highest, respectively; the age-adjusted suicide rate ranks second (Xu et al. 2010). Seventy-four provider organizations in NM were serving adults with serious mental illness within the public sector at the start of the recent reform (Semansky et al. 2009).

Sample

We studied 14 behavioral health SNIs over 4 years beginning in April 2006. Our fieldwork commenced during the first year of implementation, a period dubbed “Do no harm” by state officials. The daily provision of services in community settings was to remain undisrupted during this period, while the state and VONM concentrated on instituting new processes for enrollment, billing, and governance within the public sector. More substantive changes in payment rates and service provision were to follow in later years (Willging et al. 2007). The SNIs in our study were located in three rural counties and three counties having metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), each chosen for their geographical diversity and catchment area characteristics (e.g., sizeable American Indian and Hispanic populations). The MSAs contained a central city or core of at least 50,000 residents and economically-dependent outlying communities (Office of Management and Budget 2000). The three rural counties lacked MSAs and had population densities that ranged from 7.0 to 13.7 persons per square mile, based on estimates from the 2000 U.S. Census. We refer to these two types of SNI settings as rural and urban.

Commonalities in structure and population served by community-based organizations that care for low-income and indigent populations are identified in the EPIS model that guides this research. Such organizations may operate under state, county, municipality or tribal contracts for one or more type of services that are characteristic of SNIs (Aarons et al. 2011a). For example, many of the organizations that provide mental healthcare also offer substance abuse treatment and child welfare services, as well as programs for homeless individuals and persons involved in justice or correctional systems. That is not to say that all community-based organizations provide all of the above mentioned services. The specific services provided, or populations served, are generally a function of funding opportunities and availability, thus a given organization is likely to have multiple service contracts (Gronjberg 1992).

In keeping with the EPIS model and a purposive approach to qualitative sampling (Patton 2002), we selected a range of SNIs that, while varying in organizational type, size, and other characteristics (Table 1), provided care to low-income adults with serious mental illness in each of the counties studied. All received the majority of their funding from public sector sources (average of 86.5 and 91.3 % for SNIs in rural and urban settings, respectively). The selected SNIs represented the dominant if not the only provider organizations within a county to serve this population. Within two rural counties, for example, we sampled the entire universe of SNIs. Eight of the SNIs were operated by or located in a community mental health center and provided both mental health and substance use services to adult populations, including those with persistent illnesses and the homeless. The remaining sites that were not affiliated with a community mental health center included two small group practices, three substance abuse treatment centers, and an outpatient program for homeless adults with co-occurring disorders. Importantly, small group practices in rural or underserved areas are considered part of the behavioral health safety net because of direct care given to vulnerable populations and the vital role they play in maintaining local access to treatment (Ormond et al. 2000). Special service programs, such as substance abuse treatment centers and those focused on the homeless, may be viewed as part of the core safety net for similar reasons (Lewin and Altman 2000). As shown in Table 1, half (n = 7) of the SNIs in our study were located in rural counties. The vast majority in both rural and urban counties were nonprofit organizations. Rural and urban SNIs had an average of 11.0 (SD = 6.1) and 12.4 (SD = 11.0) licensed and unlicensed therapists, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating safety-net institutions

| Variable | Rural SNI (n = 7)

|

Urban SNI (n = 7)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | |

| Org. type | ||||

| For-profit | 14.3 | 1 | 14.3 | 1 |

| Nonprofit | 71.4 | 5 | 85.7 | 6 |

| Government | 14.3 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Operated by CMHC | 42.9 | 3 | 71.4 | 5 |

| Total therapists (lic + unlicensed) (M/SD) | 11.0/6.1 | 12.4/11.0 | ||

| % Public sector funding (M/SD) | 86.5/12.8 | 91.3/6.3 | ||

Semi-structured interviews, ethnographic observations, and quantitative surveys with providers and staff were conducted in each SNI 9 months (Time 1 or T1) after initial implementation, and 18 (Time 2 or T2) and 36 months (Time 3 or T3) later. One original agency closed after T1, and a second agency closed after T2, leaving a total of 12 agencies at T3. We conducted supplemental qualitative research with lead administrators in the remaining SNIs between August and September of 2009 after a national competitor, OptumHealth New Mexico (OHNM), replaced VONM as the for-profit behavioral health corporation contracted by the state government to administer public-sector services. For this later work we focused on transition issues that reflected continuity with or divergence from policies under VONM.

We implemented a purposive sampling approach to recruit participants at each SNI. One aim of sample selection in qualitative and mixed-method research is to represent the breadth of views related to study issues (Aarons and Palinkas 2007). Resulting samples should include individuals who can discuss the most relevant issues under investigation (Johnson 1990; Patton 2002). For interviews, we recruited personnel specifically involved in adult service provision at each SNI. At T1, we first interviewed a lead administrator who then referred service providers and support staff for participation. These individuals, in turn, also recommended other co-workers for study inclusion. This sampling approach made it possible to interview all personnel involved in delivering services to adult patients in all but one site. At T2 and T3, we interviewed members of this same cohort if they were still employed by the SNI, their successors, and any new staff hired to work with the population of interest. Table 2 summarizes participant characteristics, comparing those in rural (n = 178; 54.6 %) and urban settings (n = 148; 45.4 %).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participating safety-net institution personnel

| Variable | Rural personnel (n = 178)

|

Urban personnel (n = 148)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 34.8 | 62 | 25.0 | 37 |

| Female | 64.6 | 115 | 74.3 | 110 |

| Missing | 0.6 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 41.6 | 74 | 49.3 | 73 |

| Hispanic | 37.6 | 67 | 28.4 | 42 |

| American Indian | 16.9 | 30 | 19.6 | 29 |

| Other/missing | 3.9 | 7 | 2.7 | 4 |

| Education | ||||

| HS graduate or less | 11.9 | 21 | 9.5 | 14 |

| Some college | 36.5 | 65 | 26.4 | 39 |

| College/some grad. | 18.5 | 33 | 27.0 | 40 |

| Completed grad. | 32.6 | 58 | 37.2 | 55 |

| Missing | 0.6 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Employee type | ||||

| Staff | 20.8 | 37 | 12.2 | 18 |

| Service provider | 57.9 | 103 | 63.5 | 94 |

| Administrator | 20.8 | 37 | 24.3 | 36 |

| Missing | 0.6 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Age (M/SD)** | 47.0/11.8 | 176 | 43.5/12.5 | 147 |

| Job satisfaction (M/SD)** | 2.5/0.8 | 169 | 2.7/0.7 | 144 |

| Org. commitment (M/SD)* | 2.7/0.8 | 171 | 2.9/0.7 | 144 |

| Turnover intentions (M/SD)** | 1.4/1.2 | 169 | 1.0/1.0 | 143 |

The initial reported value is utilized for characteristics that can change over time

P <.05;

P <.01

Most participants across settings were women (64.6 and 74.3 %, respectively). The racial/ethnic diversity did not differ significantly between rural and urban participants, but reflected substantial diversity in both populations. White was the largest racial/ethnic group self-reported among all personnel (41.6 and 49.3 %, respectively), but relatively large proportions of participants self-reported as Hispanic (37.6 and 28.4 %, respectively) or American Indian (16.9 and 19.6 %). Substantial diversity in educational attainment was also evident. Approximately 10 % of rural and urban personnel (11.9 and 9.5 % respectively) had a high school graduate or less than high school graduate educational background, whereas around one-third of rural and urban personnel (32.6 and 37.3 %, respectively) had completed some form of a graduate degree. The majority of participants in both settings were direct care providers (57.9 and 63.5 %, respectively). Rural participants were significantly older (47.0 years old vs. 43.5 years old). As discussed below, rural personnel also reported significantly lower job satisfaction and organizational commitment and higher turnover intentions than their urban counterparts.

Qualitative Component

Data Collection Procedures

Ethnography, a qualitative method involving in-depth interviews and field observations, was used to study reform implementation (change content), in addition to shifting workplaces and employee attitudes in SNIs (reactions to/consequences of change). As in prior research, we anticipated that ethnography could help document intended and unintended effects of government policies on these institutions and personnel, including policies promoting managed care and public–private partnerships (Rylko-Bauer and Farmer 2002; Holland et al. 2007).

We developed and implemented semi-structured interview protocols for administrators, providers, and staff. The protocols utilized between T1 and T3 covered job duties, work-place, and workday; organizational and financial issues; and benefits, drawbacks, and implementation issues associated with the reform. The protocol for the supplemental qualitative component after T3 focused on the transition to OHNM.

Our ethnography team—six anthropologists, one psychiatrist, and one counselor—conducted observations within each agency to clarify contextual factors affecting SNIs under the NM reform. Observations augmented the interview material, enhancing our insight into the work lives of SNI personnel. Ethnographers participated in meetings of psychosocial rehabilitation programs, attended therapeutic support groups, and observed daily operations in SNI reception areas and offices, including the electronic processing of reform-related paperwork. Cumulatively, 1600 hours of observation took place in SNIs for all three data collection periods. Ethnographers prepared field notes that recorded their observations in these settings. Handwritten interview and observation notes were typed and uploaded into an electronic database. All participants agreed to recorded interviews, which lasted 45–60 min, and were professionally transcribed.

Qualitative Analysis

Data analysis proceeded according to a plan that differed for interviews versus observations. To analyze interviews, we developed a coding scheme from transcripts based on the topical domains and questions that comprised the interviews. We utilized NVivo 8 (2008) software to organize and index data and to identify emergent themes and issues relevant to the reform. Observational data were first analyzed by open coding to locate these themes and issues. Focused coding was then used to determine which of these themes and issues emerged frequently and which represented unusual or particular concerns (Emerson et al. 1995; Patton 2002). Coding proceeded iteratively; our ethnography team coded sets of transcripts and observation field notes, created detailed memos linking codes to each theme and issue, and then passed their work to other team members for review. Discrepancies in coding and analysis were identified and resolved during team meetings. For each data collection period, ethnographers developed comprehensive written reports of findings from each field site. Ethnographers compared and contrasted the content of each report to facilitate a coherent and crosscutting description of key themes and issues affecting SNIs and their employees under the NM reform.

Quantitative Component

Measures and Procedures

Consistent with the goals of the qualitative data collection and analyses, our quantitative component focused on the perceptions and attitudes of SNI personnel during the implementation phase of the reform. The same personnel participating in the qualitative study (n = 326) also completed a self-administered structured assessment that elicited quantitative information on demographics and work attitudes. The quantitative analyses contributed to our assessment of the change consequences component of our model (Oreg et al. 2011) through an examination of whether three key work-related employee attitudes—job satisfaction (JS), organizational commitment (OC), and turnover intentions (TI)—may have systematically changed within the SNIs during the reform implementation. Job satisfaction emphasizes the positive orientation that an employee may have towards her/his work experience; OC highlights the extent to which s/he will exert effort to further organizational goals and maintain a relationship to the organization (Glisson et al. 2008). Both dynamics, along with TI, referring here to the degree to which an employee contemplates leaving a job or is seeking employment elsewhere, strongly influence individual and organizational-level work performance and outcomes, including actual employee turnover (Aarons and Sawitzky 2006; Knudsen et al. 2007). The work attitudes of JS, OC, and TI are among the most common work-related personnel-level consequences associated with organizational change (Oreg et al. 2011).

Dependent Variables

For the quantitative analyses, we utilized the work attitudes subscales of JS and OC from the Children’s Services Survey. These subscales were adapted from established measures used in human service organizations (Glisson and James 2002). Previous studies demonstrated good psychometric properties and validity of the scales (Glisson and James 2002; Aarons and Sawitzky 2006; Aarons et al. 2009). Job satisfaction (10 items) measured the degree to which participants were satisfied with various aspects of their job (e.g., “How satisfied are you with your working conditions?”). We omitted one item that referred specifically to children’s services and was not appropriate for the present study. Organizational commitment (13 items) assessed the extent to which participants were committed to their agencies (e.g., “I am proud to tell others that I am a part of this organization”). Items from both measures were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “not at all” to 4 = “to a very great extent”) and demonstrated high internal consistency in the current study (α = .89 for both). Turnover intentions (5 items) examined employee intentions to stay or leave their current job (e.g., “I am actively looking for a job at another agency”) on the same 5-point Likert scale as JC and OC. The items were derived from organizational studies and adapted for use in human service agencies (Knudsen et al. 2003; Walsh et al. 1985) and also demonstrated high reliability in the current study (α = .87).

Independent Variables

The primary emphases of the analyses were to assess for whether employee attitudes changed over time in SNIs as key elements of the reform were implemented and to test for differences between SNI employees working in rural versus urban communities. To evaluate the potential for changes over time, we included two dichotomous variables (T2 and T3) to indicate when the data were collected. With T1 functioning as the omitted reference category, T2 and T3 test for systematic changes from the initial values of the dependent variables. We included a dichotomous indicator (urban = 1/rural = 0) to assess for overall differences between rural and urban SNI personnel. Finally, to examine whether changes over time may be differentially experienced between rural and urban personnel, we created five categorical indicators to reflect the interaction of time period and county type (rural county personnel at T1 is the omitted reference category).

Control Variables

To control for select participant characteristics, we included a continuous measure of age and dichotomous indicators for gender (female = 1/male = 0), education level (college graduate or higher = 1/less than college graduate = 0), and staff type (direct service provider = 1/administrator or support staff = 0), as well as self-reported race/ethnicity (White = 1/non-White = 0). We also incorporated organizational-level variables collected as part of the larger NM study to help control for differences in organizational context (Semansky et al. 2009, 2012). We included the total number of licensed and unlicensed therapist FTEs (a natural log transformation was used in the analyses to minimize the influence of large values), the percentage of funding received from public/governmental funding sources, whether the SNI was operated as part of a community mental health center (yes = 1/no = 0), and whether the SNI was a for-profit entity (yes = 1/no = 0).

Quantitative Analysis

To test if assessments of JS, OC, and TI changed during the reform, we conducted separate multi-level regression analyses with each dependent variable. We chose multi-level techniques due to two possible sources of non-independence among observations: (a) the same individuals were potentially measured multiple times during the study; and (b) the work context may have influenced responses of participants employed in the same SNI. To reduce the likelihood of Type I errors due to clustered data, we developed a three-level random intercept model to account simultaneously for the clustering of observations among participants (up to three observations per person) and of participants within SNIs. However, low SNI-level residual intra-class correlations (ICCs; all less than .012) and likelihood ratio test results comparing nested three-level and two-level models indicated no significant SNI-level clustering after controlling for model covariates. We therefore present the results from the more parsimonious two-level models that account for person-level clustering (the results were nearly identical to the three-level models). For each dependent variable we present two models. In addition to all person- and SNI-level controls, the first model includes indicators that assess for the main effects of time period and county type. The second model includes the categorical indicators needed to assess for an interaction of time-period and county type. The xtmixed procedures in Stata 10.1 were used to conduct the analyses (2007).

As a census of staff present within a sample of 14 SNIs at three time points, participants contributed between one and three observations due to employee turnover and hiring activity at the SNIs. This data collection strategy resulted in three “snapshots” of worker attitudes to evaluate changes across the 14 SNIs at specific time points relative to the reform implementation. The maximum likelihood procedures used to generate the mixed models can effectively utilize unbalanced longitudinal data in which not all cases are represented at each data collection point (Singer and Willett 2003; Skrondal and Rabe-Hesketh 2007).

The 326 personnel contributed 536 observations used in the analyses. A total of 76 personnel participated in all three waves with the remaining 250 exiting or entering during the period of study. Missing data within the observations were minimal (5 % or less for each variable). Imputation with all available data was used to estimate missing data and to retain all participants in each set of analyses.

Comparing the Findings of the Qualitative and Quantitative Components

We first examined our qualitative and quantitative results separately. Those analytic steps provided insight into crosscutting issues under the reform that affected the work environments of SNIs and their personnel between T1 and T3. We then conducted a side-by-side comparison of findings from the two analytical approaches to evaluate the degree of convergence related to our research questions.

Results

Qualitative Component

At T1, SNI personnel identified four change antecedents as key workplace stressors that affected the inner context of reform implementation: (1) time constraints; (2) paperwork burden; (3) demanding patients with complex needs; and (4) provider shortages. According to participants, these stressors predated the recent system-reform initiative in NM, but were exacerbated by change content introduced under the reform, particularly new procedures and requirements for enrollment and reimbursement. SNI personnel encountered difficulties complying with these outer contextual requirements, partly owing to little technical assistance and communication from VONM. Rural SNIs had problems accessing basic IT (e.g., computers, software, and the Internet), adding to these difficulties. The general consensus among SNI personnel was that the requirements increased their workloads. Reactions to such changes were expressed in terms of heightened stress levels that were believed by many to contribute to an overall reduction in employee morale (work-related change consequence).

The change that elicited the most negative employee reactions related to the transition to the untried IT system that VONM developed to process patient enrollment and payment claims across multiple funding sources. In the SNIs we studied, direct service providers were typically tasked with inputting patient information into this system, including detailed demographic and diagnostic information, as part of the enrollment process and as a prerequisite to billing. As a consequence of this change, the majority of providers suggested that this electronic paperwork caused them to short shrift their patients. Some providers decreased the length of their clinical visits with patients by as much as 15 min to enter or update this data, while others did so during the therapeutic encounter. Claims subsequently made to VONM were often denied with little or no explanation; denials frequently were related to a “glitch” in the company’s IT system. As an example, one SNI had an electronic file of 800 claims denied without reason. It took six employees working overtime at the expense of the SNI to review the file to determine the cause—a number symbol used to indicate a patient’s place of residence (e.g., Trailer #19) entered into the electronic enrollment form. Personnel in all but one SNI (an agency run by the state government) described similar scenarios.

It was also common for personnel, particularly SNI administrators, to complain of financially-related changes at T1: reduced reimbursement rates and delayed payments. As a consequence of being unable to bill properly due to IT system setbacks, several administrators reported that their agencies had absorbed the per capita costs of caring for low-income patients. A reaction to the financial issues in other SNIs included stress related to program reductions, job instability, and the agencies themselves.

Our ethnographic fieldwork revealed that transitional and financial problems had not abated by T2 or T3. While IT problems began leveling off, challenges emerged with a new package of bundled services, referred to as Comprehensive Community Support Services (CCSS), which the state government and VONM initiated to coordinate and provide resources for promoting recovery among persons with serious mental illness. Service requirements and utilization guidelines stated that a minimum of 60 % of CCSS must be provided in person and at the patient’s location. SNIs were paid the same rates for CCSS, despite higher transportation costs in rural areas. The SNIs grappled with lost revenue due to the state’s decision to eliminate case management from the Medicaid benefits package while simultaneously shifting the behavioral health system toward CCSS. This shift was complicated by the fact that only minimal CCSS training was available to SNIs; the training largely focused on billing rather than service provision. Within the first 5 months of implementation, traditional managed care techniques were imposed as cost-containment measures to limit the use of CCSS. Providers and support staff spent extra time obtaining VONM authorizations to deliver this service once patients had “maxed out” on their number of 15-min CCSS units (72 units or 6 h of service per month). In some cases, SNIs delivered services to patients without expecting payment.

During this period, several SNIs struggled with the transition to a new fee-for-service reimbursement system, which may have led to heightened administrative costs for SNIs that previously received lump sum compensation through a “1/12th draw-down” mechanism versus Medicaid reimbursements. Through this mechanism, SNIs received funds on a monthly basis from a pre-determined annual allocation. Under the new system, SNIs had to request payment for each service, which created paperwork and uncertainty in the amount of expected monthly income. Increased costs were not offset by an intended reduction of duplicative reporting requirements in publicly-funded programs. Financial problems became pronounced for rural SNIs, which were more reliant than urban SNIs on the 1/12th draw-down mechanism. Such problems became acute for SNIs lacking experience with either managed care or fee-for-service. The majority of these SNIs specialized in substance use treatment services. The leadership of one such SNI and a second SNI focused on the homeless population eventually opted to reduce their participation in VONM-administered services due to cumbersome payment procedures that diverted staff attention and time away from patient care. Both SNIs were fortunate in that they had access to non-state funding (e.g., federal, county, municipality, and tribal).

According to participants, the reform also exacerbated workforce shortages endemic to rural areas. In one rural SNI, leadership reduced clinical staff from 40 to 20 providers. The leadership claimed the agency had been hit hard by reduced reimbursement rates for its residential treatment program ($268 per day for each service user to approximately $100). This decrease eventually led to the demise of the program. Some SNI leaders in the rural counties shortened workweeks or reduced employee salaries to make ends meet.

Workers’ concerns regarding the financial situations of their employers and their own job security emerged in T1 and lingered throughout T2 and T3. Dwindling or nonexistent cash reserves within SNIs, insufficient funding for annual pay increases, and leadership decisions not to recruit needed employees or fill vacated positions to conserve money fueled these concerns. In several SNIs, leadership increasingly emphasized productivity quotas for providers to ensure billable hours, resulting in greater reports of individual stress and burnout, and less time devoted to collective activities that help build camaraderie (e.g., staff meetings, in-service trainings, and holiday parties). Both observations and in-depth interviews suggested that staff felt overwhelmed and, consequently, SNIs were stretched in their capacity to care for the poor and underserved.

In July 2009, the state replaced VONM with OHNM. Because the VONM IT system was considered “proprietary,” OHNM had to create its own. The replacement system was rife with problems, especially in claims processing. A common complaint was that claims data put into the system had simply “vanished.” Frustration among SNI personnel and cash flow problems due to the processing delays mounted, as OHNM failed to pay providers during its first 4 months of operation. State officials were slow to work with OHNM to resolve the payment issue. The increasingly vocal outrage of providers eventually caught the attention of the state legislature and led to corrective action for OHNM in October 2009. The corrective action plan required OHNM to address problems related to claims, service registration, authorizations, and financial reporting (New Mexico Inter-agency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative 2009).

Quantitative Component

As shown in Table 3, several important patterns were evident in the analyses of JS, OC, and TI following the reform implementation. Controlling for a range of personal- and organizational-level characteristics, Models 1, 3, and 5 show that urban personnel had significantly more positive work attitudes (higher JS, higher OC, and lower TI) than their rural counterparts. Model 1 shows that JS was lower at T2 and T3, than at T1. In Model 3, there is evidence that OC decreased at T2 relative to T1, but no difference was found at T3. Models 2, 4, and 6 provide evidence of an interaction effect between time period and county type. In Model 2, JS for rural personnel was significantly lower at T2 and T3 than for rural personnel at T1. While urban personnel at T1 and T2 had higher JS than T1 rural personnel, post-estimation Wald statistic analyses indicated no significant differences when comparing urban personnel at T1 to urban personnel at T2 and T3.

Table 3.

Multi-level, multivariate regression model results for job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions among safety-net institution personnel

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 3

|

Model 4

|

Model 5

|

Model 6

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction

|

Job satisfaction

|

Org. commitment

|

Org. commitment

|

Turnover intentions

|

Turnover intentions

|

|||||||||||||

| β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | |

| Inner context | ||||||||||||||||||

| Personal characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||

| Female | .125 | .082 | .126 | .115 | .082 | .160 | .201 | .079 | .011 | .191 | .079 | .016 | −.337 | .110 | .002 | −.327 | .110 | .003 |

| Age | .007 | .003 | .028 | .007 | .003 | .037 | .005 | .003 | .115 | .005 | .003 | .141 | −.010 | .004 | .026 | −.009 | .004 | .033 |

| White | .032 | .086 | .713 | .038 | .087 | .657 | .099 | .084 | .240 | .104 | .084 | .215 | −.214 | .116 | .066 | −.219 | .117 | .060 |

| College | −.055 | .081 | .501 | −.057 | .081 | .480 | −.119 | .079 | .135 | −.123 | .079 | .120 | .253 | .110 | .021 | .258 | .110 | .019 |

| Provider | −.220 | .071 | .002 | −.214 | .071 | .002 | −.290 | .069 | <.001 | −.279 | .069 | <.001 | .291 | .095 | .002 | .281 | .096 | .003 |

| Organizational characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||

| Public funding (%) | .003 | .003 | .343 | .005 | .003 | .095 | .004 | .003 | .165 | .006 | .003 | .071 | .001 | .004 | .966 | −.002 | .004 | .678 |

| Therapists (n) | −.070 | .037 | .060 | −.089 | .038 | .020 | −.071 | .037 | .054 | −.082 | .037 | .029 | .030 | .051 | .558 | .043 | .052 | .407 |

| CMHC | −.161 | .096 | .096 | −.132 | .097 | .173 | −.254 | .094 | .007 | −.229 | .094 | .015 | .245 | .129 | .059 | .218 | .131 | .095 |

| For-profit | .225 | .185 | .224 | .244 | .185 | .186 | −.076 | .180 | .671 | −.070 | .180 | .698 | .088 | .249 | .723 | .078 | .250 | .756 |

| Outer context | ||||||||||||||||||

| Urban | .365 | .084 | <.001 | .297 | .082 | <.001 | −.443 | .113 | <.001 | |||||||||

| T2 | −.145 | .057 | .011 | −.106 | .057 | .061 | .054 | .077 | .488 | |||||||||

| T3 | −.153 | .060 | .012 | .007 | .060 | .908 | −.110 | .082 | .179 | |||||||||

| T2-rural | −.322 | .083 | <.001 | −.262 | .082 | .002 | .228 | .114 | .045 | |||||||||

| T3-rural | −.225 | .085 | .009 | −.008 | .084 | .928 | −.070 | .116 | .549 | |||||||||

| T1-urban | .220 | .105 | .036 | .198 | .103 | .054 | −.319 | .142 | .024 | |||||||||

| T2-urban | .236 | .102 | .021 | .227 | .100 | .023 | −.419 | .138 | .002 | |||||||||

| T3-urban | .150 | .106 | .157 | .226 | .104 | .030 | −.476 | .144 | .001 | |||||||||

| Intercept | 2.217 | .369 | <.001 | 2.112 | .371 | <.001 | 2.451 | .361 | <.001 | 2.390 | .362 | <.001 | 1.634 | .498 | .001 | 1.717 | .501 | .001 |

P values <.10 are in bold, β coefficient, SE standard error, CMHC community mental health center

As shown in Model 4, a similar pattern was evident for OC. Rural personnel reported lower OC at T2 than at T1. However, no difference was found at T3. Urban personnel at all time periods had higher OC than T1 rural personnel, but post-estimation Wald statistic analyses indicated no significant differences when comparing urban personnel at T1 to urban personnel at T2 and T3. This pattern was replicated for TI in that rural personnel had higher TI at T2 than rural personnel at T1 (but no difference at T3). Urban personnel at all time periods indicated lower TI than rural personnel at T1. However, post-estimation analyses indicated no significant changes among urban personnel TI when comparing T2 and T3 to urban personnel at T1. Additional analyses of the 76 personnel participating at all three time points (available upon request) showed similar result patterns.

Direct service providers reported more negative attitudes in all models (lower JS, lower OC, and higher TI). Older age was associated with higher JS and lower TI. Female personnel had higher OC and lower TI. The organizational characteristic of whether the SNI was operated by a community mental health center was associated with lower JS, lower OC, and higher TI. Larger SNIs, as measured by the number of therapists, were negatively associated with JS and OC.

The person-level ICCs ranged from .546 to .584 across the six models. These results indicated that unmeasured person-level characteristics typically accounted for slightly over half of the residual variance. Additionally, likelihood ratio tests for each analysis confirmed the need for using multi-level modeling strategies to account for the person-level clustering in the data.

Discussion

Comparing Results from the Qualitative and Quantitative Assessments

We used a prospective mixed-method approach to evaluate organizational and personnel outcomes related to the changing conditions of SNIs under the NM reform. Our approach, “concurrent QUAL + quant,” generally demonstrated convergence between the two types of data collected from the same participants (Palinkas et al. 2011). The qualitative data illustrated the interactions between outer and inner contexts, as change content (e.g., new IT systems and administrative procedures, the elimination of case management and simultaneous introduction of CCSS, and the transition from the 1/12th draw-down to a fee-for-service reimbursement system) altered the work environments of SNIs and reportedly threatened their financial stability. Explicit reactions to the change content were less than enthusiastic, as SNI personnel characterized the NM reform as a source of work-related stress. Such stress may partly explain the quantitative results related to change consequences: reduced JS at T3. Qualitative results confirmed that rural personnel experienced more negative reactions to the challenging environment as well as severe organizational and personnel consequences. These findings corresponded to the quantitative results, which showed that rural personnel overall possessed more negative work attitudes. Such differences were exacerbated at T2 of the study. Table 4 summarizes and compares the qualitative and quantitative findings related to the research questions.

Table 4.

Mixed-method results of “concurrent QUAL + quant” analysis of reform impact on safety-net institution personnel

| Approach | Mixed-method results

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Quantitative | Convergence | |

| Question | How has implementation of the reform impacted SNI workplaces and personnel? | ||

| Answer | Key changes included new IT systems and administrative procedures, the elimination of case management and simultaneous introduction of CCSS, and the transition from the 1/12th draw-down to fee-for-service reimbursement. In terms of reactions, SNI personnel complained of heightened stress levels and generally engaged in greater administrative work related to these changes, sometimes at the expense of time spent with patients. On the organizational level, some SNIs provided uncompensated care and/or reduced salaries, staffing, and services. Consequences of change articulated by SNI personnel included greater work burden, lower morale, fear about job security, and financial stress for SNIs | Consequences of change: For the system as a whole (includes all personnel who persisted, entered, or left throughout the study period), the results were mixed. Job satisfaction diminished somewhat between T1 and T3. Organizational commitment appeared to decrease at T2 relative to T1, but no difference from T1 was evident by T3. No changes over time were evident for TI | Qualitative results underscore that SNIs and personnel struggled to adapt to changing organizational conditions under the reform, and may partly explain decreases in job satisfaction captured quantitatively |

| Question | Have rural SNI personnel experienced the reform differently from urban SNI personnel? | ||

| Answer | There was minimal variation in the type of key changes identified by rural and urban SNI personnel. Reactions tended toward greater negativity among rural personnel, who were less familiar with managed care, struggled with the loss of case management as a revenue source and CCSS, and whose SNIs traditionally depended on the 1/12th draw-down. The consequences of greater work burden, lower morale, job security fear, and financial stress for SNIs seemed to disproportionately affect rural personnel. These consequences were possibly intensified by the limited workforce capacity and infrastructure of rural SNIs | Consequences of change: For the system as a whole (includes all personnel who persisted, entered, or left throughout the study period), rural personnel typically indicated lower job satisfaction, lower organizational commitment, and higher turnover intentions overall. The differences were particularly evident at T2. Among rural personnel, all three measures indicated a decrease at T2 relative to T1. However, no such decrease from T1 was identified among urban personnel. For rural personnel, job satisfaction at T3 remained lower than at T1 | Qualitative and quantitative findings suggest that rural personnel experienced more negative reactions to changes under the reform |

Implementing a statewide behavioral health system transformation requires substantial changes to the administrative and practice activities of personnel across many different organizations. The process of adapting to these changes, even if beneficial to an organization or a system in the long run, is likely to create challenges for staff. If this process is not well managed and supported, the difficulties that employees encounter can contribute to negative work attitudes and ultimately turnover (Aarons et al. 2011b). The quantitative results from the current study suggest an overall reduction in JS among all employees relative to T1, shortly after the reform was officially inaugurated. Overall, rural staff indicated lower JS, lower OC and higher TI than urban staff. A closer examination of differentiation between rural and urban personnel indicated that rural staff tended to report worsening conditions between T1 and T2. The qualitative interviews used to document staff reactions to shifting a second time to a new managed care organization responsible for administering and financing services suggest that this later transition, occurring after T3, may have further undermined employees’ resilience and adaptation as well as the financial health of SNIs.

Consistent with the quantitative results, service providers may have also experienced particular stresses as they reported more negative assessments of the system change than administrators and support staff. In our qualitative work, they responded to the reform with complaints about heightened administrative burden, contending that it diverted their time from patient care. This burden was largely defined in terms of electronic paperwork related to patient enrollment and accessing service authorizations or payment. These criticisms reflected the changing work realities of employees across SNIs, despite the diversity in organizational type, size, and geographical location, and contributed to leadership decisions in two sites to reduce their organization’s participation in VONM-administered services. Not all sites, such as the larger community mental health centers, were able to limit their involvement in these services, given their particular reliance on Medicaid funding managed by the state’s private contractor.

Qualitative data analysis demonstrated that SNIs experienced marked increases in workload and financial stress, especially in rural areas. Other consequences included staff turnover in the rural SNIs where personnel reported a high level of financial stress under the reform. One rural community mental health center had a complete turnover in specialty service provider and support staff between T2 and T3. Such turnover may affect continuity in care for people with behavioral health concerns (Aarons et al. 2009). The reality of SNIs reducing services or closing their doors because of the reform emerged, suggesting that not all agencies were equally resilient or adaptable. One urban and one rural SNI closed between T1 and T3; another rural SNI closed soon after T3. Thus, individuals needing care were likely to suffer because the reform complicated service provision within SNIs.

Our combined findings raise concern about system-level implementation processes and the reform’s capacity to streamline requirements and reduce administrative burden and costs for SNIs. The state’s decision to contract with a single corporation facilitated increased centralization and cost-containment via rigid spending and reimbursement rules, without decreasing expense or bureaucracy, a primary objective of the reform’s architects (Hyde 2004). Rural SNIs appeared to be especially vulnerable under the NM reform. The findings underscore the need to support rural SNIs that often lack fiscal reserves and frequently have limited infrastructure to help them weather transitions (Institute of Medicine 2005). In our study, rural SNIs manifested less capacity than urban SNIs to protect personnel from the challenges of system reform, particularly those related to unfamiliar managed care protocols. This issue proved important because the most decisive changes for SNIs occurred between T1 and T2.

Policy Implications

This study illustrates how a reform initiated at the outer context can impact the workplaces, attitudes, and lived realities of frontline service providers and staff within safety-net settings. How key elements of a reform, or change content, are introduced is likely to influence the reactions of individuals on the ground, and can lead to adverse or unintended consequences for SNIs. One point of illustration relates to the ongoing IT challenges under the NM reform. Here, state officials were interested in pursuing a uniform approach to billing and reimbursement across disparate public sector funding streams. However, state officials did not accurately gauge the capability of either VONM or OHNM to establish and operate the IT systems required to implement this approach. Both companies advanced IT systems that were not based on input from the intended users, i.e., SNI personnel, or piloted in advance to identify and rectify problems prior to implementation. Both companies were also lax in providing intended users with technical assistance to utilize these systems or help to shore up their in-house computer infrastructures. It is tempting to gloss over the resulting IT challenges under the NM reform as mere technical matters requiring technical solutions from outer context actors. Yet, state officials and their corporate partners were generally sluggish to overcome these IT challenges or to prevent them from reoccurring. The reactions of SNI personnel to both companies’ IT systems were resoundingly negative, and appeared to contribute to a sense of widespread dissatisfaction with the NM reform. The consequences (e.g., increased administrative work and payment problems) for SNIs were also immense, as they weakened their financial bottom lines.

Notwithstanding IT problems, large-scale system change is likely to generate some disgruntlement for SNI personnel in the short run, as workers acquaint themselves with unfamiliar and evolving procedures. The prospect of organizational change can also be unsettling to employees (Aarons et al. 2011b; Frederickson and Perry 1998; Kelman 2005), with new administrative duties and responsibilities contributing to “feelings of uncertainty and ambiguity” (Singer and Yankey 1991), possibly rendering them less receptive to reform. Yet, as we document in this study, frequent and ill-defined changes in administrative processes under new policy reforms may add stress that can also undermine staff receptivity, particularly when workers are not given adequate time and resources to prepare on the front end, and the need for these changes and their expected impacts are not clearly communicated to them (Ingraham 1997). Without careful planning, such changes can affect employee morale, short- and long-term productivity, turnover intentions, subsequent turnover, organizational effectiveness, and capacity to respond proactively to system change (Aarons et al. 2011; Gray et al. 1996; Jayaratne and Chess 1984). The financial costs of adjusting to these changes can also compromise the resiliency of the SNIs, especially in rural areas where agencies face disparities in terms of both workforce and infrastructure (Gale et al. 2010; Smalley and Warren 2012).

Scholars of public management offer two important recommendations for successfully promoting organizational change in government bureaucracies (Ingraham 1997; Kelman 2005; Light 2005; Liou and Korosec 2009) that are applicable to SNIs within the inner context of an active implementation phase. First, a change process should not proceed without a thorough understanding of all organizations involved (Ingraham 1997). While the NM reform included a variety of community-based agencies, the planning between staff officials and their corporate partners only superficially considered how limited workforce, infrastructure, and funding within SNIs might affect adaptation to erratic changes in administration and service delivery. By and large, SNI personnel were not part of these discussions. A fuller portrait of both SNIs and their personnel at the onset of a reform is a useful starting point for tailoring technical assistance and capacity-building activities for rural and urban agencies. In this regard, the EPIS model guiding our analysis sheds light on the inner context of organizational and employee characteristics that may be amenable to intervention, i.e., knowledge and skills, climate and culture, leadership, and readiness for and receptivity toward change (Aarons et al. 2011). For example, interventions to improve organizational culture or climate in agencies have shown effectiveness in improving work attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment), reducing staff turnover, and improving patient outcomes (Glisson et al. 2010). Leadership is also associated with organizational characteristics and leader development might be utilized to mitigate the negative impacts of organizational stress during a major system change (Aarons et al. 2011).

Second, most scholars generally agree that a successful reform hinges on development and utilization of feedback mechanisms that engage workers in reform processes (Kelman 2005; Light 2005; Liou and Korosec 2009), in addition to collaborative efforts to evaluate and monitor these processes as they unfold (Willging et al. 2003). Our findings underscore the need for outer context actors in NM to become more invested in both evaluating and improving system change for SNIs. Throughout the study, the lack of a robust monitoring system made it difficult for state officials and their managed care contractors to be responsive to complaints from providers concerning the reform’s negative influence on SNIs. A monitoring system would make it possible to generate timely information on needed adjustments and how best to carry them out. In the case of NM, such a system would provide a platform to plan for and avoid a repeat of the implementation challenges that occurred during the transition to VONM and then to OHNM, also surfacing earlier in the move to MMC in 1997. Monitoring and planning are not activities to be performed solely by outer context actors but should be undertaken in concert with those persons whose work is affected by the organizational change (Aarons et al. 2011). Importantly, when workers muddling through a reform process feel their concerns are taken seriously, they may also become more likely to support broader system-change efforts (cf. Kelman 2005).

Study Limitations

Although this research clarifies relationships between policy change and SNIs, this work focused only on a subset of adult-serving SNIs affected by reform. The investigation does not assess the experiences of independent practitioners and primary care providers who deliver limited behavioral health services, or providers specializing in treating youth. Nor do we present the perspectives of state officials, managed care personnel, and other stakeholders, such as patients, or assess SNI issues in relation to other reform goals (e.g., promotion of culturally competent, recovery-oriented services, and development of community-based systems of care). Such perspectives are considered in separate publications by the research team. Although initial data collection occurred during the “Do no harm” period, we cannot present a true “baseline” portrait of the SNIs since the reform was technically underway. The inability to capture qualitative and quantitative measures prior to implementation may inhibit our capacity to determine whether some changes or issues identified in the qualitative data may have predated the reform. Where feasible, we asked personnel to explicitly focus on changes due to reform. For the quantitative analyses, the delayed baseline data suggest that our results concerning systematic changes from the beginning of the study may understate the extent of changes experienced by SNI personnel since the start of the actual reform. Finally, this research may not fully generalize to other states.

Conclusion

Behavioral health reform in NM represented an ambitious undertaking. Driven by outer context concerns, this reform strained the rural and urban safety net, adversely impacting the work environments of agencies providing the bulk of care to adults with serious behavioral health issues. Rural agencies and their staff appeared particularly imperiled. The challenges faced by SNIs in our study may be averted through greater attention to IT issues, local contextual conditions, workforce, infrastructure, and escalating administrative costs under managed care. The effects of large-scale system change on these struggling agencies and their employees deserve careful monitoring, preferably through mixed-method analytic research.

Our study is the first to apply the EPIS model to examine the inner context of the active implementation phase of a statewide policy initiative from a mixed-method perspective (Aarons, et al. 2011a). Our findings illustrate the degree to which the complexity of rural behavioral health systems can be underestimated by state policymakers, cautioning them to fully assess these systems during the exploration, preparation, implementation, and sustainment phases of a major reform. Our findings should prove instructive to other states preparing to respond to major changes introduced under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), including coverage expansion and greater integration of physical and mental healthcare. Without concerted efforts from state and local governments to better resource and manage transition processes and to build capacity, particularly IT capabilities, within SNIs, these agencies will be hard pressed to care for their existing clienteles and the increasing numbers of persons who gain health insurance and seek help at their doorsteps. Future avenues of research include applying the mixed-method analytical approach successfully utilized in NM to multi-state studies of the differential impacts of the PPACA on administration and practice in rural and urban SNIs specializing in behavioral health care, and investigations of strategies or interventions to buffer these essential service providers against reform-related stress.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH076084) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The methods, observations, and interpretations put forth in this study do not necessarily represent those of the funding agencies. The authors wish to thank Caroline Bonham, Patricia Hokanson, Miria Kano, Louise Lamphere, Jill Reichman, Rafael Semansky, Gwen Saul, Paula Seanez, and Marnie Watson for their contributions to this study. They also wish to express appreciation to the research participants for their generous assistance and cooperation.

Footnotes

The research was presented at the Seattle Implementation Research Conference in Seattle, WA, on October 14, 2011.

Contributor Information

Cathleen E. Willging, Email: cwillging@pire.org, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Behavioral Health Research Center of the Southwest, 612 Encino Place NE, Albuquerque, NM 87102, USA

David H. Sommerfeld, Email: dsommerfeld@ucsd.edu, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive (0812), La Jolla, CA 92093-0812, USA

Gregory A. Aarons, Email: gaarons@ucsd.edu, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive (0812), La Jolla, CA 92093-0812, USA

Howard Waitzkin, Email: waitzkin@unm.edu, Department of Sociology, University of New Mexico, MSC 05 3080, 1070 Social Sciences Building, 1915 Roma NE, Room 1103, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA.

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011a;38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Palinkas L. Implementation of evidence-based practice in child welfare: Service provider perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;34(4):411–419. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Sawitzky AC. Organizational climate partially mediates the effect of culture on work attitudes and staff turnover in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33(3):289–301. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0039-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Sommerfeld DH, Hecht DB, Silovsky JF, Chaffin MJ. The impact of evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity monitoring on staff turnover: Evidence for a protective effect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(2):270–280. doi: 10.1037/a0013223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Sommerfeld D, Willging CE. The soft underbelly of system change: The role of leadership and organizational climate in turnover during statewide behavioral health reform. Psychological Services. 2011b;8(4):260–281. doi: 10.1037/a0026196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Mental Health Administration. Financing results and value in behavioral health services. Albuquerque, NM: American College of Mental Health Administration; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bird DC, Dempsey P, Hartley D. Addressing mental health workforce needs in underserved rural areas: Accomplishments and challenges. Portland, ME: Maine Rural Health Research Center, Muskie Institute, University of Southern Maine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham P, McKenzie K, Taylor EF. The struggle to provide community-based care to low-income people with serious mental illnesses. Health Affairs. 2006;25:694–705. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon PH, Kenkel MB, Shaw DV. Advancing federal policies in rural mental health. In: Smalley KB, Warren JC, Rainer JP, editors. Rural mental health: Issues, policies, and best practices. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Donald A. The Wal-Marting of American psychiatry: An ethnography of psychiatric practice in the late 20th Century. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2001;25:427–439. doi: 10.1023/A:1013063216716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Felt-Lisk S, Silberman P, Hoag S, Slifkin R. Medicaid managed care in rural areas: A ten-state follow-up study. Health Affairs. 1999;18(2):238–245. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson DC, Perry JL. Overcoming employee resistance to change. In: Ingraham PW, Thompson JR, Sanders RP, editors. Transforming government: Lessons from the reinvention laboratories. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1998. pp. 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Gale JA, Shaw B, Hartley D, Loux S. The provision of mental health services by rural health clinics. Portland, ME: Maine Rural Health Research Center; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, James LR. The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2002;23(6):767–794. doi: 10.1002/job.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Mayberg S, et al. Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: Implications for research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35(1–2):98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald SK, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Dukes D, Armstrong KS, et al. Randomized trial of MST and ARC in a two-level evidence-based treatment implementation strategy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:537–550. doi: 10.1037/a0019160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray AM, Phillips VL, Normand C. The costs of nursing turnover: Evidence from the British National Health Service. Health Policy. 1996;38(2):117–128. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00854-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronjberg KA. Nonprofit human service organizations: Funding strategies and patterns of adaptation. In: Hasenfeld Y, editor. Human services as complex organizations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hauenstein EJ, Petterson S, Rovnyak V, Merwin E, Heise B, Wagner D. Rurality and mental health treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;34(3):255–267. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland D, Nonini DM, Lutz C, Bartlett L, Frederick-McGlathery M, Guldbrandsen TC, et al. Local democracy under siege. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde PS. State mental health policy: A unique approach to designing a comprehensive behavioral health system in New Mexico. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55(9):983–985. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham PW. Conclusion: Transforming management, managing transformation. In: Ingraham PW, Thompson JR, Sanders RP, editors. Transforming government: Lessons from the Reinvention Laboratories. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Quality through collaboration: The future of rural health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaratne S, Chess WA. Job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover: A national study. Social Work. 1984;29(5):448–453. doi: 10.1093/sw/29.5.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JC. Selecting ethnographic informants. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman S. Unleashing change: A study of organizational renewal in government. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Research participation and turnover intention: An exploratory analysis of substance abuse counselors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(2):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Johnson JA, Roman PM. Retaining counseling staff at substance abuse treatment centers: Effects of management practices. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24:129–135. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D, Gale J, Bird D, Hartley D. Medicaid managed behavioral health in rural areas. The Journal of Rural Health. 2003;19(1):22–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2003.tb00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamphere L. Providers and staff respond to Medicaid managed care: The unintended consequences of reform in New Mexico. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2005;19(1):3–25. doi: 10.1525/maq.2005.19.1.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Finance Committee. Audit of Medicaid managed care program (SALUD!) cost effectiveness and monitoring. Santa Fe: State of New Mexico Legislative Finance; 2000a. [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Finance Committee. Audit of Medicaid managed care program (SALUD!) cost effectiveness. Santa Fe: State of New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee; 2000b. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin ME, Altman S, editors. America’s health care safety-net: Intact but endangered. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light PC. The four pillars of high performance: How robust organizations achieve extraordinary results. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liou KT, Korosec R. Implementing organizational reform strategies in state governments. Public Administration Quarterly. 2009;33(3):429–452. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan J. It gets better if you do? Measuring quality care in Puerto Rico. Medical Anthropology. 2010;29(3):303–329. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2010.488663. doi: 10(1080/01459740).2010.488663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New Mexico Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative. Statewide behavioral health services contract. Santa Fe, NM: State of New Mexico; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- New Mexico Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative. Behavioral Health Collaborative Imposes Sanctions on OptumHealth New Mexico for Provider Payment Problems. 2009 (press release). Retrieved from http://www.bhc.state.nm.us/pdf/bhnews/OHNM-Corrective-Action-NR.pdf.

- NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. Version 8 (Computer Software) Doncaster, Australia: QSR International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Management and Budget. Standards for defining metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas. Fed Reg. 2000;65:249. [Google Scholar]

- Oreg S, Vakola M, Armenakis A. Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2011;47(4):461–524. doi: 10.1177/0021886310396550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ormond BA, Wallin S, Goldenson SM. Supporting the rural health care safety net (Occasional Paper 36) Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M, Landsverk J. Mixed method designs in implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(1):44–53. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rylko-Bauer B, Farmer P. Managed care or managed inequality? A call for critiques of market-based medicine. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2002;16(4):476–502. doi: 10.1525/maq.2002.16.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semansky RM, Altschul D, Sommerfeld D, Hough R, Willging CE. Capacity for delivering culturally competent mental health services in New Mexico: Results of a statewide agency survey. Administration and Policy in Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36(5):289–307. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0221-3. doi:110.1007/s 10488-009-0221-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semansky RM, Hodgkin D, Willging CE. Preparing for a public sector mental health reform in New Mexico: The experience of agencies serving adults with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal. 2012;48(3):264–269. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9418-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SJ. Governing how we care: Contesting community and defining difference in US Public Health Programs. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Singer MI, Yankey JA. Organizational metamorphosis: A study of eighteen nonprofit mergers, acquisitions, and consolidations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 1991;1(4):357–369. doi: 10.1002/nml.4130010406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]