Abstract

F1-ATPase is a rotary motor protein driven by ATP hydrolysis. The rotary motion of F1-ATPase is tightly coupled to catalysis, in which the catalytic sites strictly obey the reaction sequences at the resolution of elementary reaction steps. This fine coordination of the reaction scheme is thought to be important to achieve extremely high chemomechanical coupling efficiency and reversibility, which is the prominent feature of F1-ATPase among molecular motor proteins. In this study, we intentionally change the reaction scheme by using single-molecule manipulation, and we examine the resulting effect on the rotary motion of F1-ATPase. When the sequence of the products released, that is, ADP and inorganic phosphate, is switched, we find that F1 frequently stops rotating for a long time, which corresponds to inactivation of catalysis. This inactive state presents MgADP inhibition, and thus, we find that an improper reaction sequence of F1-ATPase catalysis induces MgADP inhibition.

The F1-ATPase is a motor protein which exhibits rotary motion as a result of catalytic hydrolysis of ATP. Here, the authors investigate how the sequence of this reaction influences molecular rotation, showing that premature product release can result in protein inactivation.

The F1-ATPase is a motor protein which exhibits rotary motion as a result of catalytic hydrolysis of ATP. Here, the authors investigate how the sequence of this reaction influences molecular rotation, showing that premature product release can result in protein inactivation.

F1-ATPase (α3β3γδε), a catalytic sub-complex of F0F1-ATP synthase, is a rotary motor protein fuelled by ATP hydrolysis1,2,3. Three subunits (α3β3γ) function as the minimum component of the rotating system, where the α3β3 unit forms a cylindrical stator and the γ rotor subunit penetrates the centre of the cylinder4. The catalytic sites for ATP hydrolysis are located on each interface between the α and β subunits, mainly on the β subunits, and the three β subunits are always in different catalytic states4. The interconversion of the catalytic states of β subunits, which induces their conformational transition, drives the rotation of the γ subunit5,6,7.

The rotary motion of F1 can be directly visualized by optical microscopy8,9,10. The unitary step size of the rotation of F1 is 120°, and each step is coupled to a single turnover of ATP hydrolysis11. The 120° step is further divided into 80° and 40° sub-steps12,13. The 80° sub-step is triggered by ATP binding and ADP release, each of which occurs on different β subunits14. The 40° sub-step is triggered by ATP hydrolysis and release of inorganic phosphate (Pi), which also occurs on different β subunits14,15. The catalytic state of the β subunits is tightly coupled to the rotation of the γ subunit; thus, F1 can synthesize ATP from ADP and Pi when the γ subunit is forcibly rotated in the reverse direction16,17. Mechanically induced ATP synthesis is the physiological role of F1 of F0F1-ATP synthase, in which F0, a proton-driven motor protein, compels F1 to rotate in the reverse direction for ATP synthesis. This reversibility of chemomechanical coupling is the prominent feature of F1 among other motor proteins.

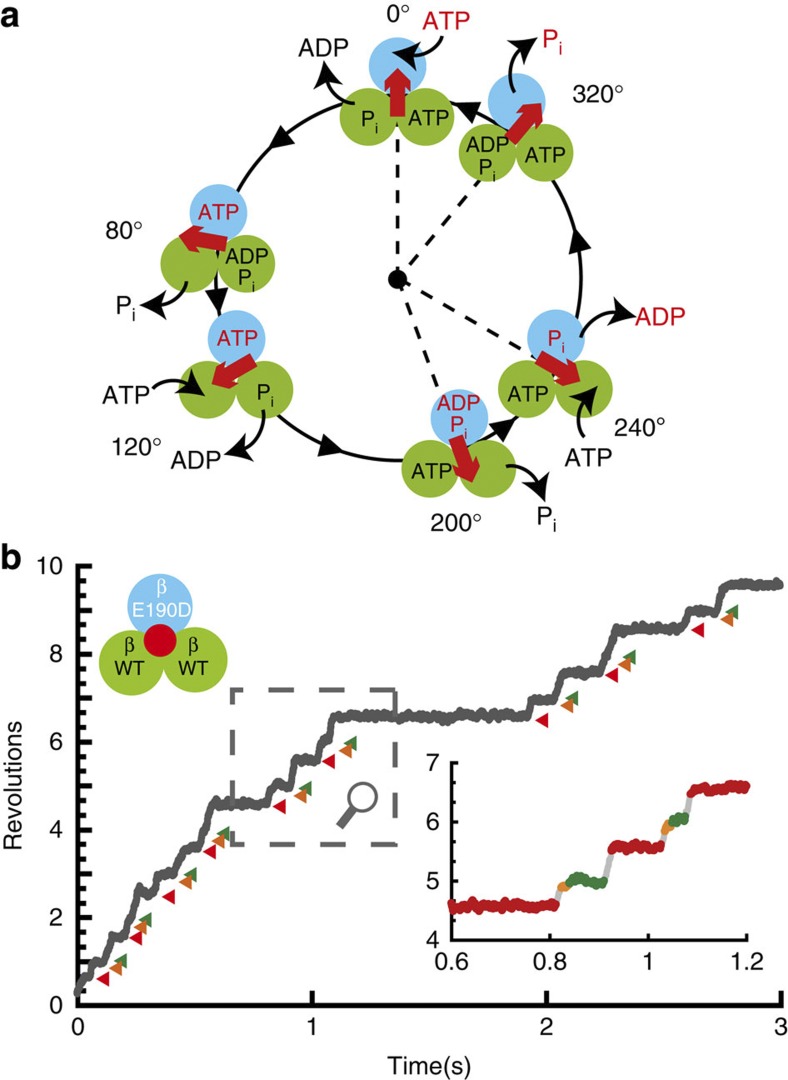

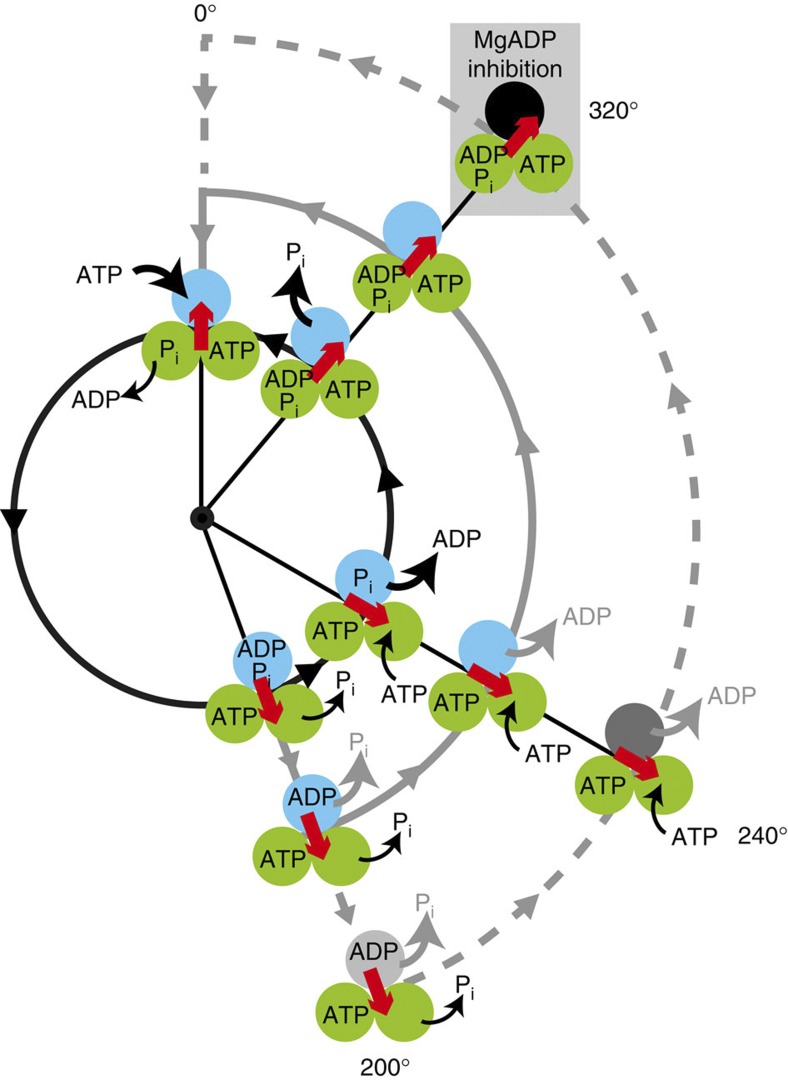

To achieve reversibility of chemomechanical coupling, fine coordination of the reaction sequence, which properly induces the conformational transition of β subunits, is required. To understand the fine coordination mechanism, extensive studies have been dedicated to unveiling the basic reaction scheme for the rotation and catalysis of F1, focusing on the catalytic turnover of individual β subunits (Fig. 1a). In this scheme, an individual β subunit binds to ATP when the γ subunit is oriented at a specific angle, and the binding angles for the individual β subunits differ by ±120°. Each β subunit hydrolyses the bound ATP into ADP and Pi after γ rotates another 200° from the ATP-binding angle18. In addition, the produced ADP and Pi are released from the catalytic site after additional 40° and 120° rotations, respectively14,15,19,20. When the γ subunit returns to the original angular position, the β subunit initiates the next round of catalysis by binding to a new ATP. Thus, the reaction sequences among the three β subunits are well coordinated at the resolution of elementary reaction steps, which contributes to the reversibility of the chemomechanical coupling on F1.

Figure 1. Chemomechanical coupling scheme of F1-ATPase.

(a) The circles and red arrows represent the catalytic state of the β subunits and the angular positions of the γ subunit. Each β subunit completes one turnover of ATP hydrolysis in a turn of the γ subunit, where the three β subunits vary in their catalytic phase by 120°. Regarding the catalytic state of the top β subunit (cyan), ATP binding, hydrolysis, ADP release and inorganic phosphate (Pi) release occur at 0°, 200°, 240° and 320°, respectively. (b) Time course of the rotation of the hybrid F1-ATPase, α3β(E190D) β2γ, in the presence of 1 mM ATP. Red, orange, and green represent the pause at 200°, 320°, and 360° for β(E190D), respectively. The inset shows a magnification of the time course.

Then, the question arises as to what happens when the reaction sequence of F1 is changed. In the case of the hydrolysis step, although the timing of hydrolysis shifts by 80° relative to the authentic reaction angle, F1 drives the rotation without interruption, demonstrating the robustness of the chemomechanical coupling of F1 (ref. 21). In contrast, in the case of other elementary reaction steps, such as Pi release, the effect of timing on rotary motion has not been examined so far, although we established a method to change the timing of Pi release by using single-molecule manipulation15. In particular, the free energy change resulting from Pi release was relatively high among reaction steps; that is, the rotary torque was mainly generated by Pi release, and therefore, the effect of the timing of Pi release on rotary motion is expected to be larger than that of other reaction steps14,15,22. In addition, the timing of Pi release in F1 is different from that in other motor proteins fuelled by ATP hydrolysis, such as kinesin and myosin, in which Pi release occurs before ADP release23,24, and this difference is thought to be important for the reversibility of the chemomechanical coupling mechanism of F1 (ref. 15).

In this study, to further investigate the role of the finely coordinated reaction sequence of F1, we evaluate the effect of changing the timing of Pi release on the chemomechanical coupling mechanism. When Pi is released before ADP, we find that F1 frequently stops rotating for a long time, which corresponds to inactivation of catalysis. This inactive state presents MgADP inhibition, and thus, we find that an improper timing of Pi release induces MgADP inhibition.

Results

Rotation of hybrid F1

We observed the rotation of hybrid F1 carrying one β(E190D), that is, α3β2β(E190D)γ, in the presence of 1 mM ATP. Glu190 of the β subunit, the so-called ‘general base’, is known to be one of the most important residues for hydrolysis25,26,27, and its substitution into aspartic acid causes distinctively slow hydrolysis of ATP28 and strong temperature sensitivity29. Therefore, the kinetic steps of the mutated catalytic site are easily distinguished from those of the other two sites. In the presence of 1 mM ATP, the hybrid F1 showed three distinctive dwells caused by the incorporated β(E190D); the dwell for the temperature-sensitive reaction at 0° (τ=32 ms)15,29, which is the same as the dwell at the ATP-binding angle, ATP hydrolysis at 200° (τ=318 ms), and Pi release at 320° (τ=9 ms) (cyan in Fig. 1a,b). The dwell time for Pi release at 320° was prolonged because of the viscous drag of the rotary probe on γ as previously reported30,31. Hereafter, we refer to the angle for ATP hydrolysis by β(E190D) as the catalytic angle.

Single-molecule manipulation to induce Pi release

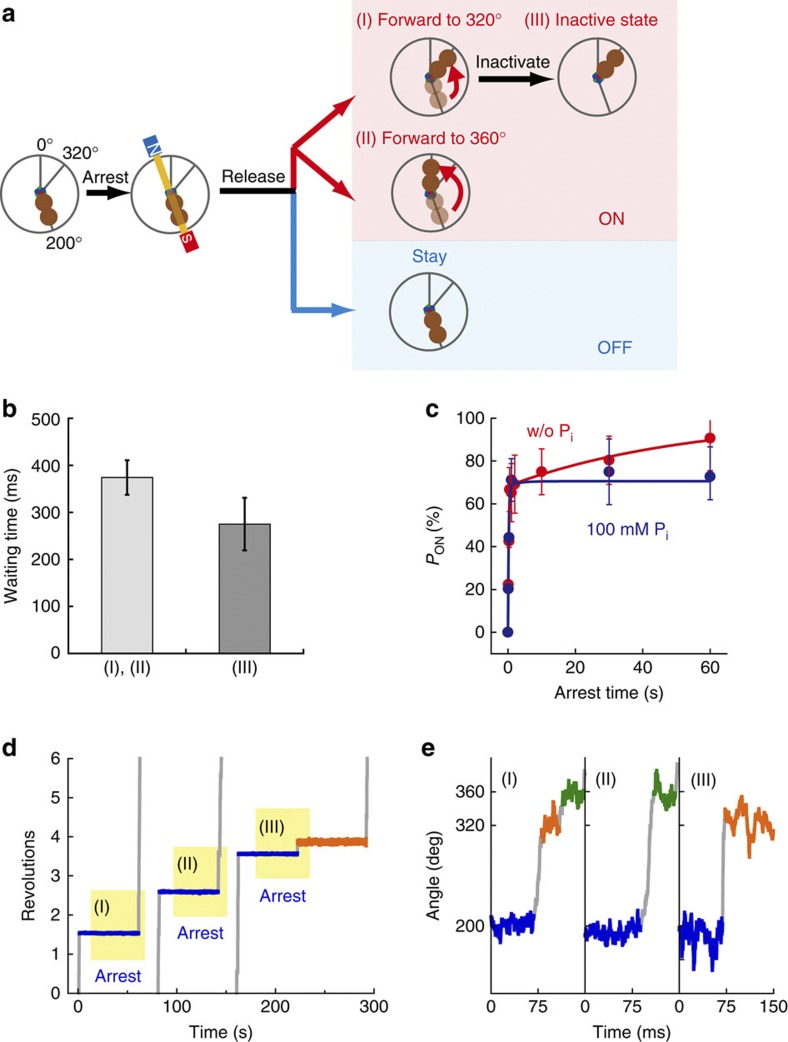

During free rotation, one β hydrolyses ATP and another β releases the produced Pi at the catalytic angle, resulting in a rotation of the γ subunit in an anticlockwise direction (Fig. 1a). In contrast to the free rotation, we recently succeeded in inducing the release of another produced Pi from the same catalytic site used for ATP hydrolysis by arresting the γ subunit for a long time (>10 s)15,22. In this study, we used the same method to induce the release of produced Pi immediately after ATP hydrolysis. For manipulation of γ rotation, a magnetic bead was attached to the γ subunit of F1, and the α3β3 ring was immobilized on the glass surface. When the hybrid F1 showed a pause for ATP hydrolysis by β(E190D) at 200°, we turned on the magnetic tweezers within ~450 ms (Fig. 2a,b) and arrested F1 at ±10° from 200°. After a certain time period had elapsed, we turned off the magnetic tweezers and released F1 from arrest. Then, F1 roughly showed one of two behaviours without exception, as previously reported: rotating forward or restarting the hydrolysis-waiting pause (Fig. 2a). When F1 shows the former behaviour, β(E190D) has already hydrolysed ATP and exerted a torque on the magnetic beads, whereas when β(E190D) shows the latter behaviour, it has not hydrolysed ATP because F1 cannot generate torque unless β(E190D) catalyses hydrolysis. These behaviours are hereafter referred to as ‘on’ and ‘off’, respectively. Then, we measured the probability of the post-hydrolysis state as the probability of the ‘on’ case against the total number of trials, PON. In the absence of Pi in solution, PON increased toward 100% as the arrest time increased; in contrast, in the presence of 100 mM Pi, PON did not change depending on the arrest time, which suggests that PON depends on the time course of Pi release from the catalytic site (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2. Single-molecule manipulation for Pi release.

(a) Schematic representation of manipulation procedures. When the hybrid F1-ATPase paused at 200°; that is, the angle for ATP hydrolysis by β(E190D), we switched on the magnetic tweezers and arrested F1 at ±10° from 200°. After release from arrest, F1-ATPase roughly showed two behaviours: rotating forward to next reaction angle (‘ON’), or staying at the original pausing angle (‘OFF’). In addition, the behaviour of ‘ON’ was classified into three types: (I) rotating forward to 320° and showing the distinctive pause for Pi release (time constant (τ) is ~9 ms); (II) rotating forward to 360° (skip the pause at 320°); or (III) rotating forward to 320° and showing a long pause (τ=~39 s). (b) Hydrolysis-waiting time at 200° before F1-ATPase is arrested with the magnetic tweezers. The average waiting time was 370±37 ms for the behaviours (I) and (II) (light grey), and 275±56 ms for the behaviour (III) (grey). Error bars indicate s.d. (c) Time course of PON. Red and blue points represent PON in the absence or presence of 100 mM Pi, respectively. The number of arrest trials and molecules used for each data point were 23–108 and 8–19. The time courses were fitted with the reaction scheme; F1˙ATP↔˙F1 (ADP+Pi)→F1˙ADP+Pi (solid lines). (d) Example of the time course of the arrest experiments (blue periods) corresponding to the behaviour of (I), (II) and (III), respectively. (e) Magnification of d. Orange and green represent the pauses at 320° and 360°.

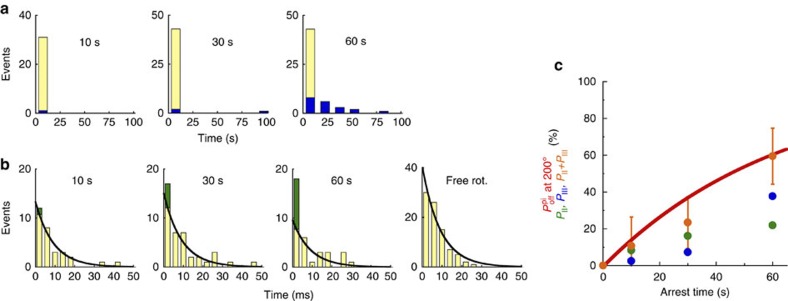

We extensively analysed the ‘on’ case and found that it can be classified into three behaviours; (I) rotating forward to 320°, (II) rotating forward to 360°; that is, skipping the pause at 320°, and (III) rotating forward to 320° and spontaneously stopping the rotation for a long time (Fig. 2d,e). When β(E190D) shows (I), it has hydrolysed ATP during its arrest but has not released the produced Pi because the rate-limiting step at 320° is not hydrolysis by β(WT) but rather Pi release by β(E190D) (Fig. 1a). F1 cannot generate torque at 320° unless β(E190D) releases Pi. When β(E190D) shows (II), it has hydrolysed ATP and simultaneously released the produced Pi, and therefore, F1 has already exerted torque for the step from 320° to 360° driven by Pi release. Regarding the behaviour of (III), we have not identified the chemical state of β(E190D) thus far; however, the pausing angle is the same as that of the MgADP-inhibited state32. Hereafter, we characterize (III). First, we analysed the dwell time at 320° and calculated the probability of occurrence for each behaviour. As shown by the blue bars in Fig. 3a, distinctively long dwell times (longer than 100 ms), which correspond to the behaviour of (III), can be recognized. Then, we calculated the probability of occurrence of (III), that is, PIII, as the number of events corresponding to the blue bars divided by total number of events in the histograms, and found that PIII increased as the arrest time increased. As shown in Fig. 3b, we changed the time scale of the histogram to shorter bins (4 ms), and found that the histogram deviated from a single exponential decay model as the arrest time increased. For example, at 60 s of arrest, the first bin (<4 ms) contained many more events in which β(E190D) skipped the pause at 320° than expected from a single exponential decay that fit the data well after the first bin with a time constant of 9 ms (black line in Fig. 3b), which was consistent with that of Pi release in free rotation (rightmost panel in Fig. 3b). Therefore, the first bin deviated from single exponential decay because of the behaviour of (II); accordingly, the first bin potentially includes behaviours of both (I) and (II). To calculate the probability of occurrence of (II), that is, PII, we fit the data points of the histograms (except for the first bin) to a single exponential curve with 9 ms as the time constant of Pi release. PII was determined as the number of events that deviated from the single exponential curve in the first bin (green bars in Fig. 3b) divided by total number of events of the histogram in Fig. 3a. In addition, we also calculated the probability of occurrence of (I), that is, PI, as the number of remaining events (light yellow bars in Fig. 3b) divided by total number of events.

Figure 3. Analysis of the effect of Pi release at 200°.

(a,b) Histograms of the dwell time at 320° after the release from 200° arrest for 10 s, 30 s, and 60 s, or during free rotation. The bin sizes of the histogram are 15 s for a and 4 ms for b. Blue bars in a represent the number of pauses longer than 100 ms (behaviour (III)). The data after first bin in b were well-fitted by the single exponential curve where τ=9 ms (Pi release dwell at 320°). The deviations of the first bins from the single exponential curves are coloured green (behaviour (II)). (c) Probability of Pi release at 200°. The red solid line presents the simulation curve for Pi release calculated from the analysis of PON based on the kinetic scheme as follows: F1·ATP↔ F1·(ADP+Pi)→F1·ADP+Pi. Green, blue and orange points represent the probability of occurrence of II (PII), III (PIII) and their sum (PII+PIII), respectively. PII and PIII were determined from the analysis of b and a, respectively.

Kinetic analysis of Pi release and the inactive state

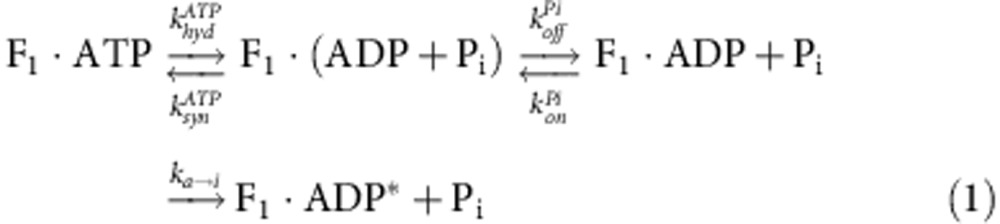

From the analysis of PON based on the irreversible reaction scheme (Fig. 2c) F1·ATP↔ F1·(ADP+Pi)→F1·ADP+Pi, we can calculate the probability of Pi release during arrest as PoffPi, as shown by the red line in Fig. 3c. For example, PoffPi is 37% and 60% for 30-s and 60-s arrest, respectively. Here, we compared PII and PoffPi, and found that PII was much smaller than PoffPi (Fig. 3c, green). As mentioned above, we could not identify the chemical state of (III). Thus, we suspected that (III) was caused by Pi release immediately after ATP hydrolysis and summed PII and PIII. The sum of PII and PIII was almost the same as PoffPi (Fig. 3c, orange), suggesting that (III) was caused by Pi release immediately after ATP hydrolysis. To confirm the relationship between (III) and Pi release, we conducted the arrest measurement in the presence of high [Pi] (~100 mM), where Pi did not affect the kinetics of ATP binding and produced ADP release14,33. When we added more than 10 mM Pi in solution, PIII was completely suppressed toward 0% (Fig. 4a,b), suggesting that (III) was induced after the Pi release. Then, the kinetic scheme of (III) is given below (equation (1)), where, khydATP, ksynATP, koffPi, konPi, and ka→i are the rate constants of ATP hydrolysis, synthesis, Pi release, binding and inactivation of β(E190D), respectively.

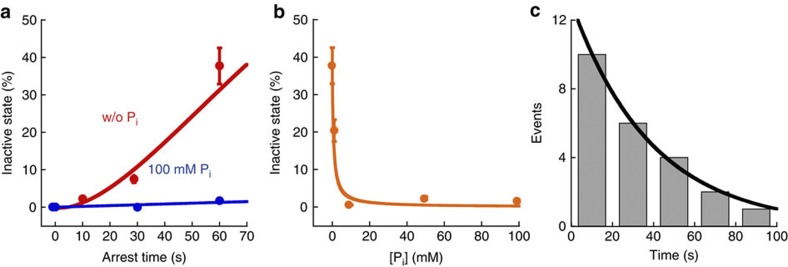

Figure 4. Analysis of the long pause at 320°.

(a) Time course of PIII in the absence (red) or presence of 100 mM Pi (blue). The red solid line is the fitting curve based on the kinetic scheme [1]. The blue solid line is the simulation curve based on the kinetic parameters determined from the fitting of PIII in the absence of Pi. (b) Relationship between PIII for 60 s arrest and Pi concentration. The simulation curve in Fig. 4b was redrawn against the Pi concentration. (c) Histogram of durations of the long pauses at 320° from the experiments of 10–60 s arrests. Solid line represents the fitting with single exponential curve where the time constant (τi→a) is 39 s. Bin size is 20 s.

|

As previously reported, khydATP, ksynATP, koffPi, and konPi were given as 2.3 s−1, 0.8 s−1, 0.021 s−1 and 2 × 103 M−1 s−1, respectively15. Then, from the fitting of PIII in Fig. 4a based on the kinetic scheme as shown above, the only fitting parameter; ka→i, was determined as 0.019 s−1. To verify this kinetic scheme, we fixed the arrest time as 60 s, and we re-plotted PIII against Pi concentration. Based on this kinetic scheme with the determined ka→i, we mathematically reproduced the experimental result of PIII as shown in Fig. 4b. From these results, we confirmed that this inactive state was induced after Pi release at 200° with a rate constant of 0.019 s−1.

We analysed the dwell time for activation from this inactive state (Fig. 4c). As shown in Fig. 4c, the histogram of the dwell time fit well to a single exponential curve, and we determined the time constant of activation, τi→a, as 39 s, which was almost the same as that for activation from an MgADP-inhibited state32. In addition, the aforementioned phenomena in which the addition of a large amount of Pi prohibited F1 from lapsing into the inactive state (Fig. 4a) is a well-known feature of the MgADP-inhibited state34, suggesting that the inactive state revealed in this study corresponds to MgADP inhibition.

Discussion

MgADP inhibition, a common feature of F1-ATPase and ATP synthases from various sources32,34,35,36,37, is the catalytically inactive state. Although many biochemical studies have addressed MgADP inhibition, the mechanism of MgADP inhibition has remained elusive in the context of catalysis-rotation scheme. Here, we propose a simple model for how F1 lapses into the MgADP-inhibited state during catalysis (Fig. 5). We assume that the fundamental principle of MgADP inhibition is the loss of the driving energy of rotation derived from Pi release. Our experimental data indicate that F1 can continue rotating even if it releases Pi before ADP at 200°, suggesting that F1 principally stores the driving energy derived from Pi release in conformation for 320°–360° rotation (grey solid line in Fig. 5). However, with a time constant of 0.019 s−1, F1 dissipates the stored energy during rotation before reaching 320° and lapses into MgADP inhibition at 320° (grey dash line in Fig. 5). The driving force of 320–360° rotation after inhibition is a thermal agitation, as our previous work suggests that thermally agitated rotation of γ over 30° induced activation from the MgADP-inhibited state37. Thus, the MgADP-inhibited state is so stable that it takes a long time to resume rotation, τi→a=39 s (Fig. 4c)32.

Figure 5. Mechanism of MgADP-inhibited state.

Black solid line: the normal reaction pathway of active F1-ATPase. F1-ATPase releases Pi at 320°. Grey lines: alternative reaction pathways. F1-ATPase releases Pi before ADP at 200°. F1-ATPase lapses into MgADP inhibition at 320° with some probability (dashed line).

The crystal structures co-crystallized with azide, including the original structure4,38, revealed that β at 320° (βE) does not bind nucleotides or phosphate. Considering that azide is well known to stabilize the MgADP-inhibited state of F1, these structures demonstrate the structural features of the MgADP-inhibited state. Thus, it is highly probable that β in the 320° state of MgADP-inhibited F1 has no bound nucleotide or phosphate, which is consistent with our model (Fig. 5).

It should be mentioned that the Walker group has challenged our reaction scheme of catalysis and rotation for active F1, on which the present work is based, that is, where Pi is released from β in 320° state. Based on the recent crystal structure of MF1 in which β in the 320° state is bound to Mg-free ADP39, they proposed that Mg and Pi are released before ADP. Although the reason for this apparent discrepancy is not clear, it should be noted that most of the crystal structures solved so far had no bound nucleotide on β in the 320° state; the only exceptions are the above-mentioned structure39 and a structure in a different study40. In addition, there are several experimental differences between the present study and the crystal structure study such as the species from which F1 is derived and the buffer contents. A precise correlation between the crystal structure and the reaction model based on single-molecule experiments remains to be established.

In vivo, F1 forms F0F1-ATP synthase and synthesizes ATP by coupling with a rotary motion driven by F0. Previous studies revealed that MgADP inhibition suppresses ATP hydrolysis but not synthesis41. Recently, the rotary motion of the F0F1 complex coupled to the synthesis of ATP was visualized at the single-molecule level42,43,44. For further understanding of the effect of MgADP inhibition on ATP synthesis, verification by single-molecule measurement of the F0F1 complex is desirable in the future.

Methods

Rotation assay

To visualize the rotation of hybrid F1, α3β(E190D) β2γ, the stator region (α3β(E190D)β2) was fixed on the glass surface, and a magnetic bead (φ=0.3 μm; Seradyn, USA) was attached to the rotor part (γ) as a probe for rotation and manipulation. The experimental procedure was as follows. The flow chamber was constructed from an uncoated top coverslip and a bottom coverslip whose surface was modified with Ni2+NTA. F1 solution, which was diluted in buffer A (50 mM MOPS-KOH, 50 mM KCl and 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0) to a final concentration of 200 pM, was infused into the flow chamber. After 5 min, unbound F1 molecules were washed out with buffer A containing 10% bovine serum albumin, and then streptavidin-coated magnetic beads in buffer A were infused. After 10 min, unbound beads were washed out with buffer A. Finally, buffer A was infused with the indicated amount of ATP or Pi. The rotating beads were observed under a phase-contrast microscope (IX-70 or IX-71; Olympus, Japan) with a × 100 objective lens. The rotation assay was performed at 23 °C.

Manipulation with magnetic tweezers

The stage of the microscope was equipped with magnetic tweezers that were controlled using custom-made software (Celery, Library, Japan). The rotary motion of the bead was recorded at 30 and 3,000 frames per second, simultaneously (FC300M, Takex, Japan; FASTCAM 1024PCI-SE, Photron, Japan). Images were stored in the hard disk drive of a computer as an AVI file and analysed using custom-made software. From the recorded images at 3,000 frames per second, we judged whether the operations precisely arrested the γ subunit at the targeted angle or not.

Author contributions

R.W. designed and performed experiments and analysed data; H.N. designed experiments, built whole story and wrote papers with R.W.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Watanabe, R. et al. Timing of inorganic phosphate release modulates the catalytic activity of ATP-driven rotary motor protein. Nat. Commun. 5:3486 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4486 (2014).

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of Noji Laboratory for technical support. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 18074005) to H.N. and (No. 30540108) to R.W. from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan.

References

- Yoshida M., Muneyuki E. & Hisabori T. ATP synthase—a marvellous rotary engine of the cell. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 669–677 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge W., Sielaff H. & Engelbrecht S. Torque generation and elastic power transmission in the rotary FoF1-ATPase. Nature 459, 364–370 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber J. Structural biology: Toward the ATP synthase mechanism. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 794–795 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams J. P., Leslie A. G., Lutter R. & Walker J. E. Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature 370, 621–628 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. & Oster G. Energy transduction in the F1 motor of ATP synthase. Nature 396, 279–282 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer P. D. The binding change mechanism for ATP synthase—some probabilities and possibilities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1140, 215–250 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S. & Warshel A. Electrostatic origin of the mechanochemical rotary mechanism and the catalytic dwell of F1-ATPase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20550–20555 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noji H., Yasuda R., Yoshida M. & Kinosita K. Jr. Direct observation of the rotation of F1-ATPase. Nature 386, 299–302 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetzler D. et al. Microsecond time scale rotation measurements of single F1-ATPase molecules. Biochemistry 45, 3117–3124 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panke O., Cherepanov D. A., Gumbiowski K., Engelbrecht S. & Junge W. Viscoelastic dynamics of actin filaments coupled to rotary F-ATPase: angular torque profile of the enzyme. Biophys. J. 81, 1220–1233 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda R., Noji H., Kinosita K. Jr. & Yoshida M. F1-ATPase is a highly efficient molecular motor that rotates with discrete 120 degree steps. Cell 93, 1117–1124 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda R., Noji H., Yoshida M., Kinosita K. Jr. & Itoh H. Resolution of distinct rotational substeps by submillisecond kinetic analysis of F1-ATPase. Nature 410, 898–904 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimabukuro K. et al. Catalysis and rotation of F1 motor: cleavage of ATP at the catalytic site occurs in 1 ms before 40 degree substep rotation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14731–14736 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi K. et al. Coupling of rotation and catalysis in F1-ATPase revealed by single-molecule imaging and manipulation. Cell 130, 309–321 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe R., Iino R. & Noji H. Phosphate release in F1-ATPase catalytic cycle follows ADP release. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 814–820 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H. et al. Mechanically driven ATP synthesis by F1-ATPase. Nature 427, 465–468 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondelez Y. et al. Highly coupled ATP synthesis by F1-ATPase single molecules. Nature 433, 773–777 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariga T., Muneyuki E. & Yoshida M. F1-ATPase rotates by an asymmetric, sequential mechanism using all three catalytic subunits. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 841–846 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizaka T. et al. Chemomechanical coupling in F1-ATPase revealed by simultaneous observation of nucleotide kinetics and rotation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 142–148 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K. & Hummer G. Phosphate release coupled to rotary motion of F1-ATPase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 16468–16473 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimabukuro K., Muneyuki E. & Yoshida M. An alternative reaction pathway of F1-ATPase suggested by rotation without 80 degrees/40 degrees substeps of a sluggish mutant at low ATP. Biophys. J. 90, 1028–1032 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe R. et al. Mechanical modulation of catalytic power on F1-ATPase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 86–92 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta R., Kikkawa M., Okada Y. & Hirokawa N. KIF1A alternately uses two loops to bind microtubules. Science 305, 678–683 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yount R. G., Lawson D. & Rayment I. Is myosin a ‘back door’ enzyme? Biophys. J. 68, 44S–49S (1995). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich M., Hayashi S. & Schulten K. ATP hydrolysis in the βTP and βDP catalytic sites of F1-ATPase. Biophys. J. 87, 2954–2967 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M., Poser J. W., Allison W. S. & Esch F. S. Identification of an essential glutamic acid residue in the beta subunit of the adenosine triphosphatase from the thermophilic bacterium PS3. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 148–153 (1981). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shawi M. K., Parsonage D. & Senior A. E. Thermodynamic analyses of the catalytic pathway of F1-ATPase from Escherichia coli. Implications regarding the nature of energy coupling by F1-ATPases. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 4402–4410 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T., Tozawa K., Yoshida M. & Murakami H. Spatial precision of a catalytic carboxylate of F1-ATPase beta subunit probed by introducing different carboxylate-containing side chains. FEBS Lett. 348, 93–98 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoki S., Watanabe R., Iino R. & Noji H. Single-molecule study on the temperature-sensitive reaction of F1-ATPase with a hybrid F1 carrying a single β(E190D). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23169–23176 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe R., Hayashi K., Ueno H. & Noji H. Catalysis-enhancement via rotary fluctuation of F1-ATPase. Biophys. J. 105, 2385–2391 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetzler D. et al. Single molecule measurements of F1-ATPase reveal an interdependence between the power stroke and the dwell duration. Biochemistry 48, 7979–7985 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirono-Hara Y. et al. Pause and rotation of F1-ATPase during catalysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13649–13654 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi K., Oiwa K., Yoshida M., Nishizaka T. & Kinosita K. Controlled rotation of the F1-ATPase reveals differential and continuous binding changes for ATP synthesis. Nat. Commun. 3, 1022 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitome N. et al. The presence of phosphate at a catalytic site suppresses the formation of the MgADP-inhibited form of F1-ATPase. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 53–60 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom Y. M. & Boyer P. D. The ADP that binds tightly to nucleotide-depleted mitochondrial F1-ATPase and inhibits catalysis is bound at a catalytic site. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1020, 43–48 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman D. J., Milgrom Y. M., Bramhall E. A. & Cross R. L. Nucleotide-binding sites on Escherichia coli F1-ATPase. Specificity of noncatalytic sites and inhibition at catalytic sites by MgADP. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 28871–28877 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirono-Hara Y., Ishizuka K., Kinosita K. Jr., Yoshida M. & Noji H. Activation of pausing F1 motor by external force. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4288–4293 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler M. W., Montgomery M. G., Leslie A. G. & Walker J. E. How azide inhibits ATP hydrolysis by the F-ATPases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8646–8649 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees D. M., Montgomery M. G., Leslie A. G. & Walker J. E. Structural evidence of a new catalytic intermediate in the pathway of ATP hydrolysis by F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11139–11143 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menz R. I., Walker J. E. & Leslie A. G. Structure of bovine mitochondrial F1-ATPase with nucleotide bound to all three catalytic sites: implications for the mechanism of rotary catalysis. Cell 106, 331–341 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bald D. et al. The noncatalytic site-deficient α3β3γ subcomplex and FoF1-ATP synthase can continuously catalyse ATP hydrolysis when Pi is present. Eur. J. Biochem. 262, 563–568 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe R. et al. Biased Brownian stepping rotation of FoF1-ATP synthase driven by proton motive force. Nat. Commun. 4, 1631 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez M. et al. Proton-powered subunit rotation in single membrane-bound FoF1-ATP synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 135–141 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duser M. G. et al. 36 degrees step size of proton-driven c-ring rotation in FoF1-ATP synthase. EMBO J. 28, 2689–2696 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]