Highlights

-

•

We now have metabolic network models; the metabolome is represented by their nodes.

-

•

Metabolite levels are sensitive to changes in enzyme activities.

-

•

Drugs hitchhike on metabolite transporters to get into and out of cells.

-

•

The consensus network Recon2 represents the present state of the art, and has predictive power.

-

•

Constraint-based modelling relates network structure to metabolic fluxes.

Abstract

Metabolism represents the ‘sharp end’ of systems biology, because changes in metabolite concentrations are necessarily amplified relative to changes in the transcriptome, proteome and enzyme activities, which can be modulated by drugs. To understand such behaviour, we therefore need (and increasingly have) reliable consensus (community) models of the human metabolic network that include the important transporters. Small molecule ‘drug’ transporters are in fact metabolite transporters, because drugs bear structural similarities to metabolites known from the network reconstructions and from measurements of the metabolome. Recon2 represents the present state-of-the-art human metabolic network reconstruction; it can predict inter alia: (i) the effects of inborn errors of metabolism; (ii) which metabolites are exometabolites, and (iii) how metabolism varies between tissues and cellular compartments. However, even these qualitative network models are not yet complete. As our understanding improves so do we recognise more clearly the need for a systems (poly)pharmacology.

Introduction – a systems biology approach to drug discovery

It is clearly not news that the productivity of the pharmaceutical industry has declined significantly during recent years [1–14] following an ‘inverse Moore's Law’, Eroom's Law [11], or that many commentators, for example, see [7,8,14–47], consider that the main cause of this is because of an excessive focus on individual molecular target discovery rather than a more sensible strategy based on a systems-level approach (Fig. 1).

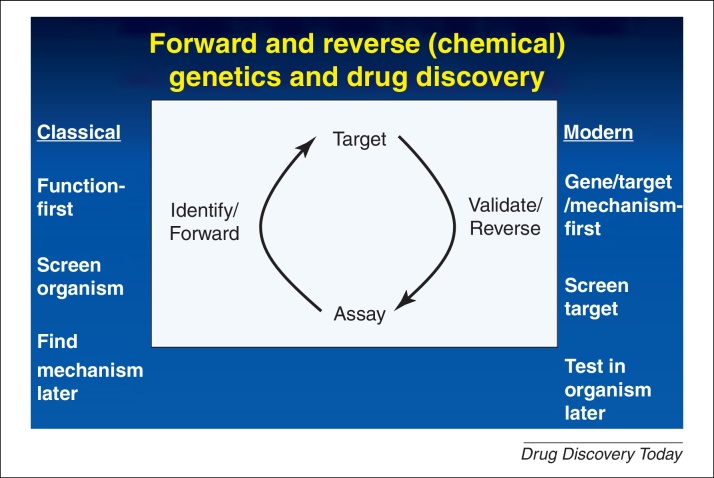

Figure 1.

The change in drug discovery strategy from ‘classical’ function-first approaches (in which the assay of drug function was at the tissue or organism level), with mechanistic studies potentially coming later, to more-recent target-based approaches where initial assays usually involve assessing the interactions of drugs with specified (and often cloned, recombinant) proteins in vitro. In the latter cases, effects in vivo are assessed later, with concomitantly high levels of attrition.

Arguably the two chief hallmarks of the systems biology approach are: (i) that we seek to make mathematical models of our systems iteratively or in parallel with well-designed ‘wet’ experiments, and (ii) that we do not necessarily start with a hypothesis [48,49] but measure as many things as possible (the ’omes) and let the data tell us the hypothesis that best fits and describes them. Although metabolism was once seen as something of a Cinderella subject [50,51], there are fundamental reasons to do with the organisation of biochemical networks as to why the metabol(om)ic level – now in fact seen as the ‘apogee’ of the ’omics trilogy [52] – is indeed likely to be far more discriminating than are changes in the transcriptome or proteome. The next two subsections deal with these points and Fig. 2 summarises the paper in the form of a Mind Map.

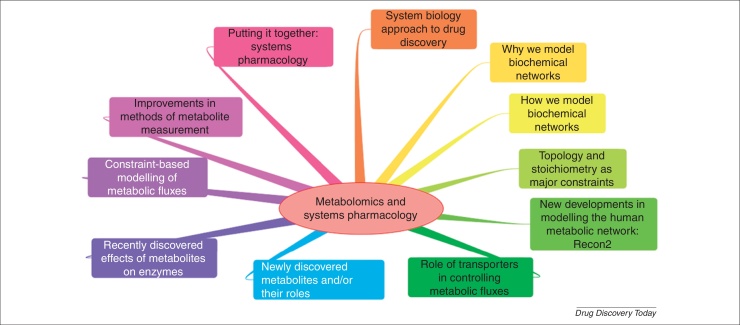

Figure 2.

A Mind Map summarising this paper.

Modelling biochemical networks – why we do so

As set out previously [19,53–55], and as can be seen in every systems biology textbook [56–58], there are at least four types of reasons as to why one would wish to model a biochemical network:

-

•

Assessing whether the model is accurate, in the sense that it reflects – or can be made to reflect – known experimental facts.

-

•

Establishing what changes in the model would improve the consistency of its behaviour with experimental observations and improved predictability, such as with respect to metabolite concentrations or fluxes.

-

•

Analyzing the model, typically by some form of sensitivity analysis [59], to understand which parts of the system contribute most to some desired functional properties of interest.

-

•

Hypothesis generation and testing, enabling one to analyse rapidly the effects of manipulating experimental conditions in the model without having to perform complex and costly experiments (or to restrict the number that are performed).

In particular, it is normally considerably cheaper to perform studies of metabolic networks in silico before trying a smaller number of possibilities experimentally; indeed for combinatorial reasons it is often the only approach possible [60,61]. Although our focus here is on drug discovery, similar principles apply to the modification of biochemical networks for purposes of ‘industrial’ or ‘white’ biotechnology [62–68].

Why we choose to model metabolic networks more than transcriptomic or proteomic networks comes from the recognition – made particularly clear by workers in the field of metabolic control analysis [69–77] – that, although changes in the activities of individual enzymes tend to have rather small effects on metabolic fluxes, they can and do have very large effects on metabolite concentrations (i.e. the metabolome) [78–81]. Thus, the metabolome serves to amplify possibly immeasurably small changes in the transcriptome and the proteome, even when derived from minor changes in the genome [82–84]. Note here that in metabolic networks the parameters are typically the starting enzyme concentrations and rate constants, whereas the system variables are the metabolic fluxes and concentrations, and that as in all systems the parameters control the variables and not vice versa. This recognition that small changes in network parameters can cause large changes in metabolite concentrations has led to the concept of metabolites as biomarkers for diseases. Although an important topic, it has been reviewed multiple times recently [85–105] and, for reasons of space and the rarity of their assessment via network biology, disease biomarkers are not our focus here.

Modelling biochemical networks – how we do so

Although one could seek to understand the time-dependent spatial distribution of signalling and metabolic substances within individual cellular compartments [106,107] and while spatially discriminating analytical methods such as Raman spectroscopy [108] and mass spectrometry [109–113] do exist for the analysis of drugs in situ, the commonest type of modelling, as in the spread of substances in ecosystems [114], assumes ‘fully mixed’ compartments and thus ‘pools’ of metabolites, cf. [115,116]. Although an approximation, this ‘bulk’ modelling will be necessary for complex ecosystems such as humans where, in addition to the need for tissue- and cell-specific models, microbial communities inhabit this superorganism and the gut serves as a source for nutrients courtesy of these symbionts [117]. The gut microflora contain some 1013–1014 bacteria (over 1000 bacterial species, each with their own unique metabolic network) that allow metabolite transformation and cross-feeding within the prokaryotic group and to our gut epithelia; it is also noteworthy that, although antibiotics have an obvious effect here, other human-targeted pharmaceuticals will also undergo microbial drug transformation [117] and cause shifts in gut flora metabolism [118]. Overall, metabolites can be seen as the nodes of (mathematical) graphs [119] – familiar as the conventional biochemical networks of laboratory posters [120], now available digitally – for which the edges reflect enzymes catalysing interconversions of biochemical substances (as well as transporters, see below). Modelling such networks typically involves a four-stage approach [19,20,53,54,121].

In the first, qualitative stage we list all the reactions that are known to occur in the organism or system of interest. It is increasingly possible to automate this [122–126], including through the use of the techniques of text mining [127–131]. A second stage, also qualitative, adds known effectors (activators and inhibitors). The third and fourth stages are more quantitative in character and involve addition of the known, or surrogate [132–134], kinetic rate equations and the values of their parameters (such as Kcat and Km). Given such information, it is then possible to provide a stochastic [135,136] or ordinary [137] differential equation model of the entire metabolic network of interest, typically encoded in the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML; http://sbml.org/) [138], using one of the many suites of software available, for example Cell Designer [139], COPASI [140–143] or Cytoscape [144,145].

Topology and stoichiometry of metabolic networks as major constraints on fluxes

Given their topology, which admits a wide range of parameters for delivering the same output effects and thereby reflects biological robustness [146–149], metabolic networks have two especially important constraints that assist their accurate modelling [58,77,150,151]: (i) the conservation of mass and charge, and (ii) stoichiometric and thermodynamic constraints [152]. These are tighter constraints than apply to signalling networks.

New developments in modelling the human metabolic network

Since 2007 [153,154], several groups have been developing improved but nonidentical [155] models of the human metabolic network at a generalised level [156–159] and in tissue-specific [160–168] forms. Following a similar community-driven [169] strategy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [121], surprisingly similar to humans [170,171], and in Salmonella typhimurium [172], we focus in particular on a recent consensus paper [159] that provides a highly curated and semantically annotated [55,173,174] model of the human metabolic network, termed Recon2 (http://humanmetabolism.org/). In this work [159], a substantial number of the major groups active in this area came together to provide a carefully and manually constructed/curated network, consisting of some 1789 enzyme-encoding genes, 7440 reactions and 2626 unique metabolites distributed over eight cellular compartments. Note, however, that a variety of dead-end metabolites and blocked reactions remain (essentially orphans and widows). Nevertheless, Recon2 was able to account for some 235 inborn errors of metabolism, see also [175], as well as a huge variety of metabolic ‘tasks’ (defined as a non-zero flux through a reaction or through a pathway leading to the production of a metabolite Q from a metabolite P). In addition, filtering based on expression profiling allowed the constrution of 65 cell-type-specific models. Excreted or exometabolites [176–182] are a particularly interesting set of metabolites, and Recon2 could predict successfully a substantial fraction of those [159].

Role of transporters in metabolic fluxes

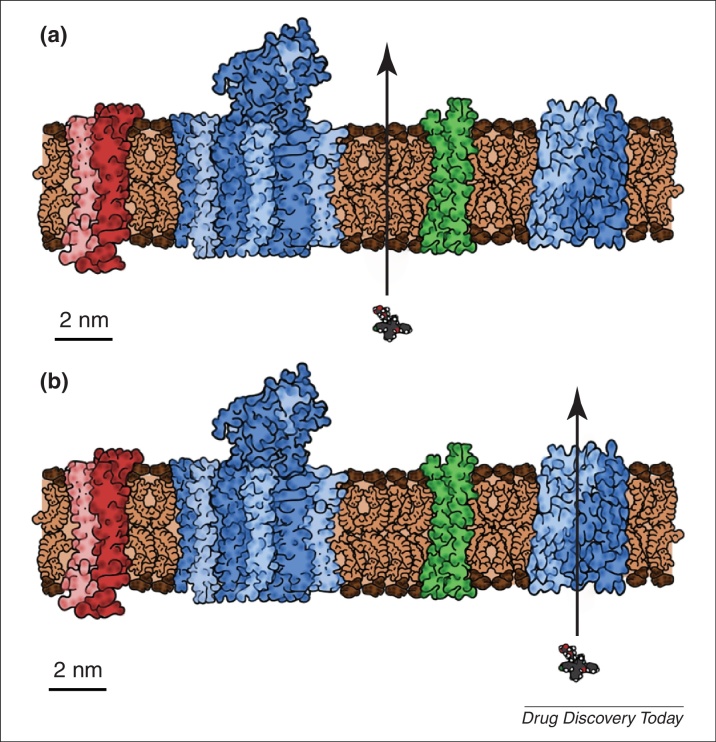

The uptake and excretion of metabolites between cells and their macrocompartments requires specific transporters and in the order of one third of ‘metabolic’ enzymes [153,154], and indeed of membrane proteins [183,184], are in fact transporters or equivalent. What is of particular interest (to drug discovery), based on their structural similarities [185–188], is the increasing recognition [149,189–199] (Fig. 3) that pharmaceutical drugs also get into and out of cells by ‘hitchhiking’ on such transporters, and not – to any significant extent – by passing through phospholipid bilayer portions of cellular membranes. This makes drug discovery even more a problem of systems biology than of biophysics.

Figure 3.

Two views of the role of solute carriers and other transporters in cellular drug uptake. (a) A more traditional view in which all so-called ‘passive’ drug uptake occurs through any unperturbed bilayer portion of membrane that might be present. (b) A view in which the overwhelming fraction of drug is taken up via solute transporters or other carriers that are normally used for the uptake of intermediary metabolites. Noting that the protein:lipid ratio of biomembranes is typically 3:1 to 1:1 and that proteins vary in mass and density [440,441] (a typical density is 1.37 g/ml [441]) as does their extension, for example, see [442], normal to the ca. 4.5 nm [443] lipid bilayer region, the figure attempts to portray a section of a membrane with realistic or typical sizes [441] and amounts of proteins and lipids. Typical protein areas when viewed normal to the membrane are 30% [444,445], membranes are rather more ‘mosaic’ than ‘fluid’ [442,446] and there is some evidence that there might be no genuinely ‘free’ bulk lipids (typical phospholipid masses are ∼750 Da) in biomembranes that are uninfluenced by proteins [447]. Also shown is a typical drug: atorvastatin (Lipitor®) – with a molecular mass of 558.64 Da – for size comparison purposes. If proteins are modelled as cylinders, a cylinder with a diameter of 3.6 nm and a length of 6 nm has a molecular mass of ca. 50 kDa. Note of course that in a ‘static’ picture we cannot show the dynamics of either phospholipid chains (e.g. [448]) or lipid (e.g. [449–451]) or protein diffusion (e.g. [452,453]).

‘Newly discovered’ metabolites and/or their roles

To illustrate the ‘unfinished’ nature even of Recon2, which concentrates on the metabolites created via enzymes encoded in the human genome, and leaving aside the more exotic metabolites of drugs and foodstuffs and the ‘secondary’ [200] metabolites of microorganisms, there are several examples of interesting ‘new’ (i.e. more or less recently recognised) human metabolites or roles thereof that are worth highlighting, often from studies seeking biomarkers of various diseases – for caveats of biomarker discovery, which is not a topic that we are covering here, and the need for appropriate experimental design, see [201]. Examples include N-acetyltaurine [202], 27-nor-5β-cholestane-3,7,12,24,25 pentol glucuronide [203], the cytidine-5-monophosphate:pentadecanoic acid ratio [204], desmosterol [205], F2-isoprostanes [206–208], galactose-6-phosphate [209], globotriaosylsphingosines (lyso-Gb3) [210,211], cyclic GMP-AMP [212,213], hexacosanedioic acid [214], l-homoarginine [94,215,216], d-2-hydroxyglutarate [217,218], 3-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)propionic acid [219], 3-methyl histidine [220], 3-indoxyl sulphate [221], N-methyl nicotinamide [188,222], neopterin [223–225], ophthalmic acid [226], O-phosphoethanolamine [227], 2-piperidinone [228], pseudouridine [229], 4-pyridone-3-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribonucleoside triphosphate [230], Se-methylselenoneine [231], a mammalian siderophore [232–234], sphinganine [235], sphingosine-1-phosphate [236], succinyltaurine [237] and 3-ureido-propionate [238], as well as a variety of metabolites coming from or modulated by the human microbiome [100,117,239–244]. Other classes of metabolites not well represented in Recon2 are oxidised molecules [245] such as those caused by nonenzymatic reaction of metabolites with free radicals such as the hydroxyl radical generated by unliganded iron [246–250]. There is also significant interest in using methods of determining small molecules such as those in the metabolome (inter alia) for assessing the ‘exposome’ [251–255], in other words all the potentially polluting agents to which an individual has been exposed [256].

Recently discovered effects of metabolites on enzymes

Another combinatorial problem [61] reflects the fact that in molecular enzymology it is not normally realistic to assess every possible metabolite to determine whether it is an effector (i.e. activator or inhibitor) of the enzyme under study. Typical proteins are highly promiscuous [199,257,258] and there is increasing evidence for the comparative promiscuity of metabolites [259–261] and pharmaceutical drugs [26,39,199,262–271]. Certainly the contribution of individual small effects of multiple parameter changes can have substantial effects on the potential flux through an overall pathway [272], which makes ‘bottom up’ modelling an inexact science [273]. Even merely mimicking the in vivo (in Escherichia coli) concentrations of K+, Na+, Mg2+, phosphate, glutamate, sulphate and Cl− significantly modulated the activities of several enzymes tested relative to the ‘usual’ assay conditions [274]. Consequently, we need to be alive to the possibility of many (potentially major) interactions of which we are as yet ignorant. One class of example relates to the effects of the very widespread [275] post-translational modification on metabolic enzyme activities. Other recent examples include ‘unexpected’ effects of β-hydroxybutyrate on histone deacetylase [276], of serine on pyruvate kinase [277], of threonine on histone methylation and stem cell fate [278], of trehalose-6-phosphate on plant flowering time [279] and of lauroyl carnitine on macrophages [280].

In addition, some metabolites are known to affect drug transportation into cells; a well known example of this occurs with grapefruit [281–285], which contains naringin [286] that in humans is metabolised to naringenin [287]. As well as interacting with transporters to change absorption of drugs across the gut which modulates their bioavailability, these phytochemicals also inhibit various P450 activities and this can lead to prolonged and elevated drug levels; indeed several deaths have been linked to the consumption of grapefruit altering the concentration and/or bioavailability of a variety of pharmaceuticals.

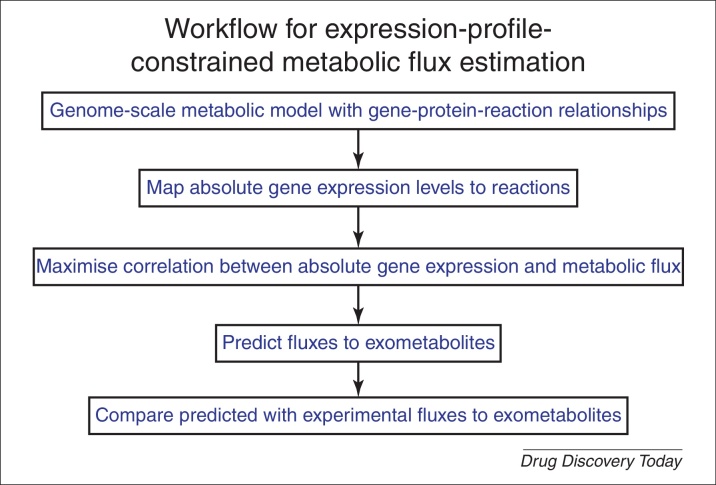

Constraint-based modelling of metabolic fluxes

Armed with the metabolic network models, it is possible to predict metabolic fluxes directly. This can be done in a ‘forward’ direction (as above; given the network, starting concentrations of enzymes and metabolites, and rate equations one can then predict the fluxes), in an ‘inverse’ direction (given the fluxes and concentrations one can try to predict the enzyme concentrations and kinetic parameters that would account for them [288–296]) or iteratively, using both kinds of knowledge. Historically, it has been common to use a ‘biomass’ term as a kind of dumping ground for uncertain fluxes. However, a recent and important discovery [297] (Fig. 4) is that a single transcriptome experiment, serving as a surrogate for fluxes through individual steps, provides a huge constraint on possible models, and predicts in a numerically tractable way and with much improved accuracy the fluxes to exometabolites without the need for such a variable ‘biomass’ term. Other recent and related strategies that exploit modern advances in ’omics and network biology to limit the search space in constraint-based metabolic modelling include references [137,151,298–306].

Figure 4.

The steps in a workflow that uses constraints based on (i) metabolic network stoichiometry and chemical reaction properties (both encoded in the model) plus, and (ii) absolute (RNA-Seq) transcript expression profiles to enable the accurate modelling of pathway and exometabolite fluxes. The full strategy and results are described in [297].

Improvements in methods for measuring metabolites

Since its modern beginnings [78,307–310], metabolomics is significantly seen as an analytical science, in that it depends on our ability to measure sensitively, precisely and accurately the concentrations of a multitude of chemically diverse metabolites. As such it is worth highlighting a few recent papers that have improved these abilities – mainly via improvements in chromatography–mass spectrometry [81,84,102,311–322] in terms of increased coverage [255,323–329], metabolite identification [316,330–341], flux and pathway analysis [65,301,342–354], long-term robustness [355,356], sensitivity [357–359], precision [315,358,360–364], discrimination [228,287,365–367], among others. It is clear from the above that many analytical approaches are used to measure metabolites and, in addition to the chemical diversity of metabolites, each metabolomics platform typically has different levels of sensitivity. NMR spectroscopy measures small molecules typically in the μm to high mm range, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) detects metabolites in the range from μm to mm and liquid chromatography (LC)–MS significantly lower in the nm to μm levels [368]. Sample preparation is also an important and sometimes overlooked component of the analysis [369,370], and can be based on predictable chemistry [371].

Novel methods of data analysis also remain very important [372,373], and some examples of these include metabolomics pipelines [374,375], peak alignment [376] and calibration transfer [377–379], between-metabolite relationships [380], metabolite time series comparisons [381], cross correlations [382], multiblock principal components [383] and partial least squares [384] analysis, metabolome databases [340,385–396], methods for mode-of-action discovery [365,397–401], data management [402,403] and standards [404,405], and statistical robustness [406,407].

Concluding remarks – the role of metabolomics in systems pharmacology

What is becoming increasingly clear, as we recognise that to understand living organisms in health and disease we must treat them as systems [96,149], is that we must bring together our knowledge of the topologies and kinetics of metabolic networks with our knowledge of the metabolite concentrations (i.e. metabolomes) and fluxes. Because of the huge constraints imposed on metabolism by reaction stoichiometries, mass conservation and thermodynamics, comparatively few well-chosen ’omics measurements might be needed to do this reliably [297] (Fig. 4). Indeed, a similar approach exploiting constraints has come to the fore in de novo protein folding and interaction studies [408–412].

What this leads us to in drug discovery is the need to develop and exploit a ‘systems pharmacology’ [18,30,32,40,45–47,149,156,413–429] where multiple binding targets are chosen purposely and simultaneously. Along with other measures such as phenotypic screening [8,430,431], and the integrating of the full suite of e-science approaches [44,131,405,432–439], one can anticipate considerable improvements in the rate of discovery of safe and effective drugs.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Antje Kell for drawing Fig. 3a and b.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Kola I., Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:711–715. doi: 10.1038/nrd1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeson P.D., Springthorpe B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:881–890. doi: 10.1038/nrd2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kola I. The state of innovation in drug development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;83:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul S.M. How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry's grand challenge. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:203–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessel M. The problems with today's pharmaceutical business-an outsider's view. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:27–33. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leeson P.D., St-Gallay S.A. The influence of the ‘organizational factor’ on compound quality in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:749–765. doi: 10.1038/nrd3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pammolli F. The productivity crisis in pharmaceutical R&D. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:428–438. doi: 10.1038/nrd3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swinney D.C., Anthony J. How were new medicines discovered? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:507–519. doi: 10.1038/nrd3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna I. Drug discovery in pharmaceutical industry: productivity challenges and trends. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:1088–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan P. Can the flow of medicines be improved? Fundamental pharmacokinetic and pharmacological principles toward improving Phase II survival. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scannell J.W. Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012;11:191–200. doi: 10.1038/nrd3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baxter K. An end to the myth: there is no drug development pipeline. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:171cm1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munos B.H. Pharmaceutical innovation gets a little help from new friends. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:168ed1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sams-Dodd F. Is poor research the cause of the declining productivity of the pharmaceutical industry? An industry in need of a paradigm shift. Drug Discov. Today. 2013;18:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidov E. Advancing drug discovery through systems biology. Drug Discov. Today. 2003;8:175–183. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butcher E.C. Systems biology in drug discovery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:1253–1259. doi: 10.1038/nbt1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sams-Dodd F. Target-based drug discovery: is something wrong? Drug Discov. Today. 2005;10:139–147. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Greef J., McBurney R.N. Rescuing drug discovery: in vivo systems pathology and systems pharmacology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nrd1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kell D.B. Metabolomics, modelling and machine learning in systems biology: towards an understanding of the languages of cells. The 2005 Theodor Bücher lecture. FEBS J. 2006;273:873–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kell D.B. Systems biology, metabolic modelling and metabolomics in drug discovery and development. Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11:1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hornberg J.J. Metabolic control analysis to identify optimal drug targets. Prog. Drug Res. 2007;64:171–189. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-7567-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitano H. A robustness-based approach to systems-oriented drug design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:202–210. doi: 10.1038/nrd2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sams-Dodd F. Research & market strategy: how choice of drug discovery approach can affect market position. Drug Discov. Today. 2007;12:314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmermann G.R. Multi-target therapeutics: when the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Drug Discov. Today. 2007;12:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henney A., Superti-Furga G. A network solution. Nature. 2008;455:730–731. doi: 10.1038/455730a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopkins A.L. Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:682–690. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehár J. Combination chemical genetics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:674–681. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janga S.C., Tzakos A. Structure and organization of drug-target networks: insights from genomic approaches for drug discovery. Mol. Biosyst. 2009;5:1536–1548. doi: 10.1039/B908147j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schadt E.E. A network view of disease and compound screening. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8:286–295. doi: 10.1038/nrd2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allerheiligen S.R. Next-generation model-based drug discovery and development: quantitative and systems pharmacology. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010;88:135–137. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arrell D.K., Terzic A. Network systems biology for drug discovery. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010;88:120–125. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berger S.I., Iyengar R. Role of systems pharmacology in understanding drug adverse events. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2010;3:129–135. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boran A.D.W., Iyengar R. Systems approaches to polypharmacology and drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2010;13:297–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dudley J.T. Drug discovery in a multidimensional world: systems, patterns, and networks. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2010;3:438–447. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pujol A. Unveiling the role of network and systems biology in drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2010;31:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao S.W., Li S. Network-based relating pharmacological and genomic spaces for drug target identification. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barabási A.L. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murabito E. A probabilistic approach to identify putative drug targets in biochemical networks. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2011;8:880–895. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Besnard J. Automated design of ligands to polypharmacological profiles. Nature. 2012;492:215–220. doi: 10.1038/nature11691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cucurull-Sanchez L. Relevance of systems pharmacology in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:665–670. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henney A.M. The promise and challenge of personalized medicine: aging populations, complex diseases, and unmet medical need. Croat. Med. J. 2012;53:207–210. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2012.53.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaeger S., Aloy P. From protein interaction networks to novel therapeutic strategies. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:529–537. doi: 10.1002/iub.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li C.Q. Characterizing the network of drugs and their affected metabolic subpathways. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wild D.J. Systems chemical biology and the Semantic Web: what they mean for the future of drug discovery research. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:469–474. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winter G.E. Systems-pharmacology dissection of a drug synergy in imatinib-resistant CML. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:905–912. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao S., Iyengar R. Systems pharmacology: network analysis to identify multiscale mechanisms of drug action. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012;52:505–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silverman E.K., Loscalzo J. Developing new drug treatments in the era of network medicine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;93:26–28. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kell D.B., Oliver S.G. Here is the evidence, now what is the hypothesis? The complementary roles of inductive and hypothesis-driven science in the post-genomic era. Bioessays. 2004;26:99–105. doi: 10.1002/bies.10385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elliott K.C. Epistemic and methodological iteration in scientific research. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 2012;43:376–382. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brenner S. Current Biology; 1997. Loose ends. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffin J.L. The Cinderella story of metabolic profiling: does metabolomics get to go to the functional genomics ball? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 2006;361:147–161. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patti G.J. Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kell D.B., Knowles J.D. The role of modeling in systems biology. In: Szallasi Z., editor. System Modeling in Cellular Biology: From Concepts to Nuts and Bolts. MIT Press; 2006. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kell D.B. The virtual human: towards a global systems biology of multiscale, distributed biochemical network models. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:689–695. doi: 10.1080/15216540701694252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kell D.B., Mendes P. The markup is the model: reasoning about systems biology models in the Semantic Web era. J. Theor. Biol. 2008;252:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klipp E., editor. Systems Biology in Practice: Concepts, Implementation and Clinical Application. Wiley/VCH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alon U., editor. An Introduction to Systems Biology: Design Principles of Biological Circuits. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palsson B.Ø., editor. Systems Biology: Properties of Reconstructed Networks. Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saltelli A., editor. Global Sensitivity Analysis: The Primer. WileyBlackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Small B.G. Efficient discovery of anti-inflammatory small molecule combinations using evolutionary computing. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:902–908. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kell D.B. Scientific discovery as a combinatorial optimisation problem: how best to navigate the landscape of possible experiments? Bioessays. 2012;34:236–244. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Otero J.M. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae microbial cell factories for succinic acid production. J. Biotechnol. 2007;131:S205. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park J.H. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of l-valine based on transcriptome analysis and in silico gene knockout simulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702609104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park J.H. Application of systems biology for bioprocess development. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rocha I. OptFlux: an open-source software platform for in silico metabolic engineering. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010;4:45. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Becker J. From zero to hero-design-based systems metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for l-lysine production. Metab. Eng. 2011;13:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee J.W. Systems metabolic engineering for chemicals and materials. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim I.K. A systems-level approach for metabolic engineering of yeast cell factories. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;12:228–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2011.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kacser H., Burns J.A. The control of flux. In: Davies D.D., editor. Vol. 27. Cambridge University Press; 1973. pp. 65–104. (Rate Control of Biological Processes. Symposium of the Society for Experimental Biology). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heinrich R., Rapoport T.A. A linear steady-state treatment of enzymatic chains. General properties, control and effector strength. Eur. J. Biochem. 1974;42:89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kell D.B., Westerhoff H.V. Metabolic control theory: its role in microbiology and biotechnology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1986;39:305–320. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fell D.A., editor. Understanding the Control of Metabolism. Portland Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heinrich R., Schuster S., editors. The Regulation of Cellular Systems. Chapman & Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goodacre R. Metabolomics by numbers: acquiring and understanding global metabolite data. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kell D.B. Metabolomics and systems biology: making sense of the soup. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brown M. A metabolome pipeline: from concept to data to knowledge. Metabolomics. 2005;1:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kell D.B. Metabolomic biomarkers: search, discovery and validation. Exp. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2007;7:329–333. doi: 10.1586/14737159.7.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raamsdonk L.M. A functional genomics strategy that uses metabolome data to reveal the phenotype of silent mutations. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:45–50. doi: 10.1038/83496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Harrigan G.G., Goodacre R., editors. Metabolic Profiling: Its Role in Biomarker Discovery and Gene Function Analysis. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kaddurah-Daouk R. Metabolomics: a global biochemical approach to drug response and disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008;48:653–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dunn W.B. Systems level studies of mammalian metabolomes: the roles of mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:387–426. doi: 10.1039/b906712b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Suhre K. A genome-wide association study of metabolic traits in human urine. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:565–569. doi: 10.1038/ng.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Suhre K. Human metabolic individuality in biomedical and pharmaceutical research. Nature. 2011;477:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nature10354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adamski J., Suhre K. Metabolomics platforms for genome wide association studies-linking the genome to the metabolome. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013;24:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beger R.D., Colatsky T. Metabolomics data and the biomarker qualification process. Metabolomics. 2012;8:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bu Q. Metabolomics: a revolution for novel cancer marker identification. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2012;15:266–275. doi: 10.2174/138620712799218563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Claudino W.M. Metabolomics in cancer: a bench-to-bedside intersection. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2012;84:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dessi A. Physiopathology of intrauterine growth retardation: from classic data to metabolomics. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(Suppl. 5):13–18. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.714639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fan L. Identification of metabolic biomarkers to diagnose epithelial ovarian cancer using a UPLC/QTOF/MS platform. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:473–479. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.648338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Friedrich N. Metabolomics in diabetes research. J. Endocrinol. 2012;215:29–42. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hasan N. Towards the identification of blood biomarkers for acute stroke in humans: a comprehensive systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012;74:230–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hassanein M. The state of molecular biomarkers for the early detection of lung cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2012;5:992–1006. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iskandar H.N., Ciorba M.A. Biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease: current practices and recent advances. Transl. Res. 2012;159:313–325. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Laborde C.M. Potential blood biomarkers for stroke. Exp. Rev. Proteomics. 2012;9:437–449. doi: 10.1586/epr.12.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mishur R.J., Rea S.L. Applications of mass spectrometry to metabolomics and metabonomics: detection of biomarkers of aging and of age-related diseases. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2012;31:70–95. doi: 10.1002/mas.20338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Orešič M. Obesity and psychotic disorders: uncovering common mechanisms through metabolomics. Dis. Model Mech. 2012;5:614–620. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Smolinska A. NMR and pattern recognition methods in metabolomics: from data acquisition to biomarker discovery: a review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;750:82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhang A. Saliva metabolomics opens door to biomarker discovery, disease diagnosis, and treatment. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012;168:1718–1727. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9891-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang A. Urine metabolomics. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2012;414:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Collino S. Clinical metabolomics paves the way towards future healthcare strategies. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;75:619–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fanos V. Metabolomics in neonatology: fact or fiction? Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;18:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Heather L.C. A practical guide to metabolomic profiling as a discovery tool for human heart disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013;55:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lu J. Metabolomics in human type 2 diabetes research. Front. Med. 2013;7:4–13. doi: 10.1007/s11684-013-0248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rasmiena A.A. Metabolomics and ischaemic heart disease. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2013;124:289–306. doi: 10.1042/CS20120268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Russell C. Application of genomics, proteomics and metabolomics in drug discovery, development and clinic. Ther. Deliv. 2013;4:395–413. doi: 10.4155/tde.13.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nelson D.E. Oscillations in NF-κB signalling control the dynamics of gene expression. Science. 2004;306:704–708. doi: 10.1126/science.1099962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ashall L. Pulsatile stimulation determines timing and specificity of NFkappa-B-dependent transcription. Science. 2009;324:242–246. doi: 10.1126/science.1164860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kim D.H. Raman chemical mapping reveals site of action of HIV protease inhibitors in HPV16 E6 expressing cervical carcinoma cells. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010;398:3051–3061. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Reyzer M.L. Direct analysis of drug candidates in tissue by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2003;38:1081–1092. doi: 10.1002/jms.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rubakhin S.S. Imaging mass spectrometry: fundamentals and applications to drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today. 2005;10:823–837. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Miura D. In situ metabolomic mass spectrometry imaging: recent advances and difficulties. J. Proteomics. 2012;75:5052–5060. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Armitage E.G. Imaging of metabolites using secondary ion mass spectrometry. Metabolomics. 2013;9:S102–S109. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Masyuko R. Correlated imaging – a grand challenge in chemical analysis. Analyst. 2013;138:1924–1939. doi: 10.1039/c3an36416j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Neri F.M. Heterogeneity in susceptible-infected-removed (SIR) epidemics on lattices. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2011;8:201–209. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mendes P. Metabolic channeling in organized enzyme systems: experiments and models. In: Brindle K.M., editor. Enzymology In Vivo. JAI Press; 1995. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ovádi J., Srere P.A. Macromolecular compartmentation and channeling. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2000;192:255–280. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60529-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Goodacre R. Metabolomics of a superorganism. J. Nutr. 2007;137:259S–266S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.259S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wharfe E.S. Monitoring the effects of chiral pharmaceuticals on aquatic microorganisms by metabolic fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:2075–2085. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02395-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Janjić V., Pržulj N. Biological function through network topology: a survey of the human diseasome. Brief. Funct. Genomics. 2012;11:522–532. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/els037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Michal G., editor. Biochemical Pathways: An Atlas of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Herrgård M.J. A consensus yeast metabolic network obtained from a community approach to systems biology. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1155–1160. doi: 10.1038/nbt1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.DeJongh M. Toward the automated generation of genome-scale metabolic networks in the SEED. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Henry C.S. High-throughput generation, optimization and analysis of genome-scale metabolic models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:977–982. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Swainston N. The SuBliMinaL Toolbox: automating steps in the reconstruction of metabolic networks. Integrative Bioinf. 2011;8:186. doi: 10.2390/biecoll-jib-2011-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Reyes R. Automation on the generation of genome-scale metabolic models. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:1295–1306. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Rolfsson Ó. Inferring the metabolism of human orphan metabolites from their metabolic network context affirms human gluconokinase activity. Biochem. J. 2013;449:427–435. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ananiadou S. Text mining and its potential applications in systems biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ananiadou S. Event extraction for systems biology by text mining the literature. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Nobata C. Mining metabolites: extracting the yeast metabolome from the literature. Metabolomics. 2011;7:94–101. doi: 10.1007/s11306-010-0251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Czarnecki J. A text-mining system for extracting metabolic reactions from full-text articles. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Williams A.J. Open PHACTS: semantic interoperability for drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:1188–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Liebermeister W., Klipp E. Bringing metabolic networks to life: convenience rate law and thermodynamic constraints. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2006;3:41. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-3-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Smallbone K. Something from nothing: bridging the gap between constraint-based and kinetic modelling. FEBS J. 2007;274:5576–5585. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pozo C. Steady-state global optimization of metabolic non-linear dynamic models through recasting into power-law canonical models. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011;5:137. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wilkinson D.J., editor. Stochastic Modelling for Systems Biology. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Dada J.O., Mendes P. Multi-scale modelling and simulation in systems biology. Integr. Biol. (Camb.) 2011;3:86–96. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00075b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Schmidt B.J. Mechanistic systems modeling to guide drug discovery and development. Drug Discov. Today. 2013;18:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hucka M. The systems biology markup language (SBML): a medium for representation and exchange of biochemical network models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:524–531. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Funahashi A. CellDesigner 3.5: a versatile modeling tool for biochemical networks. Proc. IEEE. 2008;96:1254–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hoops S. COPASI: a COmplex PAthway SImulator. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:3067–3074. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Dada J.O., Mendes P. Proc. Data Integration Life Sciences, Vol. 5647. 2009. Design and architecture of web services for simulation of biochemical systems; pp. 182–195. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Mendes P. Computational modeling of biochemical networks using COPASI. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;500:17–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-525-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kent E. Condor-COPASI: high-throughput computing for biochemical networks. BMC Syst. Biol. 2012;6:91. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Saito R. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:1069–1076. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Smoot M.E. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:431–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.von Dassow G. The segment polarity network is a robust development module. Nature. 2000;406:188–192. doi: 10.1038/35018085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kitano H. Biological robustness. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:826–837. doi: 10.1038/nrg1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Quinton-Tulloch M.J. Trade-off of dynamic fragility but not of robustness in metabolic pathways in silico. FEBS J. 2013;280:160–173. doi: 10.1111/febs.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kell D.B. Finding novel pharmaceuticals in the systems biology era using multiple effective drug targets, phenotypic screening, and knowledge of transporters: where drug discovery went wrong and how to fix it. FEBS J. 2013 doi: 10.1111/febs.12268. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Mo M.L. A genome-scale, constraint-based approach to systems biology of human metabolism. Mol. Biosyst. 2007;3:598–603. doi: 10.1039/b705597h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Terzer M. Genome-scale metabolic networks. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2009;1:285–297. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Kümmel A. Systematic assignment of thermodynamic constraints in metabolic network models. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:512. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Duarte N.C. Global reconstruction of the human metabolic network based on genomic and bibliomic data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:1777–1782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610772104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Ma H. The Edinburgh human metabolic network reconstruction and its functional analysis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:135. doi: 10.1038/msb4100177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Stobbe M.D. Critical assessment of human metabolic pathway databases: a stepping stone for future integration. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011;5:165. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Kolodkin A. Emergence of the silicon human and network targeting drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012;46:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Bordbar A., Palsson B.Ø. Using the reconstructed genome-scale human metabolic network to study physiology and pathology. J. Intern. Med. 2012;271:131–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Mardinoglu A., Nielsen J. Systems medicine and metabolic modelling. J. Intern. Med. 2012;271:142–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Thiele I. A community-driven global reconstruction of human metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:419–425. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Shlomi T. Network-based prediction of human tissue-specific metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Chang R.L. Drug off-target effects predicted using structural analysis in the context of a metabolic network model. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2010;6:e1000938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Hao T. Compartmentalization of the Edinburgh Human Metabolic Network. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:393. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Jerby L. Computational reconstruction of tissue-specific metabolic models: application to human liver metabolism. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010;6:401. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Folger O. Predicting selective drug targets in cancer through metabolic networks. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7:501. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Rolfsson O. The human metabolic reconstruction Recon 1 directs hypotheses of novel human metabolic functions. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011;5:155. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Agren R. Reconstruction of genome-scale active metabolic networks for 69 human cell types and 16 cancer types using INIT. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2012;8:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Hao T. The reconstruction and analysis of tissue specific human metabolic networks. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:663–670. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05369h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Holzhütter H.G. The virtual liver: a multidisciplinary, multilevel challenge for systems biology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2012;4:221–235. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Thiele I., Palsson B.Ø. Reconstruction annotation jamborees: a community approach to systems biology. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010;6:361. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Kuchaiev O. Topological network alignment uncovers biological function and phylogeny. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2010;7:1341–1354. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Kuchaiev O., Pržulj N. Integrative network alignment reveals large regions of global network similarity in yeast and human. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1390–1396. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Thiele I. A community effort towards a knowledge-base and mathematical model of the human pathogen Salmonella typhimurium LT2. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Attwood T.K. Utopia Documents: linking scholarly literature with research data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i568–i574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Courtot M. Controlled vocabularies and semantics in systems biology. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7:543. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Sahoo S. A compendium of inborn errors of metabolism mapped onto the human metabolic network. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:2545–2558. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25075f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Allen J.K. High-throughput characterisation of yeast mutants for functional genomics using metabolic footprinting. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:692–696. doi: 10.1038/nbt823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Kell D.B. Metabolic footprinting and systems biology: the medium is the message. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:557–565. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Çakır T. Flux balance analysis of a genome-scale yeast model constrained by exometabolomic data allows metabolic system identification of genetically different strains. Biotechnol. Prog. 2007;23:320–326. doi: 10.1021/bp060272r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Castrillo J.I. Growth control of the eukaryote cell: a systems biology study in yeast. J. Biol. 2007;6:4. doi: 10.1186/jbiol54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Pir P. Exometabolic and transcriptional response in relation to phenotype and gene copy number in respiration-related deletion mutants of S. cerevisiae. Yeast. 2008;25:661–672. doi: 10.1002/yea.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Sue T. An exometabolomics approach to monitoring microbial contamination in microalgal fermentation processes by using metabolic footprint analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:7605–7610. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00469-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Paczia N. Extensive exometabolome analysis reveals extended overflow metabolism in various microorganisms. Microb. Cell Fact. 2012;11:122. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Daley D.O. Global topology analysis of the Escherichia coli inner membrane proteome. Science. 2005;308:1321–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.1109730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Kim H. A global topology map of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae membrane proteome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:11142–11147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604075103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Dobson P.D. “Metabolite-likeness” as a criterion in the design and selection of pharmaceutical drug libraries. Drug Discov. Today. 2009;14:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Kouskoumvekaki I., Panagiotou G. Navigating the human metabolome for biomarker identification and design of pharmaceutical molecules. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/525497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Peironcely J.E. Understanding and classifying metabolite space and metabolite-likeness. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Fromm M.F. Prediction of transporter-mediated drug–drug interactions using endogenous compounds. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;92:546–548. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Al-Awqati Q. One hundred years of membrane permeability: does Overton still rule? Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:E201–E202. doi: 10.1038/70230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Dobson P.D., Kell D.B. Carrier-mediated cellular uptake of pharmaceutical drugs: an exception or the rule? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:205–220. doi: 10.1038/nrd2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Dobson P. Implications of the dominant role of cellular transporters in drug uptake. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009;9:163–184. doi: 10.2174/156802609787521616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Kell D.B., Dobson P.D. The cellular uptake of pharmaceutical drugs is mainly carrier-mediated and is thus an issue not so much of biophysics but of systems biology. In: M.G., Kettner C., editors. Proc. Int. Beilstein Symposium on Systems Chemistry. Logos Verlag; 2009. pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- 193.Giacomini K.M. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:215–236. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Fromm M.F., Kim R.B., editors. Drug Transporters. Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 195.Kell D.B. Pharmaceutical drug transport: the issues and the implications that it is essentially carrier-mediated only. Drug Discov. Today. 2011;16:704–714. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Lanthaler K. Genome-wide assessment of the carriers involved in the cellular uptake of drugs: a model system in yeast. BMC Biol. 2011;9:70. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Burckhardt G. Drug transport by organic anion transporters (OATs) Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;136:106–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Sissung T.M. Transporter pharmacogenetics: transporter polymorphisms affect normal physiology, diseases, and pharmacotherapy. Discov. Med. 2012;13:19–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Kell D.B. The promiscuous binding of pharmaceutical drugs and their transporter-mediated uptake into cells: what we (need to) know and how we can do so. Drug Discov. Today. 2013;18:218–239. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Kell D.B. On pheromones, social behaviour and the functions of secondary metabolism in bacteria. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1995;10:126–129. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(00)89013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201.Broadhurst D., Kell D.B. Statistical strategies for avoiding false discoveries in metabolomics and related experiments. Metabolomics. 2006;2:171–196. [Google Scholar]

- 202.Shi X. Identification of N-acetyltaurine as a novel metabolite of ethanol through metabolomics-guided biochemical analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:6336–6349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.312199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203.Chen J. Serum 27-nor-5beta-cholestane-3,7,12,24,25 pentol glucuronide discovered by metabolomics as potential diagnostic biomarker for epithelium ovarian cancer. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:2625–2632. doi: 10.1021/pr200173q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204.Budczies J. Remodeling of central metabolism in invasive breast cancer compared to normal breast tissue – a GC-TOFMS based metabolomics study. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:334. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 205.Sato Y. Identification of a new plasma biomarker of Alzheimer's disease using metabolomics technology. J. Lipid Res. 2012;53:567–576. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M022376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 206.Cracowski J.L. Independent association of urinary F2-isoprostanes with survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2012;142:869–876. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 207.Dromparis P., Michelakis E.D. F2-isoprostanes: an emerging pulmonary arterial hypertension biomarker and potential link to the metabolic theory of pulmonary arterial hypertension? Chest. 2012;142:816–820. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 208.Prasain J.K. Simultaneous quantification of F2-isoprostanes and prostaglandins in human urine by liquid chromatography tandem–mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B: Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2012;913/914:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 209.Webhofer C. Metabolite profiling of antidepressant drug action reveals novel drug targets beyond monoamine elevation. Transl. Psychiatry. 2011;1:e58. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 210.Auray-Blais C. Urinary globotriaosylsphingosine-related biomarkers for Fabry disease targeted by metabolomics. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:2745–2753. doi: 10.1021/ac203433e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 211.Dupont F.O. A metabolomic study reveals novel plasma lyso-Gb3 analogs as Fabry disease biomarkers. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20:280–288. doi: 10.2174/092986713804806685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 212.Sun L. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339:786–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1232458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 213.Wu J. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. 2013;339:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1229963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 214.Horgan R.P. Metabolic profiling uncovers a phenotypic signature of small for gestational age in early pregnancy. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:3660–3673. doi: 10.1021/pr2002897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 215.Pilz S. Low homoarginine concentration is a novel risk factor for heart disease. Heart. 2011;97:1222–1227. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.220731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 216.Pilz S. Low serum homoarginine is a novel risk factor for fatal strokes in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Stroke. 2011;42:1132–1134. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.603035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 217.Dang L. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 218.Kalinina J. Detection of “oncometabolite” 2-hydroxyglutarate by magnetic resonance analysis as a biomarker of IDH1/2 mutations in glioma. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2012;90:1161–1171. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0888-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 219.Jansson J. Metabolomics reveals metabolic biomarkers of Crohn's disease. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 220.Kumar B.S. Discovery of common urinary biomarkers for hepatotoxicity induced by carbon tetrachloride, acetaminophen and methotrexate by mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2012;32:505–520. doi: 10.1002/jat.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 221.Kim K.B. Potential metabolomic biomarkers for evaluation of adriamycin efficacy using a urinary (1) H-NMR spectroscopy. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jat.2778. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 222.Ito S. N-Methylnicotinamide is an endogenous probe for evaluation of drug–drug interactions involving multidrug and toxin extrusions (MATE1 and MATE2-K) Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;92:635–641. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 223.Lin H.S. Serum level and prognostic value of neopterin in patients after ischemic stroke. Clin. Biochem. 2012;45:1596–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.07.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 224.Yadav A.K. Association between serum neopterin and inflammatory activation in chronic kidney disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2012;2012:476979. doi: 10.1155/2012/476979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 225.Caruso R. Neopterin levels are independently associated with cardiac remodeling in patients with chronic heart failure. Clin. Biochem. 2013;46:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 226.Soga T. Differential metabolomics reveals ophthalmic acid as an oxidative stress biomarker indicating hepatic glutathione consumption. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:16768–16776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601876200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 227.Noga M.J. Metabolomics of cerebrospinal fluid reveals changes in the central nervous system metabolism in a rat model of multiple sclerosis. Metabolomics. 2012;8:253–263. doi: 10.1007/s11306-011-0306-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 228.Zhang T. Discrimination between malignant and benign ovarian tumors by plasma metabolomic profiling using ultra performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2012;413:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 229.Dunn W.B. Serum metabolomics reveals many novel metabolic markers of heart failure, including pseudouridine and 2-oxoglutarate. Metabolomics. 2007;3:413–426. [Google Scholar]

- 230.Synesiou E. 4-Pyridone-3-carboxamide-1-beta-d-ribonucleoside triphosphate (4PyTP), a novel NAD metabolite accumulating in erythrocytes of uremic children: a biomarker for a toxic NAD analogue in other tissues? Toxins. 2011;3:520–537. doi: 10.3390/toxins3060520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 231.Klein M. Identification in human urine and blood of a novel selenium metabolite, Se-methylselenoneine, a potential biomarker of metabolization in mammals of the naturally occurring selenoneine, by HPLC coupled to electrospray hybrid linear ion trap-orbital ion trap MS. Metallomics. 2011;3:513–520. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00060d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 232.Devireddy L.R. A mammalian siderophore synthesized by an enzyme with a bacterial homolog involved in enterobactin production. Cell. 2010;141:1006–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 233.Bao G. Iron traffics in circulation bound to a siderocalin (Ngal)-catechol complex. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:602–609. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 234.Correnti C. Siderocalin/Lcn2/NGAL/24p3 does not drive apoptosis through gentisic acid mediated iron withdrawal in hematopoietic cell lines. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 235.Dunn W.B. The metabolome of human placental tissue: investigation of first trimester tissue and changes related to preeclampsia in late pregnancy. Metabolomics. 2012;8:579–597. [Google Scholar]

- 236.Kenny L.C. Robust early pregnancy prediction of later preeclampsia using metabolomic biomarkers. Hypertension. 2010;56:741–749. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.157297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 237.Akira K. LC-NMR identification of a novel taurine-related metabolite observed in 1H NMR-based metabonomics of genetically hypertensive rats. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010;51:1091–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 238.Kumar B.S. Discovery of safety biomarkers for atorvastatin in rat urine using mass spectrometry based metabolomics combined with global and targeted approach. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2010;661:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 239.Li M. Symbiotic gut microbes modulate human metabolic phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:2117–2122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712038105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 240.Wikoff W.R. Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:3698–3703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812874106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 241.Zhao L., Shen J. Whole-body systems approaches for gut microbiota-targeted, preventive healthcare. J. Biotechnol. 2010;149:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 242.Wang Z. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 243.Bennett B.J. Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell Metab. 2013;17:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 244.Heinken A. Systems-level characterization of a host-microbe metabolic symbiosis in the mammalian gut. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:28–40. doi: 10.4161/gmic.22370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 245.Mattingly S.J. A carbonyl capture approach for profiling oxidized metabolites in cell extracts. Metabolomics. 2012;8:989–996. doi: 10.1007/s11306-011-0395-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 246.Hower V. A general map of iron metabolism and tissue-specific subnetworks. Mol. Biosyst. 2009;5:422–443. doi: 10.1039/b816714c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 247.Kell D.B. Iron behaving badly: inappropriate iron chelation as a major contributor to the aetiology of vascular and other progressive inflammatory and degenerative diseases. BMC Medical Genomics. 2009;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 248.Kell D.B. Towards a unifying, systems biology understanding of large-scale cellular death and destruction caused by poorly liganded iron: Parkinson's, Huntington's, Alzheimer's, prions, bactericides, chemical toxicology and others as examples. Arch. Toxicol. 2010;577:825–889. doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0577-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 249.Chifman J. The core control system of intracellular iron homeostasis: a mathematical model. J. Theor. Biol. 2012;300:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 250.Funke C. Genetics and iron in the systems biology of Parkinson's disease and some related disorders. Neurochem. Int. 2013;62:637–652. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 251.Rappaport S.M. Implications of the exposome for exposure science. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2011;21:5–9. doi: 10.1038/jes.2010.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 252.Athersuch T.J. The role of metabolomics in characterizing the human exposome. Bioanalysis. 2012;4:2207–2212. doi: 10.4155/bio.12.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 253.Rappaport S.M. Biomarkers intersect with the exposome. Biomarkers. 2012;17:483–489. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.691553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 254.Wild C.P. The exposome: from concept to utility. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012;41:24–32. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 255.Soltow Q.A. High-performance metabolic profiling with dual chromatography–Fourier-transform mass spectrometry (DC–FTMS) for study of the exposome. Metabolomics. 2013;9:S132–S143. doi: 10.1007/s11306-011-0332-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 256.Johnson C.H. Xenobiotic metabolomics: major impact on the metabolome. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012;52:37–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 257.Aharoni A. The ‘evolvability’ of promiscuous protein functions. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:73–76. doi: 10.1038/ng1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 258.Wellendorph P. Molecular pharmacology of promiscuous seven transmembrane receptors sensing organic nutrients. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;76:453–465. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 259.Li X. Extensive in vivo metabolite–protein interactions revealed by large-scale systematic analyses. Cell. 2010;143:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 260.Kell D.B. Metabolites do social networking. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:7–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 261.Li X., Snyder M. Metabolites as global regulators: a new view of protein regulation: systematic investigation of metabolite–protein interactions may help bridge the gap between genome-wide association studies and small molecule screening studies. Bioessays. 2011;33:485–489. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 262.Hopkins A.L. Can we rationally design promiscuous drugs? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 263.Paolini G.V. Global mapping of pharmacological space. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:805–815. doi: 10.1038/nbt1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 264.Uthayathas S. Versatile effects of sildenafil: recent pharmacological applications. Pharmacol. Rep. 2007;59:150–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 265.Hopkins A.L. Predicting promiscuity. Nature. 2009;462:167–168. doi: 10.1038/462167a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 266.Keiser M.J. Predicting new molecular targets for known drugs. Nature. 2009;462:175–181. doi: 10.1038/nature08506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 267.Mestres J. The topology of drug–target interaction networks: implicit dependence on drug properties and target families. Mol. Biosyst. 2009;5:1051–1057. doi: 10.1039/b905821b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 268.Lounkine E. Large-scale prediction and testing of drug activity on side-effect targets. Nature. 2012;486:361–367. doi: 10.1038/nature11159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 269.Pérez-Nueno V.I., Ritchie D.W. Identifying and characterizing promiscuous targets: implications for virtual screening. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2012;7:1–17. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.632406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 270.Peters J.U. Can we discover pharmacological promiscuity early in the drug discovery process? Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 271.Hu Y., Bajorath J. How promiscuous are pharmaceutically relevant compounds? A data-driven assessment. AAPS J. 2013;15:104–111. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9421-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 272.Pritchard L., Kell D.B. Schemes of flux control in a model of Saccharomyces cerevisiae glycolysis. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:3894–3904. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 273.van Eunen K. Testing biochemistry revisited: how in vivo metabolism can be understood from in vitro enzyme kinetics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]