Abstract

Three-dimensional organotypic culture using reconstituted basement membrane matrix Matrigel (rBM 3-D) is an indispensable tool to characterize morphogenesis of mammary epithelial cells and to elucidate the tumor-modulating actions of extracellular matrix (ECM). microRNAs (miRNAs) are a novel class of oncogenes and tumor suppressors. The majority of our current knowledge of miRNA expression and function in cancer cells is derived from monolayer 2-D culture on plastic substratum, which lacks consideration of the influence of ECM-mediated morphogenesis on miRNAs. In the present study, we compared the expression of miRNAs in rBM 3-D and 2-D cultures of the non-invasive MCF-7 and the invasive MDA-MB231 cells. Our findings revealed a profound difference in miRNA profiles between 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures within each cell type. Moreover, rBM 3-D culture exhibited greater discrimination in miRNA profiles between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells than 2-D culture. The disparate miRNA profiles correlated with distinct mass morphogenesis of MCF-7 and invasive stellate morphogenesis of MDA-MB231 cells in rBM 3-D culture. Supplementation of the tumor promoting type I collagen in rBM 3-D culture substantially altered the miRNA signature of mass morphologenesis of MCF-7 cells in rBM 3-D culture. Overexpression of the differentially expressed miR-200 family member miR429 in MDA-MB231 cells attenuated their invasive stellate morphogenesis in rBM 3-D culture. In summary, we provide the first miRNA signatures of morphogenesis of human breast cancer cells in rBM 3-D culture and warrant further utilization of rBM 3-D culture in investigation of miRNAs in breast cancer.

Keywords: microRNA, three-dimensional organotypic culture, extra-cellular matrix, breast cancer, morphogenesis

Introduction

The tumor microenvironment, a newly established crucial determinant in tumorigenesis, is composed of extracellular matrix (ECM), growth factors, and inflammatory cytokines that are produced by the co-evolved neoplastic epithelial cells and associated stromal cells (1,2). During acquisition of invasive and metastatic competence, cancer cells progress to lose differentiation response to basement membrane matrix (BM), such as a loss of epithelial cell apical-basolateral polarity (3). The three-dimensional organotypic culture using reconstituted basement membrane Matrigel (hereinafter referred to as rBM 3-D) provides an ideal platform to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that mediate the dysregulated morphogenesis during mammary tumorigenesis because rBM 3-D culture faithfully recapitulates many in vivo properties of mammary epithelial cells (4-7). Genome wide expression profiling of breast cancer in rBM 3-D culture has established gene expression signatures associated with distinct morphogenesis of breast cancer cell lines with diverse invasive and metastatic properties (8). The clinical significance of the gene expression profiles derived from rBM 3-D culture is confirmed in that the gene expression signature from rBM 3-D culture of breast cancer cells holds prognostic values for patients with breast cancer (9).

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that inhibit gene expression often via complementarity with its target sequences within the 3' untranslated region (3'-UTR) of mRNA (10). Profiling miRNAs in human cancer specimens and cell lines reveals a growing number of tumorigenic and tumor suppressive miRNAs (11). Among the tumor suppressive miRNAs, the let-7 family and miR-200 family are frequently silenced in cancer (12). The let-7 family suppresses tumor growth via targeting cell cycle regulators (CDC25A and CDK6), promoters of growth (RAS and c-myc), and early embryonic genes (HMGA2) (13-15). The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) via targeting two EMT mediators, E-box binding transcription factors ZEB1 and ZEB2, and thereby suppresses invasion and metastasis (16,17).

Despite the importance of rBM 3-D culture and miRNAs in the research of breast cancer, miRNAs have not been characterized in rBM 3-D culture of breast cancer cells. The present study is aimed to elucidate the biology of miRNAs in morphogenesis of breast cancer cells with diverse invasive and metastatic potentials in rBM 3-D culture.

Materials and methods

Reagents and plasmids

Matrigel was purchased from BD Biosciences (Rockville, MD). Cell culture grade type I collagen was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis MO). A human miR-429 expression retroviral vector was generated by inserting the human pre-miR-429 into the pMSCV-puro-GFP-miR backbone vector as we previously described (18). Alexa 594 conjugated filamentous actin (F-actin) binding phalloidin was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Cell culture and retroviral transduction

Two human breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 cells (N variant) and MDA-MB231 cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma) as previously described (19,20). Stable ectopical expression of miR-429 in MDA-MB231 cells was accomplished by retroviral transduction as we previously described (21). Briefly miR-429 expressing and its backbone control retroviral vectors were produced using 293T cells. MDA-MB231 cells were then infected with the retroviruses and the stable transductants were selected and maintained using puromycin containing culture medium.

rBM three dimensional organotypic culture

Overlay rBM 3-D culture was carried out as described (4). Briefly, MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells were seeded at 2×105 cells/well in a 6-well cell culture plate that was coated with Matrigel. DMEM culture medium was supplemented with 4% of Matrigel and fresh medium was fed every two days. In the selected rBM 3-D culture of MCF-7 cells, Col-1 (2 μg/ml) was added as described (22). The morphology of cell clusters was monitored for 12 days and recorded using an inverse phase contrast microscope equipped with a digital camera based on the time course of morphogenesis of mammary epithelial cells in rBM 3-D culture as established in the previous studies by Debnath et al (4,22). The cell morphogenesis was also visualized by staining for filamentous actin using Alexa 594 conjugated phalloidin followed by confocal fluorescent microscopy analysis on a Bio-Rad Radiance 2100 system (Hercules, CA), which is an established method to monitor morphogenesis of mammary epithelial cells (8).

RNA extraction and analysis of mRNA and miRNA expression

Total cell RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) from 2-D culture when the cells reached ~80% confluence and from rBM 3-D cultures on day 12 after the cells were seeded. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out to determine the expression of E-cadherin, vimentin, and ZEB2 as previously described (23,24). The expression of let-7c, and members of miR-200 family (miR-200c, miR-141, and miR-429) was meaured using TaqMan miRNA assays as we previously described (18). The gene expression was normalized to 36B4 for the protein coding genes and to U6 for the miRNAs, respectively. A fold change of each transcript was obtained by setting the values from the control group to one. All the measurements were repeated on the RNA samples collected from three independent experiments.

miRNA array analysis

LC Sciences (Houston, TX) provided the microRNA expression profiling service using μParaflo® technology and proprietary probe hybridization (Cy3 and Cy5 dendrimer dyes) that enables highly sensitive and specific direct detection of human based on Sanger Institute human miRbase version 14 (894 human miRNAs). The miRNA microarrays of each culture condition were carried out on the RNA samples collected from three independent experiments. As advised by the service provider, any miRNA with a fluorescent intensity value <100 in all of the compared groups was excluded in the analysis. Multi-array log2 transformation, normalization, t-test, and unsupervised hierarchy clustering analysis (average linkage and a Euclidean distance metric) were carried out using the geWorkbench genomic analysis software suite to identify the differentially expressed miRNAs between any two selected groups (http://www.geworkbench.org) (25). False discovery rate (FDR) was calculated using the significance analysis of micro-arrays suite (SAM) (26). The miRNAs that carried a >2-fold difference, P<0.01, and FDA<0.05 between any two compared groups were considered significantly differentially expressed between the two groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance in the values compared between any two selected groups was determined using the unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (Prizm Version 5). A P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Correlation of miRNA expression and morphogenesis of breast cancer cells

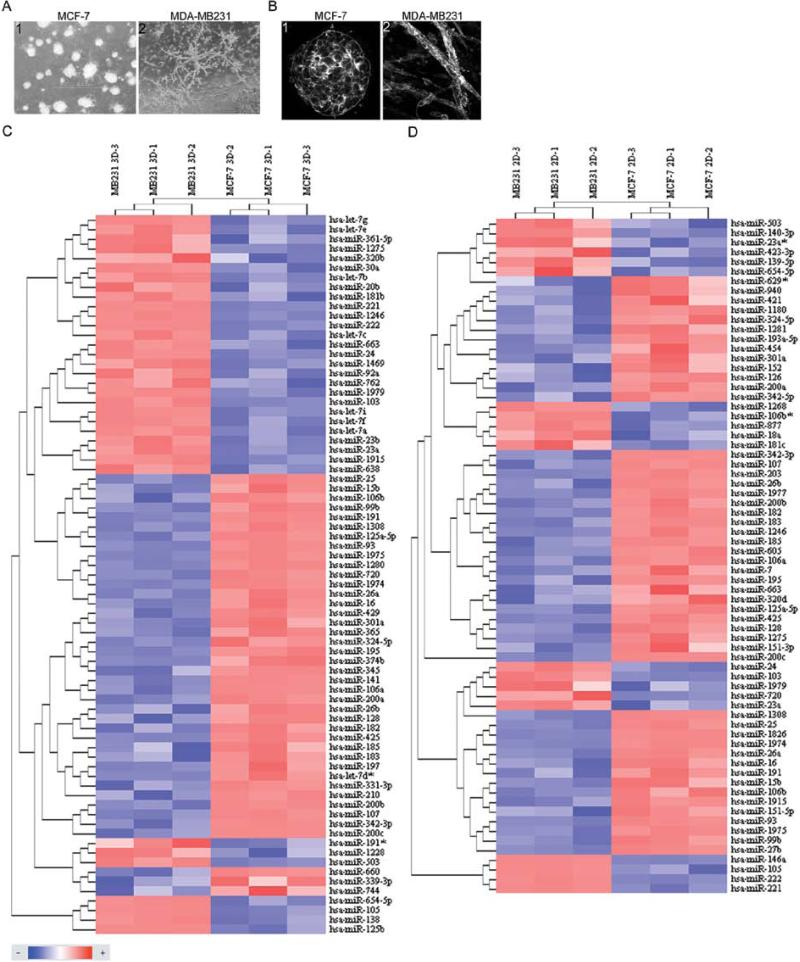

A recent study has uncovered gene expression profiles underlying distinct morphogenesis of breast cancer cell lines with diverse tumorigenic properties in rBM 3-D culture (8). Because miRNAs can modulate expression of the protein coding genes, we profiled miRNA expression underlying distinct morphogenesis of the non-invasive MCF-7 and the invasive MDA-MB231 cells in rBM 3-D culture. As revealed by inverse phase-contrast microscopy and fluorescent staining for F-actin, MCF-7 cells exhibited a mass morphology, a hallmark feature of non-invasive breast cancer cells that was defined by cell clusters with disorganized nuclei, robust cell-cell adhesion, and low frequency of formation of a central lumen (Fig. 1A1 and B1) (8). In contrast, MDA-MB231 exhibited an invasive stellate morphology, a hallmark feature of invasive breast cancer cells that was defined by disorganized nuclei and elongated cell body with prominent invasive projections that often bridge multiple cell colonies (Fig. 1A2 and B2) (8). In accordance, MCF-7 cells exhibited epithelial phenotype in 2-D culture, which included high expression of E-cadherin, an epithelial cell marker, and low expression of vimentin, a mesenchymal cell marker (data not shown). On the other hand, MDA-MB231 cells exhibited mesenchymal phenotype in 2-D culture, which included low expression of E-cadherin and high expression of vimentin (data not shown). The differential expression of E-cadherin and vimentin between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells was retained in rBM 3-D culture (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Distinct miRNA profiles of MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells in 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures. (A) MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells were cultured in rBM 3-D culture for 12 days. Morphogenesis was recorded using an inverse phase contrast microscope. Scale bars, 2.0 mm. (B) The cell colonies were visualized using fluorescent staining for F-actin. The images were representatives that were captured at the central planes of cell clusters using a confocal fluorescent microscope at magnification x200. The images of MDA-MB231 cells were parts of extensively networked cell growth. (C) Total cell RNA was extracted from MCF-7 and MDAMB231 cells in rBM 3-D culture. miRNA expression profiles were compared between the two cell lines using miRNA microarrays. A heatmap of significantly differentially expressed miRNAs and unsupervised hierarchial clustering were generated using geWorkbench suite (n=3, P<0.01, FDR<0.05). (D) Similar to (C) except that the miRNA array analysis was carried out on RNA samples collected from 2-D cultures of MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells.

To identify the miRNA candidates that discriminated mass and stellate morphogenesis we compared miRNA arrays in 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures of MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells. As expected, the miRNA expression profiles exhibited profound difference among diverse culture conditions. In rBM 3-D culture 75 miRNAs were differentially expressed between mass morphology of MCF-7 cells and stellate morphology of MDA-MB231 cells (Fig. 1C). Within this panel 61 miRNAs exhibited >2-fold differences between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells with 40 miRNAs being higher and 21 miRNAs being lower in MCF-7 over that MDA-MB231. In 2-D culture 70 miRNAs were differentially expressed between the epithelial phenotype of MCF-7 cells and the mesenchymal phenotype of MDA-MB231 cells (Fig. 1D). Within this panel 60 miRNAs exhibited >2-fold differences between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells with 45 being higher and 15 being lower in MCF-7 over MDA-MB231. Because this study was aimed to identify the miRNAs that discriminated mass and stellate morphologies, we identified 29 miRNAs whose expression differed between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells only in rBM 3-D culture (Table I). This panel of miRNAs featured a large number of miRNAs with known tumor modulating functions. For instance, two members of the tumor suppressive miR-200 family, miR-141 and miR-429 were higher in MCF-7 than that in MDA-MB231 cells (Table I) (16,17). Intriguingly, the tumor suppressive let-7 family in general exhibited a paradoxical lower expression in MCF-7 cells than that in MDA-MB231 cells (Table I) (13-15). Except for the miRNAs listed in Table I, the rest of the miRNAs in Fig. 1C were commonly differentially expressed between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells regardless of culture conditions, which featured higher expression of the tumor suppressive miR-200c and lower expression of the tumor promoting miR-221/222 cluster in MCF-7 cells than that in MDA-MB231 cells (16,17,27). These findings revealed a correlation between miRNA expression and morphogenesis of breast cancer cells in rBM 3-D culture.

Table I.

Disparate expression of miRNAs between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells in rBM 3-D culture.

| rBM 3D |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher | MCF-7/ MB231 | Lower | MCF-7/ MB231 |

| hsa-miR-141 | 52.323 | hsa-miR-125b | 0.002 |

| hsa-miR-429 | 11.685 | hsa-miR-1246 | 0.026 |

| hsa-miR-345 | 7.997 | hsa-miR-138 | 0.045 |

| hsa-miR-365 | 7.376 | hsa-let-7c | 0.061 |

| hsa-miR-374b | 7.102 | hsa-miR-181b | 0.116 |

| hsa-miR-210 | 5.325 | hsa-let-7g | 0.151 |

| hsa-miR-1280 | 4.545 | hsa-miR-30a | 0.167 |

| hsa-let-7d* | 4.280 | hsa-let-7a | 0.207 |

| hsa-miR-331-3p | 4.207 | hsa-let-7b | 0.232 |

| hsa-miR-660 | 3.065 | hsa-let-7i | 0.237 |

| hsa-miR-197 | 3.055 | hsa-let-7f | 0.239 |

| hsa-miR-720 | 2.936 | hsa-let-7e | 0.276 |

| hsa-miR-339-3p | 2.591 | hsa-miR-1275 | 0.456 |

| hsa-miR-744 | 2.139 | hsa-miR-24 | 0.466 |

| hsa-miR-1228 | 0.472 | ||

Total cell RNA was extracted from MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells in rBM 3-D culture. miRNA arrays were carried out and analyzed as described in Materials and methods. A fold change was obtained by setting the values from MDA-MB231 cells to one.

We speculated that a disparate response of miRNA expression during transition from 2-D to rBM 3-D culture in MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells gave rise to the rBM-3D-specific differential miRNAs between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells. Therefore, we compared the miRNA profiles between 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures within each cell type to identify the rBM 3-D responsive miRNAs. In MCF-7 cells 49 miRNAs were differentially expressed between rBM 3-D and 2-D cultures at a >2-fold difference with 24 miRNAs being higher and 25 miRNAs being lower in rBM 3-D than that in 2-D (Table II). In MDA-MB231 cells, 28 miRNAs were differentially expressed between 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures at a >2-fold difference with 22 miRNAs being higher and 6 miRNAs being lower in rBM 3-D than that in 2-D (Table III). Moreover, the majority of the rBM responsive miRNAs were unique to MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells except for only 9 rBM 3-D responsive miRNAs that were common to MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells (a comparison of Tables II and III, the miRNAs unique to each cell type were in bold format). The miRNAs showing differential response to rBM were likely the miRNAs that mediated mass and stellate morphology. This panel of miRNAs featured two members of miR-200 family, miR-141 and miR-429 that were induced in rBM 3-D culture only in MCF-7, but not MDA-MB231 cells.

Table II.

Disparate expression of miRNAs between 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures of MCF-7 cells.

| MCF-7 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher | rBM 3D/2D | Lower | rBM 3-D/2-D |

| hsa-miR-149* | 7.141 | hsa-miR-605 | 0.057 |

| hsa-miR-210 | 6.881 | hsa-let-7c | 0.079 |

| hsa-miR-762 | 5.065 | hsa-miR-7 | 0.081 |

| hsa-miR-548q | 4.732 | hsa-miR-1308 | 0.126 |

| hsa-miR-141 | 4.703 | hsa-let-7g | 0.165 |

| hsa-miR-1469 | 4.248 | hsa-let-7b | 0.166 |

| hsa-miR-331-3p | 4.001 | hsa-let-7e | 0.174 |

| hsa-miR-1260 | 3.645 | hsa-miR-181b | 0.187 |

| hsa-miR-200a | 3.375 | hsa-let-7f | 0.191 |

| hsa-miR-1915 | 3.321 | hsa-let-7a | 0.209 |

| hsa-miR-429 | 3.148 | hsa-miR-1246 | 0.262 |

| hsa-miR-365 | 3.135 | hsa-let-7i | 0.265 |

| hsa-miR-1908 | 2.729 | hsa-miR-1977 | 0.288 |

| hsa-miR-663 | 2.701 | hsa-miR-629 | 0.292 |

| hsa-miR-342-3p | 2.665 | hsa-miR-1228 | 0.299 |

| hsa-miR-150* | 2.509 | hsa-miR-203 | 0.307 |

| hsa-miR-1975 | 2.449 | hsa-let-7d | 0.327 |

| hsa-miR-132 | 2.445 | hsa-miR-877 | 0.410 |

| hsa-miR-425 | 2.414 | hsa-miR-342-5p | 0.444 |

| hsa-miR-222 | 2.180 | hsa-miR-1978 | 0.448 |

| hsa-miR-193a-3p | 2.176 | hsa-miR-1275 | 0.453 |

| hsa-miR-193b | 2.093 | hsa-miR-27b | 0.459 |

| hsa-miR-1280 | 2.073 | hsa-miR-940 | 0.481 |

| hsa-miR-22 | 2.007 | hsa-miR-21 | 0.484 |

| hsa-miR-183 | 0.495 | ||

Total cell RNA was extracted from MCF-7 cells in 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures. miRNA arrays were carried out and analyzed as described in Materials and methods. A fold change was obtained by setting the values from 2-D culture of MCF-7 cells to one. Bold indicates the miRNAs that differed between 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures only in MCF-7 cells, but not in MDA-MB231 cells.

Table III.

Disparate expression of miRNAs between 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures of MDA-MB231 cells.

| MDA-MB231 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher | rBM 3D/2D | Lower | rBM 3D/2D |

| hsa-miR-1246 | 83.234 | hsa-miR-1308 | 0.119 |

| hsa-miR-654-5p | 14.009 | hsa-miR-301a | 0.177 |

| hsa-miR-663 | 8.580 | hsa-miR-381 | 0.203 |

| hsa-miR-1469 | 8.121 | hsa-miR-140-3p | 0.309 |

| hsa-miR-1915 | 8.056 | hsa-miR-1280 | 0.407 |

| hsa-miR-762 | 7.972 | hsa-miR-18a | 0.468 |

| hsa-miR-149* | 7.650 | ||

| hsa-miR-1826 | 6.064 | ||

| hsa-miR-1908 | 5.710 | ||

| hsa-miR-575 | 4.718 | ||

| hsa-miR-1231 | 4.237 | ||

| hsa-miR-1975 | 4.107 | ||

| hsa-miR-1977 | 3.270 | ||

| hsa-miR-1978 | 3.219 | ||

| hsa-miR-638 | 3.137 | ||

| hsa-miR-1275 | 2.671 | ||

| hsa-miR-150* | 2.443 | ||

| hsa-miR-1974 | 2.423 | ||

| hsa-miR-1281 | 2.415 | ||

| hsa-miR-193a-5p | 2.371 | ||

| hsa-let-7g | 2.115 | ||

| hsa-miR-27b | 2.071 | ||

Total cell RNA was extracted from MDA-MB231 cells in 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures. miRNA arrays were carried out and analyzed as described in Materials and methods. A fold change was obtained by setting the values from 2-D culture of MDA-MB231 cells to one. Bold indicates the miRNAs that differed between 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures only in MDA-MB231 cells, but not in MCF-7 cells.

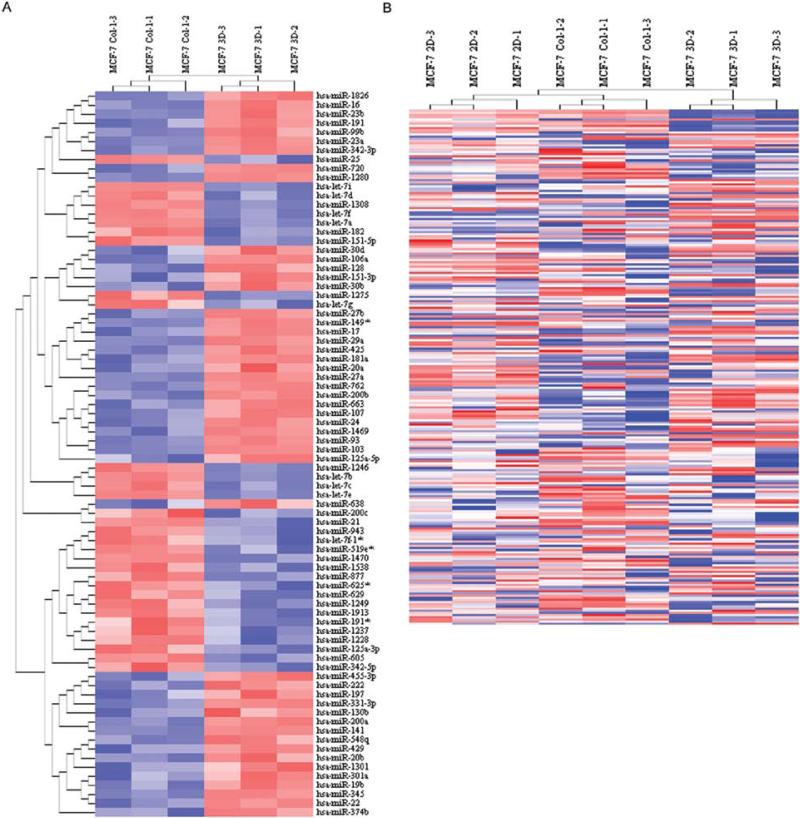

Dysregulation of miRNA expression by Col-1 in rBM 3-D culture of MCF-7 cells

The tumor-promoting Col-1 is able to disrupt acinar and mass morphogenesis of mammary epithelial cells in rBM 3-D culture and promote progression of mammary tumorigenesis in mouse models (22,24,28). Therefore, we questioned whether Col-1 dysregulated the expression of miRNAs of MCF-7 cells in rBM 3-D. We compared the miRNA profiles of MCF-7 cells in rBM 3-D and rBM 3-D+Col-1. Col-1 altered the expression of 80 miRNAs (Fig. 2A). Within this panel, 61 miRNAs exhibited >2-fold differences between rBM 3-D and rBM 3-D+Col-1 with 25 miRNAs being up-regulated and 36 miRNAs being down-regulated by Col-1 (Table IV). Because Col-1 disrupted acinar/mass morphogenesis of MCF-7 cells, we then questioned whether Col-1 dysregulated the expression of the MCF-7-specific rBM responsive miRNAs that were potential miRNA mediators of mass morphogenesis of MCF-7 cells in rBM 3-D culture (Table II, indicated by bold). Indeed, the expression of 23 MCF-7-specific rBM responsive miRNAs was dysregulated by Col-1 because the expression profile of these miRNAs was shifted towards the expression profile in 2-D culture (Table IV, indicated by bold). This panel of miRNAs featured a decreased expression of 3 members of the miR-200 family, miR-200a, miR-141, and miR-429, and an increased expression of 8 members of the let-7 family (Table IV). This trend was further supported by clustering analysis of miRNA arrays of 2-D, rBM 3-D, and rBM 3-D+Col-1 cultures in that the miRNA profile of rBM 3-D+Col-1 was clustered more proximal to the miRNA profile of 2-D than to that of rBM 3-D (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Dysregulated expression of miRNAs by Col-1 in rBM 3-D of MCF-7 cells. (A) Total cell RNA was extracted from MCF-7 rBM 3-D culture with or without supplementation of Col-1 (2 μg/ml). miRNA expression profiles were compared between the two culture conditions using miRNA microarrays. A heatmap of significantly differentially expressed miRNAs and unsupervised hierarchial clustering were generated using geWorkbench suite (n=3, P<0.01, FDR<0.05). (B) An unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis was carried out to group and visualize miRNA arrays from MCF-7 cells in 2-D, rBM 3-D, and rBM 3-D+Col-1 cultures according to the expression profiles of miRNAs in each culture condition.

Table IV.

Disparate expression of miRNAs between rBM and rBM+Col-1 3-D cultures of MCF-7 cells.

| MCF-7 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher | rBM+Col-1/rBM | Lower | rBM+Col-1/rBM |

| hsa-let-7b | 10.896 | hsa-miR-141 | 0.086 |

| hsa-let-7e | 10.717 | hsa-miR-374b | 0.105 |

| hsa-miR-605 | 10.174 | hsa-miR-1280 | 0.122 |

| hsa-let-7c | 10.142 | hsa-miR-27a | 0.140 |

| hsa-miR-1246 | 9.438 | hsa-miR-19b | 0.149 |

| hsa-miR-1538 | 7.337 | hsa-miR-200a | 0.152 |

| hsa-let-7a | 5.723 | hsa-miR-301a | 0.192 |

| hsa-let-7f | 5.347 | hsa-miR-29a | 0.195 |

| hsa-miR-1470 | 5.220 | hsa-miR-429 | 0.209 |

| hsa-let-7f-1* | 4.636 | hsa-miR-22 | 0.221 |

| hsa-miR-943 | 4.355 | hsa-miR-30b | 0.222 |

| hsa-miR-1913 | 3.927 | hsa-miR-149* | 0.229 |

| hsa-miR-625* | 3.764 | hsa-miR-720 | 0.232 |

| hsa-let-7i | 3.676 | hsa-miR-331-3p | 0.250 |

| hsa-miR-519e* | 3.516 | hsa-miR-548q | 0.253 |

| hsa-let-7d | 3.256 | hsa-miR-345 | 0.270 |

| hsa-miR-342-5p | 3.179 | hsa-miR-762 | 0.278 |

| hsa-miR-125a-3p | 2.944 | hsa-miR-27b | 0.323 |

| hsa-let-7g | 2.918 | hsa-miR-106a | 0.342 |

| hsa-miR-629 | 2.885 | hsa-miR-200b | 0.354 |

| hsa-miR-877 | 2.855 | hsa-miR-17 | 0.362 |

| hsa-miR-1249 | 2.642 | hsa-miR-222 | 0.372 |

| hsa-miR-1237 | 2.533 | hsa-miR-342-3p | 0.376 |

| hsa-miR-21 | 2.365 | hsa-miR-103 | 0.381 |

| hsa-miR-1308 | 2.211 | hsa-miR-181a | 0.383 |

| hsa-miR-107 | 0.394 | ||

| hsa-miR-455-3p | 0.411 | ||

| hsa-miR-1301 | 0.421 | ||

| hsa-miR-663 | 0.442 | ||

| hsa-miR-93 | 0.443 | ||

| hsa-miR-23a | 0.451 | ||

| hsa-miR-425 | 0.459 | ||

| hsa-miR-30d | 0.464 | ||

| hsa-miR-197 | 0.466 | ||

| hsa-miR-20b | 0.482 | ||

| hsa-miR-1469 | 0.496 | ||

Total cell RNA was extracted from MCF-7 cells rBM and rBM+Col-1 3-D cultures. miRNA arrays were carried out and analyzed as described in Materials and methods. A fold change was obtained by setting the values from rBM 3-D culture to one. Bold indicates the miRNAs that commonly differed in comparison between 2-D vs. rBM 3-D and rBM 3-D vs. rBM+Col-1 3-D cultures.

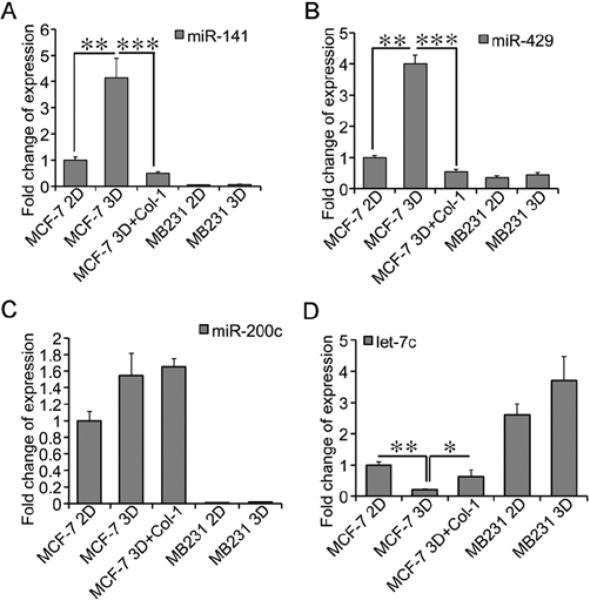

Validated expression of the differential miRNAs between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231

Because the expression of the members of the miR-200 and let-7 families differed substantially between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells in rBM 3-D culture, and was dysregulated by Col-1 in MCF-7 cells, we validated the expression of these miRNA in all culture conditions individually by qRT-PCR. Consistent with the results from miRNA arrays, the induction of miR-141 and miR-429 upon transition from 2-D to rBM 3-D culture were observed only in MCF-7 cells, but not in MDA-MB231 cells (Fig. 3A and B). Moreover, Col-1 abolished the induction of miR-141 and mR-429 in rBM 3-D culture of MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3A and B). On the other hand, the expression of miR-200c was consistently higher in MCF-7 cells than that in MDA-MB231 regardless of the culture conditions (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the miRNA array data, let-7c was repressed upon transition from 2-D to rBM 3-D culture only in MCF-7 cells, but not in MDA-MB231 cells (Fig. 3D). Col-1 increased the expression of let-7c in rBM 3-D culture of MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3D). Overall, these results confirm a correlation between miRNA expression profiles and morphogenesis of breast cancer cells in rBM 3-D culture.

Figure 3.

Differential expression of miRNAs among 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures. (A) The expression of miR-141 was measured using qRT-PCR in total cell RNA collected from 2-D, rBM 3-D, and rBM 3-D+Col-1 cultures of MCF-7 cells and MDA-MB231 cells. A fold change in miR-141 was obtained by setting the values of miR-141 from MCF-7 cells in 2-D culture to one and normalization to the values of U6. (B) Similar to (A) except that the expression of miR-429 was compared across the groups. (C) Similar to (A) except that the expression of miR-200c was compared across the groups. (D) Similar to (A) except that the expression of let-7c was compared across the groups. The data are presented in averages and standard deviations obtained from three independent experiments. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; and ***P<0.001.

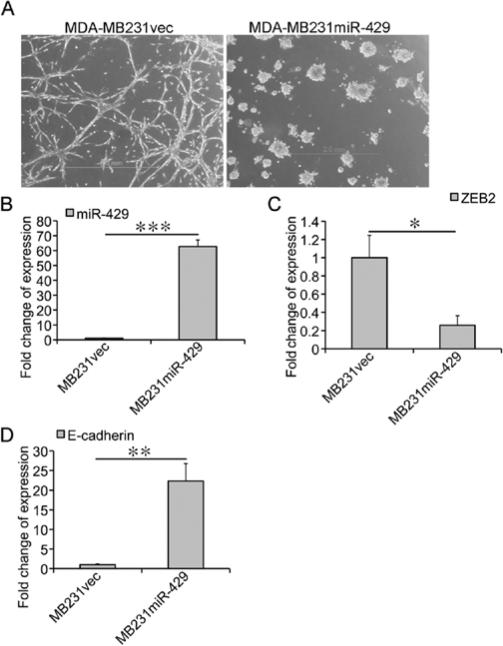

miR-429-mediated attenuation of the invasive stellate morphogenesis of MDA-MB231 cells

To determine the role of miRNAs in morphogenesis of breast cancer cells in rBM 3-D culture, we focused on miR-429 because its expression was high in mass morphogenesis and low in Col-1-disrupted mass morpho-genesis of MCF-7 cells, and low in stellate morphogenesis of MDA-MB231 cells (Fig. 3B). We chose to determine whether over-expression of miR-429 in MDA-MB231 cells could attenuate stellate morphogenesis and promote mass morphogenesis. We reasoned that knockdown of miR-429 alone in MCF-7 cells may not be sufficient to disrupt mass morphogenesis because other members of miR-200 family, such as miR-141 can compensate a loss of miR-429 in morphogenesis. To this end, we generated MDA-MB231 variants that were transduced with either a backbone vector (MDA-MB231vec) or a miR-429 expressing vector (MDA-MB231miR-429). We compared morphogenesis between MDA-MB231vec and MDA-MB231miR-429 cells in rBM 3-D culture. As expected, MDA-MB231miR-429 exhibited a loss of the invasive stellate morphology and acquisition of mass morphology that resembled MCF-7 cells, whereas MDA-MB231vec retained a stellate morphology that was indistinguishable from the parental MDA-MB231 (Fig. 4A). Overexpression of miR-429 was confirmed as MDA-MB231miR-429 exhibited a 62-fold increase in RNA levels of miR-429 over that in MDA-MB231vec (Fig. 4B). As a consequence, overexpression of miR-429 repressed its target ZEB2 in MDA-MB231miR-429 to 26% of the control group (Fig. 4C) and induced the expression of E-cadherin, a ZEB2 repressed gene, to a 22-fold increase over that in MDA-MB231vec (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that miRNAs are crucial regulators of morphogenesis of breast cancer cells in rBM 3-D culture.

Figure 4.

Attenuation of the stellate morphology of MDA-MB231 by overexpression of miR-429. (A) MDA-MB231vec and MDA-MB231miR-429 cells were cultured in rBM 3-D culture for 12 days. The growth pattern was recorded using an inverse phase contrast microscope. Scale bars, 2.0 mm. (B) The expression of miR-429 was measured using qRT-PCR in total cell RNA collected from rBM 3-D cultures of MDA-MB231vec and MDA-MB231miR-429 cells. A fold change in miR-429 was obtained by setting the values of miR-429 from MDA-MB231vec cells to one and normalization to the values of U6. (C) Similar to (B) except that the mRNA levels of ZEB2 were compared between MDA-MB231vec and MDA-MB231miR-429 cells. (D) Similar to (B) except that the mRNA levels of E-cadherin were compared between MDA-MB231vec and MDA-MB231miR-429 cell. The data are presented in average and standard deviations obtained from three independent experiments. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; and ***P<0.001.

Discussion

A recent gene expression profiling of breast cancer cell lines in rBM 3-D culture identifies the gene expression signatures of untranformed and transformed mammary epithelial cell lines displaying distinct morphogenesis (8). Using a similar strategy, we identify the miRNA expression profiles correlating with mass morphology of MCF-7 and stellate morphology of MDA-MB231 cells in rBM 3-D culture. The identified miRNA profiles lend further support to the concept that rBM 3-D culture provides unique and complementary information to morphogenesis and tumorigenesis of mammary epithelial cells (7,8).

In our comparison of the miRNA profiles between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells, a considerable portion of the differentially expressed miRNAs between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells are common to both 2-D and rBM 3-D cultures (Fig. 1A and B). These miRNAs reflect disparate tumorigenic properties of the two cell lines. For instance, the tumor-promoting miR211-222 cluster is robustly expressed in MDA-MB231 cells and nearly silenced in MCF-7 cells (27). On the other hand, rBM 3-D culture uncovers unique difference between MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 in the expression of miRNAs. This phenomenon appears to result from distinct miRNA response upon transition from 2-D to rBM 3-D culture (Tables II and III). Because rBM 3-D culture promotes differentiation of mammary epithelial cells, a reduced miRNA response of MDA-MB231 relative to MCF-7 implicates that the less aggressive MCF-7 is more responsive to the differentiation-promoting cues derived from rBM 3-D than MDA-MB231 (Table II vs. Table III) (5). This is also congruent to their distinct morphology in rBM 3-D culture. MCF-7 exhibit mass morphology that is characteristic of non-invasive and non-metastatic breast cancer cells, whereas MDA-MB231 cells display stellate morphology that is characteristic of invasive and metastatic breast cancer cells (8).

The MCF-7-specific rBM responsive miRNAs feature increased expression of 3 members of the miR-200 family, miR-200a, miR-141, and miR-429 (Table II and Fig. 3). Because the miR-200 family is one of the most potent suppressors of EMT, these findings suggest a role of the EMT regulators in morpho-genesis of breast cancer cells in rBM 3-D culture. In support of this speculation, robust expression of the miR-200 family members in MCF-7 correlates with the mass morphology that features strong cell-cell adhesion (8). In contrast, the silenced expression of miR-200 family members in MDA-MB231 correlates with the stellate morphology that features disorganized elongated cell clusters with invasive processes in the absence of strong cell-cell adhesion (8). This can be attributed to a loss of ZEB1/2-mediated repression of E-cadherin by robust expression of the miR-200 family in MCF-7 cells, which provides sufficient E-cadherin for strong cell-cell adhesion. These findings also suggest that native BM inhibits EMT and tumor progression via up-regulation of the miR-200 family, and the consequent suppression of the EMT promoter ZEB2. The function of the miR-200 family in morphogenesis is further supported by over-expression of miR-429 in MDA-MB231 cells. Over-expression of miR-429 inhibits the expression of the EMT promoter ZEB2, releases ZEB2-mediated suppression of E-cadherin, and converts the stellate morphology of MDA-MB231 to a mass-like morphology in rBM 3-D culture (Fig. 4). The importance of the rBM responsive miRNAs in morphogenesis is further supported by a comparison of miRNA profiles between rBM 3-D and rBM+Col-1 3-D culture of MCF-7 cells. Col-1 dysregulates the expression of the rBM responsive miRNAs, particularly the miR-200 family, which correlates with disruption of mass morphogenesis of MCF-7 cells (Table IV) (24).

It is noteworthy that the tumor suppressive let-7 miRNA family exhibits a paradoxical decrease in rBM 3-D relative to 2-D culture in MCF-7 and this response is absent in MDA-MB231 (Fig. 3B). One plausible explanation of this apparent paradoxical observation is that the expression of let-7 family miRNAs is stimulated in response to tumorigenic cues as a cell defense mechanism and repressed by the rBM derived differentiation-promoting signals. Thus, the decreased expression of the let-7 family indicates that sensing the rBM-derived differentiation promoting cues is intact only in MCF-7 cells, but not in MDA-MB231 cells. A comprehensive functional analysis of the rBM responsive miRNAs in mammary epithelial cells will yield novel insight into how miRNAs regulate mammary epithelial morphogenesis and tumorigenesis.

In conclusion, the present study provides an initial characterization of miRNA expression that correlates with distinct morphogenesis of breast cancer cell lines in rBM 3-D culture. Our findings strengthen the utility of rBM 3-D culture in elucidating the role of miRNAs in morphogenesis and tumorigenesis of mammary epithelial cells.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by DOD BC085516 awarded to B. Shan. H.T. Nguyen is supported in part by Developmental Funds of the Tulane Cancer Center. geWorkbench is a free open source genomic analysis platform developed at Columbia University with funding from the NIH Roadmap Initiative (1U54CA121852-01A1) and the National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- BM

basement membrane matrix

- rBM 3-D

reconstituted basement membrane matrix based three-dimensional organotypic culture

- Col-1

type I collagen

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- miRNA

microRNA

- F-actin

filamentous actin

- qRT-PCR

quantitative RT-PCR

References

- 1.Bissell MJ, Radisky D. Putting tumours in context. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:46–54. doi: 10.1038/35094059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weigelt B, Bissell MJ. Unraveling the microenvironmental influences on the normal mammary gland and breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods. 2003;30:256–268. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hebner C, Weaver VM, Debnath J. Modeling morphogenesis and oncogenesis in three-dimensional breast epithelial cultures. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:313–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee GY, Kenny PA, Lee EH, Bissell MJ. Three-dimensional culture models of normal and malignant breast epithelial cells. Nat Methods. 2007;4:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargo-Gogola T, Rosen JM. Modelling breast cancer: one size does not fit all. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:659–672. doi: 10.1038/nrc2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenny PA, Lee GY, Myers CA, et al. The morphologies of breast cancer cell lines in three-dimensional assays correlate with their profiles of gene expression. Mol Oncol. 2007;1:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin KJ, Patrick DR, Bissell MJ, Fournier MV. Prognostic breast cancer signature identified from 3D culture model accurately predicts clinical outcome across independent datasets. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trang P, Weidhaas JB, Slack FJ. MicroRNAs as potential cancer therapeutics. Oncogene. 2008;27(Suppl 2):S52–S57. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verghese ET, Hanby AM, Speirs V, Hughes TA. Small is beautiful: microRNAs and breast cancer-where are we now? J Pathol. 2008;215:214–221. doi: 10.1002/path.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peter ME. Let-7 and miR-200 microRNAs: guardians against pluripotency and cancer progression. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:843–852. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.6.7907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampson VB, Rong NH, Han J, et al. MicroRNA let-7a down-regulates MYC and reverts MYC-induced growth in Burkitt lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9762–9770. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayr C, Hemann MT, Bartel DP. Disrupting the pairing between let-7 and Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation. Science. 2007;315:1576–1579. doi: 10.1126/science.1137999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, et al. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:593–601. doi: 10.1038/ncb1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park SM, Gaur AB, Lengyel E, Peter ME. The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes Dev. 2008;22:894–907. doi: 10.1101/gad.1640608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin Z, Wang X, Fewell C, Cameron J, Yin Q, Flemington EK. Differential expression of the miR-200 family microRNAs in epithelial and B cells and regulation of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation by the miR-200 family member miR-429. J Virol. 2010;84:7892–7897. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00379-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burow ME, Weldon CB, Tang Y, et al. Differences in susceptibility to tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis among MCF-7 breast cancer cell variants. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4940–4946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burow ME, Weldon CB, Chiang TC, et al. Differences in protein kinase C and estrogen receptor alpha, beta expression and signaling correlate with apoptotic sensitivity of MCF-7 breast cancer cell variants. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:1179–1187. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.6.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shan B, Morris CA, Zhuo Y, Shelby BD, Levy DR, Lasky JA. Activation of proMMP-2 and Src by HHV8 vGPCR in human pulmonary arterial endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:517–525. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shan B, Yao TP, Nguyen HT, et al. Requirement of HDAC6 for transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21065–21073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802786200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Nguyen HT, Zhuang Y, et al. Post-transcriptional up-regulation of miR-21 by type I collagen. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50:563–570. doi: 10.1002/mc.20742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Floratos A, Smith K, Ji Z, Watkinson J, Califano A. geWork-bench: an open source platform for integrative genomics. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1779–1780. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao X, Di Leva G, Li M, et al. MicroRNA-221/222 confers breast cancer fulvestrant resistance by regulating multiple signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2010;30:1082–1097. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]