Abstract

The mammalian ABL1 gene encodes the ubiquitously expressed nonreceptor tyrosine kinase ABL. In response to growth factors, cytokines, cell adhesion, DNA damage, oxidative stress, and other signals, ABL is activated to stimulate cell proliferation or differentiation, survival or death, retraction, or migration. ABL also regulates specialized functions such as antigen receptor signaling in lymphocytes, synapse formation in neurons, and bacterial adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells. Although discovered as the proto-oncogene from which the Abelson leukemia virus derived its Gag–v-Abl oncogene, recent results have linked ABL kinase activation to neuronal degeneration. This body of knowledge on ABL seems confusing because it does not fit the one-gene-one-function paradigm. Without question, ABL capabilities are encoded by its gene sequence and that molecular blueprint designs this kinase to be regulated by subcellular location-dependent interactions with inhibitors and substrate activators. Furthermore, ABL shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm where it binds DNA and actin—two biopolymers with fundamental roles in almost all biological processes. Taken together, the cumulated results from analyses of ABL structure-function, ABL mutant mouse phenotypes, and ABL substrates suggest that this tyrosine kinase does not have its own agenda but that, instead, it has evolved to serve a variety of tissue-specific and context-dependent biological functions.

INTRODUCTION

Searching PubMed with “ABL” retrieved >21,000 articles as of early January 2014. The majority of those articles focused on BCR-ABL, which is a constitutively activated oncogenic tyrosine kinase in human chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia (Ph+ ALL). Because ABL was discovered as the cellular proto-oncogene from which the Gag–v-Abl oncogene of the Abelson murine leukemia virus originated and because the Ph+ chromosomal translation generates the BCR-ABL oncoprotein, the initial interest in ABL was focused on its oncogenic potential. For discussions on BCR-ABL and ABL in the context of cancer, please refer to two recent reviews (1, 2). The early hypothesis that the oncogenic function of BCR-ABL and Gag–v-Abl is nothing but a supercharged ABL function is too simplistic, as BCR and Gag fusion to N-terminally deleted ABL both adds and alters functions. The focus of this minireview is on the biological functions of the mammalian ABL tyrosine kinase, which does not cause leukemia even when it is overexpressed.

ABL FUNDAMENTALS

Functional domains.

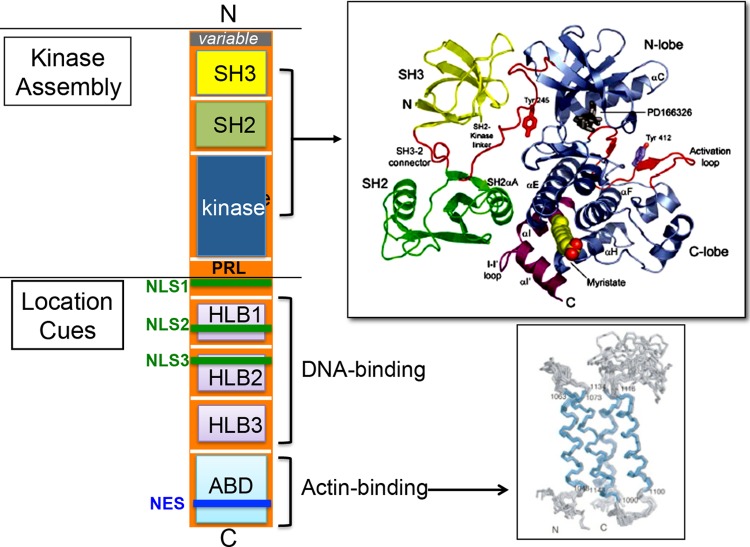

The ABL gene is found in all metazoans (1). The N-terminal SH3, SH2, and kinase domains and the C-terminal actin-binding domain (ABD) (3, 4) are conserved in the vertebrate and the invertebrate ABL genes (Fig. 1). The vertebrate genomes also contain a related ARG gene. The ABL (Abl1) and ARG (Abl2) genes are again highly conserved in the N-terminal kinase domain and the C-terminal ABD but less well conserved in the middle region (1). The crystal structure of the SH3-SH2-kinase assembly (5) and the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of the actin-binding domain (ABD) (6) have been elucidated (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Schematic diagram of ABL domains and structures. N, N terminal; variable, alternative promoter and 5′ exon encode two ABL variants, type Ia/b (human) and type I/IV (mouse); SH3, Src homology 3 domain (yellow); SH2, Src homology 2 domain (green); kinase, kinase domain (blue). The crystal structure of the SH3-SH2-kinase assembly with a small molecular inhibitor (PD166316) bound to the kinase N-lobe and a myristate inserted into the kinase C-lobe was solved by Nagar et al. (5). A proline-rich linker (PRL) containing binding sites for the SH3 domains of several substrates such as CRK and NCK is found immediately C terminal to the kinase domain, but this PRL is not included in the crystal structure. NLS, nuclear localization signal; NES, nuclear export signal; HLB, HMG-like box; ABD, actin binding domain. The NMR structure of the ABD has also been solved (6).

NLS.

Besides the ABD, which specifies location to F-actin, the large C-terminal region of the mammalian ABL protein contains additional location cues (Fig. 1). These include three independently functional nuclear localization signals (NLS) that drive the nuclear entry of ABL (7) and three cooperatively functional HMG-like boxes (HLB) that specify interaction with A/T-rich DNA (8). The nuclear accumulation of ABL is stimulated upon DNA damage (9, 10). However, the oncogenic BCR-ABL kinase does not enter the nucleus because the NLS functions are inactivated (but not mutated) in BCR-ABL (11). The BCR-ABL oligomers bind strongly to F-actin (3), which was proposed to be a mechanism for its cytoplasmic retention (6). Because BCR-ABL mutants defective in binding to actin remain cytoplasmic, the cytoplasmic tethering mechanism for BCR-ABL nuclear exclusion is not entirely correct (12). Further mutational analyses have suggested that intramolecular interactions involving three specific autophosphorylation sites in the kinase domain and sequences in the ABD (but not binding to F-actin) are important for the inactivation of the three NLS in the BCR-ABL fusion protein (12).

NES.

The mammalian ABL protein undergoes nucleocytoplasmic shuttling because it is also actively exported out of the nucleus (13). The nuclear export of ABL requires its nuclear export signal (NES), which binds to exportin-1 (13). The NES is embedded in the ABD, and a previous paper reported that the ABL-NES was not functional (6). That misleading conclusion is due to the problem of using a commercial preparation of anti-ABL antibody (K12) that nonspecifically stains the nuclear compartment. We have found that this anti-ABL antibody stains the nuclei of ABL-wild-type, ABL knockout, and ABL/ARG double-knockout cells equally well in immunofluorescence assays. It was unfortunate that an erroneous result generated by using a nonspecific anti-ABL was published (6). The necessity to verify the specificity of commercial anti-ABL antibody by using the appropriate knockout cells cannot be overemphasized.

In fibroblasts, adhesion to extracellular matrix (ECM) stimulates the nuclear export of ABL (14), and this is dependent on the NES that is embedded in the ABD (13). It is of interest that actin is present in the nucleus and plays an important role in the regulation of the genome structure (15). The interaction of ABL with nuclear actin could conceivably mask the NES and contribute to the nuclear retention of ABL; if so, fibroblast adhesion to the ECM may disrupt nuclear ABL interaction with nuclear actin to expose the NES and thus stimulate ABL nuclear export.

N-terminal variations.

The mammalian ABL1 gene encodes two variants (human Ia and Ib; mouse type I and type IV) with different N-terminal sequences that are transcribed from two distinct promoters (Fig. 1). Both variants are ubiquitously expressed. The human Ib and mouse type IV variant contains an N-terminal myristoylation site that is not found in the Ia (type I) variant. In the crystal structure of the SH3-SH2-kinase assembly, a myristate moiety is inserted in the kinase C-lobe to facilitate the SH2–C-lobe interaction (5). This myristate-facilitated autoinhibition is lost from the BCR-ABL and the Gag–v-Abl oncoproteins, and it is also missing from the Ia (type I) variant. However, the PXXP/SH3 intramolecular inhibitory interaction is present in the Ia (type I) variant. Thus far, none of the ABL-interacting proteins and substrates display variant specificity; therefore, the functional diversity of the ABL variants is presently not understood.

ABL KNOCKOUT CAUSES DEVELOPMENTAL ABNORMALITIES IN MICE

ABL is important for embryonic development because its knockout in mice causes embryonic and neonatal morbidity with variable penetrance depending on the mouse strain background (16). The C-terminal deletion of HLB-2, HLB-3, and the ABD in the mouse Abl1 gene also causes developmental defects, including morbidity (17). As mentioned above, the vertebrate genomes contain a related ABL2 (ARG) gene (1), but the Abl2-knockout mice are healthy and fertile (18). The combined deletion of Abl1 and Abl2 causes early lethality at embryonic day 8 to 9 (18). This acceleration of lethality in the double-knockout embryos suggests that Abl1/2 have redundant and essential functions in early embryonic development. The observation that the Abl1 (ABL) single knockout, but not the Abl2 (ARG) single knockout, causes developmental abnormalities suggests that ABL may have functions that cannot be replaced by ARG during later stages of mouse development. Because ABL and ARG genes are less well conserved in the middle region (1), the Abl1-specific developmental functions are likely to be determined by the less well conserved “location cues,” e.g., the three NLS that are not conserved in Abl2 (Fig. 1).

PATIENT TOLERANCE OF ABL/ARG KINASE INHIBITORS

Although ABL and ARG are essential to early embryonic development in mice, inhibitors of the ABL and ARG kinases, such as imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib, are well tolerated by human CML patients, some of whom have been treated for many years with those drugs to inhibit the oncogenic BCR-ABL kinase (19). A recent clinical study has linked long-term treatment with ABL/ARG kinase inhibitors to a reduction in the osteocalcin levels in cancer patients (20). This clinical finding may be related to mouse genetic studies showing that ABL kinase plays a role in bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling to promote osteoblast expansion and differentiation (21, 22). However, the early embryonic lethality of the ABL/ARG-double-knockout mice is certainly not a problem with adult patients treated with the ABL/ARG kinase inhibitors.

The tolerance of human patients to ABL/ARG kinase inhibitors may be explained by three alternative, although not mutually exclusive, possibilities: (i) the ABL/ARG kinase function is essential only to embryogenesis, and it is dispensable in adult life; (ii) the inhibitors do not completely block the ABL/ARG kinase function; and (iii) the ABL/ARG proteins, but not kinase activity, carry the essential functions that are not disrupted in patients treated with the kinase inhibitors. The observation that C-terminal truncation of ABL also causes lethality in mice (17) could be taken as an indication that the C-terminal region may have essential functions that are independent of ABL kinase activity. There has been one report that the ABL kinase domain, but not its catalytic activity, stimulates the ubiquitination and degradation of DDB2 to inhibit the repair of UV-induced photoadducts in genomic DNA (23). However, as the studies of ABL have been focused on its kinase function, this minireview will discuss the biological functions of the ABL kinase.

ABL IS NOT A MASTER SWITCH KINASE

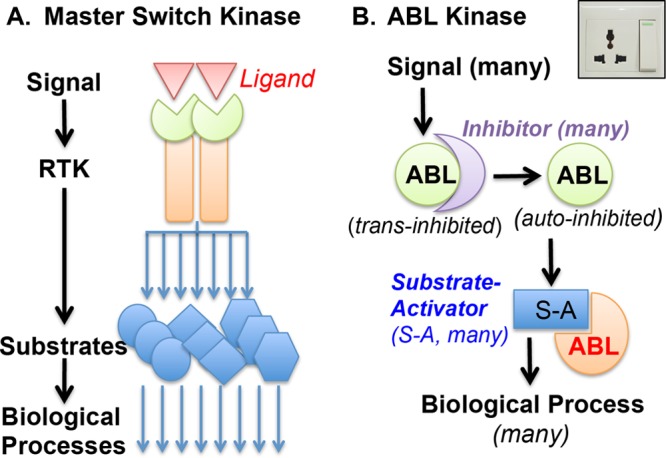

The biological functions of a protein kinase can be deduced from its upstream activators and downstream substrates. The most familiar example is that of a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)—it is allosterically activated by ligand binding to the extracellular domain; it then phosphorylates its own intracellular domain and other intracellular proteins. By design, RTK functions as a master switch that turns on a complex network of pathways in response to a specific extracellular signal (Fig. 2A). Other examples of master switch kinases are protein kinase A (PKA), which is activated by cyclic AMP (cAMP), and protein kinase B (PKB/AKT), which is activated by phosphotidyl-inositol-3,4,5-phosphate (PIP3). These serine/threonine protein kinases can transduce a variety of extracellular signals that cause the upregulation of second messengers such as cAMP or PIP3. In this master switch paradigm, a protein kinase is activated by a specific signal and proceeds to amplify that signal by phosphorylating a whole host of substrates. While this paradigm provided the rationale for most of the early studies on ABL, the results obtained on ABL kinase regulation have been at odds with it being activated by a specific growth factor, a specific second messenger, or a specific upstream kinase. Instead, ABL kinase is activated by many different extrinsic ligands, including those that activate RTKs such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), EPH, MET, and others (2). ABL kinase is also activated by intrinsic signals such as DNA damage and oxidative stress (24). With each signal, the current results suggest that ABL kinase may be activated restrictedly, that is, each signal may activate only a fraction of the cellular ABL proteins to phosphorylate selective substrates (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

ABL is not a master switch kinase. (A) Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) is a master switch kinase that is activated by a specific signal—its extracellular ligand—and amplifies that signal by phosphorylating a whole host of intracellular proteins. (B) ABL tyrosine kinase is not a master switch kinase. ABL binds to different trans inhibitors (depicted as a crescent) that partition this nonreceptor tyrosine kinase into different signaling complexes. Signal-regulated release of ABL from a trans inhibitor may not be sufficient for kinase activation if that release does not disrupt the autoinhibitory kinase assembly established by intramolecular inhibitory interactions (Fig. 1) (the autoinhibited ABL is depicted as a full pie in this diagram). In order to become phosphorylated by ABL, a substrate must disrupt autoinhibition. Many ABL substrates identified thus far are ABL-SH3-binding proteins, which disrupt the internal SH3/PXXP interaction to activate ABL (the substrate-bound and activated ABL is depicted as a three-quarter pie in this diagram). Other ABL substrates interact with the SH2 domain or the PRL (Fig. 1), and those interactions may also disrupt autoinhibition. The molecular design of ABL is more similar to an electric socket (upper right) than a master switch (see the text for discussion of this two-step mechanism of restricted ABL activation in signal transduction).

The idea that ABL kinase is activated restrictedly came from two lines of reasoning. The first line of reasoning takes into consideration the signal-dependent ABL effects, e.g., ABL can stimulate cell survival in response to growth factors but it can also stimulate cell death in response to DNA damage. It is of note that nuclear accumulation of ABL occurs upon DNA damage but not after growth factor stimulation. Furthermore, it has been shown that nuclear entrapment of the BCR-ABL oncogenic kinase can cause cell death (11). As the three ABL NLS are inactivated in the constitutively active BCR-ABL kinase (11, 12), the NLS may also be inactivated in those ABL molecules that become activated at the plasma membrane or in the cytoplasm. In other words, depending on the subcellular localization where it is activated, ABL kinase can transduce either a survival or a death signal. The second line of reasoning that ABL is activated restrictedly takes into consideration the molecular design of its autoinhibitory kinase assembly.

AUTOINHIBITION OF ABL KINASE

The early studies of ABL kinase regulation focused on the ABL-SH3 domain because it is absent from the constitutively activated Gag–v-Abl kinase and because SH3 deletion is sufficient to cause kinase activation (25). Those results led to the working hypothesis that an ABL-SH3-binding inhibitor controls the upstream regulation of this kinase. The field searched for ABL-SH3-binding proteins and discovered the PXXP motif for binding to the SH3 domain (26). A large number of ABL-SH3-binding proteins have now been identified either empirically or by computational prediction (1, 27). Although initially reported as “inhibitors,” many of those ABL-SH3-binding proteins have turned out to be ABL substrates (1). The hypothesis of an SH3-binding inhibitor was put to rest when the crystal structure of the SH3-SH2-kinase domains showed that the SH3 binds an internal PXXP motif and that this intramolecular SH3/PXXP interaction locks the kinase in an inactive conformation (Fig. 1) (5). Deletion of the SH3 domain or mutation of the internal PXXP motif disrupts this autoinhibitory interaction and leads to ABL kinase activation (28). When a PXXP-containing protein binds to the ABL-SH3 domain, it also disrupts the intramolecular PXXP/SH3 interaction to activate the ABL kinase. Therefore, the majority of the ABL-SH3-binding proteins themselves or their associated proteins are ABL substrates (1, 28).

The autoinhibitory assembly of the ABL SH3-SH2-kinase domains is very similar to that of the SRC-family tyrosine kinases, e.g., SRC and HCK (29, 30). With HCK, the intramolecular SH3/PXXP interaction must be disrupted for kinase activation (31). In addition, the intramolecular SH2/pY527 interaction must also be disrupted, through dephosphorylation of pY527, for SRC kinase activation (32). The ABL SH2 domain does not engage in an intramolecular interaction with a phosphorylated tyrosine. Rather, the binding of a myristate group to the kinase C-lobe can stabilize the SH2–C-lobe interaction (5). Because the full-length ABL structure has not been solved, participation of ABL C-terminal sequences in its autoinhibitory assembly cannot be ruled out at this time.

trans INHIBITION OF ABL KINASE

Elucidation of the autoinhibitory assembly does not exclude additional trans-inhibitory mechanisms in the regulation of ABL kinase (Fig. 2B). It has been shown that F-actin, by binding to the ABD (Fig. 1), can cause kinase inhibition (33). Interestingly, the inhibitory effect of F-actin requires the ABL-SH2: although ΔSH2-ABL still binds F-actin, it is not inhibited by F-actin (33). Because the SH2 domain is an integral part of the autoinhibitory assembly, we coined the term “coinhibition” to propose a mechanism where F-actin binding to the ABD can allosterically enforce and/or stabilize the autoinhibitory assembly and thus inactivate the ABL kinase function (34). Supporting the idea that the ABD can affect the autoinhibitory assembly was the finding that mutations in the ABD could cause resistance to imatinib, which is an ATP mimetic that binds to the inactive conformation of the kinase domain (12, 35). In the absence of a full-length ABL structure, the proposed allosteric interaction between the N-terminal autoinhibitory assembly and the C-terminal ABD of ABL has remained a hypothesis.

Another example of a trans inhibitor is the retinoblastoma protein (RB), which inhibits the ABL kinase by binding to the N-lobe of the kinase domain (36). Because RB binding can also inhibit the constitutively activated BCR-ABL (37), this trans inhibition may not require the autoinhibitory assembly. Interestingly, RB can become tyrosine phosphorylated by ABL (38). The mechanism by which RB the inhibitor converts to RB the substrate is presently unknown. Disruption of RB binding to the ABL kinase domain is mediated by cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)/cyclin-dependent RB phosphorylation (39). However, the release of RB from ABL would not be sufficient for ABL kinase activation should the autoinhibitory assembly of the SH3-SH2-kinase domain remain intact after RB dissociation.

SUBSTRATE ACTIVATORS

Because of the intramolecular autoinhibitory assembly, a substrate has to perturb the internal interactions among the SH3, SH2, and kinase domains either by itself or by an associated factor in order to become phosphorylated by ABL (Fig. 2B). If ABL regulation were to follow the master switch paradigm, an upstream activator would have to stably disrupt the autoinhibitory assembly through direct physical interactions or covalent modifications. This activation mechanism applies to the BCR-ABL oncogenic kinase, which is “stably activated” by BCR-dependent oligomerization (40) and mutational inactivation of the autoinhibitory assembly (41), as well as autophosphorylation (28, 34). Tyrosine phosphorylation of ABL at Y245 in the PXXP motif can disrupt the SH3/PXXP interaction to activate the kinase; however, the Y245F mutant remains catalytically competent in substrate phosphorylation, showing that the SH3/PXXP autoinhibitory interaction can be disrupted by mechanisms other than tyrosine phosphorylation of Y245 (28, 42). With the SRC-family kinases, dephosphorylation of pY527 is a universal mechanism for the disruption of autoinhibition. However, such as a universal mechanism for the disruption of the ABL autoinhibitory assembly has not been identified. Instead, the autoinhibited ABL appears to be activated by proteins that bind to its SH3 or SH2 or the proline-rich linker (PRL), because those ABL-binding proteins are the ABL substrates (Fig. 1 and 2B). For example, Abi binds to the ABL SH3 domain and the PRL (Fig. 1) to become phosphorylated by ABL (43, 44), whereas CRK binds to the PRL (45) to become phosphorylated by ABL. How binding to this PRL in ABL affects its autoinhibitory assembly is still unknown because the PRL is not present in the current crystal structure.

In a previous review, Colicelli compiled a list of 116 ABL-interacting proteins, of which 76 are ABL substrates that bind to the SH3, the SH2, and/or the PRL (1). The finding that ABL substrates directly bind to the SH3 or SH2 domain supports the idea that ABL substrates are also its allosteric activators (Fig. 2B). Besides SRC and ABL, this mechanism of kinase regulation by substrate activators has also been described for the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase FES (46, 47).

ABL ACTIVATION IN SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION

Regulation of ABL by its substrate activators can be conceptualized by comparing this kinase to an electric socket (Fig. 2B). In this concept, the ABL socket can be switched off by a trans inhibitor and switched on when trans inhibition is relieved by a signal. After a signal-stimulated release from a trans inhibitor, the ABL socket remains inactive until a downstream target is recruited by the signal to plug into the socket, that is, to disrupt the autoinhibited confirmation (Fig. 2B). In this concept, ABL can be regulated by a two-step mechanism where the upstream signal needs to (i) disrupt the ABL interaction with a trans inhibitor and (ii) stimulate the ABL interaction with its substrate activator (Fig. 2B). With this two-step activation mechanism, it is conceivable that the ABL protein may be prepartitioned into multiple distinct protein complexes in one cell, and in each complex, ABL is held inactive by binding to one of its trans inhibitors that would then determine the signaling function of that particular, prepartitioned, ABL molecule (Fig. 2B). For example, a fraction of nuclear ABL that is in complex with RB/E2F is prepartitioned to respond to the activation of CDK/cyclin during cell cycle progression because CDK/cyclin-mediated RB phosphorylation causes RB release from ABL (36, 39, 48). Theoretically, for every ABL-containing complex, a signal-regulated release from the trans inhibitor can stimulate the phosphorylation of a substrate activator that is preassembled in that complex. Alternatively, the signal that stimulates the release of trans inhibition may induce the binding of a substrate activator to the released ABL for phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). Of course, the autoinhibited ABL confirmation, if sufficiently stable without trans inhibition, can be activated in one step by a signal that induces the binding of a substrate activator.

FUNCTIONAL DIVERSITIES OF ABL SUBSTRATES

A large number of proteins have been found to be phosphorylated by the ABL kinase, and these ABL substrates are functionally diverse, including adaptors, other kinases, cytoskeletal proteins, transcription factors, chromatin modifiers, and others (1). ABL phosphorylates nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins, consistent with its shuttling between these two subcellular compartments. Besides the cytoplasmic versus the nuclear classification, the ABL substrates can also be divided along two lines—(i) those which regulate actin polymerization and biological processes that involve actin and (ii) those which regulate transcription and the chromatin.

Actin polymerization.

ABL regulates actin polymerization by phosphorylating Abi and WAVE2, which are two critical components of the WAVE regulatory complex (WRC) that activates Arp2/3 (49, 50). Abi was discovered as an ABL-SH3-binding protein and originally reported as an ABL inhibitor (43, 44). However, both Abi and WAVE2 bind to the ABL-SH3 domain and both are ABL substrates (49). Because ABL contains an ABD (Fig. 1), it makes sense that this tyrosine kinase regulates actin polymerization. It is interesting that ABL stimulates actin polymerization but that F-actin is an allosteric coinhibitor of ABL kinase (51). These findings suggest that the effect of ABL on actin polymerization may be self-limiting and thus compatible with the dynamic turnover of F-actin in various actin-dependent biological processes (51).

Because the actin cytoskeleton plays a critical role in many processes, the regulation of actin polymerization by ABL has the potential to influence as many processes. The formation of membrane protrusions such as lamellipodia, filopodia, and ruffles requires actin polymerization, and ABL is known to regulate those processes that are fundamental to cell adhesion and migration (51). Intracellular trafficking of membrane organelles is also regulated by the actin cytoskeleton (52); therefore, the reported effects of ABL kinase on endocytosis (53) and autophagy (54, 55) might involve ABL-regulated interactions of those membrane organelles with actin. Antigen-stimulated formation of immune synapse in lymphocytes and neuronal synapse formation, as well as bacterial adhesion to host cells, are also processes that require F-actin, and ABL has been shown to play a role in each of those processes (56–58). Furthermore, ABL's role in epithelial cell-cell adhesion, polarity, and migration can also be explained by its regulation of actin polymerization (2). Because the WRC and the Arp2/3 complexes are also found in the nucleus and because nuclear actin regulates genome structure and function (15), it is possible that the nuclear ABL kinase also regulates the nuclear functions of actin.

This generalized view that regulation of actin polymerization underlies many of ABL's biological functions is clearly oversimplified, because ABL interacts with different proteins and phosphorylates different substrates to regulate the formation of membrane ruffles, neuronal synapses, or bacterial adhesion pedestals. The role of actin in membrane invagination, vesicle movement, sorting, and fusion is not yet fully elucidated, and this gap in knowledge may account for the incomplete understanding of how ABL and its substrates regulate endocytosis and autophagy. Although overly simplistic, the concept of signal- and/or organelle-specific regulation of actin polymerization by ABL can provide a unifying framework to explain the seemingly chaotic collection of biological effects attributable to the ABL tyrosine kinase.

Transcription and chromatin.

One of the first nuclear substrates of ABL identified is the C-terminal repeated domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) (59). The CTD consists of a 7-amino-acid repeat with the consensus sequence Y1S2P3T4S5P6S7 that can become phosphorylated in each of the Y, S, and T residues (60). The CTD is a landing pad for many cellular proteins, including those required for the cotranscriptional processing of nascent RNA and the modification of chromatin, and those CTD-protein interactions are regulated by CTD phosphorylation (60). Serine-5 or serine-2 phosphorylation of the CTD stimulates the recruitment of CTD-binding proteins, but tyrosine-1 phosphorylation disrupts those interactions (61). Through CTD tyrosine phosphorylation, ABL is likely to regulate RNA processing and chromatin modifications during transcription elongation. Although ABL binds DNA, it does not recognize specific DNA sequences (8). Whether ABL-dependent CTD tyrosine phosphorylation occurs generally or is restricted to specific transcription units is currently unknown, although the reported interactions of ABL with sequence-specific transcription factors such as the p53 family members would suggest gene-specific ABL effects.

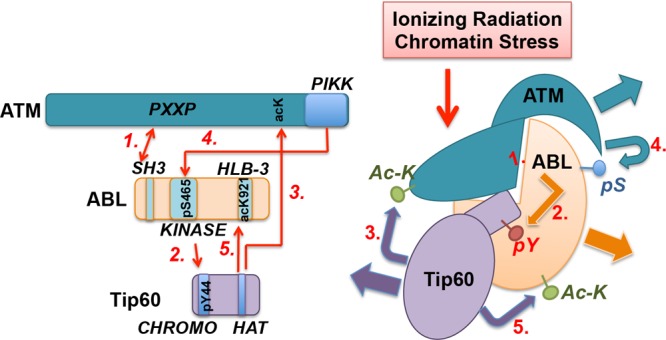

One of the most recent nuclear ABL substrates identified is KAT5/Tip60, which is a histone acetyltransferase (62). It was reported that ionizing radiation (IR) or the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) could induce ABL-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Tip60 on Tyr44 in the CHROMO domain (62) (Fig. 3). A previous report has shown that IR stimulates the interaction of ABL with Tip60 and that Tip60 acetylates ABL on a lysine residue (Lys921) in the HLB-3 of the ABL DNA binding domain (63) (Fig. 1 and 3). Interestingly, IR also stimulates ATM-dependent phosphorylation of ABL on a serine residue (Ser465) in the kinase C-lobe (64) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, ATM is required for DNA damage to induce ABL nuclear accumulation (10). Judging from its position in the three-dimensional structure, S465 phosphorylation of ABL is unlikely to disrupt the autoinhibitory assembly. This structure-based deduction is consistent with the finding that ATM kinase activity (and therefore S465 phosphorylation) is not required for ABL to phosphorylate Tip60 (62). In other words, ATM-dependent Ser465 phosphorylation is not required for ABL kinase activation by IR. Interestingly, however, ATM kinase and ABL-pSer465 are required for ABL acetylation by Tip60 (63). Taken together, these results suggest a possible three-way cross talk among ABL, ATM, and Tip60 in response to IR or chromatin stress (CS) (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

ABL interactions with and modifications by ATM and Tip60 in DNA damage response. This model of ABL interactions and modifications is based on four reports (62–65). Ionizing radiation (IR) or chromatin stress (CS) stimulates ABL interactions with ATM and Tip60. A PXXP motif in ATM binds the ABL-SH3 domain (65) and can thus disrupt the autoinhibitory assembly to activate the ABL kinase (step 1). IR also stimulates ABL interaction with Tip60 (63) and the tyrosine phosphorylation of Tip60 at Tyr44 (62) in the N-terminal CHROMO domain (step 2) by ABL. Tyrosine phosphorylation (pY) of Tip60 stimulates its acetylation of ATM and the activation of ATM kinase (62) (step 3). The activated ATM kinase in turn phosphorylates ABL at Ser465 (pS) (64) (step 4). Ser465 phosphorylation is required for the acetylation of ABL at Lys921 by Tip60 (63) (step 5). Because ABL knockout does not interfere with ATM activation, and because the loss of ABL does not cause radiosensitivity, which is the phenotype of ATM loss (79), ABL is not an obligatory upstream activator of ATM. A simple linear pathway also cannot accommodate the findings that ATM loss causes radiosensitivity whereas ABL loss reduces the apoptosis response but does not cause radiosensitivity. Instead, these interactions are likely to be designed to alter the covalent modifications of ABL (S465 phosphorylation and K921 acetylation) in the DNA damage response.

Because IR induces the interaction of ABL with ATM (65) and Tip60 (63), it is likely that IR can stimulate the formation of a ternary complex of ATM-ABL-Tip60 (Fig. 3). In this complex, a PXXP motif in ATM binds to the ABL-SH3 domain (65), disrupts the autoinhibitory assembly (step 1, Fig. 3), and causes ABL kinase activation, which then phosphorylates Tip60 in its CHROMO domain (step 2, Fig. 3). Tyrosine phosphorylation of Tip60, through an unknown mechanism, stimulates ATM acetylation to activate the ATM serine/threonine kinase (62) (step 3, Fig. 3). The activated ATM kinase then phosphorylates ABL on S465 (64) (step 4, Fig. 3), which is required for ABL to become acetylated on K921 by Tip60 (63) (step 5, Fig. 3). The ATM-mediated S465 phosphorylation and the Tip60-mediated K921 acetylation may each generate a recognition motif to facilitate ABL interaction with other proteins and thus propagate the IR or the CS signal. If correct, the proposed three-way interaction and mutual modifications among ABL tyrosine kinase, ATM serine/threonine kinase, and Tip60 acetyltransferase illustrate how regulation of ABL kinase through signal-induced protein-protein interactions can affect not only its downstream substrates (Tip60) but also its own modifications (serine phosphorylation and lysine acetylation).

Recent additions to the list of ABL substrates.

In addition to Tip60, Table 1 provides a summary of a few other ABL substrates that were not included in the 2010 review, which contains a comprehensive summary of over 100 substrates of the ABL and the BCR-ABL kinases (1). The short list of ABL substrates in Table 1 includes the proapoptotic MST2 serine/threonine kinase (66), which is a component of the Hippo pathway. The nuclear effector of the Hippo pathway, namely, YAP1, is also phosphorylated by ABL to promote cell death (67) (YAP1 was included as a substrate in the 2010 review [1]). Together, MST1 and YAP1 can be placed in the transcription/chromatin category of ABL substrates, and they are the effectors of the prodeath function of ABL. Through a screen for small interfering RNA (siRNA) that affects the mitotic spindles, ABL was identified as a regulator of spindle orientation, and this effect of ABL can be linked to the tyrosine phosphorylation of NuMA (68). Regulation of spindle orientation also involves the polarity complex and may thus involve the actin cytoskeleton (67). Recently, ABL was shown to phosphorylate Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in juvenile Parkinson's disease (PD). Parkin is thought to mediate the ubiquitination of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins to stimulate mitophagy (69). Tyrosine phosphorylation of Parkin inhibits its E3 ligase activity and contributes to the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons, possible through the accumulation of damaged mitochondria (70). Judging from the rate of addition, the number and the functional diversity of ABL substrates are likely to expand further in the years to come.

TABLE 1.

Recently identified ABL substratesa

| Protein | Gene (ID no.) | pY site | Function | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NuMA | NUMA1 (4926) | Y1774 | Mitotic spindle formation | 67 |

| Parkin | PARK2 (5071) | Y143 | E3 ubiquitin ligase | 68, 69 |

| Tip60 | KAT5 (10524) | Y44 | Histone acetyltransferase | 61 |

| MST | STK3 (6788) | Y81 | Proapoptotic serine/threonine protein kinase, a Hippo pathway component | 65 |

The table lists substrates that were not summarized in the 2010 review (1), which identified more than 100 substrates that had been reported to be phosphorylated by ABL and BCR-ABL kinases.

TISSUE-SPECIFIC ABL FUNCTIONS IN CONDITIONAL KNOCKOUT MICE

Because the Abl1/2 double knockout causes early embryonic lethality (18), conditional knockout of Abl1 in the Abl2+/+ or the Abl2−/− genetic background has been used to examine the in vivo effects of Abl1 knockout in different tissues and cell types. The phenotypes of several tissue-specific Abl1-knockout embryos and/or adult mice are briefly mentioned below.

Cerebellar development.

As mentioned above, Abl1/2 double knockout causes early embryonic lethality associated with defect in neurulation (18). However, knockout of Abl1 (by Nestin-Cre) in the neuron and glia progenitor cells, in either the Abl2+/+ or the Abl2−/− genetic background, did not cause a neurulation defect or embryonic lethality (71). Cerebellar malformation and motor coordination deficits were observed in adult mice, but only when the Nestin-Cre knockout of Abl1 was combined with the constitutional knockout of Abl2 (71). In contrast, deletion of Abl1 by Math1-Cre in the cerebellar granule cells of Abl2−/− mice did not lead to cerebellar malformation (71). These results show that ABL (Abl1) and ARG (Abl2) do not have essential functions in the nestin-expressing cells during embryo development and that the cause for the neurulation defect of the ABL/ARG-double-knockout embryo is still unclear.

Vascular development.

The knockout of Abl1 by Tie2-Cre in the Abl2−/− genetic background caused late embryonic and neonatal lethality (72). Death of the mutant embryos was associated with liver necrosis, indicative of a liver-specific defect in vascular development and/or function (72). Mice with Tie2-Cre-mediated deletion of Abl1 in the Abl2+/− genetic background survived to adulthood, and about ∼15% of those mutant mice were runts and showed cardiac and lung defects attributable to deficiencies in vascular development and/or function (72).

T-cell development and signaling.

In T cells, the conditional knockout of Abl1 (by Lck-Cre) interfered with actin polymerization at the immune synapse (56) and inhibited chemokine-induced cell migration (73). The mouse genetic study of Abl1/2-deficient T cells has previously been reviewed (74).

Smooth muscle contraction and asthma.

In airway smooth muscle cells, Abl1 knockout (by Sm22-Cre) reduced acetylcholine-induced contraction and inhibited asthma-associated smooth muscle cell proliferation (75).

Muscle differentiation checkpoint.

Myogenic differentiation in explants of presomitic mesoderm (PSM) is inhibited by genotoxins, and this DNA damage-induced differentiation checkpoint response was defective in the PSM from muscle-specific Abl1-knockout (by MyoD-Cre) mouse embryos (76).

Neuronal cell death.

An interesting recent development in the study of ABL biological function has been the finding that the ABL kinase is activated in neurodegenerative diseases, e.g., Parkinson's disease (PD) (25, 70). It was found that ABL phosphorylated Parkin to inhibit its E3-ubiquitin ligase function (70). Treatment of mice with the dopaminergic toxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) stimulated ABL kinase and Parkin tyrosine phosphorylation. Interestingly, MPTP-induced Parkin tyrosine phosphorylation was not observed in mice with the neuronal knockout of Abl1 (by Nestin-Cre in the Abl2+/+ genetic background), and this phosphorylation defect correlated with a reduction in MPTP-induced neuronal cell death in the Abl1-deficient mouse brain (70). More recently, a brain-penetrant ABL kinase inhibitor was shown to also protect mice from the MPTP-induced loss of TH+ neurons (77).

Thus far, none of the tissue-specific knockouts of Abl1 in the Abl2+/+ genetic background has recreated the various low-penetrance phenotypes of the constitutional knockout of Abl1 in the Abl2+/+ background, possibly because the Abl1-knockout phenotypes are highly dependent on the mouse strain background. Furthermore, none of the tissue-specific knockouts of Abl1 in the Abl2−/− genetic background has recreated the early embryonic lethality and neurulation defect of the Abl1/2-double-knockout mice. However, each one of the tissue-specific Abl1 knockouts has resulted in tissue-specific defects. Although it remains possible that the neurulation defect of the Abl1/2-double-knockout embryo was due to the loss of an essential ABL/ARG function in one specific embryonic cell type (other than those expressing nestin), the alternative explanation that the many different tissue-specific ABL/ARG functions may collectively be required for early embryo development has not been ruled out.

EXPLORING NUCLEAR ABL FUNCTION IN MICE WITH NLS-KNOCK-IN MUTATIONS

The ABL-knockout strategy disrupts its cytoplasmic and nuclear functions. To separate those ABL functions in vivo, a μNLS (mutated in the nuclear localization signals) allele has been generated in Abl1 by knock-in substitution mutations of 11 lysines/arginines to glutamines to inactivate the three NLS (10). Nuclear entry of ABL is blocked in the Abl-μNLS homozygous embryonic stem (ES) cells, fibroblasts, and renal epithelial cells (10, 78). Despite the loss of nuclear ABL, the Abl-μNLS homozygous mice are healthy and fertile, showing that the nuclear entry of ABL is not essential to embryonic development. Interestingly, there were no live births of mice homozygous for the Abl-μNLS and the Arg-knockout (Ablμ/μ; Arg−/−) alleles. This late embryonic lethality was associated with shrinkage of the midbrain (I. C. Hunton and J. Y. J. Wang, unpublished observation), indicating that mouse ARG might have a midbrain-specific nuclear function that is redundant with that of the nuclear ABL during development. Although ARG does not have the three NLS found in ABL, it contains the NES. It is conceivable that ARG also contains one or more NLS that can drive its nuclear import in specific cell types where ARG and ABL have redundant nuclear functions that are required for the proper development of the midbrain during mouse embryogenesis.

Following DNA damage, ABL becomes accumulated in the nucleus, and this response requires ATM (10). As discussed above, a recent report showed that ABL phosphorylates Tip60 to facilitate the acetylation and activation of ATM kinase in response to IR (62) (Fig. 3). Because the Abl-μNLS mice do not exhibit any of the ATM-knockout phenotypes, such as radiation sensitivity, immune deficiency, and early-onset thymomas, nuclear ABL must not be essential to the activation of ATM in mice. Perhaps the ABL/Tip60-dependent activation of ATM is unique to the specific cell type, i.e., retinal pigmented epithelial cells (RPE1), used in the study of Tip60 tyrosine phosphorylation (62). In chick DT40 cells, it has been shown that the knockout of ATM causes radiosensitivity but the knockout of ABL does not sensitize cells to IR (79). We have confirmed the conclusion that loss of ABL does not cause radiosensitivity using ABL-knockout mouse embryo fibroblasts (L. D. Wood and J. Y. J. Wang, unpublished data). However, the knockout of ABL reduces the apoptotic response to IR in DT40 cells, consistent with the apoptosis-defective phenotype of the Abl-μNLS mice (78, 79). In RPE1 cells, knockdown of ATM or Tip60 caused radiosensitivity, but the effect of ABL knockdown on radiosensitivity in RPE1 cells was not examined (62). It should be noted that the determining factor of radiosensitivity is the efficiency of DNA repair but not apoptosis (80). In fact, apoptotic removal of DNA-damaged cells, which requires the activation of nuclear ABL kinase, may have a beneficial effect on tissue regeneration (81). Since none of the ATM-knockout phenotypes has been detected in the Abl-μNLS, the Abl−/−, or the conditional-Abl−/−; Arg−/− mice, there is no genetic evidence to support a linear pathway where ABL acts upstream of Tip60 to activate ATM in DNA damage response. Interestingly, however, Tip60-dependent K921 acetylation is found to stimulate the proapoptotic function of ABL (63). Together, current results suggest that ABL is not an obligatory upstream activator of the radioprotective functions of ATM or Tip60; rather, ABL modifications by ATM and Tip60 may be important for the activation of its proapoptotic function.

The proapoptotic function of ABL involves the regulation of several pathways, including activation of the p53 family- and the YAP-dependent gene expression programs (24, 67). A recent study found that IR induced the nuclear accumulation of ABL in prostate cancer cells to stimulate the expression of colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1), which promotes the infiltration of myeloid cells to the tumor site of radiation (82). Using cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity as an experimental model to study DNA damage-induced apoptosis in renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTC), we found that upregulation of PUMA mRNA was unaffected in the Abl-μNLS kidney (78). However, expression of the PUMA protein could not be sustained in the Abl-μNLS kidney, and the RPTC apoptotic response was correspondingly reduced (78). These results suggest that nuclear ABL is required for the accumulation of PUMA protein, which stimulates cytochrome c to induce apoptosis (83). Together, current results suggest that DNA damage-induced nuclear ABL kinase activation, serine phosphorylation, and lysine acetylation may stimulate apoptosis through transcriptional as well as posttranscriptional mechanisms.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

Taken together, results from decades of structural, biochemical, cell biological, and mouse genetic studies have suggested that the ubiquitously expressed ABL tyrosine kinase may have many biological functions that are dictated by the cell types and the activating signals. Because the full-length structure of ABL has not been elucidated, and because the cause of abnormalities observed with the ABL-knockout mice is not known, there remains the possibility that ABL has a single, unifying function that can explain its diverse biological effects. A more prudent view, for the time being, is to consider that ABL has different biological functions in different cell types and that ABL can regulate different pathways in response to different signals. If so, the biological functions of ABL cannot be readily extrapolated or generalized from one experimental model to another. Considering that the ABL kinase has evolved to carry out context-dependent functions, future advances on ABL will likely be driven by the studies of biological processes in which it functions rather than the more traditional gene-centric approaches.

Because ABL is capable of regulating many aspects of biology that are relevant to human diseases from cancer to neuronal degeneration, elucidation of its mechanism of action in each defined biological context is worthwhile even if the knowledge may not apply to other contexts. For example, the requirement for nuclear ABL in cisplatin-induced apoptosis was observed with RPTC but not thymocytes (P. Sridevi and J. Y. J. Wang, unpublished data), but the knowledge that RPTC death can be suppressed by the loss of nuclear ABL is useful to the amelioration of nephrotoxicity in patients undergoing platinum-based cancer therapy. Similarly, ABL kinase-dependent phosphorylation and inactivation of Parkin might be relevant to a subset of neuronal death but not neurodegenerative diseases in general. Nevertheless, understanding the regulation of ABL-dependent phosphorylation of Parkin may shed light on one of the causes for neuronal cell death. Given the cumulative knowledge, the molecular reagents, the mutant mouse strains, the FDA-approved inhibitors, and the cancer patients with chronic exposure to those drugs, ABL is well positioned for future explorations of its biological functions in the context of human diseases besides leukemia and cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My work on ABL has been supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute, RO1CA043054.

This review could not have been written without the brilliant work of many undergraduates, graduate students, and postdocs in my laboratory, as well as hundreds of other basic research laboratories throughout the world.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 January 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Colicelli J. 2010. ABL tyrosine kinases: evolution of function, regulation, and specificity. Sci. Signal. 3:re6. 10.1126/scisignal.3139re6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greuber EK, Smith-Pearson P, Wang J, Pendergast AM. 2013. Role of ABL family kinases in cancer: from leukaemia to solid tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13:559–571. 10.1038/nrc3563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McWhirter JR, Wang JY. 1991. Activation of tyrosinase kinase and microfilament-binding functions of c-abl by bcr sequences in bcr/abl fusion proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:1553–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McWhirter JR, Wang JY. 1993. An actin-binding function contributes to transformation by the Bcr-Abl oncoprotein of Philadelphia chromosome-positive human leukemias. EMBO J. 12:1533–1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagar B, Hantschel O, Young MA, Scheffzek K, Veach D, Bornmann W, Clarkson B, Superti-Furga G, Kuriyan J. 2003. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of c-Abl tyrosine kinase. Cell 112:859–871. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00194-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hantschel O, Wiesner S, Guttler T, Mackereth CD, Rix LL, Mikes Z, Dehne J, Gorlich D, Sattler M, Superti-Furga G. 2005. Structural basis for the cytoskeletal association of Bcr-Abl/c-Abl. Mol. Cell 19:461–473. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wen ST, Jackson PK, Van Etten RA. 1996. The cytostatic function of c-Abl is controlled by multiple nuclear localization signals and requires the p53 and Rb tumor suppressor gene products. EMBO J. 15:1583–1595 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miao YJ, Wang JY. 1996. Binding of A/T-rich DNA by three high mobility group-like domains in c-Abl tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:22823–22830. 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida K, Yamaguchi T, Natsume T, Kufe D, Miki Y. 2005. JNK phosphorylation of 14-3-3 proteins regulates nuclear targeting of c-Abl in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:278–285. 10.1038/ncb1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preyer M, Shu CW, Wang JY. 2007. Delayed activation of Bax by DNA damage in embryonic stem cells with knock-in mutations of the Abl nuclear localization signals. Cell Death Differentiation 14:1139–1148. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vigneri P, Wang JY. 2001. Induction of apoptosis in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells through nuclear entrapment of BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase. Nat. Med. 7:228–234. 10.1038/84683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preyer M, Vigneri P, Wang JY. 2011. Interplay between kinase domain autophosphorylation and F-actin binding domain in regulating imatinib sensitivity and nuclear import of BCR-ABL. PLoS One 6:e17020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taagepera S, McDonald D, Loeb JE, Whitaker LL, McElroy AK, Wang JY, Hope TJ. 1998. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of C-ABL tyrosine kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:7457–7462. 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis JM, Baskaran R, Taagepera S, Schwartz MA, Wang JY. 1996. Integrin regulation of c-Abl tyrosine kinase activity and cytoplasmic-nuclear transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:15174–15179. 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon DN, Wilson KL. 2011. The nucleoskeleton as a genome-associated dynamic ‘network of networks.’ Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12:695–708. 10.1038/nrm3207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tybulewicz VL, Crawford CE, Jackson PK, Bronson RT, Mulligan RC. 1991. Neonatal lethality and lymphopenia in mice with a homozygous disruption of the c-abl proto-oncogene. Cell 65:1153–1163. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90011-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartzberg PL, Stall AM, Hardin JD, Bowdish KS, Humaran T, Boast S, Harbison ML, Robertson EJ, Goff SP. 1991. Mice homozygous for the ablm1 mutation show poor viability and depletion of selected B and T cell populations. Cell 65:1165–1175. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90012-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koleske AJ, Gifford AM, Scott ML, Nee M, Bronson RT, Miczek KA, Baltimore D. 1998. Essential roles for the Abl and Arg tyrosine kinases in neurulation. Neuron 21:1259–1272. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80646-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Druker BJ. 2008. Translation of the Philadelphia chromosome into therapy for CML. Blood 112:4808–4817. 10.1182/blood-2008-07-077958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berman E, Girotra M, Cheng C, Chanel S, Maki R, Shelat M, Strauss HW, Fleisher M, Heller G, Farooki A. 2013. Effect of long term imatinib on bone in adults with chronic myelogenous leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Leuk. Res. 37:790–794. 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh-Choudhury N, Mandal CC, Das F, Ganapathy S, Ahuja S, Ghosh Choudhury G. 2013. c-Abl-dependent molecular circuitry involving Smad5 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulates bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced osteogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 288:24503–24517. 10.1074/jbc.M113.455733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kua HY, Liu H, Leong WF, Li L, Jia D, Ma G, Hu Y, Wang X, Chau JF, Chen YG, Mishina Y, Boast S, Yeh J, Xia L, Chen GQ, He L, Goff SP, Li B. 2012. c-Abl promotes osteoblast expansion by differentially regulating canonical and non-canonical BMP pathways and p16INK4a expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 14:727–737. 10.1038/ncb2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Zhang J, Lee J, Lin PS, Ford JM, Zheng N, Zhou P. 2006. A kinase-independent function of c-Abl in promoting proteolytic destruction of damaged DNA binding proteins. Mol. Cell 22:489–499. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaul Y, Ben-Yehoyada M. 2005. Role of c-Abl in the DNA damage stress response. Cell Res. 15:33–35. 10.1038/sj.cr.7290261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlatterer SD, Acker CM, Davies P. 2011. c-Abl in neurodegenerative disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 45:445–452. 10.1007/s12031-011-9588-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren R, Mayer BJ, Cicchetti P, Baltimore D. 1993. Identification of a ten-amino acid proline-rich SH3 binding site. Science 259:1157–1161. 10.1126/science.8438166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou T, Chen K, McLaughlin WA, Lu B, Wang W. 2006. Computational analysis and prediction of the binding motif and protein interacting partners of the Abl SH3 domain. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2:e1. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hantschel O, Superti-Furga G. 2004. Regulation of the c-Abl and Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:33–44. 10.1038/nrm1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sicheri F, Moarefi I, Kuriyan J. 1997. Crystal structure of the Src family tyrosine kinase Hck. Nature 385:602–609. 10.1038/385602a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu W, Harrison SC, Eck MJ. 1997. Three-dimensional structure of the tyrosine kinase c-Src. Nature 385:595–602. 10.1038/385595a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moarefi I, LaFevre-Bernt M, Sicheri F, Huse M, Lee CH, Kuriyan J, Miller WT. 1997. Activation of the Src-family tyrosine kinase Hck by SH3 domain displacement. Nature 385:650–653. 10.1038/385650a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu W, Doshi A, Lei M, Eck MJ, Harrison SC. 1999. Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoinhibitory mechanism. Mol. Cell 3:629–638. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80356-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodring PJ, Hunter T, Wang JY. 2001. Inhibition of c-Abl tyrosine kinase activity by filamentous actin. J. Biol. Chem. 276:27104–27110. 10.1074/jbc.M100559200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JY. 2004. Controlling Abl: auto-inhibition and co-inhibition? Nat. Cell Biol. 6:3–7. 10.1038/ncb0104-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levinson NM, Kuchment O, Shen K, Young MA, Koldobskiy M, Karplus M, Cole PA, Kuriyan J. 2006. A Src-like inactive conformation in the abl tyrosine kinase domain. PLoS Biol. 4:e144. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welch PJ, Wang JY. 1993. A C-terminal protein-binding domain in the retinoblastoma protein regulates nuclear c-Abl tyrosine kinase in the cell cycle. Cell 75:779–790. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90497-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo XY, Balague C, Wang T, Randhawa G, Yuan Z, Bachier C, Greenberger J, Arlinghaus R, Kufe D, Deisseroth AB. 1999. The presence of the Rb c-box peptide in the cytoplasm inhibits p210bcr-abl transforming function. Oncogene 18:1589–1595. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macdonald JI, Dick FA. 2012. Posttranslational modifications of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein as determinants of function. Genes Cancer 3:619–633. 10.1177/1947601912473305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knudsen ES, Wang JY. 1996. Differential regulation of retinoblastoma protein function by specific Cdk phosphorylation sites. J. Biol. Chem. 271:8313–8320. 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McWhirter JR, Galasso DL, Wang JY. 1993. A coiled-coil oligomerization domain of Bcr is essential for the transforming function of Bcr-Abl oncoproteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:7587–7595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hantschel O, Nagar B, Guettler S, Kretzschmar J, Dorey K, Kuriyan J, Superti-Furga G. 2003. A myristoyl/phosphotyrosine switch regulates c-Abl. Cell 112:845–857. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00191-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brasher BB, Van Etten RA. 2000. c-Abl has high intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity that is stimulated by mutation of the Src homology 3 domain and by autophosphorylation at two distinct regulatory tyrosines. J. Biol. Chem. 275:35631–35637. 10.1074/jbc.M005401200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi Y, Alin K, Goff SP. 1995. Abl-interactor-1, a novel SH3 protein binding to the carboxy-terminal portion of the Abl protein, suppresses v-abl transforming activity. Genes Dev. 9:2583–2597. 10.1101/gad.9.21.2583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai Z, Pendergast AM. 1995. Abi-2, a novel SH3-containing protein interacts with the c-Abl tyrosine kinase and modulates c-Abl transforming activity. Genes Dev. 9:2569–2582. 10.1101/gad.9.21.2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren R, Ye ZS, Baltimore D. 1994. Abl protein-tyrosine kinase selects the Crk adapter as a substrate using SH3-binding sites. Genes Dev. 8:783–795. 10.1101/gad.8.7.783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexandropoulos K, Baltimore D. 1996. Coordinate activation of c-Src by SH3- and SH2-binding sites on a novel p130Cas-related protein, Sin. Genes Dev. 10:1341–1355. 10.1101/gad.10.11.1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Filippakopoulos P, Kofler M, Hantschel O, Gish GD, Grebien F, Salah E, Neudecker P, Kay LE, Turk BE, Superti-Furga G, Pawson T, Knapp S. 2008. Structural coupling of SH2-kinase domains links Fes and Abl substrate recognition and kinase activation. Cell 134:793–803. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welch PJ, Wang JY. 1995. Disruption of retinoblastoma protein function by coexpression of its C pocket fragment. Genes Dev. 9:31–46. 10.1101/gad.9.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mendoza MC. 2013. Phosphoregulation of the WAVE regulatory complex and signal integration. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 24:272–279. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bisi S, Disanza A, Malinverno C, Frittoli E, Palamidessi A, Scita G. 2013. Membrane and actin dynamics interplay at lamellipodia leading edge. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 25:565–573. 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woodring PJ, Hunter T, Wang JY. 2003. Regulation of F-actin-dependent processes by the Abl family of tyrosine kinases. J. Cell Sci. 116:2613–2626. 10.1242/jcs.00622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rotty JD, Wu C, Bear JE. 2013. New insights into the regulation and cellular functions of the ARP2/3 complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14:7–12. 10.1038/nrm3492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanos B, Pendergast AM. 2006. Abl tyrosine kinase regulates endocytosis of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 281:32714–32723. 10.1074/jbc.M603126200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yogalingam G, Pendergast AM. 2008. Abl kinases regulate autophagy by promoting the trafficking and function of lysosomal components. J. Biol. Chem. 283:35941–35953. 10.1074/jbc.M804543200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hebron ML, Lonskaya I, Moussa CE. 2013. Tyrosine kinase inhibition facilitates autophagic SNCA/alpha-synuclein clearance. Autophagy 9:1249–1250. 10.4161/auto.25368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang Y, Comiskey EO, Dupree RS, Li S, Koleske AJ, Burkhardt JK. 2008. The c-Abl tyrosine kinase regulates actin remodeling at the immune synapse. Blood 112:111–119. 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perez de Arce K, Varela-Nallar L, Farias O, Cifuentes A, Bull P, Couch BA, Koleske AJ, Inestrosa NC, Alvarez AR. 2010. Synaptic clustering of PSD-95 is regulated by c-Abl through tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. 30:3728–3738. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2024-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swimm A, Bommarius B, Li Y, Cheng D, Reeves P, Sherman M, Veach D, Bornmann W, Kalman D. 2004. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli use redundant tyrosine kinases to form actin pedestals. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:3520–3529. 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baskaran R, Dahmus ME, Wang JY. 1993. Tyrosine phosphorylation of mammalian RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:11167–11171. 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buratowski S. 2003. The CTD code. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:679–680. 10.1038/nsb0903-679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mayer A, Heidemann M, Lidschreiber M, Schreieck A, Sun M, Hintermair C, Kremmer E, Eick D, Cramer P. 2012. CTD tyrosine phosphorylation impairs termination factor recruitment to RNA polymerase II. Science 336:1723–1725. 10.1126/science.1219651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaidi A, Jackson SP. 2013. KAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation couples chromatin sensing to ATM signalling. Nature 498:70–74. 10.1038/nature12201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63.Jiang Z, Kamath R, Jin S, Balasubramani M, Pandita TK, Rajasekaran B. 2011. Tip60-mediated acetylation activates transcription independent apoptotic activity of Abl. Mol. Cancer 10:88. 10.1186/1476-4598-10-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baskaran R, Wood LD, Whitaker LL, Canman CE, Morgan SE, Xu Y, Barlow C, Baltimore D, Wynshaw-Boris A, Kastan MB, Wang JY. 1997. Ataxia telangiectasia mutant protein activates c-Abl tyrosine kinase in response to ionizing radiation. Nature 387:516–519. 10.1038/387516a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shafman T, Khanna KK, Kedar P, Spring K, Kozlov S, Yen T, Hobson K, Gatei M, Zhang N, Watters D, Egerton M, Shiloh Y, Kharbanda S, Kufe D, Lavin MF. 1997. Interaction between ATM protein and c-Abl in response to DNA damage. Nature 387:520–523. 10.1038/387520a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu W, Wu J, Xiao L, Bai Y, Qu A, Zheng Z, Yuan Z. 2012. Regulation of neuronal cell death by c-Abl-Hippo/MST2 signaling pathway. PLoS One 7:e36562. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y. 2008. Yap1 phosphorylation by c-Abl is a critical step in selective activation of proapoptotic genes in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell 29:350–361. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matsumura S, Hamasaki M, Yamamoto T, Ebisuya M, Sato M, Nishida E, Toyoshima F. 2012. ABL1 regulates spindle orientation in adherent cells and mammalian skin. Nat. Commun. 3:626. 10.1038/ncomms1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Vries RL, Przedborski S. 2013. Mitophagy and Parkinson's disease: be eaten to stay healthy. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 55:37–43. 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ko HS, Lee Y, Shin JH, Karuppagounder SS, Gadad BS, Koleske AJ, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. 2010. Phosphorylation by the c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase inhibits parkin's ubiquitination and protective function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:16691–16696. 10.1073/pnas.1006083107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qiu Z, Cang Y, Goff SP. 2010. Abl family tyrosine kinases are essential for basement membrane integrity and cortical lamination in the cerebellum. J. Neurosci. 30:14430–14439. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2861-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chislock EM, Ring C, Pendergast AM. 2013. Abl kinases are required for vascular function, Tie2 expression, and angiopoietin-1-mediated survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:12432–12437. 10.1073/pnas.1304188110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gu JJ, Lavau CP, Pugacheva E, Soderblom EJ, Moseley MA, Pendergast AM. 2012. Abl family kinases modulate T cell-mediated inflammation and chemokine-induced migration through the adaptor HEF1 and the GTPase Rap1. Sci. Signal. 5:ra51. 10.1126/scisignal.2002632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gu JJ, Ryu JR, Pendergast AM. 2009. Abl tyrosine kinases in T-cell signaling. Immunol. Rev. 228:170–183. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00751.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cleary RA, Wang R, Wang T, Tang DD. 2013. Role of Abl in airway hyperresponsiveness and airway remodeling. Respir. Res. 14:105. 10.1186/1465-9921-14-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Innocenzi A, Latella L, Messina G, Simonatto M, Marullo F, Berghella L, Poizat C, Shu CW, Wang JY, Puri PL, Cossu G. 2011. An evolutionarily acquired genotoxic response discriminates MyoD from Myf5, and differentially regulates hypaxial and epaxial myogenesis. EMBO Rep. 12:164–171. 10.1038/embor.2010.195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Imam SZ, Trickler W, Kimura S, Binienda ZK, Paule MG, Slikker W, Jr, Li S, Clark RA, Ali SF. 2013. Neuroprotective efficacy of a new brain-penetrating C-Abl inhibitor in a murine Parkinson's disease model. PLoS One 8:e65129. 10.1371/journal.pone.0065129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sridevi P, Nhiayi MK, Wang JY. 2013. Genetic disruption of Abl nuclear import reduces renal apoptosis in a mouse model of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Cell Death Differentiation 20:953–962. 10.1038/cdd.2013.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takao N, Mori R, Kato H, Shinohara A, Yamamoto K. 2000. c-Abl tyrosine kinase is not essential for ataxia telangiectasia mutated functions in chromosomal maintenance. J. Biol. Chem. 275:725–728. 10.1074/jbc.275.2.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang JY, Cho SK. 2004. Coordination of repair, checkpoint, and cell death responses to DNA damage. Adv. Protein Chem. 69:101–135. 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)69004-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ryoo HD, Bergmann A. 2012. The role of apoptosis-induced proliferation for regeneration and cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4:a008797. 10.1101/cshperspect.a008797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xu J, Escamilla J, Mok S, David J, Priceman S, West B, Bollag G, McBride W, Wu L. 2013. CSF1R signaling blockade stanches tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells and improves the efficacy of radiotherapy in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 73:2782–2794. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hikisz P, Kilianska ZM. 2012. PUMA, a critical mediator of cell death—one decade on from its discovery. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 17:646–669. 10.2478/s11658-012-0032-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]