Abstract

Cryptococcus neoformans, a pathogenic yeast, causes meningoencephalitis, especially in immunocompromised patients, leading in some cases to death. Microbes in biofilms can cause persistent infections, which are harder to treat. Cryptococcal biofilms are becoming common due to the growing use of brain valves and other medical devices. Using shotgun proteomics we determine the differences in protein abundance between biofilm and planktonic cells. Applying bioinformatic tools, we also evaluated the metabolic pathways involved in biofilm maintenance and protein interactions. Our proteomic data suggest general changes in metabolism, protein turnover, and global stress responses. Biofilm cells show an increase in proteins related to oxidation–reduction, proteolysis, and response to stress and a reduction in proteins related to metabolic process, transport, and translation. An increase in pyruvate-utilizing enzymes was detected, suggesting a shift from the TCA cycle to fermentation-derived energy acquisition. Additionally, we assign putative roles to 33 proteins previously categorized as hypothetical. Many changes in metabolic enzymes were identified in studies of bacterial biofilm, potentially revealing a conserved strategy in biofilm lifestyle.

Keywords: Cryptococcus neoformans, biofilm, shotgun proteomics, metabolic changes, resistance

Introduction

Cryptococcosis is one of the most important systemic mycoses and is considered to be one of the three common opportunistic infections in HIV/AIDS patients, causing almost 625 000 deaths per year worldwide.1 The importance of cryptococcosis as an opportunistic pathogenic fungus has increased considerably over the last decades due to the intensive chemotherapy of cancer patients, the use of immunosuppressive drugs in organ transplant recipients, and the spread of the AIDS epidemic.2 This potentially fatal fungal disease is caused by two species of the same genus: Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii.3,4

C. neoformans is an encapsulated opportunistic yeast-like fungus that causes meningoencephalitis in mammalian hosts, mainly in immunocompromised and sometimes in healthy individuals.5−7 Infection in humans and other susceptible animals occurs by inhalation, establishing a lung infection. To cause central nervous system (CNS) mycosis, C. neoformans becomes blood borne and progresses through until it culminates in fungal replication in the brain. Critical steps include fungal arrest in the vasculature of the brain and interaction and signaling of the fungal and endothelial cells, leading to transmigration with subsequent parenchymal invasion and fungal replication in the CNS.8−10

An ecological strategy that has been associated with chronic infections for several microorganisms, including Cryptococcus, is the formation of biofilm.6,11−13 It has been estimated that 65% of all human infectious diseases are biofilm-related.14C. neoformans can form biofilms on medical devices, including ventriculoatrial shunt catheters, peritoneal dialysis fistula, cardiac valves, and prosthetic joints.15−18 Microorganisms growing in biofilms exhibit high resistance to the host immune response, environmental stresses, and antimicrobial therapy. These persistent populations can serve as a reservoir for chronic and systemic infections, playing an important role in human disease.19,20 This increased resistance suggests that cells in biofilms can modulate metabolic activity, dormancy, and stress responses,21,22 which highlights the importance of understanding the biofilm-forming properties of C. neoformans.

Comparative analysis of the proteomes of several bacterial and fungal pathogens between biofilm and planktonic growth modes has been reported.23−28 By studying biofilm formation in C. neoformans, we hope to identify general features and specific characteristics of biofilms.

With the increasing recognition of the role that C. neoformans biofilms play during infection, strategies such as functional genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics can help us to gain insight into resistance, antifungal drug targets, and host–pathogen interaction.10,29 However, information regarding the molecular mechanisms specifically associated with the biofilm formation remains limited. These approaches could provide a framework for the identification of new proteins and pathways associated with fungal pathogenesis and maintenance.

Here we report the use of shotgun proteomics for comparative analysis of protein expression obtained from biofilm and planktonic cells of C. neoformans H99. Also, an interactome analysis revealed differences in protein networks. The changes in protein expression in the biofilm revealed important insights related to energy acquisition, under an oxygen-limiting condition, as indicated by the metabolic pathways analyses, linking the resistance to a persistent infective behavior, a feature also seen in bacterial biofilms.

Material and Methods

Fungal Strain and Growth Conditions

Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii, strain H99 (serotype A) was kindly provided by Dr. Marilene H. Vainstein (Biotechnology Center, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, RS, Brazil). The yeast was grown in 50 mL of yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) broth (yeast extract 1%, peptone 1%, glucose 2%) for 20 h, 180 rpm. Cells were separated by centrifugation and washed twice with phosphate-saline buffer (PBS) (10 mM phosphate buffer, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, 137 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.4). The cells were suspended in minimum medium (20 mg/mL thiamine, 30 mM glucose, 26 mM glycine, 20 mM MgSO4·0.7H2O, 58.8 mM KH2PO4)6 and adjusted to the desired cellular density (1 × 107 cells/mL) by counting in a Neubauer chamber. This standardized suspension was used as the inoculum to biofilm and planktonic cultures.

C. neoformans biofilms were cultured on Petri dishes containing 20 mL of minimum medium. The plates were maintained in an incubator chamber without shaking for 48 h at 37 °C. After this time, the plates were washed with PBS to remove unattached cells. Then, the resulting biofilm was scraped off the Petri dishes with PBS, transferred to tubes and centrifuged (15 min, 13 000 rpm). For planktonic culture, cells were grown for 48 h at 37 °C with shaking (180 rpm) in 50 mL of minimum medium, and the cells were separated by centrifugation. Both cell pellets were washed twice with PBS, frozen at −80 °C, and lyophilized.

Preparation of Protein Extracts

The lyophilized cells were disrupted with a mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen to a fine powder, and the samples were suspended in buffer with protease inhibitors (50 mM tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 50 μM TPCK, 5 mM iodoacetamide).30 Proteins were solubilized by vortexing five times for 1 min each at intervals of 1 min on ice and centrifuged (13 000 rpm for 20 min). Supernatants were collected, and the remaining cell debris were suspended in the same buffer, followed by the same protocol. Supernatants collected after centrifugation were pooled and stored at −80 °C. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry

C. neoformans H99 biofilm and planktonic protein extracts (100 μg) were suspended in digestion buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM tris-HCl pH 8.5). Proteins were reduced with 5 mM tris-2-carboxyethyl-phosphine (TCEP) at room temperature for 20 min and alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. After the addition of 1 mM CaCl2 (final concentration), the proteins were digested with 2 μg of trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) by incubation at 37 °C during 16 h. Proteolysis was stopped by adding formic acid to a final concentration of 5%. Samples were centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected and stored at −80 °C.

MudPIT

The protein digest was pressure-loaded into a 250 μm i.d. capillary packed with 2.5 cm of 5 μm Luna strong cation exchanger (SCX) (Whatman, USA), followed by 2 cm of 3 μm Aqua C18 reversed phase (RP) (Phenomenex, USA) with a 1 μm frit. The column was washed with buffer containing 95% water, 5% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid. After washing, a 100 μm i.d. capillary with a 5 μm pulled tip packed with 11 cm of 3 μm Aqua C18 resin (Phenomenex, USA) was attached via a union. The entire split-column was placed in line with an Agilent 1100 quaternary HPLC and analyzed using a modified 12-step separation as described previously.31 The buffer solutions used were 5% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (Buffer A), 80% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (Buffer B), and 500 mM ammonium acetate, 5% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid (Buffer C). Step 1 consisted of a 70 min gradient from 0–100% (v/v) buffer B. Steps 2–10 had a similar profile with the following changes: 3 min in 100% (v/v) buffer A, 3 min in X% (v/v) buffer C, 4 min gradient from 0 to 10% (v/v) buffer B, and 101 min gradient from 10–100% (v/v) buffer B. The 3 min buffer C percentages (X) were 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100% (v/v). An additional step containing 3 min in 100% (v/v) buffer A, 3 min in 90% (v/v) buffer C and 10% (v/v) buffer B, and 110 min gradient from 10–100% (v/v) buffer B were used. Three pools of six biological replicates and two technical replicates were analyzed for both C. neoformans culture conditions (biofilm and planktonic).

Mass Spectrometry

Peptides eluted from the microcapillary column were electrosprayed directly into an LTQ-XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, USA) with the application of a distal 2.4 kV spray voltage. A cycle of one full-scan mass spectrum (300–2000 m/z) followed by five data-dependent MS/MS spectra at a 35% normalized collision energy was repeated continuously throughout each step of the multidimensional separation. To prevent repetitive analysis, dynamic exclusion was enabled with a repeat count of 1, a repeat duration of 30 s, and an exclusion list size of 200. Application of mass spectrometer scan functions and HPLC solvent gradients were controlled by the Xcalibur data system (Thermo, USA).

Analysis of Tandem Mass Spectra

MS/MS spectra were analyzed using the following software analysis protocol. Protein identification and quantification analysis were done with Integrated Proteomics Pipeline (www.integratedproteomics.com/). Tandem mass spectra were extracted into ms2 files from raw files using RawExtract 1.9.932 and were searched using ProLuCID algorithm33 against the C. neoformans H99 database from the Broad Institute (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/cryptococcus_neoformans_b/MultiDownloads.html, downloaded on August 8, 2012). The peptide mass search tolerance was set to 3 Da, and carboxymethylation (+57.02146 Da) of cysteine was considered to be a static modification. ProLuCID results were assembled and filtered using the DTASelect program34 using two SEQUEST35-defined parameters, the cross-correlation score (XCorr) and normalized difference in cross-correlation scores (DeltaCN), to achieve a false-positive rate (1%). The following parameters were used to filter the peptide candidates: -p 1 -y 1 --trypstat --fpf 0.01 -in, where (-p) means minimum number of peptide per protein, (-y) minimum number of tryptic end per peptide, (--trypstat) statistics with tryptic status, (--fpf) false-positive rate for protein, and (-in) subset proteins included.

Data Analysis

The software PatternLab36,37 was used to identify differentially expressed and exclusive proteins found in biofilm and planktonic conditions. Pairwise comparisons between both conditions were performed using spectral count data on an updated version of the PatternLab’s TFold module.38 This module was used to select differentially expressed proteins under biofilm and planktonic conditions. The following parameters were used: proteins that were not detected in at least four out of six runs per condition were not considered, using a q-value of 0.05 and an F-stringency of 0.1. Low-abundance proteins, those with low p-values and a significant fold change but low spectral count values, were removed using the L-stringency of 0.4. Also, an absolute fold change greater than two was used to select differently expressed proteins. PatternLab’s approximately area proportional Venn diagram (AAPV) module was used for pinpointing proteins uniquely identified under a condition using a probability 0.01.

The Blast2GO tool (http://www.blast2go.org)39 was used to categorize the proteins detected by Gene Ontology (GO) annotation40 according to biological process and molecular function. Additionally, the KEGG map module41 allowed the display of enzymatic functions in the context of the metabolic pathways in which those proteins participate.

To investigate the characteristics of hypothetical proteins identified for biofilm, we used bioinformatics tools. The TargetP 1.0 (cutoff >0.9)42 and TMHMM 2.043 were used to evaluate the subcellular location; SignalP 4.144 was used for prediction of secreted proteins (using cutoff default); ProtFun 2.245 was used for prediction of protein function, including cellular role, enzyme class, and Gene Ontology category; and HMMER 3.146 was used for searching sequence databases for homologues of protein sequences. TargetP, TMHMM, SignalP, and ProtFun programs are available at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/; HMMER is available at http://hmmer.janelia.org/.

Interaction Data Set

To construct an interface of our protein set with the known interactions for Cryptococcus neoformans, we downloaded from UniProt (www.uniprot.org) the file uniprot_sprot_fungi 01_13 release. We extracted the FASTA sequences using an in-house software tool. We downloaded from STRING47 the files proteins.links.detailed.v9.0.txt and protein.sequences.v9.0.fa.txt. We obtained the reference protein from STRING finding the closest sequence match to our protein set sequences.

Then, for every possible pair, an “ontological distance”48 was calculated considering the fraction of GO terms shared over the sum of distinct terms; the resulting score was then bounded between 0 and 1.

Network Maps and Visualization

We then parsed, using an in-house software tool, the STRING links file to extract the matching interaction. We then coupled the protein list with Gene Ontology40 to gather the ontological terms. We calculated the frequency of each term in our list, and we clustered the proteins in groups based on their association with a particular term.

We developed an in-house software tool to integrate all of the different pieces of information to obtain a network interactions list. Each interaction is not directional and is represented by the corresponding score in the interaction data set. Each node in the interactions list was assigned a color based on its value in the protein regulation data set ranging in a gradient from blue, for down-regulated values, to red, for up-regulated values. To visualize the network, we used the open-source Medusa viewer.49

Validation of Proteomic Analysis

Catalase activity was assayed using hydrogen peroxide as substrate.50 Phosphate buffer was added along with H2O2 10 mM to 25 mL sample aliquots. Catalase activity was estimated by the decrease in absorbance of H2O2 at 240 nm for 3 min. The decomposition of H2O2 was followed at 240 nm (E = 39.4 mm cm–1).

The assay for superoxide dismutase (SOD) was conducted as previously described.50 A solution containing 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.8, 13 mM l-methionine, 75 mM NBT (nitro blue tetrazolium), 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.025% Triton X-100 was added to glass tubes. To start the reactions, we added the sample and 10 mM riboflavin at the same time that tubes were placed under fluorescent light for 15 min. After this period, absorbance was determined at 560 nm. SOD unit was defined by NBT reduction per mL h–1.

Alanine aminotransferase assay was performed using TGP transaminase kit according to manufacturer instructions (Bioclin, Brazil).

Peptidase activity assays were tested upon chromogenic substrates: SF-17 (Bz-Phe-Val-Arg-ρNA; chymotrypsin/trypsin substrate), S2238 (H-d-Phe-Pip-Arg-ρNA; thrombin substrate), and S2251 (H-d-Val-Leu-Lys-ρNA; plasmin substrate), as previously described.51 Ten microliters of samples was incubated in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4. The reactions were initiated by adding substrates at 0.2 mM (final concentration) in a final volume of 100 μL. Kinetic assays were monitored at 37 °C for 30 min in a SpectraMax spectrophotometer equipped with thermostat and shaking systems. One protease unit (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme that produces one ρmol of ρ-nitroaniline per min per protein under the assay conditions described.

Phosphatase activity was measured by the rate of ρ-nitrophenol (ρ-NP) production.52 Samples (10 μL) were incubated for 60 min at room temperature in 0.2 mL of reaction mixture containing 116.0 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 30.0 mM HEPES-Tris buffer pH 7.0, and 5.0 mM ρ-nitrophenylphosphate (ρ-NPP) as substrate. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.2 mL of 20% trichloroacetic acid. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was centrifuged at 1500g for 15 min at 25 °C. The absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 405 nm using a microplate reader SpectraMax (Molecular Devices, USA). The concentration of released ρ-nitrophenolate in the reaction was determined using a standard curve of ρ-nitrophenolate for comparison.

Western blot was also used to validate the proteomic data. In brief, 20 μg of C. neoformans biofilm and planktonic proteins was separated by 4–20% Bis-tris gel (Invitrogen, CA) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, MA). Heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) (70 kDa) was detected with monoclonal antimouse antibody (1:1000 dilution). The secondary antibody (1:10.000) conjugated with HRP was detected using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo, IL).

Statistical Analysis

All enzymatic assays were performed in triplicate. Data generated from enzymatic activities were analyzed statistically using the Student’s t test and GraphPad Prism 5 software.

Results

MudPIT Identification

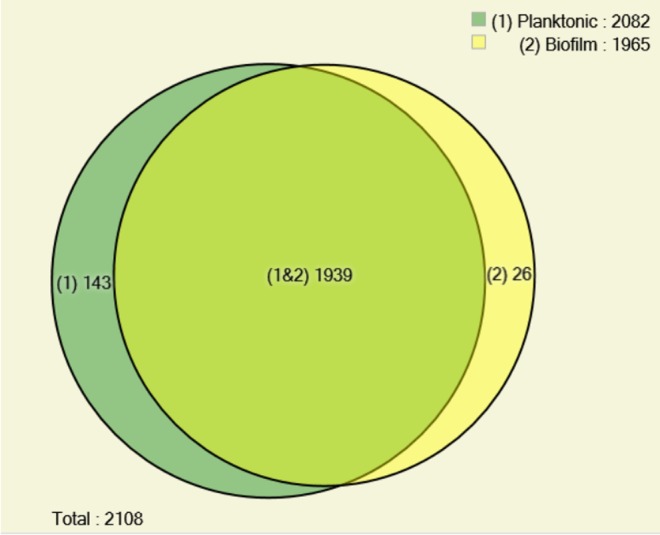

A total of 1965 proteins were identified from the biofilm and 2082 were identified from the planktonic condition according to maximum parsimony (Figure 1). The majority of those proteins were common to both conditions (1939), while 143 (6.78%) were identified only in planktonic cells and 26 (1.23%) were exclusive to cells growing in biofilm. All proteins identified in this research are listed in Table S1 and S2 (Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Cryptococcus neoformans H99 proteins obtained under biofilm and planktonic condition. Venn diagram shows the dispersion of total proteins identified under both conditions, according PatternLab’s AAPV module, using 0.01 probability.

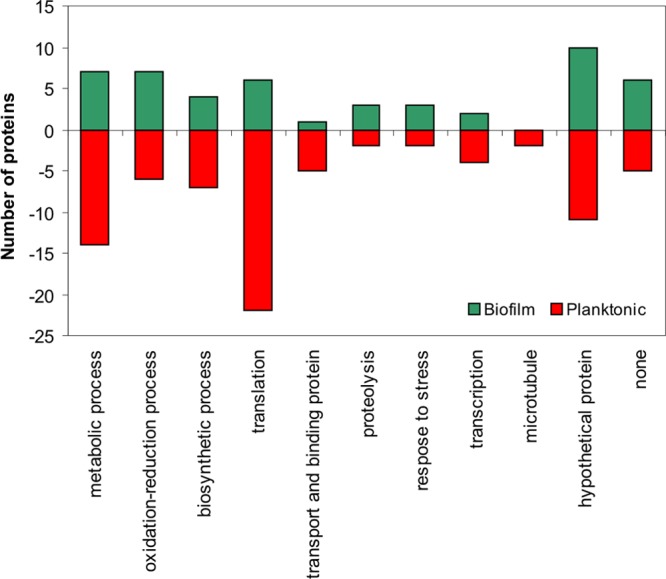

A total of 50 proteins were identified up- and 81 down-regulated in biofilm mode of growth (Table 1). The proteins that were up-regulated by more than two-fold included those related to oxidation–reduction (oxidoreductase), proteolysis (peptidases), and response to stress (catalase, glutathione-disulfide reductase, HSP70), and the down-regulated proteins were related to translation, transport and binding, transcription, and microtubule (Figure 2). We identified an aminotransferase with the highest differential expression (17.47 fold up-regulated) followed by lactoylglutathione lyase (15.4 fold), which is related to pyruvate metabolism and detoxification, and an uricase (15.28 fold) associated with uric acid degradation (Table 1). The most down-regulated protein was aldehyde dehydrogenase (−51.09 fold), an enzyme responsible for the oxidation of aldehyde to carboxylic acid. Isocitrate lyase was down-regulated 26.75-fold and has function in the TCA cycle. Several ribosomal proteins were also down-regulated (Table 1).

Table 1. Proteins Identified of Cryptococcus neoformans H99 That Are Differentially Expressed under Biofilm and Planktonic Conditiona.

| accession numberb | fold changec | p value | protein name |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNAG_02852T0 | 17.47 | 0.00094 | aminotransferase |

| CNAG_04219T0 | 15.40 | 0.000119 | lactoylglutathione lyase |

| CNAG_04307T0 | 15.28 | 0.012617 | uricase |

| CNAG_01542T0 | 9.49 | 0.000858 | taurine catabolism dioxygenase TauD |

| CNAG_03144T0 | 7.83 | 0.016609 | protein-methionine-S-oxide reductase |

| CNAG_00457T0 | 6.71 | 0.000821 | glutamine synthetase |

| CNAG_02714T0 | 6.63 | 0.008066 | elongation factor 1-beta |

| CNAG_02399T0 | 6.55 | 1.46 × 10–05 | glutathione-disulfide reductase |

| CNAG_00848T0 | 5.80 | 0.001169 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_02754T0 | 5.53 | 0.049673 | 40S ribosomal protein S12 |

| CNAG_03677T0 | 5 | 0.018703 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_07559T0 | 4.91 | 0.003652 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_01686T0 | 4.54 | 0.000938 | ThiJ/PfpI |

| CNAG_03482T0 | 4.38 | 0.013805 | thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase |

| CNAG_04269T0 | 4.37 | 0.008231 | peptidase |

| CNAG_05638T0 | 4.32 | 0.039603 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_05256T0 | 4.25 | 0.029929 | catalase |

| CNAG_01375T0 | 4.08 | 0.004133 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_03509T0 | 4.04 | 0.022818 | pyruvate dehydrogenase protein X component |

| CNAG_02202T0 | 3.84 | 0.021764 | adenylyl-sulfate kinase |

| CNAG_04799T0 | 3.64 | 0.035322 | ribosomal protein L14 |

| CNAG_06302T0 | 3.53 | 0.012183 | PEP2 |

| CNAG_02076T0 | 3.49 | 0.002241 | leukotriene-A4 hydrolase |

| CNAG_01577T0 | 3.48 | 0.005951 | glutamate dehydrogenase |

| CNAG_07801T0 | 3.36 | 0.010318 | aldo-keto reductase |

| CNAG_06443T0 | 3.22 | 0.042654 | heat shock protein 70 |

| CNAG_01558T0 | 3.14 | 0.004449 | zinc-binding dehydrogenase |

| CNAG_07522T0 | 3.08 | 0.001507 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_04760T0 | 3 | 0.007741 | cytoplasmic protein |

| CNAG_07771T0 | 3 | 0.003527 | peptidase |

| CNAG_02568T0 | 2.94 | 0.005715 | UBA/TS-N domain-containing protein |

| CNAG_01341T0 | 2.92 | 0.037823 | mannose-6-phosphate isomerase |

| CNAG_06226T0 | 2.92 | 0.027042 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_02099T0 | 2.90 | 0.00182 | fatty acid synthase beta subunit |

| CNAG_07362T0 | 2.79 | 0.015629 | single-stranded DNA binding protein |

| CNAG_04441T0 | 2.66 | 0.006413 | polyadenylate-binding protein |

| CNAG_01168T0 | 2.64 | 0.000321 | centromere/microtubule binding protein cbf5 |

| CNAG_00238T0 | 2.64 | 0.020937 | isoleucine-tRNA ligase |

| CNAG_04604T0 | 2.53 | 0.032385 | tryptophan-tRNA ligase |

| CNAG_01557T0 | 2.5 | 0.039665 | calmodulin 1b |

| CNAG_03705T0 | 2.48 | 0.024666 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_01138T0 | 2.48 | 0.028101 | cytochrome c peroxidase |

| CNAG_02726T0 | 2.39 | 0.041969 | cytoplasmic protein |

| CNAG_00483T0 | 2.33 | 0.017333 | actin |

| CNAG_02843T0 | 2.28 | 0.034824 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_05521T0 | 2.2 | 0.022853 | aldose reductase |

| CNAG_05602T0 | 2.19 | 0.010051 | 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase |

| CNAG_03463T0 | 2.17 | 0.011508 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_00100T0 | 2.16 | 0.015629 | chaperone |

| CNAG_01102T0 | 2.11 | 0.016887 | oxidoreductase |

| CNAG_05900T0 | –2.07 | 0.01048 | glycine-tRNA ligase |

| CNAG_04209T0 | –2.17 | 0.017508 | voltage-gated potassium channel beta-2 subunit |

| CNAG_04601T0 | –2.22 | 0.021853 | glycine hydroxymethyltransferase |

| CNAG_03320T0 | –2.26 | 0.014593 | mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase |

| CNAG_04904T0 | –2.3 | 0.029246 | clathrin heavy chain 1 |

| CNAG_06474T0 | –2.38 | 0.019719 | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein HRP1 |

| CNAG_02100T0 | –2.39 | 0.007817 | fatty-acid synthase complex protein |

| CNAG_00785T0 | –2.39 | 0.005589 | translation initiation factor |

| CNAG_02966T0 | –2.45 | 0.032411 | carboxypeptidase D |

| CNAG_04114T0 | –2.52 | 0.004251 | 40S ribosomal protein S0 |

| CNAG_06900T0 | –2.61 | 0.002331 | phosphoglycerate mutase |

| CNAG_06866T0 | –2.64 | 0.000455 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_01839T0 | –2.71 | 0.046983 | transcriptional elongation regulator |

| CNAG_04009T0 | –2.72 | 0.005826 | leucyl aminopeptidase |

| CNAG_06935T0 | –2.73 | 0.025741 | isochorismatase hydrolase |

| CNAG_01480T0 | –2.77 | 0.00208 | 60S ribosomal protein L12 |

| CNAG_03007T0 | –2.78 | 0.000187 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_06113T0 | –2.85 | 0.021278 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_05689T0 | –2.90 | 0.029962 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_06511T0 | –2.96 | 0.012872 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_01890T0 | –3.12 | 0.037097 | 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine S-methyltransferase |

| CNAG_06123T0 | –3.17 | 0.011257 | leucine-tRNA ligase |

| CNAG_02489T0 | –3.19 | 0.012336 | mannitol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| CNAG_02903T0 | –3.21 | 0.037052 | zinc-type alcohol dehydrogenase |

| CNAG_04105T0 | –3.21 | 0.00296 | hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_06231T0 | –3.3 | 0.001301 | ribosomal protein L13A |

| CNAG_00370T0 | –3.33 | 0.011699 | ubiquitin-carboxy extension protein fusion |

| CNAG_05907T0 | –3.37 | 2.19 × 10–05 | pyruvate carboxylase |

| CNAG_00565T0 | –3.4 | 0.000322 | VpsA |

| CNAG_00130T0 | –3.61 | 0.000951 | CAMK/CAMK1 protein kinase |

| CNAG_06150T0 | –3.61 | 0.000726 | heat-shock protein 90 |

| CNAG_05886T0 | –3.63 | 0.006982 | ubiquitin conjugating enzyme MmsB |

| CNAG_04621T0 | –3.68 | 0.001533 | glycogen synthase |

| CNAG_01164T0 | –3.75 | 0.030316 | glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate transaminase |

| CNAG_03787T0 | –3.78 | 0.021767 | alpha tubulin |

| CNAG_00797T0 | –3.79 | 0.021688 | acetate-CoA ligase |

| CNAG_05555T0 | –3.85 | 0.00402 | ribosomal protein L4 |

| CNAG_02335T0 | –3.91 | 0.002194 | UPF0364 protein |

| CNAG_00393T0 | –4 | 0.013943 | 1,4-alpha-glucan-branching enzyme |

| CNAG_07346T0 | –4 | 0.003779 | t-complex protein 1 |

| CNAG_05650T0 | –4.02 | 0.015088 | ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 5 |

| CNAG_04652T0 | –4.02 | 0.018038 | enoyl reductase |

| CNAG_00147T0 | –4.06 | 0.03385 | splicing factor Prp8 |

| CNAG_02118T0 | –4.12 | 0.005713 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_04388T0 | –4.66 | 0.000207 | mitochondrial superoxide dismutase Sod2 |

| CNAG_03641T0 | –4.67 | 0.008395 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit 7 |

| CNAG_06235T0 | –4.70 | 0.002397 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_04640T0 | –4.88 | 9.29 × 10–05 | acyl protein |

| CNAG_06125T0 | –4.88 | 4.94 × 10–05 | translation elongation factor 1 alpha |

| CNAG_00821T0 | –5.06 | 0.031574 | 60s ribosomal protein l34-b |

| CNAG_03780T0 | –5.21 | 0.001024 | prcdna95 |

| CNAG_00640T0 | –5.49 | 0.024398 | 40s ribosomal protein |

| CNAG_04066T0 | –5.63 | 0.040426 | endoribonuclease L-PSP |

| CNAG_01884T0 | –5.86 | 0.012792 | large subunit ribosomal protein L3 |

| CNAG_02585T0 | –6.7 | 0.013335 | RfeF |

| CNAG_07316T0 | –6.82 | 0.00049 | alcohol dehydrogenase |

| CNAG_01870T0 | –6.82 | 0.005086 | mitochondrial protein |

| CNAG_07347T0 | –6.93 | 0.000969 | heat shock protein |

| CNAG_01486T0 | –7.48 | 0.011999 | 60S ribosomal protein L15b |

| CNAG_07746T0 | –7.52 | 0.007699 | methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (NADP) |

| CNAG_04068T0 | –7.53 | 0.014164 | 60s ribosomal protein |

| CNAG_00678T0 | –7.67 | 0.002351 | urease accessory protein ureG |

| CNAG_03010T0 | –7.76 | 0.000503 | enoyl-CoA hydratase/isomerase family protein |

| CNAG_01794T0 | –7.93 | 0.015624 | 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase |

| CNAG_04445T0 | –8.34 | 0.013355 | 40S ribosomal protein S7 |

| CNAG_02129T0 | –9.13 | 0.000584 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_05251T0 | –9.33 | 0.000166 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_03048T0 | –9.73 | 0.047775 | cytoplasmic protein |

| CNAG_07862T0 | –10 | 0.000122 | fumarate reductase |

| CNAG_01840T0 | –11.10 | 0.03059 | beta1-tubulin |

| CNAG_05232T0 | –12.83 | 0.003691 | ribosomal protein L8 |

| CNAG_00012T0 | –13.08 | 0.012064 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| CNAG_00747T0 | –13.64 | 3.23 × 10–05 | succinate-CoA ligase |

| CNAG_01224T0 | –14.48 | 0.002602 | ribosomal protein L18.e |

| CNAG_06605T0 | –16.25 | 0.006007 | ribosomal protein S2 |

| CNAG_05721T0 | –16.95 | 0.004036 | peroxisomal hydratase-dehydrogenase-epimerase |

| CNAG_00116T0 | –18.89 | 1.00 × 10–05 | ribosomal protein S3 |

| CNAG_00490T0 | –21.43 | 0.006986 | acetyl-CoA C-acyltransferase |

| CNAG_05303T0 | –26.75 | 0.000987 | isocitrate lyase |

| CNAG_00656T0 | –32.32 | 1.00 × 10–05 | 60s ribosomal protein l7 |

| CNAG_06628T0 | –51.09 | 0.00014 | aldehyde dehydrogenase |

Proteins listed in this Table were found to be statistically differentially expressed using PatternLab’s Tfold module with an absolute fold change greater than 2.0 (BH-FDR 0.05).

According to Broad Institute ID.

Based on spectral count numbers obtained from biofilm and planktonic. Negative numbers represent down-regulated proteins in biofilm compared with planktonic condition.

Figure 2.

Plot of the biological processes classification of all up- and down-regulated proteins in the biofilm of Cryptococcus neoformans H99 compared with the planktonic mode of growth. All of the tabulated proteins met a two-fold cutoff threshold for differential expression.

Among the 26 proteins uniquely identified in biofilm, we identified proteins related to oxidative stress (Cu/ZN superoxide dismutase); acid phosphatase and two proteinases (Table 2). However, 46% of unique biofilm proteins were identified as conserved hypothetical, which were analyzed separately.

Table 2. Unique Proteins Identified in C. neoformans Biofilm.

| accession number | protein name | spec count |

|---|---|---|

| CNAG_01019T0 | Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase | 109 |

| CNAG_04236T0 | acid phosphatase | 42 |

| CNAG_01147T0 | ARP2/3 complex 20 kDa subunit | 33 |

| CNAG_04687T0 | stearoyl-CoA 9-desaturase | 27 |

| CNAG_00351T0 | predicted protein | 23 |

| CNAG_00668T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 21 |

| CNAG_02739T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 19 |

| CNAG_03926T0 | methionine aminopeptidase 1 | 19 |

| CNAG_06274T0 | hypothetical protein | 16 |

| CNAG_04914T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 13 |

| CNAG_02914T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 12 |

| CNAG_03589T0 | adrenodoxin-type ferredoxin | 12 |

| CNAG_04735T0 | extracellular elastinolytic metalloproteinase | 12 |

| CNAG_06589T0 | endoribonuclease L-PSP | 11 |

| CNAG_01650T0 | 60s ribosomal protein l7 | 10 |

| CNAG_01991T0 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit V | 10 |

| CNAG_04032T0 | ATPase | 10 |

| CNAG_01381T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 9 |

| CNAG_03361T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 9 |

| CNAG_04900T0 | WD40 protein Ciao1 variant | 9 |

| CNAG_06749T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 9 |

| CNAG_03228T0 | universal stress protein family domain-containing protein | 8 |

| CNAG_05573T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 8 |

| CNAG_04257T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 7 |

| CNAG_06817T0 | UAP1 | 7 |

| CNAG_06716T0 | conserved hypothetical protein | 5 |

Hypothetical Protein Analysis

A total of 33 proteins identified were classified as hypothetical in the differentially expressed and unique protein sets in the biofilm. These proteins were studied further to identify possible function and subcellular localization. Their sequences were BLASTed against the NCBI nonredundant database, and all proteins had a high similarity with other hypothetical proteins. Therefore, we used other bioinformatic tools to identify subcellular localization or other possible molecular functions of the proteins (Table 3). According to ProtFun, we could identify proteins related to metabolism, biosynthesis, regulatory function, replication and transcription, purine/pyrimidine, and translation. In the down-regulated hypothetical proteins, 50% were identified as belonging to translation; for the up-regulated hypothetical proteins, regulatory function and metabolic process comprise 60%. This result agreed with previous reports, where biofilm cells are growing slower and thus have a lower translation rate.21,22 According to HMMER program, proteins related to cytochrome c oxidase and RNA-recognizing motif were identified. Analyses of subcellular localization suggested that at least four proteins are present in or associated with the mitochondria (up-regulated and unique) and four proteins are possibly present in or associated with the transmembrane (only in biofilms) (Table 3). All proteins were considered unlikely to be secreted. The lack of similarity of these 33 pathogen-specific proteins with human proteins makes these good potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Table 3. Putative Classification and Localization of Cryptococcus neoformans H99 Hypothetical Proteins Identified As Differentially Regulated in Biofilmsa.

| acc. number | target P | signal P | TMHMM | ProtFun molecular function/enzyme class/GO | HMMER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-Regulated | |||||

| CNAG_03677T0 | N | amino acid biosynthesis/–/– | |||

| CNAG_07559T0 | N | amino acid biosynthesis/–/immune response | aldose 1-epimerase | ||

| CNAG_06226T0 | M | N | energy metabolism/–/growth factor | ETC complex I subunit conserved region | |

| CNAG_05638T0 | N | energy metabolism/lyase/- | dienelactone hydrolase family | ||

| CNAG_02843T0 | N | metabolism/–/growth factor | RNA recognition motif | ||

| CNAG_03705T0 | N | regulatory function/–/growth factor | eisosome component PIL1 | ||

| CNAG_07522T0 | N | regulatory function/–/transcription regulation | GDP/GTP exchange factor Sec2p | ||

| CNAG_01375T0 | N | regulatory function/–/transcription | cofilin/tropomyosin-type actin-binding and SH3 domain | ||

| CNAG_03463T0 | M | N | translation/–/transcription | eisosome component PIL1 | |

| CNAG_00848T0 | N | translation/ligase/growth factor | |||

| Down-Regulated | |||||

| CNAG_05689T0 | N | amino acid biosynthesis/lyase/growth factor | |||

| CNAG_00012T0 | N | central intermediary metabolism/–/– | oxidoreductase family, NAD-binding | ||

| CNAG_06235T0 | N | central intermediary metabolism/ligase/– | AdoMet dependent proline dimethyltransferase | ||

| CNAG_06511T0 | N | energy metabolism/lyase/– | short chain dehydrogenase | ||

| CNAG_02118T0 | N | replication and transcription/–/transcription regulation | |||

| CNAG_04105T0 | N | translation/–/– | |||

| CNAG_06113T0 | N | translation/-/growth factor | Stm1 and hyaluronan/mRNA binding family | ||

| CNAG_06866T0 | N | translation/-/transcription | |||

| CNAG_03007T0 | N | translation/-/transcription regulation | |||

| CNAG_05251T0 | N | translation/–/transcription regulation | |||

| CNAG_02129T0 | N | translation/ligase/– | |||

| Unique | |||||

| CNAG_06274T0 | N | TM | energy metabolism/–/transporter | cytochrome c oxidase copper chaperone | |

| CNAG_02914T0 | M | N | energy metabolism/lyase/structural | mitochondrial large subunit ribosomal protein | |

| CNAG_05573T0 | N | fatty acid metabolism/–/transcription regulation | cytochrome c oxidase copper chaperone | ||

| CNAG_06749T0 | N | metabolism/lyase/immune response | |||

| CNAG_00668T0 | N | TM | purine and pyrimidine/–/growth factor | ||

| CNAG_04257T0 | N | TM | purine and pyrimidine/–/growth factor | outer membrane protein TOM13 | |

| CNAG_00351T0 | N | regulatory function/–/growth factor | ARP2/3 complex 20 kDa subunit | ||

| CNAG_02739T0 | N | regulatory function/–/transcription regulation | fungal Zn(2)-Cys(6) binuclear cluster | ||

| CNAG_01381T0 | N | TM | translation/–/growth factor | 3′ exoribonuclease family, domain 1 | |

| CNAG_04914T0 | M | N | translation/–/structural | LSM domain | |

| CNAG_06716T0 | N | translation/–/transcription | RNA recognition motif | ||

| CNAG_03361T0 | N | translation/ligase/– | metallo-beta-lactamase superfamily |

Target P: (M) mitochondrial; Signal P: (N) no peptide signal; TMHMM: (TM) transmembrane.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Analysis

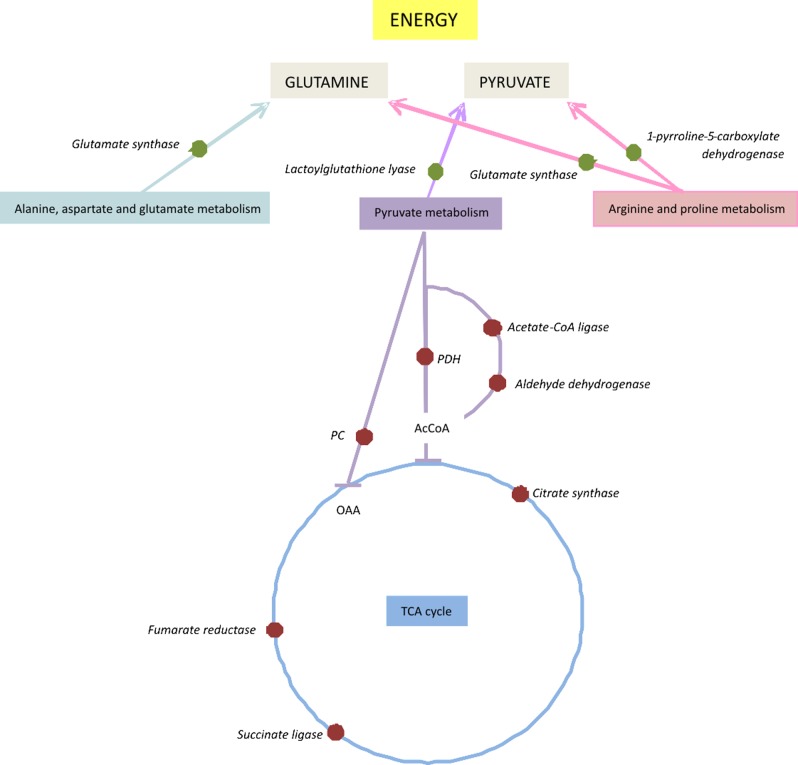

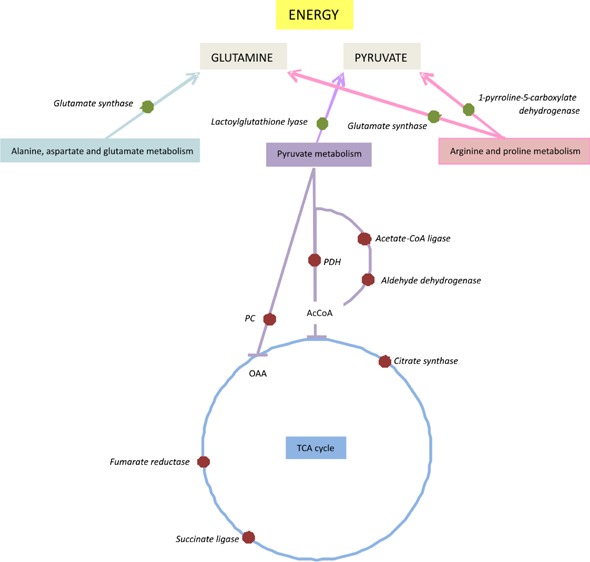

Recent works have indicated that bacterial biofilm cells have an active but altered metabolism.21,22,53 To identify pathways affected by fungal biofilm formation in C. neoformans, we analyzed the MudPIT results using KEGG pathways in the Blast2Go program. Forty-three different pathways were associated with proteins identified as differentially regulated (up- or down-regulated) in the biofilm. The following KEGG pathways had four hits each: pyruvate metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, citrate cycle (TCA cycle), glyoxalate metabolism, and methane metabolism. Some pathways were represented only by up-regulated proteins: alanine, glutathione, nitrogen, sulfur, and tryptophan metabolisms. Analyzing the results in a wider view, we could observe that pathways related to the TCA cycle (succinate CoA ligase), glycolysis and pyruvate metabolism (aldehyde dehydrogenase, pyruvate carboxylase) are down-regulated. However, the second most up-regulated enzyme, lactoylglutathione lyase (pyruvate metabolism), is involved in detoxification and formation of glutathione and lactate, suggesting that pyruvate is probably being used in energy metabolism via lactate fermentation. (Figure S1, S2, and S3 in the Supporting Information). Analyzing other metabolic pathways related to amino acid metabolism (Figure S4 in the Supporting Information), glutamine could be accumulated in biofilm. This compound could be used as a precursor for energy production. Figure 3 shows a schematic model proposed by C. neoformans biofilm for energy acquisition. The pathway related to glutathione metabolism (Figure S5 in the Supporting Information) shows that several enzymes are up-regulated, suggesting glutathione accumulation, which could be used for protection. The similarity of bacterial and fungal metabolic changes in biofilm growth hints at a common survival mechanism used by these distinct microbes.

Figure 3.

Schematic model of changes in metabolic regulation in biofilm cells of Cryptococcus neoformans H99 reveals a shift from the TCA cycle in energy acquisition. Red dots represent proteins down-regulated; green dots represent proteins up-regulated.

Validation

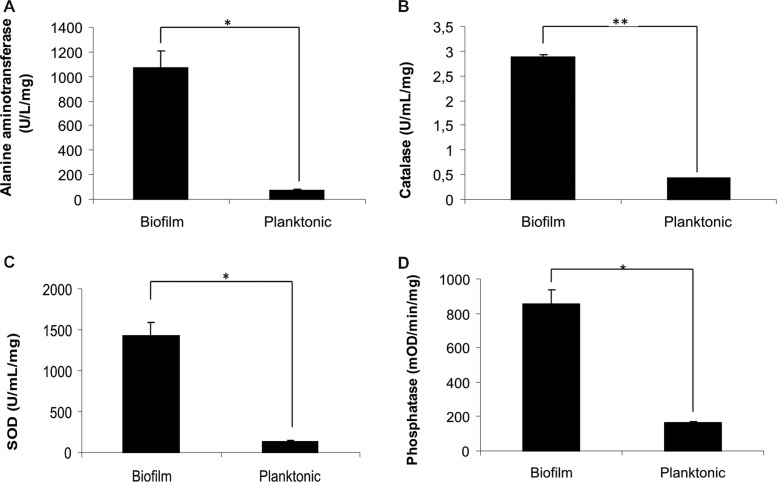

To validate the proteomic analysis, we performed enzymatic assays and Western blot. Alanine aminotransferase activity (Figure 4A) was measured to be increased 15-fold, consistent with the 17-fold difference in spectral counts. Similarly, catalase activity was increased seven-fold, with a four-fold difference in spectral counts (Figure 4B). The activity of two proteins (superoxide dismutase and phosphatase) uniquely identified in biofilm was measured. As expected, more activity was observed in the biofilm (Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Enzymatic assays of (A) alanine aminotransferase, (B) catalase, (C) superoxide dismutase, and (D) phosphatase of biofilm and planktonic cells of Cryptococcus neoformans H99 (*p < 0.001; **p < 0.005).

Protease assays were used to validate some measurements in the proteomic data. Multiple proteins identified as proteases were more abundant (at least three-fold) in biofilm (Table 1). To test cumulative protease activity, we measured the activity of lysates against three different synthetic substrates: related to coagulation (S2238), plasminogen degradation (S2251) and trypsin-like protease (SF-17). The activity was higher when C. neoformans was grown in biofilm as compared with planktonic, varying from 1.5- to 2.5-fold increase (Table 4) for all substrates evaluated consistent with the differences detected in protein level.

Table 4. Peptidase Activities of Protein Extracts of Cryptococcus neoformans Cells Growing in Biofilm or Planktonic Condition against Three Different Chromogenic Protease Substratesa.

| substrate | biofilm/planktonic activity (pmol/min/mL/mg) |

|---|---|

| SF-17 (Bz-Phe-Val-Arg-ρNA) | 2.5* |

| S2238 (H-d-Phe-Pip-Arg-ρNA) | 2.5* |

| S2251 (H-d-Val-Leu-Lys-ρNA) | 1.5** |

*p < 0.001, **p < 0.01.

Western blot was used to validate the HSP70 protein. As observed in the Figure S6 in the Supporting Information, the immunoblot showed greater detection in C. neoformans biofilm as compared with planktonic, with an increase of almost two-fold according to ImageJ program (data not shown).

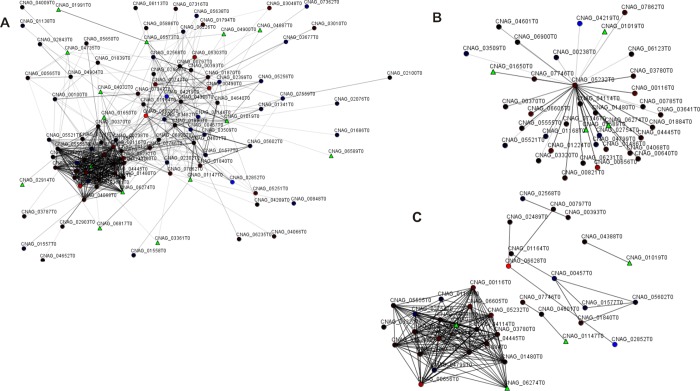

Protein Interaction Networks

To evaluate the network of those proteins identified uniquely and differentially expressed in the biofilm state, we generated protein interaction networks. Considering 157 proteins differentially expressed in biofilm, the interactome analysis revealed 105 protein–protein interactions (Figure 5). We observed that one protein represents a majority of connections: ribosomal protein L8 (CNAG_05323T0). This protein was identified down-regulated in the biofilm state and could interact with 37 other proteins, most of them down-regulated (Figure 5B). Among these 37 possible connections, several are ribosomal proteins and some are related to metabolic processes. Evaluating the network by score, that is, closest similarity in the ontological distance, we identified one important group, where the majority of proteins were related to ribosome assembly (Figure 5C). Two other proteins with high interaction scores were Cu/Zn SOD (CNAG_01019T0) and SOD 2 mitochondrial (CNAG_04388T0).

Figure 5.

Interactome of differentially expressed proteins identified in C. neoformans H99 biofilms. Spheres and triangles represent proteins and lines connecting spheres indicate interactions between proteins. Red spheres are proteins down-regulated in biofilms; blue spheres indicate proteins up-regulated; green triangles indicate unique proteins identified in biofilm. (A) General interactome; (B) cluster identifying proteins with higher connectivity; and (C) clusters showing higher score of strongest interactions.

Discussion

This is the first report evaluating the yeast C. neoformans biofilm using proteomics. Among the almost 2000 proteins detected, we found 76 proteins that were unique or more abundant in the biofilm state. Surprisingly, many (33) are uncharacterized hypothetical proteins. Many others are key metabolic enzymes that were previously identified in studies of bacterial biofilms. Together, these proteins provide potential and interesting targets for further studies.

Proteins Differentially Regulated in C. neoformans Biofilm

In our proteomic data, we were able to identify several proteins related to oxidative stress as differentially regulated or unique in the C. neoformans biofilm state: catalase, thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase, glutathione-disulfide reductase, Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, oxidoreductase, and HSP70, among others. Activation of the oxidative stress response is one hypothesis that has been proposed to explain the increased resistance in microbial biofilms. It has gained considerable attention in recent years, with increasing evidence from several proteomic and transcriptomic published papers on bacterial and fungal biofilms. For example, HSP70, a protective protein related to thermal and oxidative stress, was also found to be up-regulated in surface-associated proteins in the biofilm of another important pathogenic fungus, Candida albicans.25 In another study, a greater number of stress-response proteins including SOD, thioredoxin, and HSP70 were up-regulated in Actinomyces naeslundii biofilm.54 In microbial pathogens, HSPs are known to regulate virulence or immunological mechanisms.30 For C. neoformans, this protein seems to act by additional mechanisms, influencing the interaction of yeast–host cells,55 being considered the major antigen detected in patients with cryptococcosis.56,57 In our interactome analysis, Cu/ZN SOD presented strongest interaction with other SOD, reinforcing the possible importance of these proteins in biofilms. In Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, mutants lacking this enzyme were more susceptible to H2O2 than the wild type, displaying significant reduction in their capacity to adhere to epithelial cells and abiotic surfaces.58 Catalase, an important enzyme in protecting the cell from oxidative damage by reactive oxygen species, was identified in biofilms and is thought to be related to antimicrobial resistance.59−61 As expected, catalase activity was higher in biofilm cells than planktonic, showing evidence of their participation in ROS protection in the biofilm. Interestingly, thioredoxin-dependent peroxidase reductase and catalase were identified in C. albicans and had the capacity to bind plasminogen.25,62 We could identify a possible interaction between these proteins according to our interactome analysis.

Proteases could potentially help fungal dissemination into the host.63 In our study, two proteases (methionine aminopeptidase and elastinolytic metalloproteinase) were identified uniquely in the biofilm. Extracellular proteolytic activity was linked to a role in the dissemination of cryptococcosis, being able to cleave key host components of the basement membrane and extracellular matrix, which may be a relevant factor in the fungal invasion.65,65 Activation of plasminogen-to-plasmin is used by several microbial pathogens to increase their capacity for tissue invasion.66,67 In C. neoformans, plasminogen can passively coat the surface of pathogens and, upon conversion to plasmin, facilitate pathogen dissemination by degrading vascular barriers.68 Interestingly, protease activity on plasmin-specific substrate was higher in biofilm cells, which could link this resistant mode of growth to an infective behavior, where the cells would be prepared to invade the host tissue. Therefore, our hypothesis is that C. neoformans biofilm cells are more prepared to spread into the host.

Extracellular phosphatases have been implicated in the adhesion of several microbial pathogens and in host cell immune responses and play critical roles in signaling and biotic stress.52,69,70 Similarly, we have seen an increase in phosphatase protein and activity in C. neoformans biofilm. However, our results are from cell lysate, and the phosphatase we identified may be acting either outside the cell altering the host environment or inside the cell in a regulatory fashion.

Another protein with a possible function in biofilm adhesion is alanine aminotransferase. This enzyme catalyzes the reversible reaction between pyruvate and glutamate and alanine and α-ketoglutarate. It could be acting in pyruvate formation, which would be used for energy acquisition and therefore maintain the metabolic activity in biofilm cells. Otherwise, this protein is able to release alanine, an essential amino acid for cell maintenance. Alanine is present on Enterococcus faecalis and Streptococcus cell surfaces, and for these organisms, it is related to adhesion on surfaces and resistance.71,72 It is not clear if this role for bacterial alanine aminotransferase is conserved in C. neoformans.

Although protein synthesis continued, many proteins related to assembly of ribosome subunits were down-regulated, consistent with reduced protein yield in biofilm. Corroborating this result, we observed several ribosomal proteins interacting in our network analysis. C. gattii, another species causing cryptococcosis, presents down-regulation of ribosomal proteins in response to fluconazole,73 showing that the maintenance of ribosome synthesis was affected due to the slowing of active metabolism and growth, consistent with our results. This evidence suggests that protein biosynthesis is affected in C. neoformans biofilms, as proposed for bacterial cells growing in biofilms.74−76

Hypothetical Proteins Analysis

The differentially abundant proteins with known functions have been implicated in several cellular processes, including cell adhesion, host invasion, and metabolic regulation. However, a large portion of differentially abundant proteins have no known or theorized function.

Unique proteins identified in C. neoformans biofilm contain almost 50% of functionally unknown hypothetical proteins, suggesting that the complicated metabolic and regulation response to biofilm is still far from fully elucidated. Although, so far, almost no functional information is available for these proteins. The goal here was to gain insights about localization and functioning for all hypothetical proteins identified. The bioinformatic analysis suggested down-regulated proteins related to translation and transcription, agreeing with our results compared with identified and categorized proteins. The role of the hypothetical proteins is not known but likely plays a role in the distinct physiological state of the biofilm, as described for Desulfovibrio vulgaris, a sulfate-reducing bacteria also implicated in a variety of human infections.77 Although hypothetical proteins involved in biofilm changes have been reported before,23,78 further investigations are needed to evaluate their function because these proteins present homology to conserved hypothetical proteins from other microorganisms, including some pathogenic strains.

Changes in Metabolic Profile of C. neoformans Biofilm – KEGG Analysis

A biofilm is a heterogeneous collection of cells with different metabolic states; the upper layers of a biofilm are more metabolically active cells, whereas in the lower layers the cells are in a state of quiescence.14,79 As well described for bacteria, the increased tolerance to antibiotics occurs when nutrients are limited.61 Therefore, slower rates of growth, changes in protein synthesis and metabolic activity present in lower layers can contribute to the increased persistence and consequent resistance of C. neoformans biofilms. The metabolic profiles for C. neoformans have shown that pyruvate level, related to energy metabolism, was higher in biofilm than in planktonic culture, indicating a reduction in energy production. Agreeing with our results, a down-regulation in carbohydrate metabolism was observed in C. glabrata fungal biofilm,80 and Staphylococcus mutans biofilms showed down-regulated glycolysis.81 These changes in metabolic profiles may reflect reduced metabolic activity, which might contribute to persistence in biofilms. This is consistent with previous results that showed a slower growth rate for bacterial biofilms in comparison with planktonic cells.21,22 Also, in biofilms, the deeper layers of cells is located undergrowth-limiting conditions, with anaerobic or microanaerobic environment. These cells could be supported by pyruvate fermentation, allowing their maintenance with no or little oxygen.82 Alcohol dehydrogenase, an enzyme involved in pyruvate fermentation, was identified as down-regulated in C. neoformans biofilm. Similar result were found in C. albicans biofilm, where disruption of Adh1p significantly enhanced biofilm ex vivo and in vivo using engineered human oral mucosa and rat models.83 These results suggest that down-regulation of alcohol dehydrogenase could be a critical determinant of biofilm formation. Therefore, our results strongly suggest that for C. neoformans, as described for Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the biofilm cells may depend on pyruvate fermentation for long-term survival.21,22

In addition to an oxygen-limiting environment, the biofilm cells are in constant stress – lack of nutrients, excess of waste products, and changes in pH gradient. In addition to the enzymes previously discussed that are involved in oxidative stress (catalase, HSP, SOD), our results show the lactolylhydrolase lyase or glyoxalase I is up-regulated in the biofilm. This enzyme is related to pyruvate metabolism, where it can also act in the detoxification of methylglyoxal, a side product of several metabolic pathways, releasing d-lactate and restoring glutathione. Glutathione is an important cellular antioxidant and could be used for protection in biofilm cells. However, further studies are needed to explore the real function of glyoxalase I in biofilms.

Conclusions

C. neoformans biofilm formation on medical devices is considered a major source of foreign-body-associated infection. Through a shotgun proteomic approach comparing cells growing under biofilm and planktonic conditions, we provide insights about the metabolic mechanisms involved in cell maintenance, persistence and resistance. Giving special attention to those proteins differentially regulated in biofilms, this paper suggests a model of energy acquisition for biofilm cells. Although further investigations are needed, the fermentation pathway can be suggested as a target for new drugs. Within its biofilm, C. neoformans cells experience a highly stressful environment, with low oxygen and nutrient content and high waste products, showing a low rate of growth. To maintain the cells, pyruvate and glutamine appear to be contributing to growth and maintenance of the biofilm. Proteins involved in oxidative stress and related to tissue invasion were up-regulated, contributing to biofilm resistance and dispersion. These data suggest a metabolic correlation between bacterial and fungal biofilms. The proteins identified here provide additional information about the C. neoformans biofilm lifestyle. In conclusion, our proteomic data suggest general changes in metabolic processes, turnover, and global stress responses. Understanding the pathways associated with biofilm maintenance and resistance is key to evaluating the effects of antifungal drugs, which are urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Marilene H. Vainstein for providing the C. neoformans H99 strain and Dr. Dario Passos for technical support. This work was supported by grants from the following Brazilian agencies: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). W.O.B.S. and L.S. are fellows from Brazilian program Ciência Sem Fronteiras, CAPES. J.J.M. and J.R.Y. were supported by the National Center for Research Resources (5P41RR011823-17), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P41 GM103533-17), National Institute on Aging (R01AG027463-04), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5R01 HL019442).

Supporting Information Available

Kegg pathway of the TCA cycle showing proteins downregulated. Kegg pathway of the glycolysis/gluconeogenesis showing proteins downregulated. Kegg pathway of the pyruvate metabolism showing proteins down-regulated or up-regulated. Kegg pathway of the alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism showing proteins up-regulated. Kegg pathway of the glutathione metabolism showing proteins up-regulated. Immunoblot of Cryptococcus neoformans biofilm and planktonic cells using monoclonal anti-mouse HSP70 antisera. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Park B. J.; Wannemuehler K. A.; Marston B. J.; Govender N.; Pappas P. G.; Chiller T. M. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS 2009, 23, 525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronstad J. W.; Attarian R.; Cadieux B.; Choi J.; D’Souza C. A.; Griffiths E. J.; Geddes J. M.; Hu G.; Jung W. H.; Kretschmer M.; Saikia S.; Wang J. Expanding fungal pathogenesis: Cryptococcus breaks out of the opportunistic box. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 93193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon-Chung K. J.; Boekhout T.; Fell J. W.; Diaz M. Proposal to conserve the name Cryptococcus gattii against C. hondurianus and C. bacillisporus (Basidiomycota, Hymenomycetes, Tremellomycetidae). Taxon 2002, 51, 804–806. [Google Scholar]

- Ma H.; May R. C. Virulence in Cryptococcus species. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 67, 131–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell T. G.; Perfect J. R. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS--100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 84515–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez L. R.; Casadevall A. Susceptibility of Cryptococcus neoformans biofilms to antifungal agents in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 1021–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. M.; Campbell L.; Lodge J. K. Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus under stress. Curr. Opinion Microbiol. 2007, 10, 320–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier C.; Nielsen K.; Daou S.; Brigitte M.; Chretien F.; Dromer F. Evidence of a role for monocytes in dissemination and brain invasion by Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M.; Colarusso P.; Mody C. H. Real-time in vivo imaging of fungal migration to the central nervous system. Cell Microbiol. 2012, 14121819–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu K.; Eigenheer R. A.; Phinney B. S.; Gelli A. Cryptococcus neoformans promotes its transmigration into the central nervous system by inducing molecular and cellular changes in brain endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3139–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez L. R.; Casadevall A. Cryptococcus neoformans biofilm formation depends on surface support and carbon source and reduces fungal cell susceptibility to heat, cold, and UV light. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73144592–4601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer F. L.; Wilson D.; Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence 2013, 42119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage G.; Williams C. The clinical importance of fungal biofilms. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 84, 27–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratne C. J.; Wang Y.; Jin L.; Wong S. S.; Herath T. D.; Samaranayake L. P. Unraveling the resistance of microbial biofilms: has proteomics been helpful?. Proteomics 2012, 12, 651–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee U.; Gupta K.; Venugopal P. A case of prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 1997, 35, 139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun D. K.; Janssen D. A.; Marcus J. R.; Kauffman C. A. Review cryptococcal infection of a prosthetic dialysis fistula. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1994, 245864–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannsson B.; Callaghan J. J. Prosthetic hip infection due to Cryptococcus neoformans: case report. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2009, 64176–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T. J.; Schlegel R.; Moody M. M.; Costerton J. W.; Salcman M. Ventriculoatrial shunt infection due to Cryptococcus neoformans: an ultrastructural and quantitative microbiological study. Neurosurgery. 1986, 183373–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton J. W.; Stewart P. S.; Greenberg E. P. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999, 28454181318–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage G.; Mowat E.; Jones B.; Williams C.; Lopez-Ribot J. Our current understanding of fungal biofilms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 354340–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova O. E.; Schurr J. R.; Schurr M. J.; Sauer K. Microcolony formation by the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires pyruvate and pyruvate fermentation. Mol. Microbiol. 2012, 86, 819–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeom J.; Shin J.-H.; Yang J.-Y.; Kim J.; Hwang G.-S. 1H NMR-based metabolite profiling of planktonic and biofilm cells in Acinetobacter baumannii 1656–2. PLoS One 2013, 8, e57730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M. I.; Xiao J.; Lu B.; Delahunty C. M.; Yates J. R. 3rd.; Koo H. Streptococcus mutans protein synthesis during mixed-species biofilm development by high-throughput quantitative proteomics. PLoS One 2012, 7, e45795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N. J.; Steichen C. T.; Schilling B.; Post D. M. B.; Niles R. K.; Bair T. B.; Falsetta M. L.; Apicella M. A.; Gibson B. W. Proteomic analysis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae biofilms shows shift to anaerobic respiration and changes in nutrient transport and outermembrane proteins. PLoS One 2012, 7, e38303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. P.; Bachmann S. P.; Lopez-Ribot J. L. Proteomics for the analysis of the Candida albicans biofilm lifestyle. Proteomics 2006, 6, 5795–5804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Wang W.; Wang Y.; Zeng A. P. Two-dimensional gel-based proteomic of the caries causative bacterium Streptococcus mutans UA159 and insight into the inhibitory effect of carolacton. Proteomics 2013, 1323–243470–3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero Gómez N.; Abriouel H.; Ennahar S.; Gálvez A. Comparative proteomic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes exposed to enterocin AS-48 in planktonic and sessile states. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 1672202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Yi L.; Wu Z.; Shao J.; Liu G.; Fan H.; Zhang W.; Lu C. Comparative proteomic analysis of Streptococcus suis biofilms and planktonic cells that identified biofilm infection-related immunogenic proteins. PLoS One 2012, 74e33371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournu H.; Serneels J.; Van Dijck P. Fungal pathogens research: novel and improved molecular approaches for the discovery of antifungal drug targets. Curr. Drug Targets 2005, 68909–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crestani J.; Carvalho P. C.; Han X.; Seixas A.; Broetto L.; Fischer J. S. G.; Staats C. C.; Schrank A.; Yates J. R. 3rd; Vainstein M. H. Proteomic profiling of the influence of iron availability on Cryptococcus gattii. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 189–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn M. P.; Wolters D.; Yates J. R. 3rd. Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 193242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald W. H.; Tabb D. L.; Sadygov R. G.; MacCoss M. J.; Venable J.; Graumann J.; Johnson J. R.; Cociorva D.; Yates J. R. MS1, MS2, and SQT-three unified, compact, and easily parsed file formats for the storage of shotgun proteomic spectra and identifications. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 18182162–2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T.; Venable J. D.; Park S. K.; Cociorva D.; Lu B.; Liao L.; Wohlschlegel J.; Hewel J.; Yates J. R. ProLuCID, a fast and sensitive tandem mass spectra-based protein identification program. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2006, 5, S174. [Google Scholar]

- Tabb D. L.; McDonald W. H.; Yates J. R. 3rd. DTASelect and Contrast: tools for assembling and comparing protein identifications from shotgun proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2002, 1, 21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng J. K.; McCormack A. L.; Yates J. R. III. An approach to correlate MS/MS data to amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1994, 5, 976–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho P. C.; Fischer J. S.; Chen E. I.; Yates J. R. 3rd; Barbosa V. C. PatternLab for proteomics: a tool for differential shotgun proteomics. BMC Bioinf. 2008, 9, 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho P. C.; Fischer J. S.; Xu T.; Yates J. R. 3rd; Barbosa V. C. PatternLab: from mass spectra to label-free differential shotgun proteomics. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 2012, 13, 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho P. C.; Yates J. R. 3rd; Barbosa V. C. Improving the TFold test for differential shotgun proteomics. Bioinformatics 2012, 28121652–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A.; Götz S.; García-Gómez J. M.; Terol J.; Talón M.; Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21183674–3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M.; Ball C. A.; Blake J. A.; Botstein D.; Butler H.; Cherry J. M.; Davis A. P.; Dolinski K.; Dwight S. S.; Eppig J. T.; Harris M. A.; Hill D. P.; Issel-Tarver L.; Kasarskis A.; Lewis S.; Matese J. C.; Richardson J. E.; Ringwald M.; Rubin G. M.; Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25125–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz S.; Garcia-Gomez J. M.; Terol J.; Williams T. D.; Nagaraj S. H.; Nueda M. J.; Robles M.; Talon M.; Dopazo J.; Conesa A. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the blast2go suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36103420–3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsoon O.; Nielsen H.; Brunak S.; von Heijne G. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 300, 1005–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A.; Larsson B.; von Heijne G.; Sonnhammer E. L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 3053567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen T. N.; Brunak S.; von Heijne G.; Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L. J.; Stærfeldt H.-H.; Brunak S. Prediction of human protein function according to Gene Ontology categories. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D.; Clements J.; Eddy S. R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W29–W37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini A.; Szklarczyk D.; Frankild S.; Kuhn M.; Simonovic M.; Roth A.; Lin J.; Minguez P.; Bork P.; von Mering C.; Jensen L. J. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D808–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S.; Bader G. D. An improved method for scoring protein-protein interactions using semantic similarity within the gene ontology. BMC Bioinf. 2010, 11, 562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper S. D.; Bork P. Medusa: a simple tool for interaction graph analysis. Bioinformatics 2005, 21244432–4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi L.; Beys da Silva W. O.; Berger M.; Guimarães J. A.; Schrank A.; Vainstein M. H. Conidial surface proteins of Metarhizium anisopliae: Source of activities related with toxic effects, host penetration and pathogenesis. Toxicon 2010a, 55, 874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M.; Pinto A. F. M.; Guimarães J. A. Purification and functional characterization of bothrojaractivase, a prothormbin-activating metalloproteinase isolated from Bothrops jararaca snake venom. Toxicon 2008, 514488–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino-Gomes D.; Rocco-Machado N.; Santi L.; Broetto L.; Vainstein M. H.; Meyer-Fernandes J. R.; Schrank A.; Beys-da-Silva W. O. Inhibition of ecto-phosphatase activity in conidia reduces adhesion and virulence of Metarhizium anisopliae on the host insect Dysdercus peruvianus. Curr. Microbiol. 2013, 66, 467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Yi L.; Wu Z.; Shao J.; Liu G.; Fan H.; Zhang W.; Lu C. Comparative proteomic analysis of Streptococcus suis biofilms and planktonic cells that identified biofilm infected-related immunogenic proteins. PLoS One 2012, 7, e33371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddick J. S.; Brailsford S. R.; Rao S.; Soares R. F.; Kidd E. A.; Beighton D.; Homer K. A. Effect of biofilm growth on expression of surface proteins of Actinomyces naeslundii genospecies 2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 3774–3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira C. P.; Piffer A. C.; Kmetzsch L.; Fonseca F. L.; Soares D. A.; Staats C. C.; Rodrigues M. L.; Schrank A.; Vainstein M. H. The heat shock protein (Hsp) 70 of Cryptococcus neoformans is associated with the fungal cell surface and influences the interaction between yeast and host cells. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 60, 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakeya H.; Udono H.; Maesaki S.; Sasaki E.; Kawamura S.; Hossain M. A.; Yamamoto Y.; Sawai T.; Fukuda M.; Mitsutake K.; Miyazaki Y.; Tomono K.; Tashiro T.; Nakayama E.; Kohno S. Heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) as a major target of the antibody response in patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1999, 1153485–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakeya H.; Udono H.; Ikuno N.; Yamamoto Y.; Mitsutake K.; Miyazaki T.; Tomono K.; Koga H.; Tashiro T.; Nakayama E.; Kohno S. A 77-kilodalton protein of Cryptococcus neoformans, a member of the heat shock protein 70 family, is a major antigen detected in the sera of mice with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Infect. Immun. 1997, 6551653–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. H.; Lee Y.; Kim S.; Yeom J.; Seok Kim B.; Oh S.; Park S.; Jeon C. O.; Park W. The role of periplasmic antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase and thiol peroxidase) of the Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the formation of biofilms. Proteomics 2006, 6, 6181–6193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C. Y.; Chan Y. C.; Samaranayake L. P.; Seneviratne C. J. Biocide resistance of Candida and Escherichia coli biofilms is associated with higher antioxidative capacities. J. Hosp. Infect. 2012, 81, 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D.; Joshi-Datar A.; Lepine F.; Bauerle E.; Olakanmi O.; Beer K.; McKay G.; Siehnel R.; Schafhauser J.; Wang Y.; Britigan B. E.; Singh P. K. Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science 2011, 334, 982–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Acker H.; Sass A.; Bazzini S.; De Roy K.; Udine C.; Messiaen T.; Riccardi G.; Boon N.; Nelis H. J.; Mahenthiralingam E.; Coenye T. Biofilm-grown Burkholderia cepacia complex cells survive antibiotic treatment by avoiding production of reactive oxygen species. PLoS One 2013, 83e58943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe J. D.; Sievwright I. K.; Auld G. C.; Moore N. R.; Gow N. A.; Booth N. A. Candida albicans binds human plasminogen: identification of eight plasminogen-binding proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 4761637–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo M. C.; Nakayasu E. S.; Matsuo A. L.; Sobreira T. J.; Longo L. V.; Ganiko L.; Almeida I. C.; Puccia R. Vesicle and vesicle-free extracellular proteome of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: comparative analysis with other pathogenic fungi. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 1131676–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M. L.; dos Reis F. C.; Puccia R.; Travassos L. R.; Alviano C. S. Cleavage of human fibronectin and other basement membrane-associated proteins by a Cryptococcus neoformans serine proteinase. Microb. Pathog. 2003, 34265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J. i.; Lee Y. S.; Song C.-Y.; Kim B. S. Purification and characterization of a 43-kilodalton extracellular serine proteinase from Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 422722–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox D.; Smulian A. G. Plasminogen-binding activity of enolase in the opportunistic pathogen Pneumocystis carinii. Med. Mycol. 2001, 39, 495–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Xu Y.; Yestrepsky B. D.; Sorenson R. J.; Chen M.; Larsen S. D.; Sun H. Novel inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus virulence gene expression and biofilm formation. PLoS One 2012, 7, e47255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stie J.; Fox D. Blood-brain barrier invasion by Cryptococcus neoformans is enhanced by functional interactions with plasmin. Microbiology 2012, 1581240–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collopy-Junior I.; Esteves F. F.; Nimrichter L.; Rodrigues M. L.; Alviano C. S.; Meyer-Fernandes J. R. An ectophosphatase activity in Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 671010–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Xu J.; Yu Z. H.; Gunawan A. M.; Wu L.; Wang L.; Zhang Z. Y. Discovery and evaluation of novel inhibitors of mycobacterium protein tyrosine phosphatase B from the 6-Hydroxy-benzofuran-5-carboxylic acid scaffold. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 563832–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabretti F.; Theilackcer C.; Baldassarri L.; Kaczynski Z.; Kropecc A.; Holst O.; Huebner J. Alanine esters of enterococcal lipoteichoic acid play a role in biofilm formation and resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 4164–4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saar-Dover R.; Bitler A.; Nezer R.; Shmuel-Galia L.; Firon A.; Shimoni E.; Trieu-Cuot P.; Shai Y. D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids confers resistance to cationic peptides in group B Streptococcus by increasing the cell wall density. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 89e1002891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong H. S.; Campbell L.; Padula M. P.; Hill C.; Harry E.; Li S. S.; Wilkins M. R.; Herbert B.; Carter D. Time-course proteome analysis reveals the dynamic response of Cryptococcus gattii cells to fluconazole. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan B. W.; Valenta J. A.; Benedik M. J.; Wood T. K. Arrested protein synthesis increases persister-like cell formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 5731468–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah D.; Zhang Z.; Khodursky A. B.; Kaldalu N.; Kurg K.; Lewis K. Persisters: a distinct physiological state of E. coli. BMC Microbiol. 2006, 6, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison K. R.; Brynildsen M. P.; Collins J. J. Heterogeneous bacterial persisters and engineering approaches to eliminate them. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M. E.; He Z.; Redding A. M.; Joachimiak M. P.; Keasling J. D.; Zhou J. Z.; Arkin A. P.; Mukhopadhyay A.; Fields M. W. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of biofilms: carbon and energy flow contribute to the distinct biofilm growth state. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew J.; Zilm P. S.; Fuss J. M.; Gully N. J. A proteomic investigation of Fusobacterium nucleatum alkaline-induced biofilms. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fux C. A.; Costerton J. W.; Stewart P. S.; Stoodley P. Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2005, 13, 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratne C. J.; Wang Y.; Jin L.; Abiko Y.; Samaranayake L. P. Proteomics of drug resistance in Candida glabrata biofilms. Proteomics 2010, 10, 1444–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathsam C.; Eaton R. E.; Simpson C. L.; Browne G. V.; Berg T.; Harty D. W.; Jacques N. A. Up-regulation of competence- but not stress-responsive proteins accompanies and altered metabolic phenotype in Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Microbiology 2005, 151, 1823–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschbach M.; Schreiber K.; Trunk K.; Buer J.; Jahn D.; Schobert M. Long-term anaerobic survival of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa via pyruvate fermentation. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 4596–4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P. K.; Mohamed S.; Chandra J.; Kuhn D.; Liu S.; Antar O. S.; Munyon R.; Mitchell A. P.; Andes D.; Chance M. R.; Rouabhia M.; Ghannoum M. A. Alcohol dehydrogenase restricts the ability of the pathogen Candida albicans to form a biofilm on catheter surfaces through an ethanol-based mechanism. Infect. Immun. 2006, 7473804–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.