Abstract

Purpose.

To assess the influence of the Pitx2 transcription factor on the global gene expression profile of extraocular muscle (EOM) of mice.

Methods.

Mice with a conditional knockout of Pitx2, designated Pitx2Δflox/Δflox and their control littermates Pitx2flox/flox, were used. RNA was isolated from EOM obtained at 3, 6, and 12 weeks of age and processed for microarray-based profiling. Pairwise comparisons were performed between mice of the same age and differentially expressed gene lists were generated. Select genes from the profile were validated using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction and protein immunoblot. Ultrastructural analysis was performed to evaluate EOM sarcomeric structure.

Results.

The number of differentially expressed genes was relatively small. Eleven upregulated and 23 downregulated transcripts were identified common to all three age groups in the Pitx2-deficient extraocular muscle compared with littermate controls. These fell into a range of categories including muscle-specific structural genes, transcription factors, and ion channels. The differentially expressed genes were primarily related to muscle contraction. We verified by protein and ultrastructural analysis that myomesin 2 was expressed in the Pitx2-deficient mice, and this was associated with development of M lines evident in their orbital region.

Conclusions.

The global transcript expression analysis uncovered that Pitx2 primarily regulates a relatively select number of genes associated with muscle contraction. Pitx2 loss led to the development of M line structures, a feature more typical of other skeletal muscle.

Genomic profiling of conditional knockout mice for Pitx2 reveals that Pitx2 primarily regulates a relatively select number of genes including myosin heavy chain isoforms, sarcomere structure proteins, and calcium channels and regulatory proteins, all of which are associated with muscle contraction.

Introduction

The extraocular muscles (EOMs) have adapted a unique molecular expression pattern, to an extent that some have argued EOM to be classified as a specific allotype as are cardiac, smooth, and skeletal muscles.1 Its unique properties are driven by the requirements of the visual system for rapid, coordinated eye movements, which resist fatigue. The maintenance of the mature EOM phenotype relies on cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous regulatory mechanisms. Dissection of these regulatory mechanisms may make it possible to exploit them to modify EOM contractile properties and influence eye movements, which could lead to improvements in treatment for strabismus and other disorders of ocular motility. In addition, appreciation of phenotypic regulation may improve understanding of disease characteristics, such as the sparing of EOM by most muscular dystrophies and their preferential involvement by orbital myositis and myasthenia gravis.2

The regulation of the molecular signature of the EOM is not understood, but is influenced by extrinsic influences, such as innervation,3 stretch,4,5 thyroid hormone,6 and intrinsic properties. Pitx2, a bicoid-like homeobox transcription factor7–10 is an intrinsic controller of EOM development and targeted deletion of Pitx2 in mice by homologous recombination leads to agenesis of EOM.7,11 We have also determined Pitx2 to be a key regulator of the mature phenotype.12,13 Pitx2 is expressed in adult rodent EOM at high levels,12,14,15 and its conditional knockout at about P0 produces EOM without obvious pathology. The conditional knockout of Pitx2 occurs at a time when EOM is continuing to undergo postnatal development including refinement of its mature innervational and myosin expression patterns.12,13 However, alterations occur in key characteristics: (1) The Pitx2-deficient EOM are stronger, faster, but more fatigable. (2) The characteristic multiple innervation of certain fibers is lost. (3) Expression of myogenic regulatory factors such as myogenin, Myf5, and MyoD is dramatically downregulated. (4) Gene transcripts and protein levels of Myh6, Myh7, and Myh13 isoforms are downregulated, whereas the longitudinal and cross-sectional patterns of expression of 2A-MyHC and 2X-MyHC isoforms are altered.12,13 Therefore, Pitx2 must influence several pathways that control the adult EOM phenotype.

In this study, we used gene microarray (Affimetrix, Santa Clara, CA) analysis to evaluate and identify downstream processes regulated by Pitx2 in EOM. A select number of genes encoding major contractile proteins, transcription factors, and ion channels were found to be differentially expressed in Pitx2-deficient mice.

Methods

Animals

Two mouse strains were crossed to generate the Pitx2 conditional knockout mice: muscle creatine kinase (MCK)-Cre mouse strain and the Pitx2flox/flox mouse strain, as previously described.12 Determination of the genotype was performed by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from tail tips. Mice that were both Pitx2flox/flox and Cre positive were referred to as the conditional knockout Pitx2Δflox/Δflox mice; their littermates, Pitx2flox/flox mice, were used as controls. Animals were maintained in accordance with National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for animal care. All procedures involving mice were approved by Institutional Animal Use and Care Committees at Saint Louis University. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures established by the NIH and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and in the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Tissue Preparation

Extraocular rectus muscles were dissected at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months of age from both Pitx2Δflox/Δflox and their littermates Pitx2flox/flox mice. Tissues were snap frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until use. To minimize interlitter/animal variability, muscles were pooled from three mice for each of three independent replicates/age/muscle groups.

DNA Microarray

Isolation of RNA and preparation of labeled cRNA followed methods described previously.15–17 Labeled cRNA was hybridized to mouse genome arrays (Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Arrays; Fremont, CA), which interrogate 45,000 probe sets representing 39,000 unique transcripts and variants from over 34,000 well-characterized mouse genes. The manufacturer's standard posthybridization wash, double-stain, and scanning protocols used a fluidics station for washing and staining of arrays (Affymetrix GeneChip Fluidics Station 400 and GeneChip Scanner 3000).

Microarray Data Analysis

A commercial software suite (Affymetrix Microarray Suite [MAS], version 5.0) was used for initial data processing and fold ratio analyses. MAS evaluates sets of perfect match (PM) and mismatch (MM) probe sequences to obtain both hybridization signal values and present/absent calls for each transcript. We used the MAS filter to exclude transcripts that were absent from all samples for further analysis. Present calls for the samples range from 55.70% to 61.40%, with an average of 59.1 ± 0.01%. Any transcripts with expression intensity below 300 (fivefold the background level) across all the samples were also excluded since distortion of fold difference values results when expression levels are low and may be within the level of background noise. Pairwise comparisons were used. Transcripts defined as differentially regulated between Pitx2Δflox/Δflox and Pitx2flox/flox groups met the criteria of: (1) nine of nine increase/decrease calls each Pitx2Δflox/Δflox EOM versus Pitx2Δflox/Δflox EOM in three replicates with nine comparisons and (2) absolute value of the average fold difference value ≥2.0. Hierarchical clustering was performed using the clustering function in commercial software (GeneSpring; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). All differentially regulated genes as a gene list and their expression levels were organized by both individual samples as well as groups. Transcript annotations (Affymetrix) were replaced with official gene nomenclature and functions were assigned using information in National Center for Biotechnology Information Entrez Gene, UniGene, and PubMed, and Affymetrix NetAffx and Weizmann Institute of Science GeneCards databases.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Validation

Selected transcripts were reanalyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), using the same samples as in the microarray studies. Quantitative PCR used a PCR core reagent (SYBR green) with a sequence detection system (PRISM 7500 Sequence Detection System; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), as described previously.12 Mouse GAPDH was used as an internal positive loading control; for primers, see supplemental Table S1. Fold change values represent averages from triplicate measurements, using the 2−ΔΔCT method.18

Western Blot Analysis

EOMs from each mouse were rinsed in cold PBS before being homogenized with a microfuge pellet pestle (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 300 μL of homogenization buffer: 250 mM sucrose, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris plus 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis).19 The homogenate was kept on ice with shaking for 30 minutes and then centrifuged for 15 minutes at 13,000g at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the protein concentration was measured using the Bradford method.20 Muscle lysates containing 20 μg of total protein were separated by SDS-PAGE (7.5% acrylamide). Proteins were electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked in 5% blotting-grade blocker (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in Tris-buffered saline/Tween (TBST; 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 0.1% Tween 20) for at least 1 hour before addition of goat anti-myomesin 2 antibody (1:300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) at 4°C overnight. After being washed three times with TBST, the membrane was incubated with anti-goat horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 1:5000 dilution for 1 hour. Membranes were again washed three times with TBST, incubated with reagents from the enhanced chemiluminescent Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) according to the manufacturer's instructions and exposed to double-emulsion film (classic Blue BX Film; MidSci, St. Louis, MO) to visualize the immunoreactive bands.

Ultrastructural Analysis

Electron microscopy was performed as described by Schneiter et al.,21 with exceptions as noted. The EOMs were dissected from mice with eyeball attached and fixed overnight in 2% glutaraldehyde (with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate). The individual muscle was isolated from the eyeball and washed and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 30 minutes. Muscle was transferred to 1% uranyl acetate for 1 hour at room temperature, then dehydrated with ethanol and embedded in staining and embedding media (LX-112 resin; Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA). Longitudinal sections of the orbital layers were cut and stained with 2% uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate electron-opaque stain (Reynolds). Sections were examined with an electron microscope (JEM-100 CX11; JEOL, Tokyo) at 80 kV.

Results

Microarray Data Analysis

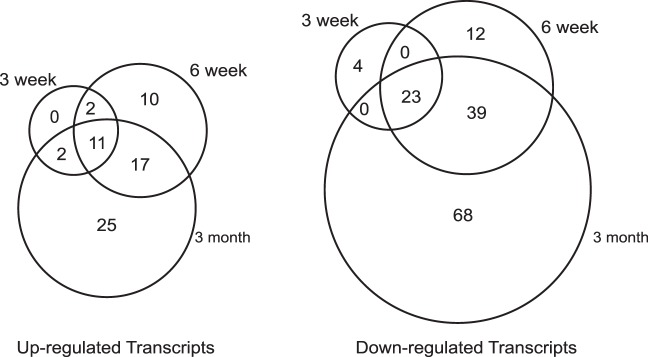

To identify global patterns of gene expression regulated by Pitx2 in the EOM of the mice, triplicate RNA samples were prepared and further processed for microarray hybridization from the conditional knockout Pitx2Δflox/Δflox mice and the control Pitx2flox/flox littermates at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months time points. The expression profiling showed 15 upregulated (supplemental Table S2 ) and 27 downregulated (supplemental Table S3 ) transcripts at 3 weeks, 40 upregulated (supplemental Table S4 ) and 74 downregulated (supplemental Table S5 ) transcripts at 6 weeks, 55 upregulated (supplemental Table S6 ) and 130 downregulated (supplemental Table S7 ) transcripts at 3 months in Pitx2Δflox/Δflox EOM compared with Pitx2flox/flox EOM at the analogous time points. These genes fell into the following major categories: muscle structural genes, transcription factors, receptors and ion channels, extracellular matrix molecules, molecules involved in metabolisms, responses to stress, immune responses, signaling, and some unclassified molecules and expressed sequence tags. A total of 213 transcripts were found to be differentially expressed in the EOM between Pitx2Δflox/Δflox and Pitx2flox/flox mice, covering 3 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months time points.

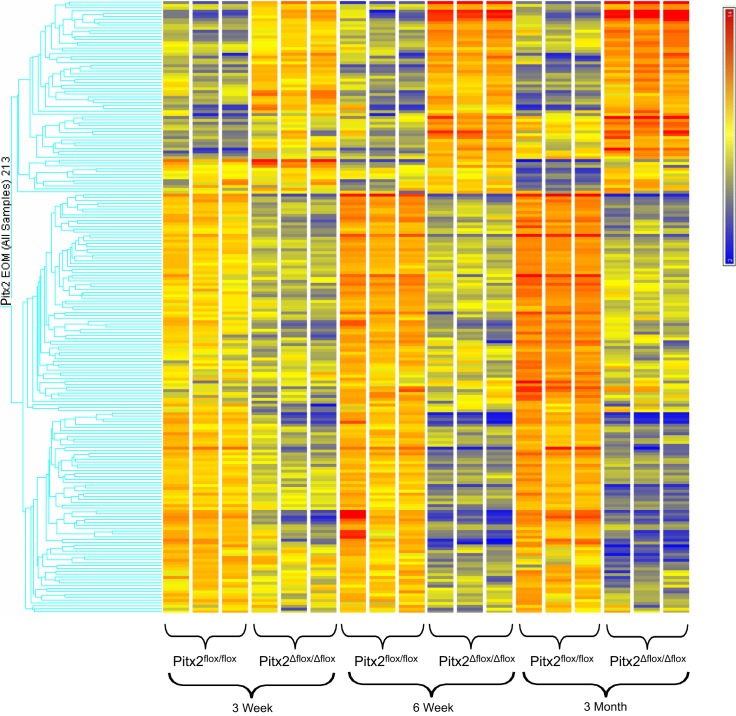

Hierachical cluster analysis (Fig. 1) showed a distinct temporal change in expression pattern of the genes found to be differentially influenced by the loss of Pitx2 expression. Over the period of 3 weeks to 3 months, EOMs of Pitx2Δflox/Δflox mice in comparison with the Pitx2flox/flox mice demonstrate a decreased expression in about two thirds of the differentially expressed genes interrogated and an increase in expression of about one third of differentially expressed genes. The overall alteration of gene expression is also appreciated in Figure 2. Comparison of the differentially regulated transcripts across all three time points identified 12 upregulated transcripts (Table 1) and 23 downregulated transcripts (Table 2) common to all three time points. The majority of up- and downregulated genes were related to muscle contraction. Specific gene changes are discussed in the Discussion section.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical clustering of the gene probes identified as differentially expressed between extraocular muscles of Pitx2Δflox/Δflox and Pitx2flox/flox mice at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months of age. Transcripts identified are those at the intersection of data obtained with the MAS and RMA algorithms (Affymetrix). The three independent replicates of each group are represented. The scale at the top right denotes normalized expression levels (red, high expression; blue, low expression).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram showing the numbers of differentially expressed transcripts between Pitx2Δflox/Δflox and Pitx2flox/flox EOM shared by or unique to the three time points.

Table 1.

Transcripts Upregulated in Pitx2Δflox/Δflox EOM Compared with Pitx2flox/flox EOM Common to 3-week, 6-week, and 3-month Time Points

|

Accession No. |

Gene Symbol |

Gene Title |

Go Biological Process Term |

3w Fold Change |

6w Fold Change |

3m fold Change |

| BB288010 | Myom2 | myomesin 2 | muscle contraction | 4.6 | 8.4 | 14 |

| BB474208 | Myom2 | myomesin 2 | muscle contraction | 5.0 | 14 | 16 |

| AV241307 | Myom2 | myomesin 2 | muscle contraction | 4.7 | 9.8 | 16 |

| AK014794 | Zmynd17 | zinc finger, MYND domain containing 17 | --- | 5.4 | 22 | 18 |

| BG069709 | Zdhhc23 | zinc finger, DHHC domain containing 23 | --- | 2.3 | 3.4 | 3.7 |

| AK004064 | Dysfip1 | dysferlin interacting protein 1 | --- | 2.5 | 3.9 | 4.9 |

| BM116248 | Ctxn3 | cortexin 3 | --- | 2.6 | 4.3 | 6.5 |

| NM_021487 | Kcne1l | potassium voltage-gated channel, Isk-related family, member 1–like | ion transport | 2.2 | 4.4 | 6.1 |

| AV238793 | Ryr3 | ryanodine receptor 3 | calcium ion transport /// striated muscle contraction /// transmembrane transport | 3.2 | 4.3 | 6.6 |

| X83934 | Ryr3 | ryanodine receptor 3 | calcium ion transport /// striated muscle contraction /// transmembrane transport | 3.2 | 5.8 | 7.9 |

| AV337888 | Pcp4l1 | Purkinje cell protein 4–like 1 | tricarboxylic acid cycle /// transport /// electron transport chain | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.8 |

Table 2.

Transcripts Downregulated in Pitx2Δflox/Δflox EOM Compared with Pitx2flox/flox EOM Common to 3-week, 6-week, and 3-month Time Points

|

Accession No. |

Gene Symbol |

Gene Title |

Go Biological Process Term |

3w Fold Change |

6w Fold Change |

3m fold Change |

| NM_009393 | Tnnc1 | troponin C, cardiac/slow skeletal | regulation of muscle contraction /// regulation of muscle filament sliding speed /// regulation of ATPase activity | −3.7 | −8.8 | −12 |

| NM_011619 | Tnnt2 | troponin T2, cardiac | regulation of muscle contraction /// muscle filament sliding /// regulation of ATPase activity | −4.1 | −19 | −11 |

| L47552 | Tnnt2 | troponin T2, cardiac | regulation of muscle contraction /// muscle filament sliding /// regulation of ATPase activity | −3.9 | −16 | −8.8 |

| BE952392 | Myh7b | myosin, heavy chain 7B, cardiac muscle, beta | --- | −2.9 | −4.1 | −3.4 |

| NM_010861 | Myl2 | myosin, light polypeptide 2, regulatory, cardiac, slow | cardiac myofibril assembly /// ventricular cardiac muscle tissue morphogenesis /// heart contraction | −4.3 | −7.9 | −7.1 |

| NM_080728 | Myh7 | myosin, heavy polypeptide 7, cardiac muscle, beta | muscle contraction /// muscle filament sliding /// ventricular cardiac muscle tissue morphogenesis | −3.1 | −6.5 | −10 |

| M76601 | Myh6 | myosin, heavy polypeptide 6, cardiac muscle, alpha | regulation of the force of heart contraction ///muscle contraction /// striated muscle contraction /// regulation of heart contraction | −6.4 | −14 | −6.3 |

| BB481540 | Myh6 /// Myh7 | myosin, heavy polypeptide 6, cardiac muscle, alpha /// myosin, heavy polypeptide 7, cardiac muscle, beta | regulation of the force of heart contraction /// striated muscle contraction | −3.4 | −20 | −7.0 |

| NM_021467 | Tnni1 | troponin I, skeletal, slow 1 | regulation of muscle contraction /// ventricular cardiac muscle tissue morphogenesis | −5.6 | −18 | −24 |

| BB772205 | Enho | energy homeostasis associated | --- | −2.6 | −4.1 | −5.2 |

| BB772205 | Enho | energy homeostasis associated | --- | −2.3 | −4.5 | −5.7 |

| AK005148 | Cyfip2 | cytoplasmic FMR1 interacting protein 2 | apoptosis /// apoptosis /// cell adhesion /// cell-cell adhesion /// cell-cell adhesion | −2.0 | −2.6 | −2.4 |

| BB333374 | Zfp385b | zinc finger protein 385B | --- | −2.7 | −5.1 | −6.2 |

| BE982894 | Zfp385b | zinc finger protein 385B | --- | −2.8 | −4.5 | −5.0 |

| AK002622 | Pln | phospholamban | regulation of the force of heart contraction /// calcium ion transport /// regulation of calcium ion transport | −3.0 | −4.8 | −3.3 |

| AI426503 | Mfsd4 | major facilitator superfamily domain containing 4 | transport /// transmembrane transport | −2.3 | −3.5 | −2.6 |

| BB278653 | Cacna2d4 | calcium channel, voltage-dependent, alpha 2/delta subunit 4 | transport /// ion transport /// calcium ion transport /// visual perception /// response to stimulus | −4.3 | −17 | −12 |

| AK002622 | Pln | phospholamban | regulation of the force of heart contraction /// calcium ion transport /// regulation of calcium ion transport | −2.2 | −3.3 | −2.2 |

| AK002622 | Pln | phospholamban | regulation of the force of heart contraction /// calcium ion transport /// regulation of calcium ion transport | −3.0 | −5.3 | −3.2 |

| BC010288 | Psp | parotid secretory protein | --- | −6.4 | −18 | −62 |

| NM_007389 | Chrna1 | cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 1 (muscle) | ion transport /// neuromuscular synaptic transmission /// regulation of membrane potential | −2.2 | −3.2 | −3.4 |

| BB020678 | Fam196b | family with sequence similarity 196, member B | --- | −2.9 | −7.0 | −16 |

| AV026232 | 4832428D23Rik | RIKEN cDNA 4832428D23 gene | --- | −2.1 | −2.1 | −4.1 |

Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Results of microarray gene expression evaluation were validated by qPCR for 13 select transcripts. The expression levels of four upregulated genes (Kcne1l, Myom2, Ryr3, and Zmynd17) and ten downregulated genes (Cacna2d4, Myh6, Myh7, Myl2, Pln, Psp, Tnnc, TnnI, Tnnt2, and Zfp533) were assessed. Expression changes were normalized to GAPDH expression. The qPCR analysis correlated well with the DNA microarray analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Validation of Differentially Expressed Genes by Real-Time PCR Fold Changes of Transcripts from Microarray VS from Real-Time PCR

|

3w microarray |

3w real-time PCR |

6w microarray |

6w real-time PCR |

3m microarray |

3m real-time PCR |

|

| Upregulated genes | ||||||

| Kcne1l | 2.2 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 4.4 | 3.8 ± 1 | 6.1 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| Myom2 | 5.0 | 8.3 ± 1.0 | 14 | 22 ± 3 | 16 | 23 ± 1 |

| Ryr3 | 3.2 | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 5.8 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 7.9 | 10 ± 2 |

| Zmynd17 | 5.4 | 25 ± 1 | 22 | 27 ± 3 | 18 | 26 ± 4 |

| Downregulated genes | ||||||

| Cacna2d4 | −4.3 | −6.9 ± 0.3 | −17 | −35 ± 7 | −12 | −34 ± 2 |

| Myh6 | −6.4 | −15 ± 2 | −14 | −8.4 ± 0.6 | −6.3 | −6.2 ± 0.7 |

| Myh7 | −3.1 | −4.6 ± 0.1 | −6.5 | −6.9 ± 0.3 | −10 | −6.1 ± 0.5 |

| Myl2 | −4.3 | −7.4 ± 0.3 | −7.9 | −17 ± 4 | −7.1 | −9.3 ± 0.7 |

| Pln | −3.0 | −2.4 ± 0.2 | −5.3 | −3.9 ± 0.2 | −3.2 | −3.7 ± 0.2 |

| Psp | −6.4 | −6.4 ± 0.2 | −18 | −39 ± 3 | −62 | −273 ± 8 |

| Tnnc1 | −3.7 | −5.3 ± 0.2 | −8.8 | −6.2 ± 0.1 | −12 | −12 ± 0.2 |

| Tnni1 | −5.6 | −9.5 ± 0.3 | −18 | −22 ± 1 | −24 | −24 ± 1 |

| Tnnt2 | −4.1 | −5.6 ± 0.4 | −19 | −14 ± 2 | −11 | −11 ± 1 |

| Zfp533 | −2.7 | −3.3 ± 0.1 | −5.1 | −21 ± 1 | −6.2 | −6.4 ± 0.6 |

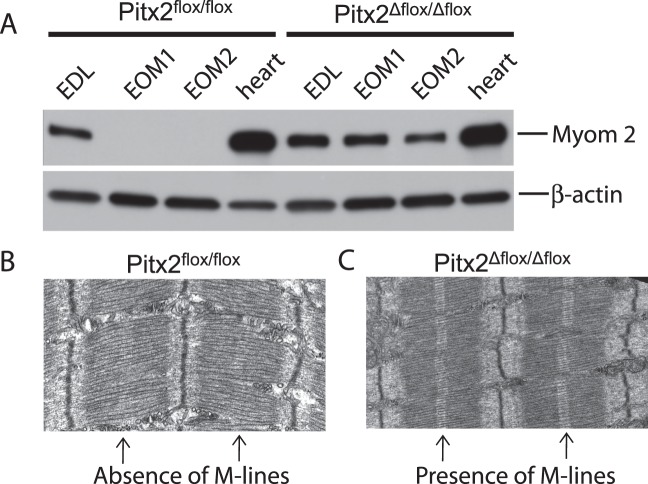

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Genomic profiling and qPCR identified myomesin 2 to be significantly upregulated at all three time points. Western blot analysis demonstrated that myomesin 2 protein was also increased in Pitx2Δflox/Δflox EOM (Fig. 3). Myomesin 2 is undetectable in the EOM of the wild-type Pitx2flox/flox mice, whereas it is readily identified in extensor digitorum longus and heart. In contrast, in EOM from the Pitx2Δflox/Δflox mice, myomesin 2 is expressed at levels comparable to those of the extensor muscle. The upregulation of both transcript and protein levels of myomesin 2 prompted us to examine the ultrastructure of the sarcomere since myomesin 2 is one of the principal scaffolding components of M-lines, which cross-link the thick filaments of the sarcomere in place.22,23 M-lines were present in the orbital layer of the Pitx2Δflox/Δflox EOM (Fig. 3C), whereas the M-lines were not detected in the Pitx2flox/flox EOM (Fig. 3B). The analysis was performed only on the orbital layers because of the much greater complexity of global layer fiber-type composition.24

Figure 3.

Validation of myomesin 2 expression in Pitx2Δflox/Δflox extraocular muscle. Western blot analysis (A) showed that myomesin 2 is not expressed in Pitx2flox/flox extraocular muscle but readily detected in the Pitx2Δflox/Δflox extraocular muscle. This upregulation is unique to extraocular muscle as myomesin 2 is expressed in both extensor digitorum longus and heart at comparable levels between Pitx2Δflox/Δflox and Pitx2flox/flox mice. Duplicate samples of EOM tissues from two different mice of both Pitx2Δflox/Δflox and Pitx2flox/flox genotypes were used for Western blot analysis. Electron microscopy showed that sarcomeres of the extraocular muscles from the Pitx2flox/flox mice (B) do not have M-lines, whereas that from Pitx2Δflox/Δflox mice (C) now have M-lines.

Discussion

Our investigation demonstrates that Pitx2 in the immediate postnatal period controls a relatively select number of genes primarily involved in muscle contraction. The Pitx2 conditional knockout EOM had a gradual decrease in expression of two thirds of the differentially expressed genes compared with Pitx2-sufficient EOM, suggesting that Pitx2 primarily acts through initiation of gene expression. Pitx2 was found to influence transcript levels of genes that are involved in characteristics that are a hallmark of wild-type EOM. The absence of Pitx2 led to the expression of myomesin 2 and return of M-lines to orbital fibers, a characteristic of other skeletal muscle.25 Our previous studies demonstrated the loss of three unique characteristics of EOMs: (1) special MyHC isoform expression (α-cardiac MyHC, slow-MyHC, eom-MyHC, and slow-tonic MyHC), (2) the variation in longitudinal expression of many MyHC isoforms, and (3) multiinnervation.12,13 Coupled with the present evaluations, we conclude that Pitx2 in the mature EOM is responsible for regulation of genes involved in establishment of unique aspects of EOM contractile properties.

Myosin Heavy Chain and Related Genes

We have previously detailed the gene and protein expression patterns of myosin heavy chains in wild-type and Pitx2-deficient EOMs.13,26 Of the nine myosin heavy chain isoforms expressed in EOMs, four of them (Myh6, Myh7, Myh13, and Myh14) exhibited a dramatic decrease in the expression of both transcript and protein levels, whereas Myh1 and Myh2 had altered cross-sectional and longitudinal expression patterns, although the transcript levels did not show a significant change. Our current genomic profiling demonstrated that Myh6 and Myh7 transcripts were dramatically reduced, as were transcripts of troponins expected to bind these myosin heavy chains,27 whereas transcript levels for Myh1, Myh2, Myh3, and Myh4 were not significantly altered (data not shown), supporting our previous data with qPCR and immunohistochemistry.12,13 Myh13 and Myh14, which are expressed in EOMs,28,29 were not represented on the gene chips used for this investigation.

Structural Proteins

The sarcomere is the functional and structural unit for the striated musculature, in which the thin actin filaments and the thick myosin filaments are arranged into an orderly lattice.23 Myomesin 1 and myomesin 2 are the principal scaffolding components of M-lines, which cross-link the thick filaments in sarcomeres. M-lines tend to be most prominent in fast-twitch muscle fibers and myomesin 2 is found exclusively in fast-twitch fibers.22,23 Myomesin 2 is thought to improve the stability of thick filament lattices by increasing their stiffness and thus increasing their force generation.30 After early developmental stages of EOM, myomesin expression is downregulated,31,32 and sarcomeres develop a “fuzzy” appearance, weaker M-bands, and poor lattice order. Despite their rapid contractile characteristics, adult EOM fibers of rodents do not express myomesin 2 and lack well-structured M-lines typical of other skeletal muscle.24,31,33 Wiesen and colleagues24 hypothesized that the poor lattice structure of sarcomeres lacking M-line components in EOM would contribute to the fibers being more elastic and having lower force generation.24,34,35 In the Pitx2Δflox/Δflox mice, myomesin 2 transcripts were found to be significantly increased in the genomic profile. The profiling observations were verified by qPCR and immunoblot analysis. Ultrastructural analysis was focused on orbital region fibers, since they are known to have a particularly poorly defined M-line structure, whereas global region fibers are much more heterogeneous.24 Interestingly, M-lines were identified in fibers of the Pitx2-deficient mice but not in the Pitx2flox/flox mice. Previous physiological studies12 of EOM from Pitx2Δflox/Δflox mice identified the muscles to have greater force generation, which would support the contention espoused by Wiesen and colleagues24that mature M-line structures would enhance force generation.

Channel and Transport

Across the three time points we found the transcript for the potassium channel ancillary protein Kcne1 to be increased in expression in the Pitx2Δflox/Δflox EOM. KCNE peptides influence expression, pharmacology, and physiologic properties of potassium channels.36 KCNE1 slows voltage-stimulated channel activation, increases conductance, and eliminates channel inactivation.37,38 The expectation of KCNE1 upregulation in the Pitx2Δflox/Δflox EOM would be to terminate muscle depolarization more rapidly, producing a more rapid twitch contraction, which is what we have observed.12

The expression of ryanodine receptor 3 (RyR3) was also found to gradually increase over time. The RyR3 gene encodes the intracellular Ca2+ release channel ryanodine receptor.39 Together, RyR3 along with RyR1 control the resting calcium ion concentration in skeletal muscle.40 Enhanced expression of RyR3 would be expected to lead to more rapid calcium sequestration and a shorter twitch, which is what we observed in Pitx2-deficient EOM. Cacna2d4 encodes an L-type calcium channel auxiliary subunit gene.41 In skeletal muscle, opening of the L-type calcium channel in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) causes opening of the ryanodine receptor. Calcium released from the SR binds to troponin C on the actin filaments as part of activation of muscle contraction. In human embryonic kidney 293 cells, the Cacna2d4 subunit increases calcium influx.41 If the same occurs in EOM, the reduced expression of Cacna2d4 in the Pitx2-deficient mice may lead to a shorter period of contraction. Phospholamban interacts with the SR calcium pump (SERCA) and decreases SERCA calcium affinity, thereby reducing contractile force.42 Phospholamban is preferentially expressed in slow-twitch fibers.43 The Ca affinity for Ca transport of SERCA 1 or 2, both of which are expressed in EOM, is lowered by coexpression with phospholamban.44 Here again, the reduction of phospholamban expression would serve to increase the force of contraction, which is exactly what was observed in our previous contractile studies.

The gene transcript encoding the α-subunit of acetylcholine receptor was reduced in the Pitx2-deficient EOM. Our previous investigation13 identified loss of multiinnervation, which likely explains the reduced production of the α-subunit transcript.

Transcriptional Factors

We identified alterations in transcriptional factors (Zmynd17, Zdhhc23, Zfp385b), each of which have zinc finger domains. Although it is known that Zfp385b is expressed in heart and ocular tissues,45 the function of these transcription factors is otherwise unknown. Their differential expression is influenced by Pitx2 deficiency and presumably has a functional role in influencing the mature EOM phenotype.

Cortexin 3

Cortexin 3 was found upregulated across all three time points of investigation. Previously, identified only in kidney and brain,46 cortexin 3 has been found to promote neurite growth in culture.47 A highly speculative interpretation of this observation would be that cortexin 3 upregulation is a response to the loss of multiinnervation in the Pitx2-deficient EOM and is an attempt to induce neurite outgrowth.

Conclusions

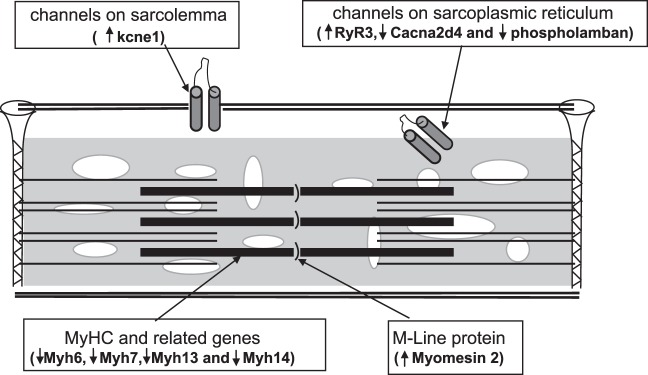

Our investigations indicate that Pitx2 in the mature EOM regulates a subset of genes primarily related to muscle contraction (Fig. 4). From the present evaluation, we cannot determine whether Pitx2 directly regulates transcription of these genes or whether it acts through intermediaries. The alteration of contractile characteristics and multiinnervation is also likely to influence gene expression indirectly in the EOM of Pitx2Δflox/Δflox mice. Further definition of transcription regulation of the adult EOM phenotype will allow a logical manipulation of gene transcription, to modify EOM contraction for therapeutic purposes.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of key gene expression alterations that are associated with the conditional knockout of Pitx2 in EOM. The transcript alterations are consistent with the physiologic alterations that would produce a muscle that has greater contractile force and speed, which is consistent with previous physiologic studies (see Discussion section for details).

Supplementary Material

Disclosure: Y. Zhou, None; B. Gong, None; H.J. Kaminski, None

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute Grant R01 EY-015306 (HJK).

References

- 1. Spencer RF, Porter JD. Biological organization of the extraocular muscles. Prog Brain Res. 2006;151:43–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaminski HJ, Richmonds CR, Kusner LL, Mitsumoto H. Differential susceptibility of the ocular motor system to disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;956:42–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gundersen K, Leberer E, Lomo T, Pette D, Staron RS. Fibre types, calcium-sequestering proteins and metabolic enzymes in denervated and chronically stimulated muscles of the rat. J Physiol. 1988;398:177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldspink G, Scutt A, Loughna PT, Wells DJ, Jaenicke T, Gerlach GF. Gene expression in skeletal muscle in response to stretch and force generation. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:R356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldspink G, Scutt A, Martindale J, Jaenicke T, Turay L, Gerlach GF. Stretch and force generation induce rapid hypertrophy and myosin isoform gene switching in adult skeletal muscle. Biochem Soc Trans. 1991;19:368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simonides WS, van Hardeveld C. Thyroid hormone as a determinant of metabolic and contractile phenotype of skeletal muscle. Thyroid. 2008;18:205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gage PJ, Suh H, Camper SA. Dosage requirement of Pitx2 for development of multiple organs. Development. 1999;126:4643–4651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin CR, Kioussi C, O'Connell S, et al. Pitx2 regulates lung asymmetry, cardiac positioning and pituitary and tooth morphogenesis. Nature. 1999;401:279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Piedra ME, Icardo JM, Albajar M, Rodriguez-Rey JC, Ros MA. Pitx2 participates in the late phase of the pathway controlling left-right asymmetry. Cell. 1998;94:319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryan AK, Blumberg B, Rodriguez-Esteban C, et al. Pitx2 determines left-right asymmetry of internal organs in vertebrates. Nature. 1998;394:545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitamura K, Miura H, Miyagawa-Tomita S, et al. Mouse Pitx2 deficiency leads to anomalies of the ventral body wall, heart, extra- and periocular mesoderm and right pulmonary isomerism. Development. 1999;126:5749–5758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou Y, Cheng G, Dieter L, et al. An altered phenotype in a conditional knockout of Pitx2 in extraocular muscle. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4531–4541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou Y, Liu D, Kaminski HJ. Pitx2 regulates myosin heavy chain isoform expression and multi-innervation in extraocular muscle. J Physiol. 2011;589:4601–4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fischer MD, Gorospe JR, Felder E, et al. Expression profiling reveals metabolic and structural components of extraocular muscles. Physiol Genomics. 2002;9:71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Porter JD, Khanna S, Kaminski HJ, et al. Extraocular muscle is defined by a fundamentally distinct gene expression profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12062–12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Porter JD, Khanna S, Kaminski HJ, et al. A chronic inflammatory response dominates the skeletal muscle molecular signature in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Porter JD, Merriam AP, Leahy P, Gong B, Khanna S. Dissection of temporal gene expression signatures of affected and spared muscle groups in dystrophin-deficient (mdx) mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1813–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Talmadge RJ, Roy RR. Electrophoretic separation of rat skeletal muscle myosin heavy-chain isoforms. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:2337–2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schneiter R, Hitomi M, Ivessa AS, Fasch EV, Kohlwein SD, Tartakoff AM. A yeast acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase mutant links very-long-chain fatty acid synthesis to the structure and function of the nuclear membrane-pore complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:7161–7172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Squire JM. Architecture and function in the muscle sarcomere. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agarkova I, Perriard JC. The M-band: an elastic web that crosslinks thick filaments in the center of the sarcomere. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wiesen MH, Bogdanovich S, Agarkova I, Perriard JC, Khurana TS. Identification and characterization of layer-specific differences in extraocular muscle M-bands. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. English AW, Wolf SL. The motor unit. Anatomy and physiology. Phys Ther. 1982;62:1763–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou Y, Liu D, Kaminski HJ. Myosin heavy chain expression in mouse extraocular muscle: more complex than expected. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:6355–6363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gomes AV, Potter JD, Szczesna-Cordary D. The role of troponins in muscle contraction. IUBMB Life. 2002;54:323–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schachat F, Briggs MM. Phylogenetic implications of the superfast myosin in extraocular muscles. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:2189–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rossi AC, Mammucari C, Argentini C, Reggiani C, Schiaffino S. Two novel/ancient myosins in mammalian skeletal muscles: MYH14/7b and MYH15 are expressed in extraocular muscles and muscle spindles. J Physiol. 2010;588:353–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pask HT, Jones KL, Luther PK, Squire JM. M-band structure, M-bridge interactions and contraction speed in vertebrate cardiac muscles. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1994;15:633–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Porter JD, Merriam AP, Gong B, et al. Postnatal suppression of myomesin, muscle creatine kinase and the M-line in rat extraocular muscle. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:3101–3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fischer MD, Budak MT, Bakay M, et al. Definition of the unique human extraocular muscle allotype by expression profiling. Physiol Genomics. 2005;22:283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andrade FH, Merriam AP, Guo W, et al. Paradoxical absence of M lines and downregulation of creatine kinase in mouse extraocular muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:692–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Agarkova I, Ehler E, Lange S, Schoenauer R, Perriard JC. M-band: a safeguard for sarcomere stability? J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2003;24:191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Agarkova I, Schoenauer R, Ehler E, et al. The molecular composition of the sarcomeric M-band correlates with muscle fiber type. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roura-Ferrer M, Etxebarria A, Sole L, et al. Functional implications of KCNE subunit expression for the Kv7.5 (KCNQ5) channel. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;24:325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCrossan ZA, Abbott GW. The MinK-related peptides. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:787–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Melman YF, Krummerman A, McDonald TV. KCNE regulation of KvLQT1 channels: structure-function correlates. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, Hamilton SL. Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perez CF, Lopez JR, Allen PD. Expression levels of RyR1 and RyR3 control resting free Ca2+ in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C640–C649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Qin N, Yagel S, Momplaisir ML, Codd EE, D'Andrea MR. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human voltage-gated calcium channel alpha(2)delta-4 subunit. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:485–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mueller B, Karim CB, Negrashov IV, Kutchai H, Thomas DD. Direct detection of phospholamban and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase interaction in membranes using fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8754–8765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jorgensen AO, Jones LR. Localization of phospholamban in slow but not fast canine skeletal muscle fibers. An immunocytochemical and biochemical study. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:3775–3781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kjellgren D, Ryan M, Ohlendieck K, Thornell LE, Pedrosa-Domellof F. Sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPases (SERCA1 and -2) in human extraocular muscles. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:5057–5062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16899–16903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang HT, Chang JW, Guo Z, Li BG. In silico-initiated cloning and molecular characterization of cortexin 3, a novel human gene specifically expressed in the kidney and brain, and well conserved in vertebrates. Int J Mol Med. 2007;20:501–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chalisova NI, Khavinson VK. Studies of cytokines in nerve tissue cultures. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2000;30:261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.