Abstract

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) play an important role in many biological processes in the extracellular matrix. In a theoretical approach, structures of monosaccharide building blocks of natural GAGs and their sulfated derivatives were optimized by a B3LYP6311ppdd//B3LYP/6-31+G(d) method. The dependence of the observed conformational properties on the applied methodology is described. NMR chemical shifts and proton-proton spin-spin coupling constants were calculated using the GIAO approach and analyzed in terms of the method's accuracy and sensitivity towards the influence of sulfation, O1-methylation, conformations of sugar ring, and ω dihedral angle. The net sulfation of the monosaccharides was found to be correlated with the 1H chemical shifts in the methyl group of the N-acetylated saccharides both theoretically and experimentally. The ω dihedral angle conformation populations of free monosaccharides and monosaccharide blocks within polymeric GAG molecules were calculated by a molecular dynamics approach using the GLYCAM06 force field and compared with the available NMR and quantum mechanical data. Qualitative trends for the impact of sulfation and ring conformation on the chemical shifts and proton-proton spin-spin coupling constants were obtained and discussed in terms of the potential and limitations of the computational methodology used to be complementary to NMR experiments and to assist in experimental data assignment.

1. Introduction

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) represent a class of linear anionic heteropolysaccharides containing repeating disaccharide units made up of a hexose or a hexuronic acid linked to a hexosamine by a 1-3 or 1-4 glycosidic linkage. Hydroxyl groups of these saccharides can be sulfated at different positions. Being localized in the extracellular matrix, GAGs play a crucial role in cell adhesion and proliferation [1] by involvement in key molecular regulatory mechanisms [2]. As for all saccharides, GAGs are very flexible and adopt a number of energetically similar conformational states under physiological conditions, which render structural studies of GAGs challenging from both the experimental [3, 4] and the computational [5] points of view. Solvent is suggested to play an indispensable role for the structure and dynamics of saccharides due to the tight coupling of solvent and solute dynamics, their interactions [6–10], and the effects of electrostatic polarization [11]. In addition, the highly charged nature of GAGs makes their interactions with solvent molecules by hydrogen bonding even more important for the exploration of their conformational space [10, 12–15]. The rapid exchange of the intramolecular and solvent-mediated hydrogen bonds does not allow experimental techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to gain a deep view on the hydrogen bonds formation in GAGs and, therefore, computational methods as molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are very useful to analyze GAGs structural properties in more detail [16]. Regarding the sulfation patterns of GAGs, combination of NMR with MD [17] and quantum mechanical (QM) [18] approaches were successfully applied to reveal the impact of sulfation effects on GAGs structure in terms of dynamic behaviour of glycosidic linkages. However, not only glycosidic linkage conformations but also sugar ring puckering could be decisive for the biologic relevance and the specificity of GAG/protein interactions [19]. In the case of heparin, it is supposed that the conformational flexibility of the free heparin molecule is not dramatically affected by the flexibility of the IdoUA(2S) sugar rings [20]. Nevertheless, it was reported that in the complex of heparin pentasaccharide with FGFR one of the IdoUA(2S) adopted the 2S0 ring conformation, whereas the rest of IdoUA(2S) residues were in the 1C4 ring conformation, providing high specificity for the formation of this GAG/protein complex [21]. Therefore, it is important to understand the basic rules governing the ring conformation preferences for individual monosaccharide blocks of the GAG molecules. The ring conformational space for several GAG mono- and disaccharides for GlcNAc and its N-, 3-O, and 6-O sulfated derivatives [22], GlcUA, IdoUA [23, 24], IdoUA(2S) [23, 25, 26], and heparin disaccharides [27, 28], was extensively analyzed in recent studies by means of MD, QM, and NMR approaches, demonstrating agreement and complementarity of these methodologies. This suggests a high potential of the use of theoretical approaches for the assistance in interpretation of NMR experimental data. Interestingly, despite the above-mentioned important role of solvent, the use of an implicit solvent model (in contrast to the use of explicit solvent molecules) does not improve agreement between spin-spin coupling parameters calculated by QM and measured experimentally by NMR [26].

In addition to natural GAGs, artificial GAGs with distinct sulfation patterns are promising components for functional biomaterials targeted for extracellular artificial matrix engineering since additional sulfate groups could modulate specific binding of growth factors and thereby influence wound healing [29–31]. Unfortunately, sometimes only the net sulfation degree of GAGs used in the experiments but not the exact sulfation pattern is known, which renders assignment of NMR spectra for the following elucidation of structure-function relationships more challenging. Therefore, theoretical analysis of the structural properties of sulfated GAG monosaccharides and calculation of their NMR chemical shifts and spin-spin coupling constants could be essential for the assistance in NMR experimental data interpretation. Along these lines, it was shown that specific sulfation patterns of some GlcNAc derivatives induce changes in ring puckering preferences [22]. Here, we systematically study sulfated derivatives of GlcNAc, GalNAc, IdoUA, and GlcUA with varying degrees of net sulfation, which represent the building blocks for heparin, hyaluronic acid, chondroitin sulfate, and dermatan sulfate. In particular, we analyze conformational preferences of the sugar rings using a QM approach, the impact of sulfation, and used polymerization models. Furthermore, we calculate NMR parameters using several computational models, which provide GAG monosaccharide conformational QM dictionary data. For GlcNAc, GlcNAc(6S), GalNAc, GalNAc(4S), and GalNAc(6S), we compare our calculated parameters with experimental data on 13C and 1H chemical shifts and proton-proton spin-spin coupling constants (3JH-H), and we discuss the potential accuracy of this methodology. For GlcNAc and GalNAc sulfated derivatives, the conformational space of the dihedral angle around the C5–C6 bond is analyzed and compared within QM and MD approaches. The data obtained in this work help to get a deeper insight in the potential and limitations of state-of-the-art computational methods used to complement NMR experiment interpretation for GAG molecules.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantum Mechanical Calculation

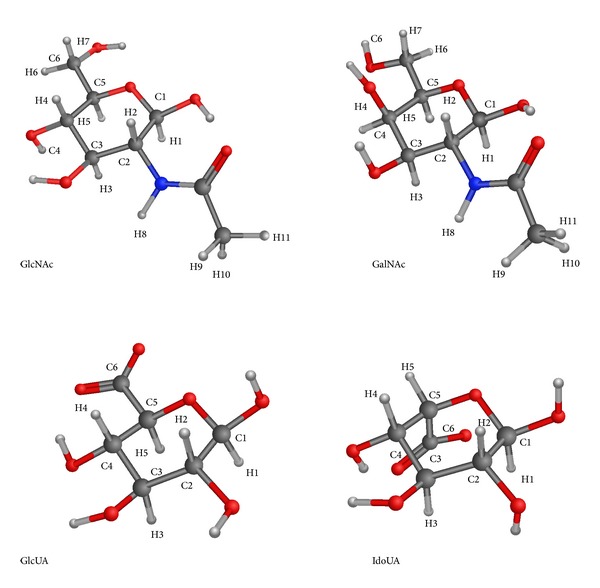

The following monosaccharides (Figure 1) and their O1-methylated variants (abbreviated with M- in Tables 1 and 2) were used for QM calculations: GlcNAc (β-D-N-acetylglucosamine), GlcNAc(4S) (4-O-sulfo-β-D-N-acetylglucosamine), GlcNAc(6S) (6-O-sulfo-β-D-N-acetylglucosamine), GlcNAc(46S) (4,6-O-disulfo-β-D-N-acetylglucosamine), GalNAc (β-D-N-acetylgalactosamine), GalNAc(4S) (4-O-sulfo-β-D-N-acetylgalactosamine), GalNAc(6S) (6-O-sulfo-β-D-N-acetylgalactosamine), GalNAc(46S) (4,6-O-disulfo-β-D-N-acetylgalactosamine), GlcUA (β-D-glucuronic acid), GlcUA(2S) (2-O-sulfo-β-D-glucuronic acid), GlcUA(3S) (3-O-sulfo-β-D-glucuronic acid), GlcUA(23S) (2,3-O-disulfo-β-D-glucuronic acid), IdoUA (α-L-iduronic acid), IdoUA(2S) (2-O-sulfo-α-L-iduronic acid), and IdoUA(3S) (3-O-sulfo-α-L-iduronic acid), IdoUA(23S) (2,3-O-disulfo-α-L-iduronic acid).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure ofβ-D-GlcNAc,β-D-GalNAc,β-D-GlcUA, andα-L-IdoUA with numbering used throughout the paper.

Table 1.

B3LYP6311ppdd//B3LYP/6-31+G(d) relative energies for ring and gg/gt/tg conformations of GlcNAc and GalNAc derivatives.

| Molecule/conformation | ΔE(4C1), kcal/mol | ΔE (1C4), kcal/mol | ΔE (2S0), kcal/mol | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharides | gg | gt | tg | gg | gt | tg | gg | gt | tg |

| GlcNAc | 2.02 | 1.77 | 0 | 10.17 | 6.85 | 10.31 | 2.81 | 4.28 | 11.66 |

| M-GlcNAc | 3.40 | 2.72 | 1.09 | 5.67 | 2.01 | 6.04 | 1.67 | 0 | 7.40 |

| GlcNAcPCM | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0 | 7.83 | 6.39 | 8.29 | 4.04 | 4.25 | 9.65 |

| M-GlcNAcPCM | 4.02 | 2.55 | 0 | 3.11 | 4.28 | 6.97 | 4.81 | 3.02 | 8.22 |

| GlcNAc(4S) | 7.77 | 8.30 | 0 | 19.19 | 14.61 | 14.70 | 7.00 | 15.05 | 4.77 |

| M-GlcNAc(4S) | 16.46 | 13.76 | 0 | 19.37 | 15.11 | 15.10 | 1.71 | 15.94 | 8.22 |

| GlcNAc(4S)PCM | 3.31 | 3.31 | 0 | 10.04 | 9.15 | 8.38 | 3.98 | 7.33 | 4.38 |

| M-GlcNAc(4S)PCM | 5.26 | 2.83 | 0 | 8.61 | 6.61 | 6.44 | 4.59 | 5.65 | 6.28 |

| GlcNAc(6S) | 0.22 | 0 | 10.14 | 8.98 | 16.84 | 19.47 | 22.93 | 14.08 | 14.49 |

| M-GlcNAc(6S) | 6.94 | 3.45 | 0 | 1.30 | 12.49 | 11.76 | 15.04 | 11.53 | 16.06 |

| GlcNAc(6S)PCM | 0.27 | 0 | 1.52 | 7.18 | 5.28 | 6.83 | 8.51 | 4.62 | 6.06 |

| M-GlcNAc(6S)PCM | 0 | 0.35 | 2.46 | 2.67 | 2.66 | 2.56 | ≥4C1 | 4.1 | 5.79 |

| GlcNAc(46S) | 0 | 6.13 | 1.89 | 44.14 | 29.03 | 21.05 | 17.59 | 37.31 | 14.50 |

| M-GlcNAc(46S) | 11.96 | 7.90 | 0 | 23.16 | 24.90 | 12.29 | ≥4C1 | 28.70 | 0.49 |

| GlcNAc(46S)PCM | 1.61 | 3.78 | 0 | 12.45 | 9.27 | 8.28 | 9.44 | 11.52 | 10.78 |

| M-GlcNAc(46S)PCM | 3.71 | 4.65 | 0 | 8.86 | 8.89 | 4.56 | 7.33 | 8.32 | 1.75 |

| GalNAc | 0 | 2.03 | 3.67 | 9.29 | 8.88 | 12.10 | 0.78 | 6.98 | 10.95 |

| M-GalNAc | 0 | 2.07 | 2.81 | 3.99 | 3.60 | 5.95 | 3.43 | 4.51 | 4.09 |

| GalNAcPCM | 0 | 1.04 | 2.40 | 8.55 | 8.40 | 8.68 | 3.78 | 6.64 | 9.39 |

| M-GalNAcPCM | 0 | 1.99 | 3.70 | 5.74 | 5.50 | 6.11 | 7.36 | 6.77 | 6.98 |

| GalNAc(4S) | 7.77 | 8.30 | 0 | 19.19 | 14.61 | 14.70 | 7.00 | 15.05 | 4.77 |

| M-GalNAc(4S) | 4.99 | 0.80 | 0 | 10.43 | 26.57 | 15.24 | 7.22 | 24.22 | 7.79 |

| GalNAc(4S)PCM | 0 | 2.96 | 2.09 | 9.57 | 12.48 | 9.28 | 3.90 | 11.29 | 5.00 |

| M-GalNAc(4S)PCM | 0 | 0.31 | 3.09 | 7.25 | 11.13 | 8.31 | 6.21 | 8.59 | 4.45 |

| GalNAc(6S) | 0 | 4.69 | 15.80 | 10.42 | 20.96 | 20.91 | 23.99 | 20.26 | 21.75 |

| M-GalNAc(6S) | 3.14 | 0 | 5.86 | 11.79 | 11.01 | 5.44 | 12.10 | 10.36 | 10.23 |

| GalNAc(6S)PCM | 0 | 0.81 | 0.20 | 6.09 | 5.13 | 5.44 | 12.88 | 7.71 | 7.42 |

| M-GalNAc(6S)PCM | 0.82 | 3.13 | 0 | 4.04 | 4.39 | 5.44 | 9.48 | 5.42 | 3.09 |

| GalNAc(46S) | 0 | 6.15 | 6.43 | 5.60 | 29.94 | 25.15 | 3.48 | 19.74 | 3.13 |

| M-GalNAc(46S) | 3.14 | 8.75 | 0 | 5.11 | 22.36 | 13.03 | 4.59 | 12.43 | 15.29 |

| GalNAc(46S)PCM | 1.50 | 2.09 | 0 | 6.94 | 9.19 | 16.43 | 4.55 | 13.68 | 4.90 |

| M-GalNAc(46S)PCM | 0 | 2.35 | 2.74 | 5.13 | 6.53 | 10.39 | 11.72 | 6.32 | 2.99 |

Relative energies were calculated using the energy of the most stable conformation for the same molecule as a reference for in vacuo and PCM solvent model (marked with PCM subscript).

4C1: The ring conformation changed to 4C1 during geometry optimization.

Table 2.

B3LYP6311ppdd//B3LYP/6-31+G(d) relative energies for ring conformations of IdoUA and GlcUA derivatives.

| Molecule/conformation | ΔE (4C1), kcal/mol | ΔE (1C4), kcal/mol | ΔE (2S0), kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|

| GlcUA | 0.88 | 0 | 3.42 |

| M-GlcUA | 0 | 0.70 | 5.12 |

| GlcUAPCM | 0 | 1.69 | 3.11 |

| M-GlcUAPCM | 0 | 6.23 | 6.93 |

| GlcUA(2S) | 1.11 | 4.00 | 0 |

| M-GlcU(2S) | 0 | 5.29 | 6.84 |

| GlcUA(2S)PCM | 1.25 | 7.51 | 0 |

| M-GlcU(2S)PCM | 0 | 3.71 | 7.84 |

| GlcU(3S) | 4.44 | 0 | 1.93 |

| M-GlcU(3S) | 0 | 2.34 | 0.73 |

| GlcU(3S)PCM | 6.78 | 3.65 | 0 |

| M-GlcU(3S)PCM | 0 | 11.09 | 1.29 |

| GlcUA(23S) | 7.94 | 13.14 | 0 |

| M-GlcUA(23S) | 0 | 14.86 | 5.83 |

| GlcUA(23S)PCM | 5.82 | 10.89 | 0 |

| M-GlcUA(23S)PCM | 0 | 8.87 | 1.62 |

| IdoUA | 0 | 2.00 | 6.53 |

| M-IdoUA | 0 | 2.33 | 6.64 |

| IdoUAPCM | 0 | 1.54 | 5.59 |

| M-IdoUAPCM | 0 | 1.54 | 4.01 |

| IdoUA(2S) | 0.28 | 0 | 5.78 |

| M-IdoUA(2S) | 2.77 | 0 | 7.18 |

| IdoUA(2S)PCM | 0 | 4.71 | 7.18 |

| M-IdoUA(2S)PCM | 1.50 | 0 | 3.50 |

| IdoUA(3S) | 0 | 19.64 | 22.68 |

| M-IdoUA(3S) | 0 | 21.36 | 24.17 |

| IdoUA(3S)PCM | 0 | 1.99 | 2.94 |

| M-IdoUA(3S)PCM | 0 | 1.87 | 2.94 |

| IdoUA(23S) | 0 | 0.70 | 0.46 |

| M-IdoUA(23S) | 0 | 11.18 | 6.44 |

| IdoUA(23S)PCM | 0 | 5.55 | 7.57 |

| M-IdoUA(23S)PCM | 0 | 7.82 | 4.38 |

Relative energies were calculated using the energy of the most stable conformation for the same molecule as a reference for in vacuo and PCM solvent model (marked with PCM subscript).

First, the molecules were built in MOE [32] in 1C4, 4C1, and 2S0 ring conformations. For Glc/GalNAc sulfated derivatives gt, tg, and gg conformations were built corresponding to the values of dihedral angle ω = (O6–C6–C5–O5) of ~300°, ~60°, and ~180°, respectively [10]. Na+ counterions were manually added to the systems with a nonzero net charge, and their positions were subsequently optimized by AMBER99 force field in MOE. The geometry optimization of these structures was carried out with GAUSSIAN 09 [33] using B3LYP functional [34] with 6-31+G(d) basis set. Single point energies were calculated using the B3LYP6311ppdd method, which was shown to be appropriate for energy calculations for carbohydrates [35]. For each monosaccharide, the relative energies were calculated using the energy of the most stable conformation as reference. GIAO methodology implemented within GAUSSIAN [36] was used to calculate NMR parameters: B3LYP6311+G(2d,p) for chemical shifts and B3LYP/aug-cc-pVDZ for spin-spin coupling constants, as these levels of theory demonstrated highest reliability in the calibration studies [37, 38]. TMS (tetramethylsilane) was used as a reference to calculate 13C- and 1H-chemical shifts. For the calculations carried out in solvent, PCM solvent model [39] was used.

2.2. Molecular Dynamics Calculations

For MD simulations, the GLYCAM06 force field [40] implemented in the AMBER 11 package [41] was used for GAGs. For sulfated residues, sulfate atomic charges for HA and CS derivatives residue libraries were obtained from RESP by fitting calculations at the level of 631(d)G for methylsulfate and introduced into the corresponding GLYCAM libraries. All the monosaccharides were modeled in the 4C1 ring conformation as it was suggested by our results (see Section 3.1). Prior to the simulation, GAG monosaccharides were solvated within an octahedral TIP3PBOX of 15 Å distance to the sides of the periodic unit, and counterions were added when required. The system was minimized and equilibrated as described before [42] and simulated for 50 ns in NTP ensemble. For MD simulations of GAGs hexasaccharides, the structures available in the PDB for octameric HA (PDB ID: 2BVK, NMR) and hexameric CS4 (PDB ID: 1CS4, fiber diffraction) were used as templates for modeling of the following HA and CS derivatives: (GlcUA-GlcNAc)3, (GlcUA-GlcNAc(4S))3, (GlcUA-GlcNAc(6S))3, (GlcUA-GlcNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(2S)-GlcNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(3S)-GlcNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(23S)-GlcNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA-GalNAc)3, (GlcUA-GalNAc(4S))3, (GlcUA-GalNAc(6S))3, (GlcUA-GalNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(2S)-GalNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(3S)-GalNAc(46S))3, and (GlcUA(23S)-GalNAc(46S))3. The MD simulations for these GAGs were carried out for 20 ns, and the obtained data for three monosaccharide units within each hexasaccharide were averaged to be compared with the data on free monosaccharides. The trajectories analysis was done using the ptraj module of AMBER 11. For the analysis of the dihedral angle ω = (O6–C6–C5–O5) for Glc/GalNAc sulfated derivatives, gg, gt, and tg, conformations were defined for ω in the ranges of [−120°; 0°), [0°; 120°), and [−180°; −120°) ∪ [120°; 180°), respectively.

2.3. NMR Measurements

All NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz spectrometer operating at 600.13 MHz 1H resonance frequency equipped with a 5 mm TBI triple resonance probehead with Z-gradient or on a Bruker Avance I 700 MHz spectrometer operating at 700.18 MHz 1H resonance frequency equipped with a triple resonance cryo-probehead at 37°C in D2O with TSP as a reference (set to 0 ppm for 1H and 13C chemical shifts). The resonance assignments were based on COSY, J-modulated, and HSQC 2D spectra. To account for strong coupling effects, the chemical shifts and 3JH-H were extracted by fitting the experimental 1D spectra with a self-written Octave script [43].

Statistical analysis of data was carried out with the R-package [44].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Conformational Preferences of the Analyzed Monosaccharides

The geometries of GlcNAc, GalNAc, GlcUA, and IdoUA monosaccharides and their sulfated derivatives were optimized and their single point energies were calculated for three ring conformations (4C1, 1C4, 2S0) and, in addition, for the gg/gt/tg conformations for N-acetylated saccharides (Tables 1 and 2). The obtained results represent in vacuo and PCM implicit solvent models for nonmethylated and O1-methylated monosaccharides, where the latter is used as the simplest model for the glycosidic linkage in GAGs. Using the same level of theory for single point energy calculations (B3LYP6311ppdd) but a different level for geometry optimization (6-31+G(d) versus B3LYP6311ppdd), we were able to nicely reproduce relative energies for M-IdoUA(2S) ring conformers obtained in the work of Hricovíni [26] (7.690 versus 7.18; 2.775 versus 2.77 kcal/mol, for the differences between the most stable 1C4 and 2S0; 4C1 conformations, resp.). The positions of counterions were also predicted very similarly to the positions in the aforementioned study. If the counterions were not used for the calculations, though the geometry of M-IdoUA(2S) was correctly obtained, energetic comparison of the conformations failed. For example, when not using counterions, the 4C1 ring conformation was observed to be the most stable (data not shown). This suggests a strong impact of the ions on the ring puckering due to the net electrostatic effect in a not neutralized system. Interestingly, final point energies are also affected by the counterion positions occupied after the geometry minimization. In case of many negatively charged groups as, for example, for double sulfated GlcUA or IdoUA, these positions could be not unique. This point is important to consider when quantitatively analyzing the results represented in Tables 1 and 2.

For GlcNAc and GalNAc derivatives, all the data show the preference for the 4C1 ring conformation (except for M-GlcNAc in vacuo, where 2S0 was found to be the most stable with a relatively low difference of 1.09 kcal/mol to the 4C1 conformation) (Table 2). This agrees with the previous long MD studies for GlcNAc [22] and the experimental structures of free chondroitin sulfate 4 (PDB ID: 1CS4) and hyaluronic acid (PDB IDs: 1HYA, 2HYA, 3HYA, 4HYA, 1HUA, 2BVK). In general, the probability of adopting 2S0 was calculated to be higher than for 1C4 for the optimized structures. When analyzing gg/gt/tg conformations of ω dihedral angle, there is an essential dependence on the model used for the calculations. Nevertheless, for both in vacuo and implicit solvent calculations, GlcNAc derivatives prefer tg conformation, while GalNAc derivatives are more prone to the gg conformation, which is not in agreement with the expected gauche effect for these molecules. This inconsistency of QM methods was also observed previously in the work of Kirschner and Woods. These authors explain the limitation of this methodology in terms of disregarding explicit solvent [10]. Indeed, the tg conformation for structure of GlcNAc obtained by QM is favourable due to the formation of a hydrogen bond between O6 and HO4 atoms, which in the presence of explicit solvent could be disrupted due to the interaction with water molecules. In case of GlcNAc(4S) and GlcNAc(6S), the strong interaction between sulfate groups and hydrogens of the hydroxyl groups defines the most favourable ω dihedral angle conformation. Besides that, the positions of counterions are especially important: for GlcNAc(46S) two Na+ ions are coordinated between sulfate groups in the positions 4 and 6 and, therefore, strongly stabilize the tg conformation. For GalNAc, the formation of the hydrogen bond between O6 and HO4 atoms is more probable in the gg conformation. For the sulfated GalNAc derivatives, the positions of Na+ ions are crucial for the selection of the most energetically favourable ω dihedral angle conformation. Methylation of the O1 decreases the opportunity for intramolecular hydrogen bonding and, therefore, also influences the gg/gt/tg conformational distribution.

For GlcUA sulfated derivatives, the conformational dependence on both sulfation pattern and the model used for calculations is clearly observed (Table 2). For GlcUA monosaccharide, all methods find the 4C1 ring conformation highly probable. In vacuo calculations propose coexistence of this conformation together with the 1C4 conformation with the prevalence of the latter for the case when O1 position is not methylated (difference in energy of two conformations of 1 kcal/mol corresponds to their probabilities ratio of 85 : 15). This agrees with the experimental structures of free hyaluronic acid (PDB IDs: 1HYA, 2HYA, 3HYA, 4HYA, 1HUA, 2BVK) and data from MD simulations [23]. For sulfated derivatives of GlcUA, all O1-methylated monosaccharides are found to be the most stable in the 4C1 conformation independently of the solvent use in the calculations. For M-GlcUA(3S), the differences in energies between 2S0 and 4C1 are quite low suggesting possible coexistence of these conformations. For all unmethylated sulfated derivatives of GlcUA (except for in vacuo calculation for GlcUA(3S), where the 1C4 conformation was the most stable), the 2S0 conformation is preferred.

For IdoUA derivatives, there is a much higher consistency within the results obtained by different methods, though the relative differences between the conformations stabilities for different methods are still relatively high (e.g., IdoUA(3S) in vacuo versus implicit solvent) (Table 2). All the derivatives except IdoUA(2S) prefer the 4C1 conformation, whereas IdoUA(2S) prefers the 1C4 conformation. Interestingly, in the free heparin crystal structure (PDB ID: 1HPN), IdoUA(2S) monosaccharide units are observed in 2S0 and 1C4 but not in the 4C1 conformation.

All these QM data for the analyzed monosaccharides suggest that the results obtained for distinct models (with respect to solvent and O1-methylation) should be considered with caution, especially when compared to the data on conformational preferences for sugar rings and gg/gt/tg for these monosaccharides within long GAG polymers.

3.2. MD Conformational Analysis of ω Dihedral for Glc/GalNAc Derivatives

As it was pointed out in the previous section, QM approaches experience severe difficulties in the quantitative description of ω dihedral angle conformations. In contrast to QM calculations, MD simulations are able not only to take into account solvent explicitly but also to gain insights into internal motions of the molecules and, therefore, yield more complete information about the conformational space than the data from QM or NMR experiments.

According to the experimental data, glycopyranosyl derivatives tend to adopt gg and gt conformations (known as gauche effect) with the ratios of gg/gt/tg in the percentage range ~60–70 : 30–40 : 0–5 per conformation, whereas galactopyranosyl derivatives adopt less gg and gain in tg conformational content with the corresponding ratios of 10–20 : 45–55 : 30–40 [45–47]. MD simulations for GlcNAc and GalNAc nonmethylated derivatives in general agree with this trend and are able to reproduce the gauche effect (Table 3). For GlcNAc derivatives, sulfation in the 4th position increases the preference to the gt conformation, and sulfation in the 6th position makes gg more favourable. For GalNAc derivatives, sulfation in the 4th position does not make any significant effect, while sulfation in position 6 makes the tg conformation significantly more favourable. This could be explained in terms of the dipole interactions between the sulfate and hydroxyl groups in positions 4 and 6. For the data interpretation, several aspects should be taken into account: (i) the sulfation of the hydroxyl group changes the direction of the corresponding dipole to the opposite one; (ii) the absolute value of the OH group dipole is lower than the one of O–SO3; (iii) C4–O4 is in equatorial configuration for GlcNAc and in axial configuration for GalNAc; (iv) the flexibility of the group in position 6 is higher than the flexibility of the group in position 4; (v) the repulsive strength of the dipole-dipole interaction is defined by the dipole's absolute value, the distance between them, and their mutual orientation. With these considerations, the increase of the gg conformation population for GlcNAc(6S) in comparison to GlcNAc could be explained by more favourable interaction of O4–H dipole with O6–SO3 dipole in comparison to weak repulsion between two O–H dipoles in the nonsulfated derivative since the angle and distance between these dipoles are lower in gg in comparison to the gt conformation. On the contrary, the decrease of the gg conformation population of GlcNAc(46S) in comparison to GlcNAc(6S) could be explained by the stronger repulsion between two O4/O6–SO3 dipoles in the case of the GlcNAc(46S) molecule. For GalNAc derivatives, the gg conformation is sterically less accessible because the C4–O4 configuration is different to GlcNAc, and the O4–H group would overlap with the O6–SO3 group in this conformation. Here, the tg conformation is favourable when both O4 and O6 are sulfated because the angle between these two dipoles is closer to 90° than for the gt conformation. However, this explanation in terms of only two dipoles interaction cannot be used when comparing the differences in preferences of GalNAc(4S) and GalNAc(6S).

Table 3.

ω dihedral angle gg/gt/tg (%) conformations distribution for GlcNAc/GalNAc monosaccharide derivatives.

| Monosaccharide | gg | gt | tg |

|---|---|---|---|

| GlcNAc | 50 | 48 | 2 |

| GlcNAc(4S) | 38 | 59 | 3 |

| GlcNAc(6S) | 78 | 12 | 11 |

| GlcNAc(46S) | 59 | 29 | 12 |

| GalNAc | 7 | 76 | 16 |

| GalNAc(4S) | 5 | 81 | 14 |

| GalNAc(6S) | 3 | 19 | 78 |

| GalNAc(46S) | 1 | 31 | 68 |

We also compared these data for monosaccharides MD simulations with the results obtained for the corresponding monosaccharide blocks within the hexameric GAGs (Table 4). When only the sulfation of GAGs changes, the populations of the ω dihedral angle conformation change very similarly to the ones in monosaccharides for HA, HA4, HA6, and HA46 and for CS_de, CS4, CS6, and CS46, respectively. Sulfation of the GlcUA within hexameric HA and CS derivatives affects the conformations of GlcNAc and GalNAc46 for GlcUA(2S) and GlcUA(3S), respectively. This suggests a pronounced mutual influence of electrostatic environment of the monosaccharide units within the polymer on their ω dihedral angle conformations but a weak influence of the polymerization via O1 and O3, respectively.

Table 4.

ω dihedral angle gg/gt/tg (%) conformations distribution for GlcNAc/GalNAc monosaccharide units within hexameric GAGs.

| 1GAG | gg | gt | tg |

|---|---|---|---|

| HA | 53 | 45 | 2 |

| HA4 | 61 | 37 | 2 |

| HA6 | 87 | 11 | 2 |

| HA46 | 57 | 40 | 4 |

| HA462′ | 83 | 16 | 1 |

| HA463′ | 59 | 30 | 11 |

| HA462′3′ | 34 | 54 | 12 |

|

| |||

| CS_de | 8 | 80 | 12 |

| CS4 | 6 | 86 | 9 |

| CS6 | 6 | 56 | 38 |

| CS46 | 2 | 77 | 21 |

| CS462′ | 0 | 81 | 19 |

| CS463′ | 2 | 53 | 45 |

| CS462′3′ | 2 | 57 | 42 |

HA, HA4, HA6, HA46, HA462′, HA463′, HA462′3′, CS, CS4, CS6, CS46, CS462′, CS463′, CS462′3′ stay for (GlcUA-GlcNAc)3, (GlcUA-GlcNAc(4S))3, (GlcUA-GlcNAc(6S))3, (GlcUA-GlcNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(2S)-GlcNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(3S)-GlcNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(23S)-GlcNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA-GalNAc)3, (GlcUA-GalNAc(4S))3, (GlcUA-GalNAc(6S))3, (GlcUA-GalNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(2S)-GalNAc(46S))3, (GlcUA(3S)-GalNAc(46S))3, and (GlcUA(23S)-GalNAc(46S))3, respectively.

3.3. Chemical Shifts and 3 J H-H Calculations

For 13C and 1H chemical shifts and 3JH-H GIAO calculations, we used GlcNAc, GalNAc, GlcUA, and IdoUA monosaccharides and their sulfated derivatives, both nonmethylated and O1-methylated, in the conformations listed in Section 3.1. These data (see Supplementary Tables 1–17 available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/808071/) could be used as QM NMR parameters dictionary for monosaccharides with a different sulfation pattern.

Our analysis of 13C and 1H chemical shifts yields no significant dependence of these calculated NMR parameters neither on the conformations nor on O1-methylation (except for C1) (Supplementary Tables 1–12). In contrast, there are changes of chemical shifts occurring upon sulfation. In particular, 13C chemical shifts increase more than 5 ppm for C4 and slightly less than 5 ppm for C6 in case of GlcNAc and GalNAc sulfated monosaccharides. The same trend is observed in the experiments (Table 5), where the chemical shifts of the sulfated carbons C4 and C6 increased by 6 to 7 ppm. When C4 is sulfated, calculated chemical shifts of the adjacent C3 and C5 slightly drop, which is also observed in the experiments, where the similar chemical shift changes are observed for C5 when C6 is sulfated. In case of GlcUA and IdoUA sulfated derivatives, C2 and C3 chemical shifts similarly increase upon sulfation, while chemical shifts of adjacent carbons also drop. Our results allow for the conclusion that the calculated changes in the chemical shifts upon sulfation agree well with the experimental data. However, the variance within the values corresponding to different individual conformations is substantial. For example, for GlcUA 1C4 conformation, the increase of the chemical shift for C3 is observed upon the sulfation of C3, which contradicts the general observation derived from the averaging per all conformations. This makes the use of these values challenging for the practical purposes of the direct NMR spectra assignment. Based on the presented data, the expected error range for 13C chemical shifts is up to 5 ppm, which is similar to the differences found for the sulfated carbons. For the 1H chemical shifts, we also observe the significant increase of about 0.5 ppm for the values of the hydrogens bound to the carbons being sulfated as well as a slight increase of chemical shifts of the hydrogens bound to the carbons adjacent to the sulfated ones. Our experimental data for the C4-sulfation of GlcNAc and GalNAc qualitatively support the data obtained in our calculations (Table 5). For both 13C and 1H chemical shifts, we clearly observe experimentally validated qualitative trends, which might further allow for a quantitative comparison of QM obtained values with experimental data. The variance of the observed chemical shifts within the groups of different conformations is about 0.5 ppm and, therefore, comparable to the experimentally observed differences induced by sulfation.

Table 5.

Experimentally versus computationally obtained chemical shifts (ppm).

| Atom | GlcNAc | GlcNAc(6S) | GalNAc | GalNAc(4S) | GalNAc(6S) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. | GIAO | Exp. | GIAO | Exp. | GIAO | Exp. | GIAO | Exp. | GIAO | |

| C1 | 97.77 | 107.00 | 97.90 | 104.27 | 98.27 | 107.12 | 98.16 | 101.40 | 98.28 | 107.79 |

| C2 | 59.60 | 64.30 | 59.58 | 65.23 | 56.62 | 62.65 | 56.98 | 60.46 | 56.45 | 62.80 |

| C3 | 76.74 | 82.51 | 76.61 | 82.45 | 73.99 | 77.19 | 72.81 | 80.51 | 73.79 | 77.32 |

| C4 | 72.76 | 80.69 | 72.58 | 78.70 | 70.77 | 74.61 | 78.64 | 77.33 | 70.48 | 72.60 |

| C5 | 78.79 | 84.15 | 76.69 | 87.11 | 78.03 | 78.54 | 77.22 | 81.88 | 75.63 | 79.38 |

| C6 | 63.64 | 69.17 | 70.13 | 71.15 | 64.06 | 68.44 | 63.85 | 65.28 | 70.30 | 70.57 |

| C7 | 177.59 | 183.04 | — | 184.56 | — | 182.75 | 177.53 | 182.10 | — | 182.71 |

| C8 | 25.03 | 23.96 | 24.93 | 24.01 | 24.97 | 24.08 | 25.08 | 24.96 | 25.08 | 24.07 |

| H1 | 4.72 | 4.65 | 4.74 | 4.88 | 4.65 | 4.45 | 4.72 | 4.94 | 4.67 | 4.46 |

| H2 | 3.67 | 3.78 | 3.70 | 3.67 | 3.88 | 3.94 | 3.89 | 4.00 | 3.89 | 3.90 |

| H3 | 3.54 | 3.36 | 3.56 | 3.41 | 3.73 | 3.51 | 3.88 | 3.88 | 3.75 | 3.42 |

| H4 | 3.46 | 3.17 | 3.52 | 3.27 | 3.94 | 4.35 | 4.70 | 5.21 | 4.00 | 4.24 |

| H5 | 3.47 | 3.29 | 3.68 | 3.82 | 3.70 | 3.91 | 3.82 | 3.95 | 3.94 | 3.64 |

| H6 | 3.75 | 3.84 | 4.22 | 4.25 | 3.77 | 4.15 | — | 3.84 | 4.20 | 4.12 |

| H7 | 3.91 | 3.99 | 4.35 | 4.69 | 3.80 | 4.33 | — | 4.27 | 4.23 | 4.77 |

| H9, 10, 11 | 2.05 | 2.05 | 2.05 | 2.12 | 2.06 | 2.05 | 2.06 | 2.11 | 2.06 | 2.02 |

For 3JH-H we obtain slight qualitative differences depending on the sulfation pattern (Supplementary Tables 13–17), which is similarly observed by the experiment (Table 6). The variance of the 3JH-H for the protons bound to the carbons C1–C5 of the ring is up to 2-3, whereas the variance of 3JH-H for other proton pairs (available for GlcNAc and GalNAc derivatives) is higher and reaches the values of 4-5. The variance of the 3JH-H grouped by ring conformations decreases down to 1 for the protons bound to the carbons C1–C5, which is similar to the corresponding experimental accuracy. In case of GlcNAc derivatives, especially high variance for the 2S0 ring conformation is observed. This is due to the fact that the geometry optimization starting from this ring conformation for M-GlcNAc(6S) and M-GlcNAc(46S) ended up in the 4C1 conformation, whereas for some molecules dramatic geometrical distortions were found (they correspond to high energies in Table 2). Except for GlcNAc derivatives in the 2S0 conformation, clear trends for 3JH-H of H1-H2, H2-H3, H3-H4, and H4-H5 are observed, which allows significantly distinguishing different ring conformations within the applied method. In particular, GlcUA and IdoUA derivatives have four high 3JH-H (~5–8) that correspond to the 4C1 conformation, four low (~2–4) to the 1C4 conformation, and three low and one high to the 2S0 conformation, respectively. For GlcNAc and GalNAc derivatives, epimeric C4 could be clearly distinguished for the corresponding H3-H4 and H4-H5 3JH-H for the most energetically favourable 4C1 conformation, which is qualitatively in agreement with the experimental data but quantitatively underestimated (Table 6). The values for gg/gt/tg conformations for each ring conformation clearly differ (Supplementary Tables 13–16), which corresponds to different geometries and could be used as a dictionary for these parameters. Therefore, calculations of 3JH-H could be used for assistance in NMR assignments in cases where ring conformation and sulfation patterns are not well defined.

Table 6.

Experimentally versus computationally obtained 3JH-H (Hz).

| Protonpair | GlcNAc | GlcNAc(6S) | GalNAc | GalNAc(4S) | GalNAc(6S) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. | GIAO | Exp. | GIAO | Exp. | GIAO | Exp. | GIAO | Exp. | GIAO | |

| H1-H2 | 8.42 | 5.59 | 8.32 | 5.74 | 8.17 | 5.53 | 8.30 | 5.27 | 8.09 | 5.63 |

| H2-H3 | 10.46 | 7.68 | 10.39 | 7.42 | 10.92 | 7.87 | — | 8.50 | 10.86 | 7.69 |

| H3-H4 | 8.82 | 5.89 | 8.99 | 6.07 | 3.36 | 3.90 | 2.50 | 3.71 | 3.50 | 3.73 |

| H4-H5 | 9.53 | 6.69 | 10.02 | 7.41 | 1.03 | 2.08 | — | 2.85 | 0.85 | 1.94 |

| H5-H6 | 2.40 | 2.56 | 1.84 | 0.54 | 4.41 | 5.65 | — | 6.84 | 4.77 | 4.14 |

| H5-H7 | 5.67 | 6.70 | 5.59 | 4.60 | 7.79 | 6.40 | — | 4.90 | 7.55 | 7.89 |

NMR parameters calculated by GIAO approaches (chemical shifts, 3JH-H) qualitatively reflect the sulfation, ring, and ω dihedral conformations (3JH-H). However, the direct and quantitative use of the calculated NMR parameters for experimental data assignment could be limited due to the intrinsic error of the method.

3.4. Comparison of the Calculated NMR Parameters with Experimental Data for GlcNAc, GlcNAc(6S), GalNAc, GalNAc(4S), and GalNAc(6S)

In order to estimate the practical applicability of the used computational methods for NMR parameter calculations, we compared the calculated chemical shifts and 3JH-H with the available experimental data obtained by NMR for β-GlcNAc, β-GlcNAc(6S), β-GalNAc, β-GalNAc(4S), and β-GalNAc(6S) (Tables 5 and 6). The Pearson and Spearman correlations between the calculated and experimental data and the mean error of the theoretical methods are 0.994, 0.959, and 4.34 ppm for 13C chemical shifts, 0.961, 0.933, and 0.05 ppm for 1H chemical shifts, and 0.899, 0.840, and 1.3 Hz for 3JH-H, respectively (Table 7). For 13C chemical shifts, the theoretically obtained absolute values for all analyzed saccharides are systematically overestimated for C1–C7 except for C4 of GalNAc(4S) and underestimated for about 1 ppm for C8 (Table 5). The Pearson correlations between experimental and theoretical values are very high for 13C chemical shifts, which nevertheless could be partially explained in terms of high differences between the values for C8 in comparison to other values. Spearman correlations were found to be 1.0 for four out of five monosaccharides, which represents a promising result for ranking the peaks for 13C spectra. At the same time, the mean error could be too high for distinguishing carbons C1–6 in case the most probable conformation of the molecule is a priori unknown. For 1H chemical shifts, we obtained systematic underestimation of H3 and overestimation of H7 chemical shifts by the applied GIAO approach, while for other protons both overestimation and underestimation of experimental values were observed (Table 5). Both Pearson and Spearman correlations for 1H chemical shifts are lower than for 13C chemical shifts but the low mean error seems to be more promising for potential use of these chemical shifts for assisting NMR assignment. In addition, if more NMR data for the same class of molecules would be available, the mean and intercept of the linear regression between theoretical and experimental values could be used for scaling and inter/extrapolation of computational data in order to further minimize the mean error of the predicted values. For 3JH-H, the correlations are slightly lower and mean errors are higher. The values calculated by GIAO3JH-H values for H1-H2, H2-H3 for all analyzed molecules and for H4-H5 for GlcNAc/GlcNAc(6S) are underestimated, while the corresponding 3JH-H values for H4-H5 for GalNAc/GalNAc(6S) are overestimated (Table 6). For H3-H4, H5-H6, and H5-H7 both theoretical overestimation and underestimation in comparison to the experiment were obtained. Scaling of the calculated 3JH-H based on the further obtained experimental data would assist the creation of a quantitative procedure to be used in NMR assignment for this class of molecules.

Table 7.

Comparison of the experimental and theoretical data on NMR parameters.

| GlcNAc | GlcNAc(6S) | GalNAc | GalNAc(4S) | GalNAc(6S) | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R Pearson, 13C | 0.999 (0.998) | 0.994 | 0.995 | 0.993 (0.998) | 0.995 | 0.994 (0.996) |

| R Spearman, 13C | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.893 (0.929) | 1.000 | 0.959 (0.965) |

| R Pearson, 1H | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.932 | 0.991 | 0.939 | 0.961 |

| R Spearman, 1H | 1.000 | 0.976 | 0.905 | 0.886 | 0.929 | 0.933 |

| ΔΔppm, 13C | 5.66 (5.63) | 5.19 | 3.96 | 3.13 (4.39) | 3.79 | 4.34 (4.38) |

| ΔΔppm, 1H | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| R Pearson, 3JH-H | 0.836 | 0.985 | 0.933 | — | 0.923 | 0.899 |

| R Spearman, 3JH-H | 0.657 | 1.000 | 0.829 | — | 0.829 | 0.840 |

| ΔΔppm, 3JH-H | 1.7 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

The analysis for 13C chemical shifts is done without the consideration of C7 chemical shifts. The values obtained with the consideration of C7 chemical shifts from GlcNAc and GalNAc(4S) are given in the parenthesis.

3.5. Sulfation Degree and Methyl-Group Chemical Shifts in Acetyl Group of Glc/GalNAc Derivatives

According to our computational data, despite the limitations for the chemical shifts calculations described above, we can clearly see a general increase of the H9/H10/H11 chemical shift value averaged for all gg/tg/gt conformations with an increase in the sulfation of the monosaccharides (Supplementary Table 18), whereas, for protons H10 and H11, there is only one significant increase of the chemical shift when a monosaccharide is sulfated once; the increase of the chemical shift value for proton H9 is significant in the order Glc/GalNAc, Glc/GalNAc(4S), Glc/GalNAc(6S), and Glc/GalNAc(46S) (Supplementary Table 19). These results show that, despite the expected moderate accuracy in the prediction of chemical shifts, the trend for such an important parameter as net sulfation of the monosaccharide being analyzed by the calculations of the methyl-group chemical shifts in the acetyl group of Glc/GalNAc derivatives agrees with the trend observed by NMR experimental data for the polymeric GAGs with different net sulfation degree.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we applied QM methodology in order to analyze the conformational space and NMR parameters (chemical shifts and 3JH-H) of GAG monosaccharide blocks. We investigated perspectives and limitations of the applicability of GIAO methodology for the assistance to NMR analysis of GAGs. We observed that in such conformational analysis the choice of the model for QM calculation has a significant impact on the results. Comparison of our QM and MD results for gg/gt/tg conformations distribution for GlcNAc and GalNAc stressed the importance of the use of explicit solvent for conformational analysis of saccharides by theoretical approaches. We found that calculated chemical shifts could be used for the analysis of the sulfation position of GAG monosaccharide blocks as well as the net sulfation, whereas 3JH-H could be useful for both sulfation position and ring conformation analysis. Despite being promising, our results suggest that more experimental data are needed for optimization of the theoretically obtained parameters before being used to support NMR assignment.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Tables 1–12: The description should be "Chemical shifts calculated by GIAO approach".

Supplementary Tables 13–17: The description should be "Chemical shifts calculated by GIAO approach".

Supplementary Tables 13–16: The description should be "3JH-H calculated by GIAO approach".

Supplementary Table 18: The description should be "3JH-H calculated by GIAO approach".

Supplementary Table 19: 1H chemical shifts in CH3 of the acetyl group of Glc/GalNAc derivatives for gg/gt/tg conformations.

Supplementary Table 18: 1H chemical shifts in CH3 of the acetyl group of Glc/GalNAc derivatives.

Supplementary Table 19: 1H chemical shifts in CH3 of the acetyl group of Glc/GalNAc derivatives for gg/gt/tg conformations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the German Research Council (SFB-TRR67; A2, A6, A7). The authors would like to thank the ZIH at TU Dresden for providing high-performance computational resources and Ralf Gey for technical assistance. They acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Fund of the TU Dresden.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Sergey A. Samsonov and Stephan Theisgen contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1.Jackson RL, Busch SJ, Cardin AD. Glycosaminoglycans: Molecular properties, protein interactions, and role in physiological processes. Physiological Reviews. 1991;71(2):481–539. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.2.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindahl U, Li J-P. Interactions between heparan sulfate and proteins-design and functional implications. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 2009;276:105–159. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(09)76003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeMarco ML, Woods RJ. Structural glycobiology: a game of snakes and ladders. Glycobiology. 2008;18(6):426–440. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd TR, Skidmore MA, Guerrini M, et al. The conformation and structure of GAGs: recent progress and perspectives. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2010;20(5):567–574. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fadda E, Woods RJ. Molecular simulations of carbohydrates and protein-carbohydrate interactions: motivation, issues and prospects. Drug Discovery Today. 2010;15(15-16):596–609. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q, Brady JW. Anisotropic solvent structuring in aqueous sugar solutions. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1996;118(49):12276–12286. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taha HA, Roy P-N, Lowary TL. Theoretical investigations on the conformation of the β-D-arabinofuranoside ring. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2011;7(2):420–432. doi: 10.1021/ct100450s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagnotta SE, McLain SE, Soper AK, Bruni F, Ricci MA. Water and trehalose: How much do they interact with each other? Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2010;114(14):4904–4908. doi: 10.1021/jp911940h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vila Verde A, Campen RK. Disaccharide topology induces slowdown in local water dynamics. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2011;115(21):7069–7084. doi: 10.1021/jp112178c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirschner KN, Woods RJ. Solvent interactions determine carbohydrate conformation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(19):10541–10545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191362798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong Y, Bauer BA, Patel S. Solvation properties of N-acetyl-β-glucosamine: molecular dynamics study incorporating electrostatic polarization. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2011;32(16):3339–3353. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Almond A, Sheehan JK, Brass A. Molecular dynamics simulations of the two disaccharides of hyaluronan in aqueous solution. Glycobiology. 1997;7(5):597–604. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almond A, Brass A, Sheehan JK. Deducing polymeric structure from aqueous molecular dynamics simulations of oligosaccharides: predictions from simulations of hyaluronan tetrasaccharides compared with hydrodynamic and X-ray fibre diffraction data. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1998;284(5):1425–1437. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almond A, Sheehan JK. Glycosaminoglycan conformation: do aqueous molecular dynamics simulations agree with x-ray fiber diffraction? Glycobiology. 2000;10(3):329–338. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almond A, Sheenan JK. Predicting the molecular shape of polysaccharides from dynamic interactions with water. Glycobiology. 2003;13(4):255–264. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almond A, Brass A, Sheehan JK. Dynamic exchange between stabilized conformations predicted for hyaluronan tetrasaccharides: comparison of molecular dynamics simulations with available NMR data. Glycobiology. 1998;8(10):973–980. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.10.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sattelle BM, Shakeri J, Roberts IS, Almond A. A 3D-structural model of unsulfated chondroitin from high-field NMR: 4-sulfation has little effect on backbone conformation. Carbohydrate Research. 2010;345(2):291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cilpa G, Hyvönen MT, Koivuniemi A, Riekkola M-L. Atomistic insight into chondroitin-6-sulfate glycosaminoglycan chain through quantum mechanics calculations and molecular dynamics simulation. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2010;31(8):1670–1680. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samsonov SA, Pisabarro MT. Importance of IdoA and IdoA(2S) ring conformations in computational studies of glycosaminoglycan-protein interactions. Carbohydrate Research C. 2013;381:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin L, Hricovíni M, Deakin JA, Lyon M, Uhrín D. Residual dipolar coupling investigation of a heparin tetrasaccharide confirms the limited effect of flexibility of the iduronic acid on the molecular shape of heparin. Glycobiology. 2009;19(11):1185–1196. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angulo J, Ojeda R, De Paz J-L, et al. The activation of Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs) by glycosaminoglycans: influence of the sulfation pattern on the biological activity of FGF-1. ChemBioChem. 2004;5(1):55–61. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sattelle BM, Almond A. Is N-acetyl-d-glucosamine a rigid4C1 chair? Glycobiology. 2011;21(12):1651–1662. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sattelle BM, Hansen SU, Gardiner J, Almond A. Free energy landscapes of iduronic acid and related monosaccharides. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132(38):13132–13134. doi: 10.1021/ja1054143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babin V, Sagui C. Conformational free energies of methyl-α-L-iduronic and methyl-Β-D-glucuronic acids in water. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2010;132(10) doi: 10.1063/1.3355621.104108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gandhi NS, Mancera RL. Can current force fields reproduce ring puckering in 2-O-sulfo-α-l-iduronic acid? A molecular dynamics simulation study. Carbohydrate Research. 2010;345(5):689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hricovíni M. B3LYP/6-311++G** study of structure and spin-spin coupling constant in methyl 2-O-sulfo-α-l-iduronate. Carbohydrate Research. 2006;341(15):2575–2580. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hricovíni M, Scholtzová E, Bízik F. B3LYP/6-311++G** study of structure and spin-spin coupling constant in heparin disaccharide. Carbohydrate Research. 2007;342(10):1350–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hricovíni M. Effect of solvent and counterions upon structure and NMR spin-spin coupling constants in heparin disaccharide. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2011;115(6):1503–1511. doi: 10.1021/jp1098552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Smissen A, Hintze V, Scharnweber D, et al. Growth promoting substrates for human dermal fibroblasts provided by artificial extracellular matrices composed of collagen I and sulfated glycosaminoglycans. Biomaterials. 2011;32(34):8938–8946. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salbach J, Rachner TD, Rauner M, et al. Regenerative potential of glycosaminoglycans for skin and bone. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2011;90(6):625–635. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0843-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salbach J, Kliemt S, Rauner M, et al. The effect of the degree of sulfation of glycosaminoglycans on osteoclast function and signaling pathways. Biomaterials. 2012;33(33):8418–8429. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chemical Computing Group Inc, MOE v2005.06, 2006.

- 33.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.1. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009.

- 34.Becke AD. A new mixing of Hartree-Fock and local density-functional theories. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1993;98(2):1372–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Momany FA, Appell M, Willett JL, Schnupf U, Bosma WB. DFT study of α- and β-D-galactopyranose at the B3LYP/6-311++G** level of theory. Carbohydrate Research. 2006;341(4):525–537. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheeseman JR, Frisch MJ, Devlin FJ, Stephens PJ. Ab initio calculation of atomic axial tensors and vibrational rotational strengths using density functional theory. Chemical Physics Letters. 1996;252(3-4):211–220. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jain R, Bally T, Rablen PR. Calculating accurate proton chemical shifts of organic molecules with density functional methods and modest basis sets. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2009;74(11):4017–4023. doi: 10.1021/jo900482q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bally T, Rablen PR. Quantum-chemical simulation of 1H NMR spectra. 2. Comparison of DFT-based procedures for computing proton-proton coupling constants in organic molecules. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2011;76(12):4818–4830. doi: 10.1021/jo200513q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cossi M, Rega N, Scalmani G, Barone V. Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2003;24(6):669–681. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirschner KN, Yongye AB, Tschampel SM, et al. GLYCAM06: a generalizable biomolecular force field. carbohydrates. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2008;29(4):622–655. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Case D, Darden T, Cheatham T, et al. Amber 11 Users' Manual

- 42.Pichert A, Samsonov SA, Theisgen S, et al. Characterization of the interaction of interleukin-8 with hyaluronan, chondroitin sulfate, dermatan sulfate and their sulfated derivatives by spectroscopy and molecular modeling. Glycobiology. 2012;22(1):134–145. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Octave Community. GNU/Octave, 2012, http://www.gnu.org/software/octave/

- 44.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marchessault R, Perez S. Conformations of the hydroxymethyl group in crystalline aldohexopyranoses. Biopolymers. 1979;18(9):2369–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishida Y, Ohrui H, Meguro H. 1H-NMR studies of (6r)- and (6s)-deuterated d-hexoses: assignment of the preferred rotamers about C5C6 bond of D-glucose and D-galactose derivatives in solutions. Tetrahedron Letters. 1984;25(15):1575–1578. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohrui H, Nishida Y, Watanabe M, Hori H, Meguro H. 1H-NMR Studies on (6R)- and (6S)-deuterated (1–6)-linked disaccharides: assignment of the preferred rotamers about C5-C6 bond of (1–6)-disaccharides in solution. Tetrahedron Letters. 1985;26(27):3251–3254. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables 1–12: The description should be "Chemical shifts calculated by GIAO approach".

Supplementary Tables 13–17: The description should be "Chemical shifts calculated by GIAO approach".

Supplementary Tables 13–16: The description should be "3JH-H calculated by GIAO approach".

Supplementary Table 18: The description should be "3JH-H calculated by GIAO approach".

Supplementary Table 19: 1H chemical shifts in CH3 of the acetyl group of Glc/GalNAc derivatives for gg/gt/tg conformations.

Supplementary Table 18: 1H chemical shifts in CH3 of the acetyl group of Glc/GalNAc derivatives.

Supplementary Table 19: 1H chemical shifts in CH3 of the acetyl group of Glc/GalNAc derivatives for gg/gt/tg conformations.