Abstract

Background and Purpose

Recognition of stroke warning signs may reduce treatment delays. The purpose of this study was to evaluate contemporary knowledge of stroke warning signs and knowledge to call 9-1-1, among a nationally representative sample of women, overall and by race/ethnic group.

Methods

A study of cardiovascular disease awareness was conducted by the American Heart Association in 2012 among English speaking U.S. women >25 years identified through random digit dialing (N=1,205; 54% white, 17% black, 17% Hispanic, 12% other). Knowledge of stroke warning signs, and what to do first if experiencing stroke warning signs, was assessed by standardized open-ended questions.

Results

Half of women surveyed (51%) identified sudden weakness/numbness of face/limb on one side as a stroke warning sign; this did not vary by race/ethnic group. Loss of/trouble talking/understanding speech was identified by 44% of women; more frequently among white versus Hispanic women (48% vs. 36%;p<.05). Fewer than one in four women identified sudden severe headache (23%), unexplained dizziness (20%), or sudden dimness/loss of vision (18%) as warning signs, and one in five (20%) did not know one stroke warning sign. The majority of women said that they would call 9-1-1 first if they thought they were experiencing signs of a stroke (84%), and this did not vary among black (86%), Hispanic (79%), or white/other (85%) women.

Conclusions

Knowledge of stroke warning signs was low among a nationally representative sample of women, especially among Hispanics. In contrast, knowledge to call 9-1-1 when experiencing signs of stroke was high.

Keywords: Stroke, Women, Disparities

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is the third leading cause of death among women in the United States (U.S.) (1). The aftermath of stroke is significant among female survivors. It is estimated that 31% of will need help caring for themselves, 16% will require institutional care, and 7% will have an impaired ability to work (2). Each year approximately 55,000 more women than men have a stroke; this has been attributed to the average life expectancy being greater for women versus men coupled with the highest stroke rates occurring in the oldest age groups (1). Recent nationally representative data also show a rise in stroke prevalence among middle-age women not seen among their male counterparts, underscoring the need for better understanding of stroke in women of all ages (3).

Women from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds experience a disproportionate stroke burden; black women have an incident stroke risk almost twice as high as white women (1). Stroke risk factor prevalence may be higher among Hispanic women (1,4,5). Historically, knowledge of stroke warning signs has been lower among racial/ethnic minorities compared to whites (6-8). The ability to recognize stroke warning signs at their onset is associated with more rapid access to emergency care and decreased stroke-related morbidity and mortality (9-11). Addressing gaps in women's knowledge related to stroke warning signs may be a key initial step toward improving outcomes and reducing disparities. Current metrics are required to assess levels of knowledge and educational needs of women in the U.S.

In 2012 the American Heart Association (AHA) commissioned a national survey to determine women's cardiovascular disease (CVD) awareness, including knowledge related to stroke warning signs (12). The purpose of this study was to evaluate contemporary knowledge of stroke warning signs and intent to call 9-1-1 first if warning signs occur, overall and by race/ethnic group, among this nationally representative sample of women.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of women in the U.S. aged >25 years. The study sample comprised the 1,205 telephone respondents who participated in the 2012 AHA National Women's Tracking Survey (methods previously published (12)). Briefly, potential respondents were contacted via telephone using random-digit dial technology. Surveys were administered (August 28-October 5, 2012) by, and data were analyzed by, representatives from Harris Interactive, New York, NY. The survey was in English and took approximately 10 minutes. Participants were asked standardized categorical questions to collect demographic data; they self-categorized their race/ethnic group as White, Black (Black/African American), Hispanic, or Other (Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaskan Native, mixed race/ethnicity, other race). Survey questions related to stroke warning signs, and what to do first if stroke warning signs occur, were unaided (open-ended, survey published online (12)); responses were collected, then categorized. Data were weighted using the U.S. Census Bureau March 2011 Current Population Survey to reflect the composition of the U.S. population of English speaking women aged ≥25 years based on age, education, income, race/ethnicity, and region. Differences of proportion by race/ethnic group were analyzed using chi-square statistics. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

The demographic and medical history characteristics of respondents have been published previously (12). Hispanic respondents were more likely than whites to be in the youngest age group (25-34 years; 22% vs. 11%). Blacks were more likely than whites to have a history of diabetes mellitus (19% vs. 12%). Both black and Hispanic respondents were more likely than whites to have a household annual income less than $35,000 (39% and 34% vs. 22%).

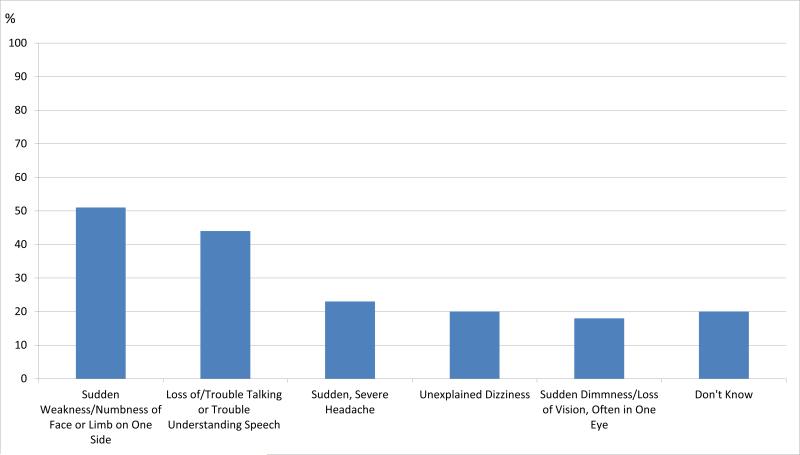

Figure 1 illustrates women's knowledge of stroke warning signs. Approximately half of women surveyed (51%) identified sudden weakness/numbness of face or limb on one side as a stroke warning sign, and this did not vary by race/ethnic group (Table 1). Loss of/trouble talking or trouble understanding speech was identified by 44% of respondents, and more frequently among white versus Hispanic women. Fewer than one in four women identified sudden severe headache (23%), unexplained dizziness (20%), or sudden dimness, loss of vision, often in one eye (18%) as warning signs. One in five women did not know one stroke warning sign; this did not vary by race/ethnic group.

Figure 1.

2012 National Women's Knowledge of Stroke Warning Signs

Table 1.

National Women's Knowledge of Stroke Warning Signs by Race/Ethnic Group

| Response (Unaided) | White | Black | Hispanic | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [a] | [b] | [c] | [d] | |

| What warning signs would you associate with having a stroke or “brain attack?” | ||||

| Sudden weakness/numbness of face or limb on one side | 52 | 55 | 46 | 47 |

| Loss of/trouble talking or trouble understanding speech | 48cd | 44d | 36 | 27 |

| Sudden severe headache | 24 | 24 | 18 | 20 |

| Unexplained dizziness | 19 | 21 | 20 | 26 |

| Sudden dimness, loss of vision, often in one eye | 19 | 14 | 18 | 15 |

| Don't know | 18 | 19 | 25 | 24 |

Note: All values are weighted percentages

Superscript letter denotes significant differences in columns for race/ethnic groups at p<0.05.

Women were asked “If you thought you were experiencing signs of a stroke or “brain attack,” what is the first thing you would do?” The majority of women (84%) said that they would call 9-1-1 first and this did not differ among white, black, or Hispanic women (Table 2).

Table 2.

Women's First Response to Stroke Warning Signs Overall and by Race/Ethnic Group

| Response (Unaided) | Overall | White | Black | Hispanic | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [a] | [b] | [c] | [d] | ||

| If you thought you were experiencing signs of a stroke or “brain attack,” what is the first thing you would do? | |||||

| Call 9-1-1 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 79 | 85 |

| Call your spouse or family | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 2 |

| Go to the hospital | 4 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 2 |

| Call your doctor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Don't know | 3 | 2 | 5a | 5 | 7a |

Note: All values are weighted percentages

Superscript letter denotes significant differences in columns for race/ethnic groups at p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative sample of women, knowledge of stroke warning signs was low, especially among Hispanics. In contrast, knowledge to call 9-1-1 was high, and did not differ by race/ethnic group. These data suggest that women are aware of what to do when experiencing signs of stroke, but at least half would not be able to recognize the signs should they occur.

While we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed race/ethnic differences were due to chance or due to differences in respondent characteristics, the results from this study are consistent with historic data that have documented low knowledge of stroke warning signs among women in the U.S., especially in Hispanic versus white women (6, 8). Interpretation of race/ethnic differences in knowledge may be limited by the inclusion of English-speaking participants only.

The data highlight a knowledge gap specifically related to stroke warning signs. Effective clinical counseling strategies and public awareness campaigns, such as the AHA/American Stroke Association Spot a Stroke F.A.S.T. [Face Drooping, Arm Weakness, Speech Difficulty, Time to call 911] campaign, are needed to reach diverse populations of women.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (K24HL076346; PI Dr. Mosca).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Contributor Information

Heidi Mochari-Greenberger, Columbia University Medical Center 51 Audubon Avenue New York, NY 10032.

Amytis Towfighi, Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center 7601 East Imperial Highway Downey, California 90242.

Lori Mosca, Columbia University Medical Center 51 Audubon Avenue New York, NY 10032 Telephone: 212-305-4866 FAX: 212-342-5238.

REFERENCES

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacco RL. Godfrey Jodi R., editor. Toward optimal health: A renewed look at stroke in women. J Women's Health. 2009;18:13–18. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Towfighi A, Zheng L, Ovbiagele B. Weight of the obesity epidemic: rising stroke rates among middle-aged women in the United States. Stroke. 2010;41:1371–1375. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.577510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Disparities in deaths from stroke among persons aged < 75 years: United States 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:477–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz-Flores S, Rabinstein A, Biller J, Elkind MSV, Griffith P, Gorelick PB, et al. Race-ethnic disparities in stroke care: the American experience: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:2091–2116. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182213e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferris A, Robertson RM, Fabunmi R, Mosca L. American Heart Association and American Stroke Association national survey of stroke risk awareness among women. Circulation. 2005;111:1321–1326. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157745.46344.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Awareness of stroke warning symptoms—13 States and the District of Columbia, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:481–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Payne GH, Fang J, Fogle CC, Oser CS, Wigand DA, Theisen V, et al. Stroke awareness: surveillance, educational campaigns, and public health practice. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16:345–358. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181c8cb79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lansberg MG, O'Donnell MJ, Khatri P, Lang ES, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Schwartz NE, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e601S–e636S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandratheva A, Lasserson DS, Geraghty OC, Rothwell PM. Population-based study of behavior immediately after transient ischemic attack and minor stroke in 1000 consecutive patients: lessons for public education. Stroke. 2010;41:1108–1114. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.576611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider AT, Pancioli AM, Khoury JC, Rademacher E, Tuchfarber A, Miller R, et al. Trends in community knowledge of the warning signs and risk factors for stroke. JAMA. 2003;289:343–346. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosca L, Hammond G, Mochari-Greenberger H, Rao S, Albert MA. Fifteen-year trends in awareness of heart disease in women: results of a 2012 American Heart Association national survey. Circulation. 2013;127:1254–1263. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318287cf2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]