Mutations in GBA1, which encodes the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase, underlie Gaucher disease and are a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease. Siebert et al. review emerging evidence that connects glucocerebrosidase with α-synuclein. Therapeutic strategies for Gaucher disease may inform the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies.

Keywords: glucocerebrosidase, α-synuclein, Gaucher disease, Parkinson’s disease, lysosome

Abstract

The lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase, encoded by the glucocerebrosidase gene, is involved in the breakdown of glucocerebroside into glucose and ceramide. Lysosomal build-up of the substrate glucocerebroside occurs in cells of the reticulo-endothelial system in patients with Gaucher disease, a rare lysosomal storage disorder caused by the recessively inherited deficiency of glucocerebrosidase. Gaucher disease has a broad clinical phenotypic spectrum, divided into non-neuronopathic and neuronopathic forms. Like many monogenic diseases, the correlation between clinical manifestations and molecular genotype is not straightforward. There is now a well-established clinical association between mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene and the development of more prevalent multifactorial disorders including Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies. In this review we discuss recent studies advancing our understanding of the cellular relationship between glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein, the potential impact of established and emerging therapeutics for Gaucher disease for the treatment of the synucleinopathies, and the role of lysosomal pathways in the pathogenesis of these neurodegenerative disorders.

Introduction

The enzyme glucocerebrosidase (EC 3.2.1.45) breaks down the glycolipid glucocerebroside into glucose and ceramide inside lysosomes (Beutler and Grabowski, 2001). Glucocerebrosidase is encoded by the glucocerebrosidase (GBA1) gene, which is located on chromosome 1q21 spanning 7.6 kb and includes 11 exons. A highly homologous pseudogene is located 16 kb downstream and presents challenges for the molecular analysis of GBA1 (Horowitz et al., 1989; Winfield et al., 1997). Mutations in GBA1 cause glucocerebrosidase deficiency and the subsequent accumulation of the undegraded substrate glucocerebroside inside the lysosomes of cells composing the reticulo-endothelial system. This accumulation of glucocerebroside substrate results in Gaucher disease (OMIM #606463), a rare pan-ethnic autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder (Beutler and Grabowski, 2001). The main cell biological function of macrophages is phagocytosis-mediated breakdown of senescent cells such as erythrocytes, which have glucocerebroside-rich membranes. Gaucher disease macrophages that have accumulated glucocerebroside appear engorged and are often referred to as ‘Gaucher cells’. Gaucher cells primarily populate the spleen, liver and bone marrow, resulting in inflammation and organomegaly (Lachmann et al., 2004; Sidransky, 2012). Although Gaucher disease is rare, it is the most common lysosomal storage disorder with an estimated frequency of 1:40 000–60 000 live births in the general population and an exceptionally high prevalence in the Ashkenazi Jewish population (1:850 individuals) (Beutler et al., 1993; Beutler and Grabowski, 2001). To date, over 300 GBA1 pathogenic mutations and polymorphisms have been reported (Hruska et al., 2008), but correlations between the clinical phenotype and molecular genotype remain limited (Goker-Alpan et al., 2005; Hruska et al., 2008; Sidransky, 2012). Indeed, studies have shown that patients with identical genotypes can have vastly different clinical manifestations and severity, even between siblings and twins (Lachmann et al., 2004; Sidransky, 2004; Biegstraaten et al., 2011), whereas patients with different molecular genotypes can share similar clinical phenotypes (Hruska et al., 2008). Furthermore, there is not a strong correlation between the amount of accumulated substrate and/or residual glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity and clinical manifestations in patients (Sidransky, 2012). This suggests that Gaucher disease is not a ‘simple’ monogenic disorder, and that additional factors such as epigenetics and/or genetic modifiers may contribute to disease development and phenotype (Koprivica et al., 2000; Sidransky, 2004; Goker-Alpan et al., 2005).

Gaucher disease is classified into three different types, based on the absence (type 1) or the presence and severity of neurological manifestations (types 2 and 3). Non-neuronopathic type 1 Gaucher disease (OMIM #230800) is the most common form and accounts for >90% of cases in the USA and Europe (Beutler and Grabowski, 2001; Cherin et al., 2010). Clinical manifestations include enlarged liver and spleen, bone complications, anaemia and thrombocytopaenia (Pastores et al., 2000; Beutler and Grabowski, 2001). The extent of symptoms is highly variable and many affected individuals will never reach medical attention. One common GBA1 mutation, N370S, seems to be exclusively associated with type 1 Gaucher disease, although other mutations can also be seen in patients with Gaucher disease type 1. It has been reported that Gaucher disease type 1 is associated with an increased risk of certain malignancies such as multiple myeloma, hepatocellular carcinoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, malignant melanoma and pancreatic cancer (Zimran et al., 2005; de Fost et al., 2006; Ayto and Hughes, 2013; Mistry et al., 2013; Weinreb and Lee, 2013). Acute neuronopathic or type 2 Gaucher disease (OMIM #230900) is the rarest and most severe form of the disease (Beutler and Grabowski, 2001) with rapidly progressing neurological deterioration, resulting in death within the first years of life (Beutler and Grabowski, 2001; Sidransky, 2004). The onset and progression of neurological symptoms in chronic neuronopathic Gaucher disease type 3 (OMIM #2301000) is later and slower compared with Gaucher disease type 2 (Beutler and Grabowski, 2001; Sidransky, 2012). Clinical manifestations can include myoclonic epilepsy and ataxia, developmental delay, intellectual deterioration, and learning disabilities, in addition to skeletal and visceral involvement (Sidransky, 2004, 2012; Gupta et al., 2011; Sidransky and Lopez, 2012). Patients with type 3 Gaucher disease develop a specific oculomotor abnormality consisting of the slowing or looping of the horizontal saccades. It is often difficult to classify patients as a specific type of Gaucher disease because of the broad range of manifestations encountered (Sidransky, 2004). Thus it may be more appropriate to view Gaucher disease-associated phenotypes as a continuum because of the broad range of associated manifestations observed (Sidransky, 2004, 2012).

The classification of type 1 as the non-neuronopathic form of Gaucher disease has recently been questioned because of its association with synucleinopathies including Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies (Sidransky et al., 2009; Nalls et al., 2013). The synucleinopathies include different disorders with parkinsonian features characterized pathologically by the presence of Lewy body inclusions, composed of aggregates of the small unstructured protein α-synuclein (Puschmann et al., 2012). The association between GBA1 mutations and parkinsonism was first established based on longitudinal clinical studies, in which it was observed that some patients with Gaucher disease developed parkinsonism (Tayebi et al., 2001, 2003; Bembi et al., 2003). It was then recognized that Parkinson’s disease was more frequent in first-degree relatives of patients with Gaucher disease. Studies in specific cohorts of patients with Parkinson’s disease and associated Lewy body disorders indicated these patients had an increased frequency of GBA1 mutations compared with control groups (Goker-Alpan et al., 2004; Lwin et al., 2004; Eblan et al., 2006; Ziegler et al., 2007). In 2009, a large international collaborative group including 16 participating centres performed molecular analysis of GBA1 on >5000 DNA samples from patients with Parkinson’s disease and an equal number of controls including subjects with different ethnicities. The resulting odds ratio (OR) of 5.43 clearly demonstrated a strong association between GBA1 mutations and Parkinson’s disease. Moreover, subjects with GBA1 mutations had an earlier onset of Parkinson’s disease symptoms and more frequent cognitive changes (Sidransky et al., 2009). Interestingly, genome-wide association studies initially failed to identify GBA1 as a genetic risk factor for parkinsonism, but more recent genome-wide association studies have identified specific GBA1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (Pankratz et al., 2009; Satake et al., 2009; Simon-Sanchez et al., 2009). Since then, this association persisted and has been reproduced in multiple cohorts around the world (Dos Santos et al., 2010; Mao et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2011; Lesage et al., 2011a, b; Moraitou et al., 2011; Noreau et al., 2011; Anheim et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2012; Emelyanov et al., 2012; Tsuang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Becker et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2013). It is now widely accepted that the frequency of GBA1 mutations in subjects with Parkinson’s disease from varied ethnicities is greater than any other genetic risk factor for Parkinson’s disease, once common risk variants of low effect are excluded. Recently, this association was expanded to dementia with Lewy bodies, with the identification of GBA1 mutations in 3.5% to 23% of subjects in genotyping studies of various independent cohorts (Goker-Alpan et al., 2006; Mata et al., 2008). Another large international multicentre study of GBA1 mutations in dementia with Lewy bodies was undertaken. Eleven centres contributed a total of 721 cases with dementia with Lewy bodies and 151 cases of Parkinson’s disease with dementia, which were compared with 1962 control subjects, matched for age, sex and ethnicity. A significant association between GBA1 mutations and dementia with Lewy bodies, as well as Parkinson’s disease with dementia, was established, with odds ratios of 8.28 and 6.48, respectively. Similar to Parkinson’s disease, the age of diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies in patients with GBA1 mutations was younger compared to dementia with Lewy bodies without GBA1 mutations (Nalls et al., 2013). These GBA1 studies establish its involvement in several synucleinopathies, although GBA1 mutations are not seen with multiple system atrophy, an α-synucleinopathy with α-synuclein inclusions mainly in glial oligodendrocytes (Spillantini et al., 1998; Beyer and Ariza, 2007; Segarane et al., 2009; Jamrozik et al., 2010; Srulijes et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2013a).

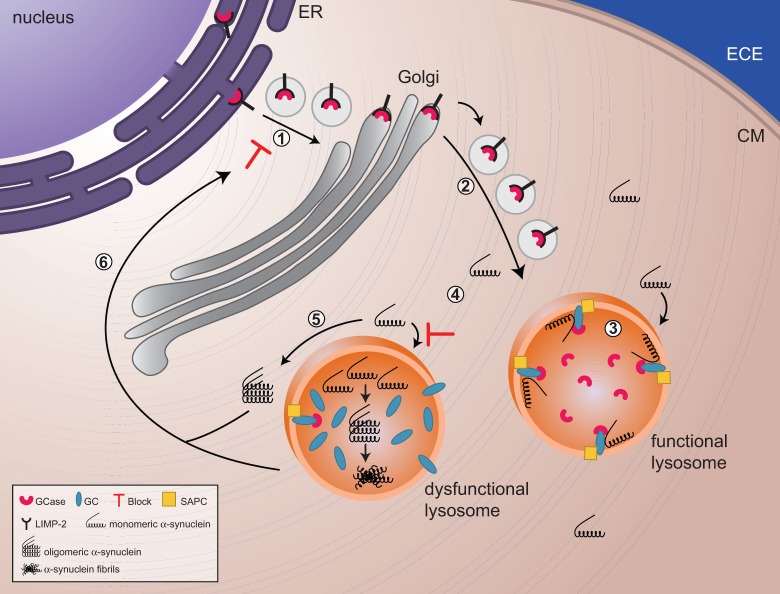

The major pathological characteristics of Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies are the presence of insoluble oligomeric and fibrillar α-synuclein-positive inclusions known as Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in neurons in the substantia nigra, cerebral cortex, and hippocampus and the selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain (Puschmann et al., 2012). Aggregation of α-synuclein seems to correlate with the onset and progression of synucleinopathies, and its direct role in disease manifestation is clear from the association of familial Parkinson’s disease with mutations, duplications, and triplications in the α-synuclein gene (Fearnley and Lees, 1991; Puschmann, 2013). Monomeric α-synuclein is a small 14 kDa protein that is highly expressed in the brain, where it is likely involved in the regulation of synaptic vesicle clustering and the release of neurotransmitters through interaction with lipids and members of the soluble NSF Attachment Protein Receptor complex assembly machinery (Abeliovich et al., 2000; Cabin et al., 2002; Burre et al., 2010; Garcia-Reitbock et al., 2010; Ito et al., 2012; Diao et al., 2013), but its exact biological function remains elusive. Monomers, fibrils, and aggregates of α-synuclein can undergo transmission between cells, a process that may be facilitated by small 50–100 nm vesicles called exosomes that are released into the extracellular environment upon exocytosis of multivesicular bodies (Desplats et al., 2009; Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011; Hansen et al., 2011; Russo et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2013). The neuropathology in Parkinson’s disease with GBA1 mutations is similar to other synucleinopathies without GBA1 mutations; α-synuclein-positive Lewy bodies are found in the brains of patients with Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies with GBA1 mutations (Neumann et al., 2009; Goker-Alpan et al., 2010). The exact molecular mechanisms involved in the interaction between glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein remain unresolved, but experimental data indicate that there is a reciprocal relationship between glucocerebrosidase activity and α-synuclein. When the delicate balance of α-synuclein homeostasis is disturbed, possibly by impairment of essential protein turnover pathways such as the unfolded protein response, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation and autophagy, cell stress or environmental factors, an increase in α-synuclein levels will inhibit translocation of glucocerebrosidase from the endoplasmic reticulum to the lysosome. In turn, less lysosomal glucocerebrosidase leads to a gradual increase in glucocerebroside substrate and subsequent oligomerization and accumulation of α-synuclein in the lysosomes. Eventually, the lysosomes become dysfunctional, and autophagy-mediated α-synuclein turnover is impaired, leading to α-synuclein aggregates in the cytoplasm, which, in turn, inhibit trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum to the lysosome. This positive feedback loop of dysfunctional glucocerebrosidase trafficking, impaired lysosomal function, and progressive α-synuclein accumulation will eventually cause neurodegeneration (Mazzulli et al., 2011) (Fig. 1). A recent in vivo observation of reduced enzyme activity and protein levels of glucocerebrosidase in the substantia nigra of brains from patients with Parkinson’s disease without GBA1 mutations supports this reciprocal relationship, and expands our understanding of the key function of glucocerebrosidase in the pathology of synuncleinopathies (Gegg et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

The reciprocal relationship between glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein. (1 and 2) Glucocerebrosidase (GCase) is sorted via the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi to the lysosomes. (3) In lysosomes, glucocerebrosidase interacts with its substrate glucocerebroside (GC) as well as monomers of α-synuclein, facilitating the breakdown of both at acidic pH. (4) Decreased levels of glucocerebrosidase will result in a slowdown of α-synuclein degradation and a gradual build up of glucocerebroside substrate, with the eventual formation of α-synuclein oligomers and fibrils. (4) Impaired lysosomes, as a result of build up of substrate and/or α-synuclein oligomers and fibrils, will show impaired chaperone-mediated autophagy and autophagosome fusion, which implies that α-synuclein cannot undergo autophagy-mediated degradation, resulting in an increased accumulation of α-synuclein in the cytoplasm. (5) These soluble monomers will eventually assemble in oligomers and will block trafficking of glucocerebrosidase from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi. ECE = extracellular environment; CM = Cell Membrane; SAPC = saposin C.

As most subjects with Gaucher disease never develop Parkinson’s disease, GBA1 mutations and a reduction in glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity alone cannot be the cause of Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies. As Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies are disorders associated with ageing, it is likely that cellular processes impacted during the ageing process are linked with Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Indeed, it has been reported that ageing is associated with the diminished function of tightly regulated protein and organelle homeostasis pathways such as autophagy-lysosomal function (Cook et al., 2012), endoplasmic reticulum stress (Lu et al., 2014), and mitochondrial stress (Lu et al., 2014; Venkataraman et al., 2013). The critical balance between α-synuclein proteostasis and optimal function of the proteasome and/or autophagy-lysosome-mediated breakdown may become compromised during ageing. Mutant, absent, or downregulated glucocerebrosidase could contribute to this scenario by further compromising these cellular pathways. In this review, we will discuss new insights into the reciprocal relationship between glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein, the implications of deficient α-synuclein breakdown in key quality control and turnover pathways, modifiers of GBA1 that might contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease, Gaucher disease therapeutics and their implications for the treatment of synucleinopathies, and the expansion of Parkinson’s disease risk factors to enzymes involved in other lysosomal storage disorders.

Cellular role of glucocerebrosidase in the neuropathology of synucleinophathies

The reciprocal relationship between glucocerebrosidase, α-synuclein and lysosomal impairment

The involvement of glucocerebrosidase in the pathogenesis of the synucleinopathies is still not completely understood. Initially, arguments were made for either a gain-of-function or loss-of-function model. The gain-of-function model implies that the aberrant enzyme is directly involved in α-synuclein aggregation through a biochemical interaction with α-synuclein or interference with α-synuclein homeostasis pathways such as the unfolded protein response and autophagy. Evidence for gain-of-function was provided in a comprehensive study by Cullen et al. (2011) where it was shown that transient over-expression of different GBA1 mutant constructs in MES23.5 and PC12 cells expressing wild-type α-synuclein promoted accumulation of α-synuclein in a time- and dose-dependent manner that was independent of glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity status. Furthermore, an in vivo mouse model with mutant Gba (GbaD409V/D409V), demonstrated age-dependent accumulation of α-synuclein. However, the contribution of reduced enzyme activity, which was 20% of control, to the α-synuclein accumulation process could not be ruled out in this model (Cullen et al., 2011). In the loss-of-function model, the progressive build up of glucocerebroside substrate in lysosomes may directly promote α-synuclein aggregation, or have an indirect effect because of altered lysosomal pH and/or diminished function of lysosomal and autophagy-mediated breakdown pathways. Studies on cell and mouse models, as well as patient samples, have provided evidence for both models (Westbroek et al., 2011). In the context of these two models, the E326K mutation deserves special mention as it has long been the subject of controversy. Independent studies have established that E326K is associated with Parkinson’s disease (Horowitz et al., 2011; Pankratz et al., 2012; Duran et al., 2013), but this mutation is believed to be non-pathogenic (Park et al., 2002; Liou and Grabowski, 2012) with only a significant effect on enzyme activity when found in combination with other pathogenic GBA1 mutations (Montfort et al., 2004; Horowitz et al., 2011; Liou and Grabowski, 2012; Malini et al., 2013). This suggests that in the case of E326K, reduced glucocerebrosidase activity might not be the principal factor contributing to the development of Parkinson’s disease.

Several experimental observations have expanded on the model of a reciprocal relationship as the basis for a mechanistic link between glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein. The effect of manipulation of glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity or expression levels on α-synuclein accumulation was demonstrated in mice and neuroblastoma cells treated with the glucocerebrosidase inhibitor conduritol-B-epoxide (CBE), which showed significant accumulation of α-synuclein protein, but no change in messenger RNA levels (Manning-Bog et al., 2009; Cleeter et al., 2013). However, α-synuclein accumulation or compromised lysosomal function could not be observed in long-term CBE-treated SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells or primary rat cortical neurons, indicating that deficient glucocerebrosidase activity alone does not alter α-synuclein in these cell models (Dermentzaki et al., 2013). Interestingly, primary mouse neurons silenced for GBA1 expression showed enhanced α-synuclein accumulation that was not observed in the neuroblastoma cell line (Mazzulli et al., 2011; Cleeter et al., 2013). Cullen and co-workers showed that over-expression of wild-type GBA1 in HEK293 cells expressing A53T α-synuclein and PC12 cells expressing wild-type α-synuclein induced down-regulation of α-synuclein levels. However, this observation appeared to be cell-model specific, since this was not observed with transiently transfected wild-type GBA1 in MES23.5 cells expressing wild-type α-synuclein (Cullen et al., 2011). In vivo studies by Sardi et al. (2011, 2013) showed that adenovirus-mediated expression of wild-type glucocerebrosidase in the CNS of mice with features of neuronopathic Gaucher disease corrected substrate accumulation, cognitive impairment, and α-synuclein aggregation in the brain, and in transgenic mice over-expressing A53T α-synuclein without GBA1 mutations, adenovirus-mediated expression of wild-type glucocerebrosidase reduced α-synuclein levels (Sardi et al., 2011, 2013). Additionally, increasing α-synuclein levels downregulated glucocerebrosidase activity and protein levels in several in vitro and in vivo models of Parkinson’s disease. Biophysical studies indicate that at acidic pH, there is a direct interaction between wild-type α-synuclein and glucocerebrosidase that is speculated to be beneficial for α-synuclein turnover in the lysosome. Additional biophysical evaluations indicate that α-synuclein inhibits glucocerebrosidase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Yap et al., 2011, 2013). In cells, increased levels of α-synuclein caused a reduction in wild-type glucocerebrosidase activity, and to a lesser extent, glucocerebrosidase protein levels (Mazzulli et al., 2011; Gegg et al., 2012). Studies performed in a limited number of post-mortem brain samples from subjects with sporadic Parkinson’s disease without GBA1 mutations, show a significant decrease in glucocerebrosidase activity and protein levels in the substantia nigra and cerebellum (Gegg et al., 2012). The pivotal experimental evidence regarding the reciprocal relationship between glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein came from an elaborate and comprehensive study by Mazzulli and co-workers (2011), where it was shown that partial loss of glucocerebrosidase activity in primary mouse neurons, or human neuronal cultures derived from induced pluripotent stem cells, interfered with protein degradation in the lysosome, promoted accumulation of α-synuclein, and enhanced α-synuclein-mediated neurotoxicity. In vitro, glucocerebroside substrate was shown to promote stabilization of α-synuclein oligomers and aggregation. Over-expression of α-synuclein inhibited endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi trafficking of glucocerebrosidase, presumably by inhibiting formation of soluble NSF attachment protein receptor complexes (Cooper et al., 2006; Thayanidhi et al., 2010), which resulted in the downregulation of lysosome-resident glucocerebrosidase. Analyses of brain samples indicated that soluble α-synuclein oligomers were increased in both subjects with neuronopathic Gaucher disease and subjects with Parkinson’s disease with GBA1 mutations; however, brain samples from subjects with Parkinson’s disease without GBA1 mutations were not included in this study (Mazzulli et al., 2011). This is in contrast with a study where α-synuclein solubility was measured in brain samples from patients with Gaucher disease as well as patients with synucleinopathies with and without GBA1 mutations, demonstrating the presence of α-synuclein aggregates exclusively in the brains from subjects known to have synucleinopathies (Choi et al., 2011). It should be noted that both studies used different methods for brain lysate preparation and analysis. An in vivo study on induced pluripotent stem cells-derived cortical neurons from a patient with the A53T mutation in α-synuclein showed an increase in the ratio of endoplasmic reticulum-resident to post-endoplasmic reticulum glucocerebrosidase compared to isogenic gene-edited wild-type cortical neurons. This was also observed in brain samples from a subject with A53T α-synuclein and in cortex samples from patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. These observations suggest that glucocerebrosidase trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum to the lysosomes was significantly reduced in A53T cells as well as Parkinson’s disease brain samples (Chung et al., 2013). Thus, a majority of the studies described provide evidence supporting a reciprocal relationship model between glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein (Fig. 1). The central player in this reciprocal relationship model is the lysosome, which is the main organelle responsible for the degradation of proteins, lipids and organelles such as defective mitochondria (Dehay et al., 2013). Lysosome-mediated degradation of α-synuclein occurs through both macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy. Proteins destined for chaperone-mediated autophagy, such as α-synuclein, form a complex with heat shock cognate 70, which is targeted to the lysosomal membrane where it interacts with lysosomal associated membrane protein 2A, and undergoes translocation to the lysosome, followed by degradation (Arias and Cuervo, 2011); impaired chaperone-mediated autophagy has been reported in Parkinson’s disease brain samples (Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2010). In macroautophagy, double-membraned autophagosomes carry engulfed proteins, lipids and organelles destined for breakdown to lysosomes. This occurs via the formation of the autophagolysosome, resulting from the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes (Yang and Klionsky, 2010). Accumulating evidence indicates that lysosomal impairment contributes to the neuropathology of Parkinson’s disease (Tofaris, 2012) and in turn, α-synuclein aggregation can impair autophagy and lysosomal function (Winslow et al., 2010). A well-illustrated example of the implications of lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease is the PARK9 gene, which encodes the ATP13A2 protein, a lysosomal P-type ATPase. Mutations in PARK9 have been shown to cause severe lysosomal impairment and accumulation of α-synuclein, and are associated with Kufor-Rakeb syndrome, a rare genetic form of parkinsonism (Schultheis et al., 2013). Autophagy and lysosomal dysfunction have been reported in models and in tissue samples from subjects with GBA1-associated Parkinson’s disease. In primary cortical wild-type mouse neurons infected with lentiviral α-synuclein and GBA1 short hairpin RNA, resulting in 50% reduction in glucocerebrosidase protein levels, lysosomal protein turnover capacity was impaired, and enlarged lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1-positive structures accumulated. These results were validated in dopaminergic neurons generated from induced pluripotent stem cells derived from Gaucher disease fibroblasts (Mazzulli et al., 2011). Inhibiting glucocerebrosidase with CBE or partial GBA1 silencing in SHSY-5Y neuroblastoma cells did not change the lysosomal content or the levels of LC3-II, which corresponds to the number of accumulated autophagosomes (Cleeter et al., 2013). Dermentzaki et al. (2013) saw a slight but significant increase in LC3-II levels in SHSY-5Y cells treated with CBE for 100 days. Similar observations were made in brain samples from subjects with both sporadic Parkinson’s disease and GBA1-associated Parkinson’s disease (Gegg et al., 2012). In a Gba-/- mouse model representative of neuronopathic type 2 Gaucher disease, impairment of autophagy, mitophagy and also the proteasome-mediated degradation pathway were observed in midbrain neurons and astrocytes. This resulted in the accumulation of fragmented mitochondria and α-synuclein. Although this model does not represent Parkinson’s disease, it should be noted that α-synuclein pathology was present. This finding clearly illustrates that dysfunction in the reciprocal balance between glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein can lead to neurodegeneration (Osellame et al., 2013).

The unfolded protein response

Chaperones, lectins and foldases all assist with the protein folding process, but it is believed that about one-third of all newly synthesized proteins are still damaged or misfolded (Schubert et al., 2000). To maintain balanced cell proteostasis, aberrant proteins are turned over via endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) through ubiquitination by ubiquitin ligases and subsequent 26S proteasome-mediated degradation (Kaufman, 2002; Goldberg, 2003). In the case of persistent accumulation, the unfolded protein response is activated through three endoplasmic reticulum transmembrane sensor proteins: activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), type I transmembrane protein kinase and endoribonuclease (IRE1), and RNA-activated protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), which are negatively regulated by binding of BiP, a member of the heat shock protein 70 protein family. In the presence of excessive unfolded proteins, BiP is recruited to the endoplasmic reticulum lumen, where it activates IRE1, ATF6 and PERK by its dissociation. The three sensors initiate various signalling pathways, which include restoration of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis by the regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum folding load recovery process through induction of ERAD and protein folding chaperones, attenuation of protein translation, and, if the restoration of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis fails, cell death (Germain, 2008; Chakrabarti et al., 2011; Brodsky, 2012; Sano and Reed, 2013).

Several recent studies indicate that both ERAD and the unfolded protein response play crucial roles in the cellular pathology of Parkinson’s disease. Experimental cell and mouse models and studies in post-mortem Parkinson’s disease brain samples indicate that the first stages of α-synuclein accumulation and aggregation lead to induction of the unfolded protein response, with upregulation of unfolded protein response markers in dopaminergic neurons and eventual neurodegeneration (Bellucci et al., 2011; Colla et al., 2012a, b; Gorbatyuk et al., 2012; Hoozemans et al., 2012).

The role of glucocerebrosidase in endoplasmic reticulum stress and neurodegeneration has only recently begun to emerge. Under normal conditions, newly synthesized glucocerebrosidase is correctly folded in the endoplasmic reticulum and is then translocated to the lysosomes. Aberrant glucocerebrosidase fails to fold correctly, is arrested in the endoplasmic reticulum and is redirected to undergo polyubiquitination, followed by degradation. Studies on fibroblasts derived from patients with Gaucher disease have established that glucocerebrosidase mutants undergo polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation via ERAD (Ron and Horowitz, 2005; Bendikov-Bar et al., 2011; Bendikov-Bar and Horowitz, 2012). Heat shock protein 90β was identified as the key chaperone for the redirection of aberrant glucocerebrosidase for breakdown via ERAD (Lu et al., 2010, 2011; Yang et al., 2013). Several E3-ubiquitin ligases such as ITCH, c-Cbl, and parkin recognize mutant glucocerebrosidase as their substrate for polyubiquitination (Lu et al., 2010; Ron et al., 2010; Maor et al., 2013). As a result of ERAD, lysosomal levels of glucocerebrosidase are significantly decreased, resulting in the accumulation of glucocerebroside substrate. It was suggested that the severity of Gaucher disease symptoms might correlate with the degree of endoplasmic reticulum retention of mutant glucocerebrosidase (Ron and Horowitz, 2005; Bendikov-Bar et al., 2011; Bendikov-Bar and Horowitz, 2012). Persistent accumulation of aberrant proteins can activate the unfolded protein response, which has been reported in human fibroblasts derived from patients with Gaucher disease and carriers of GBA1 mutations (Brady et al., 1974; Mu et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2011; Maor et al., 2013). Fly models corresponding to GBA1 carriers and transgenic flies expressing human N370S or L444P glucocerebrosidase mutants both showed unfolded protein response activation and both the development of a locomotion impairment reminiscent of parkinsonian features and an early death (Maor et al., 2013). Activation of the unfolded protein response in Gaucher disease and carriers of GBA1 mutations support a previous report demonstrating that the interaction of mutant glucocerebrosidase with the E3-ubiquitin ligase parkin leads to K48-mediated polyubiquitination of glucocerebrosidase, before breakdown in the proteasome. It was proposed that this interaction might impair interactions with other, potentially neurotoxic, parkin substrates, and that interference with their breakdown would result in endoplasmic reticulum stress, followed by unfolded protein response activation and the subsequent elevation of ERAD. This, in turn, would lead to further accumulation of neurotoxic substrates, resulting in cell death (Ron et al., 2010). However, a study performed on parkin-deficient fibroblasts provided evidence that parkin is not a crucial E3-ubiquitin ligase for glucocerebrosidase (McNeill et al., 2013). Not every Gaucher disease model demonstrates unfolded protein response activation. CBE-treated cultured primary mouse neurons and astrocytes show no changes in expression of common unfolded protein response makers (Farfel-Becker et al., 2009). The same was observed for select brain regions of the two mouse models representative of neuronopathic Gaucher disease; the Gba-/- knock-out (Tybulewicz et al., 1992) and the conditional Gba-/- knock-out, which is restricted to neural and glial progenitor cells (Enquist et al., 2007) as well as the GbaL444P/L444Pmouse, a model with partial enzyme deficiency and no neurological involvement (Mizukami et al., 2002; Farfel-Becker et al., 2009). Cullen et al. (2011) failed to detect activation of the unfolded protein response in MES23.5 cells expressing wild-type α-synuclein that were transiently transfected with mutant GBA1 constructs. Finally, an increase in unfolded protein response markers was seen in post-mortem brain samples from subjects with sporadic Parkinson’s disease with and without GBA1 mutations (Gegg et al., 2012). ERAD of aberrant glucocerebrosidase protein, or endoplasmic reticulum retention of wild-type glucocerebrosidase as a result of α-synuclein mediated blocking of trafficking, might contribute to the increased unfolded protein response. This remains speculative because increased unfolded protein response could also be induced by other pathways associated with Parkinson’s disease, such as a malfunction in Ca2+ release, metabolic stress, inflammation, and mitochondrial oxidative stress (Doyle et al., 2011; Wang and Kaufman, 2012). The exact relationship between glucocerebrosidase, α-synuclein accumulation, and the role of the unfolded protein response remains to be fully determined.

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Growing evidence indicates that mitochondrial turnover, dysfunction, and oxidative stress play key roles in the development and progression of Parkinson’s disease. Indeed, mutations in three genes (PINK1, PARK2 and PARK7) involved in these pathways cause familial Parkinson’s disease (Puschmann, 2013). The expression, activity and mitochondrial localization of the DJ-1 protein, which is encoded by the PARK7 gene, are regulated by oxidative stress. DJ-1 is a neuroprotective protein that protects cells from oxidative stress-induced death by positively regulating pathways such as mitophagy. High levels of oxidation or genetic mutations can inactivate DJ-1, which induces impairments in complex I activity and subsequent reactive oxygen species production, reduced membrane potential and fragmented mitochondrial morphology (Ariga et al., 2013). In healthy cells, mitochondrial turnover is regulated by PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) and the E3-ubiquitin ligase parkin in a process called mitophagy, which is the autophagy of damaged mitochondria. In functional mitochondria, PINK1 is translocated from the outer membrane to the inner membrane for degradation, while in dysfunctional mitochondria with a reduced membrane potential, PINK1 will accumulate on the outer mitochondrial membrane and serve as a receptor for recruitment of parkin (Jin et al., 2010; Lazarou et al., 2012). Parkin-mediated polyubiquitination of mitochondrial proteins recruits p62, which induces the aggregation of damaged mitochondria (Narendra et al., 2010). Failure of the turnover of accumulated damaged mitochondria by mitophagy leads to cell death.

Evidence for mitochondrial involvement in GBA1-associated Parkinson’s disease has now emerged (Gegg et al., 2012; Cleeter et al., 2013; Osellame et al., 2013). To mimic glucocerebrosidase deficiency, Cleeter and co-workers (2013) treated the human neuroblastoma SHSY-5Y cell line with the glucocerebrosidase suicide inhibitor CBE. Long-term treatment with CBE resulted in fragmentation of mitochondria, significant progressive decline in mitochondrial membrane potential, reduction of ATP synthesis and an increase in reactive oxygen species production. Although α-synuclein levels increased by ∼50%, surprisingly, the major routes for protein degradation and turnover such as the ERAD and the autophagy-lysosomal pathways were not affected. Although a stable partial GBA1 knockdown of 62% of enzyme activity confirmed the decline in mitochondrial membrane potential and increase in oxidative stress, it failed to show significant accumulation of α-synuclein (Cleeter et al., 2013). Another study performed on cultured primary midbrain neurons and astrocytes derived from a mouse model representative of acute neuronopathic Gaucher disease, revealed severe impairments in autophagy and ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated protein breakdown pathways, resulting in the accumulation of insoluble α-synuclein and ubiquitinated proteins. Mitochondrial dysfunction, due to defective mitochondrial complex I, led to increased reactive oxygen species production. Fragmented and dysfunctional mitochondria were not turned over by mitophagy because of a failure of recruitment of parkin to the mitochondrial membrane (Osellame et al., 2013). Both studies provide evidence for a link between mitochondrial function and the turnover and inhibition or absence of glucocerebrosidase. These studies indicate that there are similarities in cellular pathophysiological mechanisms in both type 2 Gaucher disease and Parkinson’s disease with regard to protein and organelle turnover pathways and energy homeostasis. To date, no studies using relevant neuronal cell and animal models or brain samples representing Parkinson’s disease with GBA1 mutations have addressed mitophagy and energy homeostasis. However, a study on SHSY-5Y cells silenced for PINK1, a cell model for familial Parkinson’s disease, showed significant reduction of glucocerebrosidase protein levels and activity that could be rescued by exogenous expression of wild-type PINK1 (Gegg et al., 2012).

Regulators of GBA1 and/or glucocerebrosidase expression and their implications in the synucleinopathies

It is now clear that Gaucher disease encompasses a broad spectrum of clinical phenotypes, with limited correlation between genotype and phenotype (Sidransky, 2004, 2012). This suggests the involvement of modifier genes that can interact with the disease-causing allele and influence its phenotypic expression (Goker-Alpan et al., 2005). Several potential modifiers for Gaucher disease have been proposed (Latham et al., 1990; Winfield et al., 1997; Montfort et al., 2004). Although mutations in GBA1 are a common risk factor for the development of Parkinson’s disease, only a fraction of patients with Gaucher disease and carriers for GBA1 mutations develop Parkinson’s disease (Sidransky et al., 2009). This leads us to speculate that potential disease modifiers in this process might serve as additional risk factors that, in combination with GBA1 mutations, might favour the development and progression of synucleinopathies.

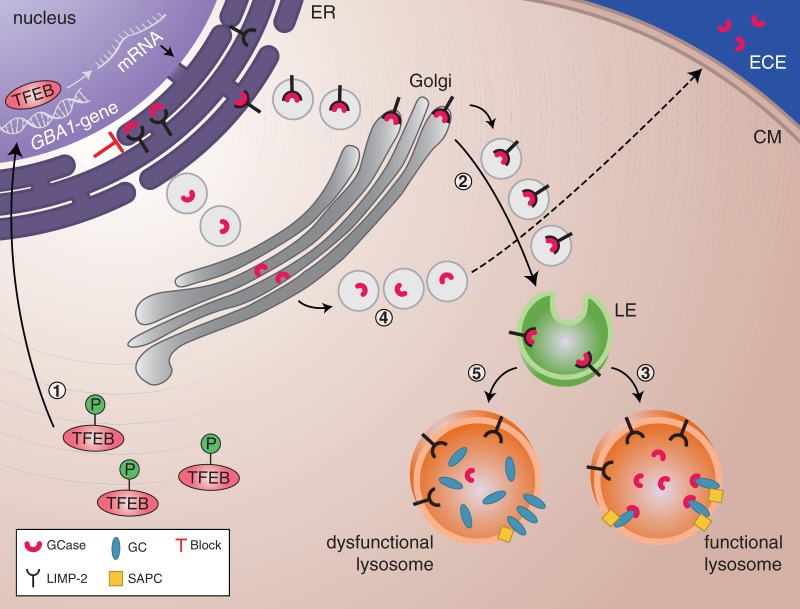

SCARB2/LIMP2: a genetic modifier of GBA1

Although the majority of lysosomal enzymes reach their destination via the mannose-6-phosphate receptor pathway, a subset gets sorted through mannose-6-phosphate receptor-independent pathways (Coutinho et al., 2012). One of these enzymes is glucocerebrosidase, which reaches the lysosome via lysosomal integral membrane protein type 2 (LIMP-2) mediated trafficking (Reczek et al., 2007) (Fig. 2). LIMP-2, encoded by the scavenger receptor class B member 2 (SCARB2) gene located on chromosome 4q13-21, belongs to the CD36 family of scavenger receptor proteins (Fujita et al., 1991; Febbraio et al., 2001; Berkovic et al., 2008). LIMP-2, which is ubiquitously expressed, is one of the most abundant transmembrane proteins in the lysosomal membrane (Eskelinen et al., 2003); mutation and over-expression studies suggest that it plays a role in the biogenesis and maintenance of late endosomes and lysosomes (Kuronita et al., 2002; Eskelinen et al., 2003), as well as in the fusion between lysosomes and autophagosomes (Gleich et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Regulators of GBA1 expression and glucocerebrosidase activity and trafficking. (1) Phosphorylated TFEB is located in the cytoplasm. Under starvation conditions, dephosphorylated TFEB translocates to the nucleus where it regulates the transcription of genes involved in the CLEAR network, including GBA1. (2) GBA1 messenger RNA is translated into glucocerebrosidase. The interaction with its receptor LIMP-2 facilitates translocation of glucocerebrosidase to the lysosomes via the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi and late endosomes (LE). (3) In the lysosomes, glucocerebrosidase dissociates from LIMP-2. The glucocerebrosidase activator, saposin C (SAPC), lifts glucocerebroside from the lysosomal membrane and/or membranes within the lysosome and makes it available for glucocerebrosidase-mediated breakdown. (4) When LIMP-2 is deficient or absent, the glucocerebrosidase enzyme cannot be correctly sorted to the lysosomes. As a consequence, glucocerebrosidase is secreted into the extracellular environment (ECE). (5) Saposin C deficiency leads to the impairment of glucocerebroside degradation since the substrate is not available to glucocerebrosidase and subsequently accumulates inside the lysosomes. CM = Cell Membrane.

It was not until 2007 that LIMP-2 was identified as the receptor required for the trafficking of glucocerebrosidase to the lysosomes (Reczek et al., 2007). Protein interaction studies showed a pH-dependent interaction between LIMP-2 and glucocerebrosidase, which was regulated by the pH-sensor amino acid histidine 171 (Zachos et al., 2012). This direct interaction between glucocerebrosidase and LIMP-2 is initiated at neutral pH within the endoplasmic reticulum, and is disrupted upon reaching the acidic lysosome (Reczek et al., 2007; Blanz et al., 2010; Zachos et al., 2012). Studies of SCARB2 knock-out mice showed GBA1 messenger RNA levels were not affected, but there was a decrease in glucocerebrosidase activity and protein levels along with lysosomal accumulation of glucocerebroside (Reczek et al., 2007). Conditioned media taken from SCARB2 knock-out cells in culture demonstrate that glucocerebrosidase is secreted into the extracellular environment as a result of impaired trafficking of glucocerebrosidase (Reczek et al., 2007; Velayati et al., 2011). Mutations in SCARB2 are associated with action myoclonus-renal failure syndrome (OMIM #254900), an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by renal pathology, progressive myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia (Berkovic et al., 2008; Blanz et al., 2010). Studies on four different mutant SCARB2 lines showed that the mutant proteins are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and affect glucocerebrosidase activity in the lysosomes by binding to glucocerebrosidase in the endoplasmic reticulum and preventing its translocation to the lysosomes (Balreira et al., 2008; Blanz et al., 2010). SCARB2 was recently identified as a genetic modifier for GBA1 in a study of a unique pair of siblings who had discordant Gaucher disease phenotypes but identical genotypes. One sib suffered myoclonic seizures and sequencing of his SCARB2 gene revealed a novel heterozygous c.1412A>G (p.Glu471Gly) mutation in one allele, which was absent from the brother. Expression studies in fibroblasts from this patient revealed significant downregulation of LIMP-2 and glucocerebrosidase protein levels, as well as glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity. Secretion of mature glucocerebrosidase into the extracellular environment was observed (Velayati et al., 2011). As LIMP-2 is crucial for the correct trafficking of glucocerebrosidase, and LIMP-2 malfunction can lead to a reduction in glucocerebrosidase levels and activity, it is tempting to speculate a role for LIMP-2 in the development of Parkinson’s disease. SCARB2 mutations and Parkinson’s disease could be related through the modulation of glucocerebrosidase protein levels and activity in the cell. LIMP-2 deficiency could lead to glucocerebrosidase secretion instead of proper delivery to the lysosome, which could result in accumulation of glucocerebroside substrate, alterations in lysosomal function, and aggregation of proteins such as α-synuclein inside the lysosomes. It was demonstrated in a cell model over-expressing α-synuclein that less glucocerebrosidase was bound to LIMP-2, which indicates less translocation of glucocerebrosidase to the lysosome (Gegg et al., 2012).

It still remains unclear how a variation near or inside SCARB2 could be associated with Parkinson’s disease (Hopfner et al., 2013). Recent genetic-based evidence has suggested an association between SCARB2 and Parkinson’s disease. Genome-wide association studies identified an association between rs6812193, a single nucleotide polymorphism located upstream of the SCARB2 gene, and Parkinson’s disease (OR = 0.84) in a population of European ancestry (Do et al., 2011). The single nucleotide polymorphism is located in an intron of FAM47E, a gene encoding a protein of unknown function (Do et al., 2011). This association was confirmed by the International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium (2011) in a two-stage meta-analysis, and further supported by an independent genotyping study of 984 patients with Parkinson’s disease and 1014 controls of German/Austrian descent (Hopfner et al., 2013). However, the association was not seen in a Chinese study of 449 patients with Parkinson’s disease and 452 controls (Chen et al., 2012; Hopfner et al., 2013). A candidate gene screen, performed on 347 subjects with sporadic Parkinson’s disease and 329 controls from Greece, revealed an additional single nucleotide polymorphism, rs6825004, located within intron 2 of SCARB2, that appeared to be associated with Parkinson’s disease (OR = 0.68). However, the authors recognized the limitations in their study because of the small sample size (Michelakakis et al., 2012). In another small study, the presence of rs6812193 and/or rs6825004 single nucleotide polymorphisms and corresponding SCARB2 and LIMP-2 expression levels were assessed in 15 lymphocyte and leucocyte samples derived from individuals without Parkinson’s disease. There was no indication that the SCARB2 single nucleotide polymorphism genotypes described were associated with the modulation of SCARB2 messenger RNA and LIMP-2 protein expression levels (Maniwang et al., 2013).

Saposin C: an activator of glucocerebrosidase

Mature saposin C (SAPC) is a glucocerebrosidase enzyme activator in lysosomes and is essential in the hydrolysis of glucocerebroside (Beutler and Grabowski, 2001; Sidransky, 2004; Vaccaro et al., 2010), but the mechanism for this activation is not fully understood. Saposin A, B, C, and D are small homologous glycoproteins with six cysteine residues forming disulphide bridges. The bridges are crucial for saposin C function (Tamargo et al., 2012). Saposin proteins are generated through proteolytic cathepsin D-mediated cleavage of its precursor prosaposin (Hiraiwa et al., 1997; Yuan and Morales, 2011). Biophysical experimental evidence indicates that saposin C-mediated extraction and solubilization of glucocerebroside exposes the lipid substrate to glucocerebrosidase for subsequent hydrolysis (Alattia et al., 2006, 2007) (Fig. 2). An additional role for saposin C is the protection of glucocerebrosidase against proteolytic breakdown, which is demonstrated by a significant reduction in levels of glucocerebrosidase protein and enzyme activity in saposin C-deficient cells (Sun et al., 2003, 2010). Because of its essential role as a glucocerebrosidase activator, saposin C could be a modifier gene for Gaucher disease and potentially Parkinson’s disease. Indeed, crossbreeding studies with a mouse model of saposin C, created by a knock-in mutation in exon 11 of the prosaposin gene, and the V394L homozygous Gaucher mouse (Xu et al., 2003; Hruska et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010), revealed that the combined deficiencies exacerbate the Gaucher disease phenotype, with progressive neurological complications resulting in early death, greater glucocerebrosidase activity reduction, significant defects in glucocerebroside 18:0 species breakdown in the brain, and increased storage of the substrates glucocerebroside and glucosylsphingosine (Sun et al., 2013b). This model confirmed that saposin C could act as a disease modifier for Gaucher disease. Only six patients with saposin C deficiency have been described in the literature and a correlation was observed between the type of mutation and the nature of their Gaucher-like phenotype. Patients with mutations in the crucial cysteine residues in the saposin C domain of prosaposin had a clinical phenotype similar to Gaucher disease type 3, whereas those with other mutations resembled non-neuronopathic type 1 Gaucher disease (Christomanou et al., 1986, 1989; Schnabel et al., 1991; Rafi et al., 1993; Diaz-Font et al., 2005; Tylki-Szymanska et al., 2007, 2011; Vaccaro et al., 2010). Complete deficiency of prosaposin and consequently all saposins, resulted in a severe fatal neurological infantile sphingolipidosis (Hulkova et al., 2001). As patients with both saposin C and glucocerebrosidase deficiencies have never been identified, it is difficult to assess the role of saposin C as a modifier gene in human samples. Interestingly, patient fibroblasts with cysteine saposin C mutations showed an accumulation of autophagosomes, which was believed to be caused by reduced protein levels and enzymatic activity of both cathepsin B and D (Tatti et al., 2011, 2012, 2013). Exogenous over-expression of both cathepsins restored autolysosomal degradation (Tatti et al., 2013). This secondary effect of saposin C deficiency is of great interest as malfunctions in the autophagy clearance pathway and their role in the development of Parkinson’s disease are well documented (Lim and Zhang, 2013), as is the role of cathepsin D in proteolytic breakdown of α-synuclein (Cullen et al., 2009). Although saposin C can act as a modifier gene for Gaucher disease in a mouse model (Sun et al., 2010), appropriate saposin C expression studies on samples from patients with Gaucher disease with discordant phenotypes are currently lacking. Also, considering the recent observations of reduced wild-type glucocerebrosidase activity in Parkinson’s disease models and patient samples, it is possible that altered saposin C levels in patients with Parkinson’s disease (with or without GBA1 mutations) could be a crucial determinant in the development of synucleinopathies.

TFEB: a regulator of GBA1/glucocerebrosidase expression

A majority of the genes involved in both lysosomal function and biogenesis are part of the coordinated lysosomal expression and regulation network. Expression of gene members of this network is positively regulated by the basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor EB (TFEB), which binds to the GTCACGTGAC motif element within their promoter region (Sardiello et al., 2009). Work by Ballabio and colleagues established that TFEB is part of a signalling pathway by which lysosomes self-regulate. Indeed, experimental data in Drosophila S2, human HEK293T cells, and a cell-free system support an ‘inside-out’ model in which accumulated amino acids inside the lysosome initiate signalling through the v-ATPase-Ragulator protein complex to Rag-GTPases, which, in turn, recruit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) to the surface of the lysosomes (Sancak et al., 2008, 2010; Zoncu et al., 2011). TFEB interacts with mTOR on the lysosomal surface, where phosphorylation of multiple serine residues by mTOR prevents TFEB translocation to the nucleus (Settembre and Ballabio, 2011; Settembre et al., 2012; Martina and Puertollano, 2013). Cell starvation, which includes amino acid depletion within the lysosome, results in inhibition of the ‘inside-out’ signalling pathway, and eventual mTOR release from the lysosome surface. TFEB is no longer phosphorylated, and translocates to the nucleus, where it activates transcription of the coordinated lysosomal expression and regulation network genes and autoregulates its own expression through a feedback loop (Settembre et al., 2012, 2013). In addition to its role in lysosomal function and biogenesis, TFEB is also a key player in lipid metabolism (Settembre et al., 2013), autophagosome formation and autophagosome-lysosome fusion (Settembre and Ballabio, 2011), and Ca2+-mediated lysosomal exocytosis, which can positively affect cellular substrate clearance in select lysosomal storage disorders, including Batten disease, Pompe disease, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses, multiple sulphatase deficiency, and mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA (Medina et al., 2011).

TFEB over-expression and silencing studies in HeLa cells showed that TFEB positively regulated GBA1 messenger RNA expression (Fig. 2). Additionally, chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis confirmed that GBA1 is a direct target of TFEB (Sardiello et al., 2009). The TFEB field is still in its infancy and very few studies on its role in neurodegeneration are available. One study showed that adenovirus-mediated over-expression of human α-synuclein in the midbrain of rats induced TFEB retention in the cytoplasm, blockage of lysosomal function, accumulation of α-synuclein in autophagosomes, and progressive build-up of α-synuclein oligomers. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed an interaction between α-synuclein and TFEB, suggestive of a role for α-synuclein in cytoplasmic sequestration of TFEB. These observations were confirmed in nigral dopaminergic neurons of post-mortem Parkinson’s disease midbrains. In the α-synuclein rat model, both over-expression of TFEB or activation through pharmacological inhibition of mTOR resulted in a block in the progression of α-synuclein-mediated neurodegeneration. This study puts TFEB on the map as a key player in Parkinson’s disease (Decressac et al., 2013). Recently, reduced wild-type glucocerebrosidase protein levels were observed in samples from patients with synucleinopathies (Balducci et al., 2007; Parnetti et al., 2009; Gegg et al., 2012). It is possible that this could be because of α-synuclein-induced TFEB retention in the cytoplasm with consequently lower transcription of GBA1 messenger RNA. Currently, TFEB is the only known transcription factor for GBA1, but a study of the promoter and regulatory regions of GBA1 revealed several conserved transcription factor-binding sites resulting in altered GBA1 expression levels when mutated. This suggests that these regions might be involved in transcriptional regulation of GBA1 and potentially contribute to the complex phenotypic diversity observed in Gaucher disease including the development of Parkinson’s disease (Blech-Hermoni et al., 2010).

Therapeutics for Gaucher disease may have promise for the treatment of the synucleinopathies

As previously mentioned in this review, studies performed on cell free systems, cell and animal models, and patient samples have demonstrated that knockdown of GBA1 expression, the introduction of GBA1 mutations, inhibition by CBE, or treatment with glucocerebroside substrate all enhance accumulation and/or oligomerization of α-synuclein (Manning-Bog et al., 2009; Cullen et al., 2011; Mazzulli et al., 2011; Sardi et al., 2011, 2013; Gegg et al., 2012; Cleeter et al., 2013; Osellame et al., 2013). On the other hand, upregulation of α-synuclein levels decrease glucocerebrosidase protein and activity levels in cell-free systems, cell and mouse models, and post-mortem brains of Parkinson’s disease patients with and without GBA1 mutations (Mazzulli et al., 2011; Sardi et al., 2011, 2013; Yap et al., 2011, 2013; Gegg et al., 2012). This reciprocal relationship between glucocerebrosidase activity and α-synuclein levels has generated great interest in the potential role of Gaucher disease therapeutics for the treatment of the synucleinopathies (Sardi et al., 2013; Schapira and Gegg, 2013). Therapies for Gaucher disease, which are targeted towards augmenting glucocerebrosidase activity or decreasing glucocerebroside storage, could prove to be promising strategies for modulating α-synuclein proteostasis and its subsequent aggregation and oligomerization. This rational was supported by experimental evidence showing that viral-mediated infection into the central nervous system of a mouse model with GBA1 mutations representing neuronopathic Gaucher disease and a transgenic mouse model over-expressing A53T α-synuclein without GBA1 mutations significantly reduced α-synuclein levels (Sardi et al., 2013). This set a paradigm for augmentation of glucocerebrosidase activity as a beneficial therapeutic strategy for halting disease progression in patients with Parkinson’s disease, both with and without GBA1 mutations, and even preventing the onset of Parkinson’s disease in healthy individuals. In this review, we address FDA-approved and ‘under development’ therapeutics for Gaucher disease and their potential implications for treatment of the synucleinopathies.

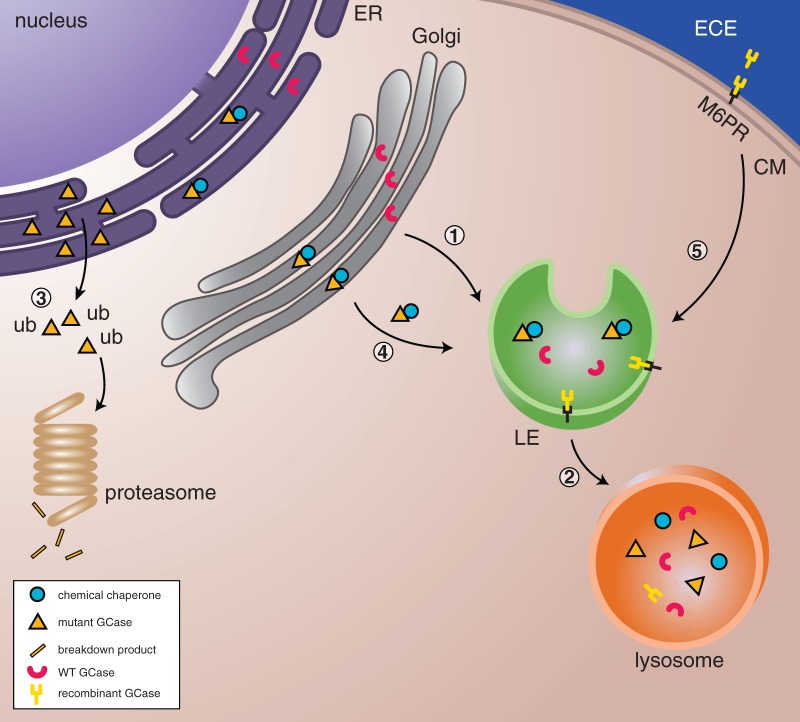

The first available FDA-approved therapy for Gaucher disease was enzyme replacement therapy, which was developed at the National Institutes of Health. Patients with Gaucher disease type 1 received intravenous infusion of exogenous enzyme, which improved haematologic and visceral manifestations and reduced glucocerebroside levels (Brady et al., 1974; Barton et al., 1991). Currently, three different recombinant enzymes are commercially available, imiglucerase, taliglucerase alfa, and velaglucerase alfa. Although each of the enzymes differ in their cell system production and glycosylation pattern, the function and biodistribution of all three enzymes are comparable (Tekoah et al., 2013) (Fig. 3). As intravenous enzyme replacement therapy does not cross the blood–brain barrier it does not ameliorate neurological manifestations and would not be suitable for treatment of Parkinson’s disease neuropathology (Erikson, 2001; Beck, 2007). In fact, patients with Gaucher disease undergoing enzyme replacement therapy have still gone on to develop Parkinson’s disease.

Figure 3.

Therapeutic strategies to enhance glucocerebrosidase. (1 and 2) In healthy cells, wild-type glucocerebrosidase (WT GCase) is sorted to the lysosome via the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi, and late endosomes (LE) where it will degrade its substrate glucocerebroside. (3) Mutant glucocerebrosidase is misfolded in the endoplasmic reticulum, becomes polyubiquitinated (ub) and undergoes proteasome-mediated degradation. (4) Pharmacological chaperones can stabilize mutant glucocerebrosidase and facilitate translocation to lysosomes. (5) In enzyme replacement therapy, recombinant glucocerebrosidase enzyme is delivered into the cells via the mannose-6-phosphate receptor and trafficked through the late endosomes to the lysosomes where it is able to degrade substrate. CM = Cell Membrane.

The accumulation of glucocerebroside in the lysosome can impact α-synuclein breakdown and oligomerization (Mazzulli et al., 2011), which suggests that therapeutic reduction of excessive glucocerebroside substrate could potentially be beneficial for Parkinson’s disease. Therapeutic inhibition of the enzyme glucosylceramide synthase, which catalyzes the synthesis of glucocerebroside, attenuates glucocerebroside production and has been used as a form of substrate reduction therapy. Treatment of patients with Gaucher disease with two glucosylceramide synthase inhibitors, miglustat (N-butyldeoxynojirimycin) and eliglustat tartrate, resulted in visceral and hematopoietic improvement but failed to impact neurological manifestations (Lukina et al., 2010). Recently, a screening effort of novel compounds identified the compound GZ 161, which successfully reduced both glucocerebroside and glucosylsphingosine accumulation in the brain of the K14 acute neuronopathic Gaucher disease mouse model and significantly increased their lifespan (Cabrera-Salazar et al., 2012).

Another approach gaining much momentum in the field of lysosomal storage disorders is pharmacological chaperone therapy. The proper folding process of glucocerebrosidase takes place in the endoplasmic reticulum by direct interaction with endogenous cellular chaperones such as heat shock protein 90 and heat shock protein 70 (Lu et al., 2011). Studies have demonstrated that several disease-causing glucocerebrosidase mutants are misfolded and do not pass the ERAD quality control system, which leads to early proteasome-mediated degradation (Ron and Horowitz, 2005; Ron et al., 2010; Bendikov-Bar et al., 2011; Bendikov-Bar and Horowitz, 2012; Maor et al., 2013a, b). Therapy with pharmacological chaperones, which specifically bind to the newly synthesized mutant enzyme, can prevent premature ERAD and promote trafficking to the lysosome, where most mutant glucocerebrosidase proteins can exert sufficient residual enzyme activity for the breakdown of accumulated lysosomal glucocerebroside (Lieberman et al., 2009; Bendikov-Bar et al., 2013) (Fig. 3). The drawback of such a therapeutic approach is that translation of mutated glucocerebrosidase and an intact chaperone-binding site are required. Treatment will not be effective in the case of null alleles, large deletions, or mutations affecting the chaperone-binding site. Many of the pharmacological chaperones are inhibitors of glucocerebrosidase that bind to its active site. Ambroxol is a pH-dependent mixed inhibitor of glucocerebrosidase that was identified by screening of an FDA-approved drug library (Maegawa et al., 2009); it is a potent chaperone for the translocation of mutant glucocerebrosidase to lysosomes (Bendikov-Bar et al., 2011, 2013; Babajani et al., 2012; Luan et al., 2013). One limited pilot study conducted in a small group of patients with Gaucher disease indicated amelioration of clinical symptoms after ambroxol treatment (Zimran et al., 2013), but its efficacy in relevant Parkinson’s disease models has not yet been evaluated. Another glucocerebrosidase inhibitor, Isofagomine, showed great efficacy in cell and mouse models of Gaucher disease, resulting in increased glucocerebrosidase protein levels and enzyme activity, reduction in levels of glucocerebroside and glucosylsphingosine, delayed neurological manifestations, and increased life span (Khanna et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2011, 2012), but improvement in clinical symptoms were not observed in a phase 2 clinical trial (Zimran, 2011). In a cell model for Parkinson’s disease consisting of PC12 cells over-expressing α-synuclein and transfected with wild-type or mutant glucocerebrosidase, the efficacy of isofagomine treatment on α-synuclein levels was non-significant (Cullen et al., 2011); its efficacy in relevant in vivo models of Parkinson’s disease remains to be investigated. Clinical development of these inhibitory chaperones has major obstacles as both drug dosage and the length of treatment have to be carefully optimized for high endoplasmic reticulum to lysosome chaperone activity, yet minimal lysosomal enzyme inhibition. This can be circumvented by using pharmacological chaperones that both facilitate the lysosomal translocation and residual activity of mutant glucocerebrosidase without enzyme inhibition. Recent efforts have identified promising activators that increase translocation and enzyme activity of mutant glucocerebrosidase in fibroblasts (Goldin et al., 2012; Patnaik et al., 2012).

As ERAD is a major player in the premature degradation of many glucocerebrosidase mutants, targeting proteins that regulate the proteostasis of mutated glucocerebrosidase could serve as an alternative therapy. Recently, histone deacetylase inhibitors were identified as modulators of heat shock protein 90-dependent degradation of mutated glucocerebrosidase by inhibiting the deacetylation of heat shock protein 90. Treatment resulted in increased glucocerebrosidase protein levels and enzyme activity in Gaucher disease fibroblasts (Lu et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013). Future development of histone deacetylase inhibitors for therapeutics might prove challenging, as the target of this therapy remains broad rather than glucocerebrosidase-specific. Additionally, the exact molecular mechanism of regulation of proteostasis by histone deacetylase inhibitors remains unclear.

Other lysosomal storage disorders and the development of the synucleinopathies

There are >50 different lysosomal storage disorders. There have been several individual case reports of patients and carriers with specific lysosomal storage disorders that suggest that there may be neuropathological findings suggestive of Parkinson’s disease, with reports of α-synuclein accumulation and inclusions, and the loss of neurons in the substantia nigra. This indicates that it might be worthwhile to expand research into defects in the cellular pathways that link synucleinopathies with changes in glucocerebrosidase protein amount and activity to a variety of enzymes involved in lysosomal storage disorders (reviewed by Shachar et al., 2011). Recently, molecular studies screening for mutations for genes involved in specific lysosomal storage disorders shed new light on the association with synucleinopathies.

Niemann-Pick disease is a lysosomal storage disorder with heterogeneous clinical features and severity. Types A (OMIM #257200) and B (OMIM #607616) are both associated with a deficiency of the acid sphingomyelinase enzyme, which is encoded by the sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase gene, and catalyzes the breakdown of sphingomyelin into ceramide and phosphorylcholine in lysosomes. Acid sphingomyelinase deficiency results in sphingomyelin accumulation in phagocytic cells and neurons resulting in clinical symptoms such as failure to thrive, hepatosplenomegaly and progressive neurodegeneration (Vanier, 2013). Two recent independent reports identified variations in the sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase gene as risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Gan-Or and colleagues (2013) identified the founder mutation to be associated with Parkinson’s disease with an odds ratio of 9.4 in two Ashkenazi Jewish Parkinson’s disease patient cohorts consisting of 938 patients (Gan-Or et al., 2013). Another variant (p.R591C) increasing the risk for Parkinson’s disease was identified from a cohort of 1004 patients of Chinese ancestry (Foo et al., 2013).

Sanfilippo syndrome B or Mucopolysaccharidosis type III B (OMIM #252920) is an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder caused by mutations in the α-N-acetylglucosaminidase gene leading to the accumulation of heparan sulphate in lysosomes. Clinical symptoms range from mild to severe and include progressive neurodegeneration, skeletal changes, and behavioural problems (Chinen et al., 2005). Allelic analysis of two single nucleotide polymorphisms in α-N-acetylglucosaminidase on DNA samples of 926 patients with Parkinson’s disease and 2308 control subjects showed an association between rs2071046 and an increased risk for developing Parkinson’s disease (Winder-Rhodes et al., 2012).

Wu et al. (2008) measured enzyme activity of 11 lysosomal hydrolases in peripheral blood leucocytes of 38 patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease and 258 controls. Only the activity of alpha-galactosidase A was significantly reduced. Deficiency in alpha-galactosidase A causes the X-linked lysosomal storage disorder Fabry disease (OMIM#301500), which is characterized by lysosomal storage of globotriaosylceramides and glycosphingolipids (Desnick et al., 2001). Interestingly, in this study glucocerebrosidase did not show significant reduction in enzyme activity in peripheral blood leucocytes of patients with Parkinson’s disease compared to controls (Wu et al., 2008). A molecular follow-up study identified no differences in the frequency of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter and exonic regions of the alpha-galactosidase gene in patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease and healthy control subjects (Wu et al., 2011).

Concluding remarks

Recent insights into the relationship between glucocerebrosidase (wild-type and mutant) and α-synuclein in the synucleinopathies have shed new light on the cellular mechanism of α-synuclein pathology in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. As only a minority of patients with Gaucher disease, GBA1 mutation carries, or individuals in the overall population develop synucleinopathies, it is apparent that the delicate balance between α-synuclein proteostasis and glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity must be affected by other modifiers manipulating glucocerebrosidase or α-synuclein levels. It will be of interest to investigate some of the potential modifiers in cell and animal models, as well as in patient samples. This new understanding of balancing α-synuclein proteostasis by correcting glucocerebrosidase enzyme levels holds novel possibilities for the future treatment of parkinsonism. Glucocerebrosidase-specific pharmacological chaperones, especially activators that cross the blood–brain barrier, will be of great interest in this endeavour. Finally, limited research on other lysosomal storage disorders suggests that mutations in other lysosomal enzymes may similarly play a role as risk factors for the synucleinopathies, but it remains to be seen whether the activity of these enzymes also affect α-synuclein proteostasis. This story clearly illustrates how studies into the pathogenesis and therapy of a rare genetic disorder can lead to advances impacting the multitudes of patients with common complex diseases like Parkinson’s disease worldwide.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Julia Fekecs for assistance with drafting of the figures and Dr. Elma Aflaki and Ashley Gonzalez for critical comments and careful reading of the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CBE

conduritol-B-epoxide

- ERAD

endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

- GBA1

glucocerebrosidase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- PERK

RNA-activated protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute and the National Institutes of Health. M.S. received support by the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education – CAPES and Fulbright Brazil.

References

- Abeliovich A, Schmitz Y, Farinas I, Choi-Lundberg D, Ho WH, Castillo PE, et al. Mice lacking alpha-synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron. 2000;25:239–52. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alattia JR, Shaw JE, Yip CM, Prive GG. Direct visualization of saposin remodelling of lipid bilayers. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:943–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alattia JR, Shaw JE, Yip CM, Prive GG. Molecular imaging of membrane interfaces reveals mode of beta-glucosidase activation by saposin C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17394–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704998104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Erviti L, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Cooper JM, Caballero C, Ferrer I, Obeso JA, et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy markers in Parkinson disease brains. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1464–72. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Schapira AH, Gardiner C, Sargent IL, Wood MJ, et al. Lysosomal dysfunction increases exosome-mediated alpha-synuclein release and transmission. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:360–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anheim M, Elbaz A, Lesage S, Durr A, Condroyer C, Viallet F, et al. Penetrance of Parkinson disease in glucocerebrosidase gene mutation carriers. Neurology. 2012;78:417–20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318245f476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias E, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy in protein quality control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:184–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariga H, Takahashi-Niki K, Kato I, Maita H, Niki T, Iguchi-Ariga SM. Neuroprotective function of DJ-1 in Parkinson's disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:683920. doi: 10.1155/2013/683920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayto R, Hughes DA. Gaucher disease and myeloma. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013;18:247–68. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.2013006061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babajani G, Tropak MB, Mahuran DJ, Kermode AR. Pharmacological chaperones facilitate the post-ER transport of recombinant N370S mutant beta-glucocerebrosidase in plant cells: evidence that N370S is a folding mutant. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;106:323–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balducci C, Pierguidi L, Persichetti E, Parnetti L, Sbaragli M, Tassi C, et al. Lysosomal hydrolases in cerebrospinal fluid from subjects with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1481–4. doi: 10.1002/mds.21399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balreira A, Gaspar P, Caiola D, Chaves J, Beirao I, Lima JL, et al. A nonsense mutation in the LIMP-2 gene associated with progressive myoclonic epilepsy and nephrotic syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2238–43. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton NW, Brady RO, Dambrosia JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Doppelt SH, Hill SC, et al. Replacement therapy for inherited enzyme deficiency–macrophage-targeted glucocerebrosidase for Gaucher's disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1464–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105233242104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M. New therapeutic options for lysosomal storage disorders: enzyme replacement, small molecules and gene therapy. Hum Genet. 2007;121:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JG, Pastores GM, Di Rocco A, Ferraris M, Graber JJ, Sathe S. Parkinson's disease in patients and obligate carriers of Gaucher disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19:129–31. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci A, Navarria L, Zaltieri M, Falarti E, Bodei S, Sigala S, et al. Induction of the unfolded protein response by alpha-synuclein in experimental models of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 2011;116:588–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bembi B, Zambito Marsala S, Sidransky E, Ciana G, Carrozzi M, Zorzon M, et al. Gaucher's disease with Parkinson's disease: clinical and pathological aspects. Neurology. 2003;61:99–101. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000072482.70963.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendikov-Bar I, Horowitz M. Gaucher disease paradigm: from ERAD to comorbidity. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1398–407. doi: 10.1002/humu.22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendikov-Bar I, Maor G, Filocamo M, Horowitz M. Ambroxol as a pharmacological chaperone for mutant glucocerebrosidase. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2013;50:141–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendikov-Bar I, Ron I, Filocamo M, Horowitz M. Characterization of the ERAD process of the L444P mutant glucocerebrosidase variant. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2011;46:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovic SF, Dibbens LM, Oshlack A, Silver JD, Katerelos M, Vears DF, et al. Array-based gene discovery with three unrelated subjects shows SCARB2/LIMP-2 deficiency causes myoclonus epilepsy and glomerulosclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:673–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovic SF, Dibbens LM, Oshlack A, Silver JD, Katerelos M, Vears DF, et al. Array-based gene discovery with three unrelated subjects shows SCARB2/LIMP-2 deficiency causes myoclonus epilepsy and glomerulosclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:673–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler E, Grabowski GA. Gaucher disease. In: Scriver CBA, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The metabolic & molecular bases of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 3635–68. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler E, Nguyen NJ, Henneberger MW, Smolec JM, McPherson RA, West C, et al. Gaucher disease: gene frequencies in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:85–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer K, Ariza A. Protein aggregation mechanisms in synucleinopathies: commonalities and differences. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:965–74. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3181587d64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegstraaten M, van Schaik IN, Aerts JM, Langeveld M, Mannens MM, Bour LJ, et al. A monozygotic twin pair with highly discordant Gaucher phenotypes. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2011;46:39–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanz J, Groth J, Zachos C, Wehling C, Saftig P, Schwake M. Disease-causing mutations within the lysosomal integral membrane protein type 2 (LIMP-2) reveal the nature of binding to its ligand beta-glucocerebrosidase. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:563–72. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blech-Hermoni YN, Ziegler SG, Hruska KS, Stubblefield BK, Lamarca ME, Portnoy ME, et al. In silico and functional studies of the regulation of the glucocerebrosidase gene. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady RO, Pentchev PG, Gal AE, Hibbert SR, Dekaban AS. Replacement therapy for inherited enzyme deficiency. Use of purified glucocerebrosidase in Gaucher's disease. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:989–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197411072911901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky JL. Cleaning up: ER-associated degradation to the rescue. Cell. 2012;151:1163–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]