ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Young adults with hypertension have the lowest prevalence of controlled blood pressure compared to middle-aged and older adults. Uncontrolled hypertension, even among young adults, increases future cardiovascular event risk. However, antihypertensive medication initiation is poorly understood among young adults and may be an important intervention point for this group.

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study was to compare rates and predictors of antihypertensive medication initiation between young adults and middle-aged and older adults with incident hypertension and regular primary care contact.

DESIGN

A retrospective analysis

PARTICIPANTS

Adults ≥ 18 years old (n = 10,022) with incident hypertension and no prior antihypertensive prescription, who received primary care at a large, Midwestern, academic practice from 2008–2011.

MAIN MEASURES

The primary outcome was time from date of meeting hypertension criteria to antihypertensive medication initiation, or blood pressure normalization without medication. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate the probability of antihypertensive medication initiation over time. Cox proportional-hazard models (HR; 95 % CI) were fit to identify predictors of delays in medication initiation, with a subsequent subpopulation analysis for young adults (18–39 years old).

KEY RESULTS

After a mean follow-up of 20 (±13) months, 34 % of 18–39 year-olds with hypertension met the endpoint, compared to 44 % of 40–59 year-olds and 56 % of ≥ 60 year-olds. Adjusting for patient and provider factors, 18–39 year-olds had a 44 % slower rate of medication initiation (HR 0.56; 0.47–0.67) than ≥ 60 year-olds. Among young adults, males, patients with mild hypertension, and White patients had a slower rate of medication initiation. Young adults with Medicaid and more clinic visits had faster rates.

CONCLUSIONS

Even with regular primary care contact and continued elevated blood pressure, young adults had slower rates of antihypertensive medication initiation than middle-aged and older adults. Interventions are needed to address multifactorial barriers contributing to poor hypertension control among young adults.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2790-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: hypertension, ambulatory care, disease management

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, at least one in ten young adults1 (18–39 year-olds) have hypertension.2 However, young adults with hypertension have the lowest prevalence of blood pressure control (38 %) compared to middle-aged (55 %) and older adults (53 %).2,3 In addition, young adults diagnosed with hypertension have the lowest prevalence of antihypertensive medication treatment (49 %) compared to middle-aged (73 %) and older adults (80 %).3,4 Antihypertensive medication initiation is poorly understood among young adults, and may be an important intervention point to improve hypertension control among young adults who require medication.

Hypertension in young adulthood increases the risk of future cardiovascular events.5 Following lifestyle modifications, the JNC 7 guidelines recommend the initiation of antihypertensive medication if the blood pressure remains elevated.6 It has been demonstrated that once medication is initiated, young adults can achieve a higher prevalence of hypertension control (> 60 %),1,7 and within a shorter time than older adults.8 Prior work suggested that young adults with elevated blood pressures are less likely than older adults to receive antihypertensive medication even after lifestyle modification attempts.3,4,9

Previous studies evaluating predictors of antihypertensive medication initiation have focused primarily on middle-aged and older adults. These studies highlighted a lack of a usual source of medical care, fewer medical visits, and milder blood pressure elevation as contributors to low rates of antihypertensive medication initiation.3,10–12 The few previous studies evaluating rates and predictors of antihypertensive medication in young adults were limited by a small sample size and/or focused on young adults with poor access to care.1,13,14 Therefore, the objectives of our study were to compare rates and predictors of antihypertensive medication initiation in a large young adult population (18–39 years old) with incident hypertension and regular primary care contact, to middle-aged (40–59 years old) and older adults (≥60 years old), with a long-term goal of informing the design of quality interventions to improve hypertension control in younger adults.

METHODS

Sample

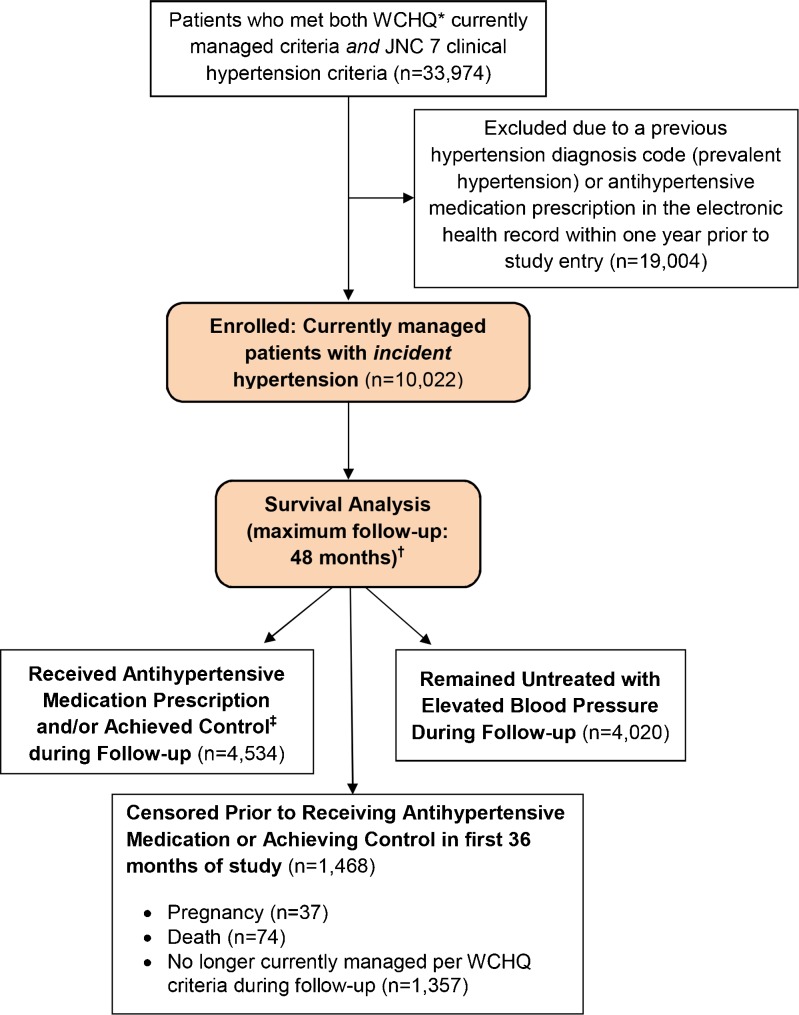

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent, and consisted of a secondary retrospective analysis of electronic medical record data from a large, Midwestern, multi-disciplinary academic group practice. We first identified all patients ≥ 18 years who met established criteria from the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (WCHQ)15,16 for being “currently managed” in the practice between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2011. WCHQ is a multi-stakeholder, voluntary consortium of Wisconsin organizations committed to publicly reporting performance measures of quality and affordability of healthcare services.17 Per WCHQ, patients had to have ≥ 2 billable office encounters in an outpatient, non-urgent, primary care setting, or one primary care and one office encounter in urgent care (regardless of diagnosis code), in the 3 years prior to study enrollment, with at least one of those visits in the prior 2 years.18 Patients were defined as receiving regular primary care contact if they met criteria for being “currently managed”. Patient records were then evaluated for the first date that JNC 7 clinical blood pressure criteria for a new diagnosis of hypertension6 (incident hypertension) were met. A patient met blood pressure eligibility criteria based on the following electronic health record data: a) ≥ 3 outpatient blood pressure measurements from three separate dates, ≥ 30 days apart but within a 2-year span (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg)6 or b) two elevated blood pressures19,20 (systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mmHg), ≥ 30 days apart, but within a 2-year period. The blood pressures did not need to be from billable encounters. If more than one blood pressure was taken at a visit, the average was used.6 A total of 33,974 patients met both JNC 7 blood pressure eligibility criteria for incident hypertension and WCHQ “currently managed” criteria (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study sample: enrollment and analysis. *WCHQ: Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality. † Mean follow-up: 20 (±13) months; ‡ Achieved hypertension control prior to medication initiation.

The 365 days prior to study enrollment was the “baseline period” to assess patients’ baseline comorbidities and utilization. To achieve a final sample with incident hypertension, patients were then excluded if they had an antihypertensive medication prescription or a prior hypertension diagnosis in the baseline period per the Tu criteria.21 The Tu algorithm for administrative data is used to define patients who have been diagnosed with hypertension using the following ICD-9 codes:21 401.x (essential hypertension), 402.x (hypertensive heart disease), 403.x (hypertensive renal disease), 404.x (hypertensive heart and renal disease), 405.x (secondary hypertension). Pregnant patients were also excluded one year before, during, and one year after pregnancy using a modified Manson approach.22 After these exclusion criteria, our final sample included 10,022 primary care patients meeting clinical criteria for incident hypertension.

Patients were enrolled in the study from the date they met criteria for being both currently managed and having incident hypertension without prior treatment. Patients continued to accrue time in this study until: a) an antihypertensive medication was prescribed as recorded in the outpatient electronic health record; b) they achieved blood pressure control before antihypertensive medication initiation; or c) censoring. Blood pressure control was defined per JNC 7 as three consecutive normal blood pressures on three separate dates (< 130/80 mmHg if diagnosed with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease; otherwise < 140/90 mmHg).6 Patients were censored if they died (censored day of death) or were no longer currently managed (censored at end of calendar year).15,16

Primary Outcome Variables

The main outcome was time from cohort entry (the day hypertension and currently managed criteria were met) to an initial outpatient electronic medical record entry of an antihypertensive medication prescription, or achieving hypertension control prior to antihypertensive medication initiation. Guidelines for the treatment of hypertension often include lifestyle modification, which can normalize blood pressure without or prior to medication initiation. Results are reported in months.

Explanatory Variables

Patient and provider explanatory variables to identify barriers to hypertension management, including antihypertensive initiation, were selected based on an established conceptual model for clinical inertia.23 Patient-related factors included: sociodemographics (age, sex, marital status, Medicaid use during the baseline or study period, primary spoken language), behavioral risk factors (baseline tobacco use and body mass index at time of meeting hypertension criteria), JNC 7 stage of hypertension (Stage 1: 140-159/90-99 mmHg; Stage 2: ≥ 160/100 mmHg), and comorbidities. Patient comorbidities were assessed at baseline using established algorithms. We identified the presence of hyperlipidemia,24 diabetes mellitus (with/without complications),25 anxiety, and depression.26 Due to low prevalences, we created an indicator variable for the presence of any of the following comorbidities: atrial fibrillation,27 congestive heart failure,24 stroke/transient ischemic attack,27 ischemic heart disease,27 peripheral vascular disease,28 collagen vascular disease,29 deficiency anemias,29 and chronic kidney disease.30

Based on previous studies, patients’ morbidity burden can predict healthcare utilization, which may influence antihypertensive medication initiation.3,4,31 Therefore, we used the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Group (ACG) Case-Mix System (version 10.0), which assesses morbidity burden based on patient age, gender, and patterns of disease in the electronic health record.31 Additional measures of utilization included the number of baseline primary care, specialty, and urgent care visits. Primary care visits were divided into three categories: Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, and a combined category of lower prevalence specialties (Obstetrics/Gynecology, Pediatrics/Adolescent Medicine, Geriatrics).

Patients were assigned to the primary care provider they saw most frequently in outpatient face-to-face Evaluation & Management visits, as reported in professional service claims.18 Models additionally controlled for each provider’s age, specialty (Internal Medicine, Family Medicine/Family Practice, Other), and gender, which were obtained from the provider group’s human resource office and/or the American Medical Association (AMA) 2011 Masterfile data.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata 12.0 (Stata-Corp, College Station, TX). Univariate Kaplan-Meier survival curves32 were computed for age groups (18–39, 40–59, and ≥ 60 years) to evaluate the probability of receiving an initial antihypertensive medication or becoming normotensive prior to medication (meeting the study endpoint) as a function of time since meeting criteria for incident hypertension. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was fitted, and robust estimates of the variance were used to obtain adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for explanatory variables associated with the study end point for a) all age groups and b) young adults (18–39 year-olds). Tests were considered significant at p < 0.05. Explanatory variables statistically significant at p < 0.2 in Pearson correlations33 and based on the established conceptual model for clinical inertia were considered for inclusion in regression models.23 The proportional hazards assumption for each model was tested using a generalized linear regression of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals on functions of time.34 In a sensitivity analysis, regression models were repeated excluding patients with < 6 months follow-up.

RESULTS

Descriptive Data

Overall, 10,022 patients met criteria for analysis (Fig. 1; Table 1). Patients had a mean (standard deviation) of 20 (13) months of follow-up: 18–39 year-olds 19 (13) months, 40–59 year-olds 20 (13) months, and ≥ 60 year-olds 20 (14) months. A total of 1,468 patients (15 %) were censored within the first 36 months of follow-up, due to no longer meeting “currently managed” criteria, pregnancy, or death.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics By Age Group (N = 10,022)

| Total Population N = 10,022 | By Age Group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–39 yrs N = 2,605 (26 %) | 40–59 yrs N = 5,085 (51 %) | ≥ 60 yrs N = 2,332 (23 %) | P value | ||||||

| PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS | |||||||||

| Age, m (SD) | 50 | (14) | 32 | (5.7) | 50 | (5.6) | 69 | (7.8) | < 0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 5,452 | (54) | 1,680 | (64) | 2,769 | (54) | 1,003 | (43) | < 0.001 |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |||||||||

| Single/Divorced/Widowed | 4,013 | (40) | 1,474 | (57) | 1,685 | (33) | 854 | (37) | < 0.001 |

| Married/Partnered | 6,009 | (60) | 1,131 | (43) | 3,400 | (67) | 1,478 | (63) | < 0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||||

| White | 8,820 | (88) | 2,148 | (82) | 4,504 | (89) | 2,168 | (93) | |

| Non-White* | 1,202 | (12) | 457 | (18) | 581 | (11) | 164 | (7.0) | |

| Primary Spoken Language, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| English | 9,059 | (90) | 2,264 | (87) | 4,641 | (91) | 2,154 | (92) | |

| Other | 963 | (9.6) | 341 | (13) | 444 | (8.7) | 178 | (7.6) | |

| Tobacco Use, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Current Tobacco Use | 1,763 | (18) | 601 | (23) | 947 | (19) | 215 | (9.2) | |

| Former Tobacco Use | 2,404 | (24) | 499 | (19) | 1,117 | (22) | 788 | (34) | |

| Never Used Tobacco | 4,303 | (43) | 1,114 | (43) | 2,213 | (44) | 976 | (42) | |

| Unknown/Missing | 1,552 | (15) | 391 | (15) | 808 | (16) | 353 | (15) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, m (SD) | 31 | (7.6) | 33 | (9.0) | 31 | (6.8) | 29 | (6.8) | < 0.001 |

| On Medicaid ever†, n (%) | 896 | (8.9) | 419 | (16) | 419 | (8.2) | 58 | (2.5) | < 0.001 |

| JNC 7 Hypertension Stage‡, n (%) | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Stage 1: 140–159/90–99 mmHg | 7,118 | (71) | 1,896 | (73) | 3,562 | (70) | 1,660 | (71) | |

| Stage 2: ≥160–179/≥100–109 mmHg | 2,904 | (29) | 709 | (27) | 1,523 | (30) | 672 | (29) | |

| Baseline Comorbid Conditions, n (%) | |||||||||

| Anxiety | 1,118 | (11) | 403 | (15) | 552 | (11) | 163 | (7.0) | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 642 | (6.4) | 233 | (8.9) | 305 | (6.0) | 104 | (4.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1,901 | (19) | 204 | (7.8) | 987 | (19) | 710 | (30) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 505 | (5.0) | 70 | (2.7) | 241 | (4.7) | 194 | (8.3) | < 0.001 |

| Low prevalence condition§ | 630 | (6.3) | 43 | (1.7) | 244 | (4.8) | 343 | (15) | < 0.001 |

| ACG‖ Score, young, m (SD) | 1.4 | (1.5) | 0.9 | (0.9) | 1.3 | (1.4) | 1.9 | (1.8) | < 0.001 |

| Baseline Ambulatory Visit Counts, annual, (m, SD) | |||||||||

| Primary Care Visits | 2.1 | (2.0) | 2.2 | (2.2) | 2.1 | (1.9) | 2.1 | (2.0) | 0.005 |

| Specialty Care Visits | 1.7 | (2.4) | 1.5 | (2.1) | 1.6 | (2.3) | 2.2 | (2.8) | < 0.001 |

| Urgent Care Visits | 0.4 | (0.9) | 0.7 | (1.1) | 0.4 | (0.8) | 0.2 | (0.6) | < 0.001 |

| PROVIDER CHARACTERISTICS | |||||||||

| Specialty Providing Majority of Ambulatory Care, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Internal Medicine | 3,522 | (35) | 670 | (26) | 1,755 | (35) | 1,097 | (47) | |

| Family Medicine/Family Practice | 5,178 | (52) | 1,521 | (58) | 2,688 | (53) | 969 | (42) | |

| Other¶ | 1,322 | (13) | 414 | (16) | 642 | (13) | 266 | (11) | |

| Provider Age#, m (SD) | 46 | (11) | 43 | (10) | 46 | (11) | 49 | (11) | < 0.001 |

| Female Provider, n (%) | 4,376 | (44) | 1,141 | (44) | 2,220 | (44) | 1,015 | (44) | 0.50 |

Bold = significant at p <0.05

*Non-White: Black (4.9 %), Hispanic/Latino (1.9 %), Asian (1.6 %), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (0.4 %), American Indian/Alaska Native (0.3 %); Unknown (2.9 %)

†On Medicaid at any point during the baseline or study period

‡JNC 7 Stage of Hypertension = severity of blood pressure elevation at study entry

§Due to low prevalence, an indicator variable was created for the presence of any of the following: atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, stroke/transient ischemic attack, ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, collagen vascular disease, deficiency anemias, or chronic kidney disease

‖ACG = Adjusted Clinical Group Case-Mix Assessment System

¶Other = Pediatrics/Adolescent Medicine, Obstetrics/Gynecology, and Geriatrics

#AMA is the source for the raw physician data (provider ages only); statistics, tables, or tabulations were prepared by User-Customer (M. Smith; PI: H. Johnson) using 2011 AMA Masterfile data

Young adults made up 26 % (n = 2,605) of the sample, and 64 % of young adults were men (Table 1). Compared to adults ≥ 40 years old, young adults had a higher percentage of ethnic minorities and current tobacco users, a greater prevalence of anxiety or depression, and were more likely obese/morbidly obese. Young adults also had more urgent care visits on average than ≥ 40 year-olds, and were more likely to have Family Medicine than Internal Medicine providers.

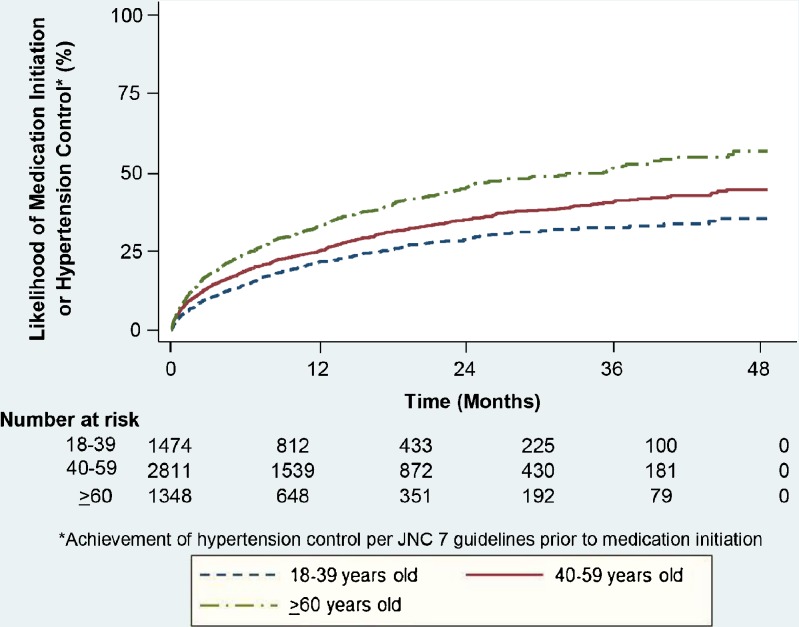

Rates of Antihypertensive Medication Initiation/Hypertension Control

Among the entire population, 4,534 patients either received an antihypertensive medication prescription (n = 4,149) and/or achieved hypertension control prior to medication initiation (n = 385) (Fig. 2). Of the 2,605 young adults, n = 451 received antihypertensive medication and n = 66 achieved hypertension control prior to medication initiation. Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrated that overall, young adults had a slower rate of medication initiation or control than ≥ 40 year-olds (Fig. 2). After meeting criteria for incident hypertension, only 34 % of 18–39 year-olds with hypertension were prescribed antihypertensive medication or achieved control before medication, compared to 44 % (40–59 year-olds) and 56 % (≥ 60 year-olds). The likelihood of achieving the primary outcome increased over time for all age groups (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates: likelihood of antihypertensive medication initiation or hypertension control. *Achievement of hypertension control per JNC 7 guidelines prior to medication initiation.

Predictors of Time to Antihypertensive Medication Initiation/Hypertension Control

Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards models (Table 2) demonstrated that 18–39 year-olds had a significantly slower rate of receiving antihypertensive medication or normalization. After adjusting for patient and provider factors, 18–39 year-olds still had a 44 % slower outcome rate (HR 0.56; 0.47–0.67) and 40–59 year-olds had a 25 % slower rate (HR 0.75; 0.66–0.85) than ≥ 60 year-olds. In addition, patients with Stage 1 hypertension had slower medication initiation rates (HR 0.63; 0.56–0.71).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Hazard Ratios and 95 % CIs of Independent Predictors of Antihypertensive Medication Initiation (All patients aged 18 years and older, N = 10,022)

| Variable | Unadjusted HR (95 % CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95 % CI) | P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PATIENT FACTORS | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| 18–39 years | 0.57 | (0.49–0.65) | < 0.001 | 0.56 | (0.47–0.67) | < 0.001 |

| 40–59 years | 0.73 | (0.65–0.81) | < 0.001 | 0.75 | (0.66–0.85) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 60 years (reference) | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | ─ | ─ | 0.84 | (0.71–1.00) | 0.05 | |

| Non-White† (reference) | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single (reference) | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | |

| Married/Partnered | ─ | ─ | 0.94 | (0.84–1.05) | 0.30 | |

| Primary Spoken Language | ||||||

| English (reference) | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | |

| Other | ─ | ─ | 1.25 | (0.96–1.61) | 0.09 | |

| Tobacco Use | ||||||

| Current Tobacco Use (reference) | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | |

| Former Tobacco Use | ─ | ─ | 0.91 | (0.76–1.08) | 0.29 | |

| Never Used Tobacco | ─ | ─ | 0.87 | (0.74–1.02) | 0.10 | |

| Unknown/Missing | ─ | ─ | 1.32 | (1.10–1.59) | 0.003 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ─ | ─ | 1.014 | (1.006–1.021) | < 0.001 | |

| On Medicaid Ever‡ | ─ | ─ | 1.37 | (1.12–1.67) | 0.002 | |

| JNC 7 Stage of Hypertension§ | ||||||

| Stage 1: 140–159/90–99 mmHg | ─ | ─ | 0.63 | (0.56–0.71) | < 0.001 | |

| Stage 2: ≥ 160/100 mmHg (reference) | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | |

| Baseline Comorbid Conditions | ||||||

| Anxiety | ─ | ─ | 1.17 | (1.00–1.37) | 0.06 | |

| Depression | ─ | ─ | 0.93 | (0.74–1.15) | 0.48 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | ─ | ─ | 1.01 | (0.89–1.15) | 0.84 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | ─ | ─ | 1.44 | (1.18–1.76) | < 0.001 | |

| Low prevalence condition‖ | ─ | ─ | 1.26 | (1.04–1.51) | 0.02 | |

| ACG¶ Risk Score, young index | ─ | ─ | 1.06 | (1.02–1.10) | 0.003 | |

| Baseline Ambulatory Visit Counts, annual mean | ||||||

| Primary Care Visits | ─ | ─ | 1.06 | (1.04–1.09) | < 0.001 | |

| Specialty Care Visits | ─ | ─ | 1.08 | (1.06–1.10) | < 0.001 | |

| PROVIDER FACTORS | ||||||

| Primary Care Specialty | ||||||

| Internal Medicine (reference) | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | |

| Family Medicine/Family Practice | ─ | ─ | 0.95 | (0.84–1.07) | 0.40 | |

| Other# | ─ | ─ | 1.03 | (0.87–1.22) | 0.71 | |

| Provider Age**, years | ─ | ─ | 0.992 | (0.987–0.997) | 0.002 | |

Bold = significant at p <0.05

*Global p value for proportional hazards assumption p = 0.11

†Non-White: Black (4.9 %), Hispanic/Latino (1.9 %), Asian (1.6 %), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (0.4 %), American Indian/Alaska Native (0.3 %); Unknown (2.9 %)

‡On Medicaid at any point during the baseline or study period

§JNC 7 Stage of Hypertension = severity of blood pressure elevation at study entry

‖Due to low prevalence, an indicator variable was created for the presence of any of the following: atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, stroke/transient ischemic attack, ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, collagen vascular disease, deficiency anemia, or chronic kidney disease

¶ACG = Adjusted Clinical Group Case-Mix Assessment System

#Other = Pediatrics/Adolescent Medicine, Obstetrics/Gynecology, and Geriatrics

**AMA is the source for the raw physician data (provider ages only); statistics, tables, or tabulations were prepared by User-Customer (M. Smith; PI: H. Johnson) using 2011 AMA Masterfile data.

Patients with faster rates of medication initiation or normalization had a higher body mass index (HR 1.014; 1.006–1.021), Medicaid (HR 1.37; 1.12–1.67), diabetes (HR 1.44; 1.18–1.76), a lower prevalence condition (HR 1.26; 1.04–1.51), higher ACG scores (HR 1.06; 1.02–1.10), and more primary care (HR 1.06; 1.04–1.09) or specialty clinic (HR 1.08; 1.06–1.10) visits. Among provider factors, patients with a provider of younger age (HR 0.992; 0.987–0.997) had a slower rate of antihypertensive medication initiation. Providers’ specialty and gender were not significant. To test the robustness of our results (Supplementary Appendix, available online), we re-analyzed our model to include only patients with > 6 months follow-up. Our results demonstrated the same predictors as our original model, except for two differences. White race significantly predicted slower medication initiation; this was a trend (p = 0.05) in the original model. Also, the low prevalence variable was not significant compared to the original model. Since the low prevalence variable included conditions such as congestive heart failure, these patients likely received antihypertensive medication earlier in follow-up (< 6 months).

Predictors of Time to Antihypertensive Medication/Hypertension Control (Young Adults)

Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards limited to young adults demonstrated that 18–29 year-olds had a slower rate of antihypertensive medication initiation or normalization (HR 0.83; 0.66-1.04) compared to 30–39 year-olds (Table 3). Even after adjustment, age remained a significant predictor of slower medication initiation.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Hazard Ratios and 95 % CIs of Independent Predictors of Antihypertensive Medication Initiation (Young Adults Aged 18–39 Years Old, N = 2,605)

| Variable | Unadjusted HR (95 % CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95 % CI) | P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PATIENT FACTORS | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| 18-29 years | 0.83 | (0.66–1.04) | 0.10 | 0.77 | (0.60–0.99) | 0.04 |

| 30-39 years (reference) | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | ─ | ─ | 0.63 | (0.49–0.80) | < 0.001 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | ─ | ─ | 0.67 | (0.49–0.90) | 0.009 | |

| Non-White† (reference) | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | |

| Tobacco Use | ||||||

| Current Tobacco Use (reference) | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | |

| Former Tobacco Use | ─ | ─ | 1.09 | (0.78–1.53) | 0.61 | |

| Never Used Tobacco | ─ | ─ | 0.85 | (0.62–1.15) | 0.29 | |

| Unknown/Missing | ─ | ─ | 1.34 | (0.91–1.97) | 0.14 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ─ | ─ | 1.00 | (0.99–1.02) | 0.71 | |

| On Medicaid Ever‡ | ─ | ─ | 1.72 | (1.28–2.30) | < 0.001 | |

| JNC 7 Stage of Hypertension§ | ||||||

| Stage 1: 140–159/90–99 mmHg | ─ | ─ | 0.67 | (0.52–0.88) | 0.004 | |

| Stage 2: ≥ 160/100 mmHg (reference) | ─ | ─ | 1.0 | ─ | ─ | |

| Baseline Comorbid Conditions | ||||||

| Anxiety | ─ | ─ | 1.14 | (0.86–1.52) | 0.36 | |

| Depression | ─ | ─ | 0.97 | (0.67–1.41) | 0.88 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | ─ | ─ | 1.01 | (0.71–1.44) | 0.96 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | ─ | ─ | 1.52 | (0.89–2.60) | 0.12 | |

| ACG‖ Risk Score, young index | ─ | ─ | 1.11 | (1.02–1.22) | 0.02 | |

| Baseline Ambulatory Visit Counts, annual mean | ||||||

| Primary Care Visits | ─ | ─ | 1.07 | (1.02–1.12) | 0.004 | |

| Specialty Care Visits | ─ | ─ | 1.08 | (1.04–1.12) | <0.001 | |

Bold = significant at p <0.05

*Global p value for proportional hazards assumption p = 0.51

†Non-White: Black (8.3 %), Hispanic/Latino (1.8 %), Asian (3.0 %), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (0.84 %), American Indian/Alaska Native (0.5 %); Unknown (3.2 %)

‡On Medicaid at any point during the baseline or study period

§JNC 7 Stage of Hypertension = severity of blood pressure elevation at study entry

‖ACG = Adjusted Clinical Group Case-Mix Assessment System

Cox proportional hazards of only young adults demonstrated slower outcome rates among males (HR 0.63; 0.49–0.80), patients of White race (HR 0.67; 0.49–0.90), and with Stage 1 hypertension (HR 0.67; 0.52–0.88). Young adults with faster rates of medication initiation had Medicaid (HR 1.72; 1.28–2.30), higher ACG scores (HR 1.11; 1.02–1.22), and more primary care (HR 1.07; 1.02–1.12) and specialty clinic (HR 1.08; 1.04–1.12) visits. Provider factors did not predict medication initiation or normalization among young adults. A sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Appendix, available online) re-analyzing predictors among young adults with > 6 months follow-up yielded similar results, except more primary care clinic visits trended towards faster outcomes (p = 0.05), which was previously significant (p = 0.004). This finding likely reflects the loss of patients with close follow-up (within 6 months) after meeting criteria for incident hypertension.

DISCUSSION

These important findings highlight patterns of antihypertensive medication initiation among young adults with regular primary care. During follow-up, despite having elevated blood pressures, only 44 % of young adults were started on antihypertensive medication or achieved control before medication initiation, compared to ≥ 55 % in older adults. Patient age remained a significant predictor of antihypertensive initiation even after adjusting for patient and provider factors.

A 2012 Cochrane Review on pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension highlighted the need for additional research on risks and benefits of antihypertensive medication for primary prevention.35 Although our research focused on young adults, which is considered a lower cardiovascular risk group, the majority of our young adults were obese and approximately 20 % currently used tobacco. These additional risk factors with continued elevated blood pressures increase the long-term risk for cardiovascular events among young adults.36

Although the majority of young adults were male in our study, males had a 36 % slower rate of antihypertensive medication initiation compared to females. Consistent with previous research, males were less likely to be on antihypertensive medication,4 and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data confirmed that across ethnicities, females are more likely than males to be treated for hypertension.2

Among young adults in our study, White patients were less likely to receive antihypertensive medication. Our findings differed from NHANES (2007–2010) data, which did not demonstrate a significant overall difference between non-Hispanic Whites (75.8 %) and non-Hispanic Blacks (75.6 %) for antihypertensive treatment.2 A possible explanation for our findings is that primary care providers may be responding to the known increased risk of comorbidities with hypertension among minorities, especially African-Americans.2 Interventions are needed to improve hypertension treatment equally among ethnicities and genders.

There was not a significant difference in predictors of antihypertensive medication initiation between young adults and the overall population. Younger ages continued to have slower rates of antihypertensive medication initiation for the duration of follow-up after adjusting for patient and provider factors. However, it should be stressed that medication initiation and hypertension control were suboptimal in the middle and older age groups, supporting multiple prior studies.1,9,23 In both models, patients with more primary care or specialty visits were more likely to be initiated on medication. These findings are supported by studies in older age groups4,37 and highlight the importance of timely clinic follow-up for hypertension management. Although provider factors were not significant among young adults, younger providers were less likely to prescribe antihypertensive medication in the overall population. Previous studies from Spain38 and Italy39 demonstrated that practitioners ≥ 50 years old had longer mean hypertension diagnosis times and increased rates of uncontrolled hypertension among older patients (mean 64–66 years old). Our study differences may represent variations in patient populations. To further investigate young adults, we will conduct primary care provider interviews to evaluate hypertension practice patterns among young adults compared to older adults with providers of various ages, experience levels, and practice settings.

Patients with diabetes had a 56 % faster rate of medication initiation/hypertension control across all ages. In previous research, adults with concordant conditions had a higher prevalence of antihypertensive therapy.4,40 In addition, the 2013 American Diabetes Association Guidelines recommend that a lower systolic target (< 130 mmHg) be considered in younger patients.41 The presence of Medicaid significantly predicted a faster treatment rate. This may reflect our study’s restriction to patients with a usual source of care. In previous research, absence of a usual source of care resulted in lower hypertension treatment rates.42 However, even with a usual source of care, this study demonstrated suboptimal hypertension treatment, underlining the need for healthcare system interventions. To improve young adult hypertension control, interventions need to address both bio-behavioral risk factors for hypertension (body mass index, exercise, tobacco use) and antihypertensive medication initiation.43

The primary strength of this study was the ability to analyze young adults that received regular primary care in a large multispecialty group practice. One limitation is the use of data from a single healthcare system; treatment patterns may differ among other systems and geographic regions. However, this healthcare system is one of the ten largest physician practices in the United States, including over 300 primary care physicians, and 43 primary care clinics in both urban and rural settings, and is owned and operated by various entities including a hospital, a multi-specialty physician group, and an academic center. We were not able to analyze practice type (academic/non-academic) or setting (rural/urban); however, the inclusion of patient demographic, comorbidity, and utilization data with provider data improves the generalizability and clinical applicability of our data. Another limitation is the use of administrative data, which raises the potential for misclassification of a hypertension diagnosis and other comorbidities; however, previously established and published algorithms were utilized to help address this concern. Only 4.5 % of patients achieved blood pressure control before antihypertensive medication initiation, so this study met its goal of generally identifying patients with consistently elevated blood pressures. Additionally, findings were robust to the inclusion of patients who achieved control before medication initiation. In this study, we were unable to identify lifestyle counseling, which is a cornerstone of hypertension management, especially for young adults. Yet importantly, this study demonstrated how few patients were able to achieve control without medication.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of young adults with incident hypertension and regular primary care had untreated and uncontrolled hypertension. Young adults with Stage 1 hypertension, male gender, and White race/ethnicity were least likely to receive antihypertensive medication or achieve hypertension control. Healthcare system interventions are necessary to improve hypertension management in young adults.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 63 kb)

Acknowledgements

Contributors

The authors gratefully acknowledge Katie Ronk, BS, for data preparation, and Jamie LaMantia, BS, and Colleen Brown, BA, for manuscript preparation.

Funders

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) under award number UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health under award number U54TR000021. Heather Johnson is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23HL112907, and also by the University of Wisconsin Centennial Scholars Program of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Christie Bartels is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23AR062381. Nancy Pandhi is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number K08AG029527. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Additional funding for this project was provided by the University of Wisconsin Health Innovation Program and the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health from The Wisconsin Partnership Program.

Prior Presentations

Some of the findings reported in the manuscript were presented in abstract form at the 2013 American Heart Association Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Scientific Sessions on 16 May 2013.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital signs: prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension—United States, 1999–2002 and 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell NR, So L, Amankwah E, Quan H, Maxwell C. Characteristics of hypertensive Canadians not receiving drug therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24:485–490. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(08)70623-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarron P, Smith GD, Okasha M, McEwen J. Blood pressure in young adulthood and mortality from cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2000;355:1430–1431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey KR, Grossardt BR, Graves JW. Novel use of Kaplan-Meier methods to explain age and gender differences in hypertension control rates. Hypertension. 2008;51:841–847. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong SH, Wang J, Tak S. A patient-centric goal in time to blood pressure control from drug therapy initiation. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6:7–12. doi: 10.1111/cts.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogedegbe G. Barriers to optimal hypertension control. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10:644–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.08329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khanna RR, Victor RG, Bibbins-Domingo K, Shapiro MF, Pletcher MJ. Missed opportunities for treatment of uncontrolled hypertension at physician office visits in the United States, 2005 through 2009. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1344–1345. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen QC, Waddell EN, Thomas JC, Huston SL, Kerker BD, Gwynn RC. Awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia among insured residents of New York City, 2004. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN. Self-reported hypertension treatment practices among primary care physicians: blood pressure thresholds, drug choices, and the role of guidelines and evidence-based medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2281–2286. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.15.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill MN, Bone LR, Kim MT, Miller DJ, Dennison CR, Levine DM. Barriers to hypertension care and control in young urban black men. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:951–958. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(99)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huebschmann AG, Mizrahi T, Soenksen A, Beaty BL, Denberg TD. Reducing clinical inertia in hypertension treatment: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14:322–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatahet MA, Bowhan J, Clough EA. Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (WCHQ): lessons learned. WMJ. 2004;103:45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheehy A, Pandhi N, Coursin DB, et al. Minority status and diabetes screening in an ambulatory population. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1289–1294. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WCHQ. Wisconsin Collaborative for Health Care Quality. Available at: http://www.wchq.org/. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- 18.Thorpe CT, Flood GE, Kraft SA, Everett CM, Smith MA. Effect of patient selection method on provider group performance estimates. Med Care. 2011;49:780–785. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821b3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers MG, Tobe SW, McKay DW, Bolli P, Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA. New algorithm for the diagnosis of hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1369–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmittdiel J, Selby JV, Swain B, et al. Missed opportunities in cardiovascular disease prevention?: low rates of hypertension recognition for women at medicine and obstetrics-gynecology clinics. Hypertension. 2011;57:717–722. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen ZL, Cauch-Dudek KJ, McAlister FA. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Med. 2007;1:e18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manson JM, McFarland B, Weiss S. Use of an automated database to evaluate markers for early detection of pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:180–187. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor PJ, Sperl-Hillen JM, Johnson PE, Rush WA, Blitz G. Clinical Inertia and Outpatient Medical Errors. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, Lewin DI, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 2: Concepts and Methodology) Rockville, MD: Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2005. pp. 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borzecki AM, Wong AT, Hickey EC, Ash AS, Berlowitz DR. Identifying hypertension-related comorbidities from administrative data: what's the optimal approach? Am J Med Qual. 2004;19:201–206. doi: 10.1177/106286060401900504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hebert PL, Geiss LS, Tierney EF, Engelgau MM, Yawn BP, McBean AM. Identifying persons with diabetes using Medicare claims data. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:270–277. doi: 10.1177/106286069901400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marciniak MD, Lage MJ, Dunayevich E, et al. The cost of treating anxiety: the medical and demographic correlates that impact total medical costs. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:178–184. doi: 10.1002/da.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. 2011 Chronic Condition Reference List. Available at: http://www.ccwdata.org/cs/groups/public/documents/document/ccw_conditionreferencelist2011.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- 28.Newton KM, Wagner EH, Ramsey SD, et al. The use of automated data to identify complications and comorbidities of diabetes: a validation study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:199–207. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foley RN, Murray AM, Li S, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risk for cardiovascular disease, renal replacement, and death in the United States Medicare population, 1998 to 1999. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:489–495. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004030203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Starfield B, Weiner J, Mumford L, Steinwachs D. Ambulatory care groups: a categorization of diagnoses for research and management. Health Serv Res. 1991;26:53–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.StataCorp. STATA Survival Analysis and Epidemiological Tables Reference Manual: Release 12. Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011.

- 33.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:125–137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diao D, Wright JM, Cundiff DK, Gueyffier F. Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD006742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Saydah S, Bullard KM, Imperatore G, Geiss L, Gregg EW. Cardiometabolic risk factors among US adolescents and young adults and risk of early mortality. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e679–e686. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jolles EP, Clark AM, Braam B. Getting the message across: opportunities and obstacles in effective communication in hypertension care. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1500–1510. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835476e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Burgos-Lunar C, Del Cura-Gonzalez I, Salinero-Fort MA, Gomez-Campelo P, Perez de Isla L, Jimenez-Garcia R. Delayed diagnosis of hypertension in diabetic patients monitored in primary care. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66:700–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Degli Esposti E, Di Martino M, Sturani A, et al. Risk factors for uncontrolled hypertension in Italy. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:207–213. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:725–731. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S11–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Spatz ES, Ross JS, Desai MM, Canavan ME, Krumholz HM. Beyond insurance coverage: usual source of care in the treatment of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. Data from the 2003–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am Heart J. 2010;160:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Siegler IC, et al. Systolic blood pressure, socioeconomic status, and biobehavioral risk factors in a nationally representative US young adult sample. Hypertension. 2011;58:161–166. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.171272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 63 kb)