Abstract

Some species of mushrooms in the genus Amanita are extremely poisonous and frequently fatal to mammals including humans and dogs. Their extreme toxicity is due to amatoxins such as α- and β-amanitin. Amanita mushrooms also biosynthesize a chemically related group of toxins, the phallotoxins, such as phalloidin. The amatoxins and phallotoxins (collectively known as the Amanita toxins) are bicyclic octa- and heptapeptides, respectively. Both contain an unusual Trp-Cys cross-bridge known as tryptathionine. We have shown that, in Amanita bisporigera, the amatoxins and phallotoxins are synthesized as proproteins on ribosomes and not by nonribosomal peptide synthetases. The proproteins are 34–35 amino acids in length and have no predicted signal peptides. The genes for α-amanitin (AMA1) and phallacidin (PHA1) are members of a large family of related genes, characterized by highly conserved amino acid sequences flanking a hypervariable “toxin” region. The toxin regions are flanked by invariant proline (Pro) residues. An enzyme that could cleave the proprotein of phalloidin was purified from the phalloidin-producing lawn mushroom Conocybe apala. The enzyme is a serine protease in the prolyl oligopeptidase (POP) subfamily. The same enzyme cuts at both Pro residues to release the linear hepta- or octapeptide.

Keywords: amanitin, phalloidin, phallacidin, prolyl oligopeptidase, Conocybe, Amanita

INTRODUCTION

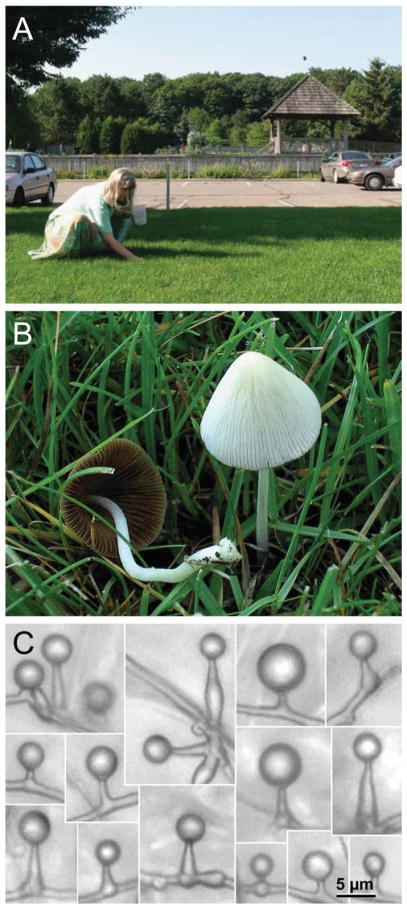

Certain species in the genus Amanita account for more than 90% of the fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. Amatoxins such as α-amanitin (Figure 1A) are the poisonous compounds in species of Amanita sect, Phalloideae. The human LD50 for α-amanitin is ~0.1 mg/kg, and one mushroom can contain a fatal dose of 10–12 mg.1 There are several forms of amatoxins, which differ in their pattern of hydroxylation and/or containing Asn instead of Asp. Amatoxins are also made by several species of mushroom in other unrelated genera.

FIGURE 1.

A: Structure of α-amanitin (an amatoxin). B: Structure of phallacidin (a phallotoxin). All amino acids have the L configuration except D-hydroxyAsp in phallacidin (D-Thr in phalloidin).

Amatoxins survive the human digestive tract and enter liver cells, where they inhibit RNA polymerase II.2 Without prompt intervention, amatoxins cause irreversible liver failure and death in 3–7 days. Liver transplants are often the only treatment option if more than 48 h has elapsed since ingestion.

Species of Amanita that make amatoxins also make a related family of cyclic peptides known as phallotoxins, such as phalloidin and phallacidin (Figure 1B). Phallotoxins are also made by Conocybe apala (= C. albipes or C. lactea).3 The phallotoxins contain seven instead of eight amino acids, a sulfide (thioether) instead of a sulfoxide in the cross-bridge between Trp and Cys, and one amino acid with the D configuration. Phallotoxins are toxic to mammals if injected but are not absorbed by the digestive tract.1 Phallotoxins stabilize F-actin, and fluorescent conjugates of phalloidin are commonly used to study the actin cytoskeleton.

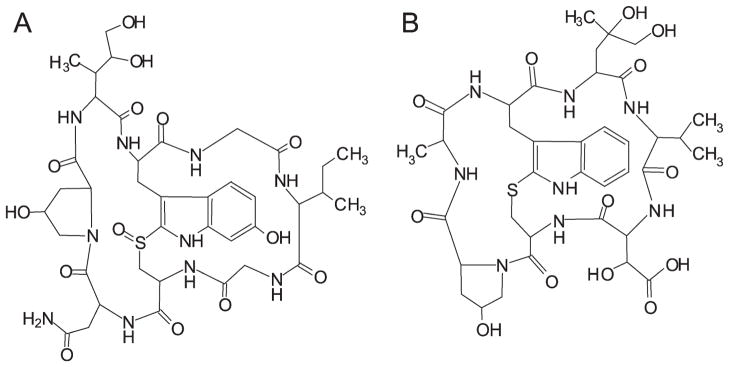

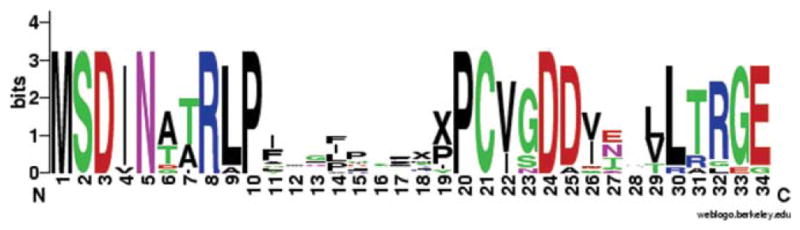

We recently showed that the amatoxins and phallotoxins are biosynthesized on ribosomes, and not, like all other known fungal cyclic peptides, by nonribosomal peptide synthetases.4 The genes were discovered by genomic survey sequencing using 454 pyrosequencing of Amanita bisporigera, the “destroying angel” mushroom (see Figure 2). In addition to AMA1 (for α-amanitin) and PHA1 (for phallacidin), the genome of A. bisporigera contains a large family of related genes, which we call the MSDIN family. In all members of this family, the proproteins are ~34–39 amino acids in length and lack predicted signal peptides. The regions of these proproteins that contain the amino acid sequences found in the mature toxins are 6–10 amino acids in length and are hypervariable compared to the surrounding amino acid sequences (see Figure 3). These compounds are among the smallest known ribosomally synthesized cyclic peptides. In all family members, a proline (Pro) residue is always the immediate upstream amino acid and also the last amino acid in the predicted hypervariable regions. All known amatoxins and phallotoxins and all predicted MSDIN peptides contain at least one Pro residue, but only the amatoxins and phallotoxins contain Trp and Cys, and so only these subfamily members can form tryptathionine. Several monocyclic hexa-and decapeptides have been isolated from A. phalloides.1 All 20 proteinogenic amino acids have been found at least once in one of the MSDIN family members of A. bisporigera. We have also used PCR to amplify members of the MSDIN family from A. phalloides (the death cap mushroom) and A. ocreata.4

FIGURE 2.

Amanita bisporigera collected in Michigan in 2009. This deadly white mushroom, known as the “destroying angel,” is a native of North America and biosynthesizes amatoxins and phallotoxins.

FIGURE 3.

WebLogo alignment of 15 members of the “MSDIN” family (named for the first five highly conserved amino acids). The height of the amino acid at each position represents its degree of conservation. The MSDIN family encodes the amatoxins and phallotoxins and is also predicted to encode a variety of unknown peptides within the hypervariable central region (amino acids 11–20), which is 6–10 amino acids in length (Xs have been inserted in the hypervariable regions of less than 10 amino acids to emphasize the conservation of the carboxy terminus of the MSDIN peptides). As defined here, the “hypervariable” region includes the carboxy-terminal Pro, which is completely conserved in the MSDIN family as well as being a constituent of the mature toxins. Based on cDNA sequences, the M (Met) of MSDIN is the translational start codon. Amino acids 35–39 are not shown, because there is an intron (experimentally established for AMA1 and PHA1; deduced for the others) that interrupts the third to the last codon (Originally published in Luo et al. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 18070–18077. © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.).

PROCESSING OF THE AMANITA TOXINS

Following translation, subsequent necessary steps in Amanita toxin biosynthesis include proteolytic excision, cyclization, hydroxylation, Trp-Cys (tryptathionine) cross-linking, and, in the case of the phallotoxins, epimerization of one amino acid. These steps do not necessarily occur in that order. Amanita toxin biosynthesis might also require genes encoding proteins for export and regulation, as is often seen for other fungal secondary metabolites (e.g., Ref. 5). Cyclization might occur before or after tryptathionine biosynthesis.

It is currently difficult to address the biochemistry of the post-translational processing steps, because the uniqueness of the Amanita system means that other ribosomal peptide biosynthetic systems, such as cyclotides or patellamides, cannot serve as precedents. Also, the complete genome of any toxin-producing, Amanita species is not available.

A common feature of fungal secondary metabolites, at least in ascomycetes and some basidiomycetes, is clustering of the genes in the pathway. It is important to note that eukaryotic gene clustering is quite distinct from the clustering found in bacterial operons; although both types comprise 3–15 genes each separated by 0.2–2 kb, in eukaryotic clusters each gene has its own promoter, that is, there are no polycistronic mRNAs. Typical fungal secondary metabolite gene clusters contain biosynthetic genes, genes for transporters (metabolite efflux carriers or pumps), and pathway-specific transcription factors that positively regulate the other genes of the cluster.5–7 Preliminary evidence suggests that some of the MSDIN genes are clustered with some potential biosynthetic genes (unpublished results), but our genome survey sequence data of A. bisporigera are still too incomplete to draw any solid conclusions.

PROTEOLYTIC CLEAVAGE OF THE PROPROTEIN

As noted earlier, the hypervariable regions of the MSDIN family have invariant flanking Pro residues (see Figure 3). Consideration of the known Pro-specific peptidases8 suggested that a prolyl oligopeptidase (POP) catalyzes the initial biosynthetic step. POPs are widespread in animals, plants, bacteria, and fungi (except, strangely, ascomycetes) and cleave at internal Pro residues of small proteins (<35 amino acid). A. bisporigera has two POP genes, one of which is found only in Amanita sect. Phalloidae (Ref. 4 and unpublished observations). Other fully sequenced (toxin nonpro-ducing) fungi including Coprinus cinerea, Phanerochaete chrysosporium, and Laccaria bicolor appear to each have a single POP gene.

To determine the enzyme that was responsible for the proteolytic processing of the Amanita toxins, it was purified from mushroom extracts. Amanita species themselves are transient in availability (they cannot be cultured in the laboratory) and therefore we used Conocybe apala as the starting material, a mushroom which grows abundantly in well-watered lawns of the Michigan State University campus (see Figure 4). It is possible to collect kilogram quantities of C. apala in a few days. The mushrooms continue to emerge daily throughout the summer. C. apala makes phalloidin (but not amanitin)3 and therefore must contain the enzyme (or enzymes) that cleave the phalloidin proprotein.

FIGURE 4.

A: Collecting Conocybe apala (formerly C. lactea or C. albipes) from watered lawns on the campus of Michigan State University. B: C. apala. The mushrooms are ~8 cm tall. C: High magnification of secretory cells with attached liquid droplets from a culture of C. apala established in our laboratory. The droplets are not membrane-bound and are easily washed off. For more pictures of C. apala secretory cells, see http://www.uoguelph.ca/~gbarron/2008/conocybe.htm and Ref. 9.

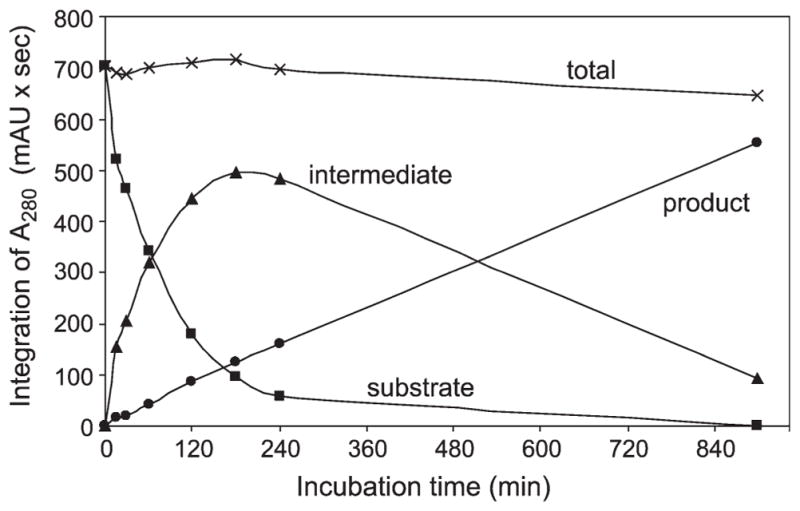

Using standard protein purification methods, we identified an enzyme from C. albipes that cleaves a synthetic phalloidin peptide.10 During the early stages of purification, it became apparent that the cleavage enzyme was copurifying with activity against the POP substrate Z-Gly-Pro-pNA and was inhibited by the specific POP inhibitor Z-Pro-Prolinal. The cleavage enzyme was purified to homogeneity and subjected to mass spectrometric peptide analysis. Combined with the full amino acid sequence deduced from a cDNA, we identified the protein as a member of the POP family of serine proteases.9 The pure enzyme cuts at both Pro residues in the synthetic phalloidin peptide to release the mature linear peptide, preferentially cutting at the Pro closer to the carboxy terminus before cutting at the Pro closer to the amino terminus (see Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Time course of cleavage of a synthetic phalloidin precursor (substrate: MSDINATRLPAWLATCPCAGDD). Purified POP from C. apala was incubated with the substrate for the indicated times. Products were separated by HPLC and quantitated by their absorbance at 280 nm. The intermediate was identified as MSDI-NATRLPAWLATCP and the product as AWLATCP by mass spectrometry. No evidence for a carboxy-terminal intermediate (AWLATCPCAGDD) was found. Dithiothreitol was included in the enzyme buffer to prevent oxidation of the two Cys residues (Originally published in Luo et al. J Biol Chem 2009, 284:18070–18077. © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology).

In regard to the mechanism of cyclization of the Amanita toxins, there are some potentially relevant precedents presented in other works in this volume. As shown elsewhere in this volume, trypsin and other proteases are capable of making as well as breaking peptide bonds.11,12 It is very likely that a protease or proteaselike enzyme catalyzes the cyclization of the Amanita toxins. However, to date, no chromatographic or mass spectrometric evidence was obtained for any cyclized product during incubation of toxin precursors with POP, and therefore cyclization is probably not catalyzed by POP. In regard to the sequence of processing steps, cyclication might occur after formation of the Trp-Cys crossbridge (tryptathionine), because this would facilitate cyclization by bringing the N and C termini of the nascent peptide closer together.

HISTOLOGY OF TOXIN BIOSYNTHESIS

Mushrooms are multicellular organisms with many specialized cell types. There are many examples of mushroom toxins and many examples of chemically specialized cell types in mushrooms.13 However, in only a few cases, is there any direct evidence connecting the two, that is, a specific cell type with a specific metabolite. Do the cell types that show differential staining or morphology (consistent with a metabolic specialization of some sort) serve as the sites of toxin biosynthesis and/or storage?14 Two examples of specialized cell types in toxic mushrooms are shown in Figure 6. The cystidia of a poisonous Inocybe species are large and appear to be free of cytoplasm and could be the site of storage of the toxic compounds produced by this mushroom (Figure 6A). The mushroom Russula bella has a specialized cell type that contains unknown metabolites toxic to insects15 (Figure 6B). Such specialized cell types could be sites of biosynthesis and/ or storage sites. C. apala, which makes phallotoxins and from which we purified POP, also has specialized cells that appear to be sites of biosynthesis and/or accumulation of specialized secondary metabolites. These structures could contain phalloidin, but to the best of our knowledge, this has not been addressed experimentally9 (Figure 4C).

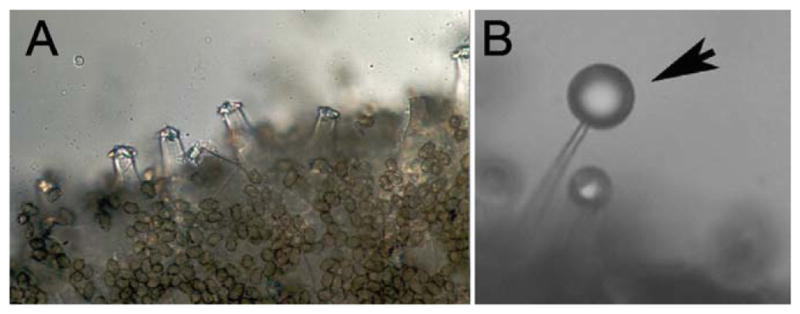

FIGURE 6.

Examples of anatomically and biochemically specialized cells in mushrooms. A: “Inocybe sp. involved in a fatal poisoning case of a young dog. The encrusted cystidia stand up on the gill edges.” The abundant brown circles are basidiospores (http://www.flickr.com/photos/cornellfungi/2829688392/). B: Cystidia of Russula. These contain unknown insecticidal compound(s). The droplets (arrow) are not membrane bound and the contents adhere to glass. The droplet is is ~10 μm in diameter (from Ref. 15; reprinted with permission).

AMANITA TOXIN BIOSYNTHESIS IN CONTEXT

Small, modified, ribosomally synthesized, and biologically active peptides have been identified from many eukaryotic and prokaryotic sources, including bacteria, spiders, snakes, cone snails, plants, and amphibian skin.16–20 Like the Amanita toxins, these peptides are synthesized as precursor proteins and often undergo post-translational modifications similar to those of the Amanita toxins, such as cyclization, hydroxylation, and epimerization.

The cone snail toxins (conotoxins) are 12–40 amino acids. Like the Amanita toxins, the cone snail toxins exist as gene families, the members of which have hypervariable regions (corresponding to the amino acids present in the mature toxins) and conserved regions found in all members.18 Conotoxins and Amanita toxins differ in several key respects. First, the Amanita toxins are smaller (7–10 amino acids vs. 12–40 for the conotoxins).21 Second, the mature conotoxins are at the carboxy termini of the preproproteins and are predicted to be cleaved by a protease that cuts at basic amino acids (Arg or Lys). In contrast, the mature Amanita toxin sequences are internal to the proprotein and are predicted to require two cleavages by one or more Pro-specific peptidases. Third, the conotoxins are “cyclized” not by true head-to-tail peptide bonds but rather by multiple disulfide bonds, and the Amanita toxins do not have disulfide bonds. Therefore, we do not predict the involvement of a protein disulfide isomerase as has been found for cone snail toxins and cyclotides.21,22 However, it is not impossible that the formation of the Trp-Cys bond in Amanita toxins is catalyzed by an unusual disulfide isomerase. Fourth, the conotoxin preproproteins have signal peptides to direct secretion of the proprotein into the venom duct, whereas the Amanita toxins are not secreted23 and their proproteins lack predicted signal peptides.

Cyclotides such as kalata B1 are 28–37 amino acids in size.16,20 The precursor structure contains an N-terminal signal peptide followed by a proprotein region and a conserved “N-terminal repeat region” containing a highly conserved domain of ~20 amino acids, one to three cyclotide domains, and a short C-terminal sequence. An Asn-endopeptidase is responsible for removing the C-terminal peptide from the proprotein and cyclizing the peptide,24 but the protease that cuts the N-terminus is apparently not known. The mature cyclotides are true head-to-tail cyclic peptides but are also held in rigid conformations by multiple disulfide bonds. The cyclotides and the Amanita toxins are both eukaryotic in origin, but differ in size, gene organization, and method of processing, and by the absence of disulfide bonds in the Amanita toxins.

In the recent years, a number of ribosomally encoded cyclic peptide secondary metabolites have been described from prokaryotes.19 These include lantibiotics, thiocillins, thiomuracins, microcins, microcyclamides, and cyanobactins, such as patellamides, streptolysin, and tricyclic depsi-peptides. Bacterial autoinducing peptides (AIPs), which are 7–9 amino acids, mediate quorum sensing by certain human pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria.25 AIPs are posttranslationally cyclized by the formation of a thiolactone between the carboxyl group of the C-terminal amino acid and an internal Cys. AIP proproteins are processed at the C-terminus by agrB with simultaneous condensation to form the thiolac-tone ring.25

Lantibiotics such as nisin, subtilin, and cinnamycin, are produced by species of Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and other bacteria. They contain 19–38 amino acids and are characterized by the presence of lanthionine, which is formed biosynthetically by dehydration of an Ala residue followed by intra-molecular addition of Cys.26 The lantibiotics are similar to the Amanita toxins in containing a modified, cross-linked Cys residue. However, the Cys in the Amanita toxins is cross-linked to a Trp residue instead of Ala as in the case of the lantibiotics. Microcin J25 is a 21-amino acid peptide cyclized between an N-terminal Gly or Cys residue and an internal Glu or Asp residue. It is produced by E. coli; other enterobacteria produce related peptides. Processing of the primary translation product (58 amino acids) involves cleavage of a 37-residue leader peptide and cyclization. The maturation reaction requires ATP for amide bond formation.27 There are no orthologs of mcjA or mcjB in any available fungal genome, including A. bisporigera.

Patellamides and other cyanobactins are produced by cyanobacterial symbionts of marine ascidians.19,28,29 Like the Amanita toxins, cyanobactins are small (eight amino acids) and are cleaved internally from their proproteins. Unlike the Amanita toxins, the primary translation products of the cyanobactin contain two toxin “cassettes,” each of which gives rise to an individual cyanobactin.28 The cyanobactins are post-translationally modified differently from the Amanita toxins, in particular, by heterocyclization. The patellamides are cleaved from their proproteins by a subtilisinlike protease (PatA) and cyclized by PatG.30 PatA recognizes flanking conserved amino acids, but cleavage occurs at a Ser residue instead of Pro as in the case of the Amanita toxins. The amino acids that are conserved up and downstream of the hypervariable toxin region in the MSDIN family (see Figure 3) might also serve as a recognition sequence for cleavage by POP. PatA makes both cuts of the patellamides, like POP in the Amanita system.10 However, compared to the action of POP on a phalloidin precursor, the activity of PatA is very slow.30 Cyclization of patellamides does not require an additional source of energy; it is apparently driven by coupling with the proteolytic reaction.30 Searching of all sequenced fungi, including A. bisporigera, have failed to find any ortho-logs of PatA or PatG (or any of the other genes of the patellamide cluster), and so the mechanism of cyclization of the Amanita toxins is apparently different from the case of the cyanobactins.

Acknowledgments

We thank the organizers and other participants of the First International Congress on Circular Proteins for the invitation to present this work and for many stimulating discussions.

Contract grant sponsor: Michigan State University Plant Research Laboratory, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, U.S. Department of Energy

Contract grant number: DE-FG02-91ER20021

References

- 1.Wieland T. Peptides of Poisonous Amanita Mushrooms. Springer; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bushnell DA, Cramer P, Kornberg RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1218–1222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251664698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallen HE, Watling R, Adams GC. Mycol Res. 2003;107:969–979. doi: 10.1017/s0953756203008190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallen HE, Luo H, Scott-Craig JS, Walton JD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19097–19101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707340104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wight W, Kim KH, Lawrence CB, Walton JD. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2009;22:1258–1267. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-10-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedley KF, Walton JD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14174–14179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231491298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walton JD. Fung Genet Biol. 2000;30:167–171. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2000.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham DF, O’Connor B. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1343:160–186. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchison LH, Mazdia SE, Barron GL. Can J Bot. 1996;74:431–434. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo H1, Hallen-Adams HE, Walton JD. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18070–18077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conlan BF, Gillon AD, Craik DJ, Anderson MA. Biopolym Pept Sci. 2010;94:573–583. doi: 10.1002/bip.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colgrave ML, Korsinczky MJL, Clark R, Foley F, Craik DJ. Biopolym Pept Sci. 2010;94:665–672. doi: 10.1002/bip.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemencon H, Emmett V, Emmett H. Cytology and Plectology of the Hymenomycetes. J. Cramer; Berlin: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truong BN, Okazaki K, Fukiharu T, Takeuchi T, Futai K, Le XT, Suzuki A. Mycoscience. 2007;48:222–230. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamori T, Suzuki A. Mycol Res. 2007;111:1345–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craik DJ, Cemazar M, Daly NL. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2007;10:176–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escoubas P. Mol Divers. 2006;10:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s11030-006-9050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olivera BM. J Biol Chem. 2006;28:31173–31177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McIntosh JA, Donia MS, Schmidt EW. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:537–559. doi: 10.1039/b714132g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trabi M, Craik DJ. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:132–138. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bulaj G, Buczek O, Goodsell I, Jimenez EC, Kranski J, Nielsen JS, Garrett JE, Garrett BM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(Suppl 2):14562–14568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335845100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruber CW, Cemazar M, Clark RJ, Horibe T, Renda RF, Anderson MA, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20435–20446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang P, Chen Z, Hu J, Ei B, Zhang Z, Hu W. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;252:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saska I, Gillon AD, Hatsugai N, Dietzgen RG, Hara-Nishimura I, Anderson MA, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29721–29728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novick RP, Geisinger E. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:541–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willey JM, van der Donk WA. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:477–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duquesne S, Destoumeiux-Garzon D, Zirah S, Goulard C, Peduzzi J, Rebuffat S. Chem Biol. 2007;14:793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donia MS, Ravel J, Schmidt EW. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:341–343. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt EW, Nelson JT, Rasko DA, Sudek S, Eisen JA, Haygood MG, Ravel J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7315–7320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501424102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J, McIntosh J, Hathway BJ, Schmidt EW. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2122–2124. doi: 10.1021/ja8092168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]