Abstract

Human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) research has grown exponentially in the last decade. The ability to process and preserve these cells is vital to their use in stem cell therapy. As such, understanding the complex, molecular-based stress responses associated with biopreservation is necessary to improve outcomes and maintain the unique stem cell properties specific to hMSC. In this study hMSC were exposed to cold storage (4°C) for varying intervals in three different media. The addition of resveratrol or salubrinal was studied to determine if either could improve cell tolerance to cold. A rapid elevation in apoptosis at 1 hour post-storage as well as increased levels of necrosis through the 24 hours of recovery was noted in samples. The addition of resveratrol resulted in significant improvements to hMSC survival while the addition of salubrinal revealed a differential response based on the media utilized. Decreases in both apoptosis and necrosis together with decreased cell stress/death signaling protein levels were observed following modulation. Further, ER stress and subsequent Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) stress pathway activation was implicated in response to hMSC hypothermic storage. This study is an important first step in understanding hMSC stress responses to cold exposure and demonstrates the impact of targeted molecular modulation of specific stress pathways on cold tolerance thereby yielding improved outcomes. Continued research is necessary to further elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in hypothermic-induced hMSC cell death. This study has demonstrated the potential for improving hMSC processing and storage through targeting select cell stress pathways.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Necrosis, Mesenchymal Stem Cell, ER Stress, Unfolded Protein Response, Hypothermic Storage, Resveratrol, Salubrinal

Introduction

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC) are important progenitor cells with the multipotent potential to differentiate into a number of different cell types including osteoblasts, adipocytes, myocytes and chondrocytes. As such, they hold significant importance and potential for both in vivo and in vitro uses as regenerative therapies for damaged or diseased tissues and organs[7,16]. Further, continued research has demonstrated additional roles as regulators of immune response, cancer proliferation and tissue repair through paracrine dependent mechanisms[8,17,26,37,47,48]. This capacity for both direct and indirect modes of action has resulted in further complexity and difficulty in understanding how hMSC function within the body and in turn the use of hMSC for therapeutic applications. Another limiting factor in their use is the ability to process and biobank these cells while maintaining viability and functionality.

Numerous studies have now established that bioprocessing techniques are associated with the activation of molecular-based stress responses which contribute to cell loss during and following processing leading to failure[3,4,5,6,12,13,15,30,35]. These molecular responses can manifest as apoptosis or programmed cell death signaling. Classically, there are two types of cell death associated with preservation failure, apoptosis and necrosis, with necrosis defined as death from external causation distinguishing it from the programmed characteristics of apoptosis. Several studies, however, have demonstrated a molecular component to a portion of necrotic cell death as well[10,20,45], supporting the hypothesis of a cell death continuum in which dying cells can exhibit traits of both apoptosis and necrosis. Further, other studies have demonstrated the ability of cells to switch between the two types of cell death linked to the availability of ATP[24,31]. Understanding and mitigating these molecular stress responses is critical for improving biopreservation outcomes, particularly in cell systems that are highly sensitive to thermal changes such as hMSC.

Limited research has been conducted examining hMSC response to hypothermic exposure. To this end this study was conducted in an effort to begin to characterize the effect that exposure to hypothermic conditions has on hMSC stress response signaling and the role of cell stress pathway activation in biobanking failure. A hypothermic storage regime was utilized to examine how cold stress affected the type and timing of cell death in hMSC. A number of different media were also utilized to examine solution formulation influences. The incorporation of the chemical modulators resveratrol and salubrinal was included in an effort to examine the effect of molecular modulation on cell tolerance to hypothermic stress and thereby overall cell survival.

Resveratrol is a compound that has been widely researched in the last decade as reports have implicated a number of different properties from life extension to anti-tumor effects[18,22,23,36,38,40,42]. Reports specifically examining resveratrol addition to cold exposed cells have demonstrated differential and potentially cancer specific effects[11,14]. Additionally, a recent report investigated the effect of exposure to different concentrations of resveratrol on hMSC self-renewal and differentiation[33]. Results from this study suggest that depending on the concentration and duration of resveratrol exposure a positive or inhibitory effect on hMSC self-renewal capacity could be obtained. Given the contradictory effects as demonstrated in the literature coupled with evidence of significant effects on biopreservation outcome in other cell systems, resveratrol was selected as a compound of interest for this study.

In addition to resveratrol, the unfolded protein response (UPR) inhibitor, salubrinal, was also selected for evaluation in this study. Salubrinal functions to block the apoptotic signaling mechanism induced by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. The intracellular UPR signaling pathway is triggered in response to an accumulation of mis-folded proteins within the ER lumen following stress or pathology. The UPR pathway has two primary mechanisms to combat this stressed state. The first path is characterized by the inhibition of protein translation to prevent the further accumulation of mis-folded proteins while simultaneously up-regulating folding and chaperone proteins to manage the amassed mis-folded proteins thereby returning the cell to homeostasis. However, if the problem proves to be too severe or prolonged, the UPR pathway then shifts signaling towards its secondary function which is to trigger apoptosis. Reports have demonstrated a profound positive effect on cell tolerance to hypothermic conditions when utilizing salubrinal in varous cell systems implicating the vital role of the UPR on storage outcome[12,14,29]. Given the UPR’s increasing level of importance in this and related areas of research[1,2,19,21,27,41], salubrinal was included in this study to determine if UPR signaling plays a role in biopreservation failure of hMSC.

We hypothesized that the results from this study would yield important preliminary groundwork for understanding hMSC bioprocessing failure. Further, through the use of molecular modulators they would also serve as tools to indentify the specific pathways responsible for preservation-induced cell death. The findings presented in this study support the hypothesis that an understanding and modulation of the molecular mechanisms underlying hypothermia-linked stress response can lead to the improved preservation of hMSC and other stem cells used in cell therapies.

Methods and Materials

Cell Culture

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC) (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were maintained under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2/95% air) in mesenchymal basal medium supplemented with a low serum growth kit, gentamicin, amphotericin B, penicillin and streptomycin (ATCC). Cells were propagated in Falcon T-75 flasks from passage 2 through 8 and media was replenished every two days of cell culture.

Hypothermic Storage

Cells were seeded into 96-well tissue culture plates (5,500 cells per well) and cultured for 24 hours into a monolayer. Culture media were aspirated from experimental plates and replaced with 100 μl/well of the pre-cooled (4°C) media (complete growth media [MSCGM], HBSS with calcium and magnesium [Mediatech Inc. Manassas, VA], or ViaSpan [Barr Pharmaceuticals Inc. Montvale, NJ]). Cultures were maintained at 4°C in a temperature monitored refrigerator at normal atmospheric conditions for 18 hours to 3 days. Following the cold storage interval, the media were decanted, replaced with 100 μl/well of warm complete culture media and placed into standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) for recovery and assessment.

Cell Viability Assay

To assess cell viability the metabolic activity assay, alamarBlue™ (Invitrogen) was utilized. Cell culture medium was decanted from the 96-well plates and 100 μl/well of the working alamarBlue™ solution (1:20 dilution in HBSS) was applied. Samples were then incubated for 60 minutes (± 1 min) at 37°C in the dark. The fluorescence levels were analyzed using a Tecan SPECTRAFluorPlus plate reader (TECAN, Austria GmbH). Relative fluorescence units were converted to a percentage compared to normothermic controls set at 100% and data graphed using Microsoft Excel. Viability measurements were taken immediately following removal from storage (0 hour) as well as at 24 and 48 hours of recovery.

Modulation Studies

Chemical modulation of molecular pathways was conducted through the use of salubrinal (UPR-specific inhibitor) and resveratrol. Salubrinal (EMD Chemicals Inc., Gibbstown, NJ) was added to storage media at a working concentration of 25 μM and resveratrol (EMD Chemicals Inc.) at 11 μM immediately before utilization. These concentrations were selected based on previous studies in other cell systems in addition to dose response experiments conducted on these cells (data not shown). Chemicals were diluted in DMSO prior to utilization with final working concentrations of DMSO at 1.3 μM (0.01%) and 32 μM (0.25%) for resveratrol and salubrinal, respectively. DMSO controls of 1.3 μM and 32 μM were conducted to assure no effect of the dilution vehicle.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Samples in 96-well plates were assessed for the presence of live, necrotic or apoptotic cells through triple labeling using Hoechst [81μM], propidium iodide [9μM], and YO-PRO-1 [.8 μM] (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), respectively. Probes were added to samples and incubated in the dark for 15 minutes prior to imaging. Assessment of live and necrotic cell labeling was also conducted using calcein-AM and propidium iodide. Probes were added to the samples and incubated in the dark for 30 minutes prior to aspirating culture media and replacing with 100μL per cell of HBSS with Ca++ and Mg++ before imaging. Fluorescence images of labeled cells were obtained at 1, 4, 8 and 24 hours post-storage using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 fluorescent microscope with the AxioVision 4 software (Zeiss, Germany).

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Counts of the unlabeled (live), necrotic (PI [1.5μM]) and apoptotic (YO-PRO-1 [0.1μM]) labeled cells were obtained using microfluidic flow cytometry (Millipore). Probes were added to each sample and incubated in the dark for 15 minutes prior to cell collection and resuspension for flow cytometry loading. Samples were labeled, collected and analyzed at 1, 4, 8 and 24 hours post-storage. Analysis was performed using the CytoSoft 5.2 software for the Guava PCA-96 system. Post-acquisition data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were cultured in 60mm Petri dishes to form a monolayer. Cell culture media was removed and replaced with 4mL of pre-cooled (4°C) media and dishes were placed at 4°C for 18 hours. Following cold storage, media were decanted and replaced with 4mL of warm culture media and placed into standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) for recovery. Cell lysates were collected 1, 4, 8 and 24 hours post-storage using ice-cold radio-immunoprecipitation assay cell lysis buffer with protease inhibitors. Samples were homogenized by vortex mixing and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. Protein concentrations were quantified using the bicinchonic acid protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and a Tecan SPECTRAFluorPlus plate reader. Equal amounts of protein (25 μg) for each sample were loaded and separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad) and blocked with a 1:1 mixture of NAP -Blocker (G-Biosciences, Maryland Heights, MO) with 0.05% Tween-20 in tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 2 hours at room temperature. Membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight in the presence of each antibody: anti-human Caspase9, anti-human Caspase3, anti-human Caspase7, anti-human Bax, anti-human Bcl-2, anti-human Bid, anti-human Calnexin, anti-human PDI, and anti-human GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Membranes were then washed three times with 0.05% Tween-20 in TBS and exposed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were again washed three times with 0.05% Tween-20 in TBS before detection with the LumiGLO®/Peroxide chemiluminescent detection system (Cell Signaling Technology). Membranes were visualized using a Fujifilm LAS-3000 luminescent image analyzer. Equal protein loading was achieved and confirmed through preliminary quantification of all samples, Ponceau S staining of PVDF membranes prior to blocking and further confirmed through probing for GAPDH levels.

Data Analysis

Viability experiments were repeated a minimum of three times with an intra-experiment repeat of seven replicates. Western blots, flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy were all conducted on a minimum of three separate experiments. Standard errors were calculated for viability values and single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) and student’s t-tests were utilized to determine statistical significance.

Results

Effect of Hypothermic Exposure on Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell (hMSC) Survival

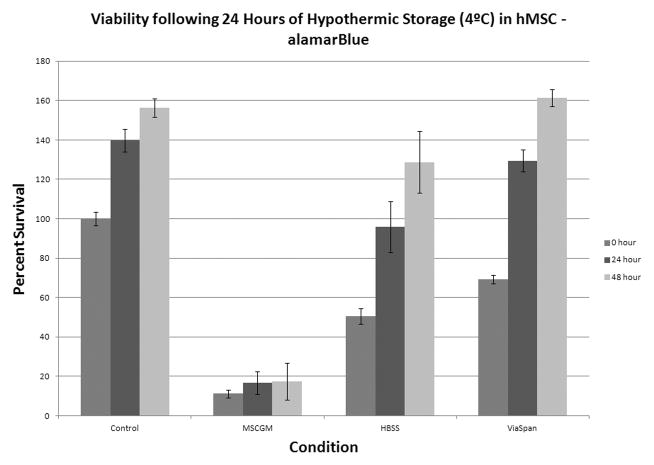

An initial characterization of cold exposure response was conducted utilizing complete growth medium (MSCGM), HBSS with Ca++ and Mg++, and ViaSpan at a range of hypothermic storage intervals from 18 hours to 3 days resulting in the identification of 24 and 48 hour intervals as most critical for further investigation. A loss in viability was observed in all storage media and was found to increase across all conditions as the storage time increased. Specifically, the MSCGM condition demonstrated the greatest cell loss with only 11.2%± 2.0% viability remaining immediately after 24 hours of cold storage (Figure 1A). Both HBSS and ViaSpan conditions demonstrated higher survival of 50.5±3.9% and 65.5±3.8%, respectively. Further, MSCGM stored samples displayed an impaired ability to repopulate as sample viability remained low through the 24 and 48 hour recovery intervals. Both the HBSS and ViaSpan stored samples were observed to regrow to pre-storage control levels by 24 hours post-storage. As storage interval was increased to 2 days of cold exposure, MSCGM storage demonstrated near complete cell loss (Figure 1B). Similarly, HBSS storage displayed significant cell loss yielding only 3.6±0.8% viability, while samples stored in ViaSpan also demonstrated continued decrease in viability to 42.0±6.6%.

Figure 1. Viability Assessment of Hypothermically Stored Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells.

hMSC were placed at 4°C in either: Complete Growth Media (MSCGM), HBSS with Ca++ and Mg++, or ViaSpan for (A) 1 day or (B) 2 days. Cell viability analyses were conducted at 0, 24, and 48 hours post-storage using the metabolic activity indicator, alamarBlue. (n = 4, ±SEM)

Effect of Chemical Modulators on Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell (hMSC) Cold Storage Outcomes

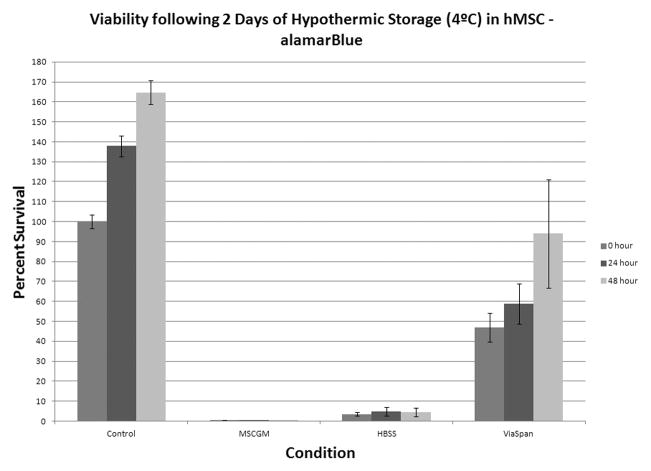

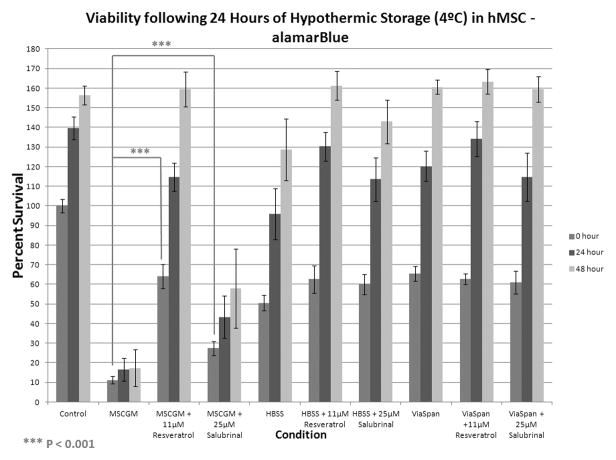

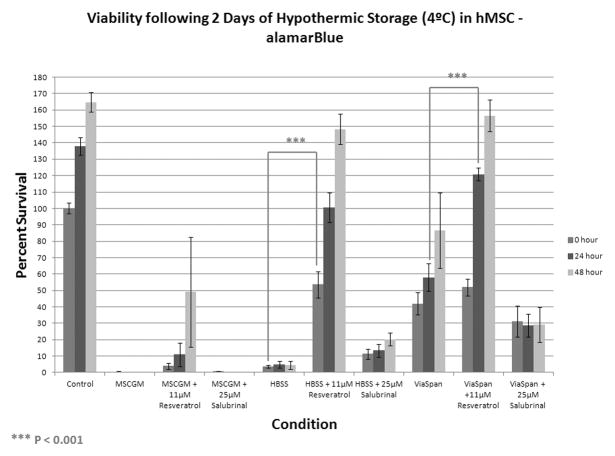

Following the establishment of the hMSC cold storage viability profile for the three different storage conditions, focus shifted to investigating the impact of chemical modulator addition on outcome. The addition of resveratrol to samples stored in MSCGM resulted in a marked improvement in hMSC viability to 64.2±6.1% immediately following 24 hours of hypothermic storage (Figure 2A). Interestingly, a similar affect was not observed in the HBSS and ViaSpan conditions as resveratrol addition resulted in only a minor transient increase in HBSS sample viability and no change in the ViaSpan samples. The addition of salubrinal to the MSCGM stored samples yielded post-storage improvements as well. While only a modest improvement was observed immediately following storage (~16% increase in viability), the improvement conferred with salubrinal was more evident during the post-storage recovery interval with significant increases in cell viability noted at 24 and 48 hours of recovery. Similar to the addition of resveratrol to the HBSS and ViaSpan stored samples, salubrinal incorporation to these conditions resulted in the post-storage viability of these samples.

Figure 2. Assessment of Molecular Modulators on Hypothermically Stored Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells.

hMSC were placed at 4°C in either: Complete Growth Media (MSCGM), HBSS with Ca++ and Mg++, or ViaSpan for (A) 1 day or (B) 2 days alone or with the addition of 11μM resveratrol or 25μM salubrinal. Cell viability analyses were conducted at 0, 24, and 48 hours post-storage using the metabolic activity indicator, alamarBlue. (n = 3, ±SEM)

Following 2 days of cold exposure, samples stored in MSCGM alone resulted in no detectable viability. The addition of resveratrol to cells stored in MSCGM yielded a noticeable improvement in viability (3.9±1.9%) immediately following removal and the cells were able to repopulate during the 48 hours of recovery (Figure 2B). The inclusion of salubrinal to this condition demonstrated no noticeable difference in storage outcome as samples failed to display any remaining viability or ability to re-grow. Interestingly, HBSS stored samples displayed trends comparable to cells stored for 24 hours in MSCGM with preservation in HBSS for 2 days displaying minimal viability or regrowth. As with MSCGM storage, the addition of resveratrol to cells stored in HBSS demonstrated significant improvement in viability (53.7±7.9%) immediately post-storage with successful regrowth during the 48 hour recovery interval. Further, salubrinal inclusion to HBSS samples resulted in improved cold tolerance of these samples as increased viability was noted (11.4±3.0%) with a delayed but evident regrowth during recovery. Cells stored in ViaSpan revealed viability differences at this storage interval as resveratrol addition yielded an improvement in the recovery of these samples at 24 and 48 hours with increased viability levels compared to samples without modulators (120.7±3.9% vs 58.0±8.3%, respectively at 24 hours of recovery). Interestingly, salubrinal addition to ViaSpan resulted in a slightly lower initial viability immediately following 2 days of storage as well as an inhibited ability of these samples to re-grow during recovery.

Effect of Chemical Modulators on Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell (hMSC) Cold Storage Cell Death Populations

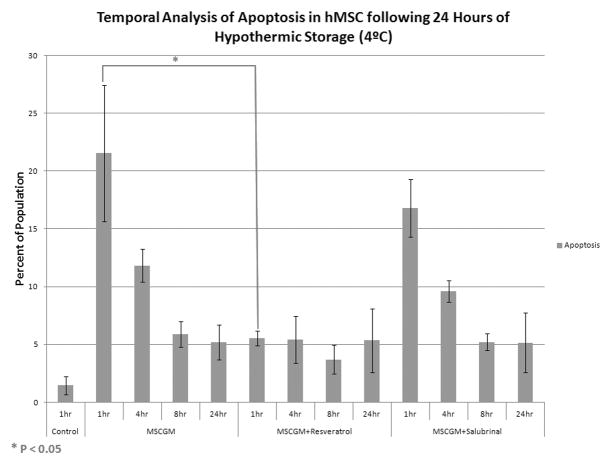

With the identification of cold storage conditions in which modulator addition resulted in significant alteration in outcome, a more in-depth analysis of the modes and mechanisms of cell death underlying this phenomenon was conducted. Specifically, the levels of apoptosis and necrosis were examined at 1, 4, 8 and 24 hours post-hypothermic storage to determine the temporal effect of chemical modulator supplementation on these populations. A 24 hour hypothermic storage regime was performed utilizing MSCGM alone, or MSCGM supplemented with either resveratrol or salubrinal (Figure 3). Analysis of the apoptotic populations for these samples revealed an early peak in the total percentage of apoptosis at 1 to 4 hours post-storage of 21.5±5.9% and 11.8±1.4%, respectively, for cells stored in MSCGM (Figure 3A). The addition of resveratrol resulted in decreased levels of apoptosis throughout the initial 24 hours post-storage as compared to MSCGM storage alone, with the most profound decrease observed immediately 1 hour following removal from hypothermia (21.5±5.9 vs 5.6±0.6%). Interestingly, the incorporation of salubrinal, which resulted in an improvement to cell survival, yielded only a minor decrease in apoptosis at earlier time points (1 and 4 hours) following return to standard culture conditions as compared to MSCGM alone samples. The subsequent time points following this early transitory decrease revealed similar levels of apoptosis as compared to its non-modulated control.

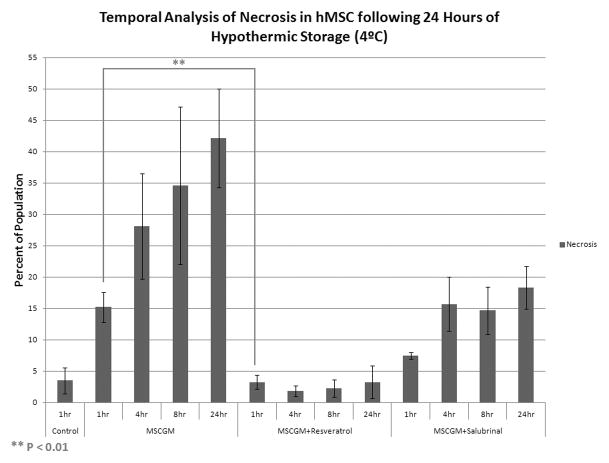

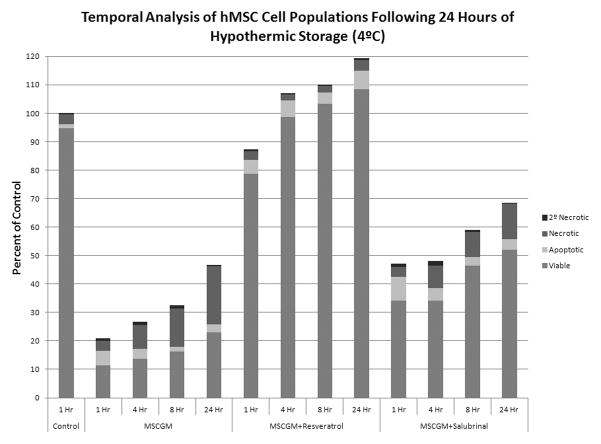

Figure 3. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cell Death Population Following Storage.

hMSC were placed at 4°C in either: MSCGM, MSCGM + 11μM resveratrol, or MSCGM + 25μM salubrinal for 24 hours. Following the storage interval, flow cytometric analysis of the viable (unstained), apoptotic (YO-PRO-1) and necrotic (propidium iodide) populations was conducted at 1, 4, 8, and 24 hours post-storage. (A) Apoptotic population analysis following 24 hours of hypothermic storage in either: MSCGM, MSCGM + 11μM resveratrol, or MSCGM + 25μM salubrinal addition. (n=3, ±SEM) (B) Necrotic population analysis following 24 hours of hypothermic storage in either: MSCGM, MSCGM + 11μM resveratrol, or MSCGM + 25μM salubrinal addition. (n=3, ±SEM) (C) Normalized total hMSC population analysis following 1 day of cold storage in either: MSCGM, MSCGM + 11μM resveratrol, or MSCGM + 25μM salubrinal addition. (n=3)

The analysis of the necrotic population in these samples revealed its central role in cell death following hypothermic storage. Cells stored in MSCGM alone for 24 hours revealed increased levels (15.2±2.4%) of necrosis as compared to normothermic controls (3.5±2.1%) at 1 hour post-preservation (Figure 3B). Necrotic populations continued to increase throughout the 24 hours of recovery with a prominent peak noted at 24 hours post-storage. The addition of resveratrol to stored samples revealed marked decreases in necrosis throughout the recovery time points, with levels at all time points well below that of its uninhibited counterpart, and similar to normothermic control values. Similarly, salubrinal addition to these samples resulted in decreased levels of necrosis throughout the 24 hours of recovery compared to non-modulated samples as well with a delayed necrotic peak at 24 hours of 18.3±3.4%.

The improvements in sample viability conferred through molecular modulation observed via alamarBlue analysis were also demonstrated via flow cytometry as decreases in the relative levels of both apoptosis and necrosis. As shown in Figure 3C, when samples are analyzed as stacked populations normalized to pre-storage normothermic controls, the overall outcomes for these samples displayed results that agreed with the results from alamarBlue analysis. Samples stored in MSCGM alone resulted in decreased cell survival as demonstrated by the relatively low levels of viable cells (bottom portion of bars) and total cell retention (entire bar) as compared to modulated counterparts. The addition of resveratrol resulted in significant improvements to both the viable cell populations and total cell retention, supporting the viability data. Similarly, the addition of salubrinal to cells stored in MSCGM resulted in improved levels of viable cells and total cell retention, which once again corroborated the viability studies.

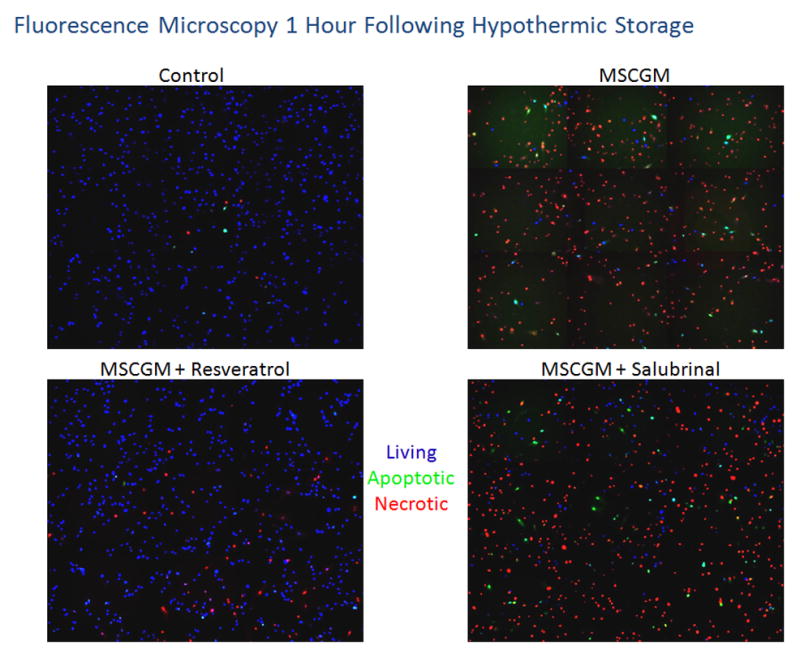

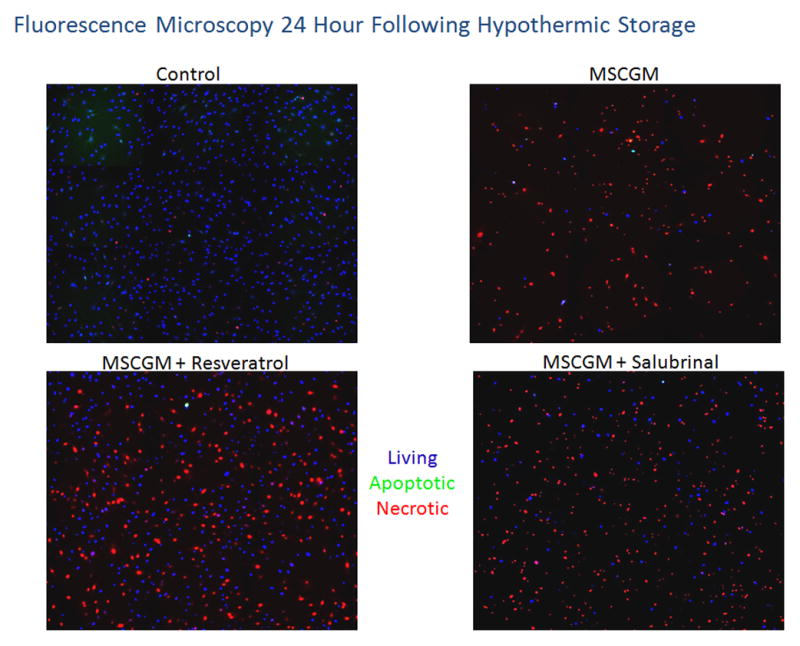

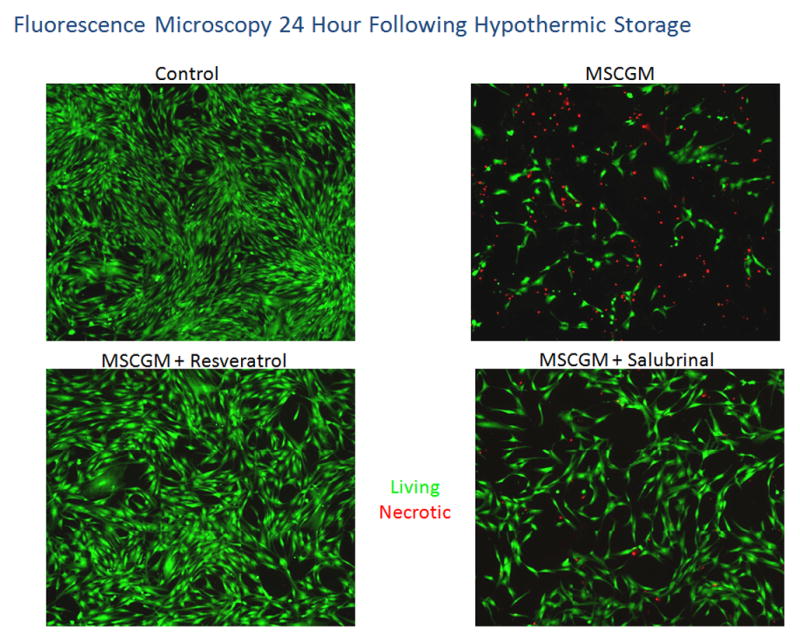

Fluorescence Micrograph Analysis of Chemical Modulators on Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell (hMSC) Cold Storage Outcomes

Further analyses of post-preservation outcomes were conducted utilizing fluorescence microscopy to corroborate and qualitatively visualize the cell death results obtained via flow cytometry. Fluorescence micrograph analysis illustrated and confirmed the differential viable (blue), necrotic (red) and apoptotic (green) populations at 1 and 24 hours following 24 hours of hypothermic storage in MSCGM, MSCGM with resveratrol and MSCGM with salubrinal conditions as compared to the normothermic control (Figures 4A and 4B). These data revealed similar trends as found via flow cytometric analysis with low levels of both necrosis and apoptosis seen in the normothermic control. Further, cells stored in MSCGM resulted in increased levels of both apoptosis and necrosis and a decrease in the number of viable cells immediately at 1 hour of recovery. The MSCGM samples supplemented with resveratrol show differences as levels of both necrosis and apoptosis were reduced while the viable cell population was considerably larger in agreement with flow cytometry findings. The addition of salubrinal resulted in improvements over samples stored in MSCGM alone as increased levels of viable cells were noted. Necrosis and apoptosis, however, remained relatively elevated for these samples.

Figure 4. Fluorescent Micrographic Analysis of Cell Death Population Following Storage.

hMSC samples were placed at 4°C in either: MSCGM, MSCGM + 11μM resveratrol, or MSCGM + 25μM salubrinal for 24 hours. Fluorescent micrographs were recorded at 1(A) and 24(B) hours of recovery and cells probed for viable (Hoechst, blue), apoptotic (YO-PRO-1, green) and necrotic (propidium iodide, red) populations. (C) Fluorescent micrographs were imaged at 24 hours of recovery and cells probed for viable (Calcein-AM, green) and necrotic (propidium iodide, red) populations.

As recovery time increased, this analysis was again conducted at the 24 hour post-storage time point (Figure 4B). Again, the normothermic control samples revealed low levels of baseline apoptosis and necrosis. The MSCGM samples displayed a high level of necrosis with minimal apoptosis and a low overall level of viable cells. Once more, resveratrol addition resulted in a decrease in apoptotic and necrotic cells as compared to cells stored in MSCGM alone. While there were increased levels of necrosis at 24 hours post-storage as compared to 1 hour post storage for cells stored in MSCGM supplemented with resveratrol, an increased and sustained level of viable cells was found again corroborating the flow cytometric analyses. Cells stored in MSCGM supplemented with salubrinal also showed an improvement at 24 hours post-storage as compared to its non-modulated counterpart characterized by an increase in the amount of viable cells within these samples. Taken together the fluorescence microscopy analysis substantiated the results of the flow cytometric analysis confirming an early peak in apoptosis and increasing levels of necrosis during the 24 hours post-storage interval.

In addition to the analyses using Hoechst, propidium iodide and YO-PRO-1 staining, a second set of fluorescence microscopy experiments were conducted utilizing Calcein-AM and propidium iodide to analyze live and dead cells, respectively. These experimental results were again consistent with the previous studies displaying the beneficial effects of resveratrol and salubrinal addition on cells stored in MSCGM. Fluorescence micrograph analysis of these samples at 24 hours post-storage revealed minimal remaining attached and viable (green) cells in the MSCGM samples without modulators (Figure 4C). Once again, a difference was observed with the inclusion of resveratrol as a considerable increase in attached and viable cells was noted (Figure 4C). Salubrinal addition to the samples also demonstrated improvements as more viable and attached cells were observed as compared to cells stored in MSCGM alone.

Protein Immunoblot Analysis of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell (hMSC) Cold Storage Outcomes

Protein immunoblots were conducted to examine changes in cell stress specific protein levels following hypothermic storage in an effort to identify the stress pathways affected by salubrinal and resveratrol. The 24 hour hypothermic storage interval utilizing cells stored in MSCGM alone or MSCGM supplemented with either resveratrol or salubrinal were selected given the previously observed increase in viability as a result of reduced apoptosis and necrosis. Protein was isolated at 1, 4, 8 and 24 hours post-storage for analysis. The examination of known apoptotic signaling proteins revealed changes associated with pro-apoptotic cell death signaling in the cells stored in MSCGM alone, particularly at the earlier time points (Figure 5). These changes were mitigated with resveratrol addition and to a lesser extent with salubrinal addition. The apoptotic proteins caspase 9, caspase 3, caspase 7, Bid, Bax and Bcl-2 were examined and revealed changes indicative of activation and progression of cell death signaling cascades more predominantly in samples stored in MSCGM and MSCGM supplemented with salubrinal. This included the cleavage of pro-caspases and Bid to active forms in combination with sustained levels of pro-apoptotic protein Bax coupled with decreasing levels of pro-survival protein Bcl-2 (i.e. decreased Bcl2/Bax ratio). Further, the examination of alterations to ER stress indicator proteins calnexin and PDI suggested that ER stress and UPR activation was occurring within the hMSC samples as a consequence of hypothermic storage. This was supported by an observed increase in the folding protein PDI for all conditions and subsequent, time-dependent calnexin cleavage which was most evident in cells stored in MSCGM alone. These alteration patterns in PDI and calnexin protein levels were less apparent in cells stored in MSCGM supplemented with either salubrinal or resveratrol.

Figure 5. Western Blot Analysis of Cell Death Related Proteins Following Storage.

hMSC were placed at 4°C for 24 hours in either: MSCGM, MSCGM + 11μM resveratrol, or HBSS + 25μM salubrinal. Following storage protein was isolated from cell populations from these three conditions at 1, 4, 8 and 24 hours post-storage. hMSC samples were probed for apoptotic signaling related proteins: pro-caspase 9, pro-caspase 3, pro-caspase 7, Bid, Bax and BCL-2 as well as UPR pathway proteins calnexin and PDI following 24 hours of hypothermic storage. GAPDH levels shown as loading control.

Discussion

In this investigation hMSC samples were subjected to a hypothermic storage stress regime in several different media (MSCGM, HBSS or ViaSpan) to examine the overall impact on cell viability and the molecular response of these cells. Further, the chemical modulators resveratrol and salubrinal were investigated to assess their impact on hMSC tolerance to hypothermic storage. These inhibitors were selected based on previous reports that demonstrated their differential roles as both protective and detrimental to cell viability and function in other cell systems[12]. Further, other investigations have also revealed that a single molecular modulator could have both a positive or negative effect on outcome which is specific to the cell type, storage temperature and medium[14]. This has led to a notion of process/stressor specific modulation as these data have suggested that no single solution formulation or inhibitor may be optimal in all situations.

This study characterized hMSC response to hypothermic stress (storage) and built upon our current understanding of stress pathway modulation in this clinically relevant cell type. The results of this study illustrate that solution formulation and chemical modulation can significantly impact cellular tolerance to hypothermic conditions and thereby outcome. Cells stored in MSCGM, HBSS or ViaSpan revealed considerable differences in hMSC sample viability following relatively short storage periods. Further, the addition of resveratrol resulted in an improvement in cell viability following storage compared to non-modulated storage controls. This observation was interesting given the conflicting reports in the literature of resveratrol as an anti-proliferation agent, particularly for cancer cell types[22,34,39,42], while also having demonstrated effects of life-extension and cardio-protection[36,40,43,44]. The data presented herein demonstrates resveratrol confers a clear cytoprotective effect in hMSC to hypothermic stress. Further, this effect was observed regardless of media utilized. In addition, salubrinal demonstrated improvements in viability to cells stored in MSCGM and HBSS only. These effects, however, were not nearly as pronounced as the increases observed following resveratrol addition. Interestingly, salubrinal addition to ViaSpan resulted in decreased sample viability. Taken together, these data suggest there is a differential impact of molecular modulation on hMSC tolerance to hypothermic storage and the importance of a targeted approach to improve outcome.

Analyses of cell death populations illustrated a strong molecular component to the cell death observed following hypothermic exposure. Storage in MSCGM alone for 24 hours resulted in a large and rapid apoptotic peak (>20% of the population) at 1 hour of recovery, with levels remaining elevated at 4 hours post-storage and then decreasing to 24 hours of recovery. Interestingly, the data demonstrated a strong anti-apoptotic effect for resveratrol as its inclusion resulted in a decreased and sustained level of apoptosis throughout the 24 hours of recovery. Salubrinal addition resulted in a slight decrease in apoptosis at the early 1 and 4 hour time points, as compared to cells stored in MSCGM alone but did not confer the same level of anti-apoptotic effect as resveratrol. Analysis of necrotic populations revealed high levels for cells stored in MSCGM which were reduced with both resveratrol and salubrinal addition. These cell death data were corroborated with fluorescence microscopy utilizing two different viability/cell death assays demonstrating the significant impact molecular modulation had on the levels of both apoptosis and necrosis.

Molecular pathway analyses via immunoblotting demonstrated alterations in protein levels consistent with the activation and progression of pro-apoptotic signaling in samples stored in MSCGM including the cleavage of pro-caspases and Bid to active forms and a pro-apoptotic shift in the Bcl-2/Bax ratio as Bax remained elevated while Bcl-2 expression decreased. In corroboration with the results observed via cell death analyses, resveratrol addition was found to reduce the level of change in pro-apoptotic protein signaling as noted through sustained levels of both pro-caspases and Bcl-2. Interestingly, salubrinal addition demonstrated partial blockage of apoptotic signaling when compared to cells stored in MSCGM alone. Taken together with the cell death analysis revealing only minor changes in the levels of apoptosis but significant alterations in necrosis with salubrinal addition, these results further support the notion and involvement of molecular based necrosis and the linkage between apoptosis and necrosis (cell death continuum). Further, the addition of resveratrol resulted in a decrease in both apoptosis and necrosis illustrating that a molecular based modulation approach can impact multiple modes of cell death.

The results of this study also implicate the UPR pathway as a potential mediator of cell death signaling following hypothermic storage. As mentioned previously, salubrinal is a known inhibitor of UPR related apoptotic cell death signaling. Therefore its ability to alter hMSC survival following hypothermic storage suggests that UPR signaling may play a role in cold storage failure. Further, alterations in ER stress related protein levels demonstrated changes associated with UPR activation in samples stored in MSCGM alone. This included up-regulation of folding protein PDI and cleavage of calnexin - an indicator of ER stress related pro-apoptotic signaling. Interestingly, salubrinal addition resulted in an earlier up-regulation of PDI and less calnexin cleavage as compared to cells stored in MSCGM alone. Even more notable was resveratrol’s ability to completely block calnexin cleavage and achieve a more sustained level of PDI protein following hypothermic exposure. These observations are further supported by the recent literature which suggests that resveratrol may, in part, mediate its effects as both a cytoprotective and cryotoxic agent through an ER mediated mechanism[9,25,27,28,32,39,42,46]. Here we show that its protective effect appears to correlate with a decrease in ER stress related signaling.

Overall, the findings presented in this study are an important first step in understanding the complex molecular changes hMSC experience as a result of exposure to hypothermic conditions. A more complete analysis of the cell stress pathway signaling cascades activated will be critical to improving hMSC processing and biobanking. In this regard hMSC bioprocessing and biobanking includes a number of different cell stresses that include thermal shifts, hypoxia, and mechanical stress, each of which may activate a different set of cell stress pathways. As the therapeutic potential of hMSC’s grows in response to continued research demonstrating the increasing number of applications in the cell therapy arena, the ability to successfully harvest, isolate, expand, preserve and deliver these cells will likely become the limiting factors. The ability to modulate stress responses across all conditions could allow for optimal retention of viability and functionality to improve hMSC applications. Continued investigation will also be necessary to insure that the post-preservation differentiation potential of hMSC’s is not affected in response to biopreservation protocols. Particularly, as identified pathways are modulated to improve hMSC survival, the validation of hMSC differentiation potential will be critical for their use in downstream applications. Additionally, studies are now beginning to show that the cell stress response does not consist of a universal activation pattern conserved among all cell types but rather a specific and complex set of molecular changes that can differ depending on a number of factors including but not limited to cell type, media formulation, stress paradigm, duration, etc. As such, further research is required to characterize and identify these responses with the aim of specifically tailoring the various steps of bioprocessing so that improved hMSC viability and function can be achieved.

Acknowledgments

Funding provided through NIH Grant: 1R43RR032140-01

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Al-Rawashdeh FY, Scriven P, Cameron IC, Vergani PV, Wyld L. Unfolded protein response activation contributes to chemoresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1099–105. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283378405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin RC. The unfolded protein response in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009 doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baust JG. Concepts in biopreservation. In: Baust JG, Baust JM, editors. Advances in biopreservation. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2007. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baust JM. Molecular mechanisms of cellular demise associated with cryopreservation failure. Cell Preservation Technology. 2002;1:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baust JM. Properties of cells and tissues influencing preservation outcome: Molecular basis of preservation-induced cell death. In: Baust JG, Baust JM, editors. Advances in biopreservation. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2007. pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baust JM, Snyder KK, Van Buskirk RG, Baust JG. Changing paradigms in biopreservation. Biopreservation and Biobanking. 2009;7:3–12. doi: 10.1089/bio.2009.0701.jmb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellavia M, Altomare R, Cacciabaudo F, Santoro A, Allegra A, Concetta Gioviale M, Lo Monte AI. Towards an ideal source of mesenchymal stem cell isolation for possible therapeutic application in regenerative medicine. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2013 doi: 10.5507/bp.2013.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biancone L, Bruno S, Deregibus MC, Tetta C, Camussi G. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived microvesicles. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:3037–42. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinta SJ, Poksay KS, Kaundinya G, Hart M, Bredesen DE, Andersen JK, Rao RV. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death in dopaminergic cells: Effect of resveratrol. J Mol Neurosci. 2009;39:157–68. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9170-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christofferson DE, Yuan J. Necroptosis as an alternative form of programmed cell death. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:263–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke DM, Robilotto AT, Rhee E, VanBuskirk RG, Baust JG, Gage AA, Baust JM. Cryoablation of renal cancer: Variables involved in freezing-induced cell death. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2007;6:69–79. doi: 10.1177/153303460700600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corwin WL, Baust JM, Baust JG, Van Buskirk RG. The unfolded protein response in human corneal endothelial cells following hypothermic storage: Implications of a novel stress pathway. Cryobiology. 2011;63:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corwin WL, Baust JM, Vanbuskirk RG, Baust JG. In vitro assessment of apoptosis and necrosis following cold storage in a human airway cell model. Biopreserv Biobank. 2009;7:19–27. doi: 10.1089/bio.2009.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corwin WL, Baust JM, Baust JG, Vanbuskirk RG. Implications of differential stress response activation following non-frozen hepatocellular storage. Biopreserv Biobank. 2013;11:33–44. doi: 10.1089/bio.2012.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosentino LM, Corwin W, Baust JM, Diaz-Mayoral N, Cooley H, Shao W, Van Buskirk R, Baust JG. Preliminary report: Evaluation of storage conditions and cryococktails during peripheral blood mononuclear cell cryopreservation. Cell Preservation Technology. 2007;5:189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimarino AM, Caplan AI, Bonfield TL. Mesenchymal stem cells in tissue repair. Front Immunol. 2013;4:201. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorronsoro A, Robbins PD. Regenerating the injured kidney with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4:39. doi: 10.1186/scrt187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudley J, Das S, Mukherjee S, Das DK. Resveratrol, a unique phytoalexin present in red wine, delivers either survival signal or death signal to the ischemic myocardium depending on dose. J Nutr Biochem. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fullwood MJ, Zhou W, Shenolikar S. Targeting phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2alpha to treat human disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2012;106:75–106. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396456-4.00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han J, Zhong CQ, Zhang DW. Programmed necrosis: Backup to and competitor with apoptosis in the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1143–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: Controlling cell fate decisions under er stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang TT, Lin HC, Chen CC, Lu CC, Wei CF, Wu TS, Liu FG, Lai HC. Resveratrol induces apoptosis of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via activation of multiple apoptotic pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:720–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, Messadeq N, Milne J, Lambert P, Elliott P, Geny B, Laakso M, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating sirt1 and pgc-1alpha. Cell. 2006;127:1109–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leist M, Single B, Castoldi AF, Kuhnle S, Nicotera P. Intracellular adenosine triphosphate (atp) concentration: A switch in the decision between apoptosis and necrosis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1481–1486. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Wang L, Huang K, Zheng L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in retinal vascular degeneration: Protective role of resveratrol. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:3241–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Tian H, Chen Z, Yue W, Li S, Li W. Inhibition of lung cancer cell proliferation mediated by human mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2011;43:143–8. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmq118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Xu S, Giles A, Nakamura K, Lee JW, Hou X, Donmez G, Li J, Luo Z, Walsh K, Guarente L, Zang M. Hepatic overexpression of sirt1 in mice attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin resistance in the liver. FASEB J. 2011;25:1664–79. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-173492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu BQ, Gao YY, Niu XF, Xie JS, Meng X, Guan Y, Wang HQ. Implication of unfolded protein response in resveratrol-induced inhibition of k562 cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:778–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manekeller S, Schuppius A, Stegemann J, Hirner A, Minor T. Role of perfusion medium, oxygen and rheology for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death after hypothermic machine preservation of the liver. Transpl Int. 2008;21:169–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathew AJ, Van Buskirk RG, Baust JG. Improved hypothermic preservation of human renal cells through suppression of both apoptosis and necrosis. Cell Preservation Technology. 2002;1:239–253. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicotera P, Leist M, Fava E, Berliocchi L, Volbracht C. Energy requirement for caspase activation and neuronal cell death. Brain Pathol. 2000;10:276–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2000.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park JW, Woo KJ, Lee JT, Lim JH, Lee TJ, Kim SH, Choi YH, Kwon TK. Resveratrol induces pro-apoptotic endoplasmic reticulum stress in human colon cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:1269–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peltz L, Gomez J, Marquez M, Alencastro F, Atashpanjeh N, Quang T, Bach T, Zhao Y. Resveratrol exerts dosage and duration dependent effect on human mesenchymal stem cell development. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shankar S, Nall D, Tang SN, Meeker D, Passarini J, Sharma J, Srivastava RK. Resveratrol inhibits pancreatic cancer stem cell characteristics in human and krasg12d transgenic mice by inhibiting pluripotency maintaining factors and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor MJ. Biology of cell survival in the cold: The basis for biopreservation of tissues and organs. In: Baust JG, Baust JM, editors. Advances in biopreservation. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2007. pp. 15–62. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terzibasi E, Valenzano DR, Cellerino A. The short-lived fish nothobranchius furzeri as a new model system for aging studies. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian LL, Yue W, Zhu F, Li S, Li W. Human mesenchymal stem cells play a dual role on tumor cell growth in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1860–7. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trincheri NF, Nicotra G, Follo C, Castino R, Isidoro C. Resveratrol induces cell death in colorectal cancer cells by a novel pathway involving lysosomal cathepsin d. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:922–931. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Um HJ, Bae JH, Park JW, Suh H, Jeong NY, Yoo YH, Kwon TK. Differential effects of resveratrol and novel resveratrol derivative, hs-1793, on endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis and akt inactivation. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:1007–13. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valenzano DR, Terzibasi E, Genade T, Cattaneo A, Domenici L, Cellerino A. Resveratrol prolongs lifespan and retards the onset of age-related markers in a short-lived vertebrate. Curr Biol. 2006;16:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verfaillie T, Garg AD, Agostinis P. Targeting er stress induced apoptosis and inflammation in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang FM, Galson DL, Roodman GD, Ouyang H. Resveratrol triggers the pro-apoptotic endoplasmic reticulum stress response and represses pro-survival xbp1 signaling in human multiple myeloma cells. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:999–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang S, Wang X, Yan J, Xie X, Fan F, Zhou X, Han L, Chen J. Resveratrol inhibits proliferation of cultured rat cardiac fibroblasts: Correlated with no-cgmp signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;567:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, Sinclair D. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature. 2004;430:686–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu W, Liu P, Li J. Necroptosis: An emerging form of programmed cell death. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yan Y, Gao YY, Niu XF, Liu BQ, Zhuang Y, Wang HQ. Resveratrol-induced cytotoxicity in human burkitt’s lymphoma cells is coupled to the unfolded protein response. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:445. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang X, Hou J, Han Z, Wang Y, Hao C, Wei L, Shi Y. One cell, multiple roles: Contribution of mesenchymal stem cells to tumor development in tumor microenvironment. Cell Biosci. 2013;3:5. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X, Zhang L, Xu W, Qian H, Ye S, Zhu W, Cao H, Yan Y, Li W, Wang M, Wang W, Zhang R. Experimental therapy for lung cancer: Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell-mediated interleukin-24 delivery. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13:92–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]