Abstract

Many efforts are being made in translating the nanopore into an ultrasensitive single-molecule platform for various genetic and epigenetic detections. However, compared with current approaches including PCR, the low throughput limits the nanopore applications in biological research and clinical settings, which usually requires simultaneous detection of multiple biomarkers for accurate disease diagnostics. Herein we report a barcode probe approach for multiple nucleic acid detection in one nanopore. Instead of directly identifying different targets in a nanopore, we designed a series of barcode probes to encode different targets. When the probe is bound with the target, the barcode group polyethylene glycol attached on the probe through click chemistry can specifically modulate nanopore ion flow. The resulting signature serves as a marker for the encoded target. Therefore counting different signatures in a current recording allows simultaneous analysis of multiple targets in one nanopore. The principle of this approach was verified by using a panel of cancer-derived microRNAs as the target, a type of biomarker for cancer detection.

Keywords: nanopore, microRNA, click chemistry, barcode, multiplex detection

Individual molecules translocating in a nanopore can characteristically change the ionic current through the pore. This merit renders the nanopore a sensitive single-molecule identifier and counter for genetic,1−10 epigenetic,11−18 and various biomolecular detections.19−26 However, challenges exist in translating nanopores into a practical tool for both research and biomedical applications. Compared with other biosensing approaches,27−31 one issue for nanopores is the low capacity in multiplex detection. For example, the nanopore has been studied for detecting cancer-derived circulating microRNAs (miRNAs),15,16,32 a class of small regulatory RNAs33 that function as a new type of biomarkers.34,35 Different from common methods such as RT-PCR, the nanopore approach does not need covalent labeling and amplification of the target. This leads to a lower variation in measurement,35−37 making the nanopore a candidate for noninvasive cancer detection. On the other hand, disease detection requires accurate measurement of a biomarker panel, rather than a single miRNA species.36,37 The current nanopore technology cannot meet this need because it can analyze only one miRNA per detection. Although nanopore multiplex detection has been reported,38−46 their common principle, i.e., different targets (unlabeled or labeled) generating distinct nanopore signatures, is not applicable to miRNA detection. Due to their similar polymer lengths (18–22 bases), miRNAs cannot be distinguished from each other by their signatures. This demands new nanopore strategies for multiplex biomarker detection.

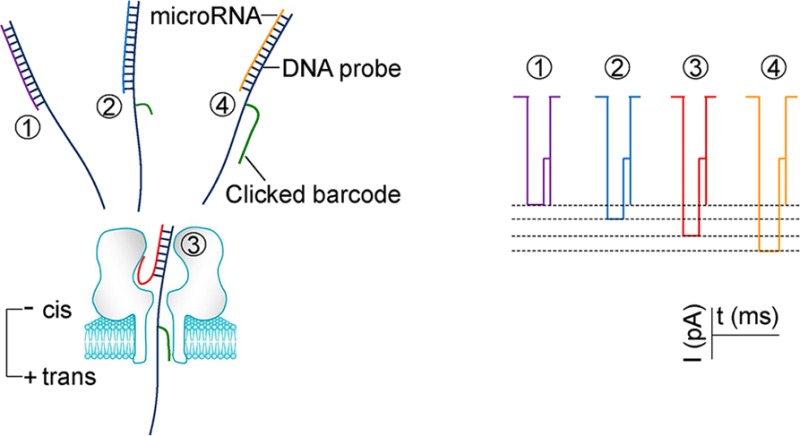

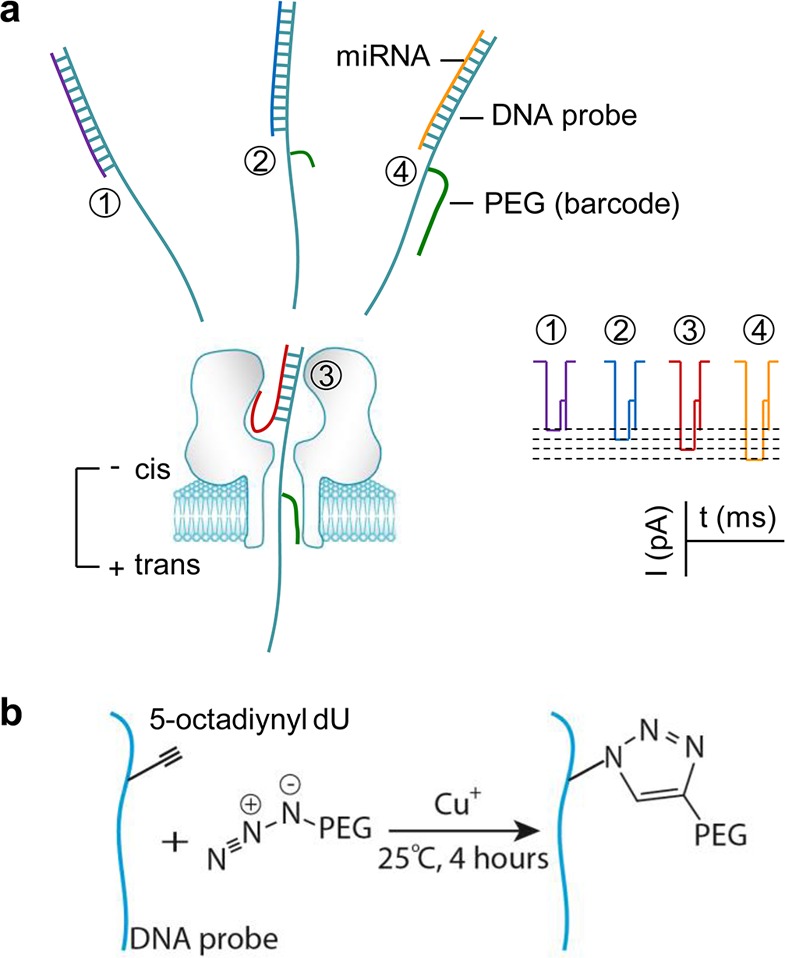

In this report, a biophysical mechanism for programming nanopore ionic flow was investigated. On the basis of this mechanism, a series of barcode probes were constructed through click chemistry. Each barcode motif trapped in the nanopore can specifically modulate the nanopore ionic current and therefore can encode different target nucleic acids. These universal barcode probes working together enable simultaneous detection of multiple miRNAs in a biomarker panel (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Barcode modulation of nanopore ionic current and multiplex detection of nucleic acid. Each target miRNA is hybridized with a PEG-labeled DNA probe. Upon being trapped in the nanopore, the PEG on the hybrid specifically regulates the nanopore current, thereby generating a signature for target identification. (b) Conjugation of a DNA probe with a PEG barcode through one-step copper(I)-catalyzed click chemistry.

Results and Discussion

The probe comprises a capture arm to bind the target miRNA and a universal 3′-poly(dC)30 lead appended to the capture arm to pull the miRNA·probe hybrid into the nanopore. This lead sequence can greatly increase the hybrid capture rate.15 When entering the nanopore from its cis entrance, the duplex domain of the hybrid is accommodated in the nanocavity (2.6–4.6 nm wide), while the single-stranded lead occupies the β-barrel (1.5–2.0 nm wide) (Figure 1a). A polyethylene glycol (PEG) tag was linked to the lead as the barcode group. This is because PEGs of different lengths can characteristically block the pore current;43,46 this soluble and flexible polymer is unlikely to form a folded structure with DNAs or affect DNA structures, and copper(I)-catalyzed click chemistry47,48 provides a simple and rapid method to conjugate PEG with DNA in high yield.49,50 These merits render PEG a favorable motif for barcode construction. Specifically, PEG was tagged to a 5-octadiynyl deoxyuridine between the second and third cytosine (C2 and C3) in the lead next to the capture arm (Table S1 for sequences). The click chemistry allowed formation of a 1,2,3-triazole between azide on the PEG terminal and alkyne on the DNA (Figure 1b, Materials and Methods). This position is located in the sensing zone of the pore while being separated from the miRNA·probe duplex to avoid affecting its hybridization. The target is a panel of four lung cancer-derived miRNAs, including miR-155, miR-182-5p, miR-210, and miR-21.36,37 For each miRNA, four probes have been constructed: one without a tag (P0) and the other three tagged with a 3-, 8-, and 24-mer PEG (P3, P8, and P24) on the lead, respectively (Table S1). The MALDI-TOF mass spectrogram confirms the highly effective conjugation of PEGs to DNA probes (Figure S1).

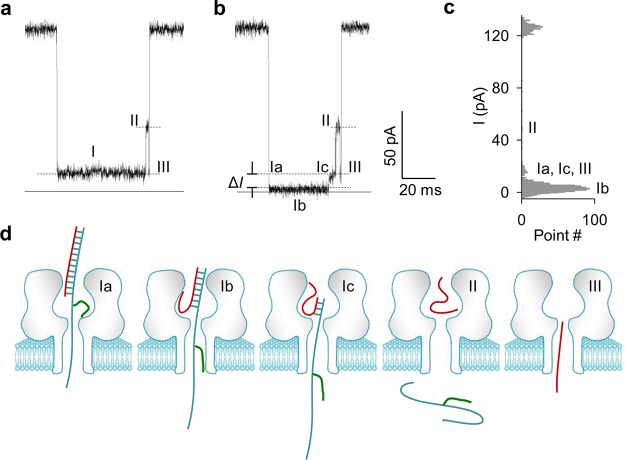

The typical miRNA·probe signatures are illustrated in Figure 2a and b. These signatures cannot be identified for translocation of the probe alone in the nanopore (Figure S2). The signature for untagged probe features three sequential stages: I, II, and III. Each stage is at a specific blocking level (Figure 2a). By comparison, the signature for using a PEG-tagged probe retains stage II and III, but its stage I is split into Ia, Ib, and Ic (Figure 2b and c). The molecular configuration of PEG-tagged miRNA·probe in a nanopore for each stage is illustrated in Figure 2d. Specifically, the blocking level I/I0 for stage Ia is (12.0 ± 0.1)% (I0 and I are currents of the empty and blocked nanopore, respectively). Given that this blocking level is the same as stage I for using untagged probe (Figure 2a), it is suggested that stage Ia is for the DNA probe alone occupying the β-barrel,15 and the PEG tag has not yet entered this region (Ia in Figure 2d). When the PEG tag enters the β-barrel, the current can be further reduced to stage Ib. Throughout stage Ib, the miRNA·probe duplex is consistently unzipped, driven by the voltage. Along with unzipping, the probe associated with the PEG tag slides in the β-barrel toward the trans opening (Ib in Figure 2d). When the PEG tag moves out of the pore into trans solution, the current resumes to stage Ic, which is at the same level as Ia (Ic in Figure 2d). Stage Ic is terminated when the unzipping finishes and the probe leaves the pore from the trans opening. At this moment, the dissociated miRNA alone is left shortly in the nanocavity. This configuration partially reduces the current to stage II (I/I0 = 57%), which exists in signatures for both untagged (Figure 2a) and PEG-tagged probes (Figure 2b). The miRNA in the nanocavity finally passes through the β-barrel, generating the stage III ending spike. Overall, the signature profile vividly depicts the step-by-step dehybridization of the miRNA·probe hybrid. In this process, the PEG tag acts as a position marker as the probe threads through the nanopore. The resulting difference in blocking level allows visual discrimination of the miRNA hybridized with untagged (Figure 2a) and PEG-tagged probes (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a, b) Signatures for miR-155 (miRNA) hybridized with an unlabeled probe (P0) (a) and a PEG24-labeled probe (P24) (b). The PEG label allows generating a distinct current profile compared with the block using unlabeled probe. (c) Histogram showing the current amplitude of each stage in the signature in panel b. (d) Molecular configurations for sequential stages in b. When a miR-155·P24 hybrid is trapped in the pore, the single-stranded lead first enters the β-barrel (Ia). As the lead threads in the pore, the PEG label moves into the β-barrel to further reduce the blocking level (Ib). The lead with the PEG label is pulled by the electric field to induce the unzipping of the miR-155·P24 hybrid and continuously slides in the β-barrel while unzipping occurs. The PEG label finally slides out of the pore, resulting in higher pore conductance (Ic). After unzipping and probe translocation, the dissociated miR-155 temporarily resides in the nanocavity (II) and finally translocates through the β-barrel (III) to terminate the block.

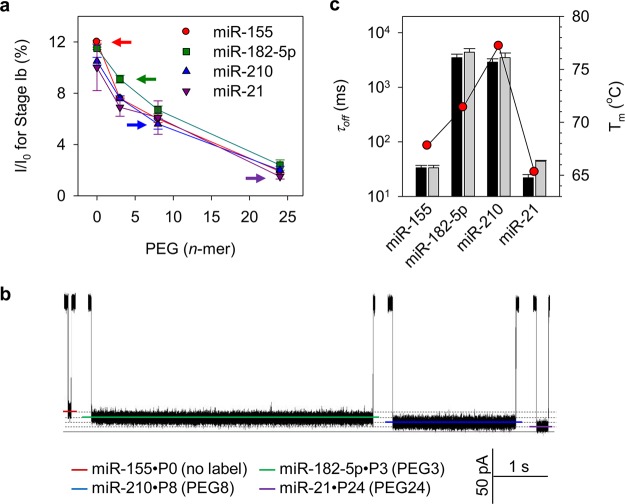

Will different types of PEG be able to specifically modulate the blocking level, thus producing specific signatures? This question is important because it is the foundation for nanopore application in multiplex detection. Figure 3a shows that, for all the miRNAs tested, the blocking level of stage Ib is consistently reduced by increasing the length of the PEG tag. For example, I/I0 of stage Ib for miR-155 is (12 ± 0.1)% by using an untagged probe. This level can be continuously reduced to (7.6 ± 0.1)%, (6.0 ± 0.3)%, and (1.9 ± 0.1)% as the probe is tagged with P3, P8, and P24. This finding suggests the possibility of using PEG to program the stage Ib blocking level. The average current reduction per PEG unit is 1.2 pA for P3, 0.69 pA for P8, and 0.45 pA for P24 (1 M KCl, +120 mV). This is consistent with previous findings that different length PEGs or PEG-labeled nucleotides can be discriminated by blocking levels43,46 at a resolution of 1.6 pA per PEG unit (4 M KCl, +40 mV).46 Notably, such blocking level modulation is only sensitive to the PEG tag, but independent of miRNA species. Figure 3a indicates that using probes with the same PEG tag to detect different miRNAs resulted in similar blocking levels. For example, I/I0 of stage Ib for the four P8-labeled miRNA·probe complexes only slightly vary between 5.6% and 6.7%.

Figure 3.

Modulation of miRNA·probe blocking level by PEGs of different lengths. (a) PEG length-dependent blocking level (I/I0) for stage Ib of the signatures (as illustrated in Figure 2b) for four miRNAs: miR-155 (●), miR-182-5p (■), miR-210 (▲), miR-21 (▼). The four colored arrows mark an optimized miRNA/probe combination: miR-155·P0 (red), miR-182-5p·P3 (green), miR-210·P8 (blue), and miR-21·P24 (purple). The four miRNA·probe hybrids demonstrate maximally separated blocking levels, enabling accurate detection of multiplex miRNA species. (b) Distinct signatures for the four optimized miRNA·probe hybrids (miR-155·P0, miR-182-5p·P3, miR-210·P8, and miR-21·P24) marked in panel a. (c) Duration of four miRNA·probe signatures with untagged (black bar) and barcoded (gray bar) probes. Melting temperatures of the four miRNAs are also shown (red circles). The block duration is positively correlated to the miRNA·probe melting temperature. Method for obtaining block duration is described in S1 in the SI.

Because the PEG tag on the probe can modulate the nanopore current, the tag identity should be distinguishable based on the blocking level. This allows using tag identities to encode different miRNAs. An optimal encoding pattern is shown in Figure 3a, in which four colored arrows mark a group of four miRNA·probe hybrids: the untagged probe is assigned to miR-155 to give the highest I/I0 of (12 ± 0.1)% (red), and the P3-, P8-, and P24-tagged probes are assigned to miR-182-5, miR-210, and miR-21, with I/I0 consistently decreased to (9.1 ± 0.2)% (green), (5.6 ± 0.3)% (blue), and (1.5 ± 0.4)% (purple). Indeed, their signatures in Figure 3b clearly reveal well-separated blocking levels, allowing almost error-free discrimination of four miRNAs. These signatures are different not only in blocking level but also in duration. Figure 3c shows that the signatures for miR-182-5p·P3 (4.4 ± 1 s) and miR-210·P8 (3.5 ± 1.1 s) hybrids are over 100 times prolonged compared with miR-155·P0 (33 ± 4 ms) and miR-21·P24 (28 ± 2 ms) hybrids (gray bars), and the four hybrids using untagged probes (black bars) show a very similar trend to the tagged hybrids, indicating that the signature duration is independent of PEG tag. Figure 3c shows that the duration difference among the four signatures is qualitatively consistent with their miRNA melting temperatures (Tm) (Figure 3c). Tm values for miR-182-5p and miR-210 are significantly higher than for miR-155 and miR-21 due to their higher GC content. This effect stabilizes their hybrids, leading to a prolonged unzipping procedure. Overall, the signature duration is regulated by the target sequence but not the PEG tag (S1).

The ability to program nanopore ion flow highly depends on the tag compound property and its position on the probe. For example, replacing PEG with TET (a popular fluorescein dye for labeling oligonucleotides) can permanently block the pore (S2, Figure S5). The blocking current becomes too noisy, making it difficult to dissect molecular configurations. Such a block cannot be used as a programmable signature. In contrast, the PEG tag reveals multiple distinct stages for molecular trapping, unzipping, and translocation. Signatures for different PEG tags have consistent patterns and distinct blocking levels; thus PEG is an optimal barcode motif. In addition to tag structure, its position in the nanopore also affects the current modulation ability (S2, Figure S6). For example, P8 tagged between C5/C6 along the probe close to the pore opening, rather than C2/C3 in the sensing zone, can no longer generate the characteristic stage Ib, making it impossible to discriminate blocking levels by differently tagged probes. This example demonstrates the importance of tagging position to current modulation. Mechanistically, the PEG modulation of nanopore conductance originates from the volume exclusion effect: longer PEG occupies more volume in the ion pathway, thus reducing more ionic current. In addition, binding of K+ ion to the C–O–C motif of PEG could decrease the mobile ion concentration.51 Moreover, in our case, the interaction between the weak cationic PEG and the negatively charged DNA might also influence the ion mobility, which is worth analysis in the following work.

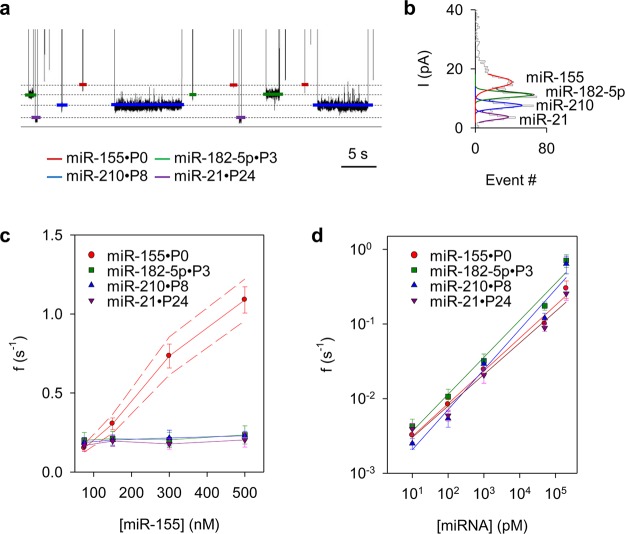

Figure 4a shows a current trace in the presence of four miRNAs mixed with their barcode probes (Figure S8 for a long trace). The trace reveals four types of signatures. The event amplitude histogram in Figure 4b indicates that their distinct blocking levels are consistent with the barcodes: from high to low amplitude, P0 for miR-155, P3 for miR-182-5p, P8 for miR-210, and P24 for miR-21. Figure 4c measures the frequencies of four miRNA·probe signatures as one miRNA (miR-155) concentration increases from 75 nM to 500 nM, while the remaining three miRNA concentrations are fixed to 75 nM (see S3 in the SI for signature frequency analysis in multiplex detection). The miR-155·P0 frequency is proportional to the miR-155 concentration, and those for other miRNAs are almost unchanged as the miR-155 concentration increases. These results indicate that the quantitation of one miRNA is independent of the presence of other miRNA·probe complexes. Given that four miRNAs at the same concentration (75 nM) demonstrate similar signature frequencies (0.15–0.20 s–1), they should be trapped in the pore at similar capture rates (2–3 μM–1·s–1). These capture rates are also similar to that using untagged probes in a previous report,15 suggesting that PEG tags do not influence the trapping efficiency. Figure 4d shows that the frequencies of the four miRNA·probe signatures monotonically increased as their miRNA concentrations increase in a broad range from 10 pM to 200 nM. The frequency for each miRNA has been determined in the presence of the other three miRNAs at the same concentration. Each frequency–concentration correlation curve can be used to calibrate the miRNA quantitation in multiplex detection. The 10 pM miRNA was detected by analyzing over 100 signatures in 3 or 4 nanopores for 2 h. However, this is not the ultimate detection limit (see S3 in the SI). Any approach that can improve the capture rate can be integrated to lower the detection limit, such as using a salt gradient,5 engineered pores,52 and a miniaturized system.53,54 The in vivo miRNA expression is highly dependent on the miRNA species and tissues. The real-time detection limit also relies on the efficiency in total RNA extraction15 and enrichment.55 Currently RT-PCR is still the gold standard, but the nanopore is quicker and less expensive, without the need for covalent labeling and enzymatic reaction on the target (see S4 in the SI for comparison of nanopore and other approaches). If the barcode method can be validated in the following work, the nanopore will gain multiplex detection capability for parallel analysis of a biomarker panel.

Figure 4.

(a) Simultaneous observation of multiple miRNA·probe blocking levels in a current trace. Each level is for a specific miRNA species. From top to bottom, the four conductance levels are for miR-155·P0, miR-182-5p·P3, miR-210·P8, and miR-21·P24. All miRNAs were at 50 nM. (b) Event amplitude histogram based on over 2000 blocks obtained from the trace in panel a, showing the distinct blocking levels for the four signatures. An extended trace showing more signatures is illustrated in Figure S8a, and the duration–current scattering plot showing the separation of the four signatures is given in Figure S8b. (c, d) Signature frequencies at various miRNA concentrations in multiplex detection. In c, the miR-155 concentration varies while other miRNA concentrations are fixed to 75 nM. Confidential intervals are marked. The frequency of miR-155 signatures increases as its concentration increases, whereas the frequencies of the other three miRNAs remain unchanged and are not influenced by the increasing miR-155 concentration. In d, each miRNA was measured in the presence of other miRNAs at the same concentration. The signature frequencies for all four miRNAs are increased in proportion to their concentrations and do not interfere with each other. Each concentration has been measured based on at least three independent nanopores.

Conclusion

In summary, we have elucidated a biophysical mechanism for modulating nanopore ionic flow through tagging a barcode motif on the nucleic acid duplex. The barcode tag sliding in the pore marks the molecular processes, trapping, unzipping, and translocation. As each barcode tag specifically blocks the nanopore, different barcodes can be used to encode different target sequences, therefore realizing nanopore multiplex detection.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Materials

All compounds used for the click chemistry reaction were purchased from Jena Bioscience (Jena, Germany), including PEG3 (11-azido-3,6,9-trioxaundecan-1-amine), PEG8 (O-(2-aminoehyl)-O′-(2-azideoethyl)heptaethylene glycol), PEG24 (1-[2-(2,2-[2-(2,2-[2-(2,2-[2-(2-azidoethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxyethoxy)ethoxy]-2-methoxyethane), and 6-TET azide (16-oxo-16-(2′,4,7,7′-tetrachloro-3-oxo-3′,6′-bis(pivaloyloxy)-2,3,4a′,9a′-tetrahydrospiro[indene-1,9′-xanthen]-6-yl)-6,9,12-trioxa-2,3,15-triazahexadeca-1,2-dien-2-ium). Other chemicals, including sodium acetate (CH3COONa), copper(I) bromide (CuBr), ethanol (CH3COOH), tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, HCl, potassium hydroxide, tert-butanol ((CH3)3COH), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) ((CH3)2SO), pentane, hexadecane, and tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4yl)methyl]amine (TBTA), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used as received. 1,2-Diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine used for lipid bilayer formation was from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA) and used without further purification. Nuclease-free water and all DNA probe and synthesized microRNAs were bought from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). All the sequence information of probes and microRNAs used in this work are listed in Table S1.

Labeling of DNA Probes with PEGs and TET

All PEG-azides, including PEG3, PEG8, and PEG24, and 6-TET azide were attached to the DNA probes through copper(I)-catalyzed click chemistry in a single-step reaction50 (Figure 1b). Briefly, 5 μL of alkyne-modified DNA probe solution (2 mM in water), 2 μL of PEG-azide or TET-azide solution (50 mM in 3:1 DMSO/t-BuOH), and 2 μL of a freshly prepared click solution (0.1 M CuBr and 0.1 M TBTA ligand in a 1:2 ratio in 3:1 DMSO/t-BuOH) were thoroughly mixed and shaken at 250 rpm and 25 °C for 4 h. The reaction was subsequently diluted with 100 μL of sodium acetate (0.3 M). The PEG-labeled DNA product was precipitated using 1 mL of cold ethanol. The supernatant was then discarded, and the product in the residue was washed twice with 1 mL of cold ethanol. The washed residue was redissolved in Millipore water and could be used without further purification.

miRNA/Probe Hybridization

Hybridization solutions were solutions of the target microRNAs with related DNA probes at various concentrations in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4, 10 mM) containing potassium chloride (500 mM). Mixtures of target microRNA with its related DNA probes or multiple microRNAs with DNA probes were incubated with 100 μL of the hybridization solution at 95 °C for 10 min, then cooled to room temperature gradually and left to stand for 30 min before electrophysiology measurement.

Electrophysiology Measurements

Briefly, a membrane of 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine was formed on a small orifice in a Teflon partition that separates two identical Teflon chambers.56 Each chamber contained 2 mL of electrolyte solution (1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4). Less than 1 μL of α-hemolysin was added to the cis chamber, and excess protein was immediately removed after a conductance increase heralded the formation of a single channel. The ionic current through the α-hemolysin protein nanopore was recorded by an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA), filtered with a built-in 4-pole low-pass Bessel filter at 5 kHz, and finally acquired into the computer using a DigiData 1440A A/D converter (Molecular Devices) at a sampling rate of 20 kHz. The data recording and acquisition were controlled through a Clampex program (Molecular Devices). The analysis of nanopore current traces, including event scatter plot analysis, duration histogram analysis, and amplitude histogram analysis, was performed using Clampfit software (Molecular Devices).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Beverly B. DaGue for mass spectroscopy experiments. This work was supported by grants from National Science Foundation (0546165), National Institutes of Health (P01GM079613), and Coulter Translational Partnership Program at University of Missouri.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information Available

miRNA sequence-dependent signature duration analysis, optimum barcode motif and tagging position, discussion on multitarget quantification and comparison of the nanopore with current approaches. These materials are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Howorka S.; Siwy Z. Nanopore Analytics: Sensing of Single Molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2360–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langecker M.; Arnaut V.; Martin T. G.; List J.; Renner S.; Mayer M.; Dietz H.; Simmel F. C. Synthetic Lipid Membrane Channels Formed by Designed DNA Nanostructures. Science 2012, 338, 932–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majd S.; Yusko E. C.; Billeh Y. N.; Macrae M. X.; Yang J.; Mayer M. Applications of Biological Pores in Nanomedicine, Sensing, and Nanoelectronics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 439–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan B. M.; Bashir R. Nanopore Sensors for Nucleic Acid Analysis. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanunu M.; Morrison W.; Rabin Y.; Grosberg A. Y.; Meller A. Electrostatic Focusing of Unlabelled DNA into Nanoscale Pores Using a Salt Gradient. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 160–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendell D.; Jing P.; Geng J.; Subramaniam V.; Lee T. J.; Montemagno C.; Guo P. Translocation of Double-Stranded DNA through Membrane-Adapted phi29 Motor Protein Nanopores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 765–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner J. E.; Balijepalli A.; Robertson J. W. F.; Campbell J.; Suehle J.; Kasianowicz J. J. Disease Detection and Management via Single Nanopore-Based Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 6431–6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherf G. M.; Lieberman K. R.; Rashid H.; Lam C. E.; Karplus K.; Akeson M. Automated Forward and Reverse Ratcheting of DNA in a Nanopore at 5Å Precision. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 344–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasianowicz J. J.; Brandin E.; Branton D.; Deamer D. W. Characterization of Individual Polynucleotide Molecules Using a Membrane Channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 13770–13773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manrao E. A.; Derrington I. M.; Laszlo A. H.; Langford K. W.; Hopper M. K.; Gillgren N.; Pavlenok M.; Niederweis M.; Gundlach J. H. Reading DNA at Single-Nucleotide Resolution with a Mutant MspA Nanopore and phi29 DNA Polymerase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 349–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An N.; Fleming A. M.; White H. S.; Burrows C. J. Crown Ether-Electrolyte Interactions Permit Nanopore Detection of Individual DNA Abasic Sites in Single Molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2012, 109, 11504–11509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace E. V.; Stoddart D.; Heron A. J.; Mikhailova E.; Maglia G.; Donohoe T. J.; Bayley H. Identification of Epigenetic DNA Modifications with a Protein Nanopore. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U.K.) 2010, 46, 8195–8197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. W.; Gong L.; Bayley H. Single-Molecule Detection of 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in DNA through Chemical Modification and Nanopore Analysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4350–4355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim J.; Humphreys G. I.; Venkatesan B. M.; Munz J. M.; Zou X.; Sathe C.; Schulten K.; Kosari F.; Nardulli A. M.; Vasmatzis G.; etal. Detection and Quantification of Methylation in DNA Using Solid-State Nanopores. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Zheng D.; Tan Q.; Wang M. X.; Gu L. Q. Nanopore-Based Detection of Circulating MicroRNAs in Lung Cancer Patients. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 668–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanunu M.; Dadosh T.; Ray V.; Jin J.; McReynolds L.; Drndić M. Rapid Electronic Detection of Probe-Specific MicroRNAs Using Thin Nanopore Sensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo A. H.; Derrington I. M.; Brinkerhoff H.; Langford K. W.; Nova I. C.; Samson J. M.; Bartlett J. J.; Pavlenok M.; Gundlach J. H. Detection and Mapping of 5-Methylcytosine and 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine with Nanopore MspA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 18904–18909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber J.; Wescoe Z. L.; Abu-Shumays R.; Vivian J. T.; Baatar B.; Karplus K.; Akeson M. Error Rates for Nanopore Discrimination among Cytosine, Methylcytosine, and Hydroxymethylcytosine along Individual DNA Strands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 18910–18915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. Y.; Ying Y. L.; Li Y.; Kraatz H. B.; Long Y. T. Nanopore Analysis of Beta-Amyloid Peptide Aggregation Transition Induced by Small Molecules. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 1746–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Y. L.; Wang H. Y.; Sutherland T. C.; Long Y. T. Monitoring of an ATP-Binding Aptamer and its Conformational Changes Using an Alpha-Hemolysin Nanopore. Small 2011, 7, 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdhar A.; Sathe C.; Schulten K.; Leburton J. P. Graphene Quantum Point Contact Transistor for DNA Sensing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 16748–16753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravelle S.; Joly L.; Detcheverry F.; Ybert C.; Cottin-Bizonne C.; Bocquet L. Optimizing Water Permeability through the Hourglass Shape of Aquaporins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 16367–16372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R.; Gatterdam V.; Wieneke R.; Tampe R.; Rant U. Stochastic Sensing of Proteins with Receptor-Modified Solid-State Nanopores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington L.; Cheley S.; Alexander L. T.; Knapp S.; Bayley H. Stochastic Detection of Pim Protein Kinases Reveals Electrostatically Enhanced Association of a Peptide Substrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, E4417–E4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk S. W.; Hall A. R.; Dekker C. Detection of Local Protein Structures along DNA Using Solid-State Nanopores. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 324–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Larrea D.; Bayley H. Multistep Protein Unfolding during Nanopore Translocation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 288–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring A. G.; Tu S.-I. High-Throughput Biosensors for Multiplexed Food-Borne Pathogen Detection. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2011, 4, 151–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller D. A.; Jin H.; Martinez B. M.; Patel D.; Miller B. M.; Yeung T.-K.; Jena P. V.; Hobartner C.; Ha T.; Silverman S. K.; etal. Multimodal Optical Sensing and Analyte Specificity Using Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 42114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qavi A. J.; Bailey R. C. Multiplexed Detection and Label-Free Quantitation of MicroRNAs Using Arrays of Silicon Photonic Microring Resonators. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4608–4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M.; Husimi Y.; Komatsu H.; Suzuki K.; Douglas K. T. Quantum Dot FRET Biosensors that Respond to pH, to Proteolytic or Nucleolytic Cleavage, to DNA Synthesis, or to a Multiplexing Combination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5720–5725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wark A. W.; Lee H. J.; Corn R. M. Multiplexed Detection Methods for Profiling MicroRNA Expression in Biological Samples. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian K.; He Z.; Wang Y.; Chen S. J.; Gu L. Q. Designing a Polycationic Probe for Simultaneous Enrichment and Detection of MicroRNAs in a Nanopore. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 3962–3969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi M. T.; Zhao Y.; Rotunno M.; Koshiol J.; Liu H.; Bergen A. W.; Rubagotti M.; Goldstein A. M.; Linnoila I.; Marincola F. M.; etal. MicroRNA Expression Differentiates Histology and Predicts Survival of Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 430–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio M. V.; Croce C. M. MicroRNAs in Cancer: Small Molecules with a Huge Impact. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5848–5856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. S.; Parkin R. K.; Kroh E. M.; Fritz B. R.; Wyman S. K.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan E. L.; Peterson A.; Noteboom J.; O’Briant K. C.; Allen A.; etal. Circulating MicroRNAs as Stable Blood-Based Markers for Cancer Detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 10513–10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeri M.; Verri C.; Conte D.; Roza L.; Modena P.; Facchinetti F.; Calabrò E.; Croce C. M.; Pastorino U.; Sozzi G. MicroRNA Signatures in Tissues and Plasma Predict Development and Prognosis of Computed Tomography Detected Lung Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 3713–3718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D.; Haddadin S.; Wang Y.; Gu L. Q.; Perry M. C.; Freter C. E.; Wang M. X. Plasma MicroRNAs as Novel Biomarkers for Early Detection of Lung Cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2011, 4, 575–586. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braha O.; Gu L. Q.; Zhou L.; Lu X. F.; Cheley S.; Bayley H. Simultaneous Stochastic Sensing of Divalent Metal Ions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 1005–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J.; Wu H. C.; Jayasinghe L.; Patel A.; Reid S.; Bayley H. Continuous Base Identification for Single-Molecule Nanopore DNA Sequencing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C.; Ding S.; Tan Q.; Gu L. Q. Method of Creating a Nanopore-Terminated Probe for Single-Molecule Enantiomer Discrimination. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L. Q.; Braha O.; Conlan S.; Cheley S.; Bayley H. Stochastic Sensing of Organic Analytes by a Pore-Forming Protein Containing a Molecular Adapter. Nature 1999, 398, 686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasianowicz J. J.; Henrickson S. E.; Weetall H. H.; Robertson B. Simultaneous Multianalyte Detection with a Nanometer-Scale Pore. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 2268–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Tao C.; Chien M.; Hellner B.; Balijepalli A.; Robertson J. W.; Li Z.; Russo J. J.; Reiner J. E.; Kasianowicz J. J.; etal. PEG-Labeled Nucleotides and Nanopore Detection for Single Molecule DNA Sequencing by Synthesis. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsenberger V.; Mitchell N.; Howorka S. Chemically Labeled Nucleotides and Oligonucleotides Encode DNA for Sensing with Nanopores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7530–7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An N.; White H. S.; Burrows C. J. Modulation of the Current Signatures of DNA Abasic Site Adducts in the Alpha-Hemolysin Ion Channel. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U.K.) 2012, 48, 11410–11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J. W.; Rodrigues C. G.; Stanford V. M.; Rubinson K. A.; Krasilnikov O. V.; Kasianowicz J. J. Single-Molecule Mass Spectrometry in Solution Using a Solitary Nanopore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2007, 104, 8207–8211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan T. R.; Hilgraf R.; Sharpless K. B.; Fokin V. V. Polytriazoles as Copper(I)-Stabilizing Ligands in Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2853–2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtsev V. V.; Green L. G.; Fokin V. V.; Sharpless K. B. A Stepwise Huisgen Cycloaddition Process: Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective “Ligation” of Azides and Terminal Alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2596–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierlich J.; Burley G. A.; Gramlich P. M.; Hammond D. M.; Carell T. Click Chemistry as a Reliable Method for the High-Density Postsynthetic Functionalization of Alkyne-Modified DNA. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3639–3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramlich P. M.; Wirges C. T.; Manetto A.; Carell T. Postsynthetic DNA Modification through the Copper-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8350–8358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balijepalli A.; Robertson J. W. F.; Reiner J. E.; Kasianowicz J. J.; Pastor R. W. Theory of Polymer-Nanopore Interactions Refined Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7064–7072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglia G.; Restrepo M. R.; Mikhailova E.; Bayley H. Enhanced Translocation of Single DNA Molecules through α-Hemolysin Nanopores by Manipulation of Internal Charge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 19720–19725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley H.; Cronin B.; Heron A.; Holden M. A.; Hwang W. L.; Syeda R.; Thompson J.; Wallace M. Droplet Interface Bilayers. Mol. BioSyst. 2008, 4, 1191–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A.; Holden M. A.; Pentelute B. L.; Collier R. J. Ultrasensitive Detection of Protein Translocated Through Toxin Pores in Droplet-Interface Bilayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 16577–16581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin G.; Cid M.; Poole C. B.; McReynolds L. A. Protein Mediated miRNA Detection and siRNA Enrichment Using p19. BioTechniques 2010, 48, xvii–xxiii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L. Q.; Wang Y. Nanopore Single-Molecule Detection of Circulating MicroRNAs. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1024, 255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.