Abstract

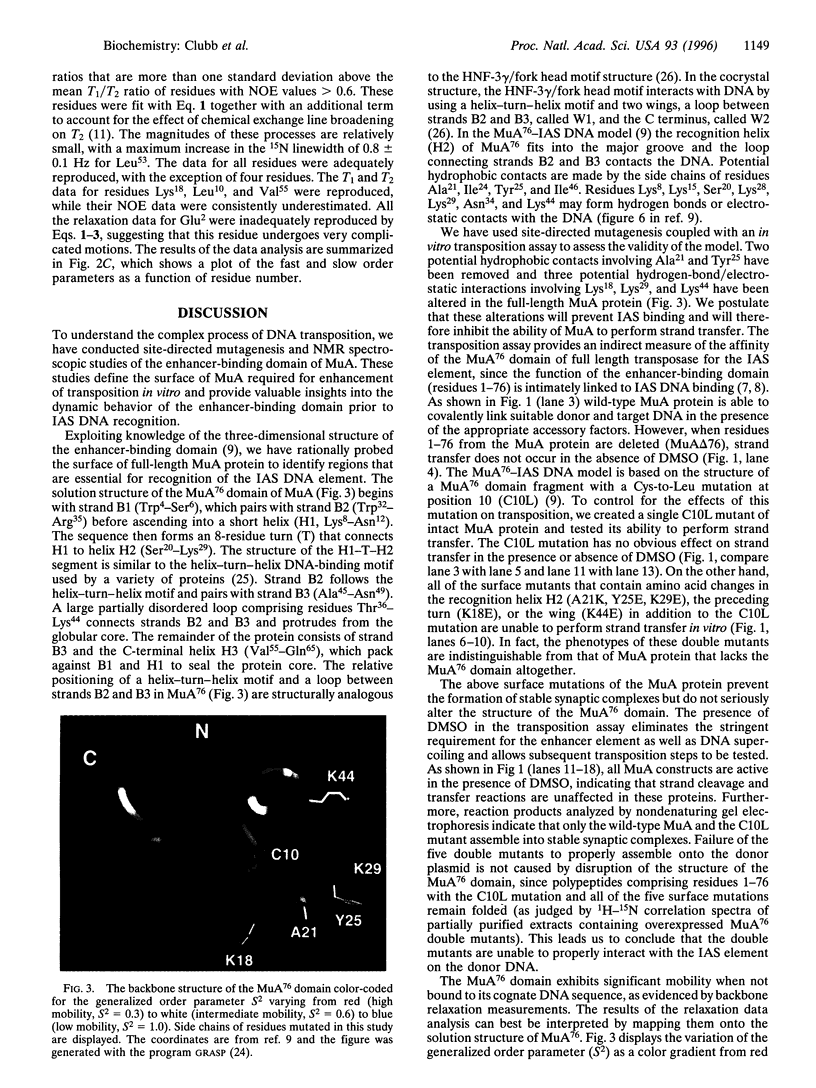

A tetramer of the Mu transposase (MuA) pairs the recombination sites, cleaves the donor DNA, and joins these ends to a target DNA by strand transfer. Juxtaposition of the recombination sites is accomplished by the assembly of a stable synaptic complex of MuA protein and Mu DNA. This initial critical step is facilitated by the transient binding of the N-terminal domain of MuA to an enhancer DNA element within the Mu genome (called the internal activation sequence, IAS). Recently we solved the three-dimensional solution structure of the enhancer-binding domain of Mu phage transposase (residues 1-76, MuA76) and proposed a model for its interaction with the IAS element. Site-directed mutagenesis coupled with an in vitro transposition assay has been used to assess the validity of the model. We have identified five residues on the surface of MuA that are crucial for stable synaptic complex formation but dispensable for subsequent events in transposition. These mutations are located in the loop (wing) structure and recognition helix of the MuA76 domain of the transposase and do not seriously perturb the structure of the domain. Furthermore, in order to understand the dynamic behavior of the MuA76 domain prior to stable synaptic complex formation, we have measured heteronuclear 15N relaxation rates for the unbound MuA76 domain. In the DNA free state the backbone atoms of the helix-turn-helix motif are generally immobilized whereas the residues in the wing are highly flexible on the pico- to nanosecond time scale. Together these studies define the surface of MuA required for enhancement of transposition in vitro and suggest that a flexible loop in the MuA protein required for DNA recognition may become structurally ordered only upon DNA binding.

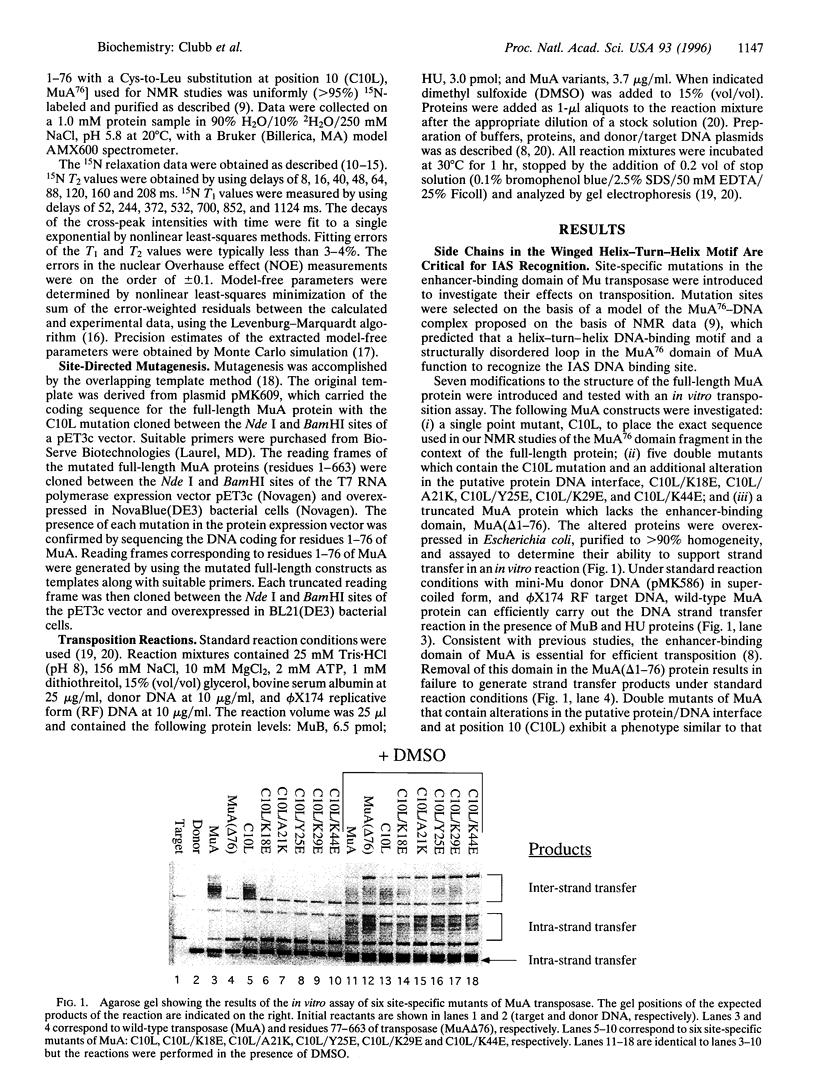

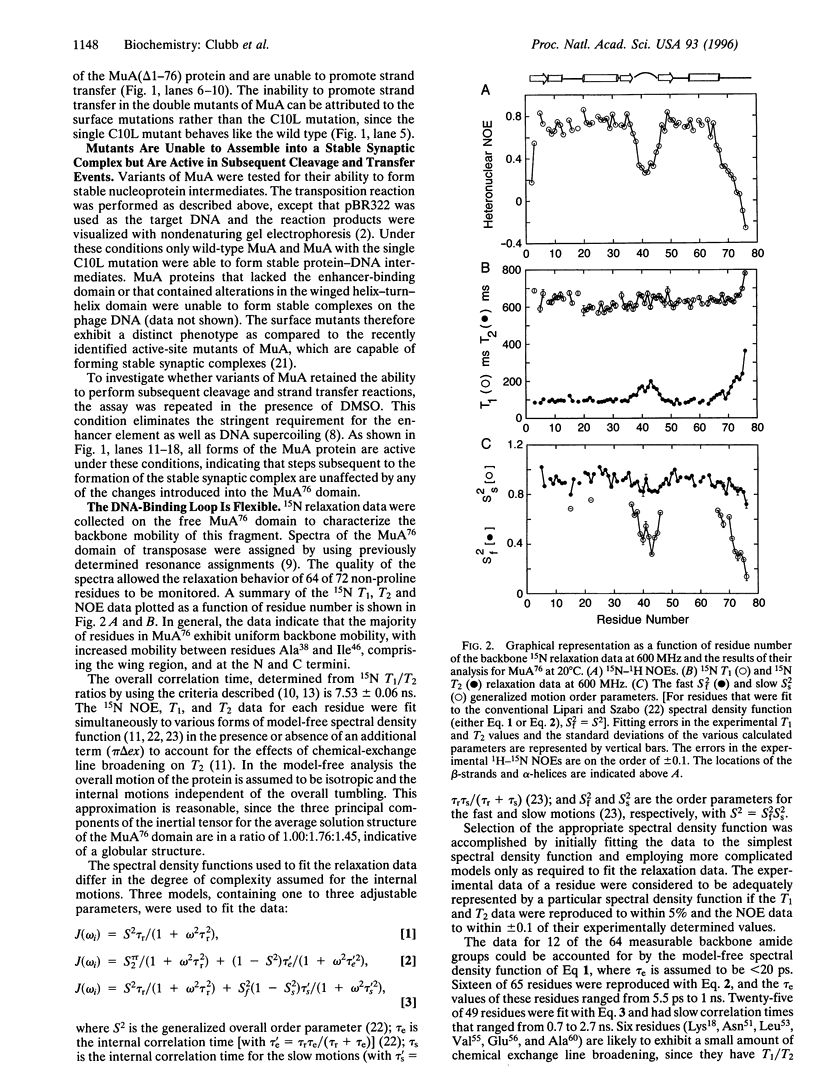

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker T. A., Luo L. Identification of residues in the Mu transposase essential for catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Jul 5;91(14):6654–6658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. A., Mizuuchi K. DNA-promoted assembly of the active tetramer of the Mu transposase. Genes Dev. 1992 Nov;6(11):2221–2232. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. A., Mizuuchi M., Savilahti H., Mizuuchi K. Division of labor among monomers within the Mu transposase tetramer. Cell. 1993 Aug 27;74(4):723–733. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90519-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchi J. J., Jr, Grasberger B., Gronenborn A. M., Clore G. M. Investigation of the backbone dynamics of the IgG-binding domain of streptococcal protein G by heteronuclear two-dimensional 1H-15N nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 1994 Jan;3(1):15–21. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K. L., Halay E. D., Lai E., Burley S. K. Co-crystal structure of the HNF-3/fork head DNA-recognition motif resembles histone H5. Nature. 1993 Jul 29;364(6436):412–420. doi: 10.1038/364412a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore G. M., Driscoll P. C., Wingfield P. T., Gronenborn A. M. Analysis of the backbone dynamics of interleukin-1 beta using two-dimensional inverse detected heteronuclear 15N-1H NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1990 Aug 14;29(32):7387–7401. doi: 10.1021/bi00484a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clubb R. T., Omichinski J. G., Sakaguchi K., Appella E., Gronenborn A. M., Clore G. M. Backbone dynamics of the oligomerization domain of p53 determined from 15N NMR relaxation measurements. Protein Sci. 1995 May;4(5):855–862. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clubb R. T., Omichinski J. G., Savilahti H., Mizuuchi K., Gronenborn A. M., Clore G. M. A novel class of winged helix-turn-helix protein: the DNA-binding domain of Mu transposase. Structure. 1994 Nov 15;2(11):1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigie R., Mizuuchi K. Mechanism of transposition of bacteriophage Mu: structure of a transposition intermediate. Cell. 1985 Jul;41(3):867–876. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigie R., Mizuuchi K. Transposition of Mu DNA: joining of Mu to target DNA can be uncoupled from cleavage at the ends of Mu. Cell. 1987 Nov 6;51(3):493–501. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90645-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasberger B. L., Gronenborn A. M., Clore G. M. Analysis of the backbone dynamics of interleukin-8 by 15N relaxation measurements. J Mol Biol. 1993 Mar 20;230(2):364–372. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S. C., Aggarwal A. K. DNA recognition by proteins with the helix-turn-helix motif. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:933–969. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath U., Shriver J. W. Characterization of thermotropic state changes in myosin subfragment-1 and heavy meromyosin by UV difference spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 1989 Apr 5;264(10):5586–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay L. E., Torchia D. A., Bax A. Backbone dynamics of proteins as studied by 15N inverse detected heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy: application to staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1989 Nov 14;28(23):8972–8979. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P. C., Teplow D. B., Harshey R. M. Interaction of distinct domains in Mu transposase with Mu DNA ends and an internal transpositional enhancer. Nature. 1989 Apr 20;338(6217):656–658. doi: 10.1038/338656a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuuchi K. Transpositional recombination: mechanistic insights from studies of mu and other elements. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:1011–1051. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.005051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuuchi M., Baker T. A., Mizuuchi K. Assembly of the active form of the transposase-Mu DNA complex: a critical control point in Mu transposition. Cell. 1992 Jul 24;70(2):303–311. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90104-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuuchi M., Mizuuchi K. Efficient Mu transposition requires interaction of transposase with a DNA sequence at the Mu operator: implications for regulation. Cell. 1989 Jul 28;58(2):399–408. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90854-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surette M. G., Buch S. J., Chaconas G. Transpososomes: stable protein-DNA complexes involved in the in vitro transposition of bacteriophage Mu DNA. Cell. 1987 Apr 24;49(2):253–262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surette M. G., Chaconas G. The Mu transpositional enhancer can function in trans: requirement of the enhancer for synapsis but not strand cleavage. Cell. 1992 Mar 20;68(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90081-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]