Abstract

Interleukin-1 superfamily of cytokines (IL-1, IL-18, IL-33) play key roles in inflammation and regulating immunity. The mechanisms of agonism and antagonism in the IL-1 superfamily have been pursued by structural biologists for nearly 20 years. New insights into these mechanisms were recently provided by the crystal structures of the ternary complexes of IL-1β and its receptors. We will review here the structural biology related to receptor recognition by IL-1 superfamily cytokines and the regulation of its cytokine activities by antagonists.

Keywords: cytokine, receptors, antagonist, agonist, interleukin, inflammation

Introduction

The interleukin 1 (IL-1) superfamily of cytokines are important regulators of innate and adaptive immunity, playing key roles in host defense against infection, inflammation, injury, and stress. The IL-1 superfamily is comprised of the IL-1, IL-18, IL-33, and the more recent IL-36 and IL-37.1,2 These cytokines are related to each other by origin, receptor structure, and signal transduction pathways.3 The receptors for IL-1 superfamily share a similar architecture, comprised of three Ig-like domains in their ectodomains, and an intracellular Toll/IL-1R (TIR) domain that is also found among Toll-like receptors (Fig. 1).4,5 The initiation of cytokine signaling requires two receptors, a primary specific receptor and an accessory receptor that can be shared in some cases. The primary receptor is responsible for specific cytokine binding, while the accessory receptor by itself does not bind the cytokine but associates with the preassembled binary complexes from the cytokine and the primary receptor. The binding of the cytokines to their respective receptors results in a signaling ternary complex, leading to the dimerization of the TIR domains of the two receptors. This initiates intracellular signaling by activating mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB). The signaling induces inflammatory responses such as the induction of cyclooxygenase Type 2, increased expression of adhesion molecules, and synthesis of nitric oxide.6 A brief overview of the biology of IL-1 superfamily is provided below but more in depth information can be found elsewhere.3,4,7–11 In the past decade, a great deal of structural information on IL-1 receptors (IL-1R) has been acquired. This review will focus mainly on the current knowledge about the ligand-receptor recognition and regulation for IL-1R superfamily members.

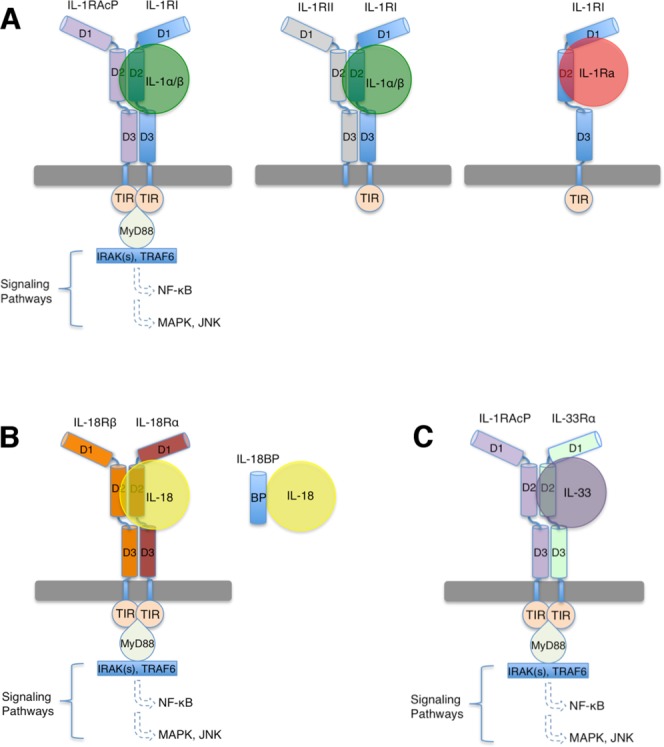

Figure 1.

Cartoon representation of IL-1 superfamily signaling. A: IL-1 signaling is initiated by the ternary complex formation of IL-1α/β:IL-1RI:IL-1RAcP. The decoy receptor IL-1RII lacks an intracellular TIR domain and forms a non-signaling ternary complex with IL-1α/β and IL-1RAcP. The receptor antagonist IL-1Ra binds IL-1RI and forms an inhibitory binary complex that fails to recruit IL-1RAcP. B) IL-18 signaling complex involves IL-18, IL-18Rα and IL-18Rβ. Antagonism is achieved through binding of IL-18BP to IL-18. C) IL-33 signaling involves IL-33, IL-33Rα and IL-1RAcP. The ectodomains of IL-1 superfamily receptors each contains three Ig-like domains, which are labeled as D1, D2, and D3 respectively.

IL-1

IL-1 includes interleukin-1α (IL-1α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β). Both are agonists and are expressed in multiple cell lines including monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, hepatocytes, and tissue macrophages throughout the body. IL-1α is expressed in the cytoplasm as a 31 kDa precursor form (pro-IL-1α) that is biologically active and capable of binding to IL-1R and activating cells. Pro-IL-1α may be cleaved by calpain, a membrane-bound cysteine protease, into the mature 17 kDa IL-1α. Pro-IL-1α lacks a signal peptide or a leader sequence, so it is not released from cells through the typical vesicular transport of the secretary pathway.12,13 The mechanism by which IL-1α is released from cells is not completely understood. Constitutively expressed IL-1α plays a role in regulating interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and its effector genes by maintaining a basal level of the transcription factor NF-κB. Up-regulated expression of IFN-γ in-turn results in the overexpression of the membrane bound form of IL-1α.14 In comparison, IL-1β is not constitutively expressed but its expression is induced upon stimulation by inflammatory signals.9 IL-1β is expressed in the cytoplasm as a 31 kDa pro-form and is processed and released from cells by a mechanism involving IL-1β converting enzyme (ICE), also known as caspase-1. The conversion of the pro-IL-1β by ICE to its mature form can take place in specialized secretory lysosomes or in the cytoplasm.15–17 Unlike pro-IL-1α, pro-IL-1β is biologically inactive and must be converted to the mature 17 kDa IL-1β to acquire the ability to bind to its receptors and activate cells. The primary and accessory receptors for IL-1α/β signaling are IL-1 receptor Type I (IL-1RI) and its accessory protein (IL-1RAcP), respectively.18–20

Antagonism of IL-1 signaling at the extracellular level involves at least two distinct mechanisms through (1) the use of a receptor antagonist, IL-1Ra, which prevents the recruitment of IL-1RAcP; (2) the use of a membrane bound decoy receptor, IL-1 receptor Type II (IL-1RII), which cannot form a signaling complex [Fig. 1(A)]. IL-1Ra is structurally related to other IL-1 cytokines, which binds IL-1RI competitively and prevents its binding to either IL-1α or IL-1β. IL-1RII is highly homologous to IL-1RI with an extracellular domain also being comprised of three Ig domains. However, its cytoplasmic domain is very short (∼25 amino acids), with the TIR domain being absent and thus incapable of initiating signal transduction. Therefore, IL-1RII is a decoy receptor that binds and sequesters IL-1, preventing signal transduction and cell activation. The decoy receptor IL-1RII preferentially binds IL-1β rather than IL-1Ra with a much higher affinity,21 representing one of the natural regulatory mechanisms of IL-1.2

IL-18

Interleukin-18 (IL-18) is involved in both innate and adaptive immune responses.10,22–25 IL-18 was originally referred to as IFN-γ Inducing Factor (IGIF) for its ability to stimulate the production of IFN-γ.26,27 IL-18 stimulates IFN-γ production from T-helper lymphocytes cells (Th1 and Th2) and macrophages, and enhances the cytotoxicity of natural killer (NK) cells. The IL-18 stimulated IFN-γ production is synergistically amplified with other Th1-related cytokines, IL-2, IL-15, IL-12, and IL-23.22,28–30 Much like IL-1β, IL-18 is synthesized as a 23kDa inactive precursor, which is subsequently cleaved into an 18kDa active form by ICE (Caspase-1) and then secreted, resulting in the initiation of IL-18 signaling cascade.27,31 The primary and accessory receptors specific for IL-18 signaling are IL-18Rα and IL-18Rβ, respectively.32,33

IL-18 activity is modulated in vivo by Interleukin-18 Binding Protein (IL-18BP), a soluble protein comprised of a single Ig domain.34,35 The human IL-18BP (hIL-18BP) has an exceptionally high affinity for IL-18 of 400 pM and has been shown to be up-regulated in various cell lines in response to elevated IFN-γ levels, suggesting that it serves as a negative feedback inhibitor of IL-18 mediated immune response.35,36 IL-18BP is also present in the serum of healthy individuals in an ∼20-fold molar excess of IL-18, thus preventing IL-18 from engaging its primary receptor IL-18Rα (discussed in more detail below). Another cytokine of the IL-1 superfamily, IL-1F7B, has been identified with putative antagonist activities against IL-18. However, information about the potential role of IL-1F7B in regulating IL-18 activities remains unclear.37,38

IL-33

Interleukin-33 (IL-33/IL-1F11) is one of the newest members of the IL-1 cytokine superfamily and has many attributes similar to IL-1α. IL-33 is principally involved in Th2-mediated immune responses such as asthma, allergy-induced inflammation, and parasitic infections. It is expressed as a 31 kDa pro-form, while mature IL-33s vary in length with greater than 10-fold potency over the pro-form.39,40 T1/ST2, previously considered an orphan receptor, has been identified as IL-33Rα and is the primary receptor of IL-33. IL-33Rα is principally expressed on Th2 polarized cells and cells involved in the Th2 immune response.41 IL-1RAcP is necessary to form the ternary complex with IL-33:IL-33Rα for signaling. Thus, IL-1RAcP appears to be promiscuous and can participate in the signaling of both IL-1 and IL-33 signaling.42,43

Structural Biology of the IL-1 Superfamily

Cytokines

The three-dimensional structures of six cytokines of the IL-1 superfamily have been determined by either solution NMR or x-ray crystallography (Fig. 2). These include 5 human (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1Ra, IL-18, and IL-33) and 1 murine (IL-36Ra/IL-1F5) cytokines. Despite having limited sequence similarity, these cytokines adopt a conserved signature β-trefoil fold comprised of 12 anti-parallel β-strands that are arranged in a three-fold symmetric pattern. The β-barrel core motif is packed by various amounts of helices in each cytokine structure. Superimposition of the Cα atoms of each of the five human cytokine reveals a conserved hydrophobic core, with significant flexibility in the loop regions (Fig. 2 - Composite). Surface residues and loops between β-strands do not appear to be crucial for overall stability and have diverged significantly between the cytokines, consistent with their low sequence similarity and partially explaining their unique recognition by their respective receptors. For example, human IL-18 shares ∼65% sequence identity to murine IL-18 while sharing only 15% and 18% identity to human IL-1α and human IL-1β, respectively. Nevertheless, IL-18 shows striking similarity to other IL-1 cytokines in its three-dimensional structure.44

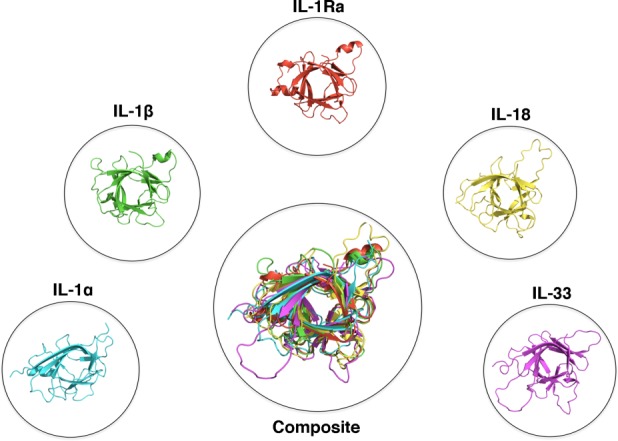

Figure 2.

Structures of IL-1 superfamily cytokines. Cytokines of the IL-1 superfamily adopt a conserved β-trefoil fold. PDB files displayed: IL-1α:2KKI, IL-1β:1I1B, IL-1Ra:1ILR, IL-18:1J0S, IL-33:2KLL.

Binary complex: Cytokine recognition by primary receptors

A key step in signaling initiation by IL-1 superfamily is the formation of a binary complex between the respective cytokine and its primary receptor, subsequently recruiting a second auxiliary receptor subunit. Formation of the hetero-trimeric complex on the cell surface induces the juxtaposition of the cytoplasmic TIR domains from both receptors, which further recruits intracellular factors and triggers the signaling cascade (Fig. 1). A significant amount of structural and functional studies have been accomplished in elucidating the mechanism by which IL-1 superfamily agonists bind their respective receptors. IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 each contain at least two key receptor-binding sites for engaging their respective primary receptors. These receptor-binding sites have similar locations on the surface of the cytokine but display distinctive surface residues. For example, the difference in surface residues among IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 was thought to be one of the mechanisms by which cognate receptor discrimination is achieved (Fig. 3).44,45

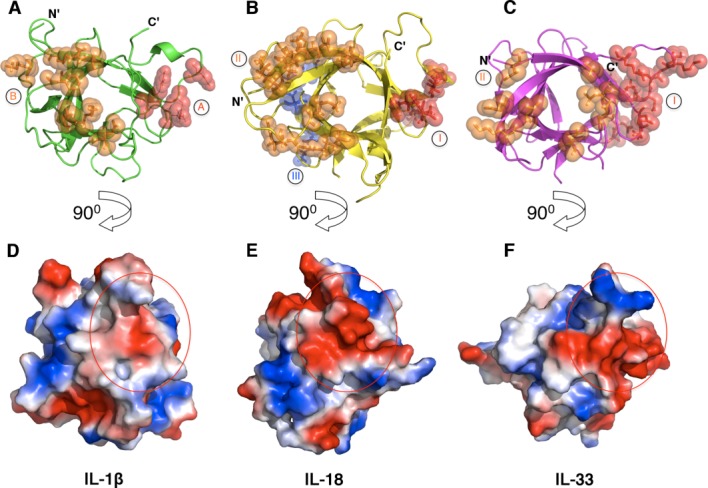

Figure 3.

Receptor binding sites on IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33. Depicted are the secondary structures (top) and the electropotential surfaces (bottom) of IL-1β (A and D, PDB ID 1ITB), IL-18 (B and E, PDB ID 4EKX) and IL-33 (C and F, PDB ID 4KC3). Residues that have been shown to interact with their respective receptors are shown as spheres and colored in red and orange for site A (site I for IL-18 and IL-33) and site B (site II for IL-18 and IL-33), respectively. A third putative receptor-binding site (site III) on IL-18 is shown as blue spheres. The surface area of the binding site A (site I) is indicated as a red circle on each cytokine (bottom).

Crystal structures of two signaling binary complexes within the IL-1 superfamily have been determined to date. These include the binary complex of IL-1β and the ectodomain of IL-1RI, and that of IL-33 and the ectodomain of IL-33Rα [Fig. 4(A,B)]. These binary structures provided key information about the overall architecture of the IL-1 receptor superfamily ectodomain and insights into a common mechanism for the specific recognition of the IL-1 superfamily cytokines by their respective primary receptors.45,46 Overall, the IL-1RI resembles a question mark in shape, wrapping around IL-1β at the center. The first two Ig-like domains [annotated as domain 1 (D1) and domain 2 (D2), respectively] of IL-1RI are connected via an extended 13-residue linker and further tethered together through an inter-domain disulfide bond (C104 of D1-D2 linker with C147 of D2), forming a rigid and compact structure. Domains D2 and D3 are connected via a 5-residue linker, allowing a degree of flexibility between the domains. The architecture of the binary complex of IL-33 and IL-33Rα is remarkably similar to that of IL-1β:IL-1RI receptor complex. Both receptors engage their respective cytokines at two surface locations; named site A and B for IL-1β, site I and II for IL-33. Binding site A (site I) involves a composite surface from the D1/D2 of IL-1RI and IL-33Rα, respectively. The respective binding site A (Site I) are also similar in size, burying 1087 Å2 and 997 Å2 of solvent accessible surface area for IL-1β:IL-1RI and IL-33:IL-33Rα, respectively. Structural and mutagenesis studies identified at least four residues (R11, Q15, H30, and Q32) on IL-1β site A that are critical for receptor binding and signaling, predominantly through polar interactions with main-chain atoms on the receptor [Figs. 3(A) and 4(B)].47,48 In contrast, site I interactions in the IL-33:IL-33Rα binary complex are mainly through side-chain interactions exhibiting a strong electrostatic complementarity between the cytokine and receptor [Figs. 3(C) and 4(C)].45,49 This suggests in part the importance of the site A (site I) in determining the ligand binding specificities.45,49 The interface at binding site B (site II) involves the third Ig-domain (D3) of IL-1RI and IL-33Rα in the respective binary signaling complex [Figs. 3(A,C) and 4(B,C)]. Seven key residues at binding site B of IL-1β were identified (R4, L6, F46, I56, K93, K103, and E105) from the structure and confirmed by mutagenesis studies.46,50 The interactions at IL-1β site B bury ∼1001 Å2 of solvent accessible surface area. Similarly, receptor binding site II on IL-33 is comprised of eight residues (I119, A124, E165, K180, L182, N222, N226, and L268) burying ∼727 Å2 of solvent accessible area as analyzed by the PISA server,51 involving a mixture of hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions.

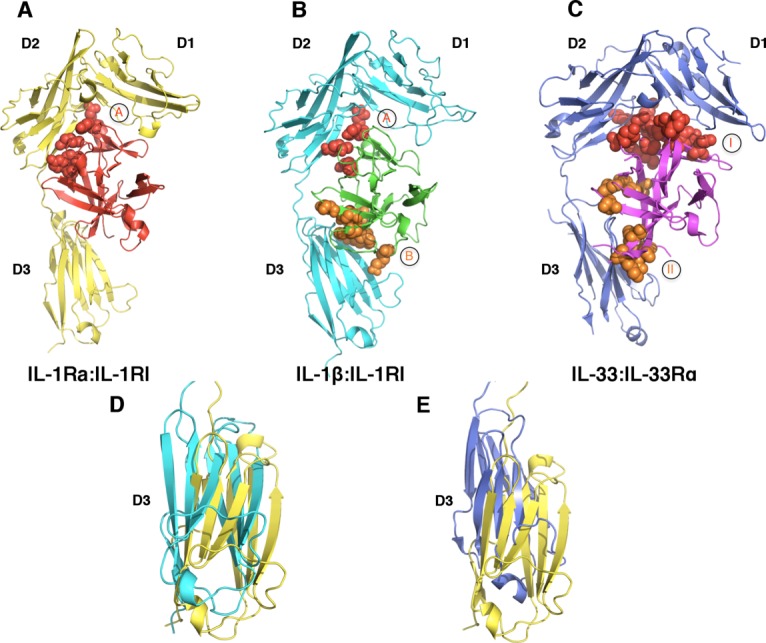

Figure 4.

A common binding mode for receptor:ligand binary complexes. A: IL-1Ra (red) binds IL-1RI (yellow) predominantly at site A, with minimal interactions with the D3 domain of IL-1RI (PDB ID 1IRA). B) The binary complex of IL-1β (green):IL-1RI (cyan) revealed two binding sites, shown as spheres and colored in red (site A) and orange (site B), respectively (PDB ID 1ITB). C) The binary complex of IL-33 (magenta):IL-33Rα (blue) (PDB ID 4KC3). The receptor binding sites I and II on IL-33 are shown as red and orange spheres, respectively. D) and E) Rotation of the D3 domains of IL-1RI in different binary complexes. D) Superimposition of the structures of IL-1Ra:IL-1RI and IL-1β:IL-1RI reveals an approximate 200 rotation between the D3 domains of IL-1RI in the respective structures. E) The D3 domains of the respective receptors in IL-33:IL-33Rα and IL-1Ra:IL-1RI complexes display an approximate 100 rotation. The coloring schemes for the D3 domains of IL-1RI and IL-33Rα are same as above.

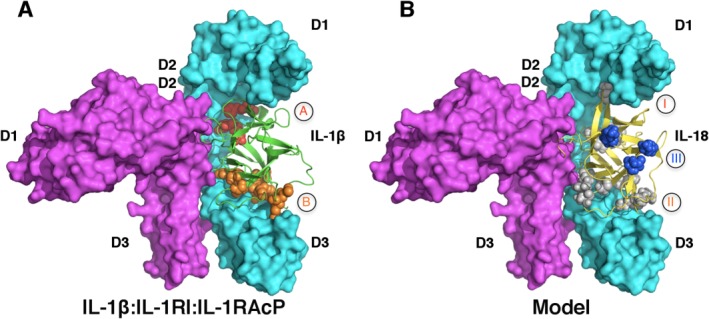

IL-1 ternary complexes: Mechanisms for signal initiation

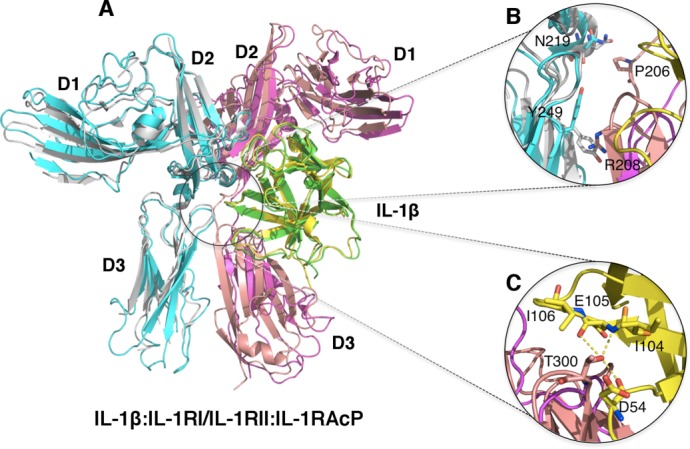

The recent crystal structures of the signaling and nonsignaling IL-1 receptor ternary complexes provided insights into how signaling by IL-1 superfamily of cytokines is modulated at the receptor level. The crystal structure of the nonsignaling ternary complex of IL-1β:IL-1RII:IL-1RAcP provided the first look at the architectural assembly of the ternary complex and the initiation mechanism for IL-1 signaling (Fig. 5).52 As discussed previously, the IL-1RII forms a nonfunctional signaling complex because it lacks the necessary cytoplasmic TIR domain for recruiting intracellular signaling factors. However, it still binds IL-1β with comparable affinity as IL-1RI.21 The binary complex of IL-1β:IL-1RII within this ternary complex closely resembles the structure from the previously determined IL-1β:IL-1RI complex, having an r.m.s.d of only 1.1Å for all aligned backbone Cα atoms and sharing similar buried surface areas. For example, the buried surface areas between site A of IL-1β and the receptors are ∼980 Å2 versus ∼1100 Å2 for IL-1RI and IL-1RII, respectively.52

Figure 5.

Ternary complex structures of IL-1β and its receptors. A) Superimposition of the non-signaling complex [IL-1β (Green):IL-1RII (Magenta):IL-1RAcP (Cyan), PDB ID:3O4O] and the signaling Complex [IL-1β (Yellow):IL-1RI (Pink):IL-1RAcP (Silver) PDB ID:4DEP]. B) Zoom-in view of the D3-D3 domain interactions of IL-1RAcP:IL-1RI and IL-1RAcP:IL-1RII. IL-1β is removed for clarity. The signaling complex showed additional interactions (residues shown in sticks) between IL-1RAcP with IL-1RI due to further rotation of the D3 domain of IL-1RI. These interactions were not observed between IL-1RAcP and IL-1RII in the non-signaling complex. C) Zoom-in view of the additional interactions between IL-1β and IL-1RAcP in the signaling ternary complex. Residue T300 of IL-1RAcP is involved in exquisite interactions with residues D54, I104, E105 and I106 of IL-1β.

Previous studies using in silico docking and SAXS analysis led to the “BACK” and “RIGHT” binding modes for the recruitment of IL-1RAcP to the binary complexes of IL-1β and IL-33 with their primary receptors.49,53 However, the crystal structure of the IL-1β:IL-1RII:IL-1RAcP complex shows that IL-1RAcP adopts the ‘LEFT’ binding mode (Fig. 5).52 IL-1RAcP interacts with the preassembled IL-1β:IL-1RII via a composite binding surface with nearly equal contribution in surface areas from IL-1β and IL-1RII. Specifically, IL-1β uses β-strand 9 (β9) and the loops between β4-β5 and β11-β12 for making contacts with the D2 and D3 Ig domains of IL-1RAcP, burying ∼675 Å2 solvent accessible surface area. These interactions are from a mixture of both charge-charge and van der Waals interactions. IL-1RII and IL-1RAcP directly contact each other mainly through hydrophobic interactions via D2-D2 (V173 and L180 of IL-1RAcP, and L180 of IL-1RII) and D3-D3 (I223, V225 and F248 of IL-1RII, and H226 and H231 of IL-1RAcP) interactions, with a buried surface area of approximately 570 Å2. Interestingly, the D1 Ig-domain of IL-1RAcP does not have any interactions with the binary complex of IL-1β:IL-1RII (Fig. 5).

Subsequently, the crystal structure of the signaling ternary complex of IL-1RI:IL-1β:IL-1RAcP was determined, providing additional insights into the mechanism of IL-1 receptor activation.54 The overall architecture of this productive receptor ternary complex closely resembles the nonsignaling receptor complex, with about 2.1 Å r.m.s.d for all aligned Cα backbone atoms [Fig. 5(A)]. There were essentially no structural changes for IL-1β:IL-1RI upon binding IL-1RAcP, displaying only 1.4 Å r.m.s.d for all backbone Cα atoms when compared with the previously determined binary complex structure.46,54 In addition, the interactions between IL-1β and the accessory receptor were retained in both ternary complex structures. Similar to the observation in the nonsignaling receptor complex structure, the first Ig-domain of IL-1RAcP points away from IL-1β:IL-1RI binary complex and makes no contacts with either IL-1β or IL-1RI. Hydrophobic interactions between IL-1RAcP D2 domain (I135, L180, and I181) and the respective D2 domain of the primary receptor (V160, I165 on IL-1RI; V173 and L180 in IL-1RII) were also conserved. Nevertheless, distinct interactions were observed between IL-1RI and IL-1RAcP in contrast to IL-1RII and IL-1RAcP of the nonsignaling complex. Among the unique interactions found at the IL-1RI:IL-1RAcP interface, contacts were observed between P245, Y234 of IL-1RAcP D3 domain and the glycosylation moiety attached on N216 of IL-1RI D3 domain. As a result, the IL-1RI:IL-1RAcP interface also has a slightly larger buried surface are of 773 Å2, an increase of greater than 200 Å2 with respect to the nonsignaling complex. This increase was largely due to additional interactions in IL-1RI:IL-1RAcP D3-D3 interface and in part a reflection of the further rotation along with a subtle upward shift of the IL-1RI D3 domain, bringing it in closer proximity to the D3 domain of IL-1RAcP [Fig. 5(B)]. This subtle movement of IL-1RI D3 domain promotes additional contacts between the extended linkers connecting the D2-D3 domains and between the D3 domains of the respective receptors. They include the interaction between IL-1RI P206 and IL-1RAcP N219 and a π-cation interaction between IL-1RI R208 and IL-1RAcp Y249 [Fig. 5(B)]. Neither interaction was observed in the nonsignaling structure. It is also significant to observe that residue T300 on the β7-β8 loop of IL-1RI D3 domain is now sandwiched between the β4-β5 loop and β8 of IL-1β making van der Waals and hydrogen bonding interaction with residues D54, I104, E105, and I106 of IL-1β [Fig. 5(C)]. These T300 interactions could be an important feature for the productive signaling complex as they were not observed in the inhibitory IL-1Ra:IL-1RI complex (see below) due to a much shorter β4-β5 loop of IL-1Ra. Interestingly, when this β4-β5 loop together with β11-β12 were replaced with the corresponding loops from IL-1β, IL-1Ra could be converted into a partial agonist.52,55

Whether the mechanism of signal initiation revealed by IL-1R ternary complexes is conserved for all IL-1R superfamily will need further structural studies. For example, putative receptor binding sites on IL-18 have been identified by mutagenesis studies and named as sites I-III [Fig. 3(B)].44 The comparison of the tertiary and primary structures of IL-18 and IL-1β reveals IL-18 binding sites I and II are analogous to the binding sites A and B on IL-1β, which indeed are important for interacting with IL-18Rα as shown by in vitro binding and solution NMR studies.44,56,57 Intriguingly, perturbation at site III on IL-18 by mutagenesis abolished IL-18 biological activities, suggesting this site may be involved in the binding of IL-18Rβ.44 Superimposition of IL-18 onto IL-1β of IL-1β:IL-1RI:IL-1RAcP complex reveals the surface of IL-1β that corresponds to the third putative receptor-binding site on IL18 (site III) is not in contact with either subunit of IL-1 receptor. Therefore IL-18 receptor activation mechanism may not be fully explained by the structure of IL-1R ternary signaling complex (Fig. 6). In addition, it was shown that an antibody against hIL-18, (125-2H) inhibits the formation of the IL-18:IL-18Rα binary complex. Simultaneous binding of 125-2H and IL-18Rα would result in collision of the antibody heavy chain with the D2 domain of the receptor.58 Intriguingly, 125-2H renders the ternary complex nonfunctional without blocking the formation of the high affinity hetero-trimeric receptor complex.33 It was postulated that in order for this binding to occur, IL-18Rβ must induce conformational changes of either IL-18 or the IL-18:IL-18Rα binary complex. These conformational changes will presumably alter the 125-2H epitope region such that the antibody:cytokine:receptors quaternary complex cannot achieve the necessary signaling configuration.58

Figure 6.

Unresolved questions regarding IL-18 subfamily signaling. A) IL-1R signaling ternary complex. IL-1β, IL-1RI and IL-1RAcP are colored in green, cyan and magenta (PDB ID 4DEP). Binding sites A and B are shown in red and orange spheres, respectively. B) A model of IL-18 (yellow):IL-18Rα (cyan):IL-18Rβ (magenta) based on the structure of IL-1β:IL-1RI:IL-1RAcP ternary complex. Putative receptor binding sites I (grey), II (grey) and III (blue) on IL-18 are shown as spheres. Notice site III is not involved in binding of either IL-18R in this model.

Antagonism of IL-1 Signaling by IL-1Ra

The signaling binary complexes of IL-1β:IL-1RI and IL-33:IL-33Rα reveal key information about how respective cytokines are recognized by their corresponding primary receptors. At the same time, the crystal structure of the binary complex of IL-1Ra:IL-1RI provided insights into how IL-1 signaling is antagonized by IL-1Ra [Fig. 4(A)].59 In contrast to the other two signaling binary complex structures, there was only one major binding site, site A, observed at the interface in this inhibitory complex. There were also only minimal interactions observed in the crystal structure between IL-1Ra and the D3 domain of IL-1RI, which was consistent with the mutational data that predicted only one major receptor binding site on IL-1Ra.48 Similar to the observations in the signaling binary complex, the interface at binding site A involves a composite surface from the D1 and D2 domains of IL-1RI. IL-1Ra interacts with IL-1RI mostly through polar main chain interactions, covering a large buried surface area of about 1774 Å2. The inhibitory binary complex failed in recruiting IL-1RAcP, suggesting the D3 domain of IL-1RI plays a critical role for binding IL-1RAcP and signaling. This was further demonstrated by the crystal structure of the signaling ternary complex of IL-1β:IL-1RI:IL-1RAcP, as discussed previously.

Structural comparison of the binary complexes provides insights into the mechanism(s) of IL-1 superfamily receptor antagonism and signaling initiation. Binding site A in the antagonist binary complex displayed a nearly 60% larger binding surface area (1774 Å2 compared with 1087 Å2 or 997 Å2 for IL-1β and IL-33, respectively). This partially explains the higher affinity of IL-1Ra for IL-1RI when compared to IL-1β.21,59 Consequently, the number of cytokine:receptor interactions at site A have also increased in the IL-1Ra:IL-1RI binary complex (hydrogen bonds increased to 19 from 7 and 14 in IL-1β and IL-33, respectively). Therefore, cytokine:receptor interactions at site A appear to be the driving force for affinity and specificity. This was further supported by a recent chimera study on IL-1Ra.21 In this study, Hou et al. engineered a chimeric IL-1Ra by combining the site A surface of IL-1Ra and site B surface of IL-1β into one single molecule. They showed that the D1-D2 tandem fragment (containing site A) of IL-1RI has a much higher affinity to IL-1β and IL-1Ra, in comparison to the D3 domain. In addition, they showed the chimera cytokine behaved like IL-1Ra and not like IL-1β, with much higher binding affinity to IL-1RI than IL-1RII.

Interestingly, none of the cytokines (IL-1β, IL-33, or IL-1Ra) in their respective binary complex undergoes significant structural changes when compared to their uncomplexed structures. However, significant conformational changes were observed from the D3 domain of IL-1RI in the signaling complex (IL-1β:IL-1RI) compared with the inhibitory complex (IL-1Ra:IL-1RI), displaying an ∼20° rotation [Fig. 4(D)]. In the binary complex of IL-33:IL-33Rα, the IL-33Rα D3 domain reveals an ∼10° rotation [Fig. 4(E)]. The conformational differences of the D3 domains from IL-1RI and IL-33Rα suggest their flexibility and dynamics in nature, whose correct orientation upon cytokine binding would be critical for the recruitment of IL-1RAcP in forming the signaling ternary complex. Indeed, SAXS analysis along with Minimal Ensemble Search (MES) of the unbound IL-33Rα revealed it exists in three distinct states of open, half-open, and closed, with respect to the relative orientations of the D3 domain to the D1-D2 tandem domains of IL-33Rα. The crystal structure of the binary IL-33:IL-33Rα complex represents the half-open conformation.45

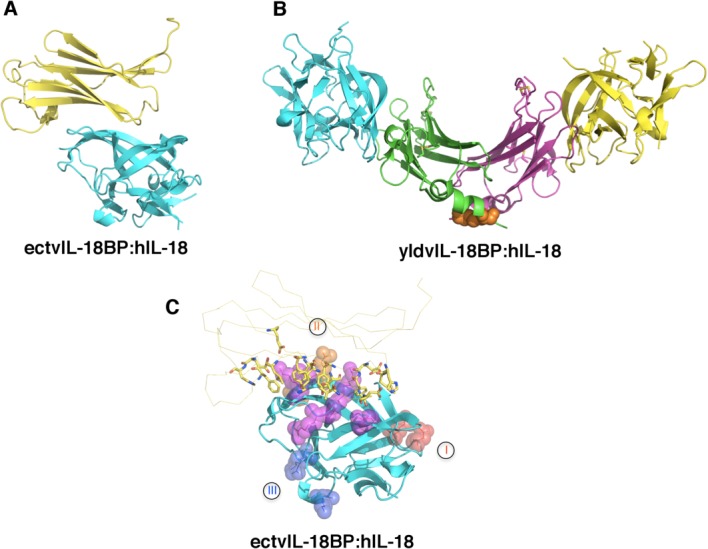

Antagonism of IL-18 Signaling by IL-18BP

Modulation of IL-18 signaling and thus immune response is accomplished in part by IL-18BP. Functional IL-18BPs are not limited to just vertebrates but are also encoded by many poxviruses including Molluscum Contagiosum Virus (MCV) and orthopoxviruses. These viruses include several significant human pathogens such as variola virus that causes smallpox, and monkeypox virus which is an emerging zoonosis causing a smallpox-like disease in humans.60–62 Poxvirus IL-18BPs are highly conserved within their respective species but share only limited homology with human IL-18BP (hIL-18BP). Nevertheless both human and viral IL-18BPs bind to hIL-18 extremely tightly with sub-nanomolar affinity and potently block hIL-18 activity.34,62,63 It has been shown that IL-18BP from vaccinia virus contributes to virulence by down-modulating IL-18 mediated immune responses, suggesting a possible role as a decoy for human immune evasion.61,64 The molecular mechanism by which IL-18BP modulates IL-18 signaling has been elucidated from the two recent high-resolution crystal structures of human IL-18 in complex with two divergent IL-18BPs from ectromelia (ectv) and yaba-like disease virus (yldv) [Figs. 7(A,B)].65,66 The ectvIL-18BP adopts a single Ig-fold and binds IL-18 with nanomolar affinity in a 1:1 stoichiometry. The ectvIL-18BP uses one edge of its β-sandwich for interacting with three surface cavities on IL-18 via extensive hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions, burying as much as 1930 Å2 of solvent accessible surface area. One of the most significant interactions at the complex interface involves residue K53 of IL-18 and the aromatic residue F67 from ectvIL-18BP, through π-cation interaction. Mutation of either residue resulted in a greater than 100-fold decrease in binding affinity as shown from SPR.67–69 Most of the ectvIL-18BP residues observed at the binding interface are conserved in both human and viral homologs, explaining their functional equivalence despite limited sequence homology [Fig. 7(C)]. In contrast to ectvIL-18BP, yldvIL-18BP forms a unique disulfide-bonded homo-dimer and engages IL-18 in a 2:2 stoichiometry [Fig. 7(B)]. Disruption of the dimer interface resulted in a functional monomer, however with a 3-fold decrease in binding affinity. Despite lacking the critical Lys-Phe π-cation interaction, the overall architecture of the yldvIL-18BP:hIL-18 complex is similar to that observed in the ectvIL-18BP:hIL-18 complex. Through structure-based mutagenesis and SPR analysis, a set of contact residues that are unique to the yldvIL-18BP:hIL-18 interface were identified. Nevertheless, despite the extensive divergence, yldvIL-18BP binds to the same surface of hIL-18 used by other IL-18BPs, suggesting that all IL-18BPs, including hIL-18BP, use a conserved inhibitory mechanism by blocking a putative receptor-binding site (site II, analogous to site B of IL-1β) on IL-18 [Figs. 3(B) and 7(C)].57,65,66

Figure 7.

Mechanism of antagonism of IL-18 signaling by IL-18BP. A) The inhibitory complex of ectromelia virus (ectv) IL-18BP (yellow) and human IL-18 (hIL-18, cyan) in a 1:1 stoichiometry (PDB ID 3F62). B) The inhibitory complex of yaba-like disease virus (yldv) IL-18BP (green and magenta) and hIL-18 (yellow and cyan) in a 2:2 stoichiometry (PDB ID 4EKX). There is an intra-molecular disulfide bond within the yldv-IL-18BP homodimer as shown in orange spheres. C) Ectv-IL-18BP blocks the putative receptor-binding site II. Ectv-IL-18BP is shown as yellow ribbon with the key residues at the interface highlighted shown as sticks. Putative receptor binding sites I, II, and III on hIL-18 (cyan) are shown as spheres and colored in red, orange, and blue, respectively. Residues shared for binding with both IL-18Rα and ectvIL-18BP are shown as purple spheres.

Rational Design of Antagonists of IL-1 Superfamily Members

The current strategy for treating inflammatory and autoimmune diseases is to target proteins involved in the initiation event(s) of inflammation or upstream events of the innate immune response. These upstream effector proteins include but are not limited to Cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2) and Caspase-1 (Interleukin-1β Converting Enzyme, ICE), which respond to Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAID) or specific caspase inhibitors, respectively. However, these treatments suffer from side effects such as colitis.70 Agents that specifically block the biological activities of IL-1 or Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) have been used to treat many patients worldwide with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease or psoriasis to reduce the severity of the diseases. Patients treated with anti-TNF-α agents such as Humira and Entanercept or IL-1 blocking therapies (Anakinra) showed considerable improvement of their condition, which suggests that other chronic inflammatory diseases will also benefit from anti-cytokine therapies.71 Additionally, there exist potential therapies that involve the use of antibodies directed against the interface of IL-18 and IL-18Rα or the use of recombinant hIL-18BP, both of which are being tested in clinical trials.72–74

The blockage of IL-1 activity with the recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist appears to be relatively safe (a commercially available version known as Anakinara). Recently, Hou et al. demonstrated an antagonist superior to IL-1Ra could be developed through the use of chimeric cytokine strategy.21 Specifically, by retaining both the binding site A of IL-1Ra and the binding site B of IL-1β, the authors were able to create a specific chimera (93:60) with 85-fold higher affinity for IL-1RI compared to IL-1Ra. In addition, this chimera also maintains bias for IL-1RI over IL-1RII. Comparison of the crystal structures of the binary complexes of chimera:IL-1RI and IL-1β:IL-1RI reveals that all key interactions were indeed preserved in the analogous chimera binding sites A and B at the IL-1RI interface. As a result of binding site grafting, the total buried surface area of the chimera:IL-1RI complex is larger than the respective binary complexes (178 Å2 greater than IL-1β:IL-1RI and 338 Å2 greater than IL-1Ra:IL-1RI).21 The antagonistic effect from the chimera could be partly due to the replacement of β11-β12 loop of IL-1β with that of the IL-1Ra. This loop in IL-1Ra was previously shown to be responsible in part for its antagonism.52 In addition, IL-1β residues (G140, Q141, and D145) that were previously shown to be important for binding IL-1RAcP were also replaced with IL-1Ra residues.21,59,75,76 Specifically, D145 was charge-reversed to a lysine in both the IL-1Ra and the 93:60 chimera. Although not presented in the chimera study, it is likely the 93:60 chimera will fail to recruit IL-1RAcP because of the substitutions of the β11-β12 loop and the residues around residue D145 of IL-1β.

Conclusions

The IL-1 superfamily of cytokines plays critical roles in immune response and autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. The structural biology research on IL-1 superfamily signaling in the past two decades have provided extensive information on not only the architectures of the cytokines and receptors but also the molecular principles that dictate their specific binding and recognition. The structural and functional data have provided key insights into the mechanism by which the IL-1 superfamily signaling is initiated and regulated. These insights provide great opportunity for rational development of inhibitors against specific cytokines for treating inflammatory diseases. While many questions still remain regarding the mechanism by which the signal of cytokine:receptor binding transmits across the membrane and triggers intracellular signaling.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to investigators whose relevant work was not cited in this review due to space limitations or our oversight. The authors declare no competing financial interests or conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- BP

binding protein

- IL

Interleukin (IL)

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TIR

toll/interleukin-1 receptor

References

- Dinarello C, Arend W, Sims J, Smith D, Blumberg H, O'Neill L, Goldbach-Mansky R, Pizarro T, Hoffman H, Bufler P, Nold M, Ghezzi P, Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Boraschi D, Rubartelli A, Netea M, van der Meer J, Joosten L, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Donath M, Lewis E, Pfeilschifter J, Martin M, Kracht M, Muehl H, Novick D, Lukic M, Conti B, Solinger A, Kelk P, van de Veerdonk F, Gabel C. IL-1 family nomenclature. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:973. doi: 10.1038/ni1110-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend WP, Palmer G, Gabay C. IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 families of cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:20–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill LA. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: 10 years of progress. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heguy A, Baldari CT, Macchia G, Telford JL, Melli M. Amino acids conserved in interleukin-1 receptors (IL-1Rs) and the Drosophila toll protein are essential for IL-1R signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2605–2609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon PG, Allen RL, Rich T. Primitive Toll signalling: bugs, flies, worms and man. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:63–66. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(00)01800-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botos I, Segal DM, Davies DR. The structural biology of Toll-like receptors. Structure. 2011;19:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie A, O'Neill LA. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: signal generators for pro-inflammatory interleukins and microbial products. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:508–514. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Overview of the interleukin-1 family of ligands and receptors. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims JE, Smith DE. The IL-1 family: regulators of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nri2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandinova A, Soldi R, Graziani I, Bagala C, Bellum S, Landriscina M, Tarantini F, Prudovsky I, Maciag T. S100A13 mediates the copper-dependent stress-induced release of IL-1alpha from both human U937 and murine NIH 3T3 cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2687–2696. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudovsky I, Mandinova A, Soldi R, Bagala C, Graziani I, Landriscina M, Tarantini F, Duarte M, Bellum S, Doherty H, Maciag T. The non-classical export routes: FGF1 and IL-1alpha point the way. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4871–4881. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurgin V, Novick D, Werman A, Dinarello CA, Rubinstein M. Antiviral and immunoregulatory activities of IFN-gamma depend on constitutively expressed IL-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5044–5049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611608104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrei C, Margiocco P, Poggi A, Lotti LV, Torrisi MR, Rubartelli A. Phospholipases C and A2 control lysosome-mediated IL-1 beta secretion: implications for inflammatory processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9745–9750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308558101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrei C, Dazzi C, Lotti L, Torrisi MR, Chimini G, Rubartelli A. The secretory route of the leaderless protein interleukin 1beta involves exocytosis of endolysosome-related vesicles. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1463–1475. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.5.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Franchi L, Nunez G, Dubyak GR. Nonclassical IL-1 beta secretion stimulated by P2X7 receptors is dependent on inflammasome activation and correlated with exosome release in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;179:1913–1925. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims JE, March CJ, Cosman D, Widmer MB, MacDonald HR, McMahan CJ, Grubin CE, Wignall JM, Jackson JL, Call SM, D Friend, AR Alpert, S Gillis, DL Urdal, SK Dower. cDNA expression cloning of the IL-1 receptor, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Science. 1988;241:585–589. doi: 10.1126/science.2969618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korherr C, Hofmeister R, Wesche H, Falk W. A critical role for interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein in interleukin-1 signaling. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:262–267. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeder SA, Nunes P, Kwee L, Labow M, Chizzonite RA, Ju G. Molecular cloning and characterization of a second subunit of the interleukin 1 receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13757–13765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J, Townson SA, Kovalchin JT, Masci A, Kiner O, Shu Y, King BM, Schirmer E, Golden K, Thomas C, Garcia KC, Zarbis-Papastoitsis G, Furfine ES, Barnes TM. Design of a superior cytokine antagonist for topical ophthalmic use. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:3913–3918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217996110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Okamura H. Interleukin-18 is a unique cytokine that stimulates both Th1 and Th2 responses depending on its cytokine milieu. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12:53–71. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(00)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boraschi D, Dinarello CA. IL-18 in autoimmunity: review. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:224–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boraschi D, Tagliabue A. The interleukin-1 receptor family. Vitam Horm. 2006;74:229–254. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(06)74009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA, Fantuzzi G. Interleukin-18 and host defense against infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:S370–S384. doi: 10.1086/374751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan JF, Timans JC, Kastelein RA. A newly defined interleukin-1? Nature. 1996;379:596. doi: 10.1038/379591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H, Tsutsui H, Komatsu T, Yutsudo M, Hakura A, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Okura T, Nukada Y, Hattori K, Akita K, Namba M, Tanabe F, Konishi K, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN gamma production by T cells. Nature. 1995;378:88–91. doi: 10.1038/378088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Shibuya K, Mui A, Zonin F, Murphy E, Sana T, Hartley SB, Menon S, Kastelein R, Bazan F, O'Garra A. IGIF does not drive Th1 development but synergizes with IL-12 for interferon-gamma production and activates IRAK and NFkappaB. Immunity. 1997;7:571–581. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Kato S, Oizumi K, Kinoshita M, Inoue Y, Hoshino K, Akira S, McKenzie AN, Young HA, Hoshino T. Interleukin 18 (IL-18) in synergy with IL-2 induces lethal lung injury in mice: a potential role for cytokines, chemokines, and natural killer cells in the pathogenesis of interstitial pneumonia. Blood. 2002;99:1289–1298. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira M, Ahn HJ, Park WR, Gao P, Tomura M, Park CS, Hamaoka T, Ohta T, Kurimoto M, Fujiwara H. Synergy of IL-12 and IL-18 for IFN-gamma gene expression: IL-12-induced STAT4 contributes to IFN-gamma promoter activation by up-regulating the binding activity of IL-18-induced activator protein 1. J Immunol. 2002;168:1146–1153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y. Activation of interferon-γ inducing factor mediated by interleukin-1β converting enzyme. Science. 1997;275:206–209. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debets R, Timans JC, Churakowa T, Zurawski S, de Waal Malefyt R, Moore KW, Abrams JS, O'Garra A, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA. IL-18 receptors, their role in ligand binding and function: anti-IL-1RAcPL antibody, a potent antagonist of IL-18. J Immunol. 2000;165:4950–4956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Sakorafas P, Miller R, McCarthy D, Scesney S, Dixon R, Ghayur T. IL-18 receptor beta-induced changes in the presentation of IL-18 binding sites affect ligand binding and signal transduction. J Immunol. 2003;170:5571–5577. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Eisenstein M, Reznikov L, Fantuzzi G, Novick D, Rubinstein M, Dinarello CA. Structural requirements of six naturally occuring isoforms of the IL-18 binding protein to inhibit IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1190–1195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick D, Kim S, Fantuzzi G, Reznokov LL, Dinarello CA, Rubinstein M. Interleukin-18 binding protein: A novel modulator of the Th1 cutokine response. Immunity. 1999;10:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick D, Schwartsburd B, Pinkus R, Suissa D, Belzer I, Sthoeger Z, Keane WF, Chvatchko Y, Kim SH, Fantuzzi G, Dinarello GA, Rubinstein M. A novel IL-18BP ELISA shows elevated serum IL-18BP in sepsis and extensive decrease of free IL-18. Cytokine. 2001;14:334–342. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Hanning CR, Brigham-Burke MR, Rieman DJ, Lehr R, Khandekar S, Kirkpatrick RB, Scott GF, Lee JC, Lynch FJ, Gao W, Gambotto A, Lotze MT. Interleukin-1F7B (IL-1H4/IL-1F7) is processed by caspase-1 and mature IL-1F7B binds to the IL-18 receptor but does not induce IFN-gamma production. Cytokine. 2002;18:61–71. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.0873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G, Risser P, Mao W, Baldwin DT, Zhong AW, Filvaroff E, Yansura D, Lewis L, Eigenbrot C, Henzel WJ, Vandlen R. IL-1H, an interleukin 1-related protein that binds IL-18 receptor/IL-1Rrp. Cytokine. 2001;13:1–7. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrancais E, Cayrol C. Mechanisms of IL-33 processing and secretion: differences and similarities between IL-1 family members. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2012;23:120–127. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2012.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrancais E, Roga S, Gautier V, Gonzalez-de-Peredo A, Monsarrat B, Girard JP, Cayrol C. IL-33 is processed into mature bioactive forms by neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:1673–1678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115884109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li X, Gorman DM, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Huber M, Kollewe C, Bischoff SC, Falk W, Martin MU. IL-1 receptor accessory protein is essential for IL-33-induced activation of T lymphocytes and mast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18660–18665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705939104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chackerian AA, Oldham ER, Murphy EE, Schmitz J, Pflanz S, Kastelein RA. IL-1 receptor accessory protein and ST2 comprise the IL-33 receptor complex. J Immunol. 2007;179:2551–2555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Z, Jee J, Shikano H, Mishima M, Ohki I, Ohnishi H, Li A, Hashimoto K, Matsukuma E, Omoya K, Yamamoto Y, Yoneda T, Hara T, Kondo N, Shirakawa M. The structure and binding mode of interleukin-18. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:966–971. doi: 10.1038/nsb993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Hammel M, He Y, Tainer JA, Jeng US, Zhang L, Wang S, Wang X. Structural insights into the interaction of IL-33 with its receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:14918–14923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308651110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigers GPA, Andersen LA, Caffes P, Brandhuber BJ. Crystal structure of the type-1 interleukin-1 receptor comlexed with interleukin-1beta. Nature. 1997;386:190–194. doi: 10.1038/386190a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald HR, Wingfield P, Schmeissner U, Shaw A, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Point mutations of human interleukin-1 with decreased receptor binding affinity. FEBS Lett. 1986;209:295–298. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RJ, Bray J, Childs JD, Vigers GP, Brandhuber BJ, Skalicky JJ, Thompson RC, Eisenberg SP. Mapping receptor binding sites in interleukin (IL)−1 receptor antagonist and IL-1 beta by site-directed mutagenesis. Identification of a single site in IL-1ra and two sites in IL-1 beta. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11477–11483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingel A, Weiss TM, Neibuhr M, Pan B, Appleton BA, Weisman C, Bazan JF, Fairbrother WJ. Structure of IL-33 and its interaction with the ST2 and IL-1Racp Receptors—insight into heterotrimeric IL-1 Signaling Cascade. Structure. 2009;17:1398–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labriola-Tompkins E, Chandran C, Kaffka KL, Biondi D, Graves BJ, Hatada M, Madison VS, Karas J, Kilian PL, Ju G. Identification of the discontinuous binding site in human interleukin 1 beta for the type I interleukin 1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11182–11186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Zhang S, Li L, Liu X, Mei K, Wang X. Structural insights into the assembly and activation of IL-1beta with its receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:905–911. doi: 10.1038/ni.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadio R, Frigimelica E, Bossu P, Neumann D, Martin MU, Tagliabue A, Boraschi D. Model of interaction of the IL-1 receptor accessory protein IL-1RAcP with the IL-1beta/IL-1R(I) complex. FEBS Lett. 2001;499:65–68. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02515-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Bazan JF, Garcia KC. Structure of the activating IL-1 receptor signaling complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:455–457. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeder SA, Varnell T, Powers G, Lombard-Gillooly K, Shuster D, McIntyre KW, Ryan DE, Levin W, Madison V, Ju G. Insertion of a structural domain of interleukin (IL)−1 beta confers agonist activity to the IL-1 receptor antagonist. Implications for IL-1 bioactivity. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22460–22466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Azam T, Novick D, Yoon DY, Reznikov LL, Bufler P, Rubinstein M, Dinarello CA. Identification of amino acid residues critical for biological activity in human interleukin-18. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10998–11003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Leman M, Xiang X. Variola virus IL-18 binding protein interacts with three human IL-18 residues that are part of a binding site for human IL-18 receptor alpha subunit. Virology. 2007;358:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argiriadi MA, Xiang T, Wu C, Ghayur T, Borhani DW. Unusual water-mediated antigenic recognition of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-18. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24478–24489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreuder H, Tardif C, Trump-Kallmeyer S, Soffienti A, Sarubbi E, Akeson A, Bowlin T, Yanofsky S, Barret RW. A new cytokine-receptor binding mode revealed by the crystal structure of the IL-1 receptor with an antagonist. Nature. 1997;386:194–200. doi: 10.1038/386194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker S, Nuara A, Buller RM, Schultz DA. Human monkeypox: an emerging zoonotic disease. Future Microbiol. 2007;2:17–34. doi: 10.2217/17460913.2.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born TL, Morrison LA, Esteban DJ, VandenBos T, Thebeau LG, Chen N, Spriggs MK, Sims JE, Buller RML. A poxvirus protein that binds to and inactivates IL-18, and inhibits NK cell response. J Immunol. 2000;164:3246–3254. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Moss B. IL-18 binding and inhibition of interferon gamma induction by human poxvirus-encoded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11537–11542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderara S, Xiang Y, Moss B. Orthopoxvirus IL-18 binding proteins: affinities and antagonist activities. Virology. 2001;279:22–26. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading PC, Smith GL. Vaccinia virus interleukin-18-binding protein promotes virulence by reducing gamma interferon production and natural killer and T-cell activity. J Virol. 2003;77:9960–9968. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.9960-9968.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm B, Meng X, Wang Z, Xiang Y, Deng J. A unique bivalent binding and inhibition mechanism by the yatapoxvirus interleukin 18 binding protein. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002876. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm B, Meng X, Li Y, Xiang Y, Deng J. Structural basis for antagonism of human interleukin 18 by poxvirus interleukin 18-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20711–20715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809086106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban DJ, Buller RM. Identification of residues in an orthopoxvirus interleukin-18 binding protein involved in ligand binding and species specificity. Virology. 2004;323:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Moss B. Determination of the functional epitopes of human interleukin-18 binding protein by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17380–17386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Moss B. Correspondence of the functional epitopes of poxvirus and human interleukin-18-binding proteins. J Virol. 2001;75:9947–9954. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9947-9954.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter BK, Asfaha S, Buret A, Sharkey KA, Wallace JL. Exacerbation of inflammation-associated colonic injury in rat through inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2076. doi: 10.1172/JCI119013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Anti-cytokine therapeutics and infections. Vaccine. 2003;21:S24–S34. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA, Novick D, Kim S, Kaplanski G. Interleukin-18 and IL-18 binding orotein. Front Immunol. 2013;4:289. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Kato Z, Ohnishi H, Tochio H, Shirakawa M, Kondo N. Expression, purification and structural analysis of human IL-18 binding protein: a potent therapeutic molecule for allergy. Allergology Intl. 2008;57:367–376. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.O-08-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plitz TS-MP, Satho M, Herren S, Waltzinger C, de Carvalho Bittencourt M, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Chvatchko Y. IL-18 binding protein protects against contact hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 2003;3:1164–1171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boraschi D, Bossu P, Macchia G, Ruggiero P, Tagliabue A. Structure-function relationship in the IL-1 family. Front Biosci. 1996;1:d270–308. doi: 10.2741/a132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju G, Labriola-Tompkins E, Campen CA, Benjamin WR, Karas J, Plocinski J, Biondi D, Kaffka KL, Kilian PL, Eisenberg SP, et al. Conversion of the interleukin 1 receptor antagonist into an agonist by site-specific mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2658–2662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]