Abstract

Directors in substance use treatment programs are increasingly required to respond to external economic and socio-political pressures. Leadership practices that promote innovation can help offset these challenges. Using focus groups, factor analysis, and validation instruments, the current study developed and established psychometrics for the Survey of Transformational Leadership. In 2008, clinical directors were evaluated on leadership practices by 214 counselors within 57 programs in four U.S. regions. Nine themes emerged: integrity, sensible risk, demonstrates innovation, encourages innovation, inspirational motivation, supports others, develops others, delegates tasks, and expects excellence. Study implications, limitations and suggested future directions are discussed. Funding from NIDA.

Keywords: substance use, transformational leadership, scale development, scale validation

Increasingly, organizations providing behavioral health services are required to change practices in response to external economic and socio-political pressures. The substance use treatment field, is plagued with high program closure rates (Wells, Lemak, & D’Aunno, 2005), exogenous factors negatively affecting staff satisfaction and retention (e.g., rise in managed care; Roman, Ducharme, & Knudsen, 2006), and decreased funding (Kimberly & McLellan, 2006), all of which challenge clinical management. Furthermore, state and federal funding sources are mandating the implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs). In response, program administrators are searching for and implementing new and alternative approaches to optimize resource utilization. To secure organizational health and viability, leaders must promote a culture of change that supports creativity and involves staff in decision-making.

While some directors embrace and initiate change, welcoming opportunities to re-invent aspects of the organization, others may resist. Often fixed norms and beliefs that conflict with new practices and the lack of training, skills, and motivation impedes the implementation of new interventions (D’Aunno, 2006). Subsequently, interest in spotlighting director development and change management is growing within the US, as leadership training is being offered by national agencies to professional members of the substance use treatment community (e.g., ATTC Leadership Institute, http://www.nattc.org/leaderInst/index.htm; NIATx Executive Leadership Academy, https://www.niatx.net/Content/ContentPage.aspx?NID=353).

Directors serve as visionaries and change agents, and are central in promoting organizational change (Beer, 1980; Flynn & Simpson, in press; Howard, 2001). Transformational” leadership approaches have been successful in promoting change (Herold, Fedor, Caldwell, & Lui, 2008) within a variety of organizations, and have important implications for substance use treatment programs. Importantly, transformational leadership can be taught and learned at all management levels within an organization (Bass, 1999; Bass & Avolio, 1990) and has positive effects within a variety of organizational settings (Bass, 1997). However, there are organizational contingencies that could affect the likelihood of transformational leadership within certain situations. For instance, transformational leadership has more of an impact within environments that are unstable and that support goal progress with intrinsic rewards (Howell, 1992). Given the turbulent nature of the substance use field and the lack of opportunity for monetary compensation, transformational leadership has great potential to impact organizational improvement efforts within the treatment field.

Burns (1978) first conceptualized transformational leaders as those who mobilize their efforts to reform organizations, in part by raising followers’ consciousness beyond personal interests to be more in line with organizational goals and vision. Interactive and highly participatory encounters among all members of a team are key ingredients. Through these interactions, visions emerge, consensus is built, plans are discussed, and potential roadblocks are explored, increasing buy-in and accountability among team members. Leaders influence the process by promoting intellectual stimulation, inspiring motivation, and taking each member’s needs into consideration (Bass, 1985).

The impact that transformational leadership has on members of an organization can be best examined by comparing it to transactional leadership, where leaders “approach followers with an eye to exchanging one thing for another” (Burns, 1978, p. 3), for instance exchanging work on a project for a raise in compensation. Instead, a transformational leader mobilizes their followers toward reform by an appeal to values and emotions. Maslow’s (1954) hierarchy of needs serves as an analogy for the impact that these two leadership strategies can have on followers. Transactional leadership focuses on issues lower in Maslow’s hierarchy, such as concerns for personal security and exchange of work for compensation, whereas transformational leadership focuses more on self-actualization (i.e., a desire for the betterment of the team or organization).

Thus transformational approaches to leadership have a wide range of potential benefits. At the organization level, transformational leadership practices can produce strategic organizational change (Waldman, Javidan, & Varella, 2004). Perceived transformational actions have also been shown to alter staff perceptions of EBPs in mental health service settings (Aarons, 2006), increase staff satisfaction (Judge & Piccolo, 2004), reduce stress and burnout (Seltzer, Numerof, & Bass, 1989), and reduce turnover intentions (Bycio, Hackett, & Allen, 1995; Martin & Epitropaki, 2001). While limited research has linked transformational leadership directly with client outcomes (such as treatment engagement) staff perceptions have implications for clients. For instance, lower staff burnout has been associated with higher counselor rapport ratings among clients within substance use treatment organizations (Garner & Knight, 2007).

Currently there are a number of instruments available that measure transformational leadership (e.g., Bass & Avolio, 1995). However, some important components (such as empowerment), are not routinely assessed. Additionally, most existing instruments include scales with only one or two marker items that reflect important themes within a core component. This approach works well when assessing a global construct of core transformational components, but is inadequate when examining components in greater detail for self-assessment and training purposes. Furthermore, the most commonly used and most comprehensive measures of transformational leadership (such as the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire; Bass & Avolio, 1995) are available for a fee. Consequently, there is a need for a non-commercial instrument that assesses fundamental components of transformational leadership strategies, and that can be used in treatment programs with limited resources.

To date, there is little known about the practice of transformational leadership within substance use treatment organizations. Given the rapid changes occurring within the field, it has become clear that there is a need for leadership that will promote innovation, challenge the status quo, and empower followers to take on tasks and find creative solutions. While it is likely that administrators in some treatment programs utilize transformational approaches, it is also likely that many do not due to organizational and financial barriers. Yet these organizations have much to gain through transformational practices such as creative problem-solving and engaging/developing existing staff in the process. To advance the practice and process of transformational strategies in treatment organizations, a reliable and valid transformational leadership survey was developed for use free of charge.

Survey of Transformational Leadership (STL)

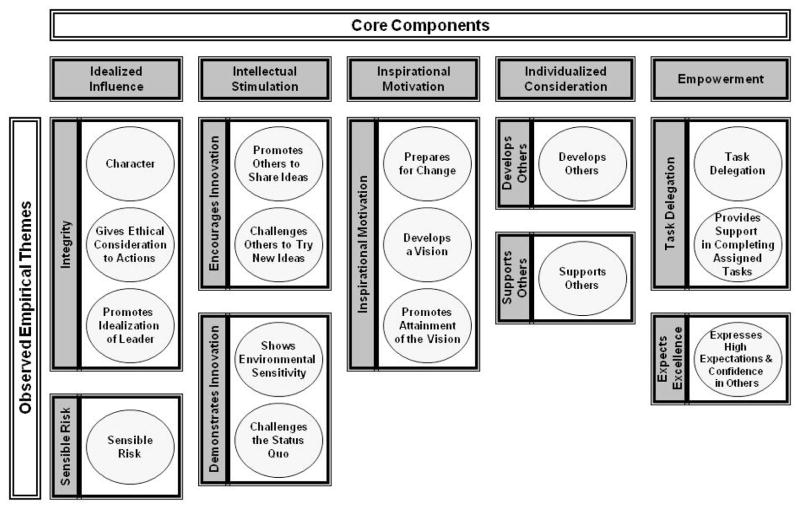

The Survey of Transformational Leadership (STL) is a comprehensive assessment instrument that reflects approaches to the conceptualization and measurement of transformational practices. The STL examines five core components, four that are traditionally conceptualized as transformational domains (i.e., idealized influence, intellectual stimulation, inspirational motivation, and individualized consideration), plus one that is measured less frequently (empowerment). Conceptual themes are examined within each of these five core components by considering specific leader practices included in a variety of other instruments. For instance, idealized influence includes themes of character, sensible risk-taking, ethical consideration, and idealization of leader. Including items that address each theme allows for differentiation between leaders based on the use of specific strategies. Figure 1 depicts the five core components and their corresponding conceptual themes.

Figure 1.

Core components and themes of transformational leadership.

Note: Circles represent proposed conceptual themes within observed empirical themes.

Idealized influence

Evidence suggests that having idealized influence evokes less stress and burnout within the workplace (Seltzer et al., 1989). A leader’s model character includes expression of self-determination (House, 1977), honesty, and openness (Alimo-Metcalfe & Alban-Metcalfe, 2005), as well as sensible risk-taking when there is not a 100% likelihood of success (Conger & Kanungo, 1994; Sashkin & Sashkin, 2003). Researchers have also called for the inclusion of whether the leader emphasizes the importance of subordinates’ beliefs and acts consistently with them (Bass & Avolio, 1990). The ability to gain the trust of followers, beyond their respect and pride, has been suggested as a feature of idealized influence (Sashkin & Sashkin, 2003; Yukl, 1999).

Intellectual stimulation

Creating intellectual stimulation is another important core component of transformational leadership. Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, and Fetter (1990) emphasize the importance of encouraging followers to challenge their own traditional ways of completing tasks by trying new things and including staff in the process of finding and sharing solutions to common issues. Showing environmental sensitivity by evaluating the environment opportunities within and outside of the organization (Conger & Kanungo, 1994), is also considered important in stimulating new ideas. Furthermore, maintaining the status quo by discouraging creative thinking is more likely to disempower and stress staff (Bass, 1998).

Inspirational motivation

One of the most salient characteristics of transformational leaders is their ability to establish a vision which offers followers meaning and challenge to their individual organizational tasks (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Preparing followers for change and expressing optimism, enthusiasm, and confidence in reaching the vision are a necessary part of promoting a vision and attaining desired goals (Alimo-Metcalfe & Alban-Metcalfe, 2005; Avolio & Bass, 2004). Most successful visions are clear, strategically planned, and feasible – stimulating a common purpose, raising self-esteem in followers, and allowing them to more readily participate in their pursuit (Hackman, 1986; Kotter & Heskett, 1992; Raelin, 1989). Transformational leadership also involves organizational members in the process of developing and pursuing shared visions – which are not only more successful (Tichy & Devanna, 1986), but also result in fewer reports of employee intentions to leave the job (Vancouver & Schmitt, 1991), more commitment to the leader (King & Anderson, 1990), and enhancements in group performance (Barling, Louglin, & Kelloway, 2002). Transformational leaders can show their own commitment, and compel followers to embrace a vision by actively modeling the values that underlie the mission (Bennis & Nanus, 1985) and by building support for the organizational goals from outside sources (Yukl, 2002).

Individualized consideration

Developmental leadership (e.g. providing professional development opportunities) is associated with improvement of skills and expression of self-efficacy (Yukl, 1999), as well as with enhancement of commitment and task competency (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Likewise, supportive leadership (e.g., respecting followers as individuals) promotes less negative reactions to organizational change (Rafferty & Griffin, 2006).

Empowerment

While empowering practices that help link followers’ decisions to their self-concept (e.g., Yukl, 1999) are viewed by some as part of transformational leadership, it is not consistently included in common conceptualizations and assessments. In an effort to conceptualize transformational leadership as both participatory and directive, Bass (1996) excluded empowerment as a core component. Yukl (1999) contends that empowering practices including consulting, delegating, and sharing of pertinent information help link decisions to followers’ self worth thus creating an ownership of common goals. Leaders that empower followers intentionally delegate tasks that are important (Peters & Waterman, 1982) and meaningful (Bennis & Nanus, 1985; McClelland, 1975; Tichy & Devanna, 1986), and that enhance learning to facilitate growth within the organization (Kuhnert & Lewis, 1987). They set high performance expectations for their followers and display confidence that followers can perform and complete tasks (Podsakoff et al., 1990). Additionally, an empowering leader shares power with and conveys support to followers. Once achieved, empowerment helps to promote positive organizational outcomes, including higher innovation, organizational learning, and less turnover (Spreizer, 1995).

Method

In order to establish the validity and reliability of the STL, two field studies were conducted: (1) a qualitative appraisal (i.e., focus groups) to refine the instrument and (2) a quantitative evaluation designed to examine the psychometric properties both as separate components (i.e., first-order factors) and as a global measure of transformational leadership (i.e., second-order factor). All participation in the studies was voluntary and the research protocols were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Study 1: Focus Group Evaluation

Focus groups were conducted to evaluate item wording and utility of the STL for use in substance use programs. Three focus groups were held which included counselors and directors from two Gulf Coast agencies within outpatient substance use treatment. Counseling staff and directors were kept separate to ensure confidentiality of comments.

Participants received information on study aims and confidentiality. Staff members and directors provided (1) feedback on the utility of the STL, (2) information on which job positions (i.e., program versus clinical director) generally perform the leadership functions addressed in the survey, (3) suggestions for clarifying survey item wording, and (4) identification of additional leader behaviors that should be added to the survey.

The focus group members recommended designating the clinical director (i.e., the individual with direct supervision of counselors) as the primary person to be rated rather than the program director. There was consensus that program directors were more often responsible for operations management than for clinical supervision. However, some program directors serve in multiple roles, including clinical director. Fourteen items were identified as needing potential revision, most involving minor wording changes. Four items included the term “risk,” based on common terminology found in transformational leadership literature (e.g., Conger & Kanungo, 1987). However, the term “risk” could be perceived within the treatment field as having negative connotations, alluding to ethical violations and “risky” behavior associated with substance use. Subsequently, these four items were changed to state either “appropriate risk” or “personal chances.” Participants also suggested adding items reflecting: modeling appropriate behaviors and including staff in developing implementation plans for new program practices. The general consensus among administrators and staff reflected a need to assess and promote improvement of leadership practices within the field and that the STL would be a good tool to meet these requirements.

Study 2: Scale Dimensionality, Internal Consistency, and Validity

Participants

Counselors with direct client contact were surveyed from outpatient substance use treatment programs currently involved in the Treatment Costs and Organizational Monitoring (TCOM; see Broome, Flynn, Knight, & Simpson, 2007) project. Programs were located in four geographic regions of the United States including the Northwest, the Gulf Coast, the Southeast, and the Great Lakes.

Eighty-seven programs were contacted and asked to participate. Sixteen (18%) chose not to participate due to previous commitments or recent staffing changes. Of the 71 remaining programs, data from four were consolidated with sibling programs within their same parent organization, due to an overlap in staff and leadership responsibilities between sites. An additional 10 programs (11%), although agreeing to participate initially, were unable to allocate time for staff to complete surveys. Therefore, a total of 57 programs participated in the current study, accounting for 70% of the eligible programs.

In total, 213 staff and 57 leaders were represented in the current study, representing a 62% and 86% response rate for staff and leaders respectively. Of the participating staff most were female, Caucasian, college educated, and served a minimum of 3 years within the field and at least one year in their current position. Staff and leaders averaged 39 and 48 years of age, respectively. A majority of the staff perceived themselves to be at a lower rank than their leader and their leader to be upper management (see Table 1). A majority (53%) of the leaders were rated by staff employed in treatment settings that offered a mixture of regular and intensive outpatient services. Eighty-seven percent operated as part of a larger “parent” organization (e.g., a central administrative unit maintaining several facilities in the community) and had an average staff size of approximately 7 counselors. A typical program served on average 53% (SD =.34%) criminal justice-referred clients, 22% (SD = 25%) comorbid or “dual diagnosis” clients and 38% (SD = 20%) female clients.

Table 1.

Staff and Leader Characteristics

| Characteristics | Counselors (N=213) | Clinical Directors (N=52) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 63.50 | 61.78 |

| White | 73.13 | 77.55 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 65.24 | 80.77 |

| Certified or licensed in substance use | 61.46 | 90.38 |

| At least 3 years in substance use field | 65.24 | 96.15 |

| At least 1 year in present position | 70.62 | 94.23 |

| Average age | 39.32 (SD = 11.77) | 48.41 (SD = 9.98) |

| Staff perceptions of leader | ||

| Lower relative rank to leader | 82.99 | -- |

| Upper management | 51.56 | -- |

| Middle management | 41.15 | -- |

Procedure

Program primary contacts were reached via email and given information regarding the study aims, data collection procedures, and incentives (described below). Once an organization agreed to participate and the number of staff members with direct client contact was determined, the corresponding number of survey packets was mailed to the facility. The packet contained a consent form, a program-specific cover letter, the leadership questionnaire (average completion time of 30 minutes), and a postage-paid envelope to return the completed survey. Owing to variation in job titles between organizations and based on focus group feedback, instead of asking participants to rate their clinical director, program contacts were asked to identify by title, the position that has “direct supervision of clinicians/counselors.” This program-specific job title was printed on the staff questionnaire cover letter. Clinical directors were also asked to complete the packet, but only their background information was used in the present study. Each participant who completed the packet was entered into a raffle for a chance to win one of four $25 or one of two $50 gift certificates awarded by region.

Measures

An assessment battery consisting of the Survey of Transformational Leadership (STL), as well as selected items from the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), Attributes of Leader Behavior Questionnaire (ALBQ), and Survey of Organizational Functioning (SOF) were used to develop and validate the new transformational leadership tool. In completing the STL, MLQ, and ALBQ, staff members responded to a 5-point rating scale with the stem stating, “The person I am rating” performs a certain leadership practice ranging from “not at all” (0) to “frequently, if not always” (4). Items phrased in the negative were reverse coded for analysis. Following factor analyses, composite measures for each theme were created by taking the average score for the items within each theme. Scale scores were then multiplied by 10, and ranged from 0 to 40 to allow for ease in clinical feedback or interpretation of leadership ratings. A list of instruments and scales is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of Instruments, Scales, and Number of Items

| Instrument | Scale and Number of Items |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Survey of Transformational Leadership (STL) |

Idealized Influence: character – 4, sensible risk – 4, gives ethical consideration to actions – 5, promotes idealization of leader – 6 Intellectual Stimulation: promotes others to share ideas – 4, challenges others to try new ideas – 4, shows environmental sensitivity – 4, challenges the status quo – 4 Inspirational Motivation: prepares for change – 5, develops a vision – 11, promotes attainment of the vision – 7 Individualized Consideration: develops others – 4, supports others – 4 Empowerment: task delegation – 7, expresses high performance expectations along with confidence in others – 4, provides support in accomplishing assigned tasks – 6 |

|

| |

| Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) | Idealized Influence – 8, Inspirational Motivation – 4, Intellectual Stimulation – 4, Individualized Consideration – 4 |

|

| |

| Attributes of Leader Behavior Questionnaire (ALBQ) | Leader assures followers of competency – 3, Followers are provided opportunities to experience success – 3 |

|

| |

| Survey of Organizational Functioning (SOF) | Job satisfaction – 6 |

The STL included 84 items representing five core components that were further subdivided into 16 conceptual themes (see Figure 1 for proposed conceptual themes). The current assessment battery also included four scales from the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ 5X; Bass & Avolio, 1995) that corresponded with measures of transformational leadership. Reliability coefficients with this sample ranged from .92 to .88 and were consistent with Avolio, Bass, and Jung (1999). Two scales from the Attributes of Leader Behavior Questionnaire (ALBQ; Behling & McFillen, 1996) were also included. Reliability coefficients with this sample were .94 and .89, and were consistent with Behling and McFillen (1996).

Clinical staff completed the job satisfaction scale from the Survey of Organizational Functioning (SOF; Broome, Knight, Edwards, & Flynn, in press). Ratings for these six items (e.g., “you like the people you work with” and “you are satisfied with your present job”) were made using a 1 to 5 response scale; 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 indicated “strongly agree.” Scale scores were multiplied by 10, and ranged from 10 to 50. A dichotomous variable based on the median-split was developed for job satisfaction, in order to examine the mean difference of leadership ratings on high or low job satisfaction. The Cronbach alpha for this sample was .82.

Statistical Analysis

The STL was evaluated in two stages: first-order analysis on the STL core components and second-order analysis on transformational leadership, as a whole. The factor structure of each first-order and second-order factor was determined in two phases: (1) principal components analysis (PCA) to help establish the number of components extracted from the data and (2) maximum likelihood (ML) factor analysis procedures to provide a better estimate of the parameters. In the PCA, the most suitable solution for number of components extracted was based on (1) the Kaiser Criterion: requiring an eigenvalue greater than 1.00 and (2) interpretability with regard to transformational leadership theory. In the ML procedures, the resulting factor matrices were rotated, which helped make the factors as distinctive as possible. Because the chi-square test is sensitive to sample size (especially over 200; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1986; Marsh, Balla, & McDonald, 1988), the current study relied upon the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973) as the primary index of model fit. TLI values close to one support that the factor structure accounts for the sample variance and covariance. An item was retained in the factor when (1) the confidence interval for the item covered a region of values larger than the specified criterion value (i.e., .4; SAS Institute Inc. 2004) and (2) the item was consistent with the conceptual meaning of the high loading items on the specified factor.

The second-order factor loadings were estimated based on composite scores corresponding to each of the first-order factors. Following the factor analyses, tests of reliability (i.e., coefficient alpha), convergent validity (i.e., correlations with matching scales), and criterion-related validity (i.e., t-tests on relationship to job satisfaction) were examined for each of the measures developed.

First-Order Analysis of STL Core Components

Separate exploratory factor analyses were conducted within each of the five first-order conceptual core components. The decision to assess the 84 STL items by core component was based on the suggestion that for parameter estimation the sample be five times the number of items (Bryant & Yarnold, 1995).

In total, the five factor analyses resulted in nine first-order leadership factors: a single component for inspirational motivation and a two component structure for the other four components. Based on a confidence interval of .4 and item-factor meaningfulness, all items, except one from the intellectual stimulation core component, were retained in the development of the first-order factors. The factor loadings as determined by maximum likelihood factor analysis are presented in Table 3. The questionnaire items listed by core component and theme are shown in the Appendix.

Table 3.

Factor Loadings by Core Component

| Idealized Influence | Intellectual Stimulation | Inspirational Motivation | Individualized Consideration | Empowerment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Item # | IN | SR | Item # | EI | DI | Item # | IM | Item # | DO | SO | Item # | TD | EE |

| IN76 | .788 | .433 | EI2 | .879 | .457 | IM46 | .879 | DO61 | .778 | .373 | TD20 | .795 | .189 |

| IN69 | .783 | .339 | EI54 | .820 | .357 | IM41 | .866 | DO50 | .742 | .289 | TD40 | .789 | .293 |

| IN73 | .777 | .441 | EI59 | .762 | .247 | IM43 | .866 | DO85 | .720 | .509 | TD96 | .785 | .297 |

| IN53 | .751 | .425 | EI48 | .746 | .447 | IM75 | .854 | DO87 | .717 | .084 | TD25 | .745 | .226 |

| IN37 | .731 | .275 | EI70 | .731 | .421 | IM71 | .850 | DO67 | .569 | .484 | TD62 | .744 | .429 |

| IN64 | .718 | .380 | EI81 | .622 | .540 | IM52 | .838 | SO13 | .501 | .740 | TD51 | .739 | .337 |

| IN42 | .699 | .476 | EI77 | .615 | .577 | IM91 | .838 | SO4 | .443 | .689 | TD68 | .733 | .345 |

| IN47 | .697 | .421 | EI95 | .518 | .206 | IM49 | .826 | SO34 | .064 | .595 | TD56 | .717 | .317 |

| IN16 | .646 | .387 | DI84 | .306 | .772 | IM57 | .826 | TD5 | .671 | .285 | |||

| IN82 | .644 | .426 | DI86 | .387 | .682 | IM36 | .820 | TD45 | .670 | .351 | |||

| IN1 | .616 | .462 | DI79 | .342 | .585 | IM89 | .820 | TD30 | .638 | .284 | |||

| IN94 | .515 | .310 | DI28 | .345 | .581 | IM63 | .819 | TD93 | .636 | .533 | |||

| IN10 | .491 | −.097 | DI22 | .518 | .576 | IM12 | .790 | TD9 | .525 | .392 | |||

| SR17 | .309 | .797 | DI11 | .198 | .508 | IM29 | .787 | TD35 | .470 | .408 | |||

| SR21 | .125 | .789 | DI7 | .193 | .472 | IM23 | .780 | EE80 | .255 | .837 | |||

| SR27 | .348 | .762 | DI38 | .651 | .550 | IM83 | .769 | EE72 | .189 | .675 | |||

| SR31 | .237 | .653 | IM39 | .759 | EE78 | .383 | .672 | ||||||

| SR92 | .548 | .561 | IM15 | .755 | |||||||||

| SR88 | .514 | .530 | IM26 | .747 | |||||||||

| IM33 | .730 | ||||||||||||

| IM60 | .701 | ||||||||||||

| IM3 | .697 | ||||||||||||

| IM66 | .663 | ||||||||||||

| IM19 | .661 | ||||||||||||

Note: IN = Integrity, SR = Sensible Risk, EI = Encourages Innovation, DI = Demonstrates Innovation, IM = Inspirational Motivation, DO = Develops Others, SO = Supports Others, TD = Task Delegation, EE = Expects Excellence

Bold numbers represent highest loading within each core component.

Dimensionality

The overall pattern of results for each core component is illustrated in Figure 1 with a listing of observed empirical themes accounted for by proposed conceptual themes. The PCA identified two factors within idealized influence (eigenvalues = 8.95 and 1.16; TLI = .95): Integrity (13 items; 23% of the variance) and Sensible Risk (6 items; 15% of the variance); two factors within intellectual stimulation (eigenvalues = 11.01 and 1.58; TLI = .91): Encourages Innovation (8 items; 16% of the variance) and Demonstrates Innovation (7 items; 12% of variance); one factor within inspirational motivation (eigenvalue = 15.42; TLI = .89; 24 items, 45% of the variance); two factors within individualized consideration (eigenvalues = 4.82 and 1.06; TLI = 1.06): Develops Others (5 items; 10% of the variance) and Supports Others (3 items; 7% of the variance); and two factors within empowerment (eigenvalue = 9.75 and 1.31; TLI = .93): Task Delegation (14 items; 20% of the variance) and Expects Excellence (3 items; 10% of the variance). One item was removed from the intellectual stimulation core component due to similar item loadings on both factors. Additionally, one item within the empowerment component (i.e., “conveys confidence in staff members’ ability to accomplish tasks”) was initially conceptualized as part of Expects Excellence, however following factor analysis it was subsequently considered and accepted for inclusion in Task Delegation.

Scale Scoring and Validation

Table 4 displays the factor loadings, means, standard deviations, and reliability coefficients for the nine first-order leadership factors. The possible range of scores on the STL is 0 to 40. Expects Excellence represented the highest mean score of 33.22 (SD = 7.42) and Demonstrates Innovation had the lowest mean score of 26.11 (SD = 7.83).

Table 4.

Means, Standard Deviations, Factor Loadings, Intercorrelations, and Reliability Coefficients for First-Order Factors

| Theme | Factor Loading | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Integrity | .907 | 32.27 | 7.95 | .95 | ||||||||

| 2. Sensible Risk | .838 | 26.61 | 9.88 | .737 | .89 | |||||||

| 3. Encourages Innovation | .942 | 29.49 | 8.95 | .889 | .765 | .92 | ||||||

| 4. Demonstrates Innovation | .795 | 26.11 | 7.83 | .629 | .820 | .743 | .86 | |||||

| 5. Inspirational Motivation | .956 | 28.88 | 8.53 | .848 | .831 | .884 | .830 | .97 | ||||

| 6. Develops Others | .944 | 28.47 | 9.21 | .853 | .762 | .887 | .723 | .886 | . 89 | |||

| 7. Supports Others | .736 | 32.59 | 8.83 | .809 | .577 | .754 | .418 | .647 | .685 | .78 | ||

| 8. Task Delegation | .975 | 28.08 | 8.65 | .864 | .806 | .912 | .755 | .934 | .401 | .627 | .89 | |

| 9. Expects Excellence | .668 | 33.22 | 7.42 | .630 | .552 | .611 | .584 | .660 | .692 | .924 | .637 | .95 |

Note: Cronbach coefficient alphas along diagonal. All correlations significant at p < .001.

Internal consistency

Reliability for all first-order STL factors met or exceeded Nunally’s (1978) recommendation of .70 for newly developed scales. The alpha coefficient scores ranged from .78 (Supports Others) to .97 (Inspirational Motivation). The high coefficients support the conclusion that the STL reliably measures the first-order transformational leadership practices.

Convergent and criterion-related validity

Cronbach alphas for the validation factors ranged between .94 and .88. In order to examine convergent validity, the STL theme scores were compared to the MLQ or ALBQ component they were conceptually developed to represent. Table 5 contains the correlations between the STL and matching MLQ or ALBQ scales, along with descriptive statistics for the validation measures. In all cases the correlation between the STL theme and corresponding validation component was equal to or greater than .5.

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics for MLQ and ALBQ Scales and Correlations between STL Themes and Matching MLQ and ALBQ Scales

| MLQ Scales | ALBQ Scales | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Idealized Influence | Intellectual Stimulation | Inspirational Motivation | Individualized Consideration | Opportunities for Success | Assures Competency | |

|

| ||||||

| Cronbach α | .90 | .89 | .92 | .88 | .89 | .94 |

|

M (SD)

|

29.51 (8.37) | 27.26 (9.16) | 30.18 (9.23) | 27.69 (10.6) | 29.39 (9.78) | 28.7 (10.9) |

| STL Theme

|

||||||

| Integrity | .862 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Sensible Risk | .831 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Encourages Innovation | -- | .864 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Demonstrates Innovation | -- | .783 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Inspirational Motivation | -- | -- | .882 | -- | -- | -- |

| Develops Others | -- | -- | -- | .874 | -- | -- |

| Supports Others | -- | -- | -- | .741 | -- | -- |

| Task Delegation | -- | -- | -- | -- | .862 | -- |

| Expects Excellence | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .496 |

Note: All correlations significant at .001 level.

In order to evaluate criterion-related validity (whether the STL themes served as effective indicators of job satisfaction ratings), a dichotomous variable based on the median-split was developed for job satisfaction (M = 38.24, SD = 6.39). Table 6 presents the t-statistic values, along with descriptive statistics for job satisfaction. A series of t-tests revealed that the ratings of each STL theme significantly differed between low and high job satisfaction. Most notable was the association between Task Delegation and job satisfaction (low = 24.05, high = 31.28), with a difference of 7.23.

Table 6.

STL Themes Related to Low and High Job Satisfaction

| Theme | Low Job Satisfaction | High Job Satisfaction | t-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Integrity | 28.99 | 9.11 | 34.87 | 5.73 | −5.74 |

| Sensible Risk | 23.34 | 10.80 | 29.17 | 8.28 | −4.41 |

| Encourages Innovation | 26.06 | 10.12 | 32.2 | 6.81 | −5.26 |

| Demonstrates Innovation | 23.73 | 8.43 | 28.0 | 6.79 | −4.08 |

| Inspirational Motivation | 25.13 | 9.29 | 31.84 | 6.52 | −6.19 |

| Develops Others | 24.9 | 10.0 | 31.28 | 7.44 | −5.32 |

| Supports Others | 29.08 | 10.22 | 35.38 | 6.3 | −5.51 |

| Task Delegation | 24.05 | 9.26 | 31.28 | 6.59 | −6.63 |

| Expects Excellence | 31.18 | 8.81 | 34.84 | 5.61 | −3.66 |

All significant at p < .001.

Second-Order Analysis of Transformational Leadership

Composite scores for each of the nine first-order factors were used as the basis for component (eigenvalue = 7.00), termed Transformational Leadership. Maximum likelihood factor analysis was used to estimate the second-order factor loadings (Table 4). The total variance accounted for by the nine first-order factors was 57% (TLI = .87). The factor loadings suggested that the single component relates most strongly to the Task Delegation (.98) factor and least to the Expects Excellence factor (.67). Intercorrelations among the first-order factors were consistently high (Table 4), suggesting their commonalities and supporting the notion that the STL can be used as a global measure of transformational leadership. Scores on the single second-order factor had a possible range of 0 to 40 with an average score of 29.55 and a standard deviation of 7.54. The alpha coefficient for the single second-order factor was quite high at .96. The correlation between the STL second-order factor and the global measure of the MLQ was .95, showing good convergent validity between the two global measures of leadership. The STL second-order factor also demonstrates good criterion-related validity as evidenced by a statistically significant difference between low (M = 26.27) and high (M = 32.15) job satisfaction (t(211) = −6.12, p <.0001).

Discussion

Broome et al., (2009) report variability in leadership ratings within outpatient substance use treatment which suggests unevenness in the training and resources directors receive for their role as program leaders. “With greater attention to selecting, developing, and rewarding leadership, the substance abuse treatment field can take better advantage of a valuable human resource” (p. 169).

The aim of the current study was to develop a non-commercial instrument for assessing transformational leadership within substance use treatment organizations that is available free of charge, reliable, valid, and that can be used to inform organizational self-monitoring and training efforts. The Survey of Transformational Leadership (STL) utilizes a thorough and comprehensive approach, eliciting detailed information about specific leadership behaviors. Results suggest that within the five core components (i.e., idealized influence, intellectual stimulation, inspirational motivation, individualized consideration, and empowerment) nine distinct themes emerge, representing various facets of transformational-oriented practices (see Figure 1 for observed empirical themes). While the number of themes was fewer than expected, the STL allows for sufficient item-level detail to examine subtle distinctions between various themes within a core component. The one exception is inspirational motivation. Although it is possible that the perception of leadership behavior may be consistent across the inspirational motivation items, it is also likely that because most of the items contained a reference to “program goals,” participants failed to notice the conceptual distinction between the themes and subsequently maintained consistent ratings of their specified leader across the items.

Psychometric analysis revealed a moderately high average scale score for each of the nine first-order STL factors, suggesting that the leaders in these treatment programs were generally perceived as demonstrating each of the nine transformational leadership practices. However, some practices occurred more frequently than others. Staff observed more consistent integrity, support of others, encouragement of innovation, and expectations of excellence, while the other themes were less consistently observed. These lower ratings could reflect less emphasis on the part of leaders or perhaps fewer opportunities for observation by staff. For instance, sensible risk-taking may occur within more private contexts and outside of clinical supervisory interactions.

When comparing means of STL themes and parallel MLQ core components, the MLQ means generally fall between the two STL themes. For example, the MLQ Intellectual Stimulation mean is 27.3, mid-way between the corresponding STL themes of encourages innovation (29.5) and demonstrates innovation (26.1). The ability to distinguish between two different elements within a core component is helpful because it provides insight into which aspects are less often observed among clinical directors. Using these distinct measures may prove useful in identifying organization-specific patterns of leadership practices and in designing interventions for improving leadership within substance use treatment organizations.

The STL may also be used as a global measure of transformational leadership. The second-order factor analysis revealed a structure almost analogous to previous studies conducted using the MLQ (Barling, Loughlin, & Kelloway, 2002; Bono & Judge, 2003; Purvanova, Bono, & Dzieweczynski, 2006; Shin & Zhou, 2003). This suggests that the STL can be used to capture the essence or extent to which leaders are perceived as generally transformational in their approach. The lower loading for Expects Excellence could reflect subtle distinctions between the conceptual content of that theme and the other first-order factors. High performance expectations can increase role conflict, decrease staff satisfaction (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Bommer, 1996), and decrease trust in the leader (Podsakoff et al., 1990), especially when the leader does not express confidence in followers’ ability to complete tasks (House, 1977). In the current study, the item addressing whether the leader expresses confidence in completion of tasks loaded on Task Delegation instead of Expects Excellence. Without the confidence item, the Expects Excellence factor resembles more of a transactional leadership style, where a leader expects high performance of tasks in exchange for compensation, but does not necessarily communicate the anticipation that followers will meet the high expectations.

Some limitations of the present study should be noted. First, the study took place only in outpatient substance use treatment settings. Although findings may generalize within the treatment field where an overwhelming majority of substance use clients are treated in outpatient settings (Horgan, Reif, Ritter, & Lee, 2001), results may not generalize to other community behavioral healthcare settings or workers. However, considering that workplace practices and job attitudes are similar across service contexts, these findings may inform research in other service sectors (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006). Additionally, while the current study demonstrated staff-leader relations specifically within substance use treatment settings, previous findings have shown the effects of transformational leadership in a variety of settings (Bass, 1997). Second, leadership practices in relation to outcome measures (e.g., followers extra effort, job performance, attitudes toward organization change) were not assessed which precludes an estimate of predictive validity. Future studies in other samples will allow for further validation of the STL.

The STL has practical implications for substance use treatment settings. External pressures from funding sources as well as internal budget and staffing constraints are affecting service providers and forcing directors to promote a work environment that is creative and responsive to innovation. Previous studies have shown that transformational leadership practices are related to favorable organizational climates (e.g., less stress and burnout among staff; Selzer et al., 1989). Counselors within the treatment field that report positive work climates also show more positive attitudes toward change (Joe, Broome, Simpson, & Rowan-Szal, 2007; Simpson, Joe, & Rowan-Szal, 2007). Subsequently, further research is needed to determine the utility of the leadership themes, as measured by the STL, in promoting and sustaining organizational change, improving attitudes toward evidence-based practices (EBPs), as well as predicting outcomes, particularly with regard to improving staff satisfaction and retention.

Because staff perceptions of leadership impact job attitudes and could ultimately affect clients, directors tasked with promoting change and innovation would benefit from attending to each of the themes included in the STL. The global measure of transformational leadership can be used as an overall guide for identifying administrators that would gain the most from training, while an examination of scores on distinct themes can be used to target specific areas of leader development needing attention (Den Hartog, Van Muijen, & Koopman, 1997). Conger and colleagues (Conger & Benjamin, 1999; Conger & Kanungo, 1988) specified a number of “competencies” for leader training that are consistent with themes addressed in the STL. For instance, directors can learn to empower others by assigning meaningful tasks and being supportive of task completion through removing constraints and providing resources, which could lead to better client outcomes through intensified service provision or better client engagement.

Currently there is a need for transformational practices within substance use treatment organizations. The STL (available for free download from http://www.ibr.tcu.edu/pubs/datacoll/commtrt.html) represents a non-commercial and comprehensive approach for assessing transformational leadership and shows promise for informing administration practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Gulf Coast, Great Lakes, Northwest Frontier, and South Coast Addiction Technology Training Centers (ATTCs) in the U.S. for their assistance with recruitment and training. We would also like to thank the individual programs (administrators and staff) that participated in the assessments and training in the TCOM project.

This work was funded by the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant R01 DA014468).

Glossary

- Transformational leadership

a leadership style similar to charismatic or visionary leadership that promotes intellectual stimulation among followers, inspires motivation, and considers each staff member’s needs

Appendix. Survey of Transformational Leadership Questionnaire Items

| Integrity | |

| IN1. | shows determination on the job. |

| IN10. | does not display honesty. (R) |

| IN16. | is approachable. |

| IN37. | considers the ethical implications of actions. |

| IN42. | expresses values shared by program staff members. |

| IN47. | encourages staff behaviors consistent with the values shared by all members. |

| IN53. | acts consistently with values shared by program staff members. |

| IN64. | keeps commitments. |

| IN69. | is trustworthy. |

| IN73. | behaves in ways that strengthens respect from staff members. |

| IN76. | is someone that staff members are proud to be associated with. |

| IN82. | models behaviors other staff are asked to perform. |

| IN94. | shows self-confidence. |

| Sensible Risk | |

| SR17. | takes appropriate personal risks in order to improve the program. |

| SR21. | takes personal chances in pursuing program goals. |

| SR27. | is willing to personally sacrifice for the sake of the program. |

| SR31. | makes bold personal decisions, if necessary, to improve the program. |

| SR88. | performs tasks other than own, when necessary, to fulfill program objectives. |

| SR92. | seeks program interests over personal interests. |

| Encourages Innovation | |

| EI2. | attempts to improve the program by taking a new approach to business as usual. |

| EI48. | positively acknowledges creative solutions to problems. |

| EI54. | encourages ideas other than own. |

| EI59. | is respectful in handling staff member mistakes. |

| EI70. | encourages staff to try new ways to accomplish their work. |

| EI77. | suggests new ways of getting tasks completed. |

| EI81. | asks questions that stimulate staff members to consider ways to improve their work performance. |

| EI95. | does not criticize program members’ ideas even when different from own. |

| Demonstrates Innovation | |

| DI7. | accomplishes tasks in a different manner from most other people. |

| DI11. | tries ways of doing things that are different from the norm. |

| DI22. | seeks new opportunities within the program for achieving organizational objectives. |

| DI28. | identifies limitations that may hinder organizational improvement. |

| DI79. | challenges staff members to reconsider how they do things. |

| DI84. | takes bold actions in order to achieve program objectives. |

| DI86. | searches outside the program for ways to facilitate organizational improvement. |

| Inspirational Motivation | |

| IM3. | makes staff aware of the need for change in the program. |

| IM12. | conveys hope about the future of the program. |

| IM15. | communicates program needs. |

| IM19. | identifies program weaknesses. |

| IM23. | considers staff needs when setting new program goals. |

| IM26. | encourages staff feedback in choosing new program goals. |

| IM29. | develops new program goals. |

| IM33. | talks about goals for the future of the program. |

| IM36. | displays enthusiasm about pursuing program goals. |

| IM39. | uses metaphors and/or visual tools to convey program goals. |

| IM41. | displays confidence that program goals will be achieved. |

| IM43. | expresses a clear vision for the future of the program. |

| IM46. | clearly defines the steps needed to reach program goals. |

| IM49. | sets attainable objectives for reaching program goals. |

| IM52. | helps staff members see how their own goals can be reached by pursuing program goals. |

| IM57. | demonstrates tasks aimed at fulfilling program goals. |

| IM60. | allocates resources toward program goals. |

| IM63. | obtains staff assistance in reaching program goals. |

| IM66. | secures support from outside the program when needed to reach program goals. |

| IM71. | promotes teamwork in reaching program goals. |

| IM75. | expresses confidence in staff members’ collective ability to reach program goals. |

| IM83. | prepares for challenges that may result from changes in the program. |

| IM89. | encourages staff to share suggestions in how new program goals will be implemented. |

| IM91. | behaves consistently with program goals. |

| Develops Others | |

| DO50. | offers individual learning opportunities to staff members for professional growth. |

| DO61. | takes into account individual abilities when teaching staff members. |

| DO67. | coaches staff members on an individual basis. |

| DO85. | recognizes individual staff members’ needs and desires. |

| DO87. | assists individual staff members in developing their strengths. |

| Supports Others | |

| SO4. | treats staff members as individuals, rather than as a collective group. |

| SO13. | treats individual staff members with dignity and respect. |

| SO34. | does not respect individual staff members’ personal feelings. (R) |

| Task Delegation | |

| TD5. | provides opportunities for staff to participate in making decisions that affect the program. |

| TD9. | provides opportunities for staff members to take primary responsibility over tasks. |

| TD20. | delegates tasks that provide encouragement to staff members. |

| TD25. | delegates tasks that build up the organization. |

| TD30. | assigns tasks based on staff members’ interests. |

| TD35. | enables staff to make decisions, within contractual guidelines, on how they get their work done. |

| TD40. | follows delegation of a task with support and encouragement. |

| TD45. | sees that authority is granted to staff in order to get tasks completed. |

| TD51. | provides requested support for task completion. |

| TD56. | allocates adequate resources to see tasks are completed. |

| TD62. | provides information necessary for task completion. |

| TD68. | provides feedback on progress toward completing a task. |

| TD93. | conveys confidence in staff members’ ability to accomplish tasks. |

| TD96. | helps staff members set attainable goals to accomplish work tasks. |

| Expects Excellence | |

| EE72. | expects excellence from staff. |

| EE78. | expects that members of the staff will take the initiative on completing tasks. |

| EE80. | expects that staff members will give tasks their best effort. |

Note: (R) designates items that have been reverse coded.

Footnotes

The interpretations and conclusions, however, do not necessarily represent the position of the NIDA, NIH, or Department of Health and Human Services. More information (including intervention manuals and data collection instruments that can be downloaded without charge) is available on the Internet at www.ibr.tcu.edu, and electronic mail can be sent to ibr@tcu.edu.

References

- Aarons GA. Transformational and transactional leadership: Association with attitudes toward evidence based practice. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:1162–1169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.8.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Sawitzky A. Organizational climate partially mediates the effect of culture on work attitudes and staff turnover in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33:289–301. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0039-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alimo-Metcalfe B, Alban-Metcalfe J. The crucial role of leadership in meeting the challenges of change. Vision. 2005;9:27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio BJ, Bass BM. Manual for the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (Form 5X) Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio BJ, Bass BM, Jung DI. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 1999;72:441–462. [Google Scholar]

- Barling J, Loughlin C, Kelloway E. Development and test a model linking safety-specific transformational leadership and occupational safety. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87(3):488–496. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass BM. Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bass BM. A new paradigm of leadership: An inquiry into transformational leadership. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bass BM. Does the transactional-transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? American Psychologist. 1997;52:130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bass BM. Transformational leadership: Industrial, military, and educational impact. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bass BM. Two Decades of Research and Development in Transformational Leadership. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology. 1999;8:9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bass BM, Avolio BJ. The implications of transactional and transformational leadership for individual, team, and organizational development. In: Woodman RW, Passmore WA, editors. Research in organizational change and development. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1990. pp. 231–272. [Google Scholar]

- Bass BM, Avolio BJ. The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (form R, revised) Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bass BM, Riggio RE. Transformational leadership. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beer M. Organizational change and development. Santa Monica, CA: Goodyear; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis WG, Nanus B. Leaders: The strategies for taking charge. New York: Harper & Row; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Behling O, McFillen JM. A syncretical model of charismatic/transformational leadership. Group & Organization Management. 1996;21(2):163–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bono J, Judge T. Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Academy of Management Journal. 2003;46(5):554–571. [Google Scholar]

- Broome KM, Flynn PM, Knight DK, Simpson DD. Program structure, staff perceptions, and client engagement in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome KM, Knight DK, Edwards JR, Flynn PM. Leadership, burnout, and job satisfaction in outpatient drug-free treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, Yarnold PR. Principal components analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In: Grimm LG, Yarnold PR, editors. Reading and understanding multivariate analysis. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Burns JM. Leadership. New York: Harper & Row; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bycio P, Hackett R, Allen J. Further assessments of Bass’s (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1995;80(4):468–478. [Google Scholar]

- Conger JA, Benjamin B. Building leaders: How successful companies develop the next generation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Conger JA, Kanungo RN. Toward a behavioral theory of charismatic leadership in organizational settings. Academy of Management Review. 1987;12:637–647. [Google Scholar]

- Conger JA, Kanungo RN. Charismatic leadership: The elusive factor in organization effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Conger JA, Kanungo RN. Charismatic leadership in organizations: Perceived behavioral attitudes and their measurement. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1994;15:439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Conger JA, Kanungo RN. Charismatic leadership in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aunno T. The role of organization and management in substance abuse treatment: Review and roadmap. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Hartog DN, Van Muijen JJ, Koopman PL. Transactional versus transformational leadership: An analysis of the MLQ. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 1997;70:19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, Simpson DD. Adoption and implementation of evidence-based treatment. In: Miller PM, editor. Evidence-based addiction treatment. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Garner BR, Knight K. Counselor burnout and the therapeutic relationship. In: Knight K, Farabee D, editors. Treating addicted offenders: A continuum of effective practices. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 2007. pp. 35-1–35-13. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman JR. The psychology of self-management in organizations. In: Pollack MS, Perloff RO, editors. Psychology and work: Productivity, change, and employment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1986. pp. 89–136. [Google Scholar]

- Herold D, Fedor D, Caldwell S, Liu Y. The effects of transformational and change leadership on employees’ commitment to a change: A multilevel study. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008 Mar;93:346–357. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan CM, Reif S, Ritter GA, Lee MT. Organizational and financial issues in the delivery of substance abuse treatment services. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism, Volume 15: Services research in the era of managed care. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House RJ. A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In: Hunt JG, Larson LL, editors. Leadership: The cutting edge. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press; 1977. pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Howard A. Identifying, assessing, and selecting senior leaders. In: Zaccaro SJ, Klimoski RJ, editors. The nature of leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 305–346. [Google Scholar]

- Howell JM. Organizational contexts, charismatic and exchange leadership. In: Tosi HL, editor. The environment/organization/person contingency model: A meso approach to the study of organizations. Greenwich, CT: JAI; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Broome KM, Simpson DD, Rowan-Szal GA. Counselor perceptions of organizational factors and innovations training experiences. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(2):171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL IV: Analysis of linear structural relationships by maximum likelihood, instrumental variables and least squares methods. 4. Mooresville, IN: Scientific Software; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Judge TA, Piccolo RF. Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2004;89:755–768. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly JR, McLellan AT. The business of addiction treatment: A research agenda. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N, Anderson N. Innovation in working groups. In: West MA, Farr JL, editors. Innovation and creativity at work. New York: Wiley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter JP, Heskett JL. Corporate culture and performance. New York: Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnert KW, Lewis PL. Transactional and transformational leadership: A constructive/developmental analysis. Academy of Management Review. 1987;12:648–657. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H, Balla J, McDonald R. Goodness-of-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:391–410. [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Epitropaki O. Role of organizational identification on implicit leadership theories (ILTs), transformational leadership and work attitudes. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2001;4:247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. New York: Harper; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland DC. Power: The inner experience. New York: Irvington Publishers; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Nunally J. Psychometric theory. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Peters T, Waterman R., Jr How the best-run companies turn so-so performers into big winners. Management Review. 1982;71:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Bommer WH. Transformational leader behaviors and substitutes for leadership as determinates of employee satisfaction, commitment, trust, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Management. 1996;2:259–298. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Moorman RH, Fetter R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, an organization citizenship behaviors. Leadership Quarterly. 1990;1:107–142. [Google Scholar]

- Purvanova R, Bono J, Dzieweczynski J. Transformational leadership, job characteristics, and organizational citizenship performance. Human Performance. 2006;19:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Raelin JA. An anatomy of autonomy: Managing professionals. Academy of Management Executive. 1989;3:216–228. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty AE, Griffin MA. Perceptions of organizational change: A stress and coping perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:1154–1162. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman PM, Ducharme LJ, Knudsen HK. Patterns of organization and management in private and public substance abuse treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:255–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, Inc. SAS OnlineDoc® 9.1.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sashkin M, Sashkin MG. Leadership that matters. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer J, Numerof RE, Bass BM. Transformational leadership: Is it a source of more or less burnout and stress? Journal of Health and Human Resources Administration. 1989;12:174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Zhou J. Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Academy of Management Journal. 2003;46(6):703–714. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal GA. Linking the elements of change: Program and client responses to innovation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(2):201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreizer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Review. 1995;38:1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Tichy NM, Devanna M. The transformational leader. New York: Wiley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. The reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Vancouver J, Schmitt N. An exploratory examination of person-organization fit: Organizational goal congruence. Personnel Psychology. 1991;44(2):333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman D, Javidan M, Varella P. Charismatic leadership at the strategic level: A new application of upper echelons theory. Leadership Quarterly. 2004;15(3):355–380. [Google Scholar]

- Wells R, Lemak CH, D’Aunno TA. Organizational survival in the outpatient treatment sector 1988–2000. Medical Care Research and Review. 2005;62:697–719. doi: 10.1177/1077558705281062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukl G. An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. Leadership Quarterly. 1999;10:285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl G. Leadership in organizations. 5. Upper Saddlewood, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2002. [Google Scholar]