The authors present a novel protocol for deriving myogenic progenitors from human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells using free-floating spherical culture. Results show that sphere-based cultures of human pluripotent stem cells, expanded in medium containing high concentrations of fibroblast growth factor and epidermal growth factor, can propagate myogenic progenitors from human embryonic stem cells and healthy and disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells.

Keywords: Skeletal muscle, Induced pluripotent stem cells, Embryonic stem cells, Muscular dystrophy, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Spinal muscular atrophy

Abstract

Using stem cells to replace degenerating muscle cells and restore lost skeletal muscle function is an attractive therapeutic strategy for treating neuromuscular diseases. Myogenic progenitors are a valuable cell type for cell-based therapy and also provide a platform for studying normal muscle development and disease mechanisms in vitro. Human pluripotent stem cells represent a valuable source of tissue for generating myogenic progenitors. Here, we present a novel protocol for deriving myogenic progenitors from human embryonic stem (hES) and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells using free-floating spherical culture (EZ spheres) in a defined culture medium. hES cell colonies and human iPS cell colonies were expanded in medium supplemented with high concentrations (100 ng/ml) of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and epidermal growth factor in which they formed EZ spheres and were passaged using a mechanical chopping method. We found myogenic progenitors in the spheres after 6 weeks of culture and multinucleated myotubes following sphere dissociation and 2 weeks of terminal differentiation. A high concentration of FGF-2 plays a critical role for myogenic differentiation and is necessary for generating myogenic progenitors from pluripotent cells cultured as EZ spheres. Importantly, EZ sphere culture produced myogenic progenitors from human iPS cells generated from both healthy donors and patients with neuromuscular disorders (including Becker’s muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Taken together, this study demonstrates a simple method for generating myogenic cells from pluripotent sources under defined conditions for potential use in disease modeling or cell-based therapies targeting skeletal muscle.

Introduction

In recent years, stem cells have received much focus because of their potential use for developing cell-based therapies and in vitro modeling. An attractive therapeutic strategy for neuromuscular diseases, such as muscular dystrophy, is to use stem cells to replace degenerating muscle cells and restore lost skeletal muscle function [1, 2]. Myogenic progenitors, also called skeletal muscle stem/progenitor cells, are a valuable cell type for cell-based therapy and have provided a platform for studying normal muscle development and disease mechanisms in vitro. To date, various myogenic progenitors have been isolated from pre- or postnatal muscles as well as nonmuscle somatic tissues [1].

Human pluripotent stem cells, such as human embryonic stem (hES) cells and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, have been recognized as a valuable source from which to propagate human myogenic progenitors using distinct protocols for muscle differentiation [3–7]. Some of these traditional protocols use embryoid body (EB) formation or the derivation of multipotent mesodermal precursors. Although these protocols mimic early human embryogenesis, additional procedures are often necessary to obtain a sufficient quantity of progenitors. Selective induction of myogenic genes PAX3 and PAX7 has been used following EB formation to improve the efficiency of myogenic differentiation [8]. Other protocols use fluorescence-activated cell sorting to obtain a sufficient purity and quantity of myogenic progenitors [7, 9]. Although these methods are effective, such manipulations may limit clinical application and large-scale manufacturing [3]. An alternative protocol for preparing myogenic progenitors from pluripotent stem cells in sufficient quality and quantity for clinical testing would therefore be useful for advancing the therapeutic use of myogenic progenitors in patients.

In this study, we demonstrate a new protocol for the derivation of myogenic progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells using a free-floating spherical culture (EZ spheres). The EZ sphere culture method was originally established to expand neural progenitor cells from human pluripotent stem cells [10–13]. This culture method uses medium that contains fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and epidermal growth factor (EGF). Both FGF-2 and EGF have been used for expansion of side population cells from mouse muscle fibers shown to maintain myogenic potential [14, 15]. Here, we identify myogenic markers in EZ spheres, suggesting that this culture method is capable of producing human myogenic progenitors similar to myospheres previously described for maintaining myogenic progenitors isolated from fetal and adult skeletal muscles [16–19]. We also establish that a high concentration of FGF-2 plays a critical role in generating myogenic progenitors from hES and iPS cells using EZ spheres. Finally, we tested the ability of EZ spheres to generate myogenic progenitors using various lines of human iPS cells, including iPS cells from healthy donors and from patients with neuromuscular disorders including Becker’s muscular dystrophy (BMD), spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Materials and Methods

Human Pluripotent Stem Cells

hES (WA09 and WA01) and wild-type iPS (IMR90) cell lines were obtained from WiCell Research Institute (Madison, WI, http://www.wicell.org). Patient-specific iPS cells were generated from healthy individuals (lines 21.8 and 4.2) and patients with spinal muscular atrophy (iPS-SMA 3.6, 7.12) [11, 13], Becker’s muscular dystrophy (iPS-BMD) [20], and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis due to mutation of superoxide dismutase 1 (iPS-ALS SOD1) or vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B/C (iPS-ALS VAPB) [21]. The wild-type IMR90 iPS cell line, the control 4.2 iPS cell line, and the iPS-SMA 3.6 line were generated from human skin fibroblasts with lentivirus infection of Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, and Lin28 [11, 22]. The iPS-SMA 7.12 line was generated from human skin fibroblasts using episomal vectors expressing Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, Lin28, KLF4, and c-MYC as described previously [13]. The wild-type 21.8 line was generated from human skin fibroblasts using lentiviral expression of Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, Lin28, KLF4, and c-MYC as described previously [10]. iPS-BMD and iPS-ALS SOD1 lines were obtained from the Coriell Institutes (Camden, NJ, http://www.coriell.org), and the iPS ALS VAPB line was graciously provided by Dr. Alysson Muotri (University of California, San Diego). All hES and iPS cell colonies were maintained as described previously by using either feeder-dependent [23] or -independent protocols [24, 25]. Unless otherwise specified, feeder-dependent hES (WA09) and feeder-independent wild-type iPS (IMR90) cell lines were used in this study.

EZ Sphere Preparation Using hES and iPS Cells

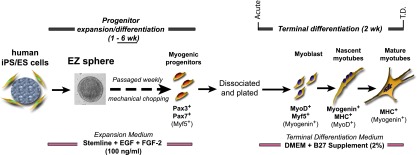

The schematic illustration of the culture schedule and treatments is summarized in Figure 1. hES and iPS cell colonies were lifted by collagenase (0.1%; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, http://www.lifetechnologies.com) and placed in an expansion medium (Stemline medium, S-3194; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B (PSA) (1% vol/vol), 100 ng/ml human basic FGF-2 (WiCell), 100 ng/ml human EGF (Millipore, Billerica, CA, http://www.millipore.com), and 5 ng/ml heparin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) [12, 16]. The culture flask was precoated with poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (poly-HEMA) Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent attachment of the cells to the surface. After 1 week, the colonies formed spherical aggregates called EZ spheres. For EB formation, hES cell colonies were placed in a poly-HEMA flask with an EB formation medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12; Life Technologies) containing 15% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, http://www.thermoscientific.com), 20% knockout serum replacement (Life Technologies), 1% nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies), 1 mM glutamate (Sigma-Aldrich) with 0.01% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% PSA (Life Technologies) [23]. All cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator (37°C) with half of the medium replaced with fresh every 2–3 days. When the EZ spheres and EBs reached approximately 500 µm in diameter, they were passaged by mechanically chopping into 200-µm cubes using a McIlwain tissue chopper (Mickle Laboratory Engineering, Surrey, U.K., http://www.micklelab.co.uk) [26]. The EZ spheres were passaged approximately every 7 days. In this study, data are presented as the absolute time in weeks the cells were cultured as spheres rather than passage number.

Figure 1.

Myogenic differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells using sphere-based culture (EZ sphere). EZ spheres were cultured from feeder-dependent hES and feeder-independent iPS cell colonies in expansion/differentiation medium containing high concentrations (100 ng/ml) of FGF-2 and EGF. EZ spheres were passaged weekly by mechanical chopping. Depending on the experiment, the spheres were incubated and passaged in expansion/differentiation medium for 1–6 weeks, with 6 weeks determined to be optimal for generating myogenic progenitors. As an indirect report of myogenic progenitor population within the spheres, the spheres were then dissociated and plated on coverslips and terminally differentiated for 2 weeks. Abbreviations: DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; EGF, epidermal growth factor; ES, embryonic stem; FGF-2, fibroblast growth factor-2; hES, human embryonic stem cells; iPS, induced pluripotent stem; MHC, myosin heavy chain; Myf5, myogenic factor 5; MyoD, myogenic differentiation 1; T.D., terminally differentiated.

Muscle Differentiation of EZ Sphere-Derived Cells

To determine the phenotypes of cells within EZ spheres and EBs as well as measure their innate ability to differentiate into skeletal muscle, we dissociated EZ spheres and EBs using trypsin (TrypLE; Life Technologies), which were plated onto coverslips precoated with polyornithine and laminin (both Sigma-Aldrich) and cultured in a skeletal muscle differentiation medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 2% B27 (Life Technologies) [5]. The plated cells were allowed to incubate 4–10 hours (acute) or 2 weeks (terminal differentiation; Fig. 1).

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were processed for immunocytochemistry by fixing in either ice-cold methanol (for myosin heavy chain [MHC]) or 4% paraformaldehyde and stained as described previously [16]. Briefly, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X100, 5% normal donkey serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After rinsing with PBS, the cells were incubated with primary antibodies against Pax7 (1:40, mouse monoclonal; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB], Iowa City, IA, http://dshb.biology.uiowa.edu), myogenic differentiation 1 (MyoD; 5.8A, 1:50, mouse monoclonal; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, http://www.vectorlabs.com), myogenin (F5D, 1:50, mouse monoclonal; DSHB), or MHC (MF20, 1:20, mouse monoclonal; DSHB). To check postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors, we incubated the fixed cells with α-Bungarotoxin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (1:1,000; Life Technologies). After incubation with the primary antibodies, the cultures were rinsed with PBS, and incubated with secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or Cy3 (anti-IgG, 1:1,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, http://www.jacksonimmuno.com). Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (0.5 µg/ml in PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) after completion of the secondary antibody incubation. Immunocytochemical images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse 80i fluorescence microscope and a DS-QiIMC charge-coupled device camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan, http://www.nikon.com). Cell counts were performed with NIS-Elements imaging software (Nikon). In a given field, the Hoechst stain was used to assess the total number of cells. Next, the total number of cells staining positive for each marker was then counted in the same field. A ratio of marker positive cells to total cells was then created and expressed as the percentage of positive cells for that field. The percentage of positive cells for each antibody was determined by averaging counts from at least six different, randomly selected microscopic fields. Cell count data are reported as mean ± SEM. In the case of nuclear staining markers (e.g., Pax7, MyoD, and myogenin), nuclei double-stained for DNA (Hoechst) and marker were counted as positive. The percentage of positive MHC myotubes was calculated as a percentage of the total nuclei surrounded by MHC staining (appearing singly or multinucleated) in five randomly chosen microscopic fields using a ×20 objective.

Immunohistochemistry Using Sphere Sections

EZ spheres and EBs were allowed to settle in 15-ml Falcon tubes before the culture medium was removed and replaced with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature. The fixed spheres were cryoprotected with 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C. The spheres were then embedded in HistoPrep Frozen Tissue Embedding Media compound (Thermo Fisher Scientific), sectioned at 10 μm on a cryomicrotome, and processed for immunohistological detection using antibodies directed against Pax7 and Ki67, a marker for proliferation (1:200, mouse monoclonal; Millipore) as described above.

Karyotyping

EZ spheres were dissociated using TrypLE (Life Technologies) as described above, and 80,000 cells were plated into a Matrigel-coated (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, http://www.bdbiosciences.com) T25 flask and shipped to Cell Line Genetics Inc. (Madison, WI, http://www.clgenetics.com) for G-band karyotype analysis.

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA isolation and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) were performed as previously described [16]. Total RNA was extracted from EZ spheres or differentiated cells using RNeasy purification systems (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, http://www.qiagen.com). RT-PCR was run using RT reaction mix and PCR Master Mix (both Promega Corp., Madison, WI, http://www.promega.com) in a thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, http://www.eppendorf.com). The same primers for myogenic marker genes (PAX3, PAX7, MYF5, MYOD, MYOGENIN, and β-ACTIN) were used as described in our recent study [16]. The total RNA isolated from human fetal skeletal muscle was used as a positive control for RT-PCR [16].

Skeletal Muscle Video Capture

EZ spheres from ALS-iPS SOD1 were dissociated and plated as previously described. After 25 days in skeletal muscle differentiation medium, video was captured on a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope with a Qimage camera and processed with Q Capture Pro software. Thirty static frames were captured at a 25-millisecond capture rate (set at minimum possible interval), with an exposure of 100 milliseconds. Sequence files were converted to avi files using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze differences in percentage of total cells staining positive for myogenic markers at multiple time points and under multiple media conditions containing different combinations of growth factors. A Bonferroni multiple comparison post hoc test for significance was used following ANOVA. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare percentage of total cells staining positive for myogenic markers after being incubated under media conditions containing two different concentrations of growth factor. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 5.01 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, http://www.graphpad.com). Averages are mean ± SEM.

Results

Sphere-Based Cultures Can Enhance Myogenic Differentiation From hES Cells

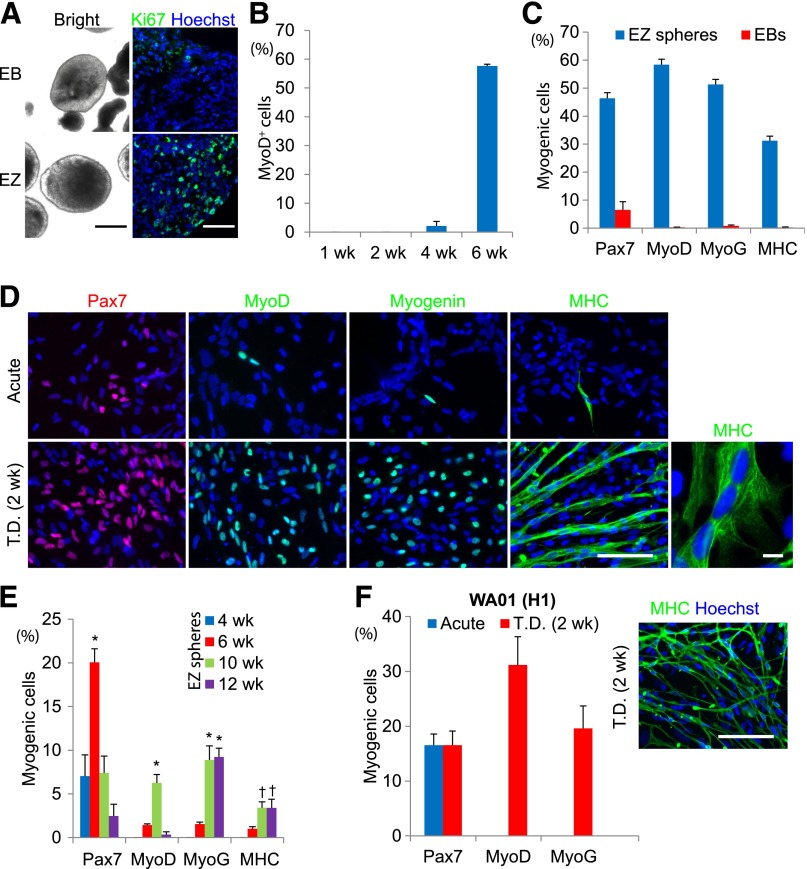

We first asked whether hES cells can differentiate into myogenic progenitors using free-floating sphere-based culture (Fig. 1). hES cell colonies (line WA09) were lifted from mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder layers and cultured in expansion medium containing high concentrations of FGF-2 and EGF (100 ng/ml each). Within 1 week, the cells formed spherical aggregates called EZ spheres. As a parallel experiment, EBs were prepared using a traditional protocol for EB formation [23]. Immunocytochemistry using anti-Ki67 antibodies revealed that cells within the EZ spheres continued cell division, whereas EBs prepared in a medium without growth factors contained few Ki67-positive proliferating cells (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that EZ spheres contain more cells that retain their proliferative capacity than EBs under standard conditions.

Figure 2.

Feeder-dependent hES cell-derived EZ spheres can efficiently differentiate into skeletal muscle cells. (A): Immunostaining for a proliferation marker Ki67 indicates that the cells in EZ spheres actively proliferate and embryoid bodies have few proliferating cells. Brightfield scale bar = 250 μm. Immunofluorescence scale bar = 100 µm. (B): MyoD+ cell count data of WA09 hES cells cultured as EZ spheres for 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks, and then terminally differentiated. (C): Following 6 weeks of EZ sphere culture, dissociation, plating, and terminal differentiation, approximately 40%–60% of cells expressed markers for early progenitor (Pax7+) cells differentiated toward muscle cells (MyoD+ and MyoG+). Analysis of MHC+ cells revealed that 30% of cells formed expressed high levels of MHC, many of which incorporated into multinucleated myotubes. The percentage of cells labeled for muscle cell markers is significantly higher when the cells are expanded using the EZ sphere culture method (EZ) when compared with a more traditional embryoid body-based protocol (EB). (D): Representative images of immunocytochemistry labeling for skeletal muscle cell markers in WA09 cells cultured using the EZ sphere protocol for 6 weeks, then either acutely plated (no terminal differentiation step) or terminally differentiated for 2 weeks into myoblasts/myotubes (T.D. 2 weeks). ×20 scale bar = 100 µm. ×100 image (right box) of MHC labeling showing representative multinucleated myotubes. Scale bar = 10 µm. (E): EZ spheres cultured for 4, 6, 10, and 12 weeks were dissociated and the cells were acutely plated on coverslips (i.e., before terminal differentiation step). Pax7 expression was highest at 6 weeks but reduced by 10 weeks. MyoD, MyoG, and MHC were seen primarily after 10 weeks (∗, p < .001, †, p < .01). (F): To confirm the ability to use EZ sphere culture to generate myogenic progenitors, we expanded/differentiated cells from another feeder-dependent hES line (WA01) as EZ spheres for 6 weeks, then terminally differentiated and stained for myogenic markers and counted. Scale bar = 100 µm. Error bars = SEM. Abbreviations: EB, embryoid body; hES, human embryonic stem cells; iPS, induced pluripotent stem cells; MHC, myosin heavy chain; MyoD, myogenic differentiation 1; MyoG, myogenin; T.D., terminally differentiated.

The EZ spheres were passaged using a nonenzymatic, mechanical chopping [12, 26]. After 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks of culture, EZ spheres were dissociated by trypsin and plated on laminin-coated coverslips. Similarly, after 4 and 6 weeks culture, EBs were dissociated and plated on coverslips. In order to determine myogenic differentiation, we maintained the plated cells in terminal differentiation medium for 2 weeks. The cells were then fixed and labeled for markers of early muscle progenitors (Pax7), differentiated skeletal myoblasts (MyoD and myogenin [MyoG]), and mature skeletal myocytes (MHC; Fig. 2B–2D). MyoD+ cells were virtually undetectable in the plated cells differentiated from 1-, 2-, and 4-week EZ spheres following the terminal differentiation step (Fig. 2B). However, the number of MyoD+ cells was observed to be greatly increased in cells terminally differentiated from EZ spheres expanded/differentiated for 6 weeks. In acutely plated cells (day 0), few were found to express MyoD, MyoG, or MHC, although Pax7 expression was high (data not shown; Fig. 2D). After 2 weeks of differentiation, the prevalence of Pax7+, MyoD+, and myogenin+ cells increased dramatically to 40%–50% of total cells (Fig. 2C, 2D). Furthermore, analysis of cells staining positive for MHC revealed that 35% of cells were either expressing high levels of MHC or forming multinucleated myotubes (Fig. 2D, MHC 100×). In contrast, the cells derived from all stages of EBs did not show robust myogenic differentiation (Fig. 2C).

We next asked whether the myogenic progenitor state can be maintained in EZ spheres for an extended period of time or whether there is a specific window for efficient progenitor propagation. EZ spheres were collected after 4, 6, 10, and 12 weeks of culture, dissociated, and acutely plated on coverslips without being allowed to differentiate. Pax7+ cells were identified by 4 weeks (7.0% ± 2.4% of total cells), increased significantly and peaked by 6 weeks (20.1% ± 1.6%, p < .001), but gradually decreased to 7.4% ± 1.9% and 2.5% ± 1.4% by 10 weeks and 12 weeks, respectively (Fig. 2E). The percentages of MyoD+ and MyoG+ cells were found to be significantly increased by 10 weeks (6.3% ± 1.0% and 8.9% ± 1.6%, respectively, p < .001). MHC+ multinucleated myotubes were also observable by 10 weeks of expansion (3.4% ± 0.7%, p < .01). These results indicate that the highest number of Pax7+ cells was observed after 6 weeks of culture, but then the cells gradually differentiated into late-stage muscle cells with continued EZ sphere culture over the next 6 weeks. In addition, we prepared EZ spheres from a second feeder-dependent hES cell line (WA01) (Fig. 2F) and feeder-independent WA09 hES cells (data not shown). Both lines were determined to be suitable for myogenic differentiation using the EZ sphere culture method.

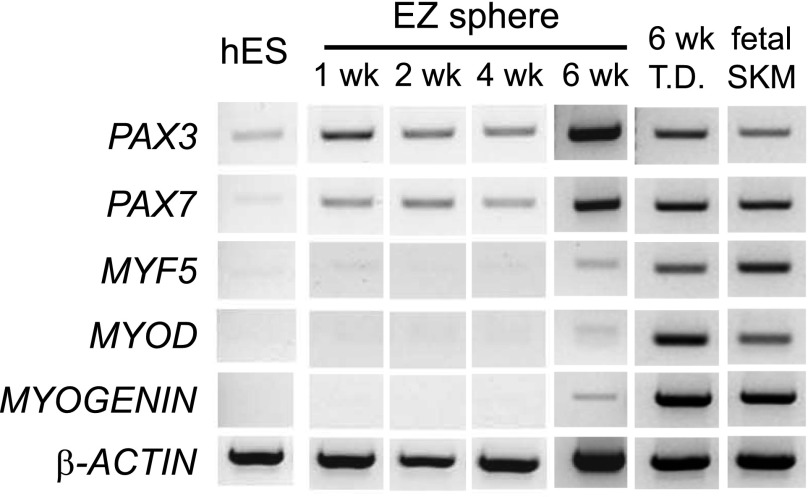

We next performed RT-PCR to determine relative mRNA levels of pluripotent and myogenic genes in EZ spheres (Fig. 3). EZ spheres rapidly increased the expression of PAX3 and PAX7, and their expressions were sustained up to 6 weeks. Before terminal differentiation, PAX3 and PAX7 expression was detected in EZ sphere cells, as seen previously in fetal skeletal muscle [16]; however, there was low expression of the muscle cell markers MYF5, MYOD, and MYOGENIN. After 2 weeks of terminal differentiation, the expression of MYF5, MYOD, and MYOGENIN increased, supporting our immunocytochemical observations (Fig. 2B–2D). Karyotype results confirmed that hES-derived EZ spheres at 10 weeks maintained normal chromosomes (supplemental online Fig. 1) as previously described [12]. Taken together, EZ sphere culture can propagate myogenic progenitors from hES cells. A high percentage of Pax7+ progenitor cells was observed in EZ spheres at 6 weeks; therefore, this time point was used for subsequent experiments.

Figure 3.

RT-PCR analysis of muscle marker genes in hES cell-derived EZ spheres. mRNA was isolated from undifferentiated feeder-dependent WA09 hES cells, cultured for 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks as EZ spheres or 6 weeks as EZ spheres, and then terminally differentiated for 2 weeks (6 week EZ + T.D.) and examined using RT-PCR to determine relative expression of pluripotent and myogenic markers. Fetal skeletal muscle mRNA was included as a control for fully differentiated muscle. Abbreviations: Myf5, myogenic factor 5; MyoD, myogenic differentiation 1; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; SKM, skeletal muscle; T.D., terminally differentiated.

High Concentration of FGF-2 Is Required for Myogenic Differentiation in EZ Spheres

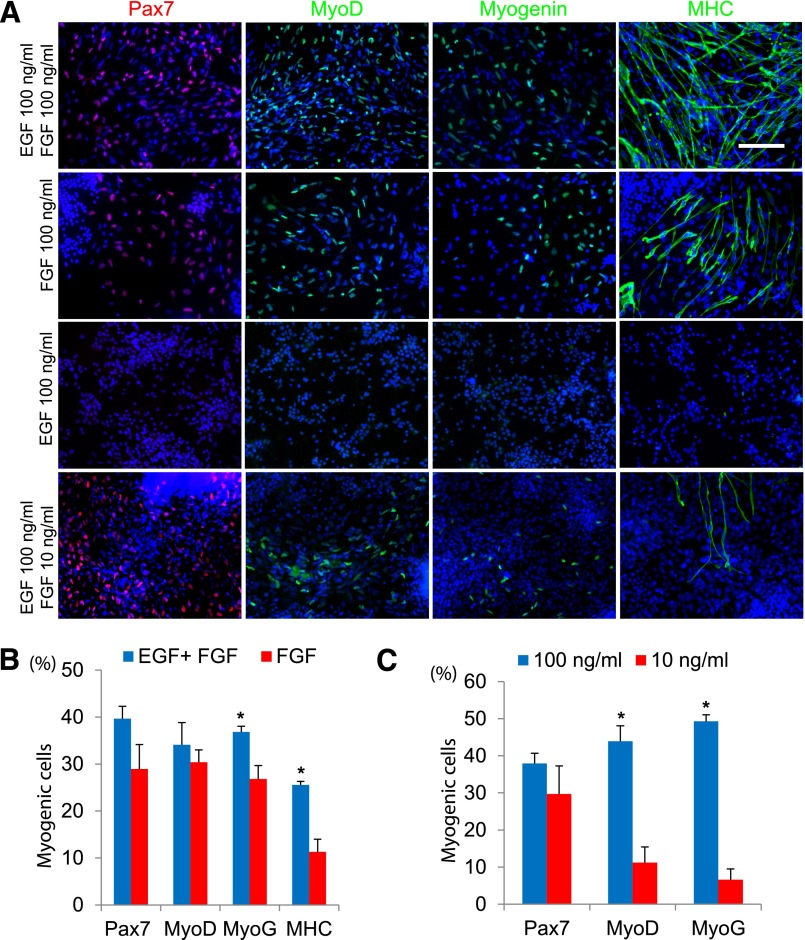

Whereas no growth factor was supplemented in the medium for EB formation, high concentrations of EGF and FGF-2 (100 ng/ml) were used for EZ sphere preparation. We questioned whether high concentrations of EGF, FGF-2, or a combination of the two were necessary for myogenic differentiation in EZ spheres. To test this, we placed hES cell colonies in expansion medium containing 100 ng/ml EGF and FGF-2, FGF-2 alone, or EGF alone and allowed to form EZ spheres. After 6 weeks, all spheres were dissociated, plated, and then differentiated for 2 weeks and stained for muscle cell markers (Fig. 4A): 39.7% ± 2.6% of cells were Pax7+ progenitors when cultured as EZ spheres with EGF and FGF-2 in combination; 29.0% ± 5.2% of the plated cells were Pax7+ when grown in FGF-2 alone (Fig. 4B). In addition, 34.1% ± 4.7% were MyoD+ and 36.8% ± 1.2% of the cells were MyoG+ when grown as EZ spheres with both EGF and FGF-2. Culturing in FGF-2 alone yielded 30.4% ± 2.6% MyoD+ cells. Significantly fewer MyoG+ cells (26.8% ± 2.8%, p < .01) were observed following differentiation from EZ spheres incubated with FGF-2 alone. Similarly, fewer cells stained for MHC from spheres incubated with FGF-2 only (11.3% ± 2.7%, p < .001) compared with those cultured in both EGF and FGF-2 (25.6% ± 0.7%). No cells from the spheres prepared with EGF alone were labeled with muscle progenitor or skeletal muscle markers (Fig. 4A, 4B).

Figure 4.

A high concentration of FGF-2 is required for myogenic differentiation in hES cell-derived EZ spheres. (A): Representative pictures of Pax7, MyoD, myogenin, and MHC staining of feeder-dependent WA09 hES cells cultured as EZ spheres for 6 weeks in EGF and FGF-2, FGF-2 alone, EGF alone, or EGF and a low concentration of FGF-2 (10 ng/ml), then terminally differentiated for 2 weeks. Pax7 is shown in red, MyoD, myogenin, and MHC are shown in green with Hoechst staining in blue. Scale = 100 µm. (B): hES-derived EZ spheres grown in EGF alone did not produce significant Pax7+, MyoD+, MyoG+, or MHC+ cells. In conditions in which EZ spheres were maintained in FGF-2 alone, Pax7+, MyoD+, MyoG+, and MHC+ cells were observed. The combination of EGF and FGF-2 did result in a trend toward increased numbers of Pax7+ and MyoD+ cells and significantly more MyoG+ and MHC+ cells compared with those generated in cultures containing FGF-2 alone (∗, p < .01). (C): Whereas 10 ng/ml EGF and FGF-2 resulted in a comparable percentage of Pax7+ cells, 100 ng/ml EGF and FGF-2 yielded a significantly higher percentage of MyoD+ and MyoG+ cells (∗, p < .001). Error bars = SEM. Abbreviations: EGF, epidermal growth factor; FGF-2, fibroblast growth factor-2; hES, human embryonic stem cells; MHC, myosin heavy chain; MyoD, myogenic differentiation 1; MyoG, myogenin.

Traditional methods have used 10–20 ng/ml EGF and/or FGF-2 to drive the proliferation of cultured cells [27, 28]. We next asked whether a low concentration of growth factors is sufficient to propagate myogenic progenitors. Human embryonic stem (ES) cell colonies were cultured as EZ spheres in either low (10 ng/ml each) or high (100 ng/ml each) concentration of FGF-2 and EGF. After 6 weeks, the spheres were dissociated, plated on coverslips, and then differentiated for 2 weeks. There was no difference in the number of Pax7+ cells differentiated from EZ spheres cultured in 10 ng/ml EGF and FGF-2 (29.7% ± 7.6%) compared with 100 ng/ml EGF and FGF-2 (37.9% ± 2.7%) (Fig. 4A, 4C). By contrast, 10 ng/ml EGF and FGF-2 EZ spheres resulted in strikingly fewer MyoD+ (11.2% ± 4.2%, p = .003) and MyoG+ (6.6% ± 2.8%, p < .0001) cells compared with those incubated in 100 ng/ml EGF and FGF-2 (MyoD+: 43.9% ± 4.2%; MyoG+: 49.3% ± 1.7%). Together, these results suggest that a high concentration of FGF-2 is necessary for the expansion of myogenic progenitors in EZ spheres. Although EGF itself does not result in significant numbers of myogenic cells, it appears to have a positive impact on myogenic differentiation under these culture conditions.

iPS Cells Can Generate Skeletal Muscle Cells Using Sphere-Based Cultures

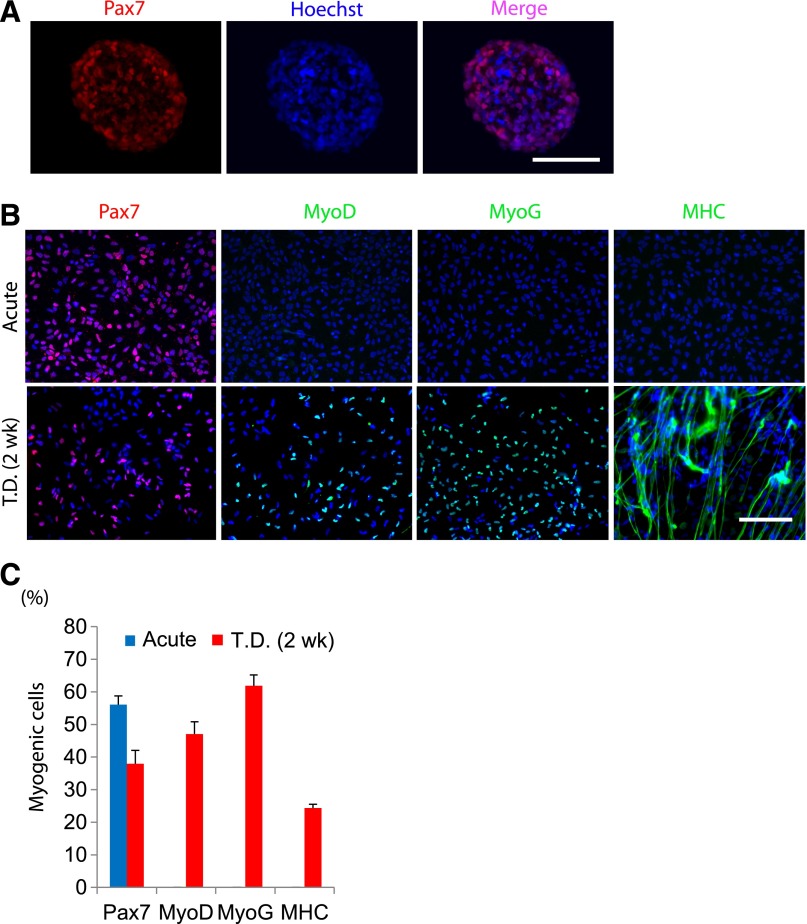

Induced pluripotent stem cells possess similar cellular characteristics to ES cells with potential for differentiation into a variety of cell types [22, 29, 30]. We investigated whether the EZ sphere culture method is applicable for myogenic differentiation of human iPS cells. Wild-type iPS cells (IMR90) established from primary fibroblasts derived from embryonic lung tissue [22] were used to generate iPS cell colonies and were allowed to form EZ spheres in medium supplemented with high concentrations of EGF and FGF-2. Sphere cryosections contained Pax7-expressing cells (Fig. 5A). The iPS-derived spheres were then dissociated, plated on coverslips, and differentiated for 2 weeks. Similar to the human ES-derived spheres, the cells prepared from iPS-derived EZ spheres showed high potential of myogenic differentiation (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Derivation of muscle progenitors from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells by EZ sphere culture. Human iPS cells were cultured under feeder-free conditions, and the colonies were then lifted and transferred into EZ sphere expansion medium. (A): Pax7+ staining was detected in EZ spheres following 6 weeks of spherical culture, as can be seen in cryosection of iPS cell-derived EZ sphere (prior to dissociation, plating, and terminal differentiation). (B): EZ spheres were then dissociated, terminally differentiated for 2 weeks, and immunostained with muscle markers Pax7, MyoG, and MyoD. Scale = 100 µm. (C): Quantification of immunofluorescence of Pax7, MyoG, and MHC from control iPS cell lines (IMR90). Error bars = SEM. Abbreviations: MHC, myosin heavy chain; MyoD, myogenic differentiation 1; MyoG, myogenin; T.D., terminally differentiated.

Before terminal differentiation, the iPS cell-derived progenitors were 56.1% ± 2.6% Pax7+, but other myogenic markers such as MyoD, MyoG, and MHC were not detectable. After 2 weeks of terminal differentiation, Pax7+ (38.0% ± 4.1%), MyoD+ (47.0% ± 3.8%), MyoG+ (61.9% ± 3.3%), and MHC+ (24.4% ± 1.1%) cells were observed (Fig. 5C).

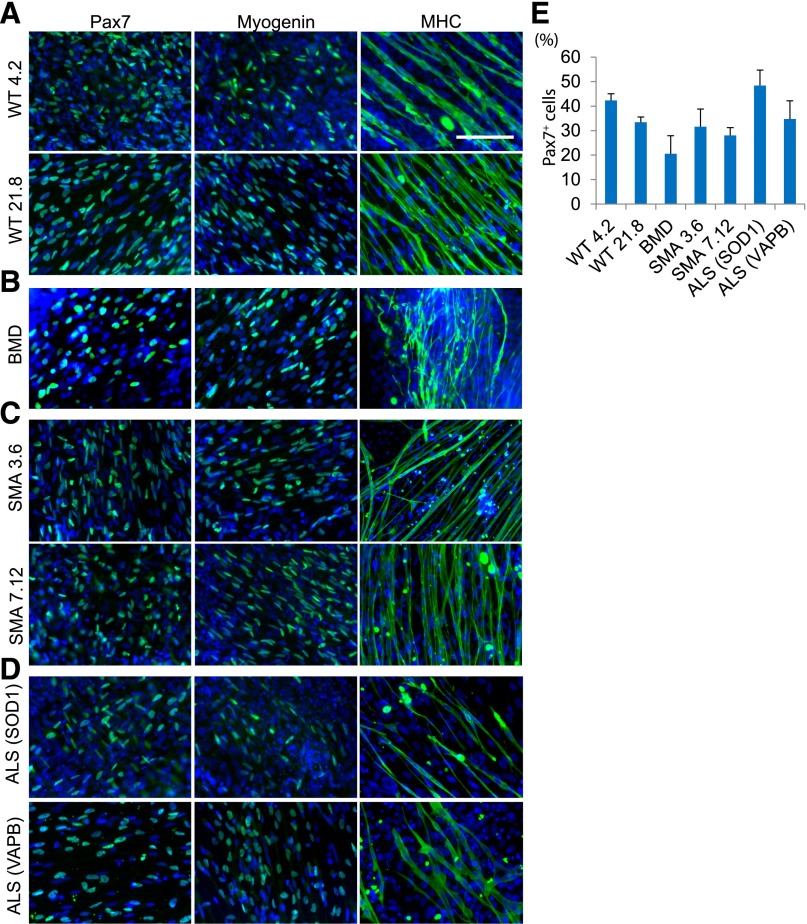

Skeletal Muscle Cells Can Be Efficiently Propagated From Disease-Specific iPS Cells Using EZ Spheres

A major advantage of using iPS technology is the ability to generate iPS cell lines derived from patients suffering from various inherited and sporadic diseases. If muscle cells or myofibers are efficiently prepared from patient-derived iPS cells with neuromuscular disorders, they may be a valuable resource for disease modeling and drug screening in vitro. We assessed whether we could propagate myogenic progenitors from patient-specific iPS cell lines with different neuromuscular disorders (Fig. 6). We analyzed two iPS cell lines derived from healthy donors (WT 4.2 and 21.8) (Fig. 6A), patients with Becker’s muscular dystrophy (Fig. 6B) [31], type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (Fig. 6C) [11, 13], and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with a mutation in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) or vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B/C (VAPB/ALS8) (Fig. 6D) [32]. EZ spheres from patient-specific iPS cells were prepared as described above. After 6 weeks of EZ sphere culture, we tested the ability of the cells to differentiate into myogenic cells. We found Pax7+, MyoG+, and multinucleated MHC+ myotubes in differentiated cells derived from all patient-specific iPS lines. Furthermore, in differentiated myotubes, we found α-Bungarotoxin-positive postsynaptic densities (supplemental online Fig. 2) and could observe sporadic myofiber twitching in culture (supplemental online Videos 1, 2). We did not observe any obvious phenotypic differences in the myotubes generated from any of the diseased patient-specific lines. As is the case with neural differentiation from iPS cell lines [33], there appears to be some interline variation in differentiation efficiency based on Pax7+ cell count analysis; however, the variations observed in the disease cell lines were not found to be significantly different from wild-type control lines (Fig. 6E). Nevertheless, as in ES and wild-type iPS cells, patient-specific iPS cells can differentiate into skeletal muscle cells using EZ sphere cultures.

Figure 6.

Induction of muscle differentiation from patient-derived iPS cells. Disease-specific human iPS cells were cultured for 6 weeks as EZ spheres, dissociated, plated on laminin-coated coverslips, and terminally differentiated for 2 weeks before being fixed and stained for Pax7, myogenin, and MHC. Control wild-type iPS lines 4.2 and 21.8 (A), BMD (B), and two independent SMA lines (3.6 and 7.12) (C) were examined for myogenic potential. (D): Two independent ALS lines were examined, one with an SOD1 mutation and the other with the VAPB mutation. All lines were able to generate high levels of Pax7+ cells (left column), MyoG+ (middle column), and MHC+ cells (right column). All disease-specific iPS cell lines were originally cultured under feeder-free conditions. (E): Quantification of Pax7+ cells from each patient-specific iPS cell line. Error bars = SEM. Abbreviations: ALS (SOD1), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis due to mutation of superoxide dismutase 1; ALS (VAPB), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis due to vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B/C; BMD, Becker’s muscular dystrophy; iPS, induced pluripotent stem cells; MHC, myosin heavy chain; MyoG, myogenin; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; WT, wild type.

EZ Sphere Culture of Pluripotent Stem Cells Results in a Mixed Population of Myogenic and Neural Progenitors

As the EZ sphere culture was initially developed to expand neural progenitor cells [12], we tested whether the ES-derived EZ spheres, expanded under the conditions described in this study, also contained neural progenitor cells. Acutely dissociated EZ spheres containing cells positive for Pax7 were found to be 72.8% ± 4.9% positive for Nestin, a neural stem cell marker, but there was no expression of βIII-tubulin (TuJ1), a marker of early differentiated neurons (supplemental online Fig. 3A, 3C). Following dissociation and plating of the cells in differentiation medium, 50.5% ± 8.0% of the cells remained positive for Nestin, and TuJ1 expression was observed in 29.1% ± 1.3% of cells (supplemental online Fig. 3B, 3C). These results indicate that EZ spheres contain a mixed population of neural and myogenic progenitor cells, which may account for the observed myofiber twitching (supplemental online Videos 1, 2).

Discussion

Here, we report that sphere-based cultures of human pluripotent stem cells expanded in medium containing high concentrations of FGF-2 and EGF can propagate myogenic progenitors. This culture protocol is applicable for a variety of hES and iPS cells regardless of their dependency on feeder cells during colony expansion. One major advantage of EZ sphere cultures is that a large quantity of myogenic progenitor cells can be prepared without additional manipulations such as conditional expression of myogenic genes and cell sorting, two techniques that may limit clinical use of myogenic progenitors. Because EZ spheres show a capacity for cellular division, as demonstrated by Ki67 immunocytochemistry (Fig. 2A), progenitor cells can be expanded on a large scale through passaging. In terms of differentiation efficiency, our protocol is not directly comparable to previously described methods that use genetic modification and cell sorting. However, the results from this study provide significant and novel information for improving myogenic progenitor preparation, under defined conditions, directly from human pluripotent stem cells.

Although EZ sphere cultures can propagate a large number of early myogenic progenitors, this method cannot maintain a large number of progenitors indefinitely. We examined the number of cells positive for early myogenic progenitor and skeletal muscle cell markers in EZ spheres at specific time points. During the expansion phase, the Pax7+ population of cells increases and peaks by 6 weeks but then decreases over time, dropping off almost completely by 12 weeks in culture. These data indicate that these progenitor cells gradually begin to spontaneously differentiate into myoblasts and myotubes while in EZ sphere culture. Although it is still uncertain whether this “stage shift” of myogenic progenitors reflects the developmental timeline of human skeletal muscle, additional optimization may allow us to prevent this loss of myogenic progenitors after a long-term expansion. The addition of bone morphogenetic protein 4 may improve maintenance of the myogenic progenitors. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 is known to be expressed in the lateral-plate mesoderm during normal development and maintains the muscle progenitor state [34]. Another possibility might be Wnt. Activation of Wnt signaling could sustain a myogenic progenitor state [35]. In fact, high concentrations of Wnt and FGF-2 have been shown to restrict cells to a mesenchymal, progenitor state during development [36]. This process may act through the Notch pathway, which has been shown to be involved in the generation of somites [37].

Myogenic progenitor cell generation using EZ spheres requires a high concentration of FGF-2. In this study, we show that FGF-2 is critical because its removal from the expansion medium (FGF 0 ng/ml, EGF 100 ng/ml) resulted in virtually no myogenic progenitor cells (Fig. 4B). Reducing the concentration of FGF-2 in the expansion medium to 10 ng/ml followed by differentiation yielded few MyoD+ or MyoG+ cells. Because FGF-2 is known to bind to and activate all members of the FGF receptor family (FGFR) [38], in this study, only a high concentration of FGF-2 resulted in myogenic progenitors differentiating into muscle cells. It is possible that FGF-2 may not be the specific FGF responsible for guiding pluripotent stem cells toward a myogenic progenitor lineage. It is likely that FGF-2 is simply activating all FGFRs. Future studies focusing on identifying the FGF/FGFR combination(s) best suited to produce myogenic progenitors from pluripotent stem cells will be critical. For example, it has been previously shown that fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (FGFR4) and FGF6 are highly expressed in the muscle and that FGFR4 is necessary for limb muscle development [39, 40]. Furthermore, FGFR4 expression increases as myoblasts differentiate and fuse to form myotubes [41]. Removal of EGF from the expansion medium resulted in reduced or delayed myogenic cell generation but did not abolish it. We conclude that EGF is not necessary to generate myogenic progenitor cells, but it appears to produce a trend toward increased myogenic progenitor differentiation efficiency, suggesting a synergistic effect with FGF-2.

Although a large set of myogenic progenitors and multinucleated myotubes was detected in the differentiated cells, this sphere-based protocol is not specific for myogenic differentiation. Not all of the cells in EZ spheres expressed skeletal muscle marker proteins. Primarily, the EZ sphere method has been established as a method that generates pre-rosette neural stem cells directly from hES and iPS cells [10–13]. EZ spheres retain the potential to form neuronal rosettes and consistently differentiate into a range of central and peripheral neural lineages. Neural stem cells represent a major population in our EZ spheres along with the myogenic progenitor cells. Therefore, our spherical aggregate cultures are heterogeneous with different types of stem cells and progenitors. Another possibility is that the cells in EZ spheres may resemble axial stem cells, which are bipotent for the posterior neural plate and paraxial mesoderm during the axial development of embryos [42, 43]. Some recent studies have established a genetic and cellular relationship between neurogenesis and myogenesis [42, 43]. More detailed studies are required to investigate whether myogenic progenitors and neural stem cells overlap or are differentially distributed in EZ spheres. Together, the results from these studies could provide important implications for how we can improve the efficiency of myogenic progenitor preparation using hES- and iPS-derived EZ spheres.

In this study, we used iPS cell lines generated from patients with neuromuscular diseases and successfully differentiated them into skeletal muscle cells using sphere-based cultures. This contribution is significant because of the potential advantages of using patient-derived progenitors for in vitro disease modeling and drug development. In neuromuscular diseases such as muscular dystrophy, ALS, or SMA, muscle function is impaired, indirectly by pathology of nerves innervating the muscle and disruption of neuron/muscle attachments, or directly due to muscle pathology. Despite devastating consequences, effective treatment strategies are not available for any major neuromuscular disease. Skeletal muscle cells derived from patient-specific iPS lines would be a valuable resource for studying neuromuscular disease mechanisms and testing potential drug therapies. Although our initial examination of these lines did not yield obvious abnormalities in myogenic differentiation, some variations were observed in the number of myogenic progenitors and mature myotubes between the lines. It will be important to identify whether these variations in muscle differentiation efficiency are caused by the disease background. It is also possible that variations primarily exist in the iPS lines, a phenomenon previously observed during neural specification [33]. In addition, if EZ spheres possess both neural and muscle lineages, one potentially attractive application would be to differentiate them into motor neuron/skeletal muscle cocultures to examine neuromuscular connections in vitro. A more in-depth analysis of neuromuscular formations and skeletal muscle homeostasis and physiological function from disease-specific iPS cells may help provide a platform for drug screening and further characterization of disease progression.

Conclusion

Sphere-based cultures of human pluripotent stem cells, expanded in medium containing high concentrations of FGF-2 and EGF, can propagate myogenic progenitors from hES cells and healthy and disease-specific iPS cells. However, although EZ sphere cultures can propagate a large number of early myogenic progenitors, this method cannot maintain progenitors indefinitely. Nevertheless, these findings demonstrate the potential for using hES and iPS cells to directly derive skeletal muscle cells for cell-based therapies targeting skeletal muscle for neuromuscular disorders and disease modeling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the ALS Association (PPHF35, A.D.E., J10IZ9, M.S.), NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R21NS06104, M.S.), the University of Wisconsin Foundation (M.S.), and Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin (A.D.E.). The project was also supported in part by the Clinical and Translational Science Award program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources Grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant 9U54TR000021 (M.S.). The anti-Pax7, anti-myogenin (F5D), and anti-myosin heavy chain (MF20) antibodies were obtained from the DSHB developed under the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the University of Iowa. The ALS VAPB iPS cells were provided by Dr. Alysson Muotri at the University of California, San Diego.

Author Contributions

T.H. and J.V.M.: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; J.M.V.D.: collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing (primary), final approval of manuscript; A.D.E. and M.S.: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hosoyama T, Van Dyke J, Suzuki M. Applications of skeletal muscle progenitor cells for neuromuscular diseases. Am J Stem Cells. 2012;1:253–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tedesco FS, Cossu G. Stem cell therapies for muscle disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:597–603. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328357f288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salani S, Donadoni C, Rizzo F, et al. Generation of skeletal muscle cells from embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells as an in vitro model and for therapy of muscular dystrophies. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:1353–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao L, Tang W, Wei Y, et al. Highly efficient derivation of skeletal myotubes from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:1109–1119. doi: 10.1007/s12015-012-9413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barberi T, Bradbury M, Dincer Z, et al. Derivation of engraftable skeletal myoblasts from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:642–648. doi: 10.1038/nm1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Awaya T, Kato T, Mizuno Y, et al. Selective development of myogenic mesenchymal cells from human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darabi R, Gehlbach K, Bachoo RM, et al. Functional skeletal muscle regeneration from differentiating embryonic stem cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:134–143. doi: 10.1038/nm1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darabi R, Santos FN, Filareto A, et al. Assessment of the myogenic stem cell compartment following transplantation of Pax3/Pax7-induced embryonic stem cell-derived progenitors. Stem Cells. 2011;29:777–790. doi: 10.1002/stem.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darabi R, Arpke RW, Irion S, et al. Human ES- and iPS-derived myogenic progenitors restore DYSTROPHIN and improve contractility upon transplantation in dystrophic mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.HD iPSC Consortium Induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Huntington’s disease show CAG-repeat-expansion-associated phenotypes. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:264–278. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, Jr., et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009;457:277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebert AD, Shelley BC, Hurley AM, et al. EZ spheres: A stable and expandable culture system for the generation of pre-rosette multipotent stem cells from human ESCs and iPSCs. Stem Cell Res (Amst) 2013;10:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sareen D, Ebert AD, Heins BM, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis blocks human motor neuron cell death in a stem cell model of spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamaki T, Akatsuka A, Okada Y, et al. Growth and differentiation potential of main- and side-population cells derived from murine skeletal muscle. Exp Cell Res. 2003;291:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamaki T, Okada Y, Uchiyama Y, et al. Skeletal muscle-derived CD34+/45− and CD34−/45− stem cells are situated hierarchically upstream of Pax7+ cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:653–667. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosoyama T, Meyer MG, Krakora D, et al. Isolation and in vitro propagation of human skeletal muscle progenitor cells from fetal muscle. Cell Biol Int. 2013;37:191–196. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarig R, Baruchi Z, Fuchs O, et al. Regeneration and transdifferentiation potential of muscle-derived stem cells propagated as myospheres. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1769–1778. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei Y, Li Y, Chen C, et al. Human skeletal muscle-derived stem cells retain stem cell properties after expansion in myosphere culture. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:1016–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westerman KA, Penvose A, Yang Z, et al. Adult muscle “stem” cells can be sustained in culture as free-floating myospheres. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1966–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitne-Neto M, Machado-Costa M, Marchetto MC, et al. Downregulation of VAPB expression in motor neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of ALS8 patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3642–3652. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludwig TE, Bergendahl V, Levenstein ME, et al. Feeder-independent culture of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods. 2006;3:637–646. doi: 10.1038/nmeth902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludwig TE, Levenstein ME, Jones JM, et al. Derivation of human embryonic stem cells in defined conditions. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:185–187. doi: 10.1038/nbt1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svendsen CN, ter Borg MG, Armstrong RJ, et al. A new method for the rapid and long term growth of human neural precursor cells. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;85:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson AD, Suzuki M, Svendsen CN. A high concentration of epidermal growth factor increases the growth and survival of neurogenic radial glial cells within human neurosphere cultures. Stem Cells. 2008;26:348–355. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson AD, Svendsen CN. Low concentrations of extracellular FGF-2 are sufficient but not essential for neurogenesis from human neural progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;33:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lautenschlaeger J, Prell T, Grosskreutz J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the ER mitochondrial calcium cycle in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13:166–177. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2011.641569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu BY, Weick JP, Yu J, et al. Neural differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells follows developmental principles but with variable potency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4335–4340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910012107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pourquié O, Coltey M, Bréant C, et al. Control of somite patterning by signals from the lateral plate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3219–3223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parr BA, Shea MJ, Vassileva G, et al. Mouse Wnt genes exhibit discrete domains of expression in the early embryonic CNS and limb buds. Development. 1993;119:247–261. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aulehla A, Pourquié O. Signaling gradients during paraxial mesoderm development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000869. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmann M, Schuster-Gossler K, Watabe-Rudolph M, et al. WNT signaling, in synergy with T/TBX6, controls Notch signaling by regulating Dll1 expression in the presomitic mesoderm of mouse embryos. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2712–2717. doi: 10.1101/gad.1248604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X, Ibrahimi OA, Olsen SK, et al. Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family. The complete mammalian FGF family. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15694–15700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601252200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kästner S, Elias MC, Rivera AJ et al. Gene expression patterns of the fibroblast growth factors and their receptors during myogenesis of rat satellite cells. J Histochem Cytochem 2000;48:1079–1096. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Marics I, Padilla F, Guillemot JF, et al. FGFR4 signaling is a necessary step in limb muscle differentiation. Development. 2002;129:4559–4569. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu S, Zheng L, Trinh DK et al. Distinct transcriptional control and action of fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 in differentiating skeletal muscle cells. Lab Invest 2004;84:1571–1580. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Fong AP, Yao Z, Zhong JW, et al. Genetic and epigenetic determinants of neurogenesis and myogenesis. Dev Cell. 2012;22:721–735. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takemoto T, Uchikawa M, Yoshida M, et al. Tbx6-dependent Sox2 regulation determines neural or mesodermal fate in axial stem cells. Nature. 2011;470:394–398. doi: 10.1038/nature09729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.