Abstract

While emotion is a central component of human health and well-being, traditional approaches to understanding its biological function have been wanting. A dynamic systems model, however, broadly redefines and recasts emotion as a primary sensory system—perhaps the first sensory system to have emerged, serving the ancient autopoietic function of “self-regulation.” Drawing upon molecular biology and revelations from the field of epigenetics, the model suggests that human emotional perceptions provide an ongoing stream of “self-relevant” sensory information concerning optimally adaptive states between the organism and its immediate environment, along with coupled behavioral corrections that honor a universal self-regulatory logic, one still encoded within cellular signaling and immune functions. Exemplified by the fundamental molecular circuitry of sensorimotor control in the E coli bacterium, the model suggests that the hedonic (affective) categories emerge directly from positive and negative feedback processes, their good/bad binary appraisals relating to dual self-regulatory behavioral regimes—evolutionary purposes, through which organisms actively participate in natural selection, and through which humans can interpret optimal or deficit states of balanced being and becoming. The self-regulatory sensory paradigm transcends anthropomorphism, unites divergent theoretical perspectives and isolated bodies of literature, while challenging time-honored assumptions. While suppressive regulatory strategies abound, it suggests that emotions are better understood as regulating us, providing a service crucial to all semantic language, learning systems, evaluative decision-making, and fundamental to optimal physical, mental, and social health.

Key Words: Emotion, selfregulation, morality, development, feedback, bio-values, sensitivity, computational dynamics, cybernetics, connectionism, complexity, self-organization, epigenetics

EMOTION: THE SELF-REGULATORY SENSE

The wisdom of Jeremy Bentham has oft been quoted: “Man has been placed under the governance of two sovereign masters: pleasure and pain.”1

Despite this insight, philosophers and psychologists remain haunted by the question: What is the biological Junction of emotion? It has been difficult to disentangle emotion from biological drives and physiological responses,2 from motivational appetites and defenses,3 from cognitive appraisals4,5 or moral intuitions6; to make sense of the cultural similarities and differences,7 or to reconcile divergent theories8,9; so difficult, that theorizing about emotion as a functional whole has largely been abandoned. As one critic put it: “My central conclusion is that the general concept of emotion is unlikely to be a useful concept in psychological theory.”10

The purpose here is to suggest the opposite: That the problem with the traditional approach is that it has been overly specific, narrow, and anthropomorphic. Indeed, emotion theory remains reminiscent of the Sufi tale of the elephant and the blind men,11 with each theorist grasping a portion, but unable to see the phenomenon in its entirety. Yet rather than integration and synthesis, the trend continues of “dissecting the elephant”12 into ever-smaller fragments devoid of coherent biological function. As a result, emotional feelings and behaviors are written off as outdated animal vestiges, “ill-suited to modern exigencies,”13 to be suppressively regulated by one's conscious rational mind, if not pharmaceutical intervention.

But with recent revelations from a variety of disciplines, a formerly hidden—yet astoundingly elegant—functional elephant looms large. The current proposal is that the function of emotion is the very sort of “governance” that Bentham suggested, that of self-regulation. But in this usage, “self-regulation” refers primarily to the biologically bottom-up autopilot variety of regulatory control processes, and implies that subordination to our hedonic masters is actually a very good thing. It will be argued that our limited ability to suppressively regulate our emotions is because they are actually regulating us, and from a much deeper, wiser, evolutionary evaluative authority.

To sketch this ancient function, we must pan much further back in our phylogenetic history, and delve deeper into the biophysical regulatory processes of living systems, tracing the emergent trajectory of the emotional system from its simplest mechanistic roots to its present state of elaborate multi-tiered complexity.

To linguistically accommodate the entire functional elephant, we must broadly redefine the category of “emotion” to include “affect” and innate “hedonic” approach/avoid behavior, locating its function in the arena of regulatory signaling and motor control mechanisms. We must specifically focus the inquiry upon feedback loops, recursive, cyclic and reciprocally deterministic, stimulus-response relationships; those that give rise to the earliest forms of “computation”—information processing—in nature; those that inform what will be termed “self-regulated” behavioral agency in organisms as simple as a single-celled bacterium, and those still evident in the cell-signaling cascades that convey identity-relevant information across all levels of organization within complex multicellular organisms—including humans.

Indeed, many theorists have pointed out the primary “relevance detection,”14 “relevance signaling,”15 and “informational,”16–18 functions of emotion, as well as those of resource mobilization and conservation,19 and the organization and facilitation of adaptive behavioral responses.20,21 Likewise, many have noted the categorizational,22 motivational23,24 goal relevant nature15 and primacy25 of affect. In fact, the idea of biophysical feedback itself has a rich history in emotion theory2,26–37 in which Carver and Scheier38,39 specifically noted feedback as a self-regulatory “control process” underlying affect. Recent revelations, however, about bottom-up “self-organization”40,41 and interactive epigenetic mechanisms42 in evolution, can finally root these insights in solid biophysical ground, as well as offer significant clarifications and enhancements.

Indeed, building upon these contributions, I propose that emotion can only be envisioned as a unified functional whole when reconceived as an entire sensory system—a primary somatosensory system that guides biologically adaptive self-regulation. Not a newly evolved or sixth sense43 but perhaps the first sensory system to have emerged on the evolutionary stage, born of the simple molecular stimulus-response networks that regulate metabolic and genetic activity and crude sensorimotor behavioral control in single-celled organisms. Such primal self-regulatory “sensations” are functionally homologous to, and still manifest within, cell-signaling mechanisms in multicellular organisms that integrate and maintain “the self” at all levels of complexity—rooted as deeply as those that control the navigation and differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into their various tissue environments during embryonic self-development. In other words, while they may have emerged as sensorimotor regulators in the earliest life forms, the same principle mechanisms still constitute the signaling and communication systems, the self-organizing language—the self-regulatory music, if you will—of the human body.

In whatever form of “subjective experience” these original sensations may have yielded, in functional terms they would deliver primal perceptions of time, space and self—an inaugural glimmer of a body-self moving within its not-self surroundings, at some point constituting the “feeling of being”44 or “how it feels to be alive.”45 Hence, in far more complex bodies in motion (mammals, other primates, and humans), each emotional feeling perception still reflects “a wave of bodily disturbance,” or the “bodily affections,”2 or “the feeling of what is happening.”46,47

Key to our discussion, however, is that from their emergence forward, these informational sensations have contained “felt evaluations,”48,49 the symbolic binary opposites that we experience as pleasure and pain, the feel good/feel bad hedonic valence of emotion. These “positive and negative” binary opposites offer real-time computational representations of the ongoing dynamic orchestration of whole-body coherence, with harmonically resonant and dissonant reverberations ringing forth when environmental perturbations require self-regulatory responses. The current proposal is that the binary hedonic logic within these felt evaluations offers nothing less than a biological value system, informing us of universally optimal and deficit states of balanced being and becoming—a natural value system rooted in the biophysical requirements for life itself.

At a more concrete level of analysis, the positive and negative hedonic categories equate with “eustress” and “distress” signals respectively50 and locate the emotional sense as an intimate affiliate of the immune system (recently declared a sensory system itself).51 Adding, however, that its core physiological “self” or “not-self distinction is tethered deeper still in genetic and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, the bottom-up biological processes that ultimately inform the fundamentally “self-relevant”34 or “motivationally relevant”52 nature of affective stimulus, and underscore the notorious bidirectional connection between emotion and physical health.53–59 As such, these core self-regulatory feedback processes in humans also undergird the requirement for “regulatory fit”60 within and between goals, or concordance within the “psychological immune system”61 and other self-balancing processes such as “cognitive dissonance”62 although, as will be argued, emotional dissonance may be more biophysically accurate.

The self-regulatory functional elephant will also acknowledge emotion as the unsung hero in conditioned learning,63,64 in subliminal “priming”65 and embodied66 implicit67 or unconscious cognition,68 implicit bias69,70 as well as nonconscious, “auto pilot” self-regulation71; in cognitive identity formation,72,73 self-perception,74 self-concept,75 self-serving biases,76 and self-enhancement motives77: in needs for and feelings about self-determinism,78 self-efficacy,79 selfesteem,80,81 self-expansion82 and urges toward selfactualization83; all of which are elegantly integrated within emotional sensory perceptions and their coupled behavioral responses.

In short, the goal here is to sketch a new image for the box of the puzzle of emotion, one where emotion takes its rightful place as a sense; one depicting common feeling tones on par with colors, tastes, scents and sounds. One in which feeling perceptions, ranging from rudimentary pleasure and pain, through basic joy and sadness, to complex pride, shame, admiration and envy, serve as sensory signals offering an elegant palate of evaluative information about our adaptive fitness in the immediate environment. Indeed, the proposal is not only that emotion should be reframed as a sensory system, but that emotion should also be acknowledged as the biological grandfather of all the senses, and that its hedonic self-regulatory logic remains encoded within all other senses—a simple logic, yet one so crucial as to have been conserved throughout our entire evolutionary history. Acknowledging how our presently elaborate, cognitively enriched, emotional perceptions still bubble up from their ancient self-regulatory wellspring, offers quite profound implications for the medical community, as well as the social sciences in general. Indeed, it allows the scientific construct of emotion to come full circle, rejoining with the so-called naive realism of immediate human experience, yet offering direct inroads to embodied knowledge, bountiful emotional intelligence, social intuition, and even moral reasoning.

But however elegant, these subjective manifestations cannot be separated from their objective counterpart, for each emotional sensory perception includes both an informational component and a coupled behavioral response. Indeed, in this new view, emotion is ground zero for all sensorimotor stimulus-response relationships, with the hedonic approach and avoid behavioral pattern—a pattern observable from the single celled ameba to the complex human84—serving as the primary empirical justification and departure point for our new story. A crucial point is that this crude sentience is contingent upon, and would follow from, the deterministic behaviors themselves, or as Marienberg put it: “the becoming aware of the capacity to act while acting.”85 In short, identifying the biological function of emotion requires taking Skinnerian behaviorism to all new reductionist levels—an inquiry into how approach and avoid behaviors emerge from the chemistry of living systems. Yet, when equipped with the lens of feedback control theory, the journey affords a primordial peek into the “black box,” offering a clear and detailed functional explanation of how innate (“unconditioned”) stimuli evoke “affect” itself—something decidedly lacking in emotion theory.9

This brief introduction begins with a redefinition of emotion within this broadened context, turning next to its biophysical substrates and underlying feedback dynamics, and identifying the source of what will be termed “the self-regulatory code.” The hedonic behavior of the Escherichia coli (E coli) bacterium is offered next as an example of the ancient mechanisms (both function and form), followed by a description of the modern neural, perceptual, and behavioral manifestations of the emotional sense; and ending with a brief discussion of the implications for human health. Indeed, to formally acknowledge emotion as a primal sensory system invites critical reevaluation of many deeply engrained linguistic conventions, beliefs, and practices.

EMOTION: A BROADENED DEFINITION

To begin, I broadly redefine “emotion” within the context of digital stimulus-response behavioral phenomena, including any biochemical processes and physical mechanisms, laws and forces that determine their cause and effect relationship. By digital, I mean any sort of distinctly binary values, symmetrically isomorphic or oppositional qualities, structures, bistable states or transformative actions that exist in nature that can be harnessed as meaningfully symbolic cues further up the evolutionary ladder. In other words, such binary values (ie, positive/negative electrical charges, north/ south magnetic poles, left/right symmetries, cis/trans isomers, bistable attractors, etc) can serve as digital information “bits” for computational processing. In fact, an if-then stimulus-response logic is there for the taking in the orderly behavior of electrons, behavior that ultimately drives all higher scale chemical reactions—from the bonding and anti-bonding behaviors of molecules, through the transitional and equilibrium states of metabolic networks, to the signaling cascades and on/off regulatory switching of genetic processes. In short, the sensory informational components of emotion can only be appreciated against the backdrop of the in-forming, trans-forming, stimulus-response dynamics of matter in motion.

These binary opposites, deterministic behavioral laws, and self-organizing dynamics underlie the “regulation” part of the self-regulatory function of emotion, as they deliver bottom-up “order for free.”41 As we will see, they also deliver an elegant stimulus-response choice-making logic—whether or not any sentient life form has yet emerged to exploit it. The “self” part of the self-regulatory function, and the emergence of what is defined herein as emotion proper, is rooted in iterative, self-reflexive, feedback loops. Indeed, feedback provides the crucial evolutionary link between the deterministic, self-organizing “happening” behavior of non-living matter and the self-regulatory agency—goal driven “doing” behavior—of living systems. As such, feedback also provides the conceptual linchpin between the physically impartial “positive” and “negative” binaries in nature and the warm-fuzzy/cold-prickly evaluative categories of personal experience.

What Is Feedback?

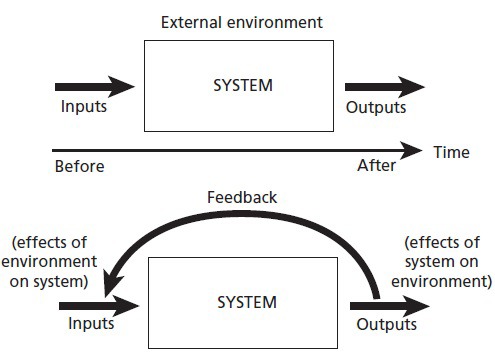

Feedback, in terms of general function, refers to communication and control mechanisms prevalent in both mechanical and organic systems—those that report upon (inform) and alter (transform) the relationship between a given system and its immediate environment.86 Feedback is cyclic, as it occurs in circular stimulus-response loops where the output of a system is fed back into itself, serving as a stimulus for a subsequent round of output responses (See Figure 1, two systems with and without feedback). In this primary mechanical context, however, the term “self” is synonymous with the system in question, whether it be an atom, a molecule, a cell, an organ system, or an organism interacting with its local “not-self” environment. Equating “system” with “self,” of course, does not yet imply sentience or consciousness, but is simply a relative location in space, as well as a subjective center in time serving as both source and sink for energy and information exchange, and therefore, ground zero for both stimulus and response. Nonetheless, as Figure 1 suggests, feedback processes conceptually juxtapose time, space, and self in unadulterated ways, offering a simple yet elegant springboard for our discussion of emotion as a primal self-regulatory sense.

Figure 1.

Feedback. (Adapted from de Rosnay, 1979.)

But the feedback mechanism is also central to the aforementioned “regulatory” side of the self-regulatory emotional elephant—as well as the emergence of sentience itself. For feedback loops are the basic building blocks of cybernetic systems,87–89 also known as “complex adaptive systems,”90 “dissipative structures,”91 and self-making “autopoietic” systems92—which include all life forms. As the original “science of control and communication,”89 cybernetics united regulatory control theory with physical information theory, investigating how materially embedded systems can make observers and actors possible—how mechanically in-forming and trans-forming processes give rise to subjective information and behavioral control in living systems. In fact, in terms of thermodynamics, feedback is associated with both entropy (chaotic disorder) and the “negentropic”93 ordering principles that underlie the physical definition of information itself. (As Nobel laureate Manfred Eigen suggested: “If you ask where does information come from and what its meaning is, the answer is: information generates itself in feedback loops.”94)

In short, feedback is quite literally a key computational in-forming and trans-forming engine in nature, with feedback regulation subserving all biological signaling systems,95,96 underlies biorhythms and biological clocks97 and molecular and neural circuitry,98 is essential to all genetic, epigenetic,99 immune.100–102 and even sensory mechanisms,103 as well as goal-directedness and behavioral control.104

The functional architecture of these ordering and disordering principles—from electromagnetic polar shape shifting transitions to favored-state energetic balances—was elegantly depicted by the founder of both cybernetics and general systems theory Ross Ashby, in his original “homeostat,”105 an electronic device that provided a concrete example of adaptive control. It was a crude learning or “thinking” machine, one that combined both analog and digital information processing in order to maintain stability in the face of widely varied and highly challenging environmental perturbations106 —an informational architecture central to our discussion. In fact, the auto-induced, cyclic, self-reflexive nature of feedback, and its ubiquitous role in selforganizing and self-regulatory processes places it center stage for both “self” and “regulation” pieces of the self-regulatory function. I will demonstrate herein how the hedonic valence of emotion—with its definitively “self-relevant”34 stimulus signals—emerges directly from positive and negative feedback loops. Indeed, they come in two types, providing the binary opposites for digital “choice-making” in what I call the self-regulatory code, still evident in the sensorimotor architecture of living systems, much as Ashby had envisioned.

For now, emotion as a self-regulatory sense emerges because feedback “happens” across the great chain of being, the “noise”107 of its simple computational dynamics having been harnessed by self-replicating systems, and conserved, honed, and elaborated upon by natural selection. As such, the feedback paradigm can shed light upon the hedonic behavior of simple organisms that emerged on the evolutionary stage long before nerve nets or brains, allowing questions of primitive sentience to be separated from the complex neural processes that are correlated with human consciousness. In fact, it is only within this broadened, less neurocentric depiction that the many facets of the entire emotional sensory system can come to light.

Indeed, this new view allows us to zoom in, conceptually revisiting the earliest emergent sensory mechanisms for detailed clarity in the form and function of self-regulatory feedback. At this micro level, the feedback (and feed-forward) circuitry offers conceptual precision to descriptive terms for information flow in space and time (ie, inside, outside, before, after, backward, forward, bottom-up, top-down), precision that can help physicians and social scientists transcend the Cartesian (“dual process”) mind-body muddle. This new approach allows us to zoom out to the macro level of analysis, offering a bird's eye vantage from which a complete spectrum of informative emotional feeling tones comes into view, a continuum of meaningful sensory signals ranging from the hardwired and universal, to the learned, socio-cultural and particular, finely tuned to the specific life experience of each unique individual.

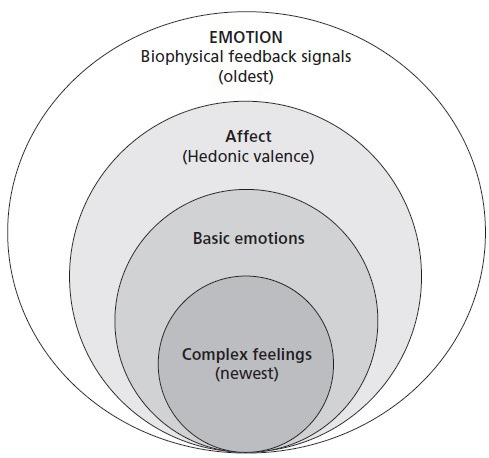

In fact, since its initial emergence, the emotional sense has undergone tremendous elaboration by natural selection. Its present structure is an elegant tri-level informational hierarchy—from affect to basic to complex feelings—reflecting the generally “triune” structure of the brain,108 yet with each still playing its own uniquely valuable self-regulatory role. But perhaps most importantly, it shows how affect provides the core “hedonic”109 evaluative message, the fundamental “bad-for-me” or “good-for-me” appraisals that we experience as immediate psychological pain or pleasure. Indeed, identifying emotion as our primal self-regulatory sense, restores our innate tether to biologically determined optimal—perhaps non-negotiable—states of life-giving balance.

In sum, the emotional sense is born of biophysical regulatory feedback signals that come courtesy of lawful stimulus-response behavior, signals that still undergird our hedonic emotional perceptions and their coupled approach or avoid behavioral responses. These affective polar opposites are the highly conserved felt evaluations—saying “no” to this and “yes” to that—those that appear across the various levels of analysis, recognizable in affective “eustress and distress” signals50; informing us of the immediate environmental “benefits and harms,”46 or symbolic “challenges and threats,”110 and giving rise to our general positive and negative categories of emotion. I will, in a moment, suggest an even more fundamental self-regulatory dichotomy that undergirds them all, one showing how the amazing emotional sense offers universal self-regulatory perceptions for all humans which—when properly understood—also offer a personally tailored guidance system to each individual. For now, “emotion” is defined to include these core hedonic self-regulatory signals as well as the primary or basic emotions111 (joy, sadness, disgust, anger and fear); and the complex112 feelings (also known as “unnatural” 113; “secondary” 114; “social” or “moral” emotions.115,116 This complex class, the most recent to have emerged on the evolutionary stage, is the most cognitively laden and temporally expansive, and includes such familiar feelings as trust, mistrust, pride, shame, gratitude, contempt, envy, admiration, love, and hate. Indeed, as depicted in the Venn diagram of Figure 2, this expanded, all-inclusive, multitiered, definition of the emotional system also reflects the stair-step evolution of each new level of self-regulatory information as it emerged over our sweeping biological history—the most ancient remaining functionally foundational and present within each, more recent, additional enhancement.

Figure 2.

The expanded categorical definition of emotion.

Whether or not the above discussion coheres for health professionals or social scientists who may not stray far from our respective disciplines, please bear with me, for the self-regulatory logic that emerges from the ubiquitous biophysical feedback process speaks for itself. Indeed, once this missing piece of the emotional puzzle—its self-regulatory sensory function—is identified, many other disjointed bodies of empirical evidence fall into place.

BEHAVIOR, FEEDBACK, AND THE EMERGENCE OF SELF-REGULATORY CODE

In this new view, such ubiquitous bottom-up phenomena as embodied cognitions, priming effects, subconscious attitudes, unconscious motives, conditioned memories, and instinctive autopilot behaviors are a direct result of the self-regulatory processes we perceive via the emotional sense. In fact, it is only in the context of these primary bottom-up aspects of emotion that the more recently evolved top-down add-ons begin to make self-regulatory sense.

It is conceivable, however, that I am indulging in naive realism or am equally guilty of anthropomorphism—pushing the human experience of pleasure and pain back upon less complex species. To avert this critique, I'd like to temporarily decouple the stimulus-response relationship, asking readers to simply bracket the subjective aspects of emotion (depicted in Figure 2) and maintain a strictly behaviorist perspective. In fact, while the sensory information has undergone tremendous elaboration over time, the basic motor approach/ avoid behavioral responses remain the same—and they embody the self-regulatory logos on offer. Thus, in the spirit of empiricism, we will confine the next portion of the discussion to the objective approach or avoid behavioral pattern and let the actions speak for themselves.

To continue, as previously suggested, the secret to cracking the self-regulatory code is feedback. This is because feedback is first and foremost a regulatory control process—in-forming while trans-forming, ordering, and organizing behavior. In fact, “integral feedback control” is a basic engineering strategy in complex man-made systems such as a jet airplane, with feedback loops found at every level, from transistors and circuits to instruments and actuators, to the autopilot mechanism for the entire vehicle itself.117

Although Ashby's homeostat was largely forgotten, this autopilot nature of behavioral control is perhaps what later inspired engineering psychologists to link human behavior with negative or “regulatory” feedback control. Regulatory feedback is associated with homeostasis—keeping things at their proper set points in order to keep the airplane or the creature shipshape and on its proper course. Indeed, by the 1970's, on the heels of the behaviorist heyday, feedback control theory a “quantitative science of purposive systems”118 was resurrected with the palliative promise of restoring internal goal states to psychological theory. In organic systems, however, we've seen that homeostatic goal states rely upon natural physical constants, reaction thresholds, and optimal equilibrium balance points—chemically or energetically “favorable” states, in accordance with the laws of thermodynamics. This may be why the classic example of homeostatic feedback control then became the thermostat.119 The thermostatic regulator functions through a three step process: It compares the actual state of the system to some preset optimum, signals when a mismatch is detected, and self-corrects back toward the optimal state (it “effects”89 an observable behavioral response). In a home heater, for example, the actual room temperature is compared to the desired preset temperature, and when the house gets too hot or too cold, the thermostat rebalances the system by kicking the heat on or off. While problematic (outside its original quantitative context), this thermostatic model offers an excellent inroad into our detailed examination of the simplest sensory systems, as the three steps (comparison, signaling, and self-correction) are crucial components of the self-regulatory feedback cycle. For key to our discussion, is that feedback comes in two types. In fact, the binary code—as well as the thermostatic arrangement itself—emerges from an elegant coupling of these two types of feedback, a stimulus response relationship that creates the necessary bridge between the determined (happening) behavior of matter and the partially free—but logically self-regulatory—(doing) behavior of animate agents. This coupling also delivers the functions that the early cyberneticists had hoped could: “at last explain how ‘mental’ causes could enter into ‘physical’ effects.”118 Indeed, the coupling of both types of feedback is the missing piece required to illuminate the self-regulatory logos, and vault the gulf to human behavior with that logic intact.

Positive and Negative Feedback

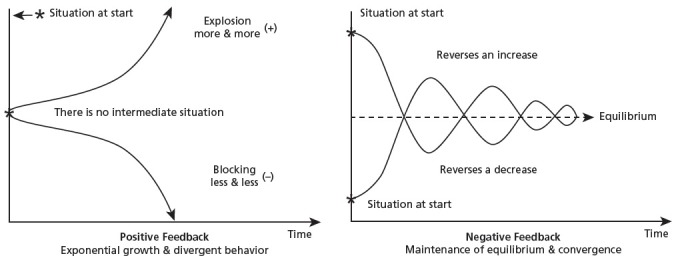

The first type of feedback is called positive feedback. In a positive feedback loop the iterative cycles build upon one another, such that with each new cycle the change to the system proceeds in the same direction as that of the former cycle (Figure 3.) Positive feedback is associated with chaotic change, leading to divergent behavior, “an indefinite expansion or explosion (a running away toward infinity) or total blocking of activities (a running away toward zero).”86 Functionally, positive feedback is amplifying, associated with rapid, exponential, growth (or decay) and upward or downward spirals of runaway change. Examples include: chain reactions, autocatalysis, signal transduction cascades, economic inflation or deflation, and population explosion or depletion. Please note that there is no evaluative (good or bad) connotation to “positive,” the term speaking only of the direction of change, with positive connoting qualitative change in the same direction as the previous cycle, whether that direction yields a quantitative increase or a decrease in a given energetic or chemical parameter.

Figure 3.

The two types of feedback. (Adapted from de Rosnay, 1979.)

The second type, negative feedback does just the opposite, reversing the direction of the process relative to the previous iteration (Figure 3). Once again, there is no evaluative judgment, ‘negative’ simply means reversing the direction of the change, regardless of the nature of that change. But since it is a ubiquitous feature of homeostatic circuits, negative feedback is considered regulatory, in that it controls the runaway “chaotic” change born of positive feedback loops. As mentioned, negative feedback relies upon natural laws and statistical mechanics, kicking in when upper or lower thresholds of a given parameter are breached, providing convergence to a preferred, chemically or energetically “favorable” state, in accordance with the laws of thermodynamics and quantum mechanics. (Indeed, even the electron has a preferred energetic “ground” state.) But it is equally important to realize that the wild, runaway behavior of positive feedback also flows from those same physical laws and forces—an electron, an ion, a polarized molecule, a membrane, a neuron, or an organism—can also be in an “excited” or temporarily unbalanced dynamic state. It seems that life could neither emerge nor be sustained without both halves of the in-formative trans-formative whole that is feedback.

In short, both positive and negative feedback are ubiquitous in nature, counterparts to one another, working together in the process of self-organization. While positive feedback yields the instability and divergent processes that constantly create, destroy, and recreate new arrangements of matter, negative feedback provides the stabilizing balance, homeostasis, and preservation of form. Indeed, feedback loops are among nature's most fundamental building blocks, “the engine of selforganizing dynamical activity” that “leaves its tracks and marks as fractal structures”120—the non-Euclidian “fractal”121 geometric shapes underlying all natural and biological structures, including the human brain.

Coupled Feedback Loops and Self-regulation in Early Life

Historically, however, most control models of human behavior relied upon only negative feedback, and have therefore languished. Likewise, it has since become clear that even the simplest behavioral control mechanism in a living system involves many links and chains of single positive or negative loops, which changes the entire game. Indeed, when we begin melding the physically deterministic and the subjective functional definitions of “self,” the increases and decreases manifested by positive and negative feedback (the changes and their reversals) connote state changes within the identity of a living form, changes driven directly by the reciprocally disturbing interactions between the selfsystem and its immediate (not-self) environment. In evolutionary terms, such a regulatory process would have emerged along with life itself, an outgrowth of “hypercycles” and “autocatalytic” chemical networks,122 constituting a “thermodynamic work cycle,”123 the first sort of metabolism. A further requirement for life was the formation of the lipid membrane to bound, contain, and protect a living system (analogous to human skin), yet with structures that allow it to sense and respond to its environment, both of which were essential to the emergence of minimal biological agency124—goal seeking behavior. (Also see Sherman and Deacon, for an intriguing theory of a missing link “autocell”125 that bridges thermodynamics, morphodynamics, and goal-seeking teleodynamics in emergent systems; albeit devoid of the feedback processes discussed here.) In fact, such a system has been suggested to predate even natural selection, described as “context dependent actualization of potential,”126 or “self-other organization.”127

At some serendipitous juncture in our evolutionary history however, self-replicating molecular arrangements emerged and natural selection was off and running. But, regardless of how this leap occurred, central to our discussion is that regulatory feedback circuits and their dynamic logic128 were already in place, serving regulatory functions in the first single celled creatures. “Regulation” in this context involves changes (“covalent modifications”) in the properties of a cell under the influence of external and internal signals in order to adjust the cell's internal biochemistry. This process is considered the evolutionary “origin” of sensory processing129—and, I argue, is precisely what the cyberneticists were intuiting about feedback control. Indeed, in whatever order they emerged, the trifecta abilities: (1) to sense the physical qualities of one's immediate environment; (2) to respond behaviorally, and (3) to categorize sensory stimulus gives an “operational closure,”130 a circular causality131—a general principle of organization within an autopoietic system that defines biological “function” itself.132

Feedback Functions of Cellular Receptor Complexes

Nonetheless, while the bulk of this discussion focuses upon the functional outcomes of feedback processes, understanding the structures that instantiate them is paramount—for biological function follows physical form. These structures are called protein receptor complexes, essential components of all cellular membranes in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Cellular receptors were originally conceived as lock and key stimulus-response facilitators, upon which a chemical agent (ligand) would bind, triggering a specific cellular response. In fact, these unique cell-surface molecules are not only essential to the earliest sensory systems, but remain central to intercellular signaling, interacting with hormones and humoral factors essential to inter-organ communication.133 However, with powerful new microscopes it has become clear that the simple lock and key model was severely limited, and cellular receptors have proven to be far more structurally and functionally complex (now referred to as “complexes”). Indeed, through their form they instantiate both the positive and the negative feedback loops under discussion and serve as structural homologues to Ashby's homeostat. For crucially, these structures are transmembrane receptor complexes, physically exposed to both the external and internal environments of a cell. They have both ‘heads’ outside and ‘tails’ inside—a general structural feature that facilitates the feedback comparison and the internal effector response.

Moreover, the individual proteins that comprise the complexes are detailed 3-D structures with modular construction and moving parts—shape-shifting dynamics driven by ligand binding that allow for complex couplings, combinations, and chains of individually positive or negative feedback loops. In fact, at present, the repertoire of genes that encode these plasma membrane receptors has been called the “signaling receptome” with receptor families that reflect their evolutionary origins and chart their ever-increasing functional complexity. Indeed, the Seven-Transmembrane (7TM) family of receptors (still present in the human receptome), first emerged in unicellular organisms already composed of seven discrete transmembrane domains that induce conformational changes and diverse functions.133 As such, receptor complexes at every level on the phylogenetic tree instantiate intricate webworks of coupled feedback loops and circuits with common functional motifs.134,135 These motifs include such functions as: basal homeostat, threshold limiter, and adaption (born of negative loops); and amplifier, accelerator, damper, delayer, or bistable switching (of positive loops); or pulse generators or oscillators (of both).

Of particular interest for our new model of emotion, is the positive feedback motif of bistable, digital switches between alternative phases or states135–139 the aforementioned covalent modifications.129 As previously noted, such deterministic binary (either/or) switching is observable at all scales of material organization (ie, chiral symmetry of amino acids that determine the genetic code; bonding and anti-bonding reactions that govern protein folding; “on/off” switching of genes and all-or-none firings of neurons.) In fact, this dynamic bistable pattern emerges consistently even from randomly connected network nodes yielding systems poised critically on the “edge-of-chaos,” dynamically balanced between stability and change.96 More, the dynamic transitions between these bistable states that have been suggested to provide the earliest forms of computation in nature.140 Indeed, even the simple thermostat requires bistable switching—and several other positive feedback motifs, as did Ashby's original homeostat.

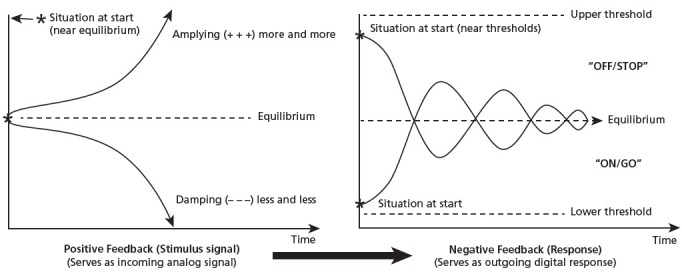

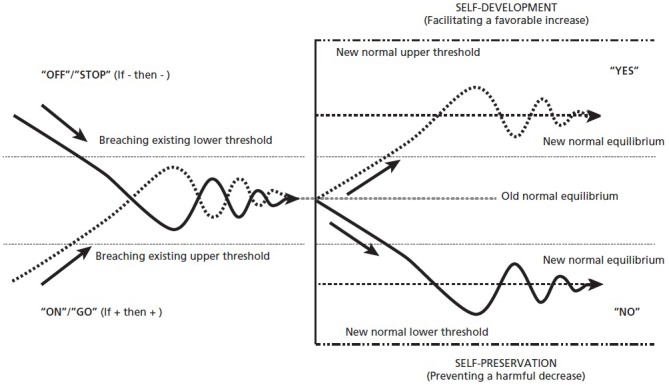

Hence, the present proposal is that the original winning evolutionary scenario—the one that underpins the self-regulatory behavior of life forms—was a coupling of both types of feedback such that the divergent positive feedback stimulus triggers convergent, negative feedback regulatory responses (Figure 4). This general arrangement delivers most (if not all) of the functional feedback motifs in one fell swoop, providing nearly every requirement of the regulatory thermostat.

Figure 4.

How coupled positive and negative feedback yields stimulus-response behavior. (Adapted from de Rosnay, 1979.)

For example, as depicted at left in Figure 4, the amplification versus damping, and bistable switching motifs of positive feedback offer a graded analog signal which indicates the system is changing in significant ways, that some relevant environmental stimulus is either increasing or decreasing. (Others have termed this the “sense signal” which is then compared to an inner “reference signal,” triggering the “error signal.”89) These changes are then indeed compared to the desired states and reaction thresholds (basal homeostatic and limiter motifs of negative feedback, shown at right); which triggers a corrective response that reverses the trend, bringing the system back into balance (like the home furnace). While perhaps neglected in cybernetic models of human behavior, this coupled feedback configuration has been noted elsewhere and deemed a biological logic gate or block that can switch from the “and” to the “or” functions,141 the logic circuitry of the electrical transistors in computer chips.

With an elegant simplicity, this general feedback arrangement offers both analog and digital information processing, extending its principle of circular closure across multiple levels of organization, to forge a selfsimilar pattern of relational causality across multiple scales in time and space—fulfilling all Ashby's original hopes for his homeostatic thinking brain. Indeed, like a neural network, it gives rise to horizontal cross talk (bidirectional and parallel processing) between local network nodes as well as unidirectional signaling and control relationships across vertical levels in fractal hierarchies, fostering synchrony between faster and slower system dynamics, and bridging local and global levels of coherence and control. Most importantly, these reciprocal self-regulatory relationships coordinate life-giving functions in complex organisms, guiding intercellular development142 and ultimately yielding “perfect adaptation.”143 In fact, the motifs of coupled positive and negative feedback loops include the oscillatory behavior, pulse generators, and on/off firing behavior of neural networks, and the “tunability” of biological rhythms from cell cycles to heartbeats.144,145 Furthermore, at the macro, systemic, level of analysis, wherein the organism as a whole interacts directly within its external ecological niche, this adaptive tunability constitutes a “constrained form of computational learning”—synonymous with evolution itself,146 Ashby's learning machine writ large with its simple machine-like algorithms becoming ever more flexibly personalized “ecorithms”147 guiding evermore complex adaptive responses. Best of all, of course, this elegant feedback coupling sets the stage for the first sorts of hedonic behavior—as well as the first sort of enacted, embodied, mind.

Self-regulatory Behavior in Bacteria and the Tit-for-tat Code

Indeed, this new story strikes at the heart of an ongoing philosophical debate as to the nature and origins of mind. Perhaps related to the original Cartesian divide, the debate concerns whether mindful “cognition” is an exclusive manifestation of a functional brain or whether it is primarily embodied and embedded in an environmental context (ie, references 148-150).148–150 The emotional sensory model suggests that it is both, but that as the locus of the feedback control function, “branes”—environmentally embedded cellular membranes—came before brains in terms of evolution, and their signaling dynamics delivered the first experience of self in space and time. (In other words, it suggests that emotion preceded “cognition” proper and that “sentio ergo sum”—I feel therefore I am—may have been more biophysically accurate.) As such, the sensory feedback model weds the computational, representational, identity and embodiment approaches to the emergence of mind in the singular concept of primary selfregulatory perception. That, which I am arguing, gave rise to the inaugural evaluations within the emotional sense.

In fact, the brilliance of the cybernetic model, was that rather than to control behavior per se, it served to “control perception.”89 It was a theory of how a system controls its somatosensory experience of being—its hedonic feeling of what is happening.46 But this seems just a convoluted way of saying that a regulatory control system delivers (ushers or creates) perception itself. In short, it yields a crude mind. Indeed, Jaak Panksepp, founding father of “affective neuroscience”151 posits a core affective consciousness, or a “visceral nervous system” that yields “primordial affective mentality”—genuine feelings in all neurally endowed creatures, “similar to seeing a color.” Theorists stop short, however, of declaring emotion to be an actual sense, for as emotion pioneer Nico Frijda puts it: “There is still no detailed hypothesis at the functional level of how innate affective stimuli evoke affect.”9 This is where an examination of the simplest sensory systems can clarify and expose the devilish molecular details within which the primal emotional sense remains shrouded.

Take, for example, the chemosensory system of the Escherichia coli (E coli) bacterium, perhaps the first identifiable sense to emerge, and one whose molecular circuitry is quite well understood. The on/off switching that underlies affect is readily evident in the digital behaviors of coupled protein molecules, those central to genetic regulation as well as sensory perception. (For reviews, see references 129, 152, 153.) As mentioned, the structure of interest is the protein receptor complex on its “brane”—transmembrane structures analogous in humans to external sense organs on our body and skin (noses, ear, eyes, etc.), yet where all the feedback functionality is orchestrated.

Indeed, in the simple E coli, there are three levels of binary self-regulatory switching with functional outcomes from on/off genetic regulation, through stop/go behavior (approach/avoid chemotaxis), to the yes/no hedonic evaluative representations under discussion, and as the details will demonstrate, each ofwhich exemplifies the self-regulatory feedback arrangement depicted in Figure 4. In fact, though far more complex than our ancient ancestral autocell, the molecular circuitry on the brane of the E coli illustrates evolutionary enhancements of the original capacity to categorize sensory stimulus, an original requirement for causal, operational, and functional closure. Furthermore, in terms of the brain-only view, these three levels offer exact matches to the three criteria required of a legitimate “internal representation” offered by Haugland154: (1) to coordinate its behaviors with environmental features not always “reliably present to the system”; (2) to cope with such cases by having “something else” stand in (in place of a direct environmental signal) and guide behavior in its stead; and (3) that “something else” is part of a more general representational scheme—a code—that allows the standing in to occur systematically and allows for a variety of related representational states.155 Likewise, these conditions dovetail cleanly onto Powers' control model of human behavior,89 with the comparison between Haugland's conditions 1 and 2 (termed the sense signal and the reference signal),154 which when discrepant delivers the error signal, with a coupled self-correcting effector behavioral response that I am suggesting manifests as the binary hedonic valence of emotion. In short, the coupling of positive and negative feedback gives rise to all three criteria for a functional mind and an elegant sensorimotor behavioral control system—far before brains emerged on the evolutionary stage.

While some may rightly worry that an E coli bacterium is hardly analogous to a human being, its simple sensory system provides an elegantly detailed example of the “thermostatic” feedback arrangement in action, allowing us to precisely parse what happens where and when in space and time that yields self-regulated hedonic behavior. In other words, in terms of both function and structure, the E coli bacterium offers an excellent biological stand-in for the “system” depicted in Figure 1, its membrane physically bounding itself from its not-self environment. The feedback loop is the embedded aspect of mind, the transmembrane sensory receptors reporting self-relevant stimulus as the body moves about, with the three steps of feedback control constituting what goes on in the “black box” mind proper—a simple loop that yields primal hedonic perception and approach/ avoid behavior. Indeed, the suggestion is that this simple circuitry reflects the core “molecular universals” of approach and avoidant behaviors conserved in a wide range of species.156 It is also likely the source of the generally accepted taxonomy of “primary process affects” in emotion theory: sensory affects, bodily homeostatic affects, and brain emotional affects151—those that loosely capture the three tiers of information encoded in human emotional perceptions (previously depicted in Figure 2).

With that said, the general mechanism works like this: A chemical in the external environment binds to a receptor protein complex on the bug's outer membrane, activating a signal transduction cascade inside the cell that leads to both a short term change in the organism's behavior, and a long-term adaptation of the receptor mechanism itself.157 Each of these changes is driven by the feedback arrangement (depicted in Figure 4), and via their coupling to one another, they typify the circular causality wherein the faster dynamics serve as the bottom-up signals triggering the slower, top-down corrective response. In short, the system utilizes three levels of the thermostatic stimulus-response switching, each facilitated by the feedback coupling.

Specifically, in E coli, the short-term behavioral response is the switching between a counterclockwise (CCW) or clockwise (CW) rotation of a given flagellum—one of the four to eight tail-like protein appendages embedded in the cell wall—that allows swimming toward or away from beneficial or harmful chemical gradients, temperature changes, or other relevant environmental conditions. (With the CCW motion, all the flagella rope together propelling the organism forward, but a switch in any one flagellum to the CW mode, flails them apart causing an abrupt halt and a “tumble” off in another direction.)

From On/Off to Stop/Go

This basic stop and go behavior is accomplished by a circuit of many positive and negative loops mediating interactions between five receptor proteins (ie, Trg, sensing ribose and galactose; Tar sensing aspartate; Tsr, serine; Tap, peptides; and Aer, which senses O2) and the protein products of six key genes (CheW, CheA, CheY, CheZ, CheR, CheB). These receptor proteins (numbering in the tens of thousands) cooperatively cluster together in the cellular membrane by a process of stochastic self-assembly,158–160 such that they serve as an “information processing organelle,”161 likened to a “nose.”162 As mentioned, however, what is instructive about the brane, is that this nose-like sensory organ spans the depth of the membrane “skin” such that its outside heads and inside tails are privy to both internal and external environments simultaneously, which is how the feedback comparisons, signaling and responses are instantiated.

These transmembrane receptor complexes (assisted by adaptor protein CheW and histodine kinase CheA) detect the change in chemical gradients—the environmental stimulus—and regulate behavior accordingly via integral feedback control.117 As in Figure 4, they constantly monitor the environment, comparing the relative concentrations at time one with those at time two (your classic negative feedback homeostat motif), with the increase or decrease in bound receptors serving as a positive feedback signal informing the cell that a significant deviation from stable set-points (negative feedback limiter) has occurred. (As the core sensory organ, the outside “heads” of the receptor complexes deliver Powers' “sense signals,” 89 and subsequent alterations of the inside “tails” serve as Haugeland's first criteria for an internal representation—the direct detectors of relevant environmental stimulus that may not always be present.154

For from there, a coupled positive feedback exchange between CheA and phophatase CheZ takes place inside the cell, which adds or removes phosphorous (respectively) to and from second messenger CheY, which directly initiates the regulatory (negative feedback) motor response, the switching between CCW and CW flagellum rotational modes that controls the bugs behavior. (This second messenger protein, serves as Haugeland's second criteria for mindful representation, the “something else”154 that stands in for the missing stimulus, yet still mediates the stop and go behavior. In the Powers model, this is an internal extension of the sense signal 89 (and perhaps the simplest example of the evermore complex signal transduction cascades observable in more complex organisms, those that include neurotransmitters and hormones in humans.)

From Stop/Go to Yes/No

So far, however, this is only half of the story. For these are the bottom-up fast time, activating, dynamics, wherein the binding and unbinding of receptor proteins triggers the on/off phosphorylation or dephosphorylation of CheY, which then drives the immediate stop/go switching between behavioral regimes. These are the dynamics (the feedback coupling depicted in Figure 4) that operate on timescales of milliseconds, with the amplifying (+) signal triggering a (−) reversal switching to the “OFF” (or, in this case, “Stop”) mode. Likewise, a decrease (−) in the phosphorylation signal triggers an increase (+), wherein the reversing (negative feedback) response switches to the “ON” (or “Go”) mode (See Figure 4). Do note that these dynamics are regulatory (negative feedback) responses; they are keeping the system within the specific thresholds, preserving the system within its existing parameters. (This is the level where the, homeostatic negative-feedback-only control models still ring true.)

The other half of this regulatory circuit follows the same feedback pattern, but unfolds over a longer timescale (minutes), yielding the slower, top-down, deactivating dynamic that gives rise to adaptation in the bug's sensory system—a brief, but functional, “memory.”129,161 This is a change that increases the range of sensitivity by altering the sensory mechanism itself, offering the bacterium a broadened bandwidth of information for subsequent encounters, adding a feed-forward step in the cycle.163

This is a crucial juncture in our new story. For it is this adaptive response that takes the logic of on/off switching and stop/go behavior to the yes/noevaluation that ultimately underlies the proximate feel good/feel bad hedonic valence of emotion. (In fact, this feed-forward step is a necessary piece for any control model that posits anticipatory or purposeful goal states.)

To continue, this slower top-down adaptation process informs the system of the rate of change in the original stimulus, and results in an alteration of the sensory receptor complex itself This occurs through methylation of specific units of the receptor complex—the inside “tails”—by a reciprocal on-off relationship between the remaining two proteins: CheR (a methyl transferase that adds a methyl group) to the tail and CheB (a methyl esterase that removes it). This pattern is virtually identical to and directly linked with the faster phosphorylation switching for stop/go behavior (as depicted in Figure 4) and thus provides a record of the specific responses to environmental changes. (Indeed, as phosphorylation of Ch A increases, the methylation activity of CheB correspondingly decreases.)

However, unlike the faster dynamics, this adaptive homeostatic (negative feedback) response occurs after existing sensory thresholds have been breached (or saturation has occurred), settling the system into a new normal rather than simply returning to the original set point. Hence, this modulation-by-methylation allows the system to reset its equilibrium to zero, even while the chemoeffectors are still present, but at a new higher or lower equilibrium point—altering receptor sensitivity and adding overall complexity to the system. (This threshold shift can be envisioned by imagining the starting point on Figure 4 to have begun either above or below the existing threshold, rather than within as depicted, where the “On” or “Off” response settles the system into a relatively upward or downward new normal; and will also be depicted in Figure 7.) In terms of function, as one molecular biologist put it, this allows the bug to tune the “volume” of its sensory system up or down164; or as Powers put it, how the feedback process “controls perception.”118

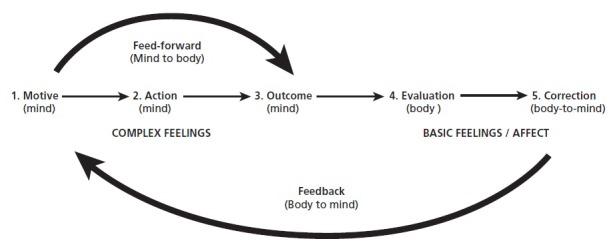

Figure 7.

How the Tit-for-tat code serves dual self-regulatory "purposes": self-development and self-preservation.

In sum, the reciprocal feedback relationship between the phosphorylation and the methylation signaling pathways yields the causal circular connectivity between multiple levels of organization, with its temporal pattern of fast activation and slow deactivation delivering the best “noise attenuation,”165 bringing us full circle to the vertical tunability that synchronizes cells in multi-cellular organisms. Indeed, this methylation-adaptation process is the key “stimulus-response” relationship in our new story, as its corrective action kicks in with threshold-breaching, globally significant stimulus—whenever novel, intense, and deeply “self-relevant” changes are underway.

The Tit-for-tat Self-regulatory Code

Best of all, it comes freighted with its own evaluative logic. The positive feedback increases or decreases in methylation of the protein receptor complex (the chemical marks on the inside tails) offer an exact reflection of the stop and go behavior and its direct correlation with the harmful or beneficial environmental conditions. They provide a faithful signal of how previous behavior said “yes” to certain environmental conditions and “no” to others. (They provide Haugeland's third criteria for a mindful internal representation, a more general representational scheme—a code that can reflect a variety of related stimuli.154

Indeed, the upward going (positive, +) stimulus represents “goodies” that promote metabolic flow and developmental growth, while the downward (negative, −) decreases, signal “baddies” that could threaten structural stability. Together they offer the bacterium a single—yet binary—evaluative symbol, one that represents everything of life-giving importance from the presence of food and toxins, to temperature shifts, changes in oxygen levels or ph balance,167,168 to the constant energy flux and flows of electromagnetic fields on nanoscales in space and time169—which inform the digital approach/avoid behaviors of chemotaxis, thermotaxis, aerotaxis, osmotaxis, and phototaxis, respectively.161 In fact, given its origins in electromagnetic forces and thermodynamic laws, it offers a general searching and learning strategy dubbed “infotaxis” for balancing the needs to explore and exploit the immediate environment, a way of zeroing in on information that “accumulates as entropy decreases,”170 not unlike a child's game of Hot Beans (“you are getting warmer, you are getting colder”). In short, the functional effect of this chemical network is that a formerly neutral on/off switch can be bootstrapped into holding general good/bad—“for me”—evaluative significance.

Although these elegant feedback control networks are based on simple diffusion and stochastic (statistically random) chemical fluctuations, they set the evolutionary stage for genuine self-regulatory sentience to emerge. Indeed, tremendous selective pressure would be placed upon any mutation allowing the organism to distinguish between these two binary stimuli and respond in ways that help them along. In fact, such ability is required in any control model of behavior, as it would constitute both the comparison process and perception of the error signal itself.

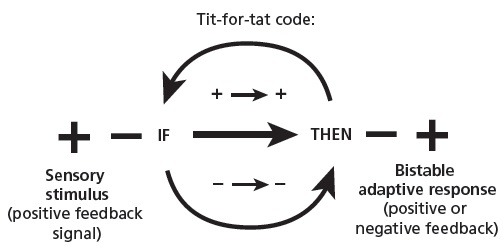

Herein lies the logic of what I call the tit-for-tat self regulatory code within the hedonic valence of emotion. All that was required at this historical juncture was an additional positive feedback loop, one that could offer a further feed-forward enhancement of the existing signaling pathway, one that allowed a choice-making switch between the yes/no options, before the negative feedback rebalancing had occurred. In fact, this is the missing link required to bridge the gulf to self-regulatory (goal seeking) behavior in humans, as well as the conceptual heart of genuine “cognitive” perception.

Indeed, a feed-forward control process can act in anticipation of stimulus conditions,171 drawing upon the on-line memory embodied in the ebb and flow of sensory adaptation. This flexible choice-making response would indeed facilitate the optimal sorts of changes that have happened in the past, and could readily be accomplished by a binary switch between the positive or negative feedback responses themselves. Centrally, this new story suggests that something like this must have occurred, giving rise to the binary computational algorithm inherent within the feedback comparator: a straightforward if-then logical rule within the self-regulatory sense. Elegant in its simplicity, the rule states: If positive (+) then positive (+), if negative (−) then negative (−). In other words, for a positive stimulus signal (more and more), perform a positive feedback (more and more amplifying) response. For a negative stimulus signal (less and less), perform a negative, stabilizing response that reverses the present trend (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The Tit-For-tat self-regulatory code.

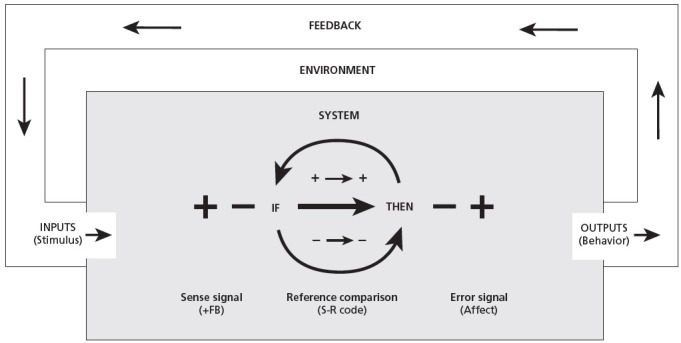

Following this simple tit-for-tat self-regulatory perceptual logic allows the organism to approach, facilitate, and otherwise increase the in-forming conditions that are life-promoting, and to avoid, prevent or otherwise decrease harmful, entropic changes. Likewise, with the automatic nature of the adaptive process, this simple code provides the classical semantic symbols, the innately reinforcing—rewarding or punishing—“unconditioned” Pavlovian responses that undergird both classical and operant conditioned learning. Indeed, the fundamental hedonic perception provides the elusive “basement language” that philosophers have long sought, reliable knowledge about the external world rooted in primal sensory experience.172 In short, the self-regulatory code unites the stimulus-response phenomena noted within the behaviorist tradition with the cybernetic control models of human behavior. As depicted in Figure 6, the self-regulatory code elucidates the inner workings of the black box (what goes on between the input stimulus and output response); clarifying the relationship between Powers' “sense,” “reference” and “error” signals89; and bridging cleanly to Carver and Scheier's origins of affect.38,39 (Offering, however, the more intuitive self-relevant logic of hedonism, wherein negative feedback is associated with pain and avoidant behavior rather than with pleasure and approach.)

Figure 6.

The Self-regulatory code in the black control box.

In our little E coli, however, it matters not whether any subjective experience of the positive feedback signal is present, for the negative feedback response—the automatic adaptation—has already had an important self-regulatory effect.129 The adaptation has shifted the system to a higher or a lower equilibrium point (the new normal), rather than returning it to the formerly favorable state, and in perfect accordance with the harmful or beneficial environmental stimulus. In doing so, it has accomplished either an optimizing, developmental, adaptation—saying “yes” to beneficial changes—or a self-preservationary intervention, saying “no” to potentially self-destructive harms.

Depicted, for example, in Figure 7, is essentially the “on/off” response process shown previously (in Figure 4), and in Figure 7 is that same response but one following a breach ofeither threshold yielding the “yes/no” evaluation. (Herein lies the roots of the hedonic treadmill,173 wherein sensory adaptations to good stuff become internalized such that new levels of stimulus are required to trigger positive self-relevance.) But regardless of any possible perceptual accouterments, in even the very earliest forms of life, these simple chemical regulatory feedback networks have cracked the philosophical door between determinism and compatible free will, between hardwired logos and softwired telos, ushering behavioral agency with a few degrees of freedom—allowing the organism an active role in the evolutionary process.

Individual and Social Aspects of Self

In fact, and perhaps even more philosophically intriguing, this simple self-regulatory system also sets the stage to define individual and social aspects of the selfsystem. While the cellular membrane initially demarks self from the not-self environment, this simple yes/no rule can also be pressed into service to identify genetically similar and different bacterial species, in perhaps the earliest forms of cooperative communalism and competitive tribalism. For example, the phenomenon of “quorum sensing” where on/off switching between behavioral modes depends upon the concentration of other citizens within a specific bacterial species.174

Indeed, in addition to pre-existing environmental stimuli, quorum sensing bacteria produce and release self-identifying autoinducers, chemical signal molecules that then rise and fall with the local cell-population density. They are used for communication, allowing individuals to synchronize particular behaviors so they can function as multicellular organisms, marshalling cooperative chemical defenses—or virulent attacks—against other species.175 Likewise, these either/or (me or we, us or them) signals, can be coupled to other sensory stimuli like heat or cold to guide more complex autonomous or communal behavior. For example, an individual E. coli bacterium will normally thermotax toward warm environments where growth conditions are optimal. But should the population become overly dense and therefore resources strained, loner—self-preservationary—mode will kick in and the bug will move toward cooler locations 166 to “chill out” until conditions for growth improve.164 Likewise, is this dual sense of selfidentity in the elegant slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum, that can exist either as a single-celled organism or as a colony of social amoebas—a eukaryote with the same cAMP-sensing toolkit as humans, rooted in two varieties of the ancient 7TM receptor.133

A central insight from this level of analysis is that a core, physical, sense of identity (both personal and social) is already apparent in the lowly bacterium, founded upon simple protein networks and their integral feedback dynamics. Hence, this first form of self-regulatory sentience also cracks the philosophical door to phenomenal being (and becoming) in time and space as well as doing behavior.

Nonetheless, first and foremost, the present proposal is that these ancient self-regulatory mechanisms have been honed by natural selection to yield the chemical—hard-wired (genetic)—distinction between self and not-self utilized by the immune system, as well as the chemical language of the paracrine and endocrine systems,176 and to subserve the neuropeptides involved in neural communication in both enteric177 and central nervous systems—those deemed the “molecules of emotion.”178 In fact, they provide the informational “language”179 that allows optimal cellular differentiation and space/time migration of the right types of cells to the right places at the right times throughout embryonic development. But in addition to this physiological legacy, in humans, the ongoing development and empathic expansion of one's mindful, social, and cultural sense of identity180 is also crucial to an optimal developmental trajectory, and key to decoding the universal guidance offered by our emotional sensory perceptions.

Purpose in Evolution?

This brings us to the fundamentally significant binary dichotomy gestured toward previously, that which lies at the most primordial core of nature's value system. This is the prime self-regulatory directive that has been conserved, kept intact throughout our evolutionary history; the one that allows organisms to actively participate in natural selection; and the one that provides the evaluative meaning within the hedonic valance of emotion. As already depicted in Figure 7, the yes/no binary evaluations mediate dual teleological goal states—purposes, if you will: Those of self-development, the core evaluative appraisal for categorically pleasurable “positive” emotions, and selfpreservation, for the painful or “negative” category. These are the binary functional outcomes of the ancient self-regulatory process, those that make hedonic behavior “optimal” or “right” in the deepest, most biologically valid, sense of the word (moral implications notwithstanding).

Although potentially oppositional purposes, it is crucial to note that these are two right and good, perhaps non-negotiable requirements for life itself inherent within the most primordial regulatory processes. Each is equally appropriate at different times and spaces, and optimal under different environmental circumstances. These are the underlying goals states, the teleological purposes, glimpsed by the early cyberneticists; later described by pioneering systems psychologists as preparatory (preserving the original set point) and participatory adaptation to the new,181 and are now described as the dual regulatory “focuses” within complex human self-regulation.60 These binary purposes are also what complexity scientist's might call selforganizing “attractors” on “fitness landscapes,”182 those that keep creatures poised between chaotic change and rigid stability; and those that are reflected in the digital “growth or protection” programs of cells.183,184 Best of all, these dual purposes provide a direct biophysical tether between subjectively good and bad perceptions and objectively right and wrong states of living-giving balance.

This is how acknowledging bottom-up self-regulatory sensory feedback can fill a sizable gap in evolutionary theory—for these dual purposes are simply mirror reflections of the top-down criteria for natural selection: adaptation and survival.185 Yet, until recently, these present moment stimulus-response behavioral adaptations were considered evolutionarily irrelevant, the functional role of the cell membrane largely unnoticed, with causal genetic control credited to the nucleus (the DNA) alone. Upon the mapping of the genome, however, the subsequent revelations about epigenetic control processes have forever altered the central dogma by elucidating the crucial role of environmental cues, intrinsic signals, and cellular memory in evolution.186–188 Revelations of how supposedly “junk DNA” and noncoding RNA are actually providing ongoing regulatory switching189,190; with relational if-then rules of engagement that ensure specific gene products are brought into action when and only when appropriate,191 and mediating the very developmental morphology of an organism192 as well as its behavior. Revelations of how epigenetic switching yields critical modifications during cellular stress responses,100,193–196 plays a key role in immune functioning,197 and serves as modulators of neuronal responses,198 of neural development and neuroplasticity.199–202 Revelations of how our old friend the methylation marking process, sets down tracks on the histone cores of DNA, yielding heritable memory systems in non-germline cellular replication203; marks that appear to be bidirectional (“poised”) bistable switches themselves204,205 with both bi-directionality and reversibility of DNA methylation crucial to optimal neurodevelopment,206 discoveries that help explain the mysterious phenotypic variations between monozygotic twins207 and highlight the importance of individual differences in behavior, cognition, physiology208—and emotionality.209,210 Indeed, the new field of neuroepigenetics is rapidly evolving, finding disordered methylation markings to be associated with autism, schizophrenia, bipolar, and degenerative disorders.211,212

In sum, the discovery of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms is expanding and reframing the reactive “selfish gene” scenario,213 to a more Lamarckian proactive, fluid, and self-regulating genome, now recognized to be in constant cyclic interaction with the immediate environment, and adaptively switching specific genes on or off in response to ever-changing ecological circumstances. (Of course, these include social environments and the relational components of self-regulation, as evidenced in such emerging fields as “social genomics,”193 “stress genomics,”194 and “social neuroscience.”214) Acknowledging these bottom-up dynamics honors the generative, developmental, symbiotic and cooperative underpinnings within and between living systems and partially deflates the purely competitive, random, blind, meaningless, and glacially slow depiction of evolution. Indeed, as Charles Darwin himself once suggested (in a letter to Nathaniel Wallich, 1881), selection might be ‘the consequence of a much more general law of nature’94—to which I would add: That of the binary computational laws of self-regulatory feedback.

FROM BRANES TO BRAINS AND THE MODERN FEEDBACK CYCLE

These new micro-biological lenses can liberate social scientists from limited evolutionary narratives that look only to conditions of the ancient ancestral environment to elucidate the genetic components of adaptive behavior. Indeed, the “iterated systems” and “algorithms that govern emotional states” in the here- and-now are anything but “irrelevant.”215 They serve as the very self-regulatory core of adaptation itself. In fact, the original molecular sensory organs of the emotional sense (receptor clusters on cellular membranes) remain hard at work regulating each cell of every specialization within its immediate intracellular environment. While the second messengers—and third, and fourth … from phosphates and kinases to neuropeptides and hormones—have become ever-more complex, their original binary computational processes generate the electrical, chemical, and cellular “rhythms”216—the cyclic feedback at every level of scale that delivers self-regulatory “coherence.”217 Examples from the human “receptome”133 include the G-protein-coupled receptors (the largest family of proteins in the human genome218 that mediate responses to hormones and neurotransmitters as well as facilitate vision, olphaction, and taste219; the IP3 receptor (Inositol Thriphosphate receptor) a calcium release channel that switches between open and closed conformations, generating calcium oscillations that in turn regulate periodic hormone secretions220; the β 2 adrenergic receptor that regulates cardiovascular and pulmonary function221; the Syk family of kinases that turn immunoreceptors on or off, and the Src kinases that can “turn up or turn down immune cell signaling responses”222; and T cell antigen receptor complexes that tune immune responses to match the level of the threat223—in the classic homeostatic arrangement.

Nonetheless, the ‘sensory organ’ of emotion now has many additional structural components, from the original membrane receptors and networks of molecules to specialized nodes and networks of neurons (sensory, motor, excitatory, inhibitory, interneurons, etc), and the topological architecture of the human brain.

Dendritic Computations via Feedback

Moreover, the feedback arrangement, with its fractal self-similarity, computational logos and three step cycle (compare, signal, self-correct) is also readily apparent in the structure and function of individual neurons as well.224,225 Indeed, the dendritic spines of pyramidal nerve cells have been discovered to serve as computational building blocks that are fundamental to synaptic plasticity, a discovery with “revolutionary implications for neuroscience.”226 For contrary to Cajal's original notion that action potentials only flow one way (dendrites to soma to axons), it has become clear that they also “backpropagate” in the reverse direction (soma to dendrites). These formerly unacknowledged dendritic computations allow the neuron to sum up synaptic inputs, “compare” that sum against a threshold, and “decide” whether to initiate an action potential, to “operate as a device where analog computations are at some decision point transformed into a digital output signal.”227 We see yet again the ubiquitous binary logos, the pattern of yes/no increases and decreases in synaptic weights to positive and negative exemplars224 and in the reciprocally local and global computations.

Furthermore, the intriguing fact that dendritic spines are suspiciously homologous in size, structure, and chemosensory function to bacteria—a possible ancient symbiont a la mitochondria—has not gone unnoticed.228 In fact, dendritic spines appear to be a morphological link between the early cell receptor complexes and specialized excitable cells—neurons; their dynamic structure and shape-shifting behavior echoing and expanding upon the electrical properties of branes, not mentioned above. For even the E coli has both ligand and voltage gated ion channel receptors, with membrane potential a major component of the driving force for membrane transport and flagellar motion—the energy required to power metabolism and any movement at all. Indeed, voltage spiking has recently been observed in the E coli, with on/off “blinking” associated with aerobic respiration and the stress response.229 Likewise the dynamic growth and shrinkage of the spines themselves follows the same pattern of regulatory increases and decreases (of specialized glutamate receptors) associated with long-term potentiation and damping, correlating with synaptic plasticity, the “self-modifying” cognitive processes that give rise to memory, emotion and executive function230- core elements of human consciousness. Indeed, spine plasticity itself responds to life experience including fear conditioning231, and intriguingly - as with the aforementioned epigenetic methylation marks - altered or disordered spine dynamics, morphology or density, are associated with psychiatric diseases and neurological degeneration.232