Abstract

Background:

OSA is associated with increased risks of respiratory complications following surgery. However, its relationship to the outcomes of hospitalized medical patients is unknown.

Methods:

We carried out a retrospective cohort study of patients with pneumonia at 347 US hospitals. We compared the characteristics, treatment, and risk of complications and mortality among patients with and without a diagnosis of OSA while adjusting for other patient and hospital factors.

Results:

Of the 250,907 patients studied, 15,569 (6.2%) had a diagnosis of OSA. Patients with OSA were younger (63 years vs 72 years), more likely to be men (53% vs 46%), more likely to be married (46% vs 38%), and had a higher prevalence of obesity (38% vs 6%), chronic pulmonary disease (68% vs 47%), and heart failure (28% vs 19%). Patients with OSA were more likely to receive invasive (18.1% vs 9.3%) and noninvasive (28.8% vs 6.8%) forms of ventilation upon hospital admission. After multivariable adjustment, OSA was associated with an increased risk of transfer to intensive care (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.42-1.68) and intubation (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.55-1.81) on or after the third hospital day, longer hospital stays (risk ratio [RR], 1.14; 95% CI, 1.13-1.15), and higher costs (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.21-1.23) among survivors, but lower mortality (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.84-0.98).

Conclusion:

Among patients hospitalized for pneumonia, OSA is associated with higher initial rates of mechanical ventilation, increased risk of clinical deterioration, and higher resource use, yet a modestly lower risk of inpatient mortality.

Pneumonia is the most common infectious cause of hospitalization in the United States, is responsible for > 1 million hospital admissions annually, and has an inpatient mortality of 4% to 9%.1,2 Complications include the development of empyema, sepsis, ARDS, and respiratory failure.3,4

OSA is characterized by repeated collapse and obstruction of the upper airways during sleep, resulting in frequent episodes of hypopnea, apnea, and oxygen desaturation. Epidemiologic studies suggest that the prevalence of moderate OSA is 2% to 7% among women and 7% to 14% among men.5‐8 OSA has been associated with a diverse set of adverse clinical outcomes, including diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmias, and cerebrovascular disease.9‐15 Among patients undergoing surgery, OSA is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications, including oxygen desaturation, respiratory failure, postoperative cardiac events, and transfers to intensive care, but is associated with a paradoxically lower risk of inpatient mortality.16‐19

Little is known about the prevalence or impact of OSA on the outcomes of patients with acute medical conditions, such as pneumonia. We hypothesized that the repeated episodes of hypopnea and apnea that characterize OSA might result in an increased risk of pulmonary complications in the context of acute lower respiratory tract infection and diminished pulmonary reserve. We, therefore, sought to compare the characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with pneumonia who did or did not have OSA.

Materials and Methods

Design, Setting, and Subjects

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients admitted between July 1, 2007, and June 30, 2010, from a geographically and structurally diverse group of 347 US hospitals that contributed data to Perspective (Premier Inc), a voluntary database developed to enable participants to analyze and compare their quality performance and resource use to other institutions. In addition to the information contained in the standard hospital discharge abstract (ie, UB-04), the database contains a daily log of all items and services charged to the patient or their insurer, including medications, laboratory and radiologic tests, and services such as respiratory and physical therapy. Three-fourths of hospitals that participate in Perspective report actual hospital costs (as compared with charges or collections) derived from internal cost-accounting systems, whereas others provide cost estimates calculated using Medicare cost-to-charge ratios. Data are collected electronically from participating sites and audited regularly to ensure data validity. The database represents approximately 15% of all annual US hospital admissions and has been used extensively in clinical epidemiologic and outcomes research.20‐24

We included all patients aged ≥ 18 years with a principal discharge diagnosis code (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]) of pneumonia (481, 482.x [x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9], 483.1, 483.8, 484.8, 485, 486) or a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia when accompanied by a principal diagnosis of respiratory failure (518.81, 518.84), ARDS (518.82), respiratory arrest (799.1), sepsis (038.x [x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9]; 995.91, 995.92; 785.52; 790.7), or influenza (487.0, 487.1, 487.8, 488); who underwent chest radiography; and were treated with antibiotics within 48 h of admission. We excluded patients who were transferred from or to other acute care facilities because we did not have information about treatment received at the initial hospital and could not ascertain final outcomes, those with a length of stay of < 2 days, patients with cystic fibrosis, those with a Medicare Severity Diagnosis-Related Group inconsistent with pneumonia or its sequelae, and those with a present-on-admission modifier code indicating that the pneumonia was not present at admission.

Patient and Hospital Information

In addition to patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, and primary insurance coverage, we recorded the presence of up to 29 unique comorbidities using software provided by the Healthcare Costs and Utilization Project of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.25 We also used ICD-9-CM secondary diagnosis codes to identify patients with atrial fibrillation present at the time of admission. We recorded whether the pneumonia was community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) or health-care-associated pneumonia (HCAP). HCAP was defined based on prior hospitalization within 90 days, admission from a skilled nursing facility, hemodialysis, or immune suppression. Using daily service and supply charges from respiratory therapy and the pharmacy, we assessed receipt and duration of invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation and vasopressors started at admission, defined as the first or second hospital day (e-Table 1 (379KB, pdf) ). We used the first 2 days of hospitalization rather than just the first day because in administrative datasets the duration of the first hospital day includes partial days. OSA was defined based on the presence of a secondary diagnosis code of 327.23. In addition to these patient factors, we recorded key characteristics (number of beds, teaching status, geographic region) for each hospital included in the dataset.

The data do not contain identifiable information. Therefore, the Institutional Review Board at Baystate Medical Center determined that this study did not constitute human subjects research.

Outcomes

The primary study outcome was the development of serious complications after hospital admission, which we defined as transfer to intensive care and initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation taking place after the second hospital day. Secondary outcomes included inpatient mortality, hospital length of stay, and costs.

Analyses

We calculated summary statistics using frequencies and proportions for categorical data and medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. We compared the characteristics of patients who had a diagnosis of OSA with those who did not using χ2 or nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests. We modeled the association between the presence of OSA and the primary and secondary study outcomes while adjusting for the effects of age, sex, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, type of pneumonia, and hospital characteristics. Analyses focused on length of stay, and costs were carried out both in the full sample as well as among the subset of survivors. Length of stay and costs were trimmed at 3 SDs above the mean because of extreme positive skew, and natural log-transformed values were used for analyses. Generalized estimating equations with robust SEs were used to account for the clustering of patients within hospitals. In a sensitivity analysis, we developed regression models on a sample restricted to patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia.

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc) and STATA Stata Statistical Software, release 12 (StataCorp LP).

Results

Patient Characteristics and Initial Management

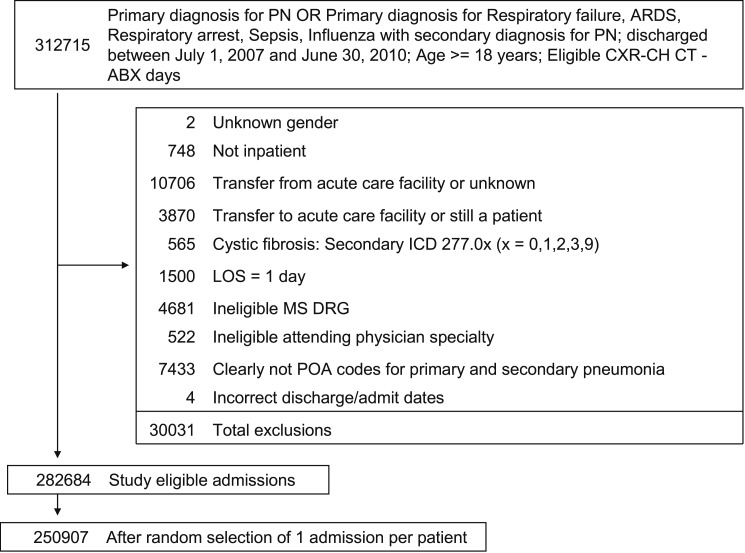

A total of 250,907 patients met our enrollment criteria and were included in the study, of whom 15,569 (6.2%) had a secondary diagnosis of OSA (Fig 1). The median age of the patients was 71 years, 53% were women, and approximately two-thirds were white (Table 1). Hypertension, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, and deficiency anemias were the most commonly recorded comorbidities. Pneumonia was CAP in 165,810 cases (66%) and HCAP in 85,097 cases (34%). The median length of stay in the hospital was 5 days, and median cost per case was $7,751. A total of 18,072 patients (7.2%) died prior to discharge.

Figure 1.

Recruitment. ABX = antibiotic; CH CT = chest CT scan; CXR = chest radiograph; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; LOS = length of stay; MS DRG = Medicare Severity Diagnosis-Related Group; PN = pneumonia; POA = present on admission.

Table 1.

—Characteristics of Patients With and Without OSA Included in the Study

| Characteristic | Overall | No Sleep Apnea | Sleep Apnea | P Value |

| Total | 250,907 (100) | 235,338 (93.8) | 15,569 (6.2) | … |

| Age, median (Q1-Q3), ya | 71 (57-82) | 72 (58-82) | 63 (53-73) | < .001 |

| Female | 133,724 (53.3) | 126,441 (53.7) | 7,283 (46.8) | |

| Race/ethnicity | < .001 | |||

| White | 170,585 (68.0) | 159,690 (67.9) | 10,895 (70.0) | |

| Black | 29,289 (11.7) | 27,202 (11.6) | 2,087 (13.4) | |

| Hispanic | 12,246 (4.9) | 11,587 (4.9) | 659 (4.2) | |

| Other | 38,787 (15.5) | 36,859 (15.7) | 1,928 (12.4) | |

| Marital status | < .001 | |||

| Married | 95,676 (38.1) | 88,577 (37.6) | 7,099 (45.6) | |

| Single | 127,972 (51.0) | 120,734 (51.3) | 7,238 (46.5) | |

| Other/missing | 27,259 (10.9) | 26,027 (11.1) | 1,232 (7.9) | |

| Insurance payor | < .001 | |||

| Medicare | 169,483 (67.6) | 159,934 (68.0) | 9,549 (61.3) | |

| Medicaid | 20,612 (8.2) | 18,995 (8.1) | 1,617 (10.4) | |

| Managed care | 34,864 (13.9) | 32,060 (13.6) | 2,804 (18.0) | |

| Commercial-indemnity | 9,492 (3.8) | 8,755 (3.7) | 737 (4.7) | |

| Other | 16,456 (6.6) | 15,594 (6.6) | 862 (5.5) | |

| Admitting physician specialty | < .001 | |||

| Critical care medicine or pulmonary diseases | 16,131 (6.4) | 14,586 (6.2) | 1,545 (9.9) | |

| Family practice | 40,506 (16.1) | 38,350 (16.3) | 2,156 (13.8) | |

| Internal and geriatric medicine | 117,201 (46.7) | 7,062 (45.4) | 110,139 (46.8) | |

| Hospital medicine | 43,887 (17.5) | 40,730 (17.3) | 3,157 (20.3) | |

| Other specialty | 33,182 (13.2) | 31,533 (13.4) | 1,649 (10.6) | |

| Type of pneumonia | .38 | |||

| HCAP | 85,097 (33.9) | 79,867 (33.9) | 5,230 (33.6) | |

| CAP | 165,810 (66.1) | 155,471 (66.1) | 10,339 (66.4) | |

| Comorbiditiesb | ||||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 121,890 (48.6) | 111,355 (47.3) | 10,535 (67.7) | < .001 |

| Hypertension | 116,574 (46.5) | 108,430 (46.1) | 8,144 (52.3) | < .001 |

| Diabetes | 59,709 (23.8) | 53,451 (22.7) | 6,258 (40.2) | < .001 |

| Deficiency anemias | 55,744 (22.2) | 52,638 (22.4) | 3,106 (19.9) | < .001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 49,479 (19.7) | 45,081 (19.2) | 4,398 (28.2) | < .001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 45,651 (18.2) | 42,524 (18.1) | 3,127 (20.1) | < .001 |

| Renal failure | 32,075 (12.8) | 29,571 (12.6) | 2,504 (16.1) | < .001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 28,851 (11.5) | 26,939 (11.4) | 1,912 (12.3) | .002 |

| Depression | 26,244 (10.5) | 24,123 (10.3) | 2,121 (13.6) | < .001 |

| Other neurologic disorders | 25,650 (10.2) | 24,457 (10.4) | 1,193 (7.7) | < .001 |

| Obesity | 20,364 (8.1) | 14,475 (6.2) | 5,889 (37.8) | < .001 |

| Weight loss | 15,877 (6.3) | 15,337 (6.5) | 540 (3.5) | < .001 |

| Valvular disease | 15,789 (6.3) | 14,829 (6.3) | 960 (6.2) | .5 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 14,170 (5.7) | 13,292 (5.6) | 878 (5.6) | 1.0 |

| Pulmonary circulation disease | 12,328 (4.9) | 10,465 (4.4) | 1,863 (12.0) | < .001 |

| Initial receipt of noninvasive ventilationc | 20,573 (8.2) | 16,084 (6.8) | 4,489 (28.8) | < .001 |

| Initial receipt of invasive ventilationc | 24,786 (9.9) | 21,974 (9.3) | 2,812 (18.1) | < .001 |

| Initial treatment with vasopressorsc | 21,177 (8.4) | 19,774 (8.4) | 1,403 (9.0) | .01 |

| Principal diagnosis | < .001 | |||

| Pneumonia/influenza | 178,293 (71.1) | 168,411 (71.6) | 9,882 (63.5) | |

| Sepsis | 50,898 (20.3) | 48,258 (20.5) | 2,640 (17.0) | |

| Respiratory failure/arrest | 21,716 (8.7) | 18,669 (7.9) | 3,047 (19.6) | |

| Hospital characteristics | ||||

| Bed size | < .001 | |||

| ≤ 200 beds | 49,929 (19.9) | 47,248 (20.1) | 2,681 (17.2) | |

| 201-400 beds | 97,818 (39.0) | 91,993 (39.1) | 5,825 (37.4) | |

| > 400 beds | 103,160 (41.1) | 96,097 (40.8) | 7,063 (45.4) | |

| Rural/urban status | < .001 | |||

| Rural | 33,480 (13.3) | 31,858 (13.5) | 1,622 (10.4) | |

| Urban | 217,427 (86.7) | 203,480 (86.5) | 13,947 (89.6) | |

| Teaching status | < .001 | |||

| Teaching | 86,919 (34.6) | 81,124 (34.5) | 5,795 (37.2) | |

| Nonteaching | 163,988 (65.4) | 154,214 (65.5) | 9,774 (62.8) | |

| Region | < .001 | |||

| Northeast | 41,037 (16.4) | 38,927 (16.5) | 2,110 (13.5) | |

| Midwest | 55,301 (22.0) | 51,506 (21.9) | 3,795 (24.4) | |

| West | 42,719 (17.0) | 40,217 (17.1) | 2,502 (16.1) | |

| South | 111,850 (44.6) | 104,688 (44.5) | 7,162 (46.0) | |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Inpatient mortality | 18,072 (7.2) | 17,263 (7.3) | 809 (5.2) | < .001 |

| Late transfer to ICUd | 7,410 (3.6) | 6,783 (3.5) | 627 (5.6) | < .001 |

| Late initiation of invasive ventilationd | 8,949 (4.0) | 8,118 (3.8) | 831 (6.5) | < .001 |

| LOS, median (Q1-Q3),a y | 5 (3-8) | 5 (3-8) | 6 (4-9) | < .001 |

| LOS, median (Q1-Q3),a y among survivors | 5 (3-8) | 5 (3-8) | 6 (4-9) | < .001 |

| Costs, median (Q1-Q3),a $ | 7,751 (4,854-13,915) | 7,637 (4,799-13,648) | 9,827 (5,886-18,145) | < .001 |

| Costs, median (Q1-Q3),a $ among survivors | 7,424 (4,728-12,904) | 7,310 (4,675-12,645) | 9,425 (5,750-16,960) | < .001 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise noted. CAP = community-acquired pneumonia; HCAP = health-care-associated pneumonia; LOS = length of stay; Q = quartile. P based on χ2 tests.

P based on Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Comorbidities < 5%: psychoses, rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular disease, solid tumor without metastasis, metastatic cancer, paralysis, alcohol abuse, liver disease, drug abuse, lymphoma, chronic blood loss anemia.

Days 1 or 2.

Day 3 or later.

When compared with those without OSA, patients with OSA were younger (63 years vs 72 years) and more likely to be men (53% vs 46%), white (70% vs 68%), and married (46% vs 38%) (Table 1). We observed substantial differences in the comorbidity profile of patients with and without OSA. For example, patients with OSA were much more likely to be diagnosed with obesity (38% vs 6%), chronic pulmonary disease (68% vs 47%), diabetes (40% vs 23%), heart failure (28% vs 19%), and hypertension (52% vs 46%) than those without. However, patients with and without OSA were equally likely to have HCAP (33.6% vs 33.9%).

Regarding initial management, patients with OSA were far more likely to be treated with mechanical ventilation on the first or second hospital day, including both invasive (18.1% vs 9.3%) and noninvasive forms of ventilation (28.8% vs 6.8%). Among those who received invasive mechanical ventilation, patients with and without OSA spent a median of 5 days on the ventilator. The percentage of patients who received vasopressors was similar between the two groups (9.0% vs 8.4%).

Complications and Other Outcomes

The incidence of serious complications after admission was higher among patients with OSA. Those with sleep apnea were more likely to have invasive mechanical ventilation initiated after the second hospital day compared to those without OSA (6.5% vs 3.8%). Similarly, transfer to the ICU on or after hospital day 3 was more common among patients with OSA (5.6% vs 3.5%). In-hospital mortality was lower among patients with OSA (5.2% vs 7.3%).

Results of Multivariable Analyses

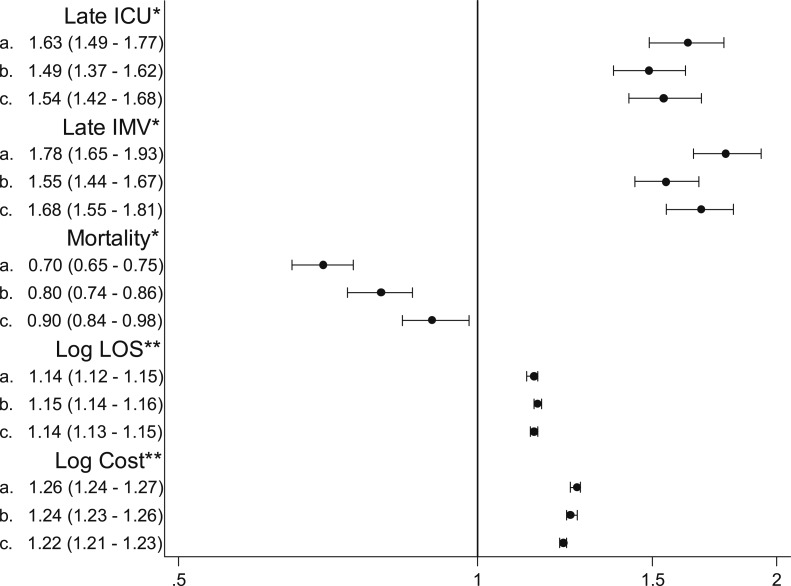

In a generalized estimating equation model that accounted for patient demographics, comorbidities, whether the pneumonia was CAP or HCAP, admitting physician specialty, hospital type, and the effects of clustering, OSA was associated with an increased risk of transfer to the ICU on hospital day 3 or later (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.42-1.68) as well as the initiation of mechanical ventilation on day 3 or later (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.55-1.81). OSA was also associated with 14% longer length of stay (95% CI, 13%-15%) and 22% higher costs (95% CI, 21%–23%) among survivors. In contrast, after adjustment we found somewhat lower mortality associated with OSA (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.84-0.98) (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

ORs and risk ratios for the association between OSA and patient outcomes. All models account for clustering of patients in hospitals. a: Unadjusted; b: Adjusted for demographics, admitting physician specialty, and hospital characteristics; c: Adjusted for health-care-associated pneumonia vs community-acquired pneumonia, demographics, admitting physician specialty, hospital characteristics, and comorbidities. *OR (95% CI). **Risk ratio (95% CI) among survivors. IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Sensitivity Analysis

When we restricted the analysis to patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia, OSA was still associated with an increased risk of late transfer to the ICU (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.36-1.71) and late initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.70-2.10), but there was no longer a statistically significant association with mortality (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.83-1.09) (Table 2, e-Tables 2 (379KB, pdf) , 3 (379KB, pdf) ).

Table 2.

—Results of Sensitivity Analyses

| Analysis | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Late ICU | Late IMV | Mortality | |

| Analysis restricted to patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia | |||

| Unadjusteda | 1.62 (1.45-1.81) | 2.01 (1.75-2.31) | 0.69 (0.61-0.79) |

| Adjusted for patient demographics, admitting physician, hospital characteristicsa | 1.52 (1.36-1.70) | 1.78 (1.61-1.97) | 0.85 (0.75-0.97) |

| Adjusted for patient demographics, admitting physician, comorbidities, hospital characteristics, HCAP vs CAPa | 1.53 (1.36-1.71) | 1.89 (1.70-2.10) | 0.95 (0.83-1.09) |

IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Generalized estimating equation models accounting for clustering of patients within hospitals.

Discussion

In this large observational study, we found OSA to be a common comorbidity among patients hospitalized for pneumonia. Although patients with sleep apnea were close to 10 years younger on average, they had a substantially higher prevalence of serious comorbidities, including chronic pulmonary disease and heart failure; were more than twice as likely to require invasive mechanical ventilation at the time of admission; and had > 50% increased odds of clinical deterioration requiring transfer to the ICU and initiation of invasive ventilation later in the hospital stay. Together, these factors led patients with OSA to have increased length of stay and higher hospital costs compared to those without sleep apnea. Interestingly, despite the higher rate of complications, we did not find an increased risk of mortality; instead, we observed a somewhat lower risk of mortality compared to patients without OSA.

One possible explanation for these findings is that in the context of pneumonia, in which there are increased levels of ventilation-perfusion mismatch and higher minute ventilation,26 episodes of hypopnea, apnea, and the resulting oxygen desaturation are poorly tolerated. As a consequence, patients with pneumonia with OSA are more likely to exhibit signs of respiratory failure than other patients. This appears to be the case both at the time of admission as well as later in the course of the hospitalization. One can hypothesize, then, that the intubation of patients with OSA may, in some cases, be precipitated by apnea- and hypopnea-related episodes of hypoxia, made worse by the acute consolidation of pneumonia. In contrast, among patients without sleep apnea, intubation generally signals the development of severe sepsis, ARDS, or both. This may also help explain the apparent paradox we observed of a higher incidence of serious complications that was not accompanied by an increased risk of mortality. Another possibility is that the lower mortality we observed among patients with sleep apnea may be due to increased mechanical ventilation at the time of admission, thereby avoiding later complications. Finally, obesity was far more prevalent among the patients with sleep apnea. The obesity paradox, which is the observation that obese patients have better outcomes in the face of acute illness, potentially due to earlier presentation to medical care or increased metabolic reserves, should also be considered.27,28

Although, to our knowledge, this is the first study of OSA in the setting of pneumonia, the relationship of sleep apnea to the outcomes of patients undergoing surgery has been the focus of prior investigation. In an analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample, Memtsoudis and colleagues16 reported that 1.4% to 2.5% of patients undergoing major orthopedic and general surgical procedures had an ICD-9-CM code indicative of OSA, and this was associated with an increased risk of pulmonary complications, including pneumonia, ARDS, and postoperative respiratory failure requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. In two more recent studies using the nationwide inpatient sample, Mokhlesi and colleagues18,19 found that surgical patients with sleep apnea who underwent a diverse set of elective surgical procedures, including bariatric surgery, had reduced risk of mortality compared to those without sleep apnea. Our findings of an increased risk of complications but decreased mortality among patients with sleep apnea who are hospitalized for pneumonia extend these observations to another large, high-risk population.

Strengths of this study include the large number of patients and diverse set of hospitals, increasing the generalizability of our results. In addition, we took advantage of daily billing records to assess receipt and duration of invasive and noninvasive ventilation, vasopressors, and ICU transfer. Our results were also robust to a sensitivity analysis limited to patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia.

Nevertheless, our findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, we used ICD-9-CM codes to identify cases of OSA, and it is likely that the true percentage of patients with OSA in our sample was higher than the 6.2% that we reported. Such an interpretation is supported by epidemiologic studies, which have estimated the prevalence of mild OSA to be 20% among adults29 and sleep-disordered breathing to affect 56% of women and 70% of men > 65 years of age.30 Second, it is possible that the patients who receive a diagnosis of OSA in the hospital represent those with the most severe disease. If this is true, it is possible that our results may have overestimated the impact of OSA on patient outcomes, such as the risk of respiratory complications. At the same time, a large number of cases of unrecognized sleep apnea in the group we did not consider to have apnea would have had the opposite effect, biasing our results toward the null. Third, we did not have information about use of positive airway pressure prior to admission or to the possible “carry-over” effect from use or withdrawal of home positive airway pressure in the hospital. Finally, we did not have information on the do not resuscitate status of patients. Although our models adjusted for differences in patient age, the higher initial rates of ventilation, higher rates of late transfer to the ICU and late initiation of ventilation, and similar if not lower overall mortality may have been partially influenced by preferences for care.

Conclusions

OSA is a common comorbidity among patients with pneumonia associated with increased receipt of mechanical ventilation upon hospital admission, higher rates of complications during the hospital stay, yet a somewhat lower risk of mortality. Additional research is needed to identify the factors that underlie these observations.

Supplementary Material

Online Supplement

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Dr Lindenauer is responsible for the overall content of the study as guarantor.

Dr Lindenauer: contributed to conception, hypothesis delineation, and design of the study; acquisition of the data or the analysis and interpretation of such information; and writing the article or substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission.

Dr Stefan: contributed to conception, hypothesis delineation, and design of the study; acquisition of the data or the analysis and interpretation of such information; and writing the article or substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission.

Dr Johnson: contributed to conception, hypothesis delineation, and design of the study; acquisition of the data or the analysis and interpretation of such information; and writing the article or substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission.

Ms Priya: contributed to acquisition of the data or the analysis and interpretation of such information and writing the article or substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission.

Dr Pekow: contributed to acquisition of the data or the analysis and interpretation of such information and writing the article or substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission.

Dr Rothberg: contributed to conception, hypothesis delineation, and design of the study; acquisition of the data or the analysis and interpretation of such information; and writing the article or substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Role of sponsors: The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality nor the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Additional information: The e-Tables can be found in the “Supplemental Materials” area of the online article.

Abbreviations

- CAP

community-acquired pneumonia

- HCAP

health-care-associated pneumonia

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

Footnotes

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [Grant R01HS018723]. Dr Stefan is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health [Grant K01HL114631].

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians. See online for more details.

References

- 1.FASTSTATS - pneumonia. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/pneumonia.htm. Accessed September 29, 2011

- 2.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh M-S, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003-2009. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1405-1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrie TJ, Durant H, Yates L. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization: 5-year prospective study. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(4):586-599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menendez R, Torres A. Treatment failure in community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2007;132(4):1348-1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230-1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in women: effects of gender. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(3 pt 1):608-613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Ten Have T, Tyson K, Kales A. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(1):144-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durán J, Esnaola S, Rubio R, Iztueta A. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and related clinical features in a population-based sample of subjects aged 30 to 70 yr. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(3 pt 1):685-689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378-1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peker Y, Kraiczi H, Hedner J, Löth S, Johansson A, Bende M. An independent association between obstructive sleep apnoea and coronary artery disease. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(1):179-184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, et al. ; Sleep Heart Health Study. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(8):910-916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arzt M, Young T, Finn L, Skatrud JB, Bradley TD. Association of sleep-disordered breathing and the occurrence of stroke. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(11):1447-1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coughlin SR, Mawdsley L, Mugarza JA, Calverley PMA, Wilding JPH. Obstructive sleep apnoea is independently associated with an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(9):735-741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valham F, Mooe T, Rabben T, Stenlund H, Wiklund U, Franklin KA. Increased risk of stroke in patients with coronary artery disease and sleep apnea: a 10-year follow-up. Circulation. 2008;118(9):955-960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redline S, Yenokyan G, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(2):269-277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Memtsoudis S, Liu SS, Ma Y, et al. Perioperative pulmonary outcomes in patients with sleep apnea after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(1):113-121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaw R, Chung F, Pasupuleti V, Mehta J, Gay PC, Hernandez AV. Meta-analysis of the association between obstructive sleep apnoea and postoperative outcome. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109(6):897-906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mokhlesi B, Hovda MD, Vekhter B, Arora VM, Chung F, Meltzer DO. Sleep-disordered breathing and postoperative outcomes after elective surgery: analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample. Chest. 2013;144(3):903-914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokhlesi B, Hovda MD, Vekhter B, Arora VM, Chung F, Meltzer DO. Sleep-disordered breathing and postoperative outcomes after bariatric surgery: analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample. Obes Surg. 2013;23(11):1842-1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindenauer PK, Pekow P, Wang K, Gutierrez B, Benjamin EM. Lipid-lowering therapy and in-hospital mortality following major noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2092-2099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auerbach AD, Hilton JF, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB, Lindenauer PK. Shop for quality or volume? Volume, quality, and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(10):696-704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothberg MB, Lahti M, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK.Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among medical patients at US hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):489-494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lagu T, Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, et al. Development and validation of a model that uses enhanced administrative data to predict mortality in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(11):2425-2430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinberger SE, Cockrill BA, Mandel J. Principles of Pulmonary Medicine. 5th ed Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Memtsoudis SG, Bombardieri AM, Ma Y, Walz JM, Chiu YL, Mazumdar M. Mortality of patients with respiratory insufficiency and adult respiratory distress syndrome after surgery: the obesity paradox. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27(5):306-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bucholz EM, Rathore SS, Reid KJ, et al. Body mass index and mortality in acute myocardial infarction patients. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):796-803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shamsuzzaman ASM, Gersh BJ, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea: implications for cardiac and vascular disease. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1906-1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Mason WJ, Fell R, Kaplan O. Sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1991;14(6):486-495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Online Supplement