Abstract

Evidence suggests epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) as one potential source of fibroblasts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. To assess the contribution of alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) EMT to fibroblast accumulation in vivo following lung injury and the influence of extracellular matrix on AEC phenotype in vitro, Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice were generated in which AEC permanently express green fluorescent protein (GFP). On days 17-21 following intratracheal bleomycin administration, ~4% of GFP-positive epithelial-derived cells expressed vimentin or α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). Primary AEC from Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice cultured on laminin-5 or fibronectin maintained an epithelial phenotype. In contrast, on type I collagen, cells of epithelial origin displayed nuclear localization of Smad3, acquired spindle-shaped morphology, expressed α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and phospho-Smad3, consistent with activation of the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) signaling pathway and EMT. α-SMA induction and Smad3 nuclear localization were blocked by the TGFβ type I receptor (TβRI, otherwise known as Alk5) inhibitor SB43154, while AEC derived from Nkx2.1-Cre;Alk5flox/KO mice did not undergo EMT on collagen, consistent with a requirement for signaling via Alk5 in collagen-induced EMT. Inability of a pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody to inhibit effects of collagen together with absence of active TGFβ in culture supernatants is consistent with TGFβ ligand-independent activation of Smad signaling. These results support the notion that AEC can acquire a mesenchymal phenotype following injury in vivo and implicate type I collagen as a key regulator of EMT in AEC through signaling via Alk5, likely in a TGFβ ligand-independent manner.

Keywords: pulmonary fibrosis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), TGFβ type I receptor (Alk5), alveolar epithelial cells

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive disease characterized by fibroblast/myofibroblast accumulation and excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins leading to destruction of alveolocapillary units and impaired gas exchange [1]. The origin of lung fibroblasts/myofibroblasts in IPF is not well-defined, but possible sources include resident lung fibroblasts, marrow-derived circulating progenitors and alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) via epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [2]. EMT is central to cancer development and progression [3-4] and has been increasingly suggested to contribute to organ fibrosis in kidney [5-6], liver [7] and, more recently, lung [4, 8]. Mice permanently expressing β-galactosidase (β-gal) or green fluorescent protein (GFP) in AEC were used to demonstrate EMT in lung fibrosis following administration of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGFβ1) or bleomycin [9-10]. However, a role for EMT during lung fibrosis and fibrosis in other organs remains controversial, in part because of technical limitations associated with co-localization using the β-gal reporter [11] and lack of specificity of some mesenchymal markers that have been evaluated [8, 12].

Despite alterations in expression of ECM components in IPF, most studies of disease pathogenesis have focused on effects of growth factors or cytokines (e.g., TGFβ1) on proliferation of fibroblasts and/or EMT, rather than on a potential causal role of ECM components themselves. Basement membranes are thin layers of highly organized ECM comprised primarily of type IV collagen, laminin 332 (or laminin-5), entactin and heparin sulfate proteoglycans that provide a dynamic supporting structure for epithelial cells and are known to influence cellular behaviors such as differentiation and proliferation [13, 14]. Several studies suggest that degradation of basement membrane proteins by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [15-17] is altered in IPF [16] and may contribute to disease pathogenesis. In contrast to the complex ECM suprastructures comprising the basement membrane, interstitial matrix is a loosely organized form of ECM predominantly composed of fibrillar type I and III collagens, elastic fibers and heparin sulfate proteoglycans [14, 18]. Denudation of basement membrane exposes AEC to interstitial fibrillar collagens and/or degraded or monomeric collagens (type I, III, and/or IV), allowing direct interactions with integrins α1β1 and α2β1, the two major epithelial receptors for collagens. A role for monomeric type I collagen has been implicated in the induction of EMT in lung [21], breast [22] and pancreatic [23-26] carcinoma cell lines. However, little is known regarding the influence of ECM on EMT in primary epithelial cells or the downsteam signaling pathways that may mediate this process.

We generated a novel transgenic mouse line, Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG, in which AEC permanently express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in order to evaluate the influence of ECM proteins on the capacity of AEC to undergo EMT in vitro and to contribute to fibroblast/myofibroblast accumulation in the course of pulmonary fibrosis in vivo. Our results demonstrate that AEC undergo EMT in vitro and in vivo and implicate type I collagen as a key regulator of EMT in AEC through signaling via Alk5, likely in a TGFβ ligand-independent manner.

Methods

Animals

Nkx2.1-Cre mice [28] (Stewart A. Anderson (Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY)) were crossed to mT/mG reporter mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to generate double heterozygous animals. Expression of the GFP reporter gene from the mT/mG knockin allele is dependent on Cre/loxP recombination, where deletion of a loxP-flanked stop sequence results in activation of GFP and simultaneous deletion of Tomato. Mice containing a heterozygous deletion of exon 3 in the Alk5 gene and a floxed allele of this exon, Alk5flox/KO, were generated as previously described [29]. Mice deficient for Alk5 in AEC were generated by crossing Alk5flox/KO to Nkx2.1-Cre driver mice. Mice were raised in a pathogen-free environment and given food and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee at the USC Keck School of Medicine.

Bleomycin-induced lung injury

Mice 8–10 weeks old were injected intratracheally with bleomycin (1 U/kg; Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ) or saline in a volume of 50 μL after sedation with ketamine/xylazine. Mice were analyzed on days 17–21 following bleomycin administration.

Mouse AT2 cell isolation and culture

AT2 cells were isolated from adult mice of both genders using dispase (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) digestion/agar instillation as previously described [30] (see Supporting Information). To prepare 2-dimensional monomeric ECM, Transwell polycarbonate filters (0.4 μm pore size, 1.1 cm2; Corning Costar, Corning, NY) were coated with 100 μg/mL type I collagen (Advanced BioMatrix, San Diego, CA), 1 μg/mL laminin-5 (Chemicon, Billerica, MA) or 10 μg/mL fibronectin (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature [31]. TGFβ isoforms in type I collagen solution were not detected by silver staining of SDS-PAGE gels and would have been degraded by pepsin enzymatic digestion according to the manufacturer's specifications. AT2 cells isolated from Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG, Nkx2.1-Cre;Alk5flox/KO or Alk5flox/KO mice were cultured in complete mouse medium (CMM) plus 2% newborn bovine serum (NBS; Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA) and plated at 7.5x105 cells/cm2. Medium was replaced with serum-free CMM on day 2 post-plating and every other day thereafter. The TGFβ type I receptor inhibitor SB431542 (Sigma), pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody (AB-100-NA; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or TGFβ1 (R&D Systems) were added on day 2 post-plating at 10 μM, 2.5 μg/mL and 2.5 ng/mL, respectively. Transepithelial resistance (RT) and potential difference (PD) were measured using a MilliCell-ERS device equipped with silver/silver chloride electrodes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Equivalent short-circuit current (IEQ, μA/cm2) was calculated from Ohm's law (IEQ = PD/RT). Only monolayers that achieved RT values ≥1 kΩ·cm2 were studied.

Flow cytometry

Crude single-cell suspensions were prepared from saline- and bleomycin-injured mouse lungs using the dispase digestion/agar instillation isolation method without use of negative selection antibodies. Cells were analyzed and sorted for GFP expression using a FACS Aria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences).

Fluorescence microscopy

GFP and Tomato fluorescence were directly observed in lung cryosections (5–7 μm thickness), cytospins of isolated lung cells and mouse AEC monolayers (MAECM) derived from Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice. Immunofluorescence was used to evaluate expression and localization of epithelial and mesenchymal markers and Smad3 (see Supporting Information). Nuclear staining was accomplished with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) Vectashield mount (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were acquired with a Zeiss confocal microscope 510 Meta NLO CLSM imaging system (Jena, Germany) equipped with argon and red/green HeNe lasers or a Qimaging Retiga 2000R digital camera (Qimaging, Surrey, BC) attached to a Nikon Eclipse 80i (Nikon, Melville, NY).

Western analysis of FACS-sorted GFP-expressing cells

All cells (expressing either Tomato or GFP) comprising MAECM grown on type I collagen or laminin-5 were trypsinized (0.25% in 5 mM EDTA) after 8 or 14 days in primary culture. GFP-positive cells were purified using flow cytometry and protein from only the GFP-positive cell population was harvested using 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer. Western blots were performed as previously described [30] (see Supporting Information). Antigen-antibody complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and analyzed with an Alpha Ease RFC Imaging System (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Detection of TGFβ1 in culture medium

TGFβ1 protein was quantified using an ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Neutral serum-free CMM was used to determine active TGFβ1 concentrations. Serum-free CMM that was acidified and subsequently neutralized according to the manufacturer's instructions was used to determine total TGFβ1 concentrations.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error. Significance (P < 0.05) was determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by post-hoc procedures based on modified Student-Newman-Keuls tests. For ratiometric data, we used z-tests to determine differences from control. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Analysis of reporter expression in distal lung of Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice

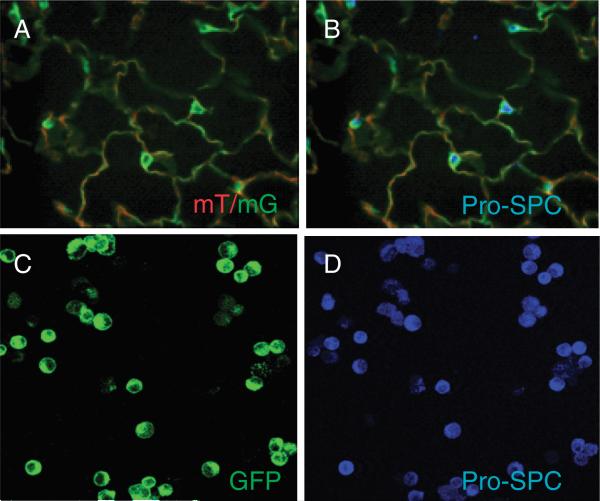

Nkx2.1 (or thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1)) is expressed in all pulmonary epithelial cells during lung development and becomes restricted to AT2 and Clara cells towards the end of gestation and postnatally [32]. To confirm AEC-specific expression of GFP, frozen lung sections from Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice were immunostained for pro-SPC (Figure 1A-B). GFP-positive cells were immunoreactive for pro-SPC, confirming expression in AT2 cells. All GFP-positive AT2 cells isolated from Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice were immunoreactive for pro-SPC (Figure 1C-D), confirming GFP reporter expression in AT2 cells. A subset of pro-SPC-positive AT2 cells (<20%) did not express GFP, suggesting that the efficiency of Cre/LoxP-mediated recombination of GFP was not 100%, consistent with prior reports of recombination efficiency in the mT/mG reporter line [27, 33]. Nevertheless, recombination efficiency >80% in AT2 cells demonstrates feasibility of a cell fate mapping strategy based on AEC-specific expression of GFP in this newly derived mouse line.

Figure 1.

GFP-positive AEC from lungs of Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice express pro-SPC. A and B: Lung cryosection from an Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mouse expressing GFP and Tomato (A; green and red) was immunostained for pro-SPC (B; blue). GFP-positive cells were immunoreactive for pro-SPC, indicating that GFP is expressed in AT2 cells. Magnification x40. C and D: Freshly isolated AT2 cells from Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice expressing GFP (C) were immunostained for pro-SPC (D; blue). All GFP-positive cells were reactive for pro-SPC. A subset of cells (~16%) were pro-SPC positive but did not express GFP, indicating that Cre/LoxP- mediated recombination of mT/mG occurs in >80% of AT2 cells. Results are representative of n = 4 independent experiments. Original magnification x40.

AEC undergo EMT in vivo in response to bleomycin instillation in Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice

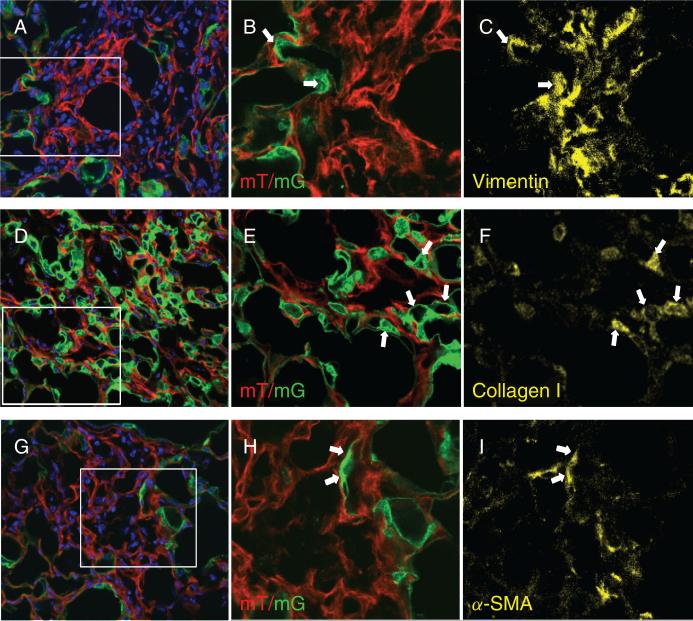

To evaluate EMT in vivo, double transgenic Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice received intratracheal instillation of saline ± bleomycin sulfate (1 U/kg). After 21 days, immunostaining of lung cryosections with vimentin (Figure 2A–C), type I collagen (Figure 2D–F) or α-SMA (Figure 2G–I) demonstrates co-localization with the GFP reporter, indicating that a subset of AEC-derived cells express mesenchymal markers after bleomycin treatment. The GFP reporter did not co-localize with mesenchymal markers in situ in saline-treated lungs (see Supporting Information, Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Detection of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in lung sections of Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG reporter mice 21 days post-bleomycin instillation. Confocal images demonstrate co-localization of membrane-associated GFP with mesenchymal markers vimentin (A–C), type I collagen (D–F), and α-SMA (G–I). Panels A, D and G show direct detection of Tomato and GFP (red and green) in sections counterstained with DAPI (blue). Original magnification x40. Panels B, E and H show magnified views of the rectangles shown in panels A, D and G, respectively, after cropping and re-sizing using Adobe Photoshop. Lung sections were immunostained for vimentin (C), type I collagen (F) and α-SMA (I) as shown in yellow. Arrows point to representative cells which co-express GFP and mesenchymal markers. Thresholds of staining intensity for the three primary antibodies were established using reference sections treated with only secondary antibodies.

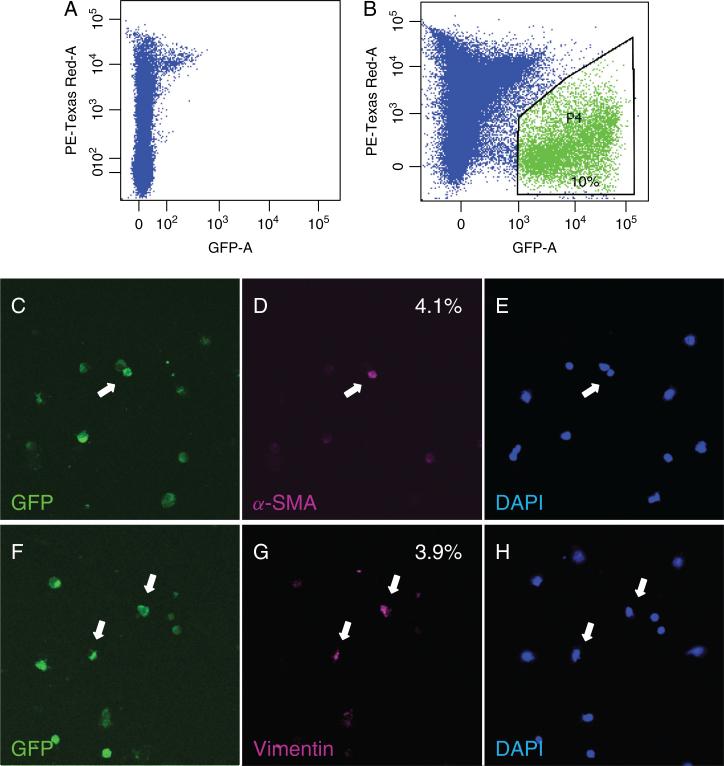

To precisely quantify the contribution of alveolar EMT to accumulation of fibroblasts/myofibroblasts, crude single-cell suspensions were prepared from saline- and bleomycin-injured lungs of AEC reporter mice and purified by FACS followed by immunostaining for α-SMA and vimentin. ~10% of crude lung cell populations from reporter mice expressed GFP (Figure 3B); lung cells isolated from single transgenic mT/mG mice did not express GFP after bleomycin injury (Figure 3A). Expression of α-SMA or vimentin was observed in 4.1 ± 1.3% and 3.9 ± 1.0% of AEC-derived GFP-expressing cells, respectively, on days 17-21 post-administration of bleomycin (Figure 3C–H), but not in saline-treated mice. Co-localization of GFP with vimentin or α-SMA in frozen lung sections and single cell suspensions prepared from bleomycin-injured reporter mice indicates that AEC express mesenchymal markers in vivo in response to bleomycin.

Figure 3.

GFP-sorted cells from bleomycin-injured lung of Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice express vimentin and α-SMA. Representative GFP-FACS profiles of lung cells from a single transgenic mT/mG (A) and double transgenic Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mouse (B) 21 days after intratracheal administration of bleomycin. Percentage of GFP-positive cells is indicated in B. GFP-expressing cells of epithelial origin express mesenchymal markers on days 17-21 post-instillation of bleomycin (C–H). GFP-sorted cells were immunostained for α-SMA (D; magenta) and vimentin (G; magenta). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (E and H; blue). Approximately 4% of cells of epithelial origin expressed α-SMA or vimentin in bleomycin-injured mice. None of the GFP-positive cells expressed mesenchymal markers in saline-treated mice. n = 5 bleomycin- and saline-treated mice. Arrows point to GFP-positive cells which express α-SMA or vimentin. Original magnification x20.

Characterization of MAECM grown on various extracellular matrices in the absence or presence of TGFβ1

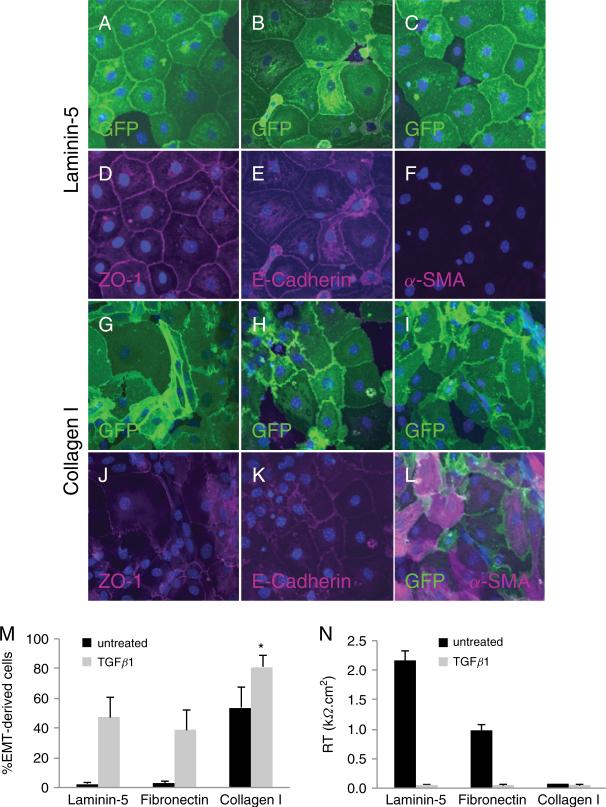

. We compared effects of monomeric type I collagen, monomeric laminin-5 and fibronectin on AEC phenotype. AT2 cells from Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice grown on laminin-5 formed confluent monolayers with characteristic cobblestone-like morphology after 8 days in culture (Figure 4A–C). Immunoreactivity for ZO-1 and E-cadherin was localized to cell-cell contacts in the majority of cells (Figure 4D-E), including occasional cells which did not express the GFP reporter. Reactivity for α-SMA was absent (Figure 4F). Mouse AEC grown on fibronectin exhibited similar morphology and localization of cell-cell junctional and adherens proteins, ZO-1 and E-cadherin, as seen in AEC grown on laminin-5 (see Supporting Information, Figure S2). In contrast, GFP-positive cells grown on type I collagen after 8 days in culture exhibited an irregular morphology (Figure 4G–I), with less intense localization of ZO-1 and E-cadherin at cell-cell contacts (Figure 4J-K). α-SMA co-localized with GFP in epithelial-derived cells (Figure 4L), demonstrating that primary AEC undergo EMT when grown on type I collagen.

Figure 4.

Characterization of MAECM grown on laminin-5 and type I collagen. Mouse AT2 cells from Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG mice plated on laminin-5-coated filters form confluent monolayers with a cobblestone-like morphology after 8 days in culture (A–C). GFP was directly observed in the majority of AEC within the monolayers. A subset of cells did not express GFP, consistent with the observation that Cre/loxP recombination driven by Nkx2.1 is not 100% efficient. Reactivity for ZO-1 and E-cadherin was localized to cell-cell contacts in the majority of cells (D and E; magenta), indicating a relatively pure epithelial cell population. Reactivity for α-SMA was absent (F). AT2 cells plated on collagen I-coated filters exhibit a disorganized and irregular morphology after 8 days in culture as shown by direct GFP expression (G–I). ZO-1 was redistributed from cell borders to the cytoplasm in a subset of cells (J; magenta). Localization of E-cadherin at cell borders was reduced (K; magenta). Reactivity of α-SMA was observed in the majority of GFP-labeled AEC (L; magenta). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Photographs are representative of 4 separate experiments. Original magnification x40. M: Semi-quantitative analysis of the percentage of GFP reporter-positive cells which expressed α-SMA on various ECM proteins in the presence or absence of TGFβ1; mean of 4 low-power fields (x20) per monolayer ± SEM (n = 1 monolayer per ECM condition per preparation from 3 different cell preparations). N: Effect of ECM proteins on RT of MAECM after 8 days in culture in the presence and absence of TGFβ1 (2.5 ng/mL). Values are mean ± SE (n = 1 monolayer per ECM component per preparation from 4 different cell preparations). *P <0.05 vs all other conditions.

TGFβ has been shown to mediate EMT in vitro [35] and in vivo [36]. In the present study, GFP-positive cells grown on laminin-5 and exposed to TGFβ1 (2.5 ng/mL) on days 2–8 in culture exhibited fibroblast-like morphology after 8 days (see Supporting Information, Figure S3A–C) compared to AEC grown on laminin-5 in the absence of TGFβ1 (Figure 4A–C). Furthermore, immunoreactivity for ZO-1 was decreased at cell borders (Figure S3D). Localization of E-cadherin was also less concentrated at cell-cell contacts after exposure to TGFβ1 (Figure S3E) compared to its localization in AEC not exposed to TGFβ1 (Figure 4E). Immunoreactivity for α-SMA co-localized with the GFP reporter in a subset of cells (Figure S3F). In the presence of TGFβ1, the majority of GFP-expressing cells grown on type I collagen expressed α-SMA (Figure S3I and L), indicating TGFβ1 augments effects of collagen on EMT. Mouse AEC grown on fibronectin in the presence of TGFβ1 exhibited similar morphologic changes and alterations in localization of ZO-1 and E-cadherin as seen in mouse AEC grown on type I collagen in the absence of TGFβ1 or laminin-5 in the presence of TGFβ1 (Figure S2).

In the absence of TGFβ1, a minor subset of cells expressing the GFP reporter (<3%) was immunoreactive for α-SMA when cultured on laminin-5 or fibronectin, whereas on type I collagen α-SMA was expressed in ~55% of GFP-labeled cells (Figure 4M). Addition of exogenous TGFβ1 caused ~50%, ~40% and ~80% of GFP-labeled cells to undergo EMT when grown on laminin-5, fibronectin or type I collagen, respectively. These data indicate that monomeric type I collagen induces EMT which can be augmented by addition of TGFβ1. After 8 days in culture, MAECM grown on laminin-5 developed RT >2.0 kΩ·cm2 (Figure 4N), consistent with the presence of a relatively pure epithelial cell population in culture and our previous report of MAECM barrier properties [30]. Monolayers grown on fibronectin attain RT ~50% of that attained on laminin-5, whereas on type I collagen or any of the matrices in the presence of TGFβ1, RT was near zero after 8 days in culture, consistent with observed loss of epithelial phenotype.

Induction of EMT by type I collagen requires signaling via TGFβ type I receptor (Alk5)

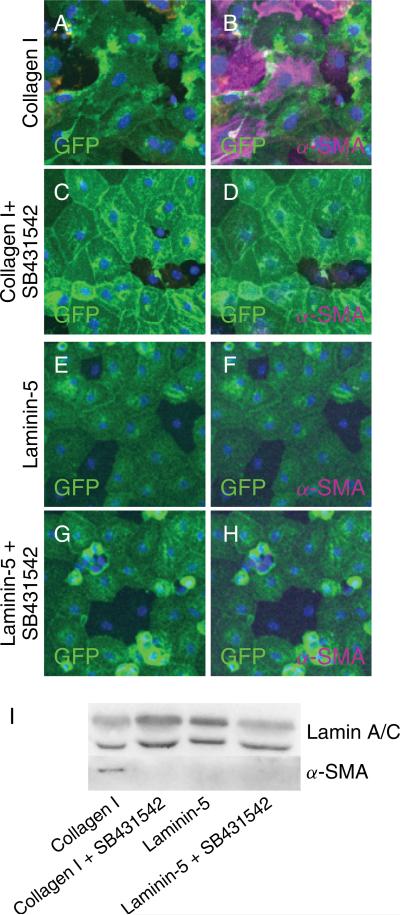

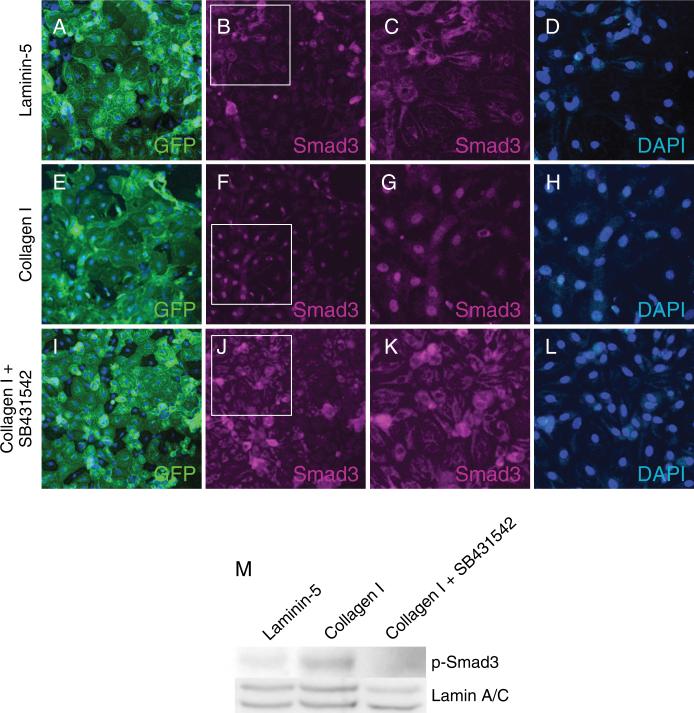

Given the established role of TGFβ as a central mediator of EMT, a potential role for TGFβ signaling in the induction of EMT by type I collagen was further investigated. The Alk5 inhibitor SB431542 blocked collagen-induced expression of α-SMA in GFP-positive cells as shown by immunocytochemistry (Figure 5A–D) and Western blot (Figure 5I). GFP-positive cells showed no expression of α-SMA when grown on laminin-5 with or without the Alk5 inhibitor (Figure 5E-H). Cellular localization of Smad3 was determined in AEC grown on laminin-5 and type I collagen via immunocytochemistry. On day 8 in primary culture, localization of Smad3 was cytoplasmic in MAECM grown on laminin-5 (Figure 6A–D) and nuclear on type I collagen (Figure 6E–H). In MAECM grown on type I collagen, SB431542 prevented nuclear localization (Figure 6I-L) and phosphorylation of Smad3 (Figure 6M), suggesting that induction of EMT by type I collagen requires activation of the canonical TGFβ receptor-Smad pathway and signaling via Alk5.

Figure 5.

TGFβ1 receptor inhibitor SB431542 blocks induction of α-SMA by type I collagen. MAECM grown on type I collagen exhibit irregular and disorganized morphology (A) and a subset of GFP-labeled cells express α-SMA (B; magenta). MAECM grown on type I collagen in the presence of SB431542 (10 μM) displayed cobblestone-like morphology and GFP-labeled cells did not express α-SMA (D), indicating prevention of collagen-induced EMT. GFP-labeled cells grown on laminin-5 with or without SB431542 retain a cobblestone-like morphology (E, G) and showed no immunoreactivity for α-SMA (F, H). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Original magnification x20. I: MAECM were trypsinized off type I collagen- and laminin-5-coated polycarbonate filters and GFP-positive cells were purified by FACS. Lysates of GFP-positive cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with mouse monoclonal anti-α-SMA antibody. Lamin A/C was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Figure 6.

Type I TGFβ receptor inhibitor SB431542 blocks nuclear localization of Smad3 induced by type I collagen. Panels A, E and I show direct detection of GFP in MAECM derived from Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG lungs and grown on laminin-5, type I collagen or type I collagen in presence of SB431542 (10 μM), respectively. Panels B, F and J are the same fields as panels A, E and I immunostained for Smad 3 (magenta). Original magnification x20. Panels C, G and K show magnified views of panels B, F and J, respectively, after cropping and re-sizing using Adobe Photoshop. Panels D, H and L show labeling with DAPI only (blue). These findings indicate that Smad3 nuclear localization by type I collagen is inhibited by SB431542. Western blot (panel M) demonstrates induction of phospho-Smad3 in cells grown on collagen I which is inhibited by SB413542.

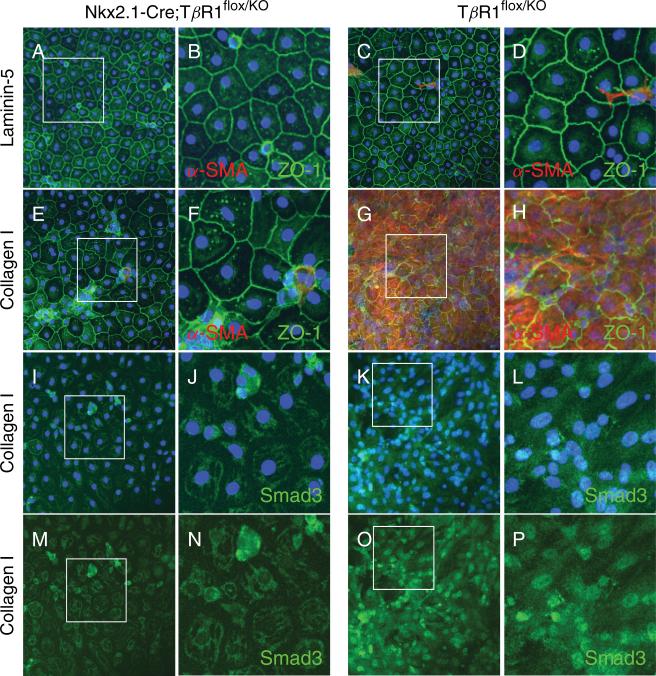

To further validate the role of signaling via the TGFβ receptor complex, AEC deficient for Alk5 from Nkx2.1-Cre;Alk5flox/KO mice or control Alk5flox/KO mice carrying only a heterozygous deletion of exon 3 of the TβRI gene (see [29] and Supporting Information, Figure S4) were plated on filters coated with laminin-5 or type I collagen. After 8 days in culture, monolayers derived from both Alk5-deficient and control mice exhibited ZO-1 reactivity at cell-cell contacts and lacked α-SMA reactivity when grown on laminin-5 (Figure 7A-D). On type I collagen, MAECM derived from Alk5flox/KO control mice expressed α-SMA and showed discontinuous ZO-1 reactivity at cell borders (Figure 7G-H) and nuclear localization of Smad3 (Figure 7K-L and 7O-P), whereas in MAECM deficient for Alk5, expression of α-SMA was absent, localization of ZO-1 was continuous at cell-cell contacts (Figure 7E-F) and localization of Smad3 was cytoplasmic (Figure 7I-J and 7M-N). These results confirm that induction of EMT in AEC by type I collagen requires signaling via Alk5.

Figure 7.

Expression of α-SMA and nuclear localization of Smad3 induced by type I collagen is blocked in MAECM deficient for Alk5. MAECM deficient for Alk5 (A-B) or from control carrying a heterozygous deletion of exon 3 (C-D) exhibited ZO-1 reactivity at the cell-cell contacts and lacked α-SMA reactivity when grown on laminin-5 after 8 days in culture. On type I collagen, MAECM derived from Alk5flox/KO mice expressed α-SMA and discontinuous ZO-1 reactivity at cell borders (G-H) and showed nuclear localization of Smad3 (K-L and O-P; with and without DAPI), whereas in MAECM completely deficient for Alk5 (Nkx2.1-Cre;Alk5flox/KO), expression of α-SMA was absent, localization of ZO-1 was continuous at the cell-cell contacts (E-F), and localization of Smad3 was cytoplasmic (I-J and M-N; with and without DAPI). Original magnification x20. Panels B, D, F, H, J, L, N and P show magnified views of the rectangles shown in panels A, C, E, G, I, K, M, and O, respectively, after cropping and re-sizing using Adobe Photoshop.

Secreted TGFβ ligands are not required for type I collagen-induced EMT in AEC

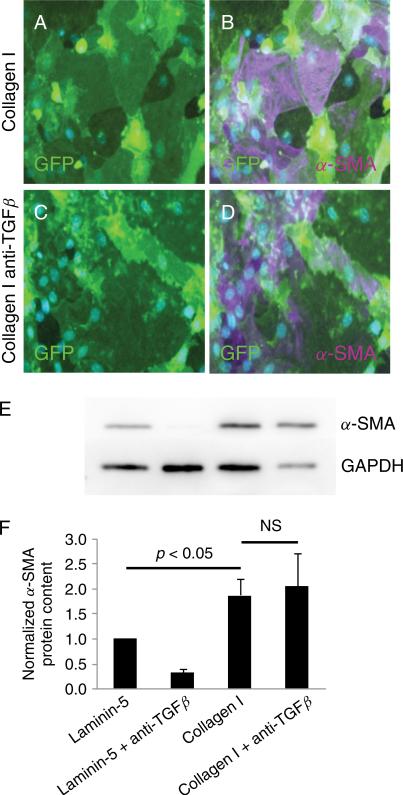

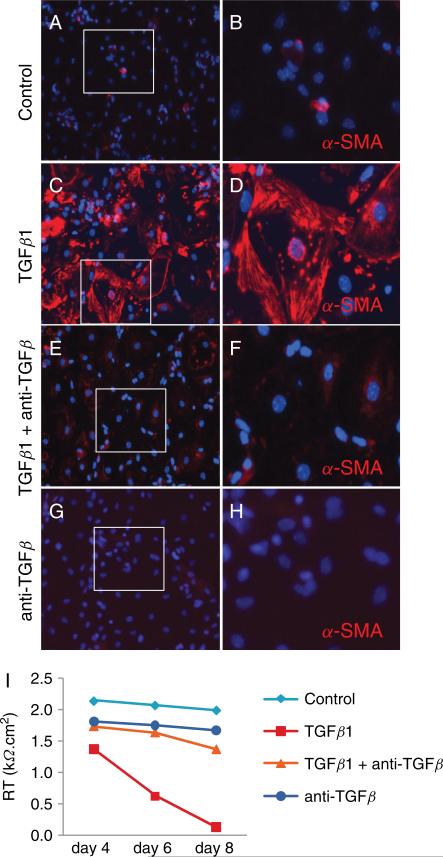

AT2 cells were grown on collagen in the presence or absence of neutralizing antibody against TGFβ (2.5 μg/mL). The pan-specific neutralizing antibody did not inhibit type I collagen-induced expression of α-SMA in GFP-positive cells as shown by immunocytochemistry (Figure 8A–D) and Western blot (Figure 8E-F). Furthermore, Smad3 remained nuclear in the presence of blocking antibody (data not shown). Neutralizing antibody blocked induction of α-SMA (Figure 9A–H) and reduction in RT (Figure 9I) by exogenous TGFβ1 (2.5 ng/mL) in MAECM generated from wild-type mice grown on laminin-5, confirming efficacy of the antibody. In addition, total and active levels of TGFβ1 in culture fluid from MAECM grown on collagen and laminin-5 on days 5–8 post-plating were not significantly different from each other (see Supporting information, Figure S5). Taken together, these data suggest that induction of EMT by type I collagen is likely independent of secreted TGFβ ligand and does not involve autocrine TGFβ production.

Figure 8.

Pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody does not block induction of α-SMA by type I collagen. MAECM grown on type I collagen exhibit irregular and disorganized morphology (A), and a subset of GFP-labeled cells express α-SMA (B; magenta) after 8 days in culture. MAECM grown on type I collagen in the presence of a pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody (2.5 μg/mL) exhibited similar disorganized cell morphology (C) and expression of α-SMA as cells grown on collagen in the absence of neutralizing antibody (D; magenta). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Original magnification x20. E: MAECM treated with and without the pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody were trypsinized from collagen I- and laminin-5-coated polycarbonate filters after 8 days in culture and GFP-positive cells were purified via FACS. Total cell lysates of GFP-positive cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with mouse monoclonal anti-α-SMA antibody. Lamin A/C was used as a loading control. Representative Western blot demonstrates that the increase in α-SMA in cells grown on type I collagen is not prevented by the TGFβ neutralizing antibody. F: Relative densitometric values normalized to α-SMA levels in monolayers grown on laminin-5. Results are an average of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 9.

. Pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody blocked induction of α-SMA by exogenous TGFβ1. Wild-type MAECM grown on laminin-5 in the presence of exogenous TGFβ1 (2.5 ng/mL) expressed α-SMA (C-D; red) after 8 days in culture, whereas in the absence of TGFβ1 (A-B), in the presence of TGFβ1 and the TGFβ neutralizing antibody (E-F), or with TGFβ neutralizing antibody alone (G-H), MAECM have minimal or no α-SMA reactivity. Original magnification x20. Panels B, D, F and H show magnified views of the rectangles shown in panels A, C, E and G, respectively, after cropping and re-sizing using Adobe Photoshop. I: Wild-type MAECM grown on laminin-5 develop RT > 2 kΩ·cm2 on day 4. Representative experiment demonstrates that exogenous TGFβ1 reduced RT to near 0 kΩ·cm2 on day 8; the TGFβ neutralizing antibody blocked the TGFβ1-induced reduction in RT.

Discussion

Evidence suggests a role for EMT in the pathogenesis of IPF by serving as a mechanism for generation of fibroblasts/myofibroblasts, key effector cells in extracellular matrix deposition. Willis and colleagues [35] identified cells co-expressing epithelial and mesenchymal markers in IPF lung, suggesting that AEC might serve as progenitors for (myo)fibroblasts. Fate mapping studies evaluating EMT following instillation of bleomycin or overexpression of active TGFβ1 using different mesenchymal markers and reporter mice have yielded variable results with regard to the contribution of EMT to the myofibroblast population [10, 36]. Kim and colleagues [9, 36] demonstrated in transgenic mouse reporter systems in which AEC permanently expressed β-gal or GFP that, following over-expression of active TGFβ1 and bleomycin instillation, approximately 5% and 10% of reporter-positive cells, respectively, expressed α-SMA and vimentin. Using alveolar epithelial-specific β-gal reporter mice, Tanjore and colleagues [10] reported that ~1/3 of FSP1/S100A4-positive fibroblasts were derived from alveolar epithelium post-bleomycin instillation while α-SMA-expressing myofibroblasts were rarely derived from EMT. Using a novel Nkx2.1-Cre;mT/mG reporter line, we detected approximately equal numbers (~4%) of α-SMA- and vimentin-expressing GFP-positive cells by FACS following intratracheal bleomycin, providing additional evidence supporting the ability of AEC to undergo EMT following injury. The discrepancy between our results and those of Tanjore et al. [10] regarding overall frequency of EMT-derived cells may be due to differences in the mesenchymal marker evaluated as well as difficulties in interpreting β-gal expression using immunohistochemical approaches, although the reasons for a lower number of α-SMA-positive epithelial-derived cells in their study remain uncertain [11]. Given the difficulties with interpretation of β-gal activity in many mammalian tissues and especially lung [38], direct fluorescent reporters such as GFP may be better suited to evaluate EMT in cell fate reporter mice.

Degradation of basement membrane and interstitial matrix is a critical upstream event in initiation of pulmonary fibrosis [15-17]. Tissue remodeling and proteolysis produces monomeric ECM and/or neoepitopes from ECM macromolecules that may act as “soluble” peptides in the pericellular microenvironment [39-42], which may exert effects on epithelial phenotype that differ from those of fibrillar or polymerized ECM as previously shown for fibroblasts [43-46]. Furthermore, integrins α1β1 and α2β1, the two major receptors for collagens, bind more strongly to monomeric collagen than to fibrillar collagen [47]. Our current results showing that mouse AEC grown on monomeric type I collagen undergo EMT, whereas AT2 cells grown on laminin-5 or fibronectin maintain epithelial phenotype, suggest that interstitial collagen, to which cells would be exposed following basement membrane disruption and matrix degradation, plays a causal role in EMT of AEC which may contribute to progression of fibrosis. Investigation of effects of collagen on EMT has almost exclusively been conducted in cancer cell lines in a process that primarily involves interaction with α2β1 integrin [48-49], with limited evidence for collagen-induced EMT in primary cells. Mechanisms implicated in collagen I-induced EMT in malignant cells include integrin-mediated Src activation, inhibition of PTEN [50], integrin-like kinase (ILK)-dependent activation of NF-ĸB and LEF-1 [25] as well as autocrine induction of TGFβ3 signaling [21]. We demonstrate that type I collagen is able to efficiently induce EMT in primary cells, perhaps involving mechanisms distinct from those previously described in malignant cells undergoing EMT. In contrast to the study by Shintani et al. [21], we found that despite activation of TGFβ signaling, observed effects of collagen appear to be independent of autocrine TGFβ induction. Given that the major integrins (i.e., α1β1 and α2β1) engaged by type I collagen are not known to modulate interactions of TGFβ with latency-associated peptide and its activation, these results suggest a novel mechanism whereby induction of EMT by type I collagen involves signaling via Alk5 independent of secretion/activation of TGFβ ligands. Soluble collagen peptides have recently been shown to activate Smad signaling in the absence of native TGFβ ligands through a mechanism involving crosstalk between α2β1 integrin collagen receptors and a membrane signaling complex that includes Alk5, TβRII, integrins α2 and β1, cellular Src and FAK [41, 51]. Results of the current study suggest that a similar mechanism may be implicated in collagen I-induced EMT. We recognize that the possibility that secreted ligand could immediately bind to the autologous receptor in a manner that is not susceptible to neutralization by exogenous antibody has not been completely excluded, requiring further investigation [52].

Our results differ from those reported by Kim and colleagues [36], in which fibronectin was shown to induce EMT in primary AEC in the absence of exogenous TGFβ through integrin αvβ6-dependent activation of latent TGFβ1, but are similar to results of others in which type I collagen but not fibronectin induced EMT in cancer cell lines [21, 26]. These somewhat discrepant findings may be due to differences between model systems. Kim and colleagues [36] plated AT2 cells on chamber slides, a condition in which cells may remain subconfluent without direct cell-cell contact. Based on studies in renal tubular epithelial cells, it is likely that the influence of ECM proteins on AEC phenotype also depends on cell confluence and integrity of cell-cell contacts [53].

Although EMT has now been demonstrated using several different Cre drivers and reporters in at least two mouse models of pulmonary fibrosis [36], and epithelial and mesenchymal markers have been co-localized to a majority of AEC in IPF, the ability of AEC to undergo EMT in vivo remains controversial while the significance of a small number of EMT-derived cells has been questioned. Recent studies have challenged the prevalence of EMT in vivo in other tissues and raised concerns about its significance in chronic fibroproliferative diseases [54, 55]. However, it should be noted that although only a small number of GFP-positive cells of epithelial origin express α-SMA or vimentin after bleomycin injury, the absolute number of EMT-derived fibroblasts may not accurately reflect their overall contribution to the fibrogenic process and it is possible that a minority population of fibroblasts/myofibroblasts derived from EMT stimulates proliferation and activation of resident fibroblasts through aberrant epithelial-fibroblast crosstalk [9]. In addition, the protocol used for isolation of GFP-expressing cells from lungs of injured animals in the current study was similar to that used for isolation of AT2 cells and may been less efficient for isolation of fibroblasts, likely underestimating the number of cells that had undergone complete phenotypic transition. Nevertheless, we recognize that further investigations (including studies to inhibit EMT) are needed to address functional contributions of EMT-derived cells to the fibrotic process. Our results indicate a causal role for monomeric type I collagen in the development of EMT in vitro, implicate degraded ECM proteins as potentially important facilitators of EMT in IPF and support an expanded role for ECM in direct regulation of the TGFβ pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Hastings Foundation, Whittier Foundation and National Institutes of Health grants ES017034 (EDC), ES018782 (EDC), HL038621 (EDC), HL056590 (PM), HL062569 (ZB), HL089445 (ZB) and HL095349 (PM). LD was supported by a Scientist Development Grant 0730280N from the American Heart Association. E. D. Crandall is Hastings Professor and Kenneth T. Norris Jr. Chair of Medicine). Z. Borok is Edgington Chair in Medicine. P. Minoo is Hastings Professor of Pediatrics. We thank Dr. Beiyun Zhou for helpful discussions and Juan Ramon Alvarez for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest are declared.

Author contributions

LD, PF, AB and ZB conceived and designed the experiments. LD, STB, MSK, MD, AB, BZ and YX performed the experiments. LD, PF, CE, PM, BZ, EDC and ZB analyzed the data. LD, EDC and ZB drafted the manuscript.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1776–1784. doi: 10.1172/JCI20530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, et al. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI15518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rastaldi MP, Ferrario F, Giardino L, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition of tubular epithelial cells in human renal biopsies. Kidney Int. 2002;62:137–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeisberg M, Yang C, Martino M, et al. Fibroblasts derive from hepatocytes in liver fibrosis via epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23337–23347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis BC, Borok Z. TGF-beta-induced EMT: mechanisms and implications for fibrotic lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L525–534. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00163.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim KK, Wei Y, Szekeres C, et al. Epithelial cell alpha3beta1 integrin links beta-catenin and Smad signaling to promote myofibroblast formation and pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:213–224. doi: 10.1172/JCI36940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanjore H, Xu XC, Polosukhin VV, et al. Contribution of epithelial-derived fibroblasts to bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:657–665. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0322OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells RG. The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in liver fibrosis: here today, gone tomorrow? Hepatology. 2010;51:737–740. doi: 10.1002/hep.23529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grgic I, Duffield JS, Humphreys BD. The origin of interstitial myofibroblasts in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1772-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yurchenco PD, O'Rear JJ. Basal lamina assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:674–681. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunsmore SE, Rannels DE. Extracellular matrix biology in the lung. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L3–27. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.1.L3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkinson JJ, Senior RM. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in lung remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:12–24. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0166TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pardo A, Selman M, Kaminski N. Approaching the degradome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1141–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuo F, Kaminski N, Eugui E, et al. Gene expression analysis reveals matrilysin as a key regulator of pulmonary fibrosis in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6292–6297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092134099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeisberg M, Maeshima Y, Mosterman B, et al. Renal fibrosis. Extracellular matrix microenvironment regulates migratory behavior of activated tubular epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:2001–2008. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61150-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda Y, Ishizaki M, Kudoh S, et al. Localization of matrix metalloproteinases-1, -2, and -9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 in interstitial lung diseases. Lab Invest. 1998;78:687–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selman M, Ruiz V, Cabrera S, et al. TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. A prevailing nondegradative lung microenvironment? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L562–574. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.3.L562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shintani Y, Maeda M, Chaika N, et al. Collagen I promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer cells via transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:95–104. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0071OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilles C, Polette M, Seiki M, et al. Implication of collagen type I-induced membrane-type 1-matrix metalloproteinase expression and matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation in the metastatic progression of breast carcinoma. Lab Invest. 1997;76:651–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imamichi Y, Konig A, Gress T, et al. Collagen type I-induced Smad-interacting protein 1 expression downregulates E-cadherin in pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2381–2385. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koenig A, Mueller C, Hasel C, et al. Collagen type I induces disruption of E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contacts and promotes proliferation of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4662–4671. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medici D, Nawshad A. Type I collagen promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition through ILK-dependent activation of NF-kappaB and LEF-1. Matrix Biol. 2009;29:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menke A, Philippi C, Vogelmann R, et al. Down-regulation of E-cadherin gene expression by collagen type I and type III in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3508–3517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, et al. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Q, Tam M, Anderson SA. Fate mapping Nkx2.1-lineage cells in the mouse telencephalon. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:16–29. doi: 10.1002/cne.21529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sridurongrit S, Larsson J, Schwartz R, et al. Signaling via the Tgf-beta type I receptor Alk5 in heart development. Dev Biol. 2008;322:208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demaio L, Tseng W, Balverde Z, et al. Characterization of mouse alveolar epithelial cell monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L1051–1058. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00021.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia H, Diebold D, Nho R, et al. Pathological integrin signaling enhances proliferation of primary lung fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1659–1672. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niimi T, Nagashima K, Ward JM, et al. claudin-18, a novel downstream target gene for the T/EBP/NKX2.1 homeodomain transcription factor, encodes lung- and stomach-specific isoforms through alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7380–7390. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7380-7390.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flodby P, Borok Z, Banfalvi A, et al. Directed expression of Cre in alveolar epithelial type 1 cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:173–178. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0226OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swiderski RE, Dencoff JE, Floerchinger CS, et al. Differential expression of extracellular matrix remodeling genes in a murine model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:821–828. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willis BC, Liebler JM, Luby-Phelps K, et al. Induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells by transforming growth factor-beta1: potential role in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1321–1332. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62351-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim KK, Kugler MC, Wolters PJ, et al. Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13180–13185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605669103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svee K, White J, Vaillant P, et al. Acute lung injury fibroblast migration and invasion of a fibrin matrix is mediated by CD44. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1713–1727. doi: 10.1172/JCI118970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell P, Limberis M, Gao G, et al. An optimized protocol for detection of E. coli beta-galactosidase in lung tissue following gene transfer. Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;124:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0793-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atley LM, Mort JS, Lalumiere M, et al. Proteolysis of human bone collagen by cathepsin K: characterization of the cleavage sites generating by cross-linked N-telopeptide neoepitope. Bone. 2000;26:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Downs JT, Lane CL, Nestor NB, et al. Analysis of collagenase-cleavage of type II collagen using a neoepitope ELISA. J Immunol Methods. 2001;247:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garamszegi N, Garamszegi SP, Shehadeh LA, et al. Extracellular matrix-induced gene expression in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:319–329. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otterness IG, Downs JT, Lane C, et al. Detection of collagenase-induced damage of collagen by 9A4, a monoclonal C-terminal neoepitope antibody. Matrix Biol. 1999;18:331–341. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(99)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhudy RW, McPherson JM. Influence of the extracellular matrix on the proliferative response of human skin fibroblasts to serum and purified platelet-derived growth factor. J Cell Physiol. 1988;137:185–191. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041370123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schor SL. Cell proliferation and migration on collagen substrata in vitro. J Cell Sci. 1980;41:159–175. doi: 10.1242/jcs.41.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schuliga MJ, See I, Ong SC, et al. Fibrillar collagen clamps lung mesenchymal cells in a nonproliferative and noncontractile phenotype. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:731–741. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0361OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia H, Nho R, Kleidon J, et al. Polymerized collagen inhibits fibroblast proliferation via a mechanism involving the formation of a beta1 integrin-protein phosphatase 2A-tuberous sclerosis complex 2 complex that suppresses S6K1 activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20350–20360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jokinen J, Dadu E, Nykvist P, et al. Integrin-mediated cell adhesion to type I collagen fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31956–31963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirkland SC. Type I collagen inhibits differentiation and promotes a stem cell-like phenotype in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:320–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valles AM, Boyer B, Tarone G, et al. Alpha 2 beta 1 integrin is required for the collagen and FGF-1 induced cell dispersion in a rat bladder carcinoma cell line. Cell Adhes Commun. 1996;4:187–199. doi: 10.3109/15419069609014222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imamichi Y, Menke A. Signaling pathways involved in collagen-induced disruption of the E-cadherin complex during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;185:180–190. doi: 10.1159/000101319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garamszegi N, Garamszegi SP, Samavarchi-Tehrani P, et al. Extracellular matrix-induced transforming growth factor-beta receptor signaling dynamics. Oncogene. 2010;29:2368–2380. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gharaee-Kermani M, Denholm EM, Phan SH. Costimulation of fibroblast collagen and transforming growth factor beta1 gene expression by monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 via specific receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17779–17784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Masszi A, Fan L, Rosivall L, et al. Integrity of cell-cell contacts is a critical regulator of TGF-beta 1-induced epithelial-to-myofibroblast transition: role for beta-catenin. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1955–1967. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63247-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin SL, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA, et al. Pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are the primary source of collagen-producing cells in obstructive fibrosis of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1617–1627. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scholten D, Osterreicher CH, Scholten A, et al. Genetic labeling does not detect epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of cholangiocytes in liver fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:987–998. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.