Abstract

By comparison of the Proteus mirabilis HI4320 genome with known lipopolysaccharide (LPS) phosphoethanolamine transferases, three putative candidates (PMI3040, PMI3576, and PMI3104) were identified. One of them, eptC (PMI3104) was able to modify the LPS of two defined non-polar core LPS mutants of Klebsiella pneumoniae that we use as surrogate substrates. Mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance showed that eptC directs the incorporation of phosphoethanolamine to the O-6 of l-glycero-d-mano-heptose II. The eptC gene is found in all the P. mirabilis strains analyzed in this study. Putative eptC homologues were found for only two additional genera of the Enterobacteriaceae family, Photobacterium and Providencia. The data obtained in this work supports the role of the eptC (PMI3104) product in the transfer of PEtN to the O-6 of l,d-HepII in P. mirabilis strains.

Keywords: Proteus mirabilis, core lipopolysaccharide, phosphoethanolamine

1. Introduction

Gram-negative motile and frequently swarming bacteria of the genus Proteus from the family Enterobacteriaceae are usually found in soil, water, and the intestines of human and animals. The genus includes five species (P. mirabilis, P. penneri, P. vulgaris, P. myxofaciens, and P. hauseri) and three genomospecies [1]. Among these species, P. mirabilis, P. vulgaris, and P. penneri are the most common opportunistic pathogens [2]. P. mirabilis is frequently associated with urinary tract infections (UTI) in individuals with functional or anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract or long-term catheterized patients. Complications arising from P. mirabilis infections include bladder and kidney stone formation, catheter obstruction by encrusting biofilms, and bacteremia [3]. Identified virulence factors include swarming, fimbriae, urease, hemolysin, and iron acquisition systems. Signature-tagged mutagenesis [4] has allowed the additional identification of an extracellular metalloprotease, several putative DNA binding regulatory, cell-envelope related, and plasmid encoded proteins.

In the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of P. mirabilis, as in other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, three domains can be recognized: lipid A, an endotoxic glycolipid; an O-polysaccharide chain or O-antigen (O-PS); and a core oligosaccharide (OS) domain, linking lipid A and O-PS. The chemical structure of the P. mirabilis lipid A has been determined for one strain showing the presence of a residue of 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose (l-Ara4N) substituting the phosphate at position 1 of lipid A, this l-AraN modification has been related to the high intrinsic P. mirabilis resistance to polymyxin B and related cationic antimicrobial peptides.

Among P. mirabilis and P. vulgaris, 60 O-serogroups have been recognized and the gene clusters involved in the biosynthesis of P. mirabilis serogroups O3, O10, O23, O27, and O47 have been reported [5]. In most P. mirabilis O-serogroups studied so far, the O-PSs contain acidic or both acidic and basic components, such as uronic acids, and their amides with amino acids, including lysine, and phosphate groups (reviewed in [6]).

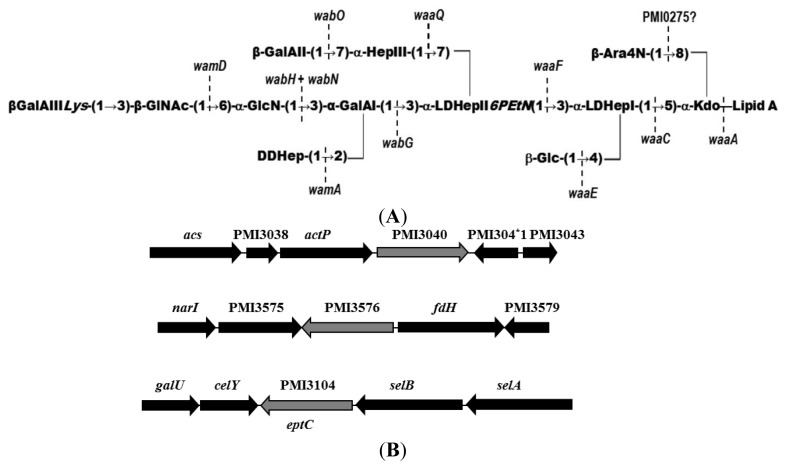

The core OS structure of the P. mirabilis genome strain HI4320 has been recently reported [7] (Figure 1). This structure up to the first outer-core galacturonic acid residue (d-GalA I) is shared by 11 P. mirabilis strains and also by several P. vulgaris and P. penneri serogroups. This common fragment is also found in the core LPS of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Serratia marcescens, but without the Ara4N and phosphoethanolamine (PEtN) residues [8,9] (Figure 1). Some P. mirabilis core-OS structures contain unusual residues such as quinovosamine, an open-chain form of N-acetyl-galatosamine, or amide linked amino acids. Recently, most of the genes involved in the biosynthesis of the sugar backbone of the core LPS from several P. mirabilis strains have been identified and characterized [10,11]. Little is known about the role of the non-sugar charged residues or groups in the core OS. In this study we identify a gene, eptC, essential for core LPS modification with PEtN.

Figure 1.

(A) P. mirabilis HI4320 core OS structure (50) and genes involved in core biosynthesis (2,3). 3-Deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo), l-glycero-d-manno-heptose (l,d-Hep), d-glycero-d-manno-heptose (D,D-Hep), glucosamine (GlcN) galactunonic acid (GalA), N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), glucose (Glc), 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose (l-Ara4N), phosphoethanolamine (PEtN), and lysine (Lys); (B) Location in the genome of strain HI4320 of eptC (PMI3104) and putative PEtN transferases PMI3040 and PMI3576.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Identification of Putative LPS PEtN Transferases

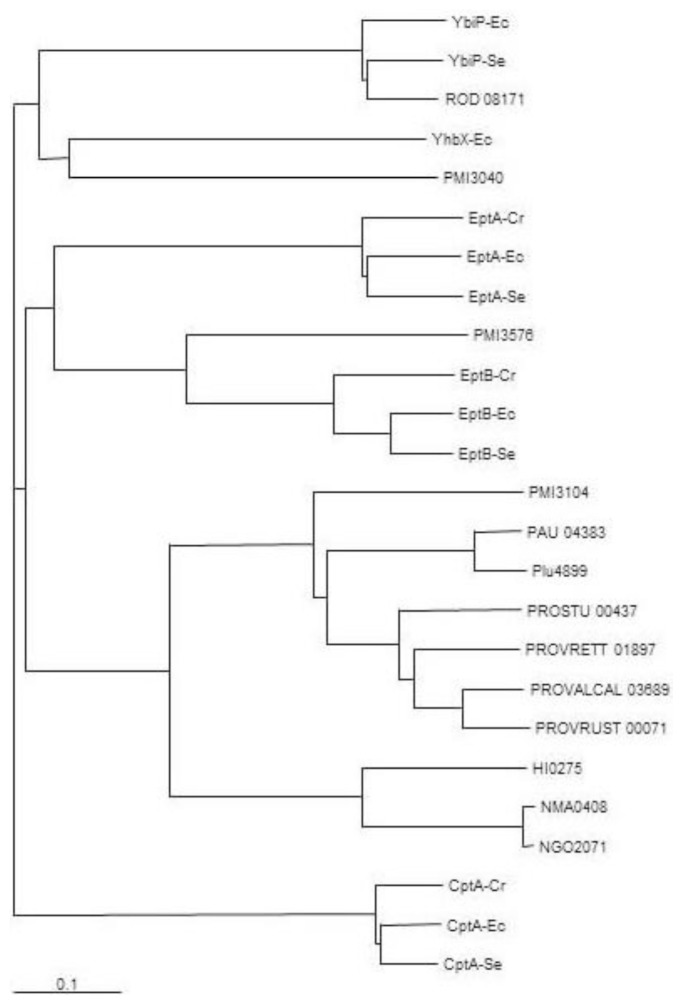

Previous work done in S. enterica LT2 allowed the identification of several LPS PEtN transferases by similarity to lpt-3 gene encoded protein Lpt3 (NMB2010) of Neisseria meningitidis [12]. This protein of N. meningitdis is responsible for the transfer of a PEtN residue to the O-2 of l,d-Hep II [12]. A similar search was performed for P. mirabilis genome strain HI4320 leading to the identification of PMI3040 (e value 1 × 10−19, 28% identity, 48% similarity) and PMI3576 (e value 6 × 10−19, 25% identity, 42% similarity). PMI3040 and PMI3576 shared with other known PEtN transferases the presence of a sulfatase domain. PMI3040 showed significant levels of amino acid identity and similarity to E. coli MG1665 YhbX (e value 1 × 10−84, 33% identity, 52% similarity, 94% coverage), YbiP (e value 3 × 10−37, 30% identity, 48% similarity, 57% coverage) and CptA (e value 6 × 10−27, 23% identity, 43% similarity, 89% coverage) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of selected known and putative PEtN transferases. Shown are proteins from P. mirabilis HI4320 (PMI3040, PMI3576, PMI3104 [eptC]), E. coli MG1655 (YbiP-Ec, YhbX-Ec, CptA-Ec, EptA-Ec, EptB-Ec), S. enterica LT2 (YbiP-Se, CptA-Se, EptA-Se, EptB-Se), Citrobacter rodentium ICC168 (ROD 08171, CptA-Cr, EptA-Cr, EptB-Cr), Photorhabdus asymbiotica asymbiotica ATCC 43949 (PAU 04383), Pho. luminescnes laumondii TT01 (Plu4899), Providencia stuartii ATCC 25827 (PROSTU 00437), Providencia rettgeri DSM 1131 (PROVRETT 01897), Providencia alcalifaciens DSM 30120 (PROVALCAL 03689), Providencia rustigianii DSM 4541 (PROVRUST 00071), Haemophilus influenzae Rd KW20 (HI0275), Neisseria meningitidis Z2491 (NMA0408), and N. gonorrhoeae FA 1090 (NGO2071). Note: The separation and the size of the lanes are relative to the similarity degree according to the program used (the scale bar indicates an evolutionary distance of 0.1 amino acid substitutions per position).

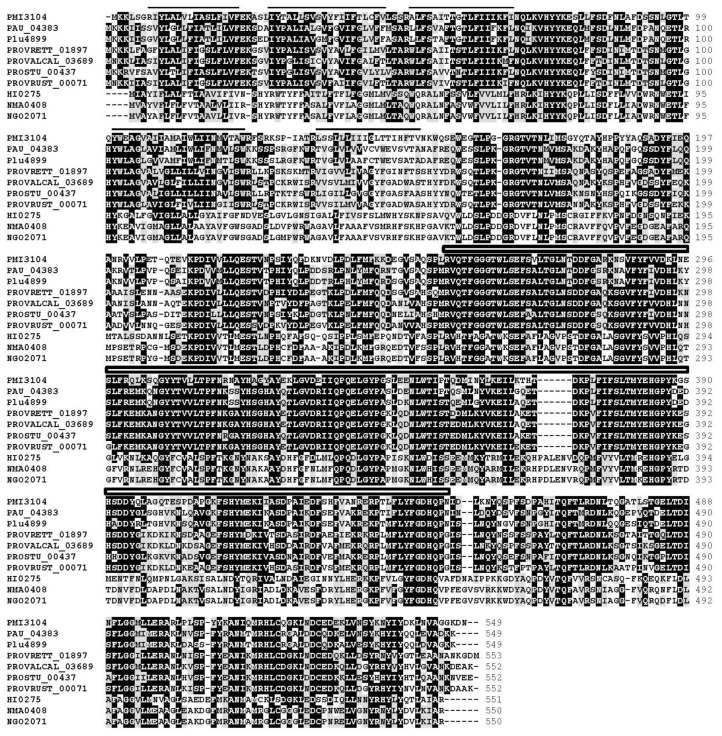

Similar results were found with S. enterica Typhimurium LT2 CptA (STM4118) and YbiP (STM08354) (Figure 2). While no function has been established for YhbX and YbiP, CptA is a PEtN transferase responsible for the linkage of PEtN to phosphorylated l,d-Hep I residue of the inner core in S. enterica [13]. PMI3576 shared significant levels of amino acid identity and similarity to EptB proteins from E. coli MG1665 (e value 0, 51% identity, 70% similarity, 98% coverage) and S. enterica LT2 (e value 0, 50% identity, 71% similarity, 96% coverage), and Citrobacter rodentium ICC168. PMI3576 also showed similarity to EptA proteins from E. coli and S. enterica with e values of 2 × 10−43 and 6 × 10−47, respectively (Figure 2). In E. coli EptB has been shown to transfer a PEtN moiety to the 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic II (Kdo II) residue of inner core LPS [14], and in S. enterica EptA, also known as PmrC, transfers PEtN to the phosphate at the 1 and/or 4′ positions of lipid A [15]. In Neisseria meningitidis, N. gonorrhoeae, and Haemophilus influenza, another PEtN residue is found substituting the O-6 position of l,d-Hep II [12]. A highly conserved Lpt6 protein, N. meningitides (NMA0408), N. gonorrhoeae (NGO2071), and H. influenza (HI0275), is required for the transfer of this PEtN. The whole genome of P. mirabilis HI4320 was analyzed by BLAST search for putative proteins being similar to NMA0408 allowing the identification of PMI3104 (e value 2 × 10−99, 33% identity, 53% similarity). Similar levels of similarity were found for the NMA0408 homologues NGO2071 and HI0275 (Figure 2). The PMI3104 shared with these proteins the presence of several predicted transmembrane regions before a sulfatase domain (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Amino acid alignment among known and putative proteins responsible for the transfer of PEtN to the O-6 of l,d-HepII. P. mirabilis PMI3104 (EptC), Photorhabdus asymbiotica asymbiotica ATCC 43949 (PAU_04383), Pho. luminescnes laumondii TT01 (Plu4899), Providencia rettgeri DSM 1131 (PROVRETT_01897), Prov. alcalifaciens DSM 30120 (PROVALCAL_03689), Prov. stuartii ATCC 25827 (PROSTU_00437), Prov. rustigianii DSM 4541 (PROVRUST_00071), Haemophilus influenzae Rd KW20 (HI0275), Neisseria meningitidis Z2491 (NMA0408), and N. gonorrhoeae FA 1090 (NGO2071). Black lines denote putative transmembrane regions and the box denotes amino acid residues similar to the sulfatase domain in PMI3104 (EptC). Numbers indicated the GenBank protein sequences; Identical amino acids are shown on a black background; and similar residues are shown on a gray background.

PMI3104 showed high levels of identity (75% to 77%) along the entire protein with putative homologues from Photorhabdus asymbiotica, Pho. luminescens, Providencia rettgeri, Prov. alcalifaciens, and Prov. rustigianii (Figures 2 and 3), but not to other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. The three genera containing PMI3104 or its homologues are closely related at the phylogenetic level.

2.2. Identification of a Core LPS PEtN Transferase

Since the core LPS isolated from P. mirabilis strains present a moiety of PEtN substituting the O-6 position of l,d-Hep II (HepII6-PEtN) [6], it was hypothesized that PMI3104 would be the enzyme involved in this PEtN transfer and hence named eptC, for ethanolamine phosphate transferase C. On the basis of carbohydrate backbone composition and structure identity between the core LPS of K. pneumoniae and P. mirabilis up to the first residue of the outer core [9,10] (Figure 1), we decided to use the LPS from non-polar mutants K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabH and K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG [9,16] as surrogate LPS acceptors to test eptC activity. This new approach has the advantage that we look for a positive trait as the addition to the mutant LPS of a particular residue, instead of the mutagenesis studies to determine the function of core LPS biosynthetic genes usually employed. This is only possible, as in our case, if a proper surrogate LPS acceptor is available.

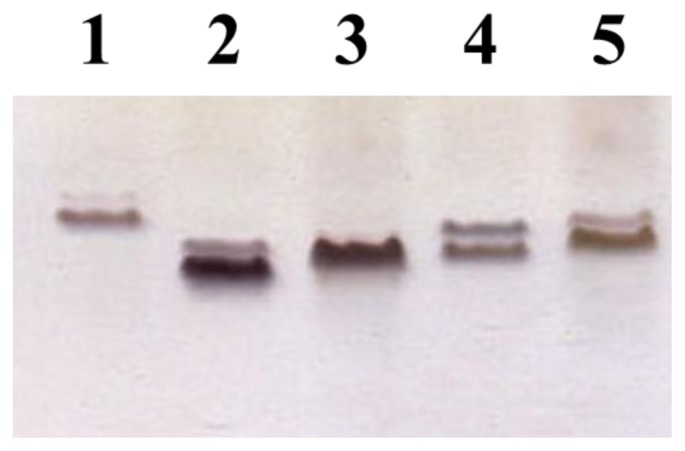

To guarantee the inducible expression of the eptC gene, plasmid pBAD18-Cm-eptC was constructed and electroporated into the two K. pneumoniae mutants 52145ΔwabH [9] and K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG [16]. LPS from K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG (+pBAD18-Cm-eptC grown under arabinose promoter inducing conditions) migration was slower than that of LPS from K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG grown under the same conditions (Figure 4, lanes 2 and 3). Similar results were obtained when comparing LPS from K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabH (+pBAD18-Cm-eptC) and K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabH always grown under arabinose promoter inducing conditions (Figure 4, lanes 4 and 5). No changes were observed in the LPS migration when the cells were grown under non induced conditions.

Figure 4.

LPS electrophoretic pattern in Tricine-SDS-PAGE. LPS samples isolated from K. pneumoniae 52145 wild type (Lane 1), K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG (Lane 2), K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG plus pBAD18-Cm-eptC (Lane 3), K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabH (Lane 4), and K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabH plus pBAD18-Cm-eptC (Lane 5). Samples were obtained from strains grown under inducing conditions.

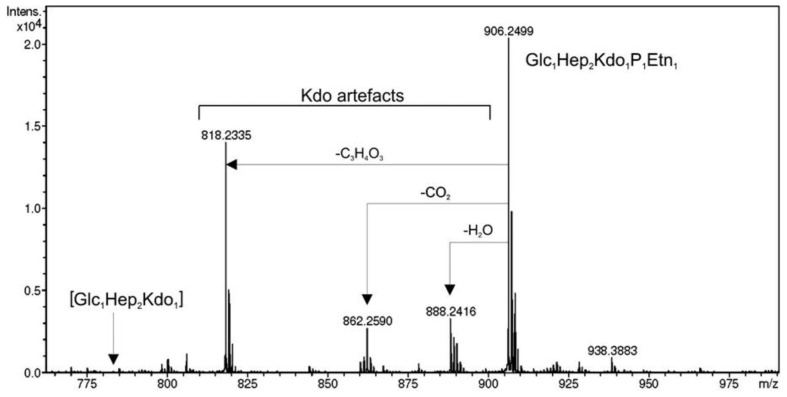

The spectrometry (ESI-MS) spectrum of K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG core oligosaccharide showed a pseudo-molecular ion (M–H)– at m/z 783.37 which was in agreement with the calculated average molecular weight (783.67) of the expected molecular structure, with one hexose, two heptoses and one Kdo unit as previously reported [16]. The identical result was obtained when the core oligosaccharide of K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG (+pBAD18-Cm-eptC) was obtained from cells grown under non-induced conditions. To unambiguously test the eptC requirement for PEtN transfer, LPS from cells of 52145ΔwabG (+pBAD18-Cm-eptC) grown under arabinose promoter inducing conditions was isolated from dried cells by phenol-water extraction and purified (see Experimental Section). Mild acid degradation of this LPS resulted in a core fraction purified by gel-permeation chromatography on Sephadex G-50. High-resolution negative ion electrospray ionization mass spectrum of this fraction showed a major [M–H]− ion peak at m/z 906.2499 for a compound corresponding to an OS composed of two heptose residues and one residue each of hexose, Kdo and PEtN (Hex1Hep2Kdo1P1EtN1) (calculated ion mass 906.2497 amu). In addition, a number of lower-molecular mass ions were observed in the spectrum at m/z 888.2416, 862.2590, and 818.2335 which were assigned to various Kdo artifacts generated by loss of H2O, CO2, and C3H4O3, respectively (Figure 5). No non-phosphorylated OS was detected.

Figure 5.

High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrum of core OS obtained by mild acid hydrolysis from LPS isolated from K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG harboring plasmid pBAD18-Cm-eptC.

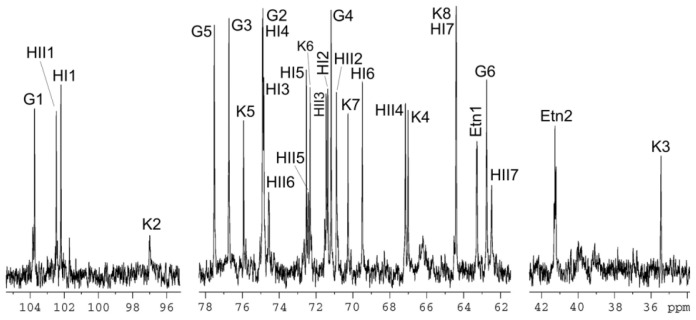

The 13C-NMR spectrum of the OS (Figure 6) showed signals for four anomeric carbons at δ 97.0–103.7, one C–CH2–C group (C-3 of Kdo) at δ 35.4, four HOCH2–C groups (C-6 of Hex, C-7 of Hep, C-8 of Kdo) at δ 62.5–64.4, other sugar carbons in the region of δ 67.0–77.5, and one PEtN group at δ 41.2 (CH2N) and 63.3 (CH2O). The 1H-NMR spectrum contained, inter alia, signals for three anomeric protons at δ 4.55–5.34 and a PEtN group at 3.31 (CH2N). The 31P-NMR spectrum showed one signal for a monophosphate group at δ 0.5.

Figure 6.

13C-NMR of core OS obtained by mild acid hydrolysis from LPS isolated from K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG harboring plasmid pBAD18-Cm-eptC.

The 1H-NMR spectrum of the OS was assigned using two-dimensional COSY and TOCSY experiments, and then the 13C-NMR spectrum was assigned using a two-dimensional 1H-, 13C-HSQC experiment. The assigned 1H- and 13C-NMR chemical shifts (Table 1) were in full agreement with the carbohydrate backbone composition and structure expected for the core OS derived from K. pneumoniae wabG deletion mutant [16]. The signals for H-6 and C-6 of the terminal heptose residue (l,d-Hep II) were shifted downfield to δ 4.57 and 74.6, as compared with their positions in the non-substituted heptose at δ 4.04 and 70.4, respectively.

Table 1.

1H- and 13C-NMR chemical shifts (δ, ppm) of the modified core OS from K. pneumoniae 52145ΔwabG plus pBAD18-Cm-eptC.

| Sugar residue | C-1; H-1 | C-2; H-2 | C-3; H-3 (H-3a,3e) | C-4; H-4 | C-5; H-5 | C-6; H-6 (H-6a,6b) | C-7; H-7 (H-7a,7b) | C-8; H-8 (H-8a,8b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Glcp-(1→ | 103.7; 4.55 | 74.9; 3.32 | 76.7; 3.52 | 71.2; 3.37 | 77.5; 3.47 | 62.7; 3.97, 3.74 | ||

| α-ldHepp6P-(1→ | 102.5; 5.34 | 70.9; 4.15 | 71.5; 3.91 | 67.2; 3.91 | 72.4; 3.79 | 74.6; 4.57 | 62.5; 3.76, 3.85 | |

| →3,4)-α-ldHepp-(1→ | 102.2; 5.08 | 71.4; 4.17 | 74.8; 4.15 | 74.9; 4.26 | 72.5; 4.15 | 69.5; 4.13 | 64.4; 3.72, 3.74 | |

| →5)-α-Kdop | n.f. | 97.0 | 35.4; 2.11, 1.94 | 67.0; 4.12 | 75.9; 4.12 | 72.3; 3.88 | 70.3; 3.70 | 64.4; 3.81, 3.65 |

| NH2CH2CH2O- | 63.3; 4.17 | 41.2; 3.31 |

Assignment was performed using a two-dimensional 1H, 13C-HSQC experiment. n.f., not found. The 31P NMR signal is at δ 0.5.

These data defined the site of phosphorylation at position O-6 of l,d-Hep II and, hence, the OS has the following structure:

2.3. eptC Gene Distribution

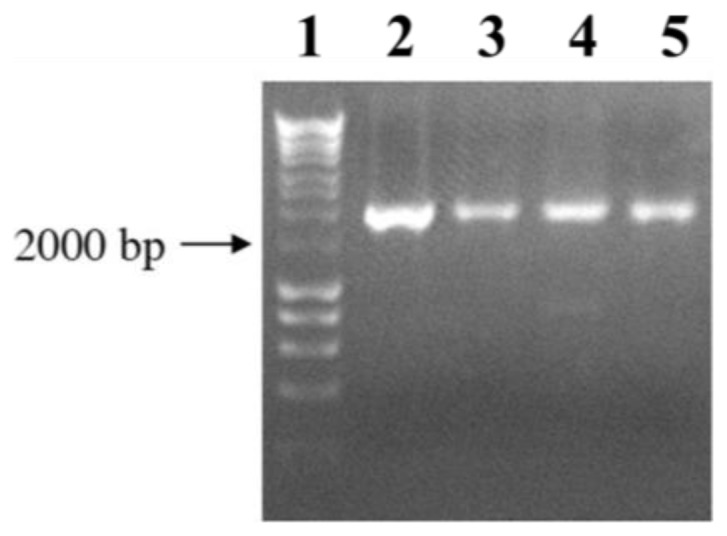

Since the presence of a PEtN moiety linked to the O-6 of the l,d-Hep is a common feature of the core LPS of the studied P. mirabilis strains [17] the eptC gene should be present in these strains. To confirm the above hypothesis, a collection of P. mirabilis strains obtained from Z. Sydorckzyk (National Microbiology Institute, Warsaw, Poland) were used. Genomic DNA from these strains was used as template for amplification with oligonucleotides F1eptC and R1eptC. Fragments of about 2000 bp were amplified for all the strains studied, as exemplified by the results for the four strains shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

PCR amplification using oligonucleotides pair F1eptC-R1eptC and DNA template from P. mirabilis strains R110 (Lane 2), 50/57 (Lane 3), 51/57 (Lane 4), and TG83 (Lane 5). Lane 1, molecular weight standard.

Sequencing of the amplified fragments confirmed the presence of the eptC gene. In addition, in all the amplified fragments the presence of a sequence coding for the C-terminal amino acid residues of celY (PMI3103) gene, encoding a putative cellulase, were found adjacent to eptC, suggesting that in the analyzed strains the eptC location in their genome is the same as that found in genome strain HI4320 (Figure 1). In agreement with the EptC function as the transferase responsible for the linkage of a PEtN moiety to the O-6 position of l,d-Hep II, the eptC gene is found in all the P. mirabilis strains analyzed in this study. Within the Enterobacteriaceae, eptC homologues appear to be limited to species of the Proteus phylogenetic related genus Photobacterium and Providencia (Figure 2), and recently the presence of a PEtN moiety linked to the O-6 position of l,d-Hep II was shown in Prov. alcalifaciens O8 and O35, and Prov. stuartii O49 [18]. Further work will be necessary to understand the reasons for the presence of this common feature in these three closely related genera.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. All strains were routinely grown in in LB medium (per liter, 0.5 g NaCl, 5.0 g yeast extract, 10.0 g tryptone) or on LB agar (15.0 g·L−1 agar). Ampicillin (100 μg·mL−1), chloramphenicol (20 μg·mL−1), and kanamycin (25 μg·mL−1) were added to the different media when required.

Table 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used.

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. mirabilis | ||

| HI4320 | Wild type | H.L.T. Mobley a |

| S1959 | Wild type, serovar O3 | Z. Sydorckzyk |

| R110 | Rough mutant of strain S 1959 | Z. Sydorckzyk b |

| 51/57 | Serovar O28 | Z. Sydorckzyk b |

| 50/57 | Serovar O27 | Z. Sydorckzyk b |

| 14/57 | Serovar O6 | Z. Sydorckzyk b |

| TG83 | Serovar O57 | Z. Sydorckzyk b |

| K. pneumoniae | ||

| 52145ΔwabH | Non-polar wabH mutant | [9] |

| 52145ΔwabG | Non-polar wabG mutant | [16] |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− endA hsdR17 (rk− mk−) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyr-A96 φ80lacZ | [19] |

| Plasmid | ||

| pGEMT easy | PCR generated DNA fragment cloning vector AmpR | Promega c |

| pGEMT-eptC | pGEMT with eptC from strain HI4320, ApR | This study |

| pBAD18-Cm | Arabinose-inducible expression vector, CmR | [20] |

| pBAD18-Cm-eptC | Arabinose-inducible eptC, CmR | This study |

Locations:

University of Michigan, MI, USA;

National Microbiology Institute, Warsaw, Poland;

Barcelona, Spain.

3.2. General DNA Methods

General DNA manipulations were done essentially as previously described [21]. DNA restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, E. coli DNA polymerase (Klenow fragment), and alkaline phosphatase were used as recommended by the Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

3.3. DNA Sequencing and Computer Analysis of Sequence Data

Double-stranded DNA sequencing was performed by using the dideoxy-chain termination method [22] from PCR amplified DNA fragments with the ABI Prism dye terminator cycle sequencing kit (PerkinElmer, Barcelona, Spain). Oligonucleotides used for genomic DNA amplifications and DNA sequencing were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Deduced amino acid sequences were compared with those of DNA translated in all six frames from nonredundant GenBank and EMBL databases by using the BLAST [23] network service at the National Center for Biotechnology Information and the European Biotechnology Information. ClustalW was used for multiple-sequence alignments [24].

3.4. Plasmid Constructions and Mutant Complementation Studies

For complementation studies, the P. mirabilis R110 gene eptC (PMI3104) was PCR amplified by using two specific oligonucleotides F1eptC (5′-TGGCTGGATATGAGCATTCA-3′) and R1eptC (5′-CCAGGTATGATGGCGGTAAG-3′) and chromosomal strain R110 DNA as template, ligated to plasmid pGEMT (Promega), and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Transformants were selected on LB plates containing ampicillin. Once checked, the plasmid with the amplified eptC gene (pGEMT-eptC) was transformed into K. pneumoniae core LPS mutants.

Recombinant plasmid pBAD18-Cm-eptC was obtained by pGEMT-eptC double digestion with SalI and PvuII and subcloning into pBAD18-Cm doubly digested with SalI and SmaI. This construct was transformed into K. pneumoniae core LPS mutants and eptC was expressed from the arabinose-inducible and glucose-repressible pBAD18-Cm promoter [20]. Repression from the araC promoter was achieved by growth in medium containing 0.2% (w/v) d-glucose, and induction was obtained by adding l-arabinose to a final concentration of 0.2% (w/v). The cultures were grown for 18 h at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with chloramphenicol and 0.2% glucose, diluted 1:100 in fresh medium (without glucose), and grown until they reached an A600 of about 0.2. Then, l-arabinose was added, and the cultures were grown for another 8 h. Repressed controls were maintained in glucose-containing medium.

3.5. LPS Isolation and SDS-PAGE

For screening purposes, LPS was obtained after proteinase K digestion of whole cells [25]. LPS samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) or Tricine (N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine)-SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining as previously described [25].

3.6. Large-Scale Isolation and Mild-Acid Degradation of LPS

Dried bacterial cells in 25 mM Tris–HCl buffer containing 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.63 (10 mL·g−1), were treated at 37 °C with RNase and DNase (24 h, 1 mg·g−1 each), and then with proteinase K (36 h, 1 mg·g−1). The suspension was dialyzed and lyophilized, and the LPS was extracted with aqueous phenol [26]. After dialysis of combined water and phenol layers, contaminants were precipitated by adding 50% aqueous CCl3CO2H at 4 °C, the supernatant was dialyzed and lyophilized to give the LPS. A portion of the LPS was degraded with 2% acetic acid for 2 h at 100 °C, a precipitate was removed by centrifugation (13,000× g, 20 min), and the supernatant was fractionated on a column (50 × 2.5 cm) of Sephadex G-50 Superfine in 0.05 M pyridinium acetate buffer (4 mL pyridine and 10 mL acetic acid in 1 L of water) with monitoring using a differential refractometer (Knauer, Berlin, Germany).

3.7. Mass Spectrometry and NMR Studies

High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry was performed in the negative ion mode using a microTOF II instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). A sample of the OS (~50 ng·μL−1) was dissolved in a 1:1 (v/v) water–acetonitrile mixture and sprayed at a flow rate of 3 μL·min−1. Capillary entrance voltage was set to 4.5 kV and exit voltage to −150 V; drying gas temperature was 180 °C.

NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker DRX-500 spectrometer (Bruker Nano GmbH, Berlin, Germany) using standard Bruker software at 30 °C in 99.95% D2O. Prior to the measurements, samples were deuterium-exchanged by freeze-drying twice from 99.9% D2O. A 150-ms duration of MLEV-17 spin-lock was used in two-dimensional TOCSY experiments. Chemical shifts are referenced to internal sodium 3-trimethylsilylpropanoate-2,2,3,3-d4 (δH 0) or acetone (δC 31.45).

4. Conclusions

A phylogenetic tree constructed from an alignment between PMI3040, PMI3576, PMI3104 (eptC), and representative known and putative PEtN transferases allowed us the identification of putative PEtN transferases in a proteomic search of the genome strain. The chemical data obtained in this work (Figures 5 and 6, and Table 1) clearly establish the role of eptC (PMI3104) product in the transfer of PEtN to the O-6 of l,d-Hep II in P. mirabilis strains. The eptC gene is found in all the P. mirabilis strains analyzed in this study. eptC homologues appear to be limited to species of the Proteus phylogenetic related genus Photobacterium and Providencia. The presence of a PEtN moiety linked to the O-6 position of l,d-Hep II has been shown in several Providencia strains.

The other two putative PEtN transferases PMI3576 and PMI3040 need further investigation. PMI3576 appears phylogenetically related to EptB and to a lesser degree to EptA of several Enterobacteriaceae species (Figure 2). EptA, also known as PmrC, transfers a PEtN moiety to the phosphate at the 1 and/or 4′ positions of lipid A [14]. No PEtN substituting lipid A was found in P. mirabilis grown in standard conditions. EptB transfers PEtN to the Kdo II residue of the inner core in E. coli [13], but no such Kdo II modification has been described in P. mirabilis core LPS [6,16]. The presence of a moiety of PEtN linked to Kdo II in minor P. mirabilis core molecules or when these strains are grown in non-standard conditions cannot be ruled out. The above considerations suggest that PMI3576 could be a PEtN transferase more likely involved in Kdo than in lipid A modification. At this time no function can be hypothesized for PMI3040.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Plan Nacional de I + D + i and FIS grants (Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Deporte and Ministerio de Sanidad, Spain), and Generalitat de Catalunya (Centre de Referència en Biotecnologia). EA is predoctoral fellowship from Generalitat de Catalunya and AECI, respectively. We also thank Maite Polo for her technical assistance. We are grateful to Zygmunt Sydorczyk for kindly providing P. mirabilis strains.

Abbreviations

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- OS

oligosaccharide

- O-PS

O-polysaccharide or O-antigen

- PEtN

phosphoethanolamine

- l,d-Hep

l-glycero-d-manno-heptose

- Kdo

3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid or 3-deoxyoctulosonic acid

- l-Ara4N

4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed to experimental data, their analysis, and the writing of the paper.

References

- 1.O’Hara C.M., Brenner F.W., Miller J.M. Classification, identification, and clinical significance of Proteus, Providencia, andMoganella. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000;13:534–546. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.534-546.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rozalski A., Sidorczyk Z., Kotelko K. Potential virulence factors of Proteus bacilli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997;61:65–89. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.65-89.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belas R. Tract Infections: Molecular Pathogenesis and Clinical Management. ASM Press; Washington, DC, USA: 1996. Proteus Mirabilis swarmer cell differentiation and urinary tract infection; pp. 271–298. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Himpsl S.D., Lockatell C.V., Hebel J.R., Jhonson D.E., Mobley H.L.T. Identification of virulence determinants in uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis using signature-tagged mutagenesis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;57:1068–1078. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/002071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Q., Torzewska A., Ruan X., Wang X., Rozalski A., Shao Z., Guo X., Zhou H., Feng L., Wang L. Molecular and genetic analyses of the putative Proteus O antigen gene locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:5471–5478. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02946-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knirel Y.A., Perepelov A.V., Kondakova A.N., Senchenkova S.N., Sydorczyk Z., Rozalsky A., Kaca W. Structure and serology of O-antigens as the basis for classification of Proteus strains. Innate Immun. 2011;17:70–96. doi: 10.1177/1753425909360668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinogradov V. Structure of the core part of the lipopolysaccharide from Proteus mirabilis HI4320. Biochemistry. 2010;76:803–887. doi: 10.1134/S000629791107011X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coderch N., Piqué N., Lindner B., Abitiu N., Merino S., Izquierdo L., Jimenez N., Tomás J.M., Holst O., Regué M. Genetic and structural characterization of the core region of the lipopolysaccharide from Serratia marcescens N28b (serovar O4) J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:978–988. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.978-988.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regué M., Izquierdo L., Fresno S., Piqué N., Corsaro M.M., Naldi T., de Castro C., Waidelich D., Merino S., Tomás J.M. A second outer-core region in Klebsiella pneumoniae lipopolysaccharide. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:4198–4206. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.4198-4206.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aquilini E., Azevedo J., Jimenez N., Bouamama L., Tomás J.M., Regué M. Functional identification of the Proteus mirabilis core lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis genes. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:4413–4424. doi: 10.1128/JB.00494-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aquilini E., Azevedo J., Merino S., Jimenez N., Tomás J.M., Regué M. Three enzymatic steps required for the galactosamine incorporation into core lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:39739–39749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.168385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenzel C.Q., Michael F.S., Stupak J., Li J., Cox A.D., Richards J.C. Functional characterization of Lpt3 and Lpt6, the inner-core lipooligosaccharide phosphoethanolamine transferases fromNeisseria meningitidis. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:208–216. doi: 10.1128/JB.00558-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamayo R., Choudhury B., Septer A., Merighi M., Carlson R., Gunn J.S. Identification of cptA, a PmrA-regulated locus required for phosphoethanolamine modification of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium lipopolysaccharide core. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:3391–3399. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.10.3391-3399.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds C.M., Kalb S.R., Cotter R.J., Raetz C.R.H. A phosphoethanolamine transferase specific for outer 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid residue of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21202–21211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H., Hsu F.F., Turk J., Groisman E.A. The PmrA-regulated pmrC mediates phosphoethanolamine modifications of lipid A and polymyxin resistance inSalmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 2004;146:4124–4133. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4124-4133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izquierdo L., Coderch N., Piqué N., Bedini E., Corsaro M.M., Merino S., Fresno S., Tomás J.M., Regué M. The Klebsiella. pneumoniae wabG gene: Its role in the biosynthesis of the core lipopolysaccharide and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:7213–7221. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.24.7213-7221.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinogradov E., Sidorczyk Z., Knirel Y.A. Structure of the lipopolysaccharide core region of the bacteria of the genus. Proteus. Aust. J. Chem. 2002;55:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondakova A.N., Vinogradov E., Lindner B., Kocharova N.A., Rozalski A., Knirel Y.A. Elucidation of the lipopolysaccharide core structures of bacteria of the genus. Providencia. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2006;25:499–520. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guzman L.M., Belin D., Carson M.J., Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F., Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schäffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hitchcock P.J., Brown T.M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westphal O., Jann K. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide extraction with phenol–water and further application of the procedure. Methods Carbohydr. Chem. 1965;5:83–89. [Google Scholar]