Abstract

Thiopurine drugs are widely used as antileukemic drugs and immunosuppressive agents, and 6-thioguanosine triphosphate (SGTP) is a major metabolite for these drugs. Recent studies have suggested that thiopurine drugs may exert their cytotoxic effects partly through binding of SGTP to a GTP-binding protein, Rac1. However, it remains unclear whether SGTP can also bind to other cellular proteins. Here, we introduced an orthogonal approach, encompassing nucleotide-affinity profiling and nucleotide-binding competition assays, to characterize comprehensively SGTP-binding proteins along with the specific binding sites from the entire human proteome. With the simultaneous use of SGTP and GTP affinity probes, we identified 165 SGTP-binding proteins that are involved in several different biological processes. We also examined the binding selectivities of these proteins toward SGTP and GTP, which allowed for the revelation of the relative binding affinities of the two nucleotides toward the nucleotide-binding motif sequence of proteins. Our results suggest that SGTP mainly targets GTPases, with strong binding affinities observed for multiple heterotrimeric G proteins. We also demonstrated that SGTP binds to several cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), which may perturb the CDK-mediated phosphorylation and cell cycle progression. Together, this represents the first comprehensive characterization of SGTP-binding property for the entire human proteome. We reason that a similar strategy can be generally employed for the future characterization of the interaction of other modified nucleotides with the global proteome.

Thiopurine drugs, including 6-mercaptopurine, 6-thioguanine, and azathioprine, are widely used as cancer therapeutic and immunosuppressive agents.1 Although the exact mechanisms underlying the cytotoxic effects of these thiopurines remain elusive, it is generally accepted that thiopurines are pro-drugs and require metabolic activation to exert their toxicity. After cellular uptake, the thiopurine drugs can be metabolically activated to yield 6-thioguanosine triphosphate (SGTP) and 6-thio-2′-deoxyguanosine triphosphate, which can be incorporated into RNA or DNA.2 In this vein, it was proposed that DNA 6-thioguanine may be spontaneously methylated by (S)-adenosyl-l-methionine to give (S6)-methylthioguanine (S6mG), which directs the misincorporation of dTMP during DNA replication.3 The resulting S6mG:T mispair can trigger the postreplicative mismatch repair (MMR) pathway, thereby inducing cell death.4

The triggering of the MMR pathway may not be the sole mechanism contributing to the cytotoxic effects of the thiopurine drugs considering the fact that the MMR-deficient leukemia cells were also sensitive toward thiopurines.5 In this context, 6-thioguanine was found to reactivate epigenetically silenced genes in leukemia cells by inducing DNMT1 degradation,6 and 6-thioguanine could also induce mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species generation in cultured human cells.7,8 In addition, SGTP, a thiopurine metabolite, was shown to block the activation of Rac1, a GTP-binding protein, in human T lymphocytes, which leads to the inactivation of its target genes such as MEK, NF-κB, and Bcl-xL and the induction of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis.9,10 Considering the involvement of a variety of nucleotide-binding proteins such as protein kinases11 and small GTPases12 in cell signaling, investigation of the interaction of SGTP with cellular nucleotide-binding proteins may unveil the novel mechanisms of action of the thiopurine drugs.

Currently there is no proteome-wide characterization of cellular proteins that can recognize SGTP. Traditional studies on nucleotide–protein interaction often rely on the radioactivity-based ultrafiltration assay13 or the fluorescence-based binding assay.14 These methods are usually costly and time-consuming because they require the use of purified proteins. Moreover, none of these approaches permit the robust discovery of a nucleotide-binding site, or “nucleotide-interacting residues”, in proteins. Recently, we developed a quantitative affinity profiling strategy, encompassing the use of low and high concentrations of desthiobiotin-conjugated acyl ATP probes, to comprehensively characterize ATP–protein interactions at the entire proteome scale.15 The method allows for the minimization of false-positive identification of ATP-binding targets arising from nonspecific labeling and facilitates the identification of previously unrecognized ATP-binding sites in ATP-binding proteins.

Here, we devised a quantitative profiling strategy with the use of a SGTP-affinity probe to unambiguously discover novel SGTP-binding proteins along with the specific binding sites from the entire human proteome. Additionally, we characterized the binding selectivities of these proteins toward SGTP and GTP. Many known GTP-binding proteins, including multiple heterotrimeric G proteins, exhibit a strong binding preference toward SGTP. We also observed that SGTP displays robust binding toward multiple cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), which may perturb the CDK-mediated phosphorylation and cell cycle progression.

Experimental Procedures

Synthesis of 6-Thioguanosine Triphosphate

All reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise indicated. 6-Thioguanosine was phosphorylated to give the corresponding 5′-monophosphate following published procedures.16 A reaction mixture containing 6-thioguanosine-5′-monophosphate (225 mg, 0.6 mmol), triphenylphosphine (0.396 g, 1.5 mmol), diphenyl thioether (0.33 g, 1.5 mmol), and l-methylimidazole (0.5 mL, 6.2 mmol) in DMF/DMSO (1:2, 10 mL) was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. To the resulting solution was subsequently added 0.5 M bis(tri-n-butylammonium) pyrophosphate in DMF (1.5 mmol, 3.0 mL).17 The solution mixture was incubated at room temperature for 50 min, and the product was precipitated by the addition of acetone (100 mL). The precipitate was washed twice with acetone (20 mL each). The product was subsequently purified by using an anion exchange column packed with DEAE Sephadex G-25, and the SGTP was eluted with 200 mM NH4HCO3. Fractions were pooled, lyophilized, dissolved in water, and lyophilized again to give SGTP as a white solid (54 mg, yield 17%). 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz): δ 8.13 (s, 1H), 5.82 (s, 1H), 4.65 (s, 1H), 4.51–4.46 (m, 1H), 4.23 (brs, 1H), 4.12–4.08 (m, 2H). 31P NMR (D2O, 80 MHz): δ −8.5, −10.2, −21.7.

Cell Lysate Preparation and Labeling with the Nucleotide Affinity Probe

The desthiobiotinylated SGTP and GTP affinity probes (Figure 1) were prepared following previously published procedures15,18 with minor modifications (see Supporting Information). The nucleotide affinity probes are not highly stable at room temperature; thus, the probes were stored at −80 °C until use, and, prior to the binding and labeling experiment, the integrities of the probes were always analyzed by ESI-MS to ensure that there is no evident degradation. For stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) experiments, lysine/arginine-depleted RPMI-1640 medium (Pierce) was supplemented with light or heavy ([13C6,15N2]-l-lysine and [13C6]-l-arginine) lysine and arginine, along with dialyzed FBS (Invitrogen) and penicillin (100 IU/mL) to give the complete SILAC medium. The Jurkat-T acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (ATCC; Manassas, VA) were cultured in heavy RPMI-1640 SILAC medium for at least five cell doublings to achieve complete isotope incorporation. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Approximately 2 × 107 cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS for three times, and lysed in a 1 mL lysis buffer, which contained 0.7% CHAPS, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 μL (1:100) protease inhibitor cocktail on ice for 30 min. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 16 000g at 4 °C for 30 min, and the resulting supernatants were collected and subjected to gel filtration separation using NAP-25 columns (Amersham Biosciences) to remove free endogenous nucleotides. Cell lysates were eluted into a 2 mL buffer, containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 75 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol. Most endogenous nucleotides should be removed with this approach, though we cannot exclude the possibility that the tightly bound nucleotides from some GTP-binding proteins are not removed with this approach, which may limit their binding toward the GTP or SGTP affinity probe. The resulting proteins in cell lysates were quantified using Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and stored at −80 °C. Immediately prior to the labeling reaction, MgCl2, MnCl2, and CaCl2 were added to the concentrated cell lysate until their final concentrations reached 50, 5, and 5 mM, respectively. It is worth noting that divalent metal ions (e.g., Mg2+) are often important in protein-GTP binding;19 thus, divalent metal ions were added to assist the binding of nucleotide affinity probes to nucleotide-binding proteins. Approximately 1 mg of cell lysate was treated with 10 or 100 μM desthiobiotin-SGTP or -GTP affinity probe. Labeling reactions were carried out at room temperature with gentle shaking for 1.5 h. After the reaction, the remaining probes in the cell lysates were removed by buffer exchange with 25 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5) using Amicon Ultra-4 filter (10 000 NMWL, Millipore).

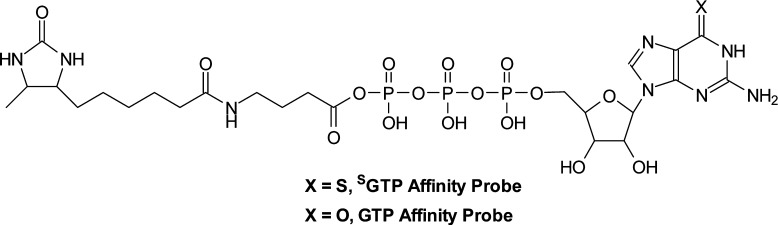

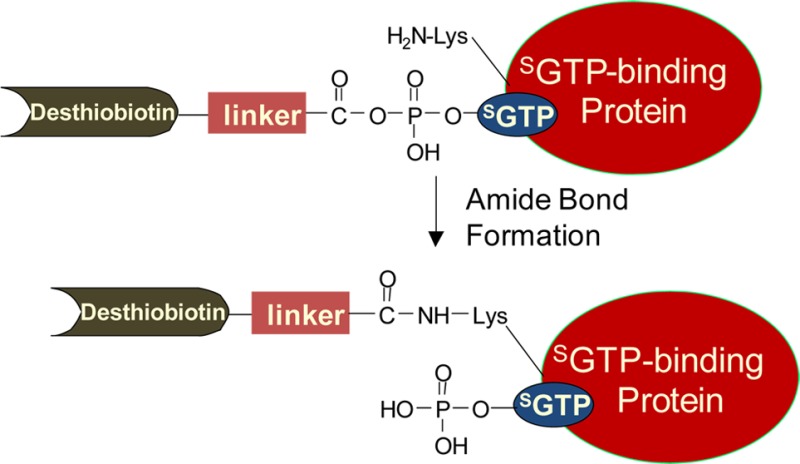

Figure 1.

Structures of the SGTP and GTP affinity probes.

In-Solution Enzymatic Digestion and Affinity Purification

After addition of 8 M urea for protein denaturation, as well as dithiothreitol and iodoacetamide for cysteine reduction and alkylation, the labeled proteins were digested with modified sequencing-grade trypsin (Roche Applied Science) at an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:100 in 25 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5) at 37 °C for overnight. The peptide mixture was subsequently dried in a Speed-vac and redissolved in 1 mL of 100 mM potassium phosphate and 0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.5, PBS buffer), to which solution was subsequently added 200 μL of avidin-agarose resin (Sigma-Aldrich). The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 1 h with gentle shaking. The agarose resin was then washed with 3 mL of PBS and 3 mL of H2O to remove unbound peptides, and the labeled peptides were subsequently eluted with 1% TFA in CH3CN/H2O (7:3, v/v) at 65 °C. The eluates were dried in a Speed-vac and stored at −20 °C prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. The detailed conditions for LC-MS/MS and in vitro kinase activity assay, and database search parameters are described in the online Supporting Information.

Results

Strategy for Proteome-Wide Characterization of SGTP–Protein Interactions

Here, we extended the use of biotin-labeled nucleotide affinity probes as acylating agents to selectively label and enrich SGTP-binding proteins from the entire human proteome. Similar to the previously reported ATP or GTP affinity probes,18 the SGTP affinity probe harbors a binding moiety (SGTP) and an enrichment moiety (i.e., desthiobiotin) that are conjugated through an acyl phosphate linkage (Figure 1). Upon binding to proteins, the acyl phosphate component of the affinity probe reacts with the ε-amino group of the specific lysine residue at the nucleotide-binding site to yield a stable amide bond, which results in the covalent attachment of desthiobiotin to the lysine residue on SGTP-binding proteins (Figure S1A). In this vein, it is of note that the presence of the desthiobiotin moiety on the γ phosphate is not expected to affect the binding of the probe to nucleotide-binding proteins, viewing that γ phosphate generally interacts with hydrophilic, solvent-exposable regions of the nucleotide-binding proteins.19

Owing to its relatively high reactivity, lysine residues not involved in nucleotide binding may also be modified by the nucleotide affinity probe via nonspecific electrostatic interactions. To distinguish specific from nonspecific labeling, we applied a nucleotide affinity profiling strategy developed previously in our lab15 utilizing high and low concentrations of SGTP affinity probe, along with SILAC-based quantitative proteomics platform,20 to unambiguously characterize SGTP-binding affinities of proteins at the entire proteome scale. Along this line, the binding of the SGTP component of the probe to a protein promotes the acyl phosphate moiety to couple with the lysine residue at the nucleotide binding site.21 Therefore, lysine residues involved with SGTP binding and those that are not would exhibit distinct labeling behaviors with low and high concentrations of the SGTP affinity probe. At low probe concentration (10 μM), the former lysine residues possess high reactivity and are completely labeled and the latter are partially labeled because of the limited amount of labeling reagent present; however, at high probe concentration (100 μM), both types of lysines are labeled to almost completion. These two probe concentrations were chosen on the basis of our previous study with the use of GTP affinity probe, where we observed a 4-fold reduction in the identification of the number of GTP-binding proteins when the concentration of the GTP probe was decreased from 100 to 15 μM.18 In addition, a relatively large percentage of the probe-labeled peptides were derived from nonspecific proteins when the probe concentration was at 100 μM.18 Thus, we selected 10 and 100 μM probe concentrations for the nucleotide affinity profiling experiment to optimize the sensitivity and selectivity for the identification of SGTP-binding proteins.

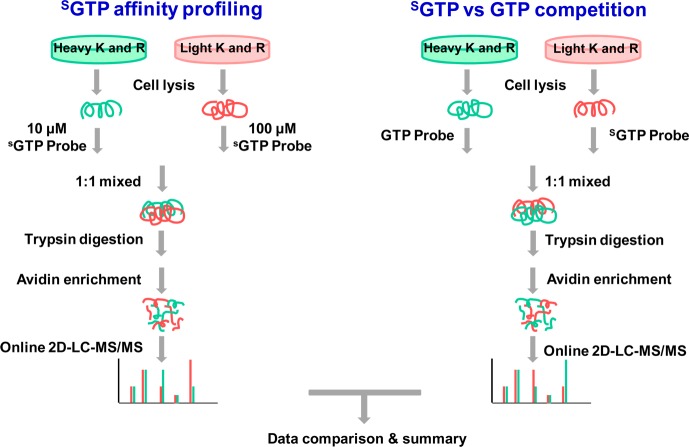

After labeling the light and heavy SILAC cell lysates with 10 and 100 μM of the probe, respectively (forward SILAC, and the labeling experiment was also carried out in an opposite way in reverse SILAC, Figure 2), we combined the two protein samples, digested the protein mixture with trypsin, enriched the resulting desthiobiotin-labeled peptides with avidin agarose, and subjected the enriched peptides to LC-MS/MS analyses. The peak intensity ratios of desthiobiotin-labeled light and heavy peptides were then employed to derive SGTP-binding affinity ratio, RSGTP10/1, for specific lysine residues in individual proteins (Figure 2), where specific SGTP-binding lysine will display an RSGTP10/1 close to 1, because a similar amount of SGTP-binding lysine will be labeled regardless of the probe concentration. By contrast, nonspecifically labeled lysine will show a concentration-dependent increase in SGTP probe labeling, which will yield an RSGTP10/1 ≫1. It is of note that owing to the aforementioned practical limitation about probe concentrations which can be used (10 and 100 μM), we cannot formally exclude the possibility that some highly abundant SGTP-binding proteins may still exhibit large ratios of RSGTP10/1, thereby resulting in their false-negative identification.

Figure 2.

Comprehensive characterization of SGTP-binding proteins by orthogonal quantitative SGTP-affinity profiling assay and SGTP/GTP competition assay.

Although the above-proposed SGTP affinity profiling assay is effective in identifying specific SGTP-binding proteins, it provides little information about the binding selectivities of these proteins toward SGTP versus other endogenous nucleotides (i.e., ATP and GTP). To address this, we also employed SILAC together with our SGTP and GTP affinity probes to compare directly the SGTP- and GTP-binding affinities of proteins at the entire proteome scale. In this experiment, light- and heavy-labeled cell lysates were treated with 100 μM each of desthiobiotin-based SGTP and GTP probes, respectively, and, to minimize the bias introduced by SILAC, we also conducted the labeling experiments in the opposite way (i.e., reverse SILAC experiment). After the reaction, light- and heavy-labeled cell lysates were mixed prior to any further steps of sample manipulation as described above. Peak intensity ratios of light and heavy desthiobiotin-labeled tryptic peptides were subsequently used to derive SGTP/GTP binding affinity ratio, RSGTP/GTP, which reflects the relative binding affinities of SGTP and GTP toward specific lysine residues in proteins of interest.

Proteome-Wide Profiling of SGTP-Binding Proteins

Our quantitative SGTP-affinity profiling of whole cell lysate from Jurkat-T cells led to the quantification of a total of 1925 proteins, which include more than 5400 light or heavy desthiobiotin-modified lysine residues. As depicted in Figure 3A, a large number of peptides with desthiobiotin modification exhibited significantly different probe labeling efficiency when 10 and 100 μM of probe were employed for the labeling reactions, with RSGTP10/1 ≫ 1. However, a small portion of the desthiobiotin-modified peptides bear RSGTP10/1 close to 1, indicating that they possess comparable labeling efficiency at low and high probe concentrations. Similar to the previous quantitative affinity profiling assays for ATP-binding proteins15 and reactive cysteine-containing proteins,22 we arbitrarily consider lysine residue in peptides with RSGTP10/1 < 2 as SGTP-binding lysine. With this threshold, the identified SGTP-binding proteins are at least 5-fold more selective toward binding the modified nucleotide than those proteins that were labeled via nonspecific binding. In addition, only those modified lysine residues that were successfully quantified at least twice are retained on the list. With these criteria, we obtained 199 unique desthiobiotin-modified peptides, representing approximately 4% of total identified peptides, from 165 unique proteins. We considered these 165 proteins as SGTP-binding proteins (Table S1).

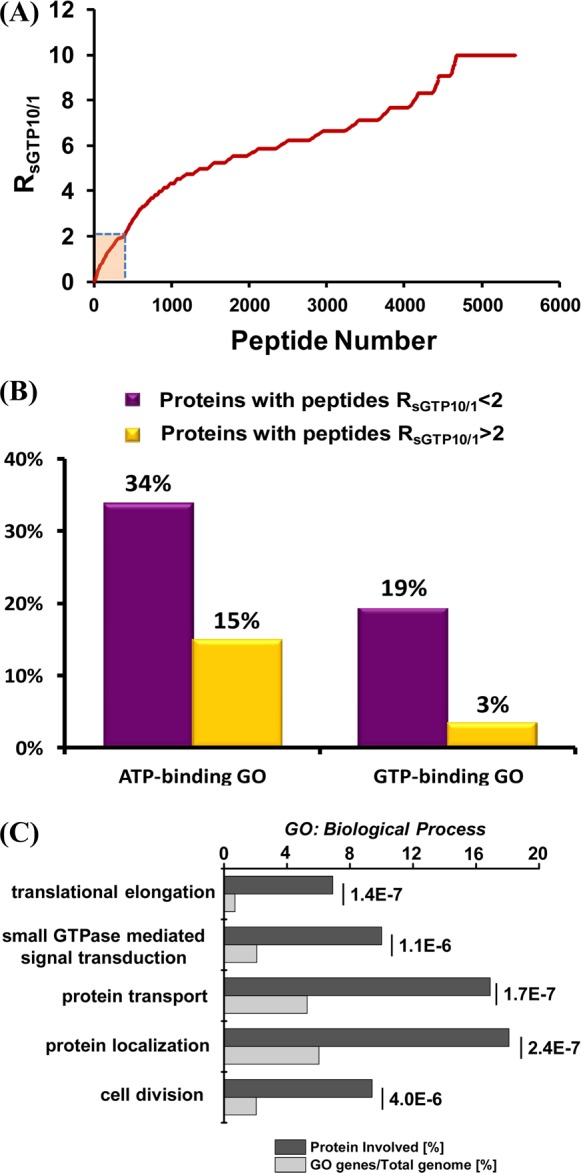

Figure 3.

(A) Measured RSGTP10/1 ratio from Jurkat-T cell lysates with low (10 μM) and high (100 μM) concentrations of SGTP probe in SGTP-affinity profiling assay. (B) Molecular function GO analysis for proteins with different RSGTP10/1 ratios using Jurkat-T cell lysates. (C) Biological process GO analysis for targeted SGTP-binding proteins.

Owing to the structural similarity of SGTP and GTP, the SGTP affinity probe may also bind to and conjugate with GTP-binding proteins. We surveyed the 165 identified SGTP-binding targets for their functional characteristics using DAVID,23 which revealed that 19% of the 165 proteins are with the known GTP-binding gene ontology (GO), suggesting an 8.4-fold enrichment relative to the entire human proteome with a p-value of 8.1 × 10–20 (Figure 3B and Table S2). In contrast, the percentage of known GTP-binding proteins in the protein group containing peptides with RSGTP10/1 > 2 is only 3%. More significantly, among the 199 peptides from the candidate SGTP-binding protein group, peptides from known GTP-binding proteins were on average identified and quantified 2–3 times more frequently than those from proteins lacking GTP-binding GO, suggesting an even more pronounced GTP-binding enrichment efficiency (44% of all quantification events, Table S1). Additionally, we found that 56 out of 165 (34%) identified SGTP-binding proteins are known ATP-binding proteins, indicating a 3.4-fold enrichment relative to the entire human proteome with a p-value of 1.5 × 10–15. However, in contrast to the GTP-binding protein group, a large percentage of known ATP-binding proteins with desthiobiotin labeling identified in our profiling experiment were excluded from SGTP-binding protein groups (Figure 3B and Table S2). Only 18% (56 out of a total of 318) of the identified known ATP-binding proteins are SGTP-binding proteins, suggesting the necessity in revealing nonspecific probe labeling arising from electrostatic interaction based on the RSGTP10/1 ratio. Thus, SGTP targets a wide array of known GTP- and ATP-binding proteins.

GO analysis also unveiled a strong enrichment of multiple GTP-related pathways including translational elongation, protein transport and localization, and small GTPase-mediated signal transduction (Figure 3C). This is in keeping with the over-representation of GTP-binding GO of SGTP-binding targets, suggesting that SGTP may interfere significantly with the GTP-related cell function. For example, GTP serves as an important cofactor for elongation factors 1 and 2 to regulate the GTP hydrolysis-dependent translocation of peptidyl-tRNA during translation elongation.24 Our results showed that SGTP binds to elongation factors 1-alpha, 1-alpha2, and 2, which may affect the GTP-related regulatory mechanism of protein synthesis. Interestingly, we also observed the over-representation of “cell cycle” process (Figure 3C), where more than 20 proteins involved in this process, including multiple CDKs, were found to be SGTP-binding proteins. These results offer a wealth of information for the further examination of SGTP–protein interaction and the mechanism of action of thiopurine drugs.

Competitive Binding of SGTP/GTP to Known GTPases

As mentioned above, our nucleotide affinity profiling strategy differs from other nucleotide-binding assays by virtue of its capability in site-specific differentiation of nucleotide binding. Benefited from this high-throughput, proteome-wide quantitative analysis, we sought to analyze the sequence context surrounding the desthiobiotin-modified lysine, which is considered as the SGTP-binding site in proteins. In this regard, we included all the desthiobiotin-labeled peptides with RSGTP10/1 ratios being smaller than 2 for motif search using motif-X.25 This led to the discovery of the well-known P-loop sequence motif of GxxxxGKS,26 with a 91-fold enrichment relative to the occurrence frequency of this motif in the entire proteome (Figure 4A). This finding suggests that SGTP directly competes with GTP in binding toward protein targets at exactly the same nucleotide-binding site at the P-loop region. Therefore, our SGTP affinity profiling assay and SGTP/GTP competition assay could allow for site-specific determination of the SGTP binding affinity and selectivity toward the unique P-loop motif sequence, which is known to be directly involved in GTP-binding for these GTPases. On the basis of the results from SGTP affinity profiling assay and SGTP/GTP competition assay, we constructed a heatmap to better visualize the SGTP binding affinity and selectivity for 34 quantified GTPases toward the unique P-loop binding motif (Figure 4B). The heatmap showed that the GxxxxGKS motif in most known GTP-binding proteins, including small GTPases, heterotrimeric G proteins, and several other GTP-binding proteins (i.e., elongation factor 1-alpha 2, GTP-binding proteins 1 and 2), exhibited significant binding preference toward SGTP.

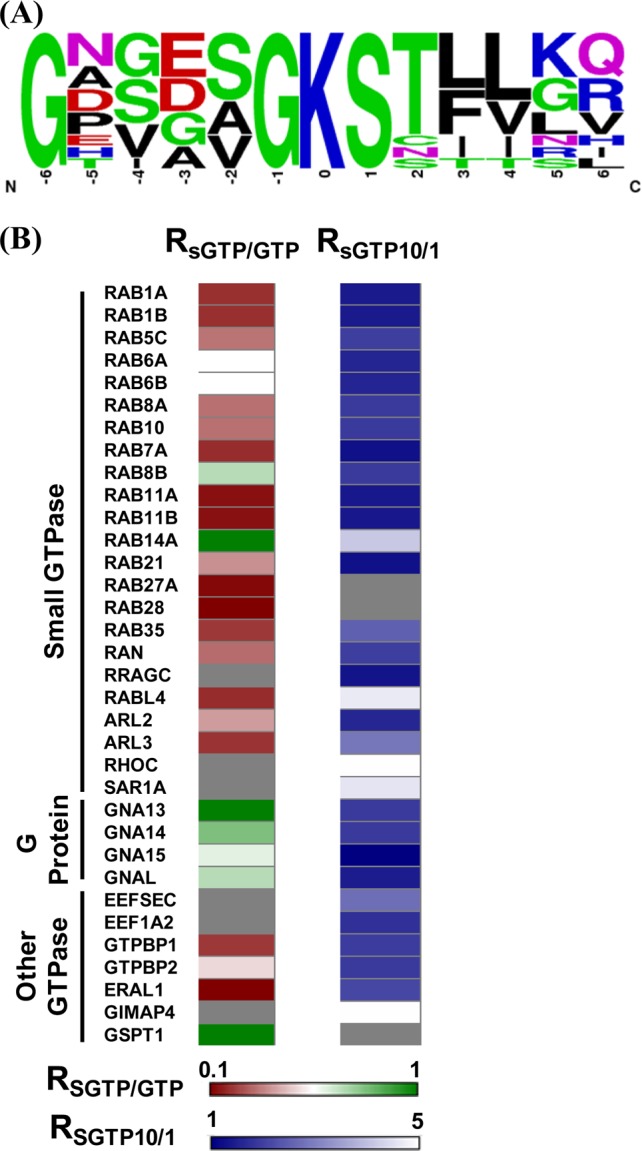

Figure 4.

(A) Unique binding motifs found for the identified SGTP-binding proteins in the SGTP affinity profiling experiment. (B) A heatmap displaying the SGTP-binding affinity and SGTP/GTP binding selectivity toward GxxxxGKS binding motif of known GTPases. For the SGTP affinity profiling heatmap, dark blue and white designate high SGTP-binding affinity with small RSGTP10/1 ratios and low SGTP-binding affinity with large RSGTP10/1 ratios, respectively; for the SGTP/GTP competition binding heatmap, dark red and dark green indicate significant GTP-binding preference with low RSGTP/GTP ratio and similar SGTP/GTP-binding preference (i.e., with RSGTP/GTP ratio close to unity), respectively (see scale bar below the heatmap). Gray represents those GTPases that were not quantified.

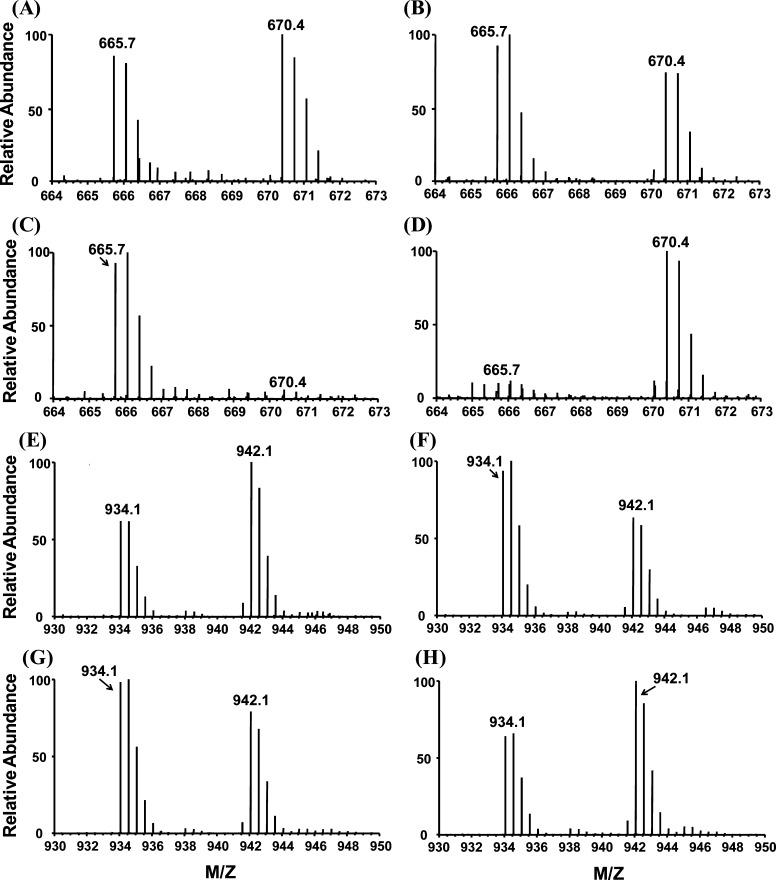

Small GTPases are structurally classified into at least five families, namely, the Ras, Rho, Rab, Sar1/Arf, and Ran families.12 Like other G proteins, small GTPases exist in the interconvertible GDP-bound inactive and GTP-bound active forms. The regulation of the activity of small GTPases plays vital roles in cell signaling, and loss of such regulation is believed to be closely associated with the development of various types of cancer.27 Our results led to the quantification of most small GTPases, including 14 Rab proteins, with their GxxxxGKS motif displaying significant binding preference toward SGTP. For instance, the desthiobiotin-labeled peptide from the P-loop motif of Rab11b, namely, VVLIGDSGVGK24#SNLLSR, was detected in our SGTP affinity profiling experiment with a significant SGTP binding affinity (RSGTP10/1 ratio = 1.39, Figure 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Light- and heavy-labeled peptides of selective GTPases from forward and reverse SGTP-affinity profiling and SGTP/GTP competition binding experiments. (A, B) Peptide VVLIGDSGVGK24#SNLLSR with a low RSGTP10/1 ratio from Rab-11B; (C, D) Peptide VVLIGDSGVGK24#SNLLSR with a low RSGTP/GTP ratio from Rab-11B; (E, F) Peptide LLLLGAGESGK55#STIVK with a low RSGTP10/1 ratio from guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(olf) subunit alpha (GNAL). (G, H) Peptide LLLLGAGESGK55#STIVK with a RSGTP/GTP ratio close to unity from GNAL. “#” indicates the desthiobiotin-labeling site.

It is worth noting that several small GTPases (i.e., Ras-related protein Rab-14, RAS oncogene-family-like 4, Rho-related GTP-binding protein RhoC, and GTP-binding protein SAR1a) displayed low SGTP binding affinity. Although P-loop motif sequence from these small GTPases can still be labeled with the SGTP probe, relatively large RSGTP10/1 ratios were observed for these peptides, suggesting their low binding affinity toward SGTP. Moreover, our SGTP/GTP competition assay revealed that small GTPase-related pathways may not be the major targets for SGTP. As shown in Figure 4B, most small GTPases exhibit stronger binding to GTP than SGTP. This result suggests that, owing to the competition from binding to endogenous GTP, SGTP may not affect substantially the small GTPase-related cell function in vivo. This finding is reminiscent of a previous observation that, although SGTP is capable of binding to eight small GTPases like Ran protein, much higher concentrations of SGTP were required to displace the bound GTP from these small GTPases.10

Four heterotrimeric G proteins display significant binding affinity toward SGTP (Figure 5). For instance, one desthiobiotin-labeled peptide with a P-loop motif from guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(olf) subunit alpha (GNAL) (i.e., LLLLGAGESGK55#STIVK) was successfully quantified in both forward and reverse SGTP affinity profiling assay, where K55 consistently displays a low RSGTP10/1 of 1.46 (Figure 5E,F). This result suggests that GNAL may bind to SGTP, with K55 being directly involved in nucleotide binding. Different from what we found for small GTPases, P-loop regions of all heterotrimeric G proteins quantified in our experiments exhibited similar binding selectivities toward SGTP and GTP. For instance, the aforementioned K55 from GNAL can be effectively labeled by GTP and SGTP probes at similar efficiency, suggesting the similar binding affinity of this protein to these two nucleotides (Figure 5G,H). The finding that SGTP competes with GTP in binding multiple heterotrimeric G proteins indicates that SGTP may affect heterotrimeric G-protein-mediated signaling. The signal amplitude of the G-protein-related pathway is a dynamic interplay of GDP/GTP exchange (activation) and GTP hydrolysis (deactivation), where the GDP-bound inactive form of heterotrimeric G proteins interact with membrane-bound G protein-coupled receptors.28 The competitive binding of SGTP instead of GTP to Gα subunit may block G protein activation by inhibiting Gα release. In addition, the loading of SGTP to Gα may lead to the accumulation of SGTP-bound, active form or SGDP-bound, inactive form of G proteins over time; either scenario may perturb G-protein-mediated signaling.

Competitive Binding of SGTP to Multiple CDKs

Aside from the various GTPases, we also made an interesting discovery that SGTP can bind to multiple CDKs. CDKs are serine/threonine kinases that become active only when coupled with specific types of cyclins. These CDKs and their activating cyclins (A, B, D, and E) are key regulators in mammalian cell cycle progression.29 For instance, CDK4/cyclin D and CDK2/cyclin E/A promote the passage through G1 and S phases, whereas CDK1/cyclin B, as the only nonredundant cell cycle driver, regulates the transition through late G2 and mitosis.30 Malfunction of CDKs, especially their hyperactivation may induce unregulated proliferation of cancer cells. Thus, CDKs are attractive targets for cancer therapy, and multiple CDK inhibitors have been introduced as anticancer drugs for preclinical and clinical evaluation.31

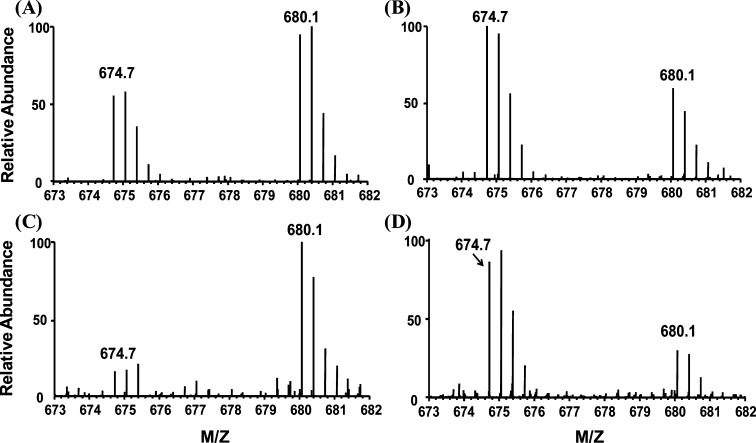

Intriguingly, our SGTP affinity profiling results showed that CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, CDK5, CDK6 can bind strongly to SGTP, with all RSGTP10/1 being <2. Moreover, we found that SGTP binds to the same binding motif (i.e., the HRD motif) in these CDKs as ATP.15 For instance, we successfully detected probe-labeled K147 located in the HRD motif of CDK6 (Figure 6A,B). In addition, results from SGTP/GTP competition experiment toward this unique ATP-binding HRD motif sequence indicate that CDK1 (RSGTP/GTP = 0.51), CDK2 (RSGTP/GTP = 0.85), CDK5 (RSGTP/GTP = 0.88) have similar nucleotide-binding preference between GTP and SGTP, whereas CDK4 (RSGTP/GTP = 3.33) and CDK6 (RSGTP/GTP = 3.85) display much stronger binding toward SGTP than GTP (Figure 6C,D). It is worth noting that CDK4 and CDK6 belong to the same D-type cyclin-dependent kinase group, which bind to and are activated by cyclin D.32 The structural and functional similarities of CDK4 and CDK6 are consistent with their comparable SGTP binding property, as revealed by the aforementioned SGTP affinity profiling experiment.

Figure 6.

Light- and heavy-labeled peptides of CDK6 from forward and reverse SGTP-affinity profiling and SGTP/GTP competition binding experiments. (A, B) Peptide DLK147#PQNILVTSSGQIK with a low RSGTP10/1 ratio from CDK6. (C, D) Peptide DLK147#PQNILVTSSGQIK with a high RSGTP/GTP ratio from CDK6; “#” indicates the desthiobiotin-labeling site.

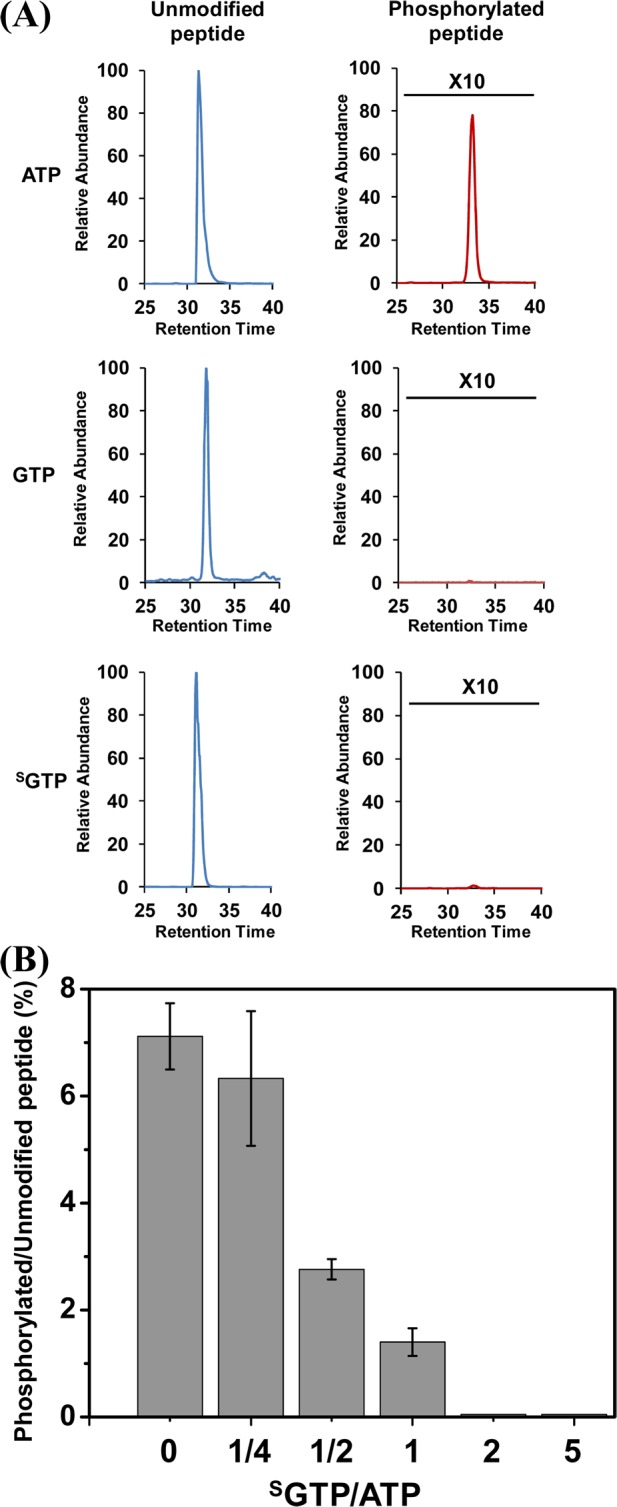

Although SGTP has been observed to bind to a broad spectrum of CDKs, it is possible that CDKs may be able to employ SGTP, in a similar manner as ATP, as phosphate donor to phosphorylate its substrate proteins, which may not perturb the functions of CDKs. To examine this possibility, we performed an in vitro kinase activity assay using purified CDK6 and a synthetic peptide EGLPT821PTKMTPPFR, derived from retinoblastoma-associated protein (Rb), which is a known CDK6 substrate.33 Mass spectrometry was employed to detect the phosphorylated substrate peptide. Our results showed that, in the presence of ATP, CDK6/cyclin D can successfully phosphorylate the substrate peptide with the signal ratio for phosphorylated/unmodified peptide being ∼7% (Figure 7A). Furthermore, the MS/MS supports the phosphorylation of Thr821 in the substrate peptide (Figure S2), which is consistent with previous finding.34 However, when the same in vitro kinase activity assay of CDK6 was conducted using GTP or SGTP to replace ATP as the phosphate donor, no phosphorylated peptide was observed. These results suggest that, although SGTP displays robust binding toward CDK6, CDK6 can only employ ATP as the phosphate donor to phosphorylate the Rb protein. Therefore, we further assessed the inhibitory effect of SGTP for CDK6 phosphorylation by conducting the same in vitro phosphorylation reaction with constant ATP concentration along with increasing amounts of SGTP. A significant inhibitory effect of CDK6 phosphorylation by SGTP binding was observed. As shown in Figure 7B, around 50% and 80% inhibition in CDK6 phosphorylation was observed when SGTP/ATP concentration ratios reached 1/2 and 1/1, respectively, whereas no phosphorylation was observed when the ratio was 2/1. Therefore, our results suggest that the competitive binding of SGTP to multiple CDKs may not only affect their binding toward endogenous ATP but also greatly affect the phosphorylation efficiency of the kinases. Thus, the SGTP introduced by thiopurine drug treatment may exert a profound effect on CDK activity, which may ultimately affect cell cycle progression.

Figure 7.

(A) In vitro CDK6 kinase activity assay employing ATP, GTP, and SGTP as phosphate donors. (B) Inhibitory effect of SGTP binding on in vitro CDK6 phosphorylation reaction.

Conclusions

Here, we introduced an orthogonal strategy encompassing the nucleotide affinity profiling assay and nucleotide binding competition assay to comprehensively characterize, at the entire proteome scale, SGTP-binding proteins. With the simultaneous use of SGTP and GTP affinity probes, 165 proteins involved in different biological processes were determined to be SGTP-binding targets. In addition, the selectivity between SGTP- and GTP-binding for these SGTP targets was further characterized. Unlike traditional binding competition assay, our SGTP/GTP binding selectivity was determined from the binding preference of SGTP/GTP toward the verified nucleotide-binding motif sequence, which provides superior specificity and accuracy. Our results suggest that SGTP mainly targets GTPases and affects various GTPase-mediated signaling pathways. Especially, SGTP exhibits strong binding affinity toward multiple heterotrimeric G proteins. Furthermore, we demonstrated for the first time that SGTP binds to multiple CDKs, which may perturb the CDK-mediated phosphorylation and cell cycle progression.

Nucleotides are susceptible to damage through exposure to various genotoxic agents, including reactive oxygen species generated from normal metabolism or from exposure to ionizing radiation and environmental chemicals.35 For example, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine triphosphate (8-oxoGTP) could be produced at appreciable levels in the cytoplasm.36 Some damaged nucleotides may be incorporated into RNA or DNA, thereby perturbing the flow of genetic information. Alternatively, damaged nucleotides may be recognized by certain cellular proteins to perturb relevant cellular functions. The analytical strategy presented here should be generally applicable for quantitative studies of proteins that can bind to 8-oxoGTP and any other damaged nucleotides at the whole proteome scale. Such studies should also result in the discovery of specific proteins that can bind to these damaged nucleotides and how these proteins recognize the damaged nucleotides versus their endogenous undamaged counterparts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 ES019873 to Y.W.), and Y.X. was supported by a Dissertation Research Award from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (20DT-0040).

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures, MS and MS/MS data, GO analysis results, and detailed lists of possible SGTP-binding proteins identified from Jurkat-T cells. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Elion G. Science 1989, 244, 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans W. E.; Relling M. V. Leuk. Res. 1994, 18, 811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann P. F.; Waters T. R.; Moulton D. C.; Xu Y.-Z.; Zheng Q.; Edwards M.; Mace R. Science 1996, 273, 1109–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran P.; Offman J.; Bignami M. Biochimie 2003, 85, 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krynetski E. Y.; Krynetskaia N. F.; Gallo A. E.; Murti K. G.; Evans W. E. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan B.; Zhang J.; Wang H.; Xiong L.; Cai Q.; Wang T.; Jacobsen S.; Pradhan S.; Wang Y. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1904–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem R.; Karran P. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 4787–4795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Fu L.; Wang Y. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2013, 12, 3803–3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiede I.; Fritz G.; Strand S.; Poppe D.; Dvorsky R.; Strand D.; Lehr H. A.; Wirtz S.; Becker C.; Atreya R.; Mudter J.; Hildner K.; Bartsch B.; Holtmann M.; Blumberg R.; Walczak H.; Iven H.; Galle P. R.; Ahmadian M. R.; Neurath M. F. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 111, 1133–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppe D.; Tiede I.; Fritz G.; Becker C.; Bartsch B.; Wirtz S.; Strand D.; Tanaka S.; Galle P. R.; Bustelo X. R.; Neurath M. F. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 640–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning G.; Whyte D. B.; Martinez R.; Hunter T.; Sudarsanam S. Science 2002, 298, 1912–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai Y.; Sasaki T.; Matozaki T. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 153–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormö M.; Sjöberg B.-M. Anal. Biochem. 1990, 189, 138–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnieri M. T.; Blagg B. S.; Zhao R. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2011, 9, 174–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y.; Guo L.; Wang Y. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 7478–7486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M.; Kato T.; Takenishi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 8, 5065–5068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramova T. V.; Vasileva S. V.; Serpokrylova I. Y.; Kless H.; Silnikov V. N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 6549–6555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y.; Guo L.; Jiang X.; Wang Y. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 3198–3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldgaard M.; Nyborg J.; Clark B. F. C. FASEB J. 1996, 10, 1347–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong S.-E.; Blagoev B.; Kratchmarova I.; Kristensen D. B.; Steen H.; Pandey A.; Mann M. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2002, 1, 376–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Liu D. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4848–4870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerapana E.; Wang C.; Simon G. M.; Richter F.; Khare S.; Dillon M. B. D.; Bachovchin D. A.; Mowen K.; Baker D.; Cravatt B. F. Nature 2010, 468, 790–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D. W.; Sherman B. T.; Lempicki R. A. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 4, 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrutskii B. S.; El’skaya A. V. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1998, 60, 47–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D.; Gygi S. P. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 1391–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraste M.; Sibbald P. R.; Wittinghofer A. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1990, 15, 430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox A. D.; Der C. J. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2002, 1, 599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preininger A. M.; Hamm H. E. Science 2004, 2004, 10.1126/stke.2182004re3. [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M.; Harlow E.; Hunt T.; Hunter T.; Lahti J. M.; Manning G.; Morgan D. O.; Tsai L.-H.; Wolgemuth D. J. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 1275–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev L. T.; Tovar C.; Chen S.; Knezevic D.; Zhao X.; Sun H.; Heimbrook D. C.; Chen L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 10660–10665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y.; Grant S. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2003, 3, 362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M.; Sotillo R. o.; Santamar1 a D.; Galán J.; Cerezo A.; Ortega S.; Dubus P.; Barbacid M. Cell 2004, 118, 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K.; Anjum R.; Yu Y.; Kunz R. C.; Andersen J. N.; Kraus M.; Keilhack H.; Nagashima K.; Krauss S.; Paweletz C.; Hendrickson R. C.; Feldman A. S.; Wu C.-L.; Rush J.; Villen J.; Gygi S. P. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 933–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki T.; Fukasawa K.; Suzuki-Takahashi I.; Semba K.; Kitagawa M.; Taya Y.; Hirai H. J. Biochem. 2005, 137, 381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimoto D.; Iyama T.; Nonaka M.; Abolhassani N.; Ohta E.; Sakumi K.; Nakabeppu Y. Mutat. Res. 2010, 703, 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S.-H.; Hyun J.-W.; Choi J.; Choi E.-Y.; Kim H.-J.; Lee S.-J.; Chung M.-H. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 327, 342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.