Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the association of CD147 and GLUT-1, which play important roles in glycolysis in response to radiotherapy and clinical outcomes in patients with locally advanced cervical squamous cell carcinoma (LACSCC). The records of 132 female patients who received primary radiation therapy to treat LACSCC at FIGO stages IB-IVA were retrospectively reviewed. Forty-seven patients with PFS (progression-free survival) of less than 36 months were regarded as radiation-resistant. Eighty-five patients with PFS longer than 36 months were regarded as radiation-sensitive. Using pretreatment paraffin-embedded tissues, we evaluated CD147 and GLUT-1 expression by immunohistochemistry. Overexpression of CD147, GLUT-1, and CD147 and GLUT-1 combined were 44.7%, 52.9% and 36.5%, respectively, in the radiation-sensitive group, and 91.5%, 89.4% and 83.0%, respectively, in the radiation-resistant group. The 5-year progress free survival (PFS) rates in the CD147-low, CD147-high, GLUT-1-low, GLUT-1-high, CD147- and/or GLUT-1-low and CD147- and GLUT-1- dual high expression groups were 66.79%, 87.10%, 52.78%, 85.82%, 55.94%, 82.90% and 50.82%, respectively. CD147 and GLUT-1 co-expression, FIGO stage and tumor diameter were independent poor prognostic factors for patients with LACSCC in multivariate Cox regression analysis. Patients with high expression of CD147 alone, GLUT-1 alone or co-expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 showed greater resistance to radiotherapy and a shorter PFS than those with low expression. In particular, co-expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 can be considered as a negative independent prognostic factor.

Keywords: Radiation resistance, CD147, GLUT-1, glycolysis, cervical carcinoma, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer death in females worldwide [1]. Radiation therapy (RT) can be used to treat all stages of cervical cancer and remains the most common management for locally advanced cervical cancer as preoperative or postoperative adjuvant or primary treatment, despite recent advances in cancer treatment such as cisplatin-containing concurrent chemotherapy with radiation [2-4]. Although radiotherapy plays an important role in the treatment of locally advanced or inoperable cervical carcinoma, the treatment results remain poor with external beam RT (EBRT) and brachytherapy (BRT). The resistance of tumor cells to radiation is a major therapeutic problem [5]. Although tumor size and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging may serve as markers for response to radiotherapy, they are not likely to fully account for the observed variability [5]. For example, the response to radiotherapy and prognosis vary for patients who may have the same tumor diameter and FIGO stage. There-fore, it is important to identify new markers to predict more accurately the response to radiotherapy and prognosis of an individual patient.

Malignant tumors vary in their response to irradiation as a consequence of resistance mechanisms taking place at the molecular level. It is important to understand these mechanisms of radioresistance, as counteracting them may improve the efficacy of radiotherapy. Radiosensitivity can be influenced both by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Some relevant factors influence radiosensitivity such as hypoxia [6-11], cell cycle [12-14], DNA damage and repair [15-19], apoptosis [20-23], growth factors and oncogenes [24-26], cancer stem cells and epigenetic modification of genes [27-29]. Furthermore, glycolysis that is tightly associated with the biological effects of radiation can also result in radiosensitivity differences.

In pioneering studies in the 1920s, Otto Warburg observed that cancers possess a remarkable ability to sustain high rates of anaerobic-like glycolysis even in the presence of oxygen: the Warburg effect. Many studies have certified that glycolytic metabolism in malignancies correlates with radioresistance [30,31]. There are three major reasons for this phenomenon. First, products of glycolysis accumulated in tumor cells constitute an intracellular redox buffer network that effectively scavenges free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [32-34]. Second, glycolysis supplies the tumor cells with ATP in hypoxic microenvironments [35,36]. Third, products of glycolysis also supply the anabolic precursors for de novo nucleotide and lipid synthesis [37], which are necessary for tumor high growth rates. Thus, glycolysis plays a critical role in tumor radioresistance.

CD147 (also known as extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer, basigin, neurotelin) is a multifunctional transmembrane protein with two extracellular Ig-like domains and a cytoplasmic tail of 40 amino acids [38]. This protein is an important molecule for tumor progression including tumor invasiveness, metastasis, proliferation, and angiogenesis through increasing production of hyaluronan [39], and stimulating the production of multiple matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) by fibroblasts, endothelial cells and tumors cells and the activation of VEGF-A by MMPs [40-45]. CD147 is described to be upregulated in several human cancers [46,47], including cervical squamous cell carcinoma [48] in which it was found to correlate with pelvic lymph-node metastasis and resistance to radiotherapy [49]. However, the mechanism by which CD147 induces radioresistance is not clear. Baba and coworkers reported that blocking CD147 using anti-human CD147 mouse monoclonal antibody MEM-M6/1 induces cell death in cancer cells through impairment of glycolytic energy metabolism in colon cancer, which includes inhibition of lactate uptake and lactate release, reduced intracellular pH (pHi), and decreased glycolytic flux and intracellular ATP [50]. Su and coworkers reported that a CD147-targeting siRNA inhibits the proliferation, invasiveness, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production of human malignant melanoma cells by downregulating glycolysis [51]. Therefore, there is a close relationship between CD147 and glycolysis. To reveal the possible mechanism, the researchers mainly focused on the complex formed by CD147 and monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), which is critical for lactate transport and pHi homeostasis and influences the glycolytic rate in tumor cells [52-54]. However, there are many other important steps aside from lactate transport that can affect glycolytic rates in tumor cells, such as glucose transport; the glucose transport for which GLUT-1 is mainly responsible is the first step of glucose metabolism and is a rate-limiting step. Moreover, some reports showed GLUT-1 is a marker of radioresistance in oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) [55]. Therefore, we hypothesized that CD147 may increase LACSCC radioresistance by improving glycolysis rates through upregulation of GLUT-1, thus increasing glucose uptake.

The first rate-limiting step of glucose metabolism is the transport of glucose across the plasma membrane. The GLUT family of proteins is responsible for this function. The most important member of this family in tumor cells is GLUT-1 [56]. More recently, overexpression of GLUT-1, representing a basic mechanism that may contribute to enhanced glucose metabolism, has been well documented in human solid tumors [55,57-61]. Despite slight differences in the staining procedure, type of analysis and cut-off values, all these studies have uniformly associated GLUT-1 overexpression with enhanced tumor aggressiveness and unfavorable clinical outcome. Considering that overwhelming clinical evidence has accumulated attesting to the biological significance of GLUT-1 in solid tumors, and that the glycolysis phenotype markedly correlates with radioresistance, we presume that there is some relationship between overexpression of GLUT-1 and radioresistance in LACSCC. In fact, it has been suggested that GLUT-1 inhibition downregulates glycolysis with a decreased rate of glucose uptake, induces cell-cycle arrest, and suppresses cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo [62]. Pedersen and coworkers even reported a hypoxia-independent effect of GLUT-1 on radiation resistance in small-cell lung cancer cells [62]. Furthermore, overexpression of GLUT-1 is associated with resistance to radiotherapy and adverse prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity [55]. From these evidences, we postulate that there is a relationship between overexpression of GLUT-1 and radioresistance in LACSCC. To the best of our knowledge, the potential relationship between GLUT-1 expression and tumor response to radiotherapy has not been systematically analyzed in LACSCC. Therefore, in the present study we set out to investigate whether GLUT-1 expression is related to the radioresistance of tumors at a clinically relevant level in LACSCC.

We investigated whether CD147 or GLUT-1 expression is related to tumor radioresistance and analyzed the relationship between the two proteins at a clinically relevant level. Our results established that CD147 expression alone, GLUT-1 expression alone and CD147 and GLUT-1 co-expression are markers of radioresistance in LACSCC, with high expression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 being associated with an independent unfavorable clinical outcome. In future studies, we will study the relationship between CD147 and GLUT-1 and the radioresistance mechanism through cytobiology and nude mouse xenograft experiments.

Material and methods

Patients and clinical tissue samples

The population of this retrospective cohort study consisted of 132 patients that had received primary radical RT in the Department of Radiation Oncology, Xiangya Hospital and Hunan Provincial Tumal Hospital, Central South University between January 2005 and March 2012. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) pathologically proven squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix; (b) no evidence of distant metastasis at diagnosis (FIGO stage IB-IVA); (c) the existence of tissue blocks available for our research; and (d) administration of no other anticancer treatment prior to primary RT, or surgery after RT. The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of our institution. Follow-up was closed in May 2012. The median follow-up time for survivors was 45 months (range, 2-85.5 months). The median progression-free survival (PFS) time was 43.5 months (range, 0-85.5 months). Patient median age was 51 years (range, 28-80 years). We divided the patients into two groups: the radiation-sensitive group (n=85) and the radiation-resistant group (n=47) [5]. The radiation-sensitive group included patients who showed no local recurrence and distant metastasis for ≥3 years after primary treatment (PFS ≥36 months).

The radiation-resistant group included patients who had tumors that did not respond to RT at all, or who experienced local recurrence or distant metastasis at <3 years after the primary treatment (PFS <36 months). Therefore, the radiation-resistant group was divided into three subgroups. The RT non-responsive subgroup consisted of patients whose primary tumor persisted and did not shrink markedly after primary treatment until time of death. The local recurrence subgroup consisted of patients whose primary tumor had initially disappeared but subsequently showed local recurrence at <3 years after the primary treatment. The distant metastasis subgroup consisted of patients whose primary tumor had disappeared after treatment but had then showed distant metastasis at <3 years after the primary treatment. PFS was defined as the period from the end of therapy to the date of the first documented evidence of recurrence or metastatic disease. Evidence was required from clinical physical examination, pathological biopsy or imaging studies. Each primary cervical tumor diameter was assessed by means of direct measurement during clinical physical examination rather than medical imaging. In our study, there were nine patients in the RT non-responsive subgroup, 17 in the local recurrence subgroup and 22 in the distant metastasis subgroup. One patient experienced distant metastasis during RT and their tumor did not respond to RT until death; consequently, we decided that this patient belonged not only to the RT non-responsive subgroup but also to the distant metastasis subgroup. Three patients experienced distant metastasis after RT, but their PFS was >36 months. Thus, these patients were classified in the radiation-sensitive group.

All patients were treated with EBRT and high-dose rate (HDR) intracavitary BRT after consultation with a radiation oncologist. HDR brachytherapy was initiated at 3-4 weeks after the commencement of EBRT. The median total dose at point A was 90 Gy (range, 66-102 Gy). The median dose of EBRT at point A was 46 Gy (range, 30-52 Gy). The median dose of HDR BRT at point A was 42 Gy (range, 20-54 Gy).

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemical detection of CD147 and GLUT-1, a 4-μm tissue section was deparaffinized in xylene followed by microwave treatment (CD147 for 20 min, GLUT-1 for 10 min at moderate heating) in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0). After cooling for 30 min and washing in PBS, endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min, followed by incubation with PBS containing 10% normal goat serum for 30 min. Specimens were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-CD147 (abcam ab666, 1:100) and anti-GLUT-1 (abcam ab652, 1:200) antibodies. Detection of immunostaining was performed using the ChemMate kit (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and 3,3-diaminobenzidine as the chromogene. For the negative control, the primary antibody was replaced by non-immune isotypic antibodies.

Evaluation of staining

The staining was viewed separately by two pathologists without prior knowledge of the clinical or clinicopathological statuses of the cases. The expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 was evaluated by scanning the entire tissue specimen under low-power magnification (×40), and then confirmed under high-power magnification (×400). An immunoreactivity score system was applied as follows: (1) number of positive stained cell ≤5% scored 0; 6-25% scored 1; 26-50% scored 2; 51-75% scored 3; >75% scored 4, (2) intensity of stain: colorless scored 0; weak (pallide-flavens) scored 1; moderate (yellow) scored 2; strong (brown) scored 3. Multiply (1) and (2). The staining score was stratified as - (0 score, absent), + (1-4 score, weak), ++ (5-8 score, moderate) and +++ (9-12 score, strong) according to the proportion and intensity of positively-stained cancer cells. Furthermore, - and + was considered as low expression. ++ and +++ was considered as high expression. Specimens were rescored if the differences in the scores from two pathologists was more than 3 [63].

Statistical analysis

Associations between CD147 and GLUT-1 expression and clinicopathological factors were analyzed using the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. Patients who survived until the end of the observation period were censored at their last follow-up visit. Patients who died because of causes other than cervical cancer were censored at their date of death. Survival curves were calculated using Kaplan–Meier estimates, and differences between groups were tested by log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses were performed according to the Cox proportional hazards model. CD147 expression alone (high vs low), GLUT-1 expression alone (high vs low), CD147 and GLUT-1 dual high expression (yes vs no), age (≥50 y vs <50 y), FIGO stage (III+IVa vs Ib+II), histopathological grade (middle + low vs high), and tumor diameter (>4 cm vs ≤4 cm) were included in the regression model. For all statistical tests, P≤0.05 was considered significant [64].

Results

Clinical and histopathological characteristics of LACSCC cases

The clinical and histopathological characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study are detailed in Table 1. There were 132 LACSCCs (47 in the radiation-resistant group and 85 in the radiation-sensitive group). There were significant differences in tumor diameter, FIGO stage and histological grading between the radiation-resistant group and the radiation-sensitive group (P<0.001, P=0.004 and P=0.014, respectively), but no significant differences in patient age, combined chemoradiotherapy (platinum-based), total dose at point A, EBRT dose at point A and BRT dose at point A between the two groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Parameters | Patients (n=132) | Radiation sensitivity | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| radiation-resistant group | radiation-sensitive group | |||

|

| ||||

| (n=47) | (n=85) | |||

| Age | 0.5591 | |||

| >50 years | 49 | 19 | 30 | |

| ≥50 years | 83 | 28 | 55 | |

| FIGO stage | 0.0041 | |||

| I+II | 70 | 17 | 53 | |

| III+IVa | 62 | 30 | 32 | |

| Histopathological grade | 0.0142 | |||

| High | 10 | 0 | 10 | |

| Middle+Low | 114+8 | 47 | 75 | |

| Tumor diameter | <0.0011 | |||

| ≤4 cm | 79 | 16 | 63 | |

| >4 cm | 53 | 31 | 22 | |

| Combined chemotherapy (platinum-based) | 0.4261 | |||

| Yes | 106 | 36 | 70 | |

| No | 26 | 11 | 15 | |

| Histological type (SCC) | 132 | 47 | 85 | |

| Total dose at point A | ||||

| median dose (range) (Gy) | 92 (67-102) | 89 (66-102) | 0.5853 | |

| EBRT dose of point A | ||||

| median dose (range) (Gy) | 48 (30-52) | 46 (36-50) | 0.5183 | |

| Brachytherapy dose at point A | ||||

| median dose (range) (Gy) | 46 (21-54) | 42 (20-54) | 0.3873 | |

p value was estimated by chi-square test.

p value was estimated by Fisher’s exact test.

p value was estimated by t-test.

FIGO = International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; SCC = Squamous Cell Carcinoma; Gy = gray unit; EBRT = external beam radiation therapy.

CD147 and GLUT-1 expression and their association with clinicopathological parameters

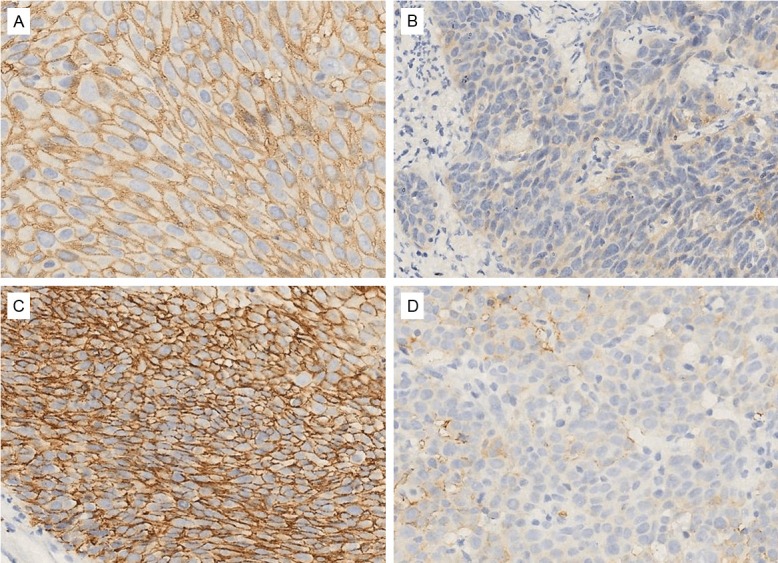

CD147 was located at the membranes of cervical carcinoma cells and staining was much stronger in the radiation-resistant group than the radiation-sensitive group (Figure 1A vs 1B). The low and high expression of CD147 was 38.6% (51/132) and 61.4% (81/132), respectively (Table 2). Significant associations were observed between CD147 expression and histopathological grade (P=0.013) and tumor diameter (P=0.046), but there was no significant association between CD147 expression and patient age or FIGO stage.

Figure 1.

Representative examples of CD147 and GLUT-1 staining of tumor in the radiation-resistant group and radiation-sensitive group. A: Strong positive staining of CD147 in the radiation-resistant group; B: Weak positive staining of CD147 in the radiation-sensitive group; C: Strong positive staining of GLUT-1 in the radiation-resistant group; D: Weak positive staining of GLUT-1 in the radiation-sensitive group. The bar size is the same for all the figures. Original magnification ×400.

Table 2.

Correlation between CD147 and GLUT-1 expression and clinicopathological parameters for LACSCC

| Parameters | Patients (n=132) | CD147 expression | p-value | GLUT-1 expression | p-value | CD147 and GLUT-1 dual high expression | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| low expression | high expression | low expression | high expression | Yes | No | |||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| n=51 | n=81 | n=45 | n=87 | n=70 | n=62 | |||||

| Age | 0.4441 | 0.7891 | 0.9961 | |||||||

| <50 years | 49 | 21 | 28 | 16 | 33 | 26 | 23 | |||

| ≥50 years | 83 | 30 | 53 | 29 | 54 | 44 | 39 | |||

| FIGO stage | 0.4841 | 0.6761 | 0.2751 | |||||||

| Ib+II | 70 | 29 | 41 | 25 | 45 | 34 | 36 | |||

| III+IVa | 62 | 22 | 40 | 20 | 42 | 36 | 26 | |||

| Histopathological grade | 0.0132 | 0.7342 | 0.0452 | |||||||

| High | 10 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| Middle+Low | 122 | 43 | 79 | 41 | 81 | 68 | 54 | |||

| Tumor diameter | 0.0461 | 0.0581 | 0.0361 | |||||||

| ≤4 cm | 79 | 36 | 43 | 32 | 47 | 36 | 43 | |||

| >4 cm | 53 | 15 | 38 | 13 | 40 | 34 | 19 | |||

p value was estimated by chi-square test.

p value was estimated by Fisher’s exact test.

LACSCC = Locally advanced cervical squamous cell carcinoma.

GLUT-1 was also located at cervical carcinoma cell membranes and staining was also much stronger in the radiation-resistant group than the radiation-sensitive group (Figure 1C vs 1D). The low and high expression of GLUT-1 was 34.1% (45/132) and 65.9% (87/132), respectively (Table 2). No significant association was observed between GLUT-1 expression and patient age, FIGO stage, histopathological grade, or tumor diameter.

In the LACSCC patients, the proportion with low expression of CD147 and/or GLUT-1 and high expression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 was 47.0% (62/132) and 53.0% (70/132), respectively (Table 2). Significant association was observed between CD147 and GLUT-1 co-expression and histopathological grade (P=0.045), and tumor diameter (P=0.036), but there was no significant association between CD147 and GLUT-1 co-expression and patient age or FIGO stage.

Relationship between expression of CD147 and GLUT-1

In total, there were 132 qualified patients in whom evaluation of CD147 and GLUT-1 expression could be carried out using immunostaining. Each marker was classified as low or high in the two types according to the degree of immunohistochemical staining (Table 3). Among the 81 CD147 high expression cases, 86.4% (70/81) also showed high GLUT-1 expression. In contrast, in the 51 CD147 low expression cases, only 33.3% (17/51) showed high GLUT-1 expression. A significant positive correlation was observed between CD147 and GLUT-1 expression (r=0.545, P<0.001).

Table 3.

Expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 in LACSCC patients

| GLUT-1 | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Low expression (n=45) | High expression (n=87) | |

| CD147 | ||

| Low expression (n=51) | 34 | 17 |

| High expression (n=81) | 11 | 70 |

| r=0.545 | ||

| p<0.001 | ||

p value was estimated by spearman-test.

CD147 and GLUT-1 expression and response to radiotherapy

The results of CD147 expression assessed using immunohistochemistry in the 132 LACSCC patients are summarized in Table 4. In the radiation-resistant group, the proportion of patients with low expression of CD147 was 8.5% (4/47) and the proportion with high expression was 91.5% (43/47). In the radiation-sensitive group, the proportion of patients with low CD147 expression was 55.3% (47/85) and the proportion with high expression was 44.7% (38/85). We compared the proportion of patients with high CD147 expression between the radiation-resistant and radiation-sensitive groups; the statistical difference was significant (P<0.001). The radiation-resistant group was subdivided into three subgroups in accordance with the patient clinical information. The proportion of patients with high CD147 expression in the RT non-responsive subgroup, the local recurrence subgroup and the distant metastasis subgroup was 100% (9/9), 88.2% (15/17), and 90.9% (20/22), respectively. The difference in the level of CD147 expression was also significant (RT non-responsive subgroup vs. radiation-sensitive group, P=0.003; local recurrence subgroup vs. radiation-sensitive group, P=0.001; distant metastasis subgroup vs. radiation-sensitive group, P<0.001).

Table 4.

Relationship between CD147 and GLUT-1 expression and response to radiotherapy

| Parameters | Patients (n=132) | CD147 expression | GLUT-1 expression | CD147 and GLUT-1 dual high expression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| low expression | high expression | p-value | low expression | high expression | p-value | Yes | No | p-value | ||

| Radiation sensitivity | <0.0011 | <0.0011 | <0.0011 | |||||||

| radiation-resistant group | 47 | 4 | 43 | 5 | 42 | 39 | 8 | |||

| radiation-sensitive group | 85 | 47 | 38 | 40 | 45 | 31 | 54 | |||

| RT non-response | 0.0032 | 0.0092 | <0.0012 | |||||||

| RT non-responsive subgroup | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 | |||

| radiation-sensitive group | 85 | 47 | 38 | 40 | 45 | 31 | 54 | |||

| local recurrence | 0.0011 | 0.0071 | 0.0011 | |||||||

| local recurrence subgroup | 17 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 15 | 14 | 3 | |||

| radiation-sensitive group | 85 | 47 | 38 | 40 | 45 | 31 | 54 | |||

| distant metastasis | <0.0011 | 0.0041 | 0.0011 | |||||||

| distant metastasis subgroup | 22 | 2 | 20 | 3 | 19 | 17 | 5 | |||

| radiation-sensitive group | 85 | 47 | 38 | 40 | 45 | 31 | 54 | |||

p value was estimated by chi-square test.

p value was estimated by Fisher’s exact test.

RT = Radiation therapy.

The results of GLUT-1 expression assessed using immunohistochemistry in the 132 LACSCC patients are summarized in Table 4. In the radiation-resistant group, the proportion of patients with low GLUT-1 expression was 10.6% (5/47) and the proportion with high expression was 89.4% (42/47). In the radiation-sensitive group, the proportion of patients with low GLUT-1 expression was 47.1% (40/85) and the proportion with high expression was 52.9% (45/85). We compared the proportion of patients with high GLUT-1 expression between the radiation-resistant and radiation-sensitive groups; the statistical difference was significant (P<0.001). The proportion of patients with high GLUT-1 expression in the RT non-responsive subgroup, the local recurrence subgroup and the distant metastasis subgroup was 100% (9/9), 88.2% (15/17), and 86.4% (19/22), respectively. The difference in the level of GLUT-1 expression was also significant (RT non-responsive subgroup vs. radiation-sensitive group, P=0.009; local recurrence subgroup vs. radiation-sensitive group, P=0.007; distant metastasis subgroup vs. radiation-sensitive group, P=0.004).

The results of the immunohistochemical evaluation of the co-expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 in the 132 LACSCC patients are summarized in Table 4. In the radiation-resistant group (47 patients), there was high expression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 in 39 (83.0%) patients and low expression of CD147 and/or GLUT-1 in 8 (17.0%) patients. In the radiation-sensitive group, there was high expression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 in 31 (36.5%) patients and low expression of CD147 and/or GLUT-1 in 54 (63.5%) patients. We compared the high expression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 between radiation-resistant and radiation-sensitive groups.The proportion of patients with high expression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 in the RT non-responsive subgroup, the local recurrence subgroup and the distant metastasis subgroup was 100% (9/9), 82.4% (14/17), and 77.3% (17/22), respectively. The difference in the co-expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 was also significant (RT non-responsive subgroup vs. radiation-sensitive group, P<0.001; local recurrence subgroup vs. radiation-sensitive group, P=0.001; distant metastasis subgroup vs. radiation-sensitive group, P=0.001).

CD147 and GLUT-1 expression and survival

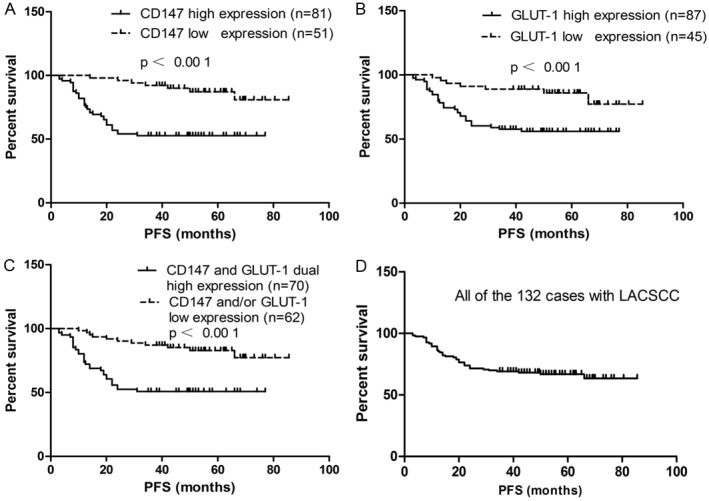

When the patient cohort was stratified according to tumor expression of CD147, the 5-year PFS rates in patients with low CD147 expression (n=51) and high CD147 expression (n=81) were 87.10% and 52.78%, respectively; Kaplan–Meier analysis (log-rank test) revealed a significant difference between the two groups (P<0.001; Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to CD147 and GLUT1 protein expression status for LACSCC patients. A: The 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 87.10% and 52.78% in patients with low CD147 expression (n=51) and high CD147 expression (n=81), respectively. There was a significant difference in the overall survival rate between the two groups (p<0.001). B: The 5-year PFS rates were 85.82% and 55.94% in patients with low GLUT-1 expression (n=45) and high GLUT-1 expression (n=87), respectively. There was a significant difference in the overall survival rate between the two groups (p<0.001). C: The 5-year PFS rates were 82.90% and 50.82% in patients that showed CD147 and/or GLUT-1 low expression (n=62) and CD147 and GLUT-1 dual high expression (n=70), respectively. There was a significant difference in the overall survival rate between the two groups (p<0.001). D: The 5-year PFS rate was 66.79% in all of the 132 patients with LACSCC.

With respect to GLUT-1 expression, the 5-year PFS rates in patients with low GLUT-1 expression (n=45) and high GLUT-1 expression (n=87) were 85.82% and 55.94%, respectively; Kaplan–Meier analysis (log-rank test) revealed a significant difference between the two groups (P<0.001; Figure 2B).

When the patient cohort was stratified according to co-expression of CD147 and GLUT-1, the 5-year PFS rates were 82.90% and 50.82% in patients that showed low expression of CD147 and/or GLUT-1 (n=62) and high expression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 (n=70), respectively. It was noteworthy that patients who had tumors with high expression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 had a worse prognosis than patients with tumors with low expression of CD147 and/or GLUT-1 (Kaplan–Meier analysis; log-rank test; P<0.001; Figure 2C). The 5-year PFS rate for all 132 patients was 66.79% (Figure 2D).

Univariate Cox regression analysis indicated that CD147 alone [hazard ratio (95% CI), 5.122 (2.563, 12.777); P<0.001], GLUT-1 alone [hazard ratio (95% CI), 4.254 (1.910, 9.477); P<0.001], CD147 and GLUT-1 co-expression [hazard ratio (95% CI), 4.639 (2.365, 9.098); P<0.001], FIGO stage [Hazard ratio (95% CI), 2.610 (1.453, 4.689); P=0.001] and tumor diameter [Hazard ratio (95% CI), 3.366 (1.885, 6.012); P<0.001] were prognostic predictors of progression-free survival in patients with cervical SCC (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate COX regression analysis of the relationships between clinicopathological outcomes in LACSCC patients

| Variable | Subset | Hazard radio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis (n=132) | |||

| CD147 expression alone | high vs. low | 5.122 (2.563, 12.777) | <0.001 |

| GLUT-1 expression alone | high vs. low | 4.254 (1.910, 9.477) | <0.001 |

| CD147 AND GLUT-1 expression | CD147 and GLUT-1 dual high vs. CD147 and/or GLUT-1 low | 4.639 (2.365, 9.098) | <0.001 |

| Age | ≥50 years vs. <50 years | 0.872 | |

| FIGO stage | III+IVa vs. Ib+II | 2.610 (1.453, 4.689) | 0.001 |

| Histopathological grade | low+middle vs. high | 0.067 | |

| Tumor diameter | >4 cm vs. ≤4 cm | 3.366 (1.885, 6.012) | <0.001 |

| Combined chemotherapy (platinum-based) | yes vs. no | 0.446 | |

| Multivariate analyses (n=132) | |||

| CD147 expression alone | high vs. low | 0.092 | |

| GLUT-1 expression alone | high vs. low | 0.303 | |

| CD147 AND GLUT-1 expression | CD147 and GLUT-1 dual high vs. CD147 and/or GLUT-1 low | 4.114 (2.081, 8.134) | <0.001 |

| Age | ≥50 years vs. <50 years | 0.245 | |

| FIGO stage | III+IVa vs. Ib+II | 2.657 (1.462, 4.831) | 0.001 |

| Histopathological grade | Low+Middle vs. high | 0.057 | |

| Tumor diameter | >4 cm vs. ≤4 cm | 2.851 (1.583, 5.135) | <0.001 |

| Combined chemotherapy (platinum-based) | yes vs. no | 0.375 |

CI = confidence interval.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that CD147 alone and GLUT-1 alone were not informative independent prognostic factors in this group of patients with LACSCC (CD147 alone, P=0.092; GLUT-1 alone, P=0.303). However, CD147 and GLUT-1 co-expression had significant, independent negative predictive value for progression-free survival in patients with LACSCC [Hazard ratio (95% CI), 4.114 (2.081, 8.134); P<0.001]. In addition, FIGO stage and tumor diameter were also independent negative prognosis predictors in patients with cervical SCC [Hazard ratio (95% CI), 2.657 (1.462, 4.831), 2.851 (1.583, 5.135); P=0.001 and P<0.001, respectively] (Table 5).

Discussion

First, we observed that CD147 expression was associated with histopathological grade and tumor diameter, but not with other clinicopathological factors in our study. CD147 expression in breast carcinomas was associated with risk factors such as poor histological grade, negative hormone status, mitotic index, and tumor size [65]. Higher CD147 immunostaining scores in hepatocellular carcinomas correlate significantly with tumor grading and tumor-node-metastasis stage [66]. In gastric carcinoma, CD147 expression was positively correlated with tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymphatic invasion, but not with lymph node metastasis, stage, or differentiation [67]. However, CD147 protein expression patterns within esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and dysplastic lesions were not associated with any of these clinicopathological factors [68]. These discrepancies suggest that there are different regulatory mechanisms of CD147 expression in cells of different origin. Second, CD147 overexpression was shown to be associated with radioresistance in LACSCC in our study. Even when the radiation-resistant group was divided into three subgroups (the RT non-responsive subgroup, local recurrence subgroup, and distant metastasis subgroup), CD147 overexpression was associated with the response to radiotherapy in each subgroup. This result suggested that CD147 overexpression in cervical cancer was associated with tumor invasion and metastasis and played a central role in radioresistance [49]. Moreover, our discovery was consistent with the previous reports of the roles of CD147 in tumor progression, including ovarian tumors [69], gliomas [70], hepatoma [71], oral squamous cell carcinoma [72], melanoma [73] and nasopharyngeal carcinoma [74]. Third, from our study, we found the PFS of patients with low CD147 expression was much longer than those with high CD147 expression, and CD147 overexpression can be considered a significant predictor of poor tumor-specific survival by Kaplan–Meier and log-rank tests. Although CD147 overexpression was one of the strong prognostic factors for poor outcome in univariate COX regression analysis, the importance was not significant in multivariate COX regression analysis. Similar studies in breast cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, and ovarian serous cancers have shown that CD147 expression seems to correlate with poor prognosis, but it cannot be viewed as an independent prognostic factor [49]. Besides these studies, Tian and coworkers showed that CD147 was an independent negative prognostic factor for patients with astrocytic glioma [63].

In our study, we observed a tight relationship between CD147 expression and radioresistance in patients with LACSCC. However, the mechanism underlying this observation is not known. Ju made similar discoveries in patients with cervical carcinoma [49]. Although the experimental design had some differences compared with our experiments, we both presumed that CD147 played an important role in radioresistance. Referring to the possible mechanism, Ju postulated that this might be attributed to the known function of CD147, such as stimulating the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and conferring resistance to anoikis [49], but they did not undertake further experiments. In our opinion, CD147, which plays important roles in tumor invasiveness, metastasis, cellular proliferation, VEGF production, tumor cell glycolysis, and multi-drug resistance, needs to interact with other molecules to produce a marked biological effect. For example, CAV-1 and CD147 co-expression is an independent prognostic factor while CAV-1 expression alone or CD147 expression alone are not independent prognostic factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients by multivariate analysis [74]. As CD147 protein levels are upregulated by CAV-1 overexpression, this can promote secretion of active MMP-3 and MMP-11 protein so as to increase the cancer cell migratory ability. In another report, co-expression of CD147 with MCT1 was significantly associated with lymph-node metastasis while single expression of CD147 or MCT1 was not correlated with migration in cervical adenocarcinomas [75]. The CD147/MCT complex can promote glycolysis in tumor cells, which increases the invasive ability of cancer cells. Therefore, the interaction of two molecules is more important than only one molecule alone for some biological effects. Considering the relationship between CD147, glycolysis and glucose transport as the first step of glycolysis, which is mainly mediated by GLUT-1 as described before, we detected the expression of GLUT-1 to study whether co-expression of CD147 with GLUT-1 can increase radioresistance in LACSCC. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has investigated the co-expression of CD147 with GLUT-1 and its significance in radiotherapy outcome.

GLUT-1 is a member of the GLUT family and is responsible for basal glucose transport across the plasma membrane into the cytosol in many cancer cells, which is a rate-limiting step in glucose metabolism [76]. Liu demonstrated that the application of antisense oligodeoxynucleotide can downregulate the expression of GLUT-1 mRNA and protein, and inhibit glucose uptake and glycolysis partially in HepG-2 cells [77]. Therefore, the function of GLUT-1 is critical for glycolysis. This transporter is overexpressed in many tumors, including hepatic, pancreatic, breast, esophageal, brain, renal, lung, cutaneous, colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, and cervical cancers [78]. Several studies have shown a close relationship between GLUT-1 expression, tumor development, and unfavorable prognosis of several tumors including oral squamous cell carcinoma, prostate carcinoma, bone and soft-tissue sarcomas and epithelial ovarian tumors [79]. Our outcomes were similar to these studies. In our study, GLUT-1 expression seemed to be associated with tumor diameter while the difference was not significant (P=0.58) and was not associated with any other clinicopathological factors. However, GLUT-1 expression levels were inversely correlated with radiation response and the difference was also significant when the radiation-resistant group was divided into three subgroups. Most importantly, the PFS of patients with low GLUT-1 expression was much longer than those with high expression, and GLUT-1 overexpression can be considered as a significant predictor of poor tumor-specific survival by Kaplan–Meier and log-rank tests. It was predictive of the clinical outcome in univariate but not in multivariate survival analyses,with high GLUT-1 expression being associated with poor survival.

Although the association between GLUT-1 expression and radioresistance has not previously been established at the clinical level in LACSCC, there had been another study of GLUT-1 expression in oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) treated with radiotherapy at the clinical level [55]. In this study, Kunkel and coworkers determined GLUT-1 expression by immunohistochemistry in 40 pretreatment OSCC biopsies categorized by radiation response through histopathology of the resection specimens, and indicated that pretreatment GLUT-1 expression in the tumor is a marker of radioresistance in OSCC, with high expression being associated with poor radiation response and shorter survival. In vitro experiments and tumor xenograft studies reported by Pedersen and coworkers argue that GLUT-1 expression plays a hypoxia-independent role in the modulation of radiation susceptibility and demonstrated a linkage between GLUT-1 expression and radiation resistance in two cell sublines (CPH-54A and CPH-54B) derived from a single small cell carcinoma of the lung [62]. All these studies provided support for the hypothesis that the function of GLUT-1 directly affected cancer cellular radiosensitivity.

In addition, we observed that the relationship between CD147 expression and GLUT-1 expression was significant. Taking a step further, we found that overexpression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 was inversely correlated with radiation response and, most importantly, it was predictive of clinical outcome in both univariate and multivariate survival analyses, with overexpression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 being associated with poor survival. Thus, overexpression of both CD147 and GLUT-1 but not CD147 or GLUT-1 alone was a significant predictor of poor tumor-specific survival and an independent negative prognostic factor for patients with LACSCC. Interestingly, the interaction of CD147 and GLUT-1 seemed to play a more important role in the radioresistance process than CD147 or GLUT-1 alone. We identified that co-expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 upregulated the glycolysis rate more markedly so as to enhance the radioresistance of LACSCC. It will be absolutely necessary to study the relationship between CD147 and GLUT-1 and the radioresistance mechanism through cytobiology and nude mouse xenograft experiments.

As described by Warburg more than 50 years ago, tumor cells maintain a high glycolytic rate even in conditions of adequate oxygen supply [80], and the glycolytic phenotype in malignancies tightly correlates with radioresistance [30,31,81]. They showed that the concentration of lactate, which is a product of glycolysis, correlates with tumor response after fractionated irradiation in Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) xenografts. We concluded that glycolysis enhanced radioresistance via three mechanisms. First, when ionizing radiation is absorbed in tissue, free radicals and ROS are produced as a result of ionization either directly in the DNA molecule itself or indirectly in other cellular molecules, primarily water (H2O). Both the free radicals and ROS can break chemical bonds and initiate the chain of events resulting in DNA damage. Apart from the hypoxia protective mechanism, tumor cells counter the direct and indirect action of radiotherapy by upregulation of their endogenous antioxidant capacity through accumulation of pyruvate, lactate, and the redox couples glutathione/glutathione disulfide and NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+. These molecules, which are products of glucose metabolism, constitute an intracellular redox buffer network that effectively scavenges free radicals and ROS [81]. This redox adaptation is an important mechanistic concept that explains why cancer cells become resistant to radiotherapy [33]. Second, glycolysis can supply ATP for the physiological functions of cancer cells. Tumor cells require a vast vasculature system for their supply of nutrients and oxygen, but oxygen cannot diffuse further than approximately 150 μm through tissues. As tumor growth outstrips its vasculature, the cells become hypoxic [82]. Because of their inherently hypoxic environment, cancer cells often resort to glycolysis, or the anaerobic breakdown of glucose to form ATP to provide for their energy needs [79]. Liu and coworkers showed inhibition of GLUT-1 decreases ATP levels resulting in reduced cancer cell viability in vitro, which inhibits tumor growth in in vivo tumor models. Addition of ATP rescues GLUT-1-inhibited cancer cells, suggesting that glycolysis inhibition has an anticancer effect partially through ATP depletion [36]. Other preclinical studies that blocked tumor glucose metabolism at several levels have been shown to decrease the ATP level and to radiosensitize different solid tumors [81]. Third, products of aerobic glycolysis can supply sufficient material to synthesis biomass such as nucleotides, amino acids and lipids that are essential for tumor cell growth and proliferation [83]. The aerobic glycolysis generates only two ATP molecules per molecule of glucose, whereas oxidative phosphorylation generates up to 36 ATP molecules upon complete oxidation of one glucose molecule [84]. However, the tumor cells are exposed to a continuous supply of glucose in circulating blood and the ATP generated by aerobic glycolysis is abundant for its requirement. Therefore, the tumor cells switch to this less efficient aerobic glycolysis to satisfy the anabolic metabolism [83]. All these advantages support the idea that aerobic glycolysis enable cancer cells to acquire more radioresistance potentiality.

The present retrospective study had a limitation. Although the most significant change in the standard radiation treatment for cervical cancer has been the use of cisplatin-containing concurrent chemotherapy in combination with RT for patients with locoregionally advanced disease (which has demonstrated a marked improvement in survival) [2-4], we found that this platinum-containing chemotherapy regimen did not influence patient survival. A possible reason for this was that we did not take into consideration in detail the types of platinum drugs used, other combined chemotherapy drugs, the frequency of chemotherapy, and the sequence of chemotherapy and RT. The number of patients who received this platinum-containing chemotherapy was not statistically different among the radiation-sensitive group and the radiation-resistant group; thus, its influence may have been equivalent among the two groups, despite the chemotherapy having some influence on radiosensitivity, and did not affect outcomes in our study. Similar conclusions were reached by Kim and coworkers in their studies [5,85].

In summary, although the glycolytic rate was suppressed and the glucose transport was also markedly decreased after CD147 suppression by siRNA or some inhibitors, we did not find direct evidence to demonstrate the interaction of CD147 and GLUT-1. However, our data showed co-expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 was clearly connected with radioresistance and was an independent negative prognostic factor for patients with LACSCC at the clinical level. Therefore, co-expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 can be regarded as both a therapeutic target and a prognostic factor, and may suggest a novel strategy to study the radiation-resistant mechanism. Future studies should investigate the interaction of CD147 and GLUT-1 in LACSCC.

Acknowledgements

This work was subsidized by grants: National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 81372792, 81225013, 81101193]; Hunan Department of Science and Technology Foundation [grant numbers 2013SK2019]; and the Freedom Explore Fund for the Doctoral Program of Central South University [grant number 2013zzts089].

Disclosure of conflict of interest

There is no competing interest for all authors.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keys HM, Bundy BN, Stehman FB, Muderspach LI, Chafe WE, Suggs CL 3rd, Walker JL, Gersell D. Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1154–1161. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris M, Eifel PJ, Lu J, Grigsby PW, Levenback C, Stevens RE, Rotman M, Gershenson DM, Mutch DG. Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and paraaortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1137–1143. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, Thigpen JT, Deppe G, Maiman MA, Clarke-Pearson DL, Insalaco S. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1144–1153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim TJ, Lee JW, Song SY, Choi JJ, Choi CH, Kim BG, Lee JH, Bae DS. Increased expression of pAKT is associated with radiation resistance in cervical cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1678–1682. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karar J, Maity A. Modulating the tumor microenvironment to increase radiation responsiveness. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:1994–2001. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.21.9988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wouters A, Pauwels B, Lardon F, Vermorken JB. Review: implications of in vitro research on the effect of radiotherapy and chemotherapy under hypoxic conditions. Oncologist. 2007;12:690–712. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-6-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockwell S, Dobrucki IT, Kim EY, Marrison ST, Vu VT. Hypoxia and radiation therapy: past history, ongoing research, and future promise. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:442–458. doi: 10.2174/156652409788167087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheehan JP, Shaffrey ME, Gupta B, Larner J, Rich JN, Park DM. Improving the radiosensitivity of radioresistant and hypoxic glioblastoma. Future Oncol. 2010;6:1591–1601. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen-Jonathan Moyal E. [Angiogenic inhibitors and radiotherapy: from the concept to the clinical trial] . Cancer Radiother. 2009;13:562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dewhirst MW, Cao Y, Moeller B. Cycling hypoxia and free radicals regulate angiogenesis and radiotherapy response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:425–437. doi: 10.1038/nrc2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimura T, Kakuda S, Ochiai Y, Nakagawa H, Kuwahara Y, Takai Y, Kobayashi J, Komatsu K, Fukumoto M. Acquired radioresistance of human tumor cells by DNA-PK/AKT/GSK3beta-mediated cyclin D1 overexpression. Oncogene. 2010;29:4826–4837. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozeki M, Tamae D, Hou DX, Wang T, Lebon T, Spitz DR, Li JJ. Response of cyclin B1 to ionizing radiation: regulation by NF-kappaB and mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme MnSOD. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:2657–2663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He J, Li J, Ye C, Zhou L, Zhu J, Wang J, Mizota A, Furusawa Y, Zhou G. Cell cycle suspension: a novel process lurking in G(2) arrest. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1468–1476. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.9.15510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parliament MB, Murray D. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of DNA repair genes as predictors of radioresponse. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2010;20:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith J, Tho LM, Xu N, Gillespie DA. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;108:73–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380888-2.00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolderson E, Richard DJ, Zhou BB, Khanna KK. Recent advances in cancer therapy targeting proteins involved in DNA double-strand break repair. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6314–6320. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Yang M, Bi N, Fang M, Sun T, Ji W, Tan W, Zhao L, Yu D, Lin D, Wang L. ATM polymorphisms are associated with risk of radiation-induced pneumonitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:1360–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beskow C, Skikuniene J, Holgersson A, Nilsson B, Lewensohn R, Kanter L, Viktorsson K. Radioresistant cervical cancer shows upregulation of the NHEJ proteins DNA-PKcs, Ku70 and Ku86. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:816–821. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peltonen JK, Vahakangas KH, Helppi HM, Bloigu R, Paakko P, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T. Specific TP53 mutations predict aggressive phenotype in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective archival study. Head Neck Oncol. 2011;3:20. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehmann BD, McCubrey JA, Jefferson HS, Paine MS, Chappell WH, Terrian DM. A dominant role for p53-dependent cellular senescence in radiosensitization of human prostate cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:595–605. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki Y, Oka K, Yoshida D, Shirai K, Ohno T, Kato S, Tsujii H, Nakano T. Correlation between survivin expression and locoregional control in cervical squamous cell carcinomas treated with radiation therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:642–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu X, Chen L, Wang J, Guan X, Geng H, Zhang Q, Song H. SiRNA-mediated survivin inhibition enhances chemo- or radiosensivity of colorectal cancer cells in tumor-bearing nude mice. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1445–1452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li HF, Kim JS, Waldman T. Radiation-induced Akt activation modulates radioresistance in human glioblastoma cells. Radiat Oncol. 2009;4:43. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukherjee B, McEllin B, Camacho CV, Tomimatsu N, Sirasanagandala S, Nannepaga S, Hatanpaa KJ, Mickey B, Madden C, Maher E, Boothman DA, Furnari F, Cavenee WK, Bachoo RM, Burma S. EGFRvIII and DNA double-strand break repair: a molecular mechanism for radioresistance in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4252–4259. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergkvist GT, Argyle DJ, Pang LY, Muirhead R, Yool DA. Studies on the inhibition of feline EGFR in squamous cell carcinoma: enhancement of radiosensitivity and rescue of resistance to small molecule inhibitors. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:927–937. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.11.15525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumann M, Krause M, Hill R. Exploring the role of cancer stem cells in radioresistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:545–554. doi: 10.1038/nrc2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawano T, Akiyama M, Agawa-Ohta M, Mikami-Terao Y, Iwase S, Yanagisawa T, Ida H, Agata N, Yamada H. Histone deacetylase inhibitors valproic acid and depsipeptide sensitize retinoblastoma cells to radiotherapy by increasing H2AX phosphorylation and p53 acetylation-phosphorylation. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:787–795. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim IA, Kim IH, Kim HJ, Chie EK, Kim JS. HDAC inhibitor-mediated radiosensitization in human carcinoma cells: a general phenomenon? J Radiat Res. 2010;51:257–263. doi: 10.1269/jrr.09115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quennet V, Yaromina A, Zips D, Rosner A, Walenta S, Baumann M, Mueller-Klieser W. Tumor lactate content predicts for response to fractionated irradiation of human squamous cell carcinomas in nude mice. Radiother Oncol. 2006;81:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sattler UG, Meyer SS, Quennet V, Hoerner C, Knoerzer H, Fabian C, Yaromina A, Zips D, Walenta S, Baumann M, Mueller-Klieser W. Glycolytic metabolism and tumour response to fractionated irradiation. Radiother Oncol. 2010;94:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sattler UG, Mueller-Klieser W. The anti-oxidant capacity of tumour glycolysis. Int J Radiat Biol. 2009;85:963–971. doi: 10.3109/09553000903258889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cook JA, Gius D, Wink DA, Krishna MC, Russo A, Mitchell JB. Oxidative stress, redox, and the tumor microenvironment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2004;14:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy AG, Zage PE, Akers LJ, Ghisoli ML, Chen Z, Fang W, Kannan S, Graham T, Zeng L, Franklin AR, Huang P, Zweidler-McKay PA. The combination of the novel glycolysis inhibitor 3-BrOP and rapamycin is effective against neuroblastoma. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:191–199. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9551-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Cao Y, Zhang W, Bergmeier S, Qian Y, Akbar H, Colvin R, Ding J, Tong L, Wu S, Hines J, Chen X. A small-molecule inhibitor of glucose transporter 1 downregulates glycolysis, induces cell-cycle arrest, and inhibits cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1672–1682. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bui T, Thompson CB. Cancer’s sweet tooth. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:419–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biswas C, Zhang Y, DeCastro R, Guo H, Nakamura T, Kataoka H, Nabeshima K. The human tumor cell-derived collagenase stimulatory factor (renamed EMMPRIN) is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Cancer Res. 1995;55:434–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marieb EA, Zoltan-Jones A, Li R, Misra S, Ghatak S, Cao J, Zucker S, Toole BP. Emmprin promotes anchorage-independent growth in human mammary carcinoma cells by stimulating hyaluronan production. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1229–1232. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iacono KT, Brown AL, Greene MI, Saouaf SJ. CD147 immunoglobulin superfamily receptor function and role in pathology. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nabeshima K, Iwasaki H, Koga K, Hojo H, Suzumiya J, Kikuchi M. Emmprin (basigin/CD147): matrix metalloproteinase modulator and multifunctional cell recognition molecule that plays a critical role in cancer progression. Pathol Int. 2006;56:359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li R, Huang L, Guo H, Toole BP. Basigin (murine EMMPRIN) stimulates matrix metalloproteinase production by fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2001;186:371–379. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(2000)9999:999<000::AID-JCP1042>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caudroy S, Polette M, Nawrocki-Raby B, Cao J, Toole BP, Zucker S, Birembaut P. EMMPRIN-mediated MMP regulation in tumor and endothelial cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2002;19:697–702. doi: 10.1023/a:1021350718226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun J, Hemler ME. Regulation of MMP-1 and MMP-2 production through CD147/extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer interactions. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2276–2281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang Y, Nakada MT, Kesavan P, McCabe F, Millar H, Rafferty P, Bugelski P, Yan L. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer stimulates tumor angiogenesis by elevating vascular endothelial cell growth factor and matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3193–3199. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riethdorf S, Reimers N, Assmann V, Kornfeld JW, Terracciano L, Sauter G, Pantel K. High incidence of EMMPRIN expression in human tumors. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1800–1810. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gabison EE, Hoang-Xuan T, Mauviel A, Menashi S. EMMPRIN/CD147, an MMP modulator in cancer, development and tissue repair. Biochimie. 2005;87:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sier CF, Zuidwijk K, Zijlmans HJ, Hanemaaijer R, Mulder-Stapel AA, Prins FA, Dreef EJ, Kenter GG, Fleuren GJ, Gorter A. EMMPRIN-induced MMP-2 activation cascade in human cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2991–2998. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ju XZ, Yang JM, Zhou XY, Li ZT, Wu XH. EMMPRIN expression as a prognostic factor in radiotherapy of cervical cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:494–501. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baba M, Inoue M, Itoh K, Nishizawa Y. Blocking CD147 induces cell death in cancer cells through impairment of glycolytic energy metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Su J, Chen X, Kanekura T. A CD147-targeting siRNA inhibits the proliferation, invasiveness, and VEGF production of human malignant melanoma cells by down-regulating glycolysis. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirk P, Wilson MC, Heddle C, Brown MH, Barclay AN, Halestrap AP. CD147 is tightly associated with lactate transporters MCT1 and MCT4 and facilitates their cell surface expression. EMBO J. 2000;19:3896–3904. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida S, Shibata M, Yamamoto S, Hagihara M, Asai N, Takahashi M, Mizutani S, Muramatsu T, Kadomatsu K. Homo-oligomer formation by basigin, an immunoglobulin superfamily member, via its N-terminal immunoglobulin domain. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:4372–4380. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kennedy KM, Dewhirst MW. Tumor metabolism of lactate: the influence and therapeutic potential for MCT and CD147 regulation. Future Oncol. 2010;6:127–148. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kunkel M, Moergel M, Stockinger M, Jeong JH, Fritz G, Lehr HA, Whiteside TL. Overexpression of GLUT-1 is associated with resistance to radiotherapy and adverse prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Macheda ML, Rogers S, Best JD. Molecular and cellular regulation of glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins in cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:654–662. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Younes M, Brown RW, Stephenson M, Gondo M, Cagle PT. Overexpression of Glut1 and Glut3 in stage I nonsmall cell lung carcinoma is associated with poor survival. Cancer. 1997;80:1046–1051. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970915)80:6<1046::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haber RS, Rathan A, Weiser KR, Pritsker A, Itzkowitz SH, Bodian C, Slater G, Weiss A, Burstein DE. GLUT1 glucose transporter expression in colorectal carcinoma: a marker for poor prognosis. Cancer. 1998;83:34–40. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980701)83:1<34::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cantuaria G, Fagotti A, Ferrandina G, Magalhaes A, Nadji M, Angioli R, Penalver M, Mancuso S, Scambia G. GLUT-1 expression in ovarian carcinoma: association with survival and response to chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92:1144–1150. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1144::aid-cncr1432>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawamura T, Kusakabe T, Sugino T, Watanabe K, Fukuda T, Nashimoto A, Honma K, Suzuki T. Expression of glucose transporter-1 in human gastric carcinoma: association with tumor aggressiveness, metastasis, and patient survival. Cancer. 2001;92:634–641. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010801)92:3<634::aid-cncr1364>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Airley R, Loncaster J, Davidson S, Bromley M, Roberts S, Patterson A, Hunter R, Stratford I, West C. Glucose transporter glut-1 expression correlates with tumor hypoxia and predicts metastasis-free survival in advanced carcinoma of the cervix. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:928–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pedersen MW, Holm S, Lund EL, Hojgaard L, Kristjansen PE. Coregulation of glucose uptake and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in two small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) sublines in vivo and in vitro. Neoplasia. 2001;3:80–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tian L, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Cai M, Dong H, Xiong L. EMMPRIN is an independent negative prognostic factor for patients with astrocytic glioma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bachtiary B, Schindl M, Potter R, Dreier B, Knocke TH, Hainfellner JA, Horvat R, Birner P. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha indicates diminished response to radiotherapy and unfavorable prognosis in patients receiving radical radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2234–2240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reimers N, Zafrakas K, Assmann V, Egen C, Riethdorf L, Riethdorf S, Berger J, Ebel S, Janicke F, Sauter G, Pantel K. Expression of extracellular matrix metalloproteases inducer on micrometastatic and primary mammary carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3422–3428. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsai WC, Chao YC, Lee WH, Chen A, Sheu LF, Jin JS. Increasing EMMPRIN and matriptase expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: tissue microarray analysis of immunohistochemical scores with clinicopathological parameters. Histopathology. 2006;49:388–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng HC, Takahashi H, Murai Y, Cui ZG, Nomoto K, Miwa S, Tsuneyama K, Takano Y. Upregulated EMMPRIN/CD147 might contribute to growth and angiogenesis of gastric carcinoma: a good marker for local invasion and prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1371–1378. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ishibashi Y, Matsumoto T, Niwa M, Suzuki Y, Omura N, Hanyu N, Nakada K, Yanaga K, Yamada K, Ohkawa K, Kawakami M, Urashima M. CD147 and matrix metalloproteinase-2 protein expression as significant prognostic factors in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101:1994–2000. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jin JS, Yao CW, Loh SH, Cheng MF, Hsieh DS, Bai CY. Increasing expression of extracellular matrix metalloprotease inducer in ovary tumors: tissue microarray analysis of immunostaining score with clinicopathological parameters. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25:140–146. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000189244.57145.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sameshima T, Nabeshima K, Toole BP, Yokogami K, Okada Y, Goya T, Koono M, Wakisaka S. Expression of emmprin (CD147), a cell surface inducer of matrix metalloproteinases, in normal human brain and gliomas. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:21–27. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001001)88:1<21::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jiang JL, Zhou Q, Yu MK, Ho LS, Chen ZN, Chan HC. The involvement of HAb18G/CD147 in regulation of store-operated calcium entry and metastasis of human hepatoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46870–46877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bordador LC, Li X, Toole B, Chen B, Regezi J, Zardi L, Hu Y, Ramos DM. Expression of emmprin by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kanekura T, Chen X, Kanzaki T. Basigin (CD147) is expressed on melanoma cells and induces tumor cell invasion by stimulating production of matrix metalloproteinases by fibroblasts. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:520–528. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Du ZM, Hu CF, Shao Q, Huang MY, Kou CW, Zhu XF, Zeng YX, Shao JY. Upregulation of caveolin-1 and CD147 expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma enhanced tumor cell migration and correlated with poor prognosis of the patients. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1832–1841. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pinheiro C, Longatto-Filho A, Pereira SM, Etlinger D, Moreira MA, Jube LF, Queiroz GS, Schmitt F, Baltazar F. Monocarboxylate transporters 1 and 4 are associated with CD147 in cervical carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2009;26:97–103. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2009-0596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adekola K, Rosen ST, Shanmugam M. Glucose transporters in cancer metabolism. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:650–654. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328356da72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu TQ, Fan J, Zhou L, Zheng SS. Effects of suppressing glucose transporter-1 by an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide on the growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:72–77. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Medina RA, Owen GI. Glucose transporters: expression, regulation and cancer. Biol Res. 2002;35:9–26. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602002000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Szablewski L. Expression of glucose transporters in cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1835:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bartrons R, Caro J. Hypoxia, glucose metabolism and the Warburg’s effect. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2007;39:223–229. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meijer TW, Kaanders JH, Span PN, Bussink J. Targeting hypoxia, HIF-1, and tumor glucose metabolism to improve radiotherapy efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5585–5594. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Horsman MR. Measurement of tumor oxygenation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:701–704. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Leninger A, Nelson DL, Cox MM. Water: Its Effect on Dissolved Biomolecules. 2nd ed. New York: Worth Publishers; 1993. Principles of biochemistry; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim MK, Kim TJ, Sung CO, Choi CH, Lee JW, Kim BG, Bae DS. High expression of mTOR is associated with radiation resistance in cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2010;21:181–185. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2010.21.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]