Abstract

Interferons (IFNs) are low molecular weight cell-derived proteins that include the type I, II, and III IFN families. IFNs are critical for an optimal immune response during microbial infections while dysregulated expression can lead to autoimmune diseases. Given its role in disease, it is important to understand cellular mechanisms of IFN regulation. 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTRs) have emerged as potent regulators of mRNA and protein dosage and are controlled through multiple regulatory elements including adenylate uridylate (AU)-rich elements (AREs) and microRNA (miRNA) recognition elements. These AREs are targeted by RNA-binding proteins (ARE-BPs) for degradation and/or stabilization through an ARE-mediated decay process. miRNA are endogenous, single-stranded RNA molecules ∼22 nucleotides in length that regulate mRNA translation through the miRNA-induced silencing complex. IFN transcripts, like other labile mRNAs, harbor AREs in their 3′ UTRs that dictate the turnover of mRNA. This review is a survey of the literature related to IFN regulation by miRNA, ARE-BPs, and how these complexes interact dynamically on the 3′ UTR. Additionally, downstream effects of these post-transcriptional regulators on the immune response will be discussed. Review topics include past studies, current understanding, and future challenges in the study of post-transcriptional regulation affecting IFN responses.

Introduction

microRNA-mediated regulation and the immune system

Regulation of gene expression by noncoding RNAs has revealed a new dimension of post-transcriptional regulation. Among the noncoding RNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs) are a major class of endogenous small RNAs that have emerged as potent regulators of gene expression. miRNAs are endogenous, single-stranded RNA molecules 21–23 nucleotides in length that regulate their target mRNAs by loading them onto the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC, Fig. 1) (Lau and others 2001; Lee and Ambros 2001). This process results in gene silencing by suppressing translation and/or degrading mRNA. A conservative estimate is that 30% of all genes are regulated by miRISC. Cell proliferation, cell death, fat metabolism, granulopoesis, heart development, and hematopoietic differentiation are a few of the processes that miRNAs are known to affect (Lodish and others 2008).

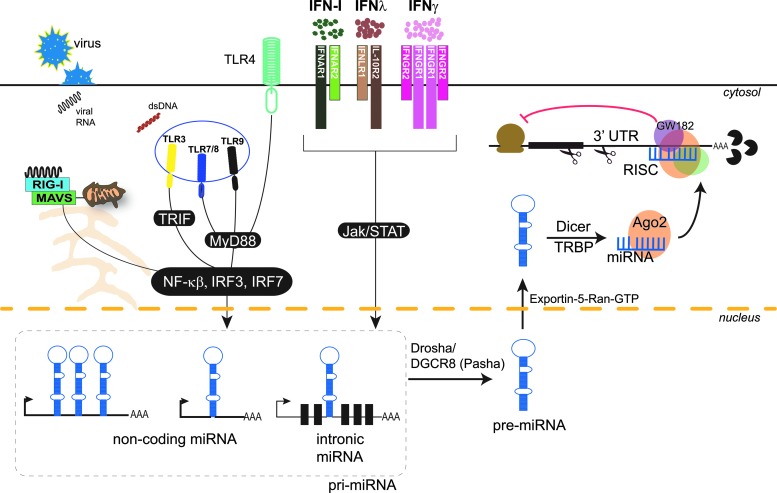

FIG. 1.

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) and IFNs modulate the expression of miRNAs. Pattern recognition receptors (RLRs, TLR3, 4, 7, 8, and 9) sense microbial PAMPs, activating signaling cascades, which induce transcription factors such as NFκB, IRF3, and IRF7. These transcription factors when activated translocate into the nucleus and based on sequence specificity bind to the promoters and initiate transcription of miRNAs. Type I, II, and III IFNs signal through their specific receptors: IFNαβR (composed of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 subunits), IFNγR (composed of IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 subunits), and IFNλR (composed of IFNLR1 and IL-10R2 subunits) respectively–to activate Jak/STAT signaling pathways. Phosphorylated STAT proteins translocate into the nucleus and bind to promoters containing GAS (IFN-γ) or ISRE (type I IFNs and IFNλs) sequences, initiating transcription of primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) encoded in noncoding genes or introns of coding or noncoding genes. The pri-miRNA transcript is then processed to precursor hairpin (pre-miRNA) by the microprocessor complex Drosha–DGCR8. The pre-miRNA is exported from the nucleus by Exportin-5–Ran-GTP into the cytoplasm, where it is cleaved by Dicer and TRBP into mature miRNA. The mature miRNA is loaded on Ago2 and guided to the target mRNA(s) to further recruit other proteins forming the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). This complex then mediates silencing of the gene through mRNA cleavage, translational repression, or deadenylation. RLRs, RIG-I-like receptors; RIG-I, retinoic acid-inducible gene 1; TLR, Toll-like receptor; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; IRF, interferon regulatory factor; Jak, Janus kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; GAS, IFN-gamma-activated sequence; ISRE, IFN-sensitive response element; MAVS, mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein; TRIF, TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing IFN-β; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex; Ago2, Argonaute-2; TRBP, TAR RNA-binding protein; MyD88, myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88.

miRNAs play an important role in host immunity. miRNAs are known to regulate genes important in immune cell lineage decisions, innate immune responses including microbial recognition, cytokine expression, and adaptive immune responses, which highlights the importance of miRNAs in immune modulation. Taganov and others (2007) have shown that several miRNAs act to negatively regulate the expression of Toll-like receptors (TLRs), a family of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize microbial products of bacterial, viral, and fungal origin to initiate an innate immune response. Tight regulation of TLR signaling, in part by miRNAs, is necessary to prevent undesirable inflammation (Taganov and others 2007). miRNAs also exert direct effects on adaptive immune responses. For instance, miRNAs are necessary for normal B-cell development, antibody diversity, T-cell development, T-helper cell differentiation, and cytokine production, as has been demonstrated in mice that lack Dicer, an enzyme necessary to process mature miRNA (Muljo and others 2005; Otsuka and others 2007). The 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTRs) of cytokines including IL10, IL6, IFNG, TNFA, IL13, and IL17 all contain miRNA recognition elements (MREs) and are targets of the miRISC (Asirvatham and others 2008, 2009). Additionally, host miRNAs are also involved in antiviral immunity by targeting viral genomes (Hariharan and others 2005; Lecellier and others 2005; Scaria and others 2006; Song and others 2010). Indeed, loss of Dicer causes hypersusceptibility to viral infections (Otsuka and others 2007). Likewise, viruses have evolved to control antiviral immune genes using virus-derived miRNAs termed “viral miRs” (Cullen 2006). Host-viral miRNA interactions are discussed in a greater detail in a review by Michael David (2010).

ARE-mediated decay and the immune system

Post-transcriptional control of gene expression involves factors that determine the translational capacity of an mRNA transcript. Adenylate uridylate (AU)-rich elements (AREs) encoded in the 3′ UTR of mRNA are one of the most potent cis-acting determinants of rapid mRNA turnover in mammalian cells. AREs vary in size (40–150 nt) and sequence but generally consist of one or more AUUUA pentamers in an AU-rich tract (Gillis and Malter 1991; Asson-Batres and others 1994; Chen and Shyu 1995). mRNA turnover mediated by AREs is usually characterized by binding of an RNA-binding protein (RNA-BP) to AREs and rapid 3′ to 5′ shortening of the poly(A) tail followed by decay of the mRNA. This process is called ARE-mediated decay (AMD). Conversely, RNA-BP interactions can also result in mRNA stabilization. ARE-BPs known to target immune genes include ARE poly-U-binding degradation factor-1 (AUF1), HuR, KH-type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP), nucleolin, and ZFP36 (also known as tristetraprolin, TTP). AUF1, TTP, KSRP, and TIA-1 have been shown to destabilize mRNA, while several factors from the HuR family can increase mRNA stability.

Compared with miRISC-mediated decay, AMD is a more robust means of post-transcriptional regulation. Accordingly, AREs are present in the 3′ UTRs of around 8% of all genes, with enrichment for genes important in immunity, such as those that encode inflammatory mediators, cytokines, oncoproteins, and G protein-coupled receptors (Gillis and Malter 1991). Many IFNs, including family members of type I, II, and III IFNs, encode functional AREs that allow tight temporal translational control of these cytokines. Deletion of certain ARE-BPs known to target cytokines can have significant deleterious effects leading to immune pathologies. TTP−/− (knockout) mice, which appear normal at birth, develop spontaneous inflammatory arthritis, dermatitis, cachexia, autoimmunity, and myeloid hyperplasia (Taylor and others 1996). TTP−/− mice also produce high levels of IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ compared with the wild-type littermate controls.

As IFN mRNAs are targets of both ARE-BPs and miRNAs, it is necessary to determine whether interactions exist between these complexes, which may result in a concerted post-transcriptional regulation. Only a few groups have reported on these complex scenarios. For instance, Joan Steiz's group showed that miRNAs can upregulate gene expression of TNF-α (Vasudevan and others 2007). There are several additional reports, including one on IL-10 (Ma and others 2010), which show miRNA-induced stability. In this review, I will present the current status of our understandings of post-transcriptional regulation of type I, II, and III IFNs.

Type I IFNs

Type I IFNs are a family of genes that exhibit potent antiviral activities (Isaacs and Lindenmann 1957; Isaacs and others 1957; Nagano and Kojima 1958; Vilcek and Jahiel 1970). In humans and mice, the type I IFN family is composed of IFNA (14 subtypes), IFNB, IFNK, IFNW, IFNT, and IFNE [reviewed by Pestka (2007)]. IFN-α/β specifically produced upon detection of microbial particles by innate PRRs has potent antiviral and antibacterial effects (Fig. 2). Upon secretion, type I IFNs signal through the nearly ubiquitously expressed heterodimeric IFNα/β receptor composed of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2. Binding of type I IFNs to IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 leads to expression of hundreds of antiviral genes, including MXA, OAS1, and ISG15 and type I IFN-specific transcription factor IRF-7. Recently, it has been shown that IFN-β can signal through IFNAR1 independent of IFNAR2, and it can initiate a noncononical signaling pathway that modulates expression of a distinct set of genes (de Weerd and others 2013). Thus, our understanding of IFN signaling pathways and IFN-stimulated genes continues to expand.

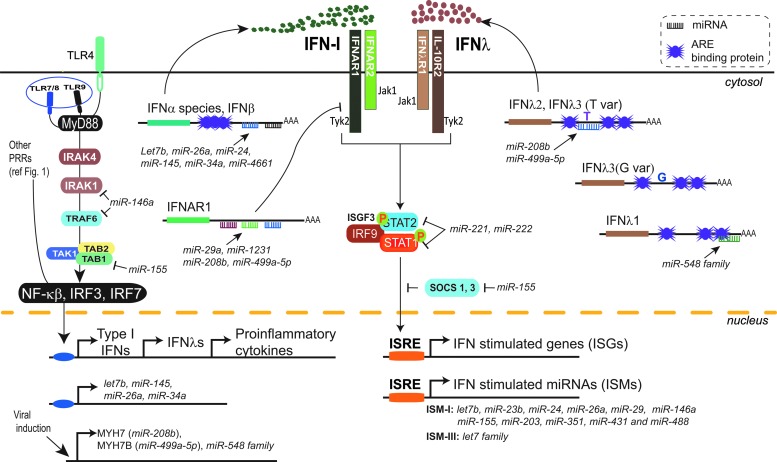

FIG. 2.

Expression and signaling of type I and III IFNs are modulated by miRNA and AU-rich element (ARE)-binding proteins (ARE-BPs). Type I and III IFNs and specific miRNAs are induced by pattern recognition receptors sensing microbial PAMPs (more details in Fig. 1). Type I and III IFNs signal in an autocrine and paracrine fashion to activate Jak/STAT proteins upon engagement of IFNαβ receptor (composed of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 subunits) and IFNλ receptor (composed of IFNLR1 and IL-10R2 subunits) respectively. Phosphorylation of the receptor will lead to the recruitment and activation of the ISGF3 complex comprising STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 proteins. The phosporylated ISGF3 complex translocates into the nucleus and binds to promoters containing ISRE sequences, activating transcription of ISGs and miRNAs. miRNAs inhibit the transcription of type I and III IFN genes by targeting the 3′ UTR of genes downstream of MyD88 signaling pathway (IRAK1, TRAF6, and TAB). Type I and III IFN transcripts, besides being miRNA targets themselves, harbor AREs in their 3′ UTR, which recruit ARE-BPs involved in post-transcriptional regulation. Lastly, IFN signaling is suppressed by miRNAs, which target the 3′ UTRs of IFNAR1, STAT1, and STAT2 genes. In contrast, miR-155 increases type I and III IFN signaling by downregulating SOCS1, which is a negative regulator of JAK/STAT signaling. ISGF3, interferon-stimulated gene factor 3; SOCS1, suppressor of cytokine signaling; IRAK, interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase; TRAF, TNF receptor-associated factor; TAK, TGF-beta-activated kinase; TAB, TAK-binding protein.

IFN-α/β is central to innate and adaptive immune defenses against viral and bacterial infections. IFNAR1−/− mice are unable to control or clear viral infection (Gil and others 2001; Gonzalez-Navajas and others 2012). Major producers of type I IFNs include plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), which constitutively express high levels of TLR7 and TLR9, PRRs that recognize ssRNA and CpG motifs in DNA, respectively(Krug and others 2001; Gibson and others 2002; Hubert and others 2004). pDCs detect nucleic acid pathogen-associated molecular patterns and initiate antiviral resistance in surrounding cells through the ample release of IFN-α/β. IFNs produced by pDCs in response to innate viral detection also act in an autocrine fashion to amplify production in a positive feedback loop (Asselin-Paturel and others 2005; Bao and Liu 2013). While the type I IFN response is paramount to achieving sustained immunological response during viral infection, one of the major challenges in clearing viral infections is mounting a rapid and robust type I IFN response without eliciting damaging inflammation given the ubiquitous expression of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2. Therefore, it is critical to identify factors that affect the type I IFN response to control it tightly and reduce its side effects. Understanding the regulation of type I IFN activity will provide insights into type I IFN-mediated autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematous. Technical challenges limit our ability to measure expression of various subtypes of type I IFN in vivo, so in vitro systems using cell lines are currently the standard in such research efforts.

ARE-mediated decay of type I IFNs

Regulation of IFN-β by post-transcriptional suppression was postulated as early as 1969 by Jan Vilcek (Vilcek and others 1969; Vilcek and Ng 1971; Vilcek and Havell 1973). This was based on the surprising observation that IFN-β produced upon TLR3 stimulation (using the synthetic ligand PolyI:C) increased in the presence of translation inhibitors like cyclohexamide compared with untreated cells. Later, several groups documented that the increase in IFN-β levels was as a result of stabilization of IFNB mRNA. More extensive analyses have revealed that IFNB mRNA stability is mediated by AMD via AREs present in the 3′ UTR and in the coding region (Whittemore and Maniatis 1990; Paste and others 2003). However, the specific proteins involved in the AMD of IFNB mRNA remain unidentified.

Type I IFNs regulation by miRNAs

There are only a few reports available of miRNA regulating the 3′ UTRs of type I IFN and majority of them focus on IFNA/B. Witwer and others (2010) identified Poly(I:C)-stimulated miRNAs let7b, miR-145, miR-26a, and miR-34a as regulators of IFNB in human and macaque monocyte-derived macrophages. Interestingly, these miRNAs repress IFNB gene expression and protein output, thereby modulating IFN production in response to TLR3 stimulation. miR-4661, which was initially reported to target ARE motifs in the IL10 gene has subsequently been reported to target 3′ UTRs of 9 IFNA species (IFNA1, IFNA2, IFNA4, IFNA8, IFNA10, IFNA13, IFNA18, IFNA17, and IFNA21) (Li and others 2012). Overexpression of miR-4661 in human macrophages led to robust downregulation of IFNA gene expression in a subtype-specific manner. However, the physiological importance of this regulation remains to be demonstrated as miR-4661 is not expressed or is expressed at very low levels in macrophages and dendritic cells.

Transcriptional control of type I IFN gene expression by miRNAs

In addition to targeting IFN directly, miRNAs have also been implicated in repressing the signaling components involved in type I IFN induction (Fig. 2). miR-155 regulates type I IFN induction by targeting the 3′ UTRs of TAB (TAK1 binding protein), Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase -M (IRAK-M), and SOCS1 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 1) genes (Zhou and others 2010; El-Ekiaby and others 2012; Zhang and others 2012). miR-146a has also been reported to inhibit type I IFN by blocking the upstream signaling components TRAF6 (TNF receptor-associated factor 6), IRAK1, and IRAK2 (Tang and others 2009). In support of a physiological role for miR-146 in modulating type I IFN, miR-146 expression was decreased in SLE patients compared with controls and was associated with increased type I IFN expression (Tang and others 2009).

miRNA regulation of IFN receptor and its downstream signaling genes

A less well-understood phenomenon is the effect of viral infection on the surface expression of IFN receptor. Functional IFNAR is necessary for type I IFN signaling and antiviral activity during infection. After type I IFN binds to IFNAR and activates Jak/STAT signaling, the receptor is endocytosed and degraded, resulting in a transient decrease in per cell receptor density. Interestingly, recycling or replenishment of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 on cellular surface following IFN treatment occurs at different rates for the 2 subunits. Several studies have reported that IFNAR1 mRNA levels are reduced in many viral infections; however, the mechanisms behind this reduction are still largely unknown [reviewed by Taylor and Mossman (2013)].

miRNA targeting of IFNAR1 has been reported in different cellular and disease contexts (Fig. 2). In mice thymic epithelium, miR-29a is reported to target IFNAR1 3′ UTR. Dicer−/− and/or miR-29a−/− mice exhibited thymic atrophy, which was attributed to increased surface expression and signaling of IFNAR (Papadopoulou and others 2012). In a different study, a genetic association revealed that a polymorphism (rs17875871) in the 3′ UTR of IFNAR1 associates with progression to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Han Chinese population. Heterozygous 4 bp deletion (del)/insertion (ins) and the del/del homozygous genotypes confer significantly higher risks of HCC and more pronounced disease in patients with hepatitis B virus infection (Zhou and others 2012). Based on RNA hybrid analysis, the 4 bp del variant creates a miRNA recognition element (MRE) for miR-1231 on the IFNAR1 3′ UTR. The authors therefore predict that miR-1231 downregulates IFNAR1 expression in 4 bp del/del or del/ins variants, which associates with progression to HCC. However, more direct functional studies are needed to prove this. It would be interesting to examine this polymorphism in other cohorts and investigate the expression of miR-1231 in hepatocytes. In work from my lab, we have shown that the hepatitis C virus (HCV) induces 2 miRNAs, miR-208b, and miR-499a-5p, which target the IFNAR1 3′ UTR leading to a substantial loss of IFNAR1 protein expression [McFarland and others (2014); Jarret and Savan, unpublished observation]. Further, this decrease in IFNAR1 has a significant negative impact on Jak/STAT signaling and ISG expression. We also have found that specific inhibition of miR-208b and miR-499a-5p during in vitro HCV infection is sufficient to rescue IFNAR1 levels and propagate a more robust antiviral response (unpublished observations). Therefore, inhibition of miR-208b and miR-499a-5p has therapeutic potential to increase expression of IFNAR1 during infection with HCV leading to an improved host response to endogenous type I IFN and recombinant peg-IFN-α used in standard therapy.

Several studies have identified components downstream of IFNAR signaling that are also targeted by miRNAs. miR-221 and miR-222 reduce gene and protein expression of STAT1 and STAT2 in response to IFN-α (Zhang and others 2010). In a recent study, miR-155 was reported to modulate CD8+ T cell responses to viral and bacterial infections (Gracias and others 2013). The authors showed that while overexpression of miR-155 increased antiviral responses, ablation of miR-155 lead to enhanced type I IFN signaling and antiproliferative effects in CD8+ T-cells. Although the specific targets of miR-155 were not identified, the effect on type I IFN signaling and antiproliferative genes was robust.

Type II IFN

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is the only member of type II IFN or immune IFN involved in host immune responses against microbial infections and tumor malignancies. The major IFN-γ-producing cell types are T-cells, natural killer (NK) and NKT-cells, γδ T-cells (Fig. 3). Neutrophils, trophoblasts, B-cells, macrophages, monocytes and dendritic cells (DC) are also reported to express IFNG mRNA upon stimulation; however the physiological relevance and levels of protein produced by these cells is unclear. Induction of IFN-γ provides protection against infectious agents and cancer, while aberrant overexpression is associated with autoinflammatory and autoimmune disorders. IFN-γ exerts effects on virtually all immune cells including monocyte, macrophages, T-cells, B-cells, NK cells, and neutrophils. IFN-γ-treated T-cells are polarized to a T-helper 1 (Th1) phenotype, whereas in B-cells IFN-γ induces immunoglobulin class switching along with interleukin-12 (IL-12) production.

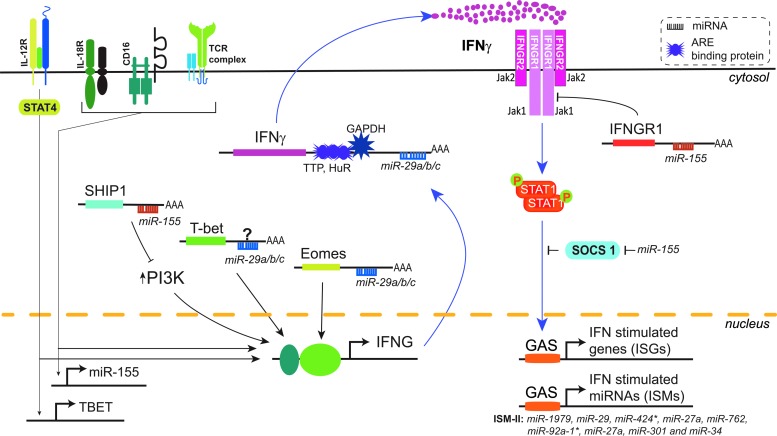

FIG. 3.

IFN-γ gene expression and signaling are modulated by miRNAs and ARE-binding proteins. IFN-γ is primarily induced in NK and T cells by multiple stimuli including cytokine ligation and TCR engagement. Induction of IFN-γ is mediated by several transcription factors including T-bet, Eomes, and PI3K. IFN-γ signals in an autocrine or paracrine fashion on all nucleated cells by activating JAK1 and JAK2 upon engagement of IFN-γ-receptor (IFNGR, composed of IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 subunits). Phosphorylation of the IFN-γ-receptor by JAK1/2 leads to the recruitment and activation of STAT1. Homodimers of phosporylated STAT1 translocate into nucleus and bind to GAS sequences in the promoters of ISGs and miRNAs to activate their transcription. The 3′ UTR of IFN-γ contains AREs that alter mRNA stability by recruiting ARE-BPs such as TTP, HuR, and GAPDH. miR-29 and miR-155 have also been extensively implicated in modulating transcription, post-transcription events, and signaling of IFN-γ. miR-29, a highly expressed miRNA in immune cells, regulates IFN-γ expression by targeting the 3′ UTR of a transcription factor Eomes. In contrast, miR-155 induced by IL-18, CD16, and TCR stimulation enhances IFN-γ expression by downregulating SHIP1, a negative regulator of PI3K. miR-155 has been reported to have both positive and negative regulatory effects on IFN-γ signaling, while miR-155 suppresses IFN-γ mediated signaling by targeting the 3′ UTR of IFNGR1 and decreasing surface expression of IFN-γ-receptor; it can augment IFN-γ-mediated signaling by downregulating SOCS1, negative regulator of Jak/STAT signaling pathway. Jak, Janus kinase; TTP, tristetraprolin; HuR, Hu-Antigen R; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Eomes, eomesodermin; IL-18, interleukin 18; CD, cluster of differentiation; TCR, T-cell receptor; SHIP1, phosphatidylinositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Numerous studies have revealed that IFN-γ promotes host responses for antitumor immunity. IFN-γ is known to play a significant role in all 3 phases of cancer immunoediting: elimination, equilibrium, and escape [reviewed by Dunn and others (2006)]. Studies have shown that IFN-γ has direct antiproliferative, apoptotic, and antiangiogenic effects on tumor cells in addition to indirect effects on antitumor immunity (Ikeda and others 2002). In addition, IFN-γ has been shown to be a critical factor in enhancing metastasis of the tumor (Pulaski and others 2002). IFN-γ produced in the tumor microenvironment could promote tumor growth and metastasis by acting on tumor-infiltrating hematopoietic cells that bear IFN-γ receptors (Bach and others 1997) or perhaps directly on the tumor. Pleiotropic effects of IFN-γ on immune development and diseases demonstrate that it is quite dire to have precise control over the level of IFN-γ.

ARE-mediated decay of IFNG

The 3′ UTR of the IFNG gene is the most highly studied among interferons. The IFNG 3′ UTR contains a number of conserved noncoding sequences (CNSes), including a 160 bp AU-rich region, which plays a major regulatory role by binding to miRNAs and AU-rich binding proteins. As the IFNG CNSes are common between species this suggests they are biologically important (Savan and others 2009). Initial studies on the IFNG post-transcriptional regulation focused on the 160 bp AU-rich region, which occupies almost a third of the 3′ UTR (Fig. 3). Perry Blackshear's group discovered that TTP (ZFP36) destabilizes IFNG mRNA by targeting the AU-rich region of the 3′ UTR. TTP binds with high affinity to a conserved 18 nt AU motif in the IFN-γ 3′ UTR, which plays a major role in the destabilization of the mRNA (Ogilvie and others 2009). They further showed TTP−/− mice produced higher levels of IFN-γ in NK and T-cells. Based on motif and evolutionary analysis, other ARE-binding proteins such as HuR have been proposed to also regulate the IFNG 3′ UTR; however, these data need to be supported by biochemical studies. Howard Young's group has deleted the entire AU-rich region in the IFNG 3′ UTR in mice and found that these mice produce chronic low-level IFN-γ leading to severe immune dysregulation and a lupus-like phenotype (personal communication with Howard Young, Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research). Chronic production of IFN-γ as a result of the AU-rich region deletion also leads to anaplastic anemia by interfering with the generation of common myeloid progenitors and disrupting erythropoiesis, in addition to B-cell lineage differentiation (personal communication with Howard Young). These data confirm that the ARE in the IFNG 3′ UTR plays a major role in the post-transcriptional regulation of IFN-γ and subsequent immune response. A recent study has linked the translational control of IFN-γ during T-cell activation to GAPDH binding to the IFNG 3′ UTR (Chang and others 2013). The authors demonstrate that during T-cell activation in the absence of aerobic glycolysis, these cells make less IFN-γ protein because GAPDH binds to the AU-rich region of 3′ UTR of IFNG. It would be interesting to test whether GAPDH recognizes a specific motif(s) within the ARE region and/or whether GAPDH interacts with TTP or miR-29 (discussed in the next section) during aerobic glycolysis.

miRNA-mediated regulation of IFNG

Most studies that report on miRNA regulation of IFNG have focused on the role of miR-29, as the 3′ UTRs of human and murine IFNG harbor a conserved miR-29 MRE (Fig. 3). Two groups reported that miR-29 degrades murine IFNG mRNA (Ma and others 2011; Smith and others 2012), while Mark Ansel's group did not observe miR-29 having a direct effect on IFNG mRNA (Steiner and others 2011). One study that observed repressive effects of miR-29 used a partial IFNG 3′ UTR (Smith and others 2012). However, these studies did not investigate post-transcriptional regulation of IFNG 3′ UTR in the context of both AMD and miRISC-mediated decay mechanisms in determining IFNG expression. To address the role of AMD in IFNG regulation, a recent study from the Abbas group studied the expression of ARE and non-ARE portions of murine IFNG 3′ UTR (Villarino and others 2010). In this study, they show that the IFNG 3′ UTR containing AREs tagged to green fluorescent protein (GFP; 1 to 279 nts from the stop codon) had lower expression than the non-ARE region of the 3′ UTR, which contains the miR-29a binding site. Thus, the authors conclude that IFN-γ expression is primarily determined by the ARE region and not miR-29. In support of this finding Blackshear's group also saw increased expression of murine IFN-γ in TTP−/− mice, which further supports that miR-29 by itself does not cause significant degradation of the IFN-γ mRNA in the absence of AMD (Ogilvie and others 2009).

We have been interested in studying the relationship between miR-29a regulation and AMD of IFNG. We designed experiments to maintain the native structural integrity of the 3′ UTR, as secondary structure is known to dictate access of regulatory proteins to post-transcriptional elements (Meisner and others 2004; Chen and others 2006). In our studies using the full-length IFNG 3′ UTR, we found that miR-29 stabilizes the IFNG transcript, which is contrary to previous studies using a partial 3′ UTR (Savan and Young, unpublished observations). To validate this finding and demonstrate the importance of studying the full-length IFNG 3′ UTR, we performed luciferase experiments using a partial 3′ UTR, which contains the miR-29 site but not the ARE region. This partial 3′ UTR construct had higher luciferase activity than the full-length 3′ UTR demonstrating AMD is occurring in the full-length but not partial 3′ UTR. Further, overexpression of miR-29 with the partial 3′ UTR resulted in decreased luciferase protein expression, which is opposite to the stabilization effect we observed when miR-29 is expressed with the full-length 3′ UTR (unpublished observations). Such findings highlight the importance of using full-length 3′ UTR constructs with a preserved secondary structure when studying post-transcriptional gene regulation.

miRNA regulation of IFNG transcription

IFNG expression is induced by several transcriptional factors such as T-bet, STAT4, and Eomesodermin (Eomes) in collaboration with chromatin rearrangement (Fig. 3). These activating and inhibitory epigenetic controls are in place to ensure cell-specific expression of IFN-γ during infection [reviewed by Young and Bream (2007)]. Mark Ansel's group found that IFNG 3′ UTR expression is indirectly regulated by miR-29 targeting TBX21 (T-bet) and EOMES (Steiner and others 2011). In addition, Trotta and others (2012) showed that inositol phosphatase SHIP1, which negatively regulates transcription of IFNG, is post-transcriptionally controlled by miR-155 in a series of elegant overexpression and knockdown studies of miR-155 in an NK cell line. Overexpression of miR-155 enhanced IFN-γ production by cytokine stimulation or CD16 receptor cross-linking, whereas knockdown of miR-155 or its disruption suppressed IFN-γ induction.

miRNA regulation of IFNG receptor and downstream signaling

IFN-γ signals through a private receptor complex comprised of IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 that activates the Jak/STAT pathway. Banerjee and others (2010) show that miR-155 is induced upon T-cell activation and that it promotes Th1 differentiation when overexpressed in activated CD4+ T-cells. They functionally validated a predicted miR-155 MRE within the 3′ UTR of IFNGR1 by showing inhibition of miR-155 leads to higher surface expression of IFN-γRα. This work identifies a novel role for miR-155 in Th1 differentiation through inhibition of IFN-γ signaling. Thus, IFN-γ expression is tightly regulated at multiple steps, clearly demonstrating the importance of post-transcriptional regulation of this signaling pathway. However, the differences in regulation observed by various groups could be attributed to cell-specific effects and the models used. Clearly, more studies are warranted to parse out the miRNA and ARE effects in IFN-γ regulation.

Type III IFNs (also called IFN lambda)

Type III IFNs, comprised of IFNL1 (IFN lambda, IL29), IFNL2 (IL28A), IFNL3 (IL28B), and IFNL4 are the most recent IFN family to be discovered (Sheppard and others 2003; Fox and others 2009; Prokunina-Olsson and others 2013). Although these molecules were initially described as interleukins, they share greater functional similarity with type I IFNs (Dumoutier and others 2004). Similar to type I IFNs, IFN-λ proteins are secreted by a range of cells including hepatocytes, monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs), and pDCs during viral infection (Donnelly and Kotenko 2010). IFN-λ signals through a heterodimer of IFN-λ private receptor IFNλR1 along with common receptor chain IL-10R2 (Fig. 2). IFN-λs have similar bio-activities as type I IFN whereby they activate a similar repertoire of antiviral IFN-stimulated genes downstream of Jak1, TYK2, STAT1, and STAT2. However, unlike type I IFN, IFN-λs have restricted effects on certain cell types as IFNλR1 expression is specific to cells of epithelial origin including gut, skin, and lung. Surprisingly, a recent study has shown that gut epithelial cells only harbor IFNLR but not IFNAR, indicating that IFN-λ may play a critical role in gut mucosal immunity to viruses (Pott and others 2011). The IFNL4 gene is the newest member of the IFNL family, but its functional significance is still unclear as IFN-λ4 protein is not efficiently secreted (Hamming and others 2013). The IFN-λ family has come into the spotlight since genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified polymorphisms in the IFNL3 gene locus with strong association to HCV clearance (Ge and others 2009).

ARE-mediated decay of IFN lambda genes

IFNL2 and IFNL3 share higher coding and 3′ UTR sequence similarity than they do to IFNL1, with both genes containing cis-acting repetitive AREs. To assess whether the AREs in the IFNL2 and IFNL3 3′ UTR are functionally active, we generated luciferase reporter constructs that had disrupted ARE motifs and measured luciferase expression in HepG2 cells, a hepatoma cell line. We found that disruption of the AREs rescued luciferase expression to the level of our luciferase control construct, demonstrating that the AREs in the IFNL2 and IFNL3 3′ UTRs are functional and mediate AMD of these cytokines (McFarland and others 2014). Using constructs containing the rs4803217 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP; which associates with clearance or persistence of HCV infection) of IFNL3 in its 3′ UTR, we observed a marked degree of differential expression between the IFNL3 variants in regards to mRNA stability and luciferase construct activity; this demonstrated a strong degradative mechanism acts on the IFNL3 3′ UTR variant that associates with HCV persistence. Mutations in the AREs in both IFNL3 3′ UTR variants resulted in increased luciferase expression, which showed equivalent rescue from AMD across genotypes.

miRNA regulation of IFN lambda genes

A recent study has shown miR-548 family (miR-548b-5p, miR-548c-5p, miR-548i, miR-548j, and miR-548n) targets IFNL1 mRNA (Li and others 2013) (Fig. 2). Further experiments showed miR-548 mimics promoted enterovirus-71 (EV71) and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection, while establishment of stable viral infection eventually suppresses miR-548 expression. This regulation suggests an important role for miR-548 during viral infection. It remains to be seen if this suppression is mediated by the host antiviral response or a viral antagonist and whether this process is physiologically relevant during infection.

GWAS have identified 3 SNPs near the gene encoding IFN lambda 3 (IFNL3, formerly IL28B) that affect the outcome of HCV infection by increasing responsiveness to antiviral therapy (Suppiah and others 2009; Tanaka and others 2009; Rauch and others 2010). IFN-λ3 has potent antiviral effects, including the ability to inhibit HCV replication (Friborg and others 2013). When paired with direct-acting antiviral agents, they have activity comparable to IFN-α in clearing HCV infection (Balagopal and others 2010; Friborg and others 2013). While several polymorphisms in close linkage disequilibrium have been investigated, the functional polymorphism mediating these associations with HCV clearance was only recently identified by my lab as rs4803217 located within the IFNL3 3′ UTR (McFarland and others 2014). This SNP (rs4803217) located in the 3′ UTR of the IFNL3 mRNA mediated the differences in expression between responsive (G/G) and nonresponsive (T/T) genotypes. We found that the G variant destroyed the MRE for 2 miRNAs (miR-208b and miR-499a-5p) that target the polymorphic region of the IFNL3 3′ UTR. We also found that the chronic HCV infection associated with high expression levels of these miRNAs in the liver of HCV patients. When we inhibited these specific miRNAs during in vitro HCV infection, we documented a significant increase in IFNL3 mRNA expression and a reduction in viral load in cells of the unfavorable IFNL3 3′ UTR (T/T) genotype. These observations indicate that the 3′ UTR SNP in IFNL3 directs HCV infection outcome through the control of IFNL3 mRNA stability (McFarland and others 2014).

The above studies clearly suggest that IFN-λs are important players in antiviral immunity. However, the identity of the ARE-BP(s) that targets IFNL and the role of AMD combined with miRNAs in controlling IFNL expression in steady state and during infection remains largely unknown.

miRNAs Controlling IFN-Stimulated Genes

ISGs induce an antiviral state to either kill an infected cell or render an uninfected cell refractory to viral infection. As ISGs are the first line of defense during viral infection, regulation of ISGs by the host or virus through miRNAs could have significant implications in the outcome of viral infection. The consequences of such regulation are shown in a study that reports HCV-mediated upregulation of a host miRNA, miR-130a, which dampens the ISG IFITM1 (Bhanja Chowdhury and others 2012). This study showed that inhibition of miR-130a could augment the antiviral response thus reducing HCV viral load through rescue of IFITM1 expression. In another study, miRNA profiling of Sendai virus-infected A549 cells showed that miR-203 is induced by type I IFN and regulates IFIT1/ISG56 (Buggele and Horvath 2013). miRNA controlling ISGs and their effects on antiviral response are discussed in much greater detail in an excellent recent review by Lisa Sedger (2013).

IFN-Stimulated miRNAs

Similar to the induction of ISGs by type I IFN, several miRNAs have been identified as IFN-inducible miRNAs (IFN-stimulated miRNAs, ISMs, (Fig. 1, 2)). Initial studies reported miR-155 as type I IFN-inducible miRNA (O'Connell and others 2007). During the same time, miR-351, miR-431, and miR-488 were found to be induced by type I IFN, which inhibited HCV replication (Pedersen and others 2007). Nathans and others (2009) discovered that miR-29 is an ISM that inhibits HIV replication by targeting the Nef gene in the HIV genome. In another study, miR-23b was found to act as an ISM that reduces rhinovirus infection by suppressing very low density lipoprotein receptor gene expression required for viral entry (Ouda and others 2011). However, type I IFN has also been shown to downregulate miR-122, which is an important positive regulator of HCV replication (Pedersen and others 2007; Sarasin-Filipowicz and others 2009; Gong and others 2010).

Although the above-mentioned studies have shown miRNA expression induced or inhibited by type I IFNs can modulate antiviral activities, it would be interesting to examine whether these miRNAs also possess other regulatory roles during infection. Such scenarios are beginning to be investigated such as in the case of miR-203, a type I ISM that regulates ISG56 during Sendai virus infection as mentioned in the previous section (Buggele and Horvath 2013). Witwer and others (2010) also identified let-7b, miR-26a, and miR-24 as ISMs, which in turn regulated IFNB expression. Another type I ISM, miR-146a, also participates in feedback inhibition of type I IFNs by downregulating TRAF6, IRAK1, and IRAK2 (Hou and others 2009).

There has only been one study on type II ISMs, which identified miR-1979, miR-29, miR-424*, miR-27a, miR-762, miR-92a-1*, miR-27a, miR-301, and miR-34 as being induced during IFN-γ stimulation (Reinsbach and others 2012). They also documented a robust downregulation of miR-27b, miR-99b*, and miR-574-3p during IFN-γ stimulation. The physiological effects of these miRNAs during IFN-γ activation remain to be investigated. Similarly, there is one report on type III ISMs, the let7 family, that attenuates HCV viral replication in vitro by reducing insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1, which is required for HCV replication (Cheng and others 2013).

Overall, these studies hint that ISMs might have antiviral properties in addition to their regulatory roles aimed at fine-tuning IFN expression and response. A greater effort to identify and catalog ISMs and to delete them specifically during infection will be necessary to further understand their effect on host immunity.

Concluding Remarks

In recent years there has been a growing interest to study the mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation that affect the IFN response, and we have just scratched the surface of this intricate regulation. However, it is safe to say miRNAs and ARE-BPs play a critical role in controlling the gene dosage of IFNs. Until now, the main areas of interests have been post-transcriptional regulation of IFN genes during infection, identification of interferon-induced miRNAs and their effect on disease outcomes, and understanding the role of host and viral-derived miRNAs on immunity.

Recent years have witnessed a rapid growth in tools available to study post-transcriptional gene regulation. One of the challenges is the identification and functional validation of the miRNA(s) regulating the gene of interest. While bioinformatics analyses and precomputed MRE target sites are often useful in narrowing the search, it is still overwhelming to identify the specific miRNA(s) involved. Simple rules that can help further narrow the miRNA(s) of interest include (1) identifying genes potentially regulated by miRNAs based on discordant levels of mRNA compared to protein, (2) conservation of MREs in the 3′ UTR of interest during evolution, (3) common miRNAs identified by bioinformatics and in cell-specific expression, (4) validation of the specific MRE(s) by mutagenesis of seed regions in the MRE or miRNA overexpression or inhibition studies in luciferase/fluorescence 3′ UTR reporters constructs, and (5) inhibition of specific miRNA(s) in the cell-type of interest followed by measurement of gene and protein expression and other effects on cell-specific responses.

Generally, the approach taken to study post-transcriptional regulation of cytokines is to examine AMD or regulation by miRNA individually, rather than accounting for both pathways. I favor a model in which 3′ UTR regulation is viewed as a post-transcriptional “regulosome,” where interactions of various complexes are studied concurrently. Based on our and other studies, we now know that miRNA, ARE-BP, and the structure of the RNA together determine the stability of the transcript. miRNAs and ARE-BPs often act together in a synergistic or additive fashion to destabilize/degrade the mRNA. There are instances where the interaction of a miRNA and ARE-BP on the 3′ UTR could have an alternative outcome when there is competition for the target site or a change in the RNA structure that limits accessibility to the mRNA. Therefore, it is important to carry out post-transcriptional analysis of genes using the entire length of 3′ UTR (such as in 3′ UTR reporters) rather than taking the conventional approach used in promoter studies, where we serially remove the upstream sequence of a gene to investigate alterations in miRNA and ARE-BP binding. The interplay of the miRISC, ARE-BPs, and mRNA structure, among other factors, are controlled by cell cycle, metabolic state, cell-type, and activation status. Therefore, it is important to consider these contextual factors to fully understand the post-transcriptional regulation of a gene. Lastly, several studies have shown that SNPs can alter post-transcriptional regulation of genes. Polymorphisms in the 3′ UTR can often create or delete miRNA or ARE-BP sites that alter the 3′ UTR regulation of the gene (Kulkarni and others 2011; McFarland and others 2014). In some cases, polymorphisms can lead to a change in the RNA structure that alters the accessibility of post-transcriptional modulators (Chen and others 2006). IFNs are a perfect model to study the above mechanisms as they harbor AREs, MREs, and often carry SNPs as they are subjected to pathogen pressure. The identification of the key post-transcriptional regulatory elements that control IFN expression has the potential to lead to novel therapeutic targets that can effectively control infections while minimizing damaging inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Department of Immunology, University of Washington (UW), UW Royalty Research Fund, and NIH grant 1R01AI108765-01 (R.S.). The author thanks Abigail Jarret, Rochelle C. Joslyn, Chrissie Lim, and Adelle P. McFarland for critical reading of the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

The author has no competing financial interests.

References

- Asirvatham AJ, Gregorie CJ, Hu Z, Magner WJ, Tomasi TB. 2008. MicroRNA targets in immune genes and the Dicer/Argonaute and ARE machinery components. Mol Immunol 45(7):1995–2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asirvatham AJ, Magner WJ, Tomasi TB. 2009. miRNA regulation of cytokine genes. Cytokine 45(2):58–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselin-Paturel C, Brizard G, Chemin K, Boonstra A, O'Garra A, Vicari A, Trinchieri G. 2005. Type I interferon dependence of plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation and migration. J Exp Med 201(7):1157–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asson-Batres MA, Spurgeon SL, Diaz J, DeLoughery TG, Bagby GC., Jr.1994. Evolutionary conservation of the AU-rich 3′ untranslated region of messenger RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91(4):1318–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach EA, Aguet M, Schreiber RD. 1997. The IFN gamma receptor: a paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling. Annu Rev Immunol 15:563–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagopal A, Thomas DL, Thio CL. 2010. IL28B and the control of hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology 139(6):1865–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Schambach F, DeJong CS, Hammond SM, Reiner SL. 2010. Micro-RNA-155 inhibits IFN-gamma signaling in CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol 40(1):225–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao M, Liu YJ. 2013. Regulation of TLR7/9 signaling in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Protein Cell 4(1):40–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanja Chowdhury J, Shrivastava S, Steele R, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray R, Ray RB. 2012. Hepatitis C virus infection modulates expression of interferon stimulatory gene IFITM1 by upregulating miR-130A. J Virol 86(18):10221–10225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggele WA, Horvath CM. 2013. MicroRNA Profiling of Sendai Virus-Infected A549 Cells Identifies miR-203 as an Interferon-Inducible Regulator of IFIT1/ISG56. J Virol 87(16):9260–9270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB, Faubert B, Villarino AV, O'Sullivan D, Huang SCC, van der Windt GJW, Blagih J, Qiu J, Weber JD, Pearce EJ, Jones RG, Pearce EL. 2013. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell 153(6):1239–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Shyu AB. 1995. AU-rich elements: characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem Sci 20(11):465–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JM, Ferec C, Cooper DN. 2006. A systematic analysis of disease-associated variants in the 3′ regulatory regions of human protein-coding genes II: the importance of mRNA secondary structure in assessing the functionality of 3′ UTR variants. Hum Genet 120(3):301–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M, Si Y, Niu Y, Liu X, Li X, Zhao J, Jin Q, Yang W. 2013. High-throughput profiling of alpha interferon- and interleukin-28B-regulated microRNAs and identification of let-7s with anti-hepatitis C virus activity by targeting IGF2BP1. J Virol 87(17):9707–9718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BR. 2006. Viruses and microRNAs. Nat Genet 38Suppl:S25–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David M. 2010. Interferons and microRNAs. J Interferon Cytokine Res 30(11):825–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weerd NA, Vivian JP, Nguyen TK, Mangan NE, Gould JA, Braniff SJ, Zaker-Tabrizi L, Fung KY, Forster SC, Beddoe T, Reid HH, Rossjohn J, Hertzog PJ. 2013. Structural basis of a unique interferon-beta signaling axis mediated via the receptor IFNAR1. Nat Immunol 14(9):901–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly RP, Kotenko SV. 2010. Interferon-lambda: a new addition to an old family. J Interferon Cytokine Res 30(8):555–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumoutier L, Tounsi A, Michiels T, Sommereyns C, Kotenko SV, Renauld JC. 2004. Role of the interleukin (IL)-28 receptor tyrosine residues for antiviral and antiproliferative activity of IL-29/interferon-lambda 1: similarities with type I interferon signaling. J Biol Chem 279(31):32269–32274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn GP, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD. 2006. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol 6(11):836–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ekiaby N, Hamdi N, Negm M, Ahmed R, Zekri AR, Esmat G, Abdelaziz AI. 2012. Repressed induction of interferon-related microRNAs miR-146a and miR-155 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells infected with HCV genotype 4. FEBS Open Bio 2:179–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox BA, Sheppard PO, O'Hara PJ. 2009. The role of genomic data in the discovery, annotation and evolutionary interpretation of the interferon-lambda family. PLoS One 4(3):e4933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friborg J, Levine S, Chen CQ, Sheaffer AK, Chaniewski S, Voss S, Lemm JA, McPhee F. 2013. Combinations of lambda interferon with direct-acting antiviral agents are highly efficient in suppressing hepatitis C virus replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57(3):1312–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, Heinzen EL, Qiu P, Bertelsen AH, Muir AJ, Sulkowski M, McHutchison JG, Goldstein DB. 2009. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 461(7262):399–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson SJ, Lindh JM, Riter TR, Gleason RM, Rogers LM, Fuller AE, Oesterich JL, Gorden KB, Qiu X, McKane SW, Noelle RJ, Miller RL, Kedl RM, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Tomai MA, Vasilakos JP. 2002. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce cytokines and mature in response to the TLR7 agonists, imiquimod and resiquimod. Cell Immunol 218(1–2):74–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil MP, Bohn E, O'Guin AK, Ramana CV, Levine B, Stark GR, Virgin HW, Schreiber RD. 2001. Biologic consequences of Stat1-independent IFN signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98(12):6680–6685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis P, Malter JS. 1991. The adenosine-uridine binding factor recognizes the AU-rich elements of cytokine, lymphokine, and oncogene mRNAs. J Biol Chem 266(5):3172–3177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong BD, Xie Q, Xiang XG, Wang L, Zhao GD, An FM, Wang H, Lin LY, Yu H, Bao SS. 2010. Effect of ribavirin and interferon beta on miRNA profile in the hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon-bearing Huh7 cells. Int J Mol Med 25(6):853–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E. 2012. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol 12(2):125–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracias DT, Stelekati E, Hope JL, Boesteanu AC, Doering TA, Norton J, Mueller YM, Fraietta JA, Wherry EJ, Turner M, Katsikis PD. 2013. The microRNA miR-155 controls CD8(+) T cell responses by regulating interferon signaling. Nat Immunol 14(6):593–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamming OJ, Terczynska-Dyla E, Vieyres G, Dijkman R, Jorgensen SE, Akhtar H, Siupka P, Pietschmann T, Thiel V, Hartmann R. 2013. Interferon lambda 4 signals via the IFNlambda receptor to regulate antiviral activity against HCV and coronaviruses. EMBO J 32(23):3055–3065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan M, Scaria V, Pillai B, Brahmachari SK. 2005. Targets for human encoded microRNAs in HIV genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 337(4):1214–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J, Wang P, Lin L, Liu X, Ma F, An H, Wang Z, Cao X. 2009. MicroRNA-146a feedback inhibits RIG-I-dependent Type I IFN production in macrophages by targeting TRAF6, IRAK1, and IRAK2. J Immunol 183(3):2150–2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert FX, Voisine C, Louvet C, Heslan M, Josien R. 2004. Rat plasmacytoid dendritic cells are an abundant subset of MHC class II+ CD4+CD11b-OX62- and type I IFN-producing cells that exhibit selective expression of Toll-like receptors 7 and 9 and strong responsiveness to CpG. J Immunol 172(12):7485–7494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. 2002. The roles of IFN gamma in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 13(2):95–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs A, Lindenmann J. 1957. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 147(927):258–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs A, Lindenmann J, Valentine RC. 1957. Virus interference. II. Some properties of interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 147(927):268–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug A, Towarowski A, Britsch S, Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, Bals R, Giese T, Engelmann H, Endres S, Krieg AM, Hartmann G. 2001. Toll-like receptor expression reveals CpG DNA as a unique microbial stimulus for plasmacytoid dendritic cells which synergizes with CD40 ligand to induce high amounts of IL-12. Eur J Immunol 31(10):3026–3037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Savan R, Qi Y, Gao X, Yuki Y, Bass SE, Martin MP, Hunt P, Deeks SG, Telenti A, Pereyra F, Goldstein D, Wolinsky S, Walker B, Young HA, Carrington M. 2011. Differential microRNA regulation of HLA-C expression and its association with HIV control. Nature 472(7344):495–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. 2001. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294(5543):858–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecellier CH, Dunoyer P, Arar K, Lehmann-Che J, Eyquem S, Himber C, Saib A, Voinnet O. 2005. A cellular microRNA mediates antiviral defense in human cells. Science 308(5721):557–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Ambros V. 2001. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294(5543):862–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Fan X, He X, Sun H, Zou Z, Yuan H, Xu H, Wang C, Shi X. 2012. MicroRNA-466l inhibits antiviral innate immune response by targeting interferon-alpha. Cell Mol Immunol 9(6):497–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Xie J, Xu X, Wang J, Ao F, Wan Y, Zhu Y. 2013. MicroRNA-548 down-regulates host antiviral response via direct targeting of IFN-lambda1. Protein Cell 4(2):130–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodish HF, Zhou B, Liu G, Chen CZ. 2008. Micromanagement of the immune system by microRNAs. Nat Rev Immunol 8(2):120–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F, Liu X, Li D, Wang P, Li N, Lu L, Cao X. 2010. MicroRNA-466l upregulates IL-10 expression in TLR-triggered macrophages by antagonizing RNA-binding protein tristetraprolin-mediated IL-10 mRNA degradation. J Immunol 184(11):6053–6059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F, Xu S, Liu X, Zhang Q, Xu X, Liu M, Hua M, Li N, Yao H, Cao X. 2011. The microRNA miR-29 controls innate and adaptive immune responses to intracellular bacterial infection by targeting interferon-gamma. Nat Immunol 12(9):861–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland AP, Horner SM, Jarret A, Joslyn RC, Bindewald E, Shapiro BA, Delker DA, Hagedorn CH, Carrington M, Gale M, Jr., Savan R. 2014. The favorable IFNL3 genotype escapes mRNA decay mediated by AU-rich elements and hepatitis C virus-induced microRNAs. Nat Immunol 15(1):72–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisner NC, Hackermuller J, Uhl V, Aszodi A, Jaritz M, Auer M. 2004. mRNA openers and closers: modulating AU-rich element-controlled mRNA stability by a molecular switch in mRNA secondary structure. Chembiochem 5(10):1432–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muljo SA, Ansel KM, Kanellopoulou C, Livingston DM, Rao A, Rajewsky K. 2005. Aberrant T cell differentiation in the absence of Dicer. J Exp Med 202(2):261–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano Y, Kojima Y. 1958. [Interference of the inactive vaccinia virus with infection of skin by the active homologous virus]. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil 152(2):372–374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathans R, Chu CY, Serquina AK, Lu CC, Cao H, Rana TM. 2009. Cellular microRNA and P bodies modulate host-HIV-1 interactions. Mol Cell 34(6):696–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. 2007. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(5):1604–1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie RL, Sternjohn JR, Rattenbacher B, Vlasova IA, Williams DA, Hau HH, Blackshear PJ, Bohjanen PR. 2009. Tristetraprolin mediates interferon-gamma mRNA decay. J Biol Chem 284(17):11216–11223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka M, Jing Q, Georgel P, New L, Chen J, Mols J, Kang YJ, Jiang Z, Du X, Cook R, Das SC, Pattnaik AK, Beutler B, Han J. 2007. Hypersusceptibility to vesicular stomatitis virus infection in Dicer1-deficient mice is due to impaired miR24 and miR93 expression. Immunity 27(1):123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouda R, Onomoto K, Takahasi K, Edwards MR, Kato H, Yoneyama M, Fujita T. 2011. Retinoic acid-inducible gene I-inducible miR-23b inhibits infections by minor group rhinoviruses through down-regulation of the very low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem 286(29):26210–26219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou AS, Dooley J, Linterman MA, Pierson W, Ucar O, Kyewski B, Zuklys S, Hollander GA, Matthys P, Gray DH, De Strooper B, Liston A. 2012. The thymic epithelial microRNA network elevates the threshold for infection-associated thymic involution via miR-29a mediated suppression of the IFN-alpha receptor. Nat Immunol 13(2):181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paste M, Huez G, Kruys V. 2003. Deadenylation of interferon-beta mRNA is mediated by both the AU-rich element in the 3′-untranslated region and an instability sequence in the coding region. Eur J Biochem 270(7):1590–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen IM, Cheng G, Wieland S, Volinia S, Croce CM, Chisari FV, David M. 2007. Interferon modulation of cellular microRNAs as an antiviral mechanism. Nature 449(7164):919–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestka S. 2007. Purification and cloning of interferon alpha. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 316:23–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pott J, Mahlakoiv T, Mordstein M, Duerr CU, Michiels T, Stockinger S, Staeheli P, Hornef MW. 2011. IFN-lambda determines the intestinal epithelial antiviral host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(19):7944–7949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokunina-Olsson L, Muchmore B, Tang W, Pfeiffer RM, Park H, Dickensheets H, Hergott D, Porter-Gill P, Mumy A, Kohaar I, Chen S, Brand N, Tarway M, Liu L, Sheikh F, Astemborski J, Bonkovsky HL, Edlin BR, Howell CD, Morgan TR, Thomas DL, Rehermann B, Donnelly RP, O'Brien TR. 2013. A variant upstream of IFNL3 (IL28B) creating a new interferon gene IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nat Genet 45(2):164–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulaski BA, Smyth MJ, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. 2002. Interferon-gamma-dependent phagocytic cells are a critical component of innate immunity against metastatic mammary carcinoma. Cancer Res 62(15):4406–4412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch A, Kutalik Z, Descombes P, Cai T, Di Iulio J, Mueller T, Bochud M, Battegay M, Bernasconi E, Borovicka J, Colombo S, Cerny A, Dufour JF, Furrer H, Gunthard HF, Heim M, Hirschel B, Malinverni R, Moradpour D, Mullhaupt B, Witteck A, Beckmann JS, Berg T, Bergmann S, Negro F, Telenti A, Bochud PY, Swiss Hepatitis CCS, Swiss HIVCS. 2010. Genetic variation in IL28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment failure: a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology 138(4):1338–1345, 1345 e1–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinsbach S, Nazarov PV, Philippidou D, Schmitt M, Wienecke-Baldacchino A, Muller A, Vallar L, Behrmann I, Kreis S. 2012. Dynamic regulation of microRNA expression following interferon-gamma-induced gene transcription. RNA Biol 9(7):978–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarasin-Filipowicz M, Krol J, Markiewicz I, Heim MH, Filipowicz W. 2009. Decreased levels of microRNA miR-122 in individuals with hepatitis C responding poorly to interferon therapy. Nat Med 15(1):31–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savan R, Ravichandran S, Collins JR, Sakai M, Young HA. 2009. Structural conservation of interferon gamma among vertebrates. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 20(2):115–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaria V, Hariharan M, Maiti S, Pillai B, Brahmachari SK. 2006. Host-virus interaction: a new role for microRNAs. Retrovirology 3:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedger LM. 2013. microRNA control of interferons and interferon induced anti-viral activity. Mol Immunol 56(4):781–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard P, Kindsvogel W, Xu W, Henderson K, Schlutsmeyer S, Whitmore TE, Kuestner R, Garrigues U, Birks C, Roraback J, Ostrander C, Dong D, Shin J, Presnell S, Fox B, Haldeman B, Cooper E, Taft D, Gilbert T, Grant FJ, Tackett M, Krivan W, McKnight G, Clegg C, Foster D, Klucher KM. 2003. IL-28, IL-29 and their class II cytokine receptor IL-28R. Nat Immunol 4(1):63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KM, Guerau-de-Arellano M, Costinean S, Williams JL, Bottoni A, Mavrikis Cox G, Satoskar AR, Croce CM, Racke MK, Lovett-Racke AE, Whitacre CC. 2012. miR-29ab1 deficiency identifies a negative feedback loop controlling Th1 bias that is dysregulated in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 189(4):1567–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Liu H, Gao S, Jiang W, Huang W. 2010. Cellular microRNAs inhibit replication of the H1N1 influenza A virus in infected cells. J Virol 84(17):8849–8860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner DF, Thomas MF, Hu JK, Yang Z, Babiarz JE, Allen CD, Matloubian M, Blelloch R, Ansel KM. 2011. MicroRNA-29 regulates T-box transcription factors and interferon-gamma production in helper T cells. Immunity 35(2):169–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, Bassendine M, Spengler U, Dore GJ, Powell E, Riordan S, Sheridan D, Smedile A, Fragomeli V, Muller T, Bahlo M, Stewart GJ, Booth DR, George J. 2009. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet 41(10):1100–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Baltimore D. 2007. MicroRNAs and immunity: tiny players in a big field. Immunity 26(2):133–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, Nakagawa M, Korenaga M, Hino K, Hige S, Ito Y, Mita E, Tanaka E, Mochida S, Murawaki Y, Honda M, Sakai A, Hiasa Y, Nishiguchi S, Koike A, Sakaida I, Imamura M, Ito K, Yano K, Masaki N, Sugauchi F, Izumi N, Tokunaga K, Mizokami M. 2009. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet 41(10):1105–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Luo X, Cui H, Ni X, Yuan M, Guo Y, Huang X, Zhou H, de Vries N, Tak PP, Chen S, Shen N. 2009. MicroRNA-146A contributes to abnormal activation of the type I interferon pathway in human lupus by targeting the key signaling proteins. Arthritis Rheum 60(4):1065–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GA, Carballo E, Lee DM, Lai WS, Thompson MJ, Patel DD, Schenkman DI, Gilkeson GS, Broxmeyer HE, Haynes BF, Blackshear PJ. 1996. A pathogenetic role for TNF alpha in the syndrome of cachexia, arthritis, and autoimmunity resulting from tristetraprolin (TTP) deficiency. Immunity 4(5):445–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KE, Mossman KL. 2013. Recent advances in understanding viral evasion of type I interferon. Immunology 138(3):190–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta R, Chen L, Ciarlariello D, Josyula S, Mao C, Costinean S, Yu L, Butchar JP, Tridandapani S, Croce CM, Caligiuri MA. 2012. miR-155 regulates IFN-gamma production in natural killer cells. Blood 119(15):3478–3485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. 2007. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science 318(5858):1931–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcek J, Havell EA. 1973. Stabilization of interferon messenger RNA activity by treatment of cells with metabolic inhibitors and lowering of the incubation temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 70(12):3909–3913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcek J, Jahiel RI. 1970. Action of interferon and its inducers aginst nonviral infectious agents. Arch Intern Med 126(1):69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcek J, Ng MH. 1971. Post-transcriptional control of interferon synthesis. J Virol 7(5):588–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcek J, Rossman TG, Varacalli F. 1969. Differential effects of actinomycin D and puromycin on the release of interferon induced by double stranded RNA. Nature 222(5194):682–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarino AV, Gallo E, Abbas AK. 2010. STAT1-activating cytokines limit Th17 responses through both T-bet-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Immunol 185(11):6461–6471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore LA, Maniatis T. 1990. Postinduction repression of the beta-interferon gene is mediated through two positive regulatory domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87(20):7799–7803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witwer KW, Sisk JM, Gama L, Clements JE. 2010. MicroRNA regulation of IFN-beta protein expression: rapid and sensitive modulation of the innate immune response. J Immunol 184(5):2369–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young HA, Bream JH. 2007. IFN-gamma: recent advances in understanding regulation of expression, biological functions, and clinical applications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 316:97–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Han L, Zhang A, Yang W, Zhou X, Pu P, Du Y, Zeng H, Kang C. 2010. Global changes of mRNA expression reveals an increased activity of the interferon-induced signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway by repression of miR-221/222 in glioblastoma U251 cells. Int J Oncol 36(6):1503–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhao H, Chen J, Xia B, Jin Y, Wei W, Shen J, Huang Y. 2012. Interferon-beta-induced miR-155 inhibits osteoclast differentiation by targeting SOCS1 and MITF. FEBS Lett 586(19):3255–3262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Yu Q, Chen L, Wang J, Zheng S, Zhang J. 2012. A miR-1231 binding site polymorphism in the 3′ UTR of IFNAR1 is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility. Gene 507(1):95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Huang X, Cui H, Luo X, Tang Y, Chen S, Wu L, Shen N. 2010. miR-155 and its star-form partner miR-155* cooperatively regulate type I interferon production by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood 116(26):5885–5894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]