Abstract

This study describes mobile food vendors (street vendors) in Bronx, NY, considering neighborhood-level correlations with demographic, diet, and diet-related health measures from City data. Vendors offering exclusively “less-healthy” foods (e.g., chips, processed meats, sweets) outnumbered vendors offering exclusively “healthier” foods (e.g., produce, whole grains, nuts). Wet days and winter months reduced all vending on streets, but exclusively “less-healthy” vending most. In summer, exclusively “less-healthy” vending per capita inversely correlated with neighborhood-mean fruit-and-vegetable consumption and directly correlated with neighborhood-mean BMI and prevalences of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia (Spearman correlations 0.90-1.00, p values 0.037 to <0.001). In winter, “less-healthy” vending per capita directly correlated with proportions of Hispanic residents and those living in poverty (Spearman correlations 0.90, p values 0.037). Mobile food vending may contribute negatively to urban food-environment healthfulness overall, but exacerbation of demographic, diet, and diet-related health disparities may vary by weather, season, and neighborhood characteristics.

Keywords: Mobile food vendors, Street foods, Food environment, Urban, Neighborhood, Disparities

INTRODUCTION

Most food-environment research to date has focused on proximity to and density of food stores and restaurants.(Kirkpatrick et al., 2010; McKinnon et al., 2009) Few studies have examined mobile food vending (e.g., roadside carts, trucks, and stands).(Abusabha et al., 2011; Lucan et al., 2011; Sharkey et al., 2012; Tester et al., 2010, 2012; Tester et al., 2011; Valdez et al., 2012; Widener et al., 2012) Studies in rural settings suggest that mobile vendors sell a limited range of mostly prepared foods, refined sweets, and salty snacks.(Sharkey et al., 2012; Valdez et al., 2012) Studies in urban settings suggest that mobile vendors offer various nutrient-poor, energy-dense options (Tester et al., 2010) and tend to locate around schools in lower-income neighborhoods.(Tester et al., 2011) Studies in both settings suggest that “healthier” options, like fruits and vegetables, are available from at least some vendors.(Abusabha et al., 2011; Lucan et al., 2011; Tester et al., 2010; Valdez et al., 2012; Widener et al., 2012)

Prior studies have generally not examined mobile vending on scales larger than just a few carts or considered the possible shifting nutritional contributions of vendors related to their mobility. Investigators in the current study sought to understand the variable contributions of mobile vendors to neighborhood food environments for an entire urban county; to understand where, when, and what vendors sell, and potential implications for community nutrition and health.

METHODS

With IRB approval, investigators conducted a primary assessment of mobile vending in the Bronx, also performing neighborhood-level correlations with demographic, diet, and diet-related health measures from the City. Vending vehicle (e.g., cart, truck, stand), not person selling, was the unit of observation and analysis.

Surveying streets

Two pairs of researchers systematically scanned streets for vending vehicles, assessing all streets at least once. Investigators covered all 42mi2 of Bronx County, NY during usual business hours, requiring a total of l40 weekdays summer-fall 2010.(Lucan et al., 2013)

Brief interviews

Investigators asked vendors about hours, days, months and locations for selling, and if weather is a factor. Specific questions are available in another publication.(Lucan et al., 2013)

Direct observations

Investigators made observations about the vending vehicle, including unique identifier (e.g., permit number, license plate, distinctive features) and location (i.e., nearest street address or street intersection). Investigators determined foods and beverages offered from displayed items, signs, and menu boards, and clarified uncertainties by asking vendors.

Categorizing vending by items offered

Vending categories included: category A: fresh produce, i.e., fruit and/or vegetable stands and carts; category B: ethnic foods, e.g., empanada stands, Chinese-food trucks, Halal carts; category C: other prepared foods, e.g., hot-dog carts, barbeque vendors, cheesesteaks; category D: frozen novelty, e.g., ice-cream trucks, Italian-ice carts, snow-cone stands; and category E: other, e.g., honey-roasted nut, bagged-chips, and candy vendors.

Types of vending by healthfulness

Investigators categorized vending as “healthier” (offering only whole foods like fruits, vegetables, unprocessed grains, unsweetened nuts), “less-healthy” (offering only processed or prepared foods like bagged chips, preserved meats, assorted confections), or “mixed” (offering both “healthier” and “less-healthy” items).

Neighborhood data

Information on neighborhoods came from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH). DOHMH conducts a yearly, random-digit-dialed, Community Health Survey of adults including various demographics and health-related questions (http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/survey/survey.shtml). Questions for 2010 included items about dietary intake (e.g., servings of fruits and vegetables consumed yesterday), and diet-related health (e.g., ever told you have diabetes). Data were available for United Hospital Fund “neighborhoods” (UHFs), dividing the Bronx into five regions having notable demographic, population-density, and health differences. Details about survey response rates (37% by landline, 46% by cell phone), stratified sampling design, survey weights and adjustments for number of adults per household are available on the DOHMH website (http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/survey/survey.shtml).

Weather and seasonality

Vendors reported their months of operation and whether they suspended operations during precipitation (i.e., rain or other). Based on reported months of operation investigators characterized vendors as operating in summer (July-September), winter (January-March), or both.

Data analysis and mapping

Investigators used Stata version 11 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX) to aggregate individual-level DOHMH-survey responses to the level of the “neighborhood” (UHF), with sampling weights reflecting the survey design. Analyses included frequencies and percentages of vendors selling different items in neighborhoods by weather and season. Analyses also included Spearman correlations between the number of “healthier”, “less-healthy” or “mixed” vendors per number of residents in a neighborhood and neighborhood characteristics (i.e., demographic, diet, and diet-related health measures). Investigators used ArcGIS software (version 9.3.1, ESRI, Redlands, CA) to map seasonal variation in “healthier”, “less-healthy”, and “mixed” vending.

RESULTS

A total of 372 vending vehicles were identified. Fresh-produce vendors (vending category A), totaling 84, were outnumbered more than 3:1 by other vendors (vending categories B-E) that typically offered “less-healthy” items.

Seventy-two vendors were “in transit” (e.g., ice-cream trucks driving through neighborhoods), precluding detailed assessment of the foods they offered. Of the 300 vendors assessed in detail, a similar percentage offered “less-healthy” prepared food like hot dogs and fried rice as offered fruits or vegetables like apples or vegetable side dishes (29% vs. 31% respectively). Only one of the vendors assessed in detail offered whole grain (brown rice) despite our study protocol's liberal inclusion of popcorn, whole-grain chips, and sweetened granola products in what could have been counted as whole grain. A majority of vendors (59%) offered processed foods like candies and salty snacks, including 15% of fresh-produce vendors (vending category A) who sold pastries, cookies, and/or onion rings. Conversely, only 5% of non-produce vendors (vending categories B-E) offered any fruit or vegetable (e.g., sliced melon and green salad).

Among vendors answering questions regarding weather (Table 1), all vendor types were less numerous on rainy days; only 14% reported working irrespective of precipitation. Nearly 90% of fresh-produce vendors and 95% of frozen-novelty vendors reported not coming out on wet days. Overall, the preponderance of “less-healthy” vending decreased with precipitation such that the proportion of vendors offering at least some healthier options (i.e., “healthier” + “mixed” vending) increased in relative terms. A similar shift in vending proportions was seen with the transition from summer to winter.(Appendix Table A1)

Table 1.

Variation in the number and distribution of mobile food vendors (N = 212a) by weather

| Vending in fair weather only (Vendors that reported not operating in precipitation) | Vending in all weather (Vendors that reported operating even in precipitation) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vending category | “Healthier” N (%)b | “Mixed” N (%)b | “Less-healthy” N (%)b | Total N (%)c | “Healthier” N (%)b | “Mixed” N (%)b | “Less-healthy” N (%)b | Total N (%)c |

| A. Fresh produce | 51 (87.9) | 7 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) | 58 (31.7) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (20.7) |

| B. Ethnic prepared | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (100) | 16 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 7 (24.1) |

| C. Other prepared | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (100) | 28 (15.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (36.4) | 7 (63.6) | 11 (37.9) |

| D. Frozen novelty | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 74 (100) | 74 (40.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100) | 4 (13.8) |

| E. Other | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 7 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | 1 (3.5) |

| Total | 51 (27.9) | 9 (4.92) | 123 (67.2) | 183 (100) | 5 (17.2) | 7 (24.1) | 17 (58.6) | 29 (100) |

“Healthier” = offering only whole foods like fresh produce, unprocessed grains, or unsweetened nuts; “Less-healthy” = offering only processed or prepared foods like bagged chips, preserved meats, and various confections; “Mixed” = offering a mix of “healthier” and “less-healthy” food items.

Data on whether vendors conducted business in all weather were not available for the total sample of 372 mobile food vendors. Reasons included: vendor being in transit and not approachable for interview (n = 72); vendor refusal to answer questions for any of a variety of reasons (Lucan et al., 2013) (n = 56); vendor being absent from open cart/truck/stand (n = 7); vendor having long line of customers (n = 6); vendor not speaking English or Spanish well enough to communicate answers to bilingual investigators (n = 6); vendor not being the owner of the cart/truck/stand and unsure how to answer questions (n = 4); vendor being unable to answer specific questions for any other reason (n = 9)

Percentages are row percentages and may not sum to 100% due to rounding

Percentages are column percentages and may not sum to 100% due to rounding

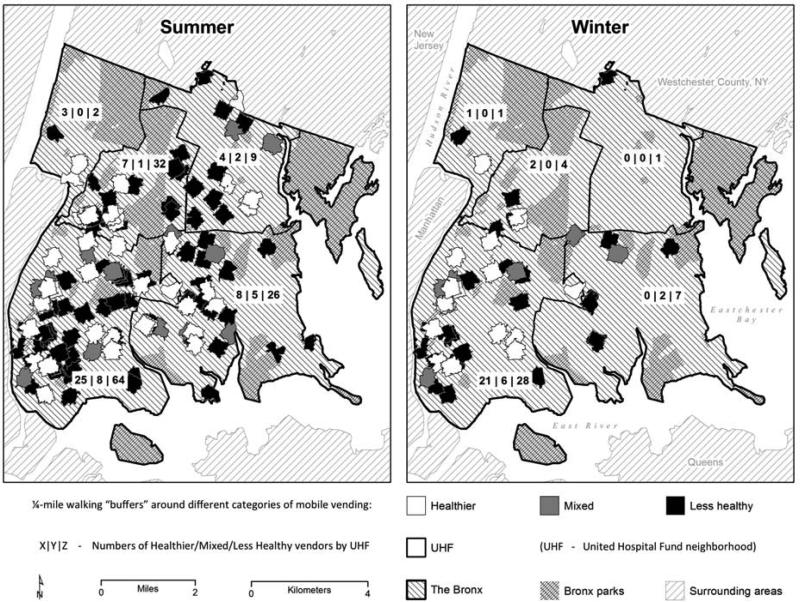

Figure 1 shows seasonal variation in vending type and geographic distribution by neighborhood. A mix of vending across the Bronx in summer shifted to a southwest concentration of vending in winter, with greater relative proportions of “healthier” and “mixed” vending types. More than 75% of all vendors located in the most southwestern neighborhood in winter, home to the poorest Bronx communities with Hispanics representing 65% of populations.(United States Census Bureau).

Figure 1. Seasonal variation in geographic distribution of mobile food vendors reporting a definitive yearly start date and yearly end date (N = 200)a.

Summer = July - September; Winter = January - March. Definitions for “Healthier”, “Mixed”, and “Less-Healthy” appear in the footnote to Table 2. United Hospital Fund neighborhoods (UHFs) are used by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to divide the city into analyzable units; the Bronx has five UHFs with marked demographic and health differences. The maps in the above figure show ¼-mile street-network “buffers” around each vendor; other food-environment research has demonstrated that ¼ mile may be a particularly relevant distance for accessing food,(Tester et al., 2010) especially for individuals without a car.(Thornton et al., 2012) The map on the left shows locations for 196 vendors, the map on the right shows locations for 73 vendors; both maps may appear to show fewer locations due to substantial overlap in areas of high vendor density. Specific reasons why data on seasonal variation was not available for all identified vendors appear in footnote a of Appendix Table 1A.

Table 2 shows correlations by season between exclusively “less-healthy” vending per capita, and mean neighborhood diet, diet-related health, and demographic characteristics. In summer, there were generally strong correlations between exclusively “less-healthy” vending per capita and neighborhood-mean characteristics. In winter, correlations were in the same direction but generally smaller in magnitude. Exceptions were correlations with the proportions of Hispanic residents and residents living below the federal poverty level; these correlations with per-capita “less-healthy” vending became stronger in winter.

Table 2.

Correlations by season between exclusively “less-healthy”a vending per capita, and mean neighborhood diet, diet-related health, and demographic characteristics

| Mean Neighborhood Characteristicsb | Summer rc | p valued | Winter rc | p valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | ||||

| Fruit and vegetable intake (servings of fruits/vegetables eaten yesterday) | −0.80 | 0.104 | −0.50 | 0.391 |

| Diet-related health | ||||

| Body mass index [BMI] (reported weight [kg]/reported height2 [m2]) | 0.90 | 0.037 | 0.30 | 0.634 |

| Prevalence of known diabetes (ever been told you have diabetes) | 0.40 | 0.505 | 0.20 | 0.747 |

| Prevalence of known hypercholesterolemia (ever been told you have high cholesterol) | 0.90 | 0.037 | 0.80 | 0.104 |

| Prevalence of known hypertension (ever been told you have high blood pressure) | 0.90 | 0.037 | 0.70 | 0.188 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Non-white proportion (being any race other than “White”) | 0.80 | 0.104 | 0.50 | 0.391 |

| Hispanic proportion (reporting “Hispanic” as ethnicity) | 0.80 | 0.104 | 0.90 | 0.037 |

| Proportion not graduating high school (reporting less than full high-school education) | 0.80 | 0.104 | 0.50 | 0.391 |

| Proportion below 100% Federal Poverty Level (calculated from household annual income) | 0.80 | 0.104 | 0.90 | 0.037 |

“Less-healthy” = offering only processed or prepared foods like bagged chips, preserved meats, and various confections

All “neighborhood” characteristics derived from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Community Health Survey for 2010 by aggregating individual data to the level of the United Hospital Fund neighborhood

r = Spearman correlation coefficient

Nominal p-values (not adjusted for multiple comparisons)

Similar correlation patterns were seen for any “less-healthy” (“less healthy” + “mixed”) vending per capita and neighborhood-mean characteristics.(Appendix Table A2) There were no meaningful correlations with per-capita “healthier” vending, either exclusively (Appendix Table A3) or any (Appendix Table A4).

DISCUSSION

Mobile food vendors vary in both the items they offer and the consistency of their presence. Overall, vendors offered “less-healthy” prepared and processed items over “healthier” whole foods. However, the distribution of vendor types depended considerably on day-to-day weather, seasonality, and neighborhood characteristics. Wet days and winter months substantially reduced the total number of vendors on the street, but the amount of “less-healthy” vending most. During winter, some neighborhood correlations with “less-healthy” vending were less severe, but poor and Hispanic communities were disproportionately affected in both summer and winter.

The current study is not the first to show disadvantaged populations might be further disadvantaged by “less-healthy” mobile vending. A study from Nairobi showed street vendors in the lowest-income areas sold the highest proportions of refined sugars and starches, and lowest proportions of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts.(Mwangi et al., 2002) A U.S. study showed mobile vendors offered a relative paucity of “healthier” foods around schools in low-income minority neighborhoods.(Tester et al., 2010) Another U.S. study showed the odds of purchasing food from mobile vendors increased with food insecurity, and that “less-healthy” foods were among the most-purchased items.(Sharkey et al., 2012) The current study is the first to demonstrate potentially different implications of mobile vending by season (beyond winter attrition in total vendor count (Valdez et al., 2012)).

Our study looked only at “mobile” vending in isolation from “fixed” food sources—e.g., restaurants and stores. The limited offerings of healthier foods in restaurants and stores in lower-income and minority neighborhoods have been well documented,(Baker et al., 2006) particularly in New York City.(Gordon et al., 2011; Horowitz et al., 2004; Neckerman et al., 2010) Mobile vendors might improve healthy-food provision in such neighborhoods, both directly—through initiatives like Green Carts, permitting street vendors to sell exclusively whole, fresh, unprocessed produce (Leggat et al., 2012; Lucan et al., 2011)—and indirectly, by encouraging adjacent stores to compete for fruit-and-vegetable business and provide fresh produce themselves.(Leggat et al., 2012) Also, studies have suggested that when healthier options like fruits and vegetables are available from mobile vendors, people purchase and consume more of them irrespective of,(Abusabha et al., 2011; Jahn and Shavitz; Tester et al., 2010) even instead of,(Tester et al., 2012) other less-healthful items that might be available.

Our study had several strengths: (1) being the first countywide study of mobile food vendors in the developed world, (2) using a multidimensional approach, as advocated by others,(Rose et al., 2010; Widener et al., 2011) considering what items vendors offered, where vendors were located, and when vendors sold, (3) considering not only “healthier” and “less-healthy” vendors, but also “mixed” vendors—an incremental improvement on past food-environment research that bluntly dichotomized food sources as “healthy”, like supermarkets, and “unhealthy”, like convenience stores (Vernez Moudon et al., 2013) (ignoring that both can be sources of “healthier” and “less-healthy” items), (4) modeling different scenarios by weather, season, and neighborhood for more nuanced understanding than provided from prior studies, (5) showing important correlations between vending healthfulness and diet, diet-related health, and demographic characteristics of neighborhoods.

There were also limitations: (1) being cross-sectional, this study shows correlation, not causality, (2) investigators were not able to speak with all identified vendors, but, crucially, interview participation did not differ by whether vending was “healthier”, “mixed”, or “less-healthy” (data not shown), (3) there is no way to verify if investigators identified all vendors since a great majority of vendors had no permits (Lucan et al., 2013) and there is no adequate government record or other list of vendors for enumeration, (4) investigators cannot comment on specific sales or whether vendors’ customers are local residents, the locally employed who live elsewhere, or transients; investigators can only assume, as others have,(Mwangi et al., 2002) that the kinds of items vendors offered were those that local customers (residents and/or others) tended to buy and consume, (5) results may not be generalizable to other communities.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that mobile vendors provided healthy foods relatively infrequently. Mobile vending might exacerbate demographic, diet, and diet-related health disparities in urban neighborhoods, but the extent of their negative contributions to food-environment healthfulness may vary by weather and season. From a positive standpoint, mobile vending could improve healthy-food availability in neighborhoods (Abusabha et al., 2011; Jennings et al., 2012; Leggat et al., 2012; Marx, 2012; Tester et al., 2012; Widener et al., 2012) and might provide a viable alternative to more-resource-intensive strategies for food-environment modification focused on ‘fixed’ food sources (e.g., restricting fast-food development,(Babey et al., 2011; Keener, July 2009) attracting new grocers,(Babey et al., 2011; Centers for Disease Control, 2011; Institute of Medicine, 2009; Keener, July 2009) redesigning small stores,(Bodor et al., 2010; Centers for Disease Control, 2011; Dannefer et al., 2012; Gittelsohn et al., 2010; Institute of Medicine, 2009; Keener, July 2009; O'Malley et al., 2013; Raja, 2008) or promoting supermarkets (Centers for Disease Control, 2011; Giang et al., 2008; Institute of Medicine, 2009; Keener, July 2009; Morland et al., 2002; Pothunkuchi, 2005)). Future research on mobile vending should explore availability, quality, and price of mobile foods compared to foods from adjacent store-front businesses, and determine customer demographics, purchasing, and consumption patterns. Until the findings of such research are available, it is reasonable to conclude that mobile vendors are part of broader food environments and should not be ignored in future food-environment conceptualizations or studies.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Food-environment research and policy has mostly excluded mobile food vending

We assessed mobile vending in Bronx, NY, correlating findings with neighborhood data.

Mobile vending varied in presence, distribution, and foods offered by weather.

Per capita “less-healthy” vending by season had demographic and health correlates.

Mobile vending may negatively impact food-environment healthfulness, but need not.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank A. Hal Strelnick, MD, for project guidance; Nandini Deb, MA, and Mahbooba Akhter Kabita for assistance with Bengali translation of interview questions; Hope M. Spano and the Hispanic Center of Excellence at Albert Einstein College of Medicine for intern coordination and financial support for data collection; Gustavo Hernandez for help with data collection. This publication was made possible by the CTSA Grant UL1 RR025750 and KL2 RR025749 and TL1 RR025748 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors have any competing interests or conflicts to report. We have no commercial associations or affiliations. This publication was made possible by the CTSA Grant UL1 RR025750 and KL2 RR025749 and TL1 RR025748 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). Research assistants received a stipend through the Bronx Center to Reduce and Eliminate Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (BxCREED).

REFERENENCES

- Abusabha R, Namjoshi D, Klein A. Increasing access and affordability of produce improves perceived consumption ofvegetables in low-income seniors. J Am DietAssoc. 2011;111:1549–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babey SH, Wolstein J, Diamant AL. Food environments near home and school related to consumption of soda and fast food. Policy brief. 2011:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EA, Schootman M, Barnidge E, Kelly C. The role of race and poverty in access to foods that enable individuals to adhere to dietary guidelines. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3:A76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodor JN, Ulmer VM, Dunaway LF, Farley TA, Rose D. The rationale behind small food store interventions in low-income urban neighborhoods: insights from New Orleans. The Journal of nutrition. 2010;140:1185–1188. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion - Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity “State Initiatives Supporting Healthier Food Retail: An Overview of the National Landscape”. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer R, Williams DA, Baronberg S, Silver L. Healthy bodegas: increasing and promoting healthy foods at corner stores in New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:e27–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giang T, Karpyn A, Laurison HB, Hillier A, Perry RD. Closing the grocery gap in underserved communities: the creation ofthe Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14:272–279. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000316486.57512.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittelsohn J, Suratkar S, Song HJ, Sacher S, Rajan R, Rasooly IR, Bednarek E, Sharma S, Anliker JA. Process evaluation of Baltimore Healthy Stores: a pilot health intervention program with supermarkets and corner stores in Baltimore City. Health promotion practice. 2010;11:723–732. doi: 10.1177/1524839908329118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C, Purciel-Hill M, Ghai NR, Kaufman L, Graham R, Van Wye G. Measuring food deserts in New York City's low-income neighborhoods. Health Place. 2011;17:696–700. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz CR, Colson KA, Hebert PL, Lancaster K. Barriers to buying healthy foods for people with diabetes: evidence of environmental disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1549–1554. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Local GovernmentActions to Prevent Childhood Obesity. National Academy of Sciences; Washington, DC.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn M, ShavjZ M. Green Cart Vendors Face Diet of Challenges City Limits [Google Scholar]

- Jennings A, Cassidy A, Winters T, Barnes S, Lipp A, Holland R, Welch A. Positive effect of a targeted intervention to improve access and availability of fruit and vegetables in an area of deprivation. Health Place. 2012;18:1074–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keener D, Goodman K, Lowry A, Zaro S, Kettel Khan L. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States: Implementation and measurement guide. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.; Atlanta, GA.: Jul, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick S, Reedy J, McKinnon R. Web-based compilation: measures ofthe food environment. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Leggat M, Kerker B, Nonas C, Marcus E. Pushing Produce: The New York City Green Carts Initiative. J Urban Health. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9688-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucan SC, Maroko A, Shanker R, Jordan WB. Green Carts (mobile produce vendors) in the Bronx-optimally positioned to meet neighborhood fruit-and-vegetable needs? J Urban Health. 2011;88:977–981. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9593-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucan SC, Varona M, Maroko AR, Bumol J, Torrens L, Wylie-Rosett J. Assessing mobile food vendors (a.k.a. street food vendors)-methods, challenges, and lessons learned for future food-environment research. Public Health. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx RF. Turnarounds: How Food Trucks Went From ‘Scourge’ to ‘Savior. New York Magazine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon RA, Reedy J, Morrissette MA, Lytle LA, Yaroch AL. Measures of the food environment: a compilation ofthe literature, 1990-2007. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36:S124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A. The contextual effect of the localfood environment on residents’ diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. American Journal ofPublic Health. 2002;92:1761–1767. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi AM, den Hartog AP, Mwadime RK, van Staveren WA, Foeken DW. Do street food vendors sell a sufficient variety of foods for a healthful diet? The case of Nairobi. Food & Nutrition Bulletin. 2002;23:48–56. doi: 10.1177/156482650202300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neckerman KM, Bader MD, Richards CA, Purciel M, Quinn JW, Thomas JS, Warbelow C, Weiss CC, Lovasi GS, Rundle A. Disparities in the Food Environments of New York City Public Schools. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley K, Gustat J, Rice J, Johnson CC. Feasibility of increasing access to healthy foods in neighborhood corner stores. J Community Health. 2013;38:741–749. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothunkuchi K. Attracting supermarkets to the inner city: economic development outside the box. Economic Development Quarterly. 2005;19:232–244. [Google Scholar]

- Raja S, Ma C, Yadav P. Beyond Food Deserts: Measuring and Mapping Racial Disparities in Neighborhood Food Environments. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 2008;27:469–482. [Google Scholar]

- Rose D, Bodor JN, Hutchinson PL, Swalm CM. The importance of a multi-dimensional approach for studying the links between food access and consumption. Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140:1170–1174. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Johnson CM. Use ofVendedores (Mobile Food Vendors), Pulgas (Flea Markets), and Vecinos o Amigos (Neighbors or Friends) as Alternative Sources ofFood for Purchase among Mexican-Origin Households in Texas Border Colonias. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:705–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester JM, Yen IH, Laraia B. Mobile food vending and the after-school food environment. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester JM, Yen IH, Laraia B. Using mobile fruitvendors to increase access to fresh fruit and vegetables for schoolchildren. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2012;9:E102. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester JM, Yen IH, Pallis LC, Laraia BA. Healthy food availability and participation in WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) in food stores around lower- and higher-income elementary schools. Public Health Nutrition. 2011;14:960–964. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton LE, Pearce JR, Macdonald L, Lamb KE, Ellaway A. Does the choice of neighbourhood supermarket access measure influence associations with individual-level fruit and vegetable consumption? A case study from Glasgow. IntJ Health Geogr. 2012;11:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics American Community Survey (ACS), Selected Housing Characteristics. [4 August 2012];Selected Economic Characteristics, and Selected Social Characteristics in the United States. 2010 2010 http://factfinder2.census.gov.

- Valdez Z, Dean WR, Sharkey JR. Mobile and home-based vendors’ contributions to the retail food environment in rural South Texas Mexican-origin settlements. Appetite. 2012;59:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernez Moudon A, Drewnowski A, Duncan GE, Hurvitz PM, Saelens BE, Scharnhorst E. Characterizing the food environment: pitfalls and future directions. Public Health Nutrition. 2013:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widener MJ, Metcalf SS, Bar-Yam Y. Dynamic urban food environments a temporal analysis of access to healthy foods. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41:439–441. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widener MJ, Metcalf SS, Bar-Yam Y. Developing a mobile produce distribution system for low-income urban residents in food deserts. J Urban Health. 2012;89:733–745. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9677-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.