Abstract

Background

Cigarette smoking is the major cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. Recent studies suggest that susceptibility to cigarette smoke may vary by race/ethnicity; however, they were generally small and relied on self-reported race/ethnicity.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that relationships of smoking to lung function and percent emphysema differ by genetic ancestry and self-reported race/ethnicity among Whites, African-Americans, Hispanics and Chinese-Americans.

Design

Cross-sectional population-based study of adults age 45-84 years in the United States

Measurements

Principal components of genetic ancestry and continental ancestry estimated from one-million genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms. Pack-years calculated as years smoking cigarettes-per-day/20. Spirometry measured for 3,344 and percent emphysema on computed tomography for 8,224 participants.

Results

The prevalence of ever-smoking was: Whites, 57.6%; African-Americans, 56.4%; Hispanics, 46.7%; and Chinese-Americans, 26.8%. Every 10 pack-years was associated with −0.73% (95% CI −0.90%, −0.56%) decrement in the forced expiratory volume in one second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) and a 0.23% (95% CI 0.08%, 0.38%) increase in percent emphysema. There was no evidence that relationships of pack-years to the FEV1/FVC, airflow obstruction and percent emphysema varied by genetic ancestry (all p>0.10), self-reported race/ethnicity (all p>0.10) or, among African-Americans, African ancestry. There were small differences in relationships of pack-years to the FEV1 among male Chinese-Americans and to the FEV1/FVC with African and Native American ancestry among male Hispanics only.

Conclusions

In this large cohort, there was little-to-no evidence that the associations of smoking to lung function and percent emphysema differed by genetic ancestry or self-reported race/ethnicity.

Keywords: cigarette smoke, genetic ancestry, lung function, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD, emphysema, FVC, Forced Vital Capacity, FEV1, Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), defined by airflow obstruction that is not fully reversible,1 is anticipated to be the third leading cause of death worldwide by 2020.2 Cigarette smoking is the primary cause of COPD and emphysema,3 characterized by destruction of alveolar walls and enlargement of air spaces distal to the terminal bronchioles,4 yet only some smokers develop these diseases. COPD outcomes vary by race/ethnic group. Mortality from COPD is highest among whites in the United States (US) but is rising rapidly among African-Americans,5 who have higher rates of hospitalization and emergency department visits due to COPD.5 Further, COPD prevalence is higher among some Hispanic subgroups compared to African-Americans.6 It is unclear if differences in COPD outcomes result from variation in smoking patterns, healthcare access, environmental exposures, or genetic susceptibility. The diverse US population provides an ideal setting to study differential effects of smoking on lung function.

A large meta-analysis suggested no difference in COPD risk for equivalent smoking history among African-Americans, Hispanics, and whites, but potentially lower risk in Asian/Pacific Islanders,7 while other studies suggested that African-Americans are at increased risk;8-11 yet another suggested decreased risk among Hispanics.12 All but two11,12 of these studies relied on self-reported race/ethnicity. Genetic ancestry has several advantages for defining ancestry compared to self-report, including greater objectivity and precision, particularly for persons with admixed backgrounds. Markers of genetic ancestry have been shown to improve accuracy in referencing lung function.13 We examined if the relationships of pack-years of smoking to lung function and percent emphysema varied by genetic ancestry, continental ancestry or self-reported race/ethnicity in a large multi-ethnic cohort study.

METHODS

Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) is a population-based prospective cohort that recruited 6,814 participants ages 45-84 years in 2000-2002 from six US sites who were white, African-American, Hispanic, or Asian (predominantly of Chinese origin).14 Each site recruited at least two race/ethnic groups and all race/ethnic groups were recruited at multiple sites. Exclusion criteria included clinical cardiovascular disease, pregnancy, weight >300 lbs., inability to speak English, Spanish, Cantonese, or Mandarin, and chest computed tomography (CT) within the past year.

The MESA Family Study enrolled an additional 1,612 African-American and Hispanic participants, predominantly siblings of MESA participants. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were identical, except that clinical cardiovascular disease was permitted.

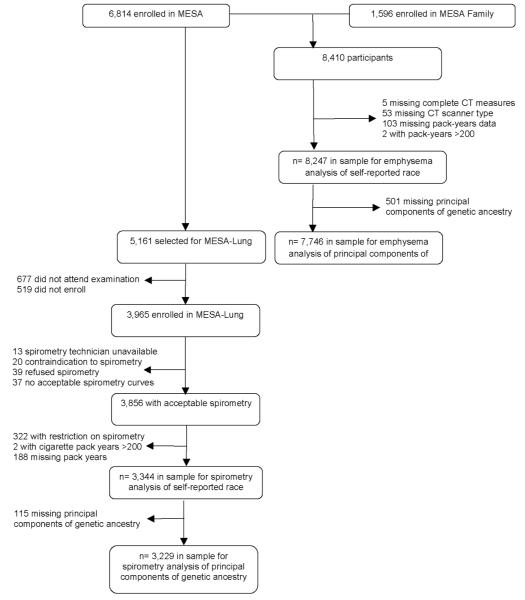

The MESA Lung Study assessed percent emphysema for all MESA and MESA Family participants and performed spirometry on a subset of participants. The subset was randomly sampled among those who consented to genetic analyses, underwent baseline measures of endothelial function, and attended an examination during the 2004-2006 MESA Lung recruitment period (Figure 1). Chinese-Americans were over-sampled to improve precision in this group. Participants with restrictive spirometry patterns, defined as a forced vital capacity (FVC) less than the lower limit of normal (LLN)15 and a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to FVC ratio above the LLN, were excluded from analyses as the hypotheses relate specifically to obstructive lung disease.

Figure 1.

Participants in the MESA and MESA Family Studies in Analyses for Spirometry and Emphysema

The protocols of MESA, MESA Family, and MESA Lung were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all collaborating institutions and the National Heart Lung Blood Institute.

Genetic Ancestry

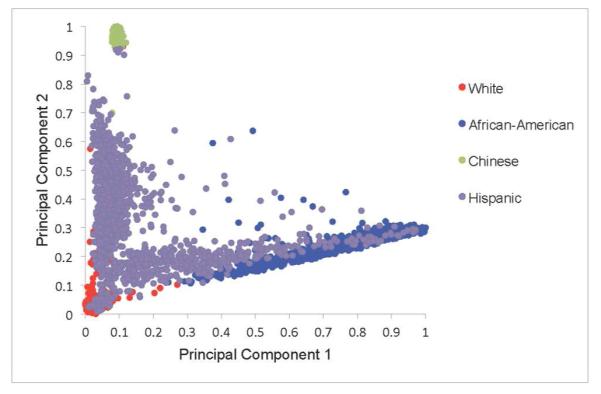

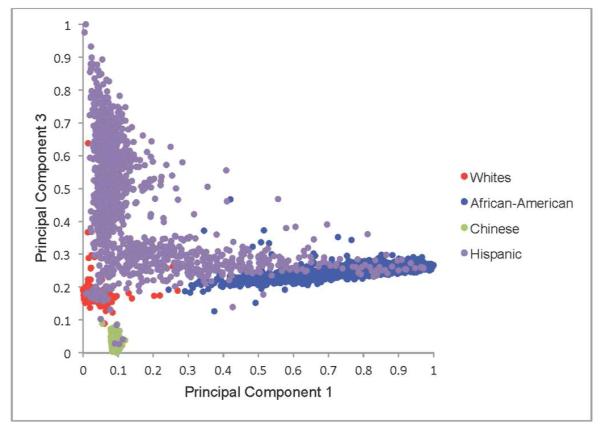

Genetic ancestry was defined using principal components16 derived from genome-wide data from the Affymetrix 6.0 chip among consenting participants available genetic data (n=8,227). Principal component analysis, when applied to genotype data, allows for the transformation of a large number of correlated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) into a smaller number of continuous axes of variation that correspond to regions of geographic ancestry.16 A total of 50 principal components were defined. The first three principal components explain 86% of the total observed variation. A Cattell scree plot17 showed that the relative value of additional principal components (PCs) beyond the third PC was very small. These three PCs also reveal three geographic clines, the first principal component (PC1) identifies variation between European and African ancestry; the second, PC2, identifies variation between European and Chinese ancestry (Figure 2a); and the third, PC3, identifies variation across Hispanics (Figure 2b).

Figure 2a.

Distribution of Principal Component 1 and Principal Component 2 by Self-Reported Race

Figure 2b.

Distribution of Principal Component 1 and Principal Component 3 by Self-Reported Race

Continental ancestry was assessed among African-Americans and Hispanics using ADMIXTURE. Among African-Americans, proportion of African ancestry was determined based on ADMIXTURE estimates from a two-way model. Among Hispanics, proportion of African and Native American ancestry was determined based on a three-population model.

Race/ethnicity

Race/ethnicity, age, gender, educational attainment, and medical history were obtained via questionnaire. Categories for race/ethnicity were consistent with US 2000 Census definitions.18 Participants reported one of the following race/ethnicities: non-Hispanic White, African-American, Asian-American of Chinese descent, or Hispanic/Latino. Participants who reported Hispanic ethnicity were classified as Hispanic regardless of self-reported race.

Cumulative exposure to cigarette smoke (pack-years)

Pack-years of cigarette smoking was calculated as: (years smoked) (cigarettes per day/20) using standardized questionnaire items.19 Urinary cotinine level was assessed in the spirometry group by immunoassay (Immulite 2000 Nicotine Metabolite Assay; Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA). For self-reported former smokers whose cotinine levels were consistent with current smoking, years smoked was increased by a value equal to the time interval from last reported smoking to the time of cotinine assay.

Current smoking was defined as cigarette use in the last 30 days or a urinary cotinine level of greater than 100 ng/ml. Ever-smoking was defined as greater than 100 lifetime cigarettes smoked.

Spirometry

Spirometry was conducted in 2004-2006 in accordance with the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines20 on a dry-rolling-sealed spirometer with automated quality checks (Occupational Marketing, Inc., Houston, TX). Spirometry exams were reviewed by one investigator.21 The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of both FEV1 and FVC on random 10% replicate testing was 0.99. Airflow obstruction was defined as FEV1/FVC below the LLN.22

Percent Emphysema

Emphysema was quantitatively measured on lung fields of cardiac CT scans obtained at full inspiration on multi-detector and electron-beam CT scanners, which included approximately 70% of the lung volume from the carina to the lung bases.23 Each participant underwent two scans and the scan with the greater volume of lung air was used, except in cases of discordant scan quality, when the higher-quality scan was analyzed.24 Image attenuation was assessed with a modified version of the Pulmonary Analysis Software Suite25-27 at a single reading center. As air outside the body has a mean attenuation of −1,000 Hounsfield units (HU), the attenuation of each pixel in the lung regions was corrected to equal measured pixel attenuation x (−1,000/mean air attenuation). Percent emphysema was defined as the percentage of the total voxels in the lung with attenuation of less than "910 Hounsfield units. Emphysema measurements from the cardiac scans correlated closely with those from full-lung scans in the same study participants.24 The inter-scan ICC of percent emphysema on 100% replicate scans was 0.94.

Additional variables

MESA-Lung participants were surveyed regarding factors relevant to lung disease including self-report of physician diagnosis before age 45, hayfever, family history of emphysema, occupational exposure to dust, fumes, and smoke, and household environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure defined as living with a smoker. Cigar and pipe smoking was defined as previously described.28 Depth of inhalation of cigarettes was assessed using standardized questionnaire items.29 Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight was measured to the nearest pound.

Statistical Analysis

The cohort was stratified by race/ethnicity and gender for descriptive purposes. Analyses were stratified by gender, given gender differences in smoking history and lung function.

Initial multivariable regression models of lung function and airflow obstruction included age, age2, height2, pack-years, and either race/ethnicity or principal components of genetic ancestry,30 and adjusted for current smoking. Fully adjusted multivariable regression models additionally included body mass index (BMI), educational attainment, cigar smoking status, cigar pack-years, second-hand smoke exposure, depth of inhalation, time before first cigarette in the morning, urinary cotinine level, asthma, hayfever, family history of emphysema, and occupational exposure to dust, fumes or smoke.

Linear regression was used for analyses of lung function and percent emphysema and logistic regression for analyses of airflow obstruction. As the participants included in analyses of percent emphysema included related family members, these analyses employed generalized estimating equations (GEE)31 to account for correlation between family members and were additionally adjusted for CT scanner type and dose. Participants with lung function measures did not include any related family members thus GEE were not necessary.

Differences in the relationship between pack-years and lung function measures by genetic ancestry and race/ethnicity were tested in full multivariable models using the −2 log likelihood test of nested models with and without the interaction terms on an additive scale for lung function and lung density and a multiplicative scale for airflow obstruction. Sensitivity analyses were performed on the converse scales. As race and principal components of ancestry are collinear, they were not included in the same models; rather, two separate sets of analyses were performed. All models met the assumptions for linear and logistic regression, respectively. Presented results are untransformed. Statistical significance was defined as two-tailed P-values <0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Among 3,344 participants in spirometry analyses using self-reported race, 35% were non-Hispanic white, 26% African-American, 22% Hispanic, and 17% Chinese-American. The background of Hispanic participants was 51% Mexican, 14% Puerto Rican, 14% Dominican, 4% Cuban, and 17% other background. The mean age was 66 years; 48% were male. Eleven percent was current smokers and 45% former smokers, with a median of 18 pack-years of cigarette smoking (IQR 6, 36) among ever-smokers.

Participant characteristics in the spirometry analysis are shown in Table 1. Age and gender distributions were similar across race/ethnic groups. African-Americans were more likely to report current smoking than other groups. Pack-years of smoking were greatest among whites followed by African-Americans, Hispanics and Chinese-Americans. Women were less likely to have ever smoked than men, and only 10 of 278 Chinese-American women reported ever smoking.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the MESA-Lung Sample Stratified by Race/Ethnicity and Gender

| Men (n=1,609) | Women (n=1,735) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| n = 3,344 | Non-Hispanic Whites |

African- Americans |

Hispanics | Chinese- Americans |

Non-Hispanic Whites |

African- Americans |

Hispanics | Chinese- Americans |

|

|

|

|||||||

| n (%) | 582(36) | 402(25) | 342(21) | 283(18) | 591(34) | 471(27) | 395(23) | 278(16) |

| Age, mean (SD), years |

66(9.8) | 66(9.7) | 64(10.0) | 66(9.7) | 66(10.0) | 66(9.5) | 65(9.8) | 66(9.6) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||||

| Never | 209(36) | 129(32) | 124(36) | 142(50) | 288(49) | 252(54) | 269(68) | 268(96) |

| Former | 328(56) | 198(49) | 175(51) | 119(42) | 255(43) | 160(34) | 102(26) | 6(2) |

| Current | 45(8) | 75(19) | 43(13) | 22(8) | 48(8) | 59(13) | 24(6) | 4(1) |

| Pack-years of smoking,* median (IQR) |

24.0 (9.0,44.0) |

20.3 (8.8,36.8) |

16.3 (5.9,34.5) |

17.5 (5.4,33.0) |

18.9 (6.0,36.8) |

17.3 (6.4,33.0) |

7.0 (2.0,16.5) |

13.5 (2.0,19.5) |

| Inhalational depth (cigarettes)† n(%) |

||||||||

| ‘Shallow’ | 25(7) | 12(4) | 17(8) | 20(14) | 11(4) | 16(7) | 22(17) | 2(20) |

| ‘Moderate’ | 37(10) | 51(19) | 44(20) | 30(21) | 40(13) | 56(26) | 37(29) | 5(50) |

| ‘Deep’ | 190(51) | 132(48) | 85(39) | 54(38) | 160(53) | 98(45) | 28(22) | 3(30) |

| ‘Very deep’ | 105(28) | 60(22) | 49(22) | 25(18) | 67(22) | 38(17) | 23(18) | 0(0) |

| Time until first cigarette‡ (SD), hours |

1.6(2.3) | 1.6(2.3) | 2.9(3.4) | 1.6(1.8) | 2.6(5.0) | 2.2(3.1) | 3.5(3.9) | 6.0(6.4) |

| Cigar use* n(%) | 155(42) | 67(25) | 36(17) | 6(5) | 10(3) | 10(5) | 2(2) | 0(0) |

| Cigar-years,§ median (IQR) |

20(10,39) | 15(7,55) | 10(6,24) | 29(16,51) | 16(8,28) | 17(5,30) | 0 (0,0) | 0(0,0) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm |

176(6.9) | 176(6.8) | 169(6.4) | 168(6.4) | 162(6.6) | 162(6.9) | 155(5.8) | 155(6.1) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 |

28(4.1) | 28(4.6) | 29(4.1) | 24(3.2) | 28(5.8) | 31(6.2) | 30(5.4) | 24(3.4) |

| Educational attainment n(%) |

||||||||

| High school or vocational school |

108(19) | 134(33) | 190(56) | 69(24) | 134(23) | 138(29) | 235(59) | 94(34) |

| Incomplete college | 104(18) | 135(34) | 108(32) | 60(21) | 181(31) | 157(33) | 131(33) | 99(36) |

| Complete college | 149(26) | 70(17) | 24(7) | 76(27) | 138(23) | 90(19) | 14(4) | 59(21) |

| Graduate or Professional school |

221(38) | 63(16) | 20(6) | 78(28) | 138(23) | 86(18) | 15(4) | 26(9) |

| Household ETS exposure n(%) |

229(39) | 176(44) | 93(27) | 52(18) | 310(52) | 284(60) | 173(44) | 119(43) |

| Occupational exposure∥ n(%) |

269(46) | 237(59) | 237(59) | 62(22) | 213(36) | 221(47) | 177(45) | 44(16) |

| Asthma¶ n(%) | 52(9) | 32(8) | 16(5) | 14(5) | 54(9) | 56(11) | 38(10) | 10(4) |

| Hay-fever** n(%) | 200(34) | 114(28) | 70(20) | 90(32) | 238(40) | 189(40) | 112(28) | 88(32) |

| Ancestral principal Components (PC), median, [IQR] (n= 3,229) |

||||||||

| PC 1 | 0.020 [0.015, 0.043] |

0.805 [0.698, 0.870] |

0.073 [0.054, 0.169] |

0.091 [0.088, 0.095] |

0.0199 [0.015, 0.036] |

0.804 [0.689, 0.876] |

0.089 [0.062, 0.200] |

0.091 [0.088, 0.095] |

| PC | 2 0.032 [0.026, 0.043] |

0.252 [0.222, 0.272] |

0.307 [0.189, 0.425] |

0.977 [0.971, 0.982] |

0.032 [0.025, 0.042] |

0.252 [0.222, 0.274] |

0.299 [0.202, 0.432] |

0.976 [0.969, 0.982] |

| PC 3 | 0.175 [0.167, 0.182] |

0.250 [0.240, 0.259] |

0.451 [0.284, 0.564] |

0.027 [0.019, 0.038] |

0.176 [0.170, 0.184] |

0.250 [0.240, 0.256] |

0.428 [0.294, 0.566] |

0.028 [0.019, 0.040] |

| Lung function | ||||||||

| FEV1 (SD), L | 3.0(0.7) | 2.6(0.6) | 3.0(0.7) | 2.6(0.6) | 2.2(0.5) | 1.9(0.4) | 2.0(0.5) | 1.8(0.4) |

| FVC (SD), L | 4.3(0.8) | 3.6(0.7) | 3.9(0.8) | 3.5(0.7) | 2.9(0.6) | 2.4(0.5) | 2.6(0.5) | 2.4(.5) |

| FEV1/FVC ratio (SD), % |

72(9.1) | 72(10.7) | 75(8.8) | 74(8.6) | 74(7.8) | 77(8.0) | 78(6.9) | 76(6.6) |

| Airflow obstruction†† n(%) |

79(21) | 63(23) | 31(14) | 9(6) | 57(19) | 23(11) | 11(9) | 1(10) |

Abbreviations

CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; IQR, inter-quartile range; ETS, Environmental Tobacco Smoke (‘second-hand smoke’); FEV1, Forced Expiratory Volume in one second; FVC, Forced Expiratory Vital Capacity.

Footnotes

Among ever smokers.

Depth of cigarette smoke inhalation, from shallow (1) to very deep (4) among ever smokers.

Time between waking until first cigarette of the day.

The usual number of cigars smoked in a day multiplied by the number of years of cigar smoking, among ever cigar smokers.

Occupational exposure to dust, fumes or smoke.

Physician diagnosis of asthma < 45 years old.

History of hay-fever.

FEV1 < 80% predicted and FEV1/FVC < 0.7, among ever smokers.

Estimates of genetic ancestry were available for 3,229 of the 3,344 participants included in the spirometry analysis and followed the expected distribution (Table 1).

Cumulative Smoking, Genetic Ancestry and Lung Function Among Men

Pack-years were associated with significant decrements in lung function and increased odds ratios of airflow obstruction in all race/ethnic groups. Among 1,609 men, every 10 pack-years of smoking was associated with a mean decrement of −0.69% (95% CI −0.92, −0.47) in FEV1/FVC, a mean decrement of −42.6 ml (95% CI: −55.2, −30.0) in FEV1, and a 1.14 (95% CI 1.05, 1.23) increase in the odds of airflow obstruction.

There was no evidence that the relationship of pack-years to FEV1/FVC or airflow obstruction varied by genetic ancestry or self-reported race (Table 2). Plots of the relationship of pack-years to FEV1/FVC showed linear, qualitatively similar relationships for all racial/ethnic groups (Web appendix Figure 1a). Findings were similar when performed on a multiplicative scale and when the outcome was percent predicted FEV1/FVC (all p>0.1).

Table 2.

Mean difference in lung function and odds ratio for airflow obstruction per 10 pack years of smoking among men, stratified by race/ethnicity

| Non-Hispanic Whites |

African-Americans | Hispanics | Chinese-Americans | P-value for differences across self-reported race/ethnic groups [p-value after excluding Chinese-Americans] |

P-value for differences by principal components of ancestry [p-value excluding Chinese-Americans] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n. | 582 | 402 | 342 | 283 | ||

| FEV1/FVC difference (%), (95% CI) |

||||||

| Age-height- adjusted* |

−0.75 (−1.02, −0.48) |

−1.05 (−1.58, −0.52) |

−0.88 (−1.30, −0.23) |

−0.33 (−0.89, 0.23) |

0.29 | 0.03 |

| Multivariable† | −0.75 (−1.08, −0.43) |

−0.65 (−1.20, −0.10) |

−0.77 (−1.26, −0.29) |

−0.33 (−0.95, 0.28) |

0.65 | 0.10 |

|

| ||||||

| FEV1 difference (mL), (95% CI) |

||||||

| Age-height- adjusted* |

−55.0 (−71.6, −38.4) |

−50.5 (−77.9, −23.0) |

−53.6 (−78.2, −28.4) |

−17.0 (−45.9, 11.9) |

0.013 [0.84] |

0.004 [0.38] |

| Multivariable† | −42.7 (−61.7, −23.6) |

−32.1 (−61.2, −3.0) |

−44.2 (−73.4, −14.9) |

−25.5 (−56.4, 5.42) |

0.007 [0.26] |

0.007 [0.23] |

|

| ||||||

| Airflow obstruction OR (95% CI) |

||||||

| Age-height- adjusted* |

1.16 (1.06, 1.23) |

1.23 (1.06, 1.43) |

1.30 (1.11, 1.53) |

1.18 (0.92, 1.52) |

0.51 | 0.61 |

| Multivariable† | 1.20 (1.07, 1.35) |

1.17 (0.98, 1.40) |

1.38 (1.10, 1.73) |

1.41 (0.94, 2.11) |

0.43 | 0.67 |

Age-height-adjusted model adjusted for 10-pack-years of smoking, age, age2, height, height2, and current smoking status.

Multivariable model adjusted for 10 pack-years of smoking, age, age2, height, height2, body mass index, current smoking status, physician-diagnosed asthma before 45 years, family history of emphysema, cigar smoking status, cigar pack-years, second-hand smoke exposure, depth of inhalation, time before first cigarette in the morning, urinary cotinine level, history of hayfever, occupational exposure to dust, fumes or smoke, and educational attainment.

The relationship of pack-years to FEV1, however, differed by genetic ancestry (p = 0.007) and self-reported race/ethnicity (p = 0.007). PC2, which identifies differences in European and Asian ancestry, modified the effect of pack-years of smoking on FEV1 (p = 0.001) whereas interaction terms for pack-years of smoking with PC1 (European vs. African ancestry) and PC3 (European vs. Hispanic ancestry) were not statistically significant (p = 0.30 and 0.94). Results for self-reported race were similar. When self-reported Chinese-American men were removed from the analysis, the interaction term no longer had a significant effect on FEV1 (genetic ancestry p =0.23; self-reported race p =0.26, Table 2 brackets).

The mean difference in the effect of 10 pack-years of smoking on FEV1 among African-Americans compared to non-Hispanic Whites was 7.0 ml (95% CI: −18.5, 32.5); the mean difference in the effect of 10 pack-years on FEV1 among Hispanics compared to Whites was −0.6 ml (95% CI: −26.4, 25.3). The mean difference in the effect of 10 pack-years on FEV1 among Chinese-Americans, however, was significantly different compared to non-Hispanic Whites, with a difference of 49.0 ml (95% CI: 18.8, 79.3, p=0.002). Evidence of an interaction between race/ethnicity and smoking on the FEV1 in men was also present on a multiplicative scale (p=0.02 for both genetic ancestry and self-reported race/ethnicity) and for percent of predicted FEV1 (p=0.02).

Among African-American men, there was no evidence for an interaction between proportion continental African ancestry and pack-years on FEV1, FEV1/FVC, or percent emphysema (all p > 0.05). In Hispanic-American males, however, the interactions terms of pack-years with the FEV1/FVC were significant for Native American (p=0.012) and African (p=0.030) ancestry (likelihood ratio test P=0.016), suggesting a lower FEV1/FVC ratio with greater Native American and African ancestry. No such interaction was present for the FEV1.

Genetic Ancestry, Cumulative Smoking and Lung Function Among Women

Among 1,735 women, each 10 pack-years of smoking was associated with a −0.85% (95% CI −1.13, −0.57) mean decrement in FEV1/FVC, a −48.6 ml (95% CI: −61.6, −35.7) mean decrement in FEV1, and a 1.36 (95% CI 1.20, 1.55) increase in the odds of airflow obstruction. Plots of the relationship of pack-years to FEV1/FVC showed similarly linear relationships for racial/ethnic groups (Web appendix Figure 1b).

There was no evidence that the relationship of pack-years to FEV1, FEV1/FVC, or airflow obstruction differed by genetic ancestry among white, African-American and Hispanic women (Table 3). Chinese-American women were excluded from this analysis given the very small number with a smoking history. Similarly, there was also no evidence for effect modification by self-reported race/ethnicity among women (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean difference in lung function and odds ratio for airflow obstruction per 10 pack years of smoking among women, stratified by race/ethnicity

| Non-Hispanic Whites |

African-Americans | Hispanics | Chinese-Americans‡ | P-value for differences across race/ethnic groups |

P-value for differences by principal components of ancestry |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n. | 591 | 471 | 395 | 278 | ||

| FEV1/FVC difference (%), (95% CI) |

||||||

| Age-height- adjusted* |

−1.06 (−1.42, −0.70) |

−0.76 (−1.23, −0.29) |

−0.57 (−1.17, 0.02) |

0.56 | 0.29 | |

| Multivariable† | −0.97 (−1.38, −0.56) |

−0.82 (−1.35, −0.29) |

−0.65 (−1.30, 0.01) |

0.29 | 0.32 | |

|

| ||||||

| FEV1, mean difference (mL),(95% CI) |

||||||

| Age-height- adjusted* |

−44.0 (−60.9, −27.0) |

−43.5 (−63.7, −23.2) |

−33.6 (−62.6, −4.6) |

0.54 | 0.99 | |

| Multivariable† | −41.1 (−59.8, −22.5) |

−47.1 (−70.5, −23.8) |

−36.7 (−69.0, −4.5) |

0.43 | 0.25 | |

|

| ||||||

| Airflow obstruction odds-ratio (95% CI) |

||||||

| Age-height- adjusted* |

1.32 (1.15, 1.51) |

1.45 (1.17, 1.79) |

1.20 (0.92, 1.58) |

0.48 | 0.69 | |

| Multivariable† | 1.29 (1.08, 1.54) |

1.49 (1.16, 1.54) |

1.53 (0.85, 2.74) |

0.25 | 0.83 | |

Age-height-adjusted model adjusted for 10-pack-years of smoking, age, age2, height, height2, and current smoking status.

Multivariable model adjusted for 10-pack-years of smoking, age, age2, height, height2, body mass index, current smoking status, physician-diagnosed asthma before 45 years, family history of emphysema, cigar smoking status, cigar pack-years, second-hand smoke exposure, depth of inhalation, time before first cigarette in the morning, urinary cotinine level, history of hayfever, occupational exposure to dust, fumes or smoke, and educational attainment.

Chinese-American women excluded from analysis due to small sample size with smoking history

Among African-American and Hispanic women, there was no evidence for any interaction between pack-years and proportion African ancestry and, among Hispanics, Native American ancestry for the FEV1 or FEV1/FVC (all p > 0.05).

Cumulative Smoking and Percent Emphysema

Characteristics of 8,247 participants included in analyses of percent emphysema are shown in web appendix Table 1. Among women, every 10 pack-years of smoking was associated with a 0.43% increase in percent emphysema (p<0.001). Among men, 10 pack-years of smoking was associated with a 0.10% increase in percent emphysema, though the association was not statistically significant (p=0.30). There was no evidence that this association differed by genetic ancestry among men or women, although in women there was suggestion of effect modification by self-reported race/ethnicity (p=0.03) (Web appendix table 2). Furthermore, there was no evidence that the association of pack-years to percent emphysema varied by continental ancestry among African-American and Hispanic women and men (p>0.16).

Sensitivity Analyses

Among 1,255 men and women with a history of smoking greater than 10 pack-years (mean pack-years 36, SD +/− 26), there was also no evidence of that the relationship of pack-years to FEV1, FEV1/FVC, or airflow obstruction differed by self-reported race/ethnicity or genetic ancestry (Web appendix table 3).

In the present study sample, 96% of Chinese, 69% of Hispanics, 9% of African-Americans and 7% of whites were immigrants to the US. Among Hispanics (as well as whites and African-Americans), there was no evidence that either immigrant status or years lived outside the US was associated with the FEV1 or FEV1/FVC ratio. Among Chinese-Americans, immigrant status was not associated with either FEV1 or FEV1/FVC (p=0.37 and p=0.72, respectively). Years lived outside the US was not associated with FEV1 (p=0.19) but was associated with a small decrement in mean FEV1/FVC (−0.06%, (95% CI −0.11, −0.02) p=0.001); additional adjustment for immigrant status and years lived outside the US did not, however, alter the main results on the relationship between race, pack-years, and lung function. (web appendix table 4).

Since MESA excluded participants with clinical cardiovascular disease, we repeated analyses restricted to participants ages 45-64 years, an age range in which clinical cardiovascular disease is rare, and found similar results (web appendix table 5). Site-specific analyses demonstrated no significant interactions with the FEV1/FVC ratio and a significant interaction with the FEV1 at one of the two sites that recruited Chinese-Americans (web appendix table 6), although the direction of association was inconsistent across the six sites.

DISCUSSION

In this large, population-based sample, there was no consistent evidence that the associations of cumulative smoking with FEV1/FVC, airflow obstruction or percent emphysema varied by genetic ancestry among the four largest race/ethnic groups in the US.

Two recent studies have used ancestral informative markers (AIMs) to assess for interaction between genetic ancestry and smoking. A case-control study by Bruse et. al. of variation in tobacco-related susceptibility to COPD by genetic ancestry found that Hispanic smokers had lower odds of COPD and reduced decline in FEV1 compared to Non-Hispanic whites with an equal cumulative smoking history.12 These findings were not replicated in our present study, however differences between the studies include the use of ancestral informative markers (AIMs) in the former case-control study compared to principal components based upon 1 million SNPs in the present population-based study. Additionally, as the study by Bruse et. al. recruited Hispanics at one site (Albuquerque, New Mexico), predominantly of regional Native American and Mexican origin, its findings might apply specifically to Hispanics of the Southwestern region of the United States while the present multicenter study recruited Hispanics of both Mexican and Caribbean origin. Also, differences in mean pack years may have contributed to variation in results. The mean pack-years in the present study is 16 among non-Hispanic whites and 10 among Hispanics where mean pack-years in the aforementioned study was higher (34 for Hispanics and 41 for non-Hispanic whites).

We also found no evidence of a higher risk of COPD among African-Americans, in contrast to a case-control study of 70 cases of early-onset COPD,8 a retrospective review of 160 patients presenting for lung volume reduction surgery,9 and a prospective study of 50 African-Americans and 278 Caucasians,10 all using self-reported race/ethnicity. One explanation for these differences is that prior findings in early-onset and very severe COPD may not apply to the general population and, conversely, findings in the general population may not apply to these extreme phenotypes. Alternatively, small, case-control studies may be subject to selection bias. Notably, a more recent study incorporating genetic measures by Aldrich et. al., used AIMs and identified a trend, though non-significant, toward an interaction between African ancestry and smoking on FEV1 in cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis among self-reported African-Americans.11 These findings were not replicated in our present study. Differences include an older cohort with a higher mean pack-years (30) among the participants in the study by Aldrich et. al. as well as the longitudinal approach, suggesting that it could be possible that there is more variability by race as individuals age. Our results are, however, consistent with a large meta-analysis of population-based studies using self-reported race-ethnicity.7

The present study was unique in enrolling Chinese-Americans along with the three other race/ethnic groups in the same study. We found no evidence of a differential risk in this group for FEV1/FVC, airflow limitation and percent emphysema, however, the association between cumulative smoking and FEV1 was modified by genetic ancestry among men of Chinese-American ancestry. These results build on findings from the prior meta-analysis of lung function, which found that self-reported Asian/Pacific Islanders had smaller smoking-related decrements in FEV1 than whites.7 The specificity of the interaction in FEV1 suggests that it may be related to mean differences in body size among Asian men compared to other race/ethnic groups that are not fully indexed by height21. Other possible explanations for this difference include dietary and lifestyle factors. For example, mean levels of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are substantially higher among Asians and whites compared to other groups in MESA,32 which may contribute to lower risk of COPD.33

Among women, but not men, we identified a statistically significant effect modification on percent emphysema by self-reported race (p=0.03), and a trend toward effect modification by ancestry (p=0.10), (web supplemental table 2). One potential explanation for this finding is a sex-specific loci that determines smoking-related emphysema changes, which may provide an interesting avenue for future research.

Overall, these findings suggest that the effect of cumulative smoking on COPD does not vary substantially among the four major race/ethnic groups in the US. Observed race/ethnic disparities in COPD in the US may instead result from differences in smoking patterns, differential exposure to air pollution or environmental toxins, maternal smoking during pregnancy,34 low birth weight,35 exposure to pulmonary irritants during lung development,9 and occupational exposures. Different smoking habits and brands of cigarettes have also been cited, although depth of inhalation was similar across race/ethnic groups in this study.

This study has a number of strengths, including advanced assessment of genetic ancestry, a population-based study which avoids site-by-race confounding and limits selection bias, large sample size, and standardized methods.

Smoking history may be subject inaccurate reporting; however, results would only be biased if misclassification of pack-years were differential by race/ethnicity. Current smoking was confirmed with cotinine levels in MESA-Lung participants, and the accuracy of self-reported current smoking did not differ by race/ethnicity (p=0.34). Cigarette brand and type was not assessed; however, COPD risk does not vary substantially by brand or type.36

Use of genetic principal components of ancestry may carry biases. If, for example, we seek to control for cultural confounders such as dietary and environmental factors that may be associated with race/ethnic group, using genetic ancestry may potentially misclassify persons who culturally identify with one group while genetic ancestry is admixed.

Additionally, genetic principal components of ancestry as used in these analyses may not capture within group variation particularly among the highly admixed African-American and Hispanic groups. In order to address this issue, we performed analyses using individual continental ancestry proportions. Among African-Americans, we again found no interaction between continental ancestry and pack-years of smoking on lung function. Among Hispanic-American males we found a statistically significant increase in the effect of pack-years on FEV1/FVC proportion of Native-American and African ancestry. This finding is in contrast to the finding of a prior study.11 One potential explanation for this difference is that the current study recruited Hispanics from multiple geographic regions across the United States unlike the former study which recruited a population from one site in New Mexico, while it is also possible that either or both findings could be false positives given that there were multiple comparisons performed.

Post-bronchodilator spirometry, used to define COPD, was not available in this cohort, however, epidemiologic and genetic risk factors for an obstructive pattern of spirometry are similar to those for COPD37 and we used a contemporary definition of airflow imitation. Emphysema was assessed on partial lung scans. Although we have previously validated percent emphysema measures from these scans compared to full-lung scans in MESA (ICC 0.94),37 the lung apices were not included in the partial lung scans which resulted in less precise effect estimates for smoking-related emphysema, which has an apical predilection.38 Nonetheless, the variability of these partial lung scans was comparable to that defined by full lung scans in other cohort studies.39 It should also be noted that results from this cross-sectional study may not necessarily apply to longitudinal change in lung function and percent emphysema.

Although MESA is a population-based study, participants with clinical cardiovascular disease were excluded; hence the average smoking history was slightly less than the US population.40 The results, then, may not be fully generalizable to populations with heavier smoking exposures and very severe COPD. Lastly, though this study assessed principal components of ancestry which map along global ancestral clines, it is possible studies of locus specific ancestry might yield different findings.

In conclusion, there was no strong evidence that the association of cigarette smoking to airflow limitation and emphysema varied by genetic ancestry in the four main US race/ethnic groups. Risks of smoking appear equally shared across the population.

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGES.

This study asked the question: does genetic ancestry or self-reported race and ethnicity modify the effect of cumulative pack-years of smoking on lung function and emphysema? The study identified no significant interaction between either genetic ancestry or self-reported race/ethnicity on the effect of smoking on lung function and emphysema in a large multi-ethnic cohort of adults in the United States; and addresses a gap in knowledge about the understanding of differential risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING

The MESA and MESA Lung Studies are conducted and supported by the NHLBI (contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95165 and N01-HC-95169 and grants R01 HL-077612, R01 HL-075476, and RC1-HL100543) in collaboration with the MESA and MESA-Lung Investigators. This manuscript has been reviewed by the MESA Investigators for scientific content and consistency of data interpretation with previous MESA publications and significant comments have been incorporated prior to submission for publication. The authors thank the other investigators, staff, and participants of the MESA and MESA-Lung Studies for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA Investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PMA, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1256–76. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):532–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mannino DMHD, Akinbami LJ, Ford ES, Redd SC. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveilance -- United States, 1971-2000. Surveillance Summaries MMWR. 2002:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akinbami LJLX. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among Adults Aged 18 and Over in the United States, 1998-2009. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2011. NCHS Data Brief, no 63. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vollmer WM, Enright PL, Pedula KL, et al. Race and gender differences in the effects of smoking on lung function. Chest. 2000;117(3):764–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.3.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foreman MG, Zhang L, Murphy J, et al. Early-Onset Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Is Associated with Female Sex, Maternal Factors, and African American Race in the COPDGene Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(4):414–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1928OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatila WM, Wynkoop WA, Vance G, et al. Smoking patterns in African Americans and whites with advanced COPD. Chest. 2004;125(1):15–21. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dransfield MT, Davis JJ, Gerald LB, et al. Racial and gender differences in susceptibility to tobacco smoke among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory Medicine. 2006;100(6):1110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aldrich MC, Kumar R, Colangelo LA, et al. Genetic ancestry-smoking interactions and lung function in African Americans: a cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruse S, Sood A, Petersen H, et al. New Mexican Hispanic Smokers Have Lower Odds of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Less Decline in Lung Function Than Non-Hispanic Whites. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(11):1254–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0568OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar R, Seibold MA, Aldrich MC, et al. Genetic ancestry in lung-function predictions. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(4):321–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bild DEBD, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O’Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. American journal of epidemiology. 156(9):871–81. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38(8):904–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coste J, Bouee S, Ecosse E, et al. Methodological issues in determining the dimensionality of composite health measures using principal component analysis: case illustration and suggestions for practice. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):641–54. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Census Bureau Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin Census 2000 Brief. Mar, 2001.

- 19.Ferris BG. Epidemiology Standardization Project. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(Supp 2):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948–68. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hankinson JL, Kawut SM, Shahar E, et al. Performance of American Thoracic Society-recommended spirometry reference values in a multiethnic sample of adults: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) lung study. Chest. 2010;137(1):138–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vollmer WM, Gislason T, Burney P, et al. Comparison of spirometry criteria for the diagnosis of COPD: results from the BOLD study. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):588–97. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00164608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, et al. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234(1):35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman EA, Jiang R, Baumhauer H, et al. Reproducibility and validity of lung density measures from cardiac CT Scans--The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Lung Study. Acad Radiol. 2009;16(6):689–99. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tschirren J, McLennan G, Palagyi K, et al. Matching and anatomical labeling of human airway tree. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2005;24(12):1540–7. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.857653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu S, Hoffman EA, Reinhardt JM. Automatic lung segmentation for accurate quantitation of volumetric X-ray CT images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20(6):490–8. doi: 10.1109/42.929615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Hoffman EA, Reinhardt JM. Atlas-driven lung lobe segmentation in volumetric X-ray CT images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006;25(1):1–16. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.859209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez J, Jiang R, Johnson WC, et al. The association of pipe and cigar use with cotinine levels, lung function, and airflow obstruction: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):201–10. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-4-201002160-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiefer EM, Hankinson JL, Barr RG. Similar relation of age and height to lung function among Whites, African Americans, and Hispanics. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(4):376–87. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson JS, Nettleton JA, Herrington DM, et al. Relation of omega-3 fatty acid and dietary fish intake with brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilation in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1204–13. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shahar E, Folsom AR, Melnick SL, et al. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated acids and smoking-related chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(7):796–801. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilliland FD, Berhane K, McConnell R, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy, environmental tobacco smoke exposure and childhood lung function. Thorax. 2000;55(4):271–6. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.4.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barker DJ, Godfrey KM, Fall C, et al. Relation of birth weight and childhood respiratory infection to adult lung function and death from chronic obstructive airways disease. BMJ. 1991;303(6804):671–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6804.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray RP, Connett JE, Skeans MA, et al. Menthol cigarettes and health risks in Lung Health Study data. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(1):101–7. doi: 10.1080/14622200601078418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson PG, Simpson JL. The overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it? Thorax. 2009;64(8):728–35. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.108027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hogg JC. Pathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2004;364(9435):709–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16900-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gietema HA, Schilham AM, van Ginneken B, et al. Monitoring of smoking-induced emphysema with CT in a lung cancer screening setting: detection of real increase in extent of emphysema. Radiology. 2007;244(3):890–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443061330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MMWR, editor. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged > or = 18 years --- United States, 2009. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. pp. 1135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.