Abstract

Background

The Triatomini and Rhodniini (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) tribes include the most diverse Chagas disease vectors; however, the phylogenetic relationships within the tribes remain obscure. This study provides the most comprehensive phylogeny of Triatomini reported to date.

Methods

The relationships between all of the Triatomini genera and representatives of the three Rhodniini species groups were examined in a novel molecular phylogenetic analysis based on the following six molecular markers: the mitochondrial 16S; Cytochrome Oxidase I and II (COI and COII) and Cytochrome B (Cyt B); and the nuclear 18S and 28S.

Results

Our results show that the Rhodnius prolixus and R. pictipes groups are more closely related to each other than to the R. pallescens group. For Triatomini, we demonstrate that the large complexes within the paraphyletic Triatoma genus are closely associated with their geographical distribution. Additionally, we observe that the divergence within the spinolai and flavida complex clades are higher than in the other Triatoma complexes.

Conclusions

We propose that the spinolai and flavida complexes should be ranked under the genera Mepraia and Nesotriatoma. Finally, we conclude that a thorough morphological investigation of the paraphyletic genera Triatoma and Panstrongylus is required to accurately assign queries to natural genera.

Keywords: Triatomini, Species complex, Monophyly

Background

Chagas disease, or American Trypanosomiasis, is one of the 10 most seriously neglected tropical diseases [1]. It currently affects nine million people [2], and more than 70 million people live under a serious risk of infection [3]. This vector-borne disease is transmitted by triatomine bugs (kissing bugs) infected with the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi[4]. All 148 described species of the Triatominae subfamily (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) are considered potential Chagas disease vectors [5,6].

The Triatominae subfamily includes 15 genera, seven of which comprise the Triatomini tribe, the most diverse, and two of which are assigned to the Rhodniini tribe, the second most diverse concerning species number [6]. In the most recent taxonomic review of this group, the authors suggested synonymisation of the genera Meccus, Mepraia and Nesotriatoma with Triatoma, which is the most diverse genus of the subfamily. The generic status of these groups has been under contention because there is no consensus on whether each group constitutes a species complex or a genus [5-9].

The genus Triatoma is diverse in terms of the number of species (it includes 82) [6,10,11] and morphology. This diversity has led to the division of Triatoma into complexes based on their morphological similarities and geographic distributions [6-9], but no formal cladistic analysis has been performed to corroborate the assignment of these groups.

Although species complexes are not formally recognized as taxonomic ranks and, thus, do not necessarily represent natural groups, we propose that they should be monophyletic. This statement is tightly linked to the idea that once the relationships between vector species are known, information about a species may be reliably extrapolated to other closely related species [12]. Previous molecular phylogenetic studies have shown that some Triatoma complexes are not monophyletic [13,14]. However, most of these molecular analyses were based on a single specimen per species and a single molecular marker.

The Rhodniini tribe comprises two genera: Rhodnius (18 species) and Psammolestes (three species), the former being divided into three species groups, namely, pallescens, prolixus and pictipes[15]. Although the relationship between these groups has not yet been established, with results in the literature conflicting [13,16], it seems that Rhodnius is a paraphyletic lineage, with Psammolestes being closely related to the prolixus group [16].

In this study, we investigated which groups (genera and species complexes) within Triatomini constitute natural groups. To this end, we conducted a comprehensive molecular phylogenetic analysis of Triatomini, pioneering the inclusion of all Triatomini genera, many specimens per species and several markers per sample. We also included representatives of the three Rhodniini groups to further test ingroup monophyly. The results enabled us to accurately classify the higher groups within the Triatomini tribe, to identify monophyletic genera and complexes and to pinpoint which of these groups should be subjected to a rigorous morphological review to accurately assign natural groups.

Methods

Taxon sampling

The sampling strategy applied in this study aimed to include specimens from different populations representing the largest possible diversity of Triatomini to test the validity of current taxonomic assignments. A total of 104 specimens representing 54 Triatomini species were included, including sequences available in GenBank. To further test ingroup monophyly, we also included 10 Rhodniini species. Stenopoda sp. (Stenopodainae: Reduviidae), a member of a distinct subfamily of Reduviidae [17], was selected as the outgroup. The employed Triatominae nomenclature followed the most recently published review on the subfamily [6].

Voucher specimens for all of the adult samples sequenced in this study were deposited in the Herman Lent Triatominae Collection (CT-IOC) at the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, FIOCRUZ. All the information about the specimens can be found in Table 1. Some of the obtained specimens consisted of first-instar nymphs, eggs or adult legs. These specimens were not deposited in the collection because the entire sample was used for DNA extraction. Nevertheless, the identification of these specimens was reliable because they were obtained from laboratory colonies with known identities of the parental generation.

Table 1.

Specimens examined, including laboratory colony source, locality information (when available), voucher depository, ID (unique specimen identifier number), and GenBank accession numbers

| Species | ID | Voucher number | Source | Geographic origen |

Marker |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COI | COII | CytB | 16S | 28S | 18S | |||||

|

D. maxima |

92 |

3465 |

LDP |

México |

KC249306 |

- |

KC249226 |

KC248968 |

KC249134 |

KC249092 |

| 186 |

3520 |

LaTec |

El Triunfo, México |

KC249305 |

KC249399 |

KC249225 |

KC248967 |

- |

- |

|

|

E.mucronatus |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

- |

JQ897794 |

JQ897635 |

JQ897555 |

|

H. matsunoi |

106 |

- |

LNIRTT |

|

- |

KC249400 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Linshcosteus sp. |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

- |

AF394595 |

- |

- |

|

P. geniculatus |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

- |

AF394593 |

- |

- |

|

P. lignarius |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

AF449141 |

- |

- |

AY185833 |

- |

- |

|

P. lutzi |

202 |

3524 |

LTL |

Santa Quitéria, CE, Brazil |

KC249307 |

KC249401 |

KC249227 |

KC248969 |

KC249135 |

- |

|

P. megistus |

128 |

3463 |

LACEN |

Nova Prata, RS, Brazil |

KC249308 |

KC249402 |

KC249228 |

KC248970 |

KC249136 |

- |

| 129 |

3476 |

LACEN |

Boa Vista do Cadeado, RS, Brazil |

KC249309 |

- |

KC249229 |

KC248971 |

KC249137 |

- |

|

| 130 |

3477 |

LACEN |

Tres Passos, RS, Brazil |

- |

- |

KC249230 |

KC248972 |

KC249138 |

- |

|

| 131 |

3478 |

LACEN |

Salvador do Sul, RS, Brazil |

KC249310 |

- |

KC249231 |

KC248973 |

KC249139 |

- |

|

| 132 |

3479 |

LACEN |

Barão do Triunfo, RS, Brazil |

KC249311 |

- |

- |

KC248974 |

KC249140 |

- |

|

| 183 |

3517 |

LaTec |

Pitangui, MG, Brazil |

KC249312 |

KC249403 |

KC249232 |

KC248975 |

KC249141 |

- |

|

|

P. tupynambai |

127 |

3462 |

LACEN |

Dom Feliciano, RS, Brazil |

- |

- |

KC249233 |

KC248977 |

- |

- |

| 138 |

3485 |

LACEN |

Pinheiro Machado, RS, Brazil |

- |

KC249404 |

KC249234 |

KC248978 |

KC249142 |

- |

|

|

Paratriatoma hirsuta |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

- |

FJ230443 |

- |

- |

|

R. brethesi |

197 |

3426 |

LNIRTT |

Acará River, AM, Brazil |

KC249313 |

KC249405 |

KC249235 |

KC248980 |

- |

- |

|

R. colombiensis |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

FJ229360 |

AY035438 |

- |

- |

|

R. domesticus |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

- |

AY035440 |

- |

- |

|

R. ecuadoriensis |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

GQ869665 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

R. nasutus |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

AF435856 |

- |

|

R. neivai |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

AF449137 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

R. pallescens |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

EF071584 |

- |

- |

- |

|

R. pictipes |

200 |

3429 |

LNIRTT |

Bega, Abaetetuba, PA, Brazil |

KC249315 |

KC249408 |

- |

KC248982 |

- |

KC249094 |

|

R. prolixus |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

AF449138 |

- |

- |

- |

AF435862 |

AY345868 |

|

R. stali |

195 |

3424 |

LNIRTT |

Alto Beni, Bolivia |

KC249316 |

KC249409 |

KC249236 |

KC248983 |

- |

- |

|

Stenopoda sp |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

- |

FJ230414 |

FJ230574 |

FJ230493 |

|

T. brasiliensis |

40 |

3384 |

LNIRTT |

Curaçá, BA, Brazil |

KC249319,KC249320 |

KC249415,KC249416 |

KC249240 |

KC248986 |

- |

- |

| 41 |

3385 |

LNIRTT |

Sobral, CE, Brazil |

- |

- |

KC249241 |

KC248987 |

- |

- |

|

| 174 |

3510 |

LaTec |

Tauá, CE, Brazil |

KC249318 |

KC249413 |

KC249239 |

KC248985 |

KC249145 |

- |

|

|

T. breyeri |

56 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Mataral, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249321 |

KC249417 |

KC249242 |

KC248988 |

- |

- |

|

T. bruneri |

98 |

3468 |

LNIRTT |

Cuba |

- |

KC249418 |

- |

KC248989 |

KC249146 |

- |

|

T. carcavalloi |

78 |

3395 |

LNIRTT |

São Gerônimo, RS, Brazil |

KC249322 |

KC249419 |

KC249244 |

KC248991 |

- |

KC249097 |

|

T. circummaculata |

120 |

- |

LNIRTT |

Caçapava do Sul, RS, Brazil |

KC249323 |

KC249421 |

- |

KC248992 |

KC249147 |

KC249098 |

| 121 |

- |

LACEN |

Piratini, RS, Brazil |

KC249324 |

KC249422 |

- |

KC248993 |

- |

- |

|

| 122 |

3473 |

LACEN |

Piratini, RS, Brazil |

KC249325 |

- |

KC249245 |

KC248994 |

KC249148 |

KC249099 |

|

| 126 |

3461 |

LACEN |

Dom Feliciano, RS, Brazil |

- |

- |

- |

KC248996 |

- |

- |

|

|

T. costalimai |

35 |

3381 |

LNIRTT |

Posse, GO, Brazil |

KC249327,KC249328 |

KC249425 |

KC249246 |

KC248997 |

- |

KC249101 |

| 42 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Chiquitania, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249329 |

KC249426 |

KC249247 |

KC248998 |

KC249149 |

- |

|

|

T. delpontei |

53 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Chaco Tita, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249330 |

KC249427 |

KC249248 |

KC248999 |

- |

- |

|

T. dimidiata |

20 |

3444 |

LaTec |

- |

KC249335 |

KC249431 |

- |

KC249004 |

KC249152 |

- |

| 94 |

3466 |

LNIRTT |

Central América |

KC249336,KC249337 |

KC249432 |

- |

KC249005 |

KC249155 |

- |

|

| 100 |

3470 |

LNIRTT |

México |

KC249333 |

- |

- |

KC249002 |

- |

- |

|

|

T. eratyrusiformis |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

GQ336898 |

- |

JN102360 |

AY035466 |

- |

- |

|

T. flavida |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

- |

AY035451 |

- |

AJ421959 |

|

T. garciabesi |

89 |

3405 |

LNIRTT |

Rivadaria, Argentina |

KC249338 |

- |

KC249249 |

KC249006 |

KC249158 |

KC249102 |

|

T. guasayana |

55 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Chaco Tita, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249342 |

- |

KC249251 |

KC249010 |

- |

- |

| 82 |

3398 |

LNIRTT |

Santa Cruz, Bolívia |

KC249343 |

KC249438 |

KC249252 |

KC249011 |

KC249162 |

KC249103 |

|

|

T. guazu |

29 |

3455 |

LNIRTT |

Barra do Garça, MT, Brazil |

- |

KC249440 |

- |

KC249013 |

KC249164 |

KC249105 |

|

T. infestans |

58 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Cotapachi, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249349 |

KC249442 |

KC249256 |

KC249015 |

KC249168 |

KC249109 |

| 60 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Mataral, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249351 |

KC249443 |

KC249257 |

KC249016 |

KC249169 |

KC249107 |

|

| 62 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Ilicuni, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249353 |

KC249445 |

KC249259 |

KC249018 |

- |

- |

|

| 63 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Ilicuni, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249354 |

KC249446 |

KC249260 |

KC249019 |

- |

- |

|

| 66 |

3386 |

LNIRTT |

Guarani das Missões, RS, Brazil |

- |

- |

- |

KC249021 |

- |

- |

|

| 68 |

3388 |

LNIRTT |

Argentina |

- |

- |

- |

KC249023 |

- |

- |

|

| 69 |

3389 |

LNIRTT |

Montevideo, Uruguai |

- |

KC249447 |

KC249262 |

KC249024 |

KC249172 |

- |

|

| 44 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Chaco Tita Cochabamba |

KC249346 |

- |

KC249255 |

KC249025 |

KC249166 |

KC249108 |

|

|

T. juazeirensis |

209 |

3430 |

LTL |

Uiabí, BA, Brazil |

- |

- |

KC249263 |

KC249026 |

KC249173 |

- |

|

T. jurbergi |

30 |

3456 |

LNIRTT |

Alto Garça MT, Brazil |

- |

KC249448 |

KC249264 |

KC249027 |

KC249174 |

KC249110 |

|

T. klugi |

75 |

3393 |

LNIRTT |

Nova Petrópolis, RS, Brazil |

KC249356 |

KC249449 |

KC249265 |

KC249028 |

- |

- |

|

T. lecticularia |

151 |

3411 |

LaTec |

- |

- |

KC249450 |

- |

KC249029 |

KC249175 |

KC249111 |

|

T. longipennis |

26 |

3450 |

LaTec |

- |

- |

KC249453 |

KC249267 |

KC249032 |

- |

- |

| 97 |

3467 |

LNIRTT |

México |

KC249358 |

- |

- |

KC249033 |

- |

- |

|

| 165 |

3501 |

LaTec |

México |

KC249357 |

KC249452 |

- |

KC249031 |

KC249177 |

- |

|

|

T. maculata |

203 |

3525 |

LTL |

Água Fria, RR, Brazil |

- |

KC249454 |

- |

KC249034 |

|

- |

|

T. matogrossensis |

31 |

3374 |

LNIRTT |

Bahia, Brazil |

KC249361 |

KC249458 |

- |

KC249038 |

- |

- |

| 32 |

3375 |

LNIRTT |

Aquidauana , MS, Brazil |

- |

KC249459 |

KC249271 |

KC249039 |

KC249181 |

- |

|

| 33 |

3377 |

LNIRTT |

Alegria, MT, Brazil |

- |

KC249460 |

KC249272 |

KC249040 |

KC249182 |

KC249114 |

|

| 192 |

3423 |

LTL |

São Gabriel D’oeste, MS, Brazil |

KC249360 |

KC249457 |

KC249270 |

KC249037 |

KC249180 |

KC249113 |

|

|

T. mazzottii |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

DQ198805 |

- |

DQ198816 |

AY035446 |

- |

AJ243333 |

|

T. melanica |

- |

3447 |

LaTec |

- |

- |

KC249461 |

- |

KC249041 |

KC249183 |

- |

|

T. melanosoma |

70 |

3390 |

LNIRTT |

Missiones Argentina |

KC249362 |

- |

KC249273 |

KC249042 |

- |

- |

|

T. nitida |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

AF045723 |

AF045702 |

- |

- |

|

T. pallidipennis |

18 |

3442 |

LaTec |

- |

- |

- |

- |

KC249045 |

- |

- |

|

T. phyllosoma |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

DQ198806 |

- |

DQ198818 |

- |

- |

AJ243329 |

|

T. picturata |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

DQ198817 |

AY185840 |

- |

AJ243332 |

|

T. platensis |

96 |

- |

LNIRTT |

Montevideo Uruguai |

- |

- |

KC249274 |

KC249047 |

KC249186 |

- |

|

T. protracta |

93 |

3407 |

LNIRTT |

Monte Diablo, California, EUA |

- |

KC249463 |

- |

KC249048 |

KC249187 |

- |

|

T. pseudomaculata |

34 |

3379 |

LNIRTT |

Curaçá, BA, Brazil |

- |

- |

- |

KC249057 |

KC249196 |

- |

| 211 |

3432 |

LTL |

Várzea Alegre, CE, Brazil |

KC249364 |

KC249464 |

KC249275 |

KC249050 |

KC249189 |

- |

|

| 212 |

3433 |

LTL |

Várzea Alegre, CE, Brazil |

- |

KC249465 |

KC249276 |

KC249051 |

KC249190 |

- |

|

| 214 |

3435 |

LTL |

Várzea Alegre, CE, Brazil |

KC249365 |

KC249467 |

KC249277 |

KC249053 |

KC249192 |

- |

|

|

T. recurva |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

DQ198803 |

- |

DQ198813 |

FJ230417 |

- |

FJ230496 |

|

T. rubrofasciata |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

- |

- |

AY127046 |

- |

AJ421960 |

|

T. rubrovaria |

76 |

3459 |

LNIRTT |

Caçapava do Sul, RS, Brazil |

KC249375 |

KC249477 |

KC249286 |

KC249066 |

- |

- |

| 77 |

3394 |

LNIRTT |

Quevedos, RS, Brazil |

KC249376 |

- |

KC249287 |

KC249067 |

KC249204 |

KC249122 |

|

| 156 |

3416 |

LaTec |

Canguçu, RS, Brazil |

KC249374 |

KC249476 |

KC249285 |

KC249065 |

KC249203 |

KC249121 |

|

| 123 |

3474 |

LACEN |

Piratini, RS, Brazil |

KC249369 |

KC249470 |

- |

KC249058 |

KC249197 |

KC249116 |

|

| 134 |

3481 |

LACEN |

Canguçu, RS, Brazil |

KC249370 |

KC249471 |

KC249281 |

KC249059 |

KC249198 |

KC249117 |

|

| 136 |

3483 |

LACEN |

Pinheiro Machado, RS, Brazil |

KC249372 |

KC249473 |

KC249283 |

KC249061 |

KC249200 |

KC249119 |

|

| 140 |

3487 |

LACEN |

Canguçu, RS, Brazil |

KC249373 |

KC249475 |

- |

KC249064 |

KC249202 |

KC249120 |

|

|

T. sanguisuga |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

- |

JF500886 |

HQ141317| |

AF045696 |

- |

- |

|

T. sherlocki |

80 |

3396 |

LNIRTT |

- |

KC249377 |

KC249478 |

KC249288 |

KC249068 |

KC249205 |

- |

|

T. sordida |

38 |

3382 |

LNIRTT |

Rondonópolis, MT, Brazil |

- |

KC249479 |

- |

KC249071 |

- |

- |

| 46 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Romerillo, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249379,KC249380 |

KC249480 |

- |

KC249072 |

KC249207 |

- |

|

| 47 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Romerillo, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249381,KC249382 |

- |

KC249290 |

KC249073 |

KC249208 |

KC249124 |

|

| 83 |

3399 |

LNIRTT |

La Paz, Bolívia |

KC249383 |

KC249481 |

KC249291 |

KC249074 |

KC249209 |

- |

|

| 85 |

3401 |

LNIRTT |

Pantanal, MS, Brazil |

KC249384 |

KC249482 |

KC249292 |

KC249075 |

KC249210 |

KC249125 |

|

| 86 |

3402 |

LNIRTT |

Santa Cruz, Bolívia |

KC249385 |

- |

KC249293 |

KC249076 |

KC249211 |

- |

|

| 88 |

3404 |

LNIRTT |

San Miguel Corrientes, Argentina |

KC249387 |

KC249484 |

KC249295 |

KC249078 |

KC249213 |

- |

|

| 90 |

3406 |

LNIRTT |

Poconé, MT, Brazil |

KC249388 |

- |

- |

KC249079 |

- |

- |

|

|

Triatoma sp. |

50 |

- |

IIBISMED |

Mataral, Cochabamba, Bolivia |

KC249339 |

KC249435 |

- |

KC249007 |

KC249159 |

- |

|

T. spinolai |

- |

- |

GenBank |

- |

GQ336893 |

- |

JN102358 |

AF324518 |

- |

AJ421961 |

|

T. tibiamaculata |

79 |

3460 |

LNIRTT |

- |

KC249390 |

KC249486 |

KC249297 |

KC249081 |

KC249215 |

- |

| 177 |

3513 |

LaTec |

Mogiguaçu, RS, Brazil |

KC249389 |

KC249485 |

KC249296 |

KC249080 |

KC249214 |

KC249127 |

|

|

T. vandae |

28 |

3452 |

LNIRTT |

Pantanal, MT, Brazil |

KC249391 |

KC249487 |

KC249298 |

KC249082 |

KC249216 |

KC249128 |

| 73 |

3392 |

LNIRTT |

Rio Verde do Mato Grosso, MT, Brazil |

KC249392 |

KC249488 |

KC249299 |

KC249083 |

KC249217 |

KC249129 |

|

| 74 |

3458 |

LNIRTT |

Rondonópolis, MT, Brazil |

KC249393,KC249394 |

KC249489 |

KC249300 |

KC249084 |

KC249218 |

- |

|

|

T. vitticeps |

81 |

3397 |

LNIRTT |

- |

KC249396 |

KC249491 |

KC249303 |

KC249087 |

KC249220 |

KC249132 |

| 91 |

- |

LTL |

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

KC249397 |

KC249492 |

KC249304 |

KC249088 |

KC249221 |

- |

|

| 168 |

3504 |

LaTec |

Itanhomi, MG, Brazil |

KC249395 |

KC249490 |

KC249301 |

KC249085 |

- |

KC249130 |

|

|

T. williami |

36 |

- |

LNIRTT |

- |

- |

KC249493 |

- |

KC249089 |

- |

- |

| T. wygodzynski | 17 |

3441 |

LaTec |

- |

KC249398 |

KC249494 |

- |

KC249090 |

KC249222 |

KC249133 |

| 205 | 3527 | LTL | Sta Rita de Caldas, MG, Brazil | - | - | - | KC249091 | - | - | |

LTL - Laboratório de Transmissores de Leishmanioses, IOC, FIOCRUZ; LaTec - Laboratório de Triatomíneos e epidemiologia da Doença de Chagas, CPqRR, FIOCRUZ; LACEN - Laboratório Central, Rio Grande do Sul, Ministério da Saúde; IIBISMED - Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Mayor de San Simón, Cochabamba, Bolivia.

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

The DNA extraction was performed using the protocol described by Aljanabi and Martinez [18] or using the Qiagen Blood and Tissue kit, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The following PCR cycling conditions were employed: 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 49–45°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; and 72°C for 10 min. The sequences of the primers used for amplification are shown in Table 2. The reaction mixtures contained 10 mM Tris–HCl/50 mM KCl buffer, 0.25 mM dNTPs, 10 μM forward primer, 10 μM reverse primer, 3 mM MgCl2, 2.5 U of Taq polymerase and 10–30 ng of DNA. The primers used to amplify the mitochondrial COI, COII, CytB and 16S and the nuclear ribosomal 18S and 28S markers are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Marker | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| COI |

5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ [19] |

5′-AAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′ [19] |

| 5′-CCTGCAGGAGGAGGAGAYCC-3′ [20] |

5′ - TAAGCGTCTGGGTAGTCTGARTAKCG-3′; [21] |

|

| 5′-ATTGRATTTTDAGTCATAGGGAG-3′ (this study) |

5′-TATTYGTWTGATCDGTWGG-3′ (this study) |

|

| CytB |

5′-GGACG(AT)GG(AT)ATTTATTATGGATC-3′ [22] |

5′-ATTACTCCTCCTAGYTTATTAGGAATT-3′ [23] |

| COII |

5′-ATGATTTTAAGCTTCATTTATAAAGAT-3′ [23] |

5′-GTCTGAATATCATATCTTCAATATCA-3′ [23] |

| 16S |

5′-CGCCTGTTTATCAAAAACAT-3′ [24] |

5′-CTCCGGTTTGAACTCAGATCA-3′ [24] |

| 28S |

5′- AGTCGKGTTGCTTGAKAGTGCAG-3′ [25] |

5′- TTCAATTTCATTKCGCCTT-3′ [25] |

| |

5′-CTTTTAAATGATTTGAGATGGCCTC-3′ (this study) |

- |

| 18S | 5′-AAATTACCCACTCCCGGCA-3′ [24] | 5′-TGGTGUGGTTTCCCGTGT T-3′ [24] |

The PCR-amplified products were purified using the ExoSAP-IT (USB® products), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, and both strands were subsequently sequenced. The sequencing reactions were performed using the ABI Prism® BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems), with the same primers employed for PCR, in ABI 3130 and ABI 3730 sequencers (PDTIS Platform, FIOCRUZ and the Genetics Department of UFRJ, respectively). The obtained sequences were assembled using MEGA 4.0 [26] and SeqMan Lasergene v. 7.0 (DNAStar, Inc.) software.

Sequence alignments and molecular datasets

Different approaches were used to align the coding sequences and the ribosomal DNA markers. The coding sequences were translated and then aligned using ClustalW [27] implemented in MEGA 4.0 [26] software. The ribosomal DNA sequences were aligned using MAFFT [28] with the Q-INS-I option, which takes the secondary RNA structure into consideration.

We first constructed an alignment including all the sequences obtained (Additional file 1: Table S1), but there was too much missing data in this matrix, which included 169 individuals. To minimise the effect of missing data on the analysis, a new alignment was constructed based on the above method with the aim of maximising diversity, considering that each taxon in the dataset had to be comparable to all others, that is, all specimens must include comparable sequences.

The final individual alignments were concatenated by name using SeaView [29], generating a matrix including 115 individuals and 6,029 nucleotides (Table 1). This dataset is available on the Dryad database (http://datadryad.org/) and upon request.

Phylogenetic analyses

jModeltest [30] was used to assess the best fit model for each of the markers. The markers CytB, COII, 18S and 28S fit models less parametric than GTR + Γ (data not shown). Despite this fact, GTR + Γ was used for all the markers as this is the next best model available in the programs used. The use of a more parametric model is supported by the fact that the application of a model less parametric than the “real” model leads to a strong accentuation of errors in the recovered tree [31].

The Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree was obtained through a search of 200 independent runs with independent parsimony starting trees using RAxML 7.0.4 [32]. The alignment was partitioned by marker, and for each partition, the gamma parameter was estimated individually, coupled to the GTR model. To assess the reliability of the recovered clades, 1,000 bootstrap [33] replicates were performed using the rapid bootstrap algorithm implemented in RaxML.

Additionally, a Bayesian approach was applied to reconstruct the phylogeny of the concatenated dataset using MrBayes 3 [34]. The data were also partitioned based on markers, and GTR + Γ (four categories) was used separately for each partition, with the gamma parameter being estimated individually. The trees were sampled every 1,000 generations for 100 million generations in two independent runs with four chains each. Burn-in was set to 50% of the sampled trees.

Results

The recovered phylogenies (ML and BI) yielded very similar trees, with the generated clades supporting their agreement with one another.

The Rhodniini tribe

The Rhodniini tribe (Figure 1, Additional file 2: Figure S1 and Additional file 3: Figure S2) was recovered with high support (BS = 100, PP = 1), as were most relationships within the tribe. The prolixus group was recovered as a sister taxon to the pictipes group (BS = 97, PP = 1), and these groups form a sister clade to the pallescens group. The only species that could not be confidently placed within its clade was R. neivai, which was recovered within the prolixus group as a sister species to R. nasutus, but support was lower (BS = 80, PP = 0.7; Figure 1, Additional file 2: Figure S1 and Additional file 3: Figure S2).

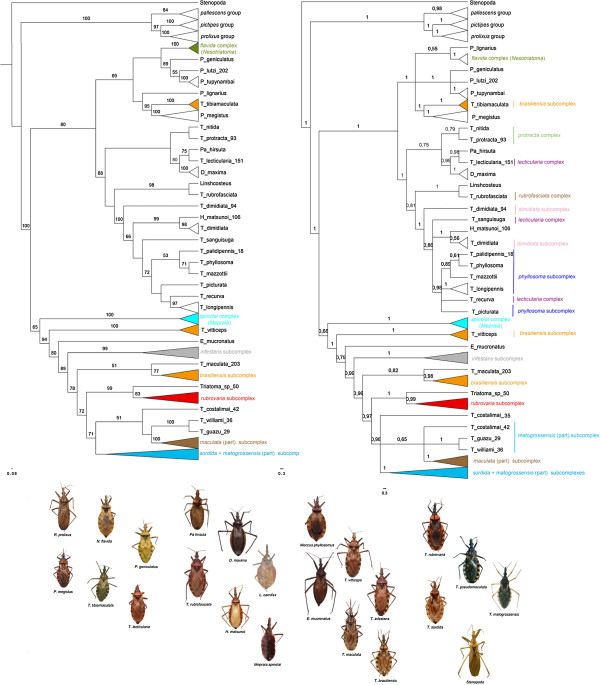

Figure 1.

Best ML tree (on the left) and Bayesian consensus tree (on the right) reconstructed. Bars on the right highlight the non-monophyletic groups. Numbers above branches represent clade support higher than 50 and 0.5, respectively. Triatominae photos by Carolina Dale. Stenopoda spinulosa photo by Brad Barnd. Photos are not to scale.

The Triatomini tribe

The Triatomini tribe was recovered with the highest support (BS = 100, PP = 1). The tribe was shown to be divided into three main lineages: Clade (1), Panstrongylus + the flavida complex (Nesotriatoma) + T. tibiamaculata (BS = 69, PP = 1); Clade (2), the monotypic genera (Hermanlentia, Paratriatoma, Dipetalogaster) + Linshcosteus + Northern Hemisphere Triatoma (BS = 88, PP = 1); and Clade (3), Southern Hemisphere Triatoma (including the spinolai complex or Mepraia) and Eratyrus (BS = 65, PP = 0.68).

Clade (1): Panstrongylus + the flavida complex (Nesotriatoma) + T. tibiamaculata

The flavida complex (Nesotriatoma) was recovered with the highest support in all three phylogenies, showing a close relationship with the clade formed by P. geniculatus + P. lutzi + P. tupynambai. P. megistus was placed as a sister taxon to T. tibiamaculata (BS = 95, PP = 1); while P. lignarius could not be confidently placed in the clade (BS < 50, PP = 0.55).

Clade (2): the monotypic genera (Hermanlentia, Paratriatoma, Dipetalogaster) + Linshcosteus + Northern Hemisphere Triatoma

In this clade, the phylogenies showed close relationships among Paratriatoma (Pa.), Dipetalogaster and T. nitida, T. protracta (protracta complex) and T. lecticularia (lecticularia complex). Pa. hirsuta was always recovered as a sister species to T. lecticularia (BS = 75, PP = 0.98), and this pair was sister to D. maxima (BS = 80, PP = 0.99). The indicated species from the protracta complex were always recovered as a single clade that was closely related to D. maxima, Pa. hirsuta and T. lecticularia.

The tropicopolitan T. rubrofasciata species was recovered as a sister species to Linshcosteus in both phylogenies with high support (BS = 98, PP = 1). This pair of species is closely related to the clade formed by the dimidiata subcomplex + T. sanguisuga (lecticularia subcomplex) + Hermanlentia matsunoi + the phyllosoma subcomplex + T. recurva (BS = 100, PP = 1).

H. matsunoi appeared as a sister taxon to T. dimidiata from Mexico with high support (BS = 99, PP = 1). The phyllosoma subcomplex was not recovered as monophyletic as T. recurva was recovered close to T. longipennis, although the bootstrap for this clade was not high (BS = 72, PP = 0.98).

Clade (3) Southern Hemisphere Triatoma and Eratyrus

This clade was formed by the spinolai complex and the species assigned to the infestans complex, which were not recovered as monophyletic. The spinolai complex was recovered as monophyletic (BS = 100, PP = 1) in both phylogenies, and as sister taxa to the infestans complex.

T. vitticeps was recovered as a sister taxon to E. mucronatus and to the remaining Southern Hemisphere Triatoma subcomplexes of the infestans (BS = 94, PP = 1). The infestans and rubrovaria subcomplexes were recovered as monophyletic (BS = 99, PP = 1 and BS = 83, PP = 0.99, respectively). In addition, the rubrovaria subcomplex was closely related to a short-winged Triatoma sp. (BS = 99, PP = 1) that resembles T. guasayana, which was discovered in the bromeliads of the Bolivian Chaco by F. Noireau.

T. maculata was not closely related to the other species of the maculata subcomplex. This taxon clustered with the brasiliensis subcomplex (BS = 51, PP = 0.82), except for T. tibiamaculata and T. vitticeps, which clustered elsewhere. The remaining species of the maculata subcomplex clustered in a large clade with the sordida and matogrossensis subcomplexes (BS = 71, PP = 0.98).

Discussion

Phylogenetic analyses

The reconstructed phylogenies presented in this report showed similar topologies and consistent branch support values. The posterior probability values were almost always higher than the bootstrap values, as expected [31] (Additional file 2: Figure S1 and Additional file 3: Figure S2).

Nonetheless, deep relationships, such as those between complexes, could be resolved. In addition, relationships within the infestans subcomplexes remain unclear (Additional file 2: Figure S1 and Additional file 3: Figure S2). The short terminal branches of these subcomplexes indicate that their diversification must have occurred recently. Under this scenario, incomplete lineage sorting would account for the lack of phylogenetic resolution within the group [35].

A different approach will be adopted in future studies to assess the relationships between closely related species that could not be resolved here. New unlinked nuclear markers, especially those linked to development and reproduction [36], will be sequenced to generate a species tree reconstruction [37], which is a more suitable method of phylogenetic reconstruction for closely related species.

The Rhodniini tribe

The Rhodniini tribe comprises only 2 genera: Rhodnius and Psammolestes. Rhodnius has long been known to be easily distinguishable from other Triatominae, but the morphological discrimination of the species within Rhodnius is rather difficult [38]. Moreover, there is no uncertainty in the literature regarding the species groups assigned within Rhodnius; the uncertainty is related to the relationships between these groups.

Previously described molecular phylogenies of these genera have yielded distinct results. For instance, Lyman et al.[16] showed the pallescens group to be more closely related to the pictipes group, but Hypsa et al.[13] found the pictipes group to be closer to the prolixus group, which is consistent with our results. This difference could be due to differences in taxon sampling rather than differences in the gene trees, as both of these authors used mitochondrial markers. In this work, the taxon sampling process included a larger number of species than were included by Lyman et al.[16] (see also [13]). Wiens and Tiu [39] demonstrated that the addition of taxa should improve the accuracy of a phylogenetic reconstruction. The amount of data (less than 10% of the size of our alignment) from Hypsa et al.[13] was overturned by their taxon sampling, which included twice the number of species as the first work.

The Triatomini tribe

The Triatomini tribe is the most diverse tribe within the subfamily, and many taxonomic proposals have been put forth for the groups belonging to this tribe. The most prominent of these proposals is that Meccus, Mepraia and Nesotriatoma be considered as genera or species complexes belonging to Triatoma[5,6,8]. Dujardin et al.[40] noted these confusing systematics with another example: the number of monotypic genera within the tribe and the number of subspecies (at times also considered separate species) assigned to Triatomini. Figure 1, based on our results, highlights the most accepted Triatomini groups that are not monophyletic. We show that Triatoma and Panstrongylus are not natural groups. However, diversities formerly placed under the generic names Mepraia and Nesotriatoma, but not Meccus, consist of monophyletic lineages.

Therefore, based on our results, we indicate that Mepraia and Nesotriatoma should be ranked as genera, as previously proposed [5]. The branch lengths of the reconstructed phylogenies (Figure 1, Additional file 2: Figure S1 and Additional file 3: Figure S2) showed much greater distances between the species assigned to each of these genera than within the other Triatoma complexes. In addition, if the species belonging to Nesotriatoma are considered a species complex of another genus, it is reasonable to include these species in the genus Panstrongylus.

Previous studies have indicated a putative paraphyletic status for Panstrongylus, despite a lack of resolution in some groups [13,14,41,42]. In our topology, Panstrongylus is clearly divided into two groups: one including P. tupynambai, P. lutzi and P. geniculatus as sister taxa to Nesotriatoma and another group showing a close and highly supported relationship between T. tibiamaculata and P. megistus.

The most prominent morphological characteristic that separates Panstrongylus from other Triatomini is the short head of these species, with antennae close to the eyes [8]. The non-monophyletic status of Panstrongylus (Figure 1; see also [14]) indicates that this putative diagnostic characteristic of the genus might be a morphological convergence. Indeed, some Panstrongylus populations show variation in eye size according to their habitat, and this variation influences the distances between the antennae and the eyes [43]. Panstrongylus species tend to present Triatoma-like head shapes [43] during development when the nymphs exhibit smaller eyes. Furthermore, North American Triatoma may display smaller heads and antennae that are closer to the eyes than their South American counterparts[6].

Triatoma is composed of two distinct paraphyletic groups: one occurring in the Northern hemisphere and the other in the Southern Hemisphere; one exception found in the present work was T. tibiamaculata, which clusters with Panstrongylus elsewhere. The previous assignments of Triatoma species into complexes took into consideration the geographical distributions of the groups and their morphological features (e.g. [6]). Our results clearly indicate that monophyletic clades of Triatoma species, which do not necessarily correspond to these complexes, are correlated with restricted geographical distributions corresponding to different biogeographical provinces [44]. This is particularly evident in South America.

Northern Hemisphere Triatoma and the less diverse genera

T. lecticularia is sister to Pa. hirsuta. This pair of species is closely related to D. maxima, which is a genus whose head shape resembles a large Triatoma. Furthermore, Pa. hirsuta exhibits a head shape similar to T. lecticularia, which was observed by Lent and Wygodzinsky [8].

H. matsunoi, which was included in a phylogenetic study for the first time in the present work, was recovered as the sister taxon to the Mexican lineage of T. dimidiata. H. matsunoi was first described as belonging to Triatoma[45] based on the main features used to characterise the Triatomini genera. Subsequently, Jurberg and Galvão [46] found major differences in the male genitalia of this species relative to other Triatomini and reassigned it to a new monotypic genus.

T. rubrofasciata appears to be the species that is closest to Linshcosteus, which is the only Triatomini genus exclusively from the Old World, more precisely, from India. Although we did not include Old World Triatoma in our analyses, previous morphometric analyses have shown Linshcosteus to be distinct from Old world Triatoma and from the closely related species T. rubrofasciata from the New World [47].

The dimidiata subcomplex was not recovered as a natural group because the two sampled T. dimidiata s.l. lineages [48] did not cluster, and the clade also included T. lecticularia and H. matsunoi. Consistent with our results, Espinoza et al.[49] recently published a reconstructed phylogeny showing the relationships among the North American Triatoma species. They included T. gerstaeckeri and T. brailovskyi (not included here) in their analysis and demonstrated the close relationships between these species and those from the dimidiata and phyllosoma subcomplexes, confirming the need to review these groups.

Southern Hemisphere Triatoma

Most subcomplexes assigned to the infestans complex were not recovered as monophyletic. The only natural groups recovered were the infestans and rubrovaria subcomplexes.

As noted above, most of the monophyletic clades recovered for these Triatoma can be associated with a South American biogeographical province. This shows that geographical distribution currently has greater importance than morphology in the process of assigning natural groups to the genus. Henceforth, the geographical provinces (related to biomes) will be referred to as described in Morrone [44].

T. vitticeps, the first Triatoma lineage to diverge in this clade, is found in the Atlantic Forest and shares morphological similarities with the unsampled species T. melanocephala[6], which is a rare species found exclusively in northeastern Brazil [50]. Although both species were assigned to the former brasiliensis complex ([6]), both our results and the number of sex chromosomes in these species, which differs from the other Southern Hemisphere Triatoma, would exclude them from this group [50].

The next lineage to diverge in this clade was Eratyrus mucronatus. The genus Eratyrus differs from Triatoma in displaying a long spine-shaped posterior process of the scutellum and a long first rostral segment, which is nearly as long as the second segment [8]. Although we did not include E. cuspidatus in our analysis, the morphology of this genus is rather distinct, and apart from its phylogenetic position within Triatoma, this species is not a subject of “systematic dispute” in the literature.

Triatoma maculata appears as the sister taxon to part of the brasiliensis subcomplex (except T. tibiamaculata and T. vitticeps). Previous studies have demonstrated the close relationships among some species in the brasiliensis subcomplex [51]. However, these studies did not include T. maculata in their analyses. In contrast, an earlier study revealed a possible close relationship between T. brasiliensis and T. maculata[13]. T. maculata is exclusively found in the Amazonian forest, while the brasiliensis subcomplex is exclusive to the Caatinga province in northeastern Brazil.

The species assigned to the infestans, sordida, and rubrovaria subcomplexes currently exhibit overlapping distributions as they all occur in the Chacoan dominion. The infestans subcomplex was found to be monophyletic, with its distribution occurring mainly in Chaco province. It is important to highlight that only sylvatic populations were considered for this designation because T. infestans shows a distribution related to human migration in most Southern American countries [52].

The Triatoma sp. informally described by François Noireau as a short-winged form of T. guasayana appears as the sister taxon to the rubrovaria subcomplex. This previously undescribed species was collected in Chaco province from bromeliads, which form a different microhabitat than the rock piles in which rubrovaria species are usually found [53]. Conversely, the rubrovaria subcomplex is restricted to Pampa province and the Paraná dominion. As Pampa and Chaco provinces belong to the Chacoan dominion, Triatoma sp. and the rubrovaria complex inhabit historically related areas [44], we predict that microhabitat adaptations account for the morphological divergence observed between these groups.

The most morphologically diverse clade includes species from the sordida, maculata (except for T. maculata) and matogrossensis subcomplexes. This is also the most widespread group in South America and occupies most of Cerrado and Chaco provinces.

Conclusions

Our results show that a thorough evolutionary mapping of the morphological characteristics of Triatomini is long overdue. For example, head shape, which was previously used to distinguish Panstrongylus from Triatoma, does not appear to be a reliable characteristic; the highly supported P. megistus + T. tibiamaculata sister taxa corroborate this conclusion.

In addition, the only published cladistic analysis of a Triatominae group, for Panstrongylus[8], does not agree with our results, though this might be due to the fact that Nesotriatoma and T. tibiamaculata were not included in their analysis. We have shown that the genus Triatoma and a majority of the Triatoma species complexes are not monophyletic. Knowledge of morphologies and the evolutionary histories of morphological traits are imperative in assigning natural groups. In the case of Triatomini, such knowledge is particularly relevant due to the epidemiological importance of these organisms [12].

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SAJ designed the study, acquired data (specimen acquisition and sequencing), performed all the analyses, interpreted the results, and drafted and reviewed the manuscript. CAMR designed the study, acquired data (specimen acquisition), interpreted the results and reviewed the manuscript. JRSM acquired data (specimen acquisition), interpreted the results and reviewed the manuscript. MTO acquired data (specimen acquisition), interpreted the results and reviewed the manuscript. CG designed the study, acquired data (specimen acquisition), interpreted the results and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

All specimens obtained, including laboratory colony source, locality information (when available), voucher depository, ID (unique specimen identifier number),and GenBank accessionnumbers. LTL - Laboratório de Transmissores de Leishmanioses, IOC, FIOCRUZ; LaTec - Laboratório de Triatomíneos e epidemiologia da Doença de Chagas, CPqRR, FIOCRUZ; LACEN - Laboratório Central, Rio Grande do Sul, Ministério da Saúde; IIBISMED - Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Mayor de San Simón, Cochabamba, Bolivia.

The best ML tree obtained. The numbers above branches refer to bootstrap values.

The Bayesian consensus tree obtained. The burn-in was set at 50% of the sampled trees, and the posterior probabilities are shown above branches.

Contributor Information

Silvia Andrade Justi, Email: silvinhajusti@gmail.com.

Claudia A M Russo, Email: Claudia@biologia.ufrj.br.

Jacenir Reis dos Santos Mallet, Email: jacenir@ioc.fiocruz.br.

Marcos Takashi Obara, Email: marcos.obara@gmail.com.

Cleber Galvão, Email: clebergalvao@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Diotaiuti (LaTec, CPqRR, FIOCRUZ) and A.C.V. Junqueira (LDP, IOC, FIOCRUZ) for samples, C. Dale (LNIRTT) and A.E.R. Soares (LBETA) for reviewing the manuscript and PDTIS-FIOCRUZ for the use of their DNA sequencing facilities. SA Justi is supported by a scholarship from the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq), and this study is part of the requirement for her doctorate at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro under the supervision of CAM Russo. We dedicate this study to the memory of Dr. François Noireau.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Roadmap Inspires Unprecedented Support to Defeat Neglected Tropical Diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield CJ, Jannin J, Salvatella R. The future of Chagas disease control. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coura JR. Chagas disease: what is known and what is needed – a background article. Mem I Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:113–122. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007000900018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas CRJ. Nova tripanozomiaze humana: estudos sobre a morfolojia e o ciclo evolutivo do Schizotrypanum cruzi n. gen, n. sp, ajente etiolojico de nova entidade morbida do homem. Mem I Oswaldo Cruz. 1909;1:159–218. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761909000200008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galvão C, Carcavallo R, Rocha DS, Jurberg J. A checklist of the current valid species of the subfamily Triatominae Jeannel, 1919 (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) and their geographical distribution, with nomenclatural and taxonomic notes. Zootaxa. 2003;202:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield CJ, Galvão C. Classification, evolution, and species groups within the Triatominae. Acta Trop. 2009;110:88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usinger RL, Wygodzinsky P, Ryckman RE. The biosystematics of Triatominae. Ann Rev Entomol. 1966;11:309–330. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.11.010166.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lent H, Wygodzinsky P. Revision of the Triatominae (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) and their significance as vectors of Chagas disease. B Am Mus Nat Hist. 1979;163:123–520. [Google Scholar]

- Carcavallo RU, Jurberg J, Lent H, Noireau F, Galvão C. Phylogeny of the Triatominae (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Proposals for taxonomic arrangements. Entomol Vect. 2000;7(Supp l1):1–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves TCM, Teves-Neves SC, Santos-Mallet JR, Carbajal-de-la-Fuente AL, Lopes CM. Triatoma jatai sp. nov. in the state of Tocantins, Brazil (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) Mem I Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:429–437. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276108042013006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurberg J, Cunha V, Cailleaux S, Raigorodschi R, Lima MS, Rocha DS, Moreira FFF. Triatoma pintodiasi sp. nov. do subcomplexo T. rubrovaria (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae) Rev Pan-Amaz Saúde. 2013;4:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer CW. Triatominae (Hemiptera: Reduviidae): systematic questions and some others. Neotrop Entomol. 2003;32:1–10. doi: 10.1590/S1519-566X2003000100001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hypsa V, Tietz DF, Zrzavý J, Rego RO, Galvão C, Jurberg J. Phylogeny and biogeography of Triatominae (Hemiptera: Reduviidae): molecular evidence of a New World origin of the Asiatic clade. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2002;23:447–457. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcilla A, Bargues MD, Abad-Franch F, Panzera F, Carcavallo RU, Noireau F, Galvão C, Jurberg J, Miles MA, Dujardin JP, Mas-Coma S. Nuclear rDNA ITS-2 sequences reveal polyphyly of Panstrongylus species (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae), vectors of Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Genet Evol. 2002;1:225–235. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1348(02)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad-Franch F, Monteiro FA, Jaramillo ON, Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Dias FB, Diotaiuti L. Ecology, evolution, and the long-term surveillance of vector-borne Chagas disease: a multi-scale appraisal of the tribe Rhodniini (Triatominae) Acta Trop. 2009;110:159–177. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman DF, Monteiro FA, Escalante AA, Cordon-Rosales C, Wesson DM, Dujardin JP, Beard CB. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation among triatomine vectors of Chagas’ disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:377–386. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirauch C. Cladistic analysis of Reduviidae (Heteroptera:Cimicomorpha) based on morphological characters. Syst Entomol. 2008;33:229–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2007.00417.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aljanabi SM, Martinez I. Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high quality genomic DNA for PCR based techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4692–4693. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Botech. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbi SR, Benzie J. Large mitochondrial DNA differences between morphologically similar Penaeid shrimp. Mol Mar Biol Biotech. 1991;1:27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JD, Bass AL, Bowen BW, Clark WH Jr. Molecular phylogeny and biogeog- raphy of the marine shrimp Penaeus. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1998;10:399–407. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1998.0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro FA, Barrett TV, Fitzpatrick S, Cordon-Rosales C, Feliciangeli D, Beard CB. Molecular phylogeography of the Amazonian Chagas disease vectors Rhodnius prolixus and R. robustus. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:997–1006. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson PS, Gaunt MW. Phylogenetic multilocus codon models and molecular clocks reveal the monophyly of haematophagous reduviid bugs and their evolution at the formation of South America. Mol Phyl Evol. 2010;56:608–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirauch C, Munro JB. Molecular phylogeny of the assassin bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae), based on mitochondrial and nuclear ribosomal genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009;53:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich CH, Rakitov RA, Holmes JL, Black WC 4th. Phylogeny of the major lineages of Membracoidea (Insecta: Hemiptera: Cicadomorpha) based on 28S rDNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2001;18:293–305. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2000.0873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Toh H. Improved accuracy of multiple ncRNA alignment by incorporating structural information into a MAFFT-based framework. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:212. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:221–224. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. ModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1253–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erixon P, Svennblad B, Britton T, Oxelman B. Reliability of Bayesian posterior probabilities and bootstrap frequencies in phylogenetics. Syst Biol. 2003;52:665–673. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan JH. In: Estimating Species Trees: Practical and Theoretical Aspects. Knowles LL, Kubatko LS, editor. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. Probabilities of gene tree topologies with intraspecific sampling given a species tree; pp. 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Avila ML, Tekiel V, Moretti G, Nicosia S, Bua J, Lammel EM, Stroppa MM, Burgos NMG, Sánchez DO. Gene discovery in Triatoma infestans. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:39. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles LL, Kubatko LS. In: Estimating Species Trees: Practical and Theoretical Aspects. Knowles LL, Kubatko LS, editor. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. Estimating species trees: an introduction to concepts and models; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Neiva A, Pinto C. Estado actual dos conhecimentos sôbre o gênero Rhodnius Stål, com a descripção de uma nova especie. Brasil Med. 1923;37:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wiens JJ, Tiu J. Highly incomplete taxa can rescue phylogenetic analyses from the negative impacts of limited taxon sampling. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Costa J, Bustamante D, Jaramillo N, Catalá S. Deciphering morphology in Triatominae: the evolutionary signals. Acta Trop. 2009;110:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargues MD, Marcilla A, Dujardin JP, Mas-Coma S. Triatomine vectors of Trypanosoma cruzi: a molecular perspective based on nuclear ribosomal DNA markers. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96(Suppl 1):S159–S164. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paula AS, Diotaiuti L, Schofield CJ. Testing the sister-group relationship of the Rhodniini and Triatomini (Insecta: Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;35:712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JS, Barbosa SE, Feliciangeli MD. On the genus Panstrongylus Berg 1879: evolution, ecology and epidemiological significance. Acta Trop. 2009;110:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrone JJ. Biogeographic areas and transition zones of Latin America and the Caribbean islands based on panbiogeographic and cladistic analyses of the entomofauna. Ann Rev Entomol. 2006;51:467–494. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Loayza R. Triatoma matsunoi nueva especie del norte peruano (Hemiptera, Reduviidae: Triatominae) Rev Per Entomol. 1989;31:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jurberg J, Galvão C. Hermanlentia n. gen. da tribo Triatomini, com um rol de espécies de Triatominae (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) Mem I Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Gorla DE, Dujardin JP, Schofield CJ. Biosystematics of Old World Triatominae. Acta Trop. 1997;63:127–140. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(97)87188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn PL, Calderon C, Melgar S, Moguel B, Solorzano E, Dumonteli E, Rodas A, de la Rua N, Garnica R, Monroy C. Two distinct Triatoma dimidiata (Latreille, 1811) taxa are found in sympatry in Guatemala and Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza B, Martínez-Ibarra JA, Villalobos G, De La Torre P, Laclette JP, Martínez-Hernández F. Genetic variation of North American Triatomines (Insecta: Hemiptera: Reduviidae): initial divergence between species and populations of Chagas disease vector. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:275–284. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alevi KC, Mendonça PP, Pereira NP, Rosa JA, Oliveira MT. Karyotype of Triatoma melanocephala Neiva and Pinto (1923). Does this species fit in the Brasiliensis subcomplex? Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:1652–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro FA, Donnelly MJ, Beard CB, Costa J. Nested clade and phylogeographic analyses of the Chagas disease vector Triatoma brasiliensis in Northeast Brazil. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias JCP, Silveira AC, Schofield CJ. The impact of Chagas disease control in Latin America - a review. Mem I Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:603–612. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762002000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt MW, Miles MA. The ecotopes and evolution of triatomine bugs (Triatominae) and their associated trypanosomes. Mem I Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95:557–565. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762000000400019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

All specimens obtained, including laboratory colony source, locality information (when available), voucher depository, ID (unique specimen identifier number),and GenBank accessionnumbers. LTL - Laboratório de Transmissores de Leishmanioses, IOC, FIOCRUZ; LaTec - Laboratório de Triatomíneos e epidemiologia da Doença de Chagas, CPqRR, FIOCRUZ; LACEN - Laboratório Central, Rio Grande do Sul, Ministério da Saúde; IIBISMED - Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Mayor de San Simón, Cochabamba, Bolivia.

The best ML tree obtained. The numbers above branches refer to bootstrap values.

The Bayesian consensus tree obtained. The burn-in was set at 50% of the sampled trees, and the posterior probabilities are shown above branches.