Abstract

Metazoan tissues have the ability to maintain tissue size and morphology while eliminating aberrant or damaged cells. In the tissue homeostasis system, cell division is the primary strategy cells use not only to increase tissue size during development but also to compensate for cell loss in tissue repair. Recent studies in Drosophila, however, have shown that cells in post-mitotic tissues undergo hypertrophic growth without division, contributing to tissue repair as well as organ development. Indeed, similar compensatory cellular hypertrophy (CCH) can be observed in different contexts such as mammalian hepatocytes or corneal endothelial cells. Here we highlight these findings and discuss the underlying mechanisms of CCH, which is likely an evolutionarily conserved strategy for homeostatic tissue growth in metazoans.

Keywords: compensatory proliferation, compensatory cellular hypertrophy, tissue homeostasis, cell competition, post-mitotic tissue, Drosophila follicle cells

An introduction to tissue homeostasis

The cellular communities organizing metazoan tissues have an ability to maintain their integrity and organ size. A critical mechanism for tissue homeostasis involves cell turnover, through which specific types of old differentiated cells are regularly eliminated and replaced by new cells produced from adult stem cells [1]. When abrupt cell death caused by stressors or damage leads to cell loss, activation of apoptosis can induce additional divisions of the surrounding cells, a process termed apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation [2]. In these processes, the number of cells that divide must match the number that die, to maintain equilibrium between cell death and cell division of adult stem cells and their descendants. In tissues where stem cells are not readily available or tissue-intrinsic genetic programs constrain cell division, recent studies in Drosophila suggest that cellular hypertrophy through polyploidization or cell fusion represents a different strategy for tissue homeostasis [3, 4]. In this review, we focus on compensatory cellular hypertrophy (CCH) as a conserved homeostasis strategy to repair damaged post-mitotic tissues.

Compensatory proliferation in tissue repair

In proliferating epithelial tissues, dying cells normally induce their neighbors to divide to compensate for the lost space [5]. This compensatory proliferation has been used to describe tissue repair at the cellular level. The mechanisms of compensatory proliferation have been intensely studied in Drosophila developing epithelial tissues, called imaginal discs. Previous studies using Drosophila wing imaginal discs showed that irradiation-induced cell death was followed by compensatory proliferation resulting in adult wings of nearly normal size [6, 7]. Another study, using toxins to induce ectopic cell death in wing discs, showed that the cells adjacent to the apoptotic cells undergo compensatory proliferation [8]. In addition, a recent study showed that apoptotic cells in Drosophila imaginal discs are responsible for the induction of compensatory proliferation in neighboring cells through secretion of mitogenic signals [9–11] (Figure 1). The apoptotic cells up-regulated the expression of the Caspase-9-like initiator Caspase DRONC [12], which activates the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway to coordinate apoptosis and compensatory proliferation [13]. JNK activation in turn leads to upregulation of growth-promoting signals such as Wingless (Wg; the Drosophila Wnt homolog) and Decapentaplegic (Dpp; the Drosophila TGF-β homolog) to induce the proliferation of surrounding cells [10, 11] (Figure 1). Several recent studies in Drosophila also showed that dMyc, a Drosophila homolog of the c-myc proto-oncogene; Unpaired, a Drosophila homolog of JAK/STAT pathway-activating cytokine interleukin-6, and Yorkie, the Drosophila homolog of the Hippo pathway transducer Yap, are required downstream of JNK signaling for compensatory proliferation [14–17].

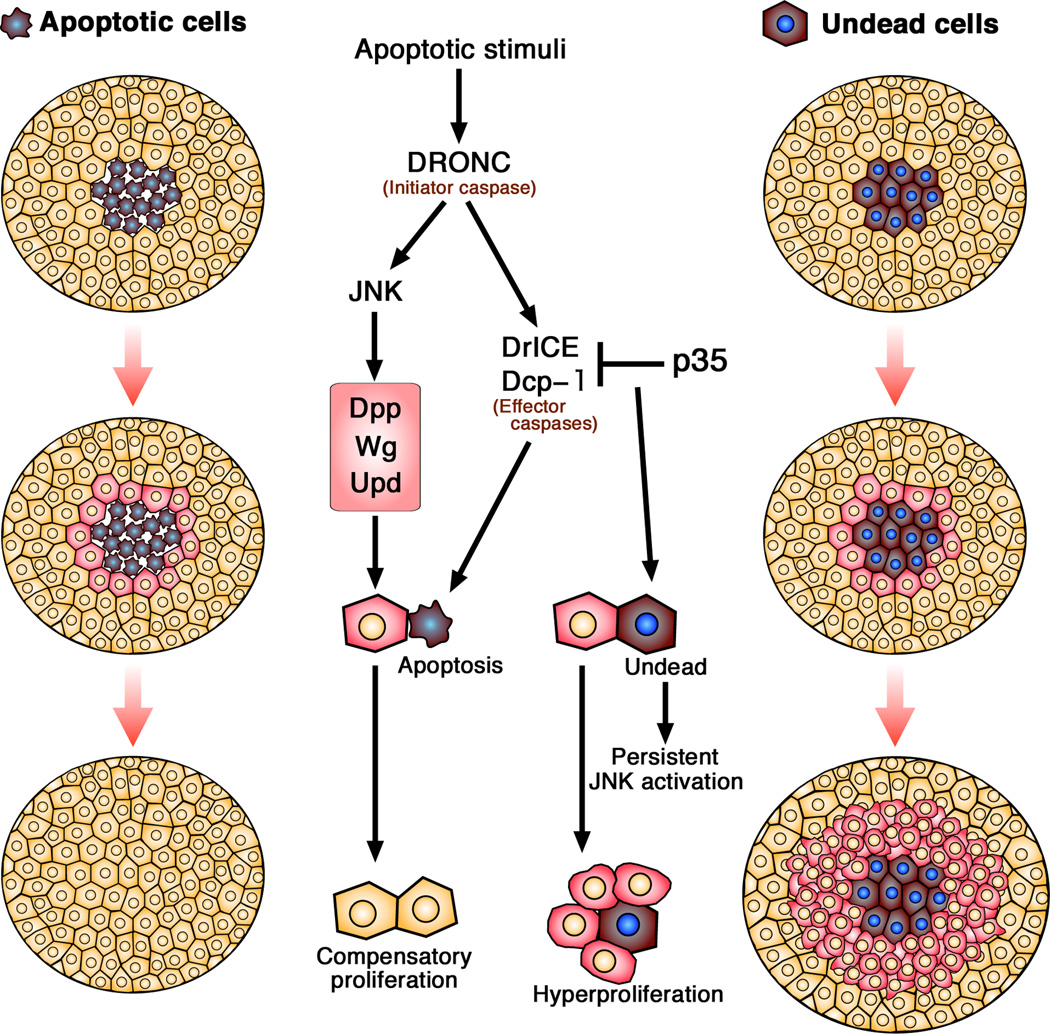

Figure 1.

Compensatory proliferation in Drosophila epithelia. When apoptosis is induced by apoptotic stimuli, initiator caspases (DRONC in Drosophila) cleave specific substrates including the zymogens of effector caspases (DrICE and Dcp-1 in Drosophila), which are activated by the cleavage. The activated effector caspases elicit apoptotic cell death. In apoptotic cells, JNK activation up-regulated by DRONC induces expression of mitogenic signals such as Dpp, Wg or Upd to promote compensatory proliferation of neighboring cells. Expression of baculovirus caspase inhibitor, p35, can suppress the function of effector caspases. When apoptosis is inhibited by p35, persistent JNK activity in the “undead” cells induces hyperproliferation in the neighboring cells.

When the apoptotic cells are kept alive by the expression of baculovirus caspase inhibitor, p35, hyperplastic overproliferation eventually leading to tumorigenesis is induced in the neighboring cells because of persistent JNK activity in the “undead” cells [18] (Figure 1). This undead-cell-induced tumorigenesis in the neighboring tissues clearly shows the mechanism by which signaling molecules from dying cells induce compensatory proliferation in neighboring cells. A second mechanism of apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation has been observed in Drosophila eye imaginal discs [2]. Although Dpp and Wg signaling is preferentially employed in proliferating imaginal tissues, this study showed that, in differentiating eye tissues, the effector caspases DrICE (Drosophila ICE) and Dcp-1 activate the Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway to induce compensatory proliferation [19] (Figure 1). Activation of these effector caspases in the apoptotic photoreceptor neurons stimulates Hh signaling, which induces cell-cycle reentry, suggesting that different caspases trigger distinct forms of compensatory proliferation depending on the developmental state of the tissue [2, 19].

Cellular hypertrophy in tissue repair

Compensatory proliferation is a tissue repair system observed in proliferating tissues where cells have the ability to undergo mitosis. Therefore, can cells that have left the mitotic cycle compensate for cell loss in post-mitotic tissues? Recent work in Drosophila suggests that post-mitotic cells can undergo hypertrophic cell growth to compensate for the lost tissue in a process termed compensatory cellular hypertrophy (CCH). Here we discuss various systems in Drosophila and mammals that can undergo CCH.

CCH in Drosophila post-mitotic follicular epithelia

A recent study in Drosophila follicular epithelium (FE) showed that some types of aberrant mutant cells are eliminated by neighboring normal cells through cell competition even in the post-mitotic tissue (Box 1). Drosophila follicle cells undergo mitotic divisions up to oogenesis stage 6, after which they switch into three rounds of endoreplication during stages 7–10A. At stage 10B, they leave the endocycle, and the main-body follicle cells (a single layer of columnar epithelium surrounding the oocyte) undergo synchronized amplification of genomic loci encoding eggshell proteins [20]. Therefore, the follicular epithelium (FE) after stage 7 is a non-proliferating post-mitotic tissue. When cell competition was induced in the post-mitotic FE, loser cells underwent apoptosis and were eliminated, but no hole was left in the epithelial tissue and integrity of the epithelium was maintained [3], indicating that the loss of some cells from the post-mitotic epithelium was compensated. During the post-mitotic cell competition, however, the neighboring wild-type cells did not undergo compensatory proliferation, but instead compensated for the cell loss through CCH.

Box 1. Cell competition and CCH.

Cell competition is observed in genetically heterogeneous tissues of multicellular organisms when neighboring cells have different cellular fitness. Although what defines cellular fitness and how cells sense differences in cellular fitness are unclear, cellular growth rate and anabolic activity have been considered major factors to be compared between neighboring cells [61–65]. During cell competition, loser cells are normally viable when grown only with other loser cells; when they coexist with fitter winner cells, they are at a growth disadvantage and undergo apoptosis [61–65]. The region previously occupied by the loser cells is replaced by neighboring winner cells through compensatory proliferation of winner cells [66, 67]. The inhibition of apoptosis in loser cells can make them stay alive with winner cells, but does not induce tumorigenic overproliferation in neighboring tissues [67, 68], unlike the case of undead cells. The imaginal discs in which apoptosis was inhibited by p35 expression, however, varied widely in size, suggesting that apoptosis of loser cells in cell competition ensures uniformity of tissue size [67]. Although the mechanism to induce compensatory proliferation in neighboring winner cells during cell competition remains unclear, these observations indicate that the mechanism is different from the canonical apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation.

Previously, cell proliferation rate (division speed) was considered critical in differentiating winner cells from loser cells [61]. However, recent findings in Drosophila developing retinas and FE indicate that post-mitotic cells also compete. In developing retinas, cell competition plays an important role in sculpting neural networks by selecting optimal neurons and culling unwanted cells [69]. In post-mitotic FE, mutant cells heterozygous for Minute (M/+), a group of dominant mutations defective in producing ribosomal proteins, or homozygous for mahjong (mahj−/−) are out-competed by their wild-type neighbors and undergo competition-dependent apoptosis in the post-mitotic FE [3]. Mahjong is the Drosophila homolog of mammalian DCAF1 (DDB1-and Cul4-associated factor 1), functioning as a substrate receptor subunit of the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4DCAF1 [70] and playing a conserved role in cell competition in Drosophila and cultured mammalian cells [71]. In the post-mitotic FE, since the winner cells stopped cell division, the loss of cells was compensated by hypertrophic growth of some remaining cells [3].

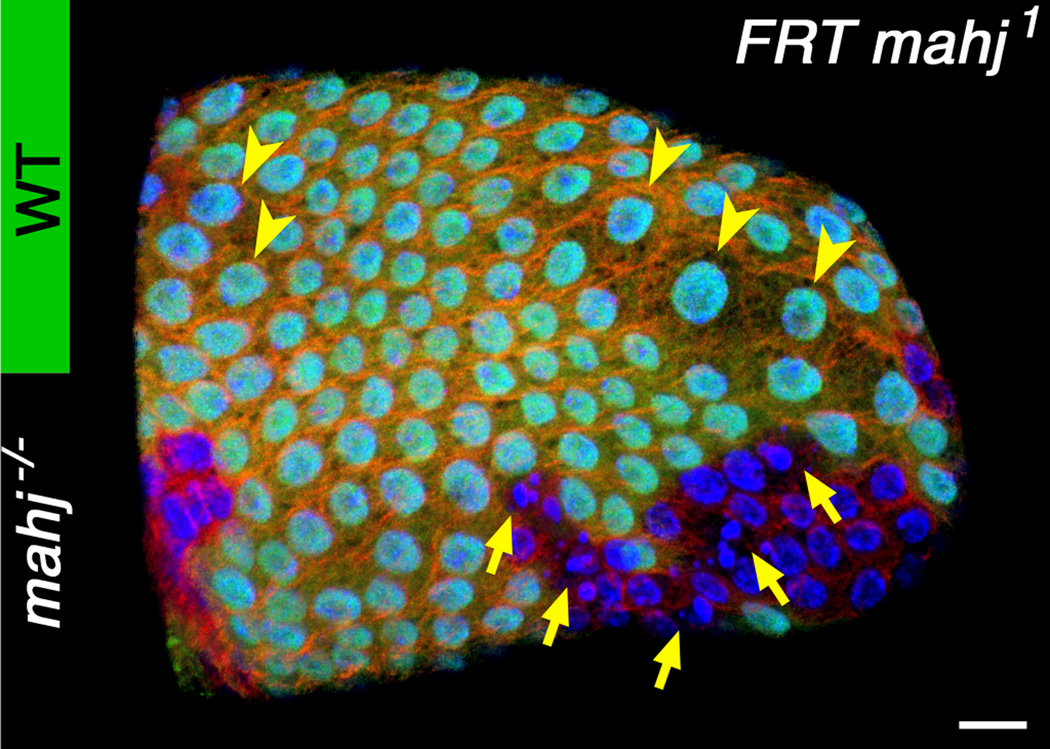

During and after the process of cell competition in the post-mitotic FE, interestingly, some of the remaining normal cells underwent hypertrophic cellular growth to increase cell size, and compensated for the space left by eliminated loser cells (Box 1) [3]. These hypertrophic cells had greater cellular volume, and their nuclear volumes were about two to four times as large as those of the normal cells (Figure 2). The fact that CCH is a result of extra rounds of endoreplication in hypertrophic cells was corroborated by measurement of their genomic DNA content through fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Furthermore, analyses of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation in mahj mosaics revealed that the hypertrophic cells did not prolong the endocycle stage but instead accelerated endoreplication within the normal time window to achieve their increased size. One of the genetic signaling pathways responsible for endocycle acceleration in CCH is the insulin/IGF (insulin-like growth factor)-like signaling (IIS) pathway [3]. The function of the IIS pathway in regulating cellular growth and endoreplication rates has been intensely studied in various cell types and experimental contexts [21–23]. In fact, the cells undergoing CCH showed an increased level of IIS activation, while blockade of IIS activation suppressed CCH.

Figure 2.

Winner cells undergo compensatory cellular hypertrophy (CCH) in post-mitotic cell competition. mahj mosaic follicular epithelium in a post-mitotic stage with loser mahj−/− (GFP negative) and winner wild-type (GFP positive) clones stained for α-tubulin (red) showing competition-dependent apoptosis in mahj−/− clones (arrows) and CCH in some wild-type cells (arrowheads). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm.

CCH in Drosophila adult epidermis

Another recent study in Drosophila adult epidermis showed a similar tissue repair mechanism through cellular hypertrophy during wound healing processes in the quiescent epithelial tissue [4]. After the ventral abdominal epidermis of adult flies was punctured with a sharp needle, epithelial integrity was restored under the melanized scab initially formed in the wound site within 2 days. During the wound healing process, the epithelial sheet gradually reappeared underneath the melanin scab, growing from the periphery toward the center to close the wound. These epithelial cells fused to form a giant syncytium containing many (about 60–120) nuclei that covered the entire region below the scab. At peripheral locations, multiple smaller syncytia containing 2–7 nuclei were observed. At the same time, within 24 hours after wounding, the quiescent epithelial cells located close to the wound re-entered S phase. However, the reactivated cells did not divide, and no increase in epithelial cell number was detected during wound healing. Instead, about 50% of the nuclei located within 100µm of a wound contained 4c or 8c DNA, indicating that they had undergone one or two rounds of the endocycle [4].

Although blocking of the S-phase re-entry by Cyclin E (CycE) knockdown did not change the rate of wound closure, inhibition of syncytium formation by expression of a dominant negative form of the Rac GTPase (RacN17) significantly delayed wound closure. When both polyploidization and cell fusion were blocked simultaneously by knockdown of CycE or E2F in combination with RacN17 in the abdominal epithelium, an even larger delay in wound closure was observed compared to RacN17 expression alone [4]. These studies suggest that polyploidization and cell fusion work redundantly to promote CCH for wound healing in the adult epidermis.

CCH in the mammalian liver

Cellular hypertrophy as a compensatory homeostatic cellular reaction can also be observed in other systems. One of the remarkable examples of cellular hypertrophy responding to cell loss is polyploidization of hepatocytes in mammalian livers [24]. Although most hepatocytes are diploid in young livers, approximately half of adult hepatocytes are polyploid in humans [24, 25]. The liver is the only human internal organ that has an ability to regenerate. Although hepatocytes are normally quiescent, when part of the liver is surgically removed (up to 70% of the liver mass), the remaining tissue regrows to compensate for the lost area [26]. In rat livers, most of the remaining hepatocytes rapidly enter S phase after partial hepatectomy; DNA synthesis initially takes place after hepatectomy, and peaks at 24 hours. Eventually, restoration of the original liver mass occurs in 5–7 days (8–15 days in humans) [26]. The number of polyploid hepatocytes increases significantly after regeneration following a partial resection [24]. Interestingly, previous studies in mice have shown that after partial hepatectomy the liver mass can recover almost to normal size without cell proliferation [27, 28]. Recently a detailed cytological analysis in mouse livers confirmed that cellular hypertrophy through polyploidization made the first contribution to the early phase of liver regeneration; regeneration after 30% partial hepatectomy is achieved solely by cellular hypertrophy without cell division, and hypertrophy precedes proliferation after 70% partial hepatectomy [29]. Furthermore, using liver-specific STAT3-knockout (LS3-KO) mice lacking mitogenic activity in their livers showed that the IIS pathway is involved in cellular hypertrophy of hepatocytes [30]. Although proliferation of hepatocytes following partial hepatectomy was markedly suppressed in LS3-KO mice, the cell size following hepatectomy was significantly larger in LS3-KO mice than in control mice, and the liver mass recovered to almost equal that of control mice. Immediate but transient activation of IIS signaling was observed after hepatectomy in LS3-KO mice significantly more than in control mice. Additionally, adenoviral transfection of dominant negative mutant of Akt, a key regulator of the IIS pathway, led to insufficient liver regeneration following hepatectomy [30]. Furthermore, polyploid hepatocytes accumulate with age in the human liver [24, 31, 32] suggesting that cellular hypertrophy through polyploidization is a conserved homeostatic system to compensate for continual loss of damaged cells.

CCH in the mammalian corneal endothelium

The mammalian corneal endothelium is the monolayer of endothelial cells that forms a boundary between the posterior corneal stroma and the anterior chamber of the eye. The corneal endothelium functions in transporting fluid and solute across the posterior surface of the cornea and is responsible for the maintenance of corneal transparency by regulating stromal hydration [33]. Human corneal endothelial cells are considered to be nonproliferative [33, 34], and a number of morphological studies have shown an age-related decrease in density and increase in the size of these endothelial cells [33–35]. Some studies of in vivo wound healing in mammalian endothelial tissues indicate that wound healing occurs mainly by cell enlargement and migration [33, 36]. For instance, when the cat corneal endothelium was wounded by removing a small number (about 180) of endothelial cells from the internal lining of the cornea, cells surrounding the wound and a few rows behind the wound edge underwent coordinated enlargement, elongated toward the wound, and shifted to cover the wound surface. Then, the enlarged cells adjacent to the wounded area gradually contracted and pulled surrounding cells toward the wounded area [36]. Experimental evidence shows that the enlargement of endothelial cells involves polyploidization. A larger number of polyploid cells, ranging from 4C to 36C, were observed in response to injury in the human corneal endothelium [37]. In addition, the relative number of polyploid cells and cells with multiple nuclei increased with age in healthy human corneal endothelium [33, 37–39]. These studies, therefore, suggest that a tissue homeostatic system similar to CCH functions to maintain the integrity of the corneal endothelium.

Possible Mechanisms for CCH

In Drosophila post-mitotic FE, CCH instead of compensatory proliferation was observed not only when cell competition occurred but also in some wild-type follicle cells when sporadic apoptosis was experimentally induced by overexpression of the pro-apoptotic gene Reaper (Rpr) [3] (Figure 3a,b). The Rpr-overexpressing apoptotic cells were extruded from the apical side of the epithelial layer. JNK activation that is requisite to induce compensatory proliferation in proliferating tissues, however, was not detected in the post-mitotic FE where apoptosis was induced by sporadic overexpression of Rpr. These findings indicate that CCH in the post-mitotic FE does not require JNK activation, unlike the mechanism of compensatory proliferation in proliferating epithelia. In support of this conclusion, in mahj mosaic FE or in FE with Rpr-expressing apoptotic cells, CCH was observed not only in some cells neighboring the mahj−/− or Rpr-expressing apoptotic cells, but also in some cells located several cell diameters away, where JNK activity was low [3].

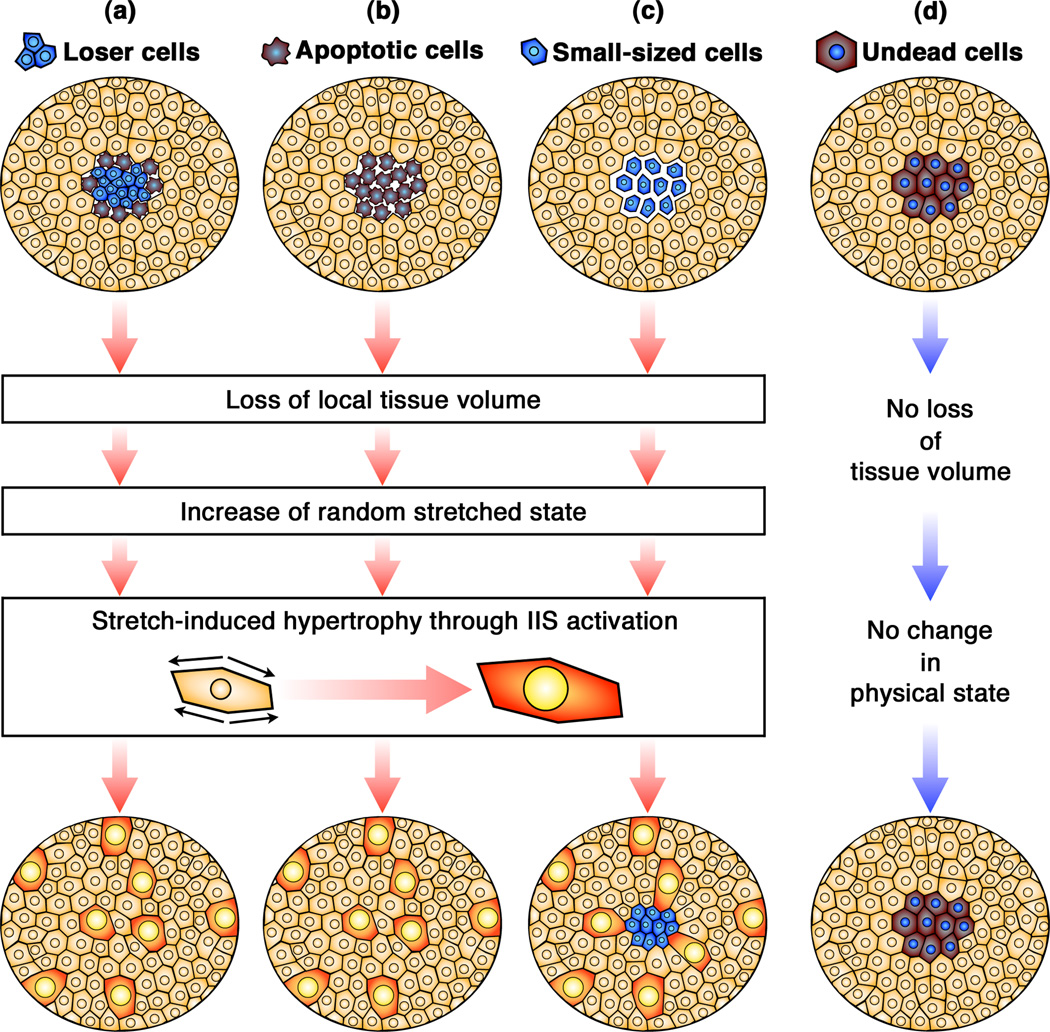

Figure 3.

Model of stretch-induced compensatory cellular hypertrophy (CCH) in post-mitotic epithelia. (a–c) CCH is induced by a loss of local tissue volume resulting from, (a) cell loss caused by cell competition; (b) cell death induced by expression of a pro-apoptotic gene; or (c) smaller cells caused by cellular growth defects. Increase of random stretched state induced by the loss of local tissue volume would trigger sporadic IIS activation in remaining cells. (d) Undead cells with normal cell size, however, do not induce CCH in post-mitotic epithelia, because there is no change in the physical state of the tissue.

The undead-cell-induced tumorigenesis in proliferating tissues demonstrates the mechanism by which mitogenic signaling molecules from apoptotic dying cells induce compensatory proliferation in neighboring cells [10, 11, 18]. In post-mitotic FE, the significance of IIS upregulation is revealed for hypertrophic growth of some cells [3]. Comparing the situations in which CCH is induced highlights the single common event entailing CCH is a loss of local tissue volume. These situations include: (1) when there is cell loss either through cell competition (mahj mosaic and M/+ mosaic FE) (Figure 3a) or expression of a cell-death inducing gene (Rpr) in the post-mitotic FE (Figure 3b); (2) suppression of apoptosis in mahj−/− cells which resulted in smaller cells (Figure 3c); (3) induced knockdown of dMyc in post-mitotic follicle cells which also resulted in non-apoptotic smaller cells (Figure 3c). In contrast, when cell death is blocked in Rpr-overexpressing or M/+ cells where the undead cells have normal cell sizes, CCH is not induced (Figure 3d). These observations indicate that CCH is sporadically induced by loss of local tissue volume resulting from cellular growth or viability defects of some cells in the post-mitotic epithelium [3].

A key question in understanding the mechanism of CCH in the post-mitotic FE is how the loss of local tissue volume leads to sporadic upregulation of IIS signaling. The IIS-activation-associated CCH can be located several cells away from the dead or small cells; no apparent rule on which cells will undergo hypertrophic growth has been determined. A diffusing or membrane-bound signal from the dead or small cells is probably not a likely candidate, since the signal would either form a gradient from the signaling source or trigger changes in their immediate neighbors. One plausible model involves a global physical alteration resulting from the loss of local tissue volume to induce random CCH in post-mitotic tissues (Figure 3). For example, a reduction in number or size of some cells would increase the overall stretched state of the post-mitotic tissue, and the increase of the tensile force is probably not evenly distributed among all cells. This change of tension within the epithelium or the geometry of cells can be rather “random” and spread a few cells away, without necessarily having a greater effect on their immediate neighbors. Interestingly, cyclic mechanic stretch has been shown to enhance the hypertrophic growth of mammalian cardiomyocytes or chick skeletal muscle cells [40–42], and several previous reports revealed that the IIS pathway is also involved in mechanical stretch-induced hypertrophy [42, 43].

In Drosophila post-mitotic FE, blockade of the IIS pathway suppressed CCH [3]. When CCH was inhibited, remaining cells were physically stretched and flattened. When the physical stress was beyond a limit, the epithelial structures broke probably because of the disruption of their cell-cell adhesion. This epithelial disruption eventually caused the egg chamber to die. Similarly, when mass apoptosis was induced in a large area of the post-mitotic FE, although the remaining normal cells became stretched, flattened, and underwent CCH, they could not enlarge fast enough to cover the entire lost area. These hypertrophic cells failed to maintain the epithelial cellular structure, and eventually the epithelium was broken. Similar breakdown of epithelial integrity can be seen in the polyploid subperineurial glia (SPG) covering the developing Drosophila larval brain; inhibition of SPG polyploidy has been shown to lead to rupture of the septate junctions of the tissue necessary for the blood–brain barrier [44]. Therefore, physical stretching might be a passive early response when a post-mitotic tissue is challenged by a loss of local tissue volume, which in turn activates growth-promoting signaling such as IIS to promote cellular hypertrophy and to maintain tissue integrity.

However, the mechanism of wound-induced CCH in the Drosophila adult epidermis appears to be different from that in the post-mitotic FE. In epidermal tissue, activation of the Hippo pathway transducer Yki was observed in cells located near the wound. When the Yki activity was blocked either by overexpression of Hippo or knockdown of Yki in these cells, their polyploidization was strongly suppressed [4]. These results indicate that Yki mediates Hippo signaling, and its function is important for cell cycle re-entry and polyploidization through CycE upregulation in response to wounding. At the same time, JNK activation was also observed in these cells. JNK is activated at the wound site and is required for wound healing in both flies and mammals [45, 46]. In the Drosophila imaginal discs, it has been shown that JNK-dependent Yki activation is required not only for regeneration-associated tissue growth after induction of apoptosis [17], but also for some types of tumorigenesis [47, 48]. Furthermore, a recent study revealed a conserved mechanism by which JNK upregulates Yki activity by promoting the binding of Ajuba family proteins to Warts and LATS [49]. Therefore, wound-induced JNK activation might promote S phase re-entry of the quiescent epithelial cells induced by Yki activation.

Thus, the genetic pathways inducing polyploidization in CCH are different between the adult epidermis (Hippo) and follicular epithelium (IIS). This difference is probably due to tissue-intrinsic genetic constraints. For instance, in the Drosophila follicular epithelium, Notch pathway is activated by its ligand Delta expressed in the germline cells at stage 7, which induces differentiation and a switch from the mitotic cycle to the endocycle [50–53]. Later, at stage 10b, Notch is inactivated in the follicle cells overlying the oocyte, which, in conjunction with ecdysone signaling, results in a second cell cycle transition from endocycle to gene amplification in specific genomic loci [20, 54]. Because this Notch activation at stage 7 is a signal to commit cell fate, an override against the signal is not easy for the cells. The endocycles of Drosophila are driven by a molecular oscillator in which the E2F1 transcription factor promotes CycE expression and S-phase initiation, S phase then activates the CRL4CDT2 ubiquitin ligase, and this in turn mediates the destruction of E2F1 [23]. It has been shown that the activation level of IIS pathway impacts E2F1 translation, thereby regulating the endocycle progression rate [23]. Contrary to this, the Hippo pathway cannot promote polyploidization and cellular growth in the post-mitotic FE [3]. In fact, Yki activation induced by disruption of the Hippo pathway in the FE induces mis-regulation of Notch signaling and results in aberrant differentiation and uncontrolled proliferation of the epithelial cells [55, 56]. Therefore, the more accessible genetic pathways might be co-opted in different tissues dependent on the present tissue-intrinsic genetic constraint. In this point of view, it is intriguing that the mammalian liver can do both compensatory proliferation and CCH in response to the loss of tissue volume, probably because these liver cells are in a state that can enter either the mitotic cycle or the endoreplication cycle.

Despite the differences in genetic mechanisms directly involved in the endocycle, the upstream event triggering upregulation of these genetic pathways seems homologous. At the beginning of the wound healing process, cells at the wound margin elongate and orient toward the wound, which is observed in Drosophila epidermis [4, 57] and mammalian corneal endothelium [36]. When apoptosis was induced in a group of cells in the Drosophila post-mitotic FE, these apoptotic cells were apically extruded from the epithelial layer [3]. This apical extrusion, pulling the neighboring cells, makes them elongate toward the apoptotic cells. The syncytium formation observed in Drosophila epidermis has not been described in the cell competition induced in Drosophila post-mitotic FE, probably because the magnitude of cell loss is milder than the wounding. In fact, a larger wound induces a giant syncytium containing many more nuclei [4, 57]. Therefore, these morphological changes of the cells at the periphery of the site where tissue volume is lost are commonly induced as an early response to tissue damage amongst different types of tissue. The important mechanism by which the physical changes of the cells induce genetic pathway alteration involved in cellular hypertrophy will be revealed in future studies.

Concluding Remarks

Metazoans have the remarkable ability to reproduce morphological patterns in diverse organs, with the organ size finely controlled. Several studies in Drosophila imaginal discs suggest that the mechanisms underlying tissue size control do not function by counting cell numbers, but by “measuring” physical distance of cells or tissue volume [58–60]. Imaginal disc cells with cell division inhibited converted the mitotic cycle into an endoreduplication cycle and did not perturb overall growth and patterning of the tissue [59, 60]. Also, in the case of CCH in the Drosophila post-mitotic FE, cells appear to measure tissue dimensions based on physical parameters. In both cases, plastic cellular behaviors ensure the fine control of tissue integrity and organ size not only by balancing cell death and cell division, but also by a surveillance mechanism involving reciprocal interactions between the cell and tissue volumes. The description of CCH as the other evolutionarily conserved cellular mechanism for compensation opens a door to investigate organ-specific tissue homeostasis, and age-related diseases resulting from deterioration of this homeostasis system.

Highlights.

Compensatory cellular hypertrophy (CCH) as a conserved tissue repair system.

CCH during cell competition in post-mitotic tissues.

CCH during wound healing in post-mitotic tissues.

Loss of local tissue volume triggers CCH in post-mitotic tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Kennedy for critical reading of the manuscript. W.-M. D. is supported by National Science Foundation grant (IOS-1052333) and National Institutes of Health grant (R01 GM072562).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pellettieri J, Alvarado AS. Cell turnover and adult tissue homeostasis: from humans to planarians. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2007;41:83–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan Y, Bergmann A. Apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation. The Cell is dead. Long live the Cell! Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamori Y, Deng W-M. Tissue repair through cell competition and compensatory cellular hypertrophy in postmitotic epithelia. Dev. Cell. 2013;25:350–363. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Losick VP, et al. Polyploidization and cell fusion contribute to wound healing in the adult Drosophila epithelium. Curr. Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.029. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morata G, et al. Mitogenic signaling from apoptotic cells in Drosophila. Dev. Growth Differ. 2011;53:168–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2010.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haynie JL, Bryant PJ. The effects of X-rays on the proliferation dynamics of cells in the imaginal disc of Drosophila melanagaster. Rouxs Arch. Dev. Biol. 1977;183:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00848779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James AA, Bryant PJ. A quantitative study of cell death and mitotic inhibition in g-irradiated imaginal wing discs of Drosophila melanogaster. Radiat. Res. 1981;87:552–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milan M, et al. Developmental parameters of cell death in the wing disc of Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5691–5696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huh JR, et al. Compensatory proliferation induced by cell death in the Drosophila wing disc requires activity of the apical cell death caspase Dronc in a nonapoptotic role. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1262–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pérez-Garijo A, et al. Caspase inhibition during apoptosis causes abnormal signalling and developmental aberrations in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:5591–5598. doi: 10.1242/dev.01432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryoo HD, et al. Apoptotic cells can induce compensatory cell proliferation through the JNK and the Wingless signaling pathways. Dev. Cell. 2004;7:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee TV, et al. Drosophila IAP1-mediated ubiquitylation controls activation of the initiator caspase DRONC independent of protein degradation. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kondo S, et al. DRONC coordinates cell death and compensatory proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:7258–7268. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00183-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith-Bolton R, et al. Regenerative growth in Drosophila imaginal discs is regulated by Wingless and Myc. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu M, et al. Interaction between RasV12 and scribbled clones induces tumour growth and invasion. Nature. 2010;463:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature08702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grusche FA, et al. The Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway controls regenerative tissue growth in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Biol. 2011;350:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun G, Irvine KD. Regulation of Hippo signaling by Jun kinase signaling during compensatory cell proliferation and regeneration, and in neoplastic tumors. Dev. Biol. 2011;350:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pérez-Garijo A, et al. The role of Dpp and Wg in compensatory proliferation and in the formation of hyperplastic overgrowths caused by apoptotic cells in the Drosophila wing disc. Development. 2009;136:1169–1177. doi: 10.1242/dev.034017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan Y, Bergmann A. Distinct mechanisms of apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation in proliferating and differentiating tissues in the Drosophila eye. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calvi B, et al. Cell cycle control of chorion gene amplification. Genes. Dev. 1998;12:734–744. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavaliere V, et al. dAkt kinase controls follicle cell size during Drosophila oogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 2005;232:845–854. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hietakangas V, Cohen SM. Regulation of tissue growth through nutrient sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:389–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zielke N, et al. Control of Drosophila endocycles by E2F and CRL4(CDT2) Nature. 2011;480:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature10579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duncan AW. Aneuploidy, polyploidy and ploidy reversal in the liver. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013;24:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan AW, et al. Frequent aneuploidy among normal human hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:25–28. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michalopoulos GK. Liver regeneration. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;213:286–300. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minamishima YA, et al. Recoveryof liver mass without proliferation of hepatocytes after partial hepatectomy in Skp2-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:995–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satyanarayana A, et al. Telomere shortening impairs organ regeneration by inhibiting cell cycle re-entry of a subpopulation of cells. EMBO J. 2003;22:4003–4013. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyaoka Y, et al. Hypertrophy and unconventional cell division of hepatocytes underlie liver regeneration. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:1166–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haga S, et al. Compensatory recovery of liver mass by Akt-mediated hepatocellular hypertrophy in liver-specific STAT3-deficient mice. J. Hepatol. 2005;43:799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmucker DL. Hepatocyte fine structure during maturation and senescence. J. Electron Microsc. Tech. 1990;14:106–125. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060140205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kudryavtsev BN, et al. Human hepatocyte polyploidization kinetics in the course of life cycle. Virchows Arch. B Cell Pathol. Incl. Mol. Pathol. 1993;64:387–393. doi: 10.1007/BF02915139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joyce NC. Proliferative capacity of the corneal endothelium. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2003;22:359–389. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mimura T, et al. Corneal endothelial regeneration and tissue engineering. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2013;35:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roszkowska AM. Age-related modifications of the corneal endothelium in adults. Int. Ophthalmol. 2004;25:163–166. doi: 10.1007/s10792-004-1957-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Honda H, et al. Cell movements in a living mammalian tissue: long-term observation of individual cells in wounded corneal endothelia of cats. J. Morphol. 1982;174:25–39. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051740104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikebe H, Takamatsu T, Itoi M, Fujita S. Changes in nuclear DNA content and cell size of injured human corneal endothelium. Exp. Eye Res. 1988;47:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(88)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikebe H, Takamatsu T, Itoi M, Fujita S. Cytofluorometric nuclear DNA determinations on human corneal endothelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 1984;39:497–504. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(84)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikebe H, Takamatsu T, Itoi M, Fujita S. Age-dependent changes in nuclear DNA content and cell size of presumably normal human corneal endothelium. Exp. Eye Res. 1986;43:251–258. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(86)80093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaauw E, et al. Stretch-induced hypertrophy of isolated adult rabbit cardiomyocytes. AmJPhysiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010;299:H780–H787. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00822.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leychenko A, et al. Stretch-induced hypertrophy activates NFkB-mediated VEGF secretion in adult cardiomyocytes. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e29055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasai N, et al. Involvement of PI3K/Akt/TOR pathway in stretch-induced hypertrophy of myotubes. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:100–106. doi: 10.1002/mus.21473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu BS, et al. An analysis of the effects of stretch on IGF-I secretion from rat ventricular fibroblasts. AmJPhysiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;293:H677–H683. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01413.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unhavaithaya Y, Orr-Weaver TL. Polyploidization of glia in neural development links tissue growth to blood-brain barrier integrity. Genes. Dev. 2012;26:31–36. doi: 10.1101/gad.177436.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Angel P, et al. Function and regulation of AP-1 subunits in skin physiology and pathology. Oncogene. 2001;20:2413–2423. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Razzell W, et al. Swatting flies: modelling wound healing and inflammation in Drosophila. Dis. Model Mech. 2011;4:569–574. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohsawa S, et al. Mitochondrial defect drives non-autonomous tumour progression through Hippo signalling in Drosophila. Nature. 2012;490:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature11452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Enomoto M, Igaki T. Src controls tumorigenesis via JNK-dependent regulation of the Hippo pathway in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:65–72. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun G, Irvine KD. Ajuba family proteins link JNK to Hippo signaling. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:ra81. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruohola H, et al. Role of neurogenic genes in establishment of follicle cell fate and oocyte polarity during oogenesis in Drosophila. Cell. 1991;66:433–449. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deng W-M, et al. Notch-Delta signaling induces a transition from mitotic cell cycle to endocycle in Drosophila follicle cells. Development. 2001;128:4737–4746. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.23.4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.López-Schier H, St Johnston D. Delta signaling from the germ line controls the proliferation and differentiation of the somatic follicle cells during Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1393–1405. doi: 10.1101/gad.200901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun J, Deng W-M. Hindsight mediates the role of notch in suppressing hedgehog signaling and cell proliferation. Dev. Cell. 2007;12:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun J, Deng W-M. Regulation of the endocycle/gene amplification switch by Notch and ecdysone signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2008;182:885–896. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polesello C, Tapon N. Salvador-Warts-Hippo signaling promotes Drosophila posterior follicle cell maturation downstream of Notch. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1864–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu J, et al. The Hippo pathway promotes Notch signaling in regulation of cell differentiation, proliferation, and oocyte polarity. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Galko MJ, Mark AK. Cellular and genetic analysis of wound healing in Drosophila larvae. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lecuit T, Le Goff L. Orchestrating size and shape during morphogenesis. Nature. 2007;450:189–192. doi: 10.1038/nature06304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weigmann K, et al. Cell cycle progression, growth and patterning in imaginal discs despite inhibition of cell division after inactivation of Drosophila Cdc2 kinase. Development. 1997;124:3555–3563. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neufeld TP, et al. Coordination of growth and cell division in the Drosophila wing. Cell. 1998;93:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tamori Y, Deng W-M. Cell competition and its implications for development and cancer. J. Genet. Genomics. 2011;38:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnston LA. Competitive interactions between cells: death, growth, and geography. Science. 2009;324:1679–1682. doi: 10.1126/science.1163862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baker NE. Cell competition. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:R11–R15. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Beco S, et al. New frontiers in cell competition. Dev. Dyn. 2012;241:831–841. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levayer R, Moreno E. Mechanisms of cell competition: Themes and variations. J. Cell Biol. 2013;200:689–698. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simpson P, Morata G. Differential mitotic rates and patterns of growth in compartments in the Drosophila wing. Dev. Biol. 1981;85:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de la Cova C, et al. Drosophila myc regulates organ size by inducing cell competition. Cell. 2004;117:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moreno E, et al. Cells compete for decapentaplegic survival factor to prevent apoptosis in Drosophila wing development. Nature. 2002;416:755–759. doi: 10.1038/416755a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Merino MM, et al. “Fitness Fingerprints” mediate physiological culling of unwanted neurons in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:1300–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li W, et al. Merlin/NF2 suppresses tumorigenesis by inhibiting the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4(DCAF1) in the nucleus. Cell. 2010;140:477–490. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tamori Y, et al. Involvement of Lgl and Mahjong/VprBP in cell competition. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]