Short abstract

The remodeling of the cervix from a rigid barrier into a compliant structure, which dilates to allow for delivery, is a critical process for a successful pregnancy. Changes in the mechanical properties of cervical tissue during remodeling are hypothesized to be related to the types of collagen crosslinks within the tissue. To further understand normal and abnormal cervical remodeling, we quantify the material properties and collagen crosslink density of cervical tissue throughout pregnancy from normal wild-type and Anthrax Toxin Receptor 2 knockout (Antxr2-/-) mice. Antxr2-/- females are known to have a parturition defect, in part, due to an excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins in the cervix, particularly collagen. In this study, we determined the mechanical properties in gestation-timed cervical samples by osmotic loading and measured the density of mature collagen crosslink, pyridinoline (PYD), by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MSMS). The equilibrium material response of the tissue to loading was investigated using a hyperelastic material model where the stresses in the material are balanced by the osmotic swelling tendencies of the glycosaminoglycans and the tensile restoring forces of a randomly-oriented crosslinked collagen fiber network. This study shows that the swelling response of the cervical tissue increased with decreasing PYD density in normal remodeling. In the Antxr2-/- mice, there was no significant increase in swelling volume or significant decrease in crosslink density with advancing gestation. By comparing the ECM-mechanical response relationships in normal and disrupted parturition mouse models this study shows that a reduction of collagen crosslink density is related to cervical softening and contributes to the cervical remodeling process.

1. Introduction

The ability of the cervix to remodel from a mechanical barrier into a compliant structure is critical for a successful term delivery. For the majority of the pregnancy, the cervix must act as a closed barrier, resisting forces exerted from the growing fetus inside the uterus. At the end of the pregnancy, the cervix must transform into a compliant structure, which dilates to allow for delivery of a fetus. It is hypothesized that the mechanical integrity of the cervix is dependent on the extracellular matrix (ECM), particularly on the degree and types of collagen crosslinks within the tissue.

Abnormal cervical remodeling is a significant clinical dilemma in obstetrics. Premature cervical remodeling, commonly referred to as cervical insufficiency, increases a woman's risk for preterm birth [1]. On the other end of the spectrum, approximately 7% of all pregnancies continue past their due date (post-term). Some of these cases are due to delayed or inadequate cervical ripening [2,3]. Post-term pregnancies are associated with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality, along with significant risks to the mother, including a doubling in the Caesarean delivery rate [3]. Lastly, some pregnancies are complicated by the arrest of cervical dilation during the normal labor process, which results in the need for delivery by Caesarean section. Therefore, in an effort to prevent complications that result from abnormal cervical remodeling, the relationship between the cervical mechanical properties and ECM composition throughout pregnancy needs to be further elucidated.

Studies evaluating the cervical remodeling process in humans are lacking due to the challenge of obtaining sufficient tissue samples throughout pregnancy. Mouse models overcome this limitation and studies have shown that many of the molecular mechanisms of cervical remodeling are conserved between humans and mice [4]. Several studies have been conducted on rodent cervical tissue to determine the tissue's mechanical properties throughout gestation [5,6]. In addition, studies have investigated how collagen properties affect tissue mechanical properties [7,8], how proteoglycans affect tissue extensibility and creep rates [9], and how collagenase activity affects tissue mechanical properties [10]. These studies suggest that the alterations of various ECM components affect cervical softening. In this study, we utilize mouse models of normal and disrupted parturition to determine the functional relationship between cervical material properties and collagen crosslinking density during gestation.

1.1. ECM Changes During Cervical Remodeling.

In collagenous tissues, the collagen structure provides the tissue with its tensile properties. In the cervix, the majority of the collagens in the ECM are fiber-forming types I and III, which make up 60–80% of the dry weight in human tissue [11,12], and about 10–20% of the dry weight in mouse [13]. In connective tissue, type I collagen is stabilized by intermolecular crosslinks including immature divalent and mature trivalent crosslinks. The formation of crosslinks is regulated by lysyl hydroxylase and lysyl oxidase activity (LOX) [14]. Recently, LOX mediated crosslinking has been shown to significantly affect the functional properties of embryonic tendon [15]. In the cervix, the expression and activity of lysyl hydroxylase and LOX has been shown to decrease in early pregnancy, followed by a subsequent decrease in the trivalent crosslinks pyridinoline (PYD) during the second half of gestation, while the total collagen content has been shown to stay constant [16]. These data suggest that there is a high degree of collagen crosslink turnover during pregnancy as mature crosslinks are broken down and replaced by immature poorly crosslinked collagen [4].

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are negatively charged polysaccharides in the ECM that provide the tissue with a net fixed charge density (FCD). The FCD imbibes fluids into the tissue to induce swelling, providing the tissue with its compressive strength. There are both sulfated and nonsulfated GAGs in the ECM. Hyaluronan (HA) is the sole non sulfated GAG. The sulfated GAGs mostly exist as chains attached to a protein core as proteoglycans (PGs) and include chondroitin sulfate (CS), dermatan sulfate (DS), and heparan sulfate (HS). In the cervix, there are small leucine-rich PGs (e.g., decorin, biglycan, fibromodulin, osteomodulin, and aspirin) and larger PGs versicans [16,17].

Recent studies on rodent cervical tissue by Mahendroo et al. have shown that cervical remodeling is facilitated by shifts in the ECM constituents in four overlapping stages during pregnancy and delivery. First, the cervix gradually softens with measurable differences detectable around gestation day 12 of a 19-day mouse gestation period. This softening stage is associated with a decline in collagen crosslink density (from 12% in the nonpregnant state to 9% at gestation day 12) and an increase in water content, with no significant changes in the GAG content [16]. Second, the cervix ripens before delivery around gestation day 18, characterized by a rapid decrease in collagen crosslink density (from 9% at gestation day 12 to 5% at gestation day 18), a rapid increase in water content [13], and a doubling in the HA content [17]. Third, at delivery on gestation day 19, the collagen structure become further dispersed as the cervix dilates for delivery. Fourth, post-delivery, the cervix reverses the remodeling process in a repair stage and returns to its original nonpregnant state in as early as 24 h in the mouse. These changes in the ECM have been shown to correlate to a mechanically softer cervix at term [18].

1.2. Disrupted Parturition Mouse Model.

The anthrax toxin receptor (ANTXR) proteins, ANTXR1 and ANTXR2, are most commonly known for their ability to bind to anthrax toxin. These transmembrane receptors are known to bind and interact with extracellular matrix proteins [19–24]. Young Antxr2 knockout (Antxr2-/-) mice are fertile and are able to carry pregnancies to term. However, they exhibit a parturition defect in which they are unable to deliver the pups, resulting in maternal death or fetal reabsorption. The histological analysis of cervical tissue from Antxr2-/- mice demonstrate an excessive accumulation of ECM proteins, particularly collagen [20,21]. This excess of collagen results in fibrosis and the inability of the cervix to dilate during labor, which may, in part, contribute to the parturition defect seen in the Antxr2-/- mice. In order to further understand the pathophysiology of abnormal cervical remodeling, we utilized the Antxr2-/- mouse model to evaluate the correlation between collagen crosslinks and the mechanical properties of cervical tissue from these mice compared to wild-type (Antxr2+/+) mice.

1.3. Purpose and Objectives of Study.

Quantitative measures for the material properties of cervical tissue throughout pregnancy have not yet been established. The current clinical diagnosis of cervical remodeling progression is based on qualitative measures, such as digital examination of the cervix [25]. Quantitative measures for cervical material properties are hypothesized to be important, since purely structural measures, such as cervical length [26,27], have been shown to be inconclusive measures for predicting preterm birth in certain cases. Obtaining quantitative measures for cervical material properties are complicated by its complex material behavior, including anisotropy, time-dependency, and tension-compression nonlinearity [18,28]. Thus, the understanding of how the ECM changes correlate to material properties remains limited.

The objectives of this study are to quantify the changes in the mechanical properties and collagen crosslink density of cervical tissue from wild-type (Antxr2+/+) and Antxr2-/- mice and to evaluate how the relationship between the collagen crosslink density and mechanical properties of cervical tissue evolve throughout gestation. To this end we: (1) measure the equilibrium material response of cervical tissue to osmotic loading, (2) utilize a microstructurally inspired material model to describe the mechanical behavior of the tissue, (3) quantify the collagen crosslink density of the sample, and (4) correlate the swelling response of the tissue to collagen crosslink density.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sample Preparation.

All studies were conducted in accordance with Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The estrous cycle of nonpregnant (NP) nulliparous 2–6 month old Antxr2+/+ and Antxr2-/- females were monitored [29]. The NP females were sacrificed at the diestrus stage of the cycle for consistency and age-matched Antxr2+/+ and -/- females were sacrificed on gestation day 12.5 and 18.5 of the 19-day gestation period. Pregnant mice carried anywhere from 2 to 8 pups. It is unknown whether there are differences in the cervical tissue properties with the number of pups. In other biomechanical studies on mouse cervical tissue, the number of pups is not reported but the data are consistent within gestation day groups [5,30]. Immediately after sacrifice, the cervix was isolated at the junction from the uterine horns and the vaginal tissue was removed. Samples were kept frozen at − until test day. A total of five sample groups were investigated in this study: (1) Antxr2+/+NP, (2) Antxr2+/+ gestation day 12.5 (Antxr2+/+D12), (3) Antxr2+/+ gestation day 18.5 (Antxr2+/+D18), (4) Antxr2-/-NP, and (5) Antxr2-/- gestation day 18 (Antxr2-/-D18).

2.2. Osmotic Loading.

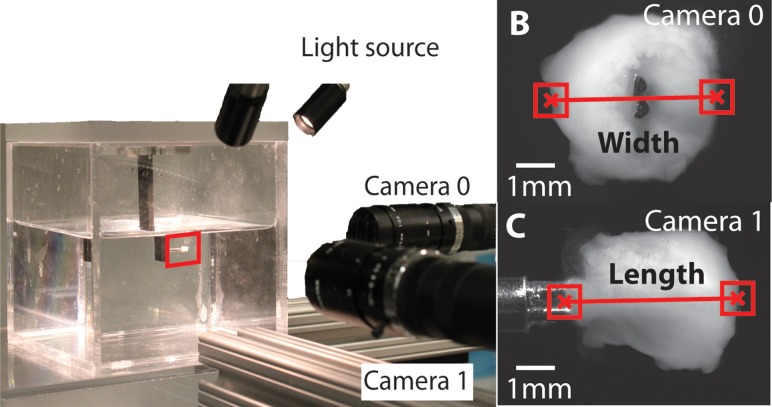

Osmotic loading tests were conducted on whole and intact cervix samples based on previous methods conducted on cartilage [31–33], intervertebral disks [34], and brain tissue [35]. Frozen cervices were thawed, suspended through the inner canal, and immersed in a custom built swelling chamber (see Fig. 1(a)) filled with 4000 mOsm sodium chloride (NaCl) with 2 mM ethylenediamineteraacetic acid (EDTA) protease inhibitor. It has previously been shown that the biomechanical properties of the cervical tissue are the same between fresh tissue and previously frozen tissue [30,36]. All tests were conducted at room temperature. Two CCD cameras (Point Gray Grasshopper, GRAS-50S5M-C 75 mm, f/4 lens) arranged perpendicular to each other, simultaneously acquired images of the cervix during osmotic loading (see Fig. 1(b)). These images were used to estimate the volume by idealizing the cervical geometry as a cylinder.

Fig. 1.

(a) Experimental setup for osmotic loading tests with the camera setup. Camera images of (b) the internal os (the uterine side of the cervix), and (c) along the length of the cervix sample with the dimensions taken using the VIC-2D.

The reference geometry was determined at equilibrium (10–12 h) in the 4000 mOsm NaCl solution. This ensured that the samples were able to completely thaw and rehydrate before testing. Samples were then subjected to a sequence of bath concentrations of = 2000, 1000, and 300 mOsm NaCl (all with 2 mM EDTA) for 4 h each while the cameras acquired images every 10 min. At the end of this loading regimen, samples were again placed in 4000 mOsm NaCl with 2 mM EDTA to determine if they returned to their reference configuration, indicating they did not sustain damage during testing. If there was no evidence of tissue damage, the samples were weighed to quantify the reference wet weight.

Changes in the specimen dimensions at each were determined using digital image correlation (DIC) (VIC-2D, Correlated Solutions, Columbia, SC) by tracking the edge displacements of the cervical length and width (see Figs. 1(b) and 1(c)). These displacements were confirmed with a custom matlab code to verify that correlation reflected the overall dimensional changes of the tissue. The final equilibrium volume at each was normalized by the reference volume to calculate the relative swelling volume .

2.3. Constitutive Model for Cervical Tissue.

In an attempt to explain the swelling behavior of the tissue based on the ECM components, the equilibrium response of the material is modeled as a hyperelastic material where the stresses in the material are balanced by the osmotic swelling tendencies of the negatively-charged GAGs and the tensile restoring forces of a randomly oriented collagen fiber network [37]. Here we model the collagen network using a continuous fiber distribution model [37,38] and we account for the electrostatic charge of the GAG content using the Donnan equilibrium theory [39].

The Cauchy stress in the mixture is given by

| (1) |

where is the interstitial fluid pressure, is the identity matrix, is the Cauchy stress in the solid collagen network, is the deformation gradient of the solid, , and is the Helmholtz free energy density of the collagen network. The fluid pressure term arises from the assumption that the solid and fluid constituents are intrinsically incompressible. The pressure is described by the Donnan equilibrium theory [39]

| (2) |

where is the universal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, is the fixed charge density (FCD) arising from the charged GAGs fixed to the solid collagen network (charges per volume of interstitial fluid (mEq/L)), and is the salt concentration in the external environment. The FCD is evaluated from

| (3) |

| (4) |

where is the FCD in the reference frame, evaluated at 4000 mOsm NaCl. Here, and are the charge numbers and and are the concentrations of the GAGs (mol/L) in the reference frame, which are based on the GAG content values published by Akgul et al. [17]. Here, we assume that the GAG content values are the same for both the Antxr2+/+ and Antxr2-/- animals. Here, is the FCD in the current frame and is tissue hydration.

The resulting osmotic swelling tendency is counterbalanced by the tensile forces of the collagen fiber network. In this model, the stress-strain behavior of an individual fiber is phenomenologically prescribed and the total stress in the collagen solid network is derived from summing the individual fiber stresses using a spherical fiber distribution [37,38,40]. The strain energy of the collagen network is then given by

| (5) |

where is the deformation gradient of the collagen network, is the square of the fiber stretch, is the right Cauchy–Green tensor, and is the unit step function and enforces that the fiber network only sustains tension. Here, is the initial direction of a collagen fiber, with in a Cartesian basis , where and are spherical coordinates. Here, is the free energy density of a single fiber bundle (i.e., the collection of crosslinked collagen fibrils) and is constitutively prescribed to be

| (6) |

where is the elastic modulus of the collagen fiber given in kPa and is a unitless stiffening parameter. For the simplicity of this initial model, is prescribed to be 3 [37] and the fibers are thought to be randomly oriented in the reference configuration, hence, and are the same for all .

2.4. Collagen Crosslink Density.

After osmotic loading, the samples were equilibrated in 0.15 M NaCl, lyophilized and weighed to determine dry weights. Dehydrated samples were reduced in sodium borohydride (), then hydrolyzed in 12 M hydrochloric acid in vacuo at for 18–24 h. The hydrolysate was lyophilized and resuspended in a heptaflurobutyric acid (HFBA) buffer. These samples were subjected to liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MSMS) to determine the contents of the trivalent mature crosslinks pyridinoline (PYD) and deoxypyridinoline (DPYD) and hydroxyproline (HYP) using a method adapted from Refs. [41–44]. The method, which consists of two sequential LC-MSMS assays, is able to measure the PYD, DPYD, and HYP along with the divalent crosslink dihydroxylysionorleucine (DHLNL) and pentosidine in a single sample (DHLNL and pentosidine measurements are not reported here). The sample pretreatment without a reduction step precluded the measurement of the divalent crosslink DHLNL. The LC-MSMS methodology is described in detail in the Appendix. The total collagen content was determined by assuming 14% HYP content per collagen by weight [45]. The collagen crosslink density of the tissue was calculated by dividing the concentration of the PYD by the concentration of collagen. This calculation indicates the fraction of total collagen that is crosslinked in the tissue.

2.5. Finite Element Analysis.

The stress response of the cervical tissue samples during osmotic swelling was analyzed using a representative volume element of the material implemented in FEBio v1.5.2.1 The material parameters , , , and were inputted into the model based on the environmental conditions, measured tissue content, and values from the literature (see Table 1). Tissue hydration was experimentally determined and the FCD were based on the GAG measurements listed in Table 2 from Ref. [17], assuming a valence of for HA and Eq/mol for CS and DS. Swelling was simulated by changing the bath concentration from mOsm to mOsm and the relative equilibrium volume at each concentration was calculated based on the reference at mOsm. The model was fit to the averaged equilibrium swelling data by adjusting the value of the collagen elastic modulus such that the differences between the model predictions and data were minimized. The coefficient of determination () was calculated for each fit and the values of that maximized the value were determined to be the best fit values.

Table 1.

Input parameter values for the FEA with gestation day. Values were assumed to be conserved between wild-type and knockout cervices.

| NP | D12 | D18 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| (mEq/L) | −8 | −8 | −10 |

| mOsm | (4000,2000,1000,300) | ||

| 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.8 | |

Table 2.

Table of sulphated and nonsulphated glycosaminoglycans with gestation day from Akgul et al. [17], showing a range of one standard deviation

| NP | D12 | D18 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS/DS /mg dry | 7.0 ± 0.5 | 10.0 ± 1.5 | 10.0 ± 1.5 |

| HA /mg dry | 7.4 ± 2.0 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 24.6 ± 6.0 |

| (mmol/L) | 2.46 ± 0.18 | 3.16 ± 0.47 | 2.35 ± 0.35 |

| (mmol/L) | 2.60 ± 0.70 | 1.58 ± 0.32 | 5.77 ± 1.41 |

2.6. Statistical Analysis.

The equilibrium relative swelling volumes, values, and collagen crosslink density values were compared between groups using a two-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was determined at a -value of less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Osmotic Loading.

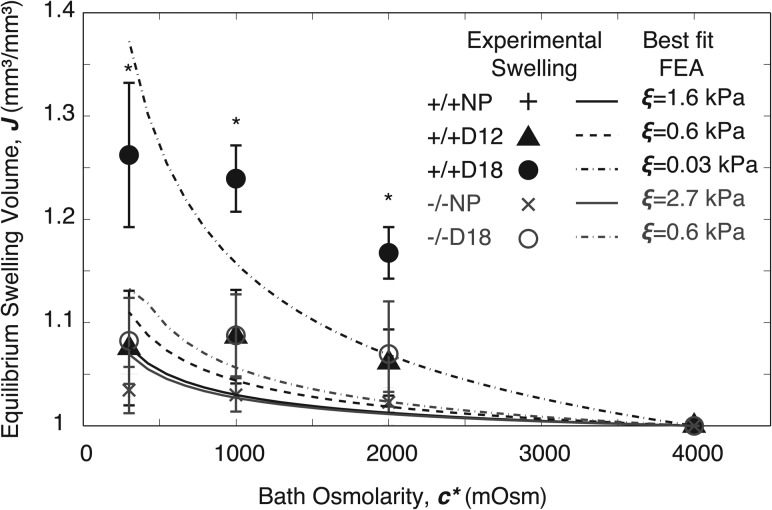

All samples increased in swelling volume with decreasing bath concentration (see Fig. 2). For normal parturition (Antxr2+/+), there was an increase in equilibrium swelling volume with gestation. These differences were significantly greater for the Antxr2+/+D18 samples compared with the Antxr2+/+D12 and Antxr2+/+NP samples in all three bath concentrations of 2000, 1000, and 300 mOsm (). For disrupted parturition (Antxr2-/-) there were no significant differences in swelling volume with gestation in any of the bath concentrations. The increased swelling volume with gestation in the Antxr2+/+ samples indicate weaker and softer collagens in the pregnant samples due to active collagen remodeling. The lack of increased swelling volume with gestation in the Antxr2-/- samples indicates a disruption in the collagen remodeling. The swelling volumes of the Antxr2-/-D18 samples were comparable to the Antxr2+/+D12 volumes, indicating that there is some remodeling occurring in the Antxr2-/- samples.

Fig. 2.

Equilibrium swelling volume with best fit FEA lines: N = 3 for all sample groups; and * indicates the statistical significance for Antxr2+/+D18 compared to all other groups ()

3.2. Collagen Elastic Modulus.

The proposed constitutive model was able to predict trends in increasing equilibrium swelling behavior with decreasing bath concentration, but did not satisfactorily capture the experimental data ( values from 0.65–0.74). The lines in Fig. 2 indicate the best fit lines from our proposed material model. For normal gestation the best fit collagen fiber elastic modulus values decreased with gestation from 1.6 to 0.06 kPa, while in disrupted parturition only decreased from 2.7 to 0.6 kPa.

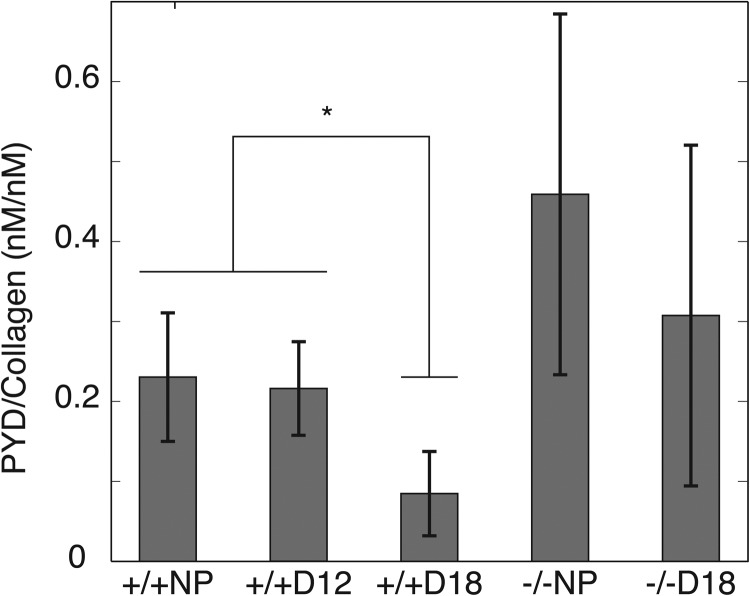

3.3. Collagen Crosslink Density.

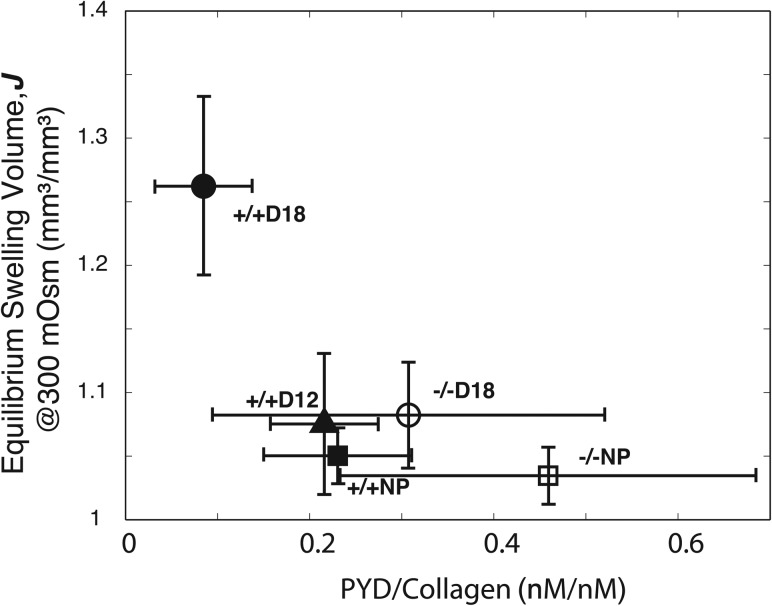

All samples contained detectable levels of PYD (Fig. 3) and trace or no amounts of DPYD. There was a significant decrease in the PYD crosslink density with progressing gestation (see Fig. 3) for the Antxr2+/+ samples. For the Antxr2-/- samples, there was only a slight decrease in the PYD density with gestation. These trends were inversely correlated with relative equilibrium volume in 300 mOsm NaCl, where tissue with a reduced collagen crosslink density is associated with increased swelling volume (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Ratio of pyridinoline content per collagen content (n = 7 to 9): * indicates the statistical significance between bracketed groups ()

Fig. 4.

Relative equilibrium swelling volume at 300 mOsm NaCl versus collagen crosslink density. A shift from the lower right hand corner to the upper left hand corner indicates active cervical remodeling, indicated by a decrease in collagen crosslink density with an increase in swelling volume. The Antxr2+/+ specimens exhibited active remodeling, whereas the Antxr2-/- specimens did not.

4. Discussion

The objectives of this study are to investigate how cervical mechanical properties and collagen crosslink density change as pregnancy progresses in normal and disrupted cervical remodeling and to evaluate how crosslink density correlates to mechanical properties of the tissue. The experimental results show that during pregnancy in Antxr2+/+ mice the cervix softens, which is evident by an increase in swelling during osmotic loading (see Fig. 2). This change is associated with a reduction in the collagen PYD crosslink density (see Fig. 4). In the Antxr2-/- mice, the cervix does not undergo significant softening with gestation, which is evident by no significant increases in the swelling volume with gestation. Similarly, there is no significant decrease in the PYD density with gestation. These results demonstrate that the cervical tissue from Antxr2-/- mice does not undergo the normal changes in collagen crosslink density associated with normal cervical remodeling and, as a result, the cervix does not soften appropriately as pregnancy progresses.

Investigating the Antxr2 model highlights the importance of collagen remodeling and the reduction of mature collagen crosslinks for a successful parturition. In this disrupted parturition model, the collagen crosslink density did not change significantly with progressing gestation due to a block in matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity [20]. Therefore, these results suggest that the MMP and the breakdown of mature crosslinked collagens are essential to cervical remodeling, softening, and parturition.

These results support our previous human tissue data, where we found that collagen turnover plays a role in the softening of cervical tissue. In earlier published studies, we found that pregnant human tissue is more soluble in weak acids, possibly indicating a disruption of collagen crosslinks [11]. To understand which types and degrees of collagen crosslinks are turning over during pregnancy, we are currently measuring the different collagen crosslink densities in human tissue via the LC-MSMS assay presented in this study. Lastly, both this study and our past human tissue studies support the hypothesis that collagen crosslink turnover and remodeling are key to tissue softening during pregnancy. Based on the evidence presented here, we hypothesize that preterm birth is associated with premature cervical remodeling characterized by accelerated collagen crosslink turnover. We are currently testing this hypothesis in pregnant cervical tissue taken from infection- and noninfection-based mouse models of preterm birth.

Cervical FCDs are relatively low compared to other tissues such as cartilage, which carry high FCD values ranging from −50 to −300 mEq/L. Therefore, we can conclude that an FCD exists in mouse cervical tissue enough to cause swelling during our osmotic loading tests. However, the dynamic changes in the HA during pregnancy does not significantly increase the FCD because of the coupled effect of increasing hydration (due to an increase in HA) and decreasing collagen fiber stiffness. We hypothesize that cervical tissue does not rely on its FCD for compressive strength, as in cartilage, and the most likely role of the GAG is in organizing the collagen fibrils. The proteoglycans reported in cervical tissue are mostly small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) with only a few GAG chains and do not carry much negative charge. The SLRPs are known to have roles in collagen fibril organization [46,47].

4.1. Material Model Considerations.

The continuous fiber distribution model with charged GAGs has been shown to predict many observed phenomena for cartilage, including osmotic swelling and tension-compression nonlinearity [37]. In this study, we attempt to capture the swelling behavior of the cervical tissue with this well-known soft tissue model, where we can individually account for the swelling tendencies of the GAGs and the counteractive tension of the collagen fibers. Due to the nature of our tests, we were unable to measure the GAGs in these samples. Therefore, we based the FCD calculations on detailed GAG measurements found in the literature (see Table 2) for a wild-type mouse strain [17]. Using Eqs. (2) and (4) the FCD in mouse cervical tissue changes from −8 to −10 mEq/L in pregnancy. We implemented these FCD values into the model and optimized the value of the collagen elastic modulus to match the swelling data.

The material model is able to show that for the given changes in the cervical FCD, the collagen fibers must remodel, or weaken, to allow for the observed volume change in the pregnant tissue. Even if the GAG content was off by 2 standard deviations of the reported values in Table 2, this variance cannot account for the swelling that is observed in the wild-type pregnant tissue sample. This is because the corresponding increase in the FCD results in only a 2% increase in swelling volume at the lowest bath concentration of 300 mOsm. However, the model does not accurately reflect the equilibrium swelling behavior of the cervix throughout the various bath concentrations. Therefore, this data can serve as a basis for the hypothesis that the changes in the swelling response are due mostly to the weakening of the collagen network. This hypothesis is supported by the significant decrease in the PYD density in normal remodeling, but no significant decrease in the mouse model of disrupted remodeling. Further mechanical tests are currently being done to further develop an appropriate constitutive material model for cervical tissue.

4.2. Limitations and Considerations.

The experimental results presented here are part of a necessary step to determine cervical material properties throughout pregnancy and to develop an appropriate constitutive model for the cervix. However, there are limitations due to the small sample size and model assumptions. The sample groups in this study only include three gestation time points for normal remodeling and the sample size of n = 3 for the osmotic loading test is small. Although this sample size shows a statistical significance between the D18 and NP/D12 samples, further testing could show differences between the NP and D12 cervices. Finally, in the osmotic loading experiments, the overall geometry of the cervix was estimated by idealizing the geometry as a cylinder and tracking the length and width of the cervix, as shown in Figs. 1(b) and 1(c). The actual geometry of the cervix is complex with geometric irregularities, including different diameters between the internal and external os and nonuniform bulges inside the tissue. Additionally, the DIC techniques presented here are based on 2D analysis, which assumes negligible out-of-plane motion.

The material model presented here is a necessary initial formulation to begin to interpret the data. It should be noted that this model is based on a randomly oriented fiber model, despite the anisotropic zones of collagen in the cervix [48,49]. The model fits have values between 0.65 and 0.74. This disagreement could be due to several factors. First, the experimental volume measurements are based on the overall volume change, which can lead to measurement error. Second, the finite element analysis (FEA) uses a representative material element of the cervix, after normalizing by the geometry. This model assumes homogeneous deformation throughout the cervical tissue. Since biological tissue is inherently inhomogeneous, nonuniform deformation could contribute to disagreements between the model and the experimental data. Third, the FCD values for the samples are based on the GAG measurements, not a direct measure of the actual negative charge of the tissue. Ongoing histological and biochemical studies are being conducted to better inform the material model.

Although the overall collagen architecture and many of the ECM components are similar between mice and humans, there are inherent differences such as the total collagen content (60–80% in humans and 10–20% in mice per dry weight). The overall objective of this study is to understand how changes in the ECM, specifically the collagen crosslink density, affects the mechanical swelling behavior of the cervix. One advantage of the mouse model is the availability of samples at defined gestation time points, which are difficult to obtain for human tissue. This advantage allows the investigation of the evolution of cervical ECM-structure properties throughout gestation, which is helpful to discern mechanisms of cervical remodeling. Once key mechanisms of cervical remodeling are identified in the mouse models, meaningful comparisons and hypotheses for human cervical remodeling can be formulated.

To address the limitations of this study and to validate the proposed material model, more samples will be obtained at various gestational ages and the equilibrium tensile response of the tissue is being measured. Although we expect our measurements to be a good estimate of the relative volume change, we will verify our measurements with DIC techniques to track the equilibrium strain on the tissue at each bath concentration. Ideally, 3D DIC techniques will be implemented, which will require techniques that can account for the refraction effects of imaging the tissue through the bath [50]. To fully understand the effect of the FCD on the mechanical response of the tissue, additional osmotic loading tests will be conducted with impermeable uncharged solutes. In this first formulation of the material model, the entropic contributions of the GAGs to interstitial pressure are ignored and will be the topic of alternative modeling strategies. The next iteration of the material model will include implementing an ellipsoidal fiber distribution model, where histological techniques, such as second harmonic generation, will be used to measure the fiber angle distribution. The LC-MSMS studies are currently underway to identify other relevant collagen crosslinks that are modified during cervical remodeling, including immature divalent crosslinks.

5. Conclusions

The cervix is a dynamic organ that changes properties through a remodeling process dictated by shifts in the ECM constituents. There is a need to understand how these dynamic shifts relate to quantitative measures for cervical material properties during pregnancy. We hypothesize that in preterm birth there is an acceleration of this remodeling process, leading to premature cervical softening. At the other end of the spectrum, in disrupted parturition we hypothesize that the lack of remodeling due to an Antxr2 deficiency results in no cervical softening during pregnancy. This study outlines a framework for studying normal and abnormal cervical remodeling by quantifying the relationship between the mechanical swelling behavior and PYD crosslink density. The results presented here show that osmotic loading can be used to measure differences in the mechanical response of the tissue between nonpregnant and pregnant samples. We found that cervical softening during normal pregnancy correlates with a decrease in the PYD crosslink density and when remodeling is disrupted, due to an Antxr2 deficiency, the resulting lack of PYD breakdown leads to a disruption in cervical softening during pregnancy and a lack of parturition.

Acknowledgment

This publication was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant No. UL1 TR000040. The authors would like to thank Pelisa Charles-Horvath from the Kitajewski Lab for providing genotypes of the mice, Noelia Zork in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology for help with processing LC-MSMS samples, and MiJung Kim and David Paik in the Department of Ophthalmology for protocol development for LC-MSMS processing. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH and NSF.

Glossary

Nomenclature

- Antxr2 =

Anthrax toxin receptor 2

- Antxr2+/+ =

Anthrax toxin receptor 2 wild-type

- Antxr2-/- =

Anthrax toxin receptor 2 knockout

- =

fixed charge density (FCD) in reference state

- =

bath osmolarity

- D12 =

pregnant, gestation day 12

- D18 =

pregnant, gestation day 18

- DPYD =

collagen crosslink deoxypyridinoline

- NP =

nonpregnant

- PYD =

collagen crosslink pyridinoline

- =

fiber stiffening parameter

- =

collagen fiber elastic modulus

- =

tissue hydration in reference state

Appendix: LC-MSMS Assays of Collagen Crosslinks and Hydroxyproline in Biological Tissue Samples

Materials.

Calibrating standards pyridinoline (PYD), deoxypyridinoline (DPD), and internal standard actetylated pyridinoline (AcPYD) were purchased from Quidel Corp. (San Diego, CA). Dihydroxylysinonorleucine (DHLNL) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Pentosidine (PEN) and hydroxyproline was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Deuterated hydroxyproline (hydroxyproline-D3) was purchased from C/D/N Isotopes Inc. (Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada). Heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA), LC/MS grade water, and acetonitrile and other common chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UPLC/MS/MS).

All assays were carried out on a Waters Xevo TQ MS ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA). The system was controlled by MassLynx Software 4.1. The sample hydrolysate was reconstituted in 40 of 1% HFBA solution containing 1 AcPYD as internal standard and thoroughly vortexed. The sample was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 1/4 C and the clear aqueous phase was transferred to an Agilent clear screw top micro sampling LC/MS vial (P/N 5184-3550. Agilent Tech, Santa Clara, CA) for the UPLC/MS/MS assay of collagen crosslinks [42,43]. The sample was maintained at 4 in the autosampler and a volume of 5 was loaded onto an ACQUITY UPLC HHS C18 column (2.1 mm inner diameter × 100 mm with 1.8 particles, Waters, P/N 186 003 533) and a 2.1 × 5 mm guard column with the same packing material (Waters, P/N 186 003 981). The column was maintained at 40 . The flow rate was 500 /min in a binary gradient mode with the following mobile phase gradient: initiated with 90% phase A (water containing 0.12% HFBA) and 10% mobile phase B (acetonitrile containing 0.06% HFBA). The gradient of acetonitrile was linearly increased to 35% over 4 min, then to 95% in 0.2 min, and maintained for 1 more minute. Then column was conditioned by using the initial gradient for 1 min and the next sample was injected. After injection, 5 from the remaining sample were transferred to another LC/MS vial and diluted with 995 of water containing 5 of hydroxyproline-D3 as internal standard for hydroxyproline assay [44]. The sample was vortexed well and 5 were injected to a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH Phenyl column (3 mm inner diameter × 100 mm with 1.7 particles, Waters, P/N 186 004 673), preceded by a 2.1 × 5 mm guard column containing the same packing (Waters, P/N 186 003 979). The column was maintained at 40. The flow rate was 500 /min in a binary gradient mode with the following mobile phase gradient: initiated with 99% phase A (water containing 0.1% formic acid) and 1% mobile phase B (acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid). The gradient of acetonitrile was linearly increased to 50% over 5 min, then to 95% in 0.2 min, and maintained for 1 more minute. The column was then conditioned by using the initial gradient for 1 min and the next sample was injected. Positive ESI-MS/MS with a multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was performed in all of the assays using the following parameters: a capillary voltage of 4 kV, source temperature of , desolvation temperature of , and desolvation gas flow of 1000 L/h. The optimized MRM parameters and quantification sensitivities are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Optimized MRM conditions and quantification limits

| Compound | MRM transition (m/z) | Cone voltage (V) | Collision energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyproline | 20 | 14 | |

| Hydroxyproline-D3 | 20 | 28 | |

| DHLNL | 31 | 22 | |

| PEN | 40 | 40 | |

| DPD | 44 | 28 | |

| PYD | 44 | 28 | |

| AcPYD (IS) | 44 | 28 |

Footnotes

See http://www.febio.org.

Contributor Information

Kyoko Yoshida, Graduate Research Assistant, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, e-mail: ky2218@columbia.edu.

Claire Reeves, Associate Managing Editor, BioScience Writers, LLC, Houston, TX 77025 , e-mail: creeves2002@gmail.com.

Joy Vink, Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY 10032 , e-mail: jyv2101@mail.cumc.columbia.edu.

Jan Kitajewski, Charles and Marie Robertson Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY 10032 , e-mail: jkk9@columbia.edu.

Ronald Wapner, Vice Chairman for Research, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY 10032 , e-mail: rw2191@mail.cumc.columbia.edu.

Hongfeng Jiang, Associate Research Scientist, Irving Institute for Clinical, and Translational Research, Department of Medicine, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY 10032 , e-mail: hj2238@mail.cumc.columbia.edu.

Serge Cremers, Assistant Professor of Medical Sciences, Irving Institute for Clinical, and Translational Research, Department of Medicine, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY 10032, e-mail: sc2752@mail.cumc.columbia.edu.

Kristin Myers, Assistant Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, e-mail: kmm2233@columbia.edu.

References

- [1]. Iams, J. D. and Berghella, V. , 2010, “Care for Women With Prior Preterm Birth,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 203(2), pp. 89–100. 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Harris, B. A. , Huddleston, J. F. , Sutliff, G. , and Perlis, H. W. , 1983, “The Unfavorable Cervix in Prolonged Pregnancy,” Obstet. Gynecol., 62(2), pp. 171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. ACOG, 2004, “Management of Postterm Pregnancy,” Obstet. Gynecol., 104, pp. 639–646. 10.1097/00006250-200409000-00052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Mahendroo, M. S. , 2012, “Cervical Remodeling in Term and Preterm Birth: Insights From an Animal Model,” Reproduction, 143(4), pp. 429–438. 10.1530/REP-11-0466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Harkness, M. L. R. and Harkness, R. D. , 1959, “Changes in the Physical Properties of the Uterine Cervix of the Rat During Pregnancy,” J. Physiol., 148(3), pp. 524–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Drzewiecki, G. , Tozzi, C. A. , Yu, S. Y. , and Leppert, P. C. , 2005, “A Dual Mechanism of Biomechanical Change in Rat Cervix in Gestation and Postpartum: Applied Vascular Mechanics,” Cardiovasc. Eng., 5(4), pp. 187–193. 10.1007/s10558-005-9072-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Hillier, K. and Wallis, R. M. , 1982, “Collagen Solubility and Tensile Properties of the Rat Uterine Cervix in Late Pregnancy: Effects of Arachidonic Acid and Prostaglandin F2 α ,” J. Endocrinol., 95, pp. 341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Buhimschi, C. S. , Sora, N. , Guomao, Z. , and Buhimschi, I. A. , 2009, “Genetic Background Affects the Biomechanical Behavior of the Postpartum Mouse Cervix,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 200, pp. 434.e1–434.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Kokenyesi, R. and Woessner, J. F., Jr. , 1990, “Relationship Between Dilatation of the Rat Uterine Cervix and a Small Dermatan Sulfate Proteoglycan,” Biol. Reprod., 42(1), pp. 87–97. 10.1095/biolreprod42.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Buhimschi, I. A. , Dussably, L. , Buhimschi, C. S. , Ahmed, A. , and Weiner, C. P. , 2004, “Physical and Biomechanical Characteristics of Rat Cervical Ripening Are Not Consistent With Increased Collagenase Activity,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 191(5), pp. 1695–1704. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Myers, K. M. , Socrate, S. , Tzeranis, D. , and House, M. , 2009, “Changes in the Biochemical Constituents and Morphologic Appearance of the Human Cervical Stroma During Pregnancy,” Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol., 144, pp. s82–s89. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Petersen, L. and Uldbjerg, N. , 1996, “Cervical Collagen in Non-Pregnant Women With Previous Cervical Incompetence,” Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol., 67(1), pp. 41–45. 10.1016/0301-2115(96)02440-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Holt, R. , Timmons, B. C. , Akgul, Y. , Akins, M. L. , and Mahendroo, M. S. , 2011, “The Molecular Mechanisms of Cervical Ripening Differ Between Term and Preterm Birth,” Endocrinology, 152(3), pp. 1036–1046. 10.1210/en.2010-1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Saito, M. and Marumo, K. , 2010, “Collagen Cross-Links as a Determinant of Bone Quality: a Possible Explanation for Bone Fragility in Aging, Osteoporosis, and Diabetes Mellitus,” Osteoporosis Int., 21(2), pp. 195–214. 10.1007/s00198-009-1066-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Marturano, J. E. , Arena, J. D. , Schiller, Z. A. , Georgakoudi, I. , and Kuo, C. K. , 2013, “Characterization of Mechanical and Biochemical Properties of Developing Embryonic Tendon,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 110(16), pp. 6370–6375. 10.1073/pnas.1300135110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Akins, M. L. , Luby-Phelps, K. , Bank, R. A. , and Mahendroo, M. S. , 2011, “Cervical Softening During Pregnancy-Regulated Changes in Collagen Cross-Linking and Composition of Matricellular Proteins in the Mouse,” Biol. Reprod., 84(5), pp. 1053–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Akgul, Y. , Holt, R. , Mummert, M. , Word, R. A. , and Mahendroo, M. S. , 2012, “Dynamic Changes in Cervical Glycosaminoglycan Composition During Normal Pregnancy and Preterm Birth,” Endocrinology, 153(7), pp. 3493–3503. 10.1210/en.2011-1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Myers, K. M. , Paskaleva, A. , House, M. , and Socrate, S. , 2008, “Mechanical and Biochemical Properties of Human Cervical Tissue,” Acta Biomater., 4(1), pp. 104–116. 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Hotchkiss, K. A. , Basile, C. M. , Spring, S. C. , Bonuccelli, G. , Lisanti, M. P. , and Terman, B. I. , 2005, “TEM8 Expression Stimulates Endothelial Cell Adhesion and Migration by Regulating Cell-Matrix Interactions on Collagen,” Exp. Cell Res., 305(1), pp. 133–144. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Reeves, C. V. , Wang, X. , Charles-Horvath, P. C. , Vink, J. Y. , Borisenko, V. Y. , Young, J. A. T. , and Kitajewski, J. K. , 2012, “Anthrax Toxin Receptor 2 Functions in ECM Homeostasis of the Murine Reproductive Tract and Promotes MMP Activity,” PLoS One, 7(4), pp. e34862–e34862. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Reeves, C. V. , Dufraine, J. , Young, J. A. T. , and Kitajewski, J. K. , 2009, “Anthrax Toxin Receptor 2 Is Expressed in Murine and Tumor Vasculature and Functions in Endothelial Proliferation and Morphogenesis,” Oncogene, 29(6), pp. 789–801. 10.1038/onc.2009.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Rmali, K. A. , Puntis, M. C. A. , and Jiang, W. G. , 2005, “TEM-8 and Tubule Formation in Endothelial Cells, Its Potential Role of Its vW/TM Domains,” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 334(1), pp. 231–238. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Nanda, A. , Carson-Walter, E. B. , Seaman, S. , Barber, T. D. , Stampfl, J. , Singh, S. , Vogelstein, B. , Kinzler, K. W. , and Croix, B. S. , 2004, “TEM8 Interacts With the Cleaved C5 Domain of Collagen Alpha 3(VI),”. Cancer Res., 64(3), pp. 817–820. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Bell, S. E. , Mavila, A. , Salazar, R. , Bayless, K. J. , Kanagala, S. , Maxwell, S. A. , and Davis, G. E. , 2001, “Differential Gene Expression During Capillary Morphogenesis in 3D Collagen Matrices: Regulated Expression of Genes Involved in Basement Membrane Matrix Assembly, Cell Cycle Progression, Cellular Differentiation and G-Protein Signaling,” J. Cell Sci., 114(15) pp. 2755–2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Bishop, E. H. , 1964, “Pelvic Scoring for Elective Induction,” Obstet. Gynecol., 24(2), p. 266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Iams, J. D. , Johnson, F. F. , Sonek, J. , Sachs, L. , Gebauer, C. , and Saumels, P. , 1995, “Cervical Competence as a Continuum: A Study of Ultrasonographic Cervical Length and Obstetric Performance,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 172(4), p. 10. 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91469-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Guzman, E. R. , Walters, C. , Ananth, C. V. , O'Reilly Green, C. , Benito, C. W. , Palermo, A. , and Vintzileos, A. M. , 2001, “A Comparison of Sonographic Cervical Parameters in Predicting Spontaneous Preterm Birth in High Risk Singleton Gestations,” Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol., 18(3), pp. 204–210. 10.1046/j.0960-7692.2001.00526.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Myers, K. M. , Socrate, S. , Paskaleva, A. , and House, M. , 2010, “A Study of the Anisotropy and Tension/Compression Behavior of Human Cervical Tissue,” ASME J. Biomech. Eng., 132, p. 021003. 10.1115/1.3197847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Caligioni, C. S. , 2001, Current Protocols in Neuroscience, John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Timmons, B. C. , Reese, J. , Socrate, S. , Ehinger, N. , Paria, B. C. , Milne, G. L. , Akins, M. L. , Auchus, R. J. , McIntire, D. , House, M. , and Mahendroo, M. S. , 2013, “Prostaglandins are Essential for Cervical Ripening in LPS-Mediated Preterm Birth but not Term or Antiprogestin-Driven Preterm Ripening,” Endocrinology, 155(1), pp. 287–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Maroudas, A. , 1976, “Balance Between Swelling Pressure and Collagen Tension in Normal and Degenerate Cartilage,” Nature (London), 260(5554), pp. 808–809. 10.1038/260808a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Basser, P. J. , Schneiderman, R. , Bank, R. A. , Wachtel, E. J. , and Maroudas, A. , 1998, “Mechanical Properties of the Collagen Network in Human Articular Cartilage as Measured by Osmotic Stress Technique,” Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 351(2), pp. 207–219. 10.1006/abbi.1997.0507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Narmoneva, D. A. , Wang, J. Y. , and Setton, L. A. , 2001, “A Noncontacting Method for Material Property Determination for Articular Cartilage From Osmotic Loading,” Biophys. J., 81, pp. 3066–3076. 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75945-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Cortes, D. H. and Elliott, D. M. , 2011, “Extra-Fibrillar Matrix Mechanics of Annulus Fibrosus in Tension and Compression,” Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol., 11(6), pp. 781–790. 10.1007/s10237-011-0351-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Elkin, B. S. , Shaik, M. A. , and Morrison, B. III , 2010, “Fixed Negative Charge and the Donnan Effect: A Description of the Driving Forces Associated With Brain Tissue Swelling and Oedema,” Philos. Trans. R. Soc., A, 368(1912), pp. 585–603. 10.1098/rsta.2009.0223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Mahendroo, M. S. , Porter, A. , Russell, D. , and Word, R. , 1999, “The Parturition Defect in Steroid 5 α-Reductase Type 1 Knockout Mice is Due to Impaired Cervical Ripening,” Mol. Endocrinol., 13(6), p. 981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Ateshian, G. A. , Rajan, V. , Chahine, N. O. , Canal, C. E. , and Hung, C. T. , 2009, “Modeling the Matrix of Articular Cartilage Using a Continuous Fiber Angular Distribution Predicts Many Observed Phenomena,” ASME J. Biomech. Eng., 131(6), p. 061003. 10.1115/1.3118773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Lanir, Y. , 1983, “Constitutive Equations for Fibrous Connective Tissues,” J. Biomech., 16(1), pp. 1–12. 10.1016/0021-9290(83)90041-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Overbeek, J. , 1956, “The Donnan Equilibrium,” Prog. Biophys. Biophys. Chem.,. 6, p. 57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Lanir, Y. , 1979, “A Structural Theory for the Homogeneous Biaxial Stress-Strain Relationships in Flat Collagenous Tissues,” J. Biomech., 12(6), pp. 423–436. 10.1016/0021-9290(79)90027-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Avery, N. C. , Sims, T. J. , and Bailey, A. J. , 2009, “Quantitative Determination of Collagen Cross-Links,” Methods in Molecular Biology, Extracellular Matrix Protocols, S. Even-Ram and Artym V., eds., Springer, New York, pp. 103–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Gineyts, E. , Borel, O. , Chapurlat, R. , and Garnero, P. , 2010, “Quantification of Immature and Mature Collagen Crosslinks by Liquid Chromatography–Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry in Connective Tissues,” J. Chromatogr. B: Biomed. Sci. Appl., 878(19), pp. 1449–1454. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Sroga, G. E. and Vashishth, D. , 2011, “UPLC Methodology for Identification and Quantitation of Naturally Fluorescent Crosslinks in Proteins: A Study of Bone Collagen,” J. Chromatogr. B: Biomed. Sci. Appl., 879(5), pp. 379–385. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Kindt, E. , Gueneva-Boucheva, K. , Rekhter, M. D. , Humphries, J. , and Hallak, H. , 2003, “Determination of Hydroxyproline in Plasma and Tissue Using Electrospray Mass Spectrometry,” J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal., 33(5), pp. 1081–1092. 10.1016/S0731-7085(03)00359-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Neuman, R. E. and Logan, M. A. , 1950, “The Determination of Collagen and Elastin in Tissues,” J. Biol. Chem., 186(2), pp. 549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Kalamajski, S. and Oldberg, Å. , 2010, “Matrix Biology,” Matrix Biol., 29(4), pp. 248–253. 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Westergren-Thorsson, G. , Norman, M. , Björnsson, S. , Endrésen, U. , Stjernholm, Y. , Ekman, G. , and Malmström, A. , 1998, “Differential Expressions of mRNA for Proteoglycans, Collagens and Transforming Growth Factor-β in the Human Cervix During Pregnancy and Involution,” Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis., 1406(2), pp. 203–213. 10.1016/S0925-4439(98)00005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Akins, M. L. , Luby-Phelps, K. , and Mahendroo, M. S. , 2010, “Second Harmonic Generation Imaging as a Potential Tool for Staging Pregnancy and Predicting Preterm Birth,” J. Biomed. Opt., 15, p. 026020. 10.1117/1.3381184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Zhang, Y. Y. , Akins, M. L. , Murari, K. K. , Xi, J. J. , Li, M.-J. M. , Luby-Phelps, K. , Mahendroo, M. S. , and Li, X. X. , 2012, “A Compact Fiber-Optic SHG Scanning Endomicroscope and Its Application to Visualize Cervical Remodeling During Pregnancy,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 109(32), pp. 12878–12883. 10.1073/pnas.1121495109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Ke, X. D. , Sutton, M. A. , Lessner, S. M. , and Yost, M. , 2009, “Robust Stereo Vision and Calibration Methodology for Accurate Three-Dimensional Digital Image Correlation Measurements on Submerged Objects,” J. Strain Anal. Eng., 43(8), pp. 689–704. 10.1243/03093247JSA425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]