Abstract

We report here the nucleotide sequence of a novel blaKPC-2-harboring incompatibility group N (IncN) plasmid, pECN580, from a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli sequence type 131 (ST131) isolate recovered from Beijing, China. pECN580 harbors β-lactam resistance genes blaKPC-2, blaCTX-M-3, and blaTEM-1; aminoglycoside acetyltransferase gene aac(6′)-Ib-cr; quinolone resistance gene qnrS1; rifampin resistance gene arr-3; and trimethoprim resistance gene dfrA14. The emergence of a blaKPC-2-harboring multidrug-resistant plasmid in an epidemic E. coli ST131 clone poses a significant potential threat in community and hospital settings.

TEXT

The rapid emergence and international spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing bacteria are becoming major clinical challenges among high-risk patients in hospitals and long-term acute care facilities (1, 2). KPCs have disseminated among different K. pneumoniae strains, but one predominant sequence type, sequence type 258 (ST258), has successfully spread worldwide (1). In contrast, the dissemination of KPCs in other enterobacterial species, such as Escherichia coli, has not followed the same pattern, and so far, KPC-producing E. coli is not as common as K. pneumoniae. However, a public health concern is that the highly successful uropathogenic E. coli ST131 harboring CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum β-lactamase that has spread in the community will gain further selective advantage as a result of acquiring carbapenem resistance (3, 4). KPCs have been identified in epidemic E. coli ST131 strains (4–6), but the resistance plasmids have not been fully characterized. Here, we report the complete sequence of a novel blaKPC-2-harboring incompatibility group N (IncN) plasmid from an E. coli ST131 isolate recovered from China.

E. coli strain ECN580 was isolated from a blood culture of a 28-year-old male from a tertiary care hospital in Beijing, China. He was hospitalized due to severe chronic renal failure and was on hemodialysis, with no history of foreign travel in the 6 months before isolation of the organism. The patient was started on empirical treatment with imipenem and cilastatin due to fever at 24 days of hospitalization. Carbapenem-resistant E. coli (ECN580) was identified from blood culture at 28 days of hospitalization, and the patient died 4 days later due to the KPC-associated infection. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) showed that the isolate belonged to the epidemic E. coli ST131 clone (7). PCR amplification of β-lactamase genes and sequencing of the amplicons demonstrated the presence of blaKPC-2, blaCTX-M-3, and blaTEM-1 (8–10). The blaKPC-bearing plasmid was successfully transferred by conjugation experiments using ECN580 as donor and E. coli J53AzR as the recipient, as described previously (11). The MICs of the parental isolate and its E. coli J53 transconjugant were determined by broth microdilution in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) using Sensititre GNX2F panels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute methods and interpretations (12, 13).

E. coli ECN580 exhibited resistance to all tested β-lactams and the inhibitors, including imipenem (MIC > 8 μg/ml), ertapenem (MIC > 8 μg/ml), meropenem (MIC > 8 μg/ml), doripenem (MIC > 4 μg/ml), cefotaxime (MIC > 32 μg/ml), ceftazidime (MIC > 32 μg/ml), cefepime (MIC > 32 μg/ml), aztreonam (MIC > 32 μg/ml), ticarcillin-clavulanate (MIC > 128/2 μg/ml), and piperacillin-tazobactam (MIC > 128/4 μg/ml), as well as co-trimoxazole (MIC > 4/76 μg/ml), amikacin (MIC > 64 μg/ml), gentamicin (MIC > 16 μg/ml), tobramycin (MIC > 16 μg/ml), ciprofloxacin (MIC > 4 μg/ml), and levofloxacin (MIC > 16 μg/ml), but it was susceptible to doxycycline (MIC ≤ 2 μg/ml), minocycline (MIC ≤ 2 μg/ml), tigecycline (MIC ≤ 0.25 μg/ml), colistin (MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml), and polymyxin B (MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml). The E. coli J53 transconjugant had a similar antimicrobial resistance profile as the parental strain but was intermediate against amikacin (MIC = 32 μg/ml) and ciprofloxacin (MIC = 2 μg/ml) and susceptible to gentamicin (MIC = 4 μg/ml) and levofloxacin (MIC = 2 μg/ml).

The blaKPC-2-harboring plasmid was isolated and purified from E. coli J53 transconjugant using the method described previously (14), and the plasmid genome was sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform. The sequencing reads were de novo assembled into consensus contigs using Velvet algorithms (15). The sequence gaps were closed by PCR and standard Sanger sequencing; putative open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted and annotated using the RAST server (http://rast.nmpdr.org) (16).

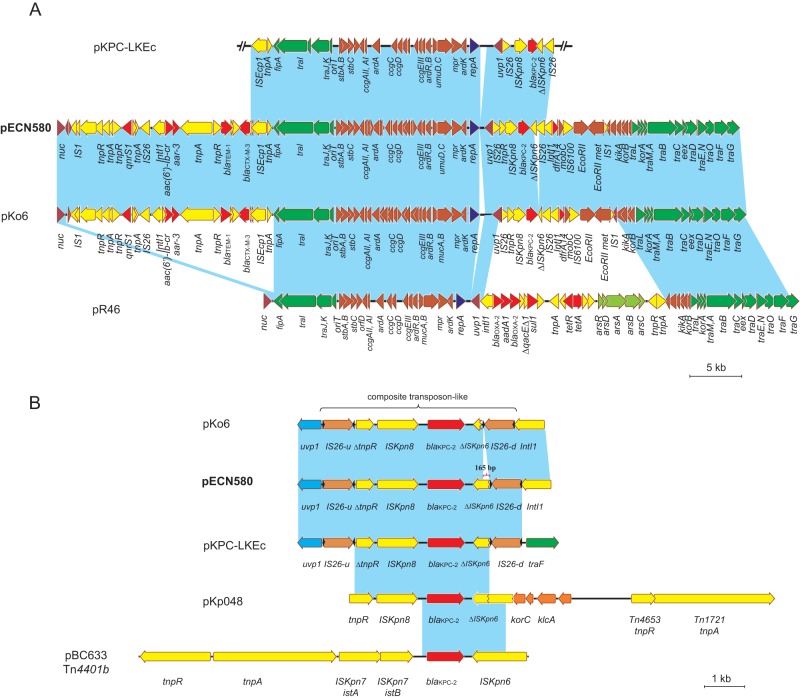

Plasmid pECN580 is 64,935 bp in size, with an average G+C content of 50.8%, and harbors 93 predicted ORFs (Fig. 1A). pECN is an incompatibility group N (IncN) plasmid, and a query against the plasmid MLST database (http://pubmlst.org/plasmid/) (17) assigns it to plasmid sequence type 7 (ST7), the same sequence type as other carbapenemase-carrying IncN plasmids, including pNDM-BTR (GenBank accession no. KF534788, harboring blaNDM-1), pK45-67VIM (GenBank accession no. HF955507, harboring blaVIM-1), and pKo6 (GenBank accession no. KC958437, harboring blaKPC-2). The IncN plasmid group is one of the most frequently encountered resistance plasmid types in Enterobacteriaceae of human and animal origin, and its members are typically of broad host range and able to transfer by conjugation (17, 18). The core region of pECN580, including a replication module (repA and RepA binding iterons), two transfer (tra) systems, a stability operon (stbAB, ardBR, and umuCD), and an antirestriction system (EcoRII and EcoRII met), is highly similar to those of other IncN plasmids, including the IncN prototype plasmid pR46 (GenBank accession no. AY046276) (Fig. 1A). pECN580 also has two distinct acquired regions harboring a panel of antibiotic resistance genes that are integrated at two previously described “hot spots” (a region downstream of uvp1 and a region between fipA and nuc) on the genome of IncN plasmids (14, 19). The first 8-kb acquired region is located downstream of the uvp1 gene and includes the carbapenemase gene blaKPC-2 and the trimethoprim resistance gene dfrA14. The second region is located between genes fipA and nuc and carries the β-lactamase genes blaCTX-M-3 and blaTEM-1, the quinolone resistance aminoglycoside acetyltransferase gene aac(6′)-Ib-cr, the quinolone resistance gene qnrS1, and the rifampin resistance gene arr-3.

FIG 1.

(A) Plasmid structures of pR46 (GenBank accession no. AY046276), pKo6 (GenBank accession no. KC958437), pECN580 (GenBank accession no. KF914891), and pKPC-LKEc (GenBank accession no. KC788405). Light-blue shading denotes shared regions of homology. ORFs are portrayed by arrows and are colored based on their predicted gene functions. Orange arrows indicate plasmid scaffold regions. The genes associated with the tra locus are indicated by green arrows, and replication-associated genes are indicated by dark-blue arrows. Antimicrobial resistance genes are indicated by red arrows, while arsenic resistance genes are indicated by light-green arrows. Other genes in the accessory region are indicated by yellow arrows. (B) blaKPC-harboring genetic elements in pBC633 (GenBank accession no. EU176012) (Tn4401b), pKp048 (GenBank accession no. FJ628167), pKo6 (GenBank accession no. KC958437), pECN580 (GenBank accession no. KF914891), and pKPC-LKEc (GenBank accession no. KC788405). Light-blue shading indicates shared regions of homology. Small black arrowheads flanking IS26 indicate the locations of IS26 invert repeats. The plasmid sequenced in this study (pECN580) is indicated with bold type.

Two class 1 integron-like elements were identified in pECN580. The first element is an IntI1-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-aar-3-Tn3-blaTEM-1-blaCTX-M-3-ISEcp1 gene cassette, located upstream of gene fipA. The second one harbors dfrA14 with its 3′-conserved sequence truncated by the insertion of an IS6100 element, located downstream of blaKPC. The quinolone resistance gene, qnrS1, is flanked by a Tn3-like transposase gene and a truncated IS2 element disrupted by the insertion of an IS26 element. This qnrS1-containing element is highly similar to the qnrS1-harboring region (>99.9% nucleotide identities) identified in pKOX_R1 in a Klebsiella oxytoca isolate from Taiwan (20).

The blaKPC-2 gene in pECN580 is carried on a 5-kb composite transposon-like element flanked by two IS26 elements, which is distinct from the blaKPC-bearing Tn4401 transposon and the genetic element described in plasmid pKp048 (21, 22) (Fig. 1B). The transposon-like element in pECN580 was initially described in plasmid pKPC-LKEc (GenBank accession no. KC788405) from a carbapenem-resistant ST410 E. coli isolated in Taiwan (Fig. 1B) (23). pKPC-LKEc is a chimeric plasmid composed of three regions that showed homology to IncI, IncN, and RepFIC plasmids (23). A comparison between pECN580 and pKPC-LKEc indicated that they share a highly similar 28.5-kb element (>99.9% nucleotide identities), flanked by an ISEcp1 and an IS26 element (Fig. 1A). This plasmid structure leads to speculation that the IS elements may facilitate recombination between the plasmids and explain the movement of the IncN region.

A further BLAST search of the pECN580 sequence against the GenBank database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) reveals that it is highly similar to plasmid pKo6, a multidrug-resistant plasmid from a Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae isolate in China (GenBank accession no. KC958437), with 99% query coverage and maximum 100% identities (Fig. 1A). There are only two differences between these closely related plasmids. The region between repA and uvp1 in pECN580, which harbors the RepA binding iterons repeats involved in the control of plasmid replication and copy numbers (24), is 780 bp shorter than that in pKo6 (Fig. 1A). The second major difference relates to the insertion sites of IS26-d (located downstream of blaKPC-2) on the composite transposon-like blaKPC-harboring element (Fig. 1B). IS26-d is inserted 224 bp upstream of the stop codon of ΔISKpn6 in pKo6, while it is integrated 389 bp upstream of that in pECN580 and pKPC-LKEc (Fig. 1B). Taken together, the high sequence similarity between pKo6 and pECN580 suggests they evolved from a common plasmid and that they have independently spread to different species (E. coli and K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, respectively).

In summary, we describe here the complete sequence of a novel blaKPC-2-harboring IncN plasmid from a multidrug-resistant E. coli ST131 isolate. The novel blaKPC-2-harboring composite transposon-like element found in pECN580 and related plasmids (pKPC-LKEc and pKo6) highlights the plasticity and complexity of these highly promiscuous plasmids. The spread of blaKPC-2-harboring multidrug-resistant plasmids, e.g., pECN580, into E. coli ST131, which is associated with community-acquired infections, poses a new public health threat.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete nucleotide sequence of pECN580 was deposited as GenBank accession no. KF914891.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant R01AI090155 from the National Institutes of Health (to B.N.K.). This study was also supported in part by funds and/or facilities provided by the Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Program (to R.A.B.), the Veterans Integrated Service Network 10 Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (VISN 10 GRECC [to R.A.B.]), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award R01 AI100560 and R01 AI063517 (to R.A.B.).

This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

B.N.K. discloses that he holds two patents that focus on using DNA sequencing to identify bacterial pathogens.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 January 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, Schwaber MJ, Daikos GL, Cormican M, Cornaglia G, Garau J, Gniadkowski M, Hayden MK, Kumarasamy K, Livermore DM, Maya JJ, Nordmann P, Patel JB, Paterson DL, Pitout J, Villegas MV, Wang H, Woodford N, Quinn JP. 2013. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13:785–796. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin MY, Lyles-Banks RD, Lolans K, Hines DW, Spear JB, Petrak R, Trick WE, Weinstein RA, Hayden MK, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters Program 2013. The importance of long-term acute care hospitals in the regional epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57:1246–1252. 10.1093/cid/cit500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. 2011. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1–14. 10.1093/jac/dkq415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YA, Qureshi ZA, Adams-Haduch JM, Park YS, Shutt KA, Doi Y. 2012. Features of infections due to Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli: emergence of sequence type 131. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55:224-231. 10.1093/cid/cis387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris D, Boyle F, Ludden C, Condon I, Hale J, O'Connell N, Power L, Boo TW, Dhanji H, Lavallee C, Woodford N, Cormican M. 2011. Production of KPC-2 carbapenemase by an Escherichia coli clinical isolate belonging to the international ST131 clone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4935–4936. 10.1128/AAC.05127-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naas T, Cuzon G, Gaillot O, Courcol R, Nordmann P. 2011. When carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC meets Escherichia coli ST131 in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4933–4934. 10.1128/AAC.00719-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wirth T, Falush D, Lan R, Colles F, Mensa P, Wieler LH, Karch H, Reeves PR, Maiden MC, Ochman H, Achtman M. 2006. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: an evolutionary perspective. Mol. Microbiol. 60:1136–1151. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05172.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Mediavilla JR, Endimiani A, Rosenthal ME, Zhao Y, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2011. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for detection and classification of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase gene (blaKPC) variants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:579–585. 10.1128/JCM.01588-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Chavda KD, Mediavilla JR, Zhao Y, Fraimow HS, Jenkins SG, Levi MH, Hong T, Rojtman AD, Ginocchio CC, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2012. Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of an epidemic KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 clone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3444–3447. 10.1128/AAC.00316-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa D, Vinué L, Poeta P, Coelho AC, Matos M, Sáenz Y, Somalo S, Zarazaga M, Rodrigues J, Torres C. 2009. Prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates in faecal samples of broilers. Vet. Microbiol. 138:339–344. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M, Tran JH, Jacoby GA, Zhang Y, Wang F, Hooper DC. 2003. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Shanghai, China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2242–2248. 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2242-2248.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CLSI. 2013. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 23rd informational supplement. CLSI M100-S23 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 13.CLSI. 2012. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard—9th ed. CLSI document M07-A9 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Chavda KD, Fraimow HS, Mediavilla JR, Melano RG, Jacobs MR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2013. Complete nucleotide sequences of blaKPC-4- and blaKPC-5-harboring IncN and IncX plasmids from Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated in New Jersey. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:269–276. 10.1128/AAC.01648-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zerbino DR, Birney E. 2008. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18:821–829. 10.1101/gr.074492.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. 2008. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Fernández A, Villa L, Moodley A, Hasman H, Miriagou V, Guardabassi L, Carattoli A. 2011. Multilocus sequence typing of IncN plasmids. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1987–1991. 10.1093/jac/dkr225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carattoli A. 2009. Resistance plasmid families in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2227–2238. 10.1128/AAC.01707-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carattoli A, Aschbacher R, March A, Larcher C, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2010. Complete nucleotide sequence of the IncN plasmid pKOX105 encoding VIM-1, QnrS1 and SHV-12 proteins in Enterobacteriaceae from Bolzano, Italy compared with IncN plasmids encoding KPC enzymes in the USA. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2070–2075. 10.1093/jac/dkq269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang TW, Wang JT, Lauderdale TL, Liao TL, Lai JF, Tan MC, Lin AC, Chen YT, Tsai SF, Chang SC. 2013. Complete sequences of two plasmids in a blaNDM-1-positive Klebsiella oxytoca isolate from Taiwan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:4072–4076. 10.1128/AAC.02266-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naas T, Cuzon G, Villegas MV, Lartigue MF, Quinn JP, Nordmann P. 2008. Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition of the beta-lactamase blaKPC gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1257–1263. 10.1128/AAC.01451-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen P, Wei Z, Jiang Y, Du X, Ji S, Yu Y, Li L. 2009. Novel genetic environment of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC-2 among Enterobacteriaceae in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4333–4338. 10.1128/AAC.00260-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YT, Lin JC, Fung CP, Lu PL, Chuang YC, Wu TL, Siu LK. 11 October 2013. KPC-2-encoding plasmids from Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 10.1093/jac/dkt409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chattoraj DK. 2000. Control of plasmid DNA replication by iterons: no longer paradoxical. Mol. Microbiol. 37:467–476. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01986.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]