Abstract

Yarn supercapacitors have great potential in future portable and wearable electronics because of their tiny volume, flexibility and weavability. However, low-energy density limits their development in the area of wearable high-energy density devices. How to enhance their energy densities while retaining their high-power densities is a critical challenge for yarn supercapacitor development. Here we propose a coaxial wet-spinning assembly approach to continuously spin polyelectrolyte-wrapped graphene/carbon nanotube core-sheath fibres, which are used directly as safe electrodes to assembly two-ply yarn supercapacitors. The yarn supercapacitors using liquid and solid electrolytes show ultra-high capacitances of 269 and 177 mF cm−2 and energy densities of 5.91 and 3.84 μWh cm−2, respectively. A cloth supercapacitor superior to commercial capacitor is further interwoven from two individual 40-cm-long coaxial fibres. The combination of scalable coaxial wet-spinning technology and excellent performance of yarn supercapacitors paves the way to wearable and safe electronics.

High-energy yarn supercapacitors are desirable for safe and wearable electronics. Here, Kou et al. use a coaxial wet-spinning assembly method to fabricate core-sheath fibres of polymer-wrapped carbon nanomaterials and demonstrate high-performance supercapacitor applications.

High-energy yarn supercapacitors are desirable for safe and wearable electronics. Here, Kou et al. use a coaxial wet-spinning assembly method to fabricate core-sheath fibres of polymer-wrapped carbon nanomaterials and demonstrate high-performance supercapacitor applications.

Supercapacitors are featured by the fast charge/discharge capacity, long lifecycle, wide range of operating temperatures and safety, which have been widely applied in the fields of digital cameras, mobile phones, electrical tools and pulse laser techniques1,2. Yarn supercapacitors (YSCs) are of particular interest because of their merits of tiny volume, high flexibility and weavability, and are promising for the next generation of wearable electronic devices3,4. Compared with batteries, supercapacitors show much lower-energy density, limiting their practical applications. Therefore, it is crucial to enhance their energy densities (E) while retaining their intrinsic high specific power densities (P) for the development of YSCs. Increasing the charge-storage capability and decreasing the volume of YSCs are two main approaches to enhance E. To improve the charge-storage capability of YSCs, conductive carbon materials with high specific area such as carbon fibre4, fibres of carbon nanotubes (CNTs)5, graphene3,6 and ordered mesoporous carbon7 were commonly selected as electrodes, and electrical-active materials with faradaic pseudocapacitance such as metal oxides (for example, MnO2)8 and conducting polymers (for example, polypyrrole9, polyaniline (PANI)5, and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene, PEDOT)10) were tried to incorporate into/on the electrodes. The capacitance (C) of YSCs was then enhanced from 2.4 to 86.8 mF cm−2 in the past 3 years4,11; however, the C and E values are still quite low for practical applications. Alternatively, decreasing the YSC volume shall be an effective way to increase volumetric E, yet it has a high risk of short circuit of electrodes.

To date, all of the as-prepared fibres used for fabricating YSCs are naked, and thus are easy to be short-circuited when they are close to each other3,5. Although post-coating a layer of poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) solid electrolyte partly reduces the probability of short circuit, the coating process is complicated and time-consuming, and it is hard to evenly coat the PVA layer. The resultant YSCs showed unsatisfied C and low E6. Therefore, it is still a big challenge to develop a simple yet effective approach to directly prepare sheath-protected fibre electrodes with ultra-high C and E.

In this work, a coaxial wet-spinning assembly strategy is proposed to readily prepare polyelectrolyte-wrapped carbon nanomaterial (for example, graphene, CNTs and their mixture) core-sheath fibres that are applied directly as contactable and interweaving YSC electrodes without the risk of short circuit. The resulting compact two-ply YSCs show high C and E values up to 177 mF cm−2 (158 F cm−3) and 3.84 μWh cm−2 (3.5 mWh cm−3), respectively. C and E are further improved to 269 mF cm−2 (239 F cm−3) and 5.91 μWh cm−2 (5.26 mWh cm−3) using liquid electrolyte. For the first time, a cloth supercapacitor with C higher than commercial capacitor is interwoven from two individual ultra-long (40 cm) continuous coaxial fibres. The combination of industrially viable coaxial wet-spinning assembly approach and ultra-high electrochemical performance of YSCs paves the way to wearable and safe electronics.

Results

Coaxial wet-spinning assembly approach to polyelectrolyte-wrapped graphene fibres

Our group has first demonstrated that continuous graphene fibres could be achieved by wet-spinning graphene oxide (GO) liquid crystals (LCs)12,13 followed by chemical reduction14,15, opening the door to macroscopic, multifunctional graphene fibres with widely potential applications including in the area of YSCs6. Recently, other groups also confirmed the fabrication of graphene fibres by either wet-spinning technology16,17,18,19 or dimensionally confined hydrothermal strategy20. The wet-spinning assembly approach was also successfully extended to create porous aerogel fibres21, hollow graphene fibres22 and nacre-mimetic graphene/polymer composite fibres15,23,24. The resulting graphene fibres are light-weight, electrically conductive, strong, flexible and chemical-resistant, which is promising for practical applications in multifunctional textiles and wearable electronics. However, despite these efforts in the fabrication of various structural fibres, all of them are also naked with the risk of short circuit when used as electrodes, which is unfavourable for the construction of safe electronics such as YSCs.

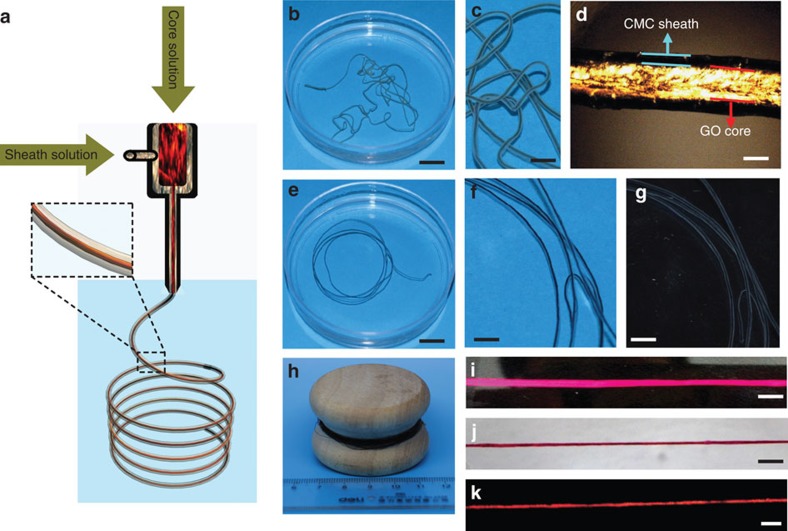

To solve this problem, we designed a coaxial wet-spinning assembly strategy to prepare polyelectrolyte-wrapped graphene fibres. Although coaxial electrospinning technology has been utilized to spin core-sheath nanofibres25, coaxial wet-spinning approach has never been established to prepare coaxial microfibres from colloidal nanoparticles because of the extreme difficulty for the selection of desirable coagulation bath as well as harmonious solvents of inner and outer components. Figure 1a shows the schematic illustration of our coaxial wet-spinning process (the photograph of corresponding equipment is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). The spinneret is featured by two inlets that connect the inner and outer channels, respectively. We first selected the aqueous GO LC as the inner spinning dope since it was easily spun into continuous microfibres according to the established wet-spinning assembly protocol. The aqueous solution of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) was chosen as the outer spinning dope because CMC is an ionically conductive while electrically insulative polyelectrolyte. Such a polymer sheath ensures fibre electrodes free of short circuit when intertwined together, while allowing ions to smoothly penetrate from the electrolyte matrix to electrodes simultaneously.

Figure 1. Coaxial wet-spinning assembly process and the as-prepared core-sheath fibres.

(a) Schematic illustration showing the coaxial spinning process. (b) A single intact wet GO@CMC fibre and its magnified image (c). (d) Polarized-light optical microscopy image of wet GO@CMC fibre indicating the core-sheath structure and the well-aligned GO sheets in the core part. (e) A wet RGO@CMC fibre and its magnified images with blue (f) and black (g) backgrounds. (h) The macroscopic photo of the RGO@CMC coaxial fibres. Wet (i) and dry (j) coaxial fibres dyed by rhodamine B and its fluorescence photos (k) in the dark under UV irradiation. Scale bars, 1 cm (b,e), 5 mm (c,f,g), 100 μm (d) and 2 mm (i–k).

Typically, the aqueous GO LC from the inner channel and the CMC aqueous solution from the outer channel were synchronously injected into the coagulating bath of ethanol/water (5:1 v/v) solution with 5 wt% CaCl2 (ref. 13) Wet CMC-wrapped GO coaxial fibres (GO@CMC) were then shaped rapidly (Fig. 1b), and the magnified photograph (Fig. 1c) showed clear core-sheath structure as designed. The GO dispersions were prepared according to the previous protocol15,26,27. Atomic force microscopy demonstrates that GO is a monolayer with the thickness of 0.7 nm (Supplementary Fig. 2). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images also prove the fine dispersity of GO sheets since no aggregation was observed (Supplementary Fig. 3). The solidification process of GO@CMC fibre was in situ traced using polarized-light optical microscopy. Vivid schlieren texture was found for the core part of GO because of its LC birefringence (Fig. 1d). During the solidification process, the bright texture was maintained, indicating the uniform alignment of GO sheets along the fibre axis in the shrinkage process (Supplementary Fig. 4). At the same time, the outer black polymer sheath without birefringence was well retained until full solidification, demonstrating the continuous core-sheath structure of GO@CMC fibre (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The GO@CMC fibres were chemically reduced by hydroiodic acid14. The colour of the core was then changed from brown (Fig. 1b,c) to dark while the polyelectrolyte sheath retained well (Fig. 1e–g). The chemically reduced GO@CMC fibres (RGO@CMC) were highly conductive with a conductivity of ~7,000 S m−1 as measured from their naked ends of the core. Such a high conductivity is comparable to that of neat graphene fibres and papers (~7,000–25,000 S m−1), confirming the integrity of the inner fibre and thus enabling it to be used as an electrode of YSCs. On the contrary, the whole fibre was electrically insulative as measured from its side face because of the protection of the insulative polymer sheath (Supplementary Fig. 5). Such well-defined sectorization of core-sheath fibre paves the way to safe assembly of microelectronics. Similar to the wet-spinning of neat graphene fibres, continuous GO@CMC fibres were obtained by the coaxial wet-spinning approach, as shown in Supplementary Movie 1. Consequently, ultra-long coaxial fibres up to 100 m were achieved (Fig. 1h), showing large-scale productivity of the multifunctional core-sheath fibres. In addition, the CMC sheath was swollen in ethanol/water (3:1 v/v) solution to colour the fibres with dyes such as rhodamine B, rendering the fibres colourful (Fig. 1i,j) and fluorescence-emissive (Fig. 1k).

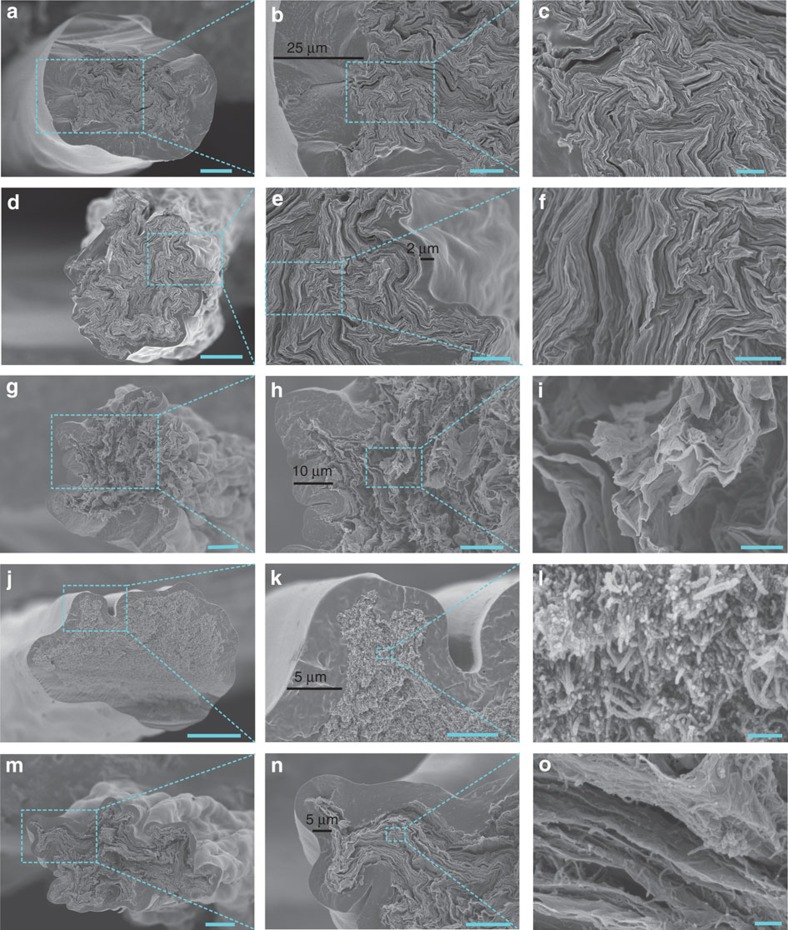

The microscopic morphology of the coaxial fibres was characterized using SEM. Figure 2a–c shows typical SEM images of a GO@CMC fibre with a GO core of ca. 50 μm and a CMC sheath of ca. 25 μm thickness. The GO core is featured by the compact layered structures with dentate bends, which is similar to the oriented structures of neat graphene fibres13. The CMC sheath wraps the core tightly without any gaps and voids, which is extremely important for the ion transport when served as supercapacitor electrodes, as evidenced by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images in Supplementary Fig. 6. Diameter of the GO core and thickness of the CMC sheath were readily adjusted by changing either the concentration or outflow velocity of GO and CMC spinning dopes (Fig. 2d–f and Supplementary Fig. 7). After the chemical reduction by hydroiodic acid, the layered structure of core becomes slightly fluffy and cellular (Fig. 2g–i), which could largely increase the accessible area of electrolyte. The coaxial fibres showed ultra-high flexibility with elongation of 8–10% and good mechanical strength (73–116 MPa; Supplementary Fig. 8). This robustness is propitious to their use in woven devices.

Figure 2. SEM images of coaxial fibres.

(a–c) GO@CMC spun with GO of 20 mg ml−1 and CMC of 12 mg ml−1. (d–f) GO@CMC spun with GO of 20 mg ml−1 and CMC of 4 mg ml−1. (g–i) RGO@CMC spun with GO of 20 mg ml−1 and CMC of 8 mg ml−1. (j–l) CNT@CMC spun with CNT of 10 mg ml−1 and CMC of 8 mg ml−1. (m–o) RGO+CNT@CMC spun with GO and CNT mixture (w/w, 1/1) of 20 mg ml−1 and CMC of 8 mg ml−1. Scale bars, 20 μm (a,d,g,j,m), 10 μm (b,h,n), 5 μm (e,k), 2 μm (c,f,i) and 0.2 μm (l,o).

Extension of coaxial wet-spinning assembly approach

Besides graphene, CNTs were also widely used as electrically conductive electrodes. Two main protocols have been developed to make macroscopic CNT fibres: dry drawing of aligned CNTs5 and wet-spinning of surfactant-stabilized CNTs with a coagulation bath of PVA aqueous solution28. However, it is still hard to directly wet-spin neat CNTs in the absence of surfactants or polymers because of their relatively poor dispersibility. In this paper, we realized the continuous wet-spinning of neat CNTs via the as-established coaxial spinning assembly approach (Supplementary Movie 2). Likewise, as the inner component of CNT dispersions was co-injected with the outer component of CMC dope into the coagulation bath, continuous CMC-wrapped CNT fibres (CNT@CMC) were produced. This process is similar to the coaxial electrospinning of nanoparticles without spinnability25. Figure 2j–l shows typical features of CNT@CMC fibres. The thickness of the sheath is 2–5 μm and the diameter of the CNT core is ca. 50 μm. The CNT core is compact without any voids, and the CNTs are also oriented along the fibre axis because of the shear stress of wet-spinning in the spinneret capillary.

We further extended the coaxial wet-spinning assembly approach to prepare continuous coaxial fibres with the core of mixture of RGO and CNTs, denoted as RGO+CNT@CMC (Fig. 2m–o). CNTs were coated on the surfaces of RGO densely and separated the adjacent RGO sheets aligned with layered structures (Fig. 2o). The coating of CNTs on RGO sheets greatly increases the specific area of the fibres, which is beneficial to energy storage when used as YSC electrodes. Moreover, replacing the outer layer of CMC by GO dispersion, we also prepared all-carbon RGO+CNT@RGO core-sheath fibres (Supplementary Fig. 9). Therefore, our coaxial wet-spinning assembly strategy is universal and versatile to create designed, multifunctional core-sheath fibres.

Coaxial fibres assembled two-ply YSCs

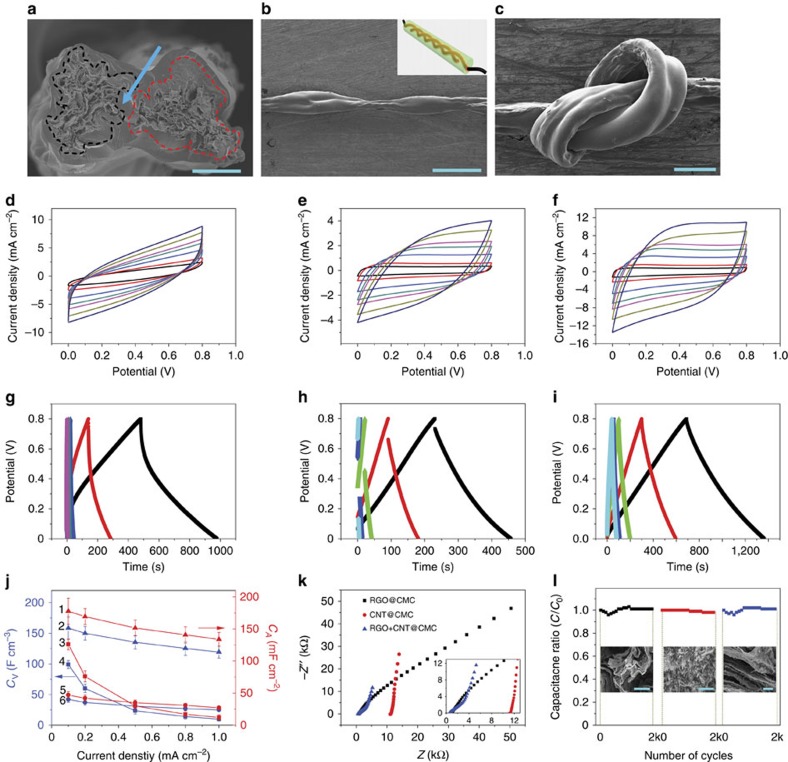

Given the unique attributes of the core-sheath coaxial fibres, we directly used them as safe electrodes for making two-ply YSCs. The YSCs were prepared by tightly intertwining two coaxial fibres followed by coating a layer of H3PO4-PVA gel electrolyte as ion source (Fig. 3a,b)8. The as-prepared YSCs are very safe, and short circuit never happened in the assembly and working process of YSCs because of the protection of the CMC sheath. The cross-sectional view of the YSC shows that the coaxial structure of the fibre electrodes is well reserved (Fig. 3a). The H3PO4-PVA gel electrolyte was coated on the coaxial fibre electrodes tightly and penetrated into the gap between them, which is important for the high capacitance performance of YSCs. The side view of the YSC indicates the uniform coating of PVA electrolyte and the clearly intertwined morphology of the two fibres (Fig. 3b). Significantly, the two-ply YSC is flexible enough to make a compact knot and the two fibre electrodes are observed along the YSC (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Two-ply YSCs and their electrochemical properties.

SEM images of cross-sectional (a) and side (b) view of a two-ply YSC. The arrow area in a is PVA/H3PO4 electrolyte and inset of b shows the schematic illustration of YSC. (c) SEM image of a two-ply YSC knot. CV curves of RGO@CMC (d), CNT@CMC (e) and RGO+CNT@CMC (f), scan rates increased from 10 to 20, 50, 80, 100, 150 and 200 mV s−1. GCD curves of RGO@CMC (g), CNT@CMC (h) and RGO+CNT@CMC (i), current density increased from 0.1 to 0.2, 0.5, 0.8 and 1 mA cm−2. (j) Dependence of CA and CV on the charge/discharge current density for RGO@CMC (3, 4), CNT@CMC (5, 6) and RGO+CNT@CMC (1, 2) YSCs. We selected five cross-sections and used the average value as the cross-sectional areas to determine the error bars. (k) Nyquist plots of RGO@CMC, CNT@CMC and RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs. (l) Normalized capacitance (C/C0, where C0 is the initial capacitance) versus cycle number for RGO@CMC (left), CNT@CMC (middle) and RGO+CNT@CMC (right) YSCs. Scale bars, 50 μm (a), 500 μm (b), 200 μm (c), 3 μm for left and 0.3 μm for middle and right (l).

We first assembled two kinds of two-ply YSCs with neat graphene (RGO@CMC) and neat CNT (CNT@CMC) coaxial fibres, respectively, to testify the feasibility of our strategy. The electrochemical properties of the as-prepared YSCs were characterized by cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements. For the YSCs intertwined with RGO@CMC fibres, the CV curves show a nearly rectangular shape and a rapid current response to voltage reversal at each end potential (Fig. 3d), which illustrates the good electrochemical performance of the YSCs. Figure 3g shows the GCD behaviour of RGO@CMC YSCs between 0 and 0.8 V at different current densities (0.1–1.0 mA cm−2). The GCD curves are close to triangular shape, confirming the formation of an efficient electric double layers and good charge propagation across the two fibre electrodes29. Gram capacitance does not provide a suitable basis for comparison in YSCs30. Instead, for the convenience of comparing with the previous results, areal capacitance (CA), length capacitance (CL) and volume capacitance (CV) are commonly utilized to evaluate the charge-storage capacity of YSCs (Table 1; note: the capacitances denote those of single electrodes). Calculated from the GCD curves (Fig. 3g), CAs of RGO@CMC YSCs are extremely high with capacitance of 127 mF cm−2 (114 F cm−3 for CV, 3.8 mF cm−1 for CL) at the current density of 0.1 mA cm−2. Such a capacitance is two orders of magnitude higher than those of previous graphene YSCs3.

Table 1. Comparison of our YSCs with the reported YSCs in terms of C and E.

| Ref. | Electrode materials |

C |

E |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA (mF cm−2) | CV (F cm−3) | CL (mF cm−1) | EA (μWh cm−2) | EV (mWh cm−3) | ||

| This study | RGO+CNT | 177 | 158 | 5.3 | 3.84 | 3.5 |

| 1 | Pen ink | 26.4 | 1.008 | 2.7 | ||

| 3 | Graphene | 1.7 | 0.17 | |||

| 5 | PANI/CNT | 38 | ||||

| 7 | CNT/OMC | 39.7 | 1.91 | 1.77 | ||

| 8 | CNT/MnO2 | 3.01 | 0.015 | 1.73 | ||

| 10 | PEDOT/CNT | 73 | 179 | 0.47 | 1.4 | |

| 11 | ZnO nanowires/MnO2 | 2.4 | 0.04 | 0.027 | ||

| 31 | CNT and Ti fibres | 0.6 | 0.024 | 0.15 | ||

| 32 | Graphene | 0.726 | 0.01 | |||

| 33 | ZnO nanowires/graphene | 2 | 0.025 | |||

| 38 | PANI/stainless steel | 41 | 0.95 | |||

| 39 | Carbon/MnO2 | 2.5 | 0.22 | |||

CNT, carbon nanotube; OMC, ordered mesoporous carbon; PANI, polyaniline; PEDOT, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene); YSC, Yarn supercapacitor.

For CNT@CMC YSCs, the CV curves also show the desired rectangular dependence of current density on applied potential because of fast ion transportation (Fig. 3e). The GCD curves exhibit a relatively high potential drop (Fig. 3h), which is likely stemmed from the larger resistance of carboxylic CNTs. Nevertheless, CNT@CMC YSCs still showed a CA 47 mF cm−2 (CV 42 F cm−3, CL 1.4 mF cm−1) at the current density of 0.1 mA cm−2, around 20 times higher than that of previous neat CNT YSCs5.

The two cases of RGO@CMC and CNT@CMC YSCs efficiently demonstrate that the polyelectrolyte sheath not only endows the fibre electrodes’ safety (free of short circuit when directly entangled together) but also remarkably improves the performance of YSCs. Therefore, the creation of coaxial fibre supercapacitors gives brand-new insight for the design and optimization of YSCs and other electronic devices.

Furthermore, the capacitance of supercapacitors at high charge–discharge current density is also crucial for their practical application as energy-storage devices. We also tested the charge–discharge performance at different current densities for the coaxial fibre YSCs. As shown in Fig. 3j, the CAs of RGO@CMC YSCs decreased quickly from 127 to 30 mF cm−2 as the current density increased from 0.1 to 0.5 mA cm−2, and then decreased gradually to 10 mF cm−2 at the current density of 1.0 mA cm−2. Even so, the CA values are still quite high at the high current densities as compared with the previous neat graphene fibre-based YSCs (1.2 mF cm−2 at current of 2 μA). The considerable difference of capacitance between low and high current densities partly counteracts the high potential of RGO@CMC YSCs. By contrast, the CNT@CMC YSCs showed very stable CA and still kept 57% of capacitance as the current density increased from 0.1 to 1 mA cm−2 (Fig. 3j), likely because of the smooth ion access in the porous structures of CNTs.

A question is then raised: is it possible to access ideal YSCs with both features of large CA and high rate capability by the synergistic assembly of graphene and CNTs?

Ultra-high performance of RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs

To exploit such a kind of desired YSCs, we also fabricated YSCs with the electrodes of RGO+CNT@CMC coaxial fibres. The fibres contained the electrically conductive core assembled homogeneously by RGO and CNTs (Fig. 2o). Interestingly, the RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs showed much larger area circled by rectangular shaped CV curves (Fig. 3f) and more regular triangular shaped GCD curves (Fig. 3i). The discharge time of RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs reached 700 s at the current density of 0.1 mA cm−2, almost equal to the sum of those of RGO@CMC (497 s) and CNT@CMC YSCs (174 s), indicating the prominent enhancement of stored charges (or capacitance) for the synergistically assembled electrodes of RGO+CNTs. Hence, the RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs demonstrated much better electrochemical performance with CA of 177 mF cm−2 (CV 158 F cm−3 and CL 5.3 mF cm−1) at the current density of 0.1 mA cm−2. This CA value is obviously higher than either CA of CNT@CMC YSCs or that of RGO@CMC YSCs, approximating the total capacitance of the two YSCs (127+47 mF cm−2) under the same testing condition. This result suggests that a single device of RGO+CNT@CMC YSC corresponds to the parallel connection of one RGO@CMC YSC and one CNT@CMC YSC. The capacitance of RGO+CNT@CMC YSC can be further highly improved to 269 mF cm−2 (CV 239 F cm−3 and CL 8.0 mF cm−1) by using liquid electrolyte of 1 M H2SO4 aqueous solution (Supplementary Fig. 10). More significantly, the RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs also inherited the high rate capability merit of CNT@CMC YSCs and exhibited high retention (75%) of capacitance at a high current density of 1 mA cm−2 (Fig. 3j). Accordingly, ideal YSCs with both natures of ultra-high capacitance and excellent rate capability are achieved by the combination of coaxial wet-spinning assembly approach and the synergistic effect of graphene and CNTs.

The superior electrochemical performance of RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs can be also explained by the smaller intrinsic internal resistance (R) measured from corresponding electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (Fig. 3k). RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs had a smaller R (0.55 KΩ) than RGO@CMC (0.87 KΩ) and CNT@CMC YSCs (11.22 KΩ) on the real axis at high frequency. Moreover, RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs showed a relatively short 45° Warburg region at the middle frequency, and a more vertical line at low frequency, indicating much better electrochemical performance31.

For comparison, we summarized the CA, CV and CL values of our and the previously reported YSCs in Table 1. Generally, for our YSCs with solid electrolyte of H3PO4/PVA, the CA (177 mF cm−2) based on the coaxial fibres is higher than those of the ever best YSCs (73 and 86.8 mF cm−2) by about 100% and is one to three order of magnitude higher than those of common YSCs (0.4–38 mF cm−2) even containing the additional electrically active materials such as metal oxides and conductive polymers32,33. The CL of our YSCs (5.3 mF cm−1) is comparable to the ever highest value (6.3 mF cm−1) and is one to three order of magnitude higher than those of other YSCs (0.0114–0.504 mF cm−1)1,33. Besides, CV of our YSCs is 158 F cm−3, which is comparable to that of CNT/PEDOT YSCs (179 F cm−3)10. For our YSCs with liquid electrolyte of 1 M H2SO4 aqueous solution, CV is improved to 239 F cm−3, which is obviously higher than that of CNT/PEDOT YSCs with liquid electrolyte (~167 F cm−3).

In addition, all these three kinds of YSCs showed almost no decay of capacitance within 2,000 times of charge–discharge cycles (Fig. 3l) over the range from 0 to 0.8 V at a current density of 1 mA cm−2. Leakage current was also measured by charging YSCs to 0.8 V and keeping them for 2 h (Supplementary Fig. 11). The current quickly stabilizes at 0.8 μA, which is essentially the leakage current through the device, indicating a small leakage current and high stability of our YSCs. Such excellent stability is competitive in the practical applications of YSCs.

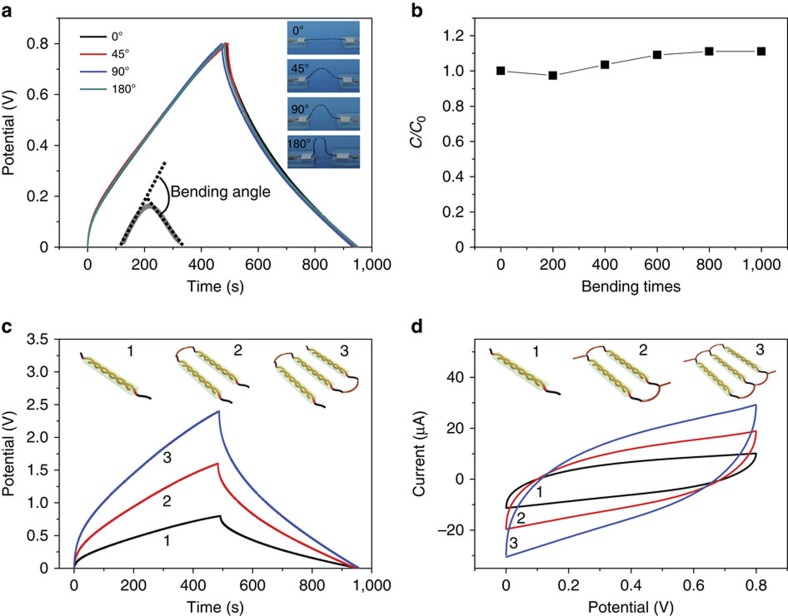

Flexibility and connections of two-ply YSCs

Unlike the liquid electrolyte with the risk of electrolyte leakage, our all-solid-state flexible YSCs are highly flectional and were even tied into a knot (Fig. 3c). We tested the GCD curves of the two-ply YSCs under different bending angles (for example, 45°, 90° and 180°), as shown in Fig. 4a. Almost no change for the charge–discharge curves was observed during the bending, proving that the inner structures of YSCs maintained well even at a sharp bending state. The coaxial fibre YSCs are flexible and robust enough to tolerate the long-term and repeated bending, and the capacitance only dropped 2% at 200 times of bending and rose persistently up to 111% at 1,000 times of bending (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. The capacitance performance of YSCs under bending and series/parallel connections.

(a) GCD curves of two-ply, all-solid-state, free-standing YSCs bended with different angles at the current density of 0.1 mA cm−2, and the insets are the digital photos of YSCs with different bending angles. (b) Capacitance ratio (C/C0, where C0 is the initial capacitance) versus bending times for YSCs with bending angles of 180°. (c) GCD curves of single, two and three YSCs connected in series, and the insets depict the cartoon of the YSCs connected in series. (d) CV curves of single, two and three YSCs connected in parallel, and the insets show the corresponding schematics (scan rates, 10 mV s−1).

Owing to the flexibility of our two-ply YSCs, we further made their serial and parallel connections to control over the operating voltage and current. With almost the same discharge time, the operating voltage can be elevated from 0.8 V for single YSC to 1.6 and 2.4 V by connecting two and three YSCs in series, respectively (Fig. 4c). The output currents of two and three YSCs connected in parallel are doubled and tripled, respectively, with a same potential window of 0–0.8 V (Fig. 4d).

Coaxial fibre-woven cloth supercapacitors

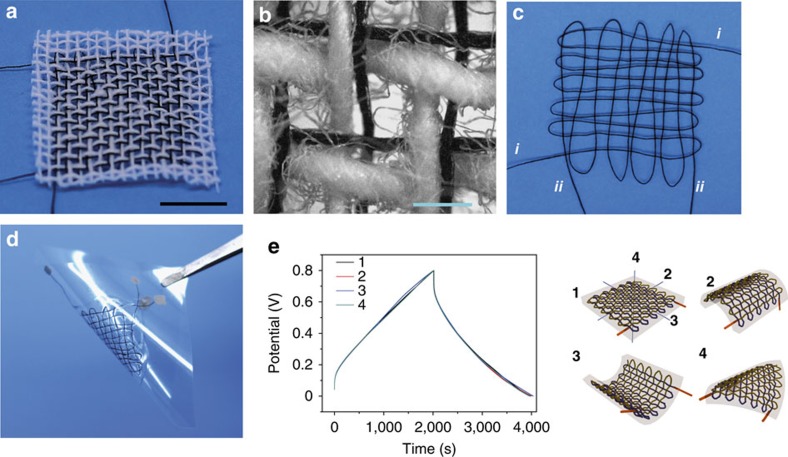

The integration of high flexibility and scalable fabrication of our coaxial fibres promises highly potential application in garment devices, biomedical and antimicrobial textiles, and personal electronics34. Figure 5a shows a co-woven cloth using multiple cotton yarns and two intact coaxial fibres. The fibres are flexible enough to shuttle back and forth without fracture, as demonstrated by the optical microscopy image of the co-woven cloth (Fig. 5b). For the first time, we used two individual 40-cm-long coaxial RGO+CNT@CMC fibres as anode and cathode to interweave a cloth supercapacitor (Fig. 5c,d). Previously, multiple short CNT/PANI fibres were woven into a piece of cloth, but no electrochemical property was evaluated5; one two-ply supercapacitor (5 cm long) was straightly drawn across a cotton grove, but no interweaving of two electrodes was demonstrated10. In other words, cloth supercapacitors interwoven from individual intact fibre electrodes have never been reported. In our case, short circuit of the fibre electrodes was avoided at the crossing of the cloth because of the unique coaxial insulated polyelectrolyte-wrapped structure. Our cloth supercapacitor showed a capacitance of 28 mF at the current of 10 μA (Fig. 5e), higher than 25 mF of commercial supercapacitors35. The corresponding GCD curves were unchanged under the bending angle of 180° along the three directions shown in the inset of Fig. 5e, revealing the excellent bendability of our cloth supercapacitors woven from coaxial fibres.

Figure 5. Supercapacitor based on the cloth woven by coaxial fibres.

(a) Two intact coaxial fibres woven with cotton fibres. (b) Optical macroscopic image of a. (c) Cloth woven by two individual coaxial fibres. (d) Supercapacitor device based on the cloth fabricated by two coaxial fibres (denoted as i and ii, respectively). (e) GCD curves of the cloth supercapacitor (1 represents initial cloth supercapacitor without bending, and 2, 3, 4 show cloth supercapacitor with bending angles of 180° along three directions). Scale bars, 1 cm (a) and 200 μm (b).

Discussion

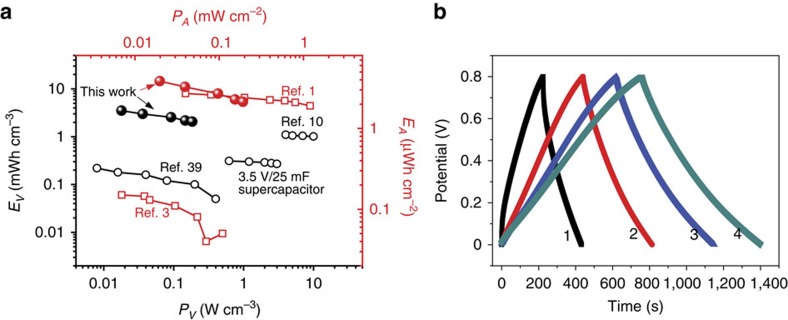

As shown above, our two-ply YSCs possess the various merits of ultra-high capacitance, good rate capability, excellent cycling stability, high flexibility and knittability, and fine modulability of connection. Besides, E and P of supercapacitors are also quite important parameters for their real applications3,4,36. We then draw the profile of P versus E, so-called Ragone plot37, derived from GCD curves at various current densities from 0.1 to 1 mA cm−2 for the RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs (Fig. 6a). As a result, the YSC using solid electrolyte shows areal energy density (EA) of 3.84 μWh cm−2 and volumetric energy density (EV) of 3.5 mWh cm−3, while the areal power density (PA) and volumetric power density (PV) is 0.02 mW cm−2 and 0.018 W cm−3 at the current density of 0.1 mA cm−2, respectively.

Figure 6. Volumetric and areal energy versus average power densities and the shell thickness effect for RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs.

(a) Ragone plots compared with the selected previous fibre-shaped YSCs with solid electrolyte. (b) GCD curves at the current density of 0.1 mA cm−2 for RGO+CNT@CMC fibres with CMC shell thickness of 0 μm (1), 2 μm (2), 10 μm (3) and 25 μm (4).

Notably, as far as we know, our EA value is the highest energy density for all of reported YSCs (Table 1). As a quantitative comparison, it corresponds to 142 times of YSC based on ZnO nanowires/MnO2 (0.027 μWh cm−2)11, 26 times of YSC based on CNT and Ti fibres (0.15 μWh cm−2)31, 22 times of YSC based on core-sheath graphene fibres (0.17 μWh cm−2)3, 4 times of YSC based on PANI/stainless steel (0.95 μWh cm−2)38, 2.17 times of YSC based on CNT/ordered mesoporous carbon (1.77 μWh cm−2)7 and 1.42 times of YSC based on pen ink (2.7 μWh cm−2)1. Alternatively, EV of RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs is 3.5 mWh cm−3, around 16 times of YSC based on carbon/MnO2 (0.22 mWh cm−3)39 and two times of YSC based on CNT/MnO2 fibres (1.73 mWh cm−3)8.

The excellent electrochemical performance of our YSCs is likely resulted from three effects. First, during coagulation and drying process for the coaxial wet-spinning technology, the shrinkage speed of the outer CMC layer is faster than that of the inner GO or CNTs core, making CMC sheath wrap the graphene or CNTs tightly (Supplementary Fig. 6). This is crucial for better ion transport at the interface between electrolyte and the electrodes. Second, this coaxial wet-spinning process renders the pore structures of inner GO or CNTs core more elaborate because of the uniform shrinkage force of the CMC sheath. The thicker the CMC sheath is, the stronger the shrinkage force would be generated during the drying process. Therefore, the CA of RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs increased from 35 to 103, 145 and 177 mF cm−2 with increasing the thickness of CMC sheath from 0 (Supplementary Fig. 12) to 2, 10 and 25 μm (Supplementary Fig. 13). To further demonstrate the merits of the coaxial wet-spinning assembly strategy, we assembled two more YSCs in control experiments using naked RGO+CNT fibres fabricated by conventional wet-spinning method12 and RGO+CNT fibres post-coated with CMC as electrodes, respectively. After post-coating a CMC layer on the surface of naked RGO+CNT fibres, the capacitance (39 mF cm−2) is almost same as that of the initial naked RGO+CNT fibre without CMC coating (35 mF cm−2) but much smaller than that of coaxial wet-spun fibres (103 mF cm−2) at the current density of 0.1 mA cm−2. The CV curves of CMC post-coating YSC and naked fibre YSC are almost overlapped, whereas much smaller than those of coaxial wet-spun fibre YSC (Supplementary Fig. 14e). These control experiments clearly demonstrated that CMC has no pseudocapacitance effect and the dramatic improvement of electrochemical performance for coaxial wet-spun fibre-based YSCs is mainly ascribed to the coaxial wet-spinning assembly process. Meanwhile, the rate capability is also excellent for the coaxial wet-spun fibre YSCs. For RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs with CMC thickness of 2, 10 and 25 μm, the capacitances are retained by 84%, 77% and 75%, respectively, when the current density is increased from 0.1 to 1 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 13). The slightly different rate capability is likely caused by the increased thickness of CMC, which might lead to a longer distance between the two fibre electrodes. As a result, ion transport is affected to some extent at high current densities. Finally, the synergistic effect that arose from the hierarchical structures of CNT-coated graphene makes the C and E of RGO+CNT@CMC YSC superior to either RGO @CMC or RGO+CNT@CMC YSC. Therefore, the combination of the coaxial wet-spinning process and the hierarchical structures of CNT-coated graphene mainly contributes to the high performance of RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs.

In conclusion, we proposed and demonstrated for the first time a coaxial wet-spinning assembly strategy to prepare core-sheath fibres of polymer-wrapped carbon nanomaterials. The protocol is simple, industrially viable and general for both nanoparticles of graphene and CNTs that cannot be wet-spun continuously by previous approaches. The as-made coaxial fibres are flexible and robust enough to be intertwined, knotted and woven. Owing to the coating of electrically insulative polyelectrolyte, the coaxial fibres were used directly to assembly two-ply intertwined safe YSCs. The resultant RGO+CNT@CMC YSCs showed ultra-high capacitance, the record energy density and excellent cycle stability under bending. A highly bendable cloth supercapacitor was woven from two 40-cm-long coaxial fibres, promising the application of our YSCs in garment devices, intelligent microsensors and other wearable electronics. The electrically active metal oxides (for example, MnO2, NiO and RuO2) and conductive polymers can widely be integrated into the coaxial fibres to further improve the electrochemical performance of YSCs40, offering a wide approach to the next generation of smart, safe and flexible devices.

Methods

Preparation of coaxial fibres by coaxial wet-spinning

GO and CNT dispersions were prepared according to the previous reports41,42,43,44. For preparing RGO@CMC, GO dispersion was concentrated to ~20 mg ml−1 and transferred to an injection syringe connected with an inner core of spinneret. CMC (Aladdin) dissolved in water with concentration of ~8 mg ml−1 was transferred to the outer channel of spinneret. The typical extruded velocities of inner and outer layers were set at 10 and 40 μl min−1, respectively. The coagulating bath was ethanol/water (5:1 v/v) solution with 5 wt% CaCl2. After coagulation for 30 min, the fibres were immersed in hydriodic acid ethanol/water (5:1 v/v) solution for 1 h at 95 °C for reduction followed by ethanol washing and drying in air, affording RGO@CMC coaxial fibres. The CNT@CMC coaxial fibres were prepared with the same procedure by replacing GO with CNT aqueous dispersions. Likewise, for spinning RGO+CNT@CMC coaxial fibres, GO and CNT dispersions were first mixed with weight ratio of 1/1 by magnetic stirring for 2 h and then were used as the inner spinning dope.

Preparation of PVA solid electrolyte

Water (10 ml) and phosphoric acid (10 ml) were mixed by magnetic stirring for 30 min in a 250-ml glass bottle. PVA (10 g, Mw 89,000–98,000) dissolved in 90 ml water at 90 °C was added in the above solution and was kept stirring for 1 h.

Preparation of free-standing all-solid-state fibre supercapacitors

Two coaxial fibres were twisted together to form two-ply supercapacitor electrodes. They were then coated with PVA electrolyte by dip-coating method and solidification at 40 °C.

Apparatus for characterizations

Atomic force microscopy images were taken in the tapping mode by carrying out on a NSK SPI3800. SEM images were taken on a Hitachi S4800 field-emission SEM system. The core-sheath fibre was cut into slices by microtome and observed by TEM (FEI-PHILLIPS CM 200 electron microscope). Polarized-light optical microscopy observations were performed with a Nikon E600POL. CV, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and GCD measurements were performed using an electrochemical workstation (CHI660e, CH Instruments Inc.). The tensile stress–strain tests were performed on a Microcomputer Control Electronic Universal Testing Machine made by REGER in China (RGWT-4000-20).

Calculation of the electrochemical capacitance for two-ply electrode supercapacitors

The two-ply YSC is a symmetric two-electrode solid-state supercapacitor. The areal capacitance (CA) was derived from the equation: CA=I × t × U−1 × S−1, where I stands for discharge–discharge current, t is the discharge time, U represents the potential window and S is the surface area of single yarn in the overlapping portion, equal to the circumference of the cross-section multiplied by the length (L) of overlapped portion of fibre electrodes5. Circumference is measured by using a soft rope walked along the cross profile of the SEM images of the fibres. CV was derived from the equation: CV=CA × S × V−1. V is the volume of the fibre electrode, which is equal to the cross-sectional area multiplied by the length of overlapped portion of fibre electrodes. Cross-sectional areas are measured through Photoshop (image-processing software) by comparing the pixel with that of an internal reference. The length capacitance CL was derived from the equation: CL=CA × S × L−1. The areal energy density (E) and areal power density (P) of the YSCs can be obtained from EA=0.125 × CA × U2 and PA=EA × t−1. The volumetric energy density (E) and volumetric power density (P) of the YSCs can be obtained from EV=0.125 × CV × U2 and PV=EV × t−1.

Author contributions

L.K. and C.G. conceived and designed the research, analysed the experimental data and wrote the paper; C.G. supervised and directed the project. T.H., B.Z., Y.H., X.Z., K.G. and H.S. contributed to some experiments and took part in discussions.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Kou, L. et al. Coaxial wet-spun yarn supercapacitors for high-energy density and safe wearable electronics. Nat. Commun. 5:3754 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4754 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-14

Coaxial wet-spinning assembly process of GO@CMC fibres.

Coaxial wet-spinning assembly process of CNT@CMC fibres.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 51173162 and no. 21325417), Qianjiang Talent Foundation of Zhejiang Province (no. 2010R10021), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 2013XZZX003) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (no. R4110175).

References

- Fu Y. et al. Fibre supercapacitors utilizing pen ink for flexible/wearable energy storage. Adv. Mater. 24, 5713–5718 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Zhang L. & Zhang J. A review of electrode materials for electrochemical supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 797–828 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y. et al. All-graphene core-sheath microfibres for all-solid-state, stretchable fibriform supercapacitors and wearable electronic textiles. Adv. Mater. 25, 2326–2331 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le V. T. et al. Coaxial fibre supercapacitor using all-carbon material electrodes. ACS Nano 7, 5940–5947 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Meng Q., Zhang Y., Wei Z. & Miao M. High-performance two-ply yarn supercapacitors based on carbon nanotubes and polyaniline nanowire arrays. Adv. Mater. 25, 1494–1498 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T. et al. Flexible, high performance wet-spun graphene fiber supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 3, 23957–23962 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ren J. et al. Flexible and weaveable capacitor wire based on a carbon nanocomposite fiber. Adv. Mater. 25, 5695–5670 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J. et al. Twisting carbon nanotube fibres for both wire-shaped micro-supercapacitor and micro-battery. Adv. Mater. 25, 1155–1159 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J. et al. Solid-State High performance flexible supercapacitors based on polypyrrole-MnO2-carbon fibre hybrid structure. Sci. Rep. 3, 2286 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. A. et al. Ultrafast charge and discharge biscrolled yarn supercapacitors for textiles and microdevices. Nat. Commun. 4, 1970 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J. et al. Fibre supercapacitors made of nanowire-fibre hybrid structures for wearable/flexible energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 1683–1687 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. & Gao C. Graphene chiral liquid crystals and macroscopic assembled fibres. Nat. Commun. 2, 571 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Sun H., Zhao X. & Gao C. Ultrastrong fiber assembled from giant graphene oxide sheets. Adv. Mater. 25, 188–193 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei S., Zhao J., Du J., Ren W. & Cheng H.-M. Direct reduction of graphene oxide films into highly conductive and flexible graphene films by hydrohalic acids. Carbon. 48, 4466–4474 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Kou L. & Gao C. Bioinspired design and macroscopic assembly of poly(vinyl alcohol)-coated graphene into kilometers-long fiber. Nanoscale 5, 4370–4378 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalili R. et al. Scalable one-step wet-spinning of graphene fiber and yarns from liquid crystalline dispersions of graphene oxide: towards multifunctional textiles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 5345–5354 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Cong H.-P., Ren X.-C., Wang P. & Yu S.-H. Wet-spinning assembly of continuous, neat, and macroscopic graphene fibers. Sci. Rep. 2, 613 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. et al. Toward high performance graphene fibers. Nanoscale 5, 5809–5815 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Liu Z., Sun H. & Gao C. Highly electrically conductive Ag-doped graphene fibers as stretchable conductors. Adv. Mater. 25, 3249–3253 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z. et al. Facile fabrication of light, flexible and multifunctional graphene fibers. Adv. Mater. 24, 1856–1861 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Zhang Y., Li P. & Gao C. Strong, conductive, lightweight, neat graphene aerogel fibers with aligned pores. ACS Nano 6, 7103–7113 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. et al. Large-scale spinning assembly of neat, morphology-defined, graphene-based hollow fibres. ACS Nano 7, 2406–2412 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Xu Z. & Gao C. Multifunctional, supramolecular, continuous artificial nacre fibres. Sci. Rep. 2, 767 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Xu Z., Hu X. & Gao C. Lyotropic liquid crystal of polyacrylonitrile-grafted graphene oxide and its assembled continuous strong nacre-mimetic fibres. Macromolecules 46, 6931–6941 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Zussman E., Yarin A. L., Wendorff J. H. & Greiner A. Compound core-sheath polymer nanofibres by co-electrospinning. Adv. Mater. 15, 1929–1932 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Kou L. & Gao C. Making silica nanoparticle-covered graphene oxide nanohybrids as general building blocks for large-area superhydrophilic coatings. Nanoscale 3, 519–528 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou L., He H. & Gao C. Click chemistry approach to functionalize two-dimensional macromolecules of graphene oxide nanosheets. Nano Micro. Lett. 2, 177–183 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Vigolo B. et al. Macroscopic fibres and ribbons of oriented carbon nanotubes. Science 290, 1331–1334 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J. J. et al. Ultrathin planar graphene supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 11, 1423–1427 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogotsi Y. & Simon P. True performance metrics in electrochemical energy storage. Science 334, 917–918 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. et al. An integrated ‘energy wire’ for both photoelectric conversion and energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 11977–11980 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Sheng K., Yuan W. & Shi G. A high-performance flexible fibre-shaped electrochemical capacitor based on electrochemically reduced graphene oxide. Chem. Commun. 49, 291–293 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J. et al. Single-fiber-based hybridization of energy converters and storage units using graphene as electrodes. Adv. Mater. 23, 3446–3449 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost K. et al. Carbon coated textiles for flexible energy storage. Energ. Environ. Sci. 4, 5060–5067 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Pech D. et al. Ultrahigh-power micrometre-sized supercapacitors based on onion-like carbon. Nat. Nanotech. 5, 651–654 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y. et al. Carbon materials for chemical capacitive energy storage. Adv. Mater. 23, 4828–4850 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Service R. F. New ‘supercapacitor’ promises to pack more electrical punch. Science 313, 902 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. et al. Integrated power fibre for energy conversion and storage. Energ. Environ. Sci. 6, 805–812 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X. et al. Fibre-based all-solid-state flexible supercapacitors for self-powered systems. ACS Nano 6, 9200–9206 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon P. & Gogotsi Y. Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 7, 845–854 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H. & Gao C. General approach to individually dispersed, highly soluble, and conductive graphene nanosheets functionalized by nitrene chemistry. Chem. Mater. 22, 5054–5064 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Kan L., Xu Z. & Gao C. General avenue to individually dispersed graphene oxide-based two-dimensional molecular brushes by free radical polymerization. Macromolecules 44, 444–452 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Gao C., Vo C. D., Jin Y. Z., Li W. & Armes S. P. Multihydroxy polymer-functionalized carbon nanotubes: synthesis, derivatization, and metal loading. Macromolecules 38, 8634–8648 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. & Gao C. Graphene in macroscopic order: liquid crystals and wet-spun fibers. Acc. Chem. Res. doi:10.1021/ar4002813 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-14

Coaxial wet-spinning assembly process of GO@CMC fibres.

Coaxial wet-spinning assembly process of CNT@CMC fibres.