Abstract

Introduction

Women are largely unaware that mammography screening can cause overdetection of inconsequential disease, leading to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of breast cancer. Evidence is lacking about how information on overdetection affects women's breast screening decisions and experiences. This study investigates the consequences of providing information about overdetection of breast cancer to women approaching the age of invitation to mammography screening.

Methods and analysis

This is a randomised controlled trial with an embedded longitudinal qualitative substudy. Participants are a community sample of women aged 48–50 in New South Wales, Australia, recruited in 2014. Women are randomly allocated to either quantitative only follow-up (n=904) or additional qualitative follow-up (n=66). Women in each stream are then randomised to receive either the intervention (evidence-based information booklet including overdetection, breast cancer mortality reduction and false positives) or a control information booklet (including mortality reduction and false positives only). The primary outcome is informed choice about breast screening (adequate knowledge, and consistency between attitudes and intentions) assessed via telephone interview at 2 weeks postintervention. Secondary outcomes measured at this time include decision process (decisional conflict and confidence) and psychosocial outcomes (anticipated regret, anxiety, breast cancer worry and perceived risk). Women are further followed up at 6 months, 1 and 2 years to assess self-reported screening behaviour and long-term psychosocial outcomes (decision regret, quality of life). Participants in the qualitative stream undergo additional in-depth interviews at each time point to explore the views and experiences of women who do and do not choose to have screening.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has ethical approval, and results will be published in peer-reviewed journals. This research will help ensure that information about overdetection may be communicated clearly and effectively, using an evidence-based approach, to women considering breast cancer screening.

Trial registration number

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12613001035718.

Keywords: breast neoplasms ,mammography screening; decision making; informed choice

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This longitudinal mixed-methods study includes a randomised controlled trial and a qualitative substudy. Participants are sampled randomly and are making real-life decisions. The intervention rests on strong evidence (updated published model of screening outcomes incorporating local data) including extensive qualitative research. The primary outcome is informed choice, and data are collected by an independent non-profit company.

Our estimates of the effects of screening are drawn from trials conducted overseas and in the past. The intervention may not address the needs of some population groups such as people with low literacy.

Introduction

While mammography screening can reduce breast cancer mortality, it also carries the risk of overdetection (or overdiagnosis). This occurs when screening detects a cancer that would not have presented clinically during the woman's lifetime, meaning she would never have acquired a diagnosis had she not attended screening. Overdetection and the resulting overtreatment are likely to cause harm in terms of emotional well-being,1 physical health in the short term and long term2 and implications for relatives consequently classified as high risk.3 4

The problems of overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer screening5 and the broader health context6 are receiving increasing attention. In the UK, an independent expert panel was commissioned in 2011 to review evidence on important consequences of breast screening, including the challenging task of quantifying the level of overdetection. Wide variations among previous estimates had prompted extensive debate over the appropriateness of different observational methods and their associated biases.7–9 Focusing on randomised trials as the best quality evidence, the panel concluded that invitation to screening leads to overdetection of breast cancer at a rate of 19% during the 20-year screening period.10

Historically, information materials distributed by breast screening programmes worldwide have emphasised benefits and lacked explanation of overdetection.11–14 The appropriateness of explicitly informing people about overdetection has been debated, with reluctance driven by concerns about dissuading women from screening.15 16 However, in the context of a growing international movement towards policies promoting greater involvement of patients and citizens in health decision-making17–20 it has been argued that people offered screening should have the opportunity to make informed decisions about whether to participate.

Making an informed decision about screening requires clear, balanced information on benefits and harms.10 20–23 A new approach to public information was recently adopted in the UK with the aim of better supporting informed choice,24 and the new UK breast screening leaflet released in September 2013 acknowledges overdetection as ‘the main risk of screening’.25 Given the current lack of awareness of overdetection,26–30 such a change to public information is significant and there is a need for high-quality research into its effects. Breast screening is a highly emotive issue, as demonstrated by the public outrage unleashed when the US Preventive Services Task Force changed its recommendations in 2009.31–33 Moves to include overdetection in screening information materials stand to affect large numbers of women around the world. Research is needed to ensure important messages are not misconstrued in ways that adversely affect women's health and well-being.

There is little research on public responses to overdetection. In a focus group study,27 we examined 50 women's understanding of overdiagnosis, screening attitudes and intentions and views on information provision. Participants were previously unaware of overdetection but able to understand it. Although surprised, women valued the information about overdetection. These findings were corroborated by a similar UK study.30 As some women in our study indicated that knowing about overdetection may change their screening or treatment decisions,27 a careful and balanced approach to communication is critical.

The current population-based trial extends our investigation of the impact of overdetection information into a real-life decision-making setting. Using a longitudinal, randomised design incorporating quantitative and qualitative methods, the trial examines the impact of written information about screening outcomes (breast cancer deaths averted and false positives, either including or excluding overdetection) among women close to the target age for entering Australia's screening programme. In addition to examining how the information affects women's decisions, attitudes, psychological responses and well-being in the short term, we will follow participants for 2 years to assess effects on screening participation and to qualitatively investigate the long-term impact of this information in women who do and do not choose to be screened.

Aims

We will examine and evaluate the impact of information about overdetection in breast screening on:

informed choice—measured via knowledge, attitudes and intentions;

decision process (decisional conflict and confidence);

short-term psychosocial outcomes (anxiety, risk perceptions, breast cancer worry, anticipated regret);

screening attendance over 2 years;

experience of screening for those who attend;

long-term psychosocial outcomes (decision regret, quality of life).

Methods and analysis

Study design

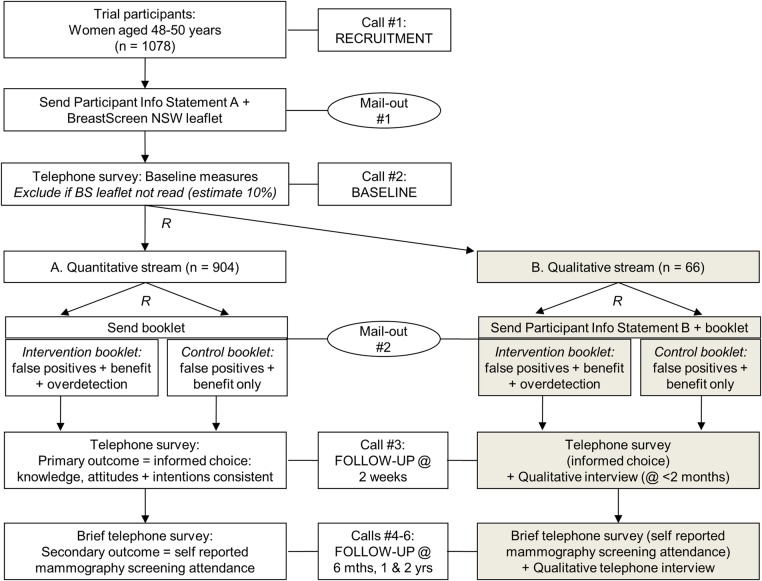

The study uses a randomised trial design with conventional quantitative outcomes plus an embedded longitudinal qualitative substudy (streams A (quantitative) and B (qualitative)—see figure 1). This design ensures we can (1) quantify the impact of overdetection information on women's immediate screening decision-making and (2) assess behaviour and psychosocial outcomes throughout the 2-year follow-up period, allowing us to contextualise experiences and capture changes over time among women who ultimately choose to screen or not screen.

Figure 1.

Design of randomised controlled trial with longitudinal qualitative substudy.

Since it is plausible that the qualitative interviews could influence responses to the quantitative measures (even by simply reminding women of breast screening), we have separated the cohorts entirely so that our quantitative dataset will not include any women who are part of the qualitative component of the research. Both streams will follow the same procedure including all quantitative measures completed via telephone, but women in the qualitative stream will be invited for additional interviews at the time points specified.

Setting and participants

Study participants will be a community sample of women aged 48–50 years from the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW). The government-funded programme, BreastScreen NSW, offers a free biennial screening service and mails a personal invitation to all women when they turn 50 and enter the target age range. The study will therefore involve women who are approaching or at this decision point. This study focuses on women facing an initial decision about whether to screen, as our qualitative study found that women's perceptions of overdetection were influenced by their previous screening participation.27

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Individuals will be eligible if they are women; aged 48–50 years; residing in NSW and sufficiently fluent in English34 to understand study materials and complete telephone interviews.

Exclusion criteria

Individuals will be excluded from the trial if they have a personal history of breast cancer; have had any mammogram within the previous 2 years or are at increased risk of breast cancer compared with the general population, for example due to a strong family history.35 Women at increased risk will be referred to their doctor or the Australian Cancer Council's telephone helpline.

Pilot study

Before the main trial, a pilot study will be carried out with approximately 30 women to test the recruitment and data collection procedures up to the 2-week telephone survey, including checking the suitability of the telephone interview scripts.

Participant recruitment

We will recruit by sampling from a random extract of women in the appropriate age group, drawn from the NSW electoral register. Recruitment will be carried out via telephone by the Hunter Valley Research Foundation (HVRF), an independent non-profit organisation with extensive experience running community surveys and successfully recruiting participants into health research studies.27 36

A database containing names and telephone numbers will be encrypted and sent to HVRF. Trained HVRF interviewers will telephone potential respondents and explain how and why their contact details were obtained. Interviewers will then briefly introduce the study and determine eligibility using a series of simple questions. Eligible women will be informed about what the main study involves and invited to participate. The trial's aims will be described in a general way, as ‘a study to make sure that written information about breast cancer screening is clear and helpful to women’, without specifically referring to overdetection. Consent will be obtained orally and documented by the interviewer.

Preintervention procedure and measures

To achieve a common baseline level of information about screening, immediately after recruitment to the study all women will be sent the BreastScreen NSW programme leaflet, a freely available leaflet that BreastScreen sends to women together with their invitations to attend screening.37 As well as outlining practical aspects of mammography screening, the leaflet describes benefits of early detection while acknowledging the possibility of a false negative (ie, missed cancer) or false positive result (ie, abnormal mammogram when there is no cancer). It does not provide quantitative estimates of the chances of these outcomes, nor does it mention overdetection.

After 1 week HVRF will telephone each participant again, collect demographic information not already recorded, and check that the woman has received the leaflet and had time to read it. If so, the interviewer will collect the following baseline data and then proceed to randomisation:

Stage of decision-making

Women will be asked how far along they are with their decision about screening, using a single item with four response options, as used in previous trials of screening decision aids.38 39

Screening intentions

Women will be asked their intentions about having a screening mammogram within the next 2–3 years, using a single item with five response options (ranging from definitely will not to definitely will).40 41

Screening attitudes

Attitudes towards screening will be measured using a validated, theory-based generic screening attitudes scale comprising six items42 with five response categories ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (scored 1–5).36

Screening knowledge (conceptual)

Women's knowledge of the main concepts of screening will be assessed using items adapted from previous decision aid trials.36 38 39

If the woman has not yet read the leaflet, arrangements will be made to call back at an agreed time. If she has still not read the leaflet by the next contact, she will be excluded from the trial (prior to randomisation). The purpose of only including women who have demonstrated a willingness to read study materials is to maximise the likelihood that the individuals randomised will read their allocated intervention and complete the trial, which is designed to detect any intervention effect under ideal circumstances. This is appropriate for the first randomised trial of consumer information about overdetection in breast screening.

Allocation procedures

Randomisation sequences will be generated by a statistician who has no contact with participants, using permuted blocks with sizes of 4 and 8. Interviewers responsible for recruiting participants will not be aware of the randomisation sequence or allocation and therefore will not know which intervention respondents will receive.

Randomisation to stream A versus B

During the second telephone contact, participants will be randomised to either stream A or receive invitation to the qualitative stream B (described by the telephone interviewer as an ‘enhanced version’ of the study) to achieve the desired sample size in each stream (ie, in an allocation ratio of approximately 13:1). Women who accept the invitation to stream B will be sent plain-language written information about the qualitative substudy together with their allocated booklet. Women who decline the invitation to stream B will be included in stream A.

Randomisation to intervention versus control

Participants within each stream will be allocated to either the intervention or control arm using permuted block randomisation with a 1:1 ratio.

Intervention and control arms

The trial will compare two versions of an evidence-based written information booklet explaining the benefit and harms of biennial mammography screening from age 50, cumulated over 20 years:

Intervention: explanatory information and quantitative estimates of breast cancer mortality benefit, false positives (including total number of women with a false positive, and number having a biopsy) and overdetection; versus

Control: the same explanatory and quantitative information about breast cancer mortality benefit and false positives as in the intervention group but with NO overdetection information.

The booklet was developed for the purposes of this study, and is designed to inform but not to influence women either towards or away from screening. The content and presentation were guided by our focus group findings regarding women's understanding of overdiagnosis, areas of concern or confusion, and views on communication (including a preference for the term overdetection rather than overdiagnosis).27 The booklet was developed with input from layperson collaborators, reviewed by independent clinical and communication experts, and thoroughly piloted for acceptability and comprehension (details of piloting will be published separately).

The quantitative evidence presented is based on an updated version of our published model of screening outcomes43 using effect estimates from a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials,10 adjusted to reflect screening attendance rather than invitation, and applied to current Australian data. The expected frequencies of outcomes are illustrated and contextualised using icon arrays depicting the absolute numbers affected per 1000 women screened over 20 years.44

Table 1 summarises the topics covered in the two versions of the booklet (for additional detail, see online supplementary table). Both are identical in format; the control version was produced directly from the intervention booklet by simply deleting the two pages on overdetection and all other references to it (eg, in Q and A and summary table). The sections on benefit and false positives are identical across versions in terms of content and format.

Table 1.

Summary of contents of intervention and control booklets

| Pg. | Intervention booklet | Pg. | Control booklet |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Front cover: title+image | 1 | Front cover: title+image |

| 2 | Introduction to purpose of booklet | 2 | Introduction to purpose of booklet |

| 3 | Introduction to content of booklet | 3 | Introduction to content of booklet |

| 4 | Mortality benefit: text+diagram | 4 | Mortality benefit: text+diagram |

| 5 | Overdetection: text+diagram | ||

| 6 | Overdetection: conceptual illustration | ||

| 7 | False positive results: text+diagram | 5 | False positive results: text+diagram |

| 8 | Q and A (including breast cancer treatments) | 6 | Q and A (including breast cancer treatments) |

| 9 | Q and A (re overdetection) | ||

| 10 | Summary table+references | 7 | Summary table+references |

| 11 | Glossary; further information sources | 8 | Back cover: glossary; further information sources |

| 12 | Back cover: blank |

Stream A: quantitative study

Methods of data collection and blinding

Trained HVRF interviewers will conduct a telephone survey (15–20 min) to collect postintervention outcome data 2 weeks after randomisation, and will carry out further brief telephone surveys for long-term follow-up at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years postintervention. Table 2 lists the study variables and timing for measurement.

Table 2.

Summary of study variables and timing for measurement

| CALL # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time from baseline | −1 week | BASELINE | 2 weeks | 6 months | 1 year | 2 years |

| Recruitment | x | |||||

| Demographics | x | |||||

| Stage of decision-making | x | |||||

| Screening intentions | x | x | x | |||

| Screening attitudes | x | x | x | x | ||

| Screening knowledge (conceptual) | x | x | x | x | ||

| Screening knowledge (numerical) | x | x | x | |||

| Overdetection knowledge (conceptual) | x | x | x | |||

| Overdetection knowledge (numerical) | x | x | x | |||

| Perceived importance of benefit/harms | x | |||||

| Perceived chances of benefit/harms | x | |||||

| Booklet utilisation/acceptability | x | |||||

| Decision process | x | |||||

| Time perspective | x | |||||

| Anticipated regret | x | x | ||||

| Perceived risk of breast cancer | x | x | x | x | ||

| Breast cancer worry | x | x | x | x | ||

| Anxiety | x | x | x | x | ||

| Screening participation | x | x | x | |||

| Decision regret | x | x | x | |||

| Quality of life | x | x | x |

The HVRF personnel are independent of the research team, and interviews will be conducted within a supervised environment where interviewer performance is regularly monitored to ensure scripts are read as written. All survey questions use standardised wording, and the questions are designed such that the woman's study group allocation is unclear to the interviewer until the final part of the interview.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is informed choice—that is, the extent to which women's screening decisions are consistent with their informed values or attitudes.45 46 Informed choice is assessed by combining measures of knowledge, attitudes and actual choice,47 and has been used successfully in previous decision aid studies.36 38 48 Selection of this primary outcome reflects recent international commitments to informed choice as a key marker of quality in screening programmes.

Informed choice will be assessed at 2 weeks postintervention as a dichotomous outcome, and the intervention and control groups will be compared in terms of the proportion of women making an informed choice. To determine whether each woman makes an informed choice we will separately measure, and then combine, three components: knowledge, attitudes and intentions. An informed choice is one in which knowledge is adequate, with attitudes and intentions being consistent (ie, positive attitudes with positive intentions or negative attitudes with negative intentions). For the purposes of assessing informed choice, the knowledge, attitude and intention measures will be dichotomised using an a priori threshold (see below). The three component variables will also be examined and reported separately to enable more fine-grained understanding of the impact of the intervention on decision-making.

Screening knowledge

We will apply a competency-based approach to assess knowledge49 in line with our published knowledge assessment framework.50 Understanding of conceptual and numerical information provided in the study will be measured using items adapted from our previous decision aid trials.36 38 The items are designed to assess understanding of core screening concepts (including mortality benefit, false positives and overdetection) and awareness of the approximate numbers of women affected by particular outcomes. Total knowledge scores will comprise four subscales: conceptual understanding (of general and overdetection-related information) and numerical understanding (general and overdetection related). As in previous decision aid trials,36 38 39 48 knowledge will be scored using a marking scheme developed a priori. The threshold score to be considered adequate for the purposes of determining informed choice will also be set a priori. Women will have to demonstrate a basic conceptual understanding of overdetection, false positives and the mortality benefit from screening to be considered as having adequate knowledge. Sensitivity analyses will examine the impact of using higher and lower thresholds.

Screening attitudes

As at baseline, screening attitudes will be measured using a validated six-item scale.42 Scores on each item range from 1 (strongly negative) to 5 (strongly positive).36 For the informed choice outcome, the threshold for a positive attitude will be a total score of 24 or above (ie, scores of 4 or 5 on the 5-point response scale for each item). As literature shows that screening attitudes are typically very positive,36 38 39 a sensitivity analysis will explore the impact of using a higher threshold.

Screening intentions

Intentions to participate in screening within the next 2–3 years will be measured as described at baseline.40 41 Scores will be dichotomised on the five-point scale as categories 1–3 (responses definitely will not, will not and unsure) indicating ‘not intending’ to screen and categories 4–5 (will and definitely will) as ‘intending’ to screen.

Secondary outcomes

The following outcomes will be measured at 2 weeks postintervention.

Perceived importance of screening benefit/harms

Purpose-developed items will be used to ask women about their personal perceptions of the importance of specific screening outcomes in their decision-making about screening. Women will be asked how important it is for them to consider the chances of (1) avoiding breast cancer death, (2) being diagnosed and treated for a cancer that is not harmful, and (3) having a false positive. The four response options range from very important to not at all important.

Perceived personal chances of screening benefit/harms

Women will be asked about their perceived personal likelihood of experiencing specific outcomes (as above) if they have screening, compared with an average screened woman,51 using five verbal response categories ranging from much lower to much higher.

Decision process

Decisional conflict and confidence will be assessed using the validated and widely used Decisional Conflict Scale (10-item low literacy version)36 52 and Decision Self-Efficacy Scale.36 53

Time perspective

This will be assessed using the four-item short form of the Consideration of Future Consequences Scale,54 55 with five response categories ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Anticipated regret

Two items from a validated scale will measure anticipated regret about screening (action regret) and about not screening (inaction regret),56 57 with five response categories ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Perceived personal risk of breast cancer

Women will be asked about their perceptions of personal risk for developing breast cancer in their lifetime, in absolute terms57 (using four verbal response categories ranging from no chance to high chance) and relative to an average woman of the same age58 (using five verbal response categories ranging from much lower to much higher).

Breast cancer worry

A validated single item will measure women's level of worry about developing breast cancer, using four verbal response categories ranging from not worried at all to very worried.36 38 59

Anxiety

This will be measured with the six-item short form of the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory.36 56 60

Booklet utilisation and acceptability

Acceptability and utilisation of materials will be assessed by items measuring how women used and evaluated the booklets, as used successfully in previous decision aid trials.39 61

The following secondary outcomes will be measured at longer term follow-up.

Screening participation

Self-reported attendance at breast screening will be assessed via telephone survey at 6 months, 1 and 2 years. Previous research has demonstrated that this is a reliable indicator of actual breast screening behaviour in Australia (91% of women reported a mammogram accurately to within a year of the recorded date).62 Attendance at diagnostic mammograms and other breast tests will also be assessed by self-report at these time points, and any relevant diagnoses will be recorded. At the end of the trial we intend to assess participants’ screening attendance from screening records as well.

Decision regret

At 6 months, 1 and 2 years, the Decision Regret Scale63 will measure women's level of regret regarding their initial decision whether to screen or not. The scale has five items and five response categories ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Quality of life

At each of the long-term follow-up contacts, quality of life will be measured using the Consequences of Screening in Breast Cancer questionnaire, part I.64

Screening knowledge, attitudes, intentions and psychosocial outcomes measured previously

Long-term follow-up contacts will reassess selected outcomes using the same measures as previously (see table 2 for details).

Sample size

The primary analysis will be comparing the two study groups on the proportion of women who make an informed choice, using the χ2 test. We judge an absolute difference of 10–15% to be relevant. Assuming conservatively that one of the group proportions is 50%, in order to achieve 80% power to detect a group difference of 10% with a two-sided significance level of 5%, we require 407 women per arm at the 2-week follow-up. This sample size is sufficient to detect a 10–15% difference in intentions and a mean difference smaller than 0.5 SDs in knowledge, attitudes and psychosocial outcomes (assuming SDs for these scales based on results from our previous trials) which is considered the minimum clinically important difference for psychosocial outcomes.65

On the basis of our previous research using a similar protocol36 and data from HVRF, we anticipate losing 10% of recruited women at the preintervention stage because they do not read initial study materials within the required time frame, and up to a further 10% who cannot be contacted for the 2-week follow-up survey. Therefore to achieve our 2-week follow-up target sample of 814 women in the quantitative stream and 60 in the qualitative stream (see below) we aim to recruit approximately 1078 women into the study.

On the basis of their extensive telephone survey experience, HVRF have estimated a further 20% loss to follow-up at 1 year and an additional 10% at 2 years (total loss to follow-up at 2 years is 30%). The remaining sample should be sufficient to detect a difference of 12% in attendance at 2 years among 285 women per arm (assuming a 30% attrition rate and 47% attendance rate at mammography screening).66

Statistical analysis methods

Analysis will compare the intervention and control groups on an intention to treat basis (ie, all participants, as randomised) and will be carried out blinded to intervention status. We will use the χ2 test to analyse binary outcomes including informed choice, and the two-sample t test for continuous outcomes, with a significance level of 5%. We will use multiple imputation and sensitivity analyses to explore the impact of missing data.

Stream B: qualitative study

We will conduct a longitudinal qualitative evaluation among women randomised to stream B of the trial to explore in depth their responses to information about overdetection—specifically, how they understand the information and integrate it with existing knowledge, and their subsequent intentions and decisions whether to participate in screening. Women will receive an identical protocol to those in the main trial (stream A), including quantitative telephone survey measures. However, we will also carry out face-to-face or telephone interviews among these women over 2 years at time points corresponding with the assessment of self-reported screening behaviour in the main randomised controlled trial (6 months, 1 and 2 years). This will enable us to examine the experience of screening among women who choose to screen with and without exposure to overdetection information (ie, intervention and control groups), to assess whether the information has any positive or negative impact on women's screening experience (eg, the way in which women interpret, cope with and act on their screening results). This will allow a rich and contextualised understanding of women's experiences and decision-making to complement the quantitative data, and will also enable us to examine the experience of women who choose not to screen, including changes in their feelings over time and following the receipt of screening invitations. Based on current participation in BreastScreen we expect between 25% and 50% of the women will choose not to be screened, giving us a meaningful sample of women choosing to screen and not to screen within the qualitative stream.

Methods of data collection

All women will be interviewed either face to face or by telephone, 1–2 months postintervention, by an experienced qualitative interviewer. Subsequent interviews will be conducted by telephone. For participants living outside the greater Sydney area all interviews will be by telephone. Interviews will be audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Sample size

The intended sample size in the qualitative stream is 60 participants, of whom approximately 30 will be randomised to each study arm. This is a well-accepted sample size in qualitative studies using in-depth interviews, sufficient to explore variation in experiences among participants.67 68

Qualitative analysis

The study will take a phenomenological perspective and will use framework analysis,69 a widely used matrix-based method of thematic analysis which has been applied successfully in many published qualitative studies.70 71 This method enables qualitative themes to be compared within individuals (eg, a woman's understanding of overdetection and her psychological response to it) and between individuals (eg, comparing women who choose to screen and those who do not). It is particularly useful when working in a large research team to facilitate transparency and rigour in the analytic process, and interpretation of research findings.

Ethics and dissemination

Consent will be provided over the telephone and documented by the HVRF interviewer. Explaining the study and obtaining consent by telephone will facilitate comprehension and reduce the unnecessary burden entailed in a written consent form. All HVRF telephone interviews are administered through a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) programme. The CATI and quality control processes used by HVRF ensure that interviewers do not skip any statements while providing information to respondents. Immediately after recruitment, women will be sent plain-language written study information to inform them of their right to refuse participation or withdraw consent at any time, including instructions for how to contact the researchers with questions, withdraw from the study or make a complaint.

The results of the trial will be published in appropriate journals, regardless of the outcomes. The trial will be reported in accordance with the CONSORT Statement.72

Registration details

The trial is registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (registration no. ACTRN12613001035718).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Petra Macaskill for her contribution to the study design during the early planning phase, and Jenn Kidd for her contribution to refining the study materials.

Footnotes

Contributors: KMC, JH, LI, AB and JJ developed the original concept of this study. All authors contributed to discussion and revisions to the study design. KMC, AB, JJ, NH, HD and KMG obtained funding. JH drafted the manuscript; all other authors were involved in revision of the manuscript.

Funding: The trial is funded by a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (no. 1062389).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee has approved the study (project no. 2012/1429).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Brodersen J, Siersma VD. Long-term psychosocial consequences of false-positive screening mammography. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:106–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum M. Harms from breast cancer screening outweigh benefits if death caused by treatment is included. BMJ 2013;346:f385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heath I. It is not wrong to say no. BMJ 2009;338:b2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thornton H. Pairing accountability with responsibility: the consequences of screening ‘promotion’. Med Sci Monit 2001;7:531–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:605–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ 2012;344:e3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biesheuvel C, Barratt A, Howard K, et al. Effects of study methods and biases on estimates of invasive breast cancer overdetection with mammography screening: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:1129–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puliti D, Duffy SW, Miccinesi G, et al. Overdiagnosis in mammographic screening for breast cancer in Europe: a literature review. J Med Screen 2012;19(Suppl 1):42–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu D, Perez A. A limited review of over diagnosis methods and long-term effects in breast cancer screening. Oncol Rev 2011;5:143–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet 2012;380:1778–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gummersbach E, Piccoliori G, Zerbe CO, et al. Are women getting relevant information about mammography screening for an informed consent: a critical appraisal of information brochures used for screening invitation in Germany, Italy, Spain and France. Eur J Public Health 2010;20:409–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorgensen KJ, Gotzsche PC. Content of invitations for publicly funded screening mammography. BMJ 2006;332:538–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saalasti-Koskinen U, Makela M, Saarenmaa I, et al. Personal invitations for population-based breast cancer screening. Acad Radiol 2009;16:546–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zapka JG, Geller BM, Bulliard J-L, et al. Print information to inform decisions about mammography screening participation in 16 countries with population-based programs. Patient Educ Couns 2006;63:126–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bekker HL. Decision aids and uptake of screening. BMJ 2010;341:c5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffy SW, Tabar L, Chen TH, et al. What information should be given to women invited for mammographic screening for breast cancer? Women Health 2006;2:829–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.111th United States Congress. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public Law 111–148 2010

- 18.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Australian safety and quality framework for health care. 2010

- 19.UK Department of Health. Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. 2010

- 20.General Medical Council. Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together. 2008

- 21.Barratt A, Trevena L, Davey HM, et al. Use of decision aids to support informed choices about screening. BMJ 2004;329:507–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jepson RG, Hewison J, Thompson AGH, et al. How should we measure informed choice? The case of cancer screening. J Med Ethics 2005;31:192–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McPherson K. Publicity of NHS breast cancer screening programme is unfair. BMJ 2011;342:d791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramirez A, Forbes L; King's Health Partners. Approach to developing information about NHS Cancer Screening Programmes. 2012

- 25.Informed Choice about Cancer Screening. NHS breast screening: helping you decide. 2013

- 26.Collins K, Winslow M, Reed MW, et al. The views of older women towards mammographic screening: a qualitative and quantitative study. Br J Cancer 2010;102:1461–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hersch J, Jansen J, Barratt A, et al. Women's views on overdiagnosis in breast cancer screening: a qualitative study. BMJ 2013;346:f158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA 2004;291:71–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Sox HC, et al. US women's attitudes to false positive mammography results and detection of ductal carcinoma in situ: cross sectional survey. BMJ 2000;320: 1635–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waller J, Douglas E, Whitaker KL, et al. Women's responses to information about overdiagnosis in the UK breast cancer screening programme: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liberals and mammography. The Wall Street Journal 24 Nov 2009

- 32.Eggen D, Stein R. Mammograms and politics: Task force stirs up a tempest. The Washington Post 18 Nov 2009

- 33.Paulos JA. Mammogram math. The New York Times 13 Dec 2009

- 34.Powers BJ, Trinh JV, Bosworth HB. Can this patient read and understand written health information? JAMA 2010;304:76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre. Advice about familial aspects of breast cancer and epithelial ovarian cancer: a guide for health professionals. 2010

- 36.Smith SK, Trevena L, Simpson JM, et al. A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.BreastScreen NSW. Early detection is vital. 2012

- 38.Mathieu E, Barratt A, Davey HM, et al. Informed choice in mammography screening: a randomized trial of a decision aid for 70-year-old women. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2039–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathieu E, Barratt AL, McGeechan K, et al. Helping women make choices about mammography screening: an online randomized trial of a decision aid for 40-year-old women. Patient Educ Couns 2010;81:63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gwyn K, Vernon SW, Conoley PM. Intention to pursue genetic testing for breast cancer among women due for screening mammography. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003;12:96–102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson E, Hewitson P, Brett J, et al. Informed decision making and prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing for prostate cancer: a randomised controlled trial exploring the impact of a brief patient decision aid on men's knowledge, attitudes and intention to be tested. Patient Educ Couns 2006;63:367–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dormandy E, Michie S, Hooper R, et al. Informed choice in antenatal Down syndrome screening: a cluster-randomised trial of combined versus separate visit testing. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barratt A, Howard K, Irwig L, et al. Model of outcomes of screening mammography: information to support informed choices. BMJ 2005;330:936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trevena LJ, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Edwards A, et al. Presenting quantitative information about decision outcomes: a risk communication primer for patient decision aid developers. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elwyn G, O'Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ 2006;333:417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sepucha KR, Borkhoff CM, Lally J, et al. Establishing the effectiveness of patient decision aids: key constructs and measurement instruments. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marteau TM, Dormandy E, Michie S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expect 2001;4:99–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCaffery KJ, Irwig L, Chan SF, et al. HPV testing versus repeat Pap testing for the management of a minor abnormal Pap smear: evaluation of a decision aid to support informed choice. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:473–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, et al. The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach 2010;32:676–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith SK, Barratt A, Trevena L, et al. A theoretical framework for measuring knowledge in screening decision aid trials. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89:330–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Longman T, Turner RM, King M, et al. The effects of communicating uncertainty in quantitative health risk estimates. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89:252–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Connor AM. Decisional Conflict Scale—user manual 1993 [updated 2010]. Decision aid evaluation measures. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval_dcs.html.

- 53.O'Connor AM. Decision Self-Efficacy Scale—user manual 1995 [updated 2002]. Decision aid evaluation measures. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval_self.html.

- 54.von Wagner C, Good A, Smith SG, et al. Responses to procedural information about colorectal cancer screening using faecal occult blood testing: the role of consideration of future consequences. Health Expect 2012;15:176–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitaker KL, Good A, Miles A, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in colorectal cancer screening uptake: does time perspective play a role? Health Psychol 2011;30:702–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sandberg T, Conner M. A mere measurement effect for anticipated regret: impacts on cervical screening attendance. Br J Soc Psychol 2009;48:221–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ziarnowski KL, Brewer NT, Weber B. Present choices, future outcomes: anticipated regret and HPV vaccination. Prev Med 2009;48:411–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lipkus IM, Klein WM, Skinner CS, et al. Breast cancer risk perceptions and breast cancer worry: What predicts what? J Risk Res 2005;8:439–52 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sutton S, Bickler G, Sancho-Aldridge J, et al. Prospective study of predictors of attendance for breast screening in inner London. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994;48:65–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol 1992;31:301–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith SK, Trevena L, Barratt A, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a bowel cancer screening decision aid for adults with lower literacy. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:358–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barratt A, Cockburn J, Smith D, et al. Reliability and validity of women's recall of mammographic screening. Aust NZ J Public Health 2000;24:79–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brehaut JC, O'Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making 2003;23:281–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brodersen J, Thorsen H. Consequences of Screening in Breast Cancer (COS-BC): development of a questionnaire. Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:251–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 2003;41:582–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. BreastScreen Australia monitoring report 2009–2010. Cancer series no. 72. Cat. no. CAN 68 Canberra: AIHW, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dworkin SL. Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Arch Sex Behav 2012;41:1319–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morse JM. Designing qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994:220–35 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ritchie J, Spencer L, O'Connor W. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In: Ritchie J, , Lewis J, eds. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage, 2003:219–62 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith SK, Dixon A, Trevena L, et al. Exploring patient involvement in healthcare decision making across different education and functional health literacy groups. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:1805–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Waller J, McCaffery K, Kitchener H, et al. Women's experiences of repeated HPV testing in the context of cervical cancer screening: a qualitative study. Psychooncology 2007;16:196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.