Abstract

The importance of plant small heat shock proteins (sHsp) in multiple cellular processes has been evidenced by their unusual abundance and diversity; however, little is known about their biological role. Here, we characterized the in vitro chaperone activity and subcellular localization of nodulin 22 of Phaseolus vulgaris (PvNod22; common bean) and explored its cellular function through a virus-induced gene silencing–based reverse genetics approach. We established that PvNod22 facilitated the refolding of a model substrate in vitro, suggesting that it acts as a molecular chaperone in the cell. Through microscopy analyses of PvNod22, we determined its localization in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Furthermore, we found that silencing of PvNod22 resulted in necrotic lesions in the aerial organs of P. vulgaris plants cultivated under optimal conditions and that downregulation of PvNod22 activated the ER-unfolded protein response (UPR) and cell death. We also established that PvNod22 expression in wild-type bean plants was modulated by abiotic stress but not by chemicals that trigger the UPR, indicating PvNod22 is not under UPR control. Our results suggest that the ability of PvNod22 to suppress protein aggregation contributes to the maintenance of ER homeostasis, thus preventing the induction of cell death via UPR in response to oxidative stress during plant-microbe interactions.

The small heat-shock protein (sHsp) family is one of six major families of heat-shock proteins, an important group of molecular chaperones ubiquitously produced by eukaryotes that is activated in response to harsh environmental conditions and certain developmental processes (DeRocher et al. 1991; Sun et al. 2002; Waters et al. 2008). In plants, sHsp are encoded by nuclear genes and are classified into seven classes. sHsp classes I to III are localized in the cytosol or nucleus, and the remaining classes occur in plastids, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria, and peroxisomes (Siddique et al. 2008). While sHsp are extremely diverse in amino acid sequence and size, most share structural and functional properties, such as small molecular mass (15 to 42 kDa), the ability to form large oligomers from multiple subunits, and chaperone activity in suppressing the nonspecific aggregation of nascent and stress-denatured proteins (Haslbeck et al. 2005). It has been hypothesized that the great variability of plant sHsp in terms of sequence, oligomeric organization, and cellular localization is related to functional diversity as well as substrate selectivity (Haslbeck et al. 2005; Waters 1995). However, studies of in vivo biological functions of sHsp have been hampered by functional redundancy and the lack of phenotypes of knockout mutants, and so, the identity of cellular sHsp substrates and, thus, their biological role remains poorly defined.

Proteins must fold into specific three-dimensional shapes to function properly. For many proteins, this fundamental process is assisted by molecular chaperones. By assisting in the folding of newly synthesized peptides, the refolding of denatured proteins, or both, molecular chaperones prevent protein aggregation. Folding of proteins that are destined to be secreted or membrane-bound or both within the secretory pathway takes place in the ER, a key organelle in which proteins are synthesized, properly folded, and glycosylated. This process is continuously evaluated by molecular chaperones that not only assist client polypeptides in folding but also monitor their conformational state and by unique enzymes that maintain an oxidizing environment and catalyze co- and post-translational modifications (Ellgaard and Helenius 2003; Gupta and Tuteja 2011). Whereas properly folded proteins traffic from the ER through the secretory pathway to be distributed to their final destination inside or outside the cell, unfolded proteins retained in the ER are destroyed by an ER-associated degradation system in the cytosol (Shruthi and Jeffrey 2008).

Several physiological or adverse environmental conditions may increase the influx of unfolded polypeptides, exceeding the folding capacity of the ER (Liu and Howell 2010; Urade 2007). The accumulation of incorrectly folded proteins triggers signaling pathways that modulate the capacity and quality of the polypeptide-folding process and minimizes the cytotoxic impact of malformed proteins. These signaling pathways are collectively termed the unfolded protein response (UPR).

The UPR in plants triggers protective cellular responses, such as the upregulation of ER chaperones, degradation of misfolded proteins, and activation of brassinosteroid signaling (Che et al. 2010; Martínez and Chrispeels 2003; Su et al. 2011), events that correlate with the adaptation of plants to stress (Leborgne-Castel et al. 1999; Koizumi et al. 1999; Valente et al. 2009). However, if protein aggregation is not amended or if the stress persists, the ER can switch the cytoprotective functions of the UPR to cell death–promoting mechanisms (Alves et al. 2011; Faria et al. 2011; Iwata and Koizumi 2005).

Nodulin 22 (PvNod22) cDNA was isolated from a Phaseolus vulgaris L. (common bean) cDNA library derived from Rhizobium-infected roots (Mohammad et al. 2004). PvNod22 encodes a protein with C-terminal homology to the alpha-crystallin domain found in sHsp. At the time, we demonstrated that its overexpression in Escherichia coli conferred cell protection against oxidative stress (Mohammad et al. 2004), suggesting its role in plant host protection from oxidative toxicity during the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. In the present study, we characterized the in vitro chaperone activity and subcellular localization of PvNod22. Specific downregulation of PvNod22 induced necrotic lesions in the aerial parts of common bean plants cultivated under optimal growth conditions, a phenotype that correlates with the induction of UPR- and cell death–related genes. In planta, PvNod22 expression was modulated by oxidative stress but not by chemicals that trigger UPR, indicating PvNod22 is not under UPR control. Collectively, our data suggest that the ability of PvNod22 to suppress the aggregation of proteins may contribute to the maintenance of ER homeostasis.

RESULTS

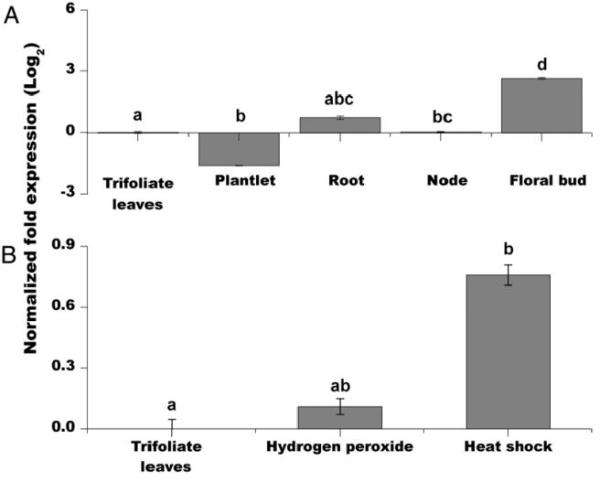

PvNod22 is a ubiquitous sHsp induced by stress

Plant sHsp are encoded by a large and diverse gene family. Although many of these proteins are constitutively expressed, the majority is induced during development or in response to stress (Sun et al. 2002; Waters et al. 2008). To characterize PvNod22 expression in bean, we first analyzed PvNod22 transcript abundance in fully developed flowering plants by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using specific primers (PvNod22int./ext. in Supplementary Table 1). Compared with trifoliate leaves, PvNod22 levels were relatively low in all analyzed tissues, with the exception of floral buds (Fig. 1A). Glycine max (soybean) and Arabidopsis thaliana genes with high levels of sequence similarity to PvNod22 (Glyma20g28540 and At3g22530, respectively) displayed similar expression patterns (The Bio-Analytic Resource for Plant Biology [BAR] database; Winter et al. 2007).

Fig. 1.

Expression profile of PvNod22 in bean plants. A, Relative expression levels of PvNod22 in diverse plant tissues of mature plants cultivated in optimal conditions by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using specific primers. First strand cDNA was synthesized and used as template for qPCR amplification. PvNod22 expression levels were normalized against Ef1-α (elongation factor 1-α). The fold change in expression was obtained by comparing the expression ratio of PvNod22 in trifoliate leaves from mature plants versus its expression in all other tissues. P < 0.001, analysis of variance (ANOVA). B, A similar analysis was carried out using 3-week-old stressed Phaseolus vulgaris plants. Bean plants were sprayed with 1 mM hydrogen peroxide or subjected to 4°C (heat shock) for 30 min. After normalization against Ef1-α, the fold change in expression was obtained by calculating the expression ratio of PvNod22 in trifoliate leaves from control plants versus its expression in stressed plants. P < 0.02, ANOVA. Values in both graphs represent the mean and standard deviation of two biological samples with three technical replicates each. In both graphs, letters represent significantly different means compared with empty vector–treated bean plants, according to Tukey’s multiple comparison test (P < 0.01).

At3g22530 is induced by low temperature and salinity, but also by compatible biotic interactions (BAR and Genevestigator databases; Hruz et al. 2008; Winter et al. 2007). Since the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is a common feature in biotic and abiotic plant stress responses (Fujita et al. 2006), we decided to establish whether the expression of PvNod22 is induced under oxidative conditions in the foliage of 3-week-old P. vulgaris plants. Compared with untreated plants, PvNod22 accumulates in response to oxidative stress and heat shock (Fig. 1B). Collectively, expression profile of PvNod22 and its homologous genes in A. thaliana and G. max suggest their participation in a general pathway for stress resistance.

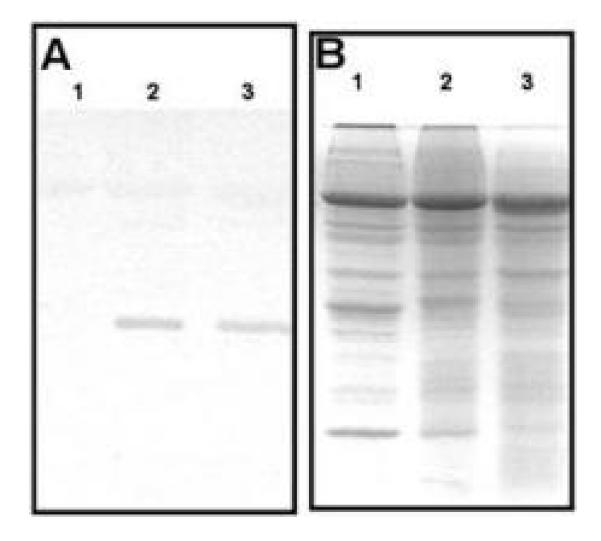

PvNod22 facilitates in vitro refolding of a denatured model substrate

It is well-documented that sHsp, while not themselves able to refold nonnative proteins, can effectively protect other proteins from heat-induced inactivation by forming a complex with the denatured substrate (Haslbeck et al. 2005). To determine the chaperone activity of PvNod22, a purified 6xHis-tagged version of PvNod22 (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 6) was used in a luciferase refolding assay (Fig. 2B). Firefly luciferase (Luc) is a 61-kDa protein frequently used to evaluate chaperone activity in in vitro assays. Luc (1 μM) was heat-denatured for 20 min at 42°C with or without PvNod22 (1 μM or 3 μM), then shifted to 30°C, and mixed with 30 μl of nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate. To rule out minor contaminants in the purified recombinant PvNod22 protein could act as a sHsp, 3 μM 6xHis-tagged green fluorescent protein (GFP), purified from E. coli in a similar manner to PvNod22, was included in the assay as a negative control. We also used 3 μM of superoxide dismutase (SOD) as a nonchaperone control. Samples were supplemented with 0.5 mg/ml of freshly prepared bovine serum albumin solution to prevent Luc adsorption to tubes. As shown in Figure 2B, the activity of native Luc remained stable at 30°C throughout the study, while a 20-min preincubation at 42°C induced a dramatic decrease in its enzymatic activity, with a slight recovery at the end of the assay (90 min, 33% ± 0.52%), probably due to the endogenous chaperone activity of the reticulocyte lysate (Lee and Vierling 2000). When PvNod22 was added (Fig. 2B), Luc activity recovered. After a 90-min incubation, a 60% ± 0.75% recovery was achieved in the presence of 1 μM of PvNod22, whereas a recovery of up to 86% was reached in the presence of 3 μM of PvNod22. Neither 6xHis-tagged GFP nor SOD showed Luc refolding activity. Therefore, PvNod22, similar to other plant sHsp (Siddique et al. 2008), enhances the recovery of substrate activity in the presence of other chaperones.

Fig. 2.

Purified PvNod22 displays chaperone activity. A, The fusion protein was purified by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA agarose resin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.) as affinity matrix and was checked on a 13.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel, followed by immunoblot analysis using rabbit anti-PvNod22 antiserum. Lanes 1 and 4, crude protein extract from Escherichia coli XL1-Blue transformed with pQE30-PvNod22 plasmid; lanes 2 and 5, PvNod22 inclusion bodies in 8 M urea; and lanes 3 and 6, purified 6xHis-tagged PvNod22. B, PvNod22 facilitates luciferase refolding. Firefly luciferase (Luc, 50 nM) was denatured at 42°C and were allowed to refold in the presence of 1 or 3 μM of PvNod22. Registered activity of native (■) or denatured (○) Luc; 3 μM of 6xHis-tagged GFP (◇) or superoxide dismutase (×) as negative control assays. Luc reactivation was observed in the presence of either 1 (△) or 3 μM (▽) of PvNod22. The Luc activity of the unheated sample at the onset of the experiment was defined as 100% (set to 1 in the graph). Normalized data were plotted as the mean and standard deviation of three independent experiments. RLU = relative light units.

PvNod22 is localized in the ER in living cells

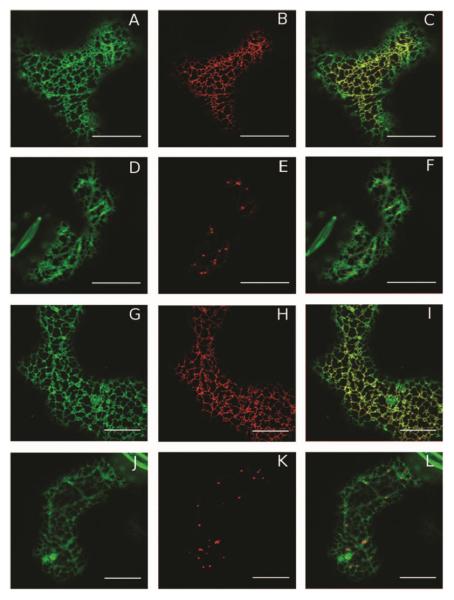

Hydropathy analysis of PvNod22 revealed a highly hydrophobic N-terminal sequence with a putative cleavage site for a signal peptide (SP) (Mohammad et al. 2004). Furthermore, in silico studies of the subcellular localization of PvNod22 using two independent algorithms (Predotar and TargetP servers) suggested that PvNod22 is targeted to the ER. To determine PvNod22 localization within the plant cell, we transiently coexpressed PvNod22 SP (1 to 25 aa)–GFP-PvNod22 (26 to 197 aa) or PvNod22-GFP with ERyk (an ER luminal marker) (Nelson et al. 2007) or AtERD2-YFP (a Golgi marker) (Brandizzi et al. 2002a, b and c) in tobacco epidermal cells (Nicotiana tabacum SR1 cv. Petit Havana) and analyzed the cells by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Fig. 3). The finding that both GFPPvNod22 and PvNod22-GFP exhibited a reticular fluorescence pattern that largely overlapped with ERyk signal (Fig. 3C and I, respectively) strongly suggests that PvNod22 is an ER protein.

Fig. 3.

PvNod22 is a resident chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Epithelial cells from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum SR1 cv. Petit Havana) leaves were infiltrated with Agrobacterium sp. strain GV3101 cultures cotransformed with SP-GFP-PvNod22, or PvNod22-GFP and ERyk (an ER luminal marker), or AtERD2-YFP (a Golgi marker). After 3 days, the subcellular localization of each fluorescent protein was analyzed by confocal microscopy. A and D, SPGFP-PvNod22 or G and J, PvNod22-GFP fluorescence and B and H, the pattern of ERyk and E and K, AtERD2-YFP distribution are shown. Merged images of C, SP-GFP-PvNod22 with ERyk and F, AtERD2-YFP or I, PvNod22-GFP with ERyk or L, AtERD2-YFP are also shown. PvNod22 preferentially co-localized with the ER marker. Bar length = 20 μm.

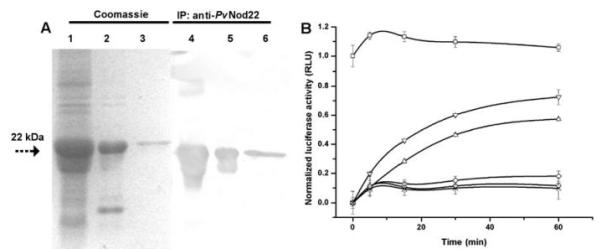

Silencing PvNod22 expression in common bean plants

The Bean pod mottle virus (BPMV)-based virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) vector previously described for applications in soybean and bean (Diaz-Camino et al. 2011; Fu et al. 2009; Zhang and Ghabrial 2006) was used to silence the expression of PvNod22 in bean plants. Since VIGS is a process of sequence-specific gene silencing, we decided to evaluate the expression level of PvNod22 as well as of other related sHsp in both vector and VIGS:PvNod22 bean plants by reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR. Searching the P. vulgaris genome (Phytozome portal; Goodstein et al. 2012) revealed 46 open reading frames (ORF) that encoded proteins related to sHsp (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Table 2). A phylogenetic study revealed that PvNod22 is grouped in a different clade with other bean sHsp localized in the cytosol, mitochondria, or chloroplast (Fig. 4A, shaded area, and B, enlargement of this area). In systemic leaves derived from PvNod22-silenced plants, PvNod22 mRNA levels were effectively reduced compared with plants treated with the empty vector alone (Fig. 4C). The expression of all other transcripts encoding sHsp included in this study did not change under the conditions tested (Fig. 4C), confirming the on-target specificity of our VIGS construct to specifically silence the expression of PvNod22 in bean. We also evaluated the expression of this group of bean sHsp under heat shock, a general condition that induces the expression of sHsp in eukaryotes (Fig. 4D). As expected, in addition to PvNod22, many, but not all, sHsp included in this clade were activated by heat in untreated plants.

Fig. 4.

Specificity of the VIGS:PvNod22 silencing construct on the expression of PvNod22 and other bean small heat shock proteins (sHsp). A, Phylogenetic relationship between PvNod22 and other Phaseolus vulgaris sHsp. The figure was created by Muscle alignment and is based on full-length amino acid sequences. The sHsp lbpA from Escherichia coli is included as outgroup in this analysis. Colored circles represent putative subcellular localization; in green, chloroplast; in yellow, cytoplasm; in red, mitochondria; in blue, peroxisome; in black, endoplasmic reticulum; and in gray, endomembrane system. B, Amplification of the clade that includes PvNod22 (shaded area in A). C, Relative expression levels of sHsp encoding genes in trifoliate leaves of PvNod22-silenced plants 3 weeks after infection compared with vector-treated plants of the same age. Plotted data represent the sHsp expression ratio between vector- and VIGS: PvNod22-treated bean plants. PvNod22, P < 0.015; Student’s test. D, Relative expression levels of these sHsp in trifoliate leaves of vector-treated plants after heat shock. In all cases, expression levels were normalized against Ef1-α values. Plotted data represent the sHsp expression ratio between heat-treated and untreated empty vector–infected bean plants. P < 0.015; Student’s test. Data and standard deviation values in both quantitative polymerase chain reaction experiments were obtained from two biological samples with three technical replicates each.

Silencing of PvNod22 in common bean plants leads to striking phenotypes and strongly affects plant performance

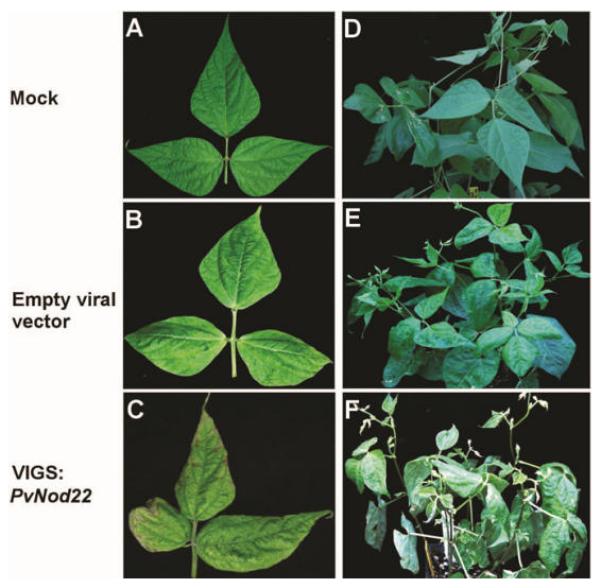

In common bean plants, inoculation with the BPMV-based VIGS vector was characterized by mild chlorotic mottling and rugosity of the foliage (Fig. 5A with B). Three weeks after infection, the yellowish mottling caused by viral infection seemed to be accentuated, and the foliage showed severe blistering and extended necrotic lesions in the PvNod22-silenced (VIGS:PvNod22) plants (Fig. 5B and C) (Diaz-Camino et al. 2011). The absence of PvNod22 profoundly affected plant performance, as observed at the time of flowering (Table 1). Compared with mock- or vector-inoculated plants, total height and plant biomass were dramatically reduced in fully-developed VIGS:PvNod22-inoculated flowering plants, showing an important delay in plant growth. Although we did not find significant differences in plant morphology (Table 1, shoot/root ratio values), the number of pods per plant and seeds per pod was drastically reduced in PvNod22-silenced bean plants.

Fig. 5.

Silencing of PvNod22 in common bean plants induces the development of necrotic lesions. Experimental sets of A and D, mock-, B and E, vector- and C and F, VIGS:PvNod22-inoculated bean plants were generated as described (Díaz-Camino et al. 2011). Inoculation with the mottle virus empty vector was characterized by mild chlorotic mottling and rugosity of the foliage (A and B), whereas PvNod22-silenced (VIGS: PvNod22) plants resulted in the incipient development of necrotic lesions (C). Three weeks after infection, the yellowish mottling caused by viral infection seemed to be accentuated (E compared with F), the foliage showed severe blistering, and the necrotic damage was extended in the PvNod22-silenced plants.

Table 1.

Morphology of mock-, viral vector–, or VIGS:PvNod22-inoculated fully developed flowering plants. n = 10 per treatment.

| Plant treatment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Mock | Viral vector | VIGS:PvNod22 |

| Height (cm) | 112.5 ± 14.31 | 91.5 ± 12.79 | 33.5 ± 9.30 |

| Nodes per plant | 5.0 ± 1.02 | 5.1 ± 0.92 | 3.0 ± 2.01 |

| Shoot/root ratio | 1.4 ± 0.15 | 1.4 ± 0.30 | 2.1 ± 0.50 |

| Biomass (g) | 30.0 ± 3.50 | 22.9 ± 2.70 | 6.3 ± 3.53 |

| Pods per plant | 12.0 ± 2.00 | 12.0 ± 4.10 | 3.01.02 |

| Seeds per pod | 4.0 ± 0.71 | 3.6 ± 1.14 | 1.7 ± 0.60 |

| Seed weight (g) | 0.3 ± 0.10 | 0.3 ± 1.14 | 0.3 ± 0.04 |

The reduced yield associated with extensive mottling and blistering of the foliage could correlate with an enhanced BPMV accumulation in Phaseolus spp., similar to what has been seen when BPMV infects diverse soybean cultivars (Zheng et al. 2005). Since these features are more severe in PvNod22-silenced bean plants, we compared BPMV-coat protein (CP) accumulation by immunoblot analysis in 3-week-old trifoliate leaves of vector- (Fig. 6A and B, lane 2) and VIGS:PvNod22-silenced plants (Fig. 6A and B, lane 3). Compared with vector, VIGS:PvNod22 plants did not contain higher levels of BPMV. Thus, the striking phenotype observed in the PvNod22-silenced plants is not related to an enhanced accumulation of BPMV, suggesting that a fundamental pathway controlling plant performance had been severely compromised.

Fig. 6.

PvNod22-silenced bean plants do not accumulate more mottle virus (BPMV) than empty vector–infected plants. A, Immunoblot analysis showing levels of the large (42 kDa) coat protein of BPMV in 15 μg of total leaf protein extracts obtained from 3-week-old mock- (lane 1), vector- (lane 2), and VIGS:PvNod22-inoculated (lane 3) plants. B, Protein-loading control; Coomassie blue staining.

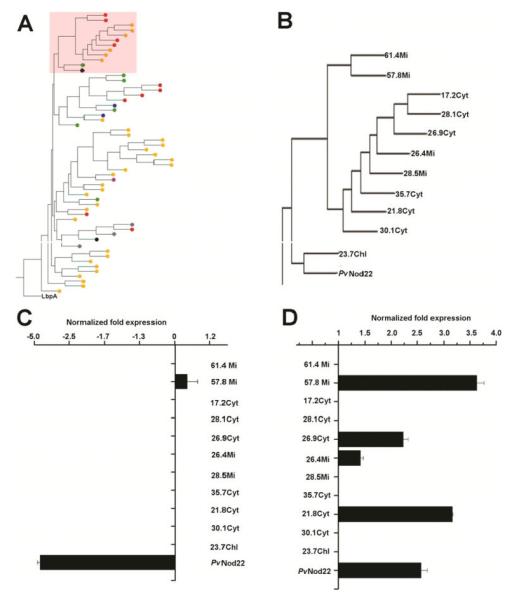

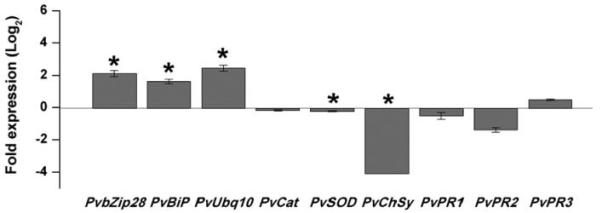

Silencing of PvNod22 in bean plants induces UPR

We next evaluated the effect of silencing PvNod22 in bean plants at the molecular level. Prompted by the phenotype observed in VIGS:PvNod22 bean plants (Fig. 5) and the evidence provided above that PvNod22 may function as an ER resident, we decided to determine the expression level of key bean genes involved in plant defense, such as those encoding genes for the UPR proteins (PvbZip28, PvBiP1/2, P. vulgaris polyubiquitin-10 (PvUbq10]), pathogen-activated proteins (P. vulgaris pathogenesis-related genes 1, 2, and 3 [PvPR1, PvPR2, and PvPR3, respectively]), and ROS detoxifying enzymes (P. vulgaris catalase [PvCat], P. vulgaris iron superoxide dismutase [PvSOD], and P. vulgaris chalcone synthase [PvChSy]) in plants infected either with the empty viral vector or with the recombinant VIGS:PvNod22 vector. From all evaluated genes, only the expression of UPR genes was significantly up-regulated in VIGS:PvNod22 bean plants (Fig. 7, PvbZip28, PvBiP1/2, PvUbq10), suggesting that a strong reduction in the amount of PvNod22 may correlate with an activation of the UPR. Additionally, the expression pattern of ROS detoxifying enzymes (PvSOD and PvChSy) were repressed in VIGS:PvNod22-infected plants compared with the vector-treated plants, suggesting that UPR was activated by the downregulation of PvNod22 in bean plants, possibly via ROS.

Fig. 7.

Silencing of PvNod22 induces unfolded protein response (UPR) in common bean. Relative expression levels of key bean genes involved in UPR (PvbZip28, PvBiP1/2, PvUbq10), genes encoding reactive oxygen species detoxifying enzymes (PvCat, PvSOD, PvChSy), and pathogenesis-related genes (PvPR1, PvPR2, PvPR3) were determined in 3-week-old empty vector and VIGS:PvNod22 plants by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Total RNA was isolated from each biological sample. First strand cDNA was synthesized and subjected to qPCR. Expression levels were normalized against Ef1-values. Ratios of expression in empty vector to VIGS:PvNod22 plants are graphed. Asterisks represent significantly different means according to statistical analysis (P < 0.05). These values represent the mean and standard deviation of two biological samples with three technical replicates each.

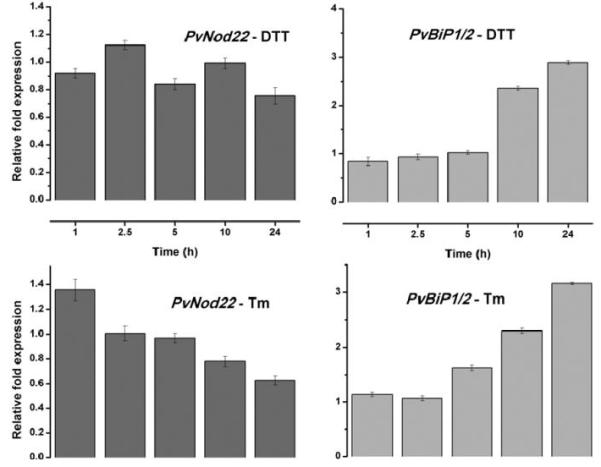

PvNod22 expression is not induced by UPR-inducing chemical agents

To determine if PvNod22 is involved in plant UPR, we induced this process in common bean plants using tunicamycin (Tm) (an inhibitor of N-linked glycosylation) or dithiothreitol (DTT, a reducing agent that interferes with Cys bridge formation and, thus, the proper folding of ER proteins). Two-day-old bean seedlings were incubated for different periods of time in plant growth medium supplemented with 10 μg of Tm per milliliter or 10 mM DTT. Later, the expression of PvNod22 and PvBiP1/2 was analyzed by qPCR (Fig. 8). As previously reported in A. thaliana (Martínez and Chrispeels, 2003), the expression of PvBiP1/2 was induced by both treatments (PvBiP1/2-DTT or Tm) (Fig. 8,). However, PvNod22 expression was just modestly induced after 1 h of exposure to Tm, followed by a clear decrease in its expression (Fig. 8). DTT, on the other hand, had no clear effect on PvNod22 expression (Fig. 8). In light of these findings, we conclude that PvNod22 is not under UPR control.

Fig. 8.

PvNod22 expression is not induced by unfolded protein response (UPR)–inducing chemicals in bean plants. Relative expression levels of PvBiP1/2, a key protein involved in UPR, and PvNod22 were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in 2-day-old bean seedlings treated with 10 μg of tunicamycin (Tm) per milliliter or 10 mM dithiotreitol (DTT). Total RNA was isolated from each biological sample at the indicated time points. First-strand cDNA was synthesized and was subjected to qPCR. Expression levels were normalized against Ef1-α values. PvNod22, P = 0.69, not a significant change in expression. Values represent the mean and standard deviation of duplicate experiments.

DISCUSSION

Newly synthesized and preexisting proteins are at constant risk of misfolding and aggregation. To avoid these possibilities, cells have evolved a robust network of molecular chaperones that counteract protein damage in a compartment-specific manner. sHsp, together with other molecular chaperones, participate in the preservation of protein functions by suppressing their nonspecific aggregation (Haslbeck et al. 2005). Although it has been proposed that the high variability of plant sHsp is related to their functional role (Haslbeck et al. 2005; Waters 1995), there are few published studies actually supporting their biological function.

In this work, we demonstrated that PvNod22, as other sHsp plant chaperones, could be part of the protein refolding machinery of the cell (Fig. 2). PvNod22 is sequence-related to AtAcd22.1, the gene product of At3g22530 (Kaneko et al. 2000), and Glyma20g28540 in soybean. Similarly to PvNod22 (Fig. 1), At3g22530 is ubiquitously expressed in planta but is induced by oxidative stress (BAR database; Winter et al. 2007), suggesting that these related sHsp might be important in counteracting stressful environmental conditions, including the avoidance of microbial invaders (Dong 1998).

PvNod22 co-localizes with ERyk (Nelson et al. 2007) in transiently transformed epidermal cells of Nicotiana tabacum (Fig. 3C and I). PvNod22 does not possess an ER retention signal, but it could be retained in the ER by assembly with other peptides that have the HDEL/KDEL retention signal, such as A. thaliana SDF2 (Nekrasov et al. 2009). Although some ER-located sHsp in plants have been identified and it has been anticipated that these proteins function as molecular chaperones that stabilize denatured proteins during stress conditions (Berkel et al. 1994; Helm et al. 1995; Ukaji et al. 1999; Zhao et al. 2007), beyond their expression pattern, almost nothing is known about their in vivo functions.

Plants in which PvNod22 was silenced by VIGS were characterized by distortions in leaf morphology, the development of local necrosis (Fig. 5), and diminished plant performance (Table 1). An analogous phenotype has been observed in soybean plants infected with BPMV, and symptom severity of this virus has correlated with virus accumulation (Gu and Ghabrial 2005). We initially predicted a similar outcome in VIGS: PvNod22 common bean plants. However, the finding that the phenotypic changes observed in the PvNod22-silenced plants are not related to an increase in BPMV accumulation (Fig. 6), suggests that absence of PvNod22 could alter host plant response to a virus pathogen.

Several lines of evidence indicate that UPR in plants, as in mammals, is linked to cell death and stress resistance through shared components (Alvim et al. 2001; Cacas 2010; Fujita et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2011; Valente et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2005). Given that PvNod22 resides in the ER and that its absence results in diverse deleterious effects (Figs. 3, 4, and 5; Table 1), we evaluated the effect of silencing PvNod22 on the expression pattern of key genes involved in UPR and plant defense. UPR marker genes are induced in VIGS:PvNod22 bean plants (Fig. 7), indicating that the absence of PvNod22 is sufficient to induce UPR. In addition, genes involved in ROS detoxification, such as PvSOD and PvChSy, are repressed (Fig. 7), suggesting the existence of a link between the UPR and redox components in plants. Even though there are no obvious PERK homologs in Arabidopsis, other mediators, such as AGB1, are known to be involved in oxidative stress responses (Joo et al. 2005; Wei et al., 2008).

A sustained UPR driven by the absence of PvNod22 could result in extended necrosis, observed in VIGS:PvNod22 plants (Fig. 5), as well as in plant growth inhibition (Table 1) (Alves et al. 2011; Faria et al. 2011; Iwata and Koizumi 2005; Liu et al. 2007, 2011). We measured the relative amounts of cell death in leaf discs obtained from mock- or vector-inoculated or PvNod22-silenced bean plants by means of conductivity at different times. VIGS:PvNod22 bean plants showed a higher ion leakage level compared with other conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1A), suggesting that the loss of PvNod22 leads to cell death. In addition, compared with mock- or vector-inoculated leaf discs, the expression level of two cell death–related genes, PvBaxI-1 (Bax inhibitor-1) and PvLSD1 (lesion simulated disease-1), was repressed. BaxI-1 functions as an anti–cell death protein in plants and is able to suppress stress factor–mediated cell death (Watanabe and Lamb 2008), whereas LSD1 monitors a superoxide-dependent signal and negatively regulates a plant cell-death pathway (Dietrich et al. 1994). Accordingly, diminished gene expression of BaxI-1 and LSD1 in VIGS: PvNod22 plants correlated to the necrotic phenotype associated with this condition.

PvNod22 is an ER-resident sHsp associated with UPR and cell death in common bean plants, whose expression is activated under oxidative stress, a common feature of symbiotic or pathogenic plant interactions. PvNod22 overexpression in E. coli cells was able to suppress cell death mediated by hydrogen peroxide (Mohammad et al. 2004) due to its refolding of a denatured protein activity and, thus, in preventing protein precipitation (Fig. 2B). Even though PvNod22 may be induced in the whole plant in response to stressful conditions, the gene transcript of this unique sHsp accumulates from early to late stages of nodule organogenesis, specifically at the infected host cells of nitrogen-fixing symbiotic nodules (Mohammad et al. 2004). Interestingly, high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been observed in infected cells of functioning nodules (Chang et al. 2009). Unleashed ROS accumulation may lead to protein misfolding; consequently, the UPR is activated to restore ER homeostasis.

Although we did not provide a mechanistic connection between PvNod22 in the ER and the UPR, in this work, we demonstrate that PvNod22 has a nonredundant function in the ER of common bean, a function that, when impaired, leads to cell death. In light of our findings, we propose that PvNod22 is involved in maintaining the balance between cell survival and cell death by preventing protein aggregation in the ER upon exposure to biotic and abiotic stresses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant growth conditions

Surface-sterilized seeds of Nicotiana tabacum SR1 (cv. Petit Havana, tobacco) were incubated at 4°C for 24 h in Murashige and Skoog medium (Gibco BRL, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.) and were then transferred to small pots (18 × 18 cm) containing Metro Mix 360 soil. Plants were grown for 6 weeks at 25°C in a 16-h-light and 8-h-dark cycle. Surface-sterilized seeds of P. vulgaris cv. Black Valentine were cultivated in medium pots (35 cm diameter) containing Metro Mix 360 soil, in the greenhouse with day and night temperatures of 28 and 25°C, respectively. N. tabacum and P. vulgaris plants were watered daily with B and D nutrient solution (Broughton and Dilworth 1971). Basal thermotolerance treatment consisted of heating 3-week-old bean plants to 45°C for 30 min, whereas oxidative stress was induced by spraying the foliage once with a 1-mM solution of hydrogen peroxide. Trifoliate leaves were collected 3 h after treatment, were frozen in liquid nitrogen, and were stored at −80°C. For chemical induction of the UPR, 2-day-old bean seedlings were incubated in B and D nutrient solution for 24 h and were then incubated in B and D nutrient solution supplemented with 10 μg of tunicamycin per milliliter or 10 mM DTT (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis). Radicles were collected 0, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, and 24 h after treatment, were frozen in liquid nitrogen, and were stored at −80°C.

Expression and purification of recombinant PvNod22

E. coli XL1-Blue cells transformed with pQE30-PvNod22 (Mohammad et al. 2004) were grown in Luria Bertani broth (Gibco BRL) medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin per milliliter at 37°C until adsorbance at 600 nm reached 0.3. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl 1-thio-d-galactopyranoside (Fermentas AB, Vilnius, Lithuania), followed by further incubation for 4 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, were resuspended in solution A (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Tween 20, 1 mM aminocaproic acid, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) supplemented with 100 mg of lysozyme per milliliter (Sigma-Aldrich), and were incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Cell lysate was centrifuged (30 min at 10,000 × g), washed twice with solution A, and sonicated (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 4). Inclusion bodies were concentrated by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min and were dissolved in 4 M urea in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 5). The supernatant was incubated in batches for 1 h at room temperature with 25 ml of Ni-NTA agarose (Invitrogen) previously equilibrated with 4 M urea in PBS. Lysate-coupled resin was washed with five volumes of PBS 4 M urea, followed by 5 volumes of solution B (500 mM NaCl, 60 mM imidazole in 4 M urea in PBS). Unfolded recombinant 6xHis-tagged PvNod22 was eluted from the column with 4 M urea and 250 mM imidazole in PBS and was dialyzed against refolding buffer (2 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA in PBS) containing decreasing concentrations of urea (2, 1, or 0 M). Dialysis was performed for 8 h at each urea level. The final preparation (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 6) was centrifuged for 20 min at 20,400 × g and was concentrated to approximately 20 mg of protein per milliliter. Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 10% (vol/vol), and aliquots were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and were stored at −80°C.

Luciferase refolding assay in reticulocyte lysate

Luc (1 μM) (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) was heat-denatured for 20 min at 42°C in 25 mM HEPES/KOH (pH 7), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM DTT in the presence of 6xHis-tagged GFP (3 μM), SOD (EC number 1.15.1.1; 3 μM) (Sigma-Aldrich), or 6xHis-tagged PvNod22 (1 or 3 μM) and were immediately placed on ice for 5 min. Luc was diluted to 25 nM in preheated reaction solutions (30°C) containing 30 μl of nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega), 25 mM HEPES/KOH (pH 7), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM DTT, and 100 μM firefly luciferin (Promega). Reactions were carried out at 30°C. Luc activity was measured at different times (5 to 90 min after initiation) in a luminometer (Monolight 3010; BD and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ, U.S.A.). The activity of native Luc was confirmed by performing luciferin refolding assays without the addition of PvNod22 under similar conditions. The Luc activity of the unheated sample was defined as 100% (Wang and Spector 2000). Data points and associated error bars represent the standard deviation from three replicates.

Cloning of PvNod22 GFP chimeras and subcellular localization

The PvNod22 SP (1 to 25 aa)-GFP5 chimera was produced by amplifying by conventional PCR the SP of PvNod22 with the SP-GFP primer set. The PCR product was cloned into the pENTR/D/TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen) and was verified by sequencing using M13 primers. The construct SP-GFP was obtained by combining SP:pENTR/D/TOPO with the Gateway compatible plant destination vector pEarleyGate103 (SP:pEarleyGate103), which generates a C-terminal fusion to the fluorescent protein GFP (Earley et al. 2006). Next, a DNA fragment of PvNod22 (26 to 197 aa), including the cloning sites for DraIII and XbaI, was PCR amplified and cloned into SP:pEarleyGate103, generating the PvNod22 SP (1 to 25 aa)-GFP-PvNod22 (26 to 197 aa) chimera. Sense and antisense oligonucleotides were used to amplify PvNod22 cDNA by PCR. The PCR product was also cloned into the pENTR/D/TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen) and was later transferred to pEarleyGate103, generating the chimeric construct PvNod22-GFP. All GFP chimeras generated in this work contained the GFP5 variant that has two excitation peaks (maxima at 395 and 473 nm). As described in previous protocols, four six-week-old tobacco plants were subjected to leaf infiltration with Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 harboring PvNod22-GFP, ERyk (Nelson et al. 2007), or AtERD2-YFP (Brandizzi et al. 2002a) plasmids. Plants cotransformed with PvNod22-GFP and ERyk or PvNod22-GFP and ERD2-YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) were then incubated under normal growth conditions for 3 days after infiltration. Transformed leaves were analyzed using confocal microscopy. Confocal imaging was performed on sections of transformed leaves using an inverted Zeiss LSM 510 META (LSM 510 Meta; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) confocal microscope. The objective was 40× water immersion. For imaging coexpression of YFP and GFP constructs, we used an argon ion laser (excitation lines for GFP = 458 nm, for YFP = 514 nm). The lines were alternated using the line switching mode of the multitrack facility of the microscope. For fluorescence detection, we used a 458/514-nm dichroic beam splitter and a 475/525-nm bandpass filter (GFP) and a 560/615-nm bandpass filter (YFP). Energy transfer between fluorochromes and cross-talk are known not to occur with these settings (Brandizzi et al. 2002a, b, and c).

Construction of viral vectors, in vitro transcription, and plant inoculation

The viral vector used for silencing PvNod22 expression in bean plants as well as the in vitro transcription protocol are fully described by Díaz-Camino and associates (2011). Briefly, a 360-bp DNA fragment encoding PvNod22 was amplified from bean cDNA using sequence-specific primers with BamHI and MscI sites, forward 5′GAGGCGGGATCCCAGGCGCTG TTG′3 and reverse 5′GTCTTCTGGCCACTCTCCGTGCCC′3. PvNod22 PCR products were digested with the same restriction enzymes and were subcloned into pGG7R2-V (Zhang and Ghabrial 2006). To use pGG7R2-V as an empty vector control, the plasmid was first digested by MscI and were then religated, giving rise to pGG7R2-M, which is infectious. Plasmid constructs were used for in vitro transcription as previously described (Gu and Ghabrial 2005) and were used for inoculation. Succinctly, capped RNA transcripts were synthesized by incubating 1 to 5 mg of linearized plasmids in a 100-μl reaction mixture containing 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 6 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 10 mM DTT, 50 units of RNasin (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, U.S.A.), 0.5 mM each ATP, CTP, and UTP, 0.1 mM GTP, 0.5 mM cap-analogue (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, U.S.A.), and 50 units of T7 RNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) at 37°C for 2 h. Yield and integrity of the transcripts were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel. RNA transcripts (RNA1 from strain K-Ho1 and recombinant RNA2) were used to rub-inoculate fully expanded unifoliate leaves of P. vulgaris. Plants were grown as described in the previous paragraph. Trifoliate leaves of vector inoculated and PvNod22-silenced plants were analyzed 3 weeks postinoculation. At least five plants were included per treatment.

Phylogenetic analysis and prediction of subcellular localization

sHsp of P. vulgaris were identified using the BLAST tool available on the Phytozome portal. The full-length protein sequences of selected sHsp from A. thaliana (Supplementary Table 3) and P. vulgaris were aligned with PvNod22 using Muscle software. An unrooted tree based on the protein alignment was reconstructed using the Neighbor-Joining method from the PHYLIP package. Bootstrap values were obtained from 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The sHsp lbpA from E. coli was used as outgroup in this analysis. sHsp organellar targeting sequences were predicted using Predotar and TargetP.

Antibodies, protein extraction, and immunoblot analysis

The peptide Ac-DQLELDMWRFRLPESTRC-OH coupled to keyhole limpet hemocanin was used to generate a polyclonal antibody against PvNod22 (NeoMPS-Polypetide Labs., Strasbourg, France). Anti–BPMV CP was produced in a previous study (Ghabrial and Schultz 1983). Plant proteins were extracted as described (Reddy et al. 2001). Bacterial extracts or plant tissue samples (20 μg) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 10 or 13.5% gels, were transferred to Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.), and were subjected to immunoblot analysis.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and determination of mRNA expression levels using qPCR

Trifoliate leaves of five treated or untreated 3-week-old bean plants were pooled and were considered as only one biological sample. In all experiments, at least two biological samples were analyzed. Samples were prepared and RNA was extracted using a one-step isolation method as previously described (Díaz-Camino et al. 2011). RNA quantity was measured spectrophotometrically, and only RNA samples with a 260/280 ratio of between 1.9 and 2.1 and a 260/230 ratio of greater than 2.0 were used for the analysis. The integrity of RNA samples was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. For reverse transcription, 3 μg of total RNA was treated with DNaseI (Invitrogen), and 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the Revert Aid H Minus First-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas) with anchored-oligo (dT)18 primer, according to manufacturers’ instructions. For qPCR, 15-μl qPCR reactions using Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas) were performed on an iCycle iQ5 apparatus (BioRad, Munich). The cycling conditions were as follows: preheating for 5 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturing for 15 s at 95°C, annealing and elongation for 15 s at 55.8°C, and data acquisition at 81°C. A negative control reaction without template was included for each primer combination. The melting curve protocol began immediately after amplification and consisted of 1 min at 55°C, followed by 80 steps of 10 s each, with a 0.5°C increase in temperature at each step. The relative numbers for cycle threshold of each gene were normalized to the housekeeping genes Ef1-α (elongation factor 1-α) (Nicot et al. 2005) and IDE (insulin-degrading enzyme), recently characterized in P. vulgaris (Borges et al. 2012). Similar results were collected for both genes; therefore, subsequent qRT-PCR experiments were normalized only with Ef1-α as reference gene. Data were analyzed using iQ5 Optical System Software (Version 2.1; BioRad). Three PCR amplifications were performed for each biological sample. We used Student’s t-test and single-factor analysis of variation (ANOVA) to find significant changes in gene expression between plant treatments. Fold increase in gene expression was the dependent variable. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant. ANOVA analysis was followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Cell death determination

Cell death was determined by measuring ion leakage from mock-, vector- or VIGS:PvNod22-inoculated leaf discs. Three discs (diameter 1.5 cm) were cut from different trifoliate leaves of 3-week-old bean plants and were floated, adaxial side up, on 15 ml of nanopure water for different periods of time at room temperature. Following incubation, the conductivity of the solution was measured with a conductivity meter (S30 SevenEasyTM; Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, U.S.A.). Measurements for each time point were performed in triplicate. Samples of each condition at 48 h were processed to determine mRNA expression levels of Bax-1 and LSD-1 using qPCR as previously described.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. R. Benitez, A. S. Amaro (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), and W. Havens (University of Kentucky) for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología 89754 and 177207 to C. Diaz-Camino and 177744 to F. Sanchez; by the Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México IN201412 to C. Diaz-Camino and IN106012 to F. Sanchez, and by the Kentucky Science and Engineering Foundation (KSEF-2178-RDE-013) to S. A. Ghabrial. We also acknowledge support by the grants to F. Brandizzi from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM101038-01) and the National Science Foundation (MCB 0948584 and MCB1243792) for partial support to G. Stefano and Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, US DOE (DE-FG02-91ER20021) for infrastructure (F. Brandizzi).

Footnotes

AUTHOR-RECOMMENDED INTERNET RESOURCES The Bio-Analytic Resource for Plant Biology database: www.bar.utoronto.ca

Center for Biological Sequence Analysis (CBS) TargetP server: www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP

Genevestigator database: www.genevestigator.ethz.ch

GenoPlante Predotar web server: urgi.versailles.inra.fr/predotar

Muscle software: www.drive5.com/muscle

PHYLIP software: www.phylip.com

Phytozome portal: www.phytozome.net

Current address for A. Padmanaban: Center for Molecular Biotechnology, Fraunhofer USA, 9 Innovation Way, Newark, DE 19711, U.S.A.

*The e-Xtra logo stands for “electronic extra” and indicates that three supplementary tables and one supplementary figure are published online.

LITERATURE CITED

- Alves MS, Reis PA, Dadalto SP, Faria JA, Fontes EP, Fietto LG. A novel transcription factor, early responsive to dehydration 15, connects ER stress with an osmotic stress-induced cell death signal. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:20020–20030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.233494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvim FC, Carolino SM, Cascardo JC, Nunes CC, Martinez CA, Otoni WC, Fontes EPB. Enhanced accumulation of BiP in transgenic plants confers tolerance to water stress. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1042–1054. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.3.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel J, Salamini F, Gebhardt C. Transcripts accumulating during cold storage of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers are sequence related to stress-responsive genes. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:445–452. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.2.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges A, Tsai SM, Caldas DG. Validation of reference genes for RTqPCR normalization in common bean during biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31:827–838. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandizzi F, Frangne N, Martin-Marc S, Hawes C, Neuhaus J-M, Paris N. The destination for single-pass membrane proteins is influenced markedly by the length of the hydrophobic domain. Plant Cell. 2002a;14:1077–1092. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandizzi F, Fricker M, Hawes C. A greener world: The revolution in plant bioimaging. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002b;3:520–530. doi: 10.1038/nrm861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandizzi F, Snapp EL, Roberts AG, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hawes C. Membrane protein transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi in tobacco leaves is energy dependent but cytoskeleton independent: Evidence from selective photobleaching. Plant Cell. 2002c;14:1293–1309. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton WJ, Dilworth MJ. Control of leghemoglobin synthesis in snake beans. Biochem. J. 1971;125:1075–1080. doi: 10.1042/bj1251075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacas J-L. Devil inside: Does plant programmed cell death involves the endomembrane system? Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:1453–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Damiani I, Puppo A, Frendo P. Redox changes during the Legume–Rhizobium symbiosis. Mol. Plant. 2009;2:370–377. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che P, Bussell JD, Zhou W, Estavillo GM, Pogson BJ, Smith SM. Signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum activates brassinosteroid signaling and promotes acclimation to stress in Arabidopsis. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:ra69. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001140. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRocher AE, Helm AW, Lauzon LM, Vierling E. Expression of a conserved family of cytoplasmic low molecular weight heat shock proteins during heat stress and recovery. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:1038–1047. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.4.1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Camino C, Annamalai P, Sanchez F, Kachroo K, Ghabrial SA. An effective virus-based gene silencing method for functional genomics studies in common bean. Plant Meth. 2011;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich RA, Delaney TP, Uknes SJ, Ward ER, Ryals JA, Dangl JL. Arabidopsis mutants simulating disease resistance response. Cell. 1994;77:565–577. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. SA, JA, ethylene, and disease resistance in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1998;1:316–323. doi: 10.1016/1369-5266(88)80053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley KW, Haag JR, Pontes O, Opper K, Juehne T, Song K, Pikaard CS. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 2006;45:616–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard L, Helenius A. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:181–191. doi: 10.1038/nrm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria JA, Reis PA, Reis MT, Rosado GL, Pinheiro GL, Mendes GC, Fontes EP. The NAC domain-containing protein, GmNAC6, is a downstream component of the ER stress- and osmotic stress-induced NRP-mediated cell-death signaling pathway. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D-Q, Ghabrial S, Kachroo A. GmRAR1 and GmSGT1 are required for basal, R gene–mediated and systemic acquired resistance in soybean. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22:86–95. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-1-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Fujita Y, Noutoshi Y, Takahashi F, Narusaka Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: A current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Curr. Op. Plant Biol. 2006;9:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial SA, Schultz F. Serological detection of bean pod mottle virus in bean leaf beetles. Phytopathology. 1983;73:480–483. [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein DM, Shu S, Howson R, Neupane R, Hayes RD, Fazo J, Mitros T, Dirks W, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Rokhsar DS. Phytozome: A comparative platform for greenplant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1178–D1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H, Ghabrial SA. The Bean pod mottle virus proteinase cofactor and putative helicase are symptom severity determinants. Virology. 2005;333:271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D, Tuteja N. Chaperones and foldases in endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling in plants. Plant Sig. Behav. 2011;6:232–236. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.2.15490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck M, Franzmann T, Weinfurtner D, Buchner J. Some like it hot: The structure and function of small heat shock proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:842–846. doi: 10.1038/nsmb993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm KW, Schmeits J, Vierling E. An endomembrane-localized small heat-shock protein from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:287–288. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruz T, Laule O, Szabo G, Wessendorp F, Bleuler S, Oertle L, Widmayer P, Gruissem W, Zimmermann P. Genevestigator V3: A reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv Bioinformatics. 2008;2008:420747. doi: 10.1155/2008/420747. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata Y, Koizumi N. Unfolded protein response followed by induction of cell death in cultured tobacco cells treated with tunicamycin. Planta. 2005;220:804–807. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1479-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo JH, Wang SY, Chen JG, Jones AM, Fedoroff NV. Different signalling and cell death roles of heterotrimeric G protein α and β subunits in the Arabidopsis oxidative stress response to ozone. Plant Cell. 2005;17:957–970. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Katoh T, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Asamizu E, Kotani H, Miyajima N, Tabata S. Structural analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana chromosome 3, II: Sequence features of the 4,251,695 bp regions covered by 90 P1, TAC and BAC clones. DNA Res. 2000;7:217–221. doi: 10.1093/dnares/7.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi N, Ujino T, Sano H, Chrispeels MJ. Overexpression of a gene that encodes the first enzyme in the biosynthesis of asparagine-linked glycans makes plants resistant to tunicamycin and obviates the tunicamycin-induced unfolded protein response. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:353–361. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.2.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leborgne-Castel N, Jelitto-Van Dooren EP, Crofts AJ, Denecke J. Overexpression of BiP in tobacco alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress. Plant Cell. 1999;11:459–470. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.3.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GG, Vierling E. A small heat shock protein cooperates with heat shock protein 70 systems to reactivate a heat-denatured protein. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:189–197. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.1.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JX, Howell SH. Endoplasmic reticulum protein quality control and its relationship to environmental stress response in plants. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1–13. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JX, Srivastava R, Che P, Howell SH. Salt stress responses in Arabidopsis utilize a signal transduction pathway related to endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling. Plant J. 2007;51:877–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Cui F, Li Q, Yin B, Zhang H, Lin B, Wu Y, Xia R, Tang S, Xie Q. The endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation is necessary for plant salt tolerance. Cell Res. 2011;21:957–969. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez IM, Chrispeels MJ. Genomic analysis of the Unfolded Protein Response in Arabidopsis shows its connection to important cellular processes. Plant Cell. 2003;15:561–576. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad A, Miranda-Ríos J, Estrada GN, Quinto C, Olivares JE, García-Ponce B, Sanchez F. Nodulin 22 from Phaseolus vulgaris protects Escherichia coli cells from oxidative stress. Planta. 2004;219:993–1002. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasov V, Li J, Batoux M, Roux M, Chu Z-H, Lacombe S, Rougon A, Bittel P, Kiss-Papp M, Chinchilla D, van Esse HP, Jorda L, Schwessinger B, Nicaise V, Thomma BP, Molina A, Jones JD, Zipfel C. Control of the pattern-recognition receptor EFR by an ER protein complex in plant immunity. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 2009;28:3428–3438. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenfu A. A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J. 2007;51:1126–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicot N, Hausman JF, Hoffmann L, Evers L. Housekeeping gene selection for real-time RT-PCR normalization in potato during biotic and abiotic stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2005;56:2907–2914. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MS, Ghabrial SA, Redmond CT, Dinkins RD, Collins GB. Resistance to bean pod mottle virus in transgenic soybean lines expressing the capsid polyprotein. Virology. 2001;91:831–838. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.9.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shruthi SV, Jeffrey LB. One step at a time: Endoplasmic reticulum–associated degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:944–957. doi: 10.1038/nrm2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique M, Gernhard S, von Koskull-Döring P, Vierling E, Scharf KD. The plant sHsps superfamily: Five new members in Arabidopsis thaliana with unexpected properties. Cell Stress Chap. 2008;13:183–197. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0032-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W, Liu Y, Xia Y, Hong Z, Li J. Conserved endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation system to eliminate mutated receptor-like kinases in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:870–875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013251108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Van Montagu M, Verbruggen N. Small heat shock proteins and stress tolerance in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1577:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukaji N, Kuwabara C, Takezawa D, Arakawa K, Yoshida S, Fujikawa S. Accumulation of small heat-shock protein homologs in the edoplasmic reticulum of cortical parenchyma cells in mulberry in association with seasonal cold acclimation. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:481–489. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urade R. Cellular response to unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum of plants. FEBS Lett. 2007;274(5):1152–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente MA, Faria JA, Soares-Ramos JR, Reis PA, Pinheiro GL, Piovesan ND, Morais AT, Menezes CC, Cano MAO, Fietto LG, Loureiro ME, Aragao FJ, Fontes EP. The ER luminal binding protein (BiP) mediates an increase in drought tolerance in soybean and delays drought-induced leaf senescence in soybean and tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:533–546. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Weaber ND, Kesarwani M, Dong XN. Induction of protein secretory pathway is required for systemic acquired resistance. Science. 2005;308:1036–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1108791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Spector A. α-Crystallin prevents irreversible protein denaturation and acts cooperatively with other heat-shock proteins to renature the stabilized partially denatured protein in an ATP-dependent manner. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:4705–4712. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Lam E. Arabidopsis Bax inhibitor-1, a rheostat for ER stress-induced programmed cell death. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3:564–556. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.8.5709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters ER. The molecular evolution of the small heat shock proteins in plants. Genet. 1995;141:785–795. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.2.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters ER, Aevermann BD, Sanders-Reed Z. Comparative analysis of the small heat shock proteins in three angiosperm genomes identifies new subfamilies and reveals diverse evolutionary patterns. Cell Stress Chap. 2008;13:127–142. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0023-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q, Zhou WB, Hu GZ, Wei JM, Yang HQ, Huang JR. Heterotrimeric G-protein is involved in phytochrome A-mediated cell death of Arabidopsis hypocotyls. Cell Res. 2008;18:949–960. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D, Vinegar B, Nahal H, Ammar R, Wilson GV, Provart N. An “electronic fluorescent pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000718. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000718. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Ghabrial SA. Development of Bean pod mottle virus-based vectors for stable protein expression and sequence-specific virus-induced gene silencing in soybean. J. Virol. 2006;344:401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Shono M, Sun A, Yi S, Li M, Liu J. Constitutive expression of an endoplasmic reticulum small heat shock protein alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress in transgenic tomato. Plant Physiol. 2007;164:835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Chen P, Hymowitz T, Wickizer S, Gergerich R. Evaluation of glycine species for resistance to Bean pod mottle virus. Crop Prot. 2005;24:49–56. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.