Abstract

Substrate compliance is reported to alter cell phenotype, but little is known about the effects of compliance on cell development within the context of a complex tissue. In this study, we used 0.48 and 19.66 kPa polyacrylamide gels to test the effects of the substrate modulus on submandibular salivary gland development in culture and found a significant decrease in branching morphogenesis in explants grown on the stiff 19.66 kPa gels relative to those grown on the more physiologically compliant 0.48 kPa gels. While proliferation and apoptosis were not affected by the substrate modulus, tissue architecture and epithelial acinar cell differentiation were profoundly perturbed by aberrant, high stiffness. The glands cultured on 0.48 kPa gels were similar to developing glands in morphology and expression of the differentiation markers smooth muscle alpha-actin (SM α-actin) in developing myoepithelial cells and aquaporin 5 (AQP5) in proacinar cells. At 19.66 kPa, however, tissue morphology and the expression and distribution of SM α-actin and AQP5 were disrupted. Significantly, aberrant gland development at 19.66 kPa could be rescued by both mechanical and chemical stimuli. Transfer of glands from 19.66 to 0.48 kPa gels resulted in substantial recovery of acinar structure and differentiation, and addition of exogenous transforming growth factor beta 1 at 19.66 kPa resulted in a partial rescue of morphology and differentiation within the proacinar buds. These results indicate that environmental compliance is critical for organogenesis, and suggest that both mechanical and chemical stimuli can be exploited to promote organ development in the contexts of tissue engineering and organ regeneration.

Introduction

Since the advent of tissue engineering in the 1970s, medical researchers have sought to replace damaged or dysfunctional organs with artificial organs.1,2 While there have been some tissue engineering successes in fairly simple tissues, such as artificial skin grafts and bladders,3,4 tissue engineering of complex organs will require determination of the environmental cues necessary to establish and maintain proper cellular organization and differentiation in complex environments with multiple cell types.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is critical to many cellular processes, including growth, survival, morphogenesis, and differentiation.5–7 While most signals transmitted to cells via the ECM were once thought to be chemical signals, a landmark study that demonstrates individual mesenchymal stem cells respond to environmental stiffness8 catalyzed a perceptual shift that the physical properties of the ECM also directly impact cell phenotype. During organ development, epithelial–mesenchymal interactions are critical for the development and homeostasis of healthy tissues,9–11 as is the three-dimensional (3D) context of the organ development,12–17 and the mechanical properties of the ECM.8,18–24 Significantly, most research on compliance-dependent effects on cell phenotype has focused on the mechanical effects of stiffness on isolated mesenchymal cells, and few studies have investigated the effects of environmental stiffness on epithelial cells or complex cell mixtures within their native 3D contexts.

A complex organ of interest for tissue engineering is the salivary gland. Up to 4 million Americans suffer from xerostomia, or dry mouth, due salivary hypofunction or reduced saliva flow by salivary acinar cells. The causes of salivary hypofunction are many, including the autoimmune disease Sjögren's syndrome, radiation treatment for head and neck cancers, and medication side effects.25,26 These conditions decrease a person's ability to chew, speak, and swallow while increasing the risk of oral infections and dental caries, among other forms of morbidity.27,28 An engineered artificial salivary gland could offer relief to these patients29 and provide insights into mechanisms by which other branching organs could be engineered.

Saliva is produced in bilayered acini comprised of secretory epithelium surrounding a central lumen and encased by a discontinuous basal layer of myoepithelial cells that secrete the basement membrane, contract to stimulate saliva secretion,30,31 and maintain normal tissue architecture.32 Saliva production depends on the expression levels and localization of the water channel protein aquaporin 5 (AQP5) by the secretory epithelium33–36 and expression of smooth muscle alpha-actin (SM α-actin) by the myoepithelium37; loss of these functional markers is associated with salivary hypofunction.38,39 Engineering of an artificial salivary gland should thus strive to support both of these cell types.

To study the effects of extracellular compliance on development in the context of a 3D organ, we grew embryonic mouse submandibular salivary gland (mSMG) ex vivo organ explants on polyacrylamide (PA) gels of variable compliance.18,40 Using this system, we investigated the effects of substrate stiffness on mSMG organ formation, including the ability of the gland to (1) undergo branching morphogenesis, as indicated by morphometric analysis, and (2) differentiate into bilayered acinar cell populations, as indicated by the ability to express and localize AQP5 and SM α-actin proteins. Further, we investigated mechanical and chemical signals that can rescue normal tissue phenotype under conditions of aberrant stiffness.

Materials and Methods

PA gels

PA gels were created according to established procedures.40 Briefly, 12-mm-round glass coverslips were etched with 0.1 N NaOH at 80°C and immersed in 3-aminopropyltrimemethoxysilane (Sigma Aldrich) for 7 min. The coverslips were rinsed twice with distilled water for 10 min and immersed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS (v/v); Life Technologies] for 30 min. Acrylamide and bis-acrylamide were mixed at concentrations shown to yield gels of elastic moduli within the ranges of 0.48±0.16, 3.24±0.58, and 19.66±1.66 kPa. Glass slides were coated with Sigmacoat® (Sigma Aldrich) and baked at 100°C for 1 h. After cooling, 150 μL of PA gel solution was applied to the coated glass slides and then sandwiched with the activated glass coverslip. After 1 h, gels attached to coverslips were removed from the glass slide and placed in PBS to hydrate.

To provide cell attachment sites, gels were submersed in 0.2 mg/mL sulfo-SANPAH (Thermo Scientific) and exposed to ultraviolet light (UV; UVP) three inches from gels for 10 min, rinsed with 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.5; Sigma Aldrich), and submersed in 10 μg/mL of human plasma fibronectin (Millipore) overnight at 37°C to covalently link the protein. Removal of noncrosslinked material and gel equilibration were performed by rinsing three times with cell culture media for at least 1 h at 37°C. Before use, the gels were sterilized under a UV lamp for 45 min.

Culture of submandibular salivary gland ex vivo organ cultures on PA gels

mSMGs were dissected from timed-pregnant female mice (strain CD-1; Charles River Laboratories) with the day of plug discovery designated E0, following protocols approved by the University at Albany Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Embryonic day 13 (E13), submandibular salivary glands (SMGs) were microdissected from mandible slices and cultured as previously described,41–43 selected for 7±3 buds, and randomized from different embryos for each condition. The mSMGs were cultured atop PA gels in 24-well tissue culture plates with 1:1 DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies) lacking phenol red and supplemented with 50 μg/mL transferrin, 150 μg/mL L-ascorbic acid, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin surrounding the gels. Media were replaced every 24 h. Embryonic day 16.5 (E16.5) SMGs were similarly microdissected for comparison with experimental glands grown 96 h on PA gels.

For mechanical rescue experiments, glands were grown for 72 h at 19.66 kPa, gently rinsed using DMEM/F12 to detach them from the gel, and transferred with forceps to 0.48 kPa PA gels for the remaining 24 h. For growth factor rescue, 19.66 kPa gels were saturated with 0, 2, or 5 ng/mL of transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1; R&D Systems) during the rinsing process while the glands were incubated with TGFβ1 solution for 90 min at room temperature. The glands were cultured atop the TGFβ1-saturated gels for 96 h with media replaced every 24 h.

Quantitative analysis of bud counts

Brightfield images were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope equipped with a Canon EOS 450D digital camera at 4× (Plan 4×/0.10 NA), 10× (10× Ph1 ADL/0.25 NA), or 20× (LWD 20× Ph1 ADL/0.40 NA) magnification. Morphometric analysis was performed using MetaVue (Version 7.7.5.0), as previously described.44 A bud was detected by a shadow cast by the basement membrane around a rounded structure.

Whole-mount immunocytochemistry and confocal imaging

SMGs were fixed and simultaneously permeabilized with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (w/v) (Electron Microscopy Sciences) with 5% sucrose (w/v) (Fischer Scientific) and 0.1% Triton X (Sigma) in 1× PBS for 20 min and processed for immunocytochemistry (ICC), as previously described,41,45 with all antibody incubations performed overnight at 4°C. SMGs were washed 4×15 min in 1× PBS-0.1% Tween 20 (v/v) after each antibody incubation step, and mounted on glass coverslips with Secure-Seal imaging spacers (Grace Bio-Labs) in 25 μL Fluoro-Gel (Electron Microscopy Sciences). SMGs were imaged on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) and images were acquired at 10×, 20×, or 63× magnification.

Targets of antibodies used and their dilutions from stock are as follows: AQP5 (1:300 dilution; Alomone Labs), SM α-actin-Cy3 (clone 1A4) (1:200 dilution; Sigma Aldrich), and Collagen IV (Col IV, 1:200 dilution; Millipore). Cyanine, Dylight, and Alexa dye-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab′)2 fragments were used as secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Life Technologies).

Immunoblotting

Protein assays and western blots were performed essentially as previously described.45 Chemiluminescent blots were imaged using X-ray film and scanned using a flatbed scanner (CanoScan 4400F; Canon), and bands were quantified using Quantity One software (Version 19; BioRad) with normalization to GAPDH.

Targets of antibodies used and their dilutions are as follows: AQP5 (1:500 dilution; Millipore), SM α-actin (1:1000 dilution; Sigma Aldrich), and GAPDH (1:10,000 dilution; Fitzgerald).

Viability assays

For apoptosis assays, E13 glands were cultured on the 0.48 and 19.66 kPa gels for 24 and 96 h and sequentially fixed and stained for cleaved caspase 3 (CC3, 1:100 dilution; Cell Signaling) to identify apoptotic cells. As a positive control, glands on a Nuclepore filter (Whatman) were treated with brefeldin A (Millipore) at 5 μM for 4 h to induce apoptosis.46 Confocal stacks (512×512 pixels) of the cleaved caspase-3-positive cells and DAPI-counterstained nuclei (n=4/sample type) were collected. The apoptotic nuclei were quantified in MetaVue as the ratio of cleaved caspase-3/DAPI from the stacks and graphed with Prism 5 software (GraphPad).

For proliferation assays, western blots were performed for phospho-serine10 histone H3 (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling) and normalized to total histone H3 (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling).

Statistical analysis

One-way and two-way analysis of variance tests with Bonferroni's post-tests were carried out for statistical analyses with Prism 5 software. A value of p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. ICC and confocal imaging were repeated for at least three experiments to produce the representative composites.

Results

Branching morphogenesis is promoted by a compliant environment

To determine whether mechanical effects of the external environment impact embryonic salivary gland development, we created crosslinked PA gels with expected elastic moduli of 0.48, 3.24, and 19.66 kPa using a well-established protocol40 that has previously been used to demonstrate that cellular morphology and differentiation are modulated by the mechanical environment.18,21,22,47–53 The compliance of each gel was verified using atomic force microscope to calculate a compressive modulus,54 and measured values were similar to the predicted values (Supplementary Fig. S1A; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea). The 0.48 and 3.24 kPa gels thus have elastic moduli similar to normal E13 or adult glands (Supplementary Fig. S1B), while the 19.66 kPa gels have an elastic moduli similar to reported moduli for many salivary-gland-derived and other glandular cancers, respectively.55–57

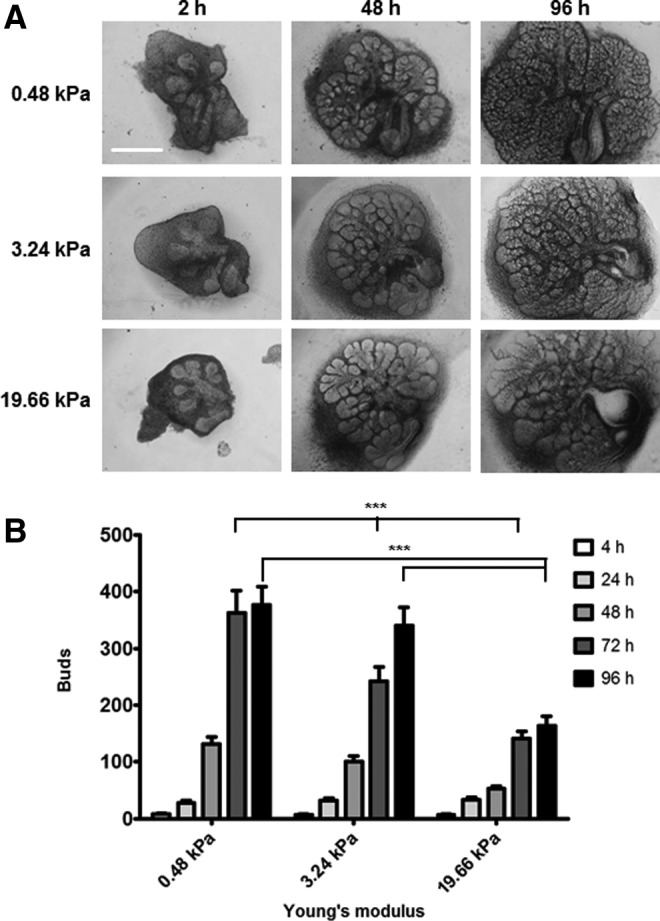

To assay whether branching morphogenesis of embryonic salivary glands can be impacted by the stiffness of the external environment, standard E13 SMG organ explants were adapted to culture on the surfaces of the PA gels having elastic moduli of 0.48, 3.24, and 19.66 kPa with covalently attached fibronectin. Brightfield images of organ explants cultured on these gels were captured every 24 h for up to 96 h. When the E13 embryonic mSMG organ explants were cultured on PA gels for 96 h, they continued to undergo branching morphogenesis on the 0.48 and 3.24 kPa gels with numerous, well-defined buds detected at 72 and 96 h, similar to the branching pattern of glands grown in vivo (Fig. 1A).41,44,58,59 Interestingly, explants cultured on stiff, 19.66 kPa gels demonstrated an altered morphology and appeared to have fewer buds (Fig. 1A). To quantify differences between explants grown on gels of different moduli, we performed morphometric analysis on the number of buds within each explant and used statistical analysis to compare the results. By 72 h, a negative regulation of branching morphogenesis correlating with increasing substrate stiffness was apparent (Fig. 1B), and this trend continued at the 96 h time point (p<0.001). While the glands grown at 19.66 kPa had significantly fewer buds than those grown at 0.48 kPa, there was no statistically significant difference in bud number in glands grown at 0.48 or 3.24 kPa (Fig. 1B). For this reason, we focused all subsequent analyses on glands grown on the 0.48 and 19.66 kPa gels.

FIG. 1.

Branching morphogenesis is promoted by a compliant substrate. (A, B) Branching decreases with stiffness. (A) Representative brightfield images exhibit E13 glands having six to seven buds that were grown on PA gels of three moduli for up to 96 h; scale bar=500 μm. (B) Morphometric analysis to quantify bud numbers was performed for organ explants grown on the three different PA gel moduli at 24-h increments. A two-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni post-tests was applied at each time point (n=8 explants/condition; ***p<0.001). Differences between bars not marked are not statistically relevant. ANOVA, analysis of variance; E13, embryonic day 13; PA, polyacrylamide.

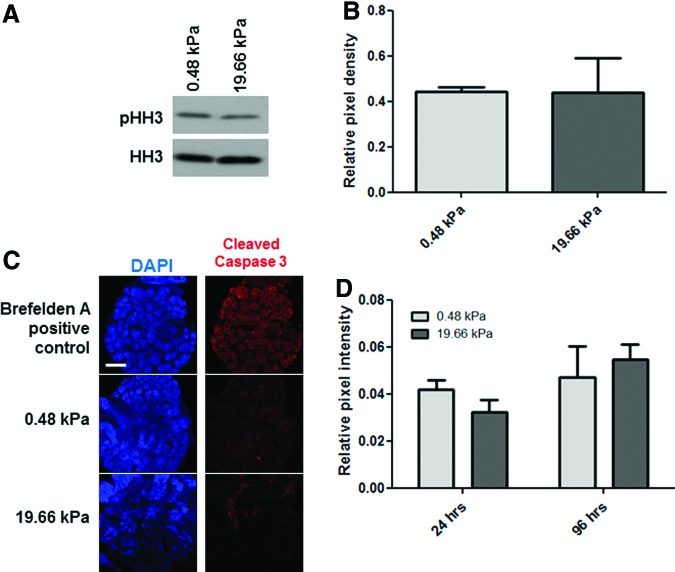

Since branching morphogenesis was reduced in explants grown on the 19.66 kPa gels and cell proliferation is known to be required for effective long-term branching morphogenesis,41 we assayed cell proliferation in explants grown on 0.48 and 19.66 kPa gels. Quantification of levels of the mitosis marker phospho-histone H360,61 relative to total histone H3 by western indicates that there was no significant difference in cell proliferation in explants grown at different stiffness (p>0.05; Fig. 2A, B). Since increased levels of apoptosis could also contribute to stiffness-dependent differences in gland morphology, we examined levels of apoptosis in explants by comparing levels of CC362,63 in confocal images acquired from glands subjected to ICC and costained for DAPI to detect total nuclei. Morphometric analysis of CC3-positive cells relative to total nuclei showed no statistical difference in apoptosis between explants grown at 0.48 and 19.66 kPa (p>0.05; Fig. 2C, D). Together, these results indicate that the decreased branching morphogenesis observed in glands grown at 19.66 kPa is neither due to differences in cell proliferation nor cell viability.

FIG. 2.

Decreased branching morphogenesis at high stiffness is not due to differences in proliferation or apoptosis. (A, B) Proliferation. (A) Western detection of phospho-histone H3 (pHH3) in comparison with total histone H3 (HH3) demonstrates no significant difference in the levels of phosphorylation at Ser 10 between glands grown on soft (0.48 kPa) and stiff (19.66 kPa) PA gels for 96 h. (B) Quantification of western analysis: relative pixel density of pHH3 relative to HH3. One-way ANOVA indicates no significant difference between the samples (n=3 experiments, p>0.05). (C, D) Apoptosis. (C) Single confocal images captured from representative organ explants cultured for 96 h and subjected to ICC to detect cleaved caspase 3 and counterstained with DAPI; scale bar=250 μm. Addition of brefelden A to culture media to glands grown atop polycarbonate filters induced apoptosis as a positive control that was used to define cleaved caspase-3-positive nuclei in morphometric analysis of pixel intensity in (D). (D) Quantification of apoptotic nuclei expressed as cleaved caspase-3-positive nuclei relative to total nuclei (DAPI) from stacks of confocal images spanning the thickness of the gland. One-way ANOVA indicates no significant difference in apoptosis between glands cultured on 0.48 kPa and 19.66 kPa gels after 24 or 96 h of culture (n=4 explants/condition, p>0.05). ICC, immunocytochemistry. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Expression and localization of secretory acinar and myoepithelial differentiation markers is best on the compliant PA gels

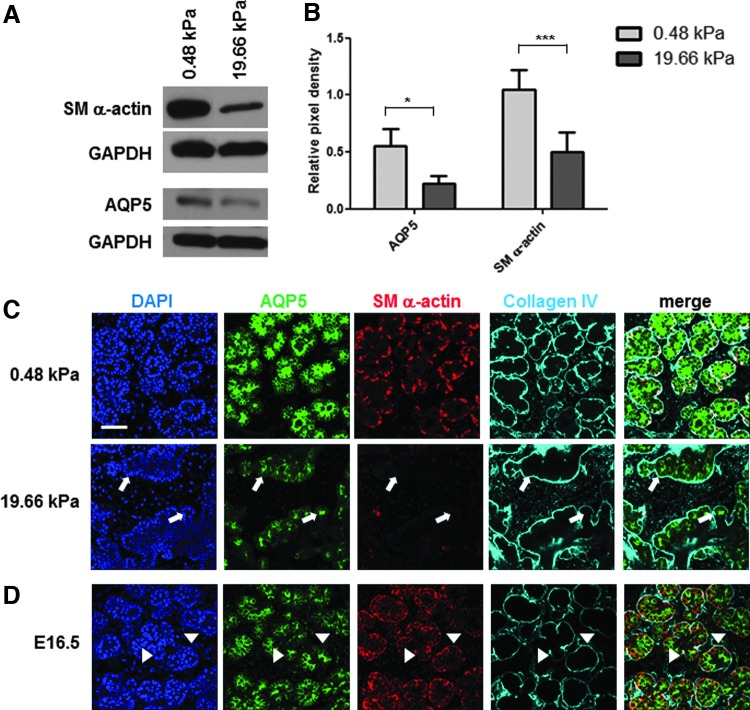

We hypothesized that since external compliance of the environment affects morphogenesis without significantly affecting proliferation or apoptosis that compliance affects epithelial cell organization and differentiation. We cultured SMG organ explants on 0.48 and 19.66 kPa gels to investigate the mechanical effects on two key epithelial differentiation markers: AQP5, which is expressed in developing mouse SMG proacinar and adult acinar secretory epithelial cells, and SM α-actin, which is expressed in developing and mature SMG myoepithelial cells.37 Both AQP5 and SM α-actin protein expression levels were significantly decreased in explants cultured on the 19.66 kPa gels (p<0.05 for AQP5 and p<0.001 for SM α-actin) (Fig. 3A, B). To examine the localization of these proteins, we performed ICC on cultured explants that were fixed at 96 h and captured confocal images from the center of each gland. Collagen IV staining was utilized as a basement membrane protein to depict overall bud and tissue structure as well as localization of AQP5 and SM α-actin proteins within the epithelium. There was a large decrease in the protein levels of both AQP5 and SM α-actin in the proacinar structures of glands grown on the 19.66 kPa gels. Additionally, whereas the localization of AQP5 was restricted to the interior cells of each proacinar structure and the SM α-actin was largely restricted to the outer cells of these structures in explants grown on the compliant 0.48 kPa gels, the distribution of these proteins was much less well-organized in glands grown on the 19.66 kPa gels (Fig. 3C). At 19.66 kPa, the buds had variable layers of irregular AQP5-expressing epithelium with scattered and discontinuous SM α-actin-positive myoepithelial progenitors, with some aberrantly shaped buds lacking any SM α-actin-positive cells. We compared the morphology of the glands grown on the PA gels with glands isolated from intact embryos. At E16.5, the glands grown in culture for 96 h on 0.48 kPa gels were most similar to this developmental stage (Fig. 3D).37 In both the 0.48-kPa-cultured glands and E16.5 glands, AQP5 is expressed apically and laterally in the proacinar epithelium, and SM α-actin is expressed primarily in the outer cuboidal cells of the developing acinar structures33,37 adjacent to the basement membrane (Fig. 3D). AQP5 and SM α-actin show mutually exclusive expression patterns in the developing secretory and myoepithelial cell populations, and the buds are relatively uniform in shape and size, with each bud being composed of several layers of epithelium surrounded by the basement membrane. By contrast, the aberrant tissue organization of glands grown on 19.66 kPa gels was not similar to any developmental stage (Fig. 3).37 Hence, the overall tissue architecture and expression and localization of epithelial differentiation markers indicate that the 0.48 kPa gels best support the developmental processes observed in vivo while morphogenesis and epithelial differentiation are disrupted in glands grown at 19.66 kPa.

FIG. 3.

Salivary gland proacinar morphology and epithelial differentiation are physiologically advanced by a compliant substrate and disrupted by aberrant stiffness. (A, B) Expression levels of differentiation markers. (A) Western analysis indicates a decrease in protein levels of both aquaporin 5 (AQP5) and SM α-actin with increasing stiffness. (B) Quantification of western analysis for AQP5 and SM α-actin protein levels, graphed as the relative pixel density of each band relative to the GAPDH control. A two-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni post-tests was applied at each time point (n=6 experiments, *p<0.05 for AQP5 and ***p<0.001 for SM α-actin). (C) Explant gland morphology and differentiated cell arrangement. Representative single confocal images captured from the center of organ explants demonstrate rounded buds, as detected by ICC for the basement membrane protein collagen IV (cyan) in explants grown on the 0.48 kPa gels. Less well-organized and less-consistent morphology is evident in explants cultured on 19.66 kPa gels. The myoepithelial cell protein SM α-actin (red) is expressed in the outer cuboidal cell populations of the rounded buds, and the proacinar/acinar protein AQP5 (green) is expressed in the interior epithelial cells in the glands cultured at low stiffness. In explants cultured at 19.66 kPa, the less-homogeneous bud structures generally show decreases in AQP5 and SM α-actin protein levels. Additionally, apically localized AQP5 can be detected in aberrant acinar structures lacking SM α-actin-positive cells (white arrows). n=10 experiments. (D) In vivo gland morphology and differentiated cell arrangement. Single confocal images captured at the center of E16.5 proacinar buds demonstrate that AQP5 is localized apically by the inner epithelial cells (green), highlighted by arrow heads, as in glands grown on 0.48 kPa PA gels. SM α-actin (red) is expressed in the outer cuboidal cells of the proacinar structures, interior to the basement membrane, as detected by anti-Col IV antibody (cyan). Scale bar=50 μm. E16.5, embryonic day 16.5; SM α-actin, smooth muscle alpha-actin.

Rescuing the 19.66 kPa phenotype

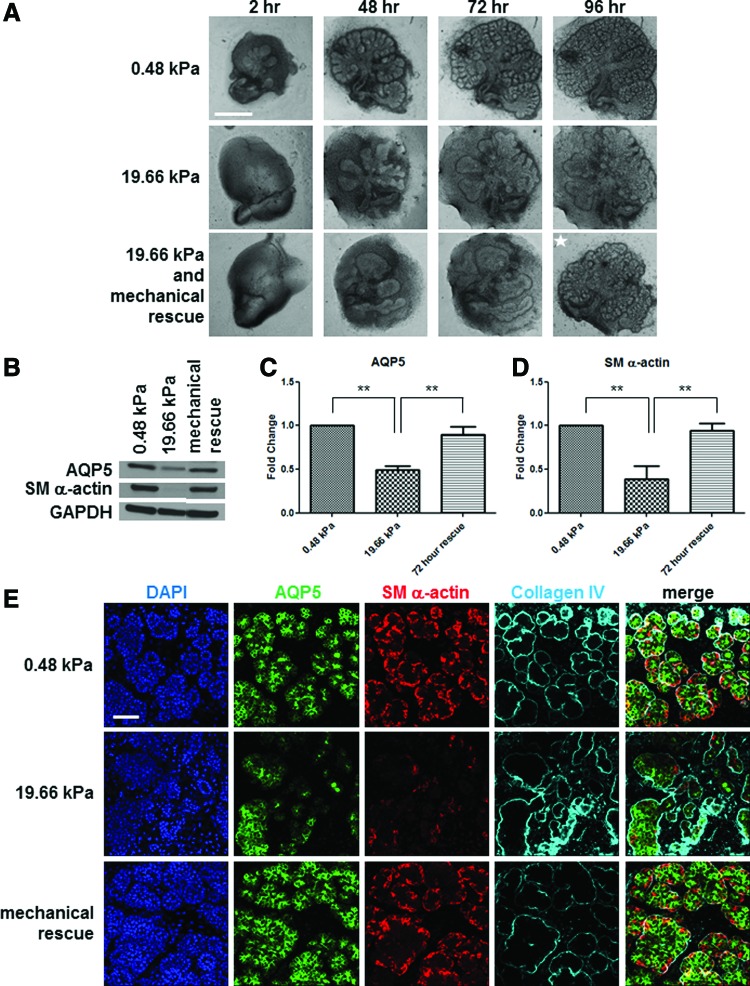

To determine whether reverting the pathologically stiff, 19.66 kPa environment to a more compliant state conducive to normal development could reestablish permissive growth conditions and rescue normal development, we grew SMG E13 organ explants on 19.66 kPa gels for 72 h to disrupt morphogenesis and differentiation prior to transferring them to 0.48 kPa gels for an additional 24 h. The transferred glands showed a change in tissue morphology that was strikingly similar to that seen in glands grown on 0.48 kPa gels (Fig. 4A) for the entire 96 h. By western analysis, both AQP5 and SM α-actin protein expression was significantly rescued in the transferred glands relative to glands grown continually on 19.66 kPa gels (p<0.01; Fig. 4B–D). ICC and confocal imaging of the rescued glands confirmed the increase in both proteins in the rescued glands (Fig. 4E). Similar to the 0.48 kPa glands, the proacinar structures in the rescued glands expressed SM α-actin in the outer periphery of the buds with AQP5 concentrated in the apical regions. Further, collagen IV and DAPI staining indicates that the buds in the rescued glands were more uniform in size and shape with SM α-actin expressed in all of the buds rather than only in a few of the variable layers of irregularly shaped, AQP5-expressing epithelium in glands grown at 19.66 kPa. Taken together, these data indicate that aberrant developmental processes caused by a stiff external environment are reversible and can be rescued with an environmental compliance akin to the natural environment.

FIG. 4.

The aberrant development of salivary gland organ explants grown on a stiff substrate can be rescued with a compliant substrate. (A) Mechanical rescue of branching morphogenesis. Brightfield images show representative E13 salivary glands grown at 0.48 and 19.66 kPa for 96 h with disruption of both bud morphology and number that is evident at 19.66 kPa. When transferred to a 0.48 kPa PA gel after 72 h culture on a 19.66 kPa gel, the glands regain a normal bud morphology and number similar to glands cultured on 0.48 kPa PA gels continuously. The white star indicates a transferred gland; scale bar=500 μm. (B–D) Mechanical rescue of epithelial differentiation marker expression levels. (B) Western analysis indicates a decrease in both AQP5 and SM α-actin with increasing stiffness. There is a near-complete rescue of both AQP5 and SM α-actin protein levels when glands are transferred from 19.66 kPa gel to the compliant 0.48 kPa gel. (C, D) Quantification of the western analysis of AQP5 (C) and SM α-actin (D), normalized to GAPDH and graphed as the fold change relative to the 0.48 kPa pixel density. A one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni post-tests was applied for each protein (n=4 experiments, **p<0.01). (E) Mechanical rescue of gland morphology and differentiated cell arrangement. Representative confocal images of glands transferred from 19.66 to 0.48 kPa demonstrate a robust rescue in bud morphology, as indicated by DAPI (blue) and collagen IV (cyan) localization and redistribution of both AQP5 (green) and SM α-actin (red). n=3 experiments. Scale bar=50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

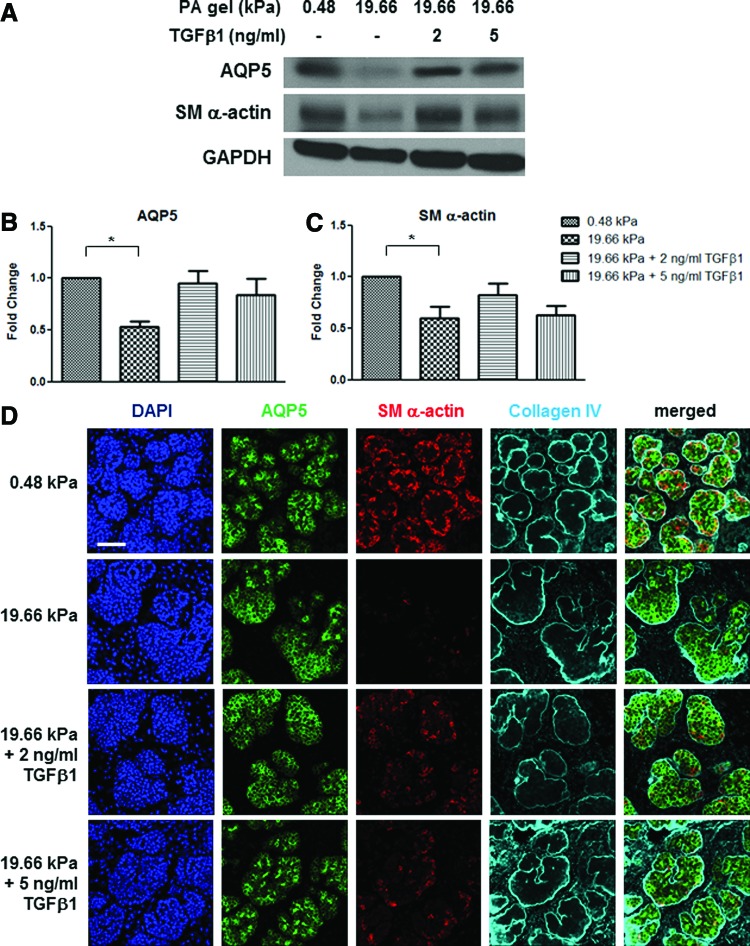

Given the robust mechanical rescue of salivary gland organ explants, we questioned whether a chemical signal could also rescue morphogenesis and differentiation of the explants. The apparent loss of myoepithelial cells in glands grown on a stiff external compliance (Figs. 3 and 4) is reminiscent of loss of differentiated myoepithelial cells in some salivary and breast cancers.31,32,64 Since TGFβ1 function has been shown to promote the expression of smooth muscle and contractile proteins, such as SM α-actin,65–67 and is implicated in the tumor-suppressive activities of myoepithelial cells,64 we tested TGFβ1 for its ability to rescue myoepithelial differentiation in the disrupted SMG organ explants grown at 19.66 kPa. Both AQP5 and SM α-actin expression was partially rescued with the addition of 2–5 ng/mL TGFβ1 to the media (Fig. 5A–C) as indicated by the total protein levels falling within ranges similar to both 0.48 kPa- and 19.66 kPa-cultured glands (p>0.05). Using ICC and confocal imaging to examine protein localization, we found a striking rescue of the proacinar bud morphology and tissue uniformity. SM α-actin accurately localized in the outer periphery of the buds in increasing amounts with the addition of TGFβ1, concomitant with the apical localization of AQP5, demonstrating a phenotype most similar to that of the normal embryonic E16.5 tissue with the addition of 5 ng/mL TGFβ1 (Figs. 3 and 5D). Since fibroblast growth factor 7 (FGF7) has been shown to rescue branching morphogenesis in the mSMG,68,69 we tested the effects of exogenous FGF7 for its ability to rescue the disruption in bud morphology seen at 19.66 kPa. Although there was some improvement in morphology and AQP5 protein expression levels, FGF7 did not rescue SM α-actin protein levels or either AQP5 or SM α-actin localization (Supplementary Fig. S2). Together, these data demonstrate a partial rescue of aberrant morphology and differentiation of both secretory acinar and myoepithelial populations by chemical signaling with exogenous TGFβ1, partially mimicking the robust mechanical rescue observed by altering exogenous matrix compliance.

FIG. 5.

The aberrant development of salivary glands grown on high-stiffness substrates is partially rescued with exogenous TGFβ1. (A–C) Chemical rescue of epithelial differentiation marker expression levels. (A) Western analysis indicates a decrease in AQP5 and SM α-actin with increasing stiffness that is partially rescued with exogenous TGFβ1 added to the culture media. (B, C) Quantification of western analysis to detect AQP5 and SM α-actin in response to TGFβ1, normalized to GAPDH and expressed as the fold change relative to the 0.48 kPa value. A one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni post-tests was applied for each protein (n=5 experiments, *p<0.05, p>0.05 for all other comparisons). TGFβ1 at either 2 or 5 ng/mL concentration did not significantly stimulate total protein levels of AQP5 or SM α-actin. (D) Chemical rescue of gland morphology and bilayered acini. Representative confocal images demonstrate that exogenous TGFβ1 (2 ng/mL) added to glands cultured on the high-stiffness substrate stimulates restoration of acinar morphology and uniformity, as detected by nuclear distribution (DAPI) and collagen IV (cyan) distribution concomitant with increased localization of SM α-actin (red) to the outer periphery of the proacinar buds. Additionally, with 5 ng/mL of exogenous TGFβ1, AQP5 (green) is progressively apically localized in the central cells together with the increased localization of SM α-actin in the outer cells in uniform proacinar structures. n=3 experiments. Scale bar=50 μm. TGFβ1, transforming growth factor beta 1. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Discussion

There is currently no method to engineer a salivary gland or other functional artificial secretory organs. While several studies demonstrate an ability of epithelial cells to self-organize on artificial scaffolds, the resulting complexes do not support development of functional secretory organs.29,70,71 Since appropriate environmental compliance has been demonstrated to be important for proper differentiation of several cell types,21,72–74 it is likely that scaffolds need to mimic the mechanical properties of the in vivo environment to support proper epithelial differentiation. Our data with PA gels demonstrate the proof of concept that compliance similar to that of the in vivo environment promotes mSMG tissue organization and differentiation, whereas high stiffness disrupted the process of branching morphogenesis, proacinar shape, and the expression levels of differentiation markers in myoepithelial and secretory epithelia. This indicates that an in-vivo-like compliance range is a crucial variable to consider when designing a physiologically compatible scaffold for tissue engineering research.

While it has been previously shown that individual cellular shape and differentiation are regulated by extracellular stiffness,8,23,49,75,76 our data highlight the fact that interacting cell populations within a tissue require an in-vivo-like elastic modulus to support the tissue's ability to self-organize, develop, and achieve homeostasis. The normal structure of a secretory acinar unit, in which AQP5-expressing cells form a spherical structure surrounded by a layer of SM α-actin-positive myoepithelial cells adjacent to the basement membrane, was achieved when SMG organ explants were cultured at the in-vivo-like, 0.48 kPa modulus. At high stiffness, we detected aberrant phenotypes, including abnormally shaped proacinar structures and lumenized proacinar structures lacking myoepithelial cells. Although previous research suggested that morphogenesis and differentiation are separate processes in the salivary gland,77 our data argue an interdependence of form and function.

In secretory organs such as salivary and mammary glands, the myoepithelium is reported to regulate acinar architecture; provide cues to the luminal cells for proliferation, differentiation, and polarization; and participate in stromal–epithelial interactions.32,78 Recent evidence also indicates a role for the myoepithelium in suppressing tumorigenesis.32,64,79,80 This suggests that these secretory tissues require bilayered acinar structures to support both the development and homeostasis of a functional organ. Scaffolds are often designed to support specific functional cell types, but given that mechanical cues affect different cell types differently, it may be more important to create scaffolds that can allow multiple interacting cells to self-organize. Our data indicate that the compliant, 0.48 kPa scaffold promoted the distribution of buds homogenous in structure and differentiation within both myoepithelial and secretory acinar populations. At high stiffness, the heterogeneous structure of the explants' shapes and extent of differentiation are structurally similar to that of certain cancers.81,82 Engineered scaffolds of appropriate stiffness may be required for tissues to achieve homeostasis and avoid progressing to a disease state. Further, the rescue of a tissue having abnormal morphology with a scaffold of the in-vivo-like compliance suggests that scaffolds of appropriate compliance may help to promote tissue regeneration or reversal of disease states, as with differentiation therapy.

In both the mechanical and chemical rescues, the expression of SM α-actin was restored in the myoepithelial population, the proacinar buds became more homogenous in structure, and the AQP5 localization became more apical, arguing for a role of myoepithelial cells in promoting acinar development. It remains unknown as to whether (1) TGFβ1 signaling is involved in normal myoepithelial differentiation, (2) TGFβ1 signaling is disrupted in the glands grown at higher stiffness, or (3) this growth factor has the ability to compensate for defects in other disrupted signaling pathways. Nevertheless, the capacity for a chemical moiety to mimic the mechanical rescue has important implications for smart scaffold development in that restoration of disrupted tissue environments together with chemical mediators of gland development may be required to effectively engineer artificial organs and promote tissue regeneration. While FGF7 was previously reported to rescue mSMG branching morphogenesis on stiff alginate gels,68 our research at a lower range of substrate moduli did not indicate a rescue of cellular differentiation or proacinar bud morphology. In the future, other chemical moieties may be useful in combination paradigms to direct and maintain acinar cell differentiation in salivary gland constructs. Future studies that employ a scaffold of a set of elastic modulus may require incorporation of specific chemical signals, possibly in a time-dependent manner, for effective tissue formation and homeostasis.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated that the morphogenesis and differentiation of the acinar cell populations within mSMG organ explants occurs normally on compliant substrates (in-vivo-like modulus) and abnormally on stiff substrates (pathogenic modulus). Further, we demonstrate that the effects of external stiffness on glandular development are reversible since explants initially cultured on gels of high stiffness and then transferred to a compliant gel were rescued in terms of both branching morphogenesis and expression and localization of the differentiation markers AQP5 and SM α-actin. Exogenous TGFβ1 added to explants grown at high stiffness also partially rescued branching morphogenesis and differentiation. Thus, our data indicate that glandular development and regeneration in the context of a complex tissue is highly dependent upon external compliance and that chemical signaling pathways can cross-talk with environmental stiffness. A scaffold with tunable mechanochemical properties could thus provide the signals to promote self-organization and homeostasis of an artificial, functional, and secretory organ.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. William Daley, Scott Varney, and Dr. Livingston Van De Water for useful suggestions. This work was supported by NIH grants R21DE021841 and RC1DE020402 and NYS Alliance 420065-09 to M.L.; C06 RR015464 to the University at Albany, SUNY; and NSF MRI DV10922830 to CNSE, University at Albany, SUNY.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Vacanti C.The history of tissue engineering. J Cell Mol Med 1,569, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atala A.Recent developments in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Curr Opin Pediatr 18,167, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atala A., Bauer S.B., Soker S., Yoo J.J., and Retik A.B.Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet 367,1241, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vrana N.E., Lavalle P., Dokmeci M.R., Dehghani F., Ghaemmaghami A.M., and Khademhosseini A.Engineering functional epithelium for regenerative medicine and in vitro organ models: a review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 19,529, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daley W.P., Peters S.B., and Larsen M.Extracellular matrix dynamics in development and regenerative medicine. J Cell Sci 336,169, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu P., Takai K., Weaver V.M., and Werb Z.Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3,1, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinhart-King C.A.How matrix properties control the self-assembly and maintenance of tissues. Ann Biomed Eng 39,1849, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engler A.J., Sen S., Sweeney H.L., and Discher D.E.Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126,677, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landsman L., Nijagal A., Whitchurch T.J., Vanderlaan R.L., Zimmer W.E., Mackenzie T.C., and Hebork M.Pancreatic mesenchyme regulates epithelial organogenesis throughout development. Vidal-Puig A.J., ed. PLoS Biol 9,e1001143, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thiery J.P.Epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in development and pathologies. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15,740, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders E.J.The roles of epithelial-mesenchymal cell interactions in developmental processes. Biochem Cell Biol 66,530, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosseinkhani H., Hiraoka Y., Li C.-H., Chen Y.-R., Yu D.-S., Hong P.-D., and Ou K.Engineering 3D collagen-IKVAV matrix to mimic neural microenvironment. ACS Chem Neurosci 4,1229, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker O.J., Schulz D.J., Camden J.M., Liao Z., Peterson T.S., Seye C.I., Petris M.J., and Weisman G.A.Rat parotid gland cell differentiation in three-dimensional culture. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 16,1135, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun T., Jackson S., Haycock J.W., and MacNeil S.Culture of skin cells in 3D rather than 2D improves their ability to survive exposure to cytotoxic agents. J Biotechnol 122,372, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mao Y., and Schwarzbauer J.E.Accessibility to the fibronectin synergy site in a 3D matrix regulates engagement of alpha5beta1 versus alphavbeta3 integrin receptors. Cell Commun Adhes 13,267, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H., Lin J., and Roy K.Effect of 3D scaffold and dynamic culture condition on the global gene expression profile of mouse embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials 27,5978, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee G.Y., Kenny P.A., Lee E.H., and Bissell M.J.Three-dimensional culture models of normal and malignant breast epithelial cells. Nat Methods 4,359, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelham R.J., and Wang Y.L.Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94,13661, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engler A.J., Griffin M.A., Sen S., Bönnemann C.G., Sweeney H.L., and Discher D.E.Myotubes differentiate optimally on substrates with tissue-like stiffness: pathological implications for soft or stiff microenvironments. J Cell Biol 166,877, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engler A.J., Richert L., Wong J.Y., Picart C., and Discher D.E.Surface probe measurements of the elasticity of sectioned tissue, thin gels and polyelectrolyte multilayer films: correlations between substrate stiffness and cell adhesion. Surf Sci 570,142, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reilly G.C., and Engler A.J.Intrinsic extracellular matrix properties regulate stem cell differentiation. J Biomech 43,55, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paszek M.J., Zahir N., Johnson K.R., Lakins J.N., Rozenberg G.I., Gefen A., Reinhart-King C.A., Margulies S.S., Dembo M., Boettiger D., Hammer D.A., and Weaver V.M.Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer cell 8,241, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeung T., Georges P.C., Flanagan L.A., Marg B., Ortiz M., Funaki M., Zahir N., Ming W., Weaver V., and Janmey P.A.Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 60,24, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Discher D.E., Janmey P., and Wang Y.-L.Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science 310,1139, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helmick C.G., Felson D.T., Lawrence R.C., Gabriel S., Hirsch R., Kwoh C.K., Liang M.H., Maradit Kremers H., Mayes M.D., Merkel P.A., Pillemer S.R., Reveille J.D., and Stone J.H.Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part, I. Arthritis Rheum 58,15, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ship J.A.Diagnosing, managing, and preventing salivary gland disorders. Oral Dis 8,77, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tabak L.A., Levine M.J., Mandel I.D., and Ellison S.A.Role of salivary mucins in the protection of the oral cavity. J Oral Pathol Med 11,1, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fox P.C.Xerostomia: recognition and management. Dent Assist 77,18, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aframian D.J., and Palmon A.Current status of the development of an artificial salivary gland. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 14,187, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Redman R.S.Myoepithelium of salivary glands. Microsc Res Tech 27,25, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogawa Y.Immunocytochemistry of myoepithelial cells in the salivary glands. Prog Histochem Cytochem 38,343, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adriance M.C., Inman J.L., Petersen O.W., and Bissell M.J.Myoepithelial cells: good fences make good neighbors. Breast Cancer Res 7,190, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsen H.S., Aure M.H., Peters S.B., Larsen M., Messelt E.B., and Kanli Galtung H.Localization of AQP5 during development of the mouse submandibular salivary gland. J Mol Histol 42,71, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Z., Zhao D., Gong B., Xu Y., Sun H., Yang B., and Zhao X.Decreased saliva secretion and down-regulation of AQP5 in submandibular gland in irradiated rats. Radiat Res 165,678, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang D., Iwata F., Muraguchi M., Ooga K., Ohmoto Y., Takai M., Mori T., and Ishikawa Y.Correlation between salivary secretion and salivary AQP5 levels in health and disease. J Med Invest 56Suppl,350, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuzaki T., Susa T., Shimizu K., Sawai N., Suzuki T., Aoki T., Yokoo S., and Takata K.Function of the membrane water channel aquaporin-5 in the salivary gland. Acta Histochem Cytochem 45,251, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson D.A., Manhardt C., Kamath V., Sui Y., Santamaria-Pang A., Can A., Bello M., COrwin A., Dinn S.R., Lazare M., Gervais E.M., Sequeira S.J., Peters S.B., Ginty F., Gerdes M.J., and Larsen M.Quantitative single cell analysis of cell population dynamics during submandibular salivary gland development and differentiation. Biol Open 2,439, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roussa E.Channels and transporters in salivary glands. Cell Tissue Res 343,263, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hakim S.G., Kosmehl H., Lauer I., Nadrowitz R., Wedel T., and Sieg P.The role of myoepithelial cells in the short-term radiogenic impairment of salivary glands. An immunohistochemical, ultrastructural and scintigraphic study. Anticancer Res 22,4121, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tse J.R., and Engler A.J.Preparation of hydrogel substrates with tunable mechanical properties. In: Bonifacin J.S., Dasso M., Harford J.F., Lippincott-Schwartz J., and Yamada K.M, eds. Current Protocols In Cell Biology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2010, Chapter 10, Unit 10.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daley W.P., Gulfo K.M., Sequeira S.J., and Larsen M.Identification of a mechanochemical checkpoint and negative feedback loop regulating branching morphogenesis. Dev Biol 336,169, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rebustini I.T., Myers C., Lassiter K.S., Surmak A., Szabova L., Holmbeck K., Pedchenko V., Hudson B.G., and Hoffman M.P.MT2-MMP-dependent release of collagen IV NC1 domains regulates submandibular gland branching morphogenesis. Dev Cell 17,482, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakai T., and Onodera T.Embryonic organ culture. In: Bonifacin J.S., Dasso M., Harford J.F., Lippincott-Schwartz J., and Yamada K.M, eds. Current Protocols In Cell Biology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008, Chapter 19, Unit 19.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larsen M., Hoffman M.P., Sakai T., Neibaur J.C., Mitchell J.M., and Yamada K.M.Role of PI 3-kinase and PIP3 in submandibular gland branching morphogenesis. Dev Biol 255,178, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sequeira S.J., Soscia D.A., Oztan B., Mosier A.P., Jean-Gilles R., Gadre A., Cady N.C., Yener B., Castracane J., and Larsen M.The regulation of focal adhesion complex formation and salivary gland epithelial cell organization by nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds. Biomaterials 33,3175, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao R.G., Shimizu T., and Pommier Y.Brefeldin A is a potent inducer of apoptosis in human cancer cells independently of p53. Exp Cell Res 227,190, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kandow C.E., Georges P.C., Janmey P.A., and Beningo K.A.Polyacrylamide hydrogels for cell mechanics: steps toward optimization and alternative uses. Methods Cell Biol 83,29, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang G., Huang A.H., Cai Y., Tanase M., and Sheetz M.P.Rigidity sensing at the leading edge through alphavbeta3 integrins and RPTPalpha. Biophys J 90,1804, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Q., Hosaka T., Jambaldorj B., Nakaya Y., and Funaki M.Extracellular matrix with the rigidity of adipose tissue helps 3T3-L1 adipocytes maintain insulin responsiveness. J Med Invest 56,142, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shih Y.-R.V., Tseng K.-F., Lai H.-Y., Lin C.-H., and Lee O.K.Matrix stiffness regulation of integrin-mediated mechanotransduction during osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Miner Res 26,730, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhana B., Iyer R.K., Chen W.L.K., Zhao R., Sider K.L., Likhitpanichkul M., Simmons C.A., and Radisic M.Influence of substrate stiffness on the phenotype of heart cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 105,1148, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peyton S.R., and Putnam A.J.Extracellular matrix rigidity governs smooth muscle cell motility in a biphasic fashion. J Cell Physiol 204,198, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reinhart-king C.A., Dembo M., and Hammer D.A.Endothelial cell traction forces on RGD-derivatized polyacrylamide substrata. Langmuir 11,1573, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mosier A.P., Kaloyeros A.E., and Cady N.C.A novel microfluidic device for the in situ optical and mechanical analysis of bacterial biofilms. J Microbiol Methods 91,198, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang J.M., Park I.A., Lee S.H., Kim W.H., Bae M.S., Koo H.R., Yi A., Kim S.J., Cho N., and Moon W.K.Stiffness of tumours measured by shear-wave elastography correlated with subtypes of breast cancer. Eur Radiol 9,2450, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyshchik A., Higashi T., Asato R., Tanaka S., Ito J., Hiraoka M., Saga T., and Togashi K.Elastic moduli of thyroid tissues under compression. Ultrason Imaging 27,101, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhatia K.S.S., Cho C.C.M., Tong C.S.L., Lee Y.Y.P., Yuen E.H.Y., and Ahuja A.T.Shear wave elastography of focal salivary gland lesions: preliminary experience in a routine head and neck US clinic. Eur Radiol 22,957, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamada K.M., and Cukierman E.Modeling tissue morphogenesis and cancer in 3D. Cell 130,601, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patel V.N., Rebustini I.T., and Hoffman M.P.Salivary gland branching morphogenesis. Differentiation 74,349, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pérez-Cadahía B., Drobic B., and Davie J.R.H3 phosphorylation: dual role in mitosis and interphase. Biochem Cell Biol 87,695, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hans F., and Dimitrov S.Histone H3 phosphorylation and cell division. Oncogene 20,3021, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu X., Zou H., Slaughter C., and Wang X.DFF, a heterodimeric protein that functions downstream of caspase-3 to trigger DNA fragmentation during apoptosis. Cell 89,175, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Janicke R.U.Caspase-3 Is Required for DNA fragmentation and morphological changes associated with apoptosis. J Biol Chem 273,9357, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu M., Yao J., Carroll D.K., Weremowicz S., Chen H., Carrasco D., Richardson A., Violette S., Nikolskaya T., Nikolsky Y., Bauerlein E.L., Hahn W.C., Gelman R.S., Allred C., Bissell M.J., Schnitt S., and Polyak K.Regulation of in situ to invasive breast carcinoma transition. Cancer cell 13,394, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Desmoulière A., Geinoz A., Gabbiani F., and Gabbiani G.Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 122,103, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Malmström J., Lindberg H., Lindberg C., Bratt C., Wieslander E., Delander E.-L., Särnstrand B., Burns J.S., Mose-Larsen P., Fey S., and Marko-Varga G.Transforming growth factor-beta 1 specifically induce proteins involved in the myofibroblast contractile apparatus. Mol Cell Proteomics 3,466, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morosetti R., Mirabella M., Gliubizzi C., Broccolini A., De Angelis L., Tagliafico E., Sampaolesi M., Gidaro T., Papacci M., Roncaglia E., Rutella S., Ferrari S., Tonali P.A., Ricci E., and Cossu G.MyoD expression restores defective myogenic differentiation of human mesoangioblasts from inclusion-body myositis muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103,16995, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miyajima H., Matsumoto T., Sakai T., Yamaguchi S., An S.H., Abe M., Wakisaka S., Lee K.Y., Egusa H., and Imazato S.Hydrogel-based biomimetic environment for in vitro modulation of branching morphogenesis. Biomaterials 32,6754, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Steinberg Z., Myers C., Heim V.M., Lathrop C.A., Rebustini I.T., Stewart J.S., Larsen M., and Hoffman M.P.FGFR2b signaling regulates ex vivo submandibular gland epithelial cell proliferation and branching morphogenesis. Development 132,1223, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aframian D.J., Tran S.D., Cukierman E., Yamada K.M., and Baum B.J.Absence of tight junction formation in an allogeneic graft cell line used for developing an engineered artificial salivary gland. Tissue Eng 8,871, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Badylak S.F., Weiss D.J., Caplan A., and Macchiarini P.Engineered whole organs and complex tissues. Lancet 379,943, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Majkut S.F., and Discher D.E.Cardiomyocytes from late embryos and neonates do optimal work and striate best on substrates with tissue-level elasticity: metrics and mathematics. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 11,1219, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang S., and Ingber D.E.Cell tension, matrix mechanics, and cancer development. Cancer Cell 8,175, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Holst J., Watson S., Lord M.S., Eamegdool S.S., Bax D.V., Nivison-Smith L.B., Kondyurin A., Ma L., Oberhauser A.F., Weiss A.S., and Rasko J.E.Substrate elasticity provides mechanical signals for the expansion of hemopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat Biotechnol 28,1123, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alcaraz J., Xu R., Mori H., Nelson C.M., Mroue R., Spencer V.A., Brownfield D., Radisky D.C., Bustamante C., and Bissell M.J.Laminin and biomimetic extracellular elasticity enhance functional differentiation in mammary epithelia. EMBO J 27,2829, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo W., Frey M.T., Burnham N.A, and Wang Y.Substrate rigidity regulates the formation and maintenance of tissues. Biophys J 90,2213, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cutler L.S., and Gremski W.Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the development of salivary glands. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2,1, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Deugnier M.-A., Teulière J., Faraldo M.M., Thiery J.P., and Glukhova M.A.The importance of being a myoepithelial cell. Breast Cancer Res 4,224, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gudjonsson T., Adriance M.C., Sternlicht M.D., Petersen O.W., and Bissell M.J.Myoepithelial cells: their origin and function in breast morphogenesis and neoplasia. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 10,261, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Faraldo M.M., Teulière J., Deugnier M.-A., Taddei-De La Hosseraye I., Thiery J.P., and Glukhova M.A.Myoepithelial cells in the control of mammary development and tumorigenesis: data from genetically modified mice. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 10,211, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Polyak K.Heterogeneity in breast cancer. J Clin Invest 121,3786, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guinebretiere J.M.Cancer is heterogeneous. J Clin Oncol 27,2732, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hutter J.L., and Bechhoefer J.Calibration of atomic-force microscope tips. Rev Sci Instrum 64,1868, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carl P., and Schillers H.Elasticity measurement of living cells with an atomic force microscope: data acquisition and processing. Pflugers Arch 457,551, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hertz H.Über die Berührung fester elastischer Körper. J Reine Angew 92,156–71, 1882 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sneddon I.N.The relation between load and penetration in the axisymmetric boussinesq problem for a punch of arbitrary profile. Int J Eng Sci 3,47, 1965 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.